Sweet syndrome (SS) is a reactive neutrophilic process characterized by tender, erythematous papules and plaques, fever, and leukocytosis and is associated with underlying infections, inflammatory diseases, and malignant neoplasms. To our knowledge, only 2 cases of SS associated with new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have been reported—one in an adult woman and the other in a 14-year-old girl.1,2 We report the first case in an adult man.

Report of a Case

A 25-year-old previously healthy man was admitted for intermittent fevers (temperature readings to 39.4°C), arthralgias, chest pain, and eruption. He reported 7 months of malaise and a previous admission for chest pain during which a chest computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. A dermatologist was consulted to evaluate a malar eruption and multiple, red, tender plaques with central vesiculopustules (Figure 1). The patient denied taking any new medications prior to the onset of his eruption.

Figure 1.

Photograph of 1 tender erythematous plaque with a central pustule located on the anterior thigh.

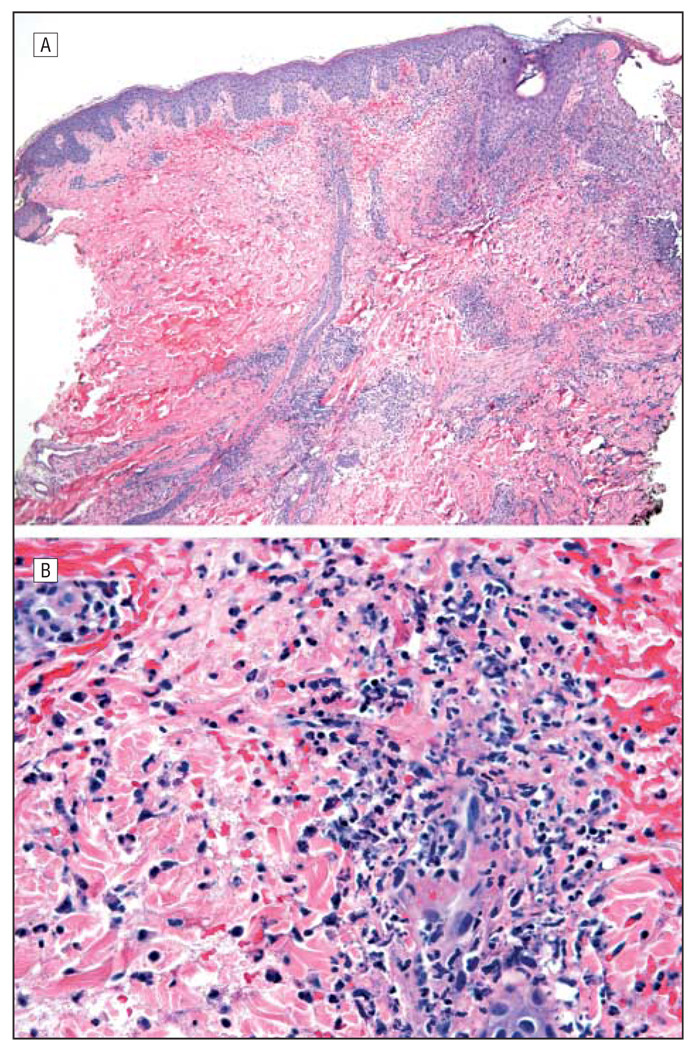

Initial blood testing showed leukopenia with neutrophilia and lymphopenia, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level, and negative findings for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human immunodeficiency virus. A biopsy specimen of 1 of the tender skin lesions demonstrated a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of infection (Figure 2). Urinalysis showed proteinuria. Results of testing for the following antibodies were positive: antinuclear (titer, 1:5120; pattern, speckled), anti–double-stranded DNA (5200 IU/mL), anti-Smith, antiscleroderma-70, antiribonucleoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic (serine PR-3 antibody, 26 U). A CT scan of the chest and an electrocardiogram confirmed pericarditis as the cause of chest pain. A lymph node biopsy specimen showed reactive hyperplasia with no evidence of malignant neoplasm. Together, these results and the patient’s symptoms suggested a diagnosis of both SLE and SS.

Figure 2.

Histopathologic images from our case. A, Low-power hematoxylin-eosin–stained specimen of a skin lesion showing peripheral epidermal blister formation and a dense dermal infiltrate with leukocytoclasia but no evidence of vasculitis (original magnification ×40). B, High-power hematoxylin-eosin–stained specimen reveals an infiltrate composed largely of neutrophils (original magnification ×400). Findings under Gram, Grocott, and acid-fast bacilli stains were all negative.

Comment

To our knowledge, Hou et al1 reported the first case of SS in association with new-onset SLE in 2005. Seven other reports show SS in association with drug-induced lupus (n=3), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (n=1), and pediatric lupus (n=3).2,3 The association of SS and SLE is rare. Sweet syndrome and SLE individually are uncommon in men: SS occurs 4 times more frequently in women than in men, and 90% of patients with lupus are women.4,5 Our patient manifested both major and all 4 minor criteria for SS and 7 of the 11 criteria for SLE (malar eruption, arthritis, persistent proteinuria, leucopenia, and positive findings for anti–double-stranded DNA, antinuclear, and anti-Smith antibodies).6

After initial treatment with systemic prednisone, our patient’s lesions and symptoms improved. Two months after diagnosis, his condition was stable under treatment with prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil. The present report of an adult man with concurrent SS and new-onset SLE reminds clinicians that this phenomenon, albeit rare, should always be considered, given suggestive clinical and laboratory signs and symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant NIH K24-AR 02207 (Dr Werth).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

References

- 1.Hou TY, Chang DM, Gao HW, Chen CH, Chen HC, Lai JH. Sweet’s syndrome as an initial presentation in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature. Lupus. 2005;14(5):399–402. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2083cr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnham JM, Cron RQ. Sweet syndrome as an initial presentation in a child with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2005;14(12):974–975. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2236xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camarillo D, McCalmont TH, Frieden IJ, Gilliam AE. Two pediatric cases of nonbullous histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatitis presenting as a cutaneous manifestation of lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(11):1495–1498. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.11.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20(3):409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):929–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37(3):167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]