Abstract

Calcium phosphate cement (CPC) is osteoconductive and moldable, can conform to complex cavity shapes and set in-situ to form hydroxyapatite. Chitosan could increase the strength and toughness of CPC, but there has been no investigation on recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) delivery via CPC-chitosan composite and its effect on osteogenic induction of cells. The objective of this research was to investigate the mechanical properties and osteoblastic induction of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CPC containing chitosan and rhBMP-2. Cell viability for CPC with chitosan and BMP was comparable to that of control CPC, while the CPC-chitosan composite was stronger and tougher than CPC control. After 14 d, osteblastic induction was quantified by measuring alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. ALP (mean±sd;n=6) of cells seeded on traditional CPC without rhBMP-2 was (143±19) (mM pNpp/min)/(μg DNA). Adding chitosan resulted in an ALP of (161±27). Further addition of rhBMP-2 to the CPC-chitosan composite increased the ALP to (305±111) (p<0.05). All ALP activity on CPC composites was significantly higher when compared to the (10.0±3.3) of tissue culture polystyrene (p<0.05). Flexural strength of CPC containing 15% (mass fraction) chitosan was (19.8±1.4)MPa which more than doubled the (8.0±1.4) MPa of conventional CPC (p < 0.05). The addition of chitosan to CPC increased the fracture toughness from (0.18±0.01)MPa·m1/2 to (0.23±0.02)MPa·m1/2 (p<0.05). The relatively high strength, self-hardening CPC-chitosan composite scaffold is promising as a moderate load-bearing matrix for bone repair, with potential to serve as an injectable delivery vehicle for osteoinductive growth factors to promote osteoblastic induction and bone regeneration.

Keywords: calcium phosphate cement, CPC, chitosan, bone morphogenic proteins, BMP-2, tissue engineering, bone regeneration

1. INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that bone tissue is the second most transplanted tissue, second only to blood, with more than one million procedures performed annually to repair bone defects cause by trauma, disease or other congenital defects.1 Autologous and allogenic grafts currently comprise 90% of grafts performed each year, with synthetic grafts comprising 10% of grafts.1 Drawbacks for bone grafting include donor site morbidity (autografts) and risk of disease transmission (allografts) along with the potential loss of graft potency because of sterilization techniques.2 The effectiveness of autografts and allografts has been a concern as well, with a reported failure rate of 13 % to 30 % in autografts and 20 % to 40 % in allografts.3, 4 Additionally, bone regeneration may become more difficult due to factors such as age, disease or trauma. A successful synthetic bone grafting system is comprised of three factors: the extracellular matrix (natural or synthetic), diffusible growth factors/proteins, and viable cells.5 The scaffold material provides mechanical support and stability and a substrate for cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation. Viable cells participate in the proliferation, differentiation or induction and ultimate mineralization of bone tissue. Cells also provide a local source for soluble growth factors found in the ECM. Additionally, diffusible growth factors and other proteins can be added exogenously and also mediate the cellular response in bone regeneration.

It is important to develop a biocompatible, osteoinductive biomaterial with physical properties similar to cancellous bone that can improve the development of local bone formation. To be effective, the biomaterial should include a matrix that provides mechanical stability and supports cell growth. In addition, it is desirable to include biochemical factors that support cell migration, proliferation and differentiation and or induction and viable cells themselves.

Hydroxyapatite is an important biomaterial that has been used as a matrix for hard tissue repair because of its similarity to carbonated apatite in teeth and bones.6-8 There are several calcium phosphate cements that self-harden to form hydroxyapatite.9-14 One calcium phosphate cement referred to as CPC is a mixture of tetracalcium phosphate and dicalcium phosphate anhydrous. When mixed with water or another aqueous solution, a workable paste is formed that can be shaped to fill a defect. Once hardened, a microcrystalline hydroxyapatite exists, which is biocompatible and can be gradually replaced with new bone.15, 16 While the biocompatibility, osteoconductivity and moldability make CPC an excellent candidate for minimally invasive orthopedic surgical applications, its poor strength properties have limited its use to primarily low stress-bearing applications, where it has been approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).17 The introduction of a fibers made from a degradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) copolymer has been shown to provide excellent reinforcement and strength at the early stages of implantation.18 Degradation of the fiber over time can coincide with the ingrowth of natural bone and a gradual transfer of the load bearing from the synthetic biomaterial to the natural bone. Additionally, the degradation of the fiber creates macroporous channels inside the composite, which is essential to facilitate cell infiltration and tissue ingrowth.

Another method of improving the toughness of CPC is by the addition a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer, chitosan lactate, which can increase the strength by a factor of 2 and work of fracture by an order of magnitude.19 It has been shown in recent publications that the addition of chitosan lactate and a reinforcing fiber mesh has a synergistic effect in enhancing the physical properties of CPC for bone tissue engineering applications.20

Several studies have incorporated growth factors into CPC.21-34 For example, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in a cement was found to stimulate bone cell differentiation and osteoconductivity.21, 22 Another study developed a poly(dl-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-calcium phosphate composite, and demonstrated the feasibility of delivering recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2).31, 32 However, the strength of the protein-releasing CPC was significantly decreased compared to that without protein.31 Another study found that about half of the protein was released from CPC in 140 h.35 The diametral tensile strength of the protein-containing CPC was relatively low, ranging from 3.5 to 6.4 MPa.35 A recent study investigated the utilization of growth factor-loaded gelatin microspheres combined with a calcium phosphate cement.24 The in vitro release pattern was modified, however cell studies were not undertaken. Further enhancement of bone formation can occur by increasing the porosity of the material. In one study, cell infiltration and cement resorption was facilitated by the introduction of sodium bicarbonate to disperse the cement into smaller granules.26 Another study created a porous calcium phosphate cement by carbon dioxide induction in order to increase cell infiltration and migration.32 Additionally, an injectable calcium phosphate cement has been show to be an effective carrier for antibiotics, exhibiting no reduction in antibiotic activity related to the cement setting reaction.27 However, there was no effort made to improve the strength of protein-releasing CPC for stress-bearing applications in these studies. Recently36 it was shown that reinforced CPC composites containing chitosan lactate may be an effective carrier and delivery vehicle for proteins. However, no study has been performed on delivering rhBMP-2 using the mechanically-strong CPC-chitosan composite, and no investigation has been done on osteoblastic induction on injectable CPC-chitosan composites containing rhBMP-2.

The objectives of the present study, therefore, were to: (1) Develop an in situ setting, reinforced CPC with improved strength and toughness and incorporation of rhBMP-2 to facilitate osteoblastic induction; and (2) quantify the effect of BMP-2 addition by measuring cell viability, proliferation and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cement powder and liquid

The CPC powder consisted of a mixture of tetracalcium phosphate (TTCP: Ca4[PO4]2O) and dicalcium phosphate anhydrous (DCPA: CaHPO4) at a TTCP:DCPA molar ratio of 1:1. As described previously9 the TTCP powder was synthesized from a solid-state reaction between CaHPO4 and calcium carbonate, then ground and sieved to obtain TTCP particles with a median size of 17 μm. The DCPA powder was ground to obtain particles with a median diameter of 1 μm. The TTCP and DCPA powders were then mixed to form the CPC powder.

Chitosan and its derivatives are natural biopolymers found in arthropod exoskeletons; they are biocompatible, biodegradable, and hydrophilic.37 The purpose of incorporating chitosan into CPC in the present study was to strengthen the CPC. The CPC liquid used in this study consisted of chitosan lactate (Technical grade, VANSON, Redmond, WA; referred to as chitosan) mixed with sterile distilled water at a pH of 7.2. Four cement liquids were made at chitosan/(chitosan + water) mass fractions of 0, 5, 10, and 15%.

2.2. Recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 (rhBMP-2)

Recombinant human BMP-2 (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ), expressed in E. coli was reconstituted in sterile deionized water containing bovine serum albumin (BSA; 50 mg BSA per 1 mg rhBMP-2) to create a stock solution of 100 mg/mL, which was kept frozen at −80 °C until needed.

2.3. Sterilization

CPC powder, chitosan lactate powder and specimen molds were sterilized in an ethylene oxide sterilizer (Anprolene AN 74i, Andersen, Haw River, NC) for 12 h according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The materials were then degassed for at least 7 d to remove any remaining ethylene oxide gas before beginning the cell experiment.

2.4. Specimen fabrication for cell culture

A sterile Teflon ring (11.5 mm diameter; 1.5 mm high) was placed in each well of a 24 well cell culture plate. CPC paste was formed by mixing sterile CPC powder with sterile chitosan lactate solution at a CPC powder to liquid ratio of 3 to 1. A chitosan mass fraction of 15% was used because mechanical testing showed that this composite had the highest strength. Three sets of specimens (n = 6 for each set) were fabricated: CPC + 0 % chitosan, CPC + 15 % chitosan and CPC + 15 % chitosan + 5 μg rhBMP-2. The rhBMP-2 was added directly to the chitosan solution to give a final concentration of 5 μg in each specimen. This concentration has been shown to effectively enhance osteogenesis in other studies.38, 39 The powder and liquid portions were mixed under sterile conditions by hand spatulation and the Teflon molds were filled with the resulting paste. The filled molds were placed in an incubator at 37 °C and 100% relative humidity for 72 h to facilitate the setting reaction.

2.5. Cell culture

Clonal murine calavarial cells, MC3T3-E1 subclone 4, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas,VA) and maintained using established cell culture protocols. Cells were cultured in flasks (150 cm2 surface area) at 37 °C in a fully humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2 (volume fraction) in alpha-modified Eagle’s minimum essential medium (α-MEM; Lonza Biosciences, Walkersville, MD). The medium was supplemented with 10 % (volume fraction) fetal bovine serum, FBS, 1 % (volume fraction), penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. This will subsequently identified as “control medium”. All medium supplements were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA) and used without further purification. At 90 % confluence, cells were harvested by rinsing with 0.25 % trypsin, 0.03 % EDTA solution (both volume fraction) and incubated at room temperature until the cells detached. A cell pellet was formed by centrifugation at 600 x g for 5 minutes; cells were resuspended in fresh medium and counted with a hemocytometer. Fifty thousand cells diluted into 2 ml of control media supplemented with 0.05 mM ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, referred to as “osteogenic medium” were added to each well containing a CPC specimen. Cell culture media was changed every 3 days for the duration of the experiment.

2.6. Cell viability

Specimen preparation and cell culture conditions were described previously. Separate specimens were fabricated for 1 d and 14 d experiments, respectively. A “Live/Dead” cell viability assay was performed at 1 d and 14 d to determine the viability of cells on CPC, CPC+rhBMP-2, CPC+15% chitosan and CPC+15% chitosan+rhBMP-2 composites. The principle of the live/dead assay is that membrane-permeant calcein AM is cleaved by esterases in live cells to yield cytoplasmic green fluorescence, and membrane-impermeant ethidium homodimer-1 labels nucleic acids of membrane-compromised cells with red fluorescence. Thus, live cells display green fluorescence and compromised cells display red fluorescence. Cell culture media was removed from the CPC composites, which were then washed 2 times with sterile Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.2). After washing, 2.0 mL of medium without serum containing 0.002 mmol/L calcein-AM and 0.002 mmol/L ethidium homodimer-1 (both from Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to each specimen. The cells were incubated for 10 min, observed by epifluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE-2000S, Melville NY) and photographed.

2.6.1. Cell viability, attachment, and proliferation

The percent of live cells (cell viability) was defined as PLive = NLive/(NLive + NDead), where NLive = # of live cells, and NDead = # of dead cells, in the same image. Six specimens of each material were tested (n = 6). Two randomly chosen fields of view are photographed from each specimen after live/dead staining for a total of 12 photos per material, and the cells are counted.

Live cell density, CAttach, was defined as the number of live cells attached on the CPC specimen divided by the specimen area A, in the view field: CAttach = NLive/A. Cell proliferation on CPC was examined by comparing 1-day culture with 14-day cultures.

2.7. Alkaline phosphatase activity

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is an enzyme expressed by cells during osteogenesis. While not a conclusive test for phenotypic expression, ALP activity has been shown to be a well-defined marker for their differentiation.40 A colorimetric p-nitrophenyl phosphate assay (Stanbio, Boerne TX) was used to measure ALP expression and quantify the osteogenesis of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on the CPC composites. At 14 d, cells were assayed for ALP expression. Cells were lysed in 0.5 mL of buffer (0.2% v/v Triton x-100, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4)) and lysates were assayed for ALP activity according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Normal Control Serum (Stanbio), which contains a known concentration of ALP was used as a standard. Alkaline phosphatase activity was normalized to DNA concentration for each sample using the PicoGreen assay (Invitrogen).

2.8. Mechanical testing

CPC specimens were tested at 4 chitosan mass fractions in the liquid: 0 %, 5 %, 10 % and 15 %, while maintaining a powder to liquid ratio of 3 to 1. The mixed CPC-chitosan paste was placed into molds of 3 mm × 4 mm × 25 mm. Each specimen was set in a chamber with 100 % relative humidity at 37 °C for 4 h, and then demolded and immersed in distilled water at 37 °C for 24 h prior to testing. A standard three-point flexural test (ASTM F417-78) with a span of 20 mm was used to fracture the specimens at a crosshead speed of 1 mm per minute on a computer-controlled Universal Testing Machine (model 5500R, MTS, Cary, NC). Flexural strength was calculated by S = 3 Fmax L / (2 b h2), where Fmax is the maximum load on the load-displacement curve, L is flexure span, b is specimen width, and h is specimen thickness.41 Elastic modulus was calculated by E = (F / c) (L3 / [4 b h3]), where load F divided by the corresponding displacement c is the slope of the load-displacement curve in the linear elastic region. Fracture toughness was measured by the use of a single-edge- notched beam method.42

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed to detect significant effects in the data. Tukey’s multiple comparison procedures were used to compare the data at a family confidence coefficient of 0.95.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Mechanical Properties

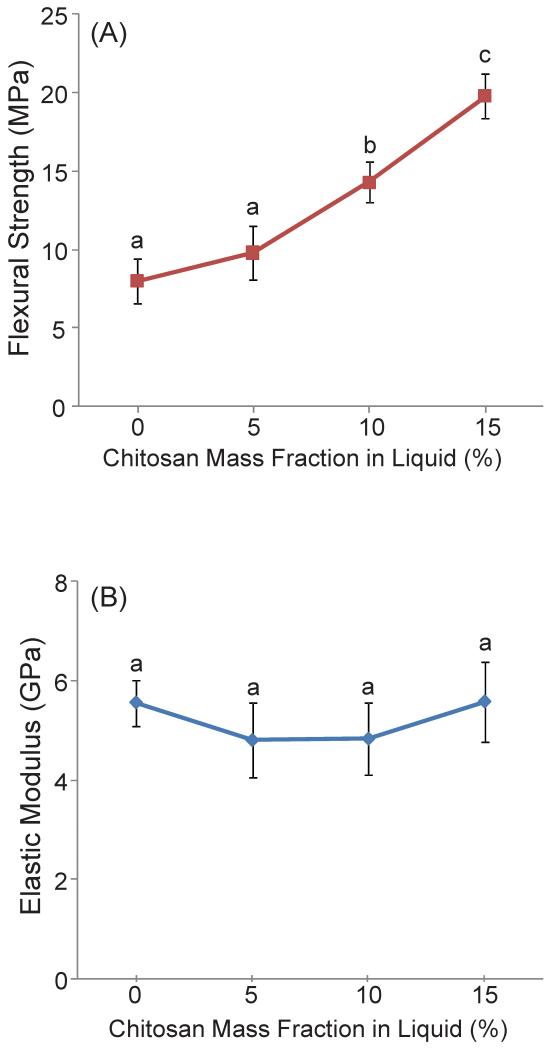

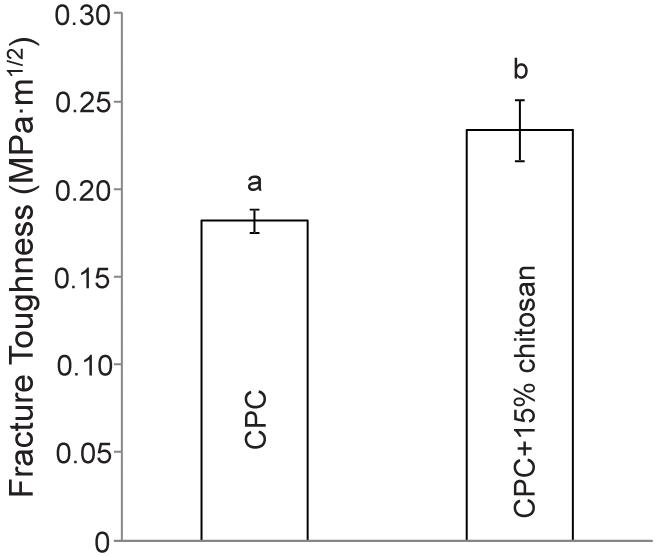

Figure 1 plots the (A) flexural strength and (B) elastic modulus of chitosan-containing CPC composites. Increasing the chitosan mass fraction from 0 to 15% significantly increased the strength of the CPC-chitosan composite. Specifically, the flexural strength was increased more than 2-fold from 8 MPa at 0% chitosan, to 19.8 MPa at 15% chitosan (p < 0.05), while the addition of 5% chitosan and 10% chitosan showed more moderate improvements to 9.8 MPa and 14.3 MPa respectively. However, elastic modulus was not significantly increased (p > 0.1) when increasing the chitosan content from 0% to 15%. The elastic modulus was 5.6 GPa at 0% chitosan and remained unchanged at 15% chitosan. The addition of 15% chitosan to CPC significantly increased the fracture toughness from (0.18 ± 0.01) MPa·m1/2 to (0.23 ± 0.02) MPa·m1/2, as plotted in Figure 2 (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

(A) Flexural strength and (B) Elastic modulus of CPC as a function of mass fraction of chitosan in liquid. Each value is the mean of six measurements with the error bar showing one standard deviation (mean ± sd; n = 6). Dissimilar letters in the plot indicate values that are significantly different (Tukey’s multiple comparison test; family confidence coefficient = 0.95).

Figure 2.

Fracture toughness of CPC + 0% chitosan and CPC + 15% chitosan. Each value is the mean of six measurements with the error bar showing one standard deviation (mean ± sd; n = 6). Dissimilar letters in the plot indicate values that are significantly different (Tukey’s multiple comparison test; family confidence coefficient = 0.95).

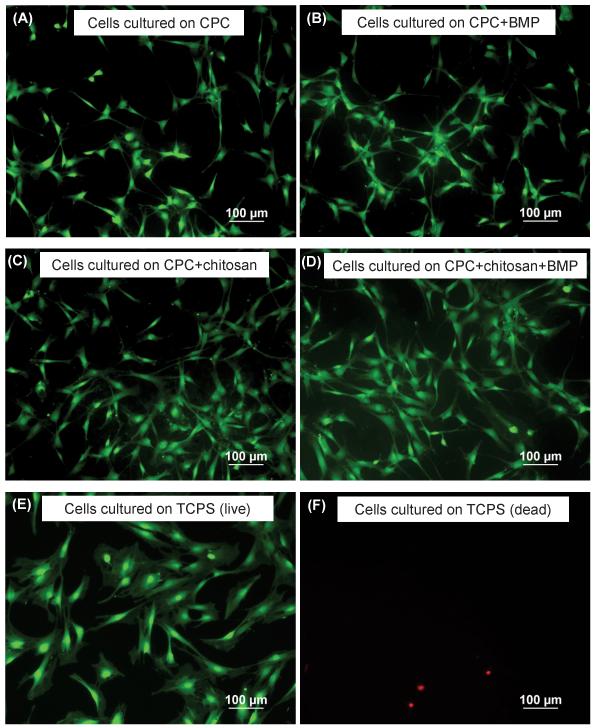

3.2 Cell viability

Figure 3 shows MC3T3-E1 cells cultured for 1 d on CPC control, CPC+rhBMP-2, CPC+15% chitosan, CPC+15% chitosan+rhBMP-2 composite, as well as tissue culture polystyrene. Live cell were stained green and appeared to be numerous, while compromised cells were stained red and were much fewer in number. Additionally, live cells were adherent and attained a normal polygonal morphology on the specimens, regardless of the type of CPC composite the cells were cultured on. Cell attachment at 1 d was similar for all materials when compared with TCPS. However, there was a greater degree of cell spreading at 1 d on TCPS compared with all other materials. Several factors, including surface roughness, localized pH changes, and ion activity related to the CPC setting reaction, may contribute to less cell spreading on the CPC materials. At 14 d (Figure 5), cell spreading and morphology is similar across all materials, including TCPS. These characteristics were similar to previously reported data.43, 44

Figure 3.

Cells cultured for 1 d on: (A) live cells on CPC+0% chitosan, (B) live cells on CPC+0% chitosan + 5 μg rh-BMP-2, (C) live cells on CPC+15% chitosan (D) live cells on CPC+15% chitosan + 5 μg rh-BMP-2 (E) live cells on TCPS control (F) dead cells on TCPS control.

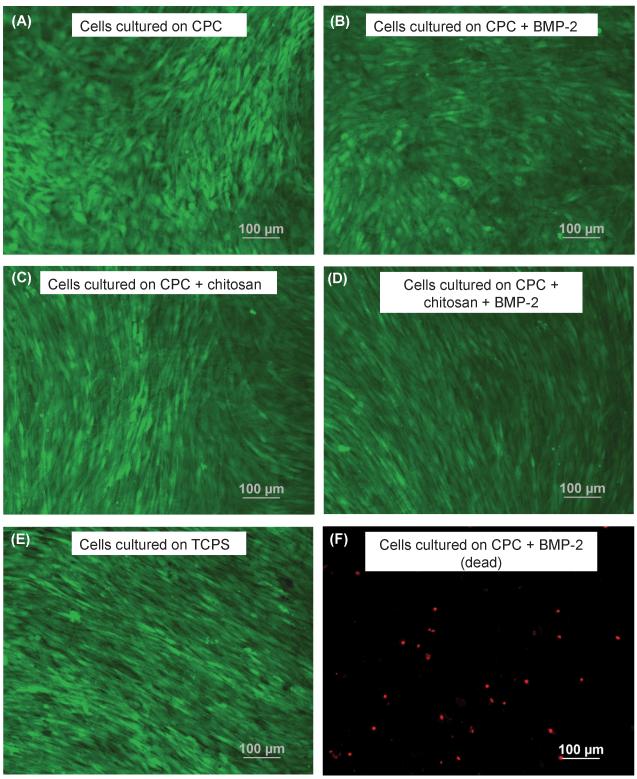

Figure 5.

Cells cultured for 14 d. Live cells are stained green in panels (A) to (E). Dead cells are stained red in panel (F). (A) CPC with 0% chitosan, (B) CPC specimens with 0% chitosan + rhBMP-2, (C) CPC specimens with 15% chitosan, (D) CPC specimens with 15% chitosan + rhBMP-2, (E) TCPS without rhBMP-2 and (F) dead cells on CPC specimens with 0% chitosan + rhBMP-2.

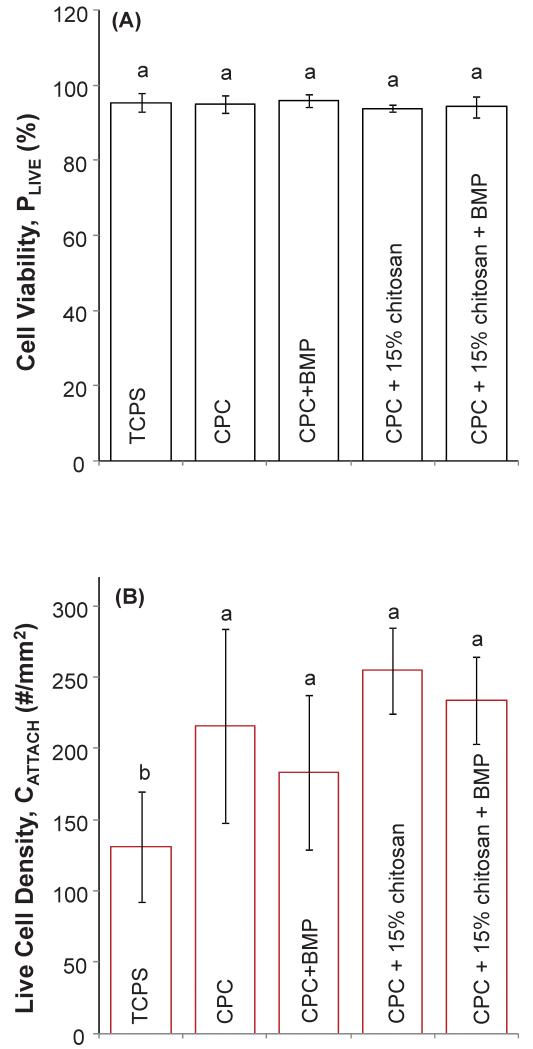

The cell response depicted in Figure 3 is quantified in Figure 4. Figure 4(A) illustrates the cell viability of MC3T3 cells when cultured on TCPS, CPC, CPC+rhBMP-2, CPC+15% chitosan and CPC+15% chitosan+rhBMP-2 composites. The percentage of live cells on all samples was greater than 94% and not significantly different from each other (p > 0.1). Additional quantification of the cell attachment behavior is plotted in Figure 4(B), where the number of live cells was measured per specimen surface area (# cells/mm2). Cells cultured on TCPS control showed significantly fewer live cells per surface area (131.11 cells/ mm2) when compared with all CPC composites (Tukey’s at 0.05) except for CPC+0% chitosan+BMP, where there was not a significant difference (p > 0.1). There were no significant differences in the number of live cells per specimen surface area for all CPC composites investigated, regardless of chitosan or rhBMP-2 content (p > 0.1).

Figure 4.

(A) Cell viability (or percentage of live cells) = number of live cells / (number of live cells + number of dead cells) at 1 d cell culture. (B) Live cell density (or cell attachment per specimen surface area) = number of live cells / mm2 (mean ± sd; n = 6) at 1 d cell culture. Dissimilar letters in the plot indicate values that are significantly different (Tukey’s multiple comparison test; family confidence coefficient = 0.95).

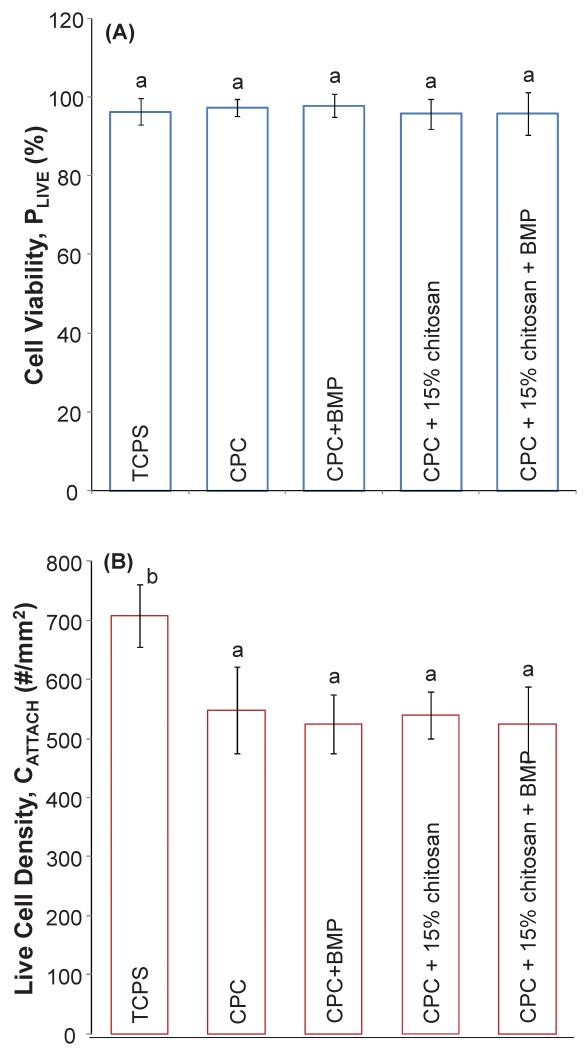

Figure 5 shows MC3T3-E1 cells cultured for 14 d on CPC, CPC+rhBMP-2 and CPC+15% chitosan composites and indicates substantial cell proliferation. As in Figure 3, live cells are stained green and compromised cells are stained red. Live MC3T3-E1 cells form a confluent monolayer on all CPC surfaces at 14 d, with relatively few dead cells, regardless of the live cell attachment seen on day 1. The cells formed a predominantly confluent monolayer after 14 days and individual cells were difficult to distinguish in some areas. Cell counting was performed on areas where individual cells could be distinguished. As such, 14 day proliferation values represent an “undercount” of the actual cell density. Figure 6(A) illustrates the cell viability of MC3T3 cells when cultured on TCPS, CPC, CPC+rhBMP-2, CPC+15% chitosan and CPC+15% chitosan+rhBMP-2 composites. The percentage of live cells on all samples was greater than 96% and not significantly different from each other (p > 0.1). Likewise, there was not a significant difference in the number of live cells per specimen surface area between all the CPC-based samples. However, the number of live cells per specimen surface area on TCPS was (708 ± 53) cells/mm2, significantly different from the cells cultured on all CPC specimens (Tukey’s at 0.05).

Figure 6.

(A) Cell viability (or percentage of live cells) = number of live cells / (number of live cells + number of dead cells) at 14 d cell culture. (B) Live cell density (or cell attachment per specimen surface area) = number of live cells / mm2 (mean ± sd; n = 6) at 14 d cell culture. Dissimilar letters in the plot indicate values that are significantly different (Tukey’s multiple comparison test; family confidence coefficient = 0.95).

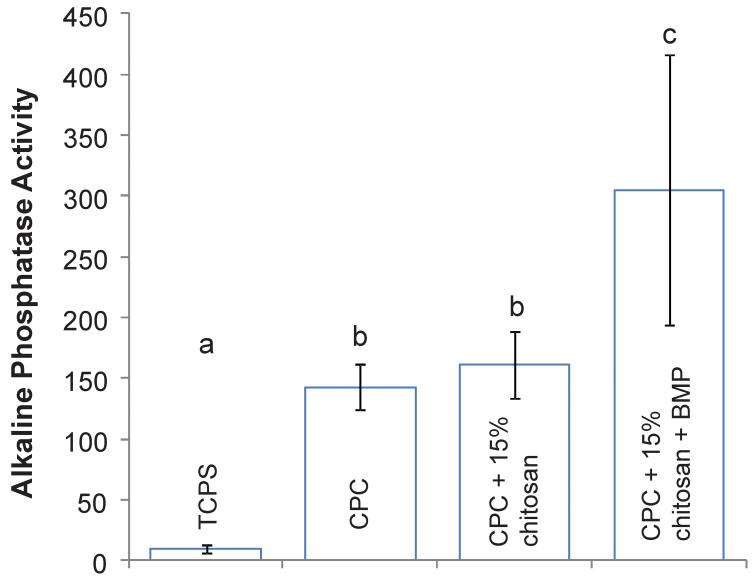

3.3. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity

The alkaline phosphatase activity for the CPC composites at 14 days is shown in Figure 7, normalized to the amount of DNA per sample. The addition of rhBMP-2 to the CPC containing 15% chitosan resulted in a significant and almost twofold increase in the ALP activity from 161.30 (mM pNpp/min)/(μg DNA) to 304.96 (mM pNpp/min)/(μg DNA) (Tukey’s at 0.05). The ALP activity of CPC containing no chitosan and no rhBMP-2 was 142.90, which was similar to that of CPC+15% chitosan (p > 0.1) and indicated that the addition of chitosan to CPC composites had no effect on the alkaline phosphatase activity. Meanwhile, all of the CPC composites exhibited a significantly enhanced alkaline phosphatase activity when compared with tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) which had an ALP activity of 10.0 (mM pNpp/min)/(μg DNA) (Tukey’s at 0.05).

Figure 7.

Relative alkaline phosphatase activity of MC3T3-E1 cells at 14 d cultured on TCPS, CPC, CPC+15% chitosan and CPC+15% chitosan+5 μg rhBMP-2. ALP activity is normalized with respect to the DNA concentration in each sample to give units of [(mM pNpp/min)/(μg DNA)]. Dissimilar letters in the plot indicate values that are significantly different (Tukey’s multiple comparison test; family confidence coefficient = 0.95). Each value is the mean of six measurements with the error bar showing one standard deviation (mean ± sd; n = 6).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, a CPC-chitosan composite was investigated as a moldable/injectable carrier for rhBMP-2 with a relatively high strength and fracture toughness, for the first time. Cell viability at 1 d and 14 d was similar for all CPC-based materials and compared well with tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS). Live cell density for all CPC-based materials was also similar at 1 d and 14 d. However, the live cell density for cells cultured on TCPS was significantly lower at 1 d and higher at 14 d when compared with the CPC-based materials, even though the same cell seeding density was used for all materials. It is possible that CPC ion activity had a slight effect on cell proliferation, leading to the higher cell density on TCPS at 14 d. However, CPC-chitosan and CPC containing rhBMP-2 did not adversely affect cell proliferation compared to traditional CPC, which was approved by the FDA for craniofacial repairs. The incorporation of rhBMP-2 into the CPC-chitosan composite significantly enhanced the osteoblastic induction of cells in vitro, with a much higher ALP activity compared to CPC control and TCPS. While ALP activity is not a conclusive test for phenotypic expression, the significant increase in ALP in composites containing rhBMP-2 compared to composites without rhBMP-2 indicates a positive effect of rhBMP-2. The incorporation of growth factors and proteins into biomaterials for bone tissue engineering is highly beneficial. Bone regeneration may become difficult because of factors such as advanced age, disease, and large, irregularly-shaped defects. These factors necessitate the introduction of therapeutic means to facilitate new bone formation.45 Hence, it is desirable for a bone grafting system to be comprised of a stress bearing extracellular matrix (natural or synthetic) containing diffusible growth factors/proteins which promote proliferation and differentiation to form new bone.46 For example, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) has been shown to stimulate the production of cartilage-specific proteoglycans by mesenchymal stem cells and induce the proliferation of osteoblasts and osteoblast-mediated collagen deposition.47 Additionally, acidic and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) have been shown to increase proliferation of numerous cell populations in vivo.48 Bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), which belong to the TGF-β superfamily, have been investigated extensively for their osteoinductive potential. 49, 50

There is a wide range of natural and synthetic bone graft substitutes based on natural and synthetic polymers51, 52, ceramics53-56 and composites57, which have been developed over time to address the shortcomings of autologous grafting systems.58 From a materials development standpoint, the mechanical properties of bone replacement materials should be similar to that of naturally-occurring bone. For example, the bulk modulus of cancellous bone ranges from 50 to 100 MPa 59 and the longitudinal fracture toughness (MPa·m1/2) of cortical bone has been measured to be between 1.5 and 2.5.60 The flexural strength of the CPC-chitosan composites containing 15% chitosan investigated in this study was 19.8 MPa and exceeds the flexural strength of sintered porous hydroxyapatite, which has a flexural strength of 2 MPa to 11 MPa 61 and cancellous bone, which has a tensile strength of 3.5 MPa. Additionally, the advantage of the new chitosan-containing nano-apatite scaffold is that it is moldable and can set in-situ, resulting in intimate adaptation to complex bone cavities without machining. Furthermore, CPC is resorbable, while sintered HA is relatively stable in vivo.62 This resorption allows the CPC to be gradually replaced over time with new bone while maintaining mechanical and dimensional stability. For another comparison, a composite scaffold based on collagen co-electrospun with nano HA exhibited a tensile strength of 1.68 MPa.63 Even accounting for the fact that flexural strength is usually 1-3 times higher than tensile strength, the CPC-chitosan composite had significantly higher mechanical properties.

In our current study, recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) was introduced to the CPC liquid (15 % chitosan solution by mass) at a concentration of 5 μg per specimen, which was then mixed with CPC powder to form a CPC paste. Two bone graft replacements that incorporate BMPs and are currently available for clinical applications are InFUSE (rhMBP-2, Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis TN) and OP-1 Putty (rhBMP-7, Stryker Biotech, Hopkinton, MA). InFUSE introduces BMP by soaking a collagen sponge in a solution of rhBMP-2, which is then implanted into the surgical area, while in OP-1 Putty, the rhBMP-7 is mixed with a collagen carrier and carboxymethylcellulose to improve handling. Clinical evidence has supported the use of these materials for tibial fractures, non-unions and spinal fusions64, 65; however the physical properties of these materials make them undesirable for stress-bearing applications.

Accordingly, biomaterial systems have been developed to provide both enhanced mechanical properties as well as enhanced cellular response via osteoinductive factors such as BMPs. Prefabricated synthetic matrices such as porous poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds39, calcium phosphate-coated titanium alloys38, macroporous calcium phosphate cements66 and sintered hydroxyapatite scaffolds67 are generally soaked in a BMP solution prior to implantation. The in vitro and in vivo response to these materials has been favorable, as measured by ALP activity, mineralization and new bone formation. However, a major disadvantage of these materials is that they are prefabricated and exist in a hardened form that requires the surgeon to fit the surgical site around the implant or to carve the graft to the desired shape.2 As can be seen in Figure 7, the introduction of rhBMP-2 into the reinforced CPC composites elicits a 2-fold increase in the alkaline phosphatase activity after 14 days which indicates that the rhBMP-2 has maintained its bioactivity and promoted the osteoblastic induction of the MC3T3 cells when compared with normal control CPC and reinforced CPC in the absence of rhBMP-2. In addition, because rhBMP-2 was mixed with the CPC paste directly, the ability to tailor the release of rhBMP-2 from the CPC over a longer period of time is possible. This has been previously demonstrated with these reinforced CPC materials using a model protein.36 In that study, it was shown that alteration of the CPC powder to liquid ratio and the mass fraction of chitosan in the CPC liquid modified the porosity of the CPC composite and, subsequently, altered the protein release profile. Additionally, our laboratory previously created macroporous calcium phosphate cement constructs through the addition of soluble mannitol particles.68-70 In these studies, it was shown that preosteoblast cells were able to infiltrate into surface macropores of CPC, attach to hydroxyapatite crystals and establish cell-cell interactions. The present study focused on the effect of BMP on osteoblastic induction on a strong CPC-chitosan composite without macropores. Future studies will develop macroporous CPC carrier for growth factor delivery. The introduction of macroporosity and rhBMP-2, along with the moldability, ability to conform to complex shapes, and in situ hardening would make the reinforced CPC potentially useful as a moderately stress-bearing, osteoconductive and osteoinductive scaffold.

5. CONCLUSION

In-situ hardening CPC-chitosan-BMP constructs were developed for bone tissue engineering. Chitosan increased the CPC’s flexural strength by 2-fold to match or exceed the reported strengths of sintered porous hydroxyapatite implants and cancellous bone. Osteoblast cells attached to CPC, CPC with chitosan and with BMP, and showed a healthy spreading morphology. Cell viability for CPC with chitosan and with BMP was comparable to that of the control CPC that was approved by the FDA, while the CPC-chitosan composite was stronger and tougher than CPC control. Cell proliferation at 14 days on the mechanically-stronger constructs also matched that of the CPC control. Furthermore, the CPC-chitosan-BMP construct yielded a significantly higher ALP, an important bone marker, in vitro, than CPC control and CPC with chitosan. Therefore, (1) the incorporation of chitosan increased scaffold strength and toughness, without adversely affecting osteoblast cell attachment and viability; (2) the incorporation of BMP significantly enhanced osteoblastic induction, but did not significantly alter the cell attachment, viability and proliferation. In conclusion, the relatively high strength, self-hardening CPC-chitosan composite scaffold is promising to be a moderate load-bearing matrix for bone repair, with the potential to serve as an injectable delivery vehicle for osteoinductive growth factors to promote bone regeneration.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Larry Chow and Dr. Shozo Takagi of the American Dental Association Foundation’s Paffenbarger Research Center, and Dr. Carl Simon of the Polymers Division of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, for many helps and fruitful discussions. This study was supported by NIH R01 grants DE14190 and DE17974 (Xu), Maryland Nano-Biotechnology Initiative Award (Xu), Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (Xu), and the University of Maryland Dental School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salgado AJ, Coutinho OP, Reis RL. Bone tissue engineering: state of the art and future trends. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4:743–765. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurencin CT, Ambrosio AM, Borden MD, Cooper JA., Jr. Tissue engineering: orthopedic applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:19–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.19. 19-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackay AM, Beck SC, Murphy JM, Barry FP, Chichester CO, Pittenger MF. Chondrogenic differentiation of cultured human mesenchymal stem cells from marrow. Tissue Eng. 1998;4:415–428. doi: 10.1089/ten.1998.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winn SR, Uludag H, Hollinger JO. Carrier systems for bone morphogenetic proteins. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999:S95–106. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddi AH. Symbiosis of biotechnology and biomaterials: applications in tissue engineering of bone and cartilage. J Cell Biochem. 1994;56:192–195. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hench LL. Bioceramics. J Am Ceram Soc. 1998;81:1705–1728. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hing KA, Best SM, Bonfield W. Characterization of porous hydroxyapatite. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1999;10:135–145. doi: 10.1023/a:1008929305897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu TM, Orton DG, Hollister SJ, Feinberg SE, Halloran JW. Mechanical and in vivo performance of hydroxyapatite implants with controlled architectures. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown WE, Chow LC. A new calcium phosphate water setting cement. In: Brown PW, editor. Cements research progress. American Ceramic Society; Westerville, OH: 1986. pp. 352–379. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow LC, Takagi S, Costantino PD, Friedman CD. Self-setting calcium phosphate cements. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc. 1991;179:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginebra MP, Fernandez E, De Maeyer EA, Verbeeck RM, Boltong MG, Ginebra J, Driessens FC, Planell JA. Setting reaction and hardening of an apatitic calcium phosphate cement. J Dent Res. 1997;76:905–912. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760041201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrosio AM, Sahota JS, Khan Y, Laurencin CT. A novel amorphous calcium phosphate polymer ceramic for bone repair: I. Synthesis and characterization. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58:295–301. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(2001)58:3<295::aid-jbm1020>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeGeros RZ. Biodegradation and bioresorption of calcium phosphate ceramics. Clin Mater. 1993;14:65–88. doi: 10.1016/0267-6605(93)90049-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barralet JE, Gaunt T, Wright AJ, Gibson IR, Knowles JC. Effect of porosity reduction by compaction on compressive strength and microstructure of calcium phosphate cement. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman CD, Costantino PD, Takagi S, Chow LC. BoneSource hydroxyapatite cement: a novel biomaterial for craniofacial skeletal tissue engineering and reconstruction. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;43:428–432. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199824)43:4<428::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohner M, Baroud G. Injectability of calcium phosphate pastes. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1553–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costantino PD, Friedman CD, Jones K, Chow LC, Sisson GA. Experimental hydroxyapatite cement cranioplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:174–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu HH, Quinn JB, Takagi S, Chow LC, Eichmiller FC. Strong and macroporous calcium phosphate cement: Effects of porosity and fiber reinforcement on mechanical properties. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57:457–466. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20011205)57:3<457::aid-jbm1189>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu HH, Quinn JB, Takagi S, Chow LC. Processing and properties of strong and non-rigid calcium phosphate cement. J Dent Res. 2002;81:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu HH, Quinn JB, Takagi S, Chow LC. Synergistic reinforcement of in situ hardening calcium phosphate composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blom EJ, Klein-Nulend J, Klein CP, Kurashina K, van Waas MA, Burger EH. Transforming growth factor-beta1 incorporated during setting in calcium phosphate cement stimulates bone cell differentiation in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:67–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<67::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blom EJ, Klein-Nulend J, Wolke JG, Kurashina K, van Waas MA, Burger EH. Transforming growth factor-beta1 incorporation in an alpha-tricalcium phosphate/dicalcium phosphate dihydrate/tetracalcium phosphate monoxide cement: release characteristics and physicochemical properties. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandoff JF, Silber JS, Vaccaro AR. Contemporary alternatives to synthetic bone grafts for spine surgery. Am J Orthop. 2008;37:410–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habraken WJ, Boerman OC, Wolke JG, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. In vitro growth factor release from injectable calcium phosphate cements containing gelatin microspheres. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huse RO, Quinten RP, Wolke JG, Jansen JA. The use of porous calcium phosphate scaffolds with transforming growth factor beta 1 as an onlay bone graft substitute. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:741–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HD, Wozney JM, Li RH. Characterization of a calcium phosphate-based matrix for rhBMP-2. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;238:49–64. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-428-x:49. 49-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee DD, Tofighi A, Aiolova M, Chakravarthy P, Catalano A, Majahad A, Knaack D. alpha-BSM: a biomimetic bone substitute and drug delivery vehicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999:S396–S405. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li RH, Bouxsein ML, Blake CA, D’Augusta D, Kim H, Li XJ, Wozney JM, Seeherman HJ. rhBMP-2 injected in a calcium phosphate paste (alpha-BSM) accelerates healing in the rabbit ulnar osteotomy model. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Link DP, van den DJ, van den Beucken JJ, Wolke JG, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. Bone response and mechanical strength of rabbit femoral defects filled with injectable CaP cements containing TGF-beta 1 loaded gelatin microparticles. Biomaterials. 2008;29:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rammelt S, Neumann M, Hanisch U, Reinstorf A, Pompe W, Zwipp H, Biewener A. Osteocalcin enhances bone remodeling around hydroxyapatite/collagen composites. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;73:284–294. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruhe PQ, Hedberg EL, Padron NT, Spauwen PH, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. rhBMP-2 release from injectable poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/calcium-phosphate cement composites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(Suppl 3):75–81. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300003-00013. 75-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruhe PQ, Kroese-Deutman HC, Wolke JG, Spauwen PH, Jansen JA. Bone inductive properties of rhBMP-2 loaded porous calcium phosphate cement implants in cranial defects in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2123–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeherman HJ, Bouxsein M, Kim H, Li R, Li XJ, Aiolova M, Wozney JM. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 delivered in an injectable calcium phosphate paste accelerates osteotomy-site healing in a nonhuman primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1961–1972. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorensen RG, Wikesjo UM, Kinoshita A, Wozney JM. Periodontal repair in dogs: evaluation of a bioresorbable calcium phosphate cement (Ceredex) as a carrier for rhBMP-2. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:796–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang FW, Khatri CA, Hsii JF, Hirayama S, Takagi S. Polymer-filled calcium phosphate cement: Mechanical properties and protein release. J Dent Res. 2001;80:591. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weir MD, Xu HH. High-strength, in situ-setting calcium phosphate composite with protein release. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85:388–396. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muzzarelli RA, Biagini G, Bellardini M, Simonelli L, Castaldini C, Fratto G. Osteoconduction exerted by methylpyrrolidinone chitosan used in dental surgery. Biomaterials. 1993;14:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90073-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Huse RO, de GK, Buser D, Hunziker EB. Delivery mode and efficacy of BMP-2 in association with implants. J Dent Res. 2007;86:84–89. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowan CM, Aghaloo T, Chou YF, Walder B, Zhang X, Soo C, Ting K, Wu B. MicroCT evaluation of three-dimensional mineralization in response to BMP-2 doses in vitro and in critical sized rat calvarial defects. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:501–512. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, de Boer J, de Groot K. Proliferation and differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells on calcium phosphate/chitosan coatings. J Dent Res. 2008;87:650–654. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ISO/FDIS 4049: Dentistry – polymer-based fillings, restorative and luting materials. Third edition International Organization for Standardization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.ASTM C1421-99: Standard test methods for determination of fracture toughness of advanced ceramics at ambient temperatures. American Society for Testing and Materials; West Conshohochen, PA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu HH, Weir MD, Simon CG. Injectable and strong nano-apatite scaffolds for cell/growth factor delivery and bone regeneration. Dent Mater. 2008;24:1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu HH, Simon CG., Jr. Self-hardening calcium phosphate composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gittens SA, Uludag H. Growth factor delivery for bone tissue engineering. J Drug Target. 2001;9:407–429. doi: 10.3109/10611860108998776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy WL, Kohn DH, Mooney DJ. Growth of continuous bonelike mineral within porous poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:50–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<50::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrades JA, Han B, Becerra J, Sorgente N, Hall FL, Nimni ME. A recombinant human TGF-beta1 fusion protein with collagen-binding domain promotes migration, growth, and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:485–498. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. Fibroblast growth factors. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-3-reviews3005. REVIEWS 3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lane JM. Bone morphogenic protein science and studies. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:S17–S22. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200511101-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruhe PQ, Hedberg EL, Padron NT, Spauwen PH, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. rhBMP-2 release from injectable poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/calcium-phosphate cement composites. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(Suppl 3):75–81. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300003-00013. 75-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durucan C, Brown PW. Low temperature formation of calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite-PLA/PLGA composites. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51:717–725. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000915)51:4<717::aid-jbm21>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy WL, Hsiong S, Richardson TP, Simmons CA, Mooney DJ. Effects of a bone-like mineral film on phenotype of adult human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Biomaterials. 2005;26:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ducheyne P, Qiu Q. Bioactive ceramics: the effect of surface reactivity on bone formation and bone cell function. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pilliar RM, Filiaggi MJ, Wells JD, Grynpas MD, Kandel RA. Porous calcium polyphosphate scaffolds for bone substitute applications -- in vitro characterization. Biomaterials. 2001;22:963–972. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foppiano S, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. The influence of novel bioactive glasses on in vitro osteoblast behavior. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71:242–249. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Livingston T, Ducheyne P, Garino J. In vivo evaluation of a bioactive scaffold for bone tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:1–13. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russias J, Saiz E, Deville S, Gryn K, Liu G, Nalla RK, Tomsia AP. Fabrication and in vitro characterization of three-dimensional organic/inorganic scaffolds by robocasting. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;83:434–445. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hench LL, Polak JM. Third-generation biomedical materials. Science. 2002;295:1014–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1067404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gibson LJ. The Mechanical-Behavior of Cancellous Bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 1985;18:317. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(85)90287-8. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phelps JB, Hubbard GB, Wang X, Agrawal CM. Microstructural heterogeneity and the fracture toughness of bone. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;51:735–741. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000915)51:4<735::aid-jbm23>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suchanek W, Yoshimura M. Processing and properties of hydroxyapatite-based biomaterials for use as hard tissue replacement implants. Journal of Materials Research. 1998;13:94–117. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garrett S. Periodontal regeneration around natural teeth. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:621–666. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maalej M, Li VC. Flexural Tensile-Strength Ratio in Engineered Cementitious Composites. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering. 1994;6:513–528. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valentin-Opran A, Wozney J, Csimma C, Lilly L, Riedel GE. Clinical evaluation of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002:110–120. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedlaender GE, Perry CR, Cole JD, Cook SD, Cierny G, Muschler GF, Zych GA, Calhoun JH, LaForte AJ, Yin S. Osteogenic protein-1 (bone morphogenetic protein-7) in the treatment of tibial nonunions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(Suppl 1):S151–S158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruhe PQ, Kroese-Deutman HC, Wolke JG, Spauwen PH, Jansen JA. Bone inductive properties of rhBMP-2 loaded porous calcium phosphate cement implants in cranial defects in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2123–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsiridis E, Bhalla A, Ali Z, Gurav N, Heliotis M, Deb S, DiSilvio L. Enhancing the osteoinductive properties of hydroxyapatite by the addition of human mesenchymal stem cells, and recombinant human osteogenic protein-1 (BMP-7) in vitro. Injury. 2006;37(Suppl 3):S25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.08.021. S25-S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu HH, Weir MD, Burguera EF, Fraser AM. Injectable and macroporous calcium phosphate cement scaffold. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4279–4287. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu HH, Burguera EF, Carey LE. Strong, macroporous, and in situ-setting calcium phosphate cement-layered structures. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3786–3796. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu HH, Carey LE, Simon CG., Jr. Premixed macroporous calcium phosphate cement scaffold. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:1345–1353. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-0146-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]