Abstract

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a common birth defect for which few causative genes have been identified. Several candidate regions containing genes necessary for normal diaphragm development have been identified, including a 4–5 Mb deleted region at chromosome 1q41–1q42 from which the causative gene(s) has/have not been cloned. We selected the HLX gene from this interval as a candidate gene for CDH, as the Hlx homozygous null mouse has been reported to have diaphragmatic defects and the gene was described as being expressed in the murine diaphragm. We re-sequenced HLX in 119 CDH patients and identified four novel single nucleotide substitutions that predict amino acid changes: p.S12F, p.S18L, p.D173Y and p.A235V. These sequence alterations were all present in patients with isolated CDH, although patients with both isolated CDH and CDH with additional anomalies were studied. The single-nucleotide substitutions were absent in more than 186 control chromosomes. In-situ hybridization studies confirmed expression of Hlx in the developing murine diaphragm at the site of the junction of the diaphragm and the liver. Although functional studies to determine if these novel sequence variants altered the inductive activity of Hlx on the α-smooth muscle actin and SM22α promoters showed no significant differences between the variants and wild-type Hlx, sequence variants in HLX may still be relevant in the pathogenesis of CDH in combination with additional genetic and environmental factors.

Keywords: α-smooth muscle actin promoter; animal models; congenital diaphragmatic hernia; HLX, HLX1; mutation detection; SM22α

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a common birth defect with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 2500 live births (1). The prenatal and neonatal mortality for CDH is high and there is significant long-term morbidity in survivors (2). There is substantial evidence implicating genetic factors in the pathogenesis of CDH(3–6), but there are few data on the causative genes to date. In humans, only one mutation and two sequence variants of unknown significance have been demonstrated in the FOG2 gene in isolated CDH (7, 8). In patients with CDH and additional anomalies due to a recognizable genetic syndrome, mutations have been reported in several genes (9–11), but the total number of causative mutations remains small.

Gene identification in isolated CDH has been challenging because the majority of cases are sporadic. Array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) has been used to identify and delineate chromosome deletions in patients with CDH and multiple additional anomalies (12–14). These deleted chromosome regions have been assumed to contain gene(s) necessary for normal diaphragm formation, and candidate genes for diaphragm development from these regions have been selected for sequencing in isolated CDH patients (15). We have previously used array CGH and microsatellite markers to map a de novo, interstitial deletion of chromosome 1q41–1q42 that was an estimated 10–12 Mb in size in a male with CDH who had a karyotype of 46,XY, del(1)(q32.3q42.2) (15). Several other patients with CDH and deletions of 1q41–1q42 have subsequently been reported and the deleted interval associated with CDH has been narrowed (13,16). Shaffer et al. (2007) (16) examined seven cases with de novo deletions of chromosome 1q41–1q42, including the patient reported by Kantarci et al. [2006] (13) and a patient with CDH, pulmonary hypoplasia, cerebellar hypoplasia and dysmorphic features previously described by Van Hove et al. (1995) (17). The minimum region of deletion overlap in those two patients was between UCSC 217,981,476 and 222,703,737 (version hg18 of the UCSC genome browser), from the proximal break point described in Kantarci’s patient (13), to the distal break point described in Van Hove’s patient (16). This region contains at least 20 known genes, including HLX, and numerous putative transcripts (UCSC Genome Browser).

We searched for candidate genes for CDH at this 1q41–1q42 region, basing our selection on gene expression and on the phenotype of animal models with loss of gene function when known. We chose the HLX gene because of reported gene expression in the murine diaphragm, together with a murine animal model of loss of function for this gene in which the mutant mice had diaphragmatic defects (18, 19). We re-sequenced the HLX gene in 23 patients with isolated CDH, and as we found one novel nucleotide alteration that was not present in controls, continued to re-sequence HLX in a further 96 patients with CDH that had either isolated CDH or CDH with additional anomalies. We present data that demonstrate four, novel sequence variants that result in amino acid substitutions in HLX in CDH patients and provide information concerning functional studies pertaining to these single-nucleotide substitutions. We also provide further data on expression studies using in-situ hybridization for Hlx in the murine diaphragm during development.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

DNA samples were obtained from probands and parents using two protocols approved by the Committee for Human Subjects Research (CHR) at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF; CHR numbers H41842-22157-06 and H41842-26613-04). We used 23 DNA samples from diaphragmatic hernia patients recruited through UCSF and 96 DNA samples obtained from the blood spots of newborn children with diaphragmatic hernias through the California Birth Defects Monitoring Program. None of the first 23 patients was believed to have an underlying genetic syndrome as an explanation for the diaphragmatic defect, either because of a lack of additional features or because of the presence of few additional anomalies that did not form a recognizable syndromic pattern, and there was no history of maternal or gestational diabetes for any patient (Table 1). Phenotypic features were obtained from patient records or from patient databases and tabulated for each patient. The blood spot samples were subject to whole genome amplification before use (GenomiPhi™, GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ). All the available patient records were inspected by a Clinical Geneticist (A. M. S.), but not all the patients were examined, and karyotyping or microarrays were not performed in all individuals. For the 96 blood spot samples, patients either had isolated CDH or CDH with anomalies as previously described (15).

Table 1.

Clinical features of the first group of 23 patients with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and single nucleotide polymorphisms in the coding regions of HLXa

| Patient | CDH laterality |

Pulmonary hypoplasia |

Other anomalies |

Sex | Survival |

HLX Exon 1 SNPs |

HLX Exon 2 SNP |

HLX Exon 4 SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L | Yes L | Nil | M | A | p.S116P | — | p.P356L/c.1083G>A |

| 2 | R | Yes R | Nil | M | A | — | — | p.P356L/p.A387G |

| 3 | R | No | Pectus excavatum | M | A | p.S116P | — | p.P356L/ c.1083G>A |

| 4 | L | No | Bilateral inguinal hernias | M | A | p.S116P | — | — |

| 5 | L | Yes L | PDA, ASD | M | A | — | c.705A>C | — |

| 6 | L | No | PDA | M | A | — | — | — |

| 7 | L | Yes L | nil | M | A | — | — | — |

| 8 | L | No | nil | M | D | — | — | p.P356L/p.A387G |

| 9 | L | No | PFO, TR | F | A | p.S116P | — | p.P356L/ c.1083G>A |

| 10 | R | Yes R | ASD, PDA, PFO, Cryptorchidism |

M | A | p.S116P | — | — |

| 11 | Bilateral | Yes | ASD, PDA, Dextroposition; Cryptorchidism |

M | D day 1 | — | — | p.P356L/ c.1083G>A |

| 12 | L | Yes L | 11 ribs; Bifid thumb | M | D day 18 | — | — | p.P356L/ c.1083G>A |

| 13 | L | Yes | PDA, TR, Cryptorchidism | M | A | p.S116P | — | — |

| 14 | R | Y R and | ASD; Hepatopulmonary fusion |

M | A | — | — | p.P356L/ c.1083G>A |

| 15 | Antral hernia | No | nil | F | A | — | — | p.P356L/p.A387G |

| 16 | R | Yes R | Cleft liver, VSD, bicuspid pulmonic valve, accessory spleen |

F | D 10 w | p.Q125H | c.705A>C | p.P356L/p.A387G |

| 17 | L | Yes L | Dextroposition, PDA, PFO | M | NA | — | — | p.P356L/p.A387G |

| 18 | L | No | Mild TR | F | A 8 m | p.Q125H | — | — |

| 19 | L | Yes | Pelviectasis; Cryptorchidism | M | NA | — | — | — |

| 20 | L | No | PDA | M | A | p.Q125H | — | p.P356L/p.A387G |

| 21 | L | Yes | PDA, PFO, TR, pyloric stenosis |

M | D44h | — | — | — |

| 22 | NA | No | Pectus excavatum; Cryptorchidism |

M | A 16 m | p.S116P | — | — |

| 23 | L | No | ASD; Hydronephrosis | M | NA | p.S116P | — | — |

A, alive; ASD, atrial septal defect; F, female; D, deceased; h, hours; L, left; R, right; M, male; m, months; NA, not available; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PFO, patent foramen ovale; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; VSD, ventricular septal defect; w, weeks. All hernias were posterolateral unless specified.

Nucleotides are numbered from A in start codon = 1; transcript NM_021958 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=nuccore=toolbar).

Genomic sequencing of the HLX gene

We sequenced the exons and the exon–intron boundaries of the HLX gene in 23 patients with CDH. We then used a high-throughput approach (15) to sequence the HLX gene in a larger group of 96 patients with CDH. We examined 80–100 bp of the 5′ untranslated region upstream from the start codon, but the promoter was not studied. A minimum of 186 ethnically matched control chromosomes were screened for each novel sequence alteration, either by restriction length polymorphism fragment analysis or by genomic sequencing. For the blood spot samples, family members were unable to be contacted to verify if alterations were de novo.

Protein comparison analysis

We previously compared the Hlx protein sequences from nine species (20). We expanded this comparison with Hlx protein sequences from another eight species. These sequences were identified using a protein vs translated DNA BLAST search (TBLASTN) using the Hlx homeodomain (identical in all species tested) against the relevant database from Ensembl (www.ensembl.org) (20).

In-situ hybridization with murine embryo sections

We used a full-length murine cDNA clone for Hlx (Full Length Mammalian Gene Collection 1380899; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A BLAT search using the sequence from the 2192-bp clone insert did not show any significant match to other murine genes or evolutionarily conserved regions (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgBlat?command = start&org = Mouse&db = mm9&hgsid = 117481693; data not shown).

In-situ hybridization was performed on murine sagittal sections obtained from E11.5, E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5 embryos after fixation and embedding according to previously published methods (21). For probe generation, the Hlx cDNA clone was cut with restriction enzymes and ethanol precipitated before generation of the RNA probes (DIG RNA labeling kit; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Probes were quantified using dot-blot methodology before resuspension in formamide. The in-situ hybridization protocol has been published previously (21). Murine embryos were fixed, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at a thickness of 8 µm, and dewaxed. The sections were digested for 8 min in 40 µg/ml proteinase K, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and dehydrated through ethanol washes. In-situ hybridization was performed with antisense or sense probes in 50 µl of hybridization buffer. After hybridization, sections were treated with RNaseA using previously described standard methods (22). Signal was detected using an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody and BM Purple alkaline phosphatase substrate (Roche). We examined the expression of Hlx in the murine diaphragm using sense probes and anti-sense probes at E11.5, E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5.

Functional analysis

We have unpublished data showing that Hlx is required for smooth muscle differentiation and, in particular, α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and γ-smooth muscle actin expression (γSMA; M. Bates, personal communication). In mice that are homozygous null for Hlx, the expression of αSMA is delayed and the expression of γSMA is seen only at trace levels at best. We therefore decided to use smooth muscle promoters with a luciferase assay for functional studies. The human HLX cDNA was subcloned into pMSCV-IRES-GFP, a bicistronic plasmid vector that expresses green fluorescent protein under a mouse stem cell virus promoter. Constructs with point mutations were prepared using the Quik-Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and resulting constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The αSMA construct contained a 5368-bp fragment of the rat αSMA gene (−2555 to +2813) subcloned into pGL3-Basic (23). The SM22α promoter construct contained a 482-bp fragment of the mouse SM22α gene (−441 to +41) subcloned into pGL2-Basic (24, 25). HLX regulation of promoter activity was assayed by transfection into an Hlx−/− mesenchymal cell line that was derived from an E11.5 Hlx−/− embryo (9–3 cells) (Bates et al., unpublished). Transfections were performed in triplicate wells in two independent experiments using SuperFect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). All transfections included pRL-SV40, which expresses Renilla luciferase, to control for cell density and transfection efficiency. After incubating transfected cells for 2 days, luciferase activities were determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Ratios of firefly luciferase (expressed by pGL3 constructs with promoters of interest, expressed in relative luciferase units, or RLUs) to Renilla luciferase (expressed by pRL-SV40) were calculated for each well. Results for triplicate wells from duplicate experiments were used to determine means, standard errors, and statistical significance (p < 0.01 using Student’s t-test).

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Exponentially growing cells C2C12 myoblast cells were plated in Petri dishes at a density of 2.4 × 104 cells per milliliter. When the cells were 75–90% confluent, growth medium was replaced with differentiation medium containing 2% horse serum (Hyclone, Logan UT). Cells were harvested on days 1, 3 and 6 and RNA was obtained by standard methods (RNeasy kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). At day 6, the majority of the cells had formed elongated myotubes. cDNA synthesis was performed from total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).The expression of Hlx (TaqMan probe Mn00468056_m1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and Hprt1 (TaqMan probe Mn03024075_m1; Applied Biosystems) were assayed at days 1, 3 and 6 using real-time PCR and an ABI PRISM 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All reactions were run in sets of four identical reactions. As the expression of the Hprt housekeeping gene did not change significantly during the differentiation process (data not shown), quantification analysis was performed with the ΔΔCt method using Hprt as a control.

Results

Patient phenotypes

In the first and smaller patient group comprising 23 CDH patients, five had right-sided CDH (R-CDH) and 15 had left-sided CDH (L-CDH; Table 1). One patient had an antral diaphragmatic hernia, one had bilateral CDH and in one the type of diaphragmatic defect was not specified (Table 1). All the patients had either isolated CDH or CDH in combination with anomalies that did not constitute a known recognizable syndrome. The clinical details of the larger group of 96 CDH patients have previously been reported (15).

Novel sequence variants in the HLX gene in patients with CDH

In the first group of 23 patients with CDH, we found c.704C>T, predicting p.A235V in exon 2 of HLX in an Hispanic patient (Table 2; Fig. 1a). Nucleotides are numbered from A in start codon 1; transcript NM_021958 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db = nuccore&itool = toolbar). This alteration was not present in the patient’s unaffected mother or sister, or in 140 Hispanic control chromosomes, or in 112 Caucasian control chromosomes. DNA from the father of the patient was unavailable. This sequence variant is adjacent to c.705A>C, a SNP that does not alter the amino acid sequence of the protein (Table 2). The patient with p.A235V was heterozygous for the c.705A>C SNP, but his mother was wild type at this locus. Cloning of exon 1 in the patient revealed that the c.705A>C SNP was not inherited on the maternal allele (data not shown), and it is possible that the p.A235V sequence variant was therefore inherited from the patient‘s father in cis with the c.705A>C SNP. However, p.A235V is rare and was not identified in 252 control chromosomes as detailed above. The SIFT (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT.html) database predicted that this variant would not be tolerated (p < 0.05), although Polyphen (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/) predicted that the variant was benign.

Table 2.

Summary of re-sequencing data in the coding regions of the HLX gene in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) patients

| HLX Exon | Nucleotide alteration |

Amino acid alteration |

Phenotype | Interpretation | Known SNP+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.35C>T | p.S12F | R CDH | Unknown | No |

| 1 | c.53C>T | p.S18L | R CDH | Unknown | No |

| 1 | c.346T>C | p.S116P | Varied CDH | SNP | Yes |

| 1 | c.375A>C | p.Q125H | CDH; 3/26 (11.5%) patients |

2/102 (1.96%) controls; SNP | Yes |

| 1 | c.C413insa | Insertion p.138 (PPQQQ) |

CDH; 2/26 (7.7%) patients |

6/146 (4.1%) controls; SNP | Yes |

| 1 | c.517G>T | p. D173Y | R CDH | Unknown | No |

| 2 | c.704C>T | p.A235V | L CDH; ASD/PDA | 0/140 Hispanic controls; 0/112 Caucasian controls; Unknown |

No |

| 2 | c.705A>C | p.A235A; Silent | NA | 3/140 (2.1%) Hispanic controls; SNP | No |

| 4 | c.1067C>T | p.P356L | CDH | SNP | Yes |

| 4 | c.1083G>A | p.E361E; Silent | NA | Silent Aa/SNP | Yes |

| 4 | c.1160C>G | p.A387G | CDH | SNP | Yes |

Aa, amino acid; ASD/PDA, atrial septal defect/patent ductus arteriosus; L CDH, isolated left-sided CDH; N, no; NA, not applicable; R CDH, isolated right-sided CDH; known SNP+, known single nucleotide polymorphism in dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) or Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html); Y, yes. Nucleotides are numbered from A in start codon = 1; transcript NM_021958 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=nuccore=toolbar).

Gccgcagcaacagcc.

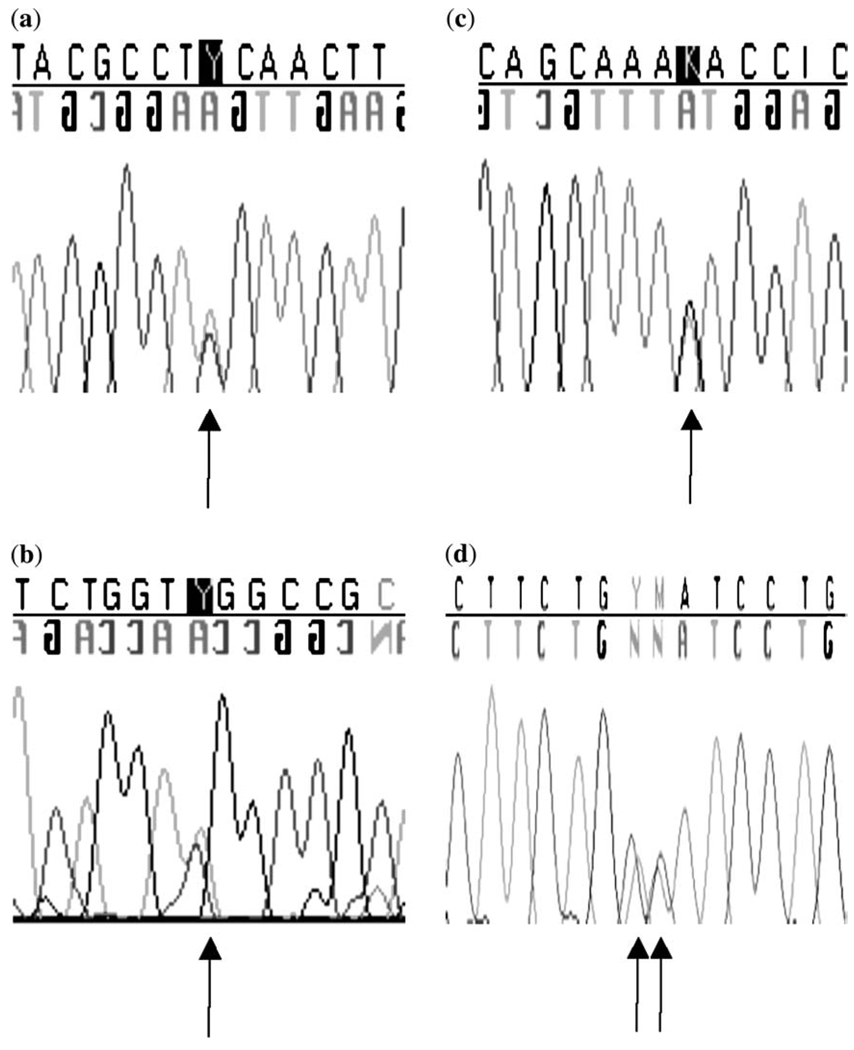

Fig. 1.

(a) Chromatogram showing c.35C>T, predicting p.S12F in the HLX gene from a patient with a right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. (b) Chromatogram showing c.53C>T, predicting p.S18L in the HLX gene from a patient with a right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. (c) Chromatogram showing c.517G>T, predicting p.D173Y in the HLX gene from a patient with a right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. (d) Chromatogram showing c.704C>T, predicting p.A235V in the HLX gene from a patient with a left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

We studied the second group of 96 patients with CDH for HLX sequence variants and identified three other novel variants, c.35C>T, predicting p.S12F, c.53C>T, predicting p.S18L and c.517G>T, predicting p.D173Y (Table 2; Fig. 1b–d). The Polyphen predictions for these alterations were p.S12F, possibly damaging; p.S18L, possibly damaging; and p.D173Y, probably damaging; SIFT predicted that all variants would not be tolerated. None of the sequence variants was detected in a minimum of 186 control chromosomes. All these alterations were verified in genomic DNA, but we could not determine if the variants were de novo, as we had no access to parental samples for these patients. Finally, we also sequenced HLX in our patient with CDH and multiple anomalies who had a large chromosome deletion including the HLX gene at 1q41–1q42 (15), but did not identify any sequence alterations on the second allele.

We found several SNPs in HLX that were useful for ruling out a deletion of the entire gene (Table 1 and Table 3). These polymorphisms were p.S116P and p.Q125H in exon 1, c.705A>C (silent) in exon 2, p.P356L, p.A387G and c.1083G>A (silent) in exon 4. Using these SNPs, a deletion involving the entire HLX gene could be excluded in 18/22 (82%) of the isolated CDH patients, thus making whole-gene deletion unlikely as a common mutational mechanism.

Table 3.

Summary of known and novel single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the coding regions of the HLX gene in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) patients

|

HLX exon |

db SNP rs# cluster ID |

Amino acid/nucleotide alteration |

Heterozygosity dbSNPa |

Allele frequency group 1b |

Allele frequency group 2c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 1 | rs12141189 | p.S116P | 0.35 | T = 0.81C = 0.19 | T = 0.73C = 0.27 |

| Exon 1 | rs62621984 | p.Q125H | — | C = 0.07A = 0.93 | C = 0.02A = 0.98 |

| Exon 1 | rs12041280 | p.A151T | — | Not detected | Not detected |

| Exon 2 | — | c.A1162C/silent | — | A = 0.95C = 0.05 | Not detected |

| Exon 4 | rs2738755 | p.P356L | 0.44 | T = 0.32C = 0.68 | T = 0.26C = 0.74 |

| Exon 4 | rs3738182 | p.E361E | 0.32 | Not detected | A = 0.14G = 0.86 |

| Exon 4 | rs11578466 | p.A387G | 0.14 | G = 0.14T = 0.86 | G = 0.13T = 0.87 |

Heterozygosity score dbSNP = heterozygosity score from dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/).

Allele frequency in 23 isolated CDH patients.

Allele frequency in 96 CDH patients, both isolated and with anomalies.

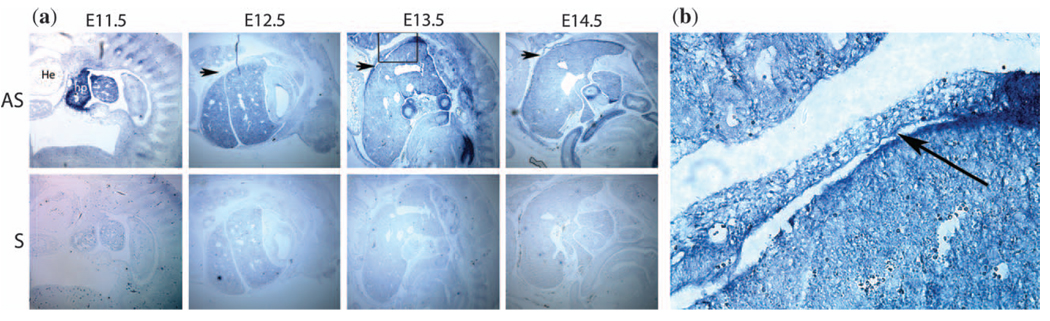

In-situ hybridization with murine embryo sections confirmed Hlx expression in the developing diaphragm

The expression of Hlx had previously been noted in the septum transversum underneath the heart at E10 (18). This structure is the precursor for the connective tissue of the diaphragm and the liver capsule (18). We confirmed similar expression at E11.5 (Fig. 3a). Hlx is also expressed in the diaphragm muscle at E13.5 (Fig. 3a) and more weakly in the diaphragm muscle at E12.5 and E14.5 (Fig. 3a). Expression was strongest at the sites of the junction of the diaphragm with the liver, and in the outermost layer of the liver (Figs. 3a and Fig. 3b). Expression appears to be present both in the muscle posteriorly and the connective tissue of the diaphragm anteriorly (Fig. 3). However, no cell-specific costaining has been performed.

Fig. 3.

(a) In-situ hybridization studies using a full-length Hlx antisense probe (Fig. 3a) and an Hlx sense probe at E11.5 (first panel), E12.5 (second panel), E13.5 (third panel) and E14.5 (fourth panel). In the E11.5 antisense panel: He, heart; hp, hepatic primordium. The developing diaphragm is located between these two structures (37). In the E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5 antisense panels, the arrows indicate the developing diaphragm. Expression of Hlx can be seen in the murine diaphragm and adjacent liver capsule with the antisense probe but not the sense probe, and expression appears strongest at E13.5. Hlx is also strongly expressed in the developing liver. (Fig. 3b) shows a higher magnification view (40×) from the E13.5 antisense section, site indicated by the box in Fig. 3a. Diaphragm staining is indicated by an arrow.

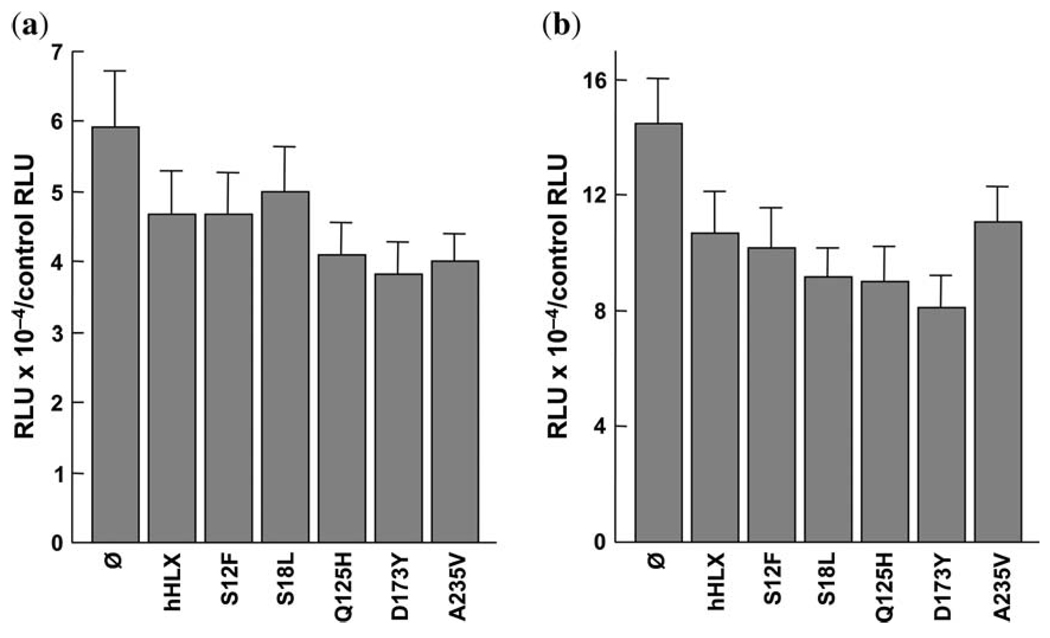

Functional analysis did not reveal a significant difference between the ability of wild-type Hlx and constructs with novel HLX sequence alterations to activate two downstream smooth muscle promoters

Unexpectedly, we found that Hlx decreased the activity of promoters for both αSMA and SM22α by ~60% in the Hlx−/− cell line prepared from an Hlx−/− embryo (Fig. 4). Expression of Hlx had no effect on a smooth muscle myosin promoter (Dr Owens, personal communication). However, the effect of Hlx on a given promoter’s activity can be stimulatory, inhibitory, or neither, depending on the Hlx−/− cell line used (M. Bates, unpublished observations). One explanation for these findings is that Hlx may require additional cofactors for enteric smooth muscle-specific gene regulation, as has been shown for Hlx regulation of interferon-γ expression in helper T lymphocytes (26), as well as in other gene regulatory systems (27–30). There was no significant difference in the ability to activate αSMA and SM22α between wild-type human HLX and any of the constructs containing the sequence variants (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Functional studies of the ability of wild-type Hlx and Hlx constructs with sequence variants to induce α-smooth muscle actin and SM22α promoter activity in a cell line derived from an Hlx−/− mouse. (a) The results for the α-smooth muscle actin promoter are shown. The x-axis has bars representing the different sequence variants and the y-axis has the values for ratios of firefly luciferase (expressed by pGL3 constructs with promoters of interest, expressed in relative luciferase units, or RLUs) to Renilla luciferase (expressed by pRL-SV40) for triplicate wells in duplicate experiments. (b) The results for the SM22α promoter are shown. The x-axis has bars representing the different sequence variants and the y-axis has the values for ratios of firefly luciferase (expressed by pGL3 constructs with promoters of interest, expressed in RLUs) to Renilla luciferase (expressed by pRL-SV40) for triplicate wells in duplicate experiments.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

We hypothesized that if Hlx was important in muscle differentiation in the developing diaphragm, its expression would be likely to increase during the differentiation of other, muscle-derived cell types, such as C2C12 cells. Our experiments showed that there was no significant change in Hlx expression during the differentiation of murine C2C12 cells (data not shown).

Discussion

The HLX gene (also known as HLX1, H2.0-like homeobox or HB24; OMIM 142995) is a member of the homeobox family of genes, with homology to the Drosophila homeobox gene H2.0. We selected this gene for study in patients with CDH because of its position within a deleted region in CDH patients (12, 13, 16), previous studies showing expression in the murine diaphragm during development (18) and a homozygous mouse model with loss of gene function that reportedly had diaphragmatic defects (19). A comparison of HLX orthologs in human and mouse showed that the genes share similar organization, with four exons and three introns and 85.4% identity between the human and mouse proteins, suggesting a similar function in both-species (20).

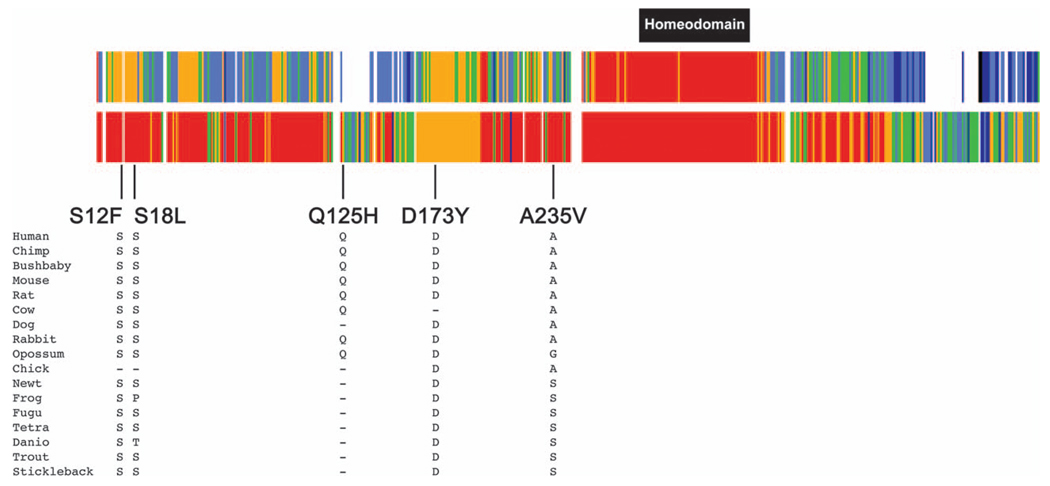

Our initial study included 23 CDH patients and, as we identified one amino acid substitution, p.A235V, we expanded our screen to include an additional 96 CDH patients and identified three more amino acid substitutions, p. S12F, p.S18L and p.D173Y. These sequence alterations have not been reported as SNPs and are present in highly conserved regions of the protein (Fig. 2). Our functional studies, however, were limited to the induction of α-smooth muscle actin and SM22α promoter activity by Hlx and did not show that any of the variants significantly altered protein function compared with wild type. However, none of our studies has examined the potential of Hlx to affect the early patterning of the diaphragm. We also identified several other polymorphisms in this gene in our cohort – p.Q125H in exon 1, present in 1.96% of normal control chromosomes and c.705A>C, a silent nucleotide alteration present in 2.1% of normal control chromosomes in exon 2.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of the HLX gene showing conserved residues at the site of the sequence variants predicting p.S12F, p.S18L, p.D173Y and p.A235V. The top bar shows conservation among the 17 species shown in the figure. Red indicates that the amino acids are identical in all 17 species; orange indicates that the amino acids are identical in 14–16 species; green indicates that the amino acids are identical in 11–12 species; light blue indicates that the amino acids are identical in 7–10 species; dark blue indicates that the amino acids are identical in four to six species; black indicates that the amino acids are identical in three species and white indicates that the amino acids are identical in one to two species. The second bar shows conservation among the eight mammalian species. Red indicates that the amino acids are identical in all eight species; orange indicates that the amino acids are identical in seven species; green indicates that the amino acids are identical in five to six species; light blue indicates that the amino acids are identical in four species; dark blue indicates that the amino acids are identical in three species.

Hlx expression was previously studied in the embryonic mouse using radioactive methodology and the gene was expressed most strongly in mesodermal tissues (18, 31). At E10, expression was present in the septum transversum of the diaphragm and at E11 to E12, hybridization signals were seen in the diaphragm and liver capsule (18, 31). At E12.5 and at E14.5, Hlx expression was still detectable in the diaphragm (18). Our results confirmed expression of Hlx in the liver and overlying the liver at E11.5. At later gestations, Hlx expression is strongest in the liver, liver capsule and intestines, but is also seen in the overlying diaphragm adjacent to the liver capsule (Fig. 3). Expression in diaphragm did not persist strongly at later gestations, whereas Hlx continues to be seen more strongly in the liver capsule at E14.5 (Fig. 3). The diaphragmatic expression of this gene at the time of murine diaphragm formation and closure is consistent with a role for this gene in diaphragm development.

Mice that were homozygous null for the Hlx gene have been made by targeted disruption of the gene to remove the homeobox and produce a null allele (19). Heterozygous mice were normal, but homozygous null mice died at E15. Dissection of the mutant mice at E14.5 showed an extremely small liver and reduced intestinal length, with abnormal development of the gut mesenchymal layer. The diaphragm of the null mice contained few muscle cells and was described as ‘herniated’ in every mutant embryo examined (28). The reason for the reduced numbers of muscle cells in the diaphragm of the Hlx-null mice was unknown at the time of this publication (28). Hlx was expressed in the myoblasts of the limb and branchial arches and gene expression was downregulated soon after the onset of myogenic differentiation (19). However, Hlx expression was described as unchanged using an RNAse protection assay in C2C12 myoblast cells that were induced to differentiate into myotubes (19). In addition, microarray studies looking at changes in gene expression during C2C12 differentiation showed no significant change in Hlx expression (32).We used quantitative RT-PCR to examine Hlx expression in differentiating C2C12 cells and also did not find any difference between Hlx expression in proliferating cells compared with differentiated cells, thus making it less likely that Hlx has a role in diaphragm muscle differentiation. Plausible roles for Hlx in myoblast proliferation or migration or connective tissue formation in the diaphragm or diaphragm patterning have not been studied.

Hlx is a transcription factor that has been implicated in cell proliferation in vitro in several different tissues, including placental extravillous trophoblasts and CD34 positive bone marrow cells (33, 34). Hlx expression can be stimulated when these cell types are exposed to cytokines or other growth factors, and thus is implicated in immature stem cell and progenitor stem cell development (34). Hlx is necessary for the development of the enteric nervous system, with homozygous null animals exhibiting abnormal developmental of the enteric nervous system and aberrant staining and restriction of PGP9.5 and Phox2b antibodies, which stain enteric neurons, to the stomach (35). However, similar data on the innervation of the diaphragms in Hlx-null mice is not available.

It is highly probable that CDH is multifactorial and genetically heterogeneous in etiology (4). In our study, we were unable to demonstrate that the rare HLX sequence variants in CDH patients significantly impaired protein function, thus implying that additional genes or environmental factors interacting with HLX sequence alterations may be required for manifestation of the diaphragmatic defect, if indeed HLX is important for diaphragm formation. The diaphragmatic hernias in the Hlx homozygous null mice were caused by two null alleles, implying loss of function, whereas the patients in our study had one sequence variant. This situation can be considered together with the results obtained for a more common deletion associated with CDH at chromosome 15q26, in which sequencing of all the known genes in the interval failed to reveal a responsible gene (15). However, for the chromosome 15q26 interval and CDH, the critical interval is smaller and there is an outstanding candidate gene, COUP-TFII (also known as NR2F2) in the 15q26 interval (36). This gene is known to be regulated by retinoic acid signaling and conditional knockout mice for this gene have diaphragmatic defects (36). In contrast, HLX is only one gene of many possible candidates in the 1q41–1q42 interval.

Conclusion

We have sequenced the HLX gene in 119 patients with diaphragmatic defects because HLX is in the deleted interval at chromosome 1q41–1q42 for several human patients with CDH, Hlx is expressed in the murine diaphragm at the time of diaphragm closure and Hlx homozygous null mice have been described to have diaphragmatic defects. We identified four highly conserved nucleotide alterations that predict novel amino acid substitutions and that were not present in ethnically matched control chromosomes, but our limited functional studies did not show that any of the substitutions significantly impaired the functional ability of Hlx to induce intestinal smooth muscle promoters. Although we have not proven that the HLX variants are etiologically important in diaphragm formation, it is still possible that they could contribute to diaphragm formation by interaction with other, as yet unknown, genetic or environmental factors.

Acknowledgements

Anne Slavotinek was generously funded by an R03 grant 5R03 HDO49411-02 from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), a Hellman Award (Hellman Family Trust) and a K08 grant HD053476-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health. Research conducted at the E.O. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Joint Genome Institute, supported by HL066681 (LAP), Berkeley-PGA, under the Programs for Genomic Application, funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, USA, was performed under Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231, University of California (LAP). The αSMA construct was kindly provided by Dr Gary Owens, University of Virginia and the SM22α promoter construct was kindly provided by Michael Parmacek, University of Pennsylvania. This publication was supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI grant number ULI RR024131. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Torfs CP, Curry CJ, Bateson TF, Honoré LH. A population-based study of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Teratology. 1992;46:555–565. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420460605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cass DL. Fetal surgery for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the North American Experience. Semin Perinatol. 2005;29:104–111. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pober BR, Lin A, Russell M, et al. Infants with Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia: sibling precurrence and monozygotic twin discordance in a hospital-based malformation surveillance program. Am J Med Genet. 2005;138:81–88. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holder AM, Klaassens M, Tibboel D, et al. Genetic factors in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:825–845. doi: 10.1086/513442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145:158–171. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slavotinek AM. Single gene disorders associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145:172–183. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackerman KG, Herron BJ, Vargas SO, et al. Fog2 is required for normal diaphragm and lung development in mice and humans. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:58–65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleyl SB, Moshrefi A, Shaw GM, et al. Candidate genes for congenital diaphragmatic hernia from animal models: sequencing of FOG2 and PDGFRalpha reveals rare variants in diaphragmatic hernia patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:950–958. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golzio C, Martinovic-Bouriel J, Thomas S, et al. Matthew-Wood syndrome is caused by truncating mutations in the retinol-binding protein receptor gene STRA6. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1179–1187. doi: 10.1086/518177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS, et al. Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat Genet. 2007;38:957–959. doi: 10.1038/ng2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasutto F, Sticht H, Hammersen G, et al. Mutations in STRA6 cause a broad spectrum of malformations including anophthalmia, congenital heart defects, diaphragmatic hernia, alveolar capillary dysplasia, lung hypoplasia, and mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:550–560. doi: 10.1086/512203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slavotinek A, Lee SS, Davis R, et al. Fryns syndrome phenotype caused by chromosome microdeletions at 15q26.2 and 8p23.1. J Med Genet. 2005;42:730–736. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kantarci S, Casavant D, Prada C, et al. Findings from aCGH in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH): a possible locus for Fryns syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140:17–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott DA, Klaassens M, Holder AM, et al. Genome-wide oligonucleotide-based array comparative genome hybridization analysis of non-isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:424–430. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slavotinek AM, Moshrefi A, Davis R, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: mapping of four CDH-critical regions and sequencing of candidate genes at 15q26.1–15q26.2. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:999–1008. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer LG, Theisen A, Bejjani BA, et al. The discovery of microdeletion syndromes in the post-genomic era: review of the methodology and characterization of a new 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome. Genet Med. 2007;9:607–616. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e3181484b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Hove JL, Spiridigliozzi GA, Heinz R, et al. Fryns syndrome survivors and neurologic outcome. Am J Med Genet. 1995;59:334–340. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320590311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lints TJ, Hartley L, Parsons LM, Harvey RP. Mesoderm-specific expression of the divergent homeobox gene HLX1 during murine embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 1996;205:457–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199604)205:4<457::AID-AJA9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hentsch B, Lyons I, Li R, et al. HLX1 homeo box gene is essential for an inductive tissue interaction that drives expansion of embryonic liver and gut. Genes Dev. 1996;10:70–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates MD, Wells JM, Venkatesh B. Comparative genomics of the HLX1 homeobox gene and protein: conservation of structure and expression from fish to mammals. Gene. 2005;352:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojas A, De Val S, Heidt AB, Xu SM, Bristow J, Black BL. Gata4 expression in lateral mesoderm is downstream of BMP4 and is activated directly by Forkhead and GATA transcription factors through a distal enhancer element. Development. 2005;132:3405–3417. doi: 10.1242/dev.01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkinson DG, Nieto MA. Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dandré F, Owens GK. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB and Ets-1 transcription factor negatively regulate transcription of multiple smooth muscle cell differentiation marker genes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2042–H2051. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00625.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solway J, Seltzer J, Samaha FF, et al. Structure and expression of a smooth muscle cell-specific gene, SM22 alpha. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13460–13469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du KL, Ip HS, Li J, et al. Myocardin is a critical serum response factor cofactor in the transcriptional program regulating smooth muscle cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2425–2437. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2425-2437.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng W-P, Zhao Q, Zhao X, et al. Up-regulation of Hlx in immature Th cells induces IFN-γ expression. J Immunol. 2004;172:114–122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bessa J, Gebelein B, Pichaud F, et al. Combinatorial control of Drosophila eye development by eyeless, homothorax, and teashirt. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2415–2427. doi: 10.1101/gad.1009002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebelein B, Culi J, Ryoo HD, et al. Specificity of Distalless repression and limb primordia development by abdominal Hox proteins. Dev Cell. 2002;3:487–498. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebelein B, McKay DJ, Mann RS. Direct integration of Hox and segmentation gene inputs during Drosophila development. Nature. 2004;431:653–659. doi: 10.1038/nature02946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reményi A, Scholer HR, Wilmanns M. Combinatorial control of gene expression. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:812–815. doi: 10.1038/nsmb820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen JD, Lints T, Jenkins NA, et al. Novel murine homeo box gene on chromosome 1 expressed in specific hematopoietic lineages and during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1991;5:509–520. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomczak KK, Marinescu VD, Ramoni MF, et al. Expression profiling and identification of novel genes involved in myogenic differentiation. FASEB J. 2004;18:403–405. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0568fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murthi P, Doherty V, Said J, Donath S, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Homeobox gene HLX1 expression is decreased in idiopathic human fetal growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:511–518. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajaraman G, Murthi P, Leo B, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B. Homeobox gene HLX1 is a regulator of colony stimulating factor-1 dependent trophoblast cell proliferation. Placenta. 2007;28:991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bates MD, Dunagan DT, Welch LC, Kaul A, Harvey RP. The Hlx homeobox transcription factor is required early in enteric nervous system development. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.You LR, Takamoto N, Yu CT, et al. Mouse lacking COUP-TFII as an animal model of Bochdalek-type congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16351–16356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507832102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufmann MH. Atlas of Mouse Development. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]