Abstract

Background

HIV prevention intervention efficacy is often assessed in the short term. Thus, we conducted a long-term (mean 4.4 years) follow-up of a Woman-Focused HIV intervention for African American crack smokers, for which we had previously observed beneficial short-term gains.

Methods

455 out-of-treatment African American women in central North Carolina participated in a randomized field experiment and were followed up to determine sustainability of intervention effects across three conditions: the Woman-Focused intervention, a modified NIDA intervention, and a delayed treatment control condition. We compared these groups in terms of HIV risk behavior at short-term follow-up (STFU; 3–6 months) and long-term follow-up (LTFU; average 4 years).

Results

The analyses revealed two distinct groups at STFU: women who either eliminated or greatly reduced their risk behaviors (low-risk class) and women who retained high levels of risk across multiple risk domains (high-risk class). At STFU, women in the Woman-Focused intervention were more likely to be in the low HIV-risk group than the women in control conditions, but this effect was not statistically significant at LTFU. However, low-risk participants at STFU were less likely to be retained at LTFU, and this retention rate was lowest among women in the Woman-Focused intervention.

Conclusions

Short-term intervention effects were not observed over four years later, possibly due to differential retention across conditions. The retention of the highest risk women presents an opportunity for extending intervention effects through the booster sessions for those who need it the most.

Keywords: Intervention effects, sustainability, HIV prevention, crack cocaine, African American women

1.0 Introduction

Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, African Americans continue to bear a disproportionate burden of HIV infection in the United States (Hall et al., 2008). The primary mode of HIV transmission for African American women is heterosexual contact, with an estimated three fourths of them being infected via this transmission route (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). One factor that contributes to HIV risk among African-American women is crack cocaine use (Adimora et al., 2006)

HIV risk behaviors among African-American women who use crack cocaine include exchanging sex for money and drugs, unprotected sex, increased number of sex partners, and having sex with high-risk partners, such as injecting drug users (IDUs) (Inciardi et al., 2005; Jones and Oliver, 2007; Wechsberg et al., 2003a). Crack cocaine use is also associated with contextual factors, including lower education and higher rates of unemployment, homelessness, violence, and alcohol use (Tortu et al., 2000; Wechsberg et al., 2003a).

1.1 HIV Prevention Interventions and Effectiveness

Over the past decade, several HIV prevention interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing risk behaviors among African American women (Sterk et al., 2003; Wechsberg et al., 2004; Wingood et al., 2004) and they have been designated “best-evidence” HIV prevention interventions by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Lyles et al., 2007). Several interventions focus on reducing crack cocaine use and sexual risk (Cottler et al., 1998; Inciardi et al., 2005; Sterk et al., 2003; Wechsberg et al., 2004). Two recent meta-analyses of intervention studies—using experimental or quasi-experimental designs that included control groups--to reduce HIV risk among African Americans concluded that behavioral interventions were efficacious in reducing HIV at follow-up periods ranging from 3 to 12 months (Crepaz et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2009).

Many of these interventions were designed to reduce risk in one major area, such as substance abuse, sexual risk, employment, or housing (Albarracin et al., 2005). Research has shown, however, that because of the interconnectedness of the complex issues facing impoverished women who use illicit substances, it is important to address a host of social and health-related concerns simultaneously in order to be successful in any one health area (El-Bassel et al., 2009; Nobles et al., 2009). For example, existing interventions targeting sexual risk may be successful in the short term, but unless the broader concerns are addressed simultaneously, the positive effect is unlikely to be sustained.

1.2 Sustainability of Intervention Effects

Although there has been considerable progress in the development of HIV prevention and sexual risk reduction interventions for women that have been shown to be efficacious (Darbes et al., 2008; Logan et al., 2002). Many studies, however, have only followed participants from 3 to 9 months (Cottler et al., 1998; Dancy et al., 2000; Inciardi et al., 2005; Sterk et al., 2003; Wechsberg et al., 2004), although one study reported follow-up data for up to 2 years (Nyamathi and Stein, 1997). A review of the few studies that have included longer follow-up periods found that even the most successful interventions continue to have significant rates of relapse to high-risk sex behaviors (Wechsberg et al., 2003b).

Even fewer longer term follow-up studies of crack cocaine users have been conducted. Siegal, Li, and Rapp (2002) examined treatment outcomes in a cohort of 229 predominantly male (>99%) veterans who were crack cocaine users over an 18-month period. Among the 419 subjects who entered the study, 229 (54.6%) completed the intake, 6-, 12-, and 18-month interviews. Three trajectories of crack use emerged: (1) individuals who had reported ongoing, stable abstinence from cocaine; (2) individuals who had consistently used cocaine during the period; and (3) individuals who reported cycling between abstinence and use during the follow-up period. The results showed that subjects who were able to sustain abstinence from cocaine also demonstrated improvements in the domains of employment, family, legal, and psychiatric functioning compared with subjects who were not able to sustain abstinence.

A second study by Siegal and colleagues followed crack cocaine users over time to examine predictors of drug abuse treatment entry among an out-of-treatment community sample of 430 crack cocaine users (Falck et al., 2007). The sample comprised 262 males and 168 females—62% of whom are African American—who were tracked and assessed at 6-month intervals for 3 years following baseline. The overall follow-up rate for the 3-year study was 79%. During the observation period, 38% (n=162) of the sample reported that they had entered a drug abuse treatment program. Predictors of entering a drug abuse treatment program included being younger, having more severe legal problems, perceiving a need for treatment, and having prior treatment experience.

Since African American women who use crack are at risk for a multitude of issues, including HIV, studies are needed to identify and understand their risk more clearly. To date, no studies have been conducted overtime with African American women who use crack cocaine who have been in specific woman-focused interventions to determine what occurs.

1.3 The North Carolina Women’s CoOp I and Women’s CoOp II Studies

The North Carolina (NC) Women’s CoOp I (hereafter, Women’s CoOp I) used a 3-group randomized design to compare the effects of a culturally-sensitive gender-specific woman-focused intervention for African-American women who use crack with the effects of an equal dose intervention based on the revised National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)-Standard intervention (Wechsberg et al., 2004) and a delayed-treatment control group. A total of 762 women were enrolled and randomized between 1999 and 2002. Intervention effects were evaluated at follow-up interviews conducted at 3-months and 6-months post-enrollment The woman-focused intervention and the revised NIDA Standard intervention in the Women’s CoOp I study both consisted of two 30 to 40 minute individual sessions and two 60 to 90 minute group sessions. The two individual sessions in both interventions conducted pre- and posttest HIV counseling. The woman-focused intervention individual sessions incorporated personalized feedback and included culturally enriched content that was grounded in empowerment theory specific to African American women crack users and action plans to address the multidimensional risks of drug use, sex-risk behaviors, and contextual goals to address barriers of education, employment, housing, and parenting (Wechsberg et al., 2004). The group sessions were interactive with a gender and culturally specific focus. This intervention was found to be highly efficacious in the short term and was included in a list of “best-evidence” HIV behavioral interventions from 2000–2004 (Lyles et al., 2007). The revised NIDA Standard intervention was similar to the woman-focused intervention in educational content, however, it did not incorporate the gender- or culture-specific empowerment approach to develop one’s life and change social contexts. Moreover, the two group sessions were didactic and presented general information.

The NC Women’s CoOp II (hereafter Women’s CoOp II) was a NIDA competing continuation study of the Women’s CoOp I originally not planned until the original study’s final year. The Women’s CoOp II specific aims were to assess the long-term effects of the Women’s CoOp I interventions and assess the impact of adding booster sessions. Baseline enrollment in the Women’s CoOp II began in 2004, two years after the last follow-ups from Women’s CoOp I (2002) and ended in 2007. Follow-up interviews for the Women’s CoOp II project were completed 6, 12 and 18-months post-enrollment. This paper is limited to an evaluation of the long-term effects of the Women’s CoOp I interventions. See Appendix A1 for a more detailed overview and timeline for these two studies.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Overview

We tested the long-term effects of the Women’s CoOp I intervention and hypothesized that the women who completed the Woman-Focused intervention, which emphasized empowerment (i.e., reducing impaired behavior and taking positive action) by also addressed contextual (e.g., employment, housing) and environmental conditions (e.g., changing and leaving drug-infested neighborhoods and disassociating with drug-using friends), would exhibit more positive change compared with the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) standard intervention and a control condition. We also hypothesized a larger loss to long term follow-up among women assigned to the Woman-Focused intervention who responded well to the intervention.

For the purpose of these analyses, we used the last participant contact in the Women’s Coop I study to define short-term follow-up (STFU). These study participants were then re-contacted between 2 to 8 years later (mean 4.4, median 4.4). For simplicity we will subsequently refer to the time between the last contact in the Women’s CoOp I and re-contact for the Women’s CoOp II as 4 years. The baseline data for the Women’s CoOp II study serve as the long-term follow-up (LTFU) observation.

2.2 Relocation and Enrollment Procedures for the Women’s CoOp II Study

Between March 2004 and March 2007, 60% (455/762) of Women’s CoOp I study participants were relocated and enrolled in the Women’s CoOp II study a mean of 4.4 years (range 2 to 8 years) since their last follow-up. Another 18 women had died prior to being relocated, 2 women were incarcerated over the entire recruitment period for the Women’s CoOp II study, 9 had moved out of the area and could not be contacted, and 8 others who had moved out of the area were interviewed by telephone. The telephone interviews are not included in these analyses. Follow-up procedures are available from the authors.

2.3 Eligibility

Eligibility for the Women’s CoOp II study was restricted to the 762 women who were randomized in the Women’s CoOp I study. Eligibility criteria for participants in the Women’s CoOp I study included: being female, identifying as African American, 18 years of age or older, self-reported unprotected sex during the previous 90 days, and self-reported use of crack cocaine 13 of the past 90 days. Women who reported being enrolled in substance abuse treatment within the past 30 days were excluded. All participants in the Women’s CoOp I study and the Women’s CoOp II study provided informed consent at enrollment in each study. Both studies were approved by RTI’s Office of Research Protection.

2.4 Measures

All interviews in the Women’s CoOp I study were administered via computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) technology and the Women’s CoOp II study interviews were administered using audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) technology. The primary data collection instrument for both studies was a revised version of the Risk Behavior Assessment (RRBA), which included measures to assess psychological distress and violent victimization from various sources (Wechsberg, 1998). The original RBA is a NIDA-developed instrument with adequate reliability and validity with substance abusers (Dowling-Guyer, 1994; Needle et al., 1995; Weatherby et al., 1994). The RBA was revised for the Women’s CoOp I study to focus on women’s issues and contextual issues, such as physical health, sexual and peer relationships, and victimization and violence; and it was found to be reliable for African American women (Wechsberg et al., 2003a).

The sociodemographic characteristics from the RRBA used in this analysis included age, marital status, level of education, employment status, and homelessness. Drug use variables included frequency measures of alcohol and crack use during the past 30 days. Recent sexual behavior variables included engaging in unprotected sex in the past 30 days and sex-trading in the past 30 days. Depression and anxiety were measured with the DATAR depression scale (a 6-item scale) and anxiety scale (a 7-item scale) (Simpson, 1990). Both scales have demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity in a variety of drug-using populations. Because instruments that are reliable in one population may not necessarily be reliable in other populations, we also examined the internal consistency of each DATAR scale in our sample of African American crack-using women. Coefficient alpha was 0.76 for the depression scale, and it was 0.83 for the anxiety scale. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed for the previous 90 days.

2.5 Latent Classes

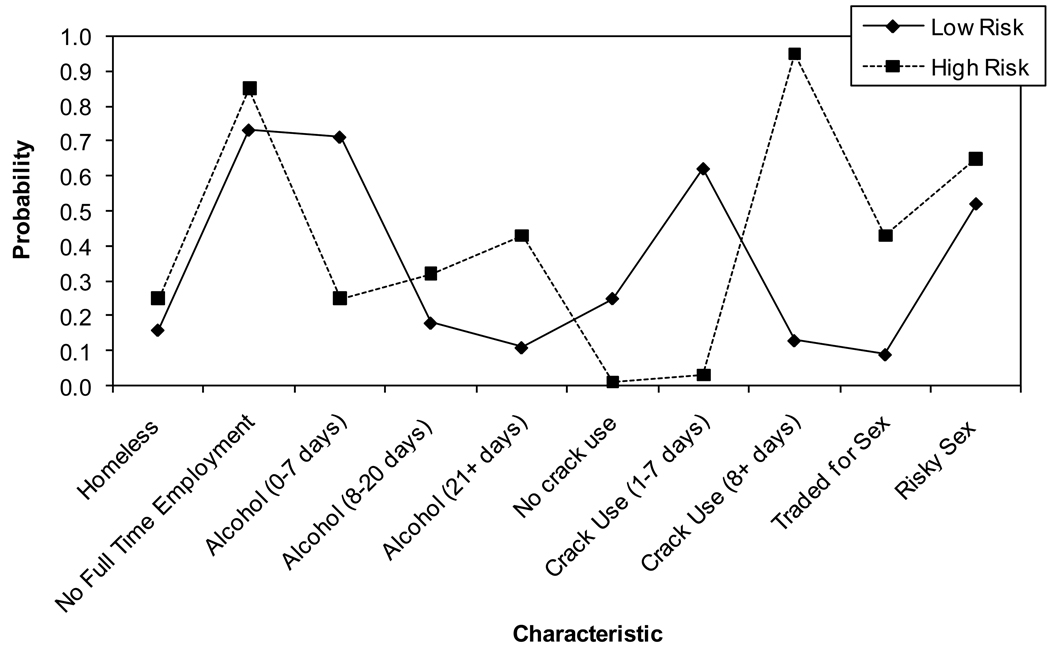

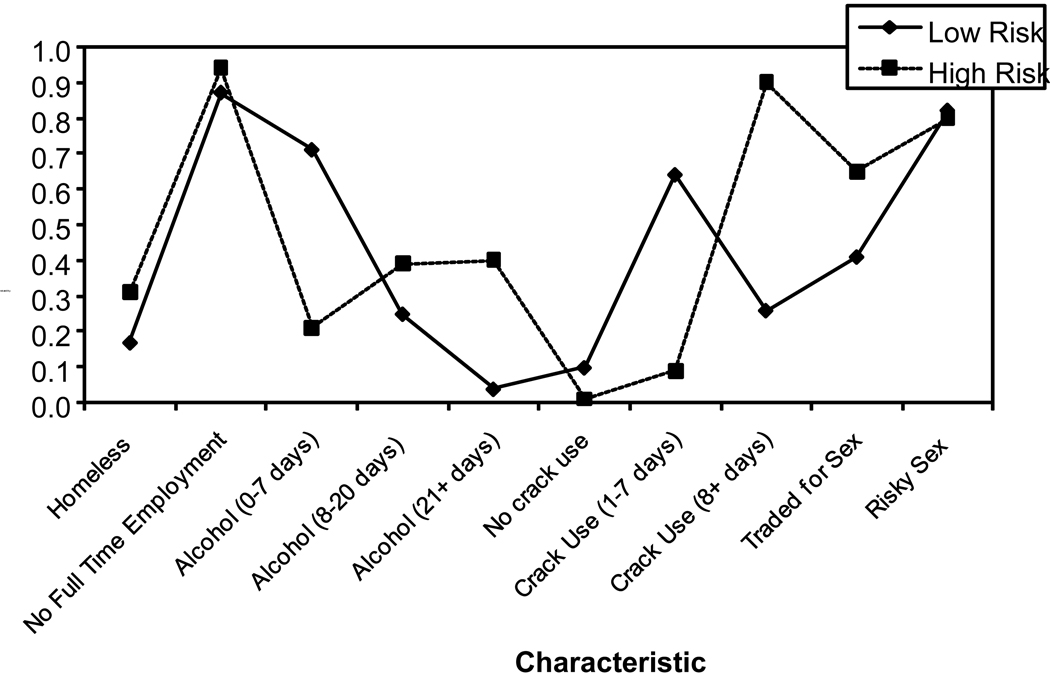

As noted earlier, the intervention targeted multiple risk domains simultaneously, and the primary goal in the present analysis was to examine the longer term sustainability of the intervention effects. Rather than examining each domain separately, we categorized participants into a smaller subset of meaningful patterns of risky behavior. We used latent class analyses (LCA)— an analogue of factor analysis for categorical outcomes (e.g., any risky sex versus no risky sex)—which assumes that the observed correlation among risky behaviors is due to an unobserved latent factor with a finite number of independent classes, or patterns. We estimated two separate LCAs, one for STFU and one for LTFU. We observed that the best fitting model with the most parsimonious number of latent risk behavior classes, was a two class solution. Inspection of the characteristics of the groups at STFUand LTFU reveal similar patterns of responses in that the two classes are primarily distinguished by severity of risk, which we have termed "low risk" and "high risk". Variables used to develop the latent classes include: (1) current homelessness; (2) fulltime employment; (3) 3 categorical variables for frequency of alcohol use in the past 30 days; (4) 3 categorical variables for frequency of crack use in the past 30 days; (5) trading sex for money, drugs or anything else in the past 30 days; and (6) risky sex, which was defined as engaging in unprotected intercourse during the previous 30 days. These resulted in 10 dichotomous variables, which were coded as 0 for no and 1 for yes. For ease of presentation of the results examining the outcomes over time, a description of the methodology used to extract the latent classes is provided in a reviewer’s appendix (Appendix B2). Briefly, the characteristics of the groups at STFU (Figure 1) and LTFU (Figure 2) reveal similar patterns of responses in that the two classes are primarily distinguished by severity of risk (Appendix B2, table).

Figure 1.

Latent Class analysis for Last Contact Outcomes. Risky sex is defined as any unprotected intercourse in the past 30 days. All variables are dichotomous and based on behaviors in the past days.

Figure 2.

Latent Class Analysis for Long-term (Women's CoOp II Intake) Outcomes. *Risky sex is defined as any unprotected intercourse in the past 30 days. All variables are dichotomous and based on behaviors in the past days.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

To compare the sustainability of the Women’s CoOp I intervention over an extended period to the LTFU, it was necessary to establish whether there was differential attrition by study condition.

In this step, we used latent class analysis (ref from previous paper) to create categories of risk outcomes at both STFU and LTFU. These results are contained in Appendix B3. Next, the latent classes were used as predictors of retention in logistic regression models. We also created interaction terms to examine whether the association between outcome patterns at STFU and retention at LTFU differed by treatment assignment. Finally, we sought to characterize the sustainability of the outcome effects over time between STFU and LTFU. We created a series of transition patterns between each of the latent classes at STFU and LTFU. For example, the interventions were deemed as sustaining their effects if the participants remained in their STFU risk pattern at LTFU. Chi-square and t-test comparisons were used to examine these associations. The cutoff for statistical significance was p<0.05.

2.7 Sample for the Women’s CoOp II Study

The analysis is limited to complete data on 446 women who completed the first follow-up interviews for the Women’s CoOp II study. Table 1 presents the demographic information for this sample when enrolled in W1 and during LTFU. Of the 154 participants assigned to the delayed control condition that enrolled in the Women’s CoOp II study, 40% (62/154) actually completed the Standard-R intervention. At enrollment in the Women’s CoOp II study, however, there were no statistically significant (p<0.05) differences between the women assigned to the control condition, and those who completed the Standard intervention and the women who did not complete it.

Table 1.

Women’s 1 and Women’s 2 Baseline Comparisons (N = 452)1

| Variable | Women’s 1 | Women’s 2 | Paired Test Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Less than HS Graduation | 55.3 | 46.2 | |

| HS Graduation or More | 44.7 | 49.8 | |

| Employment (%) | NS | ||

| Employed | 38.5 | 15.0 | |

| Not Employed | 61.3 | 69.9 | |

| Homeless (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 29.6 | 24.8 | |

| No | 69.0 | 74.1 | |

| HIV Infected (% - N = 290) | |||

| Yes | 5.9 | - | |

| No | 94.1 | - | |

| Days Crack Use in Last 30 | 18.2 (9.8) | 13.4 (10.88) | <0.001 |

| Days Alcohol Use in Last 30 | 15.8 (12.1) | 10.9 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| # of Sex Partners in Last 30 Days | 3.6 (10.5) | 2.2 (6.8) | 0.02 |

| Times Used Alcohol During Sex | 4.3 (7.6) | 3.8 (19.4) | NS |

| Times Used Crack During Sex | 6.0 (8.2) | 4.7 (11.3) | 0.03 |

| Unprotected Sex Acts | 9.8 (11.7) | 6.9 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Days in Jail in Last 90 | 1.2 (6.0) | 3.0 (12.0) | 0.006 |

Mean (SD) value format except where labeled with %. Some values may not total to 100% due to missing values.

3. RESULTS

3.1 STFU Predictors of LTFU Retention

Before we can interpret the effects of sustainability of the interventions, it is necessary to establish whether there was differential attrition among conditions. Few of the characteristics measured at SFTU were significantly associated with retention in the study at LTFU, either in the bivariate or multivariate models (Table 2). Participants who had a high-school education at STFU, however, were significantly less likely to be retained at LTFU. While marginally nonsignificant (p=.08), LTFU retention was greater for participants exhibiting high-risk outcomes compared with low-risk outcomes at STFU. Participants in the Woman-Focused intervention condition also had slightly lower rates of retention compared with women in the other two conditions.

Table 2.

Predictors of Retention from Last Contact (STFU) of Women's CoOp I to Long-Term Follow-up (LTFU) of Women's CoOp II

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic at SFTU | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | AOR | 95% CI | P-Value |

| Cluster | ||||||

| Class 1 (LC): Abstain/Low Frequency Behaviors |

ref | ref | ||||

| Class 2 (LC): High Frequency Behaviors |

1.35 | 0.94–1.89 | .083 | 1.25 | 0.88–1.79 | .208 |

| Condition | ||||||

| Control | ref | ref | ||||

| Standard | 1.09 | 0.72–1.65 | .667 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.77 | .585 |

| Women's | 0.73 | 0.49–1.09 | .127 | 0.72 | 0.47–1.10 | .132 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 | ref | ref | ||||

| 30–44 | 1.16 | 0.73–1.84 | .508 | 1.31 | 0.79–2.16 | .274 |

| 45–55 | 1.23 | 0.65–2.34 | .511 | 1.39 | 0.64–2.83 | .361 |

|

High-school grad or higher (vs.

<high school) |

0.65 | 0.49–0.96 | .038 | 0.70 | 0.48–1.01 | .056 |

|

Married or living as married (vs.

single/divorced/other) |

0.85 | 0.52–1.40 | .542 | 0.91 | 0.54–1.55 | .751 |

| Ever tested for HIV (vs. never) | 0.89 | 0.43–1.83 | .764 | 0.84 | 0.40–1.76 | .653 |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| 0–7 | ref | ref | ||||

| 8–13 | 1.15 | 0.70–1.91 | .566 | 1.23 | 0.69–2.19 | .466 |

| 14–21 | 0.91 | 0.54–1.55 | .754 | 0.91 | 0.48–1.72 | .774 |

| 22–28 | 1.43 | 0.58–3.49 | .432 | 1.76 | 0.59–5.19 | .305 |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| 0–7 | ref | ref | ||||

| 8–13 | 0.92 | 0.61–1.40 | .725 | 0.91 | 0.57–1.45 | .707 |

| 14–21 | 1.05 | 0.66–1.67 | .835 | 1.00 | 0.57–1.76 | .982 |

| 22–28 | 1.00 | 0.49–2.04 | .984 | 1.01 | 0.45–2.27 | .976 |

Note: STFU=short-term follow-up; OR=Odds ratio; AOR=Adjusted OR; CI=confidence interval, LC=3 or 6 month follow-up.

Ref levels are: Class 1 (abstain/low frequency), control condition, less than high-school education, single/divorced/other marital status, Age (18–55), depressive symptoms (0–28), and anxiety symptoms (0–28) are scored in original metric.

In analyses not shown, we computed an interaction between STFU outcome risk class and treatment group. The predicted probability of retention was lower in the low-risk outcome class compared with high-risk status across all three intervention conditions. The probability of retention was lowest, however, in the Woman-Focused intervention condition (pr=.55) compared with the control (pr=.62) and the standard (pr=.66) conditions. In comparison, the probability of retention for the high-risk group was .63, .70, and .68 for the Woman-Focused, Standard, and control conditions, respectively.

Taken together, these findings, while nonsignificant, suggest that women exhibiting more positive low-risk outcomes at SFTU, particularly in the Woman-Focused condition, were the group least likely to be retained. Therefore, comparing the effects of the study interventions over time is problematic, as there appear to be differences in rates of attrition across study arms. These rates, however, are all statistically nonsignificant.

3.2 Sustainability of Effects between LTFU and STFU by Condition

Given that we observed a trend toward differential attrition by classes of outcomes between STFU and LTFU, we sought to examine the sustainability of the intervention effects over time for each of the two classes of risk behaviors. An important caveat is that the long-term effects of the interventions should be interpreted in light of the nonrandom attrition discussed above.

For participants with complete data, we examined transitions between STFU and LTFU. Theoretically, we would expect to observe significant movement over time, largely driven by participants in the positive outcome group (i.e., abstain/low frequency users) at STFU moving to a negative outcome group (i.e., high frequency users) at LTFU, indicating that the intervention effects erode over time. Further, the intensity of the Woman-Focused intervention is such that we would expect its effects to be more durable over time compared with the NIDA Standard and control conditions.

Overall, no significant change over time was observed by condition (chi-square 10.49, 6df, p=.105) among participants with complete data (Table 3). Although Table 4 suggests with cautious interpretation, we elect to show effects that might be considered durable, resistant, eroding and a sleeper effect from high to low risk. Averaging over all of the conditions, the majority of participants (62.75%, n=251 of 400) remained in their risk pattern from STFU to LTFU. Among these maintaining their risk pattern, 25% (n=101) maintained positive effects. Of all high-risk participants (n=211) at STFU, 71% (n=150) remained high-risk at LTFU, considered treatment resistant. Conversely, among individuals in the low-risk class at STFU (n=189), approximately 23% (n=88) transitioned to a high-risk class at LTFU. No significant sociodemographic characteristics at STFU predicted transitions in risk.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Transitions between Latent Classes Short-Term Follow-up (Women's CoOp I Last Contact) to Long-Term Follow-Up (Women's CoOp II Baseline)

| No Transition n=101 (25.25%) Class 1: Abstain/Low Frequency User |

No Transition n=150, (37.5%) Class 2: High Frequency User |

Transition n=88 (22%) Class 1≥Class 2 |

Transition n=61 (15.25%) Class 2-≥Class 1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | of Class (%) |

of Characteristic (%) |

of Class (%) |

of Characteristic (%) |

of Class (%) |

of Characteristic (%) |

of Class (%) |

of Characteristic (%) |

| Condition | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| Control | 27.7 | 20.3 | 39.3 | 42.8 | 29.6 | 18.8 | 40.9 | 18.1 |

| Standard | 41.6 | 30.9 | 27.3 | 30.2 | 34.1 | 22.1 | 37.7 | 16.9 |

| Women's | 30.7 | 24.6 | 33.3 | 39.7 | 36.4 | 25.4 | 21.3 | 10.3 |

| Chisq=10.49, 6df, p=.105 | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 6.93 | 12.3 | 16.7 | 43.8 | 14.8 | 22.8 | 19.6 | 21.1 |

| 30–44 | 74.3 | 25.5 | 74.1 | 37.8 | 71.6 | 21.4 | 73.8 | 15.3 |

| 45–55 | 18.8 | 38.8 | 9.3 | 28.6 | 13.6 | 24.5 | 6.6 | 8.2 |

| Chisq=12.08, 6df, p=.060 | ||||||||

|

High-school grad or Higher 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 48.5 | 27.1 | 44.0 | 36.5 | 51.1 | 24.9 | 34.4 | 11.6 |

| No | 51.5 | 23.7 | 56.1 | 38.4 | 48.8 | 19.6 | 65.6 | 18.3 |

| Chisq=4.64, 3df, p=.199 | ||||||||

|

Married or living as

married1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 13.9 | 29.2 | 9.3 | 29.2 | 17.1 | 31.3 | 8.2 | 10.4 |

| No | 86.1 | 24.7 | 90.7 | 38.6 | 82.9 | 20.7 | 91.8 | 15.9 |

| Chisq=4.29, 3df, p=.231 | ||||||||

| Ever tested for HIV 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 90.8 | 23.4 | 94.8 | 37.9 | 92.9 | 23.2 | 94.6 | 15.4 |

| No | 9.2 | 33.3 | 5.2 | 29.2 | 7.1 | 25.0 | 5.5 | 12.5 |

| Chisq=1.54, 3df, p=.674 | ||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms 1 | ||||||||

| 0–7 | 22.8 | 43.4 | 10.0 | 28.3 | 9.1 | 15.1 | 11.5 | 13.2 |

| 8–13 | 47.5 | 23.5 | 54.7 | 40.2 | 50.0 | 21.6 | 49.2 | 14.7 |

| 14–21 | 27.7 | 23.1 | 29.3 | 36.4 | 34.1 | 24.8 | 31.2 | 15.7 |

| 22–28 | 1.9 | 9.1 | 6.0 | 40.9 | 6.8 | 27.3 | 8.2 | 22.7 |

| Chisq=14.22, 9df, p=.114 | ||||||||

| Anxiety Symptoms 1 | ||||||||

| 0–7 | 29.7 | 30.0 | 21.3 | 32.0 | 25.0 | 22.0 | 26.2 | 16.0 |

| 8–13 | 44.6 | 27.3 | 40.7 | 36.9 | 40.9 | 21.8 | 37.7 | 13.9 |

| 14–21 | 19.8 | 18.7 | 28.7 | 40.2 | 29.6 | 24.3 | 29.5 | 16.8 |

| 22–28 | 5.9 | 21.4 | 9.3 | 50.0 | 4.6 | 14.3 | 6.6 | 14.3 |

| Chisq=6.76, 9df, p=.661 | ||||||||

Notes: 1) Baseline values used for last contact outcomes; Women’s CoOp II intake values used for long-term follow-up. N=400

Table 4.

Change in Risk from WI to II by Condition

| Transition | Control | NIDA | Women’s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low➔Low (Durable) |

20.3% | 30.9% | 24.6% |

| High➔High (Resistant) |

42.8% | 30.2% | 39.7% |

| High➔Low (Sleeper) |

18.8% | 22.1% | 25.4% |

| Low➔High (Erosion) |

18.1% | 16.9% | 10.3% |

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the long-term impact of the Women’s CoOp intervention, which has been proven effective in the short-term to reduce a number of social, health, and contextual factors among African American female crack cocaine smokers. The Woman-Focused intervention condition is an intensive brief intervention targeting multi-dimensional risk behaviors as well as promoting the value of disengaging from negative environments that may contribute to relapse or sustain negative behaviors as a set. While we observed significant short-term effects of the intervention compared with a control condition, we did not observe a long-lasting effect after its completion among the study participants who were retained at long term. This is evidenced by the nonsignificant differences in the underlying classifications at LTFU. Moreover, the similarity in sexual risk in both the high and low risk group at four year follow-up illustrates the larger inherent challenge for HIV prevention increasing condom use and decreasing unprotected sex.

The lack of long-term sustainability of the overall intervention effect is disappointing, but it may in part be explained by a trend toward differential retention (p=.08) by study condition after STFU, as a higher proportion of Women’s CoOp participants were lost to LTFU than participants in the other two arms. This is in contrast to other studies, which generally found that individuals with more positive outcomes at STFU are more likely to be retained at LTFU (Simpson, 2004; Stanton and Shadish, 1997; Vaughn et al., 2002).

It is possible that participants in the intervention arm responded successfully to messages about the need to establish new, non-drug–using, social and neighborhood environments. Ultimately, these messages may have led them to move away from the study area (100 radius of the two cities) and thus be lost to retention. Resources did not permit the tracking of participants out of the study area, making it impossible to determine whether differential retention was due to differential relocation of study participants. We surmise, however, that the women who did do well in the Woman-Focused arm of the study want to stay away from drug-infested environments and recast their lives. But not all women are able to leave their everyday environments and the mean and median follow-up was over four years.

Whether individuals change their physical and social environments (e.g., leaving their neighborhoods) may play a key role in stopping crack use (Daniulaityte et al., 2007) and supporting relapse prevention; (Carroll et al., 1991; Gorski, 1990). Specifically, one of the steps to recovery has been hypothesized as “separating from people, places, and things that promote chemical use and establishing a social network that supports recovery” (Gorski, 1990 p. 128). One study among substance-abusing women found that a factor in women’s relapse was the inability to remove substance-abusing individuals from their social network and establish relationships with people who do not use substances (Sun, 2007). Moreover, the type of environmental issues that individuals encounter after treatment, such as housing, income, and employment are also related to substance relapse (Castellani et al., 1997).

As funding becomes scarcer, it may be difficult to measure the long-lasting effects of interventions on the complex social, health, and psychological dimensions necessary when focusing on both HIV and substance abuse among African American women. The science of intervention development and long-term epidemiological evaluation of interventions aimed at reducing risky behaviors among substance-using women needs to be fostered. Crack cocaine still appears to be one of the primary illicit drugs of abuse and it is likely to continue to be the scourge of inner-city neighborhoods. For many of these women with long-term addictions to crack cocaine, they will likely need long-term interventions and treatment to abate this course and its associated risk behaviors. This raises a methodological issue in terms of evaluating the long-term effects of interventions, especially when an intervention encourages changes in surroundings and friends that are likely to make follow-up more difficult. It may be possible to obtain consent at enrollment to use methods similar to those that have been used in natural history studies of opioid users in which interviewers traveled to other states and, in some instances, collected information from collateral sources (e.g., relatives, substance abuse treatment programs, arrest records and other agencies) at long-term follow-up) (Maddux and Desmond, 1981; Nurco et al., 1975). In addition to the methodological issues related to retention in long-term follow-up studies, there is the substantive issue of designing an intervention that would result in changes in behavior that were sustained for at least 2 years and preferably much longer. One possible solution is periodic booster sessions for women who remain in the area and are not institutionalized. For women who are institutionalized (e.g. incarcerated or in residential treatment) it may be useful to incorporate HIV interventions into these settings. For women who improve and move out of the area, booster sessions via the internet may be a possibility. More research is needed to identify intervention strategies for producing sustained effects and assessing their feasibility and efficacy.

Determining long-term intervention effectiveness has far-reaching implications for future applied science, policy, and service provision. A primary aim of our future work is to not only develop stronger linkages to essential wrap-around services that are needed for high-risk women who seek to make lifestyle changes but test even more intensive woman-focused interventions that women in recovery can lead.

There are several important limitations inherent to this study that should be considered when evaluating the results. First, is the issue of differential retention across conditions, which may affect the internal validity of the findings. Although evidence suggests that studies with retention rates below 70% can produce valid findings if dropouts are similar to those retained (Hansten et al., 2000), differential attrition has been shown to threaten the validity of findings (Stanton and Shadish, 1997). As discussed previously, our data show that there was differential retention at LTFU by study condition, which limits straightforward interpretation of the results.

All of the outcomes relied on the use of self-report data, which are subject to biases related to differential recall and social desirability. Participants may have modified their responses based on the belief that it may help or hinder them through the social welfare, health, or criminal justice systems. Although these types of limitations are inherent in most studies in this field of research, we took measures to enhance the validity of our data. These measures included training interviewers in the Women’s CoOp I study to be nonjudgmental and conducting interviews in the Women’s CoOp II study using ACASI technology, which has been shown to mitigate socially desirable responses (Des Jarlais et al., 1999; Metzger et al., 2000). The reliability of self-reported data in this study was enhanced by the use of survey instruments that have demonstrated adequate reliability in previous studies (Dowling-Guyer, 1994; Needle et al., 1995). We also took special care in modifying the instrument for African American women who use crack cocaine.

Another limitation is that our outcome measures, which were based on behavior over the previous 30 days, may not reflect accurately the behaviors of women over the entire follow-up period. However, the reliability of recall of behaviors across a period ranging from 2 to 8 years is likely to be very low. Addiction career studies have been able to overcome this limitation by collecting concurrent collateral information (Maddux and Desmond, 1981). However we did not have access to collateral sources of information. Therefore we chose to use the 30-day timeframe.

In addition, as with most studies of illicit drug users and other hidden populations, no original sampling frame is available, which may limit the external validity of the findings. Participants in the Women’s CoOp I study, however, were recruited using a targeted sampling approach, which has been used in numerous studies to increase representativeness of samples of hidden populations.(Carlson et al., 1994; Watters and Biernacki, 1989).

Despite these limitations, this study is one of the first to report on long-term HIV intervention outcomes in African-American women who use crack cocaine. It is also one of the few long-term follow-up studies of crack users in general. Although many women continued to use crack, drink alcohol and engage in risky sexual behaviors, the frequencies of all of these behaviors decreased significantly between baseline in the Women’s CoOp I and their first interview in Women’s CoOp II. Findings from the Women’s CoOp II study, which has booster sessions and cost effectiveness, may shed some light on the effectiveness of this approach in sustaining behavior change.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material related to this article is available with the full text online version at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

Available as supplementary material with the full text online version of this paper at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.x.xx …

Available as supplementary material with the full text online version of this paper at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.x.xx …

Available as supplementary material with the full text online version of this paper at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.x.xx …

REFERENCES

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2006;41:616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarracin D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho MH. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: A comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:856–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RG, Wang J, Siegal HA, Falck RS, Guo J. An ethnographic approach to targeted sampling: Problems and solutions in AIDS prevention research among injection drug and crack-cocaine users. Human Organization. 1994;53:279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Keller DS. Relapse prevention strategies for the treatment of cocaine abuse. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1991;17:249–265. doi: 10.3109/00952999109027550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani B, Wedgeworth R, Wootton E, Rugle L. A bi-directional theory of addiction: examining coping and the factors related to substance relapse. Addict Behav. 1997;22:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Leukefeld C, Hoffman J, Desmond D, Wechsberg W, Inciardi JA, Compton WM, Ben Abdallah A, Cunningham-Williams R, Woodson S. Effectiveness of HIV risk reduction initiatives among out-of-treatment non-injection drug users. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:279–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs ED, Mizuno Y, Kay LS, Jones P, McCree DH, O'Leary A. The Efficacy of HIV/STI Behavioral Interventions for African American Females in the United States: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancy BL, Marcantonio R, Norr K. The long-term effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention for low-income African American women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12:113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Carlson RG, Siegal HA. "Heavy users," "controlled users," and "quitters": understanding patterns of crack use among women in a midwestern city. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:129–152. doi: 10.1080/10826080601174678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22:1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Milliken J, Turner CF, Miller H, Gribble J, Shi Q, Hagan H, Friedman SR. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behaviour for HIV among injecting drug users: a quasi-randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling-Guyer S. Reliability of Drug Users. Assessment. 1994;1:383–392. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Caldeira NA, Ruglass LM, Gilbert L. Addressing the unique needs of African American women in HIV prevention. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:996–1001. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck RS, Wang J, Carlson RG. Crack cocaine trajectories among users in a midwestern American city. Addiction. 2007;102:1421–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski TT. The Cenaps model of relapse prevention: basic principles and procedures. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1990;22:125–133. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1990.10472538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Karon J, Brookmeyer R, Kaplan EH, McKenna MT, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansten ML, Downey L, Rosengren DB, Donovan DM. Relationship between follow-up rates and treatment outcomes in substance abuse research: more is better but when is "enough" enough? Addiction. 2000;95:1403–1416. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.959140310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Weaver JC. The effect of serostatus on HIV risk behaviour change among women sex workers in Miami, Florida. AIDS Care. 2005;17 Suppl 1:S88–S101. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009;51:492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R, Oliver M. Young urban women's patterns of unprotected sex with men engaging in HIV risk behaviors. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:812–821. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: Social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:851–885. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, Rama SM, Thadiparthi S, DeLuca JB, Mullins MM. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddux JF, Desmond DP. Careers of opioid users. New York: Praeger; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner C, Navaline H, Valenti F, Holte S, Gross M, Sheon A, Miller H, Cooley P, Seage GR., 3rd Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, Chitwood D, Brown B, Cesari H, Booth R, Williams ML, Watters J, Andersen M. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nobles WW, Goddard LL, Gilbert DJ. Culturecology, women, and African-centered HIV prevention. Journal of Black Psychology. 2009;35:228–246. [Google Scholar]

- Nurco DN, Bonito AJ, Lerner M, Balter MB. Studying Addicts over Time: Methodology and Preliminary Findings. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1975;2:183–196. doi: 10.3109/00952997509002733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi AM, Stein JA. Assessing the impact of HIV risk reduction counseling in impoverished African American women: a structural equations approach. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9:253–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal HA, Li L, Rapp RC. Abstinence trajectories among treated crack cocaine users. Addict Behav. 2002;27:437–449. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. Drug Abuse Treatment for AIDS Risk Reduction (DATAR): forms manual. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for drug treatment process and outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:99–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, Shadish WR. Outcome, attrition, and family-couples treatment for drug abuse: a meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:170–191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW. Effectiveness of a risk reduction intervention among African American women who use crack cocaine. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:15–32. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.15.23843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun AP. Relapse among substance-abusing women: components and processes. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:1–21. doi: 10.1080/10826080601094082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortu S, Beardsley M, Deren S, Williams M, McCoy HV, Stark M, Estrada A, Goldstein M. HIV infection and patterns of risk among women drug injectors and crack users in low and high sero-prevalence sites. AIDS Care. 2000;12:65–76. doi: 10.1080/09540120047486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn T, Sarrazin MV, Saleh SS, Huber DL, Hall JA. Participation and retention in drug abuse treatment services research. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby NL, Needle R, Cesari H, Booth R, McCoy CB, Watters JK, Williams M, Chitwood DD. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1994;17:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM. Revised Risk Behavior Assessment, Part I and Part II. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WK, Zule W, Hall G, Middlesteadt R, Edwards J. Violence, homelessness, and HIV risk among crack-using African-American women. Subst Use Misuse. 2003a;38:669–700. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WK, Zule WA, Bobashev G. Efficacy of a woman-focused intervention to reduce HIV risk and increase self-sufficiency among African American crack abusers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1165–1173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Zule WA, Lam WK, Hall GC, Ellerson RM. African-American woman-focused HIV intervention outcomes and the need to evaluate long-term effectiveness; NIDA/CAMCODA Working Meeting; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, NIDA; 2003b. pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, Lang DL, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Hook EW, 3rd, Saag M. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: The WiLLOW Program. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2004;37 Suppl 2:S58–S67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.