Abstract

Information campaigns to increase tax compliance could be framed in different ways. They can either highlight the potential gains when tax compliance is high, or the potential losses when compliance is low. According to regulatory focus theory, such framing should be most effective when it is congruent with the promotion or prevention focus of its recipients. Two studies confirmed the hypothesized interaction effects between recipients' regulatory focus and framing of information campaigns, with tax compliance being highest under conditions of regulatory fit. To address taxpayers effectively, information campaigns by tax authorities should consider the positive and negative framing of information, and the moderating effect of recipients' regulatory focus.

Keywords: Regulatory focus, Regulatory fit, Goal-framing, Tax compliance

Tax payments represent a social dilemma with colliding individual and collective interests. The financial basis for effective political and economic activities of the government is solid as long as the state succeeds in motivating citizens to cooperate rather than to defect. If a majority of citizens engages in tax avoidance and evasion, provision of public goods and services is at risk (e.g., van Lange, Liebrand, Messick, & Wilke, 1992). Despite temptations to cheat, people in many countries keep up relatively high tax morale and seem to accept their duty to pay taxes (Braithwaite, 2003; James & Alley, 2002; Kirchler, 2007). Nevertheless, “taxes” have a negative connotation, are associated with an expensive and inefficient management style of politicians and often linked not only to the loss of money but also - especially in the case of self-employment - to restrictions of personal freedom in deciding how to spend and invest one's “own” money (Kirchler, 1998). Information campaigns on taxes and spending policy of the government as well as the provision of public goods can improve both citizens' understanding and acceptance of taxes and their compliance. Tax compliance is likely to increase if the tax system is perceived as being transparent, fair, and trustworthy, and when tax knowledge increases (e.g., Kirchler, 2007). This article examines the differential effectiveness of information campaigns. It is assumed that information campaigns that focus on potential gains are more effective when recipients are under promotion focus, and that campaigns that focus on potential losses are more effective when recipients are under prevention focus.

1. Promoting tax compliance by information campaigns

Neoclassical economics postulates that taxpayers consider audit probability and fines in case of tax evasion and comply with the law only if audits are likely and fines are high (Allingham & Sandmo, 1972). The effect of audits and fines has, however, often been disputed (e.g., Andreoni, Erard, & Feinstein, 1998) and without doubt there are other than purely rational-economic variables determining tax behaviour. Moreover, under some circumstances, audits and fines may have the opposite effects than expected (e.g., Eichenberger & Frey, 2002; Kirchler, 2007). If the deterring effect of audits and fines is low, strategies which aim to promote tax compliance should be applied (Pommerehne & Weck-Hannemann, 1992). Cooperation with tax authorities could be promoted by various media. Information campaigns focusing on improving citizens' knowledge about taxes, the advantages of taxes for the collective and fairness of the tax system could be useful to improve acceptance of taxes, build a trustful relationship between citizens, government and tax authorities, and promote development of norms of cooperation and tax morale (Eichenberger & Frey, 2002).

Information campaigns and advertisement of public services in various media have sometimes been used to reach a broad cross-section of the population, with the aim to reach acceptance of political projects in general and tax issues in particular. Roberts (1994) created six 30-second announcements transmitted via TV, and successfully showed that taxpayers' attitudes changed towards fairness and compliance. McGraw and Scholz (1988) tested the effect of conscience appeals or sanction threats, sent via video tapes. Apart from information and advertisement spots sent via TV, letters sent out to households proved to be an adequate means for informing citizens and for promoting tax compliance. White, Curratola and Samson (1990) demonstrated that information and explanation about legislative intents can positively influence taxpayers' acceptance of taxes and fairness perceptions. Taylor and Wenzel (2001) compared the effects of letters in an either soft and cooperative or hard and threatening tone. All forms of information campaigns have the potential to positively affect taxpayers' willingness to cooperate. Hasseldine and Hite (2003) compared positively and negatively framed information and found an interaction effect with gender: Male participants were more compliant after reading a negatively framed scenario, whereas females were more cooperative after reading the positively framed message.

Information campaigns directed at informing taxpayers about the necessity of taxes for the provision of public goods could stress the advantages for citizens if they pay their taxes correctly or disadvantages in case of non-cooperation. In marketing and health contexts, the focus on advantages or disadvantages had different effects on recipients. Also, for promoting tax compliance, goal-framing of information should be considered.

2. Goal-framing

Goal-framing refers to options in choice situations which either can be presented as gains or losses. Positive goal-framing describes possible gains, while negative goal-framing emphasizes possible unpleasant consequences (Wheatley & Oshikawa, 1970).

Recipients of information may pursue different goals when choosing between options to comply or not to comply. They may either focus on gains or try to avoid losses. If the wording of a message corresponds to the goals which recipients pursue, the message is likely to be more effective (Reber, Winkielman, & Schwarz, 1998) and more motivating (Spiegel, Grant-Pillow, & Higgins, 2004) compared to messages framed in contrast to recipients' goals. For instance, if recipients try to reach positive goals such as improving stamina through sport activities, an information campaign should focus on the potential gains: “Doing sports on a regular basis can improve your stamina and you will feel fit!” On the other hand, if recipients seek to avoid negative results, e.g., doing sports in order to prevent a reduction of stamina, an information campaign should focus on the potential loss in case of no sports: “Without sports on a regular basis your stamina will decrease and you will not feel fit anymore!”

Ganzach and Karsahi (1995) underline the relevance of goal-framing in commercial advertisements. In their study on strategies to increase credit card use, information framed negatively stressed the disadvantages of paying cash, while a positive goal-frame stressed the advantage of paying by credit card. In non-commercial advertisements, goal-framings are frequently used in health promotion contexts. Its effect has been confirmed for many health issues such as sexually-transmittable diseases (Block & Keller, 1995), breast cancer prevention through self-examination (Meyerowitz & Chaiken, 1987), the usage of dental floss (Mann, Sherman, & Updegraff, 2004), sunscreen (Detweiler, Bedell, Salovey, Pronin, & Rothman, 1999), skin cancer prevention (Rothman, Salovey, Antone, Keough, & Martin, 1993), and the benefits of a balanced diet (Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004; Spiegel, Grant-Pillow, & Higgins, 2004). In the context of tax behaviour, goal-framing has largely been neglected so far. One exception is the study by Hasseldine and Hite (2003) who presented participants with either the positive consequences of compliance or the negative consequences of non-compliance. Female participants showed higher compliance with the positively framed text, and male participants with the negatively framed text. These differences could be due to gender differences in regulatory focus. Several studies support a strong effect of regulatory focus (e.g., Holler, Dobnig, & Kirchler, 2007; Spiegel, Grant-Pillow, & Higgins, 2004) for self-regulation.

3. Regulatory focus as a moderator of goal-framing

In regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997, 1998), promotion and prevention focus are viewed as two independent motivational self-regulatory systems. Under promotion focus, people are oriented more strongly towards winning than towards losing, and towards achieving potential gains. The main focus of goal pursuit is on the satisfaction of ideals, hopes, and wishes, and the needs most prominent are growth and self-actualization. Under prevention focus, people are oriented more strongly towards losing than towards winning, and towards avoiding potential losses. The main focus of goal pursuit is on the fulfilment of obligations and on satisfying the expectation of other people; security needs are most prominent. Regulatory focus depends on both a person's disposition and on the situation. Dispositional regulatory focus describes interindividual differences in motivational self-regulation. Situational regulatory focus describes the motivational self-regulation that is evoked by specific characteristics of the situation. Situations in which it is important to avoid errors correspond to prevention focus; situations in which it is important to realize gains correspond to promotion focus. Promotion and prevention focus coordinate human activities from goal setting to goal maintenance and goal achievement (Holler, Fellner, & Kirchler, 2005) and also moderate the efficiency of goal-framings (Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004; Holler, Dobnig, & Kirchler, 2007; Mann, Sherman, & Updegraff, 2004; Spiegel, Grant-Pillow, & Higgins, 2004). Depending on the focus of self-regulation, people do not only choose different goals (Brendl & Higgins, 1996) but also different strategies in goal achievement (Higgins, 1997, 1998). Under promotion focus, people try to succeed by means of eagerness. Under prevention focus, people try to fulfill their duties and obligations by means of vigilance.

If a recipient's regulatory focus matches the goal-framing of a message, communication is likely to be more effective (Aaker & Lee, 2001; Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004; Chernev, 2004; Fellner, Kirchler, & Holler, 2004; Werth, Mayer, & Mussweiler, 2006) because information is processed more easily (Gierl, 2005). This congruency between regulatory focus and framing of information is called regulatory fit (Higgins, 2000). It positively affects motivational strength (Spiegel, Grant-Pillow, & Higgins, 2004) as well as moral evaluations of public policy programmes (Camacho, Higgins, & Luger, 2003).

In the following, we present two studies on the effect of the framing of information about taxes and regulatory focus of recipients on (intended) tax compliance. It is hypothesized that tax compliance is influenced by an interaction effect between recipients' regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention focus) and goal-framing (positively vs. negatively framed information about taxes, public spending, and the provision of public goods). The efficiency of an information campaign should depend on its fit with recipients' regulatory focus. Under conditions of regulatory fit, i.e., congruence, tax compliance should be higher.

4. Study 1: Dispositional regulatory focus, goal framing and tax compliance

In the first study, we examine the influence of dispositional regulatory focus and goal-framing on intended tax compliance. We assume that fit between framing of information and participants' regulatory focus leads to higher tax compliance. Taxpayers with promotion focus should be more willing to pay their taxes honestly after having read a positively framed text about public spending and provision of public goods. Taxpayers with prevention focus should indicate being more honest after having read a negatively framed text.

4.1 Method

Participants

One hundred and fifty two taxpayers participated in the study. Due to missing values in one or more key variables, four participants had to be excluded, leaving 148 (80 men, 68 women) for further analyses. Mean age was 33.93 years (SD = 8.98). The sample consisted of 132 employees; the remaining participants were self-employed professionals. Data was collected at several evening classes at a college of higher education in Vienna, Austria.

Design

A 3 by 2 between-subjects design with regulatory focus (promotion vs. indifferent vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) as independent variables was used to investigate effects on tax compliance as dependent variable. Participants were randomly assigned to framing conditions. Regulatory focus of participants was assessed by a questionnaire (Fellner, Holler, Kirchler, & Schabmann, 2007) which yielded data to split the sample into a group with predominant promotion focus and a group with predominant prevention focus.

Material and procedure

Participants filled out a questionnaire which consisted of a short introduction, (a) the regulatory focus scale, (b) the information campaign about public income and spending and provision of public goods, (c) a tax filing scenario and a scale assessing tax compliance and (d) questions on socio-demographic characteristics. It took about 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

(a) The Regulatory Focus Scale (RFS) by Fellner et al. (2007) was used to assess participants' dispositional promotion and prevention orientation. This 10-item scale measures respondents' working style, achievement related attitudes, and proneness to fulfil others' expectations. The scale is composed of two subscales measuring promotion focus (e.g., “I like to do things in a new way”) and prevention focus (e.g., “I always try to make my work as accurate and error-free as possible”). A factor analysis with a two-factor solution indicated that some items loaded on both factors and had to be excluded. The final promotion score was computed as an average of four items (“I prefer to work without instructions from others”; “I like to do things in a new way”, “I generally solve problems creatively”, “I like trying out lots of different things, and am often successful in doing so”, 7-point scale, Cronbach Alpha = .63), the prevention score as an average of three items (“For me, it is very important to carry out the obligations placed on me”; “I am not bothered about reviewing or checking things really closely” [recoded], “I always try to make my work as accurate and error-free as possible”, 7-point scale, Cronbach Alpha = .57). The correlation between the two scores was not significant, r = .09, p = .25.

Participants scoring high on the promotion but low on the prevention score were classified by median split (for this classification procedure see Van Dijk & Kluger, 2004) as being predominantly promotion focussed (n = 30). Those scoring high on prevention but low on promotion were categorized as being predominantly prevention focussed (n = 36). Participants whose scores were either over or under the median on both scores could not be associated with a predominant regulatory focus. They were pooled in a group with “indifferent” regulatory orientation (n = 82).

(b) Next, all participants read the same small essay on the necessity of paying taxes for the benefit of the society in general. Information was provided on the amount of taxes collected in the country in the past year and the amount of money invested into public goods (with exact numbers from the Austrian Ministry of Finances: Bundesministerium für Finanzen, 2005). Then participants either read positively or negatively framed information about the state's provision of public goods for the health system, education, public transport and traffic, public safety and civil protection, expenditures on arts and cultural activities, as well as social security. In the positive goal framing condition, information highlighted the benefits for everyone when the number of compliant taxpayers is high. In the negative goal framing condition, information highlighted the deficiencies for everyone when the number of compliant taxpayers is low. The full text of the scenarios is included in the appendix.

(c) Next, participants had to assume the role of a taxpayer who wanted to buy a new car and who earned € 4500 extra money. This extra money was subject to income tax. Participants had to decide whether to declare the extra income on their tax file and pay taxes or not. They were given the exact figures of how much social insurance and income tax they would have to pay. It was also mentioned in the scenario that fines would be imposed on taxpayers convicted of cheating; yet, the risk of being caught was described as very low. Intended tax compliance was measured by asking how likely it was that they would indicate their extra income on their tax file and pay taxes honestly (answers were marked on a 10 cm long line with endpoints labelled 0 = definitely sure not to declare the extra income, and 100 = definitely sure to declare the extra income. The graphic scale was used to reduce social desirability tendencies which are high in tax compliance measures).

(d) Finally, participants reported socio-demographic data including their age, gender, and employment status. After completing the questionnaire, participants were thanked and debriefed.

4.2 Results

A 2 × 3 - ANOVA with goal-framing (positive vs. negative) and dispositional regulatory focus (promotion vs. indifferent vs. prevention) as independent variables and tax compliance as dependent variable was performed. To account for the quasi-experimental nature of the study, demographic variables (gender, age, employment status) were included as covariates.

The results for the covariates show no effect of gender, F(1, 139) = 0.98, p = .32, η2 = .01, no effect of employment status, F(1, 139) = 1.10, p = .30, η2 = .01, but a significant effect of age, F(1, 139) = 5.28, p = .02, η2 = .04. This effect corresponds to a correlation of r = .14, p = .08, with older participants being more compliant.

The main effect of goal framing was not significant, F(1, 139) = .14, p = .71, η2 < .01. The main effect of regulatory focus was not significant, F(2, 139) = .26, p = .77, η2 < .01. The interaction between regulatory focus and goal framing was significant, F(2, 139) = 3.68, p = .03, η2 = .05. Table 1 shows raw means for the original data and the estimated marginal means after inclusion of covariates.

Table 1.

Tax compliance by dispositional regulatory focus and goal framing

| Dispositional Regulatory Focus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal Framing | Prevention | Indifferent | Promotion | |

| Descriptives without inclusion of covariates | ||||

| Prevention | M | 72.00 | 53.24 | 50.54 |

| SD | (25.33) | (37.71) | (41.23) | |

| n | 20 | 42 | 13 | |

| Promotion | M | 49.88 | 57.08 | 64.00 |

| SD | (36.99) | (37.06) | (33.77) | |

| n | 16 | 40 | 17 | |

|

| ||||

| Estimated marginal means after inclusion of covariates | ||||

| Prevention | M | 74.91 | 51.82 | 49.43 |

| SE | (8.01) | (5.52) | (9.89) | |

| 95% CI | 59.06 - 90.75 | 40.90 - 62.73 | 29.87 - 68.98 | |

| Promotion | M | 46.32 | 59.11 | 63.49 |

| SE | (8.97) | (5.66) | (8.72) | |

| 95% CI | 28.58 - 64.06 | 47.93 - 70.29 | 46.25 - 80.74 | |

Note: Tax compliance ranges from 0 (low) to 100 (high). Covariates were evaluated at Gender = .46 (1 = female), Employment status = .10 (1 = self-employed), Age = 33.93.

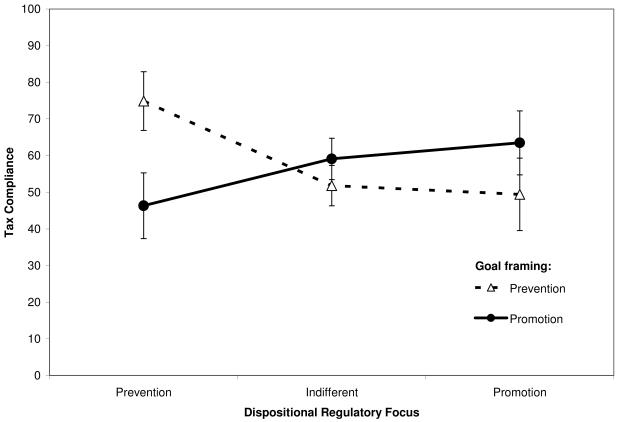

The pattern of the interaction is illustrated in Figure 1. Consistent with the hypothesis, tax compliance was higher under conditions of regulatory fit (M = 69.56, SE = 5.88) than under conditions of non-fit (M = 47.96, SE = 6.61), p = .02, with the group with indifferent regulatory focus being in-between (M = 55.33, SE = 3.91). The group with dispositional promotion focus indicated being more compliant after reading the promotion-framed text (M = 63.49) than the prevention-framed text (M = 49.43). Conversely, the group with dispositional prevention focus was more compliant after reading the prevention-framed text (M = 74.91) than the promotion-framed text (M = 46.32).

Figure 1. Tax compliance by dispositional regulatory focus and goal framing.

Note: Error bars indicate standard error of estimated marginal means. Covariates were evaluated at Gender = .46 (1 = female), Employment status = .10 (1 = self-employed), Age = 33.93.

Because Hasseldine and Hite (2003) reported an interaction effect between gender and goal framing on tax compliance, and because gender is to some degree correlated with dispositional regulatory focus (r = −.16, p = .06 for promotion focus with women scoring lower; r = .14, p = .08 for the prevention focus with women scoring higher), an additional ANOVA was conducted with gender and goal framing as independent variables, and age and employment status as covariates. In this analysis, neither the main effect of gender, F(1, 142) = .48, p = .49, η2 < .01, nor the interaction effect between gender and goal framing were significant, F(1, 142) = 1.10, p = .30, η2 = .01. Together with the findings from the main analyses where gender did not show a significant effect as a covariate, and the interaction effect between goal framing and regulatory focus was significant after controlling for gender, it is concluded that in the study at hand the different effectiveness of positive and negative framing of tax information can be attributed to regulatory focus rather than gender differences.

4.3 Discussion

Depending on taxpayers' dispositional regulatory focus, positively as well as negatively framed information can have favourable effects on willingness to comply. Compliance seems to increase when reading information framed according to recipients' regulatory fit, that is, when regulatory focus and information focus are congruent. Taxpayers with a promotion focus provided with information about the benefits of tax budgets being sufficient, and taxpayers with a prevention focus provided with information about the dangers of tax budgets being insufficient are more willing to comply than when provided with information inconsistent with their regulatory focus.

Study 1 has some limitations, however. First, it used a quasi-experimental design where regulatory focus was measured but not manipulated. Second, wording used in the scenarios was not perfectly parallel, and might have been subject to interpretations in line with personal political preferences. Third, tax compliance was measured only by a single item. Therefore, in study 2, regulatory focus was experimentally induced, the scenarios were constructed parallel, control items regarding political stance towards taxes were included, and tax compliance was measured more fine-grained.

5. Study 2: Situational regulatory focus, goal framing and tax compliance

5.1 Method

Participants

Questionnaires were distributed to 119 participants; two had to be excluded due to missing data. The remaining sample consisted of 76 women and 41 men. Mean age was 26.74 years (SD = 5.72, Md = 25). The sample consisted of 24 self-employed professionals, 70 employees, and 23 non-employed persons. Data was collected at the University of Vienna and in evening classes at a college of higher education in Vienna, Austria.

Design

A 2 × 2 between-subjects design with situational regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) as independent variables and tax compliance as dependent variable was used. Participants were randomly assigned to conditions.

Material and procedure

Participants completed a questionnaire including (a) manipulation of situational regulatory focus, (b) manipulation of goal framing through an information campaign about public income and spending and provision of public goods, (c) a scenario measuring tax compliance and (d) questions on socio-demographic data. It took about 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

(a) Regulatory focus was experimentally induced through a regulatory focus priming task modelled after Freitas and Higgins (2002, Study 2). In the promotion focus condition, participants read a short text about the relevance of wishes in everyday life, and about the usefulness of concrete ideas about how to fulfil such wishes. An example was given by the wish for being healthy to old age and the strategies of eating fruit and vegetables, being outdoors, or learning relaxation techniques. Participants had to write down one wish that was important to them personally. They were asked to think of the joy they would experience should their wish come true, and to think of what they could do to successfully realize their wish. Participants then had to write down up to 5 realization strategies. In the prevention focus condition, participants read a short text about the relevance of obligations in everyday life, and about the usefulness of concrete ideas about how to fulfil such obligations. An example was given by the obligation to control weight and the strategies of avoiding rich food, to resist temptations or to follow a dieting plan. Participants had to write down one obligation that was important to them personally. They then were asked to think of the negative consequences they would experience when they would not follow that obligation, and to think of what they could do to avoid such consequences. Participants then had to write down up to 5 avoidance strategies.

(b) Goal framing was induced by having participants reading a small essay on the necessity of paying taxes for the benefit of the society in general. Information was provided on the amount of taxes collected and the amount of money invested into public goods (exact information taken from Bundesministerium für Finanzen, 2005). In the positive goal framing condition, potential benefits of sufficient provision of taxes by citizens were described. For example, the health care system could be maintained on the most recent level of expertise, so that in the case of illness the newest methods would be used. In the negative goal framing condition, potential dangers of insufficient provision of taxes by citizens were described. For example, the health care system could not be maintained, and in case of illness outdated methods would be used. The full text is included in the appendix.

(c) Tax compliance was measured by a scenario. Participants were asked to imagine themselves being self-employed architects, planning to buy a new car, and needing more money for this purchase. They would work on their income tax declaration and consider different opportunities to reduce tax payments. Four opportunities were described: incorrectly deducing airplane tickets paid for by business partners, incorrectly deducing private restaurant bills by claiming them to be business meetings, not declaring additional income earned on projects, and not declaring a honorarium earned on giving a lecture. Participants stated the likelihood to which they, given the situation described in the scenario, would use each of the four opportunities (5-point scale, 1 = “under no circumstances” to 5 = “definitely certain”). These four items showed satisfactory reliability (Cronbach Alpha= .74). They were recoded so that high values indicate tax compliance and averaged to form a scale.

(d) Finally, participants reported socio-demographic data, including age, gender, and employment status.

5.2 Results

A two-way ANOVA showed a nonsignificant main effect of regulatory focus, F(1, 113) = 1.47, p = .23, η2 = .01, and a nonsignificant main effect of goal framing, F(1, 113) = .03, p = .86, η2 < .01. The hypothesized interaction effect between regulatory focus and goal framing was significant, F(1, 113) = 4.50, p = .04, η2 = .04.

For a direct comparison with study 1, the same demographic variables were included as covariates. The results for the covariates show no effect of gender, F(1, 110) = 1.19, p = .28, η2 = .01, no effect of being self-employed, F(1, 110) = 0.92, p = .34, η2 = .01, and no significant effect of age, F(1, 110) = 0.76, p = .39, η2 = .01. Accordingly, the effects of the experimental variables remained unchanged. The main effect of regulatory focus, F(1, 110) = 1.37, p = .25, η2 = .01 and the main effect of goal framing, F(1, 110) < .01, p = .99, η2 < .01, were not significant, the hypothesized interaction effect between regulatory focus and goal framing was significant, F(1, 110) = 4.93, p = .03, η2 = .04. Raw means and estimated marginal means after including the covariates are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Tax compliance by situational regulatory focus and goal framing

| Situational Regulatory Focus |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal Framing | Prevention | Promotion | |

| Descriptives without inclusion of covariates | |||

| Prevention | M | 3.36 | 3.19 |

| SD | (0.85) | (1.03) | |

| n | 33 | 24 | |

| Promotion | M | 2.93 | 3.55 |

| SD | (1.15) | (0.97) | |

| n | 29 | 31 | |

|

| |||

| Estimated marginal means after inclusion of covariates | |||

| Prevention | M | 3.35 | 3.16 |

| SE | (0.17) | (0.20) | |

| 95% CI | 3.01 - 3.70 | 2.75 - 3.56 | |

| Promotion | M | 2.94 | 3.57 |

| SE | (0.19) | (0.18) | |

| 95% CI | 2.57 - 3.30 | 3.21 - 3.92 | |

Note: Tax compliance ranges from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Covariates were evaluated at Gender = .65 (1 = female), Employment status = .21 (1 = self-employed), Age = 36.75.

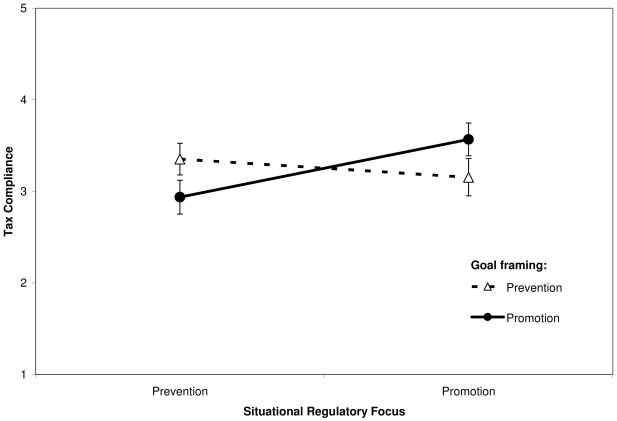

The pattern of the interaction is illustrated in Figure 2. Consistent with the hypothesis, tax compliance was significantly higher under conditions of regulatory fit (M = 3.46, SE = .12) than under conditions of non-fit (M = 3.04, SE = .14), p = .03. The group with the induced situational promotion focus was more compliant after reading the promotion-framed text (M = 3.57) than the prevention-framed text (M = 3.16). Conversely, the group with the induced situational prevention focus was more compliant after reading the prevention-framed text (M = 3.35) than the promotion-framed text (M = 2.94).

Figure 2. Tax compliance by situational regulatory focus and goal framing.

Note: Error bars indicate standard error of estimated marginal means. Covariates were evaluated at Gender = .65 (1 = female), Employment status = .21 (1 = self-employed), Age = 36.75.

Neither age nor gender nor employment status showed an influence on tax compliance. Robustness checks were performed by including additional items as covariates. Neither involvement with the tax topic (e.g., “I frequently discuss details on tax issues with friends or family”, F(1, 108) = 0.94, p = .33, η2 = .01) nor political stance on taxes (e.g., “I do not think it sensible to use tax revenues for social welfare”, F(1, 109) = .06, p = .81, η2 < .01) did show an influence.

6. Conclusions

Tax payments can be conceived as contributions to public goods. In public goods studies, willingness to cooperate has been found to depend on various variables, e.g., communication between actors, group identity, payoffs, or identifiability of contributions (Dawes, 1980; Dawes & Messick, 2000; Kollock, 1998). We suggest that in a tax setting, a relevant factor determining willingness to cooperate is citizens' knowledge about the use of contributions and the provision of public goods. If the Ministry of Finance effectively communicates the use of tax money for providing public goods, then taxpayers are expected to be more compliant as compared to taxpayers with poor knowledge. Communication about the necessity of paying taxes for governmental investment in public goods can, however, focus on the shortcomings in case of non-compliance or the advantages of compliance. The question is whether pointing at citizens' losses in case of tax non-compliance is more effective than stressing their gains in case of cooperation. We argue that the effectiveness of positively and negatively framed information about the use of tax payments for public goods and the consequences of tax behaviour depends on the recipient's regulatory focus. Neither framing can be considered as generally more effective. In two studies, interaction effects between regulatory focus and goal-framing on tax compliance were found. For recipients under promotion focus, information highlighting the potential gains increased tax compliance; for recipients under prevention focus, information highlighting the potential losses increased tax compliance. The effect of regulatory fit held for both dispositional and situational regulatory focus.

Results are in line with research in marketing contexts (e.g., Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004; Florack & Scarabis, 2006) and health promotion contexts (e.g., Spiegel, Grant-Pillow, & Higgins, 2004). The current studies indicate that also for tax contexts, regulatory fit is an important factor to consider when designing information campaigns. Study 2 has shown that the regulatory fit effect also pertains for situational regulatory focus. As far as radio or TV advertisement is concerned, regulatory focus may be induced either by the context in which the commercials are transmitted or even by a commercial itself. Regulatory focus could be induced through a TV-ad by using images or scenes which activate either promotion or prevention focus. The focus activated by the spot should then be coherent with the goal-framing of the advertising slogan. Further, different radio or TV-programmes could induce either promotion or prevention focus. A game show, for example, may activate a promotion focus, whereas a documentary about the protection of nature may induce a prevention focus. Commercials transmitted during or after specific programmes could be more effective if their message fits the focus induced by the programmes.

Considering regulatory fit for tax compliance messages could also contribute to more voluntary tax compliance as opposed to enforced tax compliance. The “slippery slope” framework proposed by Kirchler and colleagues (Kirchler, 2007; Kirchler, Hölzl, & Wahl, in press) suggests that authorities should aim at increasing trust of taxpayers, which in turn would result in voluntary compliance. A message about the use of taxes that is both truthful and framed in the right way to be processed more easily due to its congruence with recipients' regulatory focus is likely to increase trust, and could reduce the perceived difference between individual and collective interests.

Acknowledgements

These studies were partly funded by the Austrian Central Bank (OeNB), project 11114, and partly by the Austrian Science Funds (FWF), P19925-G11. The authors thank Franziska Hämmerle for her support.

Appendix

Goal framing manipulation, study 1

| Positive goal framing | Negative goal framing |

|---|---|

| Citizens' tax payments are the most important source of the state's revenue. In 2005, Austria had total revenues based on taxes, dues and fees of € 58.97 billion. Thereof, € 31.8 billion were so-called transfer payments. The federation did not use them for fulfilling its own tasks but redistributed them in many ways in the form of public goods and services to the citizens. | |

| Paying tax is making the state prosperous. If citizens honestly report to the tax office, the state is able to use the tax budget for financing and improving the welfare system and to provide its citizens with modern health care. Furthermore, if tax payments are sufficient, the state can extend infrastructure such as the road and railway system. The legal system can also be brought to a high and modern level and the safety of the state can be guaranteed. With public money, the educational system can be of high quality and offer a broad learning opportunity at schools and universities. As for arts and culture, a broad range of events can be subsidised. All citizens profit from public goods and services if taxpayers pay tax honestly. |

Without paying tax no state can prosper. If citizens do not report to the tax office honestly, tax revenue is low and the state is no longer able to care about social justice and equal medical treatment for all citizens. Furthermore, if tax payments are insufficient, the state has to cut down on infrastructure; the continuous maintenance of the road and railway system can no longer be guaranteed. Extensive economies could impend in the field of security and the legal system. If public money is not enough, the educational system could deteriorate and the standard of schools and universities could decrease. As for arts and culture, a shortage of subsidies strongly curtails the cultural offer. Citizens profit less from public goods and services if a major part of the taxpayers evade. |

Goal framing manipulation, study 2

| Positive goal framing | Negative goal framing |

|---|---|

| Citizens' tax payments are the most important source of the state's revenue. In 2005, Austria had total revenues based on taxes, dues and fees of € 58.97 billion. Thereof, € 31.8 billion were so-called transfer payments. The federation did not use them for fulfilling its own tasks but redistributed them in many ways in the form of public goods and services to the citizens. If taxes are paid honestly, the state has sufficient financial resources; however, if most citizens evade taxes, these funds are lacking. | |

| Sufficient tax revenues allow development of the welfare system. Citizens in crisis without their own fault can receive support. The health care system can be maintained state- of-the-art. In case of sickness, the newest treatment methods are used. As a further consequence of sufficient tax revenues, the state is able to expand infrastructure, e.g., roads and railways. The infrastructure improves. The educational system in schools and universities can be funded with sufficient tax revenues, with positive consequences for the level and the quality of education and advanced training. Research and science can be further funded through tax revenues. This brings the chance of increasing national competitiveness. The high level of the legal system can be maintained and developed further. Independent jurisdiction and security can be ensured. Sufficient tax revenues allow promotion of cultural affairs and the diversity of cultural offers. If tax payers declare their income honestly, the chances of improvements in these public goods can be maintained. |

A lack of tax revenues may lead to a cutback on the welfare system. Citizens in crisis without their own fault can receive no support. The health care system can not be maintained state-of-the-art. In case of sickness, outdated treatment methods are used. As a further consequence of lacking tax revenues the state is unable to maintain infrastructure, e.g., roads and railways. The infrastructure deteriorates. The educational system in schools and universities can not be funded if tax revenues are insufficient, with negative consequences for the level and the quality of education and advanced training. Research and science can not be funded through tax revenues any longer. This brings the risk of diminishing national competitiveness. The high level of the legal system can not be maintained and is threatened by decline. Independent jurisdiction and security can not be ensured any longer. Insufficient tax revenues restrict promotion of cultural affairs and the diversity of cultural offers. If tax payers declare their income honestly, the threat of restrictions in these public goods can be avoided. |

Footnotes

PsychINFO classification: 2360 Motivation & Emotion 2750 Mass Media Communications 3040 Social Perception & Cognition

JEL classification: H26 Tax Evasion H41 - Public Goods

References

- Aaker JL, Lee AY. “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: The role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research. 2001;28(1):33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Allingham MG, Sandmo A. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics. 1972;1(3):323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J, Erard B, Feinstein J. Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36(2):818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Block LG, Keller PA. When to accentuate the negative: The effects of perceived efficacy and message framing on intentions to perform a health-related behavior. Journal of Marketing Research. 1995;32(2):192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite V. Who's not paying their fair share: Public perception of the Australian Tax System. Australian Journal of Social Issues. 2003;38(3):323–348. [Google Scholar]

- Brendl CM, Higgins ET. Principles of judging valence: What makes events positive or negative? In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 28. Academic Press; New York: 1996. pp. 95–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Finanzen Budget 2005. 2005. Retrieved January 15, 2007, from http://www.bmf.gv.at/Budget/Budget2005/budget05_zahlen_hintergruende_zusammenhaenge.pdf.

- Camacho CJ, Higgins ET, Luger L. Moral value transfer from regulatory fit: What feels right is right and what feels wrong is wrong. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(3):498–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “Feeling Right.”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(3):388–404. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernev A. Goal-attribute compatibility in consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2004;14(1-2):141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes RM. Social dilemmas. Annual Review of Psychology. 1980;31:169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes RM, Messick DM. Social dilemmas. International Journal of Psychology. 2000;35(2):111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler JB, Bedell BT, Salovey P, Pronin E, Rothman AJ. Message framing and sunscreen use: Gain-framed messages motivate beach-goers. Health Psychology. 1999;18(2):189–196. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger R, Frey BS. Democratic governance for a globalized world. Kyklos. 2002;55(2):265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Fellner B, Holler M, Kirchler E, Schabmann A. Regulatory Focus Scale (RFS): Development of a scale to record dispositional regulatory focus. Swiss Journal of Psychology. 2007;66(2):109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fellner B, Kirchler E, Holler M. Zur Effizienz von Feedback bei präventionsund promotionsorientierten Mitarbeitern. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft. 2004;54(4):120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Florack A, Scarabis M. How advertising claims affect brand preferences and category-brand associations: The role of regulatory fit. Psychology and Marketing. 2006;23(9):741–755. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas AL, Higgins ET. Enjoying goal-directed action: The role of regulatory fit. Psychological Science. 2002;13(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzach Y, Karsahi N. Message framing and buying behavior: A field experiment. Journal of Business Research. 1995;32(1):11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gierl H. Der optimale Einsatz von Goal-Frames in der Anzeigenwerbung. Transfer – Werbeforschung & Praxis. 2005;50(3):4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hasseldine J, Hite PA. Framing, gender and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2003;24(4):517–533. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist. 1997;52(12):1280–1300. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 30. Academic Press; New York: 1998. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist. 2000;55(11):1217–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler M, Dobnig S, Kirchler E. Regulatorischer Fokus und Motivationsstärke von Warnhinweisen auf Zigarettenpackungen. Wirtschaftspsychologie. 2007;9(1):97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Holler M, Fellner B, Kirchler E. Selbstregulation, Regulationsfokus und Arbeitsmotivation: Überblick über den Stand der Forschung und praktische Konsequenzen. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft. 2005;55(2):145–168. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Alley C. Tax compliance, self-assessment and tax adminstration. Journal of Finance and Management in Public Services. 2002;2(2):27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. Differential representations of taxes: Analysis of free associations and judgments of five employment groups. Journal of Socio Economics. 1998;27(1):117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. The economic psychology of tax behaviour. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Hölzl E, Wahl I. Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: The “slippery slope” framework. Journal of Economic Psychology. in press. [doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2007.05.004] [Google Scholar]

- Kollock P. Social dilemmas: The anatomy of cooperation. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:183–214. [Google Scholar]

- Mann T, Sherman D, Updegraff J. Dispositional motivations and message framing: A test of the congruency hypothesis in college students. Health Psychology. 2004;23(3):330–334. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw K, Scholz J. Norms, social commitment and citizens' adaptation to new laws. In: van Koppen PJ, Hessing DJ, van de Heuvel C, editors. Lawyers on Psychology and Psychologists on Law. Swets & Zeitlinger; Berwyn, PA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz BE, Chaiken S. The effect of message framing on breast self-examination attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(3):500–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommerehne WW, Weck-Hannemann H. Steuerhinterziehung: Einige romantische, realistische und nicht zuletzt empirische Befunde. Zeitschrift fur Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften. 1992;112(3):433–466. [Google Scholar]

- Reber R, Winkielman P, Schwarz N. Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science. 1998;9(1):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ML. An experimental approach to changing taxpayers' attitudes towards fairness and compliance via television. Journal of the American Taxation Association. 1994;16(1):67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P, Antone C, Keough K, Martin CD. The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1993;29(5):408–433. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel S, Grant-Pillow H, Higgins ET. How regulatory fit enhances motivational strength during goal pursuit. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;34(1):39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N, Wenzel M. The effects of different letter styles on reported rental income and rental deductions: An experimental approach. Centre for Tax System Integrity, Australian National University; 2001. Working Paper, No 11, July. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk D, Kluger A-N. Feedback sign effect on motivation: Is it moderated by regulatory focus? Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2004;53(1):113–135. [Google Scholar]

- van Lange PAM, Liebrand WBG, Messick DM, Wilke HAM. Social dilemmas: The state of the art. In: Liebrand WBG, Messick DM, Wilke HAM, editors. Social dilemmas. Theoretical issues and research findings. Pergamon Press; Oxford, UK: 1992. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Werth L, Mayer J, Mussweiler T. Der Einfluss des regulatorischen Fokus auf integrative Verhandlungen. Zeitschrift fur Sozialpsychologie. 2006;37(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley JJ, Oshikawa S. The relationship between anxiety and positive and negative advertising appeals. Journal of Marketing Research. 1970;7(1):85–89. [Google Scholar]

- White RA, Curatola AP, Samson WD. A behavioral study investigating the effect of increasing tax knowledge and fiscal policy awareness on individual perceptions of federal income tax fairness. Advances in Taxation. 1990;3:165–185. [Google Scholar]