Abstract

Objective:

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) results from an asymmetric degeneration of the language dominant (usually left) hemisphere and can be associated with the pathology of Alzheimer disease (AD) or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). This study aimed to investigate whether the anatomic distribution of TDP-43 inclusions displayed a corresponding leftward asymmetry in a patient with PPA with a mutation in the progranulin gene and FTLD pathology.

Methods:

Brain tissue from a 65-year-old patient with PPA and progranulin mutation was analyzed using immunohistochemical methods for TDP-43. Analysis was performed in the superior temporal gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, orbitofrontal cortex, entorhinal cortex, and dentate gyrus. Neuronal intranuclear inclusions, neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, and dystrophic neurites were quantified using modified stereologic analysis. Analysis of variance was used to determine significant effects.

Results:

All 3 types of inclusions predominated on the left side of analyzed cortical regions. They were also more frequent in language areas than in memory-related areas.

Conclusion:

These results demonstrate a phenotypically concordant distribution of abnormal TDP-43 inclusions in primary progressive aphasia (PPA). This contrasts with PPA cases with Alzheimer pathology where no consistent leftward asymmetry of neurofibrillary degeneration or amyloid deposition has been demonstrated despite the leftward asymmetry of the atrophy, and where neurofibrillary tangles show a greater density in memory than language areas despite the predominantly aphasic phenotype. This case suggests that the TDP-43 inclusions in PPA–frontotemporal lobar degeneration are more tightly linked to neuronal death and dysfunction than neurofibrillary and amyloid deposits in PPA–Alzheimer disease.

GLOSSARY

- AD

= Alzheimer disease;

- AIPL

= anterior part of inferior parietal lobule;

- DG

= dentate gyrus;

- DN

= dystrophic neurite;

- EC

= entorhinal cortex;

- FTLD

= frontotemporal lobar degeneration;

- ITG

= inferior temporal gyrus;

- NCI

= neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion;

- NII

= neuronal intranuclear inclusion;

- OF

= orbitofrontal cortex;

- PIPL

= posterior part of inferior parietal lobule;

- PPA

= primary progressive aphasia;

- STG

= superior temporal gyrus.

Dementias can be classified by phenotype, according to the nature of the most salient cognitive or behavioral impairment that disrupts daily living activities.1 The most readily recognized phenotypes are those characterized by predominant amnestic, aphasic, visuospatial, or behavioral impairments. Each of these clinical dementia profiles is associated with distinctive and phenotypically concordant sites of peak atrophy and hypometabolism. Examples include the relatively selective hippocampo-entorhinal atrophy in the amnestic dementia of typical Alzheimer disease (AD), frontotemporal atrophy in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), occipitoparietal atrophy in the visuospatial syndrome of posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), and left perisylvian and temporal atrophy in primary progressive aphasia (PPA).

Dementia phenotypes have preferred but not unique neuropathologic correlations. The same clinical profile, and its corresponding distribution of atrophy, may be associated with several neuropathologic entities, each characterized by a distinctive set of abnormal protein aggregates. In contrast to the extensively investigated relationship between atrophy patterns and phenotype, the relationship between the distribution of these aggregates and the clinical phenotype is poorly understood, especially in the frontotemporal lobar degenerations (FTLD). This is the question we addressed in a case of PPA caused by a mutation in the progranulin gene, and where the postmortem examination showed abnormal aggregates of the TAR DNA binding protein (TDP-43).

METHODS

Case material.

Tissue was analyzed from a member of the PPA3 family (patient B) in which a progranulin (PGRN) mutation is associated with familial PPA.2 The patient, a right-handed woman, had presented with complaints of depression and dizziness followed by progressive impairments of word finding. Her speech was described as markedly anomic. She was unable to write a full sentence. Runs of fluent speech could alternate with dysfluent runs, interrupted by numerous word-finding pauses. Category fluency was reduced, but confrontation naming was initially intact. Intermittent language comprehension deficits were noted 1 year after onset. Personality, memory for events, and daily living activities were described as normal during the first 18 to 24 months. No face or object recognition deficits were noted. A mild right-hand tremor was present at the onset and progressed to a state of clumsiness and rigidity on the right side. The diagnosis was PPA because aphasia was the most prominent feature of the clinical picture. MRI, obtained early in the disease, reported “atrophy” but was not available for more careful examination. An EEG revealed asymmetric left temporal rhythmic delta.

She died at the age of 67 years, 5 years after onset.

Histologic evaluation.

Immunohistochemical evaluation from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was performed using antibodies to β-amyloid, tau, ubiquitin, and TDP-43.

TDP-43–positive neuronal intranuclear inclusions (NIIs), neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCIs), and dystrophic neurites (DNs) were quantified.

Inclusions were quantified at 600× magnification in 7 brain regions bilaterally, in 5 parallel sections (thickness 3 μm) per region, with a modified stereologic analysis using the Stereo Investigator performed by an observer blinded to hemispheric laterality. Regions included bilateral superior temporal gyrus (STG; mid-BA22), inferior temporal gyrus (ITG; posterior BA20), anterior and posterior parts of inferior parietal lobule (AIPL and PIPL; BA39–40), entorhinal cortex (EC), dentate gyrus (DG), and orbitofrontal cortex (OF; approximately mid-BA11).

Statistical analysis.

Counts per slide based on 5 parallel sections were analyzed applying analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Neurofibrillary tangles were sparse and present in the EC only, consistent with Braak stage I. The density of neuritic plaques was low to moderate. The combination of tangle and plaque density did not meet diagnostic criteria for AD.3

TDP-43 inclusions distribution was of Mackenzie type 1,4 Sampathu type 3.5

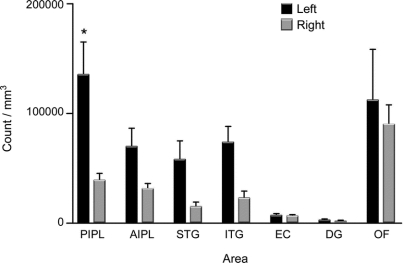

The table lists the regional density of NCIs, NIIs, and DNs. The largest differences between left and right sides were present in language-related regions: inferior parietal lobule (e.g., up to fivefold difference for NIIs) and superior temporal gyrus (e.g., up to sixfold difference for DNs). The counts of inclusions in the posterior inferior parietal lobule (for NCIs), anterior inferior parietal lobule (for NIIs), and orbitofrontal cortex (for NIIs) were higher on the left compared to the right side (p < 0.05). When counts from language areas were combined (AIPL, PIPL, and STG), dystrophic TDP neurites showed higher values (p < 0.001) on the left when compared with homologous regions on the right. We also found that the abnormal TDP deposits in neocortex were more numerous than those in the memory-related areas (entorhinal cortex and dentate gyrus, p < 0.01) and that there were no lateral asymmetries in the latter.

Table Counts of TDP-43-positive inclusions in a case of primary progressive aphasia due to a progranulin gene mutation

The figure demonstrates total count differences between left and right side in each region.

Figure Total TDP-43 counts per cubic milliliter (neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, neuronal intranuclear inclusions, and dystrophic neurites) bilaterally in 7 brain regions

*p < 0.05. AIPL = anterior part of inferior parietal lobule; DG = dentate gyrus; EC = entorhinal cortex; ITG = inferior temporal gyrus; OF = orbitofrontal cortex; PIPL = posterior part of inferior parietal lobule; STG = superior temporal gyrus.

DISCUSSION

In a previous investigation of 4 patients with PPA with AD histopathology, we conducted a semiquantitative determination of NFT and amyloid plaques. In contrast to the typical amnestic phenotype of AD, where the NFT densities are highest in memory-related parts of the brain such as the hippocampo-entorhinal complex,6 we found no clear relationship between the clinical picture and the distribution of AD-related markers. In this small sample, there was no consistent leftward asymmetry in the density of amyloid or NFT, and the density of NFT in the hippocampus-entorhinal complex was much higher than in language-related cortical areas despite the nonamnestic but aphasic PPA phenotype.7 Furthermore, in vivo amyloid imaging of patients with PPA with suspected underlying AD has not revealed asymmetric amyloid binding despite the asymmetric dysfunction associated with the aphasia phenotype.8 This lack of concordance is somewhat surprising given the fact that other atypical AD variants with prominent frontal or visuospatial impairments do show NFT distributions that favor the anatomic substrates of the major deficit.7 In contrast to the poor anatomic relationship between the histopathologic deposits and the aphasic phenotype in patients with PPA with AD pathology, the patient with PPA in this report demonstrated a distribution of abnormal TDP-43 deposits that was clinically concordant with the aphasic phenotype, namely leftward asymmetry and greater concentration in language- than memory-related parts of the brain. This case shows that the abnormal TDP deposits in FTLD are closely related to the distribution of the neurosynaptic dysfunction and to the resultant clinical phenotype. It is also known that the same progranulin mutation can cause bvFTD in one family member and PPA in another.9 It will be interesting to see if the TDP aggregates in the bvFTD phenotype will show preferential concentration in frontotemporal cortex.

The results of our previous investigations on patients with PPA with AD pathology and the analysis of this case with FTLD-TDP suggest that the relevance of disease-specific inclusions to the aphasic phenotype of PPA is much tighter in cases with a postmortem diagnosis of FTLD-TDP than in cases with a postmortem diagnosis of AD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Dr. Gediminas Gliebus and Dr. Changiz Geula.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Gliebus is supported by the Rosenstone Fellowship at Northwestern University Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Center. Dr. Bigio, K. Gasho, and Dr. Mishra report no disclosures. Dr. Caplan serves on the editorial board of Language and Cognitive Processes; receives research support from the NIH (5 RO1 DC00942-12 [PI], NIDCD 5 R01 DC02146-12 [PI], NIDCD 1R21DC010461-01 [PI of MGH subcontract], NIDCD 2 R01 DC003108-11A1 [Co-I], and R305G050083 [Co-I]); and has worked for several law firms and insurance companies as an expert witness in closed head injury cases. Dr. Mesulam serves on scientific advisory boards for the Cure Alzheimer Fund and the Association on Frontotemporal Dementia; serves on the editorial boards of Brain, Annals of Neurology, Human Brain Mapping, and Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience; receives royalties from the publication of Principles of Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology (Oxford University Press, 2000); and receives research support from the NIH (AG13854 [PI] and DC008552 [PI]). Dr. Geula serves on a speakers' bureau for and has received funding for travel from Novartis; serves on the editorial boards of Current Signal Transduction Therapy, Middle Eastern Journal of Family Medicine, Middle Eastern Journal of Family Medicine, and The Open Aging Journal; and receives research support from Novartis, the NIH (NS057429 [PI]), Alzheimer's Association, and Dana Foundation; and holds stock in Novartis.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Gediminas Gliebus, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 320 East Superior Street, Searle 11-467, Chicago, IL 60611 g-gliebus@md.northwestern.edu

Study funding: Supported in part by the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (DC008552) and the National Institute on Aging (AG13854; Alzheimer's Disease Center).

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

Received November 15, 2009. Accepted in final form February 4, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weintraub S, Mesulam M. With or without FUS, it is the anatomy that dictates the dementia phenotype. Brain 2009;132:2906–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesulam M, Johnson N, Krefft TA, et al. Progranulin mutations in primary progressive aphasia: the PPA1 and PPA3 families. Arch Neurol 2007;64:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): part II: standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1991;41:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie IR, Baborie A, Pickering-Brown S, et al. Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol 2006;112:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sampathu DM, Neumann M, Kwong LK, et al. Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol 2006;169:1343–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillozet AL, Weintraub S, Mash DC, Mesulam MM. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid, and memory in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003;60:729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesulam M, Wicklund A, Johnson N, et al. Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2008;63:709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabinovici GD, Jagust WJ, Furst AJ, et al. Abeta amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2008;64:388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley BJ, Haidar W, Boeve BF, et al. Prominent phenotypic variability associated with mutations in Progranulin. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:739–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]