Abstract

HIV transmission may be prevented by effectively suppressing viral replication with antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, adherence is essential to the success of ART, including for reducing HIV transmission risk behaviors. This study examined the association of nonadherence versus adherence with HIV transmission risks. Men (n = 226) living with HIV/AIDS and receiving ART completed confidential computerized interviews and telephone-based unannounced pill counts for ART adherence monitoring. Data were collected between January 2008 and June 2009. Results showed that nonadherence to ART was associated with greater number of sex partners and engaging in unprotected and protected anal intercourse. These associations were not moderated by substance use. The belief that having an undetectable viral load leads to lower infectiousness was associated with greater number of partners, including nonpositive partners, and less condom use. Men who had an undetectable viral load and believed that having an undetectable viral load reduces their infectiousness, were significantly more likely to have contracted a recent STI. Programs aimed at testing and treating people living with HIV/AIDS for prevention require attention to adherence and sexual behaviors.

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) effectively suppresses HIV replication resulting in reduced viral activity and improved health1 and may be generalized to preventing HIV transmission.2 Observational studies of HIV serodiscordant couples have suggested that HIV transmission drops to near zero when infected partners have undetectable viral loads.3 In addition, sustained viral suppression in the absence of other sexually transmitted infections (STI) results in undetectable virus in the genital tract, suggesting significant reductions in HIV transmissibility.4,5 The potential transmission preventive benefits of ART are maximized when infected persons are identified early in the HIV disease process and treatment is initiated immediately. Mathematical modeling suggests that universal HIV testing with immediate initiation of ART could significantly impact HIV incidence.2,6 The potential preventive benefits of testing and treating HIV infection has led to shifts in prevention policy, such as the Swiss Federal AIDS Commission's official statement that people living with HIV/AIDS who have effectively suppressed HIV replication demonstrated by repeated undetectable viral load test results can be considered noninfectious, alleviating concern about HIV transmission.7 In the United States, interventions seek to test every adult in high HIV prevalence cities and initiate immediate ART with persons who test HIV positive. Test and treat models of HIV prevention are promising and are likely to scale up with the continued increase in global access to ART.8

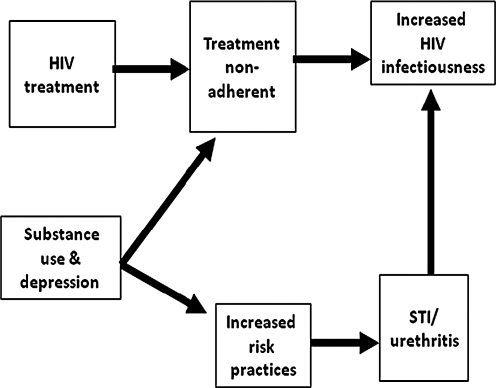

The potential for ART to prevent the spread of HIV will however be undermined by individuals failing to adhere to their medications. Viral suppression, and therefore reduced infectiousness, demands initial adherence of 95% for many cominations of ART9 and requiring at least 80% of doses taken as prescribed for protease inhibitor-boosted regimens.10,12 Figure 1 shows a conceptual framework for the relationship between HIV treatment nonadherence and risk behaviors including the shared behavioral correlates of nonadherence and risk behaviors. Nonadherence to ART increases HIV infectiousness by allowing viral breakthrough in the genital compartment.13 HIV transmission is further amplified when medication nonadherence coincides with exposure to STI and therefore increased genital shedding of HIV.14 The association between medication nonadherence and sexual risk behaviors is at least partially accounted for by shared factors that contribute to both nonadherence and risk behaviors, such as polysubstance use15 and depression.16

FIG. 1.

Factors related to the association between treatment non-adherence and increased HIV transmission risks.

Although the literature is not entirely consistent,17 previous research has supported a relationship between medication nonadherence and HIV transmission risk behaviors. Most studies report that poorer adherence is associated with greater numbers of sex partners and higher rates of unprotected sex.18,19 Unfortunately, past studies have relied on self-report measures of adherence that may share response biases and measurement variance with self-reported sexual behaviors. The methodological limitations of self-reported adherence may explain the inconsistent associations between ART adherence and sexual behavior.

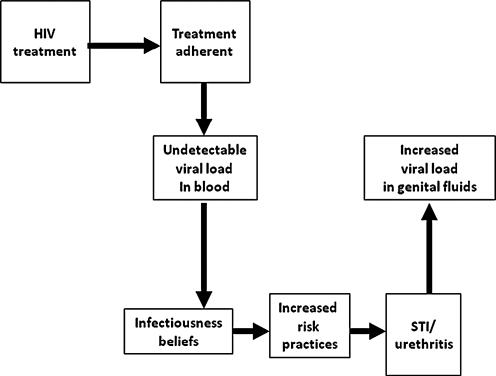

Paradoxically, there is also an association between remaining adherent to ART and increased risk behaviors. Studies show that people who believe that they are less infectious when their blood viral load is undetectable, a result of treatment adherence, reduce condom use and increase unprotected sex.20 In other words, it appears that some individuals who are adherent to ART behaviorally compensate for their perceived lower infectivity by increasing unprotected acts.21 There is clear and compelling evidence that individuals who believe that having an undetectable viral load translates to reduced infectivity consistently engage in higher rates of sexual risk than persons who do not hold such beliefs.22 Figure 2 shows a conceptual framework for the association between ART adherence and increased risk behaviors. Beliefs regarding infectiousness are based on knowing one's peripheral blood viral load which only modestly correlates with viral load in the genital tract.23 Individuals who have an undetectable blood plasma viral load and believe they are less infectious may engage in higher rates of unprotected sex, risking the potential for STI coinfection, which again increases HIV genital shedding and therefore infectiousness.24

FIG. 2.

Factors related to the association between treatment adherence and increased HIV transmission risks.

While there is evidence for the association between both nonadherence and adherence to ART in relation to increases in risk behaviors, to our knowledge no study has simultaneously examined both patterns of adherence in relation to HIV transmission risks. In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that the association between non-adherence to ART and sexual risk behaviors would be accounted for by shared correlates of both adherence and transmission risks, e.g., substance use and depression. Our second hypothesis was that among men who were adherent to medications, risk behaviors would be associated with infectiousness beliefs while controlling for viral load.

Methods

Participants and setting

Participants were 226 men recruited from AIDS service organizations, health care providers, social service agencies, infectious disease clinics and by word-of-mouth in Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta has over 23,000 reported cases of AIDS and an HIV/AIDS rate of 23 per 100,000 population, exceeding the average 15 per 100,000 population in other major U.S. cities. We notified AIDS service providers and infectious disease clinics in Atlanta about the study opportunity. We also placed recruitment brochures in provider's lobbies and waiting areas. Participants were provided with study recruitment brochures that they could use to refer their HIV positive friends to the study. Interested persons phoned our research site to schedule an intake appointment. The study entry criteria were age 18 and proof of positive HIV status using a photo ID with name matching an antiretroviral prescription bottle. Thus, all men in this study were taking HIV treatments. Data were collected between January 2008 and June 2009.

Measures

Assessments were administered using audio-computer-assisted structured interviews (ACASI) and adherence was monitored using unannounced pill counts. For the ACASI, participants viewed assessment items on a 15-inch color monitor, heard items read by machine voice using headphones, and responded by clicking a mouse. Research has shown that ACASI procedures yield reliable responses to sexual behavior interviews.25

Demographic and health characteristics

Participants were asked their age, years of education, income, ethnicity, and employment status. We assessed HIV related symptoms using a previously developed and validated measure of 14 common symptoms of HIV disease.26 Participants indicated whether they had ever been diagnosed with an AIDS-defining condition and their most recent CD4 cell count and viral load.

Sexual risk and protective behaviors

Participants responded to questions assessing their number of male and female sex partners and frequency of sexual behaviors in the previous 3 months. Specifically vaginal and anal intercourse with and without condoms were assessed within seroconcordant (i.e., same HIV status) and serodiscordant (i.e., HIV positive and HIV negative mixed) partnerships. A 3-month retrospective period was selected because previous research has shown reliable reports for numbers of partners and sexual events over this time period.27 Participants were instructed to think back over the past 3 months and estimate the number of sex partners and number of sexual occasions in which they practiced each behavior. The instructions included cues for recollecting behavioral events over the past 3 months.

Sexually transmitted infections

Participants reported whether they had been diagnosed with a non-HIV STI during a 6-month window. Data were collected at the initial assessment for the previous three months and again 3 months later. Participants who indicated that they had been diagnosed with an STI in either of the 3-month time blocks were defined as having a recent STI diagnosis. The 6-month timeframe assured that STI diagnoses overlapped with both sexual risk behaviors and ART adherence. We also assessed which STI participants were diagnosed with and the STI symptoms experienced.

Unannounced pill counts

Participants enrolled in this study consented to monthly unannounced telephone-based pill counts. Unannounced pill counts are reliable and valid in assessing HIV treatment adherence when conducted in participants' homes28 and on the telephone.29 After an office-based training in the pill counting procedure, participants were called at an unscheduled time by a phone assessor. Participants were provided with a free cell phone that restricted use for project contacts and emergency 911. Repeated pill counts occurred over 21- to 35-day intervals and were conducted for each HIV medication participants were taking. Pharmacy information from pill bottles was tracked to verify the number of pills dispensed between calls. Adherence was calculated as the ratio of pills counted relative to pills prescribed and dispensed. Two consecutive pill counts were necessary for computing adherence. The adherence values reported here represent the percentage of pills taken as prescribed following the office-based assessment. Incomplete adherence was defined by 80% of pills taken using unannounced pill counts.

Infectiousness beliefs

Our measure of infectiousness beliefs was adapted from previous research30 and included five items: “People with HIV who take HIV medications are less likely to infect their sex partners during unsafe sex”; “HIV treatments make it easier to relax about unsafe sex”; “It is safe to have sex without a condom when my viral load is undetectable”; “HIV treatments take the worry out of sex”; and “People with an undetectable viral load do not need to worry so much about infecting others with HIV.” Infectiousness belief items were responded to on 6-point scales, 1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree. A mean score composite was created for infectiousness beliefs that was internally consistent (α = 0.74).

Shared correlates of adherence and sexual risks

We measured variables that have demonstrated empirical associations with both HIV treatment adherence and unprotected sexual behavior. Specifically, alcohol use was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a 10 item inventory designed to identify risks for alcohol abuse and dependence.31 The first three items of the AUDIT represent quantity and frequency of alcohol use and the remaining seven items concern problems incurred from drinking alcohol. Scores on the AUDIT range from 0 to 40 and the AUDIT has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.84). Scores of ≥8 indicate high risk for alcohol use disorders and problem drinking. Drug abuse was assessed using the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10). The DAST-10 is an abbreviated version of the original scale, which was designed to identify drug-use related problems in the past year.32 DAST-10 scores range from 0 to 10 and the scale is internally consistent (α = 0.75), has demonstrated time stability and acceptable sensitivity and specificity in detecting drug abuse. Finally, to assess current emotional distress we administered the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).33 Participants were asked how often they had experiences and feelings characteristic of depression in the past 7 days, with responses made on the scale 0 = no days, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, 3 = 5–7 days. The 20-item CES-D is internally consistent (α = 0.79) and yields scores between 0 and 60, with a score of 16 indicating potential depression.

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses were first performed using contingency table χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. To test the first hypothesis regarding the association between nonadherence and sexual behaviors, we conducted logistic regression models to compare persons who were below 80% adherent to ART to those who were 80% or more adherent as measured by unannounced pill counts. Regressions were performed between adherence groups for sex behaviors with all partners and again for sex behaviors only with partners who were not known to be HIV infected (HIV serodiscordant). Because of the low rates of serodiscordant sexual behaviors, we used categorical data (engaged in/not engaged in) for these analyses. To test for potential moderating effects of shared correlates, a second series of regressions was performed after controlling for correlates found significantly associated with adherence in bivariate analyses.

Our second hypothesis concerned the association between infectiousness beliefs and sexual behaviors among men who were adherent to ART. For this analysis, we performed logistic regressions testing the relationship of viral load and sexual behaviors and between infectiousness beliefs and sexual behaviors. Viral load was defined as detectable/undetectable and infectiousness beliefs were dichotomized for those holding and not holding these beliefs. We also tested whether infectiousness beliefs were associated with contracting a recent STI while controlling for current viral load. For all analyses, we defined significance as p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 226 men living with HIV/AIDS completed the study. The majority (91%) of participants were African American, 55% reported current male sex partners, and the mean age was 44.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 6.8). The mean CD4 cell count was 374.6 (SD = 254.9) with 26% of participants having a CD4 count under 200 cells/mm3. Participants were treated with multiple nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) n = 5, 2%), Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI)-based regimens (n = 54, 24%), Protease inhibitors (PIs)-based regimens (n = 31, 14%) and PIs boosted by a pharmacokinetic enhancer (boosted-PI; n = 132, 58%) and four (2%) were receiving multiple combinations of medications (salvage therapy). Fifty-four percent of participants had an undetectable viral load. Fifty-eight participants (26%) were less than 80% adherent to ART. Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants who were adherent and those who were not adherent to treatment. Individuals who were at least 80% adherent to their medications were significantly more likely to have an undetectable viral load and were significantly less likely to demonstrate problem drinking and drug use. There were no additional differences in participant characteristics between adherent and nonadherent groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants Grouped According to their Medication Adherence

| |

Adherent (n = 168) |

Nonadherent (n = 58) |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | |

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 153 | 91 | 52 | 89 | ||

| White | 12 | 7 | 4 | 7 | ||

| Other | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3.3 | 0.34 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Unemployed | 58 | 35 | 18 | 31 | ||

| Employed | 15 | 9 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Disability | 94 | 56 | 38 | 66 | 3.2 | 0.51 |

| Undetectable viral load | 100 | 60 | 22 | 39 | 7.5 | 0.006 |

| STI in past 6 months | 21 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 0.6 | 0.82 |

| Current alcohol use | 83 | 49 | 38 | 66 | 4.5 | 0.03 |

| Current drug use |

45 |

27 |

29 |

50 |

10.5 |

0.001 |

| |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

t |

p |

| Age | 44.5 | 6.8 | 42.8 | 6.7 | 1.6 | 0.10 |

| Education | 12.6 | 2.2 | 12.8 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0.52 |

| CD4 cell count | 388.4 | 251.5 | 328.7 | 263.5 | 1.4 | 0.16 |

| CES-D-depression | 13.6 | 9.7 | 16.3 | 11.1 | 1.6 | 0.10 |

| Drug abuse (DAST) | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.17 |

STI, sexually transmitted infection; SD, standard deviation; CES-D, Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Nonadherence to ART and sexual behaviors

The majority of participants were sexually active and nearly one in three participants reported at least one non-HIV–positive sex partner in the previous 3 months; 50 men (22%) reported 1 and 22 men (10%) reported 2 or more non-HIV–positive sex partner.

Our first hypothesis was partially supported; men who were nonadherent to ART demonstrated higher rates of sexual risk behaviors. Nonadherence was significantly associated with having more sex partners and higher rates of unprotected and condom protected anal intercourse as well as total sexual behaviors in the previous 3 months (Table 2). The associations between treatment adherence and serodiscordant sexual behaviors were not significant. In the moderator analysis, the associations between nonadherence and sexual behaviors were not accounted for by alcohol and drug use.

Table 2.

Associations between Adherence/Nonadherence to Antiretroviral Therapy and Sexual Behaviors

| |

Adherent (n = 168) |

Nonadherent (n = 58) |

Adj |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | OR | p | OR | p | |

| Sex with all partners | ||||||||

| Number of sex partners | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 0.03 | 3.7 | 0.04 |

| Unprotected anal intercourse | 1.3 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 11.9 | 2.3 | 0.04 | 2.3 | 0.05 |

| Anal intercourse with condoms | 1.7 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 12.6 | 3.5 | 0.001 | 3.7 | 0.001 |

| Unprotected vaginal intercourse | 0.5 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.37 | 0.3 | 0.39 |

| Vaginal intercourse with condoms | 1.9 | 5.9 | 1.8 | 8.8 | 1.1 | 0.87 | 1.1 | 0.90 |

| Total sexual behavior | 5.5 | 15.9 | 9.7 | 25.1 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 2.3 | 0.009 |

| Percent condom protected |

69.8 |

40.2 |

70.4 |

35.4 |

1.0 |

0.97 |

1.0 |

0.96 |

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

|

|

| Serodiscordant sexual behaviors | ||||||||

| Any nonpositive partners | 51 | 30 | 21 | 36 | 1.6 | 0.17 | 1.2 | 0.18 |

| Unprotected intercourse | 10 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 2.7 | 0.15 | 2.7 | 0.16 |

| 100% condom use | 32 | 19 | 13 | 20 | 1.4 | 0.20 | 1.4 | 0.24 |

Adjusted odds ratio (Adj OR) = adjusted for CD4 cell count and, alcohol and drug use.

SD, standard deviation.

Adherence to ART and sexual behaviors

Analyses failed to find associations between detectable and undetectable viral load and sexual behaviors among men who were adherent to ART (n = 168, Table 3). As hypothesized, beliefs that ART reduces infectiousness were significantly associated with greater number of sex partners, decreased condom protected intercourse, and greater serodiscordant sex partners. The belief that an undetectable viral load leads to reduced infectiousness was therefore related to increased sexual risks.

Table 3.

Comparisons Between Medication-Adherent Men with Detectable and Undetectable Viral Loads and Endorsing Infectiousness Beliefs on Sexual Behaviors

| |

Detectable viral load |

Undetectable viral load |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Does not endorse infectivity beliefs (n = 37) |

Endorses infectivity beliefs (n = 31) |

Does not endorse infectivity beliefs (n = 47) |

Endorses infectivity beliefs (n = 53) |

Viral load |

Beliefs |

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | OR | p | OR | p | |

| Number of partners | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 0.45 | 7.9 | 0.01 |

| Unprotected intercourse | 5.1 | 14.4 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 0.42 | 0.8 | 0.38 |

| Intercourse with condoms |

4.2 |

12.6 |

2.1 |

0.9 |

7.9 |

25.9 |

3.3 |

8.6 |

0.5 |

0.08 |

0.4 |

0.01 |

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

|

|

| Nonpositive partners | 12 | 32 | 16 | 52 | 16 | 34 | 27 | 51 | 3.0 | 0.09 | 3.7 | 0.04 |

| Discordant unprotected intercourse | 2 | 5 | 6 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 1.5 | 0.51 | 2.9 | 0.21 |

SD, standard deviation; OR, odds ratio.

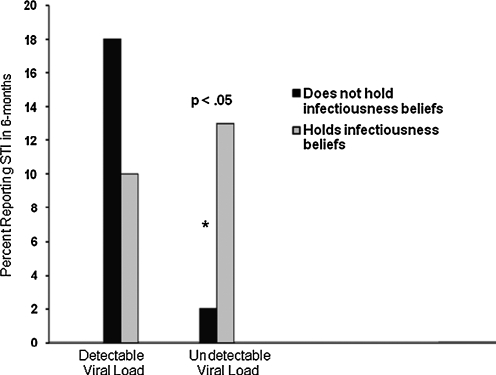

Finally, we examined infectivity beliefs in association with recently contracting an STI while controlling for viral load status and ART adherence. Among adherent men with detectable viral loads (n = 68), there was no difference in having contracted STIs for men who did not endorse infectiousness beliefs (n = 7, 10%) and men who did endorse infectiousness beliefs (n = 3, 4%), χ2(1) = 1.1, not significant. However, infectiousness beliefs were significantly associated with STI among adherent men who had undetectable viral loads (n = 100); men who had undetectable viral loads and endorsed infectiousness beliefs were significantly more likely to have had an STI (n = 7, 7%) compared to men with undetectable viral loads who did not endorse infectiousness beliefs (n = 1, 1%), χ2(1) = 4.2, p < 0.05 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Sexually transmitted infections among medication adherent men with detectable and undetectable viral loads as a function of holding infectiousness beliefs. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The current study found that factors relevant to both ART nonadherence and adherence are important in understanding high-risk sexual behaviors among men living with HIV/AIDS. Consistent with past research we found that nonadherence to ART was associated with sexual behaviors and substance use. However, our first hypothesis was not fully supported as we found that depression was not associated with adherence and substance use did not account for the association between nonadherence to ART and sexual behaviors. Thus, while alcohol and drug use may contribute to multiple risk behaviors, there was no evidence that substance use itself accounts for the relationship between treatment nonadherence and sexual risks. While it is possible that other unmeasured individual difference variables could be acting to promote both adherence and sexual behaviors, it is also possible that the two behaviors are directly rather than indirectly associated; i.e., nonadherence and sexual risk behavior may be members of the same cluster of health compromising behaviors in a subgroup of men living with HIV/AIDS.

With respect to our second hypothesis concerning the association between adherence and sexual risks, we found that infectiousness beliefs were significantly associated with greater numbers of sex partners, less condom use, and a greater likelihood of having HIV serodiscordant sex partners. Also consistent with past research, we did not observe an association between viral load and sexual behaviors.22 Beliefs regarding viral load, rather than viral load itself, influence behavior.34 Importantly, having recently contracted an STI occurred significantly more for men who had an undetectable viral load and endorsed beliefs that an undetectable viral load renders them less infectious. This finding warrants particular attention because men who have contracted other STI were likely far more infectious than they could possibly know from their peripheral blood viral load.35

The current findings should be interpreted in light of their methodological limitations. Although we used reliable computerized interviews to collect sexual behavior data, our behavioral measures nevertheless relied on self-report and may have been influenced by social desirability biases. For example, our treatment beliefs measure may have induced or reinforced the belief that treatments reduce infectiousness. The behavioral risks that we observed should therefore be considered lower-bound estimates of HIV transmission risks among men living with HIV/AIDS. We also measured STI coinfection using self-reports that are limited by relying on recall, socially desirable responding, and awareness of STI symptoms. Our community sample of men living with HIV/AIDS prohibited access to multiple clinics for medical records to confirm STI diagnoses. We also did not collect biological specimens for STI confirmation because point prevalence estimates do not confirm broader intervals of diagnoses. Our study was conducted with a convenience sample recruited in one city in the southeastern United States, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other populations in other regions. With these limitations in mind, we believe that the current findings have important implications for the implementation of test-and-treat programs for HIV prevention.

Use of ART to reduce HIV infectiousness is an important advance in HIV prevention. ART is currently available and could have a significant impact on efforts to stem HIV epidemics. Existing research shows that individuals behaviorally compensate by reducing condom use when they believe that they are less infectious.15,16,28,29 The current results add to the literature by showing, for the first time, that infectiousness beliefs are associated with contracting a new STI. These findings offer further evidence that failure to address behavioral risk compensation following an undetectable viral load among men who hold infectiousness beliefs will undermine test and treat programs. In addition, failure to invest in aggressive detection and treatment of incident STI in people living with HIV/AIDS will undermine test-and-treat HIV prevention programs. Worse still, increased risks for STI among people who believe they are less infectious will have unforeseen adverse effects by facilitating HIV transmission. The behavioral consequences of testing and treating HIV for prevention must therefore be addressed if these new programs are to succeed.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R01-MH71164 and R01-MH82633.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Collaboration H-C. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:123–137. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granich RM. Gilks CF. Dye CBG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: A mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinn TC. Wawer MJ. Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernazza PL. Gilliam B. Dyer JR, et al. Quantification of HIV in semen: Correlation with antiviral treatment and immune status. AIDS. 1997;11:987–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vernazza P. Hirschel B. Bernasconi E. Flepp M. HIV transmission under highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2008;372:1806–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boily MC. Bastos FI. Desai K. Masse B. Changes in the transmission dynamics of the HIV epidemic after wide-scale use of antiretroviral therapy could explain increases in sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:100–113. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000112721.21285.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernazza P. Les personnes séropositives ne souffrant d'aucune autre MST et suivant un traitment antirétroviral efficace ne transmettent pas le VIH par voie sexuelle. Suisse Bull Méd. 2008;89:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieffenbach CW. Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301:2380–2382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterson DL. Swindells S. Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bangsberg DR. Kroetz DL. Deeks SG. Adherence-resistance relationships to combination HIV antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenblum M. Deeks SG. van der Laan M. Bangsberg DR. The risk of virologic failure decreases with duration of HIV suppression, at greater than 50% adherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parienti JJ. Das-Douglas M. Massari V, et al. Not all missed doses are the same: Sustained NNRTI treatment interruptions predict HIV rebound at low-to-moderate adherence levels. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashuba AD. Dyer JR. Kramer LM, et al. Antiretroviral-drug concentrations in semen: implications for sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1817–1826. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson LF. Lewis DA. The effect of genital tract infections on HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:946–959. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181812d15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mimiaga MJ. Reisner SL. Vanderwarker R, et al. Polysubstance use and HIV/STD risk behavior among Massachusetts men who have sex with men accessing Department of Public Health mobile van services: Implications for intervention development. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:745–751. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalichman SC. Co-occurrence of treatment nonadherence and continued HIV transmission risk behaviors: Implications for positive prevention interventions. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:593–597. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181773bce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamond C. Richardson JL. Milan J, et al. Use of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy is associated with decreased sexual risk behavior in HIV clinic patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalichman SC. Rompa D. HIV Treatment adherence and unproected sex practices among persons receiving antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:59–61. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson TE. Barron Y. Cohen M, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its association with sexual behavior in a national sample of women with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:529–534. doi: 10.1086/338397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC. Rompa D. Austin J, et al. Viral load, perceived infectivity, and unprotected intercourse. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28:303–305. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200111010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eaton LA. Kalichman S. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: Implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crepaz N. Hart T. Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and high risk sexual behavior: A Meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292:224–236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman SC. DiBerto G. Eaton L. HIV viral load in blood plasma and semen: Review and implications of empirical findings. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:55–60. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e318141fe9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson LF. Lewis D. The effect of genital tract infections on HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:946–959. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181812d15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gribble JN. Miller H. Rogers S. Turner CF. Interview mode and measurement of sexual and other sensitive behaviors. J Sex Res. 1999;36:16–24. doi: 10.1080/00224499909551963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalichman SC. Ramachandran B. Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Napper LE. Fisher DG. Reynolds GL. Johnson ME. HIV risk behavior self-report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bangsberg DR. Hecht FM. Charlebois ED. Chesney M. Moss A. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS Behav. 2001;5:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalichman SC. Amaral CM. Cherry C, et al. Monitoring antiretroviral adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: Reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9:298–308. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalichman SC. Eaton L. Cain D, et al. HIV Treatment beliefs and sexual transmission risk behaviors among hiv positive men and women. J Behav Med. 2006;29:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders JB. Aasland OG. Babor TF. DeLaFuente JR. Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addictions. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skinner H. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psych Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eaton LA. Kalichman SC. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: Implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen MS. Hoffman IF. Royce RA, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: Implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. Lancet. 1997;349:1868–1873. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]