Abstract

Sporadic inclusion-body myositis (s-IBM) is the most common muscle disease of older persons. Its muscle-fiber phenotype shares several molecular similarities with Alzheimer-disease (AD) brain, including increased AβPP, accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), and increased BACE1 protein. Aβ42 is prominently increased in AD brain and within s-IBM fibers, and its oligomers are putatively toxic to both tissues -- accordingly, minimizing Aβ42 production can be a therapeutic objective in both tissues. The pathogenic development of s-IBM is unknown, including the mechanisms of BACE1 protein increase.

BACE1 is an enzyme essential for production from AβPP of Aβ42 and Aβ40, which are proposed to be detrimental within s-IBM muscle fibers. Novel noncoding BACE1-antisense (BACE1-AS) was recently shown a)to be increased in AD brain, and b) to increase BACE1 mRNA and BACE1 protein. We studied BACE1-AS and BACE1 transcripts by real-time PCR a) in 10 s-IBM and 10 age-matched normal muscle biopsies; and b) in our established ER-Stress-Human-Muscle-Culture IBM Model, in which we previously demonstrated increased BACE1 protein. Our study demonstrated for the first time that a) in s-IBM biopsies BACE1-AS and BACE1 transcripts were significantly increased, suggesting that their increased expression can be responsible for the increase of BACE1 protein; and b) experimental induction of ER stress significantly increased both BACE1-AS and BACE1 transcripts, suggesting that ER stress can participate in their induction in s-IBM muscle. Accordingly, decreasing BACE1 through a targeted downregulation of its regulatory

BACE1-AS, or reducing ER stress, might be therapeutic strategies in s-IBM, assuming that it would not impair any normal cellular functions of BACE1.

Keywords: Sporadic inclusion-body myositis, BACE1, Amyloid-β, Amyloid-beta precursor protein (AβPP), Cultured human muscle fibers, noncoding BACE1-antisense transcript, Endoplasmic reticulum stress

INTRODUCTION

The understanding of regulation of gene-expression has changed over the last several years. New species of noncoding transcripts, such as antisense RNA or microRNA, have been identified and their role in gene regulation documented [8]. In general, natural antisense transcripts are non-protein-coding single-stranded RNAs complementary to other transcripts [8, 14, 23, 30, 31]. Antisense transcripts have been reported to regulate expression of corresponding sense mRNAs [23, 30, 31]. Two modes of such regulation have been proposed: a) concordant, when an increase or a decrease of an antisense-transcript level results in a parallel change of its sense partner; and b) discordant, when decrease of an antisense-transcript leads to increase of a sense-transcript [30]. There is a growing list of sense-antisense transcript pairs in the mammalian genome -- many of those antisense transcripts participate in regulating expression of genes involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as AD [12, 13, 22].

BACE1 (β-site amyloid-β precursor protein [AβPP] cleaving enzyme1) a transmembrane protein whose expression is tightly regulated [21, 24], is a member of the aspartyl-protease family. BACE1 cleaves AβPP at the N-terminal of Aβ [21, 24], and is a major β-secretase participating in Aβ generation -- its increase leads to overproduction of toxic Aβ42 [16, 21, 24]. A novel regulation of BACE1 mRNA and protein expression involving a conserved noncoding BACE1-antisense transcript (BACE1-AS) was recently described in vivo and in vitro [12]. BACE1-AS, synthesized on the opposite strand of the BACE gene locus, bears 104 nucleotides fully complementary to exon 6 of human BACE1 mRNA [12].

Exposure of cultured cells to various stressors, including hyperthermia, serum starvation, and oxidative stress, leads to significant increase of BACE1-AS, concomitantly with an increase of BACE1 mRNA and BACE1 protein [12]. BACE1-AS and BACE1 together form an RNA duplex, which leads to increased stability of BACE1 mRNA [12]. Increased levels of BACE1-AS were reported in brains of AD patients and of AβPP-transgenic mice [12].

Sporadic inclusion-body myositis (s-IBM) is the most common muscle disease associated with aging. Intriguingly, s-IBM muscle tissue shares several phenotypic similarities with AD brain. In s-IBM there is intra-muscle-fiber accumulation of several AD-characteristic proteins, including: (i) phosphorylated tau in the form of paired helical filaments, (ii) increased AβPP and BACE1 protein, and (iii) accumulation of aggregated Aβ as congophilic β-pleated-sheets, preferentially composed of Aβ42 [2, 4, 29]. Aβ42 is more hydrophobic and more prone to self-association and oligomerization, and it is much more cytotoxic than Aβ40 [5–7, 11]. The progressive course of s-IBM leads to pronounced muscle weakness and severe disability [9, 10], but no dementia [10]. The exact pathogenic evolution of s-IBM is not known, and there is no enduring treatment [2, 10]. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress was proposed to be an important component of the s-IBM pathogenesis [18, 26]. Experimentally, in cultured human muscle fibers, induced ER stress causes: a) activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), b) increased myostatin, c) decreased activity of SIRT1, and d) increased BACE1 protein -- all which also occur within biopsied s-IBM patients’ muscle fibers [17, 20, 32, 33]. In addition, in s-IBM muscle fibers and in our ER stress-induced cultured human muscle fibers model [ER-Stress-Culture-IBM Model], BACE1 binds to AβPP, strongly suggesting a role of BACE1 in AβPP processing [33]. Although BACE1 protein is increased both in s-IBM muscle fibers and the ER-Stress-Culture-IBM Model (27, 28, 33), the mechanisms underlying that BACE1 increase remain unknown.

In this report we show for the first time that in s-IBM muscle fibers BACE1-AS transcript is increased, as compared to the age-matched controls, and it is associated with increased BACE1 mRNA, i.e., a parallel relationship. We also show that in our ER-stress-Culture-IBM Model, BACE1-AS and BACE1 transcripts are increased. These results suggest that ER stress might be one of the forces upregulating BACE1-AS and BACE1 transcripts in s-IBM muscle fibers, and subsequently leading to BACE1 protein increase.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Muscle Biopsies

Experiments were performed on portions of diagnostic muscle biopsies obtained (with informed consent) from 10 s-IBM and 10 age-matched normal-muscle controls (which, after all tests performed, were considered free of muscle disease). s-IBM patients were ages 58–79 years, median age 65; control patients were ages 58–86, median age 74. Diagnoses were based on clinical and laboratory investigations, including our routinely-performed 16-reaction diagnostic histochemistry of muscle biopsies. All s-IBM biopsies met s-IBM diagnostic criteria, having: muscle fibers with vacuoles on Engel trichrome staining; paired helical filaments by SMI-31- and p62-immunoreactivities [2, 10, 19]; and Congo-red-positivity using fluorescence enhancement [3].

Cultured Human Muscle Fibers

Primary cultures of normal human muscle were established, as described [1], from archived satellite cells of portions of diagnostic muscle biopsies from patients who, after all tests were performed, were considered free of muscle disease. Experiments were performed on 5 different culture sets, each established from satellite cells derived from a different muscle biopsy. 20 days after fusion of myoblasts, well-differentiated myotubes were treated for 24 hours, with an established ER stress inducers tunicamycin, an N-glycosylation inhibitor (4µg/ml), or thapsigargin, an inhibitor of ER-calcium-ATPase (300 nM) [15] (both from Sigma Co, St. Louis, MO), which in our previous studies were shown to induce ER stress but no morphologically visible adverse toxic effects [17, 18, 20]. In each experiment, ER-stress-induced cultures were compared to their unstressed sister-control cultures. After treatment, RNA was isolated from experimental and control cultures.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from muscle biopsies was isolated using an RNA isolation kit (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as recently described [17,18]. Total RNA from cultured human muscle fibers was isolated as described, using RNA-bee reagent (Tel-Tech, Friendwood, TX) [17, 18, 20]. 1µg of RNA was subjected to genomic DNA removal, and to cDNA synthesis using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate, at total volume of 25 µl, using 1µl of cDNA, QuantiFastSYBR Green PCR Master mix, and a) appropriate commercial QuantiTect Primers (Qiagen) for BACE1 or GAPDH, or b) previously-published primers and probe for BACE1-AS [12] (Fw-GAAGGGTCTAAGTGCAGACATCTT; Rv-AGGGAGGCGGTGAGAGT; Pr-ACATTCTTCAGCAACAGCC) (synthesized by Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR runs were performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler Realplex2. Cycling conditions were 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds. Relative gene expression was calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCT method, in which the amount of BACE1 or BACE1-AS mRNA was normalized to an endogenous reference gene (GAPDH). The results are expressed as fold induction relative to controls. Correct PCR products were confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis and melting-curve analysis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

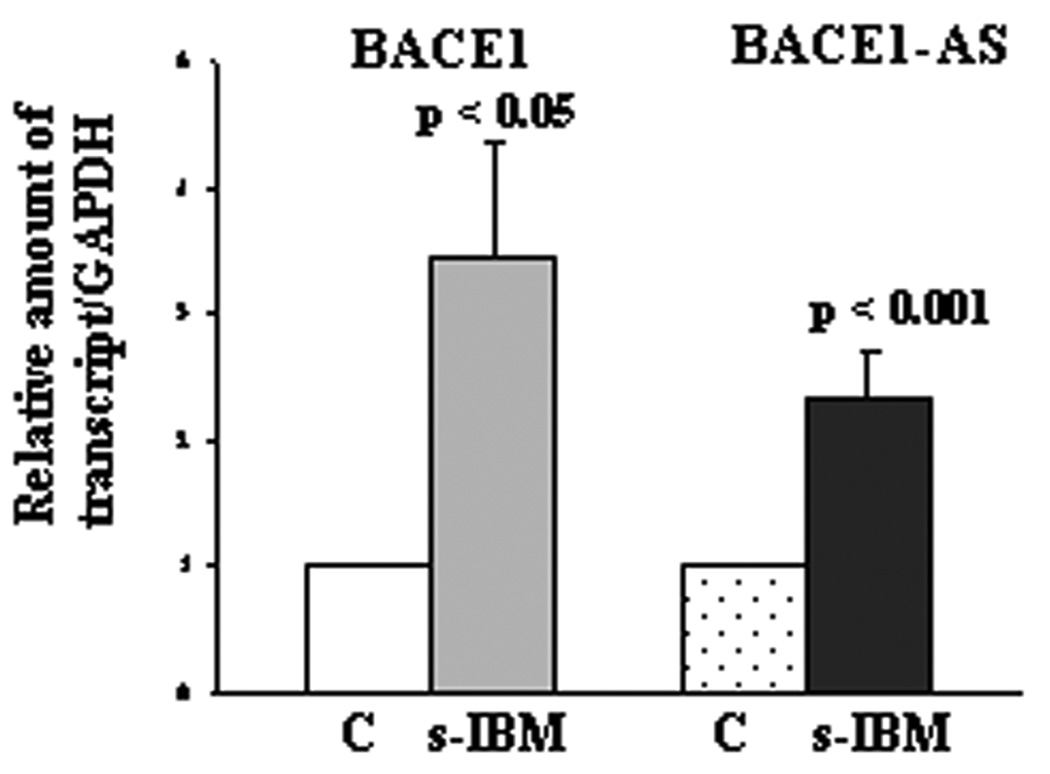

In both control normal muscle biopsies, as well as in cultured normal human muscle fibers, BACE1-AS transcript was much less abundant than BACE1 mRNA (Fig. 1A and B). In s-IBM biopsies, as compared to controls, by real-time PCR BACE1-AS transcript was increased 2.3-fold (p<0.01) and BACE1 mRNA was increased 3.5-fold (p<0.05) (Fig. 2). Treatment of cultured human muscle fibers with the ER stress inducers tunicamycin or thapsigargin increased BACE1-AS transcript levels more than 2.5-fold, p<0.01 for both reagents, and BACE1 mRNA, 1.6-fold, p<0.05, and 1.6-fold, p<0.01 respectively for each (Fig. 3).

Figure1.

BACE1 and BACE1-AS transcripts in control muscle biopsies (A), and in control non-treated normal cultured human muscle fibers (B). In both systems, BACE1-AS transcript is much less abundant than BACE1 transcript. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure2.

BACE1 and BACE1-AS transcripts in biopsied control “C” and s-IBM muscle fibers. BACE1 and BACE1-AS transcripts are significantly increased in s-IBM as compared to controls. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure3.

BACE1 and BACE1-AS transcripts in cultured human muscle fibers: “C” = non-treated controls. Tm = Tunicamycin, Tg = Thapsigargin. Under ER stress conditions induced by either Tm or Tg, BACE1 and BACE1-AS transcripts are significantly increased. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

BACE1 mRNA was previously shown to be regulated by its natural BACE1 antisense transcript in the concordant parallel way [12]; and BACE1-AS has been shown to increase BACE1 mRNA stability and its translation [12]. Here we show for the first time that in s-IBM muscle biopsies, BACE1-AS transcript is significantly increased and is accompanied by an increase of BACE1 mRNA. We previously reported increase of BACE1 protein in s-IBM muscle fibers -- our present findings suggest that the increased BACE1 protein results, at least partially, from the increased transcription of BACE1 mRNA, quite likely driven by BACE1-AS. In contrast to AD and AD-transgenic-mouse brain samples in which BACE1-AS transcript was increased more than the sense BACE1 transcript [12], in our s-IBM muscle biopsies the reversed was found. The significance of this finding is presently unknown, and might be due to a tissue specificity, muscle versus brain, or to other factors. Although the elevation of BACE1-AS in various cell lines due to different cellular stresses was reported [12], the influence of endoplasmic reticulum stress has not been specifically studied to our knowledge. We here demonstrate that in our ER-stress-induced previously-normal cultured human muscle fibers (ER-Stress-Culture-IBM Model), both BACE1-AS and BACE1 transcripts were significantly increased, the BACE1-AS transcript being increased proportionally more than the sense BACE1 transcript. These data, together with our previous demonstration that, in the same experimental model, ER stress increased the level of BACE1 protein [33], suggest an important role of ER stress in upregulation of BACE1. Furthermore, in s-IBM muscle, elevated BACE1-AS transcript, either in response to ER stress itself, or in combination with other intra-cellular stresses such as oxidative stress [25, 34], may increase BACE1mRNA and BACE1 protein, thereby leading to increased production of toxic Aβ42 [29].

The presence of BACE1 mRNA in control muscle biopsies and in cultured human muscle fibers indicates that BACE1 is a normal muscle protein, presumably synthesized to play a physiological role there. For example, BACE1 is strongly expressed at the postsynaptic domain of normal human neuromuscular junctions [28].

Natural sense-antisense pairs are widely present in the human genome [13], but their role in regulation of gene expression and in the pathogenic evolution of various diseases is not fully understood. Our study suggests that s-IBM is another disease in which natural non-coding antisense transcripts very likely play a pathogenic role. Moreover, our observation, that in s-IBM BACE1-AS is increased and might be increasing BACE1 mRNA, may have important therapeutic implications. Decreasing BACE1, through a targeted downregulation of its disease-induced regulatory BACE1-AS, could be a future therapeutic strategy in s-IBM, assuming that it would not impair any normal cellular functions of BACE1 and/or BACE1-AS.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Merit Award AG16768), the Muscular Dystrophy Association and The Myositis Association (to VA), and the Helen Lewis Research Fund. Dr. Nogalska is on leave from Department of Biochemistry, Medical University of Gdansk, Gdansk, Poland. We are grateful to Dr. Michael Jakowec of the USC Department of Neurology for allowing us to use his real-time PCR equipment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Askanas V, Engel WK. Cultured normal and genetically abnormal human muscle. In: Rowland LP, Di Mauro S, editors. The Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Myopathies. Vol. 18. North Holland, Amsterdam: 1992. pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Askanas V, Engel WK. Inclusion-body myositis: muscle-fiber molecular pathology and possible pathogenic significance of its similarity to Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease brains. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0449-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askanas V, Engel WK, Alvarez RB. Enhanced detection of Congo-red positive amyloid deposits in muscle fibers of inclusion-body myositis and brain of Alzheimer’s disease using fluorescence technique. Neurology. 1993;43:1265–1267. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.6.1265-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Askanas V, Engel WK, Nogalska A. Inclusion body myositis: a degenerative muscle disease associated with intra-muscle fiber multi-protein aggregates, proteasome inhibition, endoplasmic reticulum stress and decreased lysosomal degradation. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:493–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta -protein (Abeta) assembly: Abeta 40 and Abeta 42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:330–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y-Ru, Glabe C. Distinct early folding and aggregation properties of Alzheimer amyloid-β peptides Aβ40 and Aβ42. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24414–24422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chromy BA, Nowak RJ, Lambert MP, Viola KL, Chang L, Velasco PT, Jones BW, Fernandez SJ, Lacor PN, Horowitz P, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Self-assembly of Abeta (1–42) into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12749–12760. doi: 10.1021/bi030029q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa FF. Non-coding RNAs: New players in eucaryotic biology. Gene. 2005;357:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalakas MC. Sporadic inclusion body myositis--diagnosis, pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:437–447. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engel WK, Askanas V. Inclusion-body myositis: clinical, diagnostic, and pathologic aspects. Neurology. 2006;66:20–29. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192260.33106.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;7:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM, Wood DE, Sahagan BG, Morgan TE, Finch CE, St Laurent G, 3rd, Kenny PJ, Wahlestedt C. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat Med. 2008;14:723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faghihi MA, Wahlestedt C. Regulatory roles of natural antisense transcripts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapidot M, Pilpel Y. Genome-wide natural antisense transcription: coupling its regulation to its different regulatory mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1216–1222. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee AS. The ER chaperone and signaling regulator GRP78/BiP as a monitor of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Methods. 2005;35:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Zhou W, Tong Y, He G, Song W. Control of APP processing and Abeta generation level by BACE1 enzymatic activity and transcription. FASEB J. 2006;20:285–292. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4986com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogalska A, D'Agostino C, Engel WK, Davies KJ, Askanas V. Decreased SIRT1 deacetylase activity in sporadic inclusion-body myositis muscle fibers. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.021. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nogalska A, Engel WK, McFerrin J, Kokame K, Komano H, Askanas V. Homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum protein (Herp) is up-regulated in sporadic inclusion-body myositis and in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cultured human muscle fibers. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1491–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nogalska A, Terracciano C, D'Agostino C, Engel WK, Askanas V. p62/SQSTM1 is overexpressed and prominently accumulated in inclusions of sporadic inclusion-body myositis muscle fibers, and can help differentiating it from polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nogalska A, Wojcik S, Engel WK, McFerrin J, Askanas V. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces myostatin precursor protein and NF-kappaB in cultured human muscle fibers: relevance to inclusion body myositis. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:610–618. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossner S, Sastre M, Bourne K, Lichtenthaler SF. Transcriptional and translational regulation of BACE1 expression--implications for Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smalheiser NR, Lugli G, Torvik VI, Mise N, Ikeda R, Abe K. Natural antisense transcripts are co-expressed with sense mRNAs in synaptoneurosomes of adult mouse forebrain. Neurosci Res. 2008;62:236–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.St Laurent G, 3rd, Wahlestedt C. Noncoding RNAs: couplers of analog and digital information in nervous system function? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stockley JH, O'Neill C. Understanding BACE1: essential protease for amyloid-beta production in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3265–3289. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terracciano C, Nogalska A, Engel WK, Wojcik S, Askanas V. In inclusion-body myositis muscle fibers Parkinson-associated DJ-1 is increased and oxidized. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vattemi G, Engel WK, McFerrin J, Askanas V. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in inclusion body myositis muscle. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vattemi G, Engel WK, McFerrin J, Buxbaum JD, Pastorino L, Askanas V. Presence of BACE1 and BACE2 in muscle fibres of patients with sporadic inclusion-body myositis. Lancet. 2001;358:1962–1964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vattemi G, Engel WK, McFerrin J, Pastorino L, Buxbaum JD, Askanas V. BACE1 and BACE2 in pathologic and normal human muscle. Exp Neurol. 2003;179:150–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(02)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vattemi G, Nogalska A, King Engel W, D'Agostino C, Checler F, Askanas V. Amyloid-beta42 is preferentially accumulated in muscle fibers of patients with sporadic inclusion-body myositis. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0511-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahlestedt C. Natural antisense and noncoding RNA transcripts as potential drug targets. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner A, Carlile M, Swan D. What do natural antisense transcripts regulate? RNA Biol. 2009;6:43–48. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.1.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wojcik S, Engel WK, McFerrin J, Askanas V. Myostatin is increased and complexes with amyloid-beta within sporadic inclusion-body myositis muscle fibers. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:173–177. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojcik S, Engel WK, Yan R, McFerrin J, Askanas V. NOGO is increased and binds to BACE1 in sporadic inclusion-body myositis and in A beta PP-overexpressing cultured human muscle fibers. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:517–526. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang CC, Alvarez RB, Engel WK, Askanas V. Increase of nitric oxide synthases and nitrotyrosine in inclusion-body myositis. Neuroreport. 1996;8:153–158. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]