SUMMARY

This article considers the problem of assessing causal effect moderation in longitudinal settings in which treatment (or exposure) is time-varying and so are the covariates said to moderate its effect. Intermediate Causal Effects that describe time-varying causal effects of treatment conditional on past covariate history are introduced and considered as part of Robins’ Structural Nested Mean Model. Two estimators of the intermediate causal effects, and their standard errors, are presented and discussed: The first is a proposed 2-Stage Regression Estimator. The second is Robins’ G-Estimator. The results of a small simulation study that begins to shed light on the small versus large sample performance of the estimators, and on the bias-variance trade-off between the two estimators are presented. The methodology is illustrated using longitudinal data from a depression study.

Keywords: Causal inference, Effect modification, Estimating equations, G-Estimation, 2-stage estimation, Time-varying treatment, Time-varying covariates, Bias-variance trade-off

1. Introduction

In this article, we are interested in assessing the causal effect of treatments as a function of variables that may lessen or increase this effect. That is, we are interested in assessing effect moderation (or effect modification) of the causal effect of treatments on outcomes. Studying effect moderation usually involves characterizing a population along different levels of a concomitant pre-treatment variable S, and then studying how the causal effect of treatment A on Y varies according to the different levels of S. Typically, effect moderation is assessed using treatment-moderator interactions terms (e.g., A × S) in regression models for Y given (S, A) (Baron and Kenny, 1986; Kraemer et al., 2002).

A distinctive feature of assessing effect moderation in the time-varying setting is that both treatment (the cause A) and the set of putative moderators (S) vary over time. This feature of the data provides both an opportunity for improved empirical research and also provides a methodological challenge. An opportunity presents itself in the form of more varied and interesting questions that scientists may ask from time-varying data. For instance, consider our motivating example the PROSPECT study (Bruce and Pearson, 1999; Bruce et al., 2004), in which, over time, some patients switch out of depression treatment with their mental health specialist. Using time-varying information about suicidal thoughts, we can ask how does switching out of treatment early versus later affect depression severity scores as a function of time-varying suicidal ideation.

A methodological challenge arises because moderators of the effect of future treatment may themselves be outcomes of earlier instances of treatment (Robins, 1987, 1989b, 1994, 1997); or, in the context of PROSPECT, suicidal ideation measured at the second visit (S2) is a moderator of the effect of switching out of treatment after the second visit (A2) on depression severity (Y), and switching off of treatment after the baseline visit (A1) affects suicidal ideation at the second visit (S2). In this setting, a naïve extension of the treatment-moderator interaction framework, in which, for instance, a regression model such as the following one is used, creates at least two problems for causal inference:

| (1) |

First, conditioning on S2 cuts off any portion of the effect of A1 on Y that occurs via S2, including A1 × S1 interaction effects. Secondly, there are likely common, unknown, causes of both S2 and Y; thus, conditioning on S2 (an outcome of treatment A1) in (1) may introduce biases in the coefficients of the A1 terms. The end result is that A1 and its interactions (e.g., β1 and β3) may appear to be (un)correlated with Y solely because A1 impacts S2 and both S2 and Y are affected by a common unknown cause. These problems can occur regardless of whether A1 and/or A2 are randomized (Robins, 1987, 1989b, 1994, 1997).

A framework for studying time-varying effect moderation that also addresses both of these challenges involves the notion of an conditional intermediate causal effect at each time point. These causal effects are a part of Robins’ Structural Nested Mean Model (SNMM; Robins, 1994). They isolate the average effects of treatment at each time interval as a function of moderators available prior to that time interval.

This article contributes to the literature on modelling and estimating causal effects in the time-varying setting by (1) clarifying and illustrating the use of Robins’ SNMM to assess time-varying effect moderation, (2) proposing a 2-Stage parametric regression estimator for the parameters of a SNMM, (3) comparing the proposed parametric estimator to Robins’ Semi-parametric G-Estimator (Robins, 1994) in terms of a bias-variance trade-off, and (4) suggesting how the proposed 2-Stage estimator can be used to obtain high quality starting values for the G-Estimator.

In Section 2, the causal effects of interest are defined in the context of Robins’ SNMM. The two estimators of the intermediate causal effects are presented and discussed in Section 3. The results of a small simulation study that sheds light on the bias-variance trade-off between the two estimators is presented in Section 4. The methodology is illustrated in Section 5 using data from the PROSPECT study. Finally, a discussion of the paper, including methodological improvements suggested by the illustrative analysis, is presented in Section 6.

2. Effect Moderation with Time-varying Treatment and Time-varying Moderators

2.1 Notation and Potential Outcomes

To define the structural parameters and to state the structural assumptions necessary for valid causal inference we use the potential outcomes framework for causation (Rubin, 1974; Holland, 1986; Robins, 1987, 1989a, 1994, 1997, 1999)). In general, we suppose there are K time intervals under study. Treatment is denoted by at, at each time interval t, where t = 1,…,K. We denote the treatment pattern/vector over K intervals by āK = (a1,…,aK); where at = 0 represents standard, or baseline, treatment. Let 𝒜K be the countable collection of all possible treatment vectors. Corresponding to each fixed value of the treatment vector, āK, we conceptualize potential, possibly counterfactual, intermediate responses {S2(a1), ‥‥, SK(āK−1)} and a potential final response Y(āK). Thus, for example, S(āt) is the response at the end of the tth interval that a subject would have, had he/she followed the treatment pattern, āt. A subject’s complete set of potential responses, intermediate and final, is denoted by O = {S2(a1), S3(ā2),…,SK(āK−1), Y(āK) : āK ∈ 𝒜K}. The intermediate outcomes denoted by S are the putative time-varying moderators of the effect of āK on Y(āK). Below, we define more formally in the context of Robins’ Structural Nested Mean Model what it means for St(āt−1) to be a moderator of the effects of (at,…,aK) on the response. Putative baseline moderators are denoted by the vector S1.

2.2 The Conditional Intermediate Causal Effects

Henceforth, for simplicity, we focus on the case where K = 2. Thus, we have the following objects at our disposal: (S1, a1, S2(a1), a2, Y(a1, a2)). The response Y(a1, a2) is taken to be continuous with unbounded support. We are only concerned with modeling the mean of the response Y(āK) as a function of āK and SK(āK−1). Thus, we do not consider treatment or covariate effects on the variance of the response. Using potential outcomes we can express the average causal effect of ā2 on Y(a1, a2) as E[Y(a1, a2) − Y(0, 0)], where at = 0 is the baseline level of treatment. Using S̄2(a1) and applying the law of iterated expectations, we can write this difference as an arithmetic decomposition of conditional means:

| (2) |

with the outer expectations in Equation (2) over S̄2(a1) and S1, respectively. The inner expectations are conditional intermediate causal effects of treatment. Let μ2(S̄2(a1),ā2) denote E[Y(a1, a2) − Y(a1, 0) | S̄2(a1)], the effect of treatment (a1, a2) relative to the treatment (a1, 0) within levels of S̄2(a1); and let μ1(S1, a1) denote E[Y(a1, 0) − Y(0, 0) | S1], the effect of treatment (a1, 0) relative to (0, 0) within levels of S1. Note the following constraints on the causal effects: μ2(S̄2(a1), a1, 0) = 0 and μ1(S1, 0) = 0. The effects μ1 and μ2 are intermediate causal effects because they isolate the causal effect of treatment at time 1 and time 2, respectively. The “isolation” here is achieved by setting future instances of treatment at their inactive levels – in our case, the zero level. Hence, μ1 corresponds to a contrast of the potential outcomes in a1 for which a2 (a future level of treatment) is set to its inactive level. On the other hand, μ2, which corresponds to the effect at the last time point, is defined exclusively as a contrast in a2 where, in general, a1 can take on any value in its domain.

2.3 Robins’ Structural Nested Mean Model

In this section we use the Structural Nested Mean Model (SNMM), developed by Robins (1994), to combine the intermediate average causal effect functions additively in a model for the conditional mean of Y(a1, a2) given S̄2(a1). Using the SNMM, the conditional mean of Y(a1, a2) given S̄2(a1) is expressed as:

| (3) |

where β0 = E[Y(0, 0)], the mean response to baseline treatment averaged over levels of S̄2(a1); ε2(S̄2(a1), a1) = E[Y(a1, 0) | S̄2(a1)] − E[Y(a1, 0) | S1]; and ε1(S1) = E[Y(0, 0) | S1] − E[Y(0, 0)]. In the Appendix we describe the model for general K time points. The SNMM depicts how the intermediate effect functions relate to the conditional mean of Y(a1, a2) given the past. Note that ε1 and ε2 are defined so that the decomposition on the right hand side of Equation (3) is indeed equal to E[Y(a1, a2) | S̄2(a1)]. They satisfy the constraints E[ε2(S̄2(a1), a1) | S1] = 0, and ES1[ε1(S1)] = 0, and they are considered nuisance parameters because they contain no information regarding the conditional intermediate causal effects of ā2 on the mean of Y(a1, a2).

3. Estimation Strategies for the SNMM

We consider two estimation strategies for β.

3.1 Observed Data and Assumptions Underlying Estimation

Denote the observed treatment history by the random vector, ĀK := (A1, A2,…,AK); denote the observed time-varying covariate history by the random vector, S̄K := (S1, S2,…,SK); and denote the observed outcome by the random variable Y. Both estimation strategies described below rely on the assumptions of consistency and sequential ignorability (Robins, 1994, 1997) in order to make causal inferences.

The consistency assumption states that , where I(āK = ĀK) denotes the indicator function that āK is equal to ĀK. The consistency assumption is the link between objects defined as potential outcomes, and objects that are actually observed. Assuming consistency for the intermediate outcomes {S2(a1), S3(ā2),…,SK(āK−1) : āK ∈ 𝒜K} as well, then a similar relationship holds between the counterfactual objects in the SNMM and a corresponding set of observed data. The actual data observed (not to be confused with the complete set of potential outcomes, O, defined above) for one individual in our study is D = (S1, A1, S2, A2,…,SK, AK, Y) where for each t > 1, St takes on some value in the set {St(āt−1) : āt−1 ∈ 𝒜K}, At takes on some value in the collection 𝒜K, and Y takes on some value in the set {Y(āK) : āK ∈ 𝒜K}.

Another key assumption used to identify the causal parameters of the SNMM using observed data is the sequential ignorability assumption: For each t = 1,2,…,K, At is independent of O given (S1, A1, S2, A2,…,St), where, recall, O is the entire set of potential outcomes. The assumption implies that observed treatment At may depend on the set of observed moderators S̄t, but that no other variables known or unknown, measured or unmeasured, directly affect both At and O.

While the causal meaning of the parameters in models for the μt’s depend on the above assumptions, the estimation of parameters requires other modelling (or statistical) assumptions. These modelling assumptions include the choice of parametric models for the causal effects. One possible parameterization of the intermediate causal effects is linear in the parameters. For example, in our presentation of both estimators below, we use

| (4) |

where βt represents a qt-dimensional parameter vector at time t; and Ht is a known function of S̄t, Āt−1). Using this general form ensures that the following constraint is always satisfied: μt(S̄t, Āt−1, 0; βt) = 0. Typically, the first element in Ht is one. Additional modelling assumptions are described below in turn, as the estimators are presented. Note that since the following subsections are concerned only with estimation, only the observed data D (not the potential outcomes O) are considered.

3.2 Parametric 2-Stage Estimator: β̂

We propose a parametric 2-Stage Estimator that employs the following general approach for estimating the parameters of a SNMM: In the first stage, for every t, we model the conditional distribution of St given (S̄t−1, Āt−1) denoted by ft(St | S̄t−1, Āt−1), based on a set of finite-dimensional parameters γt. Then, based on one or more features of this distribution (e.g., the conditional mean mt), and based on an additional (optional) set of finite-dimensional parameters ηt for added flexibility, we pose a model for the nuisance functions at each time point, say εt(S̄t−1, Āt−1; ηt, γt). This general model for the nuisance functions is based on the fact that the constraints on εt are a function of ft, for every t; recall that ∫ εt dft = 0, for every t. In the second stage, these models for the nuisance functions are put together with models for the intermediate causal effects in a SNMM for the conditional mean of Y given (S̄K, ĀK) (see Equation (3)). Estimates for β are then based on solutions to the following estimating equations:

| (5) |

where for any function V() of the observed data D, ℙnV(D) denotes . In the following, we present a particular linear implementation of this general approach that uses linear models for the εt’s.

3.2.1 A Linear Regression Implementation of the 2-Stage Estimator

For simplicity, assume that St at each time point is univariate (i.e., one time-varying moderator per time t is used); an extension of the method to multivariate St is presented in the Supplementary Materials. The proposed parametrization of the nuisance functions used here is based on linear models for the conditional mean of St given the past. These conditional means are denoted by mt and are based on an unknown lt-dimensional vector of parameters γt, so that mt(S̄t−1, Āt−1; γt) = E(St | S̄t−1, Āt−1). We employ generalized linear models (GLMs, McCullagh and Nelder (1989)) for the mt: Let Ft be a row-vector of the data (S̄t−1, Āt−1). Thus, when St is continuous, we use mt(S̄t−1, Āt−1; γt) = Ftγt. When St is binary, we use mt(S̄t−1, Āt−1; γt) = Pr(St = 1 | S̄t−1, Āt−1) = expit(Ftγt). We use following linear form for parameteric models for the error terms εt (based on the γt): εt(S̄t, Āt−1; ηt, γt) = Gtηt × (St − mt(S̄t−1, Āt−1; γt)), where Gt is a row-vector summary of the past (S̄t−1, Āt−1), and ηt is an unknown wt-dimensional vector of parameters. Denote the “residual” St − mt(S̄t−1, Āt−1; γt) by δt(S̄t, Āt−1; γt). A simple model for εt will have Gt = (1), so that εt = ηt0δt(S̄t, Āt−1; γt), for example. Note that δt ensures that the parameterization satisfies the necessary constraint. Note also that using this linear model for the nuisance functions, we can multiply every element of Gt by the residual δt, denoted , and re-write the parametric model for the nuisance functions as . If γt were known, this would imply a linear (in the β’s and η’s) parametric model for the SNMM. For example, for . This idea forms the basis for the linear implementation of the 2-Stage approach, given here for general K time points:

Stage 1 Regression. Generalized linear model regression analyses are used in the first stage to obtain the estimates γ̂t based on regressions of St on (St−1, At−1). These are carried out for each time point t = 1, 2,…,K. When St is binary, a logistic regression is used to obtain γ̂t.

Use the predicted means m̂t(γ̂t) from the first stage regression to construct the predicted residuals δ̂t = St − m̂t.

Combine the model vectors for the conditional intermediate effects (and a column for the intercept) and denote this quantity by X; that is, X = (1, A1H1,…,AKHK). Note that represents the functional of interest of the SNMM.

Multiply each element in Gt by the predicted residual δ̂t and denote this quantity by ; that is, . Note that if were known, then would represent an estimate of the sum of the nuisance functionals of the SNMM.

Augment the row-vector X to include the ’s; that is, . Define the -dimensional column-vector of parameters θ = (βT, ηT)T.

Stage 2 Regression. The final step involves a standard linear regression of Y on Xaug to obtain the estimates θ̂ = θ̂(γ̂), which gives β̂ = β̂(γ̂) and an estimate for the nuisance ηt’s simultaneously.

3.3 Robins’ Semi-parametric Efficient G-Estimator: β̃

The following estimator, derived in Robins (1994), does not require correct models for the nuisance functions, in order to achieve consistency. It is an extension to the longitudinal setting of the semi-parametric regression E-Estimator considered in Robins et al. (1992) and Newey (1990). In K = 2, the estimate is based on these estimating functions:

| (6) |

where pt(S̄t, Āt−1; αt) is a model for Pr[At = 1 | S̄t, Āt−1]; b2(S̄2, A1; ξ2) is a model for E[Y − H2β2A2 | S̄2, A1], and b1(S1; ξ1) is a model for E[Y − A2H2β2 − H1β1A1 | S1]; Δ(S1; κ) is a model for ; and 0q1 is a q1-dimensional row-vector of zeros. The set of equations (6) is (q1 + q2)-dimensional because Ht is qt-dimensional for t = 1, 2. We denote this system of equations by ℙnψβ(D; α, ξ, κ), where (of dimension r1 + r2), , and κ are all unknown parameters. The conditional variances and are defined as and where the second inequality in each follows by assumption (without this partially homogenous variance assumption, the estimating equations are intractable). In our implementation, we further assume that these variances are constant in (S̄2, A1) and S1, respectively. In order to use ℙnψβ(D; α, ξ, κ) for estimation, we substitute estimates of the parameters α, ξ, and κ in pt(αt), bt(ξt), and Δ(κ)—denoted p̂t(α̂t), b̂t(ξ̂t), and Δ̂(κ̂)—and solve for β in the estimating equations 0 = ℙnψβ(D; α̂, ξ̂, κ̂). The resulting estimator β̃ := β̃(α̂, ξ̂, κ̂) is known as Robins’ locally efficient semi-parametric G-Estimator for β. The Appendix describes the estimator for general K time points. Modelling the bt(ξt) terms is important for variance reduction in β̃; the next subsection describes a method for obtaining ξ̂t based on the 2-Stage Estimator (in addition to obtaining (α̂t, κ̂)).

3.3.1 Implementing Robins’ G-Estimator

To obtain α̂, we use logistic regression models at each time point t to model the probability of receiving treatment at time t (At = 1) given Zt, where Zt is a row-vector of the data (S̄t, Āt−1)—that is, we use pt(S̄t, Āt−1; αt) = expit(Ztαt). Then the predicted probabilities from the logistic regression are used to get p̂t. To obtain Δ̂, we use ordinary multivariate regression models for to get κ̂, and then predict Δ using Δ̂(S1; κ̂) = λ̂(S1, 1; κ̂) − λ̂(S1, 0; κ̂). Formally, for a fixed t, the quantity bt is a model for the sum of the nuisance functions and intermediate causal effects for all t' < t plus the nuisance function at time t. Hence, the 2-stage estimator presented above can be used to obtain the “guesses” b̂t(ξ̂t) needed to solve the equations. To do this, we use the relevant portions of the (2-stage) estimated conditional mean at each time t to create the estimates for b̂t(ξ̂t). Thus, at time 1, for instance, one can simply use b̂1(S1; ξ̂1) = β̂0+ε̂1(S1; η̂1, γ̂1), where would be estimated using the 2-stage estimator. Finally, the numerical search for the solution to ℙnψβ(D; α̂, ξ̂, κ̂) = 0 is itself an iterative process that requires starting values. Here, we use the estimates obtained from the 2-stage estimator, β̂, as the starting values for this search. The free and publicly available MINPACK FORTRAN subroutine HYBRD was adapted and used to find the zeros of the system of functions.

3.4 Estimated Standard Errors for β̂ and β̃

Estimated asymptotic standard errors for β̂ and β̃ are computed using the delta method, based on one-step Taylor series expansions. They are shown in the Supplementary Materials. takes into account the variability in the estimation of γ. takes into account the variability in the estimation of α.

3.5 A Comparison of the Properties of the Two Estimators

The G-Estimating equations ℙnψβ provide unbiased estimating functions for β given correct models for the intermediate causal effects and the pt’s, regardless of our choice of models for the bt’s and Δ. Indeed, even if Δ = 0 and bt = 0 for all t, we still have Eψβ = 0. Conversely, given correct models for the intermediate causal effects and the bt’s, unbiasedness is still achieved with the G-Estimator regardless of our choice of models for the pt’s and Δ. This is known as the double-robustness property of the G-Estimator (Robins, 1994). Now, provided true models for both bt and pt (for all t; and true model for Δ), the resulting estimates are also asymptotically efficient. By efficient, we mean that the asymptotic variance of the resulting G-Estimates of β achieve the semi-parametric efficiency variance bound (Bickel et al. (1993)) for this class of models.

The 2-Stage Estimator relies on correct models for both the intermediate causal effects and the nuisance functions in order to provide unbiased estimates for β. At the correct model fit, the 2-Stage estimator enjoys better efficiency than the G-Estimator. This gain in precision, however, may be offset by a lack of robustness to mis-specifications in the εt’s. Exactly how to balance the trade-off between bias and variance (i.e., the choice between these two estimators) is an open question. The simulation experiments in the next section shed light on this question. We do this by purposefully mis-specifying the 2-Stage Estimator and exploring at what level of mis-specification the G-Estimator begins to dominate over the 2-Stage Estimator in terms of mean squared error (MSE). In addition, since we find that the choice of models for bt has a profound impact on the efficiency of the G-Estimator, the simulations also explore the utility of the 2-Stage estimator as a feasible method for obtaining guesses for bt versus setting bt = 0.

4. Simulation Experiments

4.1 The Generative Model

All simulations are based on N = 1000 simulated data sets. The generative model mimics the PROSPECT data (discussed briefly in the Introduction, and used in our data analysis illustration below), with K = 3. We generated continuous time-varying covariates {S1, S2, S3} and continuous outcome Y such that their implied marginal distributions and bivariate correlations are similar to those found in PROSPECT, where St is suicidal ideation at time t, and Y is end-of-study depression scores. Specifically, [S1] ~ N(m1 = 0.5, sd = 0.82), [S2|S1, A1] ~ N(m2 = 0.5 + 0.10S1 − 0.5A1 + 0.35S1A1, sd = 0.65), and [S3|S̄2, Ā2] ~ N(m3 = 0.5 + 0.17S2 + 0.1S1 − 0.5A2 + 0.5S2A2, sd = 0.65), where binary treatment At ∈ (0, 1) at each time point is generated as a binomial random variable with Pr(At = 1 | S̄t, Āt−1 = pt = expit(0.5 − 1.5St). The nuisance functions were chosen as ε1 = 0.1 × (S1 − m1), ε2 = (0.2 + 0.18S1 + 0.4A1 + 0.35A1S1 + sin(4.5S1)) × (S2 − m2), and ε3 = (0.3 + 0.18S2 + 0.4A2 + 0.35A2S2 + sin(2.5S2)) × (S3 − m3). 1 The intermediate causal effect functions in the SNMM were set to: μt = Htβt = (At, AtSt) × (βt,0, βt,1)T = At × (βt,0 + βt,1St) for t = 1, 2, 3. The true value for all six causal parameters was set to βt,j = 0.45, where j = 0, 1. The outcome Y was generated as a normal random variable with a conditional mean structure according to a SNMM, and residual standard deviation for Y set to 1.0.

4.2 The Simulation Design

Two simulation experiment, A and B, were carried out, both using the same generative model described above. Three estimators were compared in both experiments: (1) the 2-Stage Regression Estimator, (2) the G-Estimator with bt = 0, and (3) the G-Estimator using guesses for bt that are derived from the 2-Stage Estimator. For both versions of the G-Estimator: (a) true logistic regression models were fit to obtain the p̂t predictions; (b) starting values for the iterative solving procedure were derived from the 2-Stage Estimator; and (c) multivariate linear regression models that included all main effects and all second-order interaction terms were used for , and to obtain Δ̂. True models for the intermediate causal effects, the μt’s, were always specified for all three estimators across both experiments.

4.2.1 Experiment A

The first set was designed to study the small versus large sample properties of the different estimators when the correct 2-Stage Estimator is fit to the data. In these simulations, the sample size for each data set was varied (n = 50, n = 300, and n = 600) and performance measures for point estimates and standard errors (mean, variance, mean squared error, coverage percentage) were compared across the estimators. The (middle) sample size of n = 300 is approximately the size of the data set used in our illustrative analysis of Section 5; n = 50 and n = 1000 were chosen to look at the effect of relatively smaller and larger data sets.

4.2.2 Experiment B

The goal of the second set of experiments is to shed light on the bias-variance trade-off between the 2-Stage Estimator and the two versions of Robins’ G-Estimator. In this set of experiments, the nuisance functions in the 2-Stage Estimator were mis-specified and the relative performance of the estimators (in terms of MSE) was assessed. Only data sets of size n = 300 were considered in Experiment B. Mis-specification of the nuisance functions is measured using the Scaled Root-Mean Squared Difference = , where for a fixed value of ν, εt(ν) denotes the mis-specified nuisance function at time t. SRMSD has the interpretation of an effect-size, so that SRMSD values of 0.2 and 0.5, for example, correspond to small and moderate levels of mis-specification, respectively (see Cohen (1988)). We varied values of SRMSD using ν, by replacing every St in the εt’s (including those in the models for the mt’s) with St × U, where U is a draw from the normal distribution N(1, sd = ν). Note that when ν = 0 the correct 2-Stage Estimator is fit to the data.

4.3 Simulation Results and Discussion

4.3.1 Experiment A

Table 1 shows the results of Experiment A. As expected according to large sample theory, all three estimators are unbiased for all βt,j when n = 1000; and empirical standard deviations (SD) and mean standard errors (MEAN SE) show good agreement for all three estimators when n = 1000. All 95%CI coverage probabilities at n = 1000 show coverages between the expected 93.6% and 96.4% range for N = 1000 replicates, with the exception of the bt = 0 G-Estimates for β2,1. Increasing the sample size from n = 1000 to n = 1200 (results not shown here) brought the bt = 0 G-Estimate coverage probability for β2,1 to 93.9%, which is within the acceptable range. Performance in terms of mean bias is only slightly worse at n = 300 relative to n = 1000 across all three estimators, although as expected, the variance (both SD and MEAN SE) increases significantly with the smaller sample size. This trend continues with n = 50, as well. The 95%CI’s show under-coverage at smaller sample sizes, especially at n = 50; and, for the 2-Stage Estimator and the G-Estimator using 2-Stage Guesses, the coverage gets worse for the parameters at later time points.

Table 1.

Results of Simulation Experiment A: Small versus large sample performance of the 2-Stage Estimator, Robins’ G-Estimator with bt = 0, and Robins’ G-Estimator relying on starting guesses for bt from the 2-Stage Estimator. Parameters have true value βtj = 0.45 for all t = 1, 2, 3 and j = 0, 1.

| True 2-Stage Estimator |

Robins’ G-Estimator with bt = 0 for all t |

Robins’ G-Estimator using 2-Stage Guesses |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMTR | AVG EST | SD | AVG SE | 95% COV | MSE | AVG EST | SD | AVG SE | 95% COV | REL MSE | AVG EST | SD | AVG SE | 95% COV | REL MSE |

| n = 50 | |||||||||||||||

| β1,0 | 0.458 | 0.515 | 0.471 | 91.8 | 0.265 | 0.412 | 0.658 | 0.604 | 92.2 | 1.6 | 0.444 | 0.633 | 0.553 | 89.6 | 1.5 |

| β1,1 | 0.453 | 0.580 | 0.532 | 91.0 | 0.337 | 0.413 | 0.870 | 0.768 | 91.3 | 2.3 | 0.463 | 0.846 | 0.704 | 86.4 | 2.1 |

| β2,0 | 0.441 | 0.536 | 0.455 | 89.4 | 0.287 | 0.413 | 0.603 | 0.557 | 92.9 | 1.3 | 0.457 | 0.564 | 0.422 | 83.9 | 1.1 |

| β2,1 | 0.412 | 0.739 | 0.637 | 90.0 | 0.547 | 0.393 | 0.990 | 0.841 | 90.4 | 1.8 | 0.402 | 0.863 | 0.637 | 84.7 | 1.4 |

| β3,0 | 0.475 | 0.489 | 0.381 | 87.0 | 0.240 | 0.409 | 0.683 | 0.562 | 93.0 | 2.0 | 0.442 | 0.496 | 0.311 | 77.1 | 1.0 |

| β3,1 | 0.430 | 0.634 | 0.493 | 85.8 | 0.402 | 0.404 | 1.155 | 0.893 | 91.7 | 3.3 | 0.483 | 0.688 | 0.422 | 73.7 | 1.2 |

| n = 300 | |||||||||||||||

| β1,0 | 0.451 | 0.175 | 0.169 | 93.2 | 0.031 | 0.430 | 0.242 | 0.232 | 94.6 | 1.9 | 0.438 | 0.236 | 0.225 | 94.1 | 1.8 |

| β1,1 | 0.452 | 0.197 | 0.186 | 93.5 | 0.039 | 0.463 | 0.314 | 0.297 | 92.8 | 2.6 | 0.468 | 0.310 | 0.292 | 93.4 | 2.5 |

| β2,0 | 0.441 | 0.164 | 0.170 | 96.4 | 0.027 | 0.435 | 0.209 | 0.216 | 95.6 | 1.6 | 0.445 | 0.182 | 0.184 | 95.4 | 1.2 |

| β2,1 | 0.456 | 0.229 | 0.222 | 93.8 | 0.053 | 0.449 | 0.336 | 0.330 | 94.7 | 2.2 | 0.454 | 0.279 | 0.266 | 94.1 | 1.5 |

| β3,0 | 0.451 | 0.158 | 0.148 | 93.3 | 0.025 | 0.457 | 0.204 | 0.200 | 94.5 | 1.7 | 0.447 | 0.162 | 0.149 | 92.5 | 1.0 |

| β3,1 | 0.439 | 0.184 | 0.182 | 93.4 | 0.034 | 0.429 | 0.326 | 0.314 | 94.4 | 3.1 | 0.444 | 0.207 | 0.201 | 92.3 | 1.3 |

| n = 1000 | |||||||||||||||

| β1,0 | 0.452 | 0.089 | 0.092 | 95.3 | 0.008 | 0.446 | 0.129 | 0.127 | 94.9 | 2.1 | 0.451 | 0.124 | 0.124 | 94.3 | 1.9 |

| β1,1 | 0.452 | 0.102 | 0.100 | 94.6 | 0.010 | 0.446 | 0.173 | 0.166 | 93.8 | 2.9 | 0.447 | 0.171 | 0.164 | 94.2 | 2.8 |

| β2,0 | 0.449 | 0.091 | 0.092 | 95.9 | 0.008 | 0.449 | 0.119 | 0.117 | 94.8 | 1.7 | 0.450 | 0.102 | 0.101 | 94.7 | 1.3 |

| β2,1 | 0.440 | 0.117 | 0.120 | 95.7 | 0.014 | 0.430 | 0.191 | 0.180 | 92.3 | 2.7 | 0.439 | 0.150 | 0.146 | 94.2 | 1.6 |

| β3,0 | 0.446 | 0.081 | 0.080 | 95.0 | 0.006 | 0.446 | 0.107 | 0.108 | 95.6 | 1.8 | 0.444 | 0.084 | 0.082 | 94.7 | 1.1 |

| β3,1 | 0.454 | 0.099 | 0.099 | 94.8 | 0.010 | 0.451 | 0.175 | 0.169 | 94.2 | 3.2 | 0.456 | 0.114 | 0.112 | 94.0 | 1.3 |

REL MSE denotes mean squared error relative to the 2-Stage Estimator.

REL MSE denotes relative mean squared error of the G-Estimator relative to the 2-Stage Estimator. As expected, the 2-Stage Estimator is equivalent or better than both G-Estimators in terms of relative mean squared error (REL MSE) across all the scenarios. REL MSE values for the G-Estimator using correct 2-Stage Guesses for bt decrease for the parameters at later time points. The same trend is not true under the G-Estimator with bt = 0; and in particular, the largest REL MSE values in Table 1 are observed for the G-Estimators of β3,1 with bt = 0 (across all time points).

In large samples (n = 1000), the simulation results suggest that the G-Estimator using the 2-Stage Guesses has variance in between the variance of the other two estimators. This observation is in-line with large-sample theoretical results that describe the usefulness of (correctly) modeling the bt’s to achieve variance reduction (Robins, 1994). In fact, an interesting trend over time exists such that parameter estimates under both G-Estimators at t = 1 have nearly identical variance, whereas for the t = 2 parameters the variance of the G-Estimator using the 2-Stage Guesses is approximately half-way between the variance of the G-Estimator with bt = 0 and the 2-Stage Estimator; then at the final time point t = 3 the G-Estimator with bt = 0 and the 2-Stage Estimator come closer to having similar variances.

Despite having markedly larger REL MSE’s (especially for the parameters at later time points), the n = 50 coverage percentages are much better for Robins’ G-Estimator with bad guesses (bt = 0) relative to Robins’ G-Estimator with correct bt guesses. This suggests that important improvements are needed in small sample estimation of standard errors when estimated bt’s are used with the G-Estimator.

4.3.2 Experiment B

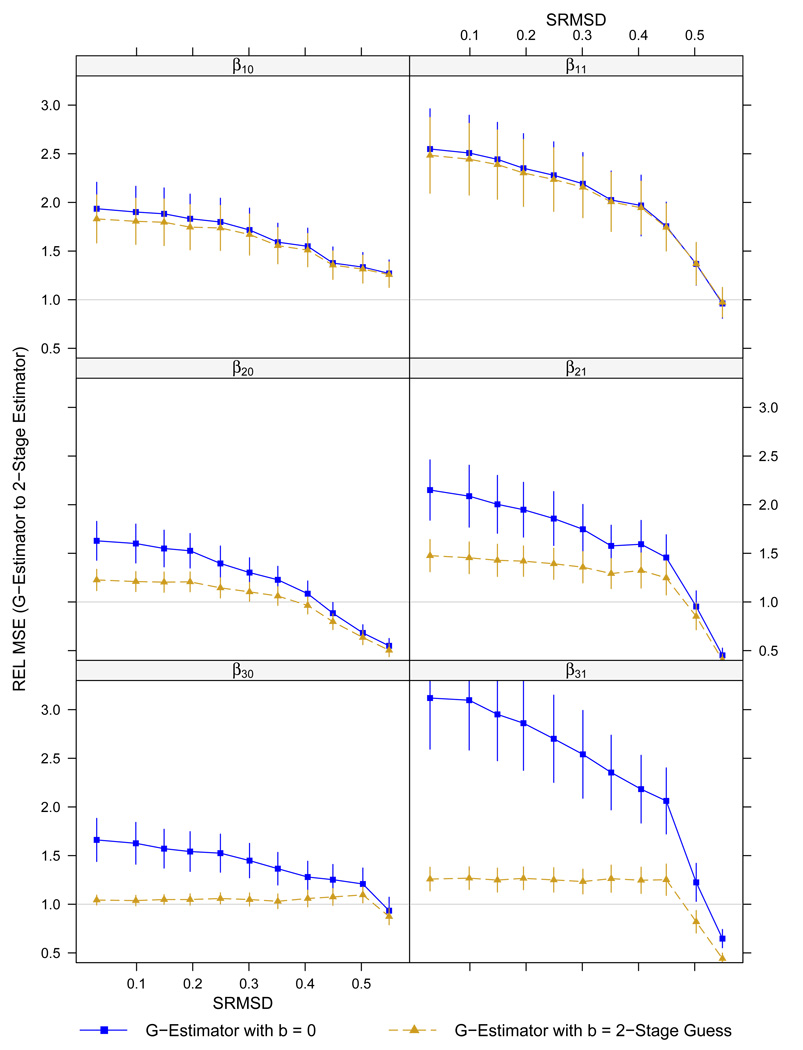

Figure 1 shows the results of Experiment B in a 3 × 2 array of plots. The six panels correspond to the six causal parameters of interest in the SNMM, with each row corresponding to the parameters at a particular time point. Each point corresponds to a separate experiment with N = 1000 data sets (replicates) of size n = 300. The abscissa specifies different levels of mis-specification of the εt terms in the 2-Stage fits; measures of mis-specification are shown in terms of both ν and RSMSD. The ordinate measures the relative mean squared (REL MSE) of the G-Estimator relative to the 2-Stage Estimator. Within each panel are two plots/curves, one for each of the two G-Estimators considered above. The error bars for REL MSE are defined as where BVE is a bootstrap variance estimate (based on resampling with replacement) of the REL MSE.

Figure 1.

Results of Simulation Experiment B, with n = 300: Understanding the bias-variance trade-off in terms of relative mean squared error (REL MSE) of the G-Estimator relative to the 2-Stage Estimator, as a function of mis-specifications of the nuisance functions (measured by SRMSD(ν)) in the 2-Stage Estimator.

Values of ν were varied from 0.0 to 5.0; this, in turn, corresponded to values of SRMSD between 0.0 and 0.55 – that is, from no mis-specification to just beyond “moderate” amounts of mis-specification.

As expected, the curves decline for larger values of ν. The point at which the curves drop below 1.0 denotes the point at which the 2-Stage Estimator no longer dominates in terms of MSE. The results of the experiment indicate that at roughly a “moderate” amount of mis-specification (SRMSD ≈ 0.5), the G-Estimators begin to dominate, although there is some variation by parameter in the trajectories. In the case of β10, for instance, the curve never drops below 1.0, indicating that the 2-Stage Estimator always dominates. In the case of the t = 3 parameters using the G-Estimator based on 2-Stage guesses for bt, on the other hand, the two estimators perform so similarly at the true model (ν = 0), that the REL MSE quickly falls below 1.0. As expected, the G-Estimator with bt = 0 never performed better than the other two estimators.

5. An Illustration using the PROSPECT Data

A subset of the PROSPECT data with n = 277 is used to illustrate the methodology for K = 3 time points. The sample used in this illustration uses only patients randomized to the treatment arm in PROSPECT. At denotes binary treatment assignment at time t, where At = 1 means the subject received treatment at time t; that is, had contact with a mental health specialist at time t. denotes the Scale for Suicidal Ideation at time t, a continuous measure of suicidal thoughts for which higher values of means more suicidality. The outcome Y is defined as the Hamilton Depression Scale score at the final, 12-month, visit: Y = HAMD12. Higher levels of Y means more depression. In the actual analysis, square-root-transformed versions of the scores were used for both the SSIt’s and HAMDA12. The monotonic sqrt-transformation preserves the original SSI and HAMDA interpretations, and produces more stable covariate and final outcome measures by correcting for skewness; this, in turn, improves asymptotic approximations to the test statistics employed in the data analysis.

We use simple linear parameterizations as in Equation (4) for the intermediate causal effects μ1 through μ3. Specifically, we use μ1 = A1 × (1, S1) × (β10, β11)T, μ2 = A1 × (1, (S1 + S2)/2) × (β20, β21)T, and μ3 = A3 × (1, (S1 + S2 + S3)/3) × (β30, β31)T. These intermediate causal effects cannot vary according to previous levels of treatment, because in this sample treatment is monotonic; in other words, 𝒜3 = {(0, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0), (1, 1, 0), (1, 1, 1)} in PROSPECT. μt models the causal effect of switching off treatment at time t, as a function of a summary score of mean history of suicidal ideation over time. In this analysis, we expect that for S̄3 = 0, treatment reduces levels of depression—that is, the time-varying “baseline” effects of treatment are negative: βt0 < 0. In addition, we expect that βt1 > 0—that is, that the reduction in depression as a result of treatment is not as strong for patients with higher levels of suicidal thoughts.

The results of this illustrative analysis are shown in Table (2) for both the 2-Stage Regression Method and Robins’ Method. Simple linear regression models were used for the components of εt in the 2-Stage Method, and for the pt, ξt, and Δt in Robins’ Method. These models are not shown here for reasons of space.

Table 2.

An illustrative analysis of the time-varying effects of treatment on depression given time-varying suicidal ideation. Results are shown using the 2-Stage Regression Estimator β̂ and Robins’ Semi-parametric G-Estimator β̃.

| 2-Stage Estimator | Robins’ G-Estimator | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters of Interest | β̂ | Pr(> |z|) | β̃ | Pr(> |z|) | |||||

| A1 | β10 | 0.236 | 0.418 | 0.57 | 0.194 | 0.446 | 0.66 | ||

| A1 : SSI1 | β11 | 0.058 | 0.287 | 0.84 | 0.276 | 0.360 | 0.44 | ||

| A2 | β20 | 0.780 | 0.521 | 0.13 | 1.024 | 0.493 | 0.04 | ||

| β21 | −0.731 | 0.607 | 0.23 | −1.395 | 0.598 | 0.02 | |||

| A3 | β30 | −0.919 | 0.364 | 0.01 | −1.053 | 0.350 | < 0.01 | ||

| β31 | 0.886 | 0.497 | 0.08 | 1.165 | 0.438 | < 0.01 | |||

Both estimators show good agreement in terms of direction of the effects, but not in terms of magnitude. Although the 2-Stage Estimates and the G-Estimates do not differ in magnitude when their standard errors are taken into account, the 2-Stage Estimator consistently yields estimates that are closer to zero compared to the estimates provided by the G-Estimator. (The exception is β10.) In our experience with a variety of simulated data sets (including those described in the previous section, and others not shown here), the 2-Stage Estimator did not show consistently smaller estimates compared to the G-Estimates, but this may require more in-depth study.

Neither estimator suggests effect moderation of the effect of treatment during the first four months of treatment given levels of SSI1. The effect of no treatment between the 4- and 8-month visits is positive for both estimators (significantly different from zero under Robins’ G-Estimator). The estimated main effect of treatment between the 8- and 12-month visits shows a significant negative effect (significantly different from zero for both estimators). Finally, both the 2-Stage Estimator and Robins’ G-Estimator suggest that (S1 + S2 + S3)/3 moderates the effect of A3.

6. Discussion

This article presents and discusses the use of intermediate causal effects to study time-varying causal effect moderation. It is shown how the intermediate causal effects are a part of Robins’ Structural Nested Mean Model (Robins (1994)). In fact, the time-varying intermediate causal effect functions presented here are a version of Robins’ blip functions. Two estimators—one parametric and one semi-parametric—of the intermediate causal effects are presented and compared. Two simulation experiments that shed light on the bias-variance trade-off between the parametric 2-Stage Regression Estimator and the semi-parametric G-Estimator were carried out.

The SNMM and Robins’ G-Estimator have also been used previously to study the effects of randomization to an intervention in the presence of non-compliance (Goetghebeur and Fischer-Lapp, 1997; Fischer-Lapp and Goetghebeur, 1999), including when the outcome is binary (Robins and Rotnitzky, 2005; Vansteeldandt and Goetghebeur, 2003); and the G-Estimator has been used recently for studying causal effect mediation (Ten Have et al., 2007; Joffe et al., 2007). Petersen and van der Laan (2005) have also proposed a method for assessing time-varying effect moderation, called Historically-Adjusted Marginal Structural Models (HA-MSMs). With HA-MSMs, Petersen and van der Laan have generalized MSMs (Robins (1999)) to allow conditioning on time-varying covariates; this is accomplished by positing different MSMs, one per time point, and estimating them simultaneously. HA-MSM’s differ from SNMMs in one important respect; namely, SNMMs are fully structural models for the conditional mean of Y given (S̄K, ĀK), whereas with HA-MSMs there is no requirement, for instance, that the model posed for the causal effect of a1 in the MSM at t = 1 be equivalent to the model for the causal effect of a1 that is implied by the last MSM at t = K. Future work that further compares HA-MSMs and SNMMs for modelling time-varying effect moderation will be important.

The 2-Stage Estimator requires more knowledge about portions of the conditional mean of Y given (S̄K, ĀK than does Robins’ G-Estimator. If this additional knowledge (concerning the nuisance functions εt) is incorrect, it is possible that β̂ is biased for the true β. On the other hand, scientists may tolerate bias in β̂ if its variance is smaller than an unbiased β̃. The simulation studies presented above begin to shed light on this bias-variance trade-off. The simulation experiments suggest that it may be useful to consider parametric estimators such as the 2-Stage Estimator over the G-Estimator under moderate mis-specifications in models for the nuisance functions using the parametric estimator. Of course, the scientist will never really know the amount of mis-specification s/he may incur in the process of modeling the error terms. In addition, it may be possible that the scientist will mis-specify the μt as well.

An important limitation of our simulation Experiment B is that our results are contingent upon our method for exploring the space of mis-specified 2-Stage Regression fits. Though we have found similar results (not shown) when we have considered other one-dimensional paths through the truth, it is possible that other approaches, to making the fitted model differ from the correct model, may lead to different results. More work, including theoretical work as well as simulation studies, that compares and sheds more light on various bias-variance properties of the two proposed estimators is necessary. In particular, more work is needed in this area to understand the extent to which parametric estimators in noisy settings may dominate semi-parametric estimators of the SNMM, including the different possible generative models (i.e., scenarios) under which this may or may not be true.

While the 2-Stage Estimator can serve a stand-alone estimator for the intermediate causal effects, it is also quite useful as a method to obtain high quality starting values for Robins’ G-Estimator. Recall that the semi-parametric efficiency of Robins’ G-Estimator requires correct models for the bt functions. The 2-Stage Estimator provides a principled method, from the standpoint of attempting to model the nuisance functions and respecting its constraints, for obtaining starting values for bt. In moderate to large sample sizes, the simulation experiments show a marked improvement in the performance of Robins’ G-Estimator (in terms of MSE) when the 2-Stage Estimator is used to obtain the β̂t compared to having no model for the bt’s. Experiment B demonstrates how this improvement persists (though diminishes, slightly) in moderate sample sizes even as the amount of mis-specification of the nuisance functions in the guesses for bt increases.

The methodology was illustrated in Section 5 with observational data from the PROSPECT study. An important concern that comes to mind when interpreting the results of this illustrative analysis, is that the assumption of sequential ignorability may be violated in our particular analysis. The illustrative analysis assumes only that suicidality both (a) affects depression outcomes, and (b) determines whether or not a patient receives treatment at the next time point. Yet it may be possible that subjects that were worse off, in terms of having higher depression scores and more emotional and physical problems, are more likely to receive treatment at subsequent visits to the clinic. If this is true, then the estimates of β (under both estimators) are likely biased due to baseline and/or time-varying confounders. A more in-depth (and proper) analysis of this data will seek to understand what are the possible confounders (baseline and/or time-varying) of the effect of treatment, by discovering what are the predictors of time-varying treatment Ā3. It would be possible to adjust for these additional time-varying confounders using the estimation methods proposed here in combination with inverse-probability-of-treatment weights (Robins (1999)), for example, but this is beyond the scope and purpose of this article. This is a promising future research direction that is currently being explored, as it begins to pull together the ideas of estimation used in Marginal Structural Models (Robins (1999)) with the ideas of estimation used in SNMMs (e.g., the methodology presented in this article).

Another natural extension of the SNMM methodology described in this article is to extend it to accommodate a time-varying longitudinal outcome Yt (one that is recorded at each visit, for example). This model would require a separate SNMM specification for Yt given (S̄t, Āt) for every t (i.e., a SNMM at each time point). A generalization of this sort along a GEE framework should be relatively straightforward; and in this case, both the 2-Stage Estimator and Robins’ G-Estimator presented here can be used with little modification. The development of a Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) is needed, however, before moving towards a growth-model or mixed-models framework. The 2-Stage Estimator can be seen as paving the way for a MLE for the SNMM. Indeed, the 2-Stage Estimator already requires models for the conditional mean of Y given (S̄K, ĀK), and for portions of the conditional distribution of St given (S̄t−1, Āt−1) for all t. To develop the MLE, an additional step would involve positing distributional assumptions (e.g., normality) for the Y given (S̄K, ĀK) and St given (S̄t−1, Āt−1) distributions. Note that as moments-based estimators, neither the 2-Stage Estimator nor Robins’ G-Estimator require distributional assumptions on the full likelihood for (S̄K, ĀK, Y).

Supplementary Material

Web Appendices referenced throughout this article are available under the Paper Information link at the Biometrics website http://www.tibs.org/biometrics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank ‥‥**insert later**…‥ Funding was provided by NIMH grants R01-MH-61892-01A2 (TenHave), R01-MH-080015-01 (Murphy), and a NIDA grant P50-DA-010075-02 (Murphy).

Footnotes

The sinusoidal functions were placed in the generative model to add some complexity to the nuisance function terms in the generative model.

REFERENCES

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel P, Klaassen C, Ritov Y, Wellner J. Efficient and Adaptive Estimation for Semiparametric Models. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M, Pearson J. Designing an intercention to prevent suicide: Prospect (prevention of suicide in primary care elderly: Collaborative trial) Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 1999;1:100–112. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.1999.1.2/mbruce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CFI, Katz IR, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Lapp K, Goetghebeur E. Practical properties of some structural mean analyses of the effect of compliance in randomized trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1999;20:531–546. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetghebeur E, Fischer-Lapp K. The effect of treatment compliance in a placebo-controlled trial: Regression with unpaired data. Applied Statistics. 1997;46:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1986;81:945–970. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe M, Small D, Hsu C. Defining and estimating intervention effects for groups who will develop an auxiliary outcome. Statistical Science. 2007;22:74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson G, Fairburn C. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder J. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd edition. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Newey W. Semiparametric efficiency bounds. Journal of Applied Econometrics. 1990;5:99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen ML, van der Laan MJ. History-adjusted marginal structural models: Time-varying effect modification. Technical Report 173. U.C. Berkeley Division of Biostatistics; 2005. http://www.bepress.com/ucbbiostat/paper173. [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. A graphical approach to the identification and estimation of causal parameters in mortality studies with sustained exposure periods. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1987;40:139s–161s. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9681(87)80018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. The analysis of randomized and non-randomized aids treatment trials using a new approach to causal inference in longitudinal studies. NCHSR, US Public Health Service; Health Service Research Methodology: A Focus on AIDS. 1989a:113–159.

- Robins J. The control of confounding by intermediate variables. Statistics in Medicine. 1989b;8:679–701. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. Correcting for non-compliance in randomized trials using structural nested mean models. Communications in Statistics, Theory and Methods. 1994;23:2379–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Robins J. Estimating causal effects of time-varying endogenous treatments by g-estimation of structural nested models. In: Berkane M, editor. Latent Variable Modeling and Applications to Causality, Lecture Notes in Statistics. New York: Springer; 1997. pp. 69–117. [Google Scholar]

- Robins J, Rotnitzky A. Estimation of treatment effects in randomised trials with non-compliance and a dichotomous outcome using structural mean models. Biometrika. 2005;91 763783. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM. Association, causation, and marginal structural models. Synthese. 1999;121:151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Mark S, Newey W. Estimating exposure effects by modelling the expectation of exposure conditional on confounders. Biometrics. 1992;48:479–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1974;66:688–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Have T, Joffe M, Lynch K, Maisto S, Brown G, Beck A. Causal mediation analyses with rank preserving models. Biometrics. 2007;63 doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00766.x. 926934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteeldandt S, Goetghebeur E. Causal inference with generalized structural mean models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2003;65:817–835. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web Appendices referenced throughout this article are available under the Paper Information link at the Biometrics website http://www.tibs.org/biometrics.