Abstract

Objective

To examine the efficacy of an interactive, child-centred and family-based program in promoting healthy weight and healthy lifestyles in Chinese American children.

Design

A randomized controlled study of a culturally sensitive behavioral intervention.

Subjects

Sixty-seven Chinese American children (ages, 8–10 years; normal weight and overweight) and their families.

Measurements

Anthropometry, blood pressure, measures of dietary intake, physical activity, knowledge and self-efficacy regarding physical activity and diet at baseline and 2, 6 and 8 months after baseline assessment.

Results

Linear mixed modeling indicated a significant effect of the intervention in decreasing body mass index, diastolic blood pressure and fat intake while increasing vegetable and fruit intake, actual physical activity and knowledge about physical activity.

Conclusion

This interactive child-centred and family-based behavioral program appears feasible and effective, leading to reduced body mass index and improved overweight-related health behaviors in Chinese American children. This type of program can be adapted for other minority ethnic groups who are at high risk for overweight and obesity and have limited access to programs that promote healthy lifestyles.

Keywords: Chinese Americans, family based, healthy lifestyles, overweight prevention, randomized clinical trail

Introduction

Obesity is the most critical public health concern facing children of all ethnicities today, including Chinese Americans. One study suggests that 31% of Chinese Americans 6–11 years old are overweight (body mass index (BMI) >85th percentile) or obese (BMI >95th percentile).1 At the same BMI, Chinese Americans are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus than non-Hispanic whites.2,3 Obese children have increased risk for cardiovascular risk factor clustering.4 Approximately 56% of the overweight Chinese children in the mainland China have at least two criteria of metabolic syndrome (i.e. glucose intolerance, obesity, hypertension and dyslipidemia).5 A study of Chinese American children also suggests that a higher BMI is associated with higher levels of low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol.6 Additionally, the risk of hypertension and diabetes doubles for Chinese American adults with a BMI of 23–24.9 and triples for those with a BMI of 25–26.9;7–9 possibly because due to genetic differences in the body composition and metabolic responses.2,3,10 As obese children tend to be obese adults, overweight management needs to start in childhood. Given the negative effect of obesity on Chinese American children's health, developing a culturally appropriate intervention is imperative to reduce health disparities in this population.

Weight management interventions can be effective when they are designed to simultaneously change dietary behavior, increase physical activity, reduce television viewing time and improve coping, and when they are culturally appropriate, parent-inclusive and tailored to the unique individual characteristics of each participant.11–17 However, multifaceted interventions have not been tested in Chinese American children and their families. Thus, we developed an individual tailored child-centred and family-focused behavioral program (Active Balance Childhood [ABC] study) that focuses on promoting healthy weight management and healthy lifestyles (adequate dietary intake and improved physical activity) in Chinese American children, ages 8–10, and their families.

The aim of this study is to examine the efficacy of the ABC program in promoting healthy weight and healthy lifestyles in Chinese American children. Our hypotheses were that children in the intervention group will report a decrease in BMI and waist-to-hip ratio, a healthier dietary intake (more vegetable and fiber and lower fat and sugar intake), being more active and improved knowledge and self-efficacy in physical activity and nutrition than will children in the control group measured 2, 6 and 8 months later.

Participants and methods

A randomized controlled study design was used to examine the efficacy of the ABC study's program. Children in the study completed questionnaires regarding their levels of physical activity, dietary intake, usual food choices, knowledge of nutrition and physical activity and self-efficacy related to physical activity and healthy food choices at baseline (T0) and 2 months (T1), 6 months (T2) and 8 months (T3) after the baseline assessment. The primary caregiver completed questionnaires regarding parents' demographic information and levels of acculturation. Eight to 10-year-old Chinese American children who were normal weight or overweight and their parents were eligible for enrollment if they met the following criteria: (1) The adult and child self-identify ethnicity as Chinese or of Chinese origin, and they reside in the same household. A dyad of one adult and one child was the minimum necessary for a household to participate. Two adults per child were encouraged to participate. (2) The child was able to speak and read English. (3) The child was in good health, defined as free of an acute or life-threatening disease and able to attend to activities of daily living such as going to school. Children with chronic health problems that included any dietary modifications or activity limitations (e.g. diabetes, exercise-induced asthma) were excluded. (4) Parents were able to speak English, Mandarin or Cantonese and were able to read in English or Chinese and to complete questionnaires. Overweight is defined as a child having BMI ≥85th percentile whereas normal weight is a child having a BMI between 5th–84th percentile for his/her age and gender, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth chart. Data were collected from September 2006 to December 2008.

Study procedure and intervention

Upon approval from the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research, 8- to 10-year-old children who self-identified as Chinese and their mothers were invited to participate in this study. Participants were recruited from Chinese language programs in the San Francisco Bay area. Research assistants described the study to potential children and gave them an introduction letter and research consent form to take home to their parents. Parents who were interested in the study signed and returned the consent form, providing their names and contact information to the research team. Children and parents were informed that they could refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time.

After parents gave informed consent and children provided verbal assent, baseline data were collected, and children and parents were randomly assigned to the intervention group or the waiting list control group by a computer-generated random number assignment (Fig. 1). Research assistants went to the study site and administered all of the questionnaires for children to complete. Children also had their weight, height, waist and hip circumferences and blood pressure measured. Parents completed questionnaires at home and mailed them back to the research team within 2-weeks of receiving them. Children assigned to the intervention group participated in small group weekly session activities for 8 weeks, and parents in the intervention group participated in two small group workshops in 8 weeks.

Fig. 1.

Study procedure.

Waiting-list control group children and families participated in the data collection activities at the same time as those in the intervention group. After completing the final follow-up assessment, this group received the ABC study intervention.

ABC study intervention overview

The intervention is based on the social cognitive theory developed by Bandura.18–20 The theory proposes that cognitive factors, behavioral factors (including other personal factors such as preferences and competencies), and environmental influences are interactive and integrated determinants. The learning and social influences stem both directly and vicariously from numerous resources, including parents. In this model of reciprocal causation, cognitive, behavioral and environmental factors all operate as interrelating determinants. Several key concepts such as self-efficacy, outcome expectation, skill mastery and self-regulation capabilities included in the social cognitive theory are used to explain and predict a person's behavior.18–20 This study intervention addressed these concepts by attempting to increase children's and parents' self-efficacy through setting realistic and achievable goals, providing necessary skills to achieve mastery, and improving self-regulation in maintaining healthy weight and healthy lifestyles.

Once four to six families had been randomized to the intervention group, the parents and children met separately for small-group sessions. Children participated in a 45-min session once each week for 8 weeks, and parents participated in two sessions that lasted 2 h each session during that 8 weeks. Children took part in a play-based workshop facilitated by a bicultural/bilingual research assistant. The intervention program consisted of educational play-based activities that increase children's self-efficacy and facilitate their understanding and use of critical thinking and problem-solving skills related to nutrition, physical activity and coping. The intervention for children was designed to improve their self-efficacy and self-competence via interactive activities (such as games and play), and to promote internal motivation to change health behaviors and maintain a healthy weight. For example, children learned how to select healthy meals and will be involved in role-playing and practice sessions about options and choices related to high-sugar and high-fat foods. An interactive dietary preparation software program tailored to common Chinese foods that was developed by Joslin Diabetes Center Asian American Diabetes Initiative was used for this study.21 In each session, children engaged in lessons related to nutrition, physical activity and critical thinking (See Table 1 for overview of the intervention program components).

Table 1.

Intervention program for children

| Week | Objective | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Understand how body work and how to recognize and cope with feelings | The importance of healthy food and active lifestyle to our health. |

| The importance of healthy coping including recognize feeling and adequate problem-solving skills to your health | ||

| 2 | Ability to utilize adequate problem-solving techniques and coping skills | Relaxation techniques |

| 5 steps problem solving | ||

| Coping, stress and health | ||

| 3 | Ability to be utilized adequate relaxation techniques and developed healthy coping | Relaxation techniques |

| Self-monitoring: tracks of my feeling | ||

| Healthy coping strategies | ||

| 4 | Understand food and health | Nutrition information including food pyramid, reading labels and serving size |

| Understand your current eating habits and setting a realistic goal for healthy eating | ||

| Food and stress: alternative to reducing your stress | ||

| 5 | Ability to be make smart food choice | The Family Wok: how to help your family prepare healthy eating |

| Ways to prepare healthy and easy snacks | ||

| Celebrating holidays with healthy/yummy food | ||

| Food and stress: alternative to improve your health and mood | ||

| 6 | Ability to be improve activity level | How does physical activity help you? |

| How much should you be active? | ||

| Fun activities for anytime and anywhere | ||

| 7 | Understand various fun activities for children and families | Fun activities for anytime and anywhere |

| Activities for the whole family | ||

| Alternative to stress: exercise for better health and happy mood | ||

| 8 | Understand key concepts about healthy and happy childhood | Active lifestyle for healthy and happy body |

| Balance nutrition for better health | ||

| Coping with stress/unhappiness | ||

| Making smart choices for you and your family |

At the beginning of each session, children spent 15 min on physical activities. Physical activity sessions were aimed at increasing children's energy expenditure by implementing a 15-min activity session each week for 8 weeks. They engaged in different types of non-competitive activities (such as dance, brisk walking and jump rope), learned types of activities that they can do during recess and at home, and also learned alternatives to watching television. In addition, children received a pedometer, activity diary and books related to physical activity. For the remaining 30 min of each session, we focused on children's knowledge regarding nutrition and physical activity and reinforced the notion of self-efficacy regarding food choices and alternatives to high-fat and high-sugar foods and television viewing. Children received a food diary to record their food intake, books related to healthy eating and a packet of materials in both Chinese and English each week explaining the activities that highlight healthy eating and active lifestyles.

A family component (two 2-h sessions) was incorporated into this study to provide reinforcement and social support at home for the education received during the study. The parents took part in ‘Healthy Eating and Healthy Family: A Hands-on Workshop’, which was led by a bilingual/bicultural registered dietitian. The group workshops (8–10 parents) included sets of exercises to increase parents' knowledge and skills regarding healthy food preparation, discussion of issues related to dealing with children's eating habits and problems and brainstorming about specific family/children activities to improve dietary intake and physical activity. The parent intervention included a workbook, video clips and discussion of techniques. In addition, parents were encouraged to allow children to make their own choices for agreeable foods and activities. Parents were also encouraged to involve their children in grocery shopping and meal preparation.

After completion of each of the data collection activities, parents and children received a $10 gift certificate. Upon completion of the study, they received a $30 gift certificate. At the 2 month (T1), 6 month (T2) and 8 month (T3) assessments, the children completed questionnaires regarding their dietary intake, usual food choices, knowledge about nutrition and physical activity and self-efficacy regarding physical activity and food choice. The children also wore a Caltrac personal activity computer to measure their physical activity and had their weight, height, blood pressure and waist and hip circumferences measured at all the assessments. Primary caregivers (all mothers) completed questionnaires regarding their demographic information and acculturation level at baseline. Children completed their questionnaires in English, and parents completed questionnaires in either Chinese or English.

Parental measures

Family information

The 12-item parent questionnaire includes parent(s)' and children's ages, parents' weights and heights, parents' occupation(s), family income and parents' levels of education. The questionnaire was written at a third-grade reading level and took approximately 5 min to complete. Mothers completed this questionnaire at baseline.

Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale

The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale (SL-ASIA) is used to examine the levels of maternal acculturation.22,23 The SL-ASIA scale is a 21-item multiple-choice questionnaire covering topics such as language (4 items), identity (4 items), friendships (4 items), behaviors (5 items), general and geographic background (3 items) and attitudes (1 item). Scores could range from a low of 1.00, indicative of low acculturation or higher Asian identity, to a high of 5.00, indicative of high acculturation or high Western identity. The scale also permits classification as ‘bicultural’, indicating that a person has adopted some Asian values, beliefs and attitudes along with some Western values, beliefs and attitudes. Validity and moderate to good reliability have been reported.22,23 The Cronbach alpha for the SL-ASIA was 0.79–0.91 for Chinese Americans.22,23 This questionnaire is available in Chinese and English and is written at a fifth-grade reading level. It takes about 10 to 15 min to complete the questionnaire.

Children's measures

BMI

BMI has a well-established association with stature and age among children and adolescents.24,25 BMI was calculated by dividing body mass in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). BMI has acceptable ranges of sensitivities and specificity. Sensitivity ranged from 29 to 88%, specificity ranged from 94 to 100% and predictive value ranged from 90 to 100%, in children24,25 In this study, BMI lower than the 5th percentile was defined as underweight, between the 6th and 84th percentile was defined as normal weight and BMI above the 85th percentile was defined as overweight and 95th percentile as obese, based on the growth chart developed by CDC.

Waist-to-hip ratio

The waist-to-hip ratio was derived from the waist and hip circumferences. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and the superior border of the iliac crest. Hip circumference was measured at the maximal protrusion of the buttocks. The circumferences were given as the mean of two measurements to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Blood pressure

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured by using a mercury sphygmomanometer with specific cuff size appropriate for children (Baumanometer, W.A. Baum Co, Copiague, New York) to the nearest 2 mm Hg, twice in the child's right arm, with the child seated after 10 min of rest.

Caltrac personal activity computer

The Caltrac has been widely used in assessing physical activity among children and adults.26 Although there are other advanced measures of physical activity (i.e. accelerometer), we chose to use Caltrac in our study because of its relatively low cost ($70) and ease of use. The Caltrac is designed to be placed at the hip and to measure vertical acceleration. Readings from the device have been used to predict oxygen consumption and net caloric expenditure, based on the user's age, height and weight, during exercise. The Caltrac has a moderate to high validity, ranging from 0.35 to 0.97, with heart rate and observation methods.26 A high reliability of the device, ranging from 0.87 to 0.98, was also reported in children.26 In this study, children were instructed to place the Caltrac at the hip for 3 consecutive days (two weekdays and one weekend day). Children were also instructed to wear the Caltrac as soon as getting up from the bed in the morning and remove it only in shower, in water-related activities (i.e. swimming) and sleeping. Average count was used for analysis.

Three-day food diary

This quantitative self-report food diary was used to estimate dietary intake of children. Children received a 3-day food diary containing an instruction sheet, a sample completing day's food-record sheet and eight blank white dietary record forms. Each form included spaces for the child's name, day of the week, date of recording and blank lines to record food and drink grouped into the following categories: breakfast, snack, lunch, snack, dinner and snack. Children were asked to record all foods and beverages consumed for 3 consecutive days. They also recorded serving sizes. Kappa coefficients and percent of agreement for interobserver reliability ranged from 0.43 to 0.91.27,28 The diary takes approximately 10 min to complete. Parents were asked to complete the diary together with their children to increase the accuracy of dietary report.

Usual food choices

This 14-item survey was part of the Health Behavior Questionnaire developed for the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) study. This survey asked about usual food choices (behavior) in a forced-choice format that focuses on low-fat and low-sodium foods. It measured usual food selections and what types of food a child eats most of the time. Children were given a choice between two foods and asked which one they eat more often. Sample questions are ‘Which foods do you eat most of the time: hot dog or chicken? Frozen yogurt or ice cream?’ A higher score indicated more healthy food choices. Validity was obtained by including expert review and pilot testing with a focus group. The alpha coefficient for internal consistency in the original study was 0.76.29

Physical activity knowledge

This five-item questionnaire was developed by the researcher to assess children's knowledge about physical activity. Items were adapted from recommendations from the US Department of Agriculture30 and the American Heart Association31 regarding dietary guideline, MyPyramid and children's health. Sample questions included the following: How much aerobic activity is required for a healthy heart? How many hours a day should a child watch television or play video games? The reliability coefficient for internal consistency with the sample of children in this study was 0.65. Children received one point for every question they answered correctly. A higher score indicates more accurate knowledge about physical activity needs. The total score was used for analysis.

Dietary knowledge

This 14-item survey also was part of the Health Behavior Questionnaire developed for the CATCH study. It measured children's knowledge about healthy food choices. Children were asked to identify which food was ‘better for your health’. Samples of two choices included ‘whole wheat or white bread’ and ‘frozen corn or canned corn’. Content validity was examined by including expert review and focus group pilot testing from the CATCH study. This survey had a reported internal consistency ranging from 0.76 to 0.78.29 A higher score indicates more accurate dietary knowledge.

Child dietary self-efficacy

This 15-item self-report questionnaire measured children's self-confidence in their ability to choose foods low in fat and sugar.29 The questionnaire contained 15-item stems beginning with ‘How sure are you… ?’ Items were scored on a Likert scale, with options of ‘not sure’, ‘a little sure’ or ‘very sure’. Higher scores indicated higher self-efficacy. The internal consistency ranged from 0.82 to 0.87 in the third and fifth graders.29,32 The questionnaire took about five to 10 min for children to complete.

Physical activity self-efficacy

This subscale of the Health Behavior Questionnaire was used to measure the children's self-confidence in their ability to participate in various age-appropriate physical activities.29,32 The subscale included five items in which children were asked if they were ‘not sure’, ‘a little sure’ or ‘very sure’ that they could do such things as ‘keep up a steady pace without stopping for 15–20 min’. Higher scores indicated higher self-efficacy. Internal consistency ranged from 0.67 to 0.69 in the third and fifth graders.29,32 The questionnaire took about two to 5 min for children to complete.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated initially for demographic characteristics and all major study variables. We used t-tests to examine any differences in variables between intervention and control groups at the baseline. We examined whether the rate of change across the four data collection time points was different for the children in the intervention group than for children in the control group by fitting linear mixed-effects models that included functions of time and group effects to the repeated child data. With a continuous outcome, the mixed-model approach to analyze longitudinal data is a method of modeling population parameters as fixed effects while simultaneously modeling individual subject parameters as random effects. The modeling of individual subjects was obtained as random deviations about the population model. Follow up t-tests were used to examine the efficacy of the intervention on three follow-up time (T0–T1, T0–T2, T0–T3). All analyses were performed in SPSS 15.0, with 0.05 set as the required level of significance.

Power analysis

A minimum of 30 participants per group provides power of 0.85 at an alpha of 0.05 to detect a moderate difference in BMI between the two groups between baseline and 8-month follow-up (mean BMI difference 0.8 between the groups which reflects a difference of 1 of a standard deviation [SD]).

Results

Descriptive data

Initially, 72 children and families agreed to participate in this study. Of these, 67 children and their parents met the criteria for eligibility and were enrolled in this study. Baseline characteristics of the complete sample are shown in Table 2. Thirty-five children and their families were randomized to the intervention group and 32 children and their families were randomized to the control group. The mean age of the children was 8.97 (SD, 0.89) years. Twenty-nine of the children were girls and 31 children were overweight or obese with BMI greater than the 85th percentile based on CDC growth chart. Approximately 51% of children in the intervention group and 41% of children in the control group were overweight or obese (X2 = 0.79, P = 0.38). Approximately 54% of children in the intervention group and 59% of children in the control group were boys (X2 = 0.18, P = 0.68). No difference was found in the overweight distribution by sex between children in the intervention group and children in the control group.

Table 2.

Means and SD for all variables at baseline

| All (n = 67) | Intervention (n = 35) | Control (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children variables | |||

| Age, years | 8.97 (0.89) | 9.14 (0.85) | 8.78 (0.91) |

| Body mass indexa | 19.22 (3.18) | 19.74 (3.58) | 18.65 (2.63) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.89 (0.05) | 0.88 (0.04) | 0.89 (0.06) |

| Systolic blood pressureb | 103.41 (8.36) | 105.74 (9.01) | 99.87 (5.81) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 61.03 (12.50) | 63.23 (12.91) | 57.70 (11.31) |

| Caltrac count | 3951.52 (1405.22) | 3747.61 (1389.13) | 4228.84 (1407.04) |

| Fat, % | 29.32 (3.00) | 29.76 (2.83) | 28.50 (3.20) |

| Sugar, gb | 25.26 (9.32) | 28.84 (8.15) | 19.08 (8.03) |

| Vegetables and fruit, number of servings | 2.12 (0.73) | 2.15 (0.73) | 2.08 (0.75) |

| Food choice | 9.01 (2.16) | 9.14 (2.21) | 8.84 (2.11) |

| Physical activity knowledge | 3.63 (1.07) | 3.69 (1.11) | 3.56 (1.05) |

| Nutrition knowledge | 9.58 (2.72) | 9.47 (2.99) | 9.71 (2.40) |

| Physical activity self-efficacy | 2.32 (0.47) | 2.31 (0.45) | 2.33 (0.50) |

| Nutrition self-efficacy | 2.43 (0.41) | 2.44 (0.42) | 2.40 (0.42) |

| Parent variables | |||

| Mother's age, years | 41.44 (4.37) | 41.53 (4.85) | 41.33 (3.76) |

| Mother's education, years | 14.03 (4.55) | 14.03 (4.35) | 14.04 (4.87) |

| Mother's body mass index | 23.06 (3.82) | 22.71 (4.05) | 23.54 (3.49) |

| Father's age, years | 44.25 (5.28) | 43.60 (5.42) | 44.96 (5.11) |

| Father's education, years | 15.59 (3.69) | 15.47 (3.36) | 15.71 (4.06) |

| Father's body mass index | 24.88 (4.59) | 24.13 (5.61) | 25.69 (3.61) |

aCalculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

bSignificant difference between the intervention and control groups at P < 0.05.

The mean maternal age was 41.4 (SD, 4.37) years, and the mean number of years of education was 14 (SD, 4.55) years. The mean BMI for mothers was 23.06 (SD, 3.82). The mean paternal age was 44.25 years (SD, 5.28), and the mean number of years of education was 15.59 years (SD, 3.69). Their mean acculturation score was 2.38 (SD, 0.69) suggesting a low acculturation. The mean BMI for fathers was 24.88 (SD, 4.59). Baseline variables did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups, except for systolic blood pressure and sugar intake (intervention group had higher level than the control group; see Table 2).

Longitudinal analysis

Fifty-seven children and their families (85%) completed baseline and follow-up measures; 94% of children in the intervention group and 75% of children in the control group completed baseline and follow-up measures. No significant differences were found in baseline variables between children who provided follow-up data and those lost to follow-up.

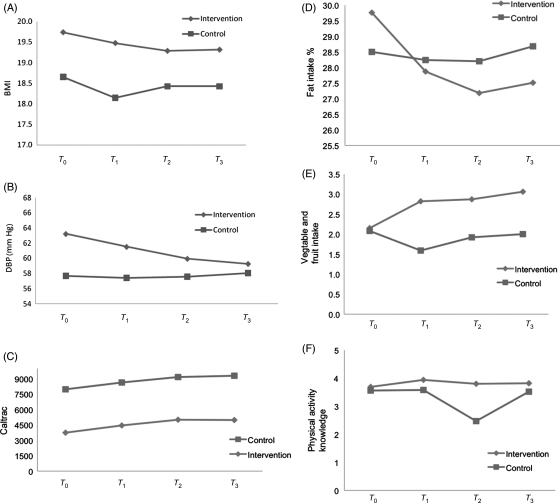

Data on outcome variables for the intervention and control groups are presented in Table 3. The mixed-model analysis indicated that significantly more of the children in the intervention group had decreased their BMI, decreased DBP, increased physical activity as measured by Caltrac, decreased fat intake, and increased vegetable and fruit intake than did the children in the control group (see Table 4 and Fig. 2 for summary of mixed-model analysis). All children in the study increased their knowledge about physical activity over time (effect = − 0.227, P = 0 .008) with more significant increases in the intervention group than in the control group (effect = 0.266, P = 0.02).

Table 3.

Means and SD for all outcome variables in the intervention and control groupsa

| Variable |

Intervention |

Control |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Body mass indexb | 19.48 (3.48) | 19.29 (3.45) | 19.32 (3.38) | 18.14 (2.60) | 18.42 (2.69) | 18.42 (2.56) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.88 (0.04) | 0.88 (0.04) | 0.88 (0.04) | 0.91 (0.06) | 0.90 (0.06) | 0.90 (0.06) |

| Systolic blood pressure | 104.97 (9.10) | 103.88 (7.84) | 102.91 (8.25) | 99.65 (6.63) | 98.90 (7.01) | 99.00 (6.36) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 61.52 (9.62) | 59.94 (9.95) | 59.27 (9.62) | 57.43 (10.95) | 57.60 (11.65) | 58.05 (10.81) |

| Caltrac count | 4452.90 (1342.03) | 5011.51 (1188.82) | 4979.72 (1187.90) | 4188.45 (1242.58) | 4160.95 (1072.79) | 4319.62 (1250.96) |

| Fat, % | 27.87 (2.90) | 27.18 (2.92) | 27.51 (2.09) | 28.24 (2.78) | 28.20 (2.47) | 28.68 (2.71) |

| Sugar, g | 26.45 (8.22) | 24.16 (7.91) | 24.68 (6.32) | 21.81 (8.89) | 20.97 (7.34) | 21.85 (7.81) |

| Vegetables and fruit, number of servings | 2.82 (0.80) | 2.87 (0.80) | 3.06 (0.82) | 1.59 (0.75) | 1.92 (0.64) | 2.00 (0.79) |

| Food choice | 8.86 (2.32) | 9.05 (2.50) | 8.45 (2.30) | 7.98 (1.67) | 7.50 (2.11) | 7.56 (2.48) |

| Physical activity knowledge | 3.94 (0.81) | 3.80 (1.18) | 3.82 (0.83) | 3.58 (1.18) | 2.47 (1.88) | 3.52 (0.81) |

| Nutrition knowledge | 9.82 (2.85) | 10.30 (2.34) | 10.65 (2.04) | 8.85 (2.61) | 7.86 (2.49) | 10.31 (1.91) |

| Physical activity self-efficacy | 2.46 (0.37) | 2.44 (0.41) | 2.40 (0.42) | 2.27 (0.52) | 2.38 (0.53) | 2.35 (0.63) |

| Nutrition self-efficacy | 2.63 (0.39) | 2.61 (0.39) | 2.65 (0.50) | 2.31 (0.51) | 2.46 (0.42) | 2.44 (0.42) |

aT1 was 2 months, T2 was 6 months and T3 was 8 months after the baseline assessment.

bCalculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Table 4.

Summary of mixed-model analysis for effects of the ABC intervention

| Outcomes | Parameter | Effect estimate | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index | Time | 0.018 | −0.035–0.071 | 0.51 |

| Group | 1.080 | −0.404–2.565 | 0.15 | |

| Time × groupa | −0.150 | −0.220–0.080 | 0.001 | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | Time | 0.001 | −0.005–0.006 | 0.84 |

| Group | −0.012 | −0.045–0.020 | 0.45 | |

| Time × group | −0.001 | −0.008–0.006 | 0.79 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | Time | −0.534 | −1.203–0.134 | 0.12 |

| Groupa | 5.961 | 2.079–9.844 | 0.003 | |

| Time × group | −0.533 | −1.377–0.312 | 0.22 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure | Time | −0.177 | −1.123–0.769 | 0.71 |

| Group | 5.309 | −0.101–10.719 | 0.05 | |

| Time × groupa | −1.305 | −2.499–0.111 | 0.03 | |

| Caltrac count | Time | 1.341 | −148.974–151.655 | 0.99 |

| Group | −228.827 | −853.142–395.488 | 0.47 | |

| Time × groupa | 428.685 | 236.059–621.310 | 0.001 | |

| Fat, mean, % | Time | −0.160 | −0.487–0.167 | 0.34 |

| Group | 0.679 | −0.803–2.161 | 0.36 | |

| Time × groupa | −0.542 | −0.938–0.146 | 0.008 | |

| Sugar, mean, g | Time | −0.264 | −1.079–0.551 | 0.52 |

| Group | 0.748 | −2.692–4.188 | 0.67 | |

| Time × group | −0.693 | −1.681–0.295 | 0.17 | |

| Vegetable and fruit, number of servings, mean | Time | −0.032 | −0.141–0.077 | 0.56 |

| Group | 0.497 | 0.051–0.943 | 0.06 | |

| Time × groupa | 0.306 | 0.175–0.438 | 0.001 | |

| Food choice | Timea | −0.505 | −0.859–0.152 | 0.005 |

| Group | 0.337 | −0.709–1.383 | 0.52 | |

| Time × group | 0.329 | −0.118–0.776 | 0.15 | |

| Physical activity knowledge | Timea | −0.227 | −0.392–0.061 | 0.008 |

| Group | 0.311 | −0.232–0.853 | 0.26 | |

| Time × groupa | 0.266 | 0.047–0.484 | 0.02 | |

| Nutrition knowledge | Time | 0.125 | −0.234–0.484 | 0.49 |

| Group | 0.244 | −0.891–1.379 | 0.67 | |

| Time × group | 0.287 | −0.194–0.767 | 0.24 | |

| Physical activity self-efficacy | Time | 0.031 | −0.024–0.086 | 0.27 |

| Group | 0.027 | −0.195–0.248 | 0.81 | |

| Time × group | −0.003 | −0.075–0.070 | 0.94 | |

| Nutrition self-efficacy | Time | 0.022 | −0.032–0.077 | 0.42 |

| Group | 0.104 | −0.098–0.306 | 0.31 | |

| Time × group | 0.042 | −0.028–0.113 | 0.24 |

aSignificant difference between intervention and control groups at P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Significant changes in (A) body mass index, (B) diastolic blood pressure, (C) Caltrac, (D) fat intake, (E) vegetable and fruit intake and (F) physical activity knowledge.

Follow-up t-tests on significant outcome variables revealed that significant differences were found between T0 and T1, T0 and T2 and T0 and T3 on BMI, physical activity, fat consumption and vegetable and fruit intake in the intervention group (P < 0.05). Significant differences were also found between T0 and T2 and T0 and T3 on SBP and DBP (P < 0.05). No significant differences were found on outcome variables between T0 and T1, T0 and T2 and T0 and T3 in the control group except for physical activity knowledge in which decreased physical activity knowledge found in T2 compared with T0).

Discussion

Main finding of this study

The results suggest that Chinese American children in an interactive child-centred and family-based behavioral program (such as the ABC study) decreased their BMI and DBP, increased their physical activity level, decreased fat intake, increased vegetable and fruit intake and increased their knowledge regarding physical activity significantly more than children in the control group. Results indicate that a culturally appropriate healthy lifestyle program that uses interactive small-group sessions can be effective in promoting healthy weight and healthy lifestyles for Chinese American children.

Children in the intervention group showed decreased BMI and DBP whereas children in the control group kept similar levels of BMI and blood pressure throughout the 8-month study. The decreased in BMI in the intervention group was found in all follow-up assessments (T1, T2 and T3) while decreased in both SBP and DBP was found at 6- (T2) and 8-month (T3) follow-up but not immediate after the intervention (T1). Improvements in children's BMIs have been associated with improvements in their lipid profiles, insulin sensitivities and cardiovascular function.33–35 Although the benefit of decreased relative weight may not been seen right after the intervention as shown in our study, our intervention suggests improvement of blood pressure 4-month post-intervention. Thus, maintaining healthy weight in children is critical in improving their health, especially in cardiovascular health. Thus, our data suggest that such an intervention is an effective way of promoting healthy weight and improving blood pressure in Chinese American children.

In addition to the reductions in BMI and DBP, children in the intervention group also improved their overweight-related health behaviors by reducing fat intake and increasing vegetable and fruit intake and physical activity level more so than children in the control group. The improvement of fat and vegetable and fruit intake is seen in all study follow-up assessments. Improving dietary behaviors and physical activity level have been suggested to be critical factors in reducing overweight in children.36–38 Our intervention demonstrates an improvement in several overweight-related behaviors, and these behaviors last for several months after the intervention ended. Moreover, we found that children in the intervention group also improved their knowledge about physical activity more than children in the control group. Improvement of overweight-related health behaviors in combination with increasing knowledge can be related to the reductions in BMI and DBP found in the intervention group. Our results are supported by results of other studies that suggest combined lifestyle interventions led to reductions in BMI in children, with the largest effects associated with parental involvement at least for several months after the intervention.13,15,39,40 Thus, intervention for healthy weight management in Chinese American children should incorporate information related to adequate diet and active lifestyles and should be tailored to the family's needs.

What is already known on this topic

Previous studies have suggested that effective interventions for overweight in children must target several overweight-related health behaviors (including dietary behavior, physical activity, problem-solving and coping skills). The program must include parents and must be culturally appropriate.11–15 However, such multifaceted and culturally sensitive program has not been tested in Chinese Americans.

What this study adds

Our intervention was based on social cognitive theory, targeted overweight-related behaviors and included parents as the partners in behavioral changes in their children. This program was also designed to fit the busy schedules of children and their families by delivering the intervention at the after-school program and date/time that were convenient for children and their families. To obtain feedbacks regarding the effect of the program, we interviewed participating parents in the intervention group (n = 22) after they have completed the program. Comments from participating families suggest that accessibility of the program was a key reason why children and their families participated in the intervention program. Given that the health issues related to overweight are substantial, accessible and convenient culturally appropriate child-centred and family-based intervention program can be effective in preventing overweight and improving cardiovascular health in a high-risk population. In conclusion, this interactive child-centred and family-based ABC program appears to be both feasible and effective in reducing BMI and promoting overweight-related health behaviors in Chinese American children.

Limitations of this study

Our study also has some limitations including (1) convenience sampling, (2) parents with high education, (3) only involved Chinese American children and (4) follow-up for only 6 months after the intervention. Despite our effort to retain participants, 25% of children and their families in the control group withdrew from the study, compared with only 6% of children in the intervention group. However, baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between children who completed the follow-up assessments and children who dropped out of the study. The high retention rate in the intervention group could be attributed to the interactive design of the program and culturally appropriate information taught to children and families, which attracts children and parents, as well as to the feasibility of the program that made it feasible for both children and their parents to participate in the study. Future research should examine the long-term effects of this program on insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular function as well.

Funding

This publication was made possible by grant number KL2 RR024130 to J.L.C. from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, Chinese Community Health Care Association community grants and in part by NIH grant DK060617 to M.B.H.

References

- 1.Tarantino R. Addressing childhood and adolescent overweight. Paper Presented at the NICOS Meeting of the Chinese Health Coalition. San Francisco, September. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens J. Ethnic-specific revisions of body mass index cutoffs to define overweight and obesity in Asians are not warranted. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(11):1297–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan CE, Ma S, Wai D, et al. Can we apply the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel definition of the metabolic syndrome to Asians? Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1182–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garnett SP, Baur LA, Srinivasan S, et al. Body mass index and waist circumference in midchildhood and adverse cardiovascular disease risk clustering in adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):549–55. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YP, Yang XG, Zhai FY, et al. Disease risks of childhood obesity in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2005;18(6):401–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen JL, Wu Y. Cardiovascular risk factors in Chinese American children: associations between overweight, acculturation, and physical activity. J Pediatr Health Care. 2008;22(2):103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coughlan A, McCarty DJ, Jorgensen LN, et al. The epidemic of NIDDM in Asian and Pacific Island populations: prevalence and risk factors. Horm Metab Res. 1997;29(7):323–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Chun KM, et al. Patient-appraised couple emotion management and disease management among Chinese American patients with type 2 diabetes. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(2):302–10. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ. Type 2 diabetes prevalence in Asian Americans: results of a national health survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):66–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faith MS, Leone MA, Ayers TS, et al. Weight criticism during physical activity, coping skills, and reported physical activity in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 Pt 1):e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR. Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(5):1008–15. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rugg K. Childhood obesity: its incidence, consequences and prevention. Nurs Times. 2004;100(3):28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(5):667–91. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summerbell CD, Ashton V, Campbell KJ, et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD001872. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young KM, Northern JJ, Lister KM, et al. A meta-analysis of family-behavioral weight-loss treatments for children. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(2):240–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enderlin CA, Richards KC. Research testing of tailored interventions. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2006;20(4):317–24. doi: 10.1891/rtnp-v20i4a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan P, Lauver DR. The efficacy of tailored interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(4):331–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psycholo. 1989;44:1175–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joslin Diabetes Center. 2007 http://aadi.joslin.harvard.edu/ (15 March 2006, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suinn RM, Khoo G, Ahuna C. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity acculturation scale: cross-cultural information. J Multicultural Counseling Dev. 1995;27:139–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suinn RM. Measurement of acculturation of Asian Americans. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health. 1998;6(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman DS, Perry G. Body composition and health status among children and adolescents. Prev Med. 2000;31:34–53. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goran ML. Measurement issues related to studies of childhood obesity: assessment of body composition, body fat distribution, physical activity, and food intake. Pediatrics. 1998;101:505–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noland M, Danner F, DeWalt K, et al. The measurement of physical activity in young children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1990;61(2):146–53. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1990.10608668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baxter SD. Accuracy of fourth-graders' dietary recalls of school breakfast and school lunch validated with observations: in-person versus telephone interviews. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2003;35(3):124–34. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber JL, Lytle L, Gittelsohn J, et al. Validity of self-reported dietary intake at school meals by American Indian children: the Pathways Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(5):746–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edmundson E, Parcel GS, Feldman HA, et al. The effects of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health upon psychosocial determinants of diet and physical activity behavior. Prev Med. 1996;25(4):442–54. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2006 Steps to a healthier you http://www.mypyramid.gov/steps/whatshouldyoueat.html. (15 March 2006, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Association AH (ed) Children's Health. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matheson DM, Killen JD, Wang Y, et al. Children's food consumption during television viewing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(6):1088–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirk S, Zeller M, Claytor R, et al. The relationship of health outcomes to improvement in BMI in children and adolescents. Obes Res. 2005;13(5):876–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemet D, Barkan S, Epstein Y, et al. Short- and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary-behavioral-physical activity intervention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e443–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinehr T, Andler W. Changes in the atherogenic risk factor profile according to degree of weight loss. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(5):419–22. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.028803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen JL, Kennedy C. Factors associated with obesity in Chinese-American children. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(2):110–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JL, Kennedy C, Yeh CH, et al. Risk factors for childhood obesity in elementary school-age Taiwanese children. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20(3):96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2005.04456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicklas TA, Baranowski T, Cullen KW, et al. Eating patterns, dietary quality and obesity. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(6):599–608. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGovern L, Johnson JN, Paulo R, et al. Treatment of pediatric obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(12):4600–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, et al. Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: a systematic review of randomised trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(9):987–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]