Abstract

This study investigated the effects of the peer social context and child characteristics on the growth of authority-acceptance behavior problems across first, second, and third grades, using data from the normative sample of the Fast Track Project. Three hundred sixty-eight European American and African American boys and girls (51% male; 46% African American) and their classmates were assessed in each grade by teacher ratings on the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation–Revised. Children’s growth in authority-acceptance behavior problems across time was partially attributable to the level of disruptive behavior in the class-room peer context into which they were placed. Peer-context influence, however, were strongest among same-gender peers. Findings held for both boys and girls, both European Americans and African Americans, and nondeviant, marginally deviant, and highly deviant children. Findings suggest that children learn and follow behavioral norms from their same-gender peers within the classroom.

Growth in antisocial behavior problems during middle childhood frequently augurs a future of low academic performance and extensive experience with the disciplinary structure of the school (Farmer, Bierman, & CPPRG, 2002; Sinclair, Pettit, Harrist, Dodge, & Bates, 1994). By the time students reach middle school and high school, low academic performance and experience with the disciplinary system can lead to a myriad of more serious problems, including dropping out, delinquency, depression, and other antisocial behavior (Ialongo, Vaden-Kiernan, & Kellam, 1998; Ensminger & Slusarcick, 1992). Although individual differences in antisocial behavior patterns are quite stable from early life onward (Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006), not all early disruptive children grow into seriously delinquent adolescents: life experiences and contexts exert an impact on the trajectory of development for at least some students (Dodge et al., 2006).

The current study addresses the influence of the school social context (that is, directly measured peer behavioral norms) on change in student misbehavior across time, specifically how placement of young students into classrooms that very in peer social norms might either increase of decrease their misbehavior across development. Uniquely, this study also attempts to disentangle the mechanism at work, contrasting whether children are learning norms of deviance from their same-gender peers versus other-gender peers or both from male versus female peers or both. In other words, we consider whether girls are equally influenced by their female peers’ norms of deviance and their male peers’ norms of deviance and whether boys are equally influenced by female and male peers’ norms of deviance. Furthermore, because not all students respond to a particular context in the same manner (Dodge et al., 2006), we also investigate which types of students (varying in deviant behavior) are most susceptible to the influence of peer context. We tested hypotheses regarding whether children’s deviant behavior changes as the result of the sociocultural context in which children live, their individual dispositions, and the interaction of these factors. In other work, this perspective has been termed a “transactional developmental model” (Dodge & Pettit, 2003).

The Influence of the Peer Social Context on Behavior Problems

Despite the fact that children spend a great deal of time in their elementary school classrooms, research on causes of conduct problems has, until recently, focused more intensively on family structure, parenting styles, and the broader ecology of poverty as causes of antisocial behavior (e.g., Vaden-Kiernan, Ialongo, Pearson, & Kellam, 1995; Pearson, Ialongo, Hunter, & Kellam, 1994). More recently, a body of research examining the influence of school peer context on the growth of conduct problems in early and middle childhood has begun to emerge (Aber, Brown, & Jones, 2003; CPPRG, 1999; Thomas, Bierman, & CPPRG 2006; Henry Guerra, Huesmann, Tolan, VanAcker, & Eron, 2000). Most relevant to the current study is the research concerning the influence of peers on delinquency and behavior problems, research that is relatively well developed with regard to adolescent delinquency (for a review, see Gifford-Smith, Dodge, Dishion, & McCord, 2005). This literature finds evidence for both self-selection of antisocial youths into antisocial peers groups (called homophily) and adverse influence of affiliation with antisocial peers on one’s own antisocial behavior (Thornberry, Krohn, Lizotte, Smith, & Tobin, 2003). For example, among sixth-through eighth-grade students, exposure to higher levels of fighting and bullying within a child’s peer group at Time 1 predicted increased fighting and bullying by that child at Time 2 in sixth-through eighth-grade students, after controlling for individual aggression at Time 1 (Espelage, Holt, & Henkel, 2003). Adolescents who affiliate with deviant peers are at risk for increases in multiple problem behaviors, including substance use, risky sexual behavior, arrest, and violence (Dishion, Eddy, Haas, Li, & Spracklen, 1997; Gifford-Smith et al., 2005).

The Literature is less well developed as it applies to peer effects on the growth and development of behavior problems among elementary school–aged children. Evidence of peer contextual effects among elementary school–aged children had begun to emerge, however, in contrived play groups, natural settings and intervention studies. Observational studies of contrived play groups have demonstrated dyadic- and group-level influences on the emergence and maintenance of aggression in those play groups, such that future aggression is more common in peer groups that are characterized by high levels of negative affect, conflict, dislike, activity level, and competition (DeRosier, Cillessen, Coie, & Dodge, 1994; Dodge, Price, Coie, & Christopoulos, 1990).

In more natural settings, peers have been observed to increase externalizing behavior during free play and classroom interaction. Among low-risk kindergarten boys and girls, exposure to externalizing-problem peers increased externalizing behavior among girls but not boys, independently of self-selection effects (Hanish, Martin, Fabes, Leonard, & Herzog, 2005). Barth, Dunlap, Dane, Lochman, and Wells (2004) found that among older elementary students (fourth and fifth graders), concurrent classroom levels of peer aggressive behavior were correlated with an individual child’s level of aggression. These effects also occurred longitudinally. Using the same schools but not the same sample as the present study, Thomas, Bierman, and CPPRG (2006) established that cumulative exposure to peer aggression across three years predicted a child’s level of aggression in third grade, statistically controlling for previous aggression. Using an even longer observation period, Kellam and his coauthors (1998) discovered that those highly aggressive first grades who had been randomly assigned to class-rooms with elevated levels of aggression were at heightened risk of becoming even more highly aggressive in middle school. This was particularly true for boys.

Intervention studies, in which elementary school–aged children are brought together in newly formed groups, also provides evidence of peer-context influences. Aggressive third graders who have been randomly assigned to peer groups populated by even more aggressive peers increase their aggressive behavior across time. On the other hand, aggressive third graders who have been assigned to peer groups with relatively less aggressive peers decline in their aggressive behavior across time (Boxer, Guerra, Huesmann, & Morales, 2005).

The findings among elementary school children are not uniformly consistent with a peer-context influence hypothesis, however, Using a sample of children at various ages throughout elementary school, Henry et at, (2000) discovered that classroom norms about what should be directly influenced children’s aggressive behavior, but the level of actual misbehavior in the classroom (what is) did not have an influence on individual children’s aggressive behavior across time. The body of findings suggests that child characteristics (e.g., gender and initial level of aggressive behavior) might moderate the effects of exposure to deviant peer contexts. Resolution of this ambiguity inspired the current study. Furthermore, the question of which peers are important, or whether peers’ norms are more influential if the peers match the gender of the child in question, remains to be resolved.

Mechanisms of Influence

Underlying the work on delinquency and conduct problems is the question of how peers in a classroom context might have an effect on an individual’s behavior. Theories have focused on the impact of primary group socialization wherein children learn norms through the primary groups of which they are members. Thus, children learn behaviors through imitating their peers and receiving reinforcement for various behaviors from those peers. When applied to adolescents, this process is known as deviancy training wherein aggressive teens grouped together with other aggressive teens reinforce aggressive behavior among their peers (Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews, & Patterson, 1996). In other words, groups of aggressive teens develop norms that support rule breaking, whereas more mixed groups of teens develop prosocial norms instead. Deviancy training is linking to a variety of maladaptive outcomes, including increases in adolescent substance and violence (Dishion, Capaldi, Spracklen, & Li, 1995; Dishion, Eddy, Haas, & Spracklen, 1997).

Until recently, the deviancy training hypothesis had not been tested among younger children. There is some evidence from a recent study that peer influences might contribute to the development and growth of behavior problems among children as young as age 6 (Snyder, schrepferman, Oeser, Patterson, Stoolmiller, Johnson, & Snyder, 2005). Pairing students with randomly selected classroom peers, Snyder et al. (2005) observed increases in behaviors such as lying and stealing when children were paired with peers who had previously exhibited these behaviors. The authors concluded that a deviancy training model, in which peer influences result in higher levels of behavior problems, explains some of the development of behavior problems among very young children.

Yet other research calls into question how easily the deviancy training model may apply to young children. An extensive body of research, beginning with Coie and Dodge (1983), has established that young children who display aggressive, withdrawn, and inattentive-hyperactive behaviors are likely to become rejected by their peers (Coie & Kupersmidt, 1983; Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990; Dodge, 1983). If children displaying antisocial behaviors are rejected by their peers, it follows that peers would avoid displaying antisocial behaviors in order to avoid rejection. Thus, it is not obvious that children exposed to peers with high mean levels of conduct problems would increase their own conduct problems.

When we consider the context in which these children are exposed to and exhibit conduct problems, however, the mechanism through which aggressive peers might affect, their elementary school-aged counterparts becomes a bit clearer. Peer’s responses to a child’s aggressive behavior depend, in part, on the peer group norm for aggression (Wright, Giammarino, & Parad, 1986). In peer groups where aggression is relatively normative, peers’ liking and disliking responses to aggression are less negative. It is speculated from this work (but untested) that peer cultures in which aggression is common foster further growth in aggressive behavior by failing to respond negatively to it.

Following from Wright et al. (1986), Stormshak, Bierman, Bruschi, Dodge, Coie, & CPPRG (1999) examined the impact of a child’s behavior on peer sociometric preferences. They hypothesized that some antisocial behaviors adversely influence peer rankings regardless of context (a social skill deficit model), whereas the influence of other behaviors is contextually dependent (a person-group similarity model). Their findings supported their hypotheses: aggressive children in highly aggressive contexts are not penalized as much in terms of lower peer preference as those aggressive children in contexts with low mean levels of aggressiveness, supporting a person-group similarity model. Stormshak et al.’s findings suggest that classrooms dominated by peers who display aggressive behavior might well encourage increased aggressive behavior in a in a child through deviancy training.

Futhermore, a deviancy training model, as an instantiation of broader social learning theory, posits that not all peer groups will exert equal influence on a child’s behavior; rather, a child is most likely to be influenced by a peer group that is similar to or valued by the child (Dishion, Poulin, & Burraston, 2001). Gender is a highly salient grouping and influence factor for early elementary school–aged children (Maccoby, 2004), and interaction with boys and girls, as Martin and Fabes (2001) have found through direct observation. Thus, a deviancy training model leads to the hypothesis that an elementary school child’s behavior would be influenced by same-gender peer group norms to greater degree than by opposite-gender norms.

We consider, however, an alternate hypothesis about how peer group behavioral norms might exert influence in classrooms, as suggested by Cook and Ludwig (2006). They posit that if a large number of peers are misbehaving (without regard to the gender of those peers), the teacher’s attention must be directed toward management of those children, thus limiting her or his ability to control the behavior of the remaining children. The result could be chaos and increased disruptive behavior by any given child, not because of deviancy training but because of inadequate behavior management by the teacher.

The current study attempted to disentangle the same-gender deviancy training model and the teacher-management model by examining within-gender and opposite-gender influences. Both models suggest that same-gender peer group norms will influence a child’s behavior, but the two models differ with regard to opposite-gender influences: a deviancy training model posits that influences occur primarily within gender, whereas a teacher-management model suggests that deviant behavioral norms among any group of peers, including opposite-gender peer groups, will distract a teacher and thus increase authority-acceptance problems in a child. Furthermore, the same-gender and cross-gender groupings also provide insight into the mechanisms of a peer-deviance effect. If the effect is entirely caused by a teacher’s distraction away from a particular child due to attention to behavior-management problems among other students, then the magnitude of effect should be similar for same-gender and opposite-gender peer deviance. If, in contrast, the effect is due to direct influence by peers with whom a student interacts, then the effect should be stronger for same-gender deviance than opposite-gender deviance, at least in this sample of first-through third-grade children who are well known to be gender-segregated in their interaction patterns (Maccoby, 2004). These models were contrasted in the current study.

The same-gender and opposite-gender comparisons also address the possibility that teacher bias in ratings could account for findings: children may be seen to increase their authority-acceptance problem scores while in a given classroom, but the effect may be due to a teacher’s propensity to rate all students as high (or low) in authority-acceptance problems. If students’ scores are affected by same-gender deviance but not opposite-gender deviance, then the observed effect is less likely to be attributable to a biased teacher-rating propensity. For instance, if a given teacher has a tendency to rate all students as high on authority-acceptance problems, then we will see that both same-gender and opposite-gender peers have an effect on a given student’s own authority-acceptance problems. The teacher-management model and a teacher rating-bias model posit similar effects; if, however, a deviancy training model holds and children are more influenced by same-gender peers, then we will not see an effect of influence by opposite-gender peer norms.

Effects of Child’s Previous Level of Aggression

Given that Kellam et al. (1998) found that peer context had a particularly strong impact on deviant children, we also considered this possibility. In their work, however, they considered only deviant and nondeviant children. Recent findings with adolescent children have suggested that a group in between those extreme groups—that is, marginally deviant children—might be more plastic and susceptible to influence than children who have firmly established patterns of aggression or nonaggression (Caprara, Dodge, Pastorelli, Zelli, & CPPRG, 2006). Therefore, we hypothesized that marginally deviant children will be more susceptible to peer-group norms (especially same-gender peer-group norms) than will highly deviant or nondeviant children.

It is also plausible that children’s previous level of aggression will exert a selection effect that will operate on children’s entry into particular kinds of classrooms. The literature is growing on children’s self-selection into peer social groups (Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2006), but it is also possible that school institutional forces operate to bring together aggressive problem children within the same classrooms through tracking, special education scheduling constraints, assignment to teachers with special expertise in managing problem behavior, or other unknown mechanisms. We tested for selection effects and controlled the child’s previous level of aggression in analyses.

Summary of Hypotheses

Given our theoretical perspective and earlier research on the sociocultural influences on conduct problems, we hypothesized that children in classrooms with relatively high levels of authority-acceptance problems will increase their own levels of authority-acceptance problems.

We further hypothesized that the same-gender level of authority-acceptance problems will influence children’s own level of authority-acceptance problems to a much greater extent than will the other-gender level of authority-acceptance problems. In other words, children will learn norms of deviance and conformity from their peers, and more specifically their same-gender peers, and will adjust their own behavior according to the prevailing behavioral norm of the classroom among their same-gender peers.

We also hypothesized that marginally deviant students will be most susceptible to peer-group influences, more so than students who have displayed a great many or very few authority-acceptance problems. Given prior literature on the effects of peer-group influences, we also tested whether these influences are felt uniformly among boys and girls and European American and African American students. Finally, we hypothesized that a child’s previous level of aggression will exert a selection effect on the types of classrooms into which they are placed.

Methods

Participants

Participants were the normative sample of children in the nontreated control schools of the Fast Track project (CPPRG, 1992), a multisite efficacy trial of an intervention designed to prevent early-onset conduct disorder problems (see www.fasttrackproject.org). Participants resided in four geographically diverse regions of the United States; Durham, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; Seattle, Washington; and rural Central Pennsylvania. Within each site, schools that served high proportions of low-income and disadvantaged students were identified for participation. The 54 participating schools were placed into one or two matched sets of schools within each site, and then within each set one group was assigned randomly to serve as intervention, while the other served as controls. Only control schools (n = 27) were used in identifying the normative sample so that intervention could not alter outcomes.

To select the Fast Track normative sample, kindergarten teachers rated the aggressive-disruptive behaviors of each of the children in their classrooms, using the 10-item Authority Acceptance scale of the Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation–Revised (Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991). Approximately 100 children at each site were randomly selected for the normative sample, stratified to represent the population according to race, gender, and distribution of behavior problems. The current sample includes only the African American and European American children in the normative sample who remained at their original school for more that one year (n = 368). In the analyses that follow, sample sized were reduced due to missing data on the respondents and on their classmates. We follow the normative sample of first graders through the end of their third-grade year.

The Social Health Profile Measures

In the spring of first, second, and third grades, the current teacher completed an interview that included ratings for each student in the classroom (both the normative sample participants and all peers) on a 10-item measure of authority-acceptance problem items, selected from the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation–Revised (Werthamer-Larsson et al., 1991: CPPRG, 1995). Using the 10-item authority-acceptance scale (Werthamer-Larsson et al., 1991), the teacher assessed how well each of the following 10 descriptor items characterized the child: takes property, yells at others, lies, breaks things, harms others, is disobedient, breaks rules, teases classmates, fights, and is stubborn. Responses were coded on a 6-point scale, ranging from “almost never” to “almost always.”

The measure is scored such that the higher the authority-acceptance problems score, the more deviant is the child. Cronbach’s alphas for the authority-acceptance scores for first, second, and third grades are 0.95, 0.93, and 0.93, respectively. This measure of authority-acceptance problems is a single scale that has been used in multiple intervention and descriptive studies (e.g., CPPRG, 1999). In the normative sample, 361 of 368 children had complete scores on the authority-acceptance scale in the first grade and 340 had valid scores in the second grade, for a listwise deletion total of 336 students. For the analysis of third grades, 323 students had valid third-grade authority-acceptance scores; after listwise deletion with the 340 who had valid scores in the second grade, there were 308 valid scores.

In order to examine whether the classroom context had a particularly strong effect for children at various levels of deviance, for some analyses children were grouped according to their own authority-acceptance problem scores. Children scoring below the sample mean for that year were considered nondeviant; those scoring between the mean and one standard deviation above the mean were termed marginally deviant; and those scoring greater that one standard deviation above the mean were deviant. The classroomwide score, rather than the within-gender score, was used to determine a child’s level of deviance because classrooms had too few same-gender peers to identify marginally deviant children, within gender, reliably. Other independent variables included students’ gender, ethnicity (African American or European American), and their previous year’s scores on the authority-acceptance scale.

Data were also collected on the normative sample member’s peers in the classroom. In the first, second, and third grades, teachers completed the authority-acceptance problems measure for all of the Fast Track normative sample participants as well as their classmates. Information of the classmates was limited to their race, gender, and scores on the authority-acceptance problems scale. A mean score for the authority-acceptance scale for all same-gender peers as the participant (minus the participant’s score) and a mean score for the authority-acceptance scale for all opposite-gender peers were also computed for each classroom. In cased for which fewer than five scores were available to compute the mean (e.g., a classroom that had fewer than five opposite-gender peer scores). no score was computed, and data were treated as missing.

The sample size is reduced due to small peer group sized in the classroom. As mentioned above, mean scores were not computed for classrooms with fewer that five same-gender or five opposite-gender scores. This data deletion results in final sample sized of 248 for the analysis of second-grade authority-acceptance problems and 178 for third-grade authority-acceptance problems. Comparison of the deleted cases with the samples used in our two analyses reveals that our samples have slightly lower authority-acceptance problem scores in the first and second grades but not in the grade and are more likely to be female. The differences in authority-acceptance problem scores should bias our results in a conservative direction, but we must be cautious in interpreting the results for student’s gender, given our relative overrepresentation of girls.

Finally, in separate analyses for whether the classroom context has a particularly strong effect on certain types of children, classroomwide mean scores (minus the participant’s score) were computed for those classrooms with than four participants; classrooms were categorized into three groups, with the lowest-problem classrooms being the bottom third of the distribution, the moderate-problem classrooms being the middle third of the distribution, and the highest-problem classrooms being the top third of the distribution.

Results

Table 1 shows means, standard deviation, and bivariate correlations among variable. In this table, same-gender means indicated the classroom mean on authority-acceptance problems for classmates of the same gender as the normative sample respondent, while opposite-gender means indicate the classroom mean on authority-acceptance problems for classmates of the opposite gender. Individual differences in authority-acceptance problems were quite stable across grade levels (r = .63 and 62, p < .001, for first to second grades and second to third grades, respectively) and predictable from being male and African American. Individual second-grade authority-acceptance problems were significantly correlated with a child’s second-grade sane-gender classroom peer group mean score but not with opposite-gender scores. Individual third-grade authority-acceptance problems were significantly correlated with a child’s third-grade same-gender and opposite-gender classroom peer group mean scores.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics and Bivariate Correlations among Variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Individual authority acceptance Grade 1 | 1.20 | 1.14 | – | ||||||||

| 2. Individual authority acceptance Grade 2 | 1.21 | 1.03 | .63*** | – | |||||||

| 3. Individual authority acceptance Grade 3 | 1.19 | 1.08 | .64*** | .62*** | – | ||||||

| 4. Same-gender class mean Auth acceptance–Grade 2 | 1.08 | 0.55 | .29*** | .41*** | .27*** | – | |||||

| 5. Opposite-gender class mean Auth acceptance–Grade 2 | 1.20 | 0.60 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.01 | .26*** | – | ||||

| 6. Same-gender class mean Auth acceptance–Grade 3 | 1.20 | 0.66 | .35*** | .25*** | .40*** | .43*** | −0.04 | – | |||

| 7. Opposite-gender class mean Auth acceptance–Grade 3 | 1.10 | 0.67 | .21** | .14* | .21*** | .13*** | .41*** | .21** | – | ||

| 8. Gender (0 = female, 1 = male) | 0.51 | 0.50 | .29*** | .26*** | .29*** | .39*** | −.49*** | .39*** | −.38*** | – | |

| 9. Ethnicity (0 = Caucasion, 1 = African American) | 0.46 | 0.50 | .31*** | .29*** | .30*** | .35*** | .18** | .13* | .22*** | 0.04 | – |

N’s range from 368 for gender and ethnicity to 219 for third classroom means.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Analytic Strategy

Most hypotheses were tested by contrasting ordinary least squares regression models, conducted in two independent sets (one for peer gender effects for second grade and one for peer gender effects for third grade). Due to the clustering of the observations within classrooms, we employed a Huber-White sandwich estimator of variance and cluster adjustment in Stata to adjust for the correlation of the respondents. Consideration was given to conducting hierarchical linear models with participants nested within classrooms, but sample size limitations precluded this possibility. Overall, the average class size is 20, which includes both normative sample members and their classmates. The reader will recall that the analysis of growth in authority-acceptance problems is only conducted for normative sample members: their nonnormative sample classmates’ authority-acceptance problems were only used to provide a measure of the classroom context in which the normative sample members are situated. For the analyses of second graders, the median in-classroom normative sample size is 3, and approximately 74% of the respondents come from classrooms that have fewer than 5 students from the normative sample. For the analysis of third graders, our median in-classroom normative sample size is 2, and 82% come from classrooms that have fewer than 5 fewer than 5 normative sample students. The average number of normative sample participants per classroom was too small to complete this hierarchical linear analysis.

In the first regression model in each set, a participant’s authority-acceptance problem scores were modeled for grade X as a function of that participant’s authority-acceptance score in grade X-1, the participant’s gender (female = 0 and male =1), and participant’s ethnicity (European American = 0 and African American = 1). In the second model the continuous same-gender and opposite-gender classroom mean authority-acceptance scores were added in order to test the incremental prediction afforded by the peer context. Initial models also included the site of data collection as a control variable as well as interactions among the independent variables, but including these variables did not change the results. Therefore, we have excluded these variables in the interest of parsimony.

Tests of Influence of Peer Gender Context

Grade 2

A series of model-contrasting regression analyses, summarized in Table 2, indicated that second-grade authority-acceptance problems were significantly predicted from first-grade authority-acceptance problems, being African American, and being male. Controlling for those factors, features of the second-grade peer context significantly incremented the prediction: the mean of second-grade same-gender peer authority-acceptance problems significantly predicted a child’s own authority-acceptance problems score in second grade (β = .46, p < .001). The mean of opposite-gender peer authority-acceptance problems did not predict a child’s own score. The full model accounted for 47.8% of the total variance in second-grade authority-acceptance problem scores (F[5.76] = 26.55, p < .001).

Table 2.

Regressions on Second Grade Authority Acceptance, with Huber-White Sandwich Estimators of Variance and Cluster Correction

| β | β | β | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 authority acceptance | 0.51(.07)*** | 0.48(.07)*** | ||

| African American | 0.32(.14)* | 0.18(.14) | ||

| Male | 0.20(.10)* | 0.10(.14) | ||

| Same-gender classroom mean | 0.46(0.13)** | |||

| Different-gender classroom mean | 0.12(.11) | |||

| R2 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| F | 22.17*** | 26.55*** | 22.19*** | 13.81*** |

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Grade 3

Similar model-contrasting regression analyses predicting third-grade scores are summarized in Table 3. Controlling for authority-acceptance problems in second grade, ethnicity, and gender, the mean of second-grade same-gender peer authority-acceptance problems significantly predicted a child’s own authority-acceptance problems score in third grade (β = .41, p < .01). The full model accounted for 54.9% of the total variance in third-grade authority-acceptance problems scores (F[5, 60] = 30.99, p < .001).

Table 3.

Regressions on Third-Grade Authority Acceptance, with Huber-White Sandwich Estimators of Variance and Cluster Correction

| β | β | β | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 2 authority acceptance | 0.63(.07)*** | 0.57(.07)*** | ||

| African American | 0.11(.14) | 0.04(.15) | ||

| Male | 0.45(.11)*** | 0.37(.12)** | ||

| Same-gender classroom mean | 0.41(.19)** | |||

| Different-gender classroom mean | 0.11(.10) | |||

| R2 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| F | 41.93*** | 30.99*** | 18.30*** | 12.01*** |

| N | 178 | 178 | 178 | 178 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

First to second to third grades

Finally, a model predicting third-grade authority-acceptance scores is shown in Table 4. Controlling for authority acceptance problems in first grade, ethnicity, and gender yielded a marginally significant effect of second-grade same-gender peer authority-accept-acceptance problems (β = .33, p < .07) but not opposite-gender problems (β = −.10, ns). This finding suggests that the second-grade same-gender peer group exerts a marginally significant effect on a child’s growth in authority-acceptance problems that lasts through the spring of third grade, when a completely different teacher is rating the child.

Table 4.

Regressions on Third-Grade Authority Acceptance, Using Second-Grade Classroom Mean, with Huber-White Sandwich Estimators of Variance and Cluster Correction

| β | |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 authority acceptance | 0.59(.09)*** |

| African American | 0.14(.17) |

| Male | 0.19(.15) |

| Same-gender classroom mean—grade 2 | 0.33(.17)* |

| Different-gender classroom mean—grade 2 | 0.10(.13) |

| R2 | 0.48 |

| F | 16.64*** |

| N | 178 |

p < .10;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Tests of Individual Susceptibility to Peer Context Influence

To test the hypotheses that particular subgroups of children would be more susceptible to peer-group influences than other subgroups, an analysis of variance with Type III sums of squares was conducted, with second-grade authority-acceptance problem scores as the dependent variable; factors were the child’s first-grade behavioral categorization (as nondeviant, marginally deviant, or deviant), the second-grade classroom type (as lowest-problem, moderate-problem, or highest-problem classroom), gender, and ethnicity. All interactions were tested.

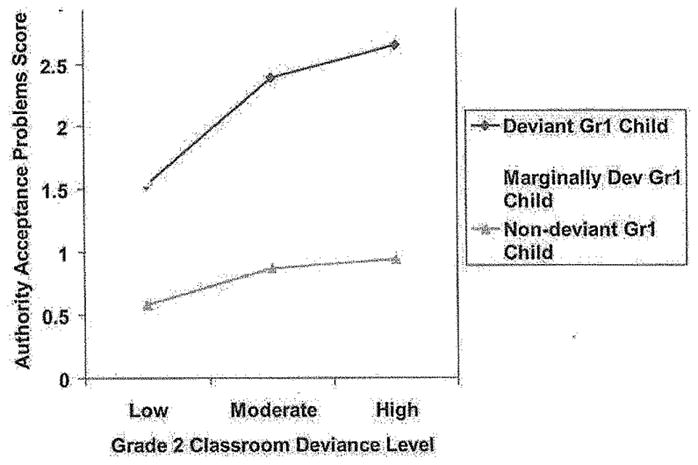

The analysis revealed significant main effects for the child’s first-grade behavioral classification (F[2,237] = 32.14, p < .001) and second-grade classroom type (F[2,237] = 4.20, p < .02). These two main effects are depicted in Figure 1, which shows that as the classroom peer-problem level increased so did the child’s authority-acceptance problem score and that this effect held for nondeviant, marginally deviant, and deviant kinds of children. Partial correlation coefficients between the second-grade authority-acceptance score for a child and the mean authority-acceptance score for all second-grade classroom peers, controlling for first-grade authority-acceptance scores, were .26 for the deviant group of children, .10 for the marginally deviant group, and .22 for the nondeviant group. The lines in Figure 1 must be interpreted as parallel. All of these correlations are positive, and they do not differ significantly from each other. No other main effects or interaction effects were significant. The lack of any significant interaction effect with second-grade classroom type indicates that no subgroup of children (including first-grade behavioral type, gender, and ethnicity) was more influenced by classroom peer’s behavior than any other subgroup.

Figure 1.

Grade 2 authority-acceptance problems mean score as a function of Grade 1 authority-acceptance problem level and Grade 2 classroom deviance level.

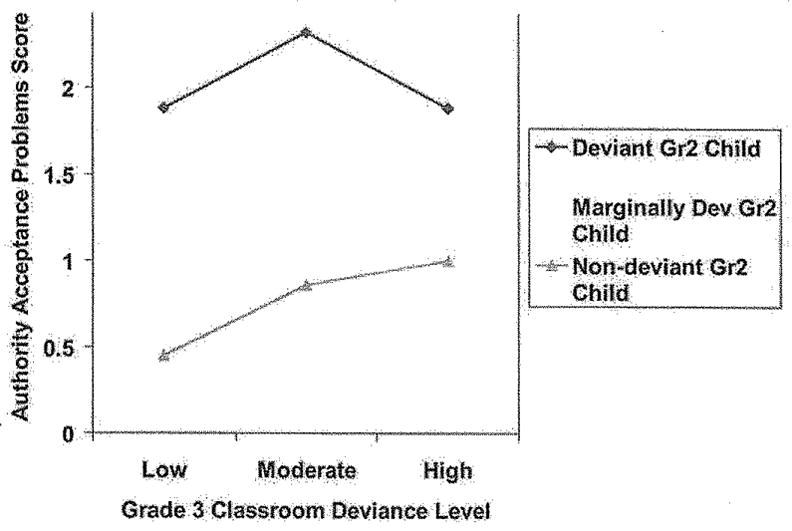

The analysis of variance was repeated with third-grade authority-acceptance problems score as the dependent variable; factors were the child’s second-grade behavioral categorization and the third-grade classroom type, gender, and ethnicity. Again, significant main effects were found for the child’s second-grade behavioral classification (F[2,206] = 22.04, p < .001) and third-grade classroom type (F[2,206] = 3.45, p < .05). These two main effects are depicted in Figure 2, which shows that as the classroom peer-problem level increased so did the child’s authority-acceptance problem score and that this effect held for nondeviant, marginally deviant, and deviant kinds of children. Partial correlation coefficients between the third-grade authority-acceptance score for a child and the mean authority-acceptance score for all third-grade classroom peers, controlling for second-grade authority-acceptance scores, were .19 for the deviant group of children, .32 for the marginally deviant group, and .29 for the nondeviant group. All of these correlations are positive, and they do not differ significantly from each other. The lines in Figure 2 must be interpreted as parallel. Main effects were also found for ethnicity (F[1,206] = 9.88, p < .01) and gender (F[1,206] = 8.41, p < .01), indicating higher behavior-problem scores for African American than European American children and for males than females. No interaction effects were significant, indicating that no subgroup of children was more influenced by classroom peer’s behavior than any other subgroup.

Figure 2.

Grade 3 authority-acceptance problems mean score as a function of Grade 2 authority-acceptance problem level and Grade 3 classroom deviance level.

Selection-into-Classroom Effects

Finally, to test whether children of differing levels of behavioral deviance in one grade either self-selected or were placed into classrooms of differing levels of deviance in the next grade, analyses of variance were conducted with the individual child’s grade-X deviance category (nondeviant, marginally deviant, or deviant), gender, and ethnicity as factors and the classroom mean’s authority-acceptance score at grade x + 1 as the dependent variable. For second-grade analyses, the effect of first-grade deviance category was not significant (F[2,264] = 1.92, ns). The first-grade nondeviant, marginally deviant, and deviant groups were placed into second-grade classrooms with mean authority-acceptance scores of 1.05, 1.19, and 1.15, respectively, which did not differ significantly. For third-grade analyses, the effect of second-grade deviance category was significant (F[2,230] = 4.71, p < .01). The second-grade nondeviant, marginally deviant, and deviant groups were placed into third-grade classrooms with mean authority-acceptance scores of 1.06, 1.36, and 1.32, respectively. These means and cell contrasts (p < .05) indicated that second-grade nondeviant children were placed into third-grade classrooms with significantly lower average authority-acceptance problems scores than were the marginally deviant and deviant children, which did not differ. Note that the prior analyses of peer-group influences control for the child’s initial level of deviance and thus are not biased by this selection effect.

Discussion

This study tested several hypotheses regarding the growth of authority-acceptance problems among early elementary school—aged children. The major finding of this study upheld our first hypothesis, which stated that children’s behavior-problem scores are influenced by the classroom context into which they are placed. The second hypothesis predicted that influence would be greater for same-gender peers than for other-gender peers, and again we find this to be the case. Specifically, children appear to have their trajectories of authority-acceptance problems influenced by the deviant behavioral norms of their same-gender peers in the elementary school classroom. These results held for boys and girls and for African American and European American students. Drawing from literature on the growth of behavior problems among adolescents (Caprara et al., 2006), we also hypothesized that children with mild levels of deviance—the marginally deviant—would be particularly susceptible to the classroom peer context. We did not find support for this hypothesis. Finally, we tested whether there was a tendency for children with high levels of deviance in one year to be assigned to very deviant classrooms in the following school year. We found mixed support for this hypothesis.Below we expand on these results and discuss their implications.

Controlling for and regardless of their deviance scores the previous year, we found that children who are placed into classrooms with high levels of deviance among their same-gender peers receive higher scores themselves. Together with the work of Snyder et al. (2005), who found increases in behaviors such as lying and stealing among children who spent time with deviant peers, our results lend additional evidence to the applicability of the deviancy training model to the process of behavior problem growth and development among young children. This peer deviance influence effect is evident for same-gender peers but not for opposite-gender peers. The findings are consistent with a deviancy training hypothesis and are not consistent with a teacher-management hypothesis or a teacher rater-bias hypothesis. Both the teacher-management hypothesis and the teacher rater-bias hypothesis predict that the effect of peers would be similar for same-gender and opposite-gender peers. In contrast, the deviancy training model, as a social learning model, predicts that peers who are similar to the child will have a greater influence on their behavior. This prediction holds in our analyses of both second- and third-grade children.

These findings also support the hypothesis that children’s development has a wide range of influences, including the environment in which they spend a good part of their days: the elementary school classroom and its peer social climate. In regard to the peer social climate, these findings contradict those of Henry et al. (2000), who found that the mean level of aggression in the classroom had no significant impact on individual student’s aggression among children in mid to late elementary school; this contradiction may come from differences in sample age, as the children in the current sample are younger than most of the children in Henry et al.’s sample. Alternatively, it could stem from differences in the dependent variable. Whereas Henry et al. considered only aggression, we used authority-acceptance problems, a more generalized measure of student oppositional and conduct problem behavior. It is also possible that more direct measures of teachers’ classroom management skills or skill deficits would better reveal the role that teachers might play in setting and enforcing classroom norms about aggression.

In tests of our fourth hypothesis, we also found a trend for deviant children in the second grade to likely be placed with other deviant children in the third grade. Here we see the policy relevance of our findings. First, policies to redistribute children may have important effects on deviant children. Those deviant children who may be on course to develop more serious behavioral problems might only have their authority-acceptance problems’ growth speeded up by their placement into a particularly deviant classroom (Kellam et al., 1998). As Kellam et al. (1998) and Henry et al. (2000) found, there is a great deal of variation in both the level of deviance and the acceptability of deviance in elementary school classrooms. Children are penalized in terms of peer relations when their aggression in nonnormative, but peer cultures for which antisocial behavior is normative do not tend to disinhibit or penalize a child for antisocial behavior (Stormshak et al., 1999). Thus, children with particularly high levels of authority-acceptance problems who are placed into classrooms with high levels of authority-acceptance problems among their same-gender peers will be expected to maintain or increase their own levels of authority-acceptance problems. In contrast, children with similarly high levels of authority-acceptance problems who are instead placed into classrooms with lower levels of authority-acceptance problems among their same-gender peers may be observed to reduce their own authority-acceptance problems.

Second, interventions to change classrooms behavioral norms may have important effects on deviant behavior, especially for deviant children. For instance, the Fast Track intervention includes a universal component in its prevention model. This universal component, which involves the PATHS (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies) curriculum and teacher consultation (CPPRG 1999), aims to change the average classroom climate through norm-setting and a curriculum that focuses on self-control, emotional awareness, peer relations, and problem solving. CPPRG (1999) found that this universal intervention has a significant influence on reducing aggression and hyperactive-disruptive behavior in the classroom. Other interventions, such as the Good Behavior Game (Kellam, Rebok, Ialongo, & Mayer, 1994) and the Dina Dinosaur Treatment Program (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2003), have also been found to reduce aggressive behavior in the classroom during the early elementary years.

The most surprising finding in the current study was the failure to identify subgroups of children who were relatively more or less susceptible to deviant peer influences. The adolescent literature (Dodge & Sherrill, 2006) suggests that marginally deviant youths will be most susceptible to peer influences. In contrast, the current study with younger children revealed that all groups of children, including nondeviant, marginally deviant, and deviant youths as well as both boys and girls and African Americans and European Americans, are robustly influenced by the classroom peer group norm for deviant behavior. Reconciling these age differences may require future studies, but it is plausible that modest-magnitude peer influences are universal and that exacerbation of peer influences occurs during early adolescence and affects some groups of youth to a greater degree than others.

The present findings focus on children in the early years of elementary school. Whereas this is an important stage in children’s educational life course in the development of classroom habits and beliefs about behavior, it is also a time at which conduct problems tend to attract little media attention. These findings suggest the presence of iatrogenic processes in that the behavior of children worsens in the presence of nonconforming peers. We have identified one avenue through which the behavior of children can worsen across their elementary school careers. Future research should investigate these findings with children in later elementary, middle, and high schools. In the meantime, we have found what most parents know at some level to be true. Regardless of their prior levels of deviance, children grow in misbehavior when exposed to influential misbehaving peers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R18 MH48043, R18 MH50951, R18 MH50952, and R18 MH50953. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and the National Institute on Drug Abuse also have provided support for Fast Track through a memorandum of agreement with the NIMH. This work was also supported in part by Department of Education grant S184U30002 and NIMH grants K05MH00797 and K05MH01027. We are grateful for the close collaboration of the Durham Public Schools, the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, the Bellefonte Area Schools, the Tyrone Area Schools, the Mifflin County Schools, the Highline Public Schools, and the Seattle Public Schools.

Footnotes

Members of the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, in alphabetical order, include Karen L. Bierman, Pennsylvania State University; John D. Coie, Duke University; Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University; Mark T. Greenberg, Pennsylvania State University; John E. Lochman, University of Alabama; Robert J. McMahon, University of Washington; and Ellen E. Pinderhughes, Tufts University.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Stearns, University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University

Melba Nicholson, Northwestern University.

References

- Aber JL, Brown JL, Jones SM. Developmental trajectories toward violence in middle childhood: Course, demographic differences, and response to school-based intervention. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:324–348. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth JM, Dunlap ST, Dane H, Lochman JE, Wells KC. Classroom environment influences on aggression, peer relations, and academic focus. Journal of School Psychology. 2004;42:115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Morales J. Proximal peer-level effects of a small-group selected prevention on aggression in elementary school children: An investigation of the peer contagion hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:325–338. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Dodge KA, Pastorelli C, Zelli A Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The effects of marginal deviations on behavioral development. European Psychologist. 2006;11(2):79–89. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.11.2.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Continuities and changes in children’s social status: A five year longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1983;9:261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Coie J, Dodge KA, Kupersmidt JB. Peer group behavior and social status. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Kupersmidt JB. A behavioral analysis of emerging social status in boys’ groups. Child Development. 1983;54:1400–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J. Assigning deviant youth to minimize total harm. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- CPPRG [Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group] Initial impact of the Fast Track Prevention Trial for Conduct Problems II: Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:648–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CPPRG [Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group] Social Health Profile–Spring. 1995 Available from the Fast Track Project Web site, http://www.fasttrackproject.org.

- CPPRG [Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group] A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorders: The Fast Track Program. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:509–527. [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier ME, Cillessen AHN, Coie JD, Dodge KA. Group social context and children’s aggressive behavior. Child Development. 1994;65:1068–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM, Spracklen KM, Li F. Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:803–824. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Eddy JM, Haas E, Li F, Spracklen KM. Friendship and violent behavior during adolescence. Social Development. 1997;6:207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Poulin F, Burraston B. Peer group dynamics associated with iatrogenic effects in group interventions with high-risk young adolescents. In: Nangle DW, Erdley CA, editors. Damon’s New Directions in Child Development: The role of friendship in psychological adjustment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Behavioral antecedents of peer social status. Child Development. 1983;54:1386–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, Lynam D. Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Price JM, Coie JD, Christopoulos C. On the development of aggressive dyadic relationships in boys’ peer group. Human Development. 1990;33:260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Sherrill MR. Deviant peer-group effects in youth mental health interventions. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs or youth: Problems and solutions. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Slusarcick AL. Paths to high school graduation or dropout: A longitudinal study of a first-grade cohort. Sociology of Education. 1992;65:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK, Henkel RR. Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development. 2003;74:205–220. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AD, Bierman KL CPPRG [Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group] Predictors and consequences of aggressive-withdrawn problem profiles in early grade school. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:299–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Smith M, Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, McCord J. Peer influence in children and adolescents: Crossing the bridge from developmental to intervention science. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:225–265. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3563-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Martin CL, Fabes RA, Leonard S, Herzog M. Exposure to externalizing peers in early childhood: Homophily and peer contagion process. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:267–281. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Guerra NG, Huesmann R, Tolan P, VanAcker R, Eron L. Normative influences on aggression in urban elementary school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:59–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1005142429725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo N, Vaden-Kiernan N, Kellam S. Early peer rejection and aggression: Longitudinal relations with adolescent behavior. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 1998;10:199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Ling X, Merisca R, Brown CH, Ialongo N. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:165–185. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Rebok GW, Ialongo N, Mayer L. The course and malleability of aggressive behavior from early first grade into middle school: Results of a developmental epidemiologically-based preventive trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:359–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Aggression in the context of gender development. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Fabes RL. The stability and consequences of young children’s same-sex peer interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:431–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Ialongo NS, Hunter AG, Kellam SG. Family structure and aggressive behavior in a population of urban elementary school children. Journal of the American Academy of child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:540–548. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair JJ, Pettit GS, Harrist A, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Encounters with aggressive peers in early childhood: Frequency, age differences, and correlates of risk for behaviour problems. International Journal of Behavioural Development. 1994;17:675–696. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Schrepferman L, Oeser J, Patterson G, Stoolmiller M, Johnson K, Snyder A. Deviancy training and association with deviant peers in young children: Occurrence and contribution to early-onset conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:397–413. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, Bruschi C, Dodge KA, Coie JD CPPRG [Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group] The relation between behavior problems and peer preference in different classroom contexts. Child Development. 1999;70:169–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Bierman KL CPPRG [Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group] The impact of classroom aggression on the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:471–487. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K. Gangs and delinquency in developmental perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vaden-Kiernan N, Ialongo N, Pearson J, Kellam S. Household family structure and children’s aggressive behavior: A longitudinal study of urban elementary school children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:553–568. doi: 10.1007/BF01447661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. Treating conduct problems and strengthening social and emotional competence in young children. The Dina Dinosaur Treatment Program. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11:130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam SG, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JC, Giammarino M, Parad HW. Social status in small groups: Individual-group similarity and the social “misfit. Journal of Personality and social Psychology. 1986;50:523–536. [Google Scholar]