Abstract

Advancing age remains the largest risk factor for devastating diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, and cancer. The mechanisms by which advancing age predisposes to disease are now beginning to unfold, due in part, to genetic and environmental manipulations of longevity in lower organisms. Converging lines of evidence suggest that DNA damage may be a final common pathway linking several proposed mechanisms of aging. The present review forwards a theory for an additional aging pathway that involves modes of inherent genetic instability. Long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) are endogenous non-LTR retrotransposons that compose about 20% of the human genome. The LINE-1 (L1) gene products, ORF1p and ORF2p, possess mRNA binding, endonuclease, and reverse transcriptase activity that enable retrotransposition. While principally active only during embryogenesis, L1 transcripts are detected in adult somatic cells under certain conditions. The present hypothesis proposes that L1s act as an ‘endogenous clock’, slowly eroding genomic integrity by competing with the organism’s double-strand break repair mechanism. Thus, while L1s are an accepted mechanism of genetic variation fueling evolution, it is proposed that longevity is negatively impacted by somatic L1 activity. The theory predicts testable hypotheses about the relationship between L1 activity, DNA repair, healthy aging, and longevity.

Keywords: LINE1, aging, DNA damage, longevity, genetic instability

1. Introduction

Advancing age is a powerful risk factor for the major diseases in the Western World, contributing to the onset and progression of at least 87 human diseases (Martin, 2007; Tucker et al., 1999). DNA damage and chromatin abnormalities accumulate during aging and play significant roles in the etiology of many of these diseases (Nijnik et al., 2007). To maintain genomic integrity, sophisticated molecular machineries detect DNA disorder and then assemble enzyme complexes to effect DNA repair and chromatin remodeling. Together, these systems maintain the intricate structural landscape required for the genome’s physiological function. Yet, during aging, these highly evolved DNA repair machineries gradually lose their effectiveness (Li et al., 2008), lending support to many theories which invoke compromised genomic integrity as a root cause of aging (Wilson et al., 2008). Likewise, mutations that affect lifespan frequently occur in DNA repair and genotoxic stress-response pathways, suggesting that the capacity to repair DNA damage plays a key role in determining lifespan (Capri et al., 2006).

Not all DNA damage arises from exogenous insult (Akbari and Krokan, 2008). In addition to environmental and physiochemical causes of DNA damage, high copy number endogenous DNA retroelements have the proven ability to damage, rearrange, and destabilize chromatin (Belgnaoui et al., 2006; Gasior et al., 2006). Could endogenous parasitic retroelements in the human genome act as an endogenous source of DNA damage and catalyze organismal aging? While ubiquitously present in the evolution of the human lineage, and responsible for many evolutionary innovations for the species, DNA retroelements may exact a significant cost by reducing the longevity of the individual. In effect, the DNA retroelements that are sources of genetic variation driving evolution might inherently lead to accumulated DNA damage in aging individuals. Thus, retroelements may play a key role in a novel form of antagonistic pleiotropy, where DNA damage during aging is the cost for the benefits of evolutionary acceleration. This paper explores the potential contribution of the non-LTR retrotransposon L1 to accumulated DNA damage, loss of genomic integrity, and finally to human aging.

2. Aging Pathways converge on DNA damage and repair

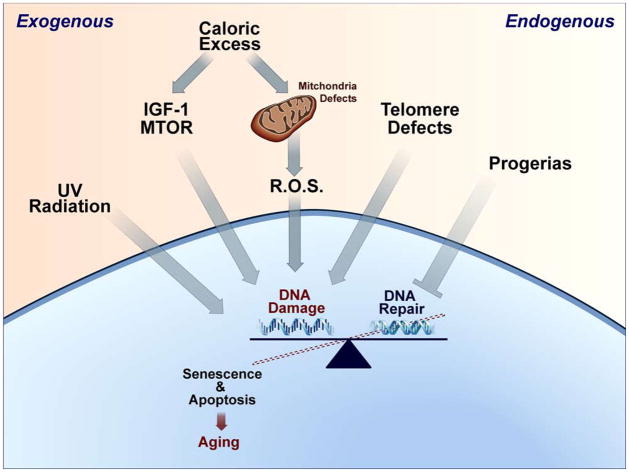

Several theories have attempted to explain the decline in cellular and organismal functions that occur with aging (Wilson et al., 2008). Caloric excess (Holloszy and Fontana, 2007), cellular senescence (Jeyapalan and Sedivy, 2008), and oxidative stress (Balaban et al., 2005) are important current theories of aging. Even though these theories focus on different molecular and cellular pathways, they are connected by common underlying themes of accumulating DNA damage and defects in DNA repair (Wilson et al., 2008). Additional evidence implicating the contribution of DNA damage to aging comes from the progeroid syndromes, in which genetic mutations lead to profoundly accelerated aging. Most of the progerias, including Cockayne Syndrome, Werner’s Syndrome, Bloom’s Syndrome, and Hutchinson-Guilford Syndrome are caused by defects in DNA repair (Bohr et al., 2007; Niedernhofer, 2008). The convergence of these different aging pathways on DNA damage and repair is schematically summarized in Figure 1. In addition to these known mechanisms, it is worthwhile to consider whether endogenous retroelements could be an additional source of DNA damage.

Figure 1. Aging theories converge on accumulated DNA damage.

Exogenous factors, such as UV irradiation, caloric excess, alterations in the IGF/mTOR pathways, and oxidative stress can alter the cellular balance between DNA damage and repair. Similarly, endogenous pathways such as telomere regulation and genetic defects in DNA repair can lead to cellular senescence and premature aging. These effects are of added importance when they alter stem cell regenerative activity.

3. The LINE element: a catalyst for evolution

Barbara McClintock first observed in the early 1940s that the presence or absence of mobile genetic elements (transposons) could affect gene expression, as evidenced by color variations in maize (McClintock, 1950), a discovery that would lead to the Nobel Prize in 1983. Beyond plants, virtually every higher eukaryote has active retrotransposons, and they impact host genomes in ways still under intense investigation, as recently reviewed by Kazazian (Kazazian, 2004). Perhaps the most successful genetic parasite, the Long Interspersed Nuclear Element-1 (LINE-1, or L1) occupies large percentages of mammalian genomes. There are one thousand full-length and hundreds of thousands of truncated L1 elements in humans that comprise 17% of the human genome (Lander et al., 2001). L1 is one of the best characterized retroelements and lacks a long terminal repeat (LTR) characteristic of many other retroelements. In the present review, we’ll use the example of L1 to discuss how retroelements have benefitted evolution, but potentially at a cost to the longevity of individual.

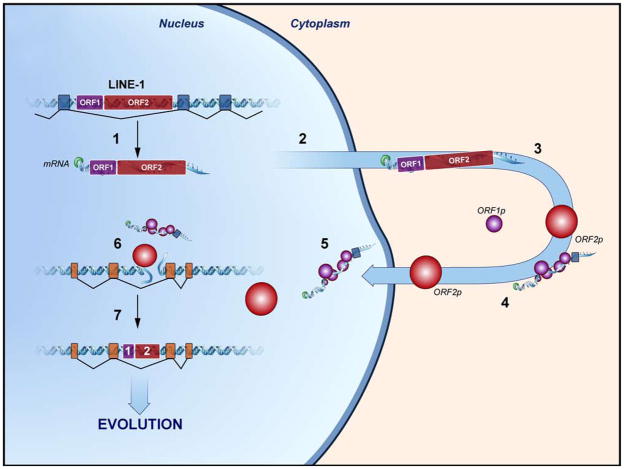

3.1 L1 Components: A bridge from RNA to DNA

The full-length L1 gene is 6.5 kb, which includes a 900 bp 5′ UTR, two open reading frames, ORF1 and ORF2, and a short 3′ UTR. Following transcription, the L1 transcript is polyadenylated and moves to the cytoplasm, where ORF1 and ORF2 are translated into ORF1 protein (ORF1p) and ORF2 protein (ORF2p). ORF1p, an RNA binding protein, can bind L1 transcripts and return them to the nucleus for reintegration into the host genome. Reintegration is facilitated mostly by ORF2p, which possesses both endonuclease and reverse transcriptase activities. Reintegration begins when ORF2p nicks the genomic DNA and uses the free 3′ hydroxyl group to prime the reverse transcription of the L1 transcript, also carried out by ORF2p (Feng et al., 1996). For this reason, the reintegration process is termed target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT)(Luan and Eickbush, 1996; Martin et al., 2005). Second strand nicking and ligation by unknown mechanisms completes the reintegration. For a comprehensive review of mammalian retroelements, see Deininger et al (Deininger and Batzer, 2002).

The L1 proteins together facilitate a pathway of information flow, from transcriptome to genome (RNA to DNA), uniquely positioned to acquire information from the environment in the form of differentially processed, even modified RNAs, and inserting this information back into the genome. As more species’ genomes are sequenced, the contribution of L1 elements to mammalian evolution becomes clearer. A detailed phylogenetic analysis of the hundreds of thousands of L1 elements in the genome indicates that L1 has been replicating in mammalian genomes for over 150 million years (Lander et al., 2001). During that time period, L1 thrived in mammalian genomes, replicating its own sequence to the point that there are now over 500,000 L1 elements in the human genome.

3.2 L1-mediated Alu transposition accelerates genome evolution

The impact of L1 on mammalian evolution might not have been so pronounced without the contribution of Alu retrotransposons. Alu elements, named for their susceptibility to the Alu restriction enzyme, is a family of Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs) that are about 300 bp in length and transcribed by RNA Polymerase III. Alu elements differ from L1 elements in that they are non-autonomous elements; their short length prohibits them from coding for proteins enabling their own retrotransposition. Instead, Alu elements use L1 proteins for their retrotransposition. L1 ORF1p and ORF2p will bind and reintegrate Alu by virtue of primary and secondary structure homology with L1 3′ sequence. Such molecular mimicry by Alu has resulted in over two million Alu elements that occupy about 10% of the human genome, and facilitates several potential evolutionary mechanisms (Mattick and Mehler, 2008).

3.3 Homologous recombination between repeats

Each new L1 or Alu insertion increases the number of homologous sequences present in the genome. With increasing sequence homology in the genome, the likelihood of homologous recombination increases. With so many homologous elements in the genome, especially Alu elements, the chances of unequal recombination are far greater than equal recombination. Consequently, the risks of gene deletion or gene duplication events are significant. For example, the redundancy of the globin gene cluster is attributed to unequal homologous recombination between L1 elements (Fitch et al., 1991).

3.4 L1 retrotransposes pseudogenes

Computational searches have identified as many as 23,000–33,000 processed pseudogenes in the human genome (Goncalves et al., 2000). Processed pseudogenes captured by L1 elements and inserted into genomic DNA significantly outnumber pseudogenes from gene duplication events, a mechanism previously thought to have driven the majority of evolutionary diversity in the human lineage (Ohshima et al., 2003). The tumor suppressor RHOB provides an example of a processed pseudogene that has acquired function in the human genome (Sakai et al., 2007). It is now believed that L1 retrotransposition activities “govern a significant portion of genome evolution” and provide a major mechanism of genomic plasticity (Zhang et al., 2003).

3.5 L1 transcription leads to 3′ transduction

At the 3′ end of L1, a weak poly-A addition site in L1 sequences results in frequent transcriptional read-through from the L1 into adjacent 3′ flanking sequences (Szak et al., 2003). This process, called 3′ transduction, can incorporate flanking sequences into the L1 RNA, thereby transposing them to new sites in the genome. Studies spanning the last decade have revealed a large number of evolutionary events recorded in mammalian, as well as human genomes that implicate L1’s transduction activity in the creation of many new genomic features (Brandt et al., 2005; Buzdin et al., 2003; Jordan et al., 2003).

4. L1 activity alters gene expression and contributes to DNA damage

Within the large population of L1 elements, the vast majority of the approximately 500,000 total copies of L1 in the human genome are not capable of transposition on their own due to truncations and inactivating mutations. However, approximately 80 to 100 copies of family L1PA1 remain fully functional, capable of transcription, translation, replication and retrotransposition, via an RNA intermediate (Brouha et al., 2003). In fact, it is estimated that roughly 1 in 30 individuals has a novel L1 insertion. Although most of these insertions are likely to be harmless (Kazazian, 1999), insertions within exons or important regulatory regions is known to cause genetic diseases. Importantly, because of their bidirectional promoter activity, the insertion of truncated L1 5′ promoter regions into DNA near existing genes can result in changes in the expression of neighboring genes.

4.1 L1 activity causes genetic disease

In humans, recently retrotransposed L1 elements have generated molecular lesions in numerous inherited disorders. For example, L1 elements have disrupted the PDHX gene of a patient with PDHC deficiency (Mine et al., 2007), the Factor VIII gene in patients with hemophilia (Kazazian et al., 1988), and the APC gene in patients with colon cancer (van den Hurk et al., 2007), to name a few. Mediated by L1 proteins, Alu insertions in genes such as CFTR(Chen et al., 2008) and BRCA1(Deininger and Batzer, 1999) contribute to disease in many individuals. In addition to disease-causing transposition events, Alu elements increase the occurrence of non-allelic homologous recombination, which causes about 0.3% of human genetic diseases. For a comprehensive review of L1 transposition in human disease see Ostertag (Ostertag and Kazazian, 2001).

4.2 L1 activity causes DNA damage and cellular senescence

The intrinsic endonuclease activity of L1-derived ORF2 protein when expressed in human cells in vitro leads to apoptosis, DNA damage, and cellular senescence (Wallace et al., 2008). Evidence in human cells demonstrates that forced overexpression of L1 activity from multicopy plasmids leads to a high-level of DSBs, resulting in obvious H2AX foci (Gasior et al., 2006), which is a common feature of senescent cells (Scaffidi and Misteli, 2006). Likewise, episomal expression of L1s, followed by selection, capture, and sequencing of the genomic L1 integrants provides direct evidence of genetic instability in the form of L1 and chromosomal inversions, insertions, exon deletions, and flanking sequence comobilization (Gilbert et al., 2002; Symer et al., 2002).

Due to highly evolved and efficient repair mechanisms, only a small percentage of nicks result in sustained damage or retrotransposition, but each event carries a finite risk of imperfect repair, creating competition between damage and repair (Gilbert et al., 2005). Thus, the cumulative effect would produce an accumulation of point mutations, rearrangements, damaged chromatin, and eventually replicative stress. These DNA breaks and misrepairs are proposed to accumulate with age, eventually activating p16/pRB and p53 cellular senescence pathways in cells challenged to proliferate. It is interesting to speculate that human extrachromosomal inter-Alu DNA circles, a prominent feature of aged cells (Lumpkin et al., 1985), may result from chronic low-level L1 activity.

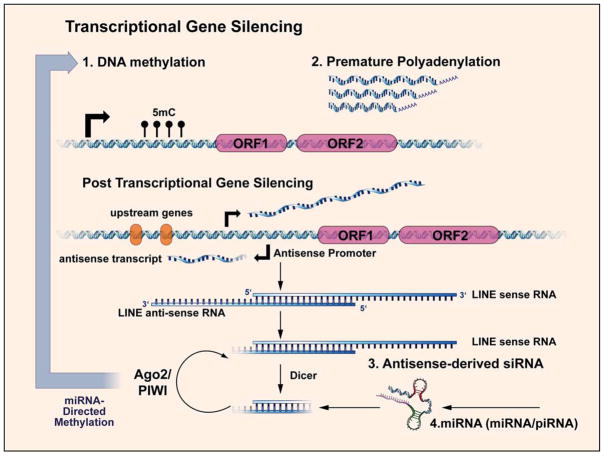

4.3 Multiple mechanisms of regulation and inhibition of LINE activity

Given the potential of retrotransposition and endonuclease activities to cause genomic damage, it follows that several sophisticated mechanisms have evolved to limit and regulate L1 activity in the germ line and in somatic cells (Shi et al., 2007). In fact, comprehensive analysis of the rate of expansion of L1 families suggest that the most advanced mammalian species have the highest ability to restrict L1 expression (Boissinot et al., 2000). These mechanisms include several layers of transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing mechanisms (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cellular mechanisms limiting selfish retroelements in mammals.

L1 transcription is suppressed by DNA methylation and can be interrupted by premature polyadenylation. An antisense promoter residing within the L1 promoter can generate antisense L1 transcripts and lead to transcription of neighboring 5′ sequences. RNA interference can also regulate L1 post-transcriptionally via small RNAs facilitated by Argonaute and PIWI proteins. Small RNAs may in-turn direct DNA methylation.

Epigenetic regulation

Epigenetics represents a significant mechanism of L1 regulation. Some authors have proposed that methylation (Bestor and Tycko, 1996; Yoder et al., 1997), imprinting (McDonald et al., 2005), and heterochromatin formation (Lippman et al., 2004) may have originated as defenses against the activities of transposable elements. Among these, DNA methylation is the best established mechanism of L1 transcriptional regulation and may influence heterochromatin formation (Hata and Sakaki, 1997; Richardson, 2003; Yu et al., 2001). Methylation measurements of L1 promoters indicate that they range from 20% to 100% methylated (Phokaew et al., 2008). Likewise, consistent with the relationship between DNA damage and senescence, such epigenetic regulation of L1 may be imperfect and susceptible to loss of control with age (Mays-Hoopes et al., 1986). Oxidative damage affects CpG islands, leading to spontaneous hydrolytic deamination reactions that cause permanent C to T transitions (Coulondre et al., 1978). Demethylation of CpG rich L1 promoters would enhance promoter activity and increase expression of L1s and flanking genes, by virtue of de-silencing. For example, hypomethylation of L1 is implicated in CML progression (Roman-Gomez et al., 2005).

Premature polyadenylation

Another potentially important mechanism of L1 regulation is that L1s appear prone to premature polyadenylation within coding regions of the transcript, resulting in L1 transcripts that are generally incapable of transposition and would likewise generally lack endonuclease activity derived from ORF2p (Perepelitsa-Belancio and Deininger, 2003).

Endogenous antisense promoter and RNA interference

PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs)(Aravin et al., 2007) and endogenous siRNAs (Czech et al., 2008; Girard et al., 2006; Hock and Meister, 2008; Kawamura et al., 2008; O’Donnell and Boeke, 2007; Peters and Meister, 2007; Yang and Kazazian, 2006) represent two populations of non-coding RNAs whose action limits L1 expression. For example, knockout of Nct1/2, two ncRNAs encoding piRNAs, leads to dramatic increases in L1 transcripts and ORF1p in mice (Xu et al., 2008). Dicer knock-out increases intracisternal A particle (IAP) retrotransposons and L1 transcripts in mouse ES cells (Kanellopoulou et al., 2005), presumably because intrinsic antisense promoter activity in L1 results in the production of double stranded (ds) RNA that is subsequently cleaved by Dicer’s RNAse III activity into endogenous siRNAs (Soifer et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) may direct DNA methylation at the L1 promoter (Ronemus and Martienssen, 2005), and this might be one mechanism by which the L1 DNA methylation is maintained. RNA editing by APOBEC3 and other proteins may be another critical mechanism of suppressing L1 activity (Muckenfuss et al., 2006).

5. L1 expression and a proposed mechanism for human aging

Current thinking suggests that ORF2p nicks chromosomal DNA non-specifically at perhaps hundreds of locations in advance of a successful retrotransposition event (Wallace et al., 2008). Nonetheless, there is currently no consensus on the overall somatic impact of L1 nicking and retrotransposition on DNA integrity. It has been suggested that given their “well documented deleterious effects, the persistence of L1 activity remains a puzzle” (Boissinot et al., 2004). The debate includes such questions as: Are L1 elements colonizers of their hosts, or have the hosts co-opted the elements? Do L1 elements pose a long-term liability, or asset to the host organism (Belancio et al., 2008)? The following sections discuss these two contrasting effects of L1 elements on the human system, in particular, how both effects can coexist in the human organism.

Much of the attention surrounding L1 expression focuses on when L1 activity leads to genetic disease from either an insertion event or deleterious homologous recombination event. But what is the fate of the cell that has L1 expression, but not a successful retrotransposition event? What consequences occur from L1 ORF2p-mediated DNA damage, accumulated throughout the lifetime of an adult stem cell? Here, we hypothesize that L1 retrotransposon-mediated DNA damage accumulates with chronological age, consequently driving a decline in the regenerative capacity of progenitor populations and physiological aging of tissues. Despite the various defense systems discussed previously, L1 expression seems to occur not only in the germ line, but also in some somatic cells such as endothelial cells, and in somatic tumors and tumor cell lines (Bratthauer et al., 1994; Ergun et al., 2004). If maintained over decades, even a very low level of L1 activity could lead to progressive accumulation of DNA damage, genomic instability, increased replicative stress, and cellular senescence. The most deleterious effects of L1-induced damage would occur in the subpopulation of adult stem cells that respond to tissue regeneration signals.

5.1 L1 Expression in mammalian somatic tissues

Previously, the consensus was that L1 expression occurs only during embryogenesis (Branciforte and Martin, 1994), because global demethylation would permit transcription from otherwise heavily methylated L1 promoters. More recent studies demonstrate a wider prevalence of L1 expression in adult somatic cells, often with adverse consequences. L1-derived transcripts are expressed in rheumatoid arthritis (Neidhart et al., 2000), in cardiac tissue (Lucchinetti et al., 2006), and in several different types of cancer (Asch et al., 1996; Menendez et al., 2004). Importantly, in human cancer cell lines, 5′ and 3′ RACE combined with 454 deep sequencing has identified expression of distinct full-length elements (Rangwala et al., 2009). Using an antibody to the ORF2 protein, expression of this key L1 product has been detected in fetal cells, adult germ cells, and vascular endothelial cells, in some instances (Ergun et al., 2004).

5.2 L1 Expression induced during stress

The expression of L1 increases following exposure to cadmium (Kale et al., 2006), benzo[a]pyrene, a ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Stribinskis and Ramos, 2006), gamma radiation (Farkash et al., 2006), and metabolic oxidative stress (Rockwood et al., 2004). L1 transcript levels also increase after ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) in the rat heart, and siRNA-mediated suppression of L1 leads to improved function after I/R(Lucchinetti et al., 2006). Paradoxically, mobile element activation occurs after exposure to several common DNA damaging agents including chemotherapeutic drugs and gamma-radiation, even though they contribute further to DNA damage (Hagan and Rudin, 2002).

The cellular stress response may have originated with evolutionary mechanisms because many organisms increase genotypic and phenotypic variation during stress, presumably to increase their adaption to environmental changes. Transposon activity is now one of the recognized mechanisms of this stress-induced variability (Rando and Verstrepen, 2007). In some cases, organisms can influence the timing and the location of this variability. It is plausible that L1 activity facilitates a feedback loop, whereby increased expression of the L1 machinery during stress would facilitate search and capture of new information for improved adaptive responses to the stress, or minimally, to generate random variants which can undergo natural selection. While many theories have connected stress to aging, the observed increase in L1 expression with various forms of stress might provide an additional mechanistic link.

5.3 Does L1 activity correlate with lifespan in mammalian species?

It is a straightforward prediction of this theory that species with high L1 activity, particularly in somatic stem/progenitor cells, should have shorter lifespans than species with low L1 activity. While data in this area is scarce, estimates of the number of full-length, functional L1 elements in modern humans average between 80 and 100(Brouha et al., 2003), the mouse contains over 3000 functional copies (DeBerardinis et al., 1998; Kazazian and Moran, 1998), creating a 50-fold greater potential for L1-mediated DNA damage in mouse than in human. Meanwhile, in a comparison of chimpanzees (mean life expectancy of 52 years) and human (worldwide mean life expectancy of 67.2 years), Berezikov et al. observed greater numbers of repeat-associated sequences in chimpanzee transcriptomes than in human (Berezikov et al., 2006).

The recent evolutionary history of L1 elements shows interesting differences among different mammals. Though analysis of retrotransposed pseudogenes in the mouse genome reveals an exponential and monotonic decline in distribution with evolutionary age, it nevertheless provides evidence of unabated L1 activity through recent history to the present (Sakai et al., 2007). In contrast, human L1 retrotransposition events show a distinctively different bimodal distribution with a peak of activity in evolutionary time less than 40 million years ago (Devor and Moffat-Wilson, 2003). These patterns suggest that in the human lineage, molecular machineries evolved during the last 50 million years to partially control L1 expression and activity. Perhaps the notable extension of lifespan in hominids required greater control over L1 expression due to the prolonged period in which adult stem cells would be required for tissue repair and regeneration. A testable hypothesis is that an increasing number and activity of LINE-like elements would shorten the lifespan of a species. Conversely, it would be technically feasible to experimentally increase LINE numbers or activity in a given species such as a mouse, and directly determine the effect on lifespan.

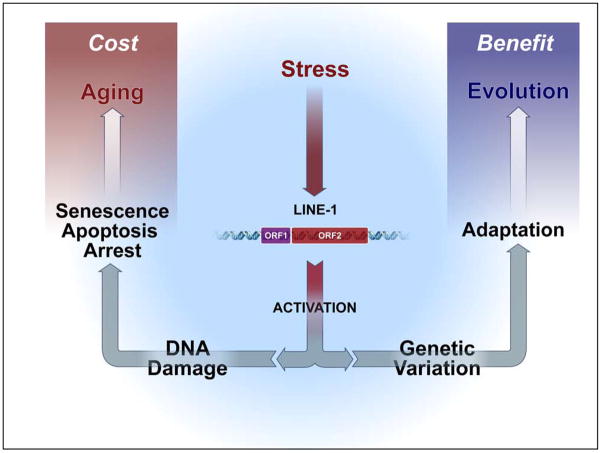

5.4 Pleiotropic effects of L1s on evolution versus longevity

Among the earliest observations of the genetic contributions to aging by Williams, was the recognition that particular genes or traits could have beneficial effects during the reproductive phase, but have an expense on the longevity of the organism after reproduction, an effect termed “antagonistic pleiotropy” (Williams, 1957). Cellular senescence exhibits elements of antagonistic pleiotropy, in the sense that while limiting tumorigenesis in youth, it limits regeneration in the elderly, a central concept in the modern theories of aging (Campisi, 2002; Muckenfuss et al., 2006). Thus, antagonistic pleiotropy may help to describe some of the complexities of aging in multicellular organisms (Parsons, 2007).

This duality of effect for a single gene or phenotype within an individual can be extended to the species in general, whereby the pleiotropic effects of L1 elements may have a broad benefit to the adaptive variation of a species, while having a distinct expense to the longevity of individual members. The many beneficial evolutionary events mediated by L1s contrast with their clear adverse consequences for genomic integrity in any somatic cells that might express them. In effect, the cost of innovation during human evolution results in accumulated DNA damage for the individuals of the species: the roots of our evolutionary tree become the seeds of our personal destruction.

6. Conclusion

It appears that L1s serve a crucial role in facilitating human evolution by producing active genetic variation in our ancestral populations. At the same time, such a broad benefit to the evolution of the species may come at the cost of limitations to the longevity of individual members of the species. It is proposed that the balance between L1-induced DNA damage and DNA repair may be compromised by various stressors, resulting in accumulated L1-induced damage with age. Because dsDNA breaks stimulate chronic low-level inflammatory signals, L1-mediated DNA damage may be a component of the human inflamm-aging phenotype (Franceschi et al., 2007; Rodier et al., 2009).

We offer the LINEage theory, not as replacement for existing theories, but as a potentially new component for further consideration and examination. It is our purpose to stimulate awareness of this important and expanding field of study, which is intricately tied to innate immunity, RNA interference, RNA editing, and genomic stability. The LINEage theory does not exclude the important roles of oxidative damage, caloric excess, and telomeric regulation, for instance. Rather, this new theory has the potential to augment our understanding and fuel new investigation. Limited direct evidence exists in support of this theory to date, so it should be considered speculative and subjected to rigorous scientific examination. Originally perhaps, L1s were an invading retroviral pathogen whose host eventually co-opted the intruder and turned a nucleic acid-based parasite into an evolution-accelerating machine. However, accumulated L1-induced damage represents a potential new source for age-related decline in cellular functions, which ultimately contribute to the frailty of diverse tissues during aging.

Figure 2. The L1 life cycle facilitates genomic integration of RNA transcripts.

1) L1 transcription and 3′ transduction. 2) L1 transcripts are exported to the cytoplasm. 3) L1 transcripts undergo bicistronic translation of ORF1 and ORF2 yielding ORF1p and ORF2p, respectively. 4) L1 ORF1p binds L1 transcripts in the cytoplasm and form a ribonucleoprotein complex. 5) The L1 RNP complex migrates to the nucleus. 6) ORF2p nicks the genomic DNA and initiates target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT). 7) Integration occurs in the genomic DNA, which increases genome size, promotes exon shuffling, and increases L1 & Alu copy number.

Figure 4. LINEage Theory.

Acute stress can activate L1 elements leading to transient DNA damage, and rarely to insertional events, which accumulate over a lifetime. L1 ORF1p and ORF2p are equipped with capabilities to alter the genomic landscape that has accelerated evolution, but at the expense of accumulated DNA damage and altered cell fate. This dichotomous nature of L1 may represent another example of antagonistic pleiotropy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the generous support of the NIH/National Institutes on Aging MERIT Award (T.M.) and the St. Laurent Institute. The careful review and constructive input of Dr. Robert Reenan (Brown University) is greatly appreciated, as well as the graphical support provided by Mr. Mark Mazaitis.

Abbreviations

- LINE

Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements

- SINE

Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements

- L1

LINE-1

- UTR

untranslated region

- ORF

open reading frame

- ORF1p

L1 ORF1 protein

- ORF2p

L1 ORF2 protein

- RHOB

ras homolog gene family, member B

- PDHX

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, component X

- PDHC

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- APC

Adenomatosis Polyposis Coli tumor suppressor

- BRCA1

Breast Cancer 1

- H2AX

Histone H2AX

- DSB

pRB

- IAP

Intracisternal A particle

- miRNA

microRNA

- piRNA

PIWI-interacting RNAs

- I/R

Ischemia-Reperfusion

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akbari M, Krokan HE. Cytotoxicity and mutagenicity of endogenous DNA base lesions as potential cause of human aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:353–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin AA, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J. The Piwi-piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon arms race. Science. 2007;318:761–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1146484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch HL, Eliacin E, Fanning TG, Connolly JL, Bratthauer G, Asch BB. Comparative expression of the LINE-1 p40 protein in human breast carcinomas and normal breast tissues. Oncol Res. 1996;8:239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belancio VP, Hedges DJ, Deininger P. Mammalian non-LTR retrotransposons: for better or worse, in sickness and in health. Genome Res. 2008;18:343–58. doi: 10.1101/gr.5558208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgnaoui SM, Gosden RG, Semmes OJ, Haoudi A. Human LINE-1 retrotransposon induces DNA damage and apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2006;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Thuemmler F, van Laake LW, Kondova I, Bontrop R, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. Diversity of microRNAs in human and chimpanzee brain. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1375–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor TH, Tycko B. Creation of genomic methylation patterns. Nat Genet. 1996;12:363–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr VA, Ottersen OP, Tonjum T. Genome instability and DNA repair in brain, ageing and neurological disease. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1183–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissinot S, Chevret P, Furano AV. L1 (LINE-1) retrotransposon evolution and amplification in recent human history. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:915–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissinot S, Roos C, Furano AV. Different rates of LINE-1 (L1) retrotransposon amplification and evolution in New World monkeys. J Mol Evol. 2004;58:122–30. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2539-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branciforte D, Martin SL. Developmental and cell type specificity of LINE-1 expression in mouse testis: implications for transposition. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2584–92. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Schrauth S, Veith AM, Froschauer A, Haneke T, Schultheis C, Gessler M, Leimeister C, Volff JN. Transposable elements as a source of genetic innovation: expression and evolution of a family of retrotransposon-derived neogenes in mammals. Gene. 2005;345:101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratthauer GL, Cardiff RD, Fanning TG. Expression of LINE-1 retrotransposons in human breast cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:2333–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940501)73:9<2333::aid-cncr2820730915>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouha B, Schustak J, Badge RM, Lutz-Prigge S, Farley AH, Moran JV, Kazazian HH., Jr Hot L1s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5280–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831042100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzdin A, Gogvadze E, Kovalskaya E, Volchkov P, Ustyugova S, Illarionova A, Fushan A, Vinogradova T, Sverdlov E. The human genome contains many types of chimeric retrogenes generated through in vivo RNA recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4385–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Between Scylla and Charybdis: p53 links tumor suppression and aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:567–73. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capri M, Salvioli S, Sevini F, Valensin S, Celani L, Monti D, Pawelec G, De Benedictis G, Gonos ES, Franceschi C. The genetics of human longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:252–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, Masson E, Macek M, Jr, Raguenes O, Piskackova T, Fercot B, Fila L, Cooper DN, Audrezet MP, Ferec C. Detection of two Alu insertions in the CFTR gene. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulondre C, Miller JH, Farabaugh PJ, Gilbert W. Molecular basis of base substitution hotspots in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1978;274:775–80. doi: 10.1038/274775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Malone CD, Zhou R, Stark A, Schlingeheyde C, Dus M, Perrimon N, Kellis M, Wohlschlegel JA, Sachidanandam R, et al. An endogenous small interfering RNA pathway in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature07007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Goodier JL, Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH., Jr Rapid amplification of a retrotransposon subfamily is evolving the mouse genome. Nat Genet. 1998;20:288–90. doi: 10.1038/3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:183–93. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Mammalian retroelements. Genome Res. 2002;12:1455–65. doi: 10.1101/gr.282402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor EJ, Moffat-Wilson KA. Molecular and temporal characteristics of human retropseudogenes. Hum Biol. 2003;75:661–72. doi: 10.1353/hub.2003.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergun S, Buschmann C, Heukeshoven J, Dammann K, Schnieders F, Lauke H, Chalajour F, Kilic N, Stratling WH, Schumann GG. Cell type-specific expression of LINE-1 open reading frames 1 and 2 in fetal and adult human tissues. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27753–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkash EA, Kao GD, Horman SR, Prak ET. Gamma radiation increases endonuclease-dependent L1 retrotransposition in a cultured cell assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1196–204. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q, Moran JV, Kazazian HH, Jr, Boeke JD. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell. 1996;87:905–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81997-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch DH, Bailey WJ, Tagle DA, Goodman M, Sieu L, Slightom JL. Duplication of the gamma-globin gene mediated by L1 long interspersed repetitive elements in an early ancestor of simian primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7396–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior SL, Wakeman TP, Xu B, Deininger PL. The human LINE-1 retrotransposon creates DNA double-strand breaks. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:1383–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert N, Lutz S, Morrish TA, Moran JV. Multiple fates of L1 retrotransposition intermediates in cultured human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7780–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7780-7795.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert N, Lutz-Prigge S, Moran JV. Genomic deletions created upon LINE-1 retrotransposition. Cell. 2002;110:315–25. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature04917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves I, Duret L, Mouchiroud D. Nature and structure of human genes that generate retropseudogenes. Genome Res. 2000;10:672–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.5.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan CR, Rudin CM. Mobile genetic element activation and genotoxic cancer therapy: potential clinical implications. Am J Pharmacogenomics. 2002;2:25–35. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200202010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata K, Sakaki Y. Identification of critical CpG sites for repression of L1 transcription by DNA methylation. Gene. 1997;189:227–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock J, Meister G. The Argonaute protein family. Genome Biol. 2008;9:210. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Caloric restriction in humans. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:709–12. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyapalan JC, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence and organismal aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:467–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan IK, Rogozin IB, Glazko GV, Koonin EV. Origin of a substantial fraction of human regulatory sequences from transposable elements. Trends Genet. 2003;19:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale SP, Carmichael MC, Harris K, Roy-Engel AM. The L1 retrotranspositional stimulation by particulate and soluble cadmium exposure is independent of the generation of DNA breaks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2006;3:121–8. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2006030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, Livingston DM, Rajewsky K. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura Y, Saito K, Kin T, Ono Y, Asai K, Sunohara T, Okada TN, Siomi MC, Siomi H. Drosophila endogenous small RNAs bind to Argonaute 2 in somatic cells. Nature. 2008;453:793–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian HH., Jr An estimated frequency of endogenous insertional mutations in humans. Nat Genet. 1999;22:130. doi: 10.1038/9638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian HH., Jr Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science. 2004;303:1626–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian HH, Jr, Moran JV. The impact of L1 retrotransposons on the human genome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian HH, Jr, Wong C, Youssoufian H, Scott AF, Phillips DG, Antonarakis SE. Haemophilia A resulting from de novo insertion of L1 sequences represents a novel mechanism for mutation in man. Nature. 1988;332:164–6. doi: 10.1038/332164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Mitchell JR, Hasty P. DNA double-strand breaks: a potential causative factor for mammalian aging? Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:416–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman Z, Gendrel AV, Black M, Vaughn MW, Dedhia N, McCombie WR, Lavine K, Mittal V, May B, Kasschau KD, et al. Role of transposable elements in heterochromatin and epigenetic control. Nature. 2004;430:471–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan DD, Eickbush TH. Downstream 28S gene sequences on the RNA template affect the choice of primer and the accuracy of initiation by the R2 reverse transcriptase. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4726–34. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti E, Feng J, Silva R, Tolstonog GV, Schaub MC, Schumann GG, Zaugg M. Inhibition of LINE-1 expression in the heart decreases ischemic damage by activation of Akt/PKB signaling. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25:314–24. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00251.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin CK, Jr, McGill JR, Riabowol KT, Moerman EJ, Reis RJ, Goldstein S. Extrachromosomal circular DNA and aging cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1985;190:479–93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-7853-2_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM. The genetics and epigenetics of altered proliferative homeostasis in ageing and cancer. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Li WL, Furano AV, Boissinot S. The structures of mouse and human L1 elements reflect their insertion mechanism. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:223–8. doi: 10.1159/000084956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick JS, Mehler MF. RNA editing, DNA recoding and the evolution of human cognition. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays-Hoopes L, Chao W, Butcher HC, Huang RC. Decreased methylation of the major mouse long interspersed repeated DNA during aging and in myeloma cells. Dev Genet. 1986;7:65–73. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020070202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1950;36:344–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JF, Matzke MA, Matzke AJ. Host defenses to transposable elements and the evolution of genomic imprinting. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:242–9. doi: 10.1159/000084958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez L, Benigno BB, McDonald JF. L1 and HERV-W retrotransposons are hypomethylated in human ovarian carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine M, Chen JM, Brivet M, Desguerre I, Marchant D, de Lonlay P, Bernard A, Ferec C, Abitbol M, Ricquier D, et al. A large genomic deletion in the PDHX gene caused by the retrotranspositional insertion of a full-length LINE-1 element. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:137–42. doi: 10.1002/humu.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muckenfuss H, Hamdorf M, Held U, Perkovic M, Lower J, Cichutek K, Flory E, Schumann GG, Munk C. APOBEC3 proteins inhibit human LINE-1 retrotransposition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22161–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhart M, Rethage J, Kuchen S, Kunzler P, Crowl RM, Billingham ME, Gay RE, Gay S. Retrotransposable L1 elements expressed in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue: association with genomic DNA hypomethylation and influence on gene expression. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2634–47. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2634::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer LJ. Tissue-specific accelerated aging in nucleotide excision repair deficiency. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:408–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijnik A, Woodbine L, Marchetti C, Dawson S, Lambe T, Liu C, Rodrigues NP, Crockford TL, Cabuy E, Vindigni A, et al. DNA repair is limiting for haematopoietic stem cells during ageing. Nature. 2007;447:686–90. doi: 10.1038/nature05875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell KA, Boeke JD. Mighty Piwis defend the germline against genome intruders. Cell. 2007;129:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima K, Hattori M, Yada T, Gojobori T, Sakaki Y, Okada N. Whole-genome screening indicates a possible burst of formation of processed pseudogenes and Alu repeats by particular L1 subfamilies in ancestral primates. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R74. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-11-r74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH., Jr Biology of mammalian L1 retrotransposons. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:501–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons PA. Antagonistic pleiotropy and the stress theory of aging. Biogerontology. 2007;8:613–7. doi: 10.1007/s10522-007-9101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepelitsa-Belancio V, Deininger P. RNA truncation by premature polyadenylation attenuates human mobile element activity. Nat Genet. 2003;35:363–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters L, Meister G. Argonaute proteins: mediators of RNA silencing. Mol Cell. 2007;26:611–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phokaew C, Kowudtitham S, Subbalekha K, Shuangshoti S, Mutirangura A. LINE-1 methylation patterns of different loci in normal and cancerous cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5704–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando OJ, Verstrepen KJ. Timescales of genetic and epigenetic inheritance. Cell. 2007;128:655–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala SH, Zhang L, Kazazian HH., Jr Many LINE1 elements contribute to the transcriptome of human somatic cells. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-9-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson B. Impact of aging on DNA methylation. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:245–61. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood LD, Felix K, Janz S. Elevated presence of retrotransposons at sites of DNA double strand break repair in mouse models of metabolic oxidative stress and MYC-induced lymphoma. Mutat Res. 2004;548:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Munoz DP, Raza SR, Freund A, Campeau E, Davalos AR, Campisi J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:973–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Gomez J, Jimenez-Velasco A, Agirre X, Cervantes F, Sanchez J, Garate L, Barrios M, Castillejo JA, Navarro G, Colomer D, et al. Promoter hypomethylation of the LINE-1 retrotransposable elements activates sense/antisense transcription and marks the progression of chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2005;24:7213–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronemus M, Martienssen R. RNA interference: methylation mystery. Nature. 2005;433:472–3. doi: 10.1038/433472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H, Koyanagi KO, Imanishi T, Itoh T, Gojobori T. Frequent emergence and functional resurrection of processed pseudogenes in the human and mouse genomes. Gene. 2007;389:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P, Misteli T. Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science. 2006;312:1059–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1127168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. Cell divisions are required for L1 retrotransposition. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1264–70. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01888-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soifer HS, Zaragoza A, Peyvan M, Behlke MA, Rossi JJ. A potential role for RNA interference in controlling the activity of the human LINE-1 retrotransposon. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:846–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stribinskis V, Ramos KS. Activation of human long interspersed nuclear element 1 retrotransposition by benzo(a)pyrene, an ubiquitous environmental carcinogen. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2616–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symer DE, Connelly C, Szak ST, Caputo EM, Cost GJ, Parmigiani G, Boeke JD. Human L1 retrotransposition is associated with genetic instability in vivo. Cell. 2002;110:327–38. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szak ST, Pickeral OK, Landsman D, Boeke JD. Identifying related L1 retrotransposons by analyzing 3′ transduced sequences. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R30. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-r30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JD, Spruill MD, Ramsey MJ, Director AD, Nath J. Frequency of spontaneous chromosome aberrations in mice: effects of age. Mutat Res. 1999;425:135–41. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hurk JA, Meij IC, Seleme MC, Kano H, Nikopoulos K, Hoefsloot LH, Sistermans EA, de Wijs IJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Plomp AS, et al. L1 retrotransposition can occur early in human embryonic development. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1587–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace NA, Belancio VP, Deininger PL. L1 mobile element expression causes multiple types of toxicity. Gene. 2008;419:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC. Pleitropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution. 1957;11:398–411. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DM, 3rd, Bohr VA, McKinnon PJ. DNA damage, DNA repair, ageing and age-related disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, You Y, Hunsicker P, Hori T, Small C, Griswold MD, Hecht NB. Mice deficient for a small cluster of Piwi-interacting RNAs implicate Piwi-interacting RNAs in transposon control. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:51–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.068072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Kazazian HH., Jr L1 retrotransposition is suppressed by endogenously encoded small interfering RNAs in human cultured cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:763–71. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Zhang L, Kazazian HH., Jr L1 retrotransposon-mediated stable gene silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–40. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Zingler N, Schumann G, Stratling WH. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 represses LINE-1 expression and retrotransposition but not Alu transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4493–501. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Harrison PM, Liu Y, Gerstein M. Millions of years of evolution preserved: a comprehensive catalog of the processed pseudogenes in the human genome. Genome Res. 2003;13:2541–58. doi: 10.1101/gr.1429003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]