Abstract

The development of accurate and non-invasive temperature imaging techniques has a wide variety of applications in fields such as medicine, chemistry and materials science. Accurate detection of temperature both in phantoms and in vivo can be obtained using iMQCs (intermolecular multiple quantum coherences), as demonstrated in a recent paper [1]. This paper describes the underlying theory of iMQC temperature detection, as well as extensions of that work allowing not only for imaging of absolute temperature but also for imaging of analyte concentrations through chemically selective spin density imaging.

Keywords: INTERMOLECULAR MULTIPLE QUANTUM COHERENCE, CRAZED, TEMPERATURE IMAGING, HIGH-RESOLUTION, HYPERTHERMIA, WATER, SPECTROSCOPY, THERMOMETRY, INHOMOGENEOUS FIELDS, CHEMICAL SELECTIVE IMAGING

1. Introduction

Non-invasive temperature measurements are useful for a variety of applications in medicine [2], chemistry and materials science. In particular, recent developments in hyperthermia, an adjunctive cancer therapy which treats tumors through radio frequency (RF) or ultrasound heating, have created significant interest in developing methods for temperature imaging with magnetic resonance [3; 4]. Medical applications of hyperthermia vary from treatment of uterine fibroids to recent research in treatment of breast cancer and brain tumors with hyperthermia [4; 5; 6; 7], and these applications have motivated several MR manufacturers to develop MR compatible focused ultrasound arrays for delivery of hyperthermic treatment [5]. Several heating methods that rely on MRI for temperature feedback are also in development [6; 7; 8], though no method for absolute temperature mapping exists. Many MR parameters (relaxation times, diffusion rates, magnetization density) change with temperature [9], but most parameters are highly heterogeneous in magnitude or temperature dependence. This has led to a focus on two specific markers, the proton frequency shift (PFS) of water (which changes by 0.01 ppm/°C) [10] and the difference in the chemical shift of water and fat [11], since the fat resonance frequency changes relatively little with temperature [12] and thus serves as an internal reference.

Since the absolute resonance frequency depends on susceptibility and precise field strength, PFS measurements are done by subtracting two phase images (one at a reference temperature and one at an elevated temperature) to obtain a relative temperature. However, the requirement of a baseline image makes the measurement highly susceptible to motion. Spectroscopy methods that observe differences between the water resonance frequency and a reference peak [13]; [14; 15; 16] can extract absolute temperature, but generally the voxel size for such experiments is quite large and the inhomogeneities present within the voxel cannot be removed. The frequency differences between broad lines with changing shapes are difficult to extract, making this method very challenging. While both of these methods provide temperature information, they are generally limited by larger changes in susceptibility and magnetic field inhomogeneity [13; 17; 18].

In tissues with a high fat content, such as the breast, application of PRF methods is not immediately straightforward. If we include susceptibility into the calculations of temperature change, then the resonance frequency of the water protons is not only dependent on the changes in the chemical shift of the protons, but also from changes to the susceptibility of the tissue. For the temperature ranges used in hyperthermic treatment, both the chemical shift change and the changes due to susceptibility can be treated as linear. The temperature dependence of the susceptibility constant depends on the tissue type and is 0.0026 ppm/°C for pure water, 0.0019 ppm/°C for muscle and 0.0094 ppm/ °C in fat[19; 20]. In tissues dominated by the water molecules (as opposed to fat molecules) the change in chemical shift dominates (at 0.01 ppm/°C), and the errors from changes in susceptibility only create 10% variations in the temperature detection. The chemical shift of fat is nearly constant over the range of temperatures used in hyperthermic treatment (0.00018 ppm/°C)[21] and fat suppression methods are almost always used. An additional complication comes from changes in susceptibility with temperature. The changes in susceptibility for the water signal are negligible, but the change in susceptibility of fat is much larger, 0.0094 ppm/°C. Thus, even with fat suppression methods, the changes in the susceptibility of fat are significant relative to the change in chemical shift, especially in tissues which are high in fat content.

We have developed a new method for temperature imaging using intermolecular multiple quantum coherences (iMQCs). One particular type of iMQC, intermolecular zero quantum coherence (iZQC), has been demonstrated to yield very sharp, narrow peaks, even in incredibly inhomogeneous magnets [22; 23]. iZQCs represent simultaneous transitions of two (or more) spins in opposite directions. The characteristic iZQC resonance frequency is the difference in resonance frequency of the two spins. The two spins that create the coherence are separated by a tunable distance (usually about 100 microns), so the iZQC peaks are narrow because all contributions from magnetic susceptibility and inhomogeneity are removed on a distance scale which is an order of magnitude smaller than the typical voxel size. This technique can be applied to temperature imaging by observing the iZQC signal between water and fat spins [24], which can give a sharp line even if the fat and water peaks are individually broadened; thus, the detected iZQC signal contains only the temperature information. While iZQC temperature imaging is superficially very similar to PFS methods, the physics used to create the signal isolates changes in the chemical shift of water rather than its absolute resonance frequency. The result is a temperature map that circumvents most artifacts and can be interpreted on an absolute scale. In this paper, we describe how the iMQC signal can be used to measure temperature and the necessary modifications to the standard iZQC pulse sequence in order to obtain a clean temperature map. We demonstrate the iMQC temperature imaging method on several phantoms in different temperature situations (uniform temperature distribution as well as a phantom with a temperature gradient) and show that the iMQCs provide a clean temperature measurement. In addition, we demonstrate a modification of the iMQC temperature imaging sequence which acquires four images; the first two images contain temperature information, and the last two are chemically selective spin density images.

2. Methods – Application of iMQCs for Temperature Imaging

Applications of iMQC imaging allow for temperature imaging using MR. In standard MR temperature imaging, the temperature information is contained in the changes to the proton resonance frequency (0.01 ppm/ °C). For example, at 7T, the change in resonance frequency is 3 Hz/°C. However, detecting such a small change in vivo can be challenging because the topography of the local magnetic field changes dramatically with motion, heating, drift, and susceptibility gradients. These effects overshadow the much smaller frequency shift due to temperature changes. In order to detect this small change, the fat signal (the frequency of which is constant with temperature over a biologically interesting range) is used as an internal reference. By acquiring signal at the difference frequency of fat and water, the fat can serve as an internal reference and compensate for the non-temperature based frequency shifts. This works because the fat protons are a correlation distance (usually ~100 µm) from the water protons and are in an identical environment, and thus, they experience the same macroscopic effects (such as changes in frequency due to motion, drift and susceptibility gradients). Motion, such as respiratory motion (as is the case in our studies, or the later mentioned bowel motion) cause the spins creating the iZQC to move together, thus preserving the coherence. The only motion that would cause the iZQC signal to break down is motion that causes the distance between the spins to change (although of course large motions, comparable to the voxel size in the image, will cause blurring).

iZQCs evolve at the difference frequency between the two spins, and the mixed spin iZQCs (those between water and fat) can provide a signal that is insensitive to the local magnetic field variations and susceptibility changes, but is sensitive to temperature changes. This can be easily seen by calculating the effect on the resonance frequency of a susceptibility gradient. For example, imagine a massive susceptibility change of 10 ppm. At 7T, this would cause a variation in resonance frequency of 300 MHz * 10 × 10−6 = 3 kHz. Such a variation in resonance frequency would correspond to temperature changes of 1000 °C. However, the zero quantum transition occurs at the difference frequency of the two spins. In our specific application at 7T, the iZQC transition is at the water – fat difference frequency of 1000 Hz. Thus, the effect of the susceptibility gradient is 1000 Hz * 10 × 10−6 = 0.01 Hz, which corresponds to a temperature difference of 0.0033 °C. This simple calculation demonstrates why iZQC temperature measurements are inherently insensitive to changes in susceptibility, making them well suited for temperature detection in inhomogeneous tissues.

It is intuitively clear that iZQCs retain chemical shift information while removing inhomogeneous broadening. Less obviously, +2-quantum iDQC (intermolecular double quantum coherence) evolution during one period (at the sum of the two different resonance frequencies) can combine with −1-quantum evolution during a later period to also give a signal that is free of inhomogeneous broadening. This works because the −1-quantum evolution is at only one of the two resonance frequencies, not the average. For example, the signal from a +2 quantum CRAZED sequence starts as I+S+, which acquires an evolution of (ωIt1+ ωSt1) and also acquires inhomogeneous broadening of (ΔωIt1 + ΔωSt1). After the mixing pulse, the coherence is either I−Sz or IzS− and evolves for 2t1. The spin that is in the plane (either I− or S−) evolves at −2ωIt1 or −2ωSt1. If that spin sees the same inhomogeneous broadening (i.e., ΔωI = ΔωS) during the 2t1 period as both the spins did during the t1 period, then all the inhomogeneous broadening gets reversed (i.e., ΔωIt1 + ΔωSt1 = 2 ΔωSt1 or ΔωIt1 + ΔωSt1 = 2 ΔωIt1). In other words, the ability to refocus inhomogeneous broadening is more closely tied to the ability to couple spins that experience the same local field than the particular order of the coherence.

The temperature imaging pulse sequence used in our experiments uses both iZQCs and iDQCs to detect temperature. iZQCs have extraordinarily sharp lines, even in very inhomogeneous fields [23]. Unfortunately, iZQC experiments (known as the HOMOGENIZED sequence [22] or the iZQC – CRAZED sequence) are often contaminated by a large amount of SQCs (one-spin, single quantum coherences – conventional magnetization), and it can be hard to extract the narrow iZQC peaks from the broad SQC peaks. On the other hand, iDQC experiments (such as those detected in the CRAZED sequence [25; 26; 27]) cleanly select the desired iDQC signal and have minimal contamination from SQCs. We use a sequence which has the narrow lineshape of an iZQC and the robust filtering of an iDQC. We do this by converting iZQCs into iDQCs and vice versa, allowing the system to evolve as both types of coherence and thus preserving the desired properties of each type of coherence.

2.1 Modifications to the HOMOGENIZED Sequence for Temperature Imaging

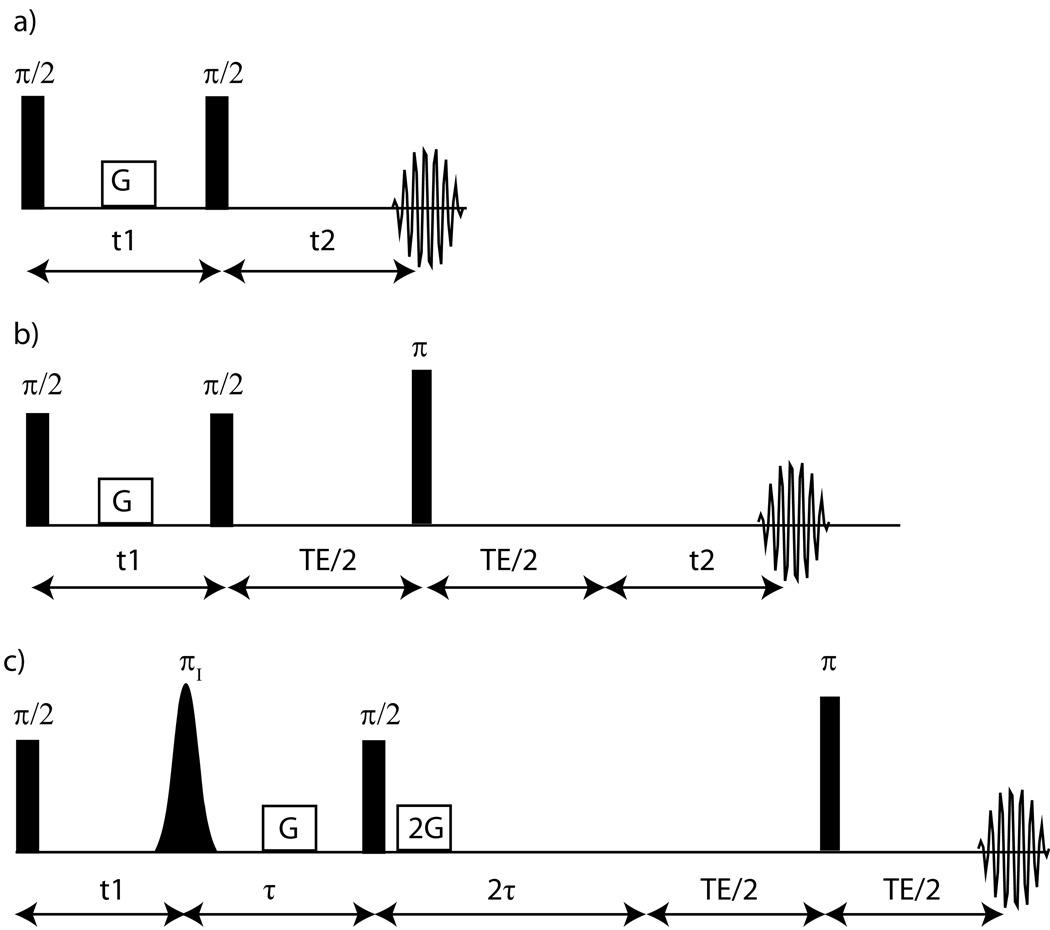

In the standard iMQC pulse sequences, the major contribution to the signal is given by the same spin (in the case of fatty tissue, water-water and fat-fat) iMQC transitions, which are insensitive to temperature changes. The mixed spin, water-fat iZQC transition frequency changes linearly with temperature and can be used to create a temperature map. The detection of the temperature-sensitive, mixed spin iZQC signal can be challenging, since the temperature-insensitive same spin iZQCs dominate. This can be easily seen by inspection of the standard signal for a two component iZQC CRAZED experiment, (π/2)x-t1-{gradient pulse}-θx-t2-acquire, as shown in Figure 1a [28]. In a sample containing two chemical species I and S, ignoring diffusion, relaxation, and inhomogeneous broadening, the signal arising from the I-I (same spin) iZQCs is given by [28]:

| (1) |

Here ωI is the chemical shift of spin I, and τdI and τdS are the dipolar demagnetizing times of spin I and S, respectively (τdI = 1/(γI μ0M0I), τdS = 1/(γS μ0M0S), where M0I and MoS are the equilibrium magnetizations of spins I and S). Note that there is no dependence of MI+ on t1, since this “homomolecular” zero-quantum coherence has no evolution during the first time period. In contrast, the signal arising from I-S (mixed spin) iZQCs of the form I+S− is given by [28]:

| (2) |

If I and S are water and fat, respectively, the frequency of this “heteromolecular” peak in the indirectly detected dimension is ωI−ωS. Since ωI has a linear dependence on temperature while ωS does not, the difference between these frequencies has a linear dependence on absolute temperature.

Figure 1.

a) Standard iZQC CRAZED sequence. The rectangular pulses indicate broadband pulses given to all spins in the system, while the Gaussian shape indicates a frequency selective pulse. In this sequence, the growth of the iMQC signal is severely limited by inhomogeneous broadening. 1b) The addition of a refocusing pulse significantly improves the intensity of the iZQC signal. 1c) Modified CRAZED pulse sequence for the detection of mixed spin iZQCs. The coherences evolve during t1 as iZQC, and then only the mixed spin coherences are converted to iDQCs and survive the DQC filter of {G-τ- π/2-2G-2 τ}. The resulting signal is only that of the mixed spin iMQCs which have a characteristic temperature sensitive iZQC frequency from their evolution time during t1.

The effects of inhomogeneous broadening and relaxation on the CRAZED and related sequences have been extensively discussed elsewhere [29; 30; 31; 32]. The most important practical limit for an iZQC temperature imaging sequence is the one where T2*<<T2I,T2S<<τdS, τdI,T1I,T1S. In that limit, the sequence in Figure 1a is severely compromised, as the iZQC signal is zero at t2=0 and its linear growth with time is impeded by inhomogeneous broadening. A more practical sequence includes an echo pulse with TE≈T2 (Figure 1b). In this case, at the peak of the echo, the components of detected I magnetization that evolved during t1 as homomolecular (eq. 3) or heteromolecular signals (eq. 4, 5) are [28]:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

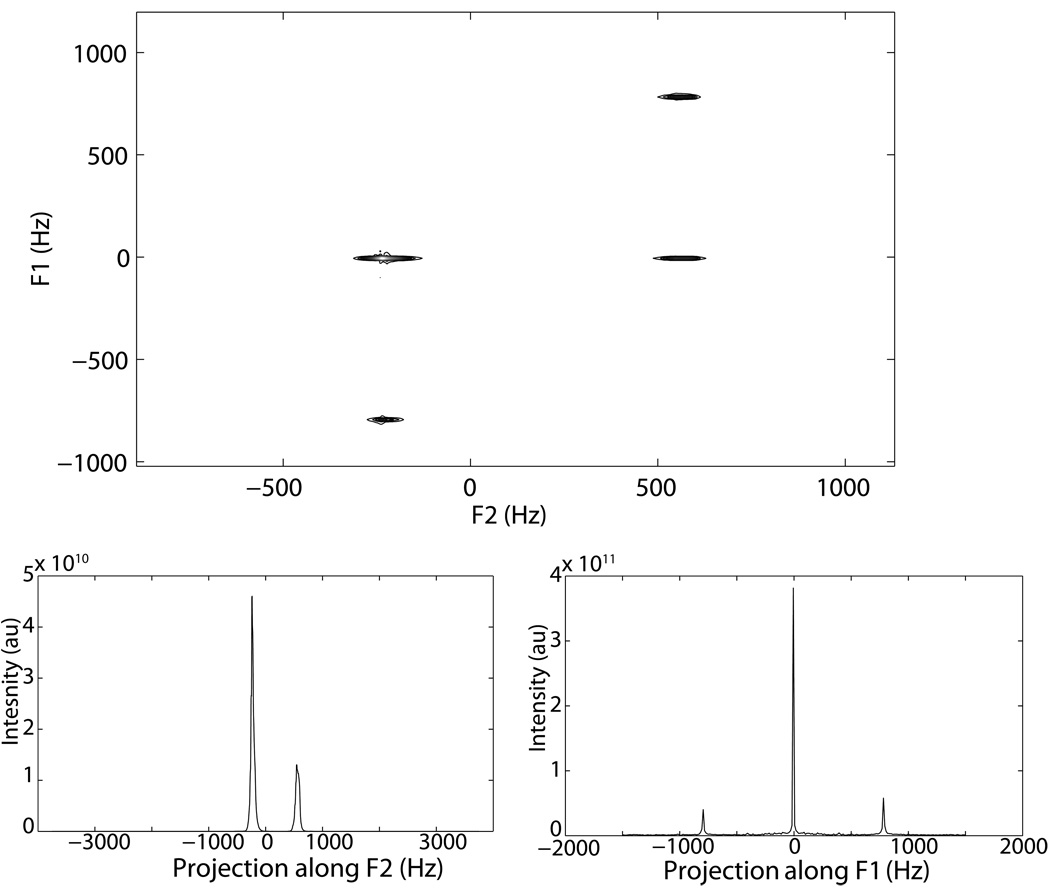

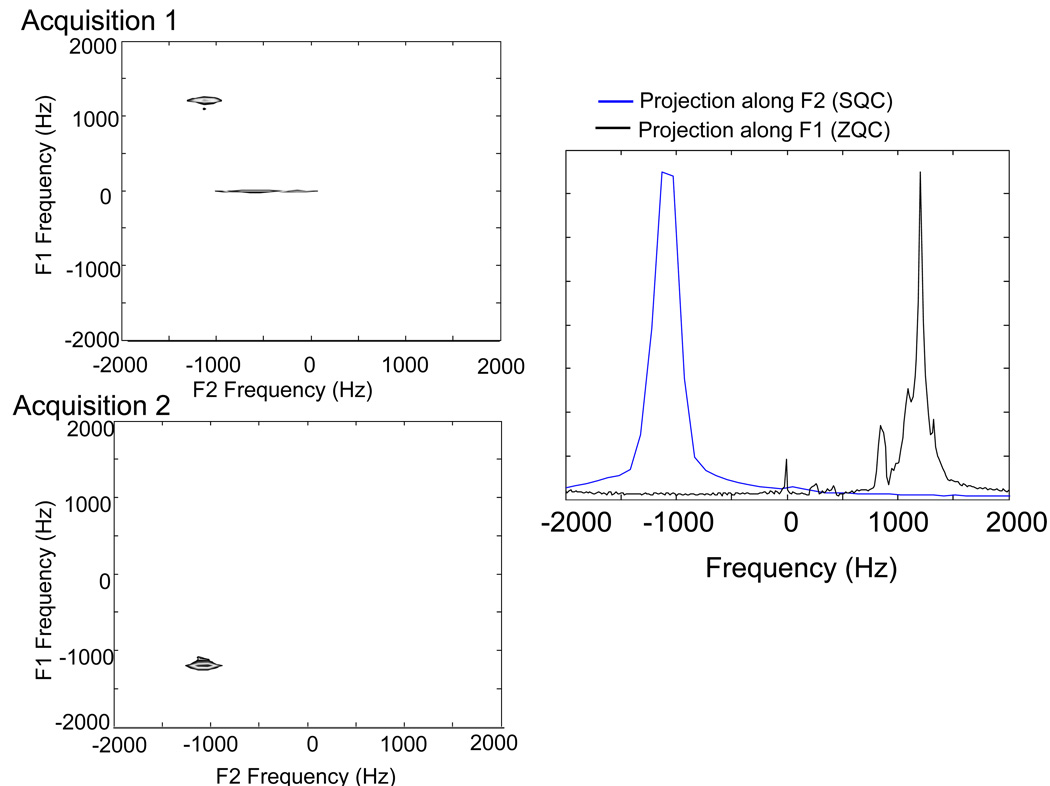

Eqs. 4 and 5 show the heteromolecular peak for I+S− and I−S+, respectively. The heteromolecular peak is significantly smaller than the homomolecular peak in the common case where MoS<<MoI (Figure 2 shows an example). The majority of the signal comes from the strong solvent signal, which in an imaging application would dominate the signal of the image. Further complicating matters, unlike other iMQC sequences, the iZQC sequence lacks a gradient filter that can remove SQC contamination generated by the mixing pulse.

Figure 2.

Top: Standard 2D iZQC spectrum of a water-acetone sample. Bottom left: Projection along F2 (direct, SQC dimension). Bottom right: Projection along F1 (indirect, iZQC dimension). In this spectrum, the bulk of the signal is coming from the temperature insensitive same spin iZQC signal (such as that from water-water or fat-fat iZQCs). If the standard iZQC sequence was used to image temperature, the bulk of the signal in that image would be temperature insensitive signal, thus contaminating the temperature sensitivity of the image.

2.2 Single acquisition HOT imaging

In order to accurately image temperature, it is crucial to create a filter that can cleanly remove contamination from same spin iZQCs, as well as from conventional magnetization. The basic pulse sequence used to image temperature is shown in figure 1c. The frequency selective inversion pulse inverts only one chemical species, causing the mixed spin iZQC to convert to mixed spin iDQCs and vice versa [1;9;16] [33]:

| (6) |

This pulse has no net effect on same spin iMQCs:

| (7) |

Applying a double quantum filter of [τ,GTz-θmix−2τ,2GTz] dephases all coherences except those which existed as iDQCs during τ and were transferred into iSQCs (e.g., I+Sz) by the mixing pulse [34; 35]. Since the unbalanced gradients flank the mixing pulse, they also efficiently dephase the SQCs created before or after the mixing pulse (figure 1c), reducing the large static SQC component of the signal. In addition, this extra twist in the coherence pathway creates different routes for the iMQCs between equivalent and unequal spin pairs, so that standard methods can now be used to isolate the desired water-fat iZQCs. For example, of the signals preserved by the double quantum filter, only water-fat iZQCs are unaffected by the phase cycling of the first excitation pulse. Similarly, the phase of the selective inversion pulse has different effects on same-spin versus mixed-spin coherences, with a π/2 shift reversing the water-fat coherences, but leaving the water-water coherences unaffected.

With the selective inversion pulse, the phase reversal is more formally a change in coherence order. Since this modified HOMOGENIZED sequence only transfers coherences between water and off-resonance spins into observable signal, we refer to it as HOMOGENIZED with Off-resonance Transfer, or the HOT sequence.

2.3 Two-Window HOT

The previously described sequence can cleanly image a single temperature-sensitive coherence. It and all of the other iMQC sequences developed to remove inhomogeneous broadening [24; 36; 37; 38] are inherently two-dimensional sequences. There is a good reason why there are no clinical applications of such sequences: the sequence often requires several hours to acquire an image, and such sequences are highly susceptible to instabilities such as motion. Several methods have been used to speed up the sequence, including EPI acquisitions [39; 40] and RARE acquisitions [41; 42]. The EPI acquisitions impose geometric distortions as well as an intolerable T2* decay on the signal, making it an unacceptable method for accelerating the acquisition. The RARE based sequences work well, but for clinical applications, the sequence quickly approaches SAR limitations for large RARE factors.

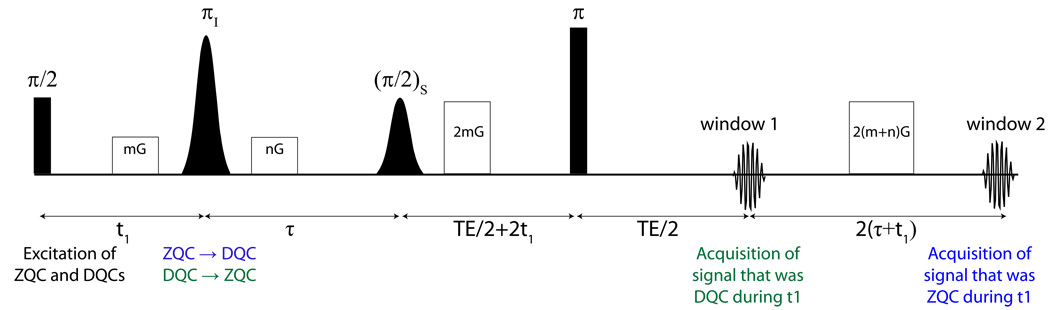

The primary reason why the experiment requires so much time is that many t1 points are required to acquire an accurate temperature map, and each t1 point represents the acquisition of an entire image. Ultrafast two-dimensional sequences are one approach to solve this issue [43; 44] and were demonstrated to be feasible for iMQC experiments [38; 45; 46; 47]. In all of these cases, the available signal from the entire sample (or from each voxel in an image) is subdivided to acquire multiple t1 points. However, the most important parameter for a temperature image is a single frequency, which requires far fewer points. As we previously noted [1], it is possible to use multiple pathways to acquire several images (two or more, as shown below) with different effective evolution at the water-fat frequency and with each image containing the full signal. The acquisition of the two signals with different evolution reduces the number of repetitions (since two t1 points are acquired from each scan) and allows us to acquire temperature images both in vivo [1] and in vitro in only two minutes. The pulse sequence for two-window HOT is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Two window iMQC temperature imaging sequence. In this pulse sequence both signals that evolved during t1 as iDQC and iZQC are collected. The first pathway starts with signal that is iDQC during t1, which is converted to iZQC by the selective π pulse and is acquired during the first acquisition period. The second pathway uses signal that was iZQC during t1 and was converted to iDQC by the selective π pulse, which is acquired in the second acquisition period.

To apply this idea to thermometry, the mixed-spin coherences are isolated in a manner very similar to that used for the single acquisition HOT sequence. Two coherence pathways exist, one in which iDQCs are converted to iZQC and the other where iZQCs are converted to iDQCs. In the first pathway (iDQC to iZQC), the signal is refocused in the first acquisition window (see supplemental information for more details). Briefly, the signal starts as iDQC (I+S+). The, and the gradient mGT causes a phase shift of 2mGT and the coherence acquires 2t1 of evolution. It is converted to an iZQC by the selective inversion pulse, where the subsequent gradient nGT has no effect, and the coherence evolves at the iZQC (ωI−ωS) frequency during τ. The selective mixing pulse then reintroduces the dipolar field, and the signal is refocused by the 2mGT gradient and the 2t1 evolution time.

The second coherence pathway takes iZQCs and converts them to iDQCs. During the t1 interval, the signal is iZQC and experiences no gradient and evolves at the iZQC frequency (ωI−ωS). The selective inversion pulse converts it to iDQC, where it evolves at the iDQC frequency (ωI+ωS) and acquires a phase shift 2nGT from the gradient. The coherence is converted to SQC by the mixing pulse, and it acquires an additional phase shift of 2mGT (causing a net effect of the gradients to be 2(m+n)GT) and evolves for an additional 2t1. After the refocusing pulse and the first acquisition window, a gradient of 2(m+n)GT and 2(τ+t1) of evolution refocuses the signal, and it is acquired in the second acquisition window.

Since this signal primarily arises from spins that are a correlation distance apart, γ(m+n)GT does not average to zero across the sample, and this signal is refocused. As discussed earlier, if these are replaced with inhomogeneously broadened chemical shifts, the inhomogeneous broadening would be canceled.

Adequate same-spin suppression is crucial for the success of this sequence. While experimental results have indicated that adequate same-spin suppression can be achieved simply through the extra gradient filters of this sequence, standard phase cycling methods achieve higher SNR more efficiently over multiple scan averages, and a phase cycle which is compatible with both signals is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phase Cycling for Two Window HOT

| Scan # | 90 | 180I | 90S | Rcvr 1 | Rcvr 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

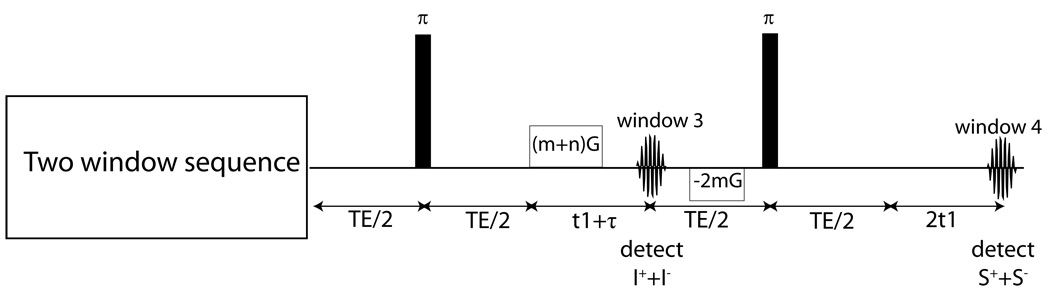

2.4 Four-window HOT

The two-window HOT sequence enables rapid acquisition (~2 min) of temperature images. An extension of this sequence can be made in which two standard single quantum (SQC) images are also acquired. These SQC images serve as anatomical reference images for the temperature images, allowing for easy co-registration of the temperature maps. In addition, each of the SQC acquisition windows detects signal from different chemical components. This separation of different chemical species can allow for unique information to be obtained from the SQC images, in addition to the temperature information gained from the first two windows.

The pulse sequence for four-window HOT is shown in figure 4. It is essentially the same pulse sequence as the two-window sequence, except for the addition of two refocusing pulses and refocusing gradients. The details of the coherence pathways are outlined in the supplemental information. The third acquisition window collects the signal from only the I spins, and the fourth window collects the signal from only the S spins. The images acquired provide spin density images for each of the chemical species, allowing for easy co-registration of the temperature maps.

Figure 4.

Four window temperature imaging sequence. The first two acquisitions are identical to those in figure 3. The signal collected in the first two acquisitions is used to create a temperature image. The signal collected in the last two images provides a chemically selective spin density image.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Spectroscopy Results

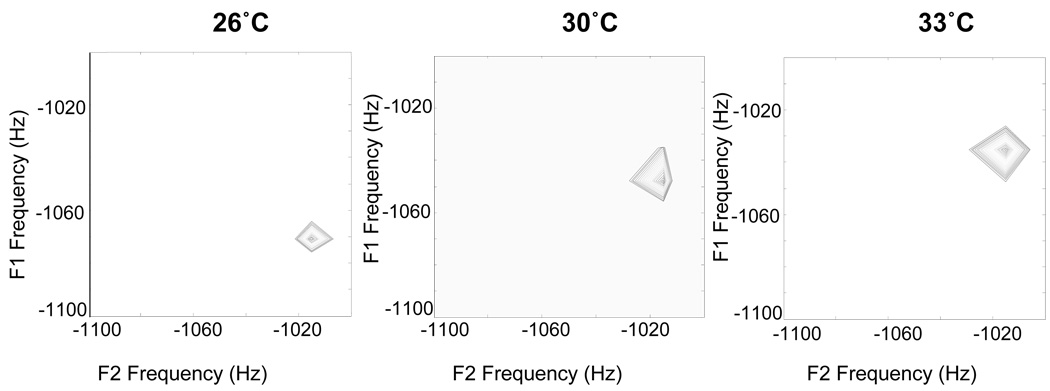

The first result necessary to establish the utility of this method was to show that the water-fat iZQC frequency did vary with temperature at the expected rate of 0.01 ppm/°C. This was equivalent to ensuring that the frequency of fat in our phantom did not vary with temperature and could serve as an accurate temperature-independent correction factor. The most direct proof of this was carried out by running (off-resonance) 2D iZQC spectroscopy on a cream sample while its temperature was held constant and repeating the experiment at various temperatures. Those results are presented in Figure 5 and verify that the ZQC frequency changes linearly with temperature, shifting by the same 0.01 ppm/°C expected for water.

Figure 5.

The frequency of the iZQC crosspeak between water and fat shifts linearly with temperature in a water-fat phantom. A graph of the frequencies detected using the HOT sequence is shown in figure 7. All spectra were taken with TE=15 ms, TR=4 s, 8 averages, 512 × 256 matrix, spectral width (direct dimension) = 12626.26 Hz, spectral width (indirect dimension) 3200 Hz, correlation distance = 0.06406 mm.

The advantages of HOT thermography are demonstrated in a 2D experiment which clearly contrasts the characteristics of the iZQC signal along the F1 dimension with those of conventional magnetization along F2. Figure 6 presents such data acquired post mortem on an obese mouse (ob/ob, Jackson Laboratories). This spectrum is of the entire mouse abdomen. This clearly demonstrates that this sequence very efficiently isolates the intended signal in each acquisition window. Furthermore, the iZQC dimension shows its hallmark of improved resolution relative to the directly detected signal. To the left of the 2D spectra, we present traces along F2 (blue), the dimension used to determine temperature in conventional methods, and F1 (black), the iMQC dimension. The iMQC peaks are insensitive to most sources of inhomogeneous broadening, and the observed frequency is almost exclusively a function of chemical shift, which reflects temperature. With the higher resolution of the iMQC spectrum, several component resonances of the fat peak are resolved, but this does not ultimately affect temperature mapping. Once the overall phase shift from these factors is established in a reference image, any changes in the phase of the image only reflect changes in the chemical shift of the water, i.e., changes in temperature.

Figure 6.

Spectra of an obese mouse post mortem demonstrate that the sequence cleanly isolates the water-fat coherence. Spectra on the left are the first (top) and second (bottom) acquisition windows. On the right are traces along F2 (blue) and F1 (black) showing narrower lines in the iZQC dimension. Scan parameters: mGT= 11 G/cm*1ms, nGT=−17 G/cm*1ms, correlation distance = 0.198 mm, TE = 40 ms, t1 = 2.5 ms, τ = 3 ms, and TR = 4.5 s.

3.2 Results from single window HOT imaging experiments

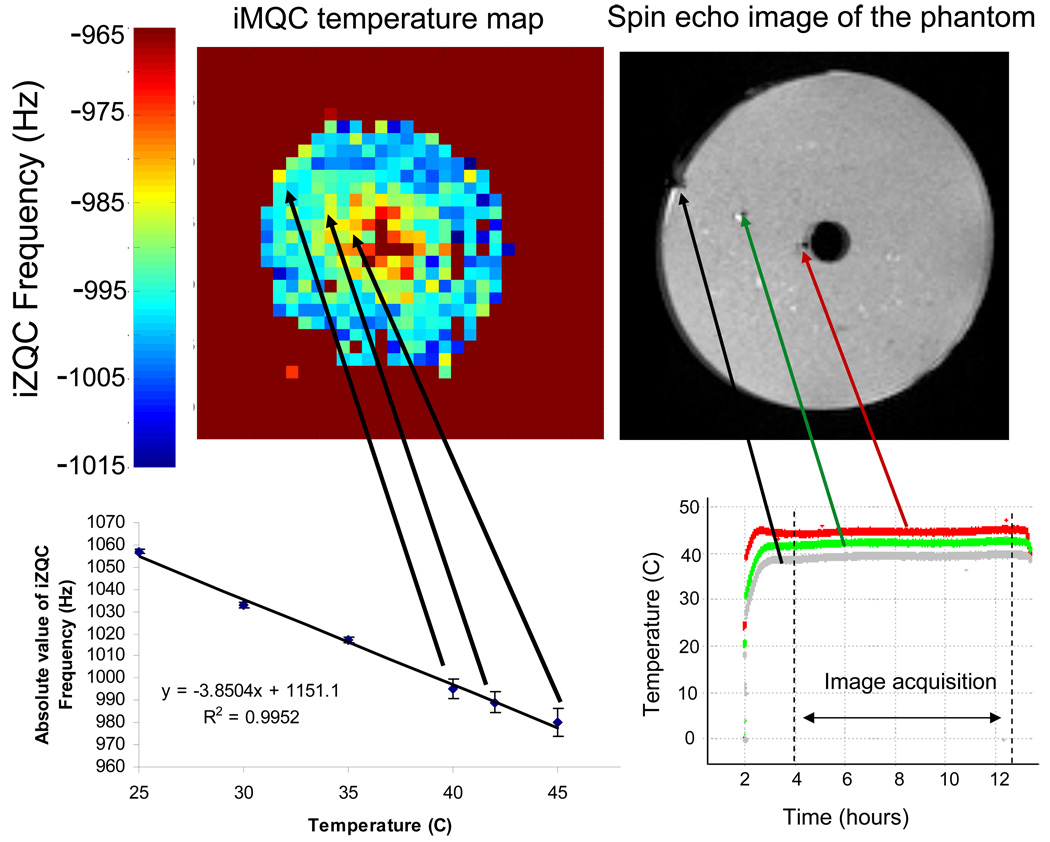

Previous work has demonstrated the accuracy of iZQC imaging in a uniformly heated phantom [1]. In those results, a liquid water/fat phantom (cream) was maintained at a uniform temperature using feedback-controlled airflow and a single thermometer affixed to the outside of the sample. Figure 7 illustrates a more realistic phantom for hyperthermic therapies. For the one-window HOT experiments, a semisolid gel of water and fat was prepared, from heavy cream and agarose, and maintained at a constant temperature gradient. The sample was set up with a continuous flow heat source (water doped with CuSO4) through its center, a cool flow of air along its perimeter, and several fiber optic temperature probes at intermediate points. Using the scale established in the previous liquid state experiments, the agreement between the fiber optic probe temperature readings and the iZQC frequencies are shown in the graph on the bottom right of figure 7. Note that the three additional data points in that figure come from single temperature imaging experiments described in [1]. The error bars for the plot of iZQC frequency vs. temperature were determined by the standard deviation of the pixels in the image. For the points coming from the phantom with the temperature gradient, the reported error comes from the standard deviation of surrounding 8 pixels. For the data points from the single temperature phantoms, the error was determined by taking the standard deviation of the entire image. The single temperature images had a standard deviation around 1 Hz, while the error in the temperature gradient image was higher, about 5 Hz. The correspondence between these and the liquid state results further establishes that iZQCs provide a measurement of temperature on an absolute scale.

Figure 7.

Right: Spin echo image of cream sample, axial slice. Arrows mark the position of the three fiber optic temperature probes, and the plot below shows the temperature recorded at each point. Top left: Temperature map of the heated sample showing the distribution of iZQC frequencies at the different temperatures. Bottom left: Graph of temperature vs. iZQC frequency. Three data points come from this experiment and the additional three data points come from single temperature measurements reported in [1]. The temperature images were acquired using a RARE acquisition, RARE factor = 4, 28 averages, 76 repetitions, 32 × 32 matrix, TE = 7.54 ms, TR = 1783 ms, t1 = 1.87 ms, FOV = 4 cm, correlation distance = 0.093474 mm, spectral width of indirect dimension = 5000 Hz.

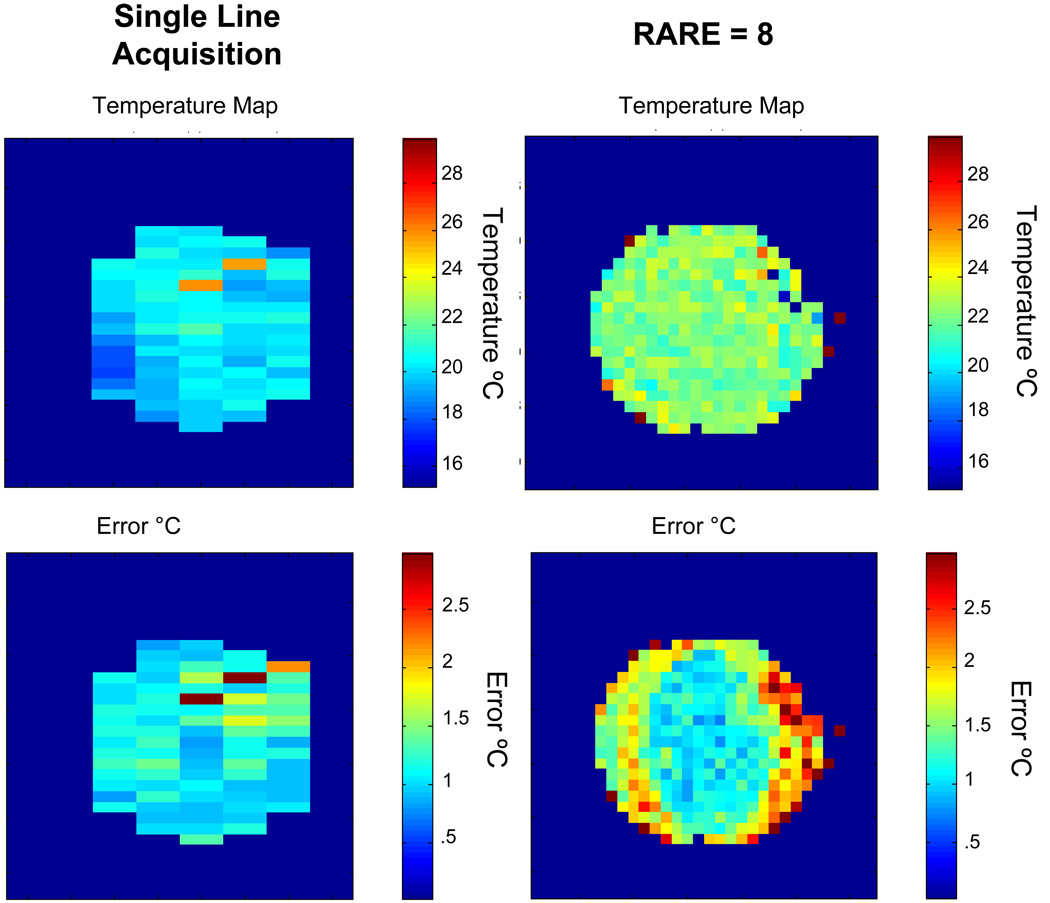

All the images had a standard deviation below 2 Hz, which means that the accuracy of the method was within 1°C, which is within the acceptable limits for hyperthermia applications. The sensitivity of this experiment is best demonstrated by using it to detect RF heating in a sample. A phantom of heavy cream was imaged using a RARE sequence, and the RARE factor was increased from 1 to 8 to increase the SAR experienced by the sample. The HOT sequence appears to be able to detect this slight temperature increase, as shown in figure 8.

Figure 8.

The sensitivity of the iMQC temperature imaging sequence is demonstrated by looking at the heating effects of RF pulses. In the top left image, the temperature map was generated using single line acquisitions. The same experiment was done again, but this time using a RARE acquisition (top right image). The figures on the bottom are confidence intervals for each of the images on the top. The application of 8 additional pulses elevates the sample temperature by about 1 °C, which is detected by the iMQC temperature map. Scan parameters for the RARE=8 experiment: 16 averages, 50 repetitions, TE = 8 ms, TR = 2 s, t1 = 1.87 ms, correlation distance = 0.06406 mm, FOV = 4cm, 32 × 32 matrix. For the single line acquisition, the scan parameters were: 16 averages, 40 repetitions, 32 × 8 matrix, TE = 15 ms, TR = 2 s, t1 = 1.87 ms, correlation distance = 0.06406 mm.

3.3 Results from two window HOT imaging experiments

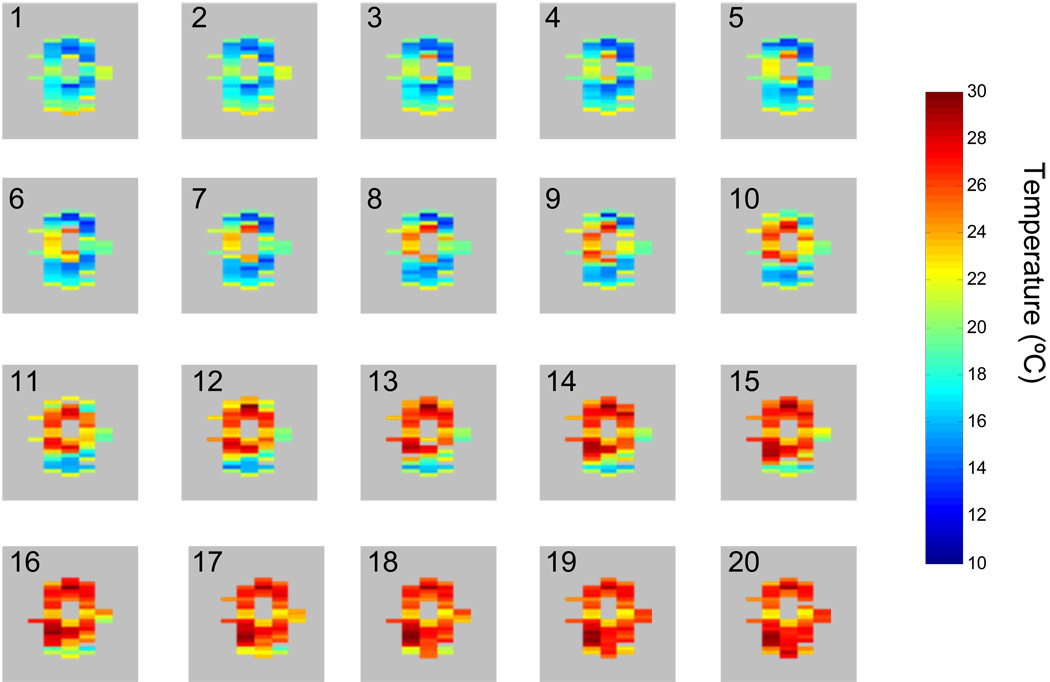

The images in the previous section were acquired using the single window HOT sequence over the course of several hours. Figure 9 demonstrates the temperature sensitivity of two window HOT thermography as applied on a sample of porcine adipose tissue. In this experiment, the temperature of the sample was controlled using a tube of heated water running through the center of the tissue. The temperature of the water was gradually increased, and the sample was imaged every two minutes using the two window HOT sequence. The images show both the dynamic heating of the sample throughout the experiment, as well as a temperature gradient between the heated core of the sample and the cooler surface of the sample. Since the frequencies of the two windows shift in opposite directions, the difference image is doubly sensitive to temperature and shifts by 6 Hz/°C.

Figure 9.

iZQC temperature maps for the heating of porcine adipose tissue acquired every 2 minutes using the two acquisition pulse sequence. Increasingly hot water was pushed through a tube running through the center of the tissue. The sample was imaged every two minutes using the two window HOT sequence. Each individual image is numbered to indicate the order of the time course of the images. In these experiments, we initially acquired ten images typically spanning 10 ms of τ evolution. Once these scans verified iZQC evolution, the initial temperature map was made by fitting the phases of images 2 and 7 of the series. Subsequent dynamic thermometry was performed by repeatedly running the scan at the τ equivalent to image 7, and phase changes in each window were related to temperature changes. Temperature near the core was seen to increase from 14°C to 36°C as monitored by a temperature probe. FOV = 4 cm TE = 40 ms; TR = 2 s; mGT = 1 ms*8.4 G/cm; nGT = 1 ms*-21 G/cm; correlation distance = 0.0945 mm, t1 = 3 ms; τ = 10.66 ms.

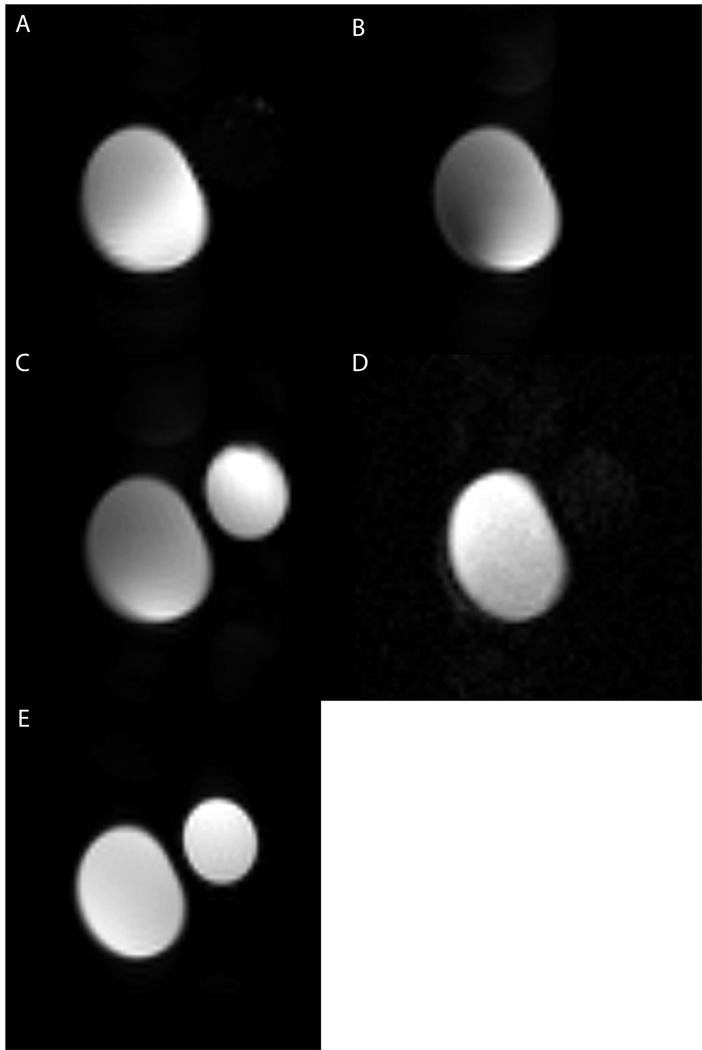

3.4 Imaging Results from the four window HOT sequence

The four window HOT sequence allows for the imaging of both the iMQC temperature information as well as the acquisition of two additional SQC images. The SQC images separate the sample by chemical shift – one window showing the distribution of the on-resonance spins, and the other window showing the off resonance spins. Figure 10 shows the results from a four window HOT sequence on a water/acetone phantom. The phantom has a 50/50 water and acetone mixture in the larger tube, and just water in the smaller tube (standard spin echo image of the two tubes is figure 10e). In acquisition windows 1 (figure 10a) and 2 (figure 10b) only the larger tube shows up since those sequences only image samples in which there is a mixture of water and acetone (or on and off – resonance spins). In acquisition window 3 (figure 10c), both tubes show up, since that acquisition window detects the on-resonance water spins, which are found in both tubes. Finally, in window 4 (figure 10d) there is only the larger water and acetone tube, since that acquisition only detects the off resonance acetone spins.

Figure 10.

Four window HOT on a tube of water and acetone next to a tube of water. Scan was done at 8.45 T, 64 × 64 matrix size, FOV = 4 cm, 4 averages, TE/2 = 100 ms. Correlation gradient m = 23 G/cm, correlation gradient n = 36.8 G/cm, t1 = 4.1 ms, correlation distance = 0.0863 mm, τ = 12.5 ms, slice thickness = 2 cm. In figure 10A and B, we detect only the larger tube with a mixture of water and acetone. In C we detect both tubes, since they both contain water. In D, we detect only the larger tube, since it is the only one with acetone. Figure 10E shows a standard spin echo of this sample. All the images are on independent intensity scales. The SNR of A (water + acetone tube) is 488, B (water + acetone tube) is 251, C (water + acetone tube) is 418 and (water only tube) is 595 and D (water + acetone tube) is 33.

3. Conclusions

We have demonstrated in several phantoms that iMQCs can be used to detect temperature on an absolute scale, by isolating the temperature-sensitive, inhomogeneity-insensitive iMQCs between water and fat spins. We present an analysis of this sequence and the mechanisms by which it isolates the desired signals. Using a water-fat phantom of heavy whipping cream, we demonstrated that this sequence could be used to acquire temperature maps which are as accurate as conventional methods. We have also demonstrated that the method appears to be sensitive enough to detect RF heating from standard imaging protocols. Finally, we have demonstrated that a simple extension of the temperature imaging sequence can be used to provide chemically-selective spin density images.

Temperature imaging methods using iMQCs are an exciting development in MR imaging of temperature, providing for the first time, the ability to use MR to image temperature on an absolute scale. The high level of accuracy of iMQC temperature measurements, combined with the intrinsic insensitivity of the method to motion [1] and susceptibility effects, make iMQC temperature imaging a promising development in MR temperature imaging. In particular, iMQC methods have the potential to allow temperature imaging in tissues that were previously inaccessible due to large susceptibility differences and high concentrations of lipids, such as the breast. While this technique is limited to situations in which there is a non-temperature sensitive reference peak available, there are several tissues in which this is the case. In a realistic application, the mixed spin iMQC signal between water and a metabolite peak will be approximately 10% of the metabolite peak. Even when the signal is small, as in the brain, accepting voxels slightly larger than would be used for direct spectroscopic detection would permit temperature detection. Since the correlation distance is independent of voxel size, larger voxels do not degrade the temperature accuracy. We believe that the HOT sequence can be adapted to study a wide range of applications relating to temperature, including applications in which standard PFS techniques fail due to motion, such as in the bowel or in the chest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH grants R01-EB2122, NCI-5P01-CA42745 and NCI CA42745.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Galiana G, Branca RT, Jenista ER, Warren WS. Accurate temperature imaging based on intermolecular coherences in magnetic resonance. Science. 2008;322:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1163242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wust P, Hildebrandt B, Sreenivasa G, Rau B, Gellermann J, Riess H, Felix R, Schlag PM. Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer. Lancet Oncology. 2002;3:487–497. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Senneville BD, Quesson B, Moonen CTW. Magnetic resonance temperature imaging. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2005;21:515–531. doi: 10.1080/02656730500133785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gellermann, W JW, Feussner A, Fähling H, Nadobny J, Hildebrandt B, Felix R, Wust P. Methods and potentials of magnetic resonance imaging for monitoring radiofrequency hyperthermia in a hybrid system. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2005;21 doi: 10.1080/02656730500070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.P.A. Technologies. High-intensity Focused Ultrasound. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mougenot C, Quesson B, de Senneville BD, de Oliveira PL, Sprinkhuizen S, Palussiere J, Grenier N, Moonen CT. Three-dimensional spatial and temporal temperature control with MR thermometry-guided focused ultrasound (MRgHIFU) Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:603–614. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDannold N, Tempany C, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Evaluation of referenceless thermometry in MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery of uterine fibroids. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:1026–1032. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demura K, Morikawa S, Murakami K, Sato K, Shiomi H, Naka S, Kurumi Y, Inubushi T, Tani T. An easy-to-use microwave hyperthermia system combined with spatially resolved MR temperature maps: phantom and animal studies. J Surg Res. 2006;135:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quesson B, de Zwart JA, Moonen CTW. Magnetic resonance temperature imaging for guidance of thermotherapy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2000;12:525–533. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200010)12:4<525::aid-jmri3>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hindman JC. Proton Resonance Shift of Water in the Gas and Liquid States. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1966;44:4582–4592. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagayaki K, Koichi O, Andrew HC, Kullervo H, Ferenc AJ. Temperature Mapping using the water proton chemical shift: A chemical shift selective phase mapping method. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1997;38:845–851. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abragam A. Principles of Nuclear Magnetism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu M, Bashir A, Ackerman JJ, Yablonskiy DA. Improved calibration technique for in vivo proton MRS thermometry for brain temperature measurement. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60:536–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hekmatyar SK, Paige H, Sait Kubilay P, Andriy B, Navin B. Noninvasive MR thermometry using paramagnetic lanthanide complexes of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclodoecane-alpha,alpha',alpha",alpha'"-tetramethyl-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTMA4-) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53:294–303. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbot RL, Greg T, Ben K. Validation of a Noninvasive Method to Measure Brain Temperature In Vivo Using 1H NMR Spectroscopy. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;64:1224–1230. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64031224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernest BC, Patricia CDS, Juliet P, Ann L. The Estimation of Local Brain Temperature by in Vivo 1H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;33:862–867. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters RD, Hinks RS, Henkelman RM. Heat-source orientation and geometry dependence in proton-resonance frequency shift magnetic resonance thermometry. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;41:909–918. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199905)41:5<909::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters RD, Henkelman RM. Proton-resonance frequency shift MR thermometry is affected by changes in the electrical conductivity of tissue. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;43:62–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<62::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Depoorter J. NONINVASIVE MRI THERMOMETRY WITH THE PROTON-RESONANCE FREQUENCY METHOD - STUDY OF SUSCEPTIBILITY EFFECTS. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34:359–367. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprinkhuizen S, Konings M, Bakker C, Bartels L. Heating of fat leads to significant temperature errors in PRFS based MR thermometry. Proceedings 17th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Honolulu. 2009. p. 2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stollberger R, Ascher PW, Huber D, Renhart W, Radner H, Ebner F. Temperature monitoring of interstitial thermal tissue coagulation using MR phase images. Jmri-Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1998;8:188–196. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vathyam S, Lee S, Warren WS. Homogeneous NMR spectra in inhomogeneous fields. Science. 1996;272:92–96. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YY, Ahn S, Murali N, Brey W, Bowers CR, Warren WS. High-resolution, > 1 GHz NMR in unstable magnetic fields. Physical Review Letters. 2000;85:3732–3735. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balla D, Faber C. Solvent suppression in liquid state NMR with selective intermolecular zero-quantum coherences. Chemical Physics Letters. 2004;393:464–469. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachiller PR, Ahn S, Warren WS. Detection of intermolecular heteronuclear multiple-quantum coherences in solution NMR. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series A. 1996;122:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter W, Lee SH, Warren WS, He QH. Imaging with Intermolecular Multiple-Quantum Coherences in Solution Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance. Science. 1995;267:654–657. doi: 10.1126/science.7839140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warren WS, Richter W, Andreotti AH, Farmer BT. Generation of Impossible Cross-Peaks between Bulk Water and Biomolecules in Solution Nmr. Science. 1993;262:2005–2009. doi: 10.1126/science.8266096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn S, Lisitza N, Warren WS. Intermolecular zero-quantum coherences of multi-component spin systems in solution NMR. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1998;133:266–272. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahn S, Warren WS. Effects of intermolecular dipolar couplings in solution NMR in separated time intervals: the competition for coherence transfer pathways. Chemical Physics Letters. 1998;291:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn S, Lee S, Warren WS. The competition between intramolecular J couplings, radiation damping, and intermolecular dipolar couplings in two-dimensional solution nuclear magnetic resonance. Molecular Physics. 1998;95:769–785. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, Richter W, Vathyam S, Warren WS. Quantum treatment of the effects of dipole-dipole interactions in liquid nuclear magnetic resonance. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1996;105:874–900. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z, Zhong JH. Unconventional diffusion behaviors of intermolecular multiple-quantum coherences in nuclear magnetic resonance. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2001;114:5642–5653. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiuhong H, Pavel S, Regina JH, Donald RL, Jeffrey CW, Veerle Ilse Julie B. In vivo MR spectroscopic imaging of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in healthy and cancerous breast tissues by selective multiple-quantum coherence transfer (Sel-MQC): A preliminary study. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;58:1079–1085. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branca RT, Silvia C, Bruno M. About the CRAZED sequence. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part A. 2004;21A:22–36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter W, Warren WS. Intermolecular multiple quantum coherences in liquids. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance. 2000;12:396–409. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Lin MJ, Chen Z, Cai SH, Zhong JH. High-resolution intermolecular zero-quantum coherence spectroscopy under inhomogeneous fields with effective solvent suppression. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2007;9:6231–6240. doi: 10.1039/b709154k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Z, Chen ZW, Zhong JH. High-resolution NMR spectra in inhomogeneous fields via IDEAL (intermolecular dipolar-interaction enhanced all lines) method. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:446–447. doi: 10.1021/ja036491f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Z, Cai SH, Chen ZW, Zhong JH. Fast acquisition of high-resolution NMR spectra in inhomogeneous fields via intermolecular double-quantum coherences. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2009;130:11. doi: 10.1063/1.3076046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jianhui Z, Edmund K, Zhong C. fMRI of auditory stimulation with intermolecular double-quantum coherences (iDQCs) at 1.5T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;45:356–364. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200103)45:3<356::aid-mrm1046>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreas S, Thies HJ, Harald EM. Functional magnetic resonance imaging with intermolecular double-quantum coherences at 3 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53:1402–1408. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hennig J, Nauerth A, Friedburg H. RARE IMAGING - A FAST IMAGING METHOD FOR CLINICAL MR. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1986;3:823–833. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider JT, Faber C. BOLD imaging in the mouse brain using a TurboCRAZED sequence at high magnetic fields. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60:850–859. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frydman L, Scherf T, Lupulescu A. The acquisition of multidimensional NMR spectra within a single scan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:15858–15862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frydman L, Lupulescu A, Scherf T. Principles and features of single-scan two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:9204–9217. doi: 10.1021/ja030055b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galiana G, Branca RT, Warren WS. Ultrafast intermolecular zero quantum spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:17574–17575. doi: 10.1021/ja054463m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen X, Lin MJ, Chen Z, Zhong JH. Fast Acquisition Scheme for Achieving High-Resolution MRS With J-Scaling Under Inhomogeneous Fields. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61:775–784. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balla DZ, Melkus G, Faber C. Spatially localized intermolecular zero-quantum coherence spectroscopy for in vivo applications. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;56:745–753. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.