Abstract

Lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) proteins, p75 and p52, are transcriptional co-activators that connect sequence-specific activators to the basal transcription machinery. We have found that these proteins are post translationally modified by the Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO)-1 and SUMO-3. Three SUMOylation sites, K75, K250 and K254, were mapped in the shared N-terminal region of these molecules, while a fourth site, K364, was identified in the C-terminal part exclusive of LEDGF/p75. The N-terminal SUMO targets are located in evolutionarily conserved charge-rich regions that lack resemblance to the described consensus SUMOylation motif, whereas the C-terminal SUMO target is solvent-exposed and situated in a typical consensus motif. SUMOylation did not affect the cellular localization of LEDGF proteins and was not necessary for their chromatin-binding ability, nor did it affect this activity. However, lysine to arginine mutations of the identified SUMO acceptor sites drastically inhibited LEDGF SUMOylation, extended the half-life of LEDGF/p75 and significantly increased its transcriptional activity on the Heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) promoter, indicating a negative effect of SUMOylation on the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75. Considering that SUMOylation is known to negatively affect the transcriptional activity of all transcription factors known to transactivate Hsp27 expression, these findings support the paradigm establishing SUMOylation as a global neutralizer of cellular processes upregulated upon cellular stress.

Keywords: Lens epithelium-derived growth factor, Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier, Heat shock protein 27 promoter, transcriptional regulation and post-translational modifications

Introduction

LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 are generated from alternatively spliced products of the human PSIP1 gene and share an N-terminal region composed of 325 amino acid residues. The unique C-terminal regions are 8 amino acids long in LEDGF/p52 and 205 amino acids long in LEDGF/p75 1; 2; 3.

LEDGF proteins are tightly bound to chromatin during all the phases of the cell cycle 4; 5; 6. Chromatin binding is mediated by the functional interaction of the PWWP domain, the nuclear localization signal and two AT hook motifs located in the shared N-terminal region 4; 6; 7. The chromatin binding activity of LEDGF proteins is central in their role in transcription 8. Chromatin-bound LEDGF proteins act as molecular tethers that connect sequence-specific activators to the basal transcription machinery or transcriptional regulators 1; 8; 9. The chromatin tethering activity of LEDGF/p75 is exploited by HIV-1 during viral DNA integration, an essential step in its life cycle 10; 11. Chromatin-bound LEDGF/p75 interacts with the viral integrase through its C-terminal integrase binding domain (IBD)12; 13, tethering the HIV-1 pre-integration complex to the host chromatin14; 15. This event significantly facilitates HIV-1 infection10; 11.

A transcriptional regulatory role of LEDGF proteins in the expression of genes implicated in the cellular response to environmental stress has been extensively reported. Over-expression of LEDGF/p75 was found to augment transcription of a set of stress-related genes including Hsp27 2; 16; 17; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22, αB-crystallin 20; 23, antioxidant protein 2A and involucrin 24. In all cases, increased levels of LEDGF/p75 induced the expression of these endogenous proteins as well as reporter genes introduced under the control of the homonymous promoters. The transcriptional regulation of these genes was proposed to be mediated by the binding of LEDGF/p75 to stress-related elements and heat shock elements (HSE) situated in the promoter regions 18; 19; 21; 24.

The regulation of heat shock proteins expression is critical for the survival of normal and cancer cells during stress. Several cellular stresses that trigger the expression of heat shock proteins also markedly increase global cellular SUMOylation 25. It is well established that SUMOylation of transcriptional regulators generally increases their transcriptional repressive activities (Reviewed in 26; 27; 28) Therefore, SUMOylation could potentially provide a mechanism to downregulate to their basal levels the expression of heat shock proteins after their upregulation during stress. A similar role has been proposed for SUMOylation in the regulation of genes activated during the Interferon response 29; 30; 31.

SUMOylation is the reversible conjugation of the SUMO protein to the e-amino group of a lysine residue 27; 28. Three SUMO isoforms, 1–3, are well accepted to be covalently attached to substrates. SUMO-2 and -3 are 98% identical but exhibit only ~50% identity with SUMO-1. Although SUMOylation is enzymatically similar to ubiquitination, it requires a different set of enzymes. The SUMO-activating enzyme, SAE1/SAE2, activates SUMO in an ATP-dependent manner. Activated SUMO is then transferred to the SUMO-conjugating enzyme, UBC9, which mediates conjugation of SUMO to an exposed lysine residue in the target protein. SUMOylation is enhanced by SUMO ligases, a diverse group of proteins that stabilize and direct the interaction between UBC9 and its SUMOylation targets. Upon conjugation, SUMO can be efficiently removed from its targets by SUMO proteases, resulting in very low steady state levels of the SUMO-modified forms for most SUMO targets 32.

The Hsp27 promoter is modulated by different transcriptional regulators including the transcription factors heat shock transcription factor 1 (Hsf-1), Sp1, and AP-2 and the co-activators LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75 33. SUMOylation of all these transcriptional regulators, except the LEDGF proteins, has been described to modulate their transcriptional activity. SUMO-1 and SUMO-2/SUMO-3 modification of Hsf-1 at residue K298 was reported to differentially influence its activity on the Hsp27 promoter. SUMO-1 conjugation increased Hsf-1-mediated transcription 34 while SUMO-2/SUMO-3 repressed it 35. Conjugation of SUMO-2/SUMO-3 to Hsf-1 was shown to be facilitated by Hsp27 during thermal stress 35. In addition, SUMO-1 modification negatively affected the activity of the transcription factors Sp1 36; 37 and AP-2 38.

Based in the described regulatory role of SUMOylation in the Hsp27 promoter activity, we decided to evaluate whether LEDGF proteins are SUMO targets. These proteins are likely to be SUMOylated since lysine is their most represented amino acid (~16%). Results obtained in this study demonstrated that LEDGF proteins are SUMO-targets in vivo. Four lysine residues were identified as the SUMOylation sites in LEDGF proteins. Mutation of these lysine residues to arginine drastically impaired LEDGF SUMOylation, extended the half-life of LEDGF/p75 and enhanced the transcriptional activity of this protein on the Hsp27 promoter. These findings suggest that SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 modulates its role in transcriptional activation and add further support to a negative transcriptional regulatory role of SUMOylation in the expression of Hsp27.

Results

LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 are targeted by the SUMOylation pathway

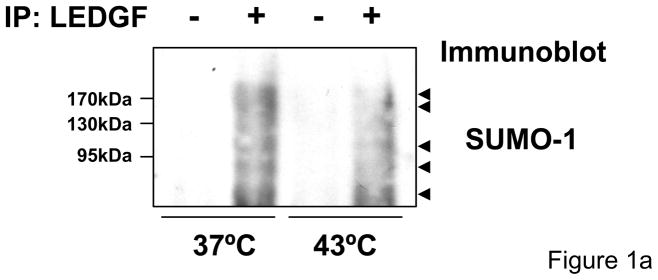

To evaluate whether LEDGF/p75 is SUMOylated in vivo, this protein was immunoprecipitated from LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T (si1340/1428) cells 15 stably expressing LEDGF/p75 WT that were subjected or not to heat shock (43°C) for 1 hr. The immunoprecipitated proteins were then analyzed for the presence of SUMO-1 modified proteins by immunobloting with a SUMO-1 antibody (Fig. 1a). Several bands were observed in both non-heat-shocked and heat-shocked cells. The intensity of these bands was considerably higher in non-heat-shocked cells.

Figure 1.

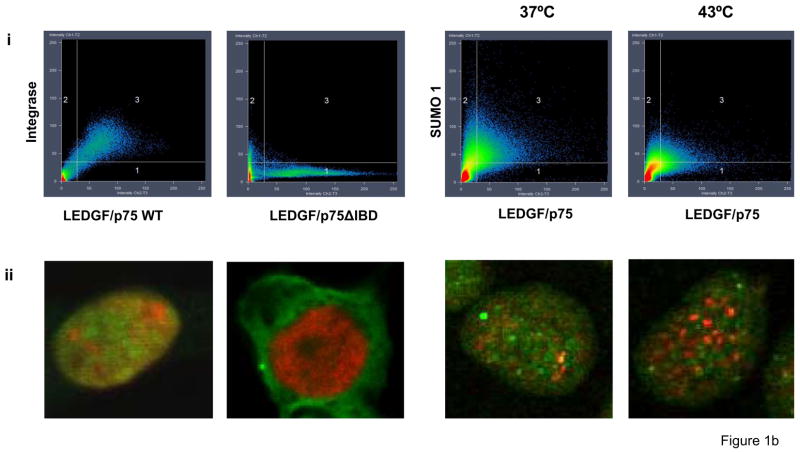

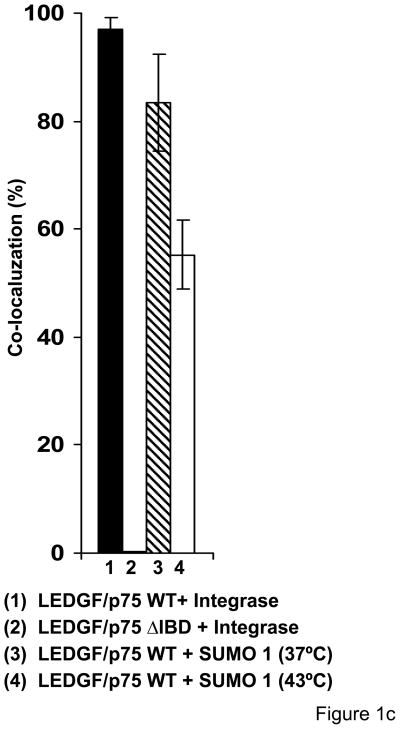

LEDGF/p75 associates with SUMO-1. (a) LEDGF/p75 was immunoprecipitated and the presence of SUMO-1-modified proteins was determined by immunoblotting with anti-SUMO-1 antibody. Several high molecular weight bands were identified in immunoprecipitated samples. (b) Co-localization of LEDGF/p75 and SUMO-1 assessed by confocal microscopy. Co-localization of LEDGF/p75 WT or ΔIBD with HIV-1 integrase were used as controls. (i) Two-color histograms representing the red (LEDGF/p75) and green fluorescence (SUMO-1 or HIV-1 Integrase) intensity in all the immunostained cells (ii) Representative images of data in panel (i) are shown. Co-localization of LEDGF/p75WT and SUMO-1 in HeLa cells subjected (43°C) or not to heat-shock (37°C) are also represented (i and ii) (c) Quantification of the co-localization experiments shown in figure 1b-i.

The association of LEDGF/p75 with SUMO-1 within intact cells was assessed by confocal microscopy. To develop a quantitative co-localization assay, we considered the co-localization of LEDGF/p75 WT or a LEDGF/p75 mutant lacking the integrase binding domain (IBD) and HIV-1 integrase as positive and negative controls, respectively. LEDGF/p75 and integrase have been extensively described to tightly interact during all the phases of the cell cycle 14; 15. In addition, deletion of the IBD domain is known to abolish this interaction12; 39. Plasmids encoding LEDGF/p75 WT or LEDGF/p75 ΔIBD were transiently transfected into LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T cells stably expressing eGFP-tagged HIV-1 integrase (2LKD-IN-eGFP cells)40. These cells were immunostained for LEDGF/p75 (red) with specific antibodies. We observed 96.95% of co-localization between HIV-1 integrase and LEDGF/p75 WT. As expected, the co-localization coefficient was decreased to 0.26% in cells expressing the LEDGF/p75 ΔIBD mutant (Fig. 1b and 1c). Using this methodology, we evaluated the co-localization of LEDGF/p75 with SUMO-1 in HeLa cells that were subjected or not to heat shock (Fig. 1b). In agreement with the immunoprecipitation data in figure 1a, LEDGF/p75 and SUMO-1 presented a co-localization coefficient of 83.49% that was reduced to 55.22% upon heat shock.

In summary, data in figure 1 indicate that a fraction of LEDGF/p75 is conjugated to SUMO-1 under physiological conditions and the levels of SUMOylated LEDGF/p75 are decreased following heat shock.

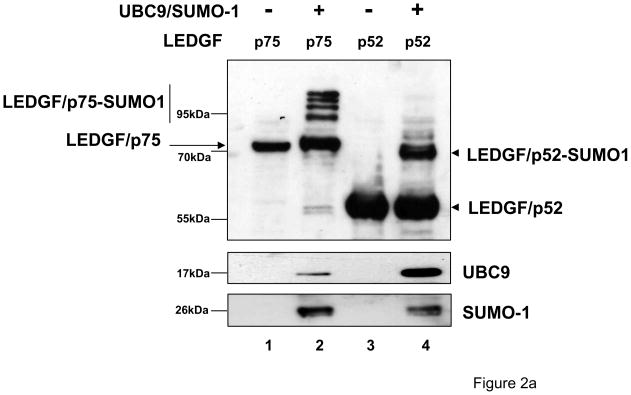

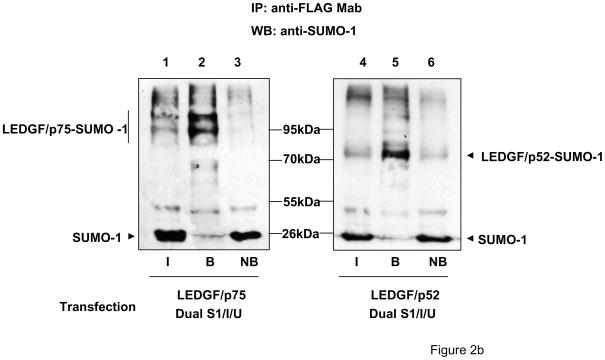

To further evaluate whether LEDGF/52 is also SUMOylated in vivo, LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T (si1340/1428) cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing either FLAG-tagged LEDGF/p75 or p52, and a plasmid expressing both SUMO-1 and the SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 (hereafter referred to as Dual S1/I/U). At 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer and the LEDGF proteins were detected by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody Mab (Fig. 2a). A single form of LEDGF proteins migrating at the expected relative molecular weight was observed in cells transfected with LEDGF/p75 or LEDGF/p52 expression plasmids alone (Fig. 2a, lanes 1 and 3). However, when Dual S1/I/U was co-transfected with LEDGF expression plasmids, additional high molecular weight forms of LEDGF proteins were detected. A single high molecular weight form was detected for LEDGF/p52 while four bands were detected for LEDGF/p75 suggesting that SUMOylation occurred at multiple sites in LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 2a, lanes 2 and 4). The difference in the molecular weight of the non-modified and modified LEDGF proteins was approximately 23kDa, consistent with the molecular weight of the tagged SUMO-1 used in our experiments, strongly suggesting that the slower-migrating forms observed corresponded to SUMOylated LEDGF proteins. In support of this interpretation, the high molecular weight forms of LEDGF proteins were also detected with an anti-SUMO-1 antibody, and this antibody failed to recognize the non-modified LEDGF proteins, as expected (Data not shown).

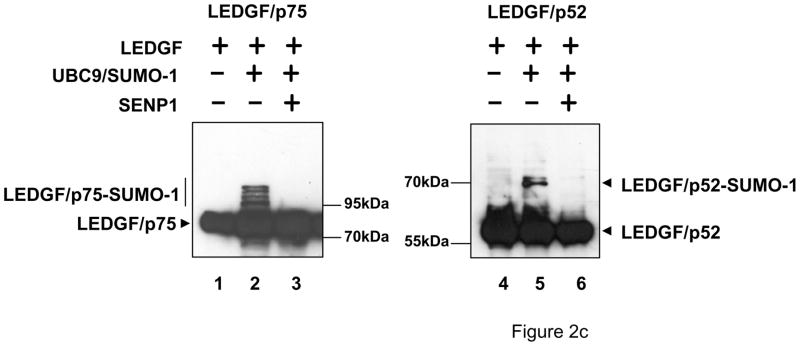

Figure 2.

LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75 are SUMO-1 targets. (a) LEDGF/p75-deficient cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged LEDGF expression plasmids alone or together with the Dual S1/I/U plasmid encoding UBC9 and SUMO-1. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for LEDGF proteins using an anti-FLAG Mab, and for UBC9 and SUMO-1 with specific antibodies. (b) Cells transfected as described in (a), were subjected to immunoprecipitation with magnetic beads loaded with an anti-FLAG Mab and subsequently immunoblotted with anti-SUMO-1 antibody. I: Input; B: anti-FLAG bound; NB: anti-FLAG non-bound proteins. (c) LEDGF/p75-deficient cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged LEDGF expression plasmids alone or together with the Dual S1/I/U plasmid encoding UBC9 and SUMO-1 and a SENP1 expression plasmid. Cellular lysates were immunoblotted for LEDGF proteins using an anti-FLAG Mab.

To provide definitive evidence that the high molecular weight LEDGF species corresponded to SUMOylated forms, si1340/1428 cells co-transfected with LEDGF expression plasmids and the Dual S1/I/U were lysed in CSKI buffer supplemented with 300 mM NaCl and the extracted proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG Mab bound to magnetic beads. The presence of SUMOylated proteins was then evaluated in the immunoprecipitated fraction with an anti-SUMO-1 antibody (Fig. 2b). Immunoprecipitation with the anti-FLAG Mab enriched the SUMO-reactive high molecular weight species, but did not enrich the non-conjugated SUMO-1 present in the cell extract (Fig. 2b, compare lane 1 with 2 and lane 4 with 5). Notice that the transfected SUMO-1 was not preferentially bound to the anti-FLAG Mab (Fig. 2b, lanes 2 and 5).

The identity of the high molecular weight forms of LEDGF proteins was further demonstrated in co-transfection experiments similar to those described in figure 2a, but performed with the addition of an expression plasmid for the de-SUMOylation enzyme SENP1. As expected, the high molecular weight forms of LEDGF proteins observed in cells co-transfected with LEDGF expression plasmids and Dual S1/I/U (Fig. 2c, lanes 2 and 5) were not observed when SENP1 was also co-transfected (Fig. 2c, lanes 3 and 6).

Collectively, the results presented in figure 2 demonstrated that LEDGF proteins are SUMO targets in vivo.

Analysis of LEDGF protein regions involved in SUMOylation

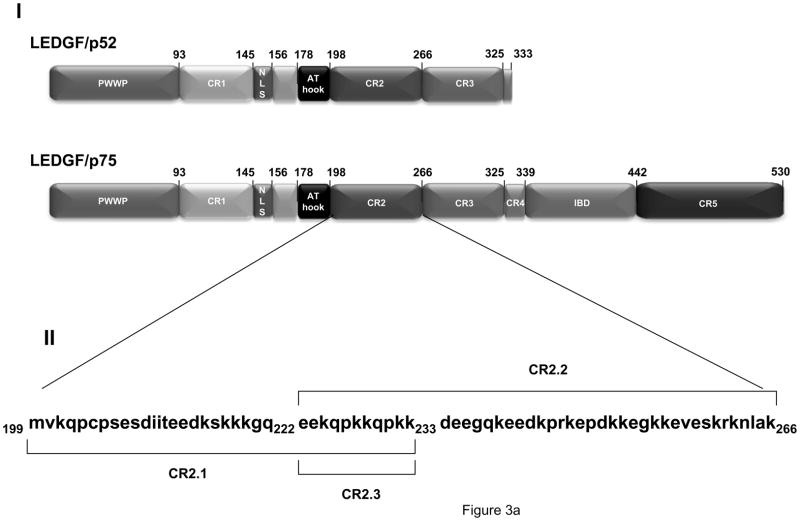

In order to map the SUMOylation target sites in LEDGF proteins, we evaluated the impact of deleting distinct regions within LEDGF on its ability to be SUMOylated. These LEDGF deletion mutants were C-terminally FLAG-tagged to facilitate their detection by immunoblotting. Deletion mutants have been successfully used to map different functional domains in LEDGF/p75 6; 18. Regions considered important for SUMOylation by this approach were characterized further by introducing single lysine to arginine substitutions of lysine residues contained within the selected regions. This substitution ablates SUMOylation and is predicted to perturb minimally the folding of the protein. The selection of the lysine residues to be mutated was aided by multiple SUMOylation prediction programs.

The LEDGF regions to be deleted were selected based on their evolutionary conservation from bony fish to humans, the presence of predicted SUMOylation target sites, and predicted solvent exposure. Five different regions were deleted in the shared N-terminal LEDGF: PWWP domain, charged region 1 (CR1), AT hook, CR2 and CR3; while three other regions, CR4, IBD and CR5 were deleted in the C-terminal part of LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 3a-I). The PWWP domain and the AT hook region form a functional chromatin binding domain whereas the CR1, CR2 and CR3 regions influence binding only slightly 4; 6. No functional role has been described for CR4 and CR5 regions, while IBD is central for the interaction of LEDGF/p75 with different cellular and viral proteins 8; 12; 39; 41; 42; 43. Importantly, two of the deleted regions, CR2 and CR4, are rich in lysine residues. About one-third of the amino acids in the CR2 region (amino acids 199-266) and 35.7% in CR4 (amino acids 326-339) correspond to lysines. Of note, the CR2 region contains 23.8% of all LEDGF/p75 lysine residues, despite the fact that it represents only 12.8% of the protein length. Therefore, to facilitate the analysis, this region was sub-divided in three different segments (Fig. 3a-II).

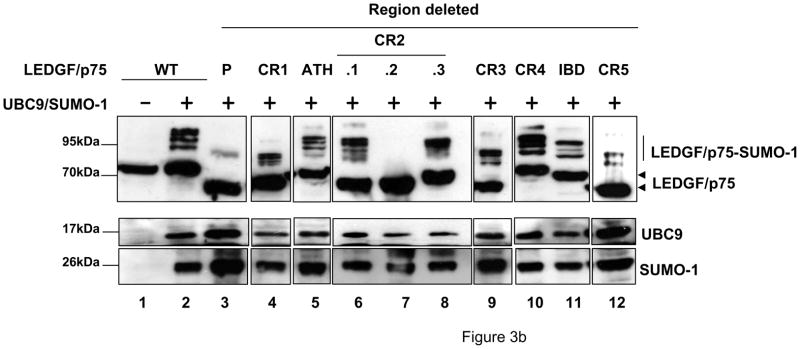

Figure 3.

Involvement of PWWP and CR2.2 in LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation. (a) Schematic representation of LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 protein regions. The numbers indicate the amino acid residue in LEDGF (b) LEDGF/p75-deficient cells were transfected with plasmids expressing LEDGF/p75 WT or deletion mutants alone or with the Dual S1/I/U plasmid. Cellular lysates were immunoblotted for LEDGF proteins using an anti-FLAG Mab and for UBC9 and SUMO-1 using specific antibodies. P: PWWP; ATH: AT hook motif.

In order to analyze the implication of these protein regions in LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation, plasmids expressing these deletion mutants were co-transfected into si1340/1428 cells alone or in combination with the Dual S1/I/U construct. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting as described above. SUMOylated forms of LEDGF/p75 were readily detected in the wild type (WT) protein as well as in the CR1, ATH, CR2.1, CR2.3, CR3, CR4, IBD and CR5 deletion mutants (Fig. 3b, lanes 2, 4–6, and 8–12). However, modification of LEDGF/p75 was severely impaired when the PWWP domain (residues 1-93) or the CR2.2 region (residues 223-266, fig. 3a-II) were deleted (Fig. 3b, lanes 3 and 7). The impairment in the SUMOylation of ΔPWWP and ΔCR2.2 mutants was not due to inefficient LEDGF/p75 or SUMO-1 or UBC9 protein expression since similar levels of these proteins were detected across all the samples (Fig. 3b). Therefore, these data indicated that the PWWP and CR2.2 regions are necessary for LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation.

Mapping the SUMOylation sites of LEDGF/p52

To identify the specific lysine residues modified by SUMOylation in the regions identified above, we conducted further mapping on LEDGF/p52 (Fig. 3a-I). This splicing variant is smaller than LEDGF/p75, contains both the PWWP domain and the CR2.2 region and its SUMOylation seems to be less complex than LEDGF/p75 as it produces only one predominantly modified form (Fig. 2a).

Out of the thirteen lysine residues in PWWP, only K6 and K34 were predicted to be SUMOylated (Table 1). However, during the execution of this study, it was reported that the hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF), a LEDGF-related protein, is SUMOylated at residue K80 in the PWWP domain 44. Residue K80 in HDGF is structurally equivalent to residue K75 in LEDGF which is located in a solvent-exposed cluster with four other lysine residues 45. Surprisingly, none of the prediction programs indicated this residue as an important target for SUMOylation.

Table 1.

SUMO-acceptor sites in LEDGF/p75 predicted with high probability.

Cut-off values used were SUMOplot score ≥ 0.67, SUMOpre score ≥ 0.2 and SUMOsp score ≥ 2.7

| Region | Residue | Prediction program |

|---|---|---|

| PWWP | K6 | SUMOplot |

| K34 | SUMOplot | |

| CR1 | None | None |

| NLS | K152 | SUMOsp, SUMOpre |

| ATH | K189 | SUMOplot |

| CR2 | K201 | SUMOplot |

| K219 | SUMOsp | |

| K225 | SUMOsp | |

| K229 | SUMOsp | |

| K233 | SUMOsp | |

| K239 | SUMOpre | |

| K250 | SUMOpre | |

| K254 | SUMOpre, SUMOsp, SUMOplot | |

| CR3 | K317 | SUMOpre, SUMOsp |

| CR4 | K329 | SUMOpre |

| K334 | SUMOpre | |

| K338 | SUMOsp | |

| K339 | SUMOpre | |

| IBD | K343 | SUMOpre, SUMOsp |

| K364 | SUMOplot | |

| CR5 | K467 | SUMOpre, SUMOsp |

| K470 | SUMOsp |

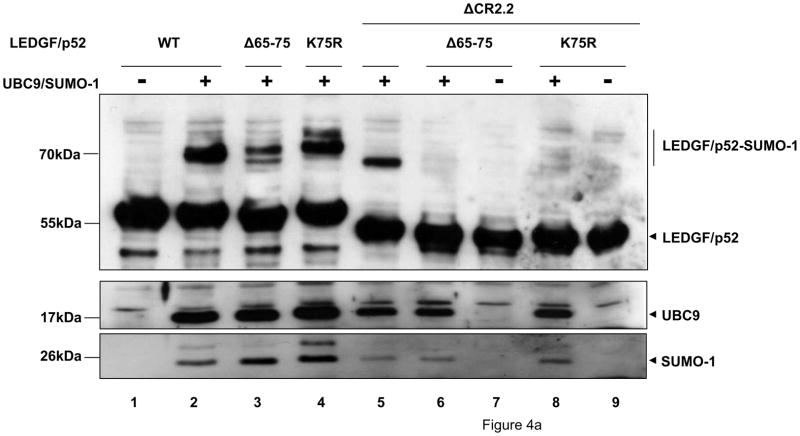

To evaluate the role of PWWP residues 65-75 and CR2.2 (residues 223-266) in LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation, si1340/1428 cells co-transfected with expression plasmids encoding these deletion mutants and the Dual S1/I/U construct. SUMOylation of these mutants was only slightly reduced (Fig. 4a, compare lanes 3 and 5 to lane 2), and similar results were also obtained with the point mutant LEDGF/p52 K75R (Fig. 4a. compare lanes 4 to lane 2), or with a mutant where all the lysine residues in the region 65-75 were mutated to arginine (data not shown). These data demonstrated that independent deletion of residues 65-75 or CR2.2 was not sufficient to impair the overall SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52.

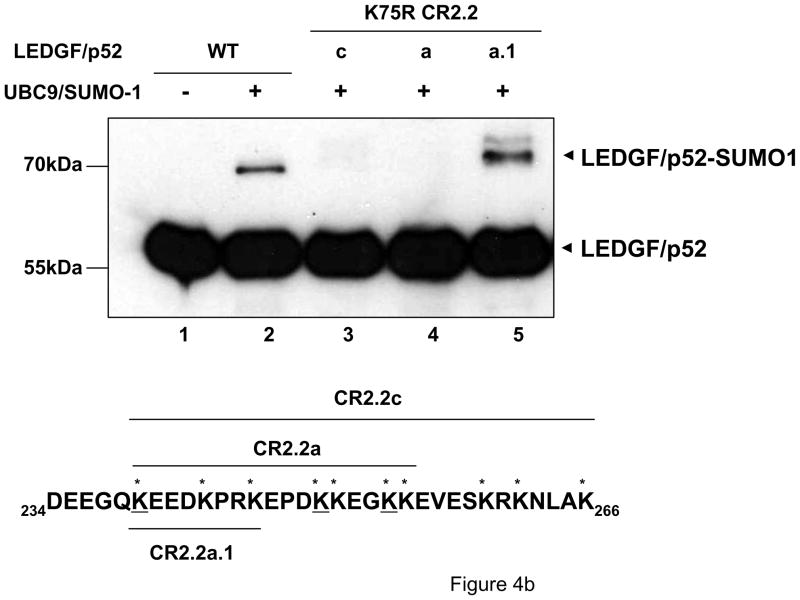

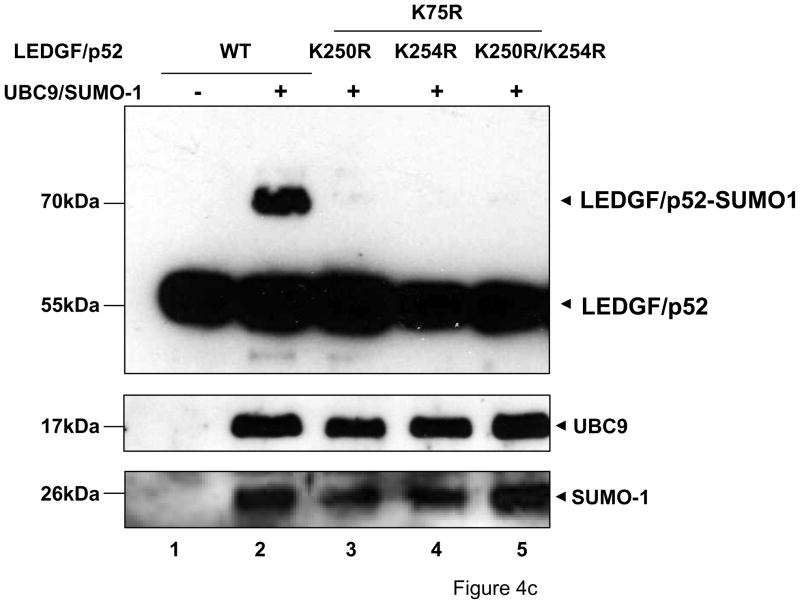

Figure 4.

LEDGF/p52 is SUMOylated in residues K75 and K250/K254. LEDGF/p75-deficient cells were transfected with plasmids expressing LEDGF/p52 WT or deletion mutants alone or with the Dual S1/I/U plasmid. Cellular lysates were immunoblotted as described in Fig. 3b. (a) Broad mapping of SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p52. (b) Effect of K to R simultaneous substitutions on LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation. (c) Fine mapping of SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p52.

To determine whether the simultaneous deletion of residues 65-75 and CR2.2 was required to prevent LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation, mutants lacking these two regions or containing a K75R substitution and a deletion of the CR2.2 region were evaluated for SUMOylation. These mutants were fully defective for SUMOylation (Fig. 4a, lanes 6–9), although similar levels of the unmodified LEDGF/p52, SUMO-1, and UBC9 were detected in these samples. These findings clearly demonstrated that K75 and residues within the CR2.2 region are the only targets for SUMO-1 modification in LEDGF/p52.

Evaluating the role of lysine residues within the CR2.2 region in LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation

In support of the data shown in Fig. 4a, SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 K75R CR2.2c was completely abrogated (Fig. 4b, lane 3). In this mutant, residue K75 and all the ten lysines found within the CR2.2 region not shared with CR2.3 (i.e., residues 234-266) were converted to arginine. Lysines situated within residues 223-233 were not mutated since we have previously observed that deletion of these residues (ΔCR2.3) did not affect LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation (Fig. 3b, lane 8). Moreover, the simultaneous K to R substitution of residues 239, 243, 246, 250, 251, 254 and 255 (LEDGF/p52 K75R/CR2.2a) also inhibited SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 K75R (Fig. 4b, lane 4). However, the simultaneous K to R substitution of residues 239, 243, and 246 (LEDGF/p52 K75R/CR2.2a.1) did not affect SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 K75R (Fig. 4b, lane 5), suggesting a role in LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation for lysine residues at positions 250, 251, 254 and 255.

Out of the four lysine residues in the 234-266 region of CR2.2, only K250 and K254 were predicted to be SUMOylated (Table 1). Therefore K to R mutations were introduced at these amino acid positions and their effect on LEDGF/p52 K75R SUMOylation evaluated. Interestingly, single substitutions at positions 250 and 254 were both able to individually abolish the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 K75R (Fig. 4c). These results clearly indicated that K75, K250 and K254 are the SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p52.

These results also suggested that SUMOylation of K250 and K254 are interdependent events, i.e. mutation of any of these residues is sufficient to prevent the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 K75R, while the SUMOylation of K75 and K250/254 seemed to be independent events. The fact that SUMOylated LEDGF/p52 was detected in immunoblots mainly as a single form (~75kDa) suggested that SUMOylation of K75 and K250/254 occurred with similar hierarchy and that simultaneous modification of both targets is not a common event.

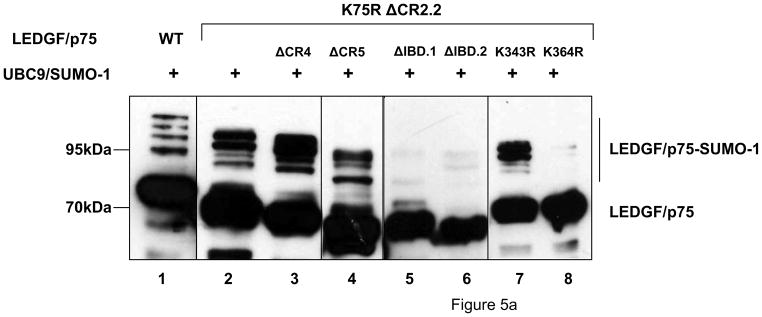

Mapping of the SUMOylation sites of LEDGF/p75

To evaluate the role of residues K75, K250 and K254 on LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation, a K75R/ΔCR2.2 LEDGF/p75 mutant was tested. In contrast with our LEDGF/p52 data, mutation of these N-terminal lysine residues changed the SUMOylation pattern of LEDGF/p75, but did not decrease it (Fig. 5a, lane 2). This result indicated that other SUMOylation acceptor sites were present in the C-terminal region of LEDGF/p75.

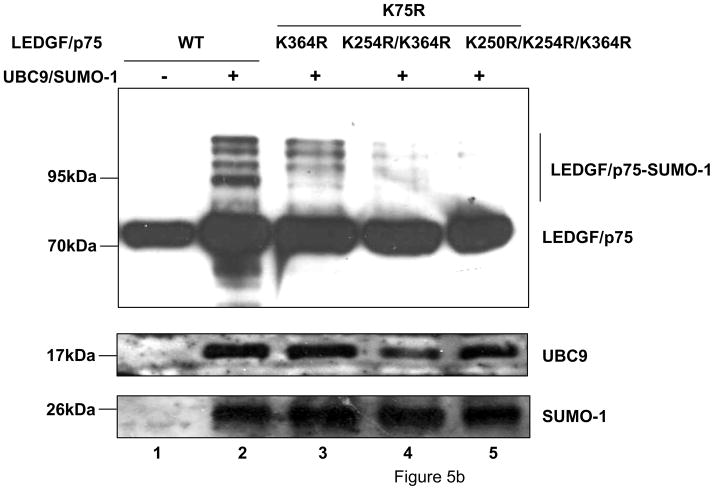

Figure 5.

LEDGF/p75 is SUMOylated at residues K75, K250/K254 and K364. Cells were transfected and analyzed as described in Fig. 3b. (a) Broad mapping of SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p75. (b) Fine mapping of SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p75.

To map potential C-terminal SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p75, we evaluated the impact of deleting CR4 or CR5 on LEDGF/p75 K75R ΔCR2.2 SUMOylation. Co-transfection of these mutants with the Dual S1/I/U construct revealed that they were modified as efficiently as LEDGF/p75 K75R ΔCR2.2 (Fig. 5a, lane 3 and 4). These results suggested that none of these C-terminal regions were implicated in the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75. On the contrary, deletion of the entire IBD (Data not shown) or deletion of residues 340-364 (IBD.1) or 374-442 (IBD.2) (Fig. 5a, lanes 5 and 6), predicted to destroy the folding of this domain 27; 28; 46; 47, severely impaired SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 K75R ΔCR2.2. These results indicated the involvement of the IBD in the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75.

The IBD contains twelve lysine residues but only K343 and K364 were predicted to be SUMOylated (Table 1). Therefore, the effect of K343R and K364R mutations on LEDGF/p75 K75R ΔCR2.2 SUMOylation was evaluated. The K343R substitution did not affect the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 K75R ΔCR2.2, while the K364R mutation severely reduced the SUMOylation of this mutant (Fig. 5a, lanes 7 and 8), indicating that this lysine is the major SUMOylation site in the C-terminal region of LEDGF/p75.

Next, we evaluated the individual contribution toward the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 of each of the lysine residues identified as relevant for LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation. Mutation of residues K75 and K364 reduced the abundance of the smaller SUMOylated forms (~ 95 kDa) of LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 5b, lane 3), while additional K to R substitutions at positions 254 or both 250 and 254 drastically reduced SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 5b, lanes 4 and 5). These data indicated that, as for LEDGF/p52, SUMOylation of residues K250 and K254 are interdependent and that residues K75, K250, K254 and K364 are the SUMOylation sites in LEDGF/p75.

LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 are SUMO-3 targets

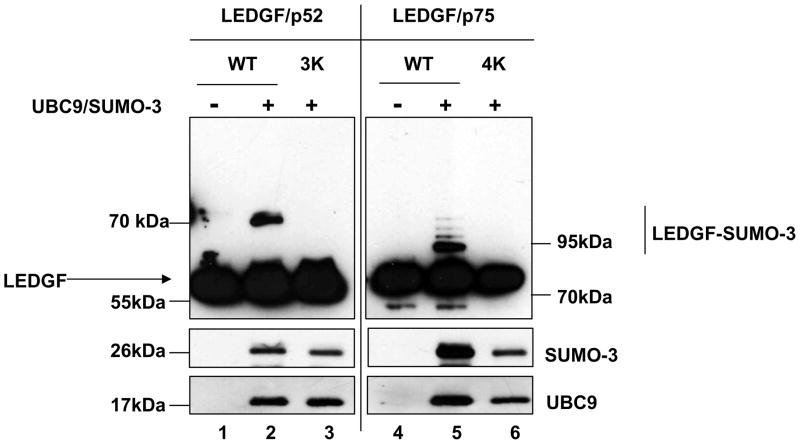

Several SUMO targets have been reported to be equally SUMOylated by SUMO-1 and SUMO2/3, while others show marked specificity for some of the isoforms28. In order to evaluate if SUMO-3 could modify LEDGF proteins, LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 wild type and SUMOylation deficient mutants were coexpressed with SUMO-3 and UBC9 in si1340/1428 cells (Fig. 6). LEDGF SUMOylation with SUMO-3 produced a strikingly similar SUMOylation pattern to the observed with SUMO-1 in both LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75, suggesting that the same SUMO acceptor sites are implicated (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 5). In support of this interpretation, K to R mutations of the identified SUMO-1 target sites completely abolished SUMO-3 modification of LEDGF proteins (Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 6).

Figure 6.

LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 are also SUMOylated with SUMO-3. LEDGF/p75-deficient cells were transfected with plasmids expressing LEDGF/p75 WT or deletion mutants alone or with the Dual S3/I/U plasmid. Cellular lysates were immunoblotted as described in Fig. 3b. LEDGF/p52 3K and LEDGF/p75 4K harbor the K75R/K250R/K254R and K75R/K250R/K254R/K364R mutations, respectively.

Effect of SUMOylation on the half-life of LEDGF/p75

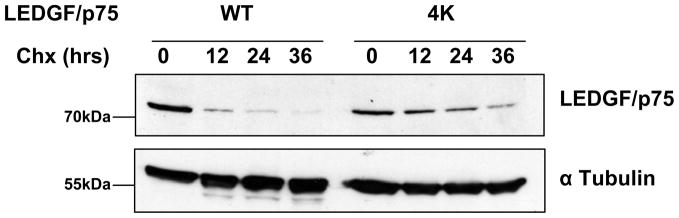

SUMOylation has been reported to modulate protein half-life (Reviewed in 26; 27; 28). Therefore, we investigated whether the SUMOylation-deficient form of LEDGF/p75 and the WT have similar half-lives. LEDGF/p75-deficient CD4+ T cells (TL3 cells) were engineered to stably express FLAG-tagged LEDGF/p75 WT or a LEDGF/p75 mutant harboring four point mutations K75R/K250R/K254R/K364R (4K). These cells were harvested at different time points following cycloheximide treatment and the protein levels of LEDGF/p75 WT or 4K were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG Mab. Data in figure 7 clearly indicate that the half-life of LEDGF/p75 is significantly extended when its SUMOylation is impaired. SUMOylation-deficient LEDGF/p75 (4K) exhibited a half-life approximately three times longer than LEDGF/p75 WT.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation increases its half-life. TL3 cells stably expressing LEDGF/p75 WT or SUMOylation-deficient LEDGF/p75 (4K) were treated with cycloheximide (chx) and harvested at different time points. The levels of LEDGF/p75 proteins were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG Mab. Detection of α tubulin was used as a loading control.

Effect of SUMOylation on the transcriptional regulatory activity of LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75

SUMOylation has been implicated in the regulation of the activity of different transcription factors affecting the activity of the Hsp27 promoter. Therefore, we investigated whether the impairment of LEDGF proteins SUMOylation influences their transcriptional activity on this promoter. A plasmid containing the Hsp27 promoter driving the expression of the firefly luciferase open reading frame (pGL3Hsp27luc) was used as reporter 16. LEDGF/p75-deficient si1340/1428 cells were transfected with pGL3Hsp27luc and a β-galactosidase expression plasmid (pCMV-β-gal) alone or in combination with plasmids expressing LEDGF/p75 or LEDGF/p52 proteins. The transfected cells were lysed 48 h later and both luciferase and β-galactosidase activity determined. To eliminate variability associated to differential transfection efficiency, the luciferase levels in the transfected cells were normalized to those of β-galactosidase.

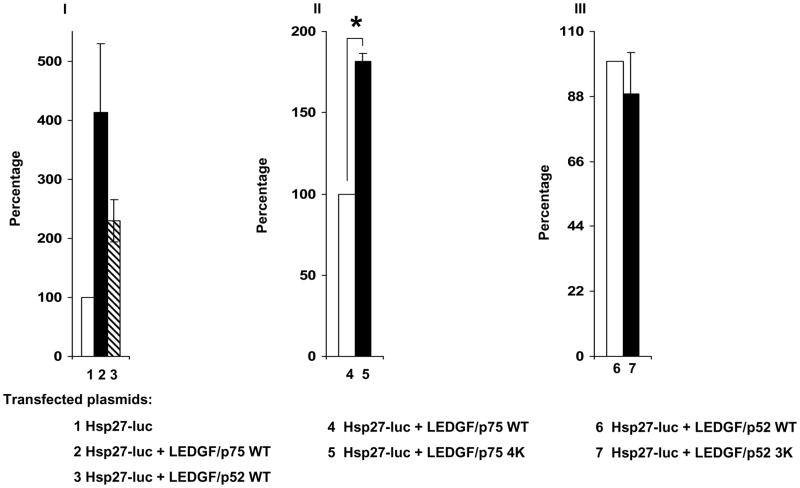

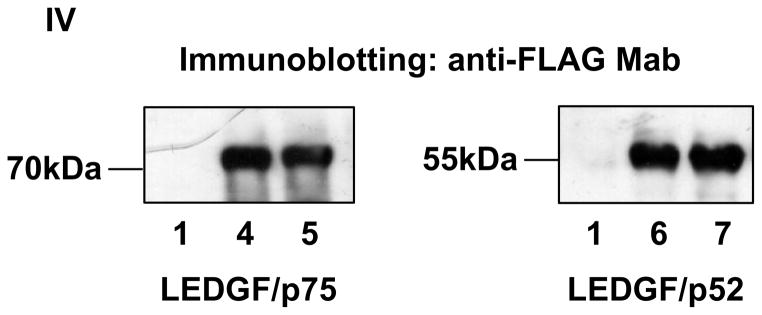

In support of previously reported data 16, LEDGF/p75 expression increased four fold the activity of the Hsp27 promoter whereas LEDGF/p52 produced a two fold increase (Fig. 8-I). Similar experiments performed with the non-SUMOylatable mutant forms of LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 revealed that mutations impairing LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation produced a statistically significant increase in its transcriptional activity (Fig. 8-II). However, mutations inhibiting LEDGF/p52 SUMOylation did not affect its transcriptional activity (Fig. 8-III). The differential transcriptional activity of these LEDGF proteins was not due to different levels of protein expression as indicated in figure 8-IV. These results suggested that LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75 activate the Hsp27 promoter by different molecular mechanisms and that SUMOylation attenuates the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75.

Figure 8.

SUMOylation negatively regulates LEDGF/p75 transcriptional activity. LEDGF/p75-deficient cells were co-transfected with reporter plasmids and expression plasmids carrying either no insert, LEDGF/p75, or LEDGF/p52. Two reporter plasmids expressing firefly luciferase under the Hsp27 promoter and β-galactosidase under the CMV promoter were used simultaneously. Detected luciferase values were normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Normalized luciferase levels in cells co-transfected with the empty expression plasmid were considered 100% to calculate the data included in panel I. Similarly, normalized luciferase values measured in cells expressing LEDGF WT proteins were considered as 100% to calculate the data included in panels II and III. Standard deviations correspond to two (panel I and II) or four (panel III) completely independent experiments performed on different days. Transfected plasmids are indicated by numbers below the corresponding bars. (*) Indicates significant statistical difference (p ≤ 0.05) using the two-tailed T-test. LEDGF/p52 3K and LEDGF/p75 4K harbor the K75R/K250R/K254R and K75R/K250R/K254R/K364R mutations, respectively. LEDGF protein expression in samples included in panel I-III was evaluated by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG Mab (panel IV), the sample number in panel IV corresponds to samples in panels I-III.

Effect of SUMOylation on the chromatin binding activity of LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75

HDGF SUMOylation, which occurs in residue K80 located in the PWWP domain, was reported to affect its chromatin binding activity 44. The PWWP domain also mediates chromatin binding in LEDGF proteins 4; 6; 7 and we have demonstrated here that K75, which is structurally equivalent to K80 in the HDGF, is also a SUMO target. Therefore, we investigated whether LEDGF SUMOylation affects its binding to chromatin.

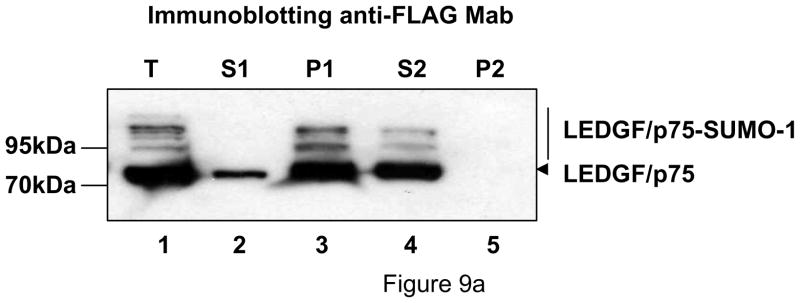

Chromatin binding of SUMOylated LEDGF/p75 was investigated using an assay based on the property of chromatin-bound proteins to resist extraction with isotonic buffers containing 1% Triton X-100 (chromatin binding assay) 6. Briefly, LEDGF/p75-deficient si1340/1428 cells co-transfected with a LEDGF/p75 and the Dual S1/I/U expression plasmids were lysed in an isotonic buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and fractionated by centrifugation into a soluble fraction containing chromatin non-bound proteins (S1) and an insoluble fraction (P1) enriched in chromatin-bound proteins. The P1 fraction was treated with DNase I and salts, and fractionated by centrifugation into soluble fraction (S2), containing chromatin bound protein, and insoluble (P2) fraction representative of insoluble chromatin non-bound proteins. Unfractionated cells were also lysed in Laemmli buffer (T). As expected for chromatin bound proteins, LEDGF/p75 was predominantly distributed in the P1 and S2 fractions (Fig. 9a, lanes 3 and 4). Trace amounts of LEDGF/p75 were observed in S1 probably as a consequence of saturation of its NLS-mediated nuclear import following protein overexpression (Fig. 9a, lane 2). Importantly, SUMOylated LEDGF/p75 was exclusively found in the chromatin-bound fractions (P1 and S2), indicating that this modification does not affect chromatin binding.

Figure 9.

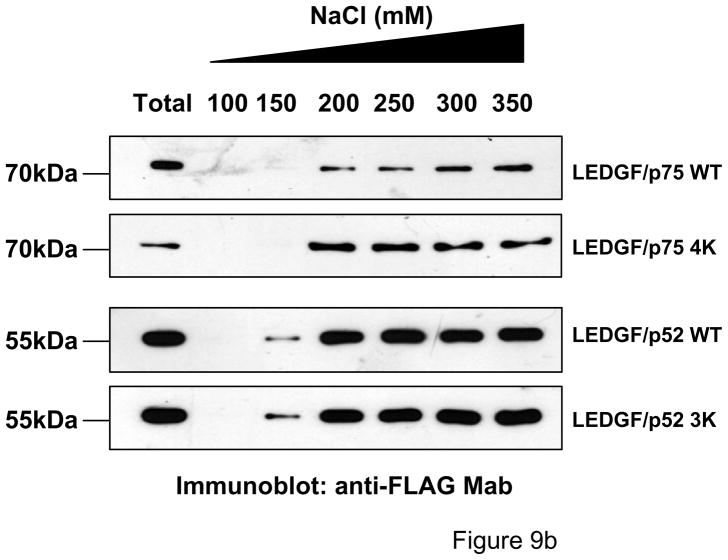

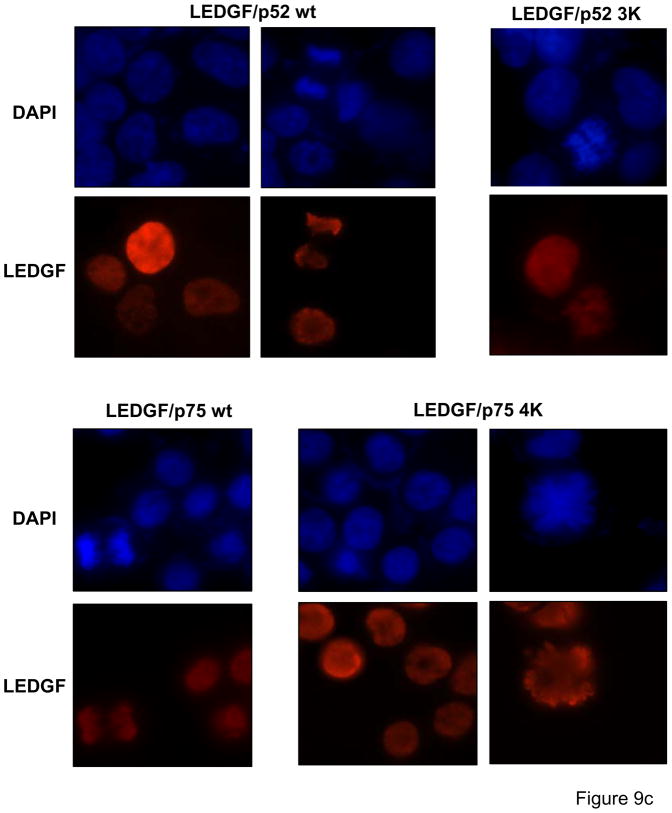

SUMOylation does not affect the chromatin binding properties of LEDGF. Chromatin-binding properties of LEDGF WT and SUMOylation-deficient mutants. (a) Chromatin-binding assay. LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T cells co-expressing FLAG-tagged LEDGF/p75 WT and UBC9/SUMO-1 were fractionated into non-chromatin-bound fractions (S1 and P2) and chromatin-bound fractions (P1 and S2) and the presence of LEDGF/p75 in these fractions was evaluated by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG Mab. An unfractionated total cellular lysate (T) was included as control. (b) Salt extraction analysis of WT and SUMOylation-deficient mutants of LEDGF. TL3 cells stably expressing different LEDGF proteins were lysed in a buffer containing increasing salt concentrations. Then, the presence of LEDGF proteins in a soluble, salt-extracted, fraction was evaluated by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG Mab. LEDGF/p52 3K and LEDGF/p75 4K carry the amino acid substitutions K75R/K250R/K254R and K75R/K250R/K254R/K364R, respectively. (c) Mutations impairing SUMOylation do not alter the sub-cellular distribution of LEDGF proteins. LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T cells transiently transfected with plasmids expressing LEDGF WT or mutant proteins were immunostained with an anti-FLAG Mab and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Chromatin was stained with DAPI. Cells in interphase and mitosis are presented. LEDGF/p52 3K and LEDGF/p75 4K harbor the K75R/K250R/K254R and K75R/K250R/K254R/K364R mutations, respectively.

Using the chromatin salt extraction assay, we next evaluated whether LEDGF SUMOylation is required for chromatin binding. This assay is based on the effect of salts on the binding of proteins to chromatin as high salt concentrations can efficiently extract chromatin-bound proteins. The salt extraction assay was performed using the LEDGF/p75-deficient CD4+ T cell line, TL3, engineered to stably express LEDGF/p52 and p75 WT and SUMOylation- deficient proteins. These cells were lysed in buffers containing 1% Triton X-100 and increasing concentrations of NaCl (100, 150, 200, 350 and 500 mM). Cellular lysates were centrifuged and supernatants (salt-extracted fraction) were evaluated by immunoblotting for the presence of LEDGF proteins. Total LEDGF protein extraction was achieved by lysing unfractionated cells in Laemmli sample buffer. Using this method, we found that LEDGF/p75 WT persisted bound to chromatin (salt-resistant fraction) at 100 and 150 mM NaCl and was fully extracted above 200mM NaCl (Fig. 9b). Instead, the binding of LEDGF/p52 to chromatin was slightly weaker than LEDGF/p75, being partially extracted at 150 mM NaCl. Importantly, SUMOylation-deficient LEDGF proteins were bound to chromatin as strong as their wild type counterparts (Fig. 9b).

In summary these experiments indicated that SUMOylated LEDGF/p75 can bind to chromatin and that this modification is not a pre-requisite for the binding of LEDGF proteins to chromatin.

Effect of SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 and LEDGF/p75 on their subcellular distribution

SUMOylation can potentially regulate protein-protein interactions and alter the subcellular distribution of the SUMOylated protein 27; 28. Therefore, the subcellular distribution of LEDGF wild type and SUMOylation-deficient proteins was investigated. LEDGF proteins were transiently expressed in si1340/1428 cells and their localization evaluated 36 hrs post-transfection by immunostaining with an anti-FLAG Mab (Fig. 9c). Both, wild type and SUMOylation-deficient proteins, were strictly localized to the cellular nuclei and showed a similar distribution pattern. These proteins were also bound to mitotic chromosomes indicating that SUMOylation does not influence the subcellular distribution of LEDGF proteins

Discussion

LEDGF proteins are transcriptional regulators that affect the expression of a variety of cellular genes 2; 16; 17; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22; 23; 24. The molecular mechanism implicated in the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75 was recently identified for the regulation of the expression of HOX genes 8. It involves a chromatin tethering mechanism characterized by the recruitment of transcriptional regulators to the target transcription unit by chromatin-bound LEDGF/p75. Remarkably, this LEDGF/p75 chromatin tethering mechanism is also exploited by HIV-1 to mediate viral DNA integration 10; 11. Our data reveal new aspects of the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75. We have identified that LEDGF proteins are SUMOylated at lysines residues K75, K250, K254 and K364 and that this modification negatively influences the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75. Furthermore, modification of residue K364 suggests potential implications for SUMOylation on the HIV-1 co-factor activity of LEDGF/p75.

Cellular stresses that trigger the expression of heat shock proteins also augment global SUMOylation in cells 25. SUMOylation of several transcriptional regulators has been reported to increase their repressive activities 27; 28. Therefore, SUMOylation could act as a negative regulatory loop that downregulates the expression of heat shock proteins previously upregulated during stress down to their basal levels. A similar negative role has been proposed for SUMOylation during the Interferon response 29; 30; 31. In support of this mechanism, it has been previously reported that SUMOylation of the Hsp27 promoter transcription factors Hsf1, Sp1 and AP-2 affects their transcriptional activity 34; 35; 36; 37; 38. Our data add further support for a negative role of SUMOylation on the transcriptional regulation of Hsp27 by extending the effect of this modification to the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75. We have found that mutations that severely impair the SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 increase its transcriptional activity on the Hsp27 promoter. However, this effect was not observed with LEDGF/52, indicating that these two proteins act through different molecular mechanisms to activate the Hsp27 promoter. The existence of two independent mechanisms of activation is also suggested by the fact that in different cell types the stimulatory effect of LEDGF/p75 on the Hsp27 promoter is always stronger than LEDGF/p52 16. Because LEDGF/p75, LEDGF/p52, and Hsf-1 likely compete for binding to the single copy of the HSE on the Hsp27 promoter 33, the effect of SUMOylation on this promoter is expected to be largely dependent on the identity of the transcriptional regulatory factor bound to the HSE.

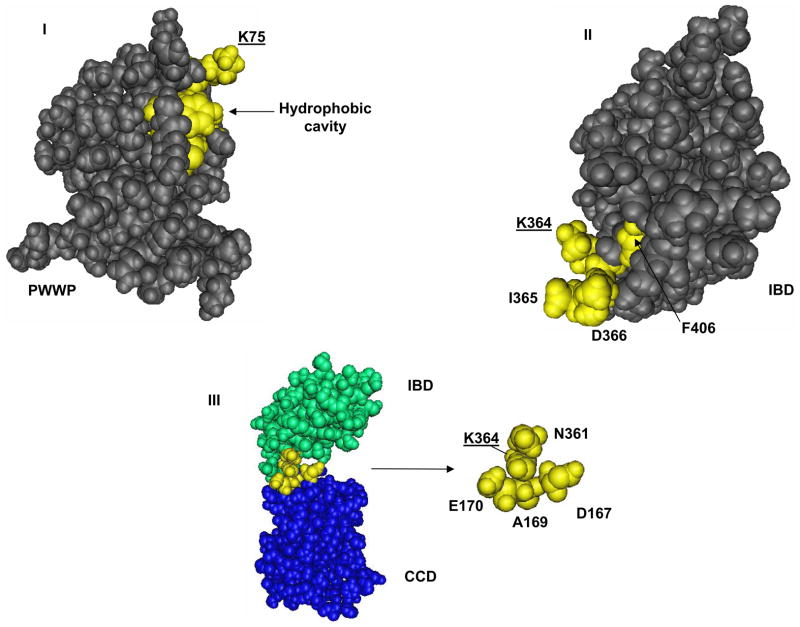

The mechanism by which SUMOylation negatively affects the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75 remains unknown. However, mutations inhibiting LEDGF/p75 SUMOylation also significantly increased the half-life of this protein. Since LEDGF/p75 is abundant in the cell, the impact of increasing its half-life on its transcriptional activity is difficult to assess. SUMOylation-deficient LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 did not show any apparent alteration in their subcellular distribution when compared to the wild type proteins. Therefore, it is unlikely that SUMOylation affects LEDGF/p75 transcriptional activity by altering its subcellular localization, as it has been reported for other transcription factors 27; 28. In addition, our data demonstrated that SUMOylation is not necessary for the chromatin-binding ability of LEDGF proteins nor does it affect this activity. This indicated that the negative regulatory effect of SUMOylation on LEDGF/p75 transcriptional activity on the Hsp27 promoter is likely to be independent of its chromatin binding capacity. This is still a surprising observation since the SUMO-acceptor site K75 is exposed to the solvent (Fig. 10-I) and positioned at the beginning of the PWWP α3 helix 45 which is located above a solvent-exposed hydrophobic cavity proposed to mediate the chromatin binding of LEDGF proteins 7; 48. Furthermore, SUMOylation of K80 in the PWWP domain of HDGF, which is structurally equivalent to residue K75 in LEDGF, prevented its binding to chromatin 44. These experimental evidences illustrate the complexity of the effect of SUMOylation on the interaction of PWWP domains with chromatin.

Figure 10.

The SUMO-acceptor lysine residues in PWWP and IBD are located in functional regions of these domains. Space-filling representations of the 3D structure of the (a) PWWP of mouse Hepatoma-Derived Growth Factor-Related Protein 3 (NCBI Molecular Modeling Database, MMDB, ID: 25592), (b) IBD of human LEDGF/p75 (MMDB ID: 33379) and (c) LEDGF/p75 IBD complexed with the HIV-1 integrase catalytic core domain, CCD (MMDB ID: 35690). SUMO-targeted lysine residues, K75 and K364 are underlined. The solvent-exposed hydrophobic cavity in PWWP (a) and the IBD residues I365, D366 and F406 essential for integrase binding (b) are also indicated. The HIV-1 integrase CCD residues E170, A169 and D167 that are in close proximity to the SUMO-targeted K364 in IBD are shown.

The cellular and virological roles of LEDGF/p75 depend on its chromatin tethering activity 49. Since SUMOylation did not alter LEDGF/p75 chromatin binding, it is plausible that SUMOylation of residue K364 in the IBD affects the transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75 by influencing its interaction with other cellular factors. This molecular mechanism would also explain why impairment of SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52, which lacks the IBD, did not modify its transcriptional activity. SUMOylation of residue K364 in the IBD could either recruit transcriptional repressors or prevent the binding of transcriptional activators to LEDGF/p75. Residue K364 is solvent-exposed (Fig. 10-II) 13 and is located in a consensus SUMO-acceptor motif 363LKID366 that is evolutionarily conserved across different species in the two IBD-containing proteins, LEDGF/p75 and HDGF related protein-2, suggesting its functional relevance.

SUMOylation of residue K364, in addition to modifying the cellular role of LEDGF/p75, may also affect its HIV-1 co-factor activity. The SUMO-acceptor motif 363LKID366 is situated in the solvent-exposed loop that connects helices α1 andα2 in the IBD (Fig. 10-II) 13. Residues I365 and D366 in this motif, together with V408, are the main IBD residues implicated in the high affinity interaction of LEDGF/p75 with the catalytic core domain (CCD) of HIV-1 integrase 50 (Fig. 10-III). Alanine mutation of any of these three residues completely abolished the interaction of LEDGF/p75 with integrase and also its HIV-1 cofactor activity 11; however, K364A affected minimally this protein-protein interaction 12. According to the crystal structure of the IBD-CCD complex (Fig. 10-III) 50, K364 is in close proximity to residues forming the interaction surface in both IBD and the CCD (Fig. 10-II and III). Therefore, SUMOylation of LEGDF/p75 at K364, because of its bulky nature, is expected to affect the interaction of IBD with HIV-1 integrase and to impair its HIV-1 co-factor activity. Experiments to evaluate this hypothesis are currently in progress.

Whereas SUMOylation of LEDGF/p75 concurrently occurs at different lysine residues, SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 appears to take place preferentially at only one site in the protein although it contains three different SUMO-targeted lysines. These data suggest that differential SUMOylation of LEDGF/p52 at each one of the acceptor residues could modulate its function by modifying the pool of different forms of SUMOylated LEDGF/p52 in the cell.

Collectively, our data indicate that LEDGF proteins are SUMO targets in vivo and that this posttranslational modification exerts a negative influence on the half-life and transcriptional activity of LEDGF/p75, and potentially on its HIV-1 co-factor activity. These findings also support the paradigm establishing SUMOylation as a global neutralizer of cellular processes upregulated upon cellular stress.

Material and Methods

Plasmids

The expression plasmids pFLAG LEDGF/p75 and pFLAG LEDGF/p52 were used for transient expression experiments. These plasmids have the promoter of the human cytomegalovirus immediate early gene, CMV promoter, driving the transcription of the LEDGF cDNAs. The LEDGF/p75 cDNA contains seven synonymous mutations in the target site of the twenty-one shRNA 1340 (AAAGACAGCATGAGGAAGCGA) 15. This shRNA is constitutively expressed in all the LEDGF/p75-deficient cell lines used in the studies reported here 11; 15. The LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 open reading frames were PCR amplified and cloned BamHI/ApaI into the pCMV-FLAG expression plasmid. pCMV-FLAG was derived from pCMV-Myc 11 by substituting Myc with the FLAG tag epitope. Myc was removed by ApaI/BglII digestion and a DNA linker containing the FLAG sequence flanked by ApaI/BglII sticky ends was inserted.

Stable expression of LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 WT or mutants in TL3 cells was achieved by retroviral transduction. These proteins were expressed from the murine leukemia virus expression plasmid pJZ308 11. FLAG-tagged LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and cloned into BamHI/Sal I sites in pJZ308 to generate pJZ-LEDGF/p75-FLAG and pJZ-LEDGF/p52-FLAG, respectively.

LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 mutants were generated in the LEDGF expression plasmids described above by the Phusion™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Finnzymes, Inc). The sequences of the specific primers used are available upon request. All the constructs described in this study were verified by overlapping DNA sequencing of the complete LEDGF cDNA.

SUMO-1 or SUMO-3 and UBC9 were expressed from bicistronic plasmids (Dual S1/I/U and Dual S3/I/U) containing the CMV promoter driving the expression of SUMO-1 or SUMO-3 and the internal ribosomal entry site sequence from encephalomyocarditis virus linked to the UBC9 open reading frame. These constructs were derived from previously described parental plasmids carrying His- and S- tagged SUMO proteins 51.

The evaluation of the effect of LEDGF proteins on transcription was performed with the pGL3Hsp27luc plasmid 16, which contains the human Hsp27 promoter driving the expression of firefly luciferase. In these experiments β-galactosidase expression from the plasmid pCMV-β-gal was used to normalize for transfection efficiency. This plasmid expresses β-galactosidase from the CMV promoter.

Cell lines

LEDGF/p75-deficient cell lines

The LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T-derived cell line si1340/1428 15 was used for transient expression of LEDGF/p75 proteins. The LEDGF/p75-deficient human CD4+ T cell line, TL3 11, was used for stable expression of LEDGF/p75 and p52 WT and mutants. These cells were generated by transduction of SupT1 cells with an HIV-derived vector expressing a shRNA against LEDGF/p75 11. To generate TL3 cells expressing different LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 (WT or mutants), cells were transduced with Murine Leukemia Virus-derived vectors expressing the different LEDGF proteins C-terminally FLAG tagged and selected in G418 (600 μg/ml), as described previously 11. Robust polyclonal G418-resistant cell lines were obtained and characterized by immunoblotting with an anti-LEDGF (BD Transduction Laboratories, catalog number 611714) or anti-FLAG (Clone M2, Sigma) monoclonal antibodies (Mabs). The HEK 293T-derived packaging cell line, Phoenix A, was used for production of Murine Leukemia Virus-derived vectors.

TL3-derived cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 containing G418 (600 μg/ml), Phoenix A cells were grown in DMEM and si1340/1428 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with puromycin (3 μg/ml) and hygromycin (200 μg/ml). Both RPMI1640- and DMEM-based culture media were supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Generation of retroviral vectors

Previously described procedures 11 were followed for the production of the different retroviruses used in this study. Briefly, Phoenix A packaging cells were co-transfected by calcium-phosphate with 15 μg of the expression plasmid pJZ-LEDGF/p75-FLAG or pJZ-LEDGF/p52-FLAG (WT or mutants) and 5 μg of the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus glycoprotein G expression plasmid, pMD.G. At 48 h post-transfection, the viral supernatants were harvested and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 124,750 × g for 2 h on a 20% sucrose cushion. Viral aliquots were stored at −80°C until use.

Immunoblotting

Cellular lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred overnight to PVDF membranes at 100 mA at 4°C. Membranes were blocked in TBS containing 10% milk for one hour and then incubated with the corresponding primary antibody diluted in 1 × TBS, 5% milk, 0.05% Tween 20 (antibody dilution buffer). FLAG-tagged LEDGF proteins were detected with anti-FLAG Mab (1/1,000, M2, Sigma), or anti-LEDGF Mab (1/250). SUMO-1, SUMO-3 and UBC9 proteins were detected with previously described specific rabbit antisera (1/5,000) 51. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with previously described primary antibodies then washed in 1 × TBS, 0.1% Tween 20 and bound antibodies detected with goat anti-mouse Igs-HRP or anti-rabbit Igs-HRP (Sigma) diluted 1/2,000 or 1/5,000, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation

To evaluate whether LEDGF/p75 is conjugated to SUMO-1 under physiological conditions, we used a LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T-derived cell line stably expressing LEDGF/p75 WT. In this experiment, 5 × 106 cells were harvested and incubated at 43 °C (heat shock) or 37°C (non-heat shock) for 1 hr and then lysed in 100 μl of CSK I buffer supplemented with 300mM NaCl, protease inhibitors, 5μM MG132, 30mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 30mM iodoacetamide for 15 mins on ice. The cell lysate was diluted twice with CSK I, supplemented as above, but lacking NaCl (washing buffer) to reach a final concentration of 150mM NaCl. These samples were applied to protein A/G spin columns (Thermo Scientific NAb Protein A/G Spin kit, 89950) previously loaded with 25 μg of a rabbit anti-LEDGF/p75 antibody (Bethyl Laboratories’ A300-847A) or lacking antibody (negative control). The rabbit anti-LEDGF/p75 antibody was loaded into the column by incubation at room temperature for 10 mins followed by two washes with 5 times the column bed volume of washing buffer. Columns were incubated with cell lysates for 15 mins at room temperature and then washed three times with 5 times the column bed volume of washing buffer. The bound proteins were eluted from the columns using 75 μl of elution buffer (Thermo Scientific NAb Protein A/G Spin kit, 89950); the elution was repeated three times using the same eluate. Then, 10 μl of neutralization buffer and 6 μl of Laemmli buffer were added to the eluate and boiled for 10 mins. Eluted proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-SUMO-1 antibody (1/2000 Santa Cruz, sc-9060).

A different immunoprecipitation procedure was used to study SUMOylation of LEDGF when cells were cotransfected with the Dual S1/I/U plasmid and plasmids expressing LEDGF/p75 or LEDGF/p52. LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T-derived si1340/1428 cells were plated at 0.45 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate and co-transfected the next day by calcium-phosphate with 2 μg of pFLAG LEDGF/p75 or pFLAG LEDGF/p52 and the Dual S1/I/U plasmids. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed in 200 μl of CSK I buffer supplemented with 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM NEM and protease inhibitors. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 3 min and supernatant used for immunoprecipitation using goat anti-mouse Igs-coated magnetic beads (Pierce). Beads (200 μl) were previously incubated for 20 min on ice with 3 μg of anti-FLAG Mab diluted in CSK I buffer. Then, beads were separated from the unbound antibodies, mixed with the cell lysate and rotated for 1 hr at 4°C. After this incubation, beads were washed three times in CSK I buffer and bound proteins eluted by boiling in 30 μl of Laemmli sample buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted for the presence of SUMO-1 with a specific antibody.

SUMOylation analysis

si1340/1428 cells were plated at 0.45 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate and co-transfected the next day by calcium-phosphate with 2 μg of pFLAG LEDGF and 2μg of the Dual S1/I/U or Dual S3/I/U plasmid. Transfection medium was replaced after 18 h with fresh medium and cells were lysed for analysis 48 h later. Cells were lysed in 300 μl/well of boiling Laemmli buffer to inactivate all SUMO proteases. Only experiments with similar transfection efficiency were considered. Transfection efficiency was evaluated by immublotting detection of LEDGF proteins. Cell lysates were subjected to serial dilutions and 10 μl of each dilution analyzed. Different samples of the same dilution were resolved in the same gel and analyzed by immunoblotting on the same PVDF membranes to minimize variability.

Chromatin-Binding Assay

Previously described procedures 6 were followed with minor modifications. Briefly, si1340/1428 cells were plated at 0.45 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate and co-transfected the next day by calcium-phosphate with 2 μg of pFLAG LEDGF/p75 WT and 2 μg of the Dual S1/I/U plasmid. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested, washed in PBS and distributed into three identical aliquots. Two of the samples were lysed for 15 min on ice in 100 μl of CSK I buffer (10 mM Pipes pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 300 mM sucrose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitors (final concentration: leupeptine 2 μg/ml, aprotinin 5 μg/μl, PMSF 1 mM, pepstatin A 1 μg/ml). The third sample was lysed for 15 min on ice in 100 μl CSK I buffer supplemented with 350 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors, centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C and supernatant saved for further analysis (total fraction, T). Cells lysed in CSK I buffer were centrifuged at 1, 000 × g for 6 min at 4°C and the supernatant pooled (non-chromatin-bound fraction, S1). S1 supernatants were clarified further by centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 3 min while pellets were washed once in 200 ul of CSK I buffer. One of these pellets was resuspended in CSK I 350 mM NaCl buffer and incubated on ice for 15 min followed by centrifugation at 22,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for further analysis (chromatin-bound fraction, P1). The other pellet, obtained after cell lysis in CSK I, was resuspended in 100 μl of CSK II buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, 4 units of turbo DNase (Ambion) and 11 μl of 10 X turbo DNase reaction buffer. DNase treatment of this pellet was conducted at 37°C for 30 min and then followed by extraction with (NH4)2SO4 250 mM for 15 min at 37°C. The DNase/(NH4)2SO4 treated sample was centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 3 min and the supernatant saved for analysis (chromatin-bound fraction, S2). The resulting pellet was further extracted with CSK I 350 mM NaCl for 15 min on ice, centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 3 min and the supernatant obtained (non-chromatin-bound fraction, P2) collected for analysis. A volume of 15.7 μl of S1, P1, P2 and T and 20 μl of S2 (amounts equivalent to 0.9 × 106 cells) was evaluated by immunoblotting using an anti-FLAG Mab.

Salt extraction assay

36 × 106 TL3 cell lines expressing LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 WT and mutants were washed with PBS and distributed into six samples, each containing an equal amount of cells. One of the samples was resuspended in 100 μl of Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 9 min and centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 3 min and the resulting supernatant was further analyzed (total fraction, T). The other five cellular aliquots were lysed on ice for 15 min in 100 μl of CSK I containing protease inhibitors and supplemented with increasing concentrations of NaCl (final concentration: 100, 150, 200, 350 and 500 mM). Lysed cells were centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C and the supernatant (salt-extracted fraction) collected for analysis. The presence of LEDGF proteins in the different samples was analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG Mab using 20 μl of cell lysate, equivalent to approximately 6 × 104 cells.

Transcriptional activity

The effect of LEDGF proteins on transcription was evaluated using the LEDGF-responsive promoter of the heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27). LEDGF/p75-deficient si1340/1428 cells were plated at 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate and co-transfected the next day with 0.25 μg of pFLAG LEDGF expression plasmids, 0.3 μg of pGL3Hsp27luc and 20 ηg of pCMVGal using Fugene HD (Roche). Cells were lysed 48 h later in 1 × PBS, 1% Tween 20. Firefly luciferase and β-galactosidase enzymatic activities were measured using Bright-Glo and Beta-Glo (Promega), respectively. Luciferase levels were normalized by β-galactosidase activity values for each sample to control for transfection efficiency. Only samples differing in less than 10% of the β-galactosidase activity were considered for analysis. In addition, expression of LEDGF proteins was verified by immunoblotting.

Fluorescence microscopy

si1340/1428 cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/chamber in 2 mls of culture medium in LabTek II chambered coverglasses and transfected the next day by calcium-phosphate with 2 μg of pFLAG-LEDGF/p75 or pFLAG-LEDGF/p52 (WT or mutants). At 18 h post-transfection, fresh culture medium was added and 48 h later cells were washed three times in 1 × PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde-PBS for 10 min at 37°C. Then, cells were washed twice in 1 × PBS and incubated for 2 h at 37°C with anti-FLAG Mab diluted 1/1,000. Bound antibodies were detected by incubation with anti-mouse Ig coupled to Alexa Fluor 594 (10 μg/ml) for 45 min at 37°C. Finally, the slides were washed and stained with DAPI. The subcellular distribution of LEDGF proteins was then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

Quantitative co-localization assay

Co-localization was evaluated with a confocal microscope using the Zeiss Zen software. In order to set up this method we evaluated co-localization of LEDGF/p75 with HIV-1 integrase. These proteins interact during all the phases of the cell cycle 14; 15. As a negative control a LEDGF/p75 mutant lacking the integrase binding domain was used. For confocal microscopy analysis LEDGF/p75-deficient HEK 293T cells stably expressing eGFP-tagged HIV-1 integrase (2LKD-IN-eGFP cells 40) were plated at 2×105 cells in 2mls in a LabTek II chambered coverglasses and transfected the next day with 2ug of pFLAG-LEDGF/p75 WT or IBD deletion mutant. Eighteen hrs after transfection fresh culture medium was added and forty-eight hours later cells were immunostained as described above in the “Fluorescence microscopy” section. These cells were then used for confocal quantitative co-localization analysis. In order to measure co-localization of LEDGF/p75 and SUMO-1, HeLa cells were plated at 2×105 cells in 2mls in a LabTek II chambered coverglasses and the next day incubated or not for 1hr at 43°C in a 5% CO2 incubator (heat shock treatment). Then, treated and non-treated cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde-PBS and immunostained as described in the “Fluorescence microscopy” section. LEDGF/p75 was detected with an anti-LEDGF Mab diluted 1/100 (clone 26, BD Transduction Laboratories) using an anti-mouse Ig coupled to Alexa Fluor 594 (10 μg/ml). SUMO-1 was immunostained with an anti-SUMO-1 antibody diluted 1/100 (sc-9060, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using a goat anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1/100 (401315, Calbiochem). Finally, the slides were washed and stained with DAPI. Immunostained cells were then analyzed in the confocal microscope and the LEDGF/p75/SUMO-1 co-localization quantified using the Zeiss Zen software.

Quantification of LEDGF/p75 protein half-life

3×106 LEDGF/p75-deficient CD4+ human T cells engineered to stably express FLAG-tagged LEDGF/p75 WT or the K75R/K250R/K254R/K364R mutant (4K) were plated in 2 mls of culture medium in a 6-well plate and treated or not with cycloheximide (50μg/ml) for 12, 24 and 36 hrs. Cells were harvested, lysed in Laemmli buffer and analyzed for LEDGF/p75 levels by immunoblotting using an anti-FLAG Mab as described in the “Immunoblotting” section. As a loading control, α tubulin levels were determined by incubating the same immunoblot membranes with a specific Mab (1/4000, clone DM1A Sigma) for 2 hrs at room temperature.

In silico analysis

Mutations introduced in LEDGF/p75 and LEDGF/p52 were guided by a systematic bioinformatics analysis focused on evolutionary conservation across different species, the prediction of SUMO acceptor sites, and predicted solvent accessibility. Evolutionary conservation, as referred in this text, includes the presence of either identical or homologous residues in the protein sequences compared. LEDGF protein sequences were retrieved from the NCBI protein database and aligned using ClustalW2 52; sequence comparisons were performed with BLASTP 2.2.19+ 53. Prediction of relative solvent accessibility was performed with PaleAle 52. Three different SUMOylation site prediction softwares, SUMOsp 54, SUMOplot™ and SUMOpre 55 were used.

Space-filling representations of 3D structures were generated with the NCBI helper application Cn3D4.1. Structures of the PWWP domain of mouse Hepatoma- Derived Growth Factor-Related Protein 3 (ID: 25592), the human LEDGF/p75 IBD (ID: 33379), and the HIV-1 integrase catalytic core domain (CCD) complexed to IBD (ID: 35690) were downloaded from the NCBI Molecular Modeling Database.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 1SC2GM082301-01 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), (to ML); a University Research Institute grant from the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) (to ML); Grant 1SC2AI081377-01 from the Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the NIGMS, NIH (to GRA); grant 0765137Y from the American Heart Association (South-Central Filiate) (to GRA). J.A.G. was supported by a fellowship from the UTEP RISE program, NIH grant 2R25GM069621-05. J.R.K. was supported by HHMI grant 52005908. UTEP core facilities are funded by the BBRC grant 5G12RR008124. We thank: Eric Poeschla, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN for providing us with LEDGF/p75-deficient cell lines and LEDGF/p75 expression plasmids, Carlos Casiano, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda CA for the pGL3Hsp27luc reporter plasmid, Alma Navarro and Juan Rosas (UTEP) for technical support. We also thank Luciane Ganiko, Armando Varela and Igor Almeida (UTEP) for the assistance in using the fluorescence and confocal microscopes.

Abbreviations

- LEDGF

Lens epithelium-derived growth factor

- SUMO

Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier

- Hsp27

heat shock protein 27

- IBD

integrase binding domain

- HSE

heat shock elements

- Hsf-1

heat shock transcription factor 1

- Mab

monoclonal antibody

- WT

wild-type

- HDGF

hepatoma-derived growth factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Ge H, Si Y, Roeder RG. Isolation of cDNAs encoding novel transcription coactivators p52 and p75 reveals an alternate regulatory mechanism of transcriptional activation. Embo J. 1998;17:6723–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh DP, Ohguro N, Chylack LT, Jr, Shinohara T. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: increased resistance to thermal and oxidative stresses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1444–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh DP, Kimura A, Chylack LT, Jr, Shinohara T. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF/p75) and p52 are derived from a single gene by alternative splicing. Gene. 2000;242:265–73. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turlure F, Maertens G, Rahman S, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. A tripartite DNA-binding element, comprised of the nuclear localization signal and two AT-hook motifs, mediates the association of LEDGF/p75 with chromatin in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1653–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishizawa Y, Usukura J, Singh DP, Chylack LT, Jr, Shinohara T. Spatial and temporal dynamics of two alternatively spliced regulatory factors, lens epithelium-derived growth factor (ledgf/p75) and p52, in the nucleus. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;305:107–14. doi: 10.1007/s004410100398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llano M, Vanegas M, Hutchins N, Thompson D, Delgado S, Poeschla EM. Identification and characterization of the chromatin-binding domains of the HIV-1 integrase interactor LEDGF/p75. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:760–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shun MC, Botbol Y, Li X, Di Nunzio F, Daigle JE, Yan N, Lieberman J, Lavigne M, Engelman A. Identification and characterization of PWWP domain residues critical for LEDGF/p75 chromatin binding and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity. J Virol. 2008;82:11555–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01561-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoyama A, Cleary ML. Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge H, Si Y, Wolffe AP. A novel transcriptional coactivator, p52, functionally interacts with the essential splicing factor ASF/SF2. Mol Cell. 1998;2:751–9. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shun MC, Raghavendra NK, Vandegraaff N, Daigle JE, Hughes S, Kellam P, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. LEDGF/p75 functions downstream from preintegration complex formation to effect gene-specific HIV-1 integration. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1767–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.1565107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llano M, Saenz DT, Meehan A, Wongthida P, Peretz M, Walker WH, Teo W, Poeschla EM. An essential role for LEDGF/p75 in HIV integration. Science. 2006;314:461–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1132319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherepanov P, Devroe E, Silver PA, Engelman A. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved domain in human lens epithelium-derived growth factor/transcriptional co-activator p75 (LEDGF/p75) that binds HIV-1 integrase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48883–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherepanov P, Sun ZY, Rahman S, Maertens G, Wagner G, Engelman A. Solution structure of the HIV-1 integrase-binding domain in LEDGF/p75. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:526–32. doi: 10.1038/nsmb937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maertens G, Cherepanov P, Pluymers W, Busschots K, De Clercq E, Debyser Z, Engelborghs Y. LEDGF/p75 is essential for nuclear and chromosomal targeting of HIV-1 integrase in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33528–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llano M, Vanegas M, Fregoso O, Saenz D, Chung S, Peretz M, Poeschla EM. LEDGF/p75 determines cellular trafficking of diverse lentiviral but not murine oncoretroviral integrase proteins and is a component of functional lentiviral preintegration complexes. J Virol. 2004;78:9524–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9524-9537.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown-Bryan TA, Leoh LS, Ganapathy V, Pacheco FJ, Mediavilla-Varela M, Filippova M, Linkhart TA, Gijsbers R, Debyser Z, Casiano CA. Alternative splicing and caspase-mediated cleavage generate antagonistic variants of the stress oncoprotein LEDGF/p75. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1293–307. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machida S, Chaudhry P, Shinohara T, Singh DP, Reddy VN, Chylack LT, Jr, Sieving PA, Bush RA. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor promotes photoreceptor survival in light-damaged and RCS rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1087–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh DP, Kubo E, Takamura Y, Shinohara T, Kumar A, Chylack LT, Jr, Fatma N. DNA binding domains and nuclear localization signal of LEDGF: contribution of two helix-turn-helix (HTH)-like domains and a stretch of 58 amino acids of the N-terminal to the trans-activation potential of LEDGF. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:379–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh DP, Fatma N, Kimura A, Chylack LT, Jr, Shinohara T. LEDGF binds to heat shock and stress-related element to activate the expression of stress-related genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283:943–55. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatma N, Kubo E, Sharma P, Beier DR, Singh DP. Impaired homeostasis and phenotypic abnormalities in Prdx6−/−mice lens epithelial cells by reactive oxygen species: increased expression and activation of TGFbeta. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:734–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma P, Fatma N, Kubo E, Shinohara T, Chylack LT, Jr, Singh DP. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor relieves transforming growth factor-beta1-induced transcription repression of heat shock proteins in human lens epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20037–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsui H, Lin LR, Singh DP, Shinohara T, Reddy VN. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: increased survival and decreased DNA breakage of human RPE cells induced by oxidative stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2935–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin JH, Piao CS, Lim CM, Lee JK. LEDGF binding to stress response element increases alphaB-crystallin expression in astrocytes with oxidative stress. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubo E, Fatma N, Sharma P, Shinohara T, Chylack LT, Jr, Akagi Y, Singh DP. Transactivation of involucrin, a marker of differentiation in keratinocytes, by lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) J Mol Biol. 2002;320:1053–63. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tempe D, Piechaczyk M, Bossis G. SUMO under stress. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:874–8. doi: 10.1042/BST0360874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill G. Something about SUMO inhibits transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilgarth RS, Murphy LA, Skaggs HS, Wilkerson DC, Xing H, Sarge KD. Regulation and function of SUMO modification. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53899–902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Park SM, Kim OS, Lee CS, Woo JH, Park SJ, Joe EH, Jou I. Differential SUMOylation of LXRalpha and LXRbeta mediates transrepression of STAT1 inflammatory signaling in IFN-gamma-stimulated brain astrocytes. Mol Cell. 2009;35:806–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EJ, Park JS, Um SJ. Ubc9-mediated sumoylation leads to transcriptional repression of IRF-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:952–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubota T, Matsuoka M, Chang TH, Tailor P, Sasaki T, Tashiro M, Kato A, Ozato K. Virus infection triggers SUMOylation of IRF3 and IRF7, leading to the negative regulation of type I interferon gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25660–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804479200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi T, Sharma P, Athanasiou M, Kumar A, Yamada S, Kuehn MR. Mutation of SENP1/SuPr-2 reveals an essential role for desumoylation in mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5171–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5171-5182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oesterreich S, Hickey E, Weber LA, Fuqua SA. Basal regulatory promoter elements of the hsp27 gene in human breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:155–63. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong Y, Rogers R, Matunis MJ, Mayhew CN, Goodson ML, Park-Sarge OK, Sarge KD. Regulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 by stress-induced SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40263–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunet Simioni M, De Thonel A, Hammann A, Joly AL, Bossis G, Fourmaux E, Bouchot A, Landry J, Piechaczyk M, Garrido C. Heat shock protein 27 is involved in SUMO-2/3 modification of heat shock factor 1 and thereby modulates the transcription factor activity. Oncogene. 2009;28:3332–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spengler ML, Brattain MG. Sumoylation inhibits cleavage of Sp1 N-terminal negative regulatory domain and inhibits Sp1-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5567–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YT, Chuang JY, Shen MR, Yang WB, Chang WC, Hung JJ. Sumoylation of specificity protein 1 augments its degradation by changing the localization and increasing the specificity protein 1 proteolytic process. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:869–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eloranta JJ, Hurst HC. Transcription factor AP-2 interacts with the SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 and is sumolated in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30798–804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanegas M, Llano M, Delgado S, Thompson D, Peretz M, Poeschla E. Identification of the LEDGF/p75 HIV-1 integrase-interaction domain and NLS reveals NLS-independent chromatin tethering. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1733–43. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Rivera JA, Bueno MT, Morales E, Kugelman JR, Rodriguez DF, Llano M. Implication of Serine Residues 271, 273 and 275 in the HIV-1 Cofactor Activity of LEDGF/p75. J Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01043-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartholomeeusen K, Gijsbers R, Christ F, Hendrix J, Rain JC, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Debyser Z, De Rijck J. Lens Epithelium Derived Growth Factor/p75 interacts with the transposase derived DDE domain of pogZ. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807781200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartholomeeusen K, De Rijck J, Busschots K, Desender L, Gijsbers R, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Debyser Z, Christ F. Differential interaction of HIV-1 integrase and JPO2 with the C terminus of LEDGF/p75. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:407–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maertens GN, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. Transcriptional co-activator p75 binds and tethers the Myc-interacting protein JPO2 to chromatin. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2563–71. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thakar K, Niedenthal R, Okaz E, Franken S, Jakobs A, Gupta S, Kelm S, Dietz F. SUMOylation of the hepatoma-derived growth factor negatively influences its binding to chromatin. Febs J. 2008;275:1411–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nameki N, Tochio N, Koshiba S, Inoue M, Yabuki T, Aoki M, Seki E, Matsuda T, Fujikura Y, Saito M, Ikari M, Watanabe M, Terada T, Shirouzu M, Yoshida M, Hirota H, Tanaka A, Hayashizaki Y, Guntert P, Kigawa T, Yokoyama S. Solution structure of the PWWP domain of the hepatoma-derived growth factor family. Protein Sci. 2005;14:756–64. doi: 10.1110/ps.04975305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35368–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tatham MH, Geoffroy MC, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT. RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:538–46. doi: 10.1038/ncb1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Botbol Y, Raghavendra NK, Rahman S, Engelman A, Lavigne M. Chromatinized templates reveal the requirement for the LEDGF/p75 PWWP domain during HIV-1 integration in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1237–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poeschla EM. Integrase, LEDGF/p75 and HIV replication. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7540-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cherepanov P, Ambrosio AL, Rahman S, Ellenberger T, Engelman A. Structural basis for the recognition between HIV-1 integrase and transcriptional coactivator p75. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17308–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506924102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosas-Acosta G, Russell WK, Deyrieux A, Russell DH, Wilson VG. A universal strategy for proteomic studies of SUMO and other ubiquitin-like modifiers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:56–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400149-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pollastri G, Martin AJ, Mooney C, Vullo A. Accurate prediction of protein secondary structure and solvent accessibility by consensus combiners of sequence and structure information. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]