Abstract

Human embryonic stem cells (hESC) hold great promise as a cell source for tissue engineering since they possess the ability to differentiate into any cell type within the body. However, much work must still be done to control the differentiation of the hESC to the desired lineage. In this study, we examined the effects of the nano-fibrous (NF) architecture in both two dimensional (2-D) poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) thin matrices and 3-D PLLA scaffolds in vitro to assess their affect on the osteogenic differentiation of hESC in vitro compared to more traditional solid films and solid-walled (SW) scaffolds. In 2-D culture, hESC on NF thin matrices were found to express collagen type 1, Runx2, and osteocalcin mRNA of higher levels than the hESC on the solid films after 1 week of culture and increased mineralization was observed on the NF matrices compared to the solid films after 3 weeks of culture. After 6 weeks of 3-D culture, the hESC on the NF scaffolds expressed signifcantly more osteocalcin mRNA compared to these on the SW scaffolds. The data indicates that the NF architecture enhances the osteogenic differentiation of the hESC compared to more traditional scaffolding architecture.

Keywords: Nanofibers, Embryonic Stem Cells, Bone Tissue Engineering, Osteogenesis

Introduction

Pluripotent human embryonic stem cells (hESC) isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocysts represent a potentially unlimited source of cells for tissue engineering[1]. While the proliferative ability of adult stem cells is limited by donor age and time in expansion culture[2, 3], hESC proliferate much longer and can differentiate into any cell type within the body. However, there are several obstacles to using hESC (tumorgencity of the undifferentiated cells and the heterogeneous cell population generated using the current differentiation protocols) which must be overcome prior to their clinical use as a cell source for tissue engineering.

Most attempts to direct hESC differentiation to the osteogenic lineage have focused on the addition of biologically active molecules to hESC in a culture dish [4–7]. To examine the capacity of differentiation or tissue formation, hESC have been encapsulated within an ECM hydrogel by others [8–10]. In previous studies with mouse embryonic stem cells, we found that biologically active molecules in combination with a nanofibrous (NF) architecture of the substrate enhance the osteogenic differentiation of the embryonic stem cells[11, 12].

Type I collagen is a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in bone and consists of three collagen polypeptide chains wound together to form a ropelike superhelix that assembles into the fibers ranging in size from 50 to 500nm in diameter[13]. Using phase separation techniques, we have developed synthetic three dimensional poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) nanofibers of the same size scale as natural type I collagen[14–18].

We hypothesize that the collagen mimicking synthetic nanofibers generated by phase separation advantageously enhance hESC differentiation and tissue formation, eliminating potential problems associated with pathogen transmission and immune response to ECM. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of the NF architecture on the osteogenic differentiation of hESC in this work.

Methods and Materials

Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) with an inherent viscosity of 1.6 dl/g was purchased from Alkermes (Medisorb, Cambridge, Massachusetts) and used without further purification. Cyclohexane, dioxane, ethanol, hexane, and methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Dubecco’s Modified Eagle Media (DMEM), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mix F-12 (D-MEM/F-12), alpha Minimum Essential Medium (αMEM), Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (D-PBS), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), knockout Serum replacer, non-essential amino acids, glutaMAX-I support supplement, TrypLE Express stable trypsin replacement enzyme and PCR primers were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) was obtained from Harlan Biological (Indianapolis, IN). Neuronal Class III β-Tubulin (TUJ1) antibody and goat serum were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Human transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1) and bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2) were obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, New Jersey). Osteocalcin antibody and all secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse anti-human integrin alpha 2 monoclonal antibody and purified mouse IgG1 antibody were obtained from Millipore (Danvers, MA). RNeasy Mini Kit and Rnase-Free DNase set were obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, California). TaqMan reverse transcription reagents, real-time PCR primers, and TaqMan Universal PCR Master mix were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, California). Chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

2-D Thin Matrix and Film Preparation for Cell Culture

PLLA was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran at 60°C to make a 10% (wt/v) PLLA solution. The NF PLLA matrix (thickness~40μm) was fabricated by first casting 0.4 mL of the PLLA solution on a glass support plate which had been pre-heated to 45°C for 10 min and then sealing the polymer solution on the glass support plate by covering it with another pre-heated glass plate. The polymer solution was phase separated at −20°C for 2 hrs and then immersed into ice-water mixture to exchange tetrahydrofuran for 24 hrs. The matrix was washed with distilled water at room temperature for 24 hrs with water changed every 8 hrs. The matrix was then freeze-dried.

The matrices were cut to fit into a 35mm Petri dish and secured in place with a disk of silicone elastomer from Dow Corning (Midland, MI) containing a 1.5mm by 1.5mm opening. The matrices were then sterilized with ethylene oxide and wet with αMEM containing 20% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acid, 0.1mM β mercaptoethanol and 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement for 1hr.

PLLA thin flat (solid) films were fabricated in a similar manner excluding the phase separation step. Instead, the solvent was evaporated at room temperature in a fume hood. The thin flat (solid) films and controls were then treated similarly to the NF matrices. The NF matrices (average fiber diameter of 148nm±21nm(standard deviation)) and films (smooth surface) were previously characterized[12, 19].

Fabrication of NF-PLLA and SW-PLLA Scaffolds

NF-PLLA scaffolds were fabricated as described previously[15, 18]. Briefly, paraffin spheres (diameter = 250–420 μm) were added to Teflon molds, and the top surface was leveled. The molds were preheated at 37°C for 40 min to ensure that paraffin spheres were interconnected. PLLA was dissolved in 4/1 (v/v) dioxane/methanol solvent mixture to make 10% (wt/v) solution and cast onto paraffin sphere assemblies. The polymer/paraffin composite was cooled to −76 °C overnight to phase separate the polymer solution. Hexane was used for solvent extraction and leaching the paraffin spheres for a total of 4 days. Hexane in the scaffolds was then exchanged with cyclohexane. The polymer scaffolds were lyophilized and cut to samples 3.8 mm in diameter and 1.0 mm in thickness.

For comparison, SW PLLA scaffolds were also prepared using a 10% (w/v) PLLA solution in dioxane. The paraffin sphere mold preparation and the polymer casting procedure were performed in the same way as for NF PLLA scaffolds. After PLLA solution casting, the polymer/paraffin composites were dried under low vacuum overnight (about 300 mmHg) and under high vacuum (about 30 mmHg) for 3 days. Paraffin leaching and lyophilizing procedure were performed in the same manner as for NF PLLA scaffolds.

Base on SEM micrographs, both NF and SW scaffolds were calculated to have a porosity of 96.68% ±.05% and a pore interconnectivity of 25.2%±1.9% using perviously described methods[14, 16].

Human Embryonic Stem Cell Culture

The human embryonic stem cell line, BG01, was purchased from Bresagen (Athens, Georgia) and cultured as previously described[1]. The cells were expanded manually on mouse embryonic fibroblasts obtained from the University of Michigan Center for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research, plated at 4 ×105 per 60mm dish in DMEM/F-12 media containing 20% knockout serum replacer, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, 0.1 mM β mercaptoethanol and 4ng/ml FGF2. Media was changed daily.

To induce the formation of embryoid bodies for osteogenic differentiation, cells were manually passaged in small clumps and transferred to non-adhesive plates in DMEM/F-12 media containing 20% knockout serum replacer, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, 0.1 mM β mercaptoethanol, 1 μM dexamethasone, 50 mg/mL ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate. After 2 days of embryoid body formation, 2.5ng/mL of TGF-β1 was added to the media for 3 days. After 5 days of suspension culture, the embryoid bodies were plated onto 0.1% gelatin coated dishes in αMEM containing 20% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, 0.1 mM β mercaptoethanol, 1 μM dexamethasone, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate and 25ng/ml BMP-2. On day 8 of the differentiation protocol, hESC growing on the 0.1% gelatin coated dishes were washed with D-PBS and passaged to tissue culture plates using TrypLE Express stable trypsin replacement enzyme in αMEM containing 20% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, and 2ng/ml FGF2. After 7 days of culture on tissue culture plates, hESC were passaged with tryLE express stable trypsin replacement enzyme and seeded on materials in αMEM containing 20% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acid, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, 0.1 mM β mercaptoethanol, 1 μM dexamethasone, 50 mg/mL ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate. 7.5 × 104 hESC were seeded on thin matrices and films (1.5mm by 1.5mm), while 2.5 × 105 hESC were seeded on scaffolds. For tissue formation on scaffolds, hESC were further expanded to a maxium of passage 5 in αMEM containing 20% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acid, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, and 2ng/ml FGF2. 2.5 × 105 hESC were then seeded on the scaffolds in αMEM containing 20% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% non-essential amino acid, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, 0.1 mM β mercaptoethanol, 1 μM dexamethasone, 50 mg/mL ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate and 50ng/ml of BMP-7. Media was changed every other day throughout the differentiation process.

For blocking studies, 6μg/ml of mouse anti-human integrin alpha 2 monoclonal antibody or purified mouse IgG1 antibody were added to the media after a 48hr attachment period, since alpha 2 integrin was expressed in our seeding population. The media was changed every other day.

Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Mesenchymal-like Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Culture

In order to assess the ability of this protocol to promote osteogenic differentiation, human mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal-like embryonic stem cell derived cells were used. All cell types were seeded to tissue culture plastic at a density of 3.3 × 104 cells per cm2. Human mesenchymal stem cells were obtained from Cambrex (East Rutherford, NJ) and expanded in mesenchymal stem cell growth media.

Mesenchymal-like embryonic stem cell derived cells were obtained as previously described[20]. Briefly, BG01 cells were allowed to form embryoid bodies for 10 days in DMEM/F-12 media containing 20% knockout serum replacer, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1mM glutaMAX-I support supplement, and 0.1 mM β mercaptoethanol. The embryoid bodies were then plated to 0.1% gelatin coated dishes and cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and100 mg/mL streptomycin.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Forty eight hours after cell seeding, the matrices and control were washed with PBS followed by 0.1M cacodylate buffer and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer over night. The cells were washed again with 0.1M cacodylate buffer and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hr. The fixed samples were then dehydrated through an ethanol gradient (50%, 70%, 90%, 95%, and 100%) over 3hrs and dried with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS). Samples were then gold coated and observed using scanning electron microscopy (S-3200, Hitachi, Japan). Cell spreading area was calculated from at least 20 cells per sample in the SEM images using the automated measure function of ImageJ (downloaded from the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, free download available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit with RNase-free DNase set according to the manufacturer’s protocol after thin matrices and scaffolds were mechanically homogenized with a Tissue-Tearor (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) while cells cultured on gelatin-coated tissue culture plate controls were harvested with a cell scraper. The cDNA was made using a Geneamp PCR (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan reverse transcription reagents and 10 min incubation at 25 °C, 30 min reverse transcription at 48 °C, and 5 min inactivation at 95 °C. Real-time PCR was set up using TaqMan Universal PCR Master mix and specific primer sequences for collagen type I, Runx2, osteocalcin, TUJ1 and β actin with 2 min incubation at 50 °C, a 10 min Taq Activation at 95 °C, and 50 cycles of denaturation for 15 s at 95 °C followed by an extension for 1 min at 72 °C on an ABI Prism 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Target genes were normalized against β actin.

5μL of each reaction was subject to PCR using AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) for each of the following: ITGAV (αV) integrin ( 5′-TCGCCGTGGATTTCTTCGT-3′ and 5′-TCGCTCCTGTTTCATCTCAGTTC-3′); ITGA2 (α2) integrin ( 5′-TCCAAGCCTTCAGTGAGAGC-3′ and 5′-ATGTGTATCGATCTCTGCCG-3′); ITGA5 (α5) integrin ( 5′-AGATGAGTTCAGCCGATTCG-3′ and 5′-TGGAAGTCAGGAACAGTGCC-3′); ITGB1 (β1) integrin ( 5′-ACATGGACGCTTACTGCAGG-3′ and 5′-GAACAATTCCAGCAACCACG-3′); ITGB3 (β3) integrin ( 5′-ATTGGCTGGAGGAATGACG-3′ and 5′-AAGACTGCTCCTTCTCCTGG-3′); and β actin ( 5′-ATCTGGCACCACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCG-3′ and 5′-CGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCTGC-3′). The cycling conditions used were 94°C for 5mins followed by 94°C for 30s, 56°C for 60s, 72°C for 60s 40 times for integrin primers, and 94°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 120s 40 times for β actin. These amplifications were followed by a 10min extension at 72°C.

Mineral Quantification

After 6 weeks of culture, scaffolds for mineralization quantification were washed three times for 5 min each in double-distilled water and then homogenized with a Tissue-Tearor in 1 mL of double-distilled water. Samples were then incubated in 0.5 M acetic acid overnight. Total calcium content of each scaffold was determined by o-cresolphthalein-complexone method following the manufacturer’s instructions (Calcium LiquiColor, Stanbio Laboratory, Boerne, Texas).

Collagen Quantification

The collagen content of the cell/scaffold constructs was determined using a colormetric hydroxyproline quantification method [21]. Briefly, scaffolds for collagen quantification were washed three times for 5 min each in double-distilled water and then homogenized with a Tissue-Tearor in 500 μL of double-distilled water. 600 μL of 12N hydrochloric acid was added and the samples were incubated at 100–110°C for 18–24hrs. 10μL methyl red was added and the samples were neutralized to a PH 6–7 with sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid. 320 μL of chloramine T assay solution (211.5mg chloramine T, 12mL Citrate buffer, ph6, 1.5ml isopropanol) was added to 640 μL of the sample, which was placed on an orbital shaker for 20min at 100rpm. 320 μL of dimethylaminobenzaldehyde assay solution (2.250g dimethylaminobenzaldehyde, 9mL isopropanol, 3.9mL 60% perchloric acid) was added and the samples placed at 50°C for 30min. The samples were read at 550nm. Collagen content was estimated assuming a ratio of 1 μg hydroxyproline: 7.46 μg collagen [22].

Immunofluorescence and Histological Staining

The NF matrices, flat (solid) films and controls were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde/PBS, washed, and stored at 4°C in PBS. For histological analysis, scaffolds were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri), dehydrated through an ethanol gradient, and embedded in paraffin. Embedded samples were cut at 5 μm. The paraffin was dissolved with xylene and the sections were rehydrated through an ethanol gradient. The sections were then incubated in 0.5% pepsin for 10min at 30°C for antigen retrieval. Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked by 10% goat serum, then the matrices and control were exposed to TUJ1 (1:250) or osteocalcin (1:50) antibodies, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC (TUJ1) or TRITC (ostoecalcin). DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei.

For Alizarin Red S staining, the matrices, controls, and scaffold sections were fixed by the same method and then stained with 40mM Alizarin Red S solution, pH 4.2 at room temperature for 10min. Thin matrices and controls were then rinsed 5 times in distilled water and washed 3 times in PBS on an orbital shaker at 40rpm for 5 min each to reduce nonspecific binding. Scaffold sections were dehydrated in acetone and rinsed in xylene before mounting with Permamount. Scaffold sections were also stained with hematoxylin and eosin-phloxine and von Kossa.

Protein Adsorption Analysis

Scaffolds were treated with ethanol and PBS in the same way described above for cell culture. Scaffolds were incubated with cell culture medium or FBS for 4 hours. Scaffolds were quickly washed with PBS for 2 times, cut into pieces and transferred to 1.5ml tubes. 600μl of PBS was added and the scaffolds were washed three times. PBS was removed, and the scaffolds were centrifuged for 1min at 12,000rpm for 2 times to remove any liquid remained. 25μl 1% SDS was added and incubated for 1hr. This was repeated twice. A total of 75μl was pooled to form the collection sample. For microBCA (Pierce, Rockford, IL), 50ul of the collection sample was used (n=3), while 30 μl of the collection sample was used for each gel. Western blot analysis was conducted as previously described[23]. Briefly, the recovered serum protein samples were subject to fractionation through 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The fractionated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Sigma). The blots were washed with TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 8.0), and blocked with Blotto (5% nonfat milk in TBST) at room temperature for 1 h. The blots were incubated in anti-bovine fibronectin polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST, the blots were incubated in anti-goat immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Sigma), and then in chemiluminescence reagent (SuperSignal West Dura; Pierce). The relative densities of the protein bands were analyzed with Quality One (Biorad).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted at least 3 times. All quantifiable data is reported with the mean and standard deviation. Student T tests were conducted where appropriate to determine significance. Significance was set as a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

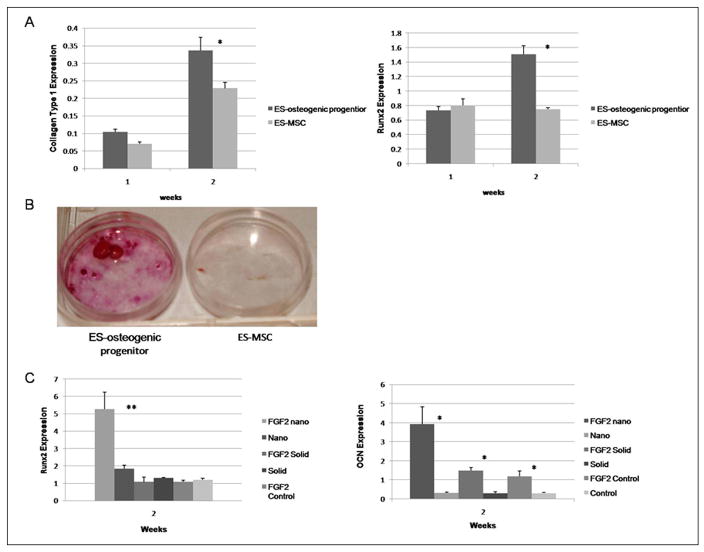

A number of protocols have been developed to generate osteogenic cells from hESC[4–7]. For our study, we derived an osteogenic population through embryoid body formation and plating in the presence of osteogenic supplements (ascorbic acid, β-glycerol phosphate and dexamethasone) and the sequential administration of growth factors (TGF-β1, BMP2, and FGF2) over fifteen days. Another possible approach to generate osteoblasts from hESC is to first generate mesenchymal-like stem cell population and differentiate them toward the osteogenic lineage over a longer time[20, 24, 25]. In Figure 1, we compare the osteogenic potential of cells generated from our approach and a published hESC-derived mesenchymal-like stem cell protocol[20]. After two weeks of culture under osteogenic conditions, expression of transcripts for type I collagen and Runx2 was observed in our hESC derived osteogenic progenitors at a level similar to human mesenchymal stem cells (data not shown) and higher than in the hESC-derived mesenchymal-like stem cells (Figure 1A). After 3 weeks of osteogenic culture our hESC derived osteogenic progenitors also showed increased mineralization compared to the hESC-derived mesenchymal-like stem cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the osteogenic potential of hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells and hESC derived mesenchymal cells. (A) Quantitative PCR collagen type 1 and Runx2 after 2 weeks of osteogenic differentiation. Expression levels were normalized to β actin. * denotes p-value <0.05; (B) Alizarin red staining of hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells and hESC derived mesenchymal cells after 3 weeks of osteogenic differentiation; (C) Quantitative PCR expression of osteogenic markers by hESC derived osteogenic progenitors with and without bFGF supplementation prior to seeding on nanofibrous matrices (nano), flat films (solid) and 0.1% glelatin coated tissue culture plastic (control). Expression levels were normalized to β actin. * denotes p-value <0.05. ** denotes p-value <0.01.

The effects of FGF2 supplementation after BMP-2 supplementation were examined. The osteogenic potential of hESC derived osteogenic progenitors with and without the FGF2 supplementation was studied (Figure 1C). The FGF2 supplementation increased the osteocalcin expression of hESC derived osteogenic progenitors on all of our test substrate architectures (NF, solid, and control −0.1% gelatin-coated tissue culture plastic) compared to hESC derived osteogenic progenitors which were not exposed to FGF2 supplementation cultured on the same surface. The increased expression of Runx2 on the NF matrix with FGF2 supplementation compared to that without FGF2 was also observed. This indicates that the FGF2 treatment enhances the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells further differentiation toward the osteoblastic lineage.

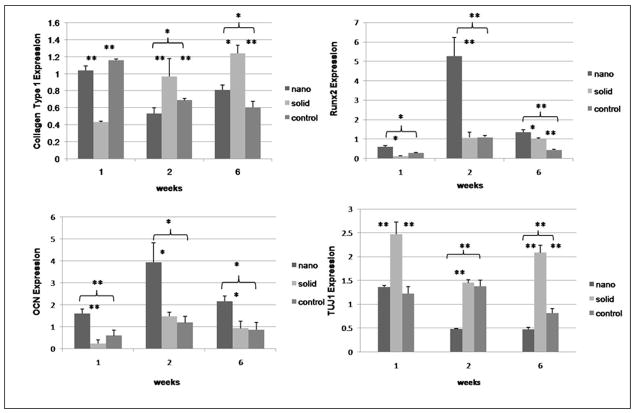

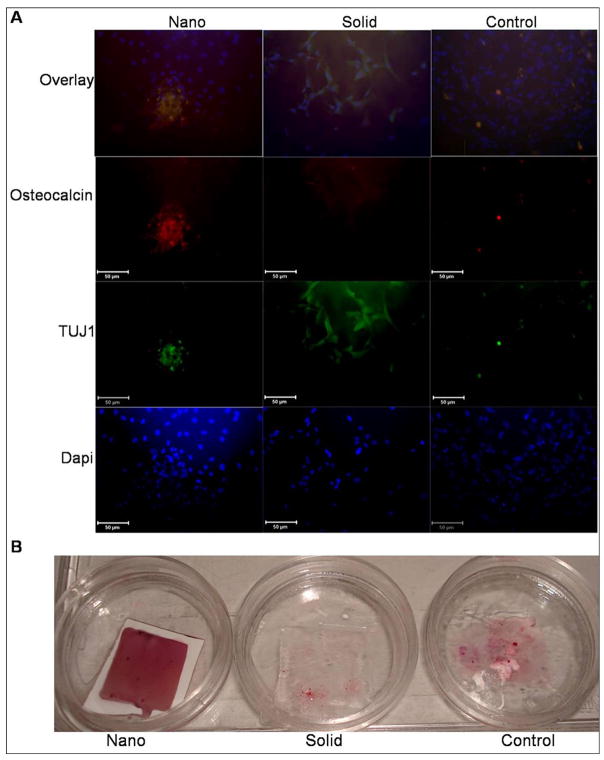

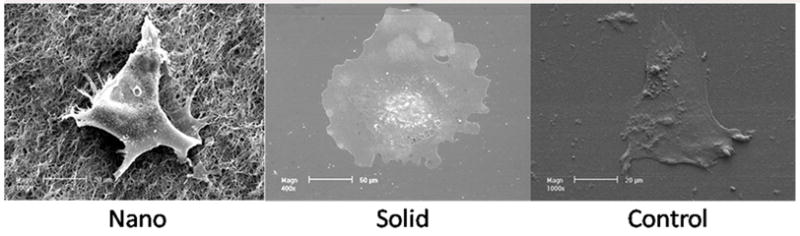

SEM was used to examine the morphology of the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells after 48hrs of osteogenic culture on the thin matrices and films (Figure 2). hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on the NF matrix were less spread (1490±188μm2 reported as average cell area± standard deviation) with more processes interacting with the nanofibers on the flat (solid) films (4891±1204 μm2*,* indicates a p value <0.05 compared to the NF matrix) or control (2840±167 μm2*). This is consistent with other reports of cellular morphology on NF materials either using phase separation or electrospinning [19, 26–28]. Next osteogenic and neuronal differentiation was examined over time (Figure 3). hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells cultured on the NF matrix expressed higher levels of osteogenic markers (Runx2 and osteocalcin) and reduced level of neuronal marker TUJ1 compared to flat (solid) films and control at all time points. hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on the NF matrix expressed increased levels of collagen type I after 1 week of osteogenic culture compared to flat (solid) films. These cells expressed reduced levels of collagen type I at both 2 and 6 weeks compared to hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on the flat (solid) film. This change in the relative expression of collagen type I could be due to a more quickly maturing ECM and a reduced need for new collagen type 1 on the NF matrix than on the flat (solid) film. This is supplemented by increased osteocalcin staining (Figure 4A) after 2 weeks and increased calcium staining (Figure 4B) after 3 weeks of osteogenic culture of the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on NF matrix compared to the cells grown on the flat (solid) film and control surface.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of hESC derived osteo progenitor cells after 48 hrs of culture under osteogenic differentiation conditions on nanofibrous thin matrix (Nano), flat films (Solid), gelatin coated tissue culture plastic (Control), Scale bar =20μm (Nano & Control), 50 μm (Solid).

Figure 3.

Expression of markers of osteogenic and neuronal differentiation over time under osteogenic differentiation conditions on nanofibrous matrices (nano), flat films (solid) and 0.1% gelatin coated tissue culture plastic (control) using quantitative PCR for (A) Collagen type 1, (B) Runx2, (C) osteocalcin, and (D) TUJ1. * denotes p-value <0.05. ** denotes p-value <0.01.

Figure 4.

(A) Immunofluorescence localization of neuronal (TUJ1) and late bone differentiation (Osteocalcin) markers after 2 weeks culture under osteogenic differentiation conditions on nanofibrous matrix (Nano), flat films (Solid) and gelatin coated tissue culture plastic (Control). Scale bar =50μm. (B) Calcium staining after 3 weeks under osteogenic differentiation conditions on nanofibrous matrix (Nano), flat films (Solid) and gelatin coated tissue culture plastic (Control).

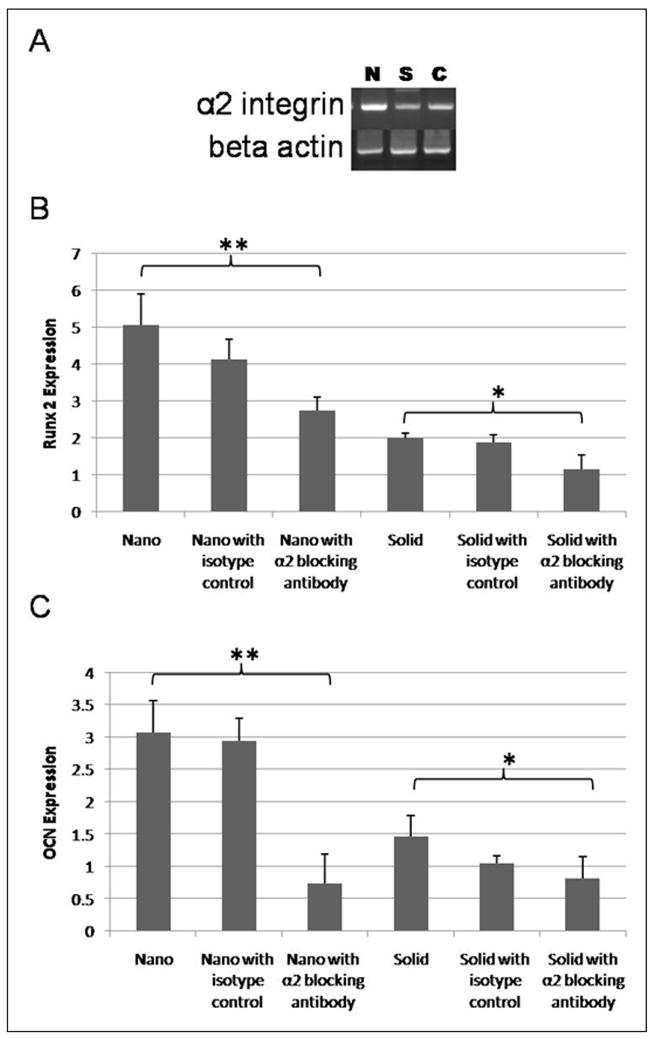

Differences in integrin expression by cells cultured on NF materials compared to solid materials have been observed previously[12, 26]. The expression of αV, α2, α5, β1, and β3 integrins were examined in the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on the NF matrix and flat (solid) films. After 2 weeks of osteogenic culture, α2 integrin was differently expressed (Figure 5A) and when cells were exposed to α2 integrin antibodies decreased Runx2 and osteocalcin expression was observed on both NF matrix and flat (solid) films (Figure 5B and 5C). As α2 integrin expression is considered necessary for osteogenic differentiation[29, 30], the observed effect on cellular differentiation is not a surprise.

Figure 5.

Effects of integrin blocking on osteogenic differentiation after 2 weeks of differentiation. (A) PCR of expression of α2 integrin on nanofibrous matrix (N), flat (solid) films (S) and 0.1% gelatin coated tissue culture plastic (C); (B) quantitiative PCR of expression of Runx2 on nanofibrous matrix (Nano), on nanofibrous matrix with control IGG isotype (Nano with isotype control), on nanofibrous matrix with mouse anti-human integrin alpha 2 monoclonal antibody (α2 blocking nano), on flat films (Solid), on flat films with control IGG isotype (solid with isotype control), and on flat films with mouse anti-human integrin alpha 2 monoclonal antibody (α2 blocking solid). * denotes p-value <0.05. ** denotes p-value <0.01. (C) quantitiative PCR of expression of osteocalcin on nanofibrous matrix (Nano), on nanofibrous matrix with control IGG isotype (Nano with isotype control), on nanofibrous matrix with mouse anti-human integrin alpha 2 monoclonal antibody (α2 blocking nano), on flat films (Solid), on flat films with control IGG isotype (solid with isotype control), and on flat films with mouse anti-human integrin alpha 2 monoclonal antibody (α2 blocking solid). * denotes p-value <0.05. ** denotes p-value <0.01.

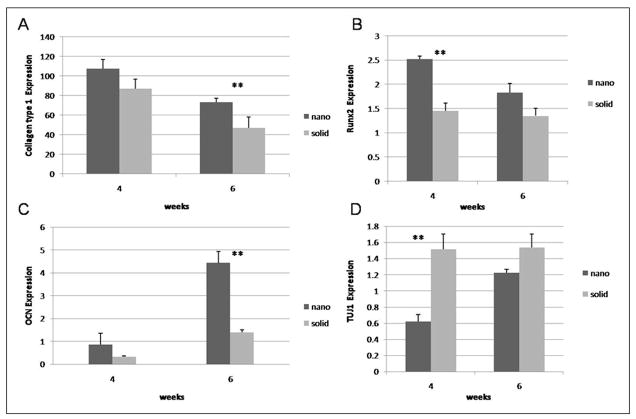

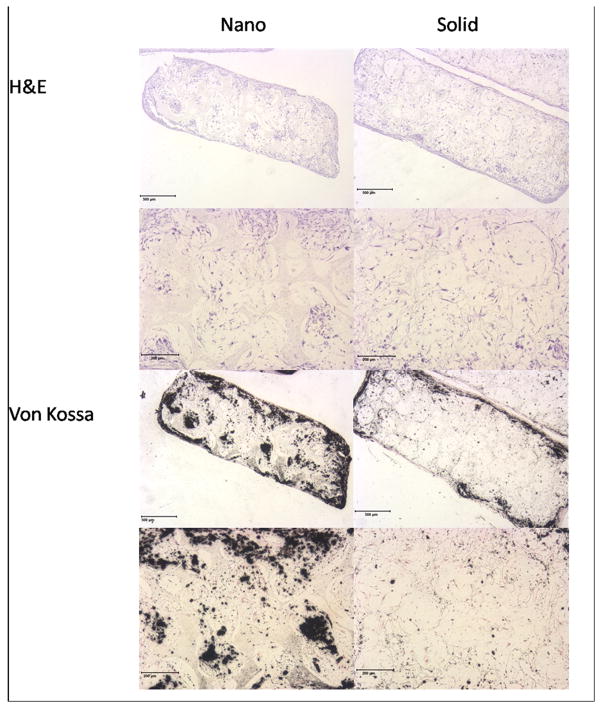

Next, differentiation (Figure 6) and histological organization (Figure 7) were examined on 3-D NF and SW scaffolds. After 4 weeks of culture, hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on NF scaffolds were found to express increased levels of Runx2 and reduced levels of TUJ1 compared to SW scaffolds. After 6 weeks of culture hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on NF scaffolds were found to express increased levels of collagen type I and osteocalcin compared to SW scaffolds. Cells grown on 3D NF scaffolds continue to express higher levels of collagen type I at later time points than those on the SW scaffolds could be due to a insufficient number of cells within the NF scaffold to produce the needed proteins for ECM maturation. Histology of the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on the NF scaffolds shows increased cellular organization and mineralization compared to the SW scaffold (data not shown) after 6 weeks of osteogenic culture. The addition of BMP-7 to the osteogenic media increased the mineralization and the cellular orgranization within both scaffolds (Figure 8). However, the NF scaffolds still showed increased mineralization compared to the SW scaffold.

Figure 6.

Quantitative PCR analysis of (A) Collagen type 1 (B) Runx2 (C) osteocalcin and (D) TUJ1 over time under osteogenic differentiation conditions on nanofibrous scaffolds (nano), and solid-walled scaffolds(solid). ** denotes p-value <0.01.

Figure 7.

(A) Histology of cellular (H&E) and calcium (Von Kossa) staining of the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells after 6 weeks of culture on nanofibrous (Nano) and solid-walled (Solid) scaffolds. Scale bar = 500 μm (overview), 200μm (high magnification).

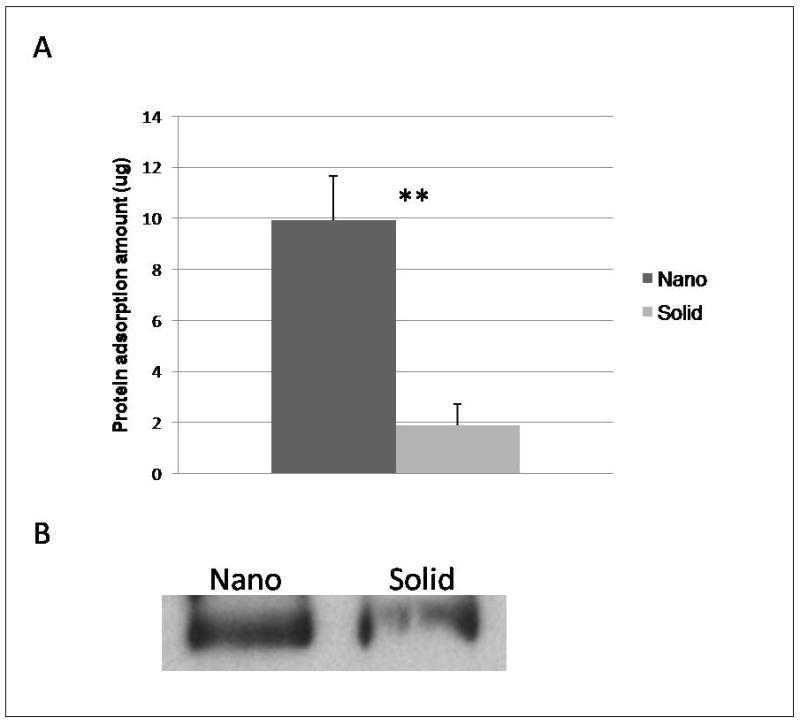

Figure 8.

Protein adsorption to scaffolds after exposure to medium containing bovine serum protein or fetal bovine serum for 4 hr: (A) Amount of adsorbed proteins (MicroBCA assay) from nanofibrous scaffolds (Nano) and solid-walled scaffolds (Solid) treated with media. ** denotes a p-value < 0.01. (B) western blot of fibronectin extracted from nanofibrous scaffolds (Nano) and solid-walled scaffolds (Solid) cultured in fetal bovine serum for 4hr.

Differences in the initial microenvironment created by protein adsorption from the medium could be contributing to the increased differenitation and histological organization of the cells on the scaffolds. Previous studies have found the profile and amount of total protein to differ on NF and solid materials[12, 18]. In this study, the NF scaffolds were found to adsorb significantly more protein from the media than the SW scaffolds (Figure 8A). Fibronectin is an important ECM protein during early osteogenesis [31, 32]. However, NF scaffolds exposed to fetal bovine serum were shown to adsorb more fibronectin than similarly treated solid scaffolds (Figure 8B).

5.4 Discussion

hESC represent a potentially unlimited source of cells for tissue engineering applications. However, best practices for their controlled differentiation have yet to be established. hESC exposed to osteogenic culture conditions prior to implantation more selectively differentiated to bone over other mesenchymal lineages (cartilage and fat)[33] indicating that hESC can maintain their induced lineage in vivo.

In this study, growth factors where added sequentially to emulate their varied expression during osteogenesis[34, 35]. Additionally, previous studies with hESC have shown that TGF-β1 promotes mesodermal [36] and chondrogenic [37] differentiation, while BMP-2 increases both chondrogenesis [38] and osteogenesis[9]. FGF2, on the other hand, increases the number of osteogenic precursor cells[39, 40]. Sequential administration of growth factors leads to the development of osteogenic progenitors which have greater osteogenic potential than mesenchymally differentiated hESC (Figure 1). The progenitor population was then used to examine the effects of NF architecture in 2-D and 3-D on hESC osteogenic differentiation.

Although FGF2 has been shown to have a negative effect on late osteogenic differentiation and mature osteoblast cell survival[41], in our study the cell population treated with FGF2 had greater osteogenic potential on the materials than hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells not receiving FGF2 stimulation (Figure 1C). This increased osteogenic potential may be due to maintenance of increased proliferative capacity after FGF2 treatment. The increased number of cells could enhance cell-cell interactions or signalling which may promote their increased differentiation. However, given that the objective of this study was to examine the effects of scaffold wall architecture on differentiation and tissue formation, the mechanism by which FGF2 increases the osteogenic potential of the cell population is outside the scope of this study but may be of considerable importance to be investigated in future studies.

Increased expression of many osteogenic markers was observed in hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells on the NF thin matrix and 3D scaffold compared to the flat (solid) film and the SW scaffold. However, there was inconsistency between the 2-D and 3-D culture in terms of the long term expression of collagen type I. Changes in cell density or differences in cell interactions between 2-D and 3-D cultures may explain this discrepancy in that numerous cell types have been shown to respond differently to 2-D and 3-D culture[42–44].

Interactions between type I collagen and α2β1 integrin have been linked to the expression of genes associated with the osteogenic phenotype[29, 30]. Increased expression of α2 integrin has been previously observed in neo-natal osteoblasts on NF materials compared to solid materials[26]. In this study, increased expression of the α2 integrin was observed in hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on the NF matrix compared to hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on flat (solid) films (Figure 3A). This improved integrin expression was then linked to osteogenic differentiation by finding the decreased expression of osteogenic markers when α2 integrin antibodies were added to the culture (Figure 3B and 3C).

A previous study showed that NF scaffolds adsorbed increased levels of serum proteins and in a different profile from SW scaffolds[18]. The profile of the proteins as well as the increased amount of protein adsorbed on the NF materials compared to the SW materials may lead to a preferential niche for osteogenic differentiation of the hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells. Additionally, the proteins on the NF materials may have a different conformation then those on the solid material allowing them to further stimulate cellular differentiation as nanoscale features have been found to affect the supramolecular organization [45, 46] and activity[47] of adsorbed proteins.

The NF architecture itself could also be responsible for the observed differences in differentiation by directly influencing cell behavior. Previous studies showed that osteoblasts on NF scaffolds did not alter their α2β1 integrin expression when collagen fibril formation was blocked[26]. Pre-osteoblasts on the NF matrix did not alter their cytoskeleton structure (in terms of stress fiber or focal adhesion formation) when the NF matrix surface chemistry was modified and the enhanced bone sialoprotein expression was correlated to RhoA/Rock signaling pahtway [19].

Further refinement of the cellular differentiation process, culture conditions and scaffold design will be necessary to form functional 3-D bone tissue. For instance, it has been suggested that mouse embryonic stem cells require the formation of a cartilage template in order to form bone tissue[48]. This may also be the case for hESC. However, further testing is necessary to determine the optimal strategy to utilize hESC for bone tissue engineering applications. As the NF scaffold contained more osteogenically differentiated cells and more organized tissue than the SW scaffold, the NF scaffold may provide the superior microenvironment for bone tissue engineering.

Conclusions

NF architecture in both 2-D and 3-D enhances the osteogenic differentiation of hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells compared to flat surfaces. In 2-D culture, hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on the NF matrix are morphologically different compared to cells cultured on flat (solid) films or control. hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on the NF matrix exhibit increased expression of α2 integrin compared to flat (solid) films, which was linked to the expression of the osteogenic markers Runx2 and osteocalcin. Increased expression of collagen type I, Runx2 and osteocalcin and mineralization of the matrix were observed in hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on NF matrices and scaffolds compared to hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on flat (solid) films and SW scaffolds. hESC derived osteogenic progenitor cells grown on NF scaffolds also produced a more organized and minerialized tissue than cells grown on SW scaffolds.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. K. Sue O’Shea and Renny Franceschi for critical discussions. This research was partially supported by Michigan Center for hES Cell Research (NIH P20GM069985, Pilot PI: PXM), the NIH (NIDCR DE017689 & DE015384: PXM). LAS was supported by NSF Graduate Student Fellowship and NIH training grant in tissue engineering and regeneration (DE07057).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehrer C, Lepperdinger G. Mesenchymal stem cell aging. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:926–930. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muraglia A, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Clonal mesenchymal progenitors from human bone marrow differentiate in vitro according to a hierarchical model. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1161–1166. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sottile V, Thomson A, McWhir J. In vitro osteogenic differentiaiton of human ES cells. Cloning Stem Cells. 2003;5:149–155. doi: 10.1089/153623003322234759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao T, Heng BC, Ye CP, Liu H, Toh WS, Robson P, et al. Osteogenic differentiation within intact human embryoid bodies result in a marked increased in osteocalcin secretion after 12 days of in vitro culture, and formation of morpholoigcally distinct nodule-like structures. Tissue Cell. 2005;37:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karp JM, Ferreira LS, Khademhosseini A, Kwon AH, Yeh J, Langer RS. Cultivation of human embryonic stem cells without the embroid body step enhances osteogenesis in vitro. Stem Cells. 2006;24:835–843. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bielby R, Boccaccini A, Polak J, Buttery L. In vitro differentiation and in vivo mineralization of osteogenic cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:18–25. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspi O, Lesman A, Basevitch Y, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Habib IH, et al. Tissue engineering of vascularized cardiac muscle from human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:263–272. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257776.05673.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S, Kim SS, Lee SH, Ahn SE, Gwak SJ, Song JH, et al. In vivo bone formation from human embryonic stem cell-derived osteogenic cells in poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levenberg S, Huang NF, Lavik E, Rogers AB, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer RS. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on three-dimensional polymer scaffolds. Proc Natl Sci USA. 2003;100:12741–12746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735463100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith LA, Liu X, Hu J, Ma PX. The influence of three-dimensional nanofibrous scaffolds on the osteogenic differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2516–2522. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith LA, Liu X, Hu J, Wang P, Ma PX. Enhancing Osteogenic Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells by Nanofibers. Tissue Engineering Part A. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0227. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsdale T, Bard J. Collagen substrata for studies on cell behavior. J Cell Biol. 1972;54:626–637. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.3.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma PX, Zhang R. Synthetic nano-scale fibrous extraellular matrix. Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46:60–72. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<60::aid-jbm7>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen VJ, Ma PX. Poly(L-lactic acid) scaffolds with interconnected spherical macropores. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2065–2073. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang R, Ma PX. Synthetic nano-fibrillar extracellular matrices with predesigned macroporous architectures. J Biomedi Res. 2000;52:430–438. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<430::aid-jbm25>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen VJ, Smith LA, Ma PX. Bone regeneration on computer-designed nano-fibrous scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3973–3979. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo KM, Chen VJ, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous scaffolding architecture selectively enhances protein adsorption contributing to cell attachment. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;67A:531–537. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Liu X, Ma PX. Induction of osteoblast differentiation phenotype on poly(L-lactic acid) nanofibrous matrix. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3815–3821. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang NS, Varghese S, Zhang Z, Elisseeff J. Chondrogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cells in arginine-glycine-aspartate-modified hydrogels. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2695–2706. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woessner JF. The determination of hydroxyproline in tissue and protein samples containing small proportions of this imino acid. Arch of Biochem Biophys. 1961;93:440–447. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuman R, Logan M. The determination of collagen and elastin in tissues. J Biol Chem. 1950;186:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woo KM, Chen VJ, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous scaffolding architecture selectively enhances protein adsoption contributing to cell attachement. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;67A:531–537. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lian Q, Lye E, Suan Yeo K, Khia Way Tan E, Salto-Tellez M, Liu T, et al. Derivation of clinically compliant MSCs from CD105+, CD24− differentiated human ESCs. Stem Cells. 2007;25:425–436. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barberi T, Willis L, Socci N, Studer L. Derivation of multipotent mesenchymal precursors from human embryonic stem cells. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woo K, Jun J, Chen V, Seo J, Baek J, Ryoo H, et al. Nano-fibrous scaffolding promotes osteoblast differentiation and biomineralization. Biomaterals. 2007;28:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shih YV, Chen CN, Tsai SW, Wang YJ, Lee OK. Growth of mesenchymal stem cells on electrospun type I collagen nanofibers. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2391–2397. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schindler M, Ahmed I, Kamal J, Nur-E-Kamal A, Grafe TH, Chung HY, et al. A synthetic nanofibrillar matrix promotes in vivo-like organization and morphogenesis for cells in culture. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5624–5631. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao G, Wang D, Benson D, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT. Role of the a2-Integrin osteoblast-specific gene expression and activation of the OSF2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32988–32994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizuno M, Fujisawa R, Kuboki Y. Type I collagen-induced osteoblastic differentiation of bone-marrow cells mediated by collagen-alpha2beta1 integrin interaction. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:207–213. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200008)184:2<207::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss R, Reddi A. Role of fibronectin in collagenous matrix-induced mesenchymal cell proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 1981;133:247–254. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(81)90316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowles E, DeRome M, Pastizzo G, Brailey L, Gronowicz G. Mineralization and the expression of the matrix proteins during in vivo bone development. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;62:74–82. doi: 10.1007/s002239900397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremoleda J, Forsyth N, Khan N, Wojtacha D, Christodoulou I, Tye B, et al. Bone tissue formation from human embryonic stem cells in vivo. Cloning Stem Cells. 2008;10:119–132. doi: 10.1089/clo.2007.0R36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Z, Nelson ER, Smith R, Goodman S. The sequenital expression profiles of growth factors from osteoprogenitors to osteoblasts in vitro. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2311–2320. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhary L, Hofmeister A, Hruska K. Differential growth factor control of bone formation through osteoprogenitor differentiation. Bone. 2004;34:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuldiner M, Yanuka O, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Melton D, Benvenisty N. Effects of eight growth factors on the differentiation of cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11307–11312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang NS, Varghese S, Elisseeff J. Derivation of chondrogenically-committed cells from human embryonic cells for cartilage tissue regeneration. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toh WS, Yang Z, Liu H, Heng BC, Lee E, Cao T. Effects of culture conditions and bone morphogenetic protein 2 on extent of chondrogenesis from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:950–960. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Debiais F, Hott M, Graulet A, Marie P. The effects of fibroblast growth factor-2 on human neonatal calvaria osteoblastic cells are differentiation stage specific. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:645–654. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin I, Muraglia A, Campanile G, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Fibroblast growth factor-2 aupports ex vivo expansion and maintenance of osteogenic prescursors from human bone marrow. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4456–4462. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansukhani A, Ambrosetti D, Holmes G, Cornivelli L, Basilico C. Sox2 induction by FGF and FGFR2 activating mutations inhibits Wnt signaling and osteoblast differentiation. JCB. 2005;168:1065–1076. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baharvand H, Hashemi S, Ashtian S, Farrokhi A. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes in 2D and 3D culture systems in vitro. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:45–652. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052072hb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen S, Revoltella R, Papini S, Michelini M, Fitzgerald W, Zimmerberg J, et al. Multilineage differentiation of rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells in three-dimensional culture systems. Stem Cells. 2003;21:281–295. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-3-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens D, Yamada K. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roach P, Farrar D, Perry C. Surface tailoring for controlled protein adsorption: effect of topography at the nanometer scale and chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3939–3945. doi: 10.1021/ja056278e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denis F, Hanarp P, Sutherland D, Gold J, Mustin C, Rouxhet P, et al. Protein adsorption on model surfaces with controlled nanotopography and chemistry. Langmuir. 2002;18:819–828. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutherland D, Broberg M, Nygren H, Kasemo B. Influence of nanoscale surface topography and chemistry on the functional behaviour of an adsorbed model macromolecule. Macromol Biosci. 2001;1:270–273. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jukes J, Both S, Leusink A, Sterk L, van Blitterswijk C, de Boer J. Endochondral bone tissue engineering using embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Sci USA. 2008;105:6840–6845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711662105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]