Abstract

Aim

To describe long-term prescribing patterns of osteoporosis therapy before and after the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) publication.

Methods

We conducted a time-series analysis from 1997 to 2005 using nationally representative data based on office-based physician and hospital ambulatory clinic visits. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were conducted using chi-square tests and logistic regression, respectively, and trends in the prevalence of osteoporosis therapies were evaluated per 6-month (semiannual) intervals. Linear regression and graphic techniques were used to determine statistical differences in the prevalence trends between the two periods.

Results

Overall prevalence of therapeutic or preventive osteoporosis therapy was similar between the WHI periods. However, a significant decrease in estrogen therapy and increases in bisphosphonates, calcium/vitamin D were observed in the period after the WHI publication (p < 0.05). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed older age and white race were associated with a higher likelihood of antiosteoporosis medication (AOM) prescription, and Medicaid insurance type was associated with a lower likelihood of an AOM prescription. Excluding calcium/vitamin D, nonestrogen therapy was more likely to be prescribed in the after-WHI period (office-based physician clinic: [adjusted OR, aOR] 2.49 [2.04–4.04]; hospital-based clinic: aOR 2.42 [1.67–7.50]) Nonestrogen therapy was more prevalent in visits made by older women, women of white race, women with contraindicated conditions for estrogen therapy, and women from the Northeast region.

Conclusions

After the WHI publication, the overall prevalence of osteoporosis therapy did not change; however, a shift from estrogen to nonestrogen therapy was observed after the WHI publication. Black women were less likely to receive nonestrogen antiosteoporosis therapy in hospital-based clinics.

Introduction

The findings from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study, published in July 2002, established that hormone therapy containing estrogen plus progestin increased postmenopausal women's risk of breast cancer, stroke, and myocardial infarction (MI).1 Although the study reported positive effects of hormone therapy on hip fractures, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a labeling change, including a statement that hormone therapy should be considered only for women at significant risk of osteoporosis who cannot take nonestrogen medications.2

The WHI findings were in contrast to previously published observational studies that had demonstrated a potential cardiovascular benefit from the use of these medications, and it was anticipated that shifts to nonestrogen therapeutic agents for osteoporosis management would occur based on the strength of the WHI clinical trial data. Several studies have documented changes in patterns of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy after the WHI publication from self-report, automated pharmacy data, Medicaid administrative data, and other national-level data sources.3–22 Based on research findings, both declines in hormone therapy and switches to lower-dose hormone therapy and other alternative antiosteoporosis medications (AOM) occurred after July 2002.

Despite the wealth of evidence showing changing patterns of osteoporosis management, most studies have focused on reporting an immediate impact of the WHI findings, very few studies used national-level data, and even fewer studies have documented differences in trends by U.S. clinical setting. Thus, the primary goal of this study was to evaluate the long-term impact of the WHI studies on trends in osteoporosis therapy from 1997 to 2005 using two national-level ambulatory care databases.

Materials and Methods

Data sources and study population

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) were used in this study. The data collected from these two surveys provide an analytical base that serves as an important tracking tool for national trends in ambulatory care use, medication use, and practice patterns.23–25 The NAMCS and NHAMCS use a multistage probability sampling design of all ambulatory office visits to physicians engaged in office-based patient care (NAMCS) and hospital-based outpatient care(NHAMCS).23–25 Also included in the survey data are NCHS-provided patient visit weight variables to enable extrapolation of statistics derived from nationally representative estimates through weighted analysis.

NAMCS data are collected and recorded by physicians assisted by office staff, whereas NHAMCS information is gathered by hospital staff from medical records abstraction. To ensure completeness of data collection, NCHS field staff conduct training activities beforehand on the appropriate filling of patient record forms for both NAMCS and NHAMCS. The variables included in the surveys are sociodemographic information (i.e., age, race, sex, geographic region), diagnoses, and medications prescribed, provided, or continued by the physician at that visit. Data on the insurance status of patients are collected as expected payment type, including private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, worker's compensation, self-pay, no charge/charity, and other insurance types, such as the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS), state-provided and local government-provided insurance, private charitable organizations, and other liability insurance (e.g., automobile collision policy coverage).

Visits made by women aged ≥ 40 years to office-based physician and hospital ambulatory clinics between January 1997 and December 2005 were included in the analysis. The age group ≥ 40 years was selected for our study because the age at menopause ranges from 40 to 58 years.26

Target drugs and clinical conditions

The primary objective of this study is to describe overall changes in osteoporosis therapy over the years (i.e., either prevention or treatment of osteoporosis). We made an operational definition of AOM visit as a visit where one or more of the following medications were recorded as being prescribed, provided, or continued to be used during a patient visit: estrogen replacement therapy (estrogen or estrogen combinations with progesterone or androgen), estrogen-containing oral contraceptive (OC) pills (excluding those containing progestins alone), bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, etidronate, pamidronate, ibandronate, tiludronate, and zoledronic acid), calcitonin, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (raloxifene), teriparatide, calcium supplements, and vitamin D. Although the FDA has approved only bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, and ibandronate), salmon calcitonin, estrogen, raloxifene, and teriparatide hormone for osteoporosis therapy, our definition includes non-FDA-approved bisphosphonates and other AOM in order to evaluate potential benefits from all types—not just FDA-approved types—of AOM on bone.

Indicated clinical conditions for AOM therapy included diagnoses of osteoporosis and fragility fracture; contraindicated clinical conditions for estrogen therapy included diagnoses of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, and thromboembolic disease.

Estimation of prevalence of AOM-related visits

The prevalence of AOM-related visits was estimated at 6-month (semiannual) intervals from January 1997 to December 2005. Each estimate represented the proportion of ambulatory care visits associated with an AOM prescription among the total ambulatory care visits occurring within that 6-month period. A total of 18 point estimates were calculated during the entire study period. To further evaluate differences in prevalence by WHI study period, the point estimates calculated from January 1997 to June 2002 (points 1–11) were included in the before-WHI period, and those computed from July 2002 to December 2005 (points 12–18) were assigned to the after-WHI period. Comparison of AOM-related visits was subsequently performed on the basis of these two time periods.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations (SD), and frequency distributions, were calculated and reported to determine the patient visit characteristics of the study population. A time-series analysis was conducted to evaluate osteoporosis therapy before and after the publication of the WHI study. Changing patterns in the prevalence of AOM therapies before and after WHI were first evaluated graphically using the 6-month prevalence point estimates obtained for overall AOM and by AOM class over the entire study period. The average of the 6-month point estimates was used to report the mean difference in the prevalence of AOM therapies before and after the WHI publication. Simple linear regression analyses were conducted to compare changes in slopes of the AOM visit prevalence between the two time periods overall and for each drug class. Student's t tests were conducted to compare overall changes in mean prevalence of AOM therapies before and after the WHI publication.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis, using only the subset of visits associated with any AOM (calcium and vitamin D excluded), was conducted to evaluate the factors predicting the use of nonestrogen AOM therapy (i.e., bisphosphonate, SERM, calcitonin, or teriparatide hormone). Variables included in the model were demographics, insurance type, WHI period, physician's specialty, and presence of contraindicated clinical conditions to estrogen therapy.

National visit estimates were extrapolated from prevalence calculated from the sampled visits in the databases using the NCHS-provided patient visit weight variables. Variances around the estimates were computed using variables related to stratum and cluster after weighting procedures from each national survey to take into account the complex survey design. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (Cary, NC), and graphs were constructed using R 2.1.0 software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Visit characteristics

From 1997 to 2005 A total of 78,807 and 79,034 visits of women ≥ age 40 were identified from NAMCS and NHAMCS, respectively, representing a national estimate of 2.7 billion visits in the office-based physician setting and 220.0 million visits in the hospital-based ambulatory care setting. Table 1 shows the visit characteristics of our study population. The majority of the patients were white women, at least 1% of them had an osteoporosis or fragility fracture diagnosis, and about 10% were associated with AOM. The prevalence of AOM therapy related to osteoporosis treatment among patients with osteoporosis/fragility fracture diagnoses was 59.6% in the office-based physician setting and 58.9% in the hospital-based clinic.

Table 1.

Visit Characteristics of Women Aged ≥ 40 Years in Ambulatory Care, 1997–2005

| Characteristic | Office-based physician setting | Hospital-based clinic |

|---|---|---|

| Number of total visits (in millions)a | 2,714.2 | 220.0 |

| Mean age (years) | 61.6 | 59.0 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 87.0 | 74.9 |

| Black | 9.4 | 21.6 |

| Other | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Geographic region (%) | ||

| Northeast | 21.5 | 29.1 |

| Midwest | 21.5 | 25.5 |

| South | 35.4 | 33.6 |

| West | 21.6 | 11.8 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) (%) | ||

| MSA | 84.5 | 82.0 |

| Non-MSA | 15.5 | 18.0 |

| Insurance type (%) | ||

| Otherb | 12.1 | 19.3 |

| Private | 47.8 | 33.5 |

| Medicare | 5.2 | 17.9 |

| Medicaid | 35.0 | 29.3 |

| Physician specialty | ||

| IM | 21.6 | Data not available |

| OBGYN | 7.3 | |

| Cardiologist | 3.3 | |

| GP/FP | 23.8 | |

| Other | 43.9 | |

| Osteoporosis/fracture diagnosisc | ||

| Yes | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| No | 98.7 | 98.9 |

| Antiosteoporosis medicationd | ||

| Yes | 10.9 | 9.9 |

| No | 89.1 | 90.1 |

Weighted visit estimates in millions from 1997 to 2005.

Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS), state-provided and local government-provided insurance, private charitable organizations, workers's compensation, self-pay, and other liability insurance (e.g., automobile collision policy coverage).

ICD-9 cm code of 733.0x for osteoporosis and 733.1x for fracture.

Antiosteoporosis medications include estrogens, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), teriparatide, calcium, and vitamin D that are prescribed, taken, or continued during a patient visit.

IM, internal medicine; OBGYN, obstetricians/gynecologists; GP/FP, general or family practitioners.

Trends in AOM prevalence

Based on a weighted analysis, an estimated 1 in 10 visits was associated with at least one AOM prescription in both the office-based physician and public ambulatory care settings, with a slightly higher prevalence of AOM prescriptions in the office-based physician setting (10.9% vs. 9.9%, OR 1.05(1.01–1.09), p = 0.009) (Table1). The mean difference in the overall AOM prevalence between the two WHI periods was not statistically significant for both settings (Table 2). However, findings related to AOM prevalence by drug class showed a significant decrease in the prevalence of estrogen therapy (p < 0.05), with 38% and 54% observed changes between the two periods in the office-based physician setting and hospital-based clinic, respectively (an average reduction of 46%). A significant increase in bisphosphonates was observed (> 2-fold increases) between the two periods (p < 0.05). Similar increases were observed for visits associated with calcium and vitamin D (p < 0.05) in the after-WHI period (Table 2). No significant changes for other AOM types, including calcitonin, teriparatide hormone, and SERM were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Mean Prevalence of Antiosteoporosis Medication Before and After Women's Health Initiative Study

| |

Office-based physician setting |

Hospital-based clinic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before WHI % ± SE | After WHI % ± SE | Before WHI % ± SE | After WHI % ± SE | |

| AOM | 8.25 ± 0.31 | 8.80 ± 0.48 | 8.42 ± 0.40 | 7.89 ± 0.37 |

| Estrogens | 6.26 ± 0.22 | 3.85 ± 0.21a | 5.94 ± 0.39 | 2.74 ± 0.15a |

| Bisphosphonates | 0.93 ± 0.14 | 2.61 ± 0.35a | 0.85 ± 0.11 | 2.17 ± 0.21a |

| Calcium | 1.37 ± 0.13 | 2.73 ± 0.27a | 1.99 ± 0.15 | 3.15 ± 0.35a |

| Vitamin D | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 1.17 ± 0.19a | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 1.31 ± 0.17a |

| Otherb | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.10 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

Antiosteoporosis medications (AOM) include estrogens, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), teriparatide, calcium, and vitamin D that are prescribed, taken, or continued during a patient visit.

Means were generated using unweighted estimates; each estimate represents the mean of the individual 6-month interval, AOM prevalence estimates: proportion of AOM visits in 6-month interval/total ambulatory care visits occurring within a 6-month interval.

p < 0.05 between, before and after WHI.

Other includes calcitonin, teriparatide, and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM).

SE, standard error; WHI, Women's Health Initiative.

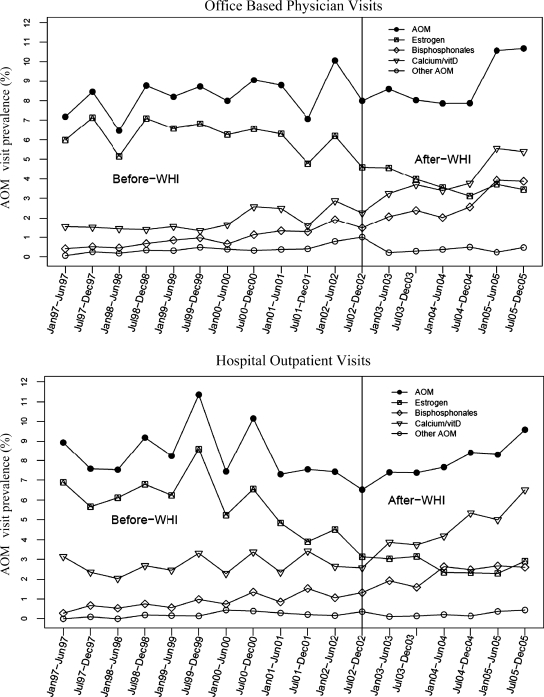

As shown in Figure 1, the overall AOM prevalence remained relatively stable in both settings in the before and after WHI periods. This finding is also confirmed by the lack of significance in the slope differences shown in Table 3. On the other hand, marked changes were observed by type of AOM, particularly of bisphosphonates, with trends of increased prescribing apparent as early as 1999. These observed findings were confirmed by statistically significant slope changes in the prevalence of bisphosphonates in both ambulatory care settings (Table 3). The prevalence of estrogen in the after-WHI period showed a decreasing pattern of use compared with the before-WHI period; however, slope differences between periods did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). Increasing trends of calcium/vitamin D therapies, as illustrated by increasing slopes during the after-WHI period in both settings, were also statistically significant.

FIG. 1.

Semiannual changes in antiosteoporosis medication (AOM)-related visit prevalence in the office-based physician (Top) and hospital-based clinic (Bottom) settings. The denominator for each point estimate is the total number of patient visits within a 6-month interval. AOM, Antiosteoporosis medications include estrogens, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), teriparatide hormone, calcium, and vitamin D that are prescribed, taken, or continued during a patient visit.

Table 3.

Differences in Antiosteoporosis Medication Prevalence Slope Values Before and After Women's Health Initiative Study in Office-Based Physician Setting and Hospital-Based Clinics

| |

Office-based physician setting |

Hospital-based clinic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before WHI | After WHI | Before WHI | After WHI | |

| AOM | 0.15 | 0.42 | − 0.07 | 0.43 |

| Estrogen | − 0.06 | − 0.21 | − 0.22 | − 0.11 |

| Bisphosphonate | 0.13 | 0.39* | 0.09 | 0.22* |

| Calcium/vitamin D | 0.11 | 0.50* | 0.03 | 0.56* |

| Othera | 0.04 | − 0.05* | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Antiosteoporosis medications (AOM) include estrogens, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), teriparatide, calcium, and vitamin D that are prescribed, taken, or continued during a patient visit.

p < 0.05.

Other includes calcitonin, SERM, and teriparatide.

Predictive factors of nonestrogen therapy among AOM users

Findings from the model predicting nonestrogen therapy among AOM-related visits are shown in Table 4. Visits during the after-WHI period were at least two times more likely to be associated with a nonestrogen prescription in both settings. Older women were more likely to receive nonestrogen therapy compared with those aged 40–49 years. Black women were less likely to receive a nonestrogen prescription than white women in the hospital setting (aOR 0.57 [0.40–0.80]) (Table 4). Having a contraindicated condition for estrogen therapy was the strongest predictor of receiving a nonestrogen AOM regardless of clinical setting: office-based physician: aOR 2.36 (1.25–5.47); hospital: aOR 4.76 (2.70–0.38) (Table 4). Medicare patients were more likely to have nonestrogen therapy compared with those from private insurance holders: office-based physician: aOR 1.44 (1.17–7.77); hospital: OR 2.03 (1.39–9.98)) (Table 4). Patients with other insurance types, including CHAMPUS, state-provided and local government-provided insurance, private charitable organizations, workers's compensation, self-pay, and other liability insurance (e.g., automobile collision policy), were less likely to receive nonestrogen therapy than private insurance holders (aOR 0.51 [0.30–0.87]) in the hospital setting (Table 4). There were significant regional differences in the likelihood of being prescribed a nonestrogen AOM; the Northeast region was highly associated with receiving a prescription in the office-based physician setting, but the West region was less likely to be associated with nonestrogen therapy compared with the Northeast region in the hospital-based setting.

Table 4.

Likelihood of Nonestrogen Therapy (Estrogen Therapy as Reference) Among Antiosteoporosis Medication Visits, Excluding Calcium and Vitamin D, Using Weighted Estimates

| |

Office-based physician |

Hospital-based clinic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Womens Health Initiative | ||||

| Before | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| After | 2.72 (2.26–6.28)* | 2.49 (2.04–4.04)* | 2.51 (1.73–3.67)* | 2.42 (1.67–7.50)* |

| Age, years | ||||

| 40–49 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50–59 | 2.57 (1.80–0.67)* | 2.37 (1.65–5.39)* | 1.55 (0.95–5.53) | 1.77 (1.06–6.96)* |

| 60–69 | 5.30 (3.68–8.63)* | 3.83 (2.59–9.66)* | 3.09 (1.86–6.12)* | 3.40 (1.96–6.88)* |

| ≥ 70 | 12.68 (9.02–27.85)* | 7.16 (4.84–40.57)* | 6.04 (3.89–9.37)* | 5.96 (3.42–20.38)* |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.76 (0.51–1.12) | 0.69 (0.43–3.12) | 0.54 (0.39–9.76)* | 0.57 (0.40–0.80)* |

| Other | 1.36 (0.81–1.28) | 1.12 (0.70–0.81) | 1.12 (0.68–8.86) | 1.00 (0.57–7.77) |

| Physician specialty | ||||

| GP/FP | 1.00 | 1.00 | Data not available | Data not available |

| IM | 1.71 (1.30–0.24)* | 1.38 (1.05–5.81)* | ||

| OBGYN | 0.32 (0.23–3.45)* | 0.45 (0.31–1.64)* | ||

| Cardiologist | 1.35 (1.04–4.74)* | 0.85 (0.65–5.12) | ||

| Other | 1.52 (1.19–9.94)* | 1.16 (0.89–9.52) | ||

| Contraindication for estrogen therapya | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 3.03 (1.82–2.04)* | 2.36 (1.25–5.47)* | 4.40 (2.57–7.50)* | 4.76 (2.70–0.38)* |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicare | 3.74 (3.17–7.41)* | 1.44 (1.17–7.77)* | 2.03 (1.39–9.98)* | 0.98 (0.59–9.62) |

| Medicaid | 2.29 (1.49–9.50)* | 1.54 (0.96–6.49) | 0.94 (0.63–3.41) | 0.76 (0.49–9.18) |

| Otherb | 1.05 (0.75–5.45) | 0.93 (0.67–7.30) | 0.39 (0.23–3.66)* | 0.51 (0.30–0.87)* |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Midwest | 0.56 (0.39–9.80)* | 0.50 (0.37–7.68)* | 1.05 (0.68–8.62) | 0.91 (0.59–9.62) |

| South | 0.54 (0.40–0.73)* | 0.53 (0.39–9.71)* | 0.66 (0.37–7.15) | 0.62 (0.38–8.00) |

| West | 0.57 (0.41–1.81)* | 0.51 (0.36–6.71)* | 0.59 (0.39–9.90)* | 0.56 (0.38–8.82)* |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | ||||

| Non-MSA | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| MSA | 1.38 (1.01–1.87)* | 1.57 (1.20–0.05)* | 1.20 (0.76–6.89) | 1.61 (0.94–4.75) |

p < 0.05.

Contraindicated conditions for estrogen therapy: ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer and thromboembolic disease.

Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS), state-provided and local government-provided insurance, private charitable organizations, self-pay, workers compensation, and other liability insurance (e.g., automobile collision policy coverage).

CI, confidence interval; GP/FP, general/family practitioner; IM, internal medicine; OBGYN, obstetricians/gynecologists; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This study evaluated the national trends of osteoporosis therapy from 1997 to 2005 in the ambulatory care setting and further examined them in the context of the publication of the WHI study.1 Based on these objectives, the major findings indicate that after publication of the WHI study, the following prescribing patterns were observed among ambulatory care visits (1) the overall AOM prevalence remained the same, (2) the prevalence of estrogen prescriptions declined, (3) the prevalence of bisphosphonates, vitamin D, and calcium increased, and (4) visits made by black women were less likely to be associated with nonestrogen therapy than those of other racial groups in the hospital setting.

Our findings on patterns of AOM prevalence after the WHI publication were similar to those in the published literature,3–22 indicating that the prevalence of estrogen use declined by 29%–69% and bisphosphonate use increased by about 18%. Our study found a similar decrease in the prevalence of visits associated with estrogen prescription (46% reduction), but in contrast to those studies, we found a more than 2-fold increase in bisphosphonate-related visits after the WHI publication. This variability could have been influenced by differences in study periods of interest (short-term vs. long-term change), study population and location, unit of analysis (i.e., prescriptions, claims, patients vs. visits), and clinical settings (hospital, self-report, ambulatory care). Regardless of the potential reasons for the variability, however, the reviewed literature studies all show trends in switching from estrogen to nonestrogen AOM modalities in the clinical setting after publication of the WHI report.

Our data showed steady increases in bisphosphonate prescribing as early as 1999. These findings suggest that other extraneous factors, in addition to the WHI publication, could have impacted the prevalence change in bisphosphonate prescribing over time. We believe that these findings largely correlate with improved marketing strategies within the life span of the approved bisphosphonate class of medications. Findings from the 2001 Intercontinental Marketing Services (IMS) survey of the U.S. selected osteoporosis market showed that bisphosphonate held a higher market share than estrogens (35.3% vs 32.8%).27 Similarly, data from 1998 reported alendronate among the 100 promoted drugs.28

Widespread media coverage and the publication's prerelease before July 2002 could have triggered changes in prescribing patterns months before the publication date of the WHI study, as shown from trends in our study findings. However, the interesting findings seem to be related to persistent increases in prescribing bisphosphonates on a long-term basis, as observed in our study. Bisphosphonates are notably the mainstay of osteoporosis therapy.17 Nevertheless, issues related to low compliance because of an inconvenient dosing regimen (i.e., daily vs. weekly or monthly), gastrointestinal symptoms, difficulty in dosing instructions, and the rare side effect of osteo-necrosis of the jaw have been raised.29,30 In fact, prior studies using data from the late 1990s reported compliance with bisphosphonates was as low as 50%.31–33 As of 2001, when the first weekly dose of alendronate was introduced into the market, significant declines in discontinuation rates have been reported in the literature, with increased compliance with weekly and monthly dosing over daily dosing.34,35 Given this evidence, it is plausible that the steady introduction of more convenient dosing has contributed to the increased use of bisphosphonates.

National guidelines and recommendations also could have contributed to the greater prescribing of bisphosphonate therapy over estrogen therapy after the WHI publication. The guidelines for the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommended the use of estrogen at the lowest dose and duration possible in its 2003 update.36 Therefore, the national guidelines, as well as the WHI publication, could have influenced the AOM prescribing behavior observed during our study period. Although the data we used ended in 2005, it is anticipated that these trends will continue, based on the most recent updates from the North American Menopause Society position statement in 200837 and the National Osteoporosis Foundation,38 both of which have emphasized bisphosphonates as first-line therapy in osteoporosis management. We still believe, however, that a major clinical trial, such as the WHI study,1 could impact long-term changes in osteoporosis therapy beyond the factors of heavy marketing, improved dosing, potentially direct consumer advertisement, and national guideline changes for bisphosphonates, as the observed changes were not limited to bisphosphonates but to a consistent reduction in estrogen therapy.

Our findings indicating the lower likelihood of nonestrogen therapy in visits by black women are of interest in the hospital setting, particularly given the already documented low prevalence of AOM use in black women.39–43 Most relevant to our findings was a study by Farley et al.,20 who evaluated the racial variability before and after the WHI publication using 2002 and 2003 national data. They reported a significantly lower prescribing rate of AOM and newer AOM therapies among blacks. It is not clear from the literature which factors are responsible for this effect; however, our findings suggest variations in clinicians' practice patterns between two clinical settings. Future studies are needed to better assess factors for racial variability and ways in reducing gaps in the provision of osteoporosis therapy.

Limitations

The use of national surveys in this study warrants caution when interpreting these findings. First, these data cannot confirm a change in prescription from estrogen to another form of AOM on an individual visit profile. They can only demonstrate an overall shift in prescribing from estrogen to nonestrogen therapies based on a sample of national visits. The second limitation related to our analysis of ambulatory visits pertains to our inability to control for clinical, social, and temporal factors that could potentially affect patterns of osteoporosis medication use. It is especially true that important extraneous factors other than WHI, such as direct to consumer marketing of bisphosphonates or overall raised awareness of osteoporosis, could have influenced AOM prescribing behavior. In addition, such variables as personal preferences, drug history, disease history, bone mineral density, and drug coverage status of the patient are not included in the data source.

Survey instrument limitations introduce the possibility of truncated drug use records among visits with high prescribing volume. Physicians participating in NAMCS and NHAMCS coded up to six medications until 2002 and up to eight medications from 2003. Consequently, there is a potential possibility for truncation of records among the elderly who may be on several concomitant medications. We attempted to quantify the potential for this bias by evaluating the proportion of the maximum number of medication records each year. We found that the potential for truncation is < 10% and, therefore, had a minimal effect on our findings. Specifically 93.1% of the visits in the office-based physician setting had between 0 and five medications prescribed until 2002, and 94.0% of them were prescribed 0 to seven medications after 2002. Similarly, in the hospital setting, 89.7% of the visits had between 0 and five medications prescribed, and 92% of the visits had between 0 and seven medications prescribed the during respective time periods.

Conclusions

After publication of the WHI results,1 the overall prevalence of AOM prescriptions did not decline. However, clinic visits with prescriptions associated with estrogen AOM decreased, and those with nonestrogen AOM increased. Black women were less likely to receive nonestrogen therapy in the hospital setting. Our findings suggest that this major clinical trial affected long-term changes in AOM prescribing patterns in U.S. ambulatory care settings at the national level.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation and grant 1R24HS11673 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Disclosure Statement

I.H.Z. is principal investigator on a grant to the University of Maryland, funded by Merck.

The authors have no other conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Rossouw JE. Anderson GL. Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prempro® package insert. www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/ [Jul 1;2009 ]. www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/

- 3.Hillman JJ. Zuckerman IH. Lee E. The impact of the Women's Health Initiative on hormone replacement therapy in a Medicaid program. J Womens Health. 2004;13:986–992. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majumdar SR. Almasi EA. Stafford RS. Promotion and prescribing of hormone therapy after report of harm by the Women's Health Initiative. JAMA. 2004;292:1983–1988. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntosh J. Blalock S. Effects of media coverage of Women's Health Initiative study on attitudes and behavior of women receiving hormone replacement therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:69–74. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bestul MB. McCollum M. Hansen LB. Saseen JJ. Impact of the Women's Health Initiative trial results on hormone replacement therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:495–499. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.5.495.33349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hersh AL. Stefanick ML. Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy annual trends and responses to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hass JS. Kaplan CP. Gerstenberger EP. Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:184–188. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson J. Wise L. Green J. Prescribing of hormone therapy for menopause, tibolone, and bisphosphonates in women in the UK between 1991 and 2005. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:843–849. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udell JA. Fischer MA. Brookhart MA. Solomon DH. Choudhry NK. Effect of the Women's Health Initiative on osteoporosis therapy and expenditure in Medicaid. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:765–771. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usher C. Teeling M. Bennett K. Feely J. Effect of clinical trial publicity on HRT prescribing in Ireland. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:307–310. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang WF. Tsai YW. Hsiao FY. Liu WC. Changes of the prescription of hormone therapy in menopausal women: An observational study in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thunell L. Milsom I. Schmidt J. Mattsson LA. Scientific evidence changes prescribing practice—A comparison of the management of the climacteric and use of hormone replacement therapy among Swedish gynaecologists in 1996 and 2003. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;113:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee E. Wutoh AK. Xue Z. Hillman J. Zuckerman IH. Osteoporosis management after the Women's Health Initiative study in a Medicaid population. J Womens Health. 2006;15:155–161. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazar F., Jr Costa-Paiva L. Morais SS. Pedro AO. Pinto-Neto AM. The attitude of gynecologists in Sao Paulo, Brazil, 3 years after the Women's Health Initiative study. Maturitas. 2007;56:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang BM. Kim MR. Park HM, et al. Attitudes of Korean clinicians to postmenopausal hormone therapy after the Women's Health Initiative study. Menopause. 2006;13:125–129. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000191211.51232.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stafford RS. Drieling RL. Hersh AL. National trends in osteoporosis visits and osteoporosis treatment, 1988–2003. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1525–1530. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parente L. Uyehara C. Larsen W. Whitcomb B. Farley J. Long-term impact of the Women's Health Initiative study on HRT. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huot L. Couris CM. Tainturier V. Jaglal S. Colin C. Schott AM. Trends in HRT and antiosteoporosis medication prescribing in European population after the WHI study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1047–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farley JF. Blalock SJ. Cline RR. Effect of the Women's Health Initiative on prescription antiosteoporosis medication utilization. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1603–1612. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0607-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wysowski DK. Governale LA. Use of menopausal hormones in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:171–176. doi: 10.1002/pds.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly JP. Kelly JP. Kaufman DW, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy since the Women's Health Initiative study findings. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:837–842. doi: 10.1002/pds.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ly N. McCaig L. Burt CW. Advance data from vital and health statistics, No. 321. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1999 Outpatient Department Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherry DK. Woodwell DA. Advance data from vital and health statistics, No. 387. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Middleton K. Hing E. Advance data from vital and health statistics, No. 327. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 Outpatient Department Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lobo RA. Menopause. In: Goldman L, editor; Bennett JC, editor. Cecil textbook of medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 2000. pp. 1360–1366. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boothby L. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. P&T. 2002;27:506–513. [Google Scholar]

- 28.IMS-Health. Plymouth Meeting, PA: IMS-Health; 1999. Total promotion reports 1998: Report TPR-2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tosteson AN. Grove MR. Hammond CS, et al. Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton B. McCoy K. Taggart H. Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:259–262. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yood RA. Emani S. Reed JI. Lewis BE. Charpentier M. Lydick E. Compliance with pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:965–968. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCombs JS. Thiebaud P. Mclaughlin-Miley C. Shi J. Compliance with drug therapies for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Maturitas. 2004;48:271–287. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papaioannou A. Ionnidis G. Adachi JD, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonates and hormone replacement therapy in a tertiary care setting of patients in the CANDOO database. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:808–813. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss M. Vered I. Foldes AJ, et al. Treatment preference and tolerability with alendronate once weekly over a 3-month period: An Israeli multi-center study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:143–149. doi: 10.1007/BF03324587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller PD. Epstein S. Sedarati F. Reginster JY. Once-monthly oral ibandronate compared with weekly oral alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis: Results from the head-to-head MOTION study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:207–213. doi: 10.1185/030079908x253889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodgson SF. Watts NB. Bilezikian JP, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2001 edition with selected updates for 2003. Endocr Pract. 2003;9:544–564. doi: 10.4158/EP.9.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The North American Menopause Society. Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: July 2008 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2008;15:584–602. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31817b076a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. www.nof.org/professionals/NOF_Clinicians_Guide.pdf. [Nov 21;2008 ]. www.nof.org/professionals/NOF_Clinicians_Guide.pdf

- 39.Lee E. Zuckerman IH. Weiss SR. Patterns of pharmacotherapy and counseling for osteoporosis management in visits to U.S. ambulatory care physicians by women. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2362–2366. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farley JF. Cline RR. Gupta K. Racial variations in antiresorptive medication use: Results from the 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:395–404. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown AF. Pérez-Stable EJ. Whitaker EE, et al. Ethnic differences in hormone replacement prescribing patterns. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:663–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.10118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsh JV. Brett KM. Miller LC. Racial differences in hormone replacement therapy prescriptions. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:999–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weng HH. McBride CM. Bosworth HB. Grambow SC. Siegler IC. Bastian LA. Racial differences in physician recommendation of hormone replacement therapy. Prev Med. 2001;33:668–673. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]