Abstract

c-AMP-dependent protein kinases (PKAs) are the main transducers of cAMP signaling in eukaryotic cells. Recently we reported the identification and characterization of a PKA catalytic subunit (SmPKA-C) in Schistosoma mansoni that is required for adult schistosome viability in vitro. To gain further insights into the role of SmPKA-C in biological processes during the schistosome life cycle, we undertook a quantitative analysis of SmPKA-C mRNA expression in different life cycle stages. Our data shows that SmPKA-C mRNA expression is developmentally regulated, with the highest levels of expression in cercariae and adult female worms. To evaluate the biological role of SmPKA-C in these developmental stages, cercariae and adult worms were treated with various concentrations of PKA inhibitors. Treatment of cercariae with H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide resulted in loss of viability suggesting that, as in adults, PKA is an essential enzyme activity in this infectious larval stage. In adult worms, in vitro exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide resulted in inhibition of egg production in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, using a murine model of schistosome infection where S. mansoni fecundity is impaired, we show that reduced rates of egg production in vivo correlate with significant reductions in SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity. Finally, restoration of parasite egg production in vivo also resulted in normalization of SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity. Taken together, our data suggest that PKA signaling is required for cercarial viability and may play a specific role in the reproductive activity of adult worms.

Keywords: Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosome, Blood fluke, Protein kinase A, Parasite development, Reproductive biology

1. Introduction

Schistosomiasis, a disease caused by parasitic blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma, affects over 200 million people in tropical and sub-tropical regions and ranks second only to malaria as a parasitic cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Engels et al., 2002). Schistosome developmental biology is complex, involving distinct life cycle stages that are adapted for survival within and transmission between the intermediate molluscan and definitive mammalian hosts (Basch, 1991). Chemotherapy depends solely on the anthelminthic praziquantel (PZQ), which is effective against the adult worms of all the medically important schistosome species (Cioli and Pica-Mattoccia, 2003). However, it is unrealistic to expect that reliance on PZQ for all treatment and control of schistosomiasis will be sustainable in the long-term. PZQ-tolerant strains of schistosomes have been reared in the laboratory and there is evidence of decreased PZQ sensitivity in patients following short- and long-term PZQ treatment regimens (Fallon and Doenhoff, 1994; Ismail et al., 1999; Melman et al., 2009). Thus the potential for the development of PZQ resistance is real and major research efforts now need to be focused on identifying new chemotherapeutic targets in schistosomes (Caffrey, 2007).

Protein kinases are signal-transducing enzymes that could represent novel chemotherapeutic targets in schistosomes and other eukaryotic pathogens (Doerig, 2004; Dissous et al., 2007). In particular, cAMP-dependent protein kinases (PKAs) are the major mediators of cAMP signaling in eukaryotes and play a central role in biological processes as diverse as gene expression, apoptosis, tissue differentiation and cellular proliferation (Taylor et al., 1990), through the phosphorylation of protein substrates at serine/threonine residues (Taylor et al., 2005). In its inactive state, PKA exists as an inactive tetramer consisting of two identical regulatory (PKA-R) subunits bound to two identical catalytic (PKA-C) subunits. Mammalian genomes contain as many as three pka-c genes and four pka-r genes, the products of which combine in different combinations to produce holoenzymes that serve different functions (Skalhegg and Tasken, 1997). Because the unregulated activity of PKA in mammalian cells has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several types of cancer (Cho-Chung et al., 1995), the development of PKA inhibitors has been pursued as a potential treatment for these diseases (Cho-Chung and Nesterova, 2005; Taylor et al., 2008). Furthermore, PKA has been shown through chemical inhibition to be an essential signaling component in the life cycles of a number of eukaryotic pathogens, including Plasmodium falciparum (Syin et al., 2001), Leishmania major (Siman-Tov et al., 1996) and Giardia lambia (Abel et al., 2001) suggesting that PKA inhibitors may also have anti-parasitic applications.

Although PKAs represent potentially attractive new targets for the treatment of parasitic diseases, relatively little is known about the role and significance of these kinases in the biology of schistosomes. Previous studies on the role of PKA in S. mansoni demonstrated an important role for cAMP and PKA in miracidial locomotion and transformation to the mother sporocyst (Kawamoto et al., 1989; Matsuyama et al., 2004). Furthermore, we recently showed that a PKA-C subunit (SmPKA-C; GenBank Accession No. GQ168377) is expressed in active form in adult S. mansoni and is required for parasite viability, at least in vitro (Swierczewski and Davies, 2009). However, the role of SmPKA-C during infection of and development within the mammalian host has not been examined. To gain further insights into the role of SmPKA-C in mammalian parasitism, we first undertook a quantitative analysis of SmPKA-C mRNA expression in the different schistosome life cycle stages. We then examined the effect of PKA inhibitors on the stages in which SmPKA-C mRNA is most abundant, the cercaria and adult female. In the case of adult schistosomes, we also examined SmPKA mRNA levels and PKA activity under in vivo conditions where adult reproductive fitness is compromised. Our data suggest that SmPKA-C is required for invasion of the mammalian host and for the subsequent reproductive activity of adult worms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Parasite materials

Biomphalaria glabrata snails infected with the Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI)/Puerto Rican strain of S. mansoni were obtained from Dr. Fred Lewis (Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD, USA). Cercariae were collected by exposing infected snails to light for 2 h in 50 mL of ultra-filtered water. Schistosomula were prepared by the mechanical transformation method according to published protocols (Lewis, 2001). Adult Schistosoma mansoni were collected by portal perfusion from 6 week-infected wild type and recombination activating gene-1 deficient (RAG-1−/−) C57BL/6 mice that were infected with 150 cercariae using the tail immersion method (Lewis, 2001). Schistosoma mansoni miracidia and sporocysts were kindly provided by Dr. Nithya Raghavan (Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD, USA). Schistosoma mansoni egg cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. Conor R. Caffrey (Sandler Center for Basic Research in Parasitic Diseases, San Francisco, CA, USA). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Uniformed Services University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR (qPCR) of SmPKA-C transcript

Total RNA was extracted from miracidia, sporocysts, cercariae, schistosomula and adult female and male worms using the RNAzol B Method (IsoTex Diagnostics, Inc.). One μg RNA from each life cycle stage was used to synthesize cDNA using the iScript™ Select cDNA Synthesis Kit and an oligo (dT)20 primer (Bio-Rad). cDNA was used as templates for PCR amplification using the SYBR Green fluorescence master mix and the M.J. Research Chromo4 PCR cycler (Bio-Rad). The 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) was used to quantify relative SmPKA-C expression (GenBank Accession No. GQ168377), using the S. mansoni alpha tubulin (GenBank Accession No. S79195) cDNA as an internal control. Primers used to amplify a ∼100 bp fragment (nucleotide positions 4 - 110) of the SmPKA-C cDNA were: forward 5′– GGTAATGCACAAGCTGCTAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGTTCTGAGCAGGCTTCTCCC -3′. Primers used to amplify a ∼100 bp fragment of the alpha tubulin (GenBank Accession No. S79195) cDNA (nucleotide positions 1711 - 1824) were: forward 5′ - GGTTGACAACGAGGCCATTTATG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGTGTAGGTTGGACGCTCTATATCT-3′. SmPKA-C expression levels in the various life cycle stages were then expressed as fold change relative to the expression level in adult male worms. All assays were performed in triplicate and data are representative of three independent experiments.

2.3. Detection of PKA enzymatic activity in cercariae and adult worms

Freshly isolated adult worms from 6 week-infected C57BL/6 mice were transferred immediately to Petri dishes containing DMEM. Adult worms were kept in DMEM at room temperature for 2 h in order for pairs to separate. Cercariae were collected in ultra-filtered water and placed on ice for 1 h, spun at 75 g for 10 min and the resulting pellet was washed with cold PBS three times. Adult male, female and cercarial protein lysates were prepared by homogenization in cell extraction buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma) and insoluble material removed by centrifugation, as described previously (Swierczewski and Davies, 2009). Protein concentrations were determined using the Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay and adjusted to a final concentration of 0.2 μg/μL with additional extraction buffer. In some experiments, triplicate groups of freshly isolated adult worm pairs (six pairs per group) were incubated for 2 h at 37ºC in 24-well tissue culture plates containing DMEM and 100 μM forskolin or DMSO alone, prior to preparation of protein lysates. PKA activity was measured using the Omnia® Lysate Assay for PKA kit (Biosource) on a Spectramax M2 microplate fluorometer (Molecular Devices) as described previously (Swierczewski and Davies, 2009). Briefly, a master mix containing ATP, a specific PKA peptide substrate, DTT, ultra-pure water and a non-PKA inhibitor cocktail in kinase reaction buffer was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. One μg total protein (equivalent to 5 μL protein lysate) was added to 45 μL of the master mix in opaque 96-well assay plates. Kinase reactions containing 2 ng recombinant human PKA-Cα catalytic subunit (GenBank Accession No. NP 002721.1) (Invitrogen) were used as positive controls. Accumulation of phosphorylated substrate was monitored during a 1 h incubation at 30°C by recording fluorescent emissions every 30 s in relative fluorescent units (RFUs) at a wavelength of 485 nm upon excitation at 360 nm. PKA activity was plotted using GraphPad Prism software version 4 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Symbols at each time point represent the means of three biological replicates and all experiments were performed twice.

2.4. PKA-C inhibitor assays

Newly released cercariae were collected in ultra-filtered water and counted. Effects of PKA inhibition on cercariae were assessed using the PKA-C inhibitors H-89 or PKI 14-22 at the following concentrations: 100, 50, 10 and 1 μM. H-89 and PKI 14-22 amide were purchased from Invitrogen and both were dissolved in water. Approximately 20 cercariae (two biological replicates of 20 cercariae for each concentration) were placed in 500 μL of ultra-filtered water and appropriate concentration of inhibitor in the wells of 24-well tissue culture plates, incubated at room temperature and observed every hour for a period of 3 h. Cercariae were considered to be dead when all evidence of motility had ceased. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using GraphPad Prism software. For assays with adult S. mansoni, freshly isolated worms were treated with PKI 14-22 amide or H-89 at the following concentrations: PKI 14-22 amide: 50, 25, 10 and 1 μM; H-89: 1 μM. H-89 was dissolved in DMSO and PKI 14-22 amide was dissolved in water. Individual adult worm pairs (six pairs per concentration) were placed in the wells of 24-well tissue culture plates containing 1 mL total of DMEM (with 10% FBS and 5% penicillin/streptomycin) and an appropriate concentration of inhibitor. Equal concentrations of appropriate vehicle alone were added to the wells containing control worms. The maximum concentration of DMSO was less than 1% and had no visible effect on control worms. Medium containing inhibitor or vehicle was replaced every 24 h. Worms were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and observed every 24 h for egg production for a period of 6 days. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

2.5. In vivo restoration of schistosome fecundity in RAG-1−/− mice

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli K12 strain) was purchased from InvivoGen and dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 20 μg/100 μL. Two groups of RAG-1−/− mice and one group of wild type C57BL/6 mice were infected with S. mansoni. One group of RAG-1−/− mice was injected i.p. twice each week for 6 weeks with 20 μg of LPS, while the other group of RAG-/- mice received injections of PBS. Adult worms were isolated from infected mice at 6 weeks p.i.. To quantify egg production, livers of infected mice were homogenized in 0.05% trypsin in PBS (50 mL), eggs were counted under a dissecting microscope and total liver eggs were normalized relative to the number of worm pairs obtained from each mouse. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

2.6. Statistical analyses

The statistical significance of differences between treatment groups in PKA activity assays was calculated using one-way ANOVA of repeated measures. The statistical significance of differences between Kaplan-Meier survival curves was calculated using the logrank test. Student's t test was used to test the significance of differences in SmPKA-C mRNA detected by quantitative PCR and to compare numbers of eggs/pair produced in controls and worms treated with PKA inhibitors in vitro. Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by Dunns' multiple comparison tests were used to determine the significance of SmPKA-C mRNA levels and egg production in the LPS treatment experiments. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism software version 4.0 was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Differential regulation of SmPKA-C expression in larval stages of S. mansoni

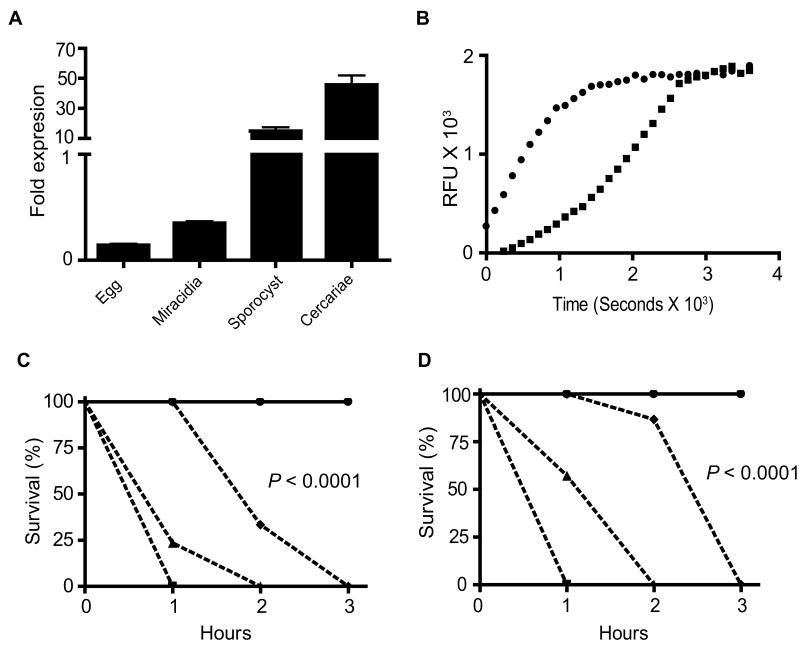

We previously showed that SmPKA-C mRNA is detectable in all S. mansoni life cycle stages (Swierczewski and Davies, 2009), suggesting that some level of SmPKA-C expression may be required throughout the parasite life cycle. To determine whether SmPKA-C expression is differentially regulated during the schistosome life cycle, quantitative PCR was used to investigate the relative abundance of SmPKA-C mRNA in different life cycle stages. In the extra-mammalian stages of the life cycle, SmPKA-C mRNA was expressed at the highest levels in sporocysts and cercariae, with levels at least five-fold higher in cercariae compared with sporocysts (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Schistosoma mansoni protein kinase A catalytic subunit (SmPKA-C) mRNA expression and PKA activity in the larval stages of S. mansoni. A) Relative SmPKA-C mRNA levels in S. mansoni larval stages as determined by quantitative PCR. Data were normalized to the levels detected in a standard preparation of adult male S. mansoni RNA. B) Detection of PKA activity in lysate of S. mansoni cercariae using a fluorescence-based kinase assay. ◆, Cercarial lysate, ●, recombinant human PKA-Cα. C and D) Survival of S. mansoni cercariae in the presence of PKA-C inhibitors. Cercariae in groups of 20 were maintained in water containing varying concentrations of H-89 (C) or PKI 14-22 amide (D). Survival in the presence of each inhibitor was plotted against time. Inhibitor concentrations are as follows: 0 and 1 μM (●); 10 μM (◆); 50 μM (▲); 100 μM (■). Data are representative of two independent experiments. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

To determine whether SmPKA-C expression correlated with levels of PKA activity, a PKA activity assay was conducted on extracts of cercariae using a fluorescent peptide substrate-based assay. Consistent with the relative abundance of SmPKA-C mRNA in cercariae, PKA activity was readily detectable in cercarial protein lysate, with fluorescent reaction product accumulating to similar levels seen with control recombinant human PKA- Cα (Fig. 1B).

3.2. PKA-C activity is required for cercarial viability

A previous study showed that when miracidia were treated with the PKA-C inhibitors H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide, these inhibitors impaired miracidial locomotion in a dose-dependent manner (Matsuyama et al., 2004). To determine the effect of PKA inhibition on cercariae, cercariae were treated with H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide at similar concentrations to those used by Matsuyama et al. (2004) and observed for 3 h for any phenotypic changes. Treating cercariae with H-89 at 100 μM resulted in 100% mortality within 1 h (Fig. 1C). Incubation of cercariae with H-89 at 50 μM resulted in 75% mortality within 1 h and 100% mortality by 2 h (Fig. 1C). Cercariae treated with H-89 at 10 μM resulted in 75% mortality by 2 h and 100% mortality at 3 h (Fig. 1C). One μM concentration of H-89 did not produce mortality in treated cercariae but cercarial motility was severely decreased compared with the controls (data not shown). Treating cercariae with PKI 14-22 amide at 100 μM resulted in 100% mortality within 1 h (Fig. 1D). Incubation of cercariae with PKI 14-22 amide at 50 μM resulted in 50% mortality within 1 h and 100% mortality by 2 h (Fig. 1D). Cercariae treated with PKI 14-22 amide at 10 μM resulted in 20% mortality by 2 h and 100% mortality at 3 h (Fig. 1D). As with H-89, 1 μM concentration of PKI 14-22 amide did not produce mortality in treated cercariae but the same motility-impaired phenotype was observed in the treated cercariae (data not shown).

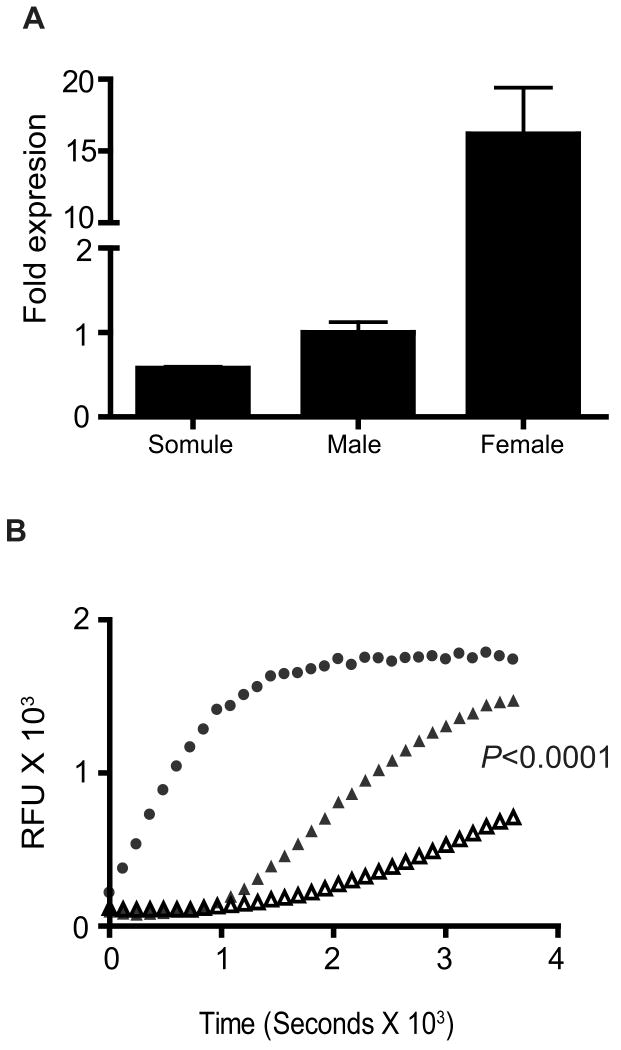

3.3. Differential regulation of SmPKA-C expression and PKA activity in the intramammalian stages of S. mansoni

In the intra-mammalian stages, SmPKA-C mRNA was expressed at the highest levels in adult females, where levels were almost 20-fold higher compared with adult males and newly transformed schistosomula (Fig. 2A). However, measurement of PKA activity in male and female protein extracts revealed there was relatively more PKA activity per microgram of protein in males than in females (Fig. 2B; P < 0.0001), suggesting there is tighter translational and/or post-translational control of baseline PKA activity in females compared with males.

Fig. 2.

Schistosoma mansoni protein kinase A catalytic subunit (SmPKA-C) mRNA expression and PKA activity in the intra-mammalian stages of S. mansoni. A) Relative SmPKA-C mRNA levels in adult male and female S. mansoni worms and schistosomula as determined by quantitative PCR. Data were normalized to the levels detected in a standard preparation of adult male S. mansoni RNA. B) Detection of PKA activity in lysates of adult male and female S. mansoni worms using a fluorescence-based kinase assay. ●, recombinant human PKA-Cα, ▲, male lysate, △, female lysate. Data are representative of two independent experiments. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

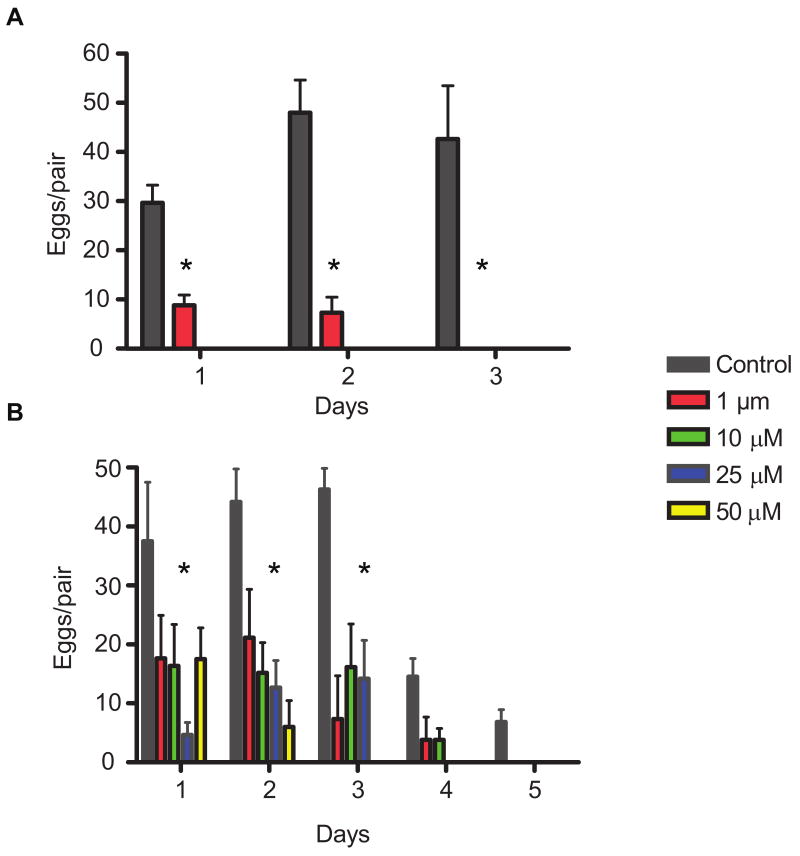

3.3. PKA-C activity is required for S. mansoni egg production in vitro

We previously showed that suppression of PKA-C activity using chemical inhibitors or RNA interference (RNAi) of SmPKA-C was lethal for adult S. mansoni worms in vitro (Swierczewski and Davies, 2009). To gain insights into the biological roles PKA-C plays in adult worms, we treated freshly isolated adults with a range of sub-lethal concentrations of H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide and observed them in vitro for 5 days. All worms remained alive at all of the inhibitor concentrations tested for the duration of the 5 day observation period. However, adult pairs treated with as little as 1 μM of H-89 produced significantly fewer eggs on days 1 and 2 compared with the controls (P < 0.0001) and stopped producing eggs entirely by day 3 (Fig. 3A). Higher concentrations of H-89 caused an immediate cessation of all egg production (Fig. 3A). Similarly, all concentrations of PKI 14-22 amide tested caused an immediate and significant reduction in egg production by day 1 (Fig. 3B). Adult worm pairs treated with 25 and 50 μM of PKI 14-22 amide stopped producing eggs altogether on days 4 and 3, respectively (Fig. 3B). Worm pairs treated with concentrations of 1 and 10 μM PKI 14-22 amide stopped producing eggs by day 5 (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that PKA may play a specific role in parasite egg production.

Fig. 3.

Effects of sub-lethal PKA inhibition on egg production by Schistosoma mansoni worm pairs in vitro. Adult S. mansoni worm pairs were maintained in medium containing varying concentrations of H-89 (A) or PKI 14-22 amide (B). Eggs produced per pair in the presence of each inhibitor were plotted against time. Treatment and control groups containing six worm pairs each were used for each inhibitor concentration. *, P < 0.05 relative to control. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

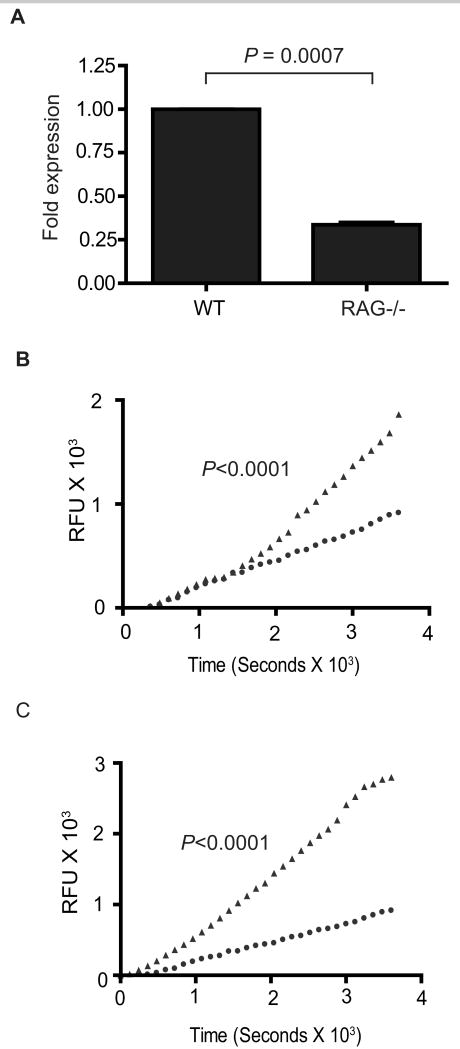

3.4. SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity in adult S. mansoni correlate with reproductive activity in vivo

We have previously shown that the normal development and reproductive activity of Schistosoma worms are positively influenced by immune signals and that parasite development and reproduction are compromised in immunodeficient mice, such as RAG-1-/- mice, that lack an adaptive immune system (Davies et al., 2001; Lamb et al., 2007). To further investigate the potential role of SmPKA-C in S. mansoni reproduction in vivo, we measured PKA activity and SmPKA-C mRNA expression in adult S. mansoni from infected RAG-1-/- mice which are reproductively mature but produce fewer eggs than worms of the same age from infected wild type mice (Davies et al., 2001). As shown in Fig. 4A, SmPKA-C mRNA expression in worms from RAG-1-/- mice (P = 0.0007) was decreased to approximately 30% of the levels detected in the worms from wild type mice. Furthermore, baseline PKA activity was significantly decreased (P < 0.0001) in adult S. mansoni from RAG-1-/- mice compared with adult worms from wild type mice (Fig. 4B). To test whether adult S. mansoni from RAG-1-/- mice possess additional inducible PKA activity, worms from RAG-1-/- mice were exposed to 100 μM of the adenylyl cyclase agonist forskolin for 2 h prior to measurement of PKA activity. PKA activity increased significantly after forskolin treatment (P < 0.0001) compared with untreated worms from RAG-1-/- mice (Fig. 4C), and reached levels comparable to those seen in untreated worms from wild type mice (Fig. 4B). Thus, worms from RAG-1-/- mice express lower levels of SmPKA-C mRNA and have lower baseline PKA activity immediately ex vivo but possess additional PKA activity that can be induced by raising intracellular cAMP concentrations.

Fig. 4.

Schistosoma mansoni protein kinase A catalytic subunit (SmPKA-C) mRNA expression and PKA activity in S. mansoni from RAG-1-/- mice. A) Relative SmPKA-C mRNA levels in adult S. mansoni worms from wild type (WT) and RAG-1-/- mice, as determined by quantitative PCR. B) PKA activity in adult S. mansoni from wild type (WT) and RAG-1-/- mice. ▲, Wild type mice; ●, RAG-1-/- mice. C) PKA activity in adult S. mansoni from RAG-/- mice after treatment with forskolin for 2 h. ▲, forskolin-treated worms; ●, DMSO control-treated worms. Data are representative of three independent experiments. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

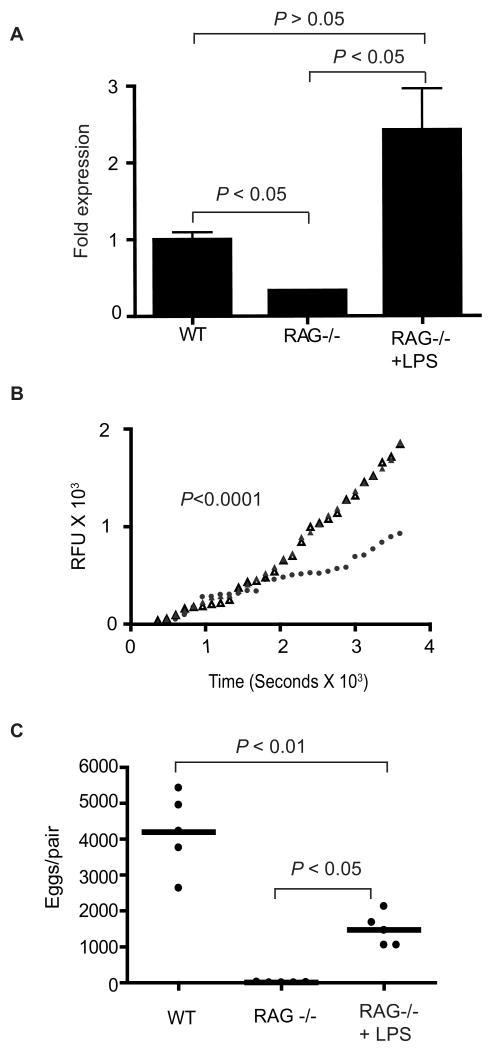

3.5. In vivo restoration of egg production also restores SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity

In separate studies (Lamb et al., unpublished data), we have shown that induction of innate immune responses in RAG-1-/- mice restores reproductive activity in S. mansoni. Therefore, we hypothesized that if SmPKA-C is involved in parasite egg production, SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity in worms from RAG-1-/- mice would also be restored by immune response induction. To test this hypothesis, we treated S. mansoni-infected RAG-1-/- mice with 20 μg E. coli LPS twice weekly for six weeks and quantified SmPKA-C mRNA and PKA activity in the isolated worms. SmPKA-C mRNA in worms from the LPS treatment group was significantly increased (P < 0.05) compared to worms from the control treatment group (Fig. 5A) and was no longer significantly different from the levels found in worms from wild type mice. Furthermore, the PKA activity in worms from the LPS-treated RAG-1-/- mice was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) when compared to PBS-treated control RAG-1-/- mice, and reached levels comparable to these found in worms from wild type mice (Fig. 5B). Consistent with previous results, (Lamb et al., unpublished data), egg production was also significantly restored by LPS treatment (P < 0.05) compared with the control RAG-1-/- mice (Fig. 5C), although restoration was not complete as egg production was still reduced compared with that observed in wild type mice (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Restoration of Schistosoma mansoni protein kinase A catalytic subunit (SmPKA-C) mRNA expression, PKA activity and egg production in RAG-1-/- mice. To restore parasite egg production in vivo, RAG-1-/- mice were infected with S. mansoni and injected i.p. twice each week with 20 μg of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 6 weeks, while infected control RAG-1-/- mice received injections of PBS. Parasites were then isolated for analysis at 6 weeks p.i.. A) Relative SmPKA-C mRNA levels in adult S. mansoni worms from wild type (WT), control RAG-1-/- and LPS-treated RAG-1-/- mice as determined by quantitative PCR. Data were normalized to the levels of SmPKA-C mRNA detected in adult S. mansoni from WT mice. B) PKA activity in S. mansoni from WT, control RAG-1-/- and LPS-treated RAG-1-/- mice. ▲, WT mice; ●, control RAG-1-/- mice; Δ, LPS-treated RAG-1-/- mice. C) Number of eggs per schistosome pair deposited in the livers of WT, PBS-treated control RAG-1-/- and LPS-treated RAG-1-/- mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

4. Discussion

In this study, our aim was to further define the biological role of SmPKA-C in the S. mansoni life cycle, focusing particularly on the adult male and female worms. We showed in a previous report that SmPKA-C is an essential gene in adult worms, at least in vitro, and could therefore represent an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment and control of schistosomiasis (Swierczewski and Davies, 2009). In this study, we wished to explore the role of SmPKA-C in greater detail to understand which aspects of parasite biology would be most affected by targeting SmPKA-C. Here, we show that SmPKA-C expression is developmentally regulated with cercariae and adult females expressing the highest levels of SmPKA-C transcript, suggesting a significant role for SmPKA-C in these life cycle stages.

Consistent with an important role for SmPKA-C in cercariae, PKA activity was readily detectable in cercariae and cercariae were susceptible to the PKA-C inhibitors H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide, as was shown for miracidia (Matsuyama et al., 2004). However, compared with where PKA-C inhibition merely disrupted miracidial locomotion, PKA-C inhibition produced lethality in cercariae within 1 h of exposure. These results suggest that in contrast to miracidia, PKA is required for viability of the cercarial transmission stage. Consistent with this differential requirement for PKA-C activity in cercariae, SmPKA-C mRNA was also expressed at relatively high levels in daughter sporocysts but not in eggs (Fig. 1A). We were unable to compare PKA activity in miracidia and cercariae as we could not obtain sufficient quantities of miracidial protein lysate, but our hypothesis is that PKA activity is higher in cercariae than in miracidia.

Interestingly, SmPKA-C mRNA levels decreased dramatically in schistosomula (Fig. 2A) compared with cercariae (Fig. 1A), suggesting a lack of requirement for PKA immediately after infection of the mammalian host. A parallel situation may occur during the miracidium-mother sporocyst transformation, as stimulation of PKA activity in miracidia inhibited the transformation to mother sporocysts (Kawamoto et al., 1989). However, as infection of the mammalian host proceeds, SmPKA-C again appears to assume an important role as SmPKA-C mRNA was highly expressed in adult female worms. Indeed, SmPKA-C mRNA was relatively more abundant in female worms than males, despite higher levels of PKA activity in males, suggesting a greater degree of translational and/or post-translational regulation of PKA activity in females. In addition to host signals (Davies et al., 2001), female schistosomes require the presence of male schistosomes for normal physical growth and development, sexual maturation and reproductive capacity (Popiel and Basch, 1984). The necessity to transduce these various signals may account for the greater regulation of PKA activity in females compared with males. Indeed, males and females were allowed to separate for up to 2 h in vitro, in order to measure sex-specific activity, and PKA activity in females may therefore have decreased without the constant stimulation from the male worms.

The high expression levels of SmPKA-C mRNA in female worms are suggestive of a role for SmPKA-C in female-specific processes such as egg production. Consistent with a role for signal transduction pathways in egg production (LoVerde et al., 2009), a previous study showed that tyrosine kinase signaling may be important for schistosome fecundity, by demonstrating that exposure to the broad spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitor herbimycin A significantly inhibited parasite egg production in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (Knobloch et al., 2006). Furthermore, PKA in the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has been shown to play a critical role in egg production, as RNAi knock-down of C. elegans kin-1 (a PKA-C subunit homologue) expression resulted in abnormal egg laying (Rual et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2008). Likewise in S. mansoni, PKA inhibition in adult worm pairs with sub-lethal concentrations of H-89 or PKI 14-22 amide significantly decreased egg production in vitro in a dose-dependent manner. These data suggest that at least in vitro, PKA signaling is important for maintaining normal reproduction.

To determine whether a role for PKA signaling in egg production could be substantiated in vivo, SmPKA-C expression and PKA activity were assessed in adult S. mansoni from infected RAG-1-/- mice, as parasite egg production is significantly impaired in these animals (Davies et al., 2001; Davies and McKerrow, 2003; Lamb et al., 2007). Consistent with this hypothesis, PKA activity and SmPKA-C mRNA are significantly decreased in adult worms from RAG-1-/- mice compared with adult worms from wild type mice at the same stage of infection. Furthermore, while baseline PKA activity is decreased in worms from RAG-1-/- mice, it can be activated significantly by the adenylyl cyclase agonist forskolin. This indicates that the cAMP/PKA pathway is functional in RAG-1-/--derived parasites but is not fully activated, perhaps due to the absence of specific immune signals required for egg production (Amiri et al., 1992; Saule et al., 2002; Blank et al., 2006). To test this latter possibility, SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity were assessed in worms from RAG-1-/- mice where schistosome development had been restored through induction of innate immune responses with the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR 4) ligand LPS (Akira and Takeda, 2004). Restoration of parasite egg production in vivo resulted in restoration of SmPKA-C mRNA expression and PKA activity to levels comparable with those seen in worms from wild-type mice. Thus, expression of SmPKA-C mRNA and PKA activity in adult S. mansoni correlates with egg production, both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting a significant role for PKA signaling in the reproductive activity of adult schistosomes.

In conclusion, the results we present suggest that in addition to maintaining schistosome viability, PKA signaling in adult worms is specifically involved in the production of eggs by female worms. These results suggest that even at sub-curative levels, targeting PKA in schistosomes could possibly be useful in controlling the transmission of schistosomiasis by preventing or limiting the shedding of eggs in the feces of infected hosts. Furthermore, as the pathology associated with schistosome infection is caused by the deposition of parasite eggs in host tissues, inhibition of egg production through targeting PKA activity could be useful in reducing egg-induced pathology and morbidity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Conor R. Caffrey (University of California, San Francisco, USA) for providing S. mansoni egg cDNA and Dr. Nithya Raghavan (Biomedical Research Institute, USA) for providing S. mansoni miracidia and sporocysts. We thank Dr. Fred Lewis (Biomedical Research Institute, USA) for providing other parasite materials and for invaluable advice and assistance. We thank Mitali Chatterjee and Sean Maynard for technical support. Parasite materials were provided through National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (USA) Contract N01 AI30026. Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant R01 AI066227 (to SJD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abel ES, Davids BJ, Robles LD, Loflin CE, Gillin FD, Chakrabarti R. Possible roles of protein kinase A in cell motility and excystation of the early diverging eukaryote Giardia lamblia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10320–10329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri P, Locksley RM, Parslow TG, Sadick M, Rector E, Ritter D, McKerrow JH. Tumour necrosis factor alpha restores granulomas and induces parasite egg-laying in schistosome-infected SCID mice. Nature. 1992;356:604–607. doi: 10.1038/356604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch PF. Schistosomes: Development, Reproduction and Host Relations. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Blank RB, Lamb EW, Tocheva AS, Crow ET, Lim KC, McKerrow JH, Davies SJ. The common gamma chain cytokines interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 indirectly modulate blood fluke development via effects on CD4+ T cells. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1609–1616. doi: 10.1086/508896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey CR. Chemotherapy of schistosomiasis: present and future. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho-Chung YS, Pepe S, Clair T, Budillon A, Nesterova M. cAMP-dependent protein kinase: role in normal and malignant growth. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1995;21:33–61. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho-Chung YS, Nesterova MV. Tumor reversion: protein kinase A isozyme switching. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1058:76–86. doi: 10.1196/annals.1359.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioli D, Pica-Mattoccia L. Praziquantel. Parasitol Res. 2003;90 1:S3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0751-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, Grogan JL, Blank RB, Lim KC, Locksley RM, McKerrow JH. Modulation of Blood Fluke Development in the Liver by Hepatic CD4+ Lymphocytes. Science. 2001;294:1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1064462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, McKerrow JH. Developmental plasticity in schistosomes and other helminths. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1277–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissous C, Ahier A, Khayath N. Protein tyrosine kinases as new potential targets against human schistosomiasis. Bioessays. 2007;29:1281–1288. doi: 10.1002/bies.20662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerig C. Protein kinases as targets for anti-parasitic chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels D, Chitsulo L, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global epidemiological situation of schistosomiasis and new approaches to control and research. Acta Trop. 2002;82:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon PG, Doenhoff MJ. Drug-resistant schistosomiasis: resistance to praziquantel and oxamniquine induced in Schistosoma mansoni in mice is drug specific. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:83–88. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail M, Botros S, Metwally A, William S, Farghally A, Tao LF, Day TA, Bennett JL. Resistance to praziquantel: direct evidence from Schistosoma mansoni isolated from Egyptian villagers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:932–935. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto F, Shozawa A, Kumada N, Kojima K. Possible roles of cAMP and Ca2+ in the regulation of miracidial transformation in Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol Res. 1989;75:368–374. doi: 10.1007/BF00931132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch J, Kunz W, Grevelding CG. Herbimycin A suppresses mitotic activity and egg production of female Schistosoma mansoni. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1261–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb EW, Crow ET, Lim KC, Liang YS, Lewis FA, Davies SJ. Conservation of CD4+ T cell-dependent developmental mechanisms in the blood fluke pathogens of humans. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis F. Schistosomiasis. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Chapter 19(Unit 19):11. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1901s28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoVerde PT, Andrade LF, Oliveira G. Signal transduction regulates schistosome reproductive biology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama H, Takahashi H, Watanabe K, Fujimaki Y, Aoki Y. The involvement of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the control of schistosome miracidium cilia. J Parasitol. 2004;90:8–14. doi: 10.1645/GE-52R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melman SD, Steinauer ML, Cunningham C, Kubatko LS, Mwangi IN, Wynn NB, Mutuku MW, Karanja DM, Colley DG, Black CL, Secor WE, Mkoji GM, Loker ES. Reduced Susceptibility to Praziquantel among Naturally Occurring Kenyan Isolates of Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P, Clegg RA, Rees HH, Fisher MJ. siRNA-mediated knockdown of a splice variant of the PK-A catalytic subunit gene causes adult-onset paralysis in C. elegans. Gene. 2008;408:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popiel I, Basch PF. Reproductive development of female Schistosoma mansoni (Digenea: Schistosomatidae) following bisexual pairing of worms and worm segments. J Exp Zool. 1984;232:141–150. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402320117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual JF, Ceron J, Koreth J, Hao T, Nicot AS, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Vandenhaute J, Orkin SH, Hill DE, van den Heuvel S, Vidal M. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saule P, Adriaenssens E, Delacre M, Chassande O, Bossu M, Auriault C, Wolowczuk I. Early variations of host thyroxine and interleukin-7 favor Schistosoma mansoni development. J Parasitol. 2002;88:849–855. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0849:EVOHTA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman-Tov MM, Aly R, Shapira M, Jaffe CL. Cloning from Leishmania major of a developmentally regulated gene, c-lpk2, for the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:201–215. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalhegg BS, Tasken K. Specificity in the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. differential expression, regulation, and subcellular localization of subunits of PKA. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d331–342. doi: 10.2741/a195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swierczewski BE, Davies SJ. A Schistosome cAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Catalytic Subunit Is Essential for Parasite Viability. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syin C, Parzy D, Traincard F, Boccaccio I, Joshi MB, Lin DT, Yang XM, Assemat K, Doerig C, Langsley G. The H89 cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor blocks Plasmodium falciparum development in infected erythrocytes. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4842–4849. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Buechler JA, Yonemoto W. cAMP-dependent protein kinase: framework for a diverse family of regulatory enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:971–1005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Kim C, Vigil D, Haste NM, Yang J, Wu J, Anand GS. Dynamics of signaling by PKA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Kim C, Cheng CY, Brown SH, Wu J, Kannan N. Signaling through cAMP and cAMP-dependent protein kinase: diverse strategies for drug design. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]