Abstract

Alterations in GABAA receptor (GABAAR) expression and function, similar to those we described previously during pregnancy in the mouse dentate gyrus, may also occur in other brain regions. Here we show, using immunohistochemical techniques, a decreased δ subunit-containing GABAAR (δGABAAR) expression in the dentate gyrus, hippocampal CA1 region, thalamus, and striatum but not in the cerebral cortex. In the face of the highly elevated neurosteroid levels during pregnancy, which can act on δGABAARs, it may be beneficial to decrease the number of neurosteroid-sensitive receptors to maintain a steady-state level of neuronal excitability throughout pregnancy. Consistent with this hypothesis, the synaptic input/output (I/O) relationship in the dentate gyrus molecular layer in response to lateral perforant path stimulation was shifted to the left in hippocampal slices from pregnant compared with virgin mice. The addition of allopregnanolone, at levels comparable with those found during pregnancy (100 nm), shifted the I/O curves in pregnant mice back to virgin levels. There was a decreased threshold to induce epileptiform local field potentials in slices from pregnant mice compared with virgin, but allopregnanolone reverted the threshold for inducing epileptiform activity to virgin levels. According to these data, neuronal excitability is increased in pregnant mice in the absence of allopregnanolone attributable to brain region-specific downregulation of δGABAAR expression. In brain regions, such as the cortex, that do not exhibit alterations in δGABAAR expression, there were no changes in the I/O relationship during pregnancy. Similarly, no changes in network excitability were detected in pregnant Gabrd−/− mice that lack δGABAARs, suggesting that changes in neuronal excitability during pregnancy are attributable to alterations in the expression of these receptors. Our findings indicate that alterations in δGABAAR expression during pregnancy result in brain region-specific increases in neuronal excitability that are restored by the high levels of allopregnanolone under normal conditions but under pathological conditions may result in neurological and psychiatric disorders associated with pregnancy and postpartum.

Introduction

We recently demonstrated plasticity of GABAA receptors (GABAARs) during pregnancy and postpartum, in which the expression of the GABAAR δ and γ2 subunits in dentate gyrus granule cells are decreased during pregnancy, resulting in diminished tonic and phasic inhibitions mediated by these receptors (Maguire and Mody, 2008). Changes in GABAergic function during pregnancy have also been inferred from increased agonist binding during pregnancy (Majewska et al., 1989; Concas et al., 1999) and decreased expression of the mRNA encoding the GABAAR γ2 subunit during pregnancy (Concas et al., 1998; Follesa et al., 1998). δGABAARs are the preferred, if not sole, site of action for neurosteroids in the physiological concentration range in the mammalian CNS (Stell et al., 2003; Belelli and Lambert, 2005). Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that the GABAergic system and, in particular, the tonic inhibition mediated by δGABAARs may play a role in steroid hormone-mediated changes in neuronal excitability.

Changes in neuronal excitability, e.g., changes in seizure frequency, associated with pregnancy are difficult to assess because of many factors, including but not limited to noncompliance with antiepileptic drug usage, alterations in the pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs, hormonal changes, sleep deprivation, and stress. The available literature on seizures associated with pregnancy reveals that there is an increase in seizure frequency in 24% of the 2165 cases studied, a decrease in 23%, and no change in 53% of cases (Schmidt, 1982), demonstrating the complex relationship between pregnancy and epilepsy. More recent findings also support the idea that pregnancy has variable effects on seizure frequency (Sabers et al., 1998; Rück and Bauer, 2008).

Changes in seizure frequency during pregnancy are thought to result from hormonal changes; however, the mechanisms of steroid hormone-induced changes in neuronal excitability during pregnancy remain unclear. It is known that steroid hormone derivatives, or neurosteroids, are potent modulators of GABAARs; thus, it is likely that the production of neurosteroids throughout pregnancy may alter neuronal excitability via actions on GABAARs. In addition, steroid hormones have been shown to alter GABAAR subunit expression. Administration and withdrawal of exogenous progesterone alters GABAAR subunit expression (Concas et al., 1998; Smith et al., 1998; Follesa et al., 2000, 2001, 2002; Biggio et al., 2001; Smith, 2002). To complicate this picture, modulators acting on δGABAARs, such as allopregnanolone and ethanol, also alter GABAAR subunit expression (Follesa et al., 2004). The expression of the GABAAR α1, α4, and γ2 subunits are altered by exposure to exogenous neurosteroids (Smith et al., 1998; Follesa et al., 2000, 2001, 2002; Smith, 2002). GABAAR γ2 subunit mRNA levels are inversely correlated with neurosteroid levels, such that increased levels of allopregnanolone are associated with decreased GABAAR γ2 subunit mRNA levels (Follesa et al., 2004). However, it is unclear how changes in GABAAR structure and function alter neuronal excitability in response to physiological conditions, such as pregnancy, which result in large elevations in progesterone and neurosteroid levels. Therefore, by examining synaptic input/output (I/O) function, we sought to determine whether the alterations in GABAARs throughout pregnancy are associated with altered neuronal excitability.

The objective of this study was to determine possible changes in δGABAAR expression in several brain regions and to determine the effect of GABAAR plasticity on neuronal network excitability using extracellular field recordings. Here we demonstrate brain region-specific changes in δGABAAR expression, which increase network excitability in the absence of allopregnanolone. Physiological levels of allopregnanolone present in the intact brain of pregnant mammals dampen the increased neuronal excitability to pre-pregnancy levels, suggesting that the changes in GABAARs constitute a homeostatic mechanism to ensure a normal level of inhibition throughout pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult, ∼3 months of age, C57BL/6 and Gabrd−/− mice (on C57BL/6 background) were housed and maintained by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited Division of Laboratory Medicine. All procedures used were Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved by the UCLA Chancellor's Animal Research Council. Animals were maintained on a normal light/dark cycle (12 h, lights on from 6:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M.) and had ad libitum access to food and drinking water. All experiments were performed during the light cycle. Animals were killed between 10:00 A.M. and 12:00 P.M.. The virgin mice used in this study were anovulatory, noncycling mice. The pregnant mice used in this study were first-time pregnant mice at day 18 of pregnancy. The postpartum mice used were first-time dams at 48 h postpartum. All genotyping was performed by Transnetyx.

Immunohistochemistry

Age-matched adult virgin and day 18 pregnant C57BL/6 mice or Gabrd−/− mice were anesthetized and perfused intracardially with PBS, followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Brains were cryoprotected at 4°C in increasing concentrations (10–30%) of sucrose and then placed in a −80° freezer. Coronal sections (50 μm thick) prepared on a cryostat were placed in PBS until staining, which was performed within 48 h of sectioning. All staining procedures were done under nonpermeabilized conditions to ensure immunoreactivity of only surface, and therefore functionally relevant, proteins. Slices from virgin and pregnant mice were processed in parallel from the time of perfusion, throughout the processing, immunostaining, mounting, and analysis of the tissue. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the sections in 3% H2O2 diluted in methanol for 1 h. Sections were washed with PBS incubated in 10% normal goat serum diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-GABA δ (1:1000, AB9752; Millipore Corporation) in TBS and 10% normal goat serum. After incubation with the primary antibody, the sections were washed three times in TBS before incubation with a biotinylated secondary anti-rabbit antibody (1:2000; Vector Laboratories) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed three times in TBS, incubated with an HRP-conjugated avidin enzyme complex (ABC Elite; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h, washed again three times in TBS, and developed with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories). The sections were mounted, coverslipped, and analyzed by light microscopy. Sections from paired animals were processed in parallel to ensure equivalent development of each experimental group for comparison, and pictures were taken in parallel to ensure equivalent exposure of each experimental group.

Optical density was determined using NIH ImageJ software. The optical density was measured in the region of interest, throughout serial sections in each animal. The region of interest in the dentate gyrus consisted of the entire molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. The optical density was measured in the dentate gyrus molecular layer in serial sections (∼45 sections per animal). The region of interest in the cortex consisted of all six cortical layers (∼25 sections per animal). The background staining was determined to be minimal, as assessed in Gabrd−/− mice, demonstrating the specificity of the antibody used for these experiments (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) (see Figs. 1–3). In addition, the background between experimental groups was low and not significantly different between experimental groups; thus, background subtraction was deemed unnecessary. The average optical density was determined for each animal, and the average across animals (n = 5 for each experimental group) was used for statistical tests.

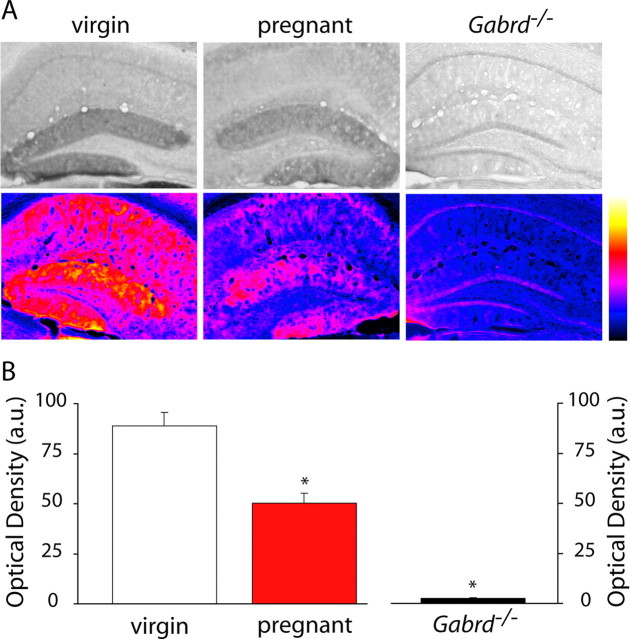

Figure 1.

Decreased GABAA receptor δ subunit expression in the dentate gyrus in pregnant animals. A, Representative bright-field and spectrum color-transformed images of the dentate gyrus from wild-type virgin, pregnant, and Gabrd−/− virgin mice stained with an antibody specific for the GABAAR δ subunit. B, Optical density measurements show a significant decrease in GABAAR δ subunit in wild-type pregnant mice compared with virgin mice. The lack of staining in Gabrd−/− virgin mice confirm the specificity of the antibody. *p < 0.05 using the Student's t test compared with virgin wild type. a.u., Arbitrary units.

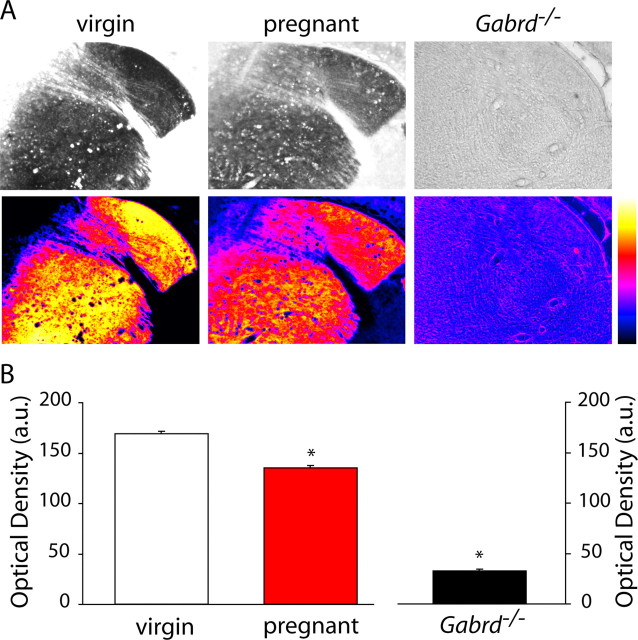

Figure 2.

Decreased GABAA receptor δ subunit expression in the striatum in pregnant animals. A, Representative bright-field and spectrum color-transformed images of the striatum from wild-type virgin, pregnant, and Gabrd−/− virgin mice stained with an antibody specific for the GABAAR δ subunit. B, Optical density measurements show a significant decrease in GABAAR δ subunit in wild-type pregnant mice compared with virgin mice. The lack of staining in Gabrd−/− virgin mice confirm the specificity of the antibody. *p < 0.05 using the Student's t test compared with virgin wild type. a.u., Arbitrary units.

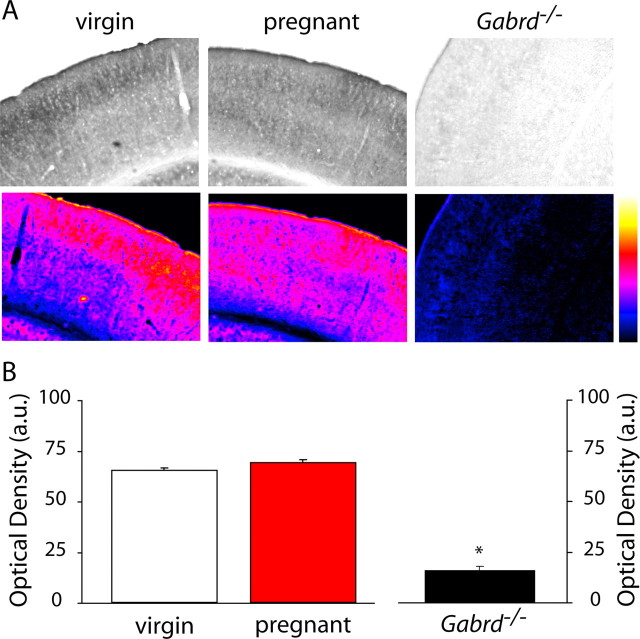

Figure 3.

No change in GABAA receptor δ subunit expression in the cortex of pregnant mice. A, Representative bright-field and spectrum color-transformed images of the somatosensory cortex from wild-type virgin, pregnant, and Gabrd−/− virgin mice stained with an antibody specific for the GABAAR δ subunit. B, Optical density measurements show no significant change in the expression of GABAAR δ subunits in wild-type pregnant mice compared with virgin mice. The lack of staining in Gabrd−/− virgin mice confirm the specificity of the antibody. No significance detected using the Student's t test. a.u., Arbitrary units.

Field potential recordings

Synaptic input/output curves.

Coronal hippocampal slices (350 μm thick) were prepared from adult (∼3 months old) wild-type virgin, day 18 pregnant, and 48 h postpartum mice. Hippocampal field recordings were performed at 32–34°C under standard conditions in an interface chamber perfused with normal artificial CSF (nACSF) solution containing [in mm: 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1–2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaHPO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 d-glucose, pH 7.3–7.4 (bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2)]. Allopregnanolone at 100 nm (dissolved in 0.01% DMSO) was added, when indicated, to the nACSF in the incubation chamber and perfused into the recording chamber for at least 5 min before recording. Field potentials were evoked by lateral perforant path stimulation at 0.05 Hz, and responses were recorded in the dentate gyrus molecular layer. Bipolar electrodes were used to deliver a constant-current stimulus. The stimulus intensity was determined by recording a threshold response at a width (W) of 60 μs with no response at 20 μs. The W of the stimulus was increased stepwise by 20 μs to create I/O curves ranging from 20 to 240 μs. Four population field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were recorded at each W, and the maximum slope of the responses (volts per second) was measured over a 0.5–1 ms window of the fEPSP rising phase. The average slope was calculated at each W used.

Input/output curves were fit with a Boltzmann equation: f(W) = (MAX/(1 + exp((W − W50)/k)) + MAX), where W is stimulus width, MAX is the maximum response, k is a slope factor, and W50 is the stimulus width that elicits 50% of MAX. The fitted parameters were compared between experimental groups, and statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's corrected t tests.

Epileptiform activity induced by high KCl.

Hippocampal slices were prepared and maintained as described above. Slices were tested before recordings to ensure their health and appropriate responses to electrical stimulation. Spontaneous extracellular field potentials were measured in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus. Synchronous discharges were measured in increasing concentrations of extracellular KCl, normal ACSF (2.5), 5.0, 7.5, and 10 mm. The frequency and duration of discharges were measured. Only slices that exhibited synchronous discharges in 10 mm KCl were considered to have a sufficiently healthy local circuitry to be considered in the experimental results. Epileptiform discharges were considered to be population field potentials that had an increased amplitude of 2 SDs above the baseline activity recorded in nACSF. In addition, a discharge frequency of >1 Hz for at least 5 s was required to constitute epileptiform discharges in this study. Allopregnanolone (100 nm) was added to the incubation chamber and also bath applied when indicated.

Results

Changes in δGABAAR expression during pregnancy

We previously used Western blot analysis to demonstrate a downregulation in δGABAAR expression in the hippocampus from pregnant mice (day 18) compared with virgin animals (Maguire and Mody, 2008). To determine whether there are changes in the expression levels of δGABAARs in other brain regions during pregnancy, we performed immunohistochemical analysis throughout the brains of virgin and pregnant mice (day 18). A decrease in δGABAARs was confirmed in the dentate gyrus of pregnant compared with virgin mice, similar to our previous results by Western blot analysis (Maguire and Mody, 2008). Representative bright-field and spectrum color-transformed δGABAAR stains of the dentate gyrus in virgin and pregnant mice are shown in Figure 1A. The optical density of δGABAAR immunoreactivity in the dentate gyrus molecular layer, in which this protein is predominantly localized (Peng et al., 2004), was measured throughout the hippocampus of each animal (n = 3 mice per experimental group, 46 sections per animal). There was a low variability in the δGABAAR immunoreactivity between sections from the same animal (virgin SEM, 2.05; pregnant SEM, 1.84), demonstrating that there is little regional difference in δGABAAR immunoreactivity between the rostral and caudal hippocampus. The optical densities in the 46 hippocampal sections were averaged for each mouse, and the average optical density from each individual animal was used to calculate the average optical density from all the animals in a given group. The data reveal a 41.9 ± 4.8% decrease in the optical density of δGABAAR immunostaining in pregnant compared with virgin mice (Fig. 1B, Table 1). The lack of staining in the dentate gyrus molecular layer of Gabrd−/− mice confirms the specificity of δGABAAR staining in the wild-type virgin and pregnant mice (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) (Fig. 1). In addition to changes in the dentate gyrus, there is a significant decrease in δGABAAR in the striatum. Representative grayscale and corresponding color-transformed images of δGABAAR immunoreactivity in the striatum is shown in Figure 2A and Table 1. In each animal, the optical density was measured in 25 adjacent striatal sections, and the average from each individual animal was used to determine the average for each group. The optical density of striatal δGABAAR immunoreactivity during pregnancy was decreased by 20.3 ± 4.0% compared with virgin levels (Fig. 2B, Table 1). Interestingly, there is no change in the expression of δGABAAR in the cortex throughout pregnancy (Fig. 3, Table 1). Representative sections from virgin and pregnant mice reveal similar levels of δGABAAR expression in the cortex (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Immunoreactivity was measured in 35 adjacent cortical sections per animal. There is no significant difference in the optical density measurements of δGABAAR immunoreactivity in the cortex: pregnant mice were 107.8 ± 7.5% that of virgin mice (Fig. 3B, Table 1). These data demonstrate that the changes in δGABAAR expression throughout pregnancy are brain region specific. A list of optical density measurements in different brain regions is given in Table 1. To note, there is a downregulation in δGABAAR expression in the dentate gyrus, hippocampal CA1 region, striatum, and several nuclei of the thalamus but no change in the cortex. We did not observe an increase in δGABAAR expression in any of the brain regions examined.

Table 1.

Optical density measurements in multiple brain regions in virgin and pregnant mice

| Hippocampal formation | Virgin | Pregnant | Two-way ANOVA |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational stage | Animal | Interaction | |||

| Dentate gyrus | 69.8 ± 2.0 | 40.6 ± 1.8 | |||

| n (sections) | 138 | 138 | |||

| n (mice) | 3 | 3 | F(330.3, 1, 270), 9.30 × 10−49 | F(7.337, 2, 270), 7.89 × 10−4 | F(4.566, 2, 270), 1.12 × 10−2 |

| CA1 | 25.2 ± 2.2 | 16.3 ± 2.0 | |||

| n (sections) | 64 | 61 | |||

| n (mice) | 3 | 3 | F(25.59, 1, 119), 1.55 × 10−6 | F(10.55, 2, 119), 6.05 × 10−5 | F(3.234, 2, 119), 4.29 × 10−2 |

| Cortex | 65.1 ± 2.1 | 69.1 ± 2.0 | |||

| n (sections) | 105 | 105 | |||

| n (mice) | 3 | 3 | F(2.614, 1, 204), 1.07 × 10−1 | F(16.73, 2, 204), 1.87 × 10−7 | F(6.865, 2, 204), 1.30 × 10−3 |

| Striatum | 168.7 ± 3.9 | 135.1 ± 3.7 | |||

| n (sections) | 74 | 84 | |||

| n (mice) | 3 | 3 | F(115.6, 1, 152), 2.09 × 10−20 | F(45.71, 2, 152), 2.86 × 10−16 | F(2.915, 2, 152), 5.72 × 10−2 |

| Thalamus | |||||

| VL | 162.2 ± 5.6 | 145.0 ± 5.0 | F(14.41, 1, 73), 3.01 × 10−4 | F(5.346, 2, 73), 6.81 × 10−3 | F(0.3652, 2, 73), 6.95 × 10−1 |

| VA | 126.3 ± 7.2 | 108.2 ± 6.1 | F(10.19, 1, 73), 2.08 × 10−3 | F(1.981, 2, 73), 1.45 × 10−1 | F(0.1531, 2, 73), 8.58 × 10−1 |

| VPL | 159.7 ± 4.6 | 129.1 ± 5.7 | F(35.48, 1, 73), 8.34 × 10−8 | F(2.301, 2, 73), 1.07 × 10−1 | F(1.887, 2, 73), 1.59 × 10−1 |

| n (sections) | 37 | 42 | |||

| n (mice) | 3 | 3 | |||

The average optical density was determined for each individual animal, and the average optical density from each animal was used for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was determined using a two-way ANOVA for gestational stage and individual variability. The F values are given as F(sum of squares, degrees of freedom, mean square). Bold F values denote significance at p < 0.05.

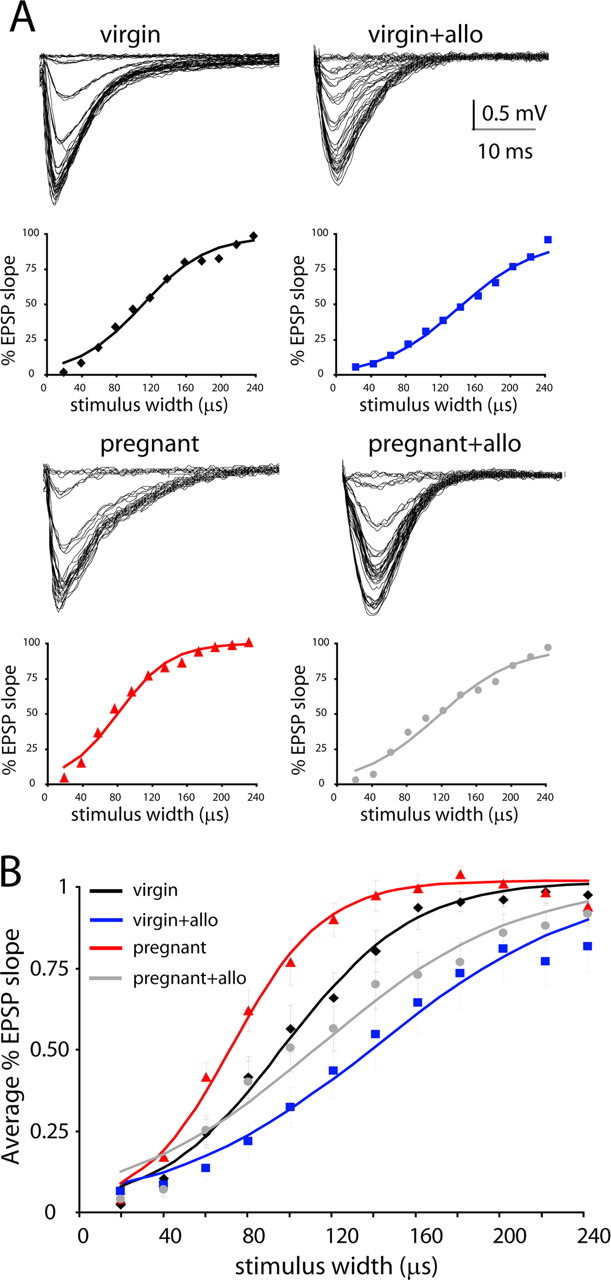

Changes in synaptic I/O function during pregnancy

The effect of decreased δGABAAR expression in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 1) on synaptic excitability was investigated by analyzing the synaptic I/O relationship of the dentate gyrus of virgin and pregnant mice. The fEPSP was measured in the molecular layer in response to lateral perforant path stimulation of varying stimulus widths (see Materials and Methods). There was no significant difference in the stimulus intensity between experimental groups in wild-type mice (Table 2). However, the stimulus intensities required to evoke fEPSPs in Gabrd−/− were lower compared with those used in wild-type mice (Table 2). Representative fEPSP raw traces and I/O curves from individual wild-type virgin and pregnant mice in the presence or absence of 100 nm allopregnanolone (equivalent to physiological levels during pregnancy) (Paul and Purdy, 1992) are shown in Figure 4A. The symbols represent the percentage of averaged fEPSP slope relative to the slope of the largest fEPSP in four stimulation trials in a representative experiment from virgin and pregnant mice. The average I/O relationships for these representative experiments were fit with a Boltzmann function, where W50 is the stimulus width that elicits the half-maximal response and the k value is the slope factor, and the Boltzmann curve from representative experiments are represented as a solid line in Figure 4B. These representative experiments demonstrate a shift to the left in the I/O relationship in slices from pregnant mice compared with virgin, suggesting an increase in neuronal population excitability. The addition of allopregnanolone (100 nm) shifted the I/O curve in slices from pregnant mice back toward virgin levels.

Table 2.

Brain region-specific changes in fEPSP input/output relationships during pregnancy

| W50 (μs) | k values | Intensity (μA) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type dentate gyrus | ||||

| Virgin | 101.2 ± 7.9 | 26.4 ± 3.7 | 554.2 ± 44.6 | 13 |

| Virgin + Allo | 158.4 ± 21.3* | 42.9 ± 9.5* | 557.7 ± 50.3 | 13 |

| Pregnant | 75.9 ± 5.5* | 19.9 ± 2.6* | 540.5 ± 46.9 | 13 |

| Pregnant + Allo | 123.7 ± 13.3 | 35.8 ± 4.3 | 669.4 ± 45.6 | 18 |

| Wild-type cortex | ||||

| Virgin | 108.9 ± 7.1 | 32.3 ± 2.9 | 500.0 ± 14.5 | 15 |

| Virgin + Allo | 106.2 ± 8.4 | 37.0 ± 3.8 | 482.1 ± 31.3 | 16 |

| Pregnant | 120.4 ± 10.2 | 38.7 ± 3.9 | 500.0 ± 0.0 | 18 |

| Pregnant + Allo | 106.5 ± 7.4 | 33.5 ± 3.9 | 500.0 ± 47.2 | 16 |

| Gabrd−− dentate gyrus | ||||

| Virgin | 134.1 ± 11.8 | 38.0 ± 4.4 | 384.8 ± 27.1 | 13 |

| Virgin + Allo | 153.9 ± 14.6 | 39.5 ± 4.7 | 415.4 ± 36.9 | 13 |

| Pregnant | 116.8 ± 6.5 | 33.2 ± 3.0 | 454.5 ± 30.5 | 13 |

| Pregnant + Allo | 127.5 ± 13.7 | 37.8 ± 3.7 | 409.1 ± 38.0 | 12 |

* denotes significance compared with virgin animals in each group. Input/output relationships were constructed for virgin and pregnant mice in the wild-type dentate gyrus, in the wild-type cortex, and in the dentate gyrus of Gabrd−/− mice. The effect of 100 nm allopregnanolone (Allo) was determined for each condition. The input/output curves were fit with a Boltzmann function, and the W50 and k values are given. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's corrected t test.

Figure 4.

Changes in network excitability during pregnancy reversed by allopregnanolone. A, Representative traces and I/O curves from individual experiments in the dentate gyrus from wild-type virgin and pregnant mice in the presence or absence of allopregnanolone (allo). B, The average I/O curves for virgin (♦), virgin plus 100 nm allopregnanolone (■), pregnant (▲), and pregnant plus 100 nm allopregnanolone (●) are indicated. The average I/O curves were fit with a Boltmann function for virgin (black line), virgin plus 100 nm allopregnanolone (blue line), pregnant (red line), and pregnant plus 100 nm allopregnanolone (gray line).

To obtain the grand average I/O relationship from all experiments, the fitted parameters of the individually normalized (MAX = 1) Boltzmann functions were averaged from virgin and pregnant slices in the presence or absence of allopregnanolone (Fig. 5A). The I/O relationships were compared between experimental groups, and the W50 and k values are given in Table 2. The W50 in pregnant mice was decreased to 75% that of the W50 in virgin mice, consistent with an increase in network excitability in slices from pregnant mice. The addition of physiological levels of allopregnanolone (100 nm) restored the W50 to122% of virgin levels (Fig. 5A). These data demonstrate an increase in synaptic excitability in the dentate gyrus during pregnancy in the absence of allopregnanolone. However, when levels of allopregnanolone found in pregnancy are restored in the slices, the synaptic I/O function is comparable with that found in virgin animals. Thus, the downregulation of δGABAARs appears to be a homeostatic mechanism to maintain a constant level of synaptic I/O function in the face of elevated allopregnanolone levels throughout pregnancy (see Discussion).

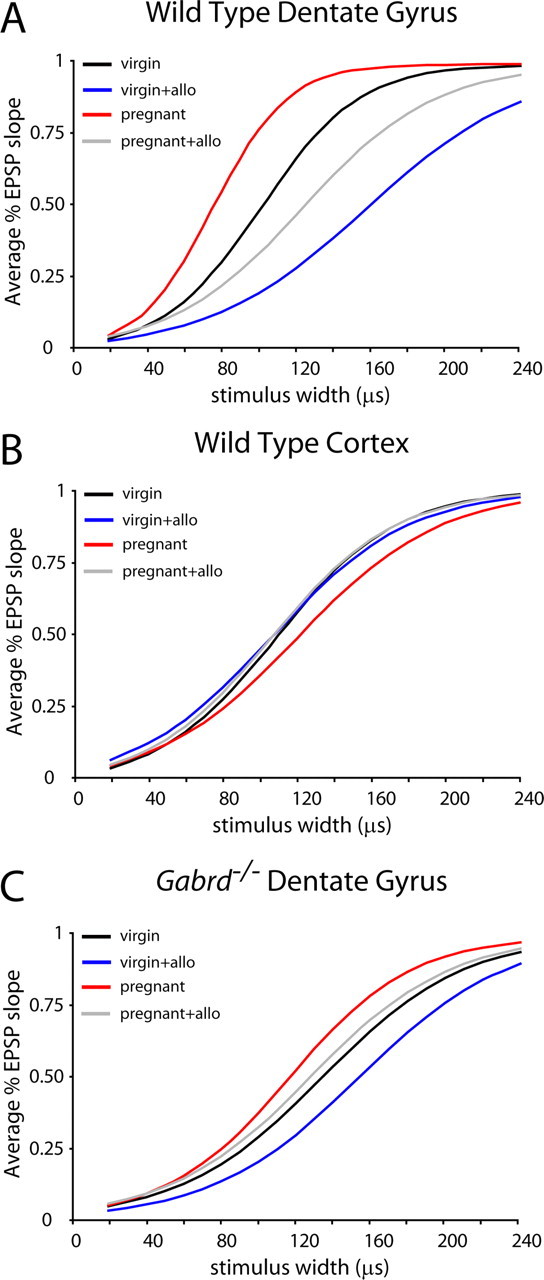

Figure 5.

Changes in network excitability during pregnancy related to GABAAR δ subunit expression. A, The average synaptic I/O function from the dentate gyri of wild-type virgin, pregnant, and postpartum mice is shown as a Boltzmann function generated by the averages of the fitted parameters. There is a shift toward increased excitability in the fEPSP slope I/O curves from wild-type pregnant mice (red line) compared with wild-type virgin mice (black line). This increased excitability is restored by 100 nm allopregnanolone (allo) (gray line). B, The average I/O curves of fEPSP slopes from the cortex of wild-type virgin (black line) or pregnant (red line) with or without allopregnanolone (blue and gray lines) demonstrate no significant difference in the W50 between groups, suggesting that the changes in excitability related to pregnancy are brain region specific. C, The average I/O curves of fEPSP slopes from Gabrd−/− virgin (black line), Gabrd−/− virgin plus 100 nm allopregnanolone (blue line), Gabrd−/− pregnant (red line), and Gabrd−/− pregnant plus 100 nm allopregnanolone (gray line). There is no significant difference in the W50 between Gabrd−/− groups. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's corrected t tests.

Consistent with the proposed importance of δGABAAR changes on neuronal excitability during pregnancy, changes in synaptic I/O curves were only present in brain regions that exhibited changes in δGABAAR expression. Brain regions with no changes in δGABAAR expression during pregnancy, such as the cortex, do not display changes in network excitability associated with pregnancy. The I/O curves generated from the averages of the fitted parameters (MAX = 1) from wild-type virgin and pregnant mice in the presence or absence of allopregnanolone are similar in the cortex (Fig. 5B, Table 2). There is no difference in the W50 in pregnant mice, with the W50 values being 111% that of virgin mice. Interestingly, the addition of physiological levels of allopregnanolone (100 nm) did not significantly alter the W50 in virgin mice (98%) or pregnant mice (88%) (n = 3–5 mice, 15–18 slices per experimental group) (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that changes in neuronal excitability throughout pregnancy are brain region specific and restricted to areas that exhibit alterations in δGABAAR expression.

These changes in network excitability in the dentate gyrus during pregnancy can be attributed to the changes in δGABAAR expression, because there is no significant difference in the I/O relationship between Gabrd−/− virgin and Gabrd−/− pregnant mice (Fig. 5C, Table 2). The average Boltzmann functions (MAX = 1) generated using the average fitted parameters are shown in Figure 5C. Lateral perforant path stimulation produces a similar half-maximal width (W50) in virgin Gabrd−/− mice that is 115% that of pregnant Gabrd−/− mice (Fig. 5C), suggesting that pregnancy does not alter neuronal excitability in Gabrd−/− mice. In addition, allopregnanolone does not have an effect on neuronal excitability in virgin Gabrd−/− mice, with W50 values increased by 115% in virgin Gabrd−/− mice and 109% in pregnant Gabrd−/− mice (n = 3–4 mice, 12–13 slices per experimental group) (Fig. 5C), likely attributable to the fact that the main site of action of allopregnanolone, the δGABAAR, is absent in these mice. These data highlight the importance of specific δGABAAR changes in mediating in the altered neuronal excitability throughout pregnancy.

Changes in epileptiform network excitability during pregnancy

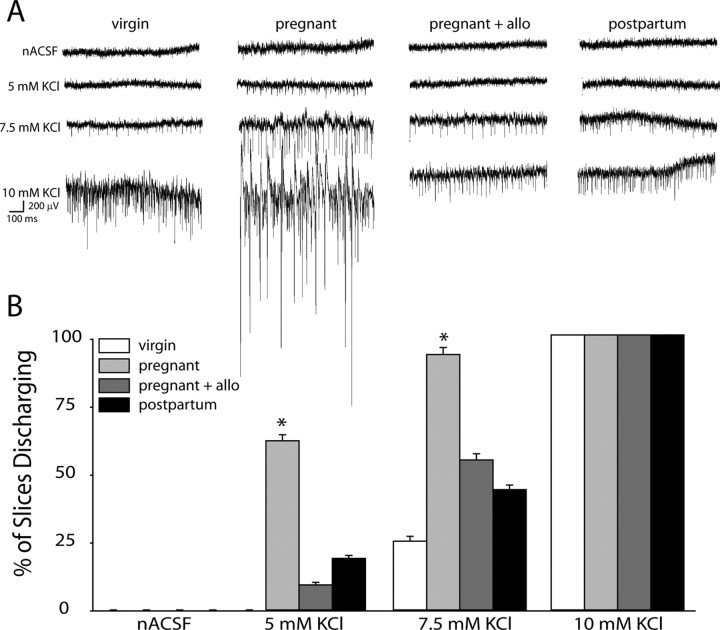

To further investigate the effect of GABAAR changes during pregnancy on network function, we examined the excitability of the network in response to elevated levels of extracellular KCl. The threshold to induce epileptiform activity in the CA1 region of the hippocampus was decreased in slices from pregnant mice compared with slices from virgin mice (Fig. 6). Although the CA1 region is not particularly rich in δGABAAR, the decrease observed during pregnancy (Table 1) may result in an enhanced excitability of the interconnected CA1 network. Representative recordings from virgin, pregnant, and postpartum mice in the absence or presence of allopregnanolone are shown in Figure 6A. The percentage of slices discharging at 5 mm extracellular KCl was increased during pregnancy (61.5 ± 2.2%) compared with virgin (0.0 ± 0.0%) and postpartum (18.8 ± 1.1%) mice. Similarly, the percentage of slices exhibiting epileptiform activity in 7.5 mm KCl was increased in slices from pregnant mice (92.9 ± 2.8%) compared with slices from virgin (25.0 ± 1.8%) and postpartum mice (43.8 ± 1.7%). The addition of physiological levels of allopregnanolone (100 nm) decreased the excitability in slices from pregnant mice back to virgin and postpartum levels at 5 mm KCl (9.1 ± 0.9%) and 7.5 mm KCl (54.5 ± 2.2%) (n = 3–5 mice, 7–18 slices per experimental group; significance determined using a one-way ANOVA at each concentration of KCl) (Fig. 6B). These data further suggest that, in the absence of allopregnanolone, the decrease in δGABAAR in the CA1 region combined with that in the dentate gyrus during pregnancy results in hippocampal hyperexcitability; however, in the presence of physiological levels of allopregnanolone, which would be present in the intact brain, there is no difference in excitability during pregnancy compared with virgin.

Figure 6.

Network hyperexcitability during pregnancy in the absence of allopregnanolone. A, Representative traces in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in nACSF and 5, 7.5, and 10 mm extracellular KCl in virgin, pregnant, and postpartum wild-type mice. B, The average percentage of slices discharging at increasing concentrations of extracellular KCl was increased in pregnant mice compared with virgin and postpartum mice. This increase in excitability was not evident in the presence of physiological concentrations of allopregnanolone (allo) (100 nm). *p < 0.05 using a one-way ANOVA at each concentration of KCl compared with virgin wild-type slices in nACSF.

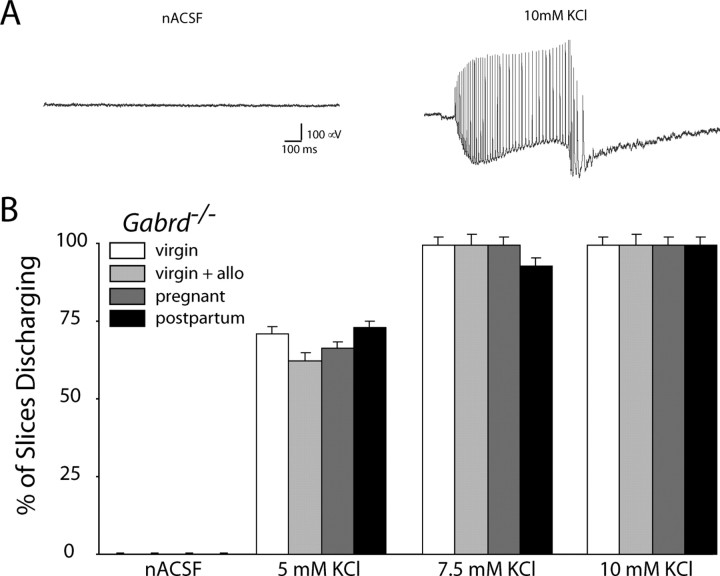

Mice deficient in δGABAAR regulation throughout pregnancy, such as Gabrd−/− mice, exhibit increased network excitability (Fig. 7) compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 6). At 5 mm KCl, 0.0 ± 0.0% of wild-type virgin slices exhibit epileptiform discharges compared with 71.4 ± 2.3% in Gabrd−/− virgin mice. At 7.5 mm KCl, 25.0 ± 1.8% of wild-type virgin slices exhibit epileptiform discharges compared with 100 ± 0.0% in Gabrd−/− virgin mice. However, Gabrd−/− mice do not exhibit changes in network excitability during pregnancy or postpartum. Gabrd−/− mice, either virgin or pregnant, exhibit epileptiform activity in the presence of increased extracellular KCl. Control and epileptiform activity in Gabrd−/− mice is shown in Figure 7A. Slices from Gabrd−/− mice are hyperexcitable and exhibit large depolarizing shifts with epileptiform discharges (Fig. 7A), although no significant difference is found between virgin and pregnant mice in the presence or absence of allopregnanolone. The percentage of slices discharging at 5 mm extracellular KCl was similar in Gabrd−/− virgin mice (71.4 ± 2.3%), Gabrd−/− pregnant mice (66.7 ± 2.1%), and Gabrd−/− postpartum mice (73.3 ± 2.2%). Similarly, there was no difference in the percentage of slices exhibiting epileptiform activity in 7.5 mm KCl from virgin mice (100 ± 0.0%) compared with slices from pregnant mice (100 ± 0.0%) and postpartum mice (100 ± 0.0%) (n = 3–5 mice, 8–15 slices per experimental group; significance determined using a one-way ANOVA at each concentration of KCl) (Fig. 7B). In addition, the neuronal excitability in Gabrd−/− mice is unaffected by addition of 100 nm allopregnanolone (5 mm KCl, 62.5 ± 2.8%; 7.5 mm KCl, 100 ± 0.0%), likely attributable to the absence of δGABAARs for allopregnanolone to act on. Thus, the inability to regulate δGABAAR expression may prevent changes in network excitability during pregnancy, rendering the network hyperexcitable.

Figure 7.

Network hyperexcitability in Gabrd−/− mice. A, Representative traces in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in Gabrd−/− mice in nACSF and 10 mm extracellular KCl. B, The average percentage of slices discharging at increasing concentrations of extracellular KCl was not significantly different in pregnant mice compared with virgin and postpartum mice. Physiological levels of allopregnanolone (allo) (100 nm) had no effect on excitability in Gabrd−/− mice. No significance was detected at any concentration of KCl using a one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

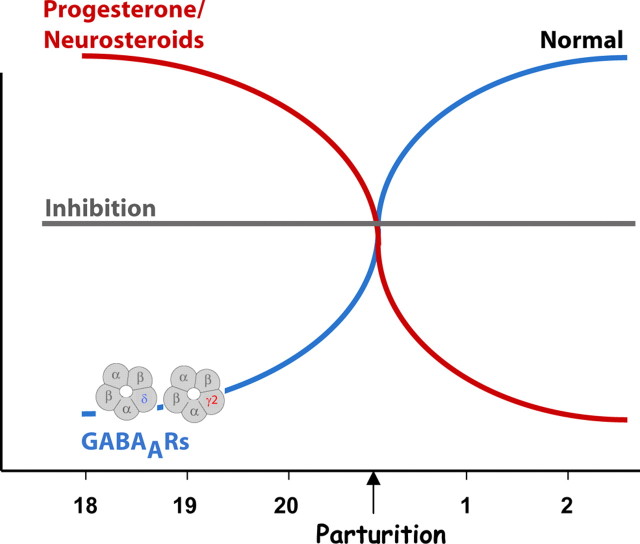

In this report, we demonstrate brain region-specific changes in GABAAR subunit expression during pregnancy. There is a decrease in the expression of δGABAARs during late pregnancy, which may constitute a homeostatic mechanism to maintain a steady level of inhibition throughout pregnancy (Fig. 8). In this model, we propose that the expression of δGABAARs must become downregulated in the face of extremely high levels of neurosteroids during pregnancy, which can act as positive allosteric modulators of these receptors, to maintain a level of inhibition throughout pregnancy equivalent to that before this stage (Fig. 8). At the time of parturition, neurosteroid levels abruptly decline and δGABAARs must be recovered, again to maintain a constant level of inhibition throughout the postpartum period (Fig. 8). Failure to properly regulate these receptors throughout pregnancy and postpartum may play a role in neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders associated with this vulnerable period.

Figure 8.

A model of GABAAR plasticity throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period. In the face of robust levels of neurosteroids throughout pregnancy, GABAARs must become downregulated to maintain an ideal level of inhibition throughout pregnancy and prevent sedation and/or anesthesia in gravid mammals. At parturition, neurosteroid levels abruptly decline, and the expression levels of GABAARs must be recovered to maintain the ideal level of inhibition throughout the postpartum period. GABAAR regulation represents a homeostatic mechanism to maintain an ideal level of inhibition in the face of changing neurosteroid levels throughout pregnancy and postpartum.

Changes in various GABAAR subunits have been observed during pregnancy; however, the contribution of these changes to neuronal excitability during pregnancy remained elusive. Changes in GABAARs during pregnancy has been inferred from decreased agonist binding (Majewska et al., 1989; Concas et al., 1999) and decreased sensitivity to benzodiazepines (Concas et al., 1998; Follesa et al., 1998). Previous studies have demonstrated decreased expression of γ2 in the hippocampus (Concas et al., 1998; Follesa et al., 1998) and decreased expression of the GABAAR α5 in the cortex (Follesa et al., 1998). In addition, several studies reported changes in GABAAR subunit expression in progesterone withdrawal models, mainly an increase in α4 and δ subunit expression (Smith et al., 1998; Sundstrom-Poromaa et al., 2002). Here we report a decrease in δGABAAR expression in day 18 pregnant mice in several different brain regions, such as the dentate gyrus, CA1, striatum, and thalamus. A recent report demonstrated a different pattern of δGABAAR regulation during late pregnancy in the rat (Sanna et al., 2009), suggesting perhaps that δGABAAR regulation throughout pregnancy and postpartum may be species specific. However, this study used a different antibody, untested for specificity in Gabrd−/− animals, to quantify changes in δGABAAR immunoreactivity in the dentate gyrus granule cell layer, which is not the typical localization of these receptors (Peng et al., 2004). Our findings demonstrate alterations in δGABAAR expression in the dentate gyrus molecular layer, which is where this protein is most abundant (Peng et al., 2004).

Our data suggest that alterations in δGABAARs, specifically, are essential for the changes in neuronal excitability during pregnancy. The evidence that allopregnanolone restores neuronal excitability to virgin levels further suggests a role for δ GABAARs in neuronal excitability changes during pregnancy. Even more convincing is the lack of neuronal excitability alterations during pregnancy in Gabrd−/− mice. Although not statistically significant, there is a trend toward more hyperexcitability, evident from a slight shift in the I/O curve, during pregnancy in Gabrd−/− mice, which could be attributable to decreased expression of the GABAAR γ2 receptor subunit during pregnancy (Maguire and Mody, 2008). The similarity of the synaptic I/O curves in wild-type and Gabrd−/− mice is most likely attributable to the lower stimulation intensities used to elicit similar population responses in the two preparations (Table 2), consistent with the loss of δGABAAR-mediated tonic inhibition in these mice and the significant contribution of tonic inhibition to overall excitability (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). In addition, the partial compensation of the tonic conductance by α5GABAARs in dentate gyrus granule cells of Gabrd−/− mice may also dampen the differences between the I/O curves recorded in the two genotypes (Glykys et al., 2008).

The hyperexcitability in Gabrd−/− mice becomes evident during depolarization in response to elevated extracellular KCl. Virgin Gabrd−/− mice are hyperexcitable, and pregnancy does not significantly alter the excitability in these animals. The virgin Gabrd−/− mice exhibit epileptiform activity that consists of a large depolarization with epileptiform bursts. In contrast to wild-type mice, in which the epileptiform activity is characterized by synchronous population discharges at regular intervals, the epileptiform activity in Gabrd−/− mice consists of a large depolarization with high-frequency discharges reminiscent of epileptiform bursts. The type of epileptiform activity in Gabrd−/− mice is unlike that induced in wild-type slices, suggesting that there may be a different mechanism underlying the epileptogenesis. However, this hypothesis requires additional, intensive investigation that is outside the scope of this study and will be investigated in the future.

Our previous study demonstrated that changes in δGABAAR expression that occur over the ovarian cycle and in response to stress were mediated by steroid hormone-derived neurosteroids (Maguire and Mody, 2007). However, we cannot exclude the contribution of other physiological changes that occur during pregnancy, such as increases in estrogen, oxytocin, corticosterone, and prolactin levels. Estrogens are thought to be proconvulsant, whereas progesterone is thought to act as an anticonvulsant. Estrogen is known to increase hippocampal spine density (Gould et al., 1990; Woolley and McEwen, 1993) and excitatory synapses (Woolley and McEwen, 1992; Woolley et al., 1997) and to alter the sensitivity of NMDA receptors to glutamate (Woolley et al., 1997). In addition, oxytocin and vasopressin can both exert distinct effects on neuronal excitability in the CNS. For instance, in the amygdala, vasopressin is excitatory and inhibited by oxytocin (Huber et al., 2005) (for review, see Raggenbass, 2008), demonstrating that many other physiological changes associated with pregnancy can exert effects on neuronal excitability. Although we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of other physiological factors affecting neuronal excitability during pregnancy, the restoration of neuronal excitability to pre-pregnancy levels by physiological levels of allopregnanolone suggests that neurosteroids and their site of action, the δGABAARs, play a significant role in mediating changes in neuronal excitability associated with pregnancy.

Changes in neuronal excitability have been reported in epileptic women during pregnancy with conflicting results (Schmidt, 1982). Seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy is often difficult to assess attributable to patients noncompliance with drug regimen or changes in the pharmacokinetics of the antiepileptic medications during pregnancy. In addition, experimental studies in animals have been primarily limited because of the use of chemical convulsants, which have inherent problems when working with pregnant animals, including changes in dosing, absorption, and metabolism during pregnancy compared with virgin animals. However, in a kindling model of epileptogenesis, there was no difference in threshold to kindle animals between pregnant mice and controls (Holmes and Weber, 1985). In this study, we systematically assessed changes in network excitability in vitro and in vivo, and our findings demonstrate that pregnancy does not alter network excitability or seizure frequency in the intact animal.

The factors underlying the changes in neuronal excitability during pregnancy have been proposed to result from stress, changes in sleep patterns, metabolic factors, respiratory changes, noncompliance with drugs, changes in the pharmacokinetics of drugs, and changes in seizure propensity during pregnancy (for review, see Swartjes and van Geijn, 1998). Although changes in seizure propensity have been proposed to occur during pregnancy, there is little evidence of intrinsic changes that would render the brain more susceptible to seizures. Our study elucidates changes in GABAergic inhibition during pregnancy that may play a role in excitability changes during pregnancy, including the decrease in δGABAARs in the dentate gyrus, similar to that observed previously by Western blot analysis (Maguire and Mody, 2008) and a decrease in the striatum and the thalamus. However, we did not find a change in δGABAAR expression in the cortex during pregnancy, suggesting that the changes in receptor expression are brain region specific, and their sensitivity to allopregnanolone may also be under region-specific control by yet unknown mechanisms.

Our study is the first to assess changes in network excitability during pregnancy and demonstrates no inherent propensity for hyperexcitability during this hormonally labile period. However, our data also suggest that hyperexcitability during pregnancy has the opportunity to manifest itself if there are abnormal changes in neurosteroid levels or if the receptors for neurosteroid action, namely the δGABAARs, are not properly regulated. In the face of high levels of δGABAAR-targeting neurosteroids throughout pregnancy, the levels of these receptors are decreased to maintain the pre-pregnancy level of inhibition. If neurosteroid levels decline, inhibition will decrease and likely result in hyperexcitability. Similarly, if the levels of δGABAARs decrease too much, inhibition will decrease and the brain will be rendered hyperexcitable.

Our data demonstrate a physiological homeostatic mechanism whereby the brain maintains a steady level of excitability throughout pregnancy. In addition, the importance of the GABAergic system in maintaining a constant level of neuronal I/O function throughout pregnancy suggests that the antiepileptic drugs gabapentin, gabitril, and lamotrigine may be better treatments for women with epilepsy because they target the function of GABAARs, which may be directly involved in the pathophysiology. These and other drugs acting by similar mechanisms may be particularly useful in the treatment of women sensitive to the steroid hormone-associated changes in seizure frequency.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)–National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH076994 and the Coelho Endowment (I.M.). J.M. was also supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from NIH and the Named New Investigator Award from the Center for Neurobiology of Stress at University of California, Los Angeles. We thank Reyes Main Lazaro for his assistance in mouse handling, breeding, and timed pregnancies. His expertise was used for the all pregnancy and postpartum studies.

References

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggio G, Follesa P, Sanna E, Purdy RH, Concas A. GABA(A)-receptor plasticity during long-term exposure to and withdrawal from progesterone. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2001;46:207–241. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(01)46064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concas A, Mostallino MC, Porcu P, Follesa P, Barbaccia ML, Trabucchi M, Purdy RH, Grisenti P, Biggio G. Role of brain allopregnanolone in the plasticity of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor in rat brain during pregnancy and after delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13284–13289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concas A, Follesa P, Barbaccia ML, Purdy RH, Biggio G. Physiological modulation of GABA(A) receptor plasticity by progesterone metabolites. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;375:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: Phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follesa P, Floris S, Tuligi G, Mostallino MC, Concas A, Biggio G. Molecular and functional adaptation of the GABA(A) receptor complex during pregnancy and after delivery in the rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:2905–2912. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1998.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follesa P, Serra M, Cagetti E, Pisu MG, Porta S, Floris S, Massa F, Sanna E, Biggio G. Allopregnanolone synthesis in cerebellar granule cells: roles in regulation of GABA(A) receptor expression and function during progesterone treatment and withdrawal. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:1262–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follesa P, Concas A, Porcu P, Sanna E, Serra M, Mostallino MC, Purdy RH, Biggio G. Role of allopregnanolone in regulation of GABA(A) receptor plasticity during long-term exposure to and withdrawal from progesterone. Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follesa P, Porcu P, Sogliano C, Cinus M, Biggio F, Mancuso L, Mostallino MC, Paoletti AM, Purdy RH, Biggio G, Concas A. Changes in GABA(A) receptor gamma 2 subunit gene expression induced by long-term administration of oral contraceptives in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:325–336. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follesa P, Biggio F, Caria S, Gorini G, Biggio G. Modulation of GABA(A) receptor gene expression by allopregnanolone and ethanol. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABA(A) receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;28:1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Gonadal steroids regulate dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal cells in adulthood. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1286–1291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01286.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL, Weber DA. Effect of pregnancy on development of seizures. Epilepsia. 1985;26:299–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1985.tb05653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D, Veinante P, Stoop R. Vasopressin and oxytocin excite distinct neuronal populations in the central amygdala. Science. 2005;308:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1105636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J, Mody I. Neurosteroid synthesis-mediated regulation of GABA(A) receptors: relevance to the ovarian cycle and stress. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2155–2162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4945-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J, Mody I. GABA(A)R plasticity during pregnancy: relevance to postpartum depression. Neuron. 2008;59:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD, Ford-Rice F, Falkay G. Pregnancy-induced alterations of Gabaa receptor sensitivity in maternal brain: an antecedent of post-partum blues. Brain Res. 1989;482:397–401. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul SM, Purdy RH. Neuroactive steroids. FASEB J. 1992;6:2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Huang CS, Stell BM, Mody I, Houser CR. Altered expression of the delta subunit of the GABA(A) receptor in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8629–8639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2877-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggenbass M. Overview of cellular electrophysiological actions of vasopressin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rück J, Bauer J. Pregnancy and epilepsy. Retrospective analysis of 118 patients (in German) Nervenarzt. 2008;79:691–695. doi: 10.1007/s00115-008-2443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabers A, aRogvi-Hansen B, Dam M, Fischer-Rasmussen W, Gram L, Hansen M, Møller A, Winkel H. Pregnancy and epilepsy: a retrospective study of 151 pregnancies. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;97:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1998.tb00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna E, Mostallino MC, Murru L, Carta M, Talani G, Zucca S, Mura ML, Maciocco E, Biggio G. Changes in expression and function of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the rat hippocampus during pregnancy and after delivery. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1755–1765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3684-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D. New York: Raven; 1982. The effect of pregnancy on the natural history of epilepsy: review of the literature; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS. Withdrawal properties of a neuroactive steroid: implications for GABA(A) receptor gene regulation in the brain and anxiety behavior. Steroids. 2002;67:519–528. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Gong QH, Hsu FC, Markowitz RS, ffrench-Mullen JM, Li X. GABA(A) receptor alpha 4 subunit suppression prevents withdrawal properties of an endogenous steroid. Nature. 1998;392:926–930. doi: 10.1038/31948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I. Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14439–14444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435457100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Smith DH, Gong QH, Sabado TN, Li X, Light A, Wiedmann M, Williams K, Smith SS. Hormonally regulated alpha(4)beta(2)delta GABA(A) receptors are a target for alcohol. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:721–722. doi: 10.1038/nn888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartjes JM, van Geijn HP. Pregnancy and epilepsy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;79:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2549–2554. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Weiland NG, McEwen BS, Schwartzkroin PA. Estradiol increases the sensitivity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells to NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic input: correlation with dendritic spine density. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1848–1859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01848.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]