Introduction

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) hepatitis is a rare but frequently fulminant disease that presents with anicteric transaminitis, fever, leukopenia, and flu-like symptoms.1 It most frequently affects immunocompromised patients.2 We report a case of a patient with metastatic pheochromocytoma who presented with fever and elevated aminotransferases. HSV hepatitis was diagnosed after skin findings suggested cutaneous HSV.

Case

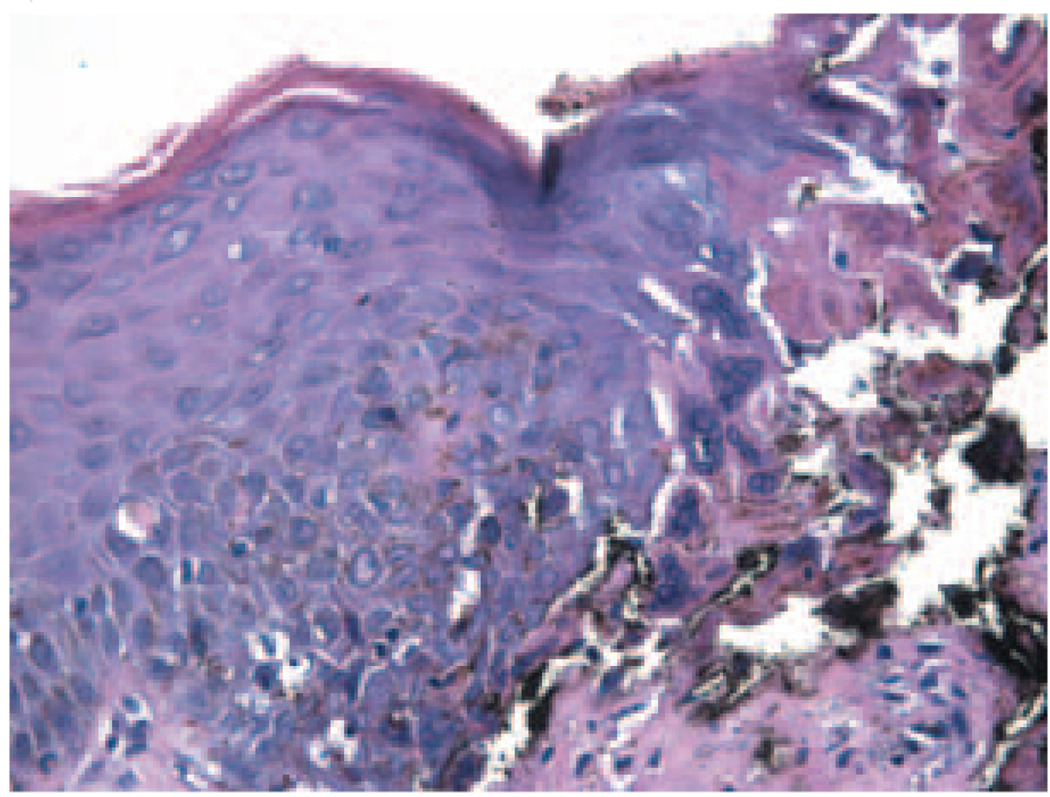

A 31-year-old man with metastatic pheochromocytoma presented with 6 days of fever shortly after the completion of chemotherapy. Prior to presentation, the patient reported 1 week of burning pain on urination and noted a sore at the urethral meatus. Despite normal urinalysis, the patient was treated with a course of antimicrobials for a urinary tract infection. The symptoms persisted, and he was admitted with a fever of 103 °F and leukopenia (white blood cell count of 3200/µL; absolute neutrophil count of 43 200/µL). The next day he developed transaminitis, which peaked at an aspartate aminotransferase level of 4850 U/L and alanine aminotransferase level of 3790 U/L. He had normal total bilirubin, and coagulopathy was noted. Viral studies, including hepatitis B and C, Epstein–Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus, were negative. Initially, the hepatitis was presumed to be related to transient ischemia in the setting of hypertension, fever, and chemotherapy; however, on day 3, the patient noted additional small erosions on the shaft of the penis (Fig. 1), and dermatology was consulted. The patient denied a prior history of genital or oral ulcers. Direct fluorescence antibody (DFA) and skin biopsy were performed. DFA showed HSV-1 and the patient was started on acyclovir. Skin biopsy showed ulceration and viral cytopathic changes consistent with HSV infection (Fig. 2), causing concern that the transaminitis may have been a result of disseminated HSV infection. Liver biopsy was deferred because of coagulopathy. One day after starting intravenous acyclovir therapy, the patient showed clinical improvement, and the normalization of his aminotransferase levels paralleled the resolution of his genital ulcerations. At the 1-month follow-up visit, liver function tests were normal.

Figure 1.

Photograph of multiple, punched-out erosions of the shaft of the penis

Figure 2.

Biopsy of one of the punched-out erosions reveals acantholysis and viral cytopathic changes, including molding of nuclei and multinucleated giant cells consistent with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection (hematoxylin and eosin, ×400)

Discussion

Disseminated HSV hepatitis is a rare complication of infection, with approximately 100 cases reported in the literature. Mucocutaneous lesions have been reported in less than one-half of cases of HSV hepatitis, and clinical symptoms may be nonspecific.2,3 The proposed mechanisms for hepatic involvement in both primary HSV and reactivation infection include a large inoculum of virus at the time of initial infection and impaired T-cell and macrophage immunity, producing dissemination of the HSV antigen. Strains of HSV may also exist that exhibit tropism for the liver.3,4 Untreated, patients frequently progress to fulminant liver failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and renal failure. Early intervention with acyclovir reduces mortality.5

When mucocutaneous lesions are present, as in our patient, skin biopsy may provide a definitive diagnosis. HSV DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction is also highly specific. In the absence of skin findings, liver biopsy may confirm the diagnosis, but is frequently impossible in the setting of severe coagulopathy. HSV serum serologies are often insensitive, even in advanced disease.3 Radiographic findings are nonspecific.2 HSV infection should be suspected in any immunocompromised patient presenting with fever, leukopenia, and elevated aminotransferases. In such patients, careful physical examination for skin findings should be performed, as the identification of cutaneous HSV with secondary dissemination may direct the early initiation of acyclovir therapy.

Acknowledgments

Ms Arkin, Dr Castelo, and Dr Kovarik had full access to all of the data in this vignette and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of analysis. Study concept: Ms Arkin, Dr Castelo, and Dr Kovarik. Acquisition of data: Ms Arkin and Dr Castelo. Analysis and interpretation of data: Ms Arkin, Dr Castelo, and Dr Kovarik. Drafting of manuscript: Ms Arkin and Dr Castelo. Critical revision of the manuscript: Dr Castelo and Dr Kovarik. Administrative and technical support: Dr Castelo. Study supervision: Dr Kovarik.

Footnotes

None of the authors have financial disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Sevilla J, Fernandez-Plaza S, Colmenero I, et al. Fatal hepatic failure secondary to acute herpes simplex virus infection. J Ped Hematol/Oncol. 2004;26:686–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortele K, Barish M, Yucel K. Fulminant herpes hepatitis in an immunocompromised pregnant woman: CT imaging features. Abdominal Imaging. 2004;29:682–684. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velasco M, Liamas E, Guijarro-Rojas M, et al. Fulminant herpes hepatitis in a healthy adult: a treatable disorder? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:386–389. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199906000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman B, Gandhi S, Louie E, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:334–338. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norvell J, Blei A, Jovanovic D, et al. Herpes simplex hepatitis: an analysis of the published literature and institutional cases. Liver Transplantation. 2007;13:1428–1434. doi: 10.1002/lt.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]