Abstract

Background

Happiness is believed to evolve from the comparison of current circumstances relative to past achievement. However, gerontological literature on happiness in extreme old age has been limited.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine how perceptions of health, social provisions, and economics link past satisfaction with life to current feelings of happiness among persons living to 100 years of age and beyond.

Methods

A total of 158 centenarians from the Georgia Centenarian Study were included to conduct the investigation. Items reflecting congruence and happiness from the Life Satisfaction Index were used to evaluate a model of happiness. Pathways between congruence, perceived economic security, subjective health, perceived social provisions, and happiness were analyzed using structural equation modeling.

Results

Congruence emerged as a key predictor of happiness. Furthermore, congruence predicted perceived economic security and subjective health, whereas perceived economic security had a strong influence on subjective health status.

Conclusion

It appears that past satisfaction with life influences how centenarians frame subjective evaluations of health status and economic security. Furthermore, past satisfaction with life is directly associated with present happiness. This presents implications relative to understanding how perception of resources may enhance quality of life among persons who live exceptionally long lives.

Key Words: Centenarians, Happiness, Economic security, Social provisions

Predicting Happiness among Centenarians

Centenarians need basic resources (e.g. health, social provisions, economic security) to feel happy [1]. Some investigators have asserted that life satisfaction declines after age 65 [2], whereas others have argued that satisfaction with life remains stable [3]. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that pleasant and negative emotions in late adulthood emerge from competing perceptions of available resources [4]. In effect, happiness is believed to be ‘anchored’ to a comparison of current circumstances relative to past life experiences [5]. However, the pathways by which happiness is derived in extreme later life remain unclear. We propose that perceptions of health, social, and economic resources help determine whether appraisal of the past improves or diminishes feelings of happiness in extreme old age.

Theoretical Conceptualization

Late adulthood has been theorized as a stage of psychosocial development during which heightened awareness of mortality precipitates a need to find happiness [6]. The review or appraisal of life experiences has been hypothesized to improve or diminish contentment with life in the aftermath of physical, social, or financial loss in late and very late life [6]. Relative to life course theory, this process has been referred to as the ‘accentuation principle’ [7]. The primary assumption of this theoretical tenet is that appraisal of the past influences current perception of resources, which in turn contributes to current psychological disposition (e.g. happiness). In effect, resources are believed to represent a mechanism by which perceptions of the past influence present happiness.

Centenarians and Resources

Old-old adults often recall positive distal memories to improve feelings of life satisfaction [8]. However, this can conceal deleterious health conditions and create a false sense of happiness [8]. This may explain why old-old adults hindered by health problems remain less satisfied with life [9], or why those with greater social resources feel happier to the extent they are healthy [9]. In addition, it is possible that emergent health problems exacerbate financial hardship. Centenarians who achieved socioeconomic affluence earlier in life often report they cannot fulfill economic aspirations or obligations [1]. This belief may be due to greater health impairment which erodes positive perceptions of past and present life conditions [10]. Furthermore, it can be argued that some exceptionally old persons may perceive they have an economically better or worse situation compared to peers who have encountered similar or recent health problems. Therefore, financial security may directly impact positive perceptions about life [11]. Together, satisfaction with life in the past, health status, social provisions, and economic security represent key contributing factors of happiness in extreme longevity.

Present Study

We sought to determine how resources influence the link between past satisfaction with life and current happiness. We hypothesized that past satisfaction with life, social provisions, and economic security would have a direct influence on perceived health, as well as an indirect influence on happiness through perceived health.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study originated from the Georgia Centenarian Study. All participants were screened using the Mini-Mental Status Examination [12]. Lower education among the older cohort and ethnicity may yield lower cutoff scores [13]. Therefore, a score less than 17 indicated severe cognitive impairment, whereas a score of 17 and higher reflected mild or no cognitive impairment. Scores on the cognitive screen ranged from 17 to 30 (mean: 23.39, SD: 3.94). This resulted in a final sample of 158 centenarians (mean age: 99.82 years, SD: 1.71) which included 124 women and 34 men. Eighty-five percent of the participants reported their race as White/Caucasian. Another 15% identified their race as Black/African-American. Education level was also considered: 19.1% of participants indicated they had received 8 or less years of formal education, 20.6% had completed some high school, 22.1% had finished high school, 16.9% reported they had achieved some high school or postsecondary vocational training, and 21.3% reported they had earned a college degree or greater.

Measures

Happiness. Three mood-tone items from the Life Satisfaction Index [14] were used to assess happiness. Participants were asked to indicate whether they disagreed (–1), were uncertain (0), or agreed (1) with the following statements: ‘I am just as happy as when I was younger’, ‘My life could not be happier than it is now’, and ‘These are the best years of my life’. A high rating of happiness represented greater feelings of happiness. Reliability for this scale was 0.62.

Health. Health was evaluated using two subjective health items from the Older Americans Resources and Services scale (OARS) [15]. The first question was: ‘How would you rate your overall health at the present time?’ Participants were asked to respond with the following ratings: 0 = poor, 1 = fair, 2 = good, or 4 = excellent. The second question was: ‘How much do health problems stand in the way of doing the things you want to do?’ Participants were asked to respond: 0 = a great deal, 1 = a little/some, or 3 = not at all. A high rating of perceived health reflected a better perception of health. The α reliability for the subjective health scale was 0.57.

Social Provisions. Social provisions were evaluated using a 12-item short form of the Social Provisions Scale [16]. Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = slightly disagree, 3 = slightly agree, 4 = strongly agree) to the following items: ‘There is no one I can turn to for guidance’, ‘If something went wrong, no one would come to my assistance’, and ‘There is no one who shares my interests and concerns’. All items were recoded so that a high score would reflect greater social support. A high rating of social provisions indicated high social resources. Cronbach's α for the full scale was 0.61.

Economic Security. Economic security was assessed using five items from OARS [15]. Participants responded to three dichotomous items (e.g. 0 = no, 1 = yes). Questions included: (1) ‘Are your assets and financial resources sufficient to meet emergencies?’, (2) ‘Do you usually have enough to buy those little “extras”, that is those small luxuries?’, and (3) ‘At the present time, do you feel you will have enough for your needs in the future?’ Participants were asked two additional questions: (1) ‘Are your expenses so heavy you 1 = cannot meet the payments, 2 = barely meet the payments, or 3 = payments are no problem?’ and (2) ‘Does the amount of money you have take care of your needs 1 = poorly, 2 = fairly well, or 3 = very well?’ A high rating of perceived economic security represented greater feelings of economic security. Reliability for this scale was α = 0.69.

Congruence. Congruence items from the Life Satisfaction Index [14] were used to assess past life satisfaction. Participants were asked to indicate whether they disagreed (–1), were uncertain (0), or agreed (1) with the following statements: (1) ‘As I look back on my life, I am fairly well satisfied’, (2) ‘I would not change my past life even if I could’, and (3) ‘I've gotten pretty much what I expected out of life’. A high rating of congruence was indicative of greater satisfaction with life in the past. Cronbach's α for this scale was 0.53.

Analysis

Structural equation modeling (LISREL 8.71 [17]) was used to assess a structural model with direct and indirect path relationships between congruence, perceived social provisions, perceived economic security, perceived health, and happiness. A χ2 difference test was used to compare model fit to an alternative model in which the direct path between congruence and happiness had been omitted. Goodness-of-fit and explained variance among variables was also evaluated.

Results

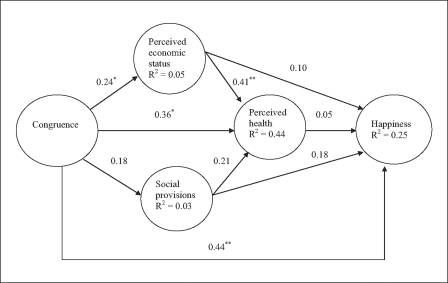

Figure 1 depicts the results of our analysis. Congruence was a predictor of perceived economic status (β = 0.24, p < 0.05) and perceived health (β = 0.36, p < 0.05). Congruence also had a strong direct association with current happiness (β = 0.44, p < 0.01). Greater satisfaction with the past was directly associated with positive perceptions of economic security, health, and happiness.

Fig. 1.

Model of happiness in extreme late adulthood. ∗ p < 0.05; ∗ ∗ p < 0.01.

In addition, perceived economic status (β = 0.41, p < 0.01) was a key predictor of subjective health status. Greater economic status was associated with better subjective health. However, economic security, social provisions, and subjective health were not significant predictors of happiness.

The happiness model had a satisfactory fit [χ2 (d.f. = 95) = 143.18, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06]. Furthermore, congruence, economic security, and social provisions explained 44% of the variance in subjective health status. Congruence, economic security, subjective health status, and social provisions explained 25% of the variance in happiness.

An alternative model in which the path between congruence and happiness was omitted was constructed for comparison. The fit of this model was χ2 (d.f. = 96) = 150.80, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06. χ2 difference testing was not indicative of a significant difference. Therefore, it is statistically better to leave the direct path from congruence to happiness within the model.

Discussion

Results from this investigation reconfirmed our previous findings that satisfaction with life in the past has a direct association with current feelings of happiness [10]. However, subjective social provisions, perceived economic security, and subjective health status did not emerge as significant predictors of happiness. Furthermore, there was no indication that resources act as mechanisms of happiness. Therefore, the original hypothesis was not confirmed by the results.

It appears that positive appraisal of the past is an important indicator of feeling happy in extreme old age. Erikson [6] posited that older adults who appraise or review life as a success rather than a failure express greater contentment toward life. For example, investigators have noted that job-training earlier in life has a significant negative influence on happiness among centenarians [1]. Perhaps, exceptionally old adults maintain a belief or attitude that they no longer have the physical stamina or functional capacity to remain productive. However, many adapt by recalling past career accomplishments or achievements to reaffirm contentment in the present [8]. This may explain why centenarians feel satisfied with the past and maintain positive perceptions about their current economic situation or health status.

Economic security also improves subjective health perception. Centenarians generally feel less burdened by financial challenges [18]. Tornstam [19] theorized that this represents a gerotranscendent view of wealth, in which economic security is defined as ‘having enough for the necessities of life, but not more’ (p. 74). It is important to note that many centenarians have escaped or delayed impairment and disease [20]. It is possible that exceptionally old persons maintain positive health perceptions due to limited exposure to deleterious health problems which would otherwise demand greater economic resources.

Several limitations should be noted. First, longitudinal data were not available for analysis. Therefore, a cross-sectional framework was used. Cross-sectional analyses are typically used to test pathway associations. This restricts casual inferences in modeling change across time. Caution is advised in the interpretation of results. Second, cognitive screening procedures can result in samples with greater cognitive and health functioning. Participants were not screened for additional neurological or psychiatric illnesses. Therefore, results may not generalize across all centenarian populations. Third, congruence as a predictor and happiness as an outcome were assessed using the same measurement scale. This may have increased the likelihood of construct overlap. Results may reflect associated dimensions of life satisfaction rather than two unique and separate factors. Fourth, a quantitative approach was used. This may have presented a simplistic approach to a more complex phenomenon. Qualitative assessment of life events and current resources might have improved interpretive understanding of happiness.

Despite these limitations, this study has implications toward improving quality of life. Gerontologists, geriatric psychiatrists, geriatric physicians, and geriatric social workers should use the results from this study to implement programs, including reminiscence therapy and structured life review sessions to foster feelings of happiness among very old populations. Future research with centenarians should identify distal life experiences which influence happiness, explore how life stages shape happiness, and devise longitudinal growth curve models of happiness.

Acknowledgements

The Georgia Centenarian Study (Leonard W. Poon, PI) is funded by 1PO1-AG17553 from the National Institute on Aging, a collaboration among The University of Georgia, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, Boston University, University of Kentucky, Emory University, Duke University, Wayne State University, Iowa State University, Temple University, and University of Michigan. Authors acknowledge the valuable recruitment and data acquisition effort from M. Burgess, K. Grier, E. Jackson, E. McCarthy, K. Shaw, L. Strong and S. Reynolds, data acquisition team manager; S. Anderson, E. Cassidy, M. Janke, and J. Savla, data management; M. Poon for project fiscal management.

Footnotes

Additional authors include S.M. Jazwinski, R.C. Green, M. Gearing, W.R. Markesbery, J.L. Woodard, M.A. Johnson, J.S. Tenover, I.C. Siegler, W.L. Rodgers, D.B. Hausman, C. Rott, A. Davey, and J. Arnold.

References

- 1.Jopp D, Rott C. Adaptation in very old age: exploring the role of resources, beliefs, and attitudes for centenarians' happiness. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:266–280. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mroczek DK, Spiro A., III Change in life satisfaction during adulthood: findings from the Veterans Affairs normative aging study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:189–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas RE. Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: does happiness change after major life events? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Hippel W. Aging and social satisfaction: offsetting positive and negative effects. Psychol Aging. 2008;23:435–439. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen K, Shmotkin D. Emotional ratings of anchor periods in life and their relation to subjective well-being among holocaust survivors. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:495–506. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erikson EH. The Life Cycle Completed. New York: W.W. Norton Co.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elder GH., Jr . Human lives in changing societies: life course and developmental insights. In: Cairns RB, Elder GH Jr, Costello EJ, editors. Developmental Science. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aberg AC, Sidenvall B, Hepworth M, O'Reilly K, Lithell H. On loss of activity and independence, adaptation improves life satisfaction in old age – a qualitative study of patients' perceptions. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1111–1125. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillerås PK, Jorm AF, Herlitz A, Winblad B. Life satisfaction among the very old: a survey on a cognitively intact sample aged 90 years or above. Int J Aging Human Dev. 2001;52:71–90. doi: 10.2190/B8NC-D9MQ-KJE8-UUG9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishop AJ, Martin P, Poon L. Happiness and congruence in older adulthood: structural model of life satisfaction. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:445–453. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holden K, Hatcher C. Econcomic status of the aged. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. ed 6. Boston: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental Status Examination: A comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neugarten BL, Havighurst RJ, Tobin SS. The measurement of life satisfaction. J Gerontol. 1961;16:134–143. doi: 10.1093/geronj/16.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults: the Duke Older Americans Resources and Services procedures. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Adv Pers Relat. 1987;1:37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8.5 User's Reference Guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin P, Poon LW, Kim E, Johnson MA. Social and psychological resources in the oldest old. Exp Aging Res. 1996;22:121–139. doi: 10.1080/03610739608254002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: A developmental Theory of Positive Aging. New York: Springer Publishing Co.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evert J, Lawler E, Bogan H, Perls T. Morbidity profiles of centenarians: survivors, delayers, and escapers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:232–237. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]