Abstract

Background

Stress is thought to contribute to both initiation and relapse to drug abuse. However, the mechanisms by which stress influences drug use are unclear. Interestingly, responses to acute administration of stimulant drugs resemble certain neuronal and hormonal responses to acute stress, and there is accumulating evidence that individual variation in the positive reinforcing or euphorigenic effects of a drug are related to individual differences in responsivity to acute stress.

Methods

In this study we evaluated relationships between physiological and subjective responses to a stressful task and to an oral dose of d-amphetamine in healthy adult volunteers (N=34). Individuals participated in four experimental sessions; two behavioral sessions involving a stressful task (i.e. public speech) or a non-stressful control task, and two drug sessions involving oral administration of d-amphetamine (20mg) or a placebo. The dependent measures included salivary cortisol, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and subjective ratings of mood.

Results

As expected, both stress and d-amphetamine increased cortisol, heart rate and blood pressure. Stress increased negative mood, whereas d-amphetamine induced prototypic stimulant effects and increased ratings of drug liking. Analyses revealed that increased negative mood states after stress were correlated with positive mood after amphetamine. In addition, increased cortisol after stress was correlated with positive mood responses to amphetamine. Finally, there were modest positive correlations between cortisol and heart rate increases after stress and mean arterial pressure after amphetamine.

Conclusions

These results support and extend previous observations that responses to acute stress are correlated with certain subjective, hormonal and cardiovascular effects of a stimulant drug.

Keywords: Amphetamine, Trier Social Stress Test, Acute stress, Individual differences, subjective effects, cortisol

1.Introduction

Major theories of addiction postulate that stress plays an important role in the motivation to use psychoactive substances (Shiffman 1982; Marlatt and Gordon 1985; Wills and Shiffman 1985; Koob and Le Moal 1997). However, the relationships between stress and drug use are complex and vary with the particular phase of drug-taking i.e., acquisition, maintenance or relapse (Uhart and Wand, 2009). Early studies suggested that some individuals use drugs to reduce negative affect related to stress and affective disorders (Conger 1956; Sher and Levenson, 1982; Khantzian 1985; Marlatt and Gordon,1985; Wills and Shiffman, 1985). However, more recent studies have shown that certain drugs activate the same brain reward circuits as acute stressors (Piazza and LeMoal, 1998), and there is evidence of cross-sensitization between acute stress and psychostimulants or opiates during the acquisition of drug taking behavior (Piazza et al.,1990; Piazza et al., 1991; Goeders and Guerrin, 1994; Shaham and Stewart, 1994; Haney et al., 1995; Tidey and Miczek, 1997; Kosten et al., 2003). Thus, it has been proposed that individual differences in sensitivity to acute stress may underlie some of the individual differences in vulnerability to addiction.

Animal studies have demonstrated interactions between the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis, the mesolimbic dopamine system and drug reward. Glucocorticoids stimulate mesolimbic dopamine transmission (Piazza et al., 1996a, b) and regulate sensitivity to the behavioral effects and self-administration of psychostimulants, opiates and alcohol in laboratory animals (Marinelli et al., 1994; Fahlke et al., 1994, 1995; Goeders and Guerrin, 1996a; Mantsch et al., 1998). There are also demonstrable links between stress responsivity, the mesolimbic dopaminergic system and sensitivity to drug reward in animals; stress increases mesolimbic dopamine activity (Piazza and Le Moal, 1998; Rouge-Pont et al., 1995, 1998; Tidey and Miczek, 1997) and stress-induced increases in cortisol predict the degree of sensitization to cocaine's reinforcing properties (Goeders et al., 1996b; Goeders 2002). Similarly, sensitivity to an acute stressor is also related to sensitivity to the rewarding effects of stimulant drugs in humans. First, de Wit and colleagues (2007) reported that negative mood after an acute social stressor, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST; Kirschbaum and Hellhammer, 1993) was correlated with positive subjective responses to an oral dose of d-amphetamine (20 mg); individuals who reported the highest ratings of anxiety after stress also reported the highest ratings on a measure of friendliness after amphetamine. Second, using positron emission tomography (PET), Wand et al. (2007) reported that cortisol responses to the TSST were positively correlated with striatal dopamine release after intravenous amphetamine (0.3 mg/kg). They also found that greater cortisol response to the TSST was associated with greater increases in positive mood i.e., visual analogue ratings of high, good, liking and rush after amphetamine. Together, these studies indicate relationships between the physiological and subjective responses to an acute stressor and amphetamine.

The purpose of the present study was to replicate and extend previous findings indicating relationships between both physiological (stress hormone, cardiovascular) and subjective mood responses to the TSST and responses to oral d-amphetamine (0 or 20 mg). The current study was similar in design to our own previous study (de Wit et al., 2007), but differed from the Wand et al (2007) study in that we administered amphetamine orally under double blind conditions and we measured additional cardiovascular responses (i.e. heart rate and blood pressure). Based on our and Wand et al's (2007) findings, we hypothesized that sensitivity to stress, as indexed by physiological (cortisol, cardiovascular indices) and subjective mood responses, would be positively correlated with subjective positive mood responses to d-amphetamine.

2.METHODOLOGY

2.1 Participants

This study was part of a larger longitudinal study in which responses to stress were evaluated in relation to potential smoking trajectories among young college (age 18–25) occasional smokers. In the larger ongoing study (N=56), participants' smoking and other substance use behaviors are examined through 12 months of follow-up after participation in the two stress responsivity sessions (stress and control sessions). Volunteers were given the option to participate in an additional two drug administration sessions (amphetamine and placebo), 34 of the 56 volunteers chose to participate in the additional sessions. There were no significant differences in background characteristics between individuals who chose to participate in the additional two sessions and those who did not. Subjects were recruited from the University of Chicago and surrounding areas via posters, newspaper ads, and online postings. All candidates completed an initial phone interview followed by an in-person interview with a physical examination and an electrocardiogram. Subjects were eligible if they were 18–25 years old, had smoked at least one cigarette in the past month but not more than 20 cigarettes per week, and had a body mass index between 19–29 kg/m2. During the screening session, candidates completed a questionnaire regarding current and lifetime substance and alcohol use disorders based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Non-Patient Edition (SCID; First et al., 1995). Candidates were excluded if they had a serious medical condition or were taking any prescription medications, or had a current or past year Major Axis I psychiatric disorder (APA, 1994), or lifetime Substance Dependence (including Nicotine). They were also excluded if they had a positive urine toxicology screen for cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, methamphetamine, tetrahydrocannabinol, benzodiazapines, barbiturates, oxycodone or methadone. In order to minimize the potential confound of sex hormones upon stress responses (Childs et al., In Press; Kajante and Phillips, 2006), women were tested only during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, i.e., 2–10 days after the self-reported first day of menstruation (see White et al., 2002). Women were not allowed to participate if they were taking oral contraceptives because of potential effects of estrogen on HPA axis hormone responses (Kirschbaum et al., 1999). All subjects had to have at least a high school education and be fluent in the English language. They signed a consent form informing them of study risk and benefits. The study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Design

Subjects participated in four experimental sessions at the Human Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory at the University of Chicago. The first two sessions lasted 90 minutes each and involved participation in a stressful task, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST, Kirschbaum and Hellhammer, 1993) or a non-stressful control task, in randomized order. The sessions always began at 1pm and took place at least 72 h apart. The latter two sessions lasted 4 ½ h each and involved administration of 0 or 20mg d-amphetamine (Mallinkrodt, Inc NY; administered in opaque gelatin capsules with dextrose filler), in random order under double-blind conditions. Drug administration sessions always began at 12:00pm and took place at least 48 h apart. The behavioral sessions i.e., stress/no stress, always took place before the drug administration sessions, as the latter two sessions were optional. All study sessions took place in comfortably furnished rooms in the laboratory. Participants could watch television/movies or read magazines during intervals when measures were not being obtained. At the end of the study, subjects were fully debriefed about the aims of the study, the drugs they received and were paid for their participation.

2.3 Procedure

Subjects were instructed to abstain from alcohol for 24 h and from cigarette smoking or eating for 2 h before the sessions. They were allowed to consume their usual amounts of caffeine in order to avoid any effects of withdrawal (see Table 1). Upon arrival for each session, participants provided a urine sample for drug and pregnancy testing, and breath samples were obtained to detect recent alcohol use and smoking. In addition, research assistants interviewed subjects upon arrival to confirm compliance with drug and eating restrictions. Individuals were then allowed to rest for 15 min before baseline measures were obtained.

Table 1.

Demographic and substance use characteristics for study participants. Data are presented as N, Mean±SD or percent of participants.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Male/female (N) | 21/13 |

| Age (years) | 20.8±2.33 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.0±2.33 |

| Race | |

| European-American | 73% |

| African-American | 15% |

| Other | 12% |

| Education | |

| Full-time college student | 82% |

| Bachelor's Degree completed | 18% |

| Current Drug Use | |

| Caffeine (cups/week) | 2.9±3.50 |

| Cigarettes (cigarettes/week) | 6.0±1.17 |

| Alcohol (drinks/week) | 7.2 ±7.00 |

| Marijuana (occasions/week) | 0.8±1.75 |

| Lifetime Drug Use (% ever used) | |

| Marijuana | 88% |

| Stimulants | 29% |

| Tranquilizers | 6% |

| Hallucinogens | 35% |

| Opiates | 18% |

| Inhalants | 9% |

2.4 Stress and No Stress Sessions

After the initial 15 min rest period, baseline subjective ratings and physiological measures were obtained. Then, the research assistant read instructions to the participant for either the stress or no stress condition. For the stress condition, participants were told that they had ten minutes to prepare for a five-minute mock job interview speech, follow by a five-minute mental arithmetic, both performed in front of two interviewers and a video camera. Ten minutes after the instructions, subjects were escorted to a separate examination room where they performed the TSST. For the non-stressful task, individuals were told that they had ten minutes to think about their favorite book, movie, or television program to describe to the research assistant for five minutes. They then played a card task (Solitaire) for five minutes. There was no video camera or observers present during this task. Immediately after the procedures, participants returned to the testing room to provide physiological measures (at 0, 10, 20, 30, 60 and 90 min after the tasks). The subjective (i.e. mood) questionnaires were completed at 0, 10, 30, 60 and 90 minutes.

2.5 Drug Administration Sessions

At 12:30 pm, after baseline measure had been obtained, individuals consumed a capsule containing either 0 or 20mg d-amphetamine with a glass of water. Physiological and subjective measures were obtained at 30, and 60, 90, 120, 180 and 240 min after capsule administration.

2.6 Subjective Measures

The Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI; Haertzen et al., 1983) is a 49-item questionnaire comprised of 5 scales corresponding to typical effects of psychoactive drugs. Because we were interested in the prototypic stimulant effects of d-amphetamine, we analyzed only the Stimulation (ARCI A - Amphetamine scale), which consists of 11 items. Some examples of ARCI A items include “My memory seems sharper to me than usual” and “I feel very patient.”

The Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al., 1971) consists of 72 adjectives commonly used to describe momentary mood states. Participants rate, from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), the extent to which each adjective describes how they feel at that moment. To assess responses to stress we focused on two subscales, Anger (grouchy, spiteful, annoyed, bitter, ready to fight) and Anxiety subscales (panicky, restless, nervous). To assess responses to amphetamine we examined the Elation scale (satisfied, refreshed, pleased, elated).

The Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ; Johanson and Uhlenhuth 1980) consists of four questions each rated on a 100- mm line (from “not at all” to “very much”) concerning current drug effects. In order to capture pleasurable aspect of amphetamine, we examined the “Liking” item, “Do you like the effects you are feeling now?”

2.7 Physiological Measures

Saliva samples were collected using Salivette® cotton wads (Sarstedt Inc. Newton, NC). The GCRC Core Laboratory at The University of Chicago determined levels of cortisol in saliva (Salimetrics LLC, sensitivity=0.003ug/dL). Heart rate was measured continuously using a Polar® S610 monitor (Polar Electro Inc., Lake Success, NY) and blood pressure was measured at repeated intervals using a monitor (DINAMAP® ProCare 100 Vital Signs Monitor, GE Healthcare, Tampa, FL). Measurements of systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP) were used to calculate mean arterial pressure (MAP) using the formula MAP= DBP +1/3(SBP-DBP).

2.8 Data analysis

We first evaluated baseline differences between stress and no stress conditions and separately between amphetamine and placebo conditions using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). To assess the main effect of stress, a two way ANOVA was performed using condition (stress, no stress) and time (five time points for physiological measures and four time points for subjective measures) after stress or no stress procedure minus pre-procedure baseline scores as within - subject factors. To assess the main effect of amphetamine, a two way ANOVA was performed using dose (0 or 20 mg of drug) and time (five time points after capsule ingestion minus predrug baseline scores) as within-subject factors for the dependent measure. Possible confounding variables (gender and session order) were assessed by performing separate two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Since heart rate was measured continuously (every minute for the stress and no stress sessions and every five minutes for the amphetamine and placebo sessions) we subtracted the baseline scores from the highest reading 10 minutes post stress or no stress or at any point post capsule administration. Peak change from baseline scores were entered into two separate ANOVA models: one model comparing the effects of stress in relation to no stress and the second model comparing the effects of amphetamine and placebo. A p value of <0.05 was set as a threshold for statistical significance.

Second, we used Pearson Product Moment partial correlations to assess relationships between measures of stress and amphetamine responses. We derived a single value of stress response for each variable by first subtracting each post stress and post no stress time point from its appropriate baseline (pre-stress or pre-no stress time point). We then calculated area under the curve (AUC) with respect to increase (Pruessner et al., 2003) for both stress and no stress conditions. Finally, we subtracted AUC for the no stress condition from the AUC for the stress condition. We derived a single value of amphetamine responses by first subtracting each post amphetamine and post placebo time point from its appropriate baseline (pre-amphetamine or pre-placebo time point). We then calculated area under the curve (AUC) with respect to increase (Pruessner et al., 2003) for both amphetamine and placebo conditions and finally subtracted AUC for the placebo condition from the AUC for the amphetamine condition. Since a single outlier can drive significant effect of correlations, we excluded any values of summary measures (AUC Stress – AUC No Stress and AUC Amphetamine-AUC Placebo) if their z score was lower than −3.29 or higher than 3.29. We controlled for sex in the Pearson Product Moment partial correlations based on the work by Munro et al (2006) which showed that men have markedly greater dopamine release following amphetamine administration than women in the striatum. The correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni method) was set at 0.0017.

3.Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Most participants were European-American (73%) full-time students (82%, Table 1). Men and women did not differ on any of the demographic characteristics. The mean age of participants was 20.8±2.33 (mean±SD) years, and they reported smoking approximately 6 cigarettes (range: 1–20) and consuming 7 alcoholic drinks per week (range: 0–12). Individual responses to the TSST and amphetamine were not related to baseline levels of weekly alcohol drinking or cigarette smoking.

3.2 Effects of Acute Stress

We did not observe any session order effects on any of the measures used to evaluate acute stress. Men and women did not differ in their responses to stress. Baseline differences were observed only for MAP (p<.001) and were not due to session order effects. Table 2 provides baseline and AUC values for all variables measured for the stress and no stress procedures.

Table 2.

Pre and post session data for variables included in the study. Values represent Mean ±SEM

| Variable | Baseline | AUC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | No Stress | Amphetamine | Placebo | Stress | No Stress | Amphetamine | Placebo | |

| Anxiety (POMS) | .49±.05 | .53±.05 | .42±.05 | .53±.07 | 4.45±.75 | −1.26±.56 | 2.97±1.53 | −2.15±1.12 |

| Anger (POMS) | .20±.04 | .21±.04 | .19±.05 | .19±.05 | 1.20±.77 | −.132±.44 | −1.32±1.20 | −1.30±.09 |

| Elation (POMS) | .88±.11 | .90±.11 | .65±.08 | .53±.07 | −2.03 ±.74 | −.254±.97 | 0.20±1.22 | −2.29±.95 |

| Cortisol | .14±.02 | .14±.019 | .19±.02 | .16±.02 | .14±.14 | −.32±.12 | .73±.46 | −1.30±.27 |

| MAP | 85.08±1.46 | 89.01±1.37 | 85.07±1.52 | 87.04±1.90 | 26.96±12.55 | −31.68±.7.60 | 335.58±27.30 | −2.09±.27.53 |

Note: Ratings of ARCI A and Drug Liking Effects are not shown here because they were only obtained on drug sessions. However, the difference between amphetamine and placebo on these measures was highly significant (p<.001).

In comparison to the non-stressful control task, the TSST significantly increased the following (Main effect of stress): POMS Anxiety F(1,32)=7.80, p<0.01; POMS Anger F(1, 32)=5.34, p<0.05; salivary cortisol F(1,32)=9.62, p<0.01; heart rate F(1,26)=14.84, p<0.001 and mean arterial pressure F(1,33)=18.47, p<0.001.

3.3 Effects of Amphetamine

There were no baseline differences between placebo and amphetamine sessions for the assessed variables. We did not observe any session order effects or gender differences in our evaluation of amphetamine responses. See Table 2 for baseline and AUC values for all variables measured for amphetamine and placebo administration.

Relative to placebo, amphetamine significantly increased scores for the following variables (Main effect of drug): ARCI A F(1,28)=16.71, p<0.001; ratings of drug liking F(1,28)=21.62, p<0.001; cortisol levels F(1,30)=16.23, p<0.001; heart rate F(1,27)=20.26, p<0.001 and mean arterial pressure F(1,33)=132.08, p<0.001. The rating of POMS Elation was not statistically significant F(1,31)=2.51, p<0.1.

3.4 Relationships between stress and amphetamine responses

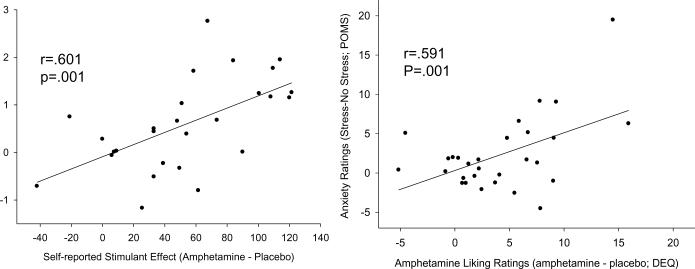

Correlation analyses revealed significant relationships between subjective responses to stress and subjective responses to amphetamine. Subjects who rated anxiety high also rated the stimulant (ARCI A), liking (DEQ like) (Figure 1) and elating (POMS Elation) properties of drug highly (p <.01, p<.001 and p<.05 respectively). See table 3 for detailed results of correlation analyses. The highest correlation between subjective ratings of stress and amphetamine was the rating of anxiety after stress and rating of DEQ liking after amphetamine (p<0.001). This relationship was significant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Figure 1.

Relationship between cortisol responses to acute stress and subjective stimulation after amphetamine (left panel), and ratings of anxiety following stress and DEQ “Liking” following amphetamine (right panel) in the same individuals (N=34). Data points indicate net cortisol response to stress (AUC during stress session minus AUC during control session) and net subjective responses to amphetamine (AUC during amphetamine session minus AUC during placebo session).

Table 3.

Summary of Correlations Between Responses to Stress and Responses to Amphetamine. The top row of each label represents the Pearson Product Moment correlation coefficient and the bottom row represents the statistical value p.

| RESPONSES TO STRESS | RESPONSES TO AMPHETAMINE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine (ARCI) | Drug Liking (DEQ) | Elation (POMS) | Cortisol | Mean Arterial Pressure | Heart Rate | |

| Anxiety (POMS) | .493 | .591 | .412 | .258 | .258 | −.167 |

| .009** | .001*** | .026* | .161 | .161 | .416 | |

| Anger (POMS) | .403 | .273 | .084 | .099 | −.029 | .062 |

| .037* | .161 | .667 | .615 | .878 | .765 | |

| Cortisol | .601 | .172 | .211 | .214 | .483 | .198 |

| .001*** | .392 | .271 | .264 | .005** | .333 | |

| Mean Arterial Pressure | −.118 | −.264 | −.152 | .138 | .053 | −.487 |

| .559 | .175 | .423 | .469 | .771 | .010* | |

| Heart Rate | .230 | .045 | −.028 | .195 | .423 | −.077 |

| .303 | .838 | .894 | .372 | .032* | .733 | |

p≤.05

≤.01

≤.001

There were also significant relationships between physiological responses to stress and subjective and physiological measures after amphetamine. Stress-induced cortisol increase was positively correlated to both ARCI A scores (p<.001) (Figure 2) and MAP (p<.01) after amphetamine. Stress-induced increase in MAP was negatively correlated with heart rate (p<.01) after amphetamine, and heart rate after stress was positively correlated (p<.05) with MAP after amphetamine. The correlation between stress-induced cortisol and rating of ARCI A following amphetamine administration remained statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

In this study, we found that negative mood states induced by stress were positively related to stimulant and euphoric mood states after d-amphetamine. In addition, the increase in cortisol after stress was correlated with positive mood states after d-amphetamine (20 mg). Our results support recent findings of relationships between stress reactivity and the euphorigenic or positive mood effects of amphetamine in humans (deWit et al., 2007; Wand et al., 2007). They are also consistent with the findings of animal studies which have demonstrated links between stress-induced increases in cortisol and subsequent sensitization to the reinforcing effects of cocaine (Goeders and Guerrin 1996b; Goeders 2002). Positive subjective responses to drugs are believed to one of the main reasons why people use psychoactive substances and may predict individual differences in susceptibility to drug abuse (Haertzen et al., 1983; Jasinski 1991; Davidson et al., 1993; Davidson and Schenk, 1994; Lyons et al., 1997; Fergusson et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2005). Thus, together the findings suggest that individual differences in stress responsivity may be related to differences in vulnerability to addiction.

There is evidence showing that acute stress and acute drug administration activate the same brain systems (Piazza and Le Moal 1998) and studies show cross-sensitization between acute stress and psychoactive substances (Piazza et al., 1990, 1991; Goeders and Guerrin, 1994; Shaham and Stewart, 1994; Haney et al., 1995; Tidey and Miczek, 1997; Kosten et al., 2003). Thus, during the early stages of drug-taking, activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal by stress could sensitize the mesolimbic dopamine system to the rewarding effects of drugs. Alternatively, these findings in healthy non-drug using volunteers suggest that there may be pre-existing differences in the mesolimbic dopamine system or other neural processes which alter responses to both stress and amphetamine. This should be the aim of future investigations.

The results of the present study are consistent with our earlier finding (de Wit et al., 2007) that subjective responses to stress and amphetamine are related. In both studies, subjects who experienced more negative mood states following stress procedure also experienced higher stimulant and reinforcing effects of amphetamine. Although we were not able to correct for multiple comparisons in our earlier study, here we focused on subjective and physiological responses unique to stress and amphetamine. We found a correlation between the rating of anxiety following stress and the rating of drug liking following amphetamine administration, as well as a correlation between stress-induced cortisol release and rating of effects of amphetamine (ARCI A). These remained significant following correction for multiple comparisons. Although in our earlier study we found that cortisol responses to stress and amphetamine were related, cortisol responses to the two interventions were not related here, for reasons that are unclear. Nevertheless, it is notable that consistent relationships between cortisol responsivity to stress and mood responses to amphetamine were observed in the present study and in the study by Wand and colleagues (2007) despite several methodological differences between the experiments (e.g., route of drug administration (oral vs. intravenous), study design (double-blind vs. single-blind), session order (random vs. fixed), and comparison control conditions (placebo-controlled vs. not placebo-controlled). The consistency of findings between studies suggests that the relationships between subjective and physiological responsivity to stress and sensitivity to the positive mood effects of amphetamine in healthy young adults are particularly robust. We observed additional physiological relationships between stress and amphetamine, namely that stress-induced cortisol and heart rate increases were positively correlated to increase in MAP following amphetamine administration. The particular mechanisms of the common physiological responses between stress and amphetamine need to be evaluated should future studies replicate these findings.

The study had several limitations. First, the study was conducted with a small, homogeneous population. The results should be extended to heavier cigarette smokers, and to more heterogeneous populations, including older individuals, and people with more extensive drug use histories and psychiatric symptomatology. This study utilized control conditions for both stress (i.e., no stress) and amphetamine (i.e., placebo). This led to a methodological issue in the data analysis, necessitating the calculation of an AUC for an event that does not show a rise (i.e. placebo and no stress conditions). However, the inclusion of a no-stress and placebo control conditions was critically important to the design because it permits within-subject comparison. Finally, the four sessions were not fully counterbalanced. To our knowledge, session order did not strongly affect our results.

In summary, we found that cortisol and negative mood induced by stress were positively associated with positive ratings of mood after d-amphetamine. Our findings replicate and extend previous evidence of relationships between reactivity to stress and subjective responses to amphetamine. Future studies should explore the mechanisms that link responses to acute stress and those to psychostimulant drugs, and whether either of these is related to future recreational or problem drug-taking.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision DSM-IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, Dlugos A, de Wit H. Cardiovascular, hormonal and emotional responses to the TSST in relation to sex and menstrual cycle phase. Psychophysiology. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00961.x. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Alcoholism: Theory, problem and challenge. II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson ES, Schenk S. Variability in subjective responses to marijuana: Initial experiences of college students. Addict Behav. 1994;19:531–538. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson ES, Finch JF, Schenk S. Variability in subjective responses to cocaine: Initial experiences of college students. Addict Behav. 1993;18:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90062-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Vicini L, Childs E, Sayla MA, Terner J. Does stress reactivity or response to amphetamine predict smoking progression in young adults? A preliminary study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlke C, Hard E, Eriksson CJ, Engel JA, Hansen S. Amphetamine-induced hyperactivity: Differences between rats with high or low preference for alcohol. Alcohol. 1995;12:363–367. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)00019-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlke C, Hard E, Thomasson R, Engel JA, Hansen S. Metyrapone-induced suppression of corticosterone synthesis reduces ethanol consumption in high-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:977–981. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT, Madden PA. Early reactions to cannabis predict later dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders (SCID-III) J Pers Disord. 1995;9:83–91. 1. Description. [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE. Stress and cocaine addiction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:785–789. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Guerrin GF. Effects of surgical and pharmacological adrenalectomy on the initiation and maintenance of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res. 1996a;722:145–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Guerrin GF. Role of corticosterone in intravenous cocaine self administration in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1996b;64:337–348. doi: 10.1159/000127137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Guerrin GF. Non-contingent electric foot-shock facilitates the acquisition of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114:63–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02245445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lyons MJ, Tsuang M, True WR, Bucholz KK. Subjective reactions to cocaine and marijuana are associated with abuse and dependence. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1574–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haertzen CA, Kocher TR, Miyasato K. Reinforcements from the first drug experience can predict later drug habits and/or addiction: Results with coffee, cigarettes, alcohol, barbiturates, minor and major tranquilizers, stimulants, marijuana, hallucinogens, heroin, opiates and cocaine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1983;11:147–165. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(83)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Maccari S, Le Moal M, Simon H, Piazza PV. Social stress increases the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in male and female rats. Brain Res. 1995;698:46–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00788-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinksi DR. History of abuse liability testing in humans. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1559–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Uhlenhuth EH. Drug preference and mood in humans: Diazepam. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980;71:269–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00433061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajantie E, Phillips DI. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:151–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosom Medicine. 1999;6:154–162. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. The 'trier social stress test' - A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: Hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997;278(5335):52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Gottschalk PC, Tucker K, Rinder CS, Dey HM, Rinder HM. Aspirin or amiloride for cerebral perfusion defects in cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons MJ, Toomey R, Meyer JM, Green AI, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True WR, Tsuang MT. How do genes influence marijuana use? The role of subjective effects. Addiction. 1997;92:409–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantsch JR, Saphier D, Goeders NE. Corticosterone facilitates the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats: Opposite effects of the type II glucocorticoid receptor agonist dexamethasone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli M, Piazza PV, Deroche V, Maccari S, Le Moal M, Simon H. Corticosterone circadian secretion differentially facilitates dopamine-mediated psychomotor effect of cocaine and morphine. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2724–2731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02724.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G, Gordon J. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. Profile of mood states. Educational and Industrial Testing Service; San Diego: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Munro CA, McCaul ME, Wong DF, Oswaldm LM, Zhou Y, Brasic J, Kuwabara H, Kumar A, Alexander M, Ye W, Wand G>S. Sex differences in striatal dopamine release in healthy adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:966–974. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Marinelli M, Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, Maccari S, Simon H, Le Moal M. Stress, glucocoritcoids, and mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons: A pathophysiological chain determining vulnerability to psychostimulant abuse. NIDA Res Monogr. 1996a;163:277–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, Maccari S, Simon H, le Moal M. Glucocorticoids have state-dependent stimulant effects on the mesencephalic dopaminergic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996b;93:8716–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Maccari S, Deminiere JM, le Moal M, Mormede P, Simon H. Corticosterone levels determine individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;163:277–299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, le Moal M, Simon H. Stress and pharmacologically induced behavioral sensitization increases vulnerability to acquisition of amphetamine self-administration. Brain Res. 1990;514:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90431-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner CJ, Clemens Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2003;28:916–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. Individual differences in stress induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens are influenced by corticosterone. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3903–3907. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouge-Pont F, Marinelli M, Le Moal M, Simon H, Piazza PV. Stress-induced sensitization and glucocorticoids. II. sensitization of the increase in extracellular dopamine induced by cocaine depends on stress-induced corticosterone secretion. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7189–7195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07189.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Stewart J. Exposure to mild stress enhances the reinforcing efficacy of intravenous heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1994;114:523–527. doi: 10.1007/BF02249346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Levenson RW. Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress response dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol. 1982;91:350–367. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.5.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: A situational analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, Miczek KA. Acquisition of cocaine self-administration after social stress: Role of accumbens dopamine. Psychopharmacology. 1997;130:203–212. doi: 10.1007/s002130050230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhart M, Wand GS. Stress, alcohol and drug interaction: An update of human research. Addict Biol. 2009;14:43–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand GS, Oswald LM, McCaul ME, Wong DF, Johnson E, Zhou Y, Kuwabara H, Kumar A. Association of amphetamine-induced striatal dopamine release of cortisol responses to psychological stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2310–2320. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TL, Justice AJ, de Wit H. Differential subjective effects of D-amphetamine by gender, hormone levels and menstrual cycle phase. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills T, Shiffman S. Coping and substance abuse: A conceptual framework. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]