Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To estimate the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and examine their association with functional limitations.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional analysis.

SETTING

The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS).

PARTICIPANTS

A sample of adults aged 71 and older (N = 856) drawn from Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative cohort of U.S. adults aged 51 and older.

MEASUREMENTS

The presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, apathy, elation, anxiety, disinhibition, irritation, and aberrant motor behaviors) was identified using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. A consensus panel in the ADAMS assigned a cognitive category (normal cognition; cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND); mild, moderate, or severe dementia). Functional limitations, chronic medical conditions, and sociodemographic information were obtained from the HRS and ADAMS.

RESULTS

Forty-three percent of individuals with CIND and 58% of those with dementia exhibited at least one neuropsychiatric symptom. Depression was the most common individual symptom in those with normal cognition (12%), CIND (30%), and mild dementia (25%), whereas apathy (42%) and agitation (41%) were most common in those with severe dementia. Individuals with three or more symptoms and one or more clinically significant symptoms had significantly higher odds of having functional limitations. Those with clinically significant depression had higher odds of activity of daily living limitations, and those with clinically significant depression, anxiety, or aberrant motor behaviors had significantly higher odds of instrumental activity of daily living limitations.

CONCLUSION

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are highly prevalent in older adults with CIND and dementia. Of those with cognitive impairment, a greater number of total neuropsychiatric symptoms and some specific individual symptoms are strongly associated with functional limitations.

Keywords: neuropsychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment, prevalence, functional status

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as agitation, depression, apathy, delusions, and hallucinations, are highly prevalent in older adults with dementia or milder forms of cognitive impairment.1 These symptoms have important implications for patients, families, and policymakers because they may be associated with greater caregiver distress,2,3 higher risk for functional decline,4–6 earlier institutionalization,5–8 higher healthcare costs,9–12 and greater mortality.5

A number of studies have examined the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in clinical samples with cognitive impairment.4,13–15 One reported that apathy, agitation, and anxiety were the most common symptoms in those with Alzheimer’s disease and that their prevalence was 72%, 60%, and 48%, respectively.15 Because clinical samples are often subject to referral bias, these estimates may not apply to cognitively impaired adults in nonclinical samples. Of the few population-based studies reporting the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms, most have been conducted on regional samples16–21 and have assessed individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia but did not include those with normal cognition.1,16,18,20,21 Most individual neuropsychiatric symptoms were more prevalent with increasing severity of cognitive impairment, whereas some symptoms (e.g., delusions, depression, and anxiety) were less frequent in those with severe dementia than in those with moderate dementia.16,22 Studies on regional samples may provide biased estimates of symptom prevalence because of possible differences across regions in sociodemographic and health characteristics of the population.23

Studies examining an association between neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional limitations have shown mixed results and are difficult to interpret because of lack of adjustment for co-occurring symptoms.4,24,25 In addition, these studies may lack generalizability because of nonrepresentative samples in a clinical setting. Two studies using regional samples found an association between the presence of hallucinations and functional limitations.25,26

The goal of the current study was to estimate the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms according to severity of cognitive impairment (normal cognition; cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND); mild, moderate, and severe dementia) using a population-based nationally representative sample of older adults in the United States. It was hypothesized that neuropsychiatric symptoms would generally increase with increasing severity of cognitive impairment but that symptom prevalence might be somewhat lower in those with severe dementia and that the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms would be associated with more limitations in basic activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), independent of the level of cognitive impairment.

METHODS

Sample

Data from the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) and the 2000 and 2002 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) were used. The HRS is an ongoing biennial longitudinal survey of a nationally representative cohort of more than 20,000 U.S. adults aged 51 and older who reside in the community and in nursing homes throughout the 48 contiguous United States.27 The HRS sample is selected using a multistage area probability sample design, and population weights are constructed so that valid inferences can be drawn for the entire U.S. population aged 51 and older. Weights are constructed in a two-step process. The first step develops poststratified household weights using the initial sampling probabilities for each household, as well as birth year, race or ethnicity, and sex of household members. The second step uses these household weights to then construct poststratified respondent-level weights that are scaled to yield weight sums corresponding to the number of individuals in the U.S. population as measured by the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey for the month of March in the year of data collection.28 The National Institute on Aging sponsors the HRS, which the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan conducts. The ADAMS is a substudy of the HRS focused on identifying the prevalence and outcomes of cognitive impairment and dementia. The ADAMS sample was a stratified random subsample of 1,770 individuals aged 71 and older from five cognitive strata based on scores for the 35-point HRS cognitive scale (HRS cog)29 or proxy assessments of cognition from the 2000 or 2002 wave of the HRS.30 The ADAMS further stratified the three highest cognitive strata according to age (70–79 vs ≥80) and sex to ensure adequate numbers in each subgroup.30

One hundred nine individuals (12.7%) in the ADAMS sample resided in nursing homes at the time of the ADAMS assessment. Population weights for nursing home residents were derived using data from the 2000 Census and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set.30 Full details of the ADAMS sample design and selection procedures are described elsewhere.30–32 The initial assessments of the ADAMS subjects occurred between July 2001 and December 2003, on average, 13.3 ± 6.9 months after the most-recent HRS interview. The study flow and additional details on participation rates have been reported previously.32 A total of 856 individuals (mean age 81.5) received the initial ADAMS assessment. Sixteen individuals for whom the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) was not completed (n = 840 for current analyses) were not included. To minimize the potential bias due to selective nonparticipation, a response propensity analysis was performed in the ADAMS, and nonresponse adjustments to the ADAMS sample selection weights were developed.30 Population sample weights were then constructed to take into account the probabilities of selection in the stratified sample design and to adjust for differential nonparticipation in the ADAMS.30

The ADAMS data are publicly available and can be obtained from the HRS Web site (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu). The institutional review boards at Duke University Medical Center and the University of Michigan approved all study procedures, and study participants or their surrogates provided informed consent.

Measurements

Cognitive Evaluation

In the ADAMS, a nurse and a neuropsychology technician assessed all participants at their residence for cognitive impairment. The full details of the assessment and diagnostic procedures are described elsewhere.31,32 During the assessment, participants completed a battery of neuropsychological measures, a self-reported depression measure, a standardized neurological examination, a blood pressure measurement, and collection of buccal deoxyribonucleic acid samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping and watched a 7-minute videotaped segment covering portions of the cognitive status and neurological examinations. Proxy informants provided information about the participant’s cognitive impairment, functional limitations, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and medical history. The informant was a spouse or child in 73% of cases, and informants lived with the participant in 53% of the cases. The ADAMS consensus expert panel of neuropsychologists, neurologists, geropsychiatrists, and internists reviewed all information collected during the in-home assessment and assigned cognitive diagnoses. Diagnoses were within three cognitive categories: normal cognitive function, CIND, and dementia. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised, and Fourth Edition criteria were used for diagnosis of dementia. CIND was defined as mild cognitive or functional impairment reported by the participant or informant that did not meet criteria for dementia or performance on neuropsychological measures that was below expectation and at least 1.5 SDs below published norms on any test within a cognitive domain (e.g., memory, orientation, language, executive function, praxis).

Participants with dementia were classified according the stage or severity using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale,33–35 a widely used assessment tool that stages the severity of dementia based on information obtained from the participant and informant during the course of the evaluation. As in prior studies,16,22 mild dementia was defined as CDR stage 0.5 or 1.0, moderate dementia as CDR stage 2.0, and severe dementia as CDR stages 3.0 to 5.0.

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

The ADAMS assessed neuropsychiatric symptoms using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). The NPI is a widely accepted measure of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with cognitive impairment.36 It collects information on symptoms during the past month in 10 domains—delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, elation, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, and aberrant motor behaviors—using a structured interview with a knowledgeable informant. For each symptom reported by the informant, additional information is obtained on the frequency (4-point scale), severity (3-point scale), and associated care-giver distress (6-point scale) associated with the behavior. Symptoms were defined as clinically significant if the product of the frequency and severity score of the reported symptom was 4 or higher.37 Psychometric properties of the NPI have been previously reported.36 The NPI has been validated in prior studies and has also been shown to have good reliability (Cronbach alpha was 0.88 for internal consistency reliability).36

Functional Limitations

The number of limitations in ADLs and IADLs was assessed in the ADAMS using an informant questionnaire. The ADLs assessed were getting across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, transferring, and toileting. The IADLs assessed were preparing meals, grocery shopping, making telephone calls, taking medications, and handling finance. The number of difficulties was categorized using three ordinal levels (0, 1 or 2, ≥3) for ADLs and IADLs.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Data were obtained on participant age (71–79, 80–89, ≥90), sex, race (white, black, other), and years of formal education (<12, 12, > 12 years) from the ADAMS. Household net worth was categorized according to quartile, and marital and living status (married or partnered living together, unmarried living with other, unmarried living alone) were determined using data from the 2000 and 2002 waves of the HRS.

Chronic Medical Conditions

The HRS collects data on the presence of chronic medical conditions (heart disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, musculoskeletal conditions, stroke, and psychiatric problems) in each wave of the survey.38 Respondents report whether a physician has ever diagnosed each condition. Data on chronic conditions from the 2000 or 2002 wave of the HRS were used and included in the analysis as dichotomous variables.

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics, cognitive category, and chronic medical conditions were compared between those without any neuropsychiatric symptoms, those with one or two symptoms, and those with three or more symptoms using chi-square tests. Using the ADAMS sample weights, the prevalence of none, one to two, and three or more neuropsychiatric symptoms and then the prevalence of each individual neuropsychiatric symptom, stratified according to cognitive category (normal cognition; CIND; mild, moderate, or severe dementia), were computed.

Because one goal of the analysis was to identify whether the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms was independently associated with a greater risk of functional limitations, ordinal logistic regression models with ADL and IADL limitations as the dependent variable were estimated to examine whether total number of neuropsychiatric symptoms was associated with functional limitations, adjusting for sociodemographic factors, chronic medical conditions, and cognitive category. Similar ordinal logistic regression models were then estimated to examine whether individual neuropsychiatric symptoms were associated with functional limitations, adjusting for the presence of co-occurring neuropsychiatric symptoms. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were computed to compare the relative strength of the association between each neuropsychiatric symptom and functional limitations. To test the hypothesis that level of cognitive impairment modifies the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional limitations, significant interactions between cognitive category and neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., total number of neuropsychiatric symptoms by cognitive category, the presence of delusions by cognitive category) were tested for. None of these interaction terms was statistically significant, so they were not included in the final regression models. The analysis was repeated with the variables for clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms (frequency score times severity score ≥4), and these results were compared with those from the previous analyses for the presence or absence of any neuropsychiatric symptoms.

It was verified that the proportional odds assumption was not violated by checking for the same OR from two logistic regression models that used different levels of ADL or IADL limitations for dichotomizing the dependent variable (0 vs ≥1 limitations; and ≤2 vs ≥3 limitations). The proportional odds assumption was verified using the Score test.39 All analyses were weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design (stratification, clustering, and nonresponse) of the HRS and ADAMS. STATAversion 10.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was used for data analysis. All reported P values are two-tailed, and P< .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Sample

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample stratified according to the number of neuropsychiatric symptoms (0, 1–2, ≥3). Women, people with low net worth, and people living in a nursing home were more likely to have neuropsychiatric symptoms. CIND and dementia, as well as diabetes mellitus, heart disease, and stroke, were all associated with greater risk for the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics According to Number of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

| Characteristic | n (%) | P-Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0 | 1 or 2 | ≥3 | ||

| Sample (weighted %†) | 840 (100.0) | 518 (70.6) | 202 (20.3) | 120 (9.1) | |

| Age | .29 | ||||

| 71–79 | 349 (58.9) | 243 (61.4) | 73 (53.8) | 33 (51.1) | |

| 80–89 | 360 (34.0) | 203 (32.3) | 90 (38.6) | 67 (36.9) | |

| 90– | 131 (7.1) | 72 (7.3) | 39 (7.6) | 20 (12.0) | |

| Sex | .003 | ||||

| Female | 492 (60.6) | 296 (61.0) | 113 (51.4) | 83 (78.5) | |

| Male | 348 (39.4) | 222 (39.0) | 89 (48.6) | 37 (21.5) | |

| Race | .05 | ||||

| White | 650 (89.7) | 394 (88.9) | 163 (93.5) | 93 (87.5) | |

| Black | 157 (7.3) | 104 (8.2) | 31 (5.5) | 22 (4.9) | |

| Other | 33 (3.0) | 20 (2.9) | 8 (1.0) | 5 (7.6) | |

| Education, years | .03 | ||||

| <12 | 430 (33.4) | 249 (31.3) | 111 (40.1) | 70 (34.9) | |

| 12 | 195 (29.2) | 110 (27.2) | 59 (37.2) | 26 (26.8) | |

| > 12 | 215 (37.4) | 159 (41.5) | 32 (22.7) | 24 (38.3) | |

| Household net worth quartile | <.001 | ||||

| 1 | 331 (25.2) | 172 (19.5) | 90 (31.3) | 69 (55.7) | |

| 2 | 193 (22.0) | 128 (22.3) | 43 (23.8) | 22 (15.9) | |

| 3 | 159 (24.6) | 110 (27.3) | 32 (18.3) | 17 (17.5) | |

| 4 | 156 (28.2) | 107 (30.9) | 37 (26.6) | 12 (10.9) | |

| Cognitive category | <.001 | ||||

| Normal cognition | 303 (64.0) | 258 (74.5) | 37 (42.6) | 8 (30.7) | |

| Cognitive impairment, no dementia | 238 (22.2) | 151 (17.4) | 64 (36.2) | 23 (27.9) | |

| Mild dementia | 153 (7.6) | 71 (5.8) | 48 (11.5) | 34 (12.9) | |

| Moderate dementia | 64 (2.5) | 17 (0.8) | 23 (3.7) | 24 (12.3) | |

| Severe dementia | 82 (3.7) | 21 (1.5) | 30 (6.0) | 31 (16.2) | |

| Living situation | <.001 | ||||

| Alone | 270 (35.2) | 181 (36.8) | 53 (26.6) | 36 (42.1) | |

| With other | 150 (12.8) | 79 (11.2) | 46 (18.9) | 25 (11.3) | |

| With spouse or partner | 335 (46.9) | 223 (49.4) | 77 (46.5) | 35 (28.3) | |

| Nursing home | 85 (5.1) | 35 (2.6) | 26 (8.0) | 24 (18.3) | |

| Chronic medical condition | |||||

| Hypertension | 494 (60.0) | 301 (59.0) | 115 (59.6) | 78 (68.9) | .34 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 172 (19.8) | 95 (16.3) | 55 (33.3) | 22 (17.7) | .004 |

| Cancer | 161 (19.3) | 101 (19.3) | 40 (19.3) | 20 (19.4) | >.99 |

| Lung disease | 79 (8.5) | 43 (6.5) | 26 (14.4) | 10 (10.5) | .06 |

| Heart disease | 279 (30.1) | 158 (24.7) | 83 (41.0) | 56 (46.8) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 180 (15.5) | 87 (13.6) | 52 (16.1) | 41 (29.2) | .005 |

| Psychiatric illnesses | 170 (16.1) | 64 (9.9) | 56 (24.9) | 50 (44.0) | <.001 |

| Arthritis | 592 (70.6) | 354 (68.5) | 146 (72.6) | 92 (82.5) | .15 |

P-values were derived from the chi-square test for association between the indicated variable and the number of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Percentages are weighted percentages derived using the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) sample weights to adjust for the complex sampling design of the ADAMS.

Prevalence of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

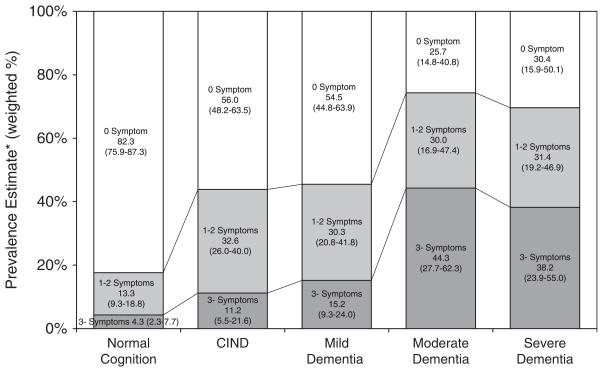

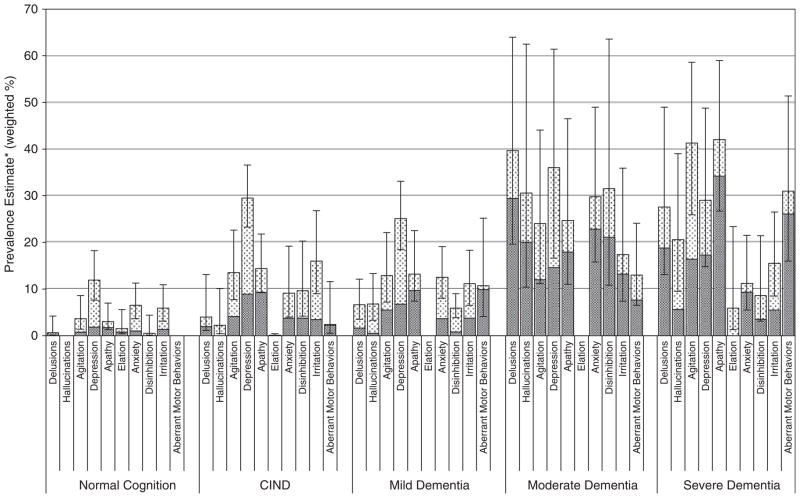

Figure 1 shows the estimated prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms for each of the cognitive categories. Generally, the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms increased with increasing severity of cognitive impairment. There was a slightly lower prevalence of symptoms in those with severe dementia than in those with moderate dementia, although this difference was not statistically significant. Figure 2 shows the estimated prevalence of each individual neuropsychiatric symptom according to cognitive category. Most neuropsychiatric symptoms were more common in those with more-advanced cognitive impairment. Depression was the most common individual symptom in those with normal cognition, CIND, and mild dementia (12% in normal cognition, 30% in CIND, and 25% in dementia), whereas apathy (42%), agitation (41%), and aberrant motor behaviors (31%) were the most common in those with severe dementia. The proportion of clinically significant symptoms (the shaded area in each graph, frequency score by severity score ≥4) was higher in those with more severe cognitive impairment for most neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Figure 1.

Total number of neuropsychiatric symptoms according to cognitive category. Prevalence estimates were derived using the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) sample weights to adjust for the complex sampling design of the ADAMS; 95% confidence intervals are in parentheses.

CIND = cognitive impairment without dementia.

Figure 2.

Estimated prevalence of individual neuropsychiatric symptoms according to cognitive category. Prevalence estimates were derived using the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) sample weights to adjust for the complex sampling design of the ADAMS. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Shaded areas in the graphs represent clinically significant symptom (i.e., frequency score by severity score is ≥4).

CIND = cognitive impairment without dementia.

Association with Functional Limitations

Table 2 shows the results of an ordinal logistic regression for the association between neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., total number of symptoms, individual symptoms) and functional limitations in participants with CIND and dementia. The first (ADL limitations) and third (IADL limitations) columns of the table show the adjusted ORs for a higher level of functional limitations in those presenting with the neuropsychiatric symptoms than in those without the symptoms. The model adjusts for other co-occurring symptoms, cognitive category (e.g., CIND, mild, moderate, or severe dementia), sociodemographic characteristics, and chronic medical conditions. The second (ADL limitations) and fourth (IADL limitations) columns of the table show the adjusted ORs for a higher level of functional limitations in those presenting with clinically significant symptoms than in those without clinically significant symptoms. Individuals with three or more neuropsychiatric symptoms and one or more clinically significant symptoms had significantly higher odds of ADL and IADL limitations. Those with clinically significant depression had higher odds of ADL limitations, and those with clinically significant depression, anxiety, or aberrant motor behaviors had significantly higher odds of IADL limitations. The analysis was repeated after excluding those with CIND (i.e., an analysis of only those with dementia), adjusting for dementia severity and the other covariates. The results were generally similar to those obtained for the analysis of the combined CIND–dementia group (data not shown).

Table 2.

Risk of Functional Limitations Associated with Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

| Symptom | OR† (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACL Limitations | IADL Limitations | |||

| Presence of Symptoms | Clinically Significant Symptoms* | Presence of Symptoms | Clinically Significant Symptoms* | |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory symptoms | ||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 1 or 2 | 1.48 (0.77–2.87) | 2.39 (1.02–5.56) | 1.69 (0.73–3.90) | 3.07 (1.27–7.40) |

| ≥3 | 3.79 (1.82–7.88) | 5.90 (2.39–14.57) | 6.02 (2.80–12.96) | 6.69 (2.84–15.75) |

| Cognitive category | 1.98 (1.55–2.52) | 1.78 (1.38–2.31) | 3.78 (2.52–5.69) | 3.61 (2.41–5.41) |

| Individual symptoms | ||||

| Delusions | 1.69 (0.55–5.16) | 0.44 (0.05–3.65) | 0.98 (0.28–3.45) | 2.10 (0.08–50.43) |

| Hallucinations‡ | 0.91 (0.33–2.47) | 3.88 (0.28–53.39) | 0.57 (0.20–1.66) | — |

| Agitations | 1.76 (0.78–3.96) | 1.78 (0.45–6.98) | 1.81 (1.02–3.21) | 0.67 (0.14–3.20) |

| Depression | 2.46 (0.93–6.55) | 7.07 (2.84–17.59) | 1.53 (0.75–3.09) | 2.60 (1.14–5.90) |

| Apathy | 1.17 (0.62–2.24) | 1.94 (0.89–4.23) | 1.29 (0.52–3.18) | 1.66 (0.66–4.14) |

| Elation‡ | 2.69 (0.11–60.85) | — | — | — |

| Anxiety | 0.76 (0.25–2.23) | 2.28 (0.51–10.06) | 1.41 (0.42–4.72) | 10.41 (2.19–49.41) |

| Disinhibition | 1.38 (0.53–3.57) | 1.79 (0.32–9.93) | 4.05 (2.02–8.11) | 0.67 (0.15–2.83) |

| Irritation | 1.01 (0.40–2.55) | 1.31 (0.33–5.13) | 1.02 (0.49–2.14) | 3.04 (0.60–15.31) |

| Aberrant motor behaviors | 0.41 (0.20–0.84) | 0.40 (0.17–0.94) | 4.32 (0.94–19.71) | 5.47 (1.56–19.08) |

| Cognitive category | 2.25 (1.64–3.09) | 2.30 (1.72–3.08) | 3.66 (2.37–5.64) | 3.46 (2.28–5.26) |

Clinically significant symptoms are defined as a frequency score times severity score of ≥4.

Odds ratio (OR) derived using an ordered logistic regression model with the three ordinal levels of activity of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) limitations (0, 1–2, ≥3) as the dependent variable. ORs >1.00 indicate greater odds of more-significant limitations.

Unable to estimate because of small sample size.

The model was adjusted for cognitive category (normal cognition; cognitive impairment, without dementia; mild, moderate, or severe dementia), sociodemographic characteristics, and chronic medical conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms was estimated according to cognitive category, including severity of dementia, using a nationally representative sample of older adults in the United States, and greater risk for the presence of symptoms was found in those with more advanced cognitive impairment. A greater number of neuropsychiatric symptoms was independently associated with functional limitations in those with CIND and dementia, even after controlling for other potentially confounding factors. Individual neuropsychiatric symptoms that were most strongly associated with functional limitations in those with CIND and dementia were also identified.

The prevalence estimates are comparable with prior population-based estimates, after considering some methodological differences.1,16,17 It was estimated that 57% of those with dementia had at least one neuropsychiatric symptom, which was nearly identical to a prior study that used a similar methodology (56.2%)17 but lower than another study (74.6%),1 probably because two additional common symptoms (sleep difficulties and appetite or eating problems) were included. The estimate of the prevalence of any neuropsychiatric symptom in those with CIND or MCI and normal cognition was also lower than this prior study (44% vs 51% in those with CIND or MCI, 18% vs 27% in those with normal cognition). Agitation, apathy, and aberrant motor behaviors were the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in those with severe dementia and were some of the symptoms that these individuals with difficulty communicating could exhibit and their informants could observe.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between number of neuropsychiatric symptoms and presence of individual symptoms and ADL and IADL limitations and to considering the clinical significance of the symptoms and adjust for cognitive category, including dementia severity. A greater number of neuropsychiatric symptoms may lead to ADL and IADL limitations as a direct consequence of the symptoms themselves, or it is possible that neuropsychiatric symptoms are a reflection of worse cognitive impairment even within cognitive categories. Impairment of executive control functions, which has been suggested as a cause for functional limitations,40–42 may confound this relationship. Other physical illnesses, not controlled for in this study, for example Parkinson’s disease or limb amputation, may be associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression, psychosis, apathy) and ADL limitations. Regarding the association between individual neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional limitations, the findings were somewhat different than in prior studies, again probably because of differences in methodology. Although a prior study found psychosis (delusions and hallucinations) to be associated with more-significant functional limitations,25 the current study found that this relationship was not significant after adjusting for co-occurring neuropsychiatric symptoms and chronic medical conditions. Other symptoms that were independently associated with functional limitations (depression, anxiety, and aberrant motor behaviors) were identified when these symptoms were clinically significant.

The strengths of this study include a nationally representative population-based sample that included the whole spectrum of cognitive function and the use of a well-validated comprehensive assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms. A number of potential limitations should also be considered when interpreting the results. Some remaining nonresponse bias might have affected the analyses despite the use of ADAMS sampling weights, which attempted to account for differential nonresponse. Measurement error for neuropsychiatric symptoms may have occurred even though the NPI has been shown to have good psychometric characteristics.36 ADAMS interviewers assessed the reliability of informants; 83%, 13%, and 1.3% of informants were rated as very reliable, probably reliable, and not reliable, respectively. Assessment of functional limitations may also be subject to measurement error because suboptimal reliability between informant report and directly observed limitations has been suggested in prior studies.43

In summary, neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in older adults with CIND and dementia in the United States and are associated with a significantly higher level of ADL and IADL limitations. Future research aimed at better understanding how neuropsychiatric symptoms affect function may help in the design of interventions to better manage neuropsychiatric symptoms and reduce their burden on patients, families, and the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Aging (NIA) provided funding for the HRS and the ADAMS (U01 AG09740). Dr. Plassman and Dr. Langa were supported by NIA Grant R01 AG027010.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding agencies had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Toru Okura and Kenneth M. Langa: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Brenda L. Plassman, David C. Steffens, and Guy G. Potter: collection of data, study concept and design, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. David J. Llewellyn: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

References

- 1.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2002;288:1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.González-Salvador MT, Arango C, Lyketsos CG, et al. The stress and psychological morbidity of the Alzheimer patient caregiver. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:701–710. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199909)14:9<701::aid-gps5>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logsdon RG, Teri L, McCurry SM, et al. Wandering: A significant problem among community-residing individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53B:294–299. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.5.p294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyketsos CG, Steele C, Baker L, et al. Major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease: Prevalence and impact. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:556–561. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarmeas N, Brandt J, Albert M, et al. Delusions and hallucinations are associated with worse outcome in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1601–1608. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarmeas N, Brandt J, Blacker D, et al. Disruptive behavior as a predictor in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1755–1761. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele C, Rovner B, Chase GA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1049–1051. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, et al. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:403–408. doi: 10.1002/gps.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrmann N, Lanctôt KL, Sambrook R, et al. The contribution of neuropsychiatric symptoms to the cost of dementia care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:972–976. doi: 10.1002/gps.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jönsson L, Eriksdotter Jönhagen M, Kilander L, et al. Determinants of costs of care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:449–459. doi: 10.1002/gps.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore MJ, Zhu CW, Clipp EC. Informal costs of dementia care: Estimates from the National Longitudinal Caregiver Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:S219–S228. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geda YE, Smith GE, Knopman DS, et al. De novo genesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:51–60. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang TJ, Masterman DL, Ortiz F, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with characteristic neuropsychiatric symptoms. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18:17–21. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130–135. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, et al. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: Findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:708–714. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and normal cognitive aging: Population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1193–1198. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, et al. The persistence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: The Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:19–26. doi: 10.1002/gps.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onyike CU, Sheppard JM, Tschanz JT, et al. Epidemiology of apathy in older adults: The Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:365–375. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000235689.42910.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Steinberg M, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease clusters into three groups: The Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1043–1053. doi: 10.1002/gps.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinberg M, Sheppard JM, Tschanz JT, et al. The incidence of mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: The Cache County Study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:340–345. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steffens DC, Maytan M, Helms MJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2005;20:367–373. doi: 10.1177/153331750502000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, et al. Ethnic differences in the prevalence and pattern of dementia-related behaviors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1277–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green CR, Marin DB, Mohs RC, et al. The impact of behavioral impairment of functional ability in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:307–316. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199904)14:4<307::aid-gps908>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, et al. Relationship of behavioral and psychological symptoms to cognitive impairment and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:393–400. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200005)15:5<393::aid-gps120>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mok WY, Chu LW, Chung CP, et al. The relationship between non-cognitive symptoms and functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:1040–1046. doi: 10.1002/gps.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995;30(Suppl):135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health and Retirement Study. [Accessed August 11, 2009];Sample Evolution: 1992–1998 [on-line] Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/surveydesign.pdf.

- 29.Ofstedal MB, Fisher G, Herzog AR. Documentation of Cognitive Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2005. [Accessed December 12, 2008]. [on-line]. Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/docs/userg/dr-006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heeringa SG, Fisher GG, Hurd MD, et al. Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) [Accessed August 29, 2009];Sample Design, Weighting, and Analysis for ADAMS. 2009 [on-line]. Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/ADAMSSampleWeights_Jun2009.pdf.

- 31.Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: Study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:181–191. doi: 10.1159/000087448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale. Alzheimer’s Research Center, Washington University; St. Louis: [Accessed April 29, 2009]. [on-line]. Available at http://alzheimer.wustl.edu/cdr/PDFs/CDR_OverviewTranscript-Revised.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Lyketsos CG, et al. NIMH-CATIE: Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial methodology. Am J Geriatr Psychitry. 2001;9:346–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher GG, Faul JD, Weir DR, et al. Documentation of Chronic Disease Measures in the Heath and Retirement Study (HRS/AHEAD) [on-line] [Accessed December 12, 2008]; Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/docs/userg/dr-009.pdf.

- 39.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic Regression: A Self-Learning Text. 2. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grigsby J, Kaye K, Baxter J, et al. Executive cognitive abilities and functional status among community-dwelling older persons in the San Luis Valley Health and Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:590–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, et al. Declining executive control in normal aging predicts change in functional status: The Freedom House Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlson MC, Fried LP, Xue QL, et al. Association between executive attention and physical functional performance in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54B:S262–S270. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.5.s262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorevitch MI, Cossar RM, Bailey FJ, et al. The accuracy of self and informant ratings of physical functional capacity in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:791–798. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90057-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]