Abstract

Objective:

Apathy is a very common and significant problem in patients with dementia, regardless of etiology. Observations on frontosubcortical circuit (FSC) syndromes indicate that apathy may have affective, behavioral or cognitive manifestations. We explored whether the apathy manifested in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with its predominantly anterior brain neuropathology differs from the apathy in Alzheimer's disease (DAT) with its predominantly hippocampal and temporoparietal-based neuropathology. We also sought to determine whether other behavioral disturbances reported in FSC syndromes correlate with apathy.

Design:

Survey. Analyses included individual items within Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) subscale items. Items of the Apathy/Indifference subscale were designated by consensus as: A) affective = lacking in emotions, B) behavioral = inactive, chores abandoned or C) cognitive = no interest in others' activities. Proportions of correlated non-apathy NPI items were calculated and displayed using Chernoff faces to facilitate comparison of apathy domains and dementia diagnoses.

Setting and Patients:

Several neurology specialty clinics contributed to our dataset of 92 participants with FTD and 457 with DAT.

Results:

Apathy was more prevalent in FTD than DAT, but when present, the specific apathy symptoms in both dementias were rarely restricted to one of the three domains of apathy. Dysphoria concurrent with apathy was unique to the DAT group and negatively correlated in FTD. Participants with affective apathy more frequently co-presented with an orbitofrontosubcortical syndrome in FTD (impulsivity and compulsions). Affective apathy also co-presented with uncooperative agitation, anger, and physical agitation in both dementias.

Conclusions:

Apathy is common in FTD and in DAT, although it is more common in FTD. When present, it usually involves changes in affect, behavior, and cognition. It is associated with behaviors that have previously been shown to impact on patient safety, independence and quality of life.

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Apathy, Frontotemporal Dementia, Frontotemporal Degeneration

INTRODUCTION

Apathy is increasingly being recognized as a common and clinically significant neurobehavioral syndrome. Previously reported prevalence of apathy in clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease (DAT), the most common cause of dementia among the elderly, ranges from 36% to 88%.1 Similar prevalence of apathy has also been reported in frontotemporal degeneration (FTD, 60% to 90%).2-4 While clinicians appreciate the prevalence of apathy in dementia, little has been reported about its pathophysiology, characteristics, and behavioral associations.

Robert and Marin have proposed that symptoms of apathy may be separable.5, 6 Affective apathy would manifest as symptoms of indifference or lack of empathy. Behavioral apathy is a second domain of apathy, which manifests as indolence and requirement for prompts to initiate physical activity. Cognitive apathy refers to inactivation of goal-directed cognitive activity manifested, for example, by requiring assistance in initiating mental activity or speech. The pattern of symptoms which develop in an individual may depend upon which brain regions have been affected by the neurodegenerative process. We and others propose that each of these domains of apathy derives from dysfunction of frontosubcortical circuits (FSC).7, 8We hypothesized that apathy in FTD would include all domains (affective, behavioral, and cognitive) due to its impact on the superior medial frontal cortex, and that apathy in DAT would have mainly affective features due to damage focused on limbic structures. In addition, patients with DAT do show frontal lobe cognitive dysfunction, opening the range of possible findings to include cognitive apathy.

Beyond the apathy domains manifested by groups, we also hypothesized that non-apathy behavioral correlates ascribed to FSC syndromes would differ between the two dementias: in FTD impulsivity and compulsions would increase in the presence of apathy, and in DAT dysphoria would increase when apathy is present. Irritability or agitation being common to both dementias might not correlate with apathy at all.9

The informant-based Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) has established validity and reliability in clinical trials for symptomatic treatment of dementia and consists of 12 behavioral subscales.10 The criterion for diagnosing apathy with the NPI is any positive response to one or more Apathy/Indifference subscale items. We used NPI data to characterize features of apathy in FTD vs. DAT and then used the NPI subscales referring to hypothesized differences in impulsivity, compulsions, mood disturbance, irritability, and agitation to characterize the associations with apathy in each dementia.

METHODS

Method of Participant Identification and Recruitment

Data for this study were extracted from the existing databases of collaborators at Baycrest, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of California at Los Angeles and University of California at San Francisco clinics serving patients with dementia. Ethics committees at all institutions approved the protocols for collecting the data. Participants or their substitute decision makers provided informed consent for inclusion in the site databases. Participant data were included if the participant had 1) a clinical diagnosis of dementia due to either FTD by consensus criteria 11 or DAT by NINDS-ADRDA criteria12 and 2) full NPI responses from an informant. If the NPI had been administered regarding the same participant on more than one occasion, we included only the earliest NPI scores, with the aim of increasing the possibility that data were taken prior to the use of any psychotropic medications. Duration of illness was defined as the time since report of first symptoms. We identified 92 eligible participants with FTD and 457 with DAT.

Categorization of apathy symptoms: three behavioral neurologists (Jon Ween, and co-authors TWC, MF), three neuropsychologists (Brian Levine, Morris Moscovitch, and co-author DS) and three geriatric psychiatrists (Nathan Herrmann, Robert Madan, and co-author RVR) categorized items on the Apathy/Indifference subscale of the NPI into affective, behavioral, cognitive or generic (two or more) domains, based on the definitions stated above. Agreement by any six or more of the raters on an item identified the categorization used in our comparative analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was used to compare means of continuous patient characteristic variables between FTD and DAT groups. Chi-square tests were used to compare gender distribution, the proportion of patients with apathy between the FTD and DAT groups, and between the FTD subgroups behavioral variant (bvFTD) and primary progressive aphasia (PPA).13

In order to examine the propensity of participants to present with apathy symptoms from multiple domains, we used ordinal logistic regression to compare the number of apathy domains (affective, behavioral, cognitive) endorsed for the participant between FTD and DAT groups, covarying for the total number of apathy subscale items. This allowed us to explore whether patients with different types of dementia were equally likely to show symptoms in a single domain or spread across multiple domains.

Using our hypothesis that affective apathy would be exhibited more frequently in DAT than in FTD, participants in each dementia group were classified as exhibiting either no apathy, affective apathy, or non-affective apathy. Helmert14 contrasts are used to compare each level of a factor with the combined average of subsequent factor levels. Specifically, we used a pair of Helmert contrasts 1) to compare participants who endorsed any of the eight apathy items against those with no apathy and 2) to compare participants who endorsed an item in the affective (A) apathy domain against participants with non-A apathy.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)was used to compare the total NPI score (excluding apathy items) between the two dementia groups and the three apathy subgroups to examine breadth of behavioral disturbance in these patients.

To examine associations between occurrence of apathy and selected non-apathy NPI items, we further narrowed the dataset of non-apathy subscale items to those with relative frequency greater than 6% (at least 5 of the 92 FTD subjects) in either DAT or FTD groups. An initial series of logistic regression models was run to estimate the effects of dementia group and apathy subgroup on each of the remaining 47 non-apathy NPI items. We bundled the 47 non-apathy items into the groups of behavioral disturbances of interest stated in the hypotheses (impulsivity, compulsions, dysphoria, anger, and agitation), based on similarity in the patterns of logistic regression coefficients and on clinical interpretation of the items. Twelve clusters were designated, as described in Table 3.15

Table 3.

Details of associations between behavioral clusters and apathy.Group is assigned values of 0 (DAT) and 1 (FTD). Helmert.1 is assigned values of 0 (no apathy) and 1 (with apathy). Helmert.2 is assigned values of −1/2 (non-affective apathy), 0 (no apathy), and 1/2 (affective apathy). Adjusted Odds Raios (aOR) are calculated with Group, Helmert.1 and Helmert.2 variables in the model with Group × Helmert.1 and Group × Helmert.2 interactions, if either was significant. Values listed in the Intercept column are exp(β0)/[1+exp(β0)] where β0 is the intercept parameter estimate. For all models, p-value for H0: β0 = 0 was less than 0.0001.

| Helmert.1 Apathy vs without Apathy |

Helmert.2 Affective Apathy vs Non- Affective Apathy vs without Apathy |

Group DAT vs FTD |

Intercept | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPI item(s) | Behavioural Cluster |

aOR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | Pr(Y=1|X=0) |

| loss of appetite | anorexia | 2.98 | (1.75, 5.06) | 0.0001 | 1.45 | (0.83, 2.54) | 0.19 | 0.57 | (0.29, 1.13) | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| worried, shaky, tense, avoiding certain situations, separation anxiety |

anxiety | 3.36 | (2.24, 5.06) | <0.0001 | 1.58 | (0.98, 2.54) | 0.06 | 0.59 | (0.35, 1.00) | 0.052 | 0.20 |

| rummaging behavior | rummaging | 2.49 | (1.39, 4.47) | 0.002 | 1.74 | (0.93, 3.27) | 0.08 | 0.59 | (0.28, 1.28) | 0.18 | 0.08 |

| increase in appetite, overeating, change of food preference, or new eating routine |

change in eating habits |

3.72 | (2.25, 6.15) | <0.0001 | 1.15 | (0.69, 1.93) | 0.60 | 4.46 | (2.70, 7.37) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| inappropriate laughing, childlike behavior, witzelsucht, or pranks |

childish behaviour |

1.88 | (1.04, 3.41) | 0.04 | 1.91 | (0.99, 3.70) | 0.053 | 2.95 | (1.63, 5.35) | 0.0004 | 0.06 |

| stubborn, uncooperative, upset at or resisting help with activities of daily living, hard to handle, shouting, cursing |

uncooperative agitation |

2.6 | (1.74, 3.89) | <0.0001 | 2.07 | (1.28, 3.35) | 0.003 | 1.10 | (0.67, 1.81) | 0.71 | 0.20 |

| bad tempered, mood swing, sudden flashes of anger, impatient, cranky, irritable, argumentative |

anger | 2.22 | (1.50, 3.29) | 0.0001 | 1.76 | (1.09, 2.85) | 0.02 | 0.72 | (0.43, 1.20) | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| insensitive comments | insensitivity * | 2.25 | (1.01, 5.01) | 0.048 | 3.10 | (1.28, 7.53) | 0.01 | e5.7 | (e−8.5, e20) | 0.44 | 0.04 |

| e−5.4 | (e−20, e8.7) | 0.45 | 0.14 | (0.02, 0.80) | 0.03 | ||||||

| pacing, repetitive activity, playing with buttons or string, fidgety, repetitive eating behavior |

compulsions | 4.6 | (2.98, 7.09) | <0.0001 | 2.14 | (1.32, 3.47) | 0.002 | 2.95 | (1.80, 4.84) | <0.0001 | 0.13 |

| impulsive, talking to strangers, making crude or sexual comments, public disclosures, taking liberties touching; euphoria |

impulsivity/ euphoria |

3.85 | (2.38, 6.23) | <0.0001 | 2.00 | (1.22, 3.30) | 0.006 | 2.90 | (1.76, 4.78) | <0.0001 | 0.10 |

| tearful, sobbing, acting sad, feeling like a failure, discouraged, seeing no future, feels like a burden to family, or suicidal |

dysphoria * | 3.84 | (2.51, 5.89) | <0.0001 | 1.63 | (0.95, 2.80) | 0.08 | 0.06 | (0.01, 0.26) | 0.0002 | 0.25 |

| 5.27 | (1.77, 15.7) | 0.003 | 0.44 | (0.13, 1.55) | 0.20 | ||||||

| slam doors, kicks or throws things |

physical agitation |

2.73 | (1.49, 5.00) | 0.001 | 2.44 | (1.32, 4.53) | 0.005 | 1.81 | (0.99, 3.33) | 0.055 | 0.06 |

| delusions of theft |

2.58 | (1.38, 4.82) | 0.003 | 1.63 | (0.82, 3.21) | 0.16 | 0.13 | (0.03, 0.52) | 0.004 | 0.07 | |

Statistics for significant Group×Helmert.1 and Group×Helmert.2 interactions are listed in a second row for the associated behavioral cluster

Logistic regression was used to compare the occurrence of a behavioral disturbance in each of the 12 behavioral clusters as a function of dementia and apathy subgroup (no apathy at all, affective apathy, and non-A apathy). The two Helmert contrasts were included in the regression as were interactions between dementia group and each of the Helmert contrasts. If neither interaction was found to be significant, they were both removed from the model, and parameters were re-estimated. All hypothesis tests reported in the Results section were performed at an alpha level of 5%. Please see Appendix table for specific p-values.

RESULTS

Of the 92 participants with FTD, 53 had bvFTD and 39 had PPA. See Table 1 for demographics and MMSE scores of the FTD and DAT groups. Durations of illness, education levels, and MMSE scores were not available for all eligible participants. Although the groups were not matched for age, educational level, MMSE or total NPI scores, there were no significant differences among groups for any of these variables.

Table 1.

Characterization of the study sample.

| Dementia of Alzheimer Type n=457 |

All Frontotemporal Dementias n=92 |

Behavioral variant FTD n=53 |

Primary Progressive Aphasia n=39 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% men) | 38.5% | 38% | 37.7% | 38.5% |

| Mean age in years at time of NPI (range) |

67.5 (33-90) | 60 (22-77) | 62 (29-79) | 65 (50-79) |

| Mean duration of illness in years at the time of the NPI (range) |

4.0 (7-20) n=326 |

3.7 (1-12) n=67 |

3.6 (1-12) n=39 |

3.8 (1-10) n=28 |

| Mean years of education (range) |

13 (0-28) n=343 |

14 (0-28) n=68 |

14.8 (5-23) n=40 |

13.2 (1-22) n=28 |

| Mean MMSE score (range) |

20.4 (0-30) n=409 |

21.1 (0-30) n=78 |

22.6 (0-30) n=43 |

19.2 (0-30) n=35 |

| Mean Total NPI score (range) |

13.7 (0-100) | 23 (0-75) | 30 (0-75) | 13.6 (0-50) |

Table 2 shows the prevalence of psychotropic drug classes most commonly prescribed to this sample. Serotonergic agents (including selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors and trazodone) were more commonly prescribed to FTD participants, while cholinesterase inhibitors were more frequent in DAT at the time of NPI administration. Antipsychotic medication use was not common.

Table 2.

Counts of participants using most prevalent medications at the time of data acquisition.

| Medication Class Taken at Time of NPI |

Frontotemporal Dementia n = 92 |

Alzheimer's disease n = 457 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drug |

28 (30.1%) | 143 (29.6%) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

25 (26.9%) | 96 (19.9%) |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | 20 (21.5%) | 218 (45.1%) |

| Antipsychotic | 12 (12.9%) | 26 (5.4%) |

Apathy, defined as any positive response to items on the NPI Apathy/In-difference subscale, was reported in n = 66/92 = 72% of the FTD group, significantly more frequently than in the DAT group (n = 255/457 or 56%; χ2, p = .001). Among the FTD cases, 42 (79%) of bvFTD and 24 (62%) of PPA had apathy (χ2 p = .062).

Apathy domains in FTD and DAT

The raters had ≥ 6/9 agreement on the designation of only 4 NPI apathy items into affective, behavioral or cognitive apathy domains.‘Other Apathy’ from the NPI Apathy/Indifference subscale was too general and therefore was not included in this analysis.

Large percentages of the apathetic participants (100% in FTD, 92.5% in DAT) demonstrated behavioral apathy (either decreased spontaneous activity or decreased pursuit of baseline interests). There was considerable overlap among apathy domains as we had designated them. Forty-six percent of FTD subjects with apathy and 19% of DAT with apathy showed concurrent A, B, and C apathy symptoms. Results of an ordinal logistic regression showed that the number of endorsed A, B, or C apathy domains endorsed increased with total NPI score (p value < .00001), but there was no significant difference in the number of A, B, or C domains endorsed when FTD was compared against DAT.

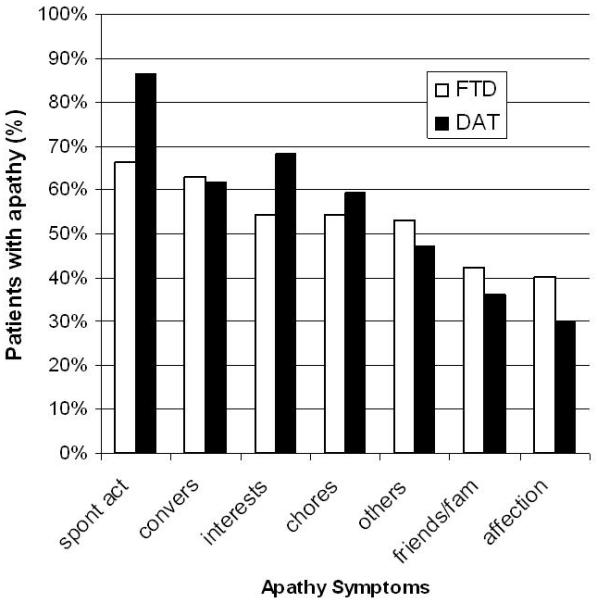

Small segments of the apathetic DAT sample (10 participants) endorsed only apathy items outside of those described above: decreased spontaneous conversation, loss of interest in family or friends, dropping former interests, or not pursuing novel stimuli. FTD and DAT groups exhibited similar rank orders for frequencies of the 7 NPI apathy items reported by informants (see Figure 1). ANOVA showed that participants with apathy had higher total NPI scores (apathy subscale frequency × severity score excluded) than those without apathy (t543 = 7.60, p < 0.0001) and participants with affective apathy had higher total NPI scores (apathy subscale frequency × severity score excluded) than those without affective apathy (includes no apathy, presence of B and/or C apathy and/or apathy not categorized as A, B, or C domain; t543 = 5.61, p < 0.0001). Participants with FTD had higher total NPI scores (apathy subscale frequency × severity score excluded) than those with DAT (t543 = 2.54, p = 0.01).

Figure 1.

Behavioral associates of APATHY

The first Helmert contrast in the logistic regression model revealed that presence of apathy was associated with higher proportions of anorexia (20% vs. 5%), anxiety cluster (38% vs.19%), rummaging (13% vs. 9%), change in eating habits (45% v 14%), childish behavior (20% v 9%) and delusions of theft (9% vs. 4%, see Table 3).

Behavioral associates of AFFECTIVE APATHY

Behavioral associates of affective apathy (second Helmert contrast, comparing second and third columns in Table 3) were only observed when the first Helmert contrast was also significant. Both Helmert contrasts applied to the following behavioral disturbances: uncooperative agitation (48% affective apathy vs. 37% non-affective apathy vs. 18% without apathy), anger (42% vs. 32% vs. 23%), insensitivity (29% vs. 14% vs. 5%), compulsions (63% vs. 46% vs. 22%), and impulsivity and/or euphoria (51% vs. 33% vs. 17%). The presence of apathy, especially affective apathy, was associated with a polarization toward the more extreme mood and behavioral disturbances characteristic of each dementia.

Behavioral Associates of GROUP

As expected from the clinical diagnostic criteria for these dementias, logistic regression revealed that participants with FTD showed statistically significantly higher proportions of compulsions (55% vs 32%), impulsivity (44% vs. 23%), change in eating habits (49% vs 20%), and childish behavior (23% vs. 9%) than participants with DAT.

Participants with DAT had higher proportions than FTD of the dysphoria cluster (42% vs. 27%) and delusions of theft (14% vs. 2%).

In the case of the dysphoria cluster, we identified a group × Helmert 1 interaction. In patients with DAT, those with apathy had a higher proportion of tears/sobbing; acting sad; feeling like a failure, discouraged, anticipating no future, burden to family, or suicidal than those without apathy (50% vs 22%). The opposite held in FTD: those with apathy had a lower proportion of the dysphoric symptoms than FTD without apathy (24% vs. 31%).

In the case of physical agitation, both Helmert contrasts were significant, as well as a group × Helmert 2 interaction. A significantly higher proportion of participants with DAT and affective apathy were reported to be physically agitated than participants with DAT and non-affective apathy (16 v 6%). On the other hand, a lower proportion of participants with FTD and affective apathy were physically agitated than participants with FTD with non-affective apathy (8 v 17%).

Power calculations entailed revisiting our logistic regression model with three variables: group (FTD vs. DAT) and the two Helmert contrasts. Power of the hypothesis tests for a binary predictor variable in logistic regression is a function of alpha level, sample size, effect size, event rate, and distribution of predictor variable.16 Hypothesis tests with our sample of 549 participants were performed at an α-level of 5%. Of the 549 participants in this study, 92 (17%) had FTD and 321 (59%) had apathy. Among the 321 participants with apathy, 114 (36%) had affective apathy. The baseline event rate for the included behavioral disturbances ranged from 2 to 25%.

Odds ratios for the significant group effects reported above ranged from 2.90 to 4.46 and one significant odds ratio less than one (0.457) for dysphoria. Power for these hypothesis tests exceeded 88% for all but dysphoria, which had power of 66%.

Odds ratios for the significant comparisons of participants with apathy to those without ranged from 1.88 to 4.60. Power for these hypothesis tests exceeded 88% for all but two comparisons: physical agitation, which had a baseline event rate (3.9%), an odds ratio of 2.65 and power of 71%; and euphoria, which had a 6% baseline event rate, the lowest significant odds ratio (OR = 1.88) and power of 49%.

Odds ratios for the significant comparisons of participants with affective apathy versus those with non-affective apathy ranged from 1.76 to 2.44. Power for these comparisons ranged from 54 to 79%.

DISCUSSION

Apathy is rarely the sole behavioral change occurring in FTD or DAT. With apathy, patients with FTD and DAT are likely to be less active, but the behavioral disturbances present are more abnormal. That apathy is prevalent in dementia, whether the etiology is probable DAT or FTD, is not a new finding,17, 18 but the higher association of apathy with depressive features in DAT calls attention to for the negative mood disruption in DAT patients with apathy, in contrast with FTD patients who are more likely to have apathy without accompanying depression. We had hypothesized that in DAT, limbic neurodegeneration might sway apathy toward the affective domain. Concomitant depression supported this hypothesis, although, as described above, apathy in both DAT and FTD was infrequently restricted to the affective domain, implying simultaneous involvement of several FSCs.

As opposed to prior work proposing that apathy and disinhibition in FTD patients are mutually exclusive,19 our study indicates that apathy is not a benign behavioral disturbance in dementia: when present, it is more likely for a patient to also manifest behaviors that are difficult to manage, whether impulsivity, socially embarrassing behaviors or irritability, lability, and resistance to care. In addition, emotional blunting is often considered as a separate symptom from behavioural or cognitive apathy,17 but our study shows that the three very commonly co-occur. Our sample was predominantly made up of subjects with early onset (mean ages in 60s) and fairly early in course of illness (mean 4 years). One might expect this sample to have biased the results toward the hypothesized polarizations between DAT and FTD, or even between apathetic FTD and disinhibited FTD subjects, yet we were unable to elicit such distinctions.

Davis and Tremont report that apathy in dementia does not contribute to caregiver perception of burden,20 but our study highlights the fact that apathy often co-occurs with other behaviors that do add to caregiver distress.

The symptoms of apathy manifested in this study did not differ based on dementia etiology, but unpacking all responses on the NPI revealed that apathy was accompanied in FTD by behavioral disturbances that accord to an orbitofrontosubcortical syndrome. The findings in DAT with apathy defied our assumption that a damaged limbic circuit would result in affective apathy alone; behavioral and cognitive apathy domains were endorsed in DAT as frequently as in FTD, implying the additional involvement of at least the right dorsolateral prefrontal-subcortical circuit. The pathological changes of FTD and AD overlap considerably in location, so that it is entirely possible that each may affect much of the same circuitry. Amyloid imaging studies have shown burden in the frontal lobes early in the course of AD,21 and Royall has emphasized that the diagnosis of AD is probably not made until after the disease has affected the frontal systems.22

Mourik et al. report similar prevalence of apathy in FTD but did not find correlations of apathy with other NPI subscales.23 Differences from the present findings may be due to longer duration of illness among their sample (mean 6.7 years) and use of subscales of the NPI instead of specific subscale items. As patients progress, they become less able to enact socially inappropriate impulses. Our analysis of the NPI data allow for the individual apathy symptoms present to carry more weight as symptoms of illness and may therefore be more sensitive to caregiver report.

Interrater re-categorization of apathy items facilitated exploration of our hypotheses that apathy in FTD would include all domains (affective, behavioral, and cognitive) due to its impact on the superior medial frontal cortex and that apathy in DAT would have mainly affective features due to damage focused on limbic structures, but it is worth noting that half of the apathy subscale items did not achieve consensus categorization by the raters. Our process was arbitrary, and the anatomical substrates of the apathy domains are certainly speculative. Raising the issue of apathy being associated with depression circumvents the assignation of how one might assign an observation of “loss of interest” to apathy vs. to depression. It is a manifestation of both.

We confirmed that apathy is more common in FTD than in DAT. When present, apathy usually involves changes in affect, behavior, and cognition. It is associated with the co-occurrence of major mood or behavioral disturbances that may not be anticipated if clinicians focus too closely on the apathy itself.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors TWC and MAB had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work was funded by NIA grant F32 AG022802 (TWC); the Saul A. Silverman Family Foundation, as part of a Canada International Scientific Exchange Program project and Canadian Institutes of Health Research 53267 (MF); and by the University of Toronto Dean's Fund for New Faculty (#457494 TWC); an endowment to the Sam and Ida Ross Memory Clinic (TWC, MF); Canadian Institutes of Health Research MT – 12853, MRC - GR - 14974, James S. McDonnell Foundation 21002032 (DTS); Canadian Institutes of Health Research 13129 (SEB, IL, DTS). D. Stuss is the Reva James Leeds Chair in Neuroscience and Research Leadership. S. Black is the Brill Chair in Neurology at the University of Toronto (supported by the University of Toronto and the Foundation of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre).

REFERENCES

- 1.van Reekum R, Stuss DT, Ostrander L. Apathy: Why care? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2005;17:7–19. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow TW, Miller BL, Boone K, Mishkin F, Cummings J. Frontotemporal Dementia Classification and Neuropsychiatry. The Neurologist. 2002;8:263–269. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy M, Miller BL, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, Craig A. Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementias: behavioral distinctions. Arch. Neurol. 1996;53:687–690. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550070129021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow TW. Treatment approaches to symptoms associated with frontotemporal degeneration. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0040-5. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert PH, Clairet S, Benoit M, et al. The apathy inventory: assessment of apathy and awareness in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:1099–1105. doi: 10.1002/gps.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin RS. Apathy: A neuropsychiatric syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1991;3:243–254. doi: 10.1176/jnp.3.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuss DT, van Reekum R, Murphy K. Differentiation of states and causes of apathy. In: Borod J, editor. The Neuropsychology of Emotion. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 340–363. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy R, Dubois B. Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:916–28. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srikanth S, Nagaraja AV, Ratnavalli E. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia-frequency, relationship to dementia severity and comparison in Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2005;236:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–54. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Mental and clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2001;58:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harville DA. Matrix Algebra from a Statistician's Persepective. 1st ed. Springer; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Soete G, De Corte W. On the perceptual salience of features of Chernoff faces for representing multivariate data. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1985:9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demidenko E. Sample size determination for logistic regression revisited. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26:3385–3397. doi: 10.1002/sim.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendez MF, Lauterbach EC, Sampson SM, ANPA Committee on Research An evidence-based review of the psychopathology of frontotemporal dementia: a report of the ANPA Committee on Research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20:130–149. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2008.20.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollingworth P, Hamshere ML, Moskvina V, et al. Four components describe behavioral symptoms in 1,120 individuals with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1348–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snowden JS, Bathgate D, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Gibbons ZC, Neary D. Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2001;70:323–332. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis JD, Tremont G. Impact of frontal systems behavioral functioning in dementia on caregiver burden. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19:43–49. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royall DR, Palmer R, Mulroy AR, et al. Pathological determinants of the transition to clinical dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Aging Res. 2002;28:143–162. doi: 10.1080/03610730252800166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourik JC, Rosso SM, Niermeijer MF, Duivenvoorden HJ, Van Swieten JC, Tibben A. Frontotemporal dementia: behavioral symptoms and caregiver distress. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18:299–306. doi: 10.1159/000080123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]