Abstract

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the most frequently encountered pathogens in humans but its differentiation from closely related but less pathogenic streptococci remains a challenge.

Methods

This report describes a newly-developed PCR assay (Spne-PCR), amplifying a 217 bp product of the 16S rRNA gene of S. pneumoniae, and its performance compared to other genotypic and phenotypic tests.

Results

The new PCR assay designed in this study, proved to be specific at 57°C for S. pneumoniae, not amplifying S. pseudopneumoniae or any other streptococcal strain or any strains from other upper airway pathogenic species. PCR assays (psaA, LytA, ply, spn9802-PCR) were previously described for the specific amplification of S. pneumoniae, but psaA-PCR was the only one found not to cross-react with S. pseudopneumoniae.

Conclusion

Spne-PCR, developed for this study, and psaA-PCR were the only two assays which did not mis-identify S. pseudopneumoniae as S. pneumoniae. Four other PCR assays and the AccuProbe assay were unable to distinguish between these species.

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the most pathogenic bacteria involved in human disease [1], causing bronchitis, pneumonia, as well as life-threatening meningitis and bloodstream infections [2]. Culture-based methods are usually applied to detect S. pneumoniae from patient samples and to differentiate it from other less pathogenic viridans streptococci, frequently encountered in respiratory samples. Differentiation is also important with regard to resistance testing, since different antibiotic susceptibility breakpoints are applied for S. pneumoniae with regard to other viridans species [3]. Culture-based identification methods usually rely on optochin susceptibility, agglutination and bile-solubility, sometimes confirmed by specific probes (Accuprobe™, Genprobe) [4].

However, straightforward phenotypic identification of pneumococci is hampered by the occurrence of optochin resistant S. pneumoniae variants [5-8] and. In addition, closely related S. pseudopneumoniae is difficult to distinguish from S. pneumoniae and is e.g. positive with AccuProbe as well [4].

It is of clinical relevance to rapidly and specifically detect S. pneumoniae. Therefore several PCR assays have been developed over the past decades [9-14].

This study compared the specificity of four published S. pneumoniae PCR assays to that of a new approach, based on the 16S rRNA gene. One novelty of this approach regards the in-silico design of specific primers using published Streptococcus sequences, filtered for quality and annotation-reliability by profile-based methods (SmartGene, Zug, Switzerland). The approach used by this program relies on a systematic analysis of all published 16S rRNA gene sequences for all streptococci (and closely related organisms), using sequence profiles to eliminate obviously incomplete or erroneous submissions, which could induce wrong alignments.

Sequences with a likely incorrect annotation (shown by low match scores to other sequences of the same species), with unexpected deletions/insertions, or with non useful annotations (e.g. "uncultured") were excluded, since they could induce misleading alignments. Thus, the most representative 16S rRNA sequences were determined for each species. Such a database of representative sequences was used to align closely related streptococcal species to identify specific positions in the 16S rRNA gene for the purpose of species-specific identification. Once these positions were identified, general searches on relevant published sequences of S. pneumoniae and closely related relatives confirmed the consistency of the sequence pattern found. This method helped to detect discriminative species-specific sequence patterns for S. pneumoniae and S. pseudopneumoniae, thus saving time and effort through reduction of non-specific results in wet-lab testing.

Methods

Bacterial strains

A total of 73 streptococcal strains were analyzed in this study, as listed in Table 1, i.e. 8 reference strains of Streptococcus mitis [11] and seven reference strains of S. oralis [11], including three reference strains and the type strain; 19 strains of S. pneumoniae, including two reference strains and the type strain and including 10 optochin resistant strains, for which it was concluded in a previous study [11] that these were genuine S. pneumoniae. In addition, a total of 30 optochin resistant pneumococcus-like streptococci already well-characterized in an earlier study [11], were also included. Finally, the type strain, two reference strains and one clinical strain of S. pseudopneumoniae [4] were included. A total of 12 isolates belonging to the species Haemophilus influenzae (NCTC 8143T), Moraxella catarrhalis (ATCC 25238T and clinical isolate VG S86 0025), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213 and NCTC 08530), S. epidermidis (CCM2 124T and CNRS N860069), Streptococcus agalactiae (LMG 14694T), S. anginosus (LMG 14502T), S. gallolyticus (LMG 16802T), S. mutans (LMG 14558T) and S. pyogenes (LMG 14237), i.e. species also present in the upper airway tract and/or other Streptococcus species, were used to test the specificity of primer set Spne1-Spne2Rb. In addition, S. parasanguinis (LMG 14537T and LMG 14538) and S. sanguinis (LMG 14656, LMG 14657 and LMG 14702T) isolates were used to test the specificity of primer set Spne1-Spne2Rb.

Table 1.

Species and strains studied, phenotypic characteristics, and results for PCR assays

| Speciesa | Strain Number | Original Numberb | Spne-PCR | psaA-PCR | lytA-PCR | ply-PCR | spn9802-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus mitis | STR025 | LMG 14557T | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR056 | LMG 14552 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR226 | 94 03 0728 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR227 | 94 04 0401 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR228 | 97 03 2943 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR229 | 98 05 5898 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR230 | 98 07 1207 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus mitis | STR231 | 98 09 0066 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR024 | LMG 14553 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR028 | LMG 14532T | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR029 | LMG 14533 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR030 | LMG 14534 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR232 | 94 08 5574 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR233 | 98 05 5050 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus oralis | STR234 | 98 10 1512 | - | - | - | - | |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis | STR031 | LMG 14537T | - | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis | STR032 | LMG 14538 | - | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | STR038 | LMG 14656 | - | NT | NT | NT | - |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | STR039 | LMG 14657 | - | NT | NT | NT | - |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | STR059 | LMG 14702T | - | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR061 | LMG 14545Tit> | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR062 | LMG 15155 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR063 | LMG 16738 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR235 | 93 08 1310 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR236 | 93 09 03230 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR237 | 93 09 1111 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR238 | 98 10 1630 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR239 | 98 10 3326 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | STR240 | 98 10 3367 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR119 | KTL004 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR120 | KTL005 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR125 | KTL013 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR127 | KTL017 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR141 | KTL043 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR144 | KTL051 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR147 | KTL056 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR149 | KTL063 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR155a | KTL076 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae. Group I: oR C+ A+ | STR164 | KTL093 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae. (Group I: oR C+ A+) | STR157 | KTL079 | - | - | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae | STR269 | CCUG 48465 | - | - | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae | STR270 | CCUG 49455T | - | - | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae | STR271 | CCUG 50866 | - | - | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIa: oR C- A+ | STR150 | KTL065 | - | - | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIa: oR C- A+ | STR162 | KTL089 | - | - | - | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIa: oR C- A+ | STR165 | KTL096 | - | - | + | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR122 | KTL007 | - | - | - | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR133 | KTL028 | - | - | - | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR130 | KTL021 | - | - | - | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR137 | KTL035 | - | - | - | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR152 | KTL069 | - | - | + | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR153 | KTL072 | - | - | - | + | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR131 | KTL022 | - | - | + | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIb: oR C- A- | STR151 A | KTL068 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR118 | KTL003 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR121 | KTL006 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR136 | KTL034 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR138 | KTL038 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR145 | KTL054 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR154 | KTL073 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR123 | KTL008 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR128 | KTL019 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR132 | KTL023 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR134 | KTL029 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR139 | KTL039 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR158 | KTL081 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR159 | KTL083 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR156 | KTL077 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR140 | KTL041 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR160 | KTL085 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR161 | KTL087 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR135 | KTL030 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Streptococcus sp. Group IIc: oR C- A- | STR143 | KTL050 | - | - | - | - | - |

a: oR: optochin resistant, C: capsule, A: AccuProbe.

b: CCUG: Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg, Sweden; KTL: National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, Finland; LMG: LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie, Gent Culture Collection.

NT: not tested

DNA-extraction was carried out by alkaline lysis as described previously [15]. always starting from one colony.

spn9802-PCR assay

The amplification reactions were performed as described previously [9], with minor modifications. Briefly, amplification was performed in a reaction mixture of 10 μl, containing 5 μl PCR GoTaqGreen Mix (Promega Benelux, Leiden, the Netherlands), 2 μM of each of the forward primer spn9802-143F and the reverse primer spn9802-304R and 1 μl of the DNA extract. The following thermal cycling profile was applied, using a Veriti™ Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Ca.): initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, then 25 cycles consisting of 94°C for 10 sec, 58°C for 15 sec and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. All PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Newly developed PCR assay: 16S rRNA gene based Spne-PCR assay

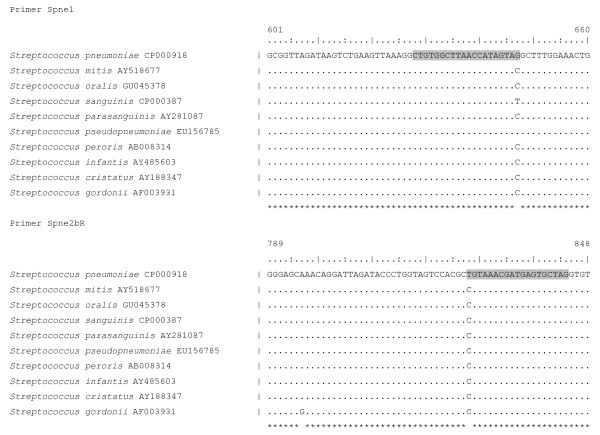

Extensive data-mining using commercial software (Integrated Database Network System IDNS™, SmartGene, Zug, Switzerland), which allows rapid screening of validated published sequences of species of interest against other closely related species was used to design primers for the specific amplification of S. pneumoniae. Primers were designed to match exactly 2 positions within the 16S rRNA gene, which allow to distinguish S. pneumoniae from S. pseudopneumoniae (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequence and position of the primers, newly developed in this study, specific for amplification of S. pneumoniae, and the homologous sequences for the S. mitis group species.

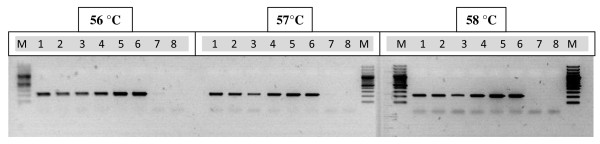

Amplifications were performed on an Applied Biosystems Veriti thermal cycler in reaction mixtures of 10 μl containing 5 μl PCR GoTaqGreen Mix (Promega Benelux, Leiden, the Netherlands), 0.5 μM of each of the two primers and 1 μl of the DNA extract. The 16S rRNA gene primers Spne1-Spne2Rb was designed to amplify S. pneumoniae, and the stringent annealing temperature was determined by gradient PCR as 57°C (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Gradient Spne-PCR results for six S. pneumoniae and two S. pseudopneumoniae isolates. M: marker (100 basepair ladder); lanes 1-6: S. pneumoniae isolates STR235 (lane 1), STR236 (lane 2), STR237 (lane 3), STR239 (lane 4), STR144 (lane 5), STR147 (lane 6); lanes 7-8:S. pseudopneumoniae isolates STR269 (lane 7) and STR157 (lane 8).

The cycling parameters were 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 10 sec at 94°C, 15 sec at 57°C, 1 min at 72°C, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The indicated primers are amplifying a 217 bp product of the 16S rRNA gene of S. pneumoniae.

Other PCR assays, i.e. ply- [16], psaA- [17] and lytA-PCR [18] were described previously [11].

Sequence analysis

Published streptococcal and other 16S rRNA sequences were extracted from EMBL using proprietary extraction methods based on sequence profiles and annotation searches; representative sequences for each species were determined using a proprietary algorithm developed by SmartGene for bacterial 16S rRNA sequences (SmartGene IDNS™ Bacteria Module). Sequences were analyzed and compared using search and alignment functions of the IDNS™ Bacteria Module of SmartGene. Results were exported as CLUSTAL-A or FASTA files for further analysis.

Results & Discussion

Previously we reported on encapsulation, AccuProbe hybridization and psaA, lytA and ply-PCR results for a collection of 49 optochin resistant alpha-hemolytic streptococcal isolates, suspected of being atypical pneumococci [11]. We concluded that for some strains identification problems continue to exist, despite the application of combined genotypic and phenotypic tests and we found psaA-PCR to be the most specific genotypic technique for the identification of genuine pneumococci and optochin resistant pneumococci. In addition, in this study, 16S rRNA gene based primers Spne1 and Spne2Rb (Spne-PCR) were designed to amplify S. pneumoniae isolates and we tested these primers for specific amplification of S. pneumoniae using the same, previously well-studied selection of isolates [11], to which three S. pseudopneumoniae and two S. parasanguinis isolates were added. Also, we tested the specificity of a PCR assay, i.e. spn9802-PCR [9], that was described in the meantime for amplification of S. pneumoniae.

All five PCR assays were negative for seven commonly found respiratory tract species, for 8 S. mitis group isolates, for 7 S. oralis isolates and for the 19 optochin R streptococcal isolates for which we had already concluded in the previous study [11] that they were non S. pneumoniae. In addition, Spne-PCR was negative for the three S. sanguinis and the two S. parasanguinis isolates.

All five PCR assays were positive for the nine optochin susceptible S. pneumoniae isolates included and for the ten optochin resistant streptococci, which had been considered as S. pneumoniae already, based on the PCR results from our previous study [11](Table 1).

Thus far, all five PCR assays were found to be equally specific. However, for a total of 11 optochin R streptococcal isolates, designated during the previous study as group IIa and group IIb, four were positive with lytA-PCR, nine with ply-PCR and Spn9802-PCR (9), whereas none of these isolates yielded a positive result when tested with psaA-PCR and Spne-PCR.

The S. pseudopneumoniae type strain CCUG 49455T, the two S. pseudopneumoniae reference isolates CCUG 48465 and CCUG 50866, and one optochin-resistant pneumococcus-like isolate (KTL079) were positive with lytA-PCR, ply-PCR and spn9802-PCR, but negative with Spne-PCR and psaA-PCR. Sequence determination of the 16S rRNA gene (accession number: FJ827123) identified this clinical isolate unambiguously as S. pseudopneumoniae. This isolate was also positive with AccuProbe (Table 1).

Several primer sets have been described for the species specific amplification of S. pneumoniae. However, in our hands, the primer sets lytA [18,19], ply [16] and spn9208 [20], were found to amplify strains of S. pseudopneumoniae as well. Also the commercial AccuProbe hybridization assay yielded a false positive result for the single S. pseudopneumoniae isolate that was tested by others [4] and for one strain (KTL079) that was tested by us in our previous study [11].

The PCR-assay Spne-PCR, described here, is specific for S. pneumoniae, without cross-reactivity to the four S. pseudopneumoniae strains tested. The differentiation of S. pneumoniae from S. pseudopneumoniae is important since the pathogenic potential of S. pneumoniae is far higher than that of S. pseudopneumoniae. The clinical relevance of S. pseudopneumoniae has not yet been established, although it may be associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [21].

In addition, the advantage of a specific PCR test on the basis of the 16S rRNA gene is that there are several copies of this gene, i.e. 5 to 6 in other Streptococcus species [22] and 4 copies in the fully sequenced genome of S. pneumoniae R6 (AE007317), thus possibly enhancing sensitivity when this PCR is applied for the direct detection and identification of S. pneumoniae in clinical samples.

In addition, 16S rRNA gene sequencing is a standard method in microbial taxonomy and can be applied directly on the amplified products of this PCR assay to to help resolve potentially ambiguous results.

Conclusions

Spne-PCR, described here, and psaA-PCR [17] were the only two out of 5 PCR assays tested, which did not misidentify S. pseudopneumoniae as S. pneumoniae. The approach using representative sequences rather than unfiltered data from Genbank enabled us to select the correct sites for reliable species differentiation out of less relevant and consistent variations and allowed us to design highly specific primers. Future studies should enable us to develop an assay specifically for S. pseudopneumoniae and a real-time, multiplex assay for rapid discrimination of the most important viridans streptococci in bacterial cultures or patient samples.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NAE, SE, RV and MV participated in the development of the study design, the analysis of the study samples, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the writing of the report. TK, TDB, BS, EA and PD participated in the analysis of the study samples and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Nabil Abdullah El Aila, Email: Nabil.ElAila@UGent.be.

Stefan Emler, Email: emler@smartgene.com.

Tarja Kaijalainen, Email: tarja.kaijalainen@thl.fi.

Thierry De Baere, Email: Thierry.debaere@iph.fgov.be.

Bart Saerens, Email: BartSaerens@gmail.com.

Elife Alkan, Email: ElifeAlkan@gmail.com.

Pieter Deschaght, Email: Deschaght.Pieter@UGent.be.

Rita Verhelst, Email: Rita.Verhelst@UGent.be.

Mario Vaneechoutte, Email: Mario.Vaneechoutte@UGent.be.

Acknowledgements

Nabil Abdullah El Aila is indebted for a PhD Research funded by BOF-DOS of the University of Ghent-Belgium. Pieter Deschaght is indebted for a PhD Research funded by the IWT (Belgium). BOF-DOS or IWT were not involved in the development of the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report nor in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Ortqvist A, Hedlund J, Kalin M. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;26(6):563–574. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-925523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanjaard L, Ende A van der, Rumke H, Dankert J, van Alphen L. Epidemiology of meningitis and bacteraemia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae in The Netherlands. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2000;89(435):22–26. doi: 10.1080/080352500300051495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozkiewicz D, Daniluk T, Sciepuk M, Zaremba ML, Cylwik-Rokicka D, Luczaj-Cepowicz E, Milewska R, Marczuk-Kolada G, Stokowska W. Prevalence rate and antibiotic susceptibility of oral viridans group streptococci (VGS) in healthy children population. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(Suppl 1):191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbique JC, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, Quesne G, Carvalho Mda G, Steigerwalt AG, Morey RE, Jackson D, Davidson RJ, Facklam RR. Accuracy of phenotypic and genotypic testing for identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae and description of Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(10):4686–4696. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4686-4696.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias CA, Agnes G, Frazzon AP, Kruger FD, d'Azevedo PA, Carvalho Mda G, Facklam RR, Teixeira LM. Diversity of mutations in the atpC gene coding for the c Subunit of F0F1 ATPase in clinical isolates of optochin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae from Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):3065–3067. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00891-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes S, Sa-Leao R, de Lencastre H. Optochin resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae strains colonizing healthy children in Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(1):321–324. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02097-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar SI, Frias MJ, Santos L, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M. Emergence of optochin resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae in Portugal. Microb Drug Resist. 2006;12(4):239–245. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.12.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaijalainen T, Saukkoriipi A, Bloigu A, Herva E, Leinonen M. Real-time pneumolysin polymerase chain reaction with melting curve analysis differentiates pneumococcus from other alpha-hemolytic streptococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53(4):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Seki M, Nakano Y, Kiyoura Y, Maeno M, Yamashita Y. Discrimination of Streptococcus pneumoniae from viridans group streptococci by genomic subtractive hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(9):4528–4534. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4528-4534.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messmer TO, Sampson JS, Stinson A, Wong B, Carlone GM, Facklam RR. Comparison of four polymerase chain reaction assays for specificity in the identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;49(4):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhelst R, Kaijalainen T, De Baere T, Verschraegen G, Claeys G, Van Simaey L, De Ganck C, Vaneechoutte M. Comparison of five genotypic techniques for identification of optochin-resistant pneumococcus-like isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(8):3521–3525. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3521-3525.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaijalainen T, Rintamaki S, Herva E, Leinonen M. Evaluation of gene-technological and conventional methods in the identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;51(1):111–118. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(02)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho Mda G, Tondella ML, McCaustland K, Weidlich L, McGee L, Mayer LW, Steigerwalt A, Whaley M, Facklam RR, Fields B. Evaluation and improvement of real-time PCR assays targeting lytA, ply, and psaA genes for detection of pneumococcal DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2460–2466. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02498-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdeldaim GM, Stralin K, Olcen P, Blomberg J, Herrmann B. Toward a quantitative DNA-based definition of pneumococcal pneumonia: a comparison of Streptococcus pneumoniae target genes, with special reference to the Spn9802 fragment. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60(2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaneechoutte M, Claeys G, Steyaert S, De Baere T, Peleman R, Verschraegen G. Isolation of Moraxella canis from an ulcerated metastatic lymph node. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(10):3870–3871. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3870-3871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintamaki S, Saukkoriipi A, Salo P, Takala A, Leinonen M. Detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA by using polymerase chain reaction and microwell hybridization with Europium-labelled probes. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;50(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(02)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KE, Lake D, Crook J, Carlone GM, Ades E, Facklam R, Sampson JS. Confirmation of psaA in all 90 serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae by PCR and potential of this assay for identification and diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(1):434–437. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.434-437.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llull D, Lopez R, Garcia E. Characteristic signatures of the lytA gene provide a basis for rapid and reliable diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1250-1256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvin JC, Reilly PA, Roudabush RM, Barnes WJ, Salmen A, Jackson GW, Beninga KK, Astorga A, McCleskey FK, Huff WB. Sensitive and specific method for rapid identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae using real-time fluorescence PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(10):3446–3451. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3446-3451.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Yuyama M, Maeda S, Ogawa H, Mashiko K, Kiyoura Y. Genotypic identification of presumptive Streptococcus pneumoniae by PCR using four genes highly specific for S. pneumoniae. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 6):709–714. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith ER, Podmore RG, Anderson TP, Murdoch DR. Characteristics of Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae isolated from purulent sputum samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(3):923–927. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.923-927.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley RW, Leigh JA. Determination of 16S ribosomal RNA gene copy number in Streptococcus uberis, S. agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae and S. parauberis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]