Abstract

Background

In the literature on family caregiving, care receiving and caregiving are treated generally as distinct constructs, suggesting that informal care and support flow in a unidirectional manner from caregiver to care recipient. Yet, informal care dynamics are fundamentally relational and often reciprocal, and caregiving roles can be complex and overlapping.

Objectives

To illustrate ways care dynamics may depart from traditional notions of dyadic, unidirectional family caregiving; and to stimulate a discussion of the implications of complex, relational care dynamics for caregiving science.

Approach

Exemplar cases of informal care dynamics were drawn from three ongoing and completed investigations involving persons with serious illness and their family caregivers. The selected cases provide examples of three unique, but not uncommon, care exchange patterns: (a) aging and chronically ill care dyads who compensate for one another's deficits in reciprocal relationships; (b) patients who present with a constellation of family members and other informal caregivers, as opposed to one primary caregiver; and (c) family care chains whereby a given individual functions as a caregiver to one relative or friend and care recipient to another.

Conclusions

These cases illustrate such phenomena as multiple caregivers, shifting and shared caregiving roles, and care recipients as caregivers. As caregiving science enters a new era of complexity and maturity, there is a need for conceptual and methodological approaches that acknowledge, account for, and support the complex, web-like nature of family caregiving configurations. Research that contributes to, and is informed by, a broader understanding of the reality of family caregiving will yield findings that carry greater clinical relevance than has been possible previously.

Keywords: caregivers, nursing research methodology, family caregiving

Conceptual Challenges in the Study of Caregiver-Care Recipient Relationships

Across clinical settings, nurses routinely interact with family members who accompany patients during healthcare encounters, and provide support and care afterwards. In response to the well-documented toll that informal care provision exacts upon family members (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2007; Schulz, O'Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995), nurse researchers have been at the forefront of efforts to ameliorate caregiver burden (Archbold et al., 1995; Given et al., 2006; Mahoney, Tarlow, & Jones, 2003; Stolley, Reed, & Buckwalter, 2002; Wykle, 1996). The need for additional, rigorous research on family caregiving is underscored in the National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR; n.d.) Strategic Plan for 2006-2010. Specifically, NINR calls for research to “develop interventions to improve the quality of caregiving” and “evaluate factors that impact the health and quality of life of informal caregivers and recipients” (p. 19). This bold vision requires a cohesive understanding of the constructs of informal caregiving and care receiving.

To date, most studies of family caregiving have defined care recipients as those who harbor a particular disease of interest, in turn labeling the relative who accompanies them to, or is present within, the research setting as the caregiver. The discourse on family caregiving generally treats care receiving and caregiving as distinct constructs (Lyons, Zarit, Sayer, & Whitlatch, 2002), suggesting that informal care and support flow in a unidirectional manner from caregiver to care recipient. In particular, studies of caregiving have been grounded typically in seminal theoretical work on stress processing (e.g., Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) and role theory (e.g., Burr, 1979). Both of these dominant theoretical approaches to caregiving science operate under the premise that caregiving and care receiving are distinct constructs. Under stress processing frameworks, behaviors exhibited by care recipients constitute environmental demands, referred to as stressors, that threaten or exceed the adaptive capacity of caregivers. Caregivers' adaptive capacity is modulated by a process of stress appraisal and response (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skiff, 1990; Schulz, Gallagher-Thompson, Haley, & Czaja, 2000; Vitaliano, Russo, Young, Teri, & Maiuro, 1991; Vitaliano, Young, & Russo, 1991). Schumacher, Beidler, Beeber, and Gambino (2006) deemed such approaches individualized because of their relative emphasis on caregiver outcomes and inattention to care recipient considerations. Similarly, caregivers are the focus of role-based approaches to the study of informal care dynamics. These approaches are centered around the construct of caregiving role strain and can be traced conceptually back to Burr's (1979) family role theory. Applications of role theory to the caregiving context are common among nurse researchers (Archbold, Stewart, Greenlick, & Harvath, 1990), with some investigators bridging the dominant theories to employ elements of both stress processing and role theory in their investigations (Almber, Grafstrom, & Winblad, 1997; Buckwalter et al., 1992).

In contrast to the mainstream treatment of caregiving as a dyadic phenomenon with a relative emphasis on caregivers, qualitative inquiries and other sociologically informed analyses reveal that informal care dynamics are fundamentally relational (Keith, 1995; Kittay, 1999), and often reciprocal (Feld, Dunkle, Schroepfer, & Shen, 2006; Thomas, 1999), which would suggest that caring roles, particularly in the social context of a family, are complex and overlapping. A series of cases is presented here to illustrate the reality of informal care relationships and to stimulate a discussion of the implications of complex, relational care dynamics for caregiving science.

Case Summaries

Exemplar cases of informal care dynamics were drawn selectively from three recent studies involving persons with serious illness and their family caregivers. Although each study contained multiple examples of complex informal care dynamics, these cases were selected to highlight the following three unique, but not uncommon, care exchange patterns: (a) aging and chronically ill care dyads who compensate for one another's deficits in reciprocal relationships; (b) patients who present with a constellation of family members and other informal caregivers, as opposed to one primary caregiver; and (c) family care chains whereby a given individual functions as a caregiver to one relative or friend and care recipient to another.

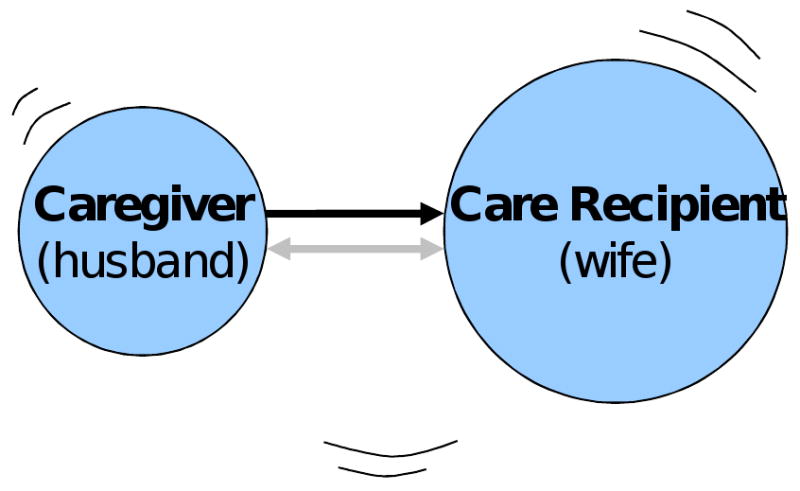

Case #1: Reciprocal care

Mrs. B. is a 65 year-old participant in a qualitative study of the experience of neutropenia (grant # and PI omitted for blinded review). Over the years, the B.'s have functioned as mutual caregivers and care recipients, with each caring for the other during acute illness episodes. At the time of study enrollment, Mrs. B. was hospitalized with acute myeloid leukemia. Atypical complications from chemotherapy led to an ICU stay and it was during this period of critical illness that Mr. B. was interviewed as Mrs. B.'s family caregiver. Voicing awareness of the two-sided coin of informal caregiving and care receiving, Mr. B. stated “I know what it's like [to be on the other side of caregiving]…I've been there.”

Mr. B. explained that he had been critically ill following complications of a heart valve replacement 2 years ago. He draws on his own experience as an acute care recipient and his other life experiences as he plans and delivers his wife's daily care as a leukemia patient. He helps her bathe and determines what they will eat, where–if anywhere–they will go, and how he will flush her intravenous catheter using sterile technique. Mrs. B.'s care involves a combination of emotional input, clinical decision-making, and technical skill, yet Mr. B. readily accepts this challenge, explaining that Mrs. B. has done so much for him; now it is his turn.

The B.'s case provides a window into a continuum of caregiving and receiving that can occur within older marital dyads. As depicted in Figure 1, Mr. and Mrs. B. exemplify a turn-taking model of reciprocal care, where partners alternate care roles, depending on one another to provide care in acute illness states. Turn-taking during acute illness is one of several possible variants of reciprocal, interdependent care. Married couples with chronic illnesses may compensate for each another's functional deficits in simultaneous mutual care relationships. Although couples represent the most common context for such interdependence, other relational configurations are possible including the growing, yet understudied, population of mentally disabled adult children (Pruchno, Patrick, & Burant, 1996; United States Census Bureau, 2005) who may function in mutual care relationships with their aging parents (Greenberg, Greenley, & Benedict, 1994; Lefley & Hatfield, 1999). Diverging from the B.'s overarching dynamic of interdependence and turn-taking, the reciprocal care patterns exhibited by developmentally challenged adults and their aging parents constitute a partial reversal of historical care exchange patterns with a shift toward long-term mutual interdependence. Such phenomena may be manifested by simultaneous caregiving and care receiving, making it especially challenging, and perhaps arbitrary, to distinguish a caregiver from a care receiver in the context of a research study.

Figure 1.

Circles

- Caregiver, care recipient

- Arranged by generation. Senior people at top, youngest at bottom

- Care recipients circles are enlarged to ease visualization of current relationships

Arrows

- Direction depicts flow of resources/care

- Solid = direct caregiving of an ill relative

- Dash = indirect caregiving

- Shadow = historical direction of caregiving relationship (the way it used to be)

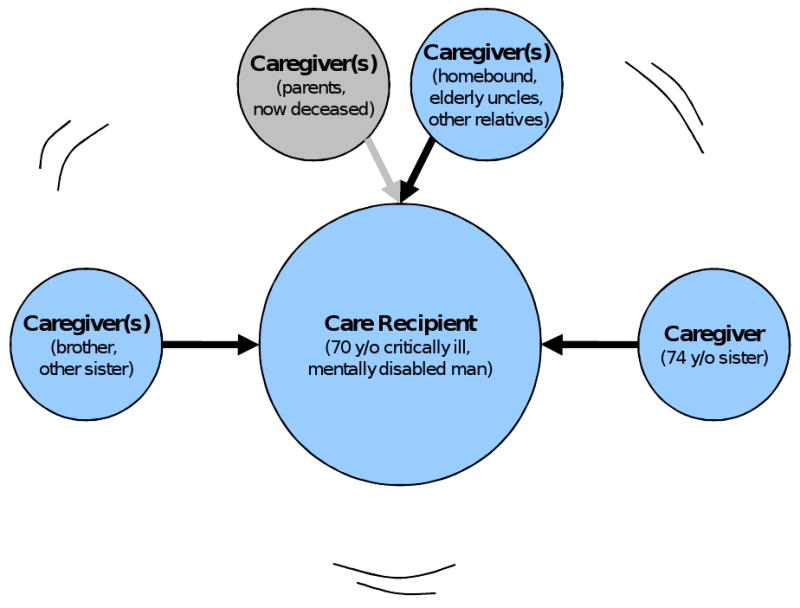

Case #2: A constellation of caregivers

This case is drawn from an ethnographic investigation of the processes of care and communication during ventilator weaning (grant # and PI omitted for blinded review). L.T. is a 70 year-old critically ill, mentally disabled African American man who suffered a pontine stroke 3 months ago and is now in ICU with aspiration pneumonia and sepsis. L.T.'s family caregiver and medical decision maker of record was his 74 year-old sister. Prior to the stroke, L.T.'s sister assisted him with medication-taking, shopping, and other instrumental activities of daily living, sharing caregiving duties with another sister, brother, and uncles (both biological and fictive kin). Given the comprehensive and chronic nature of L.T.'s care needs, duties were assumed and divided among this constellation of caregivers over time following the death of L.T.'s parents.

Exemplifying the limitations of a primary caregiver mindset on the part of clinicians, L.T.'s ICU treatment team could not understand his sister's delay in decision making about tracheostomy placement and were exasperated by her many questions about the issue. A nurse practitioner (NP) described an interaction in which L.T.'s sister called multiple times in one day asking many of the same questions that she had voiced earlier,

“She doesn't get it. She thinks he's going to get better. I mean she asked me how the tracheostomy would affect his eating. And, I said ‘was he eating before he came into the hospital?’ She said ‘no.’ And, I said ‘it's unlikely that he’ll be able to eat when he gets out of the hospital.’ She also wanted to know what the size of the scar would be. Finally, the sister said ‘I'll wait until you do something with the tube.’ (NP throws up her hands.) So I had to go back to ‘I can't remove the [endotracheal] tube until you decide to have the tracheostomy placed. If the tracheostomy isn't placed then I can't remove the [endotracheal] tube.’”

L.T.'s sister revealed, during a research interview, that she understood the need for tracheostomy, but was obliged to relay questions from their older, homebound aunts and uncles. These extended family members were key participants in the decision making and social support aspects of family caregiving, yet the clinicians never knew these people existed or what their position might be in the matriarchal family configuration.

While the caregiving literature generally recognizes that family members and other intimates of a patient may share care responsibilities (Usita, Hall, & Davis, 2004), few studies fully consider such dynamics (Fawdry, Berry, & Rajacich, 1996; Feld et al., 2006). Indeed, the shared care phenomenon is often described in the context of siblings or married couples who divide tasks associated with the care of a parent (Fawdry et al., 1996; Keith, 1995). The case of L.T. and his sister extends the construct of shared care, depicting a constellation of family caregivers who share tasks and may have significant input into treatment decisions. As shown in Figure 2, L.T.'s constellation of caregivers spans two generations and markedly departs from the widely studied notion of a primary spousal or adult child caregiver.

Figure 2.

Circles

- Caregiver, care recipient

- Arranged by generation. Senior people at top, youngest at bottom

- Care recipients circles are enlarged to ease visualization of current relationships

Arrows

- Direction depicts flow of resources/care

- Solid = direct caregiving of an ill relative

- Dash = indirect caregiving

- Shadow = historical direction of caregiving relationship (the way it used to be)

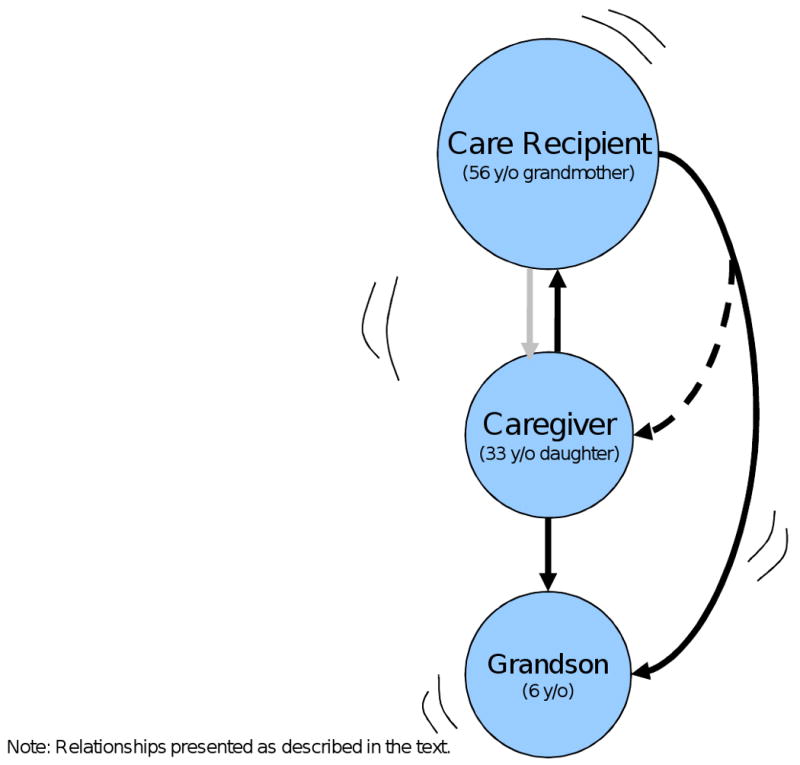

Case #3: An intergenerational family care chain

Ms. A is a 56 year-old African American woman with end stage renal disease who requires out-patient hemodialysis. She participates in a study to promote advance care planning and end-of-life decision making among African Americans (grant # and PI withheld for blinded review). Ms. A.'s 33 year-old daughter is her primary caregiver and she participates in the study as a designated surrogate decision-maker. Although Ms. A. is frail and has a serious life-threatening illness, she functions as caregiver for her 6 year-old grandson while her daughter is at work. One winter day, she missed dialysis because her scheduled taxi pick-up failed to show. Within 2 days of the missed session, she had fluid overload with pulmonary distress, necessitating a visit to the emergency room. In relating her experience she explains what an adventure it was for her grandson to accompany her,

“Oh he was so excited (Ms. A laughs). We got to the hospital, an' they gave me some oxygen which, you know, settles it. Put me in a room, brought him some books an' crayons an' stuff an' I mean it was…we just had a grand old time ‘til they did dialysis. Took me upstairs, he's in the bed with me, dialysis [staff] brought us food….”

In the literature, intergenerational caregiving usually refers to adult children caring for aging parents (e.g., Howe, Schofield, & Herrman, 1997; McGraw & Walker, 2004). Yet the reversal of this phenomenon, manifested as grandparents' involvement in child care, is common in urban communities (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2001; Pearson, Hunter, Cook, Ialongo, & Kellam, 1997), and the number of grandparents providing partial or full care support for their grandchildren continues to increase (Cooney & An, 2006; de Toledo & Brown, 1995; Hughes, Waite, LaPierre, & Luo, 2007). This form of intergenerational caregiving is distinguished in part by the fact that co-residence may be prompted by the younger, as opposed to the older, generation's housing and care needs. Ms. A.'s case is representative of what we have termed a family care chain in which a given individual functions as a caregiver to one relative, while at the same time being the recipient of care from another family member. Ms. A., who can be readily be identified as a patient for both clinical and research purposes, is at once a care recipient and a caregiver (Figure 3). Ms. A.'s case demonstrates that family care chains may continue even when a member of the chain develops a serious illness, yet such web-like, intergenerational care exchange patterns may not be appreciated fully under conventional constructions of the patient as care recipient.

Figure 3.

Circles

- Caregiver, care recipient

- Arranged by generation. Senior people at top, youngest at bottom

- Care recipients circles are enlarged to ease visualization of current relationships

Arrows

- Direction depicts flow of resources/care

- Solid = direct caregiving of an ill relative

- Dash = indirect caregiving

- Shadow = historical direction of caregiving relationship (the way it used to be)

Implications for Research and Practice

The bulk of nursing research on caregiving is predicated on the notion that a care recipient is a readily identifiable person who is functioning in a state of illness and dependency with the assistance of a single caregiver who is a relatively healthy, functionally independent individual. The cases presented above challenge central assumptions about informal caregiving and illustrate three main ways in which care dynamics may depart from traditional notions of dyadic, unidirectional family caregiving (Figures 1-3). First, aging and chronically ill couples may compensate for one another's deficits in reciprocal care relationships. Second, patients may be cared for by a constellation of family members and other informal caregivers (e.g., friends and neighbors), rendering arbitrary the identification of one primary caregiver. Third, family care chains exist whereby a given individual may function as a caregiver to one relative or friend and care-recipient to another. Although these dynamics are common in care situations, designs in most nursing research on caregiving do not accommodate them.

Inattention to the nature and extent of the impact of caregiving on the entire family unit severely limits caregiver research and may call into question the implications of study findings for nursing practice. At a basic level, the ways in which care demands affect caregivers' health and ability to maintain personal and social obligations cannot be determined fully. Descriptive studies may overestimate the impact of caregiving burden by limiting their subject pools to traditionally defined primary caregivers. Alternatively, researchers can underestimate the aggregate burden of caregiving by failing to capture shared care dynamics. Further, the quality of the full range of care that is provided may not be evaluated accurately, nor may the downstream effects of interventions. Interventions developed under the premise of a single primary caregiver may have limited applicability for nurses who are working to educate or support a constellation of caregivers. In addition, practicing nurses may be required to adapt empirically tested interventions to suit the needs of caregivers who are themselves chronically ill or functionally impaired. Yet, the evidence base for the nature and effectiveness of such adaptations is lacking.

In consideration of these limitations, several recommendations for future research can be made. Although it is infeasible to address all of these issues in a single study, including a more broadly based and comprehensive definition of family caregiver, as the following recommendations suggest, would advance the state of the science in caregiver research. Researchers aiming to realize the caregiving-related objectives of NINR's Strategic Plan may, in turn, maximize the relevance of their investigations to clinical nursing practice.

First, research questions should address the way in which relationships among multiple family members are affected by the care dynamic. There is a particular need for investigations to determine what happens to prior caregiving responsibilities and how care recipients are affected when an established caregiver experiences a decline in health or functional status. Second, studies to evaluate the quality of, or stress related to, care delivered by family caregivers should allow for differentiation among multiple caregivers. At minimum, data quantifying the number of family or other informal caregivers and their relationship to the care recipients should be gathered. Multiple caregivers can be tracked descriptively, treated as a covariate, or advanced quantitative methods can be used to evaluate the impact of multiple carers on caregiver and care recipient outcomes. Qualitative substudies can provide more comprehensive explanations of caregiving networks and their impact on the phenomena of interest. Finally, interventions that not only account for, but support, multiple care providers should be developed and evaluated. Multiple caregiver interventions might include train the trainer-inspired educational interventions in which one family member is selected, preferably by the family, to participate in a research study with the expectation that she or he will champion the intervention by extending the knowledge gleaned to other caregivers. Mixed methodological approaches may be particularly useful for evaluating the effects of interventions targeting family units.

Conclusion

These cases provide insight into such phenomena as multiple caregivers, shifting and shared caregiving roles, and care recipients as caregivers. As caregiving science enters a new era of complexity and maturity, research approaches must acknowledge and be responsive to the real experiences of family caregiving. It is with this breadth and depth of understanding that the NINR Strategic Plan to understand and improve the quality, experience, and outcomes of caregiving can be realized fully.

Acknowledgments

The cases presented in this manuscript were drawn from research supported by R01-NR07973 (PI: Happ), R21NR009662 (PI: Song), the Office of the Senior Vice-Chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh (PI: Sherwood), and a postdoctoral fellowship from The John A. Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Program (PI: Crighton).

Contributor Information

Jennifer Hagerty Lingler, Department of Health and Community Systems, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Paula R. Sherwood, School of Nursing and Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Margaret H. Crighton, Department of Acute/Tertiary Care, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Mi-Kyung Song, Department of Acute & Tertiary Care, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Mary Beth Happ, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- Almberg B, Grafstrom M, Winblad B. Major strain and coping strategies as reported by family members who care for aged demented relatives. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26(4):683–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13(6):375–384. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Miller LL, Harvath TA, Greenlick MR, Van Buren L, et al. The PREP system of nursing interventions: a pilot test with families caring for older members. Preparedness (PR), enrichment (E) and predictability (P) Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(1):3–16. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter KC, Hall GR, Kelly A, Sime AM, Richards B, Gerdner LA. PLST model-effectiveness for rural ADRD caregivers. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research; 1992. 5R01NR03234. [Google Scholar]

- Burr W. Contemporary theories about the family. New York: Free Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney TM, An JS. Women in the middle: Generational position and grandmothers' adjustment to raising grandchildren. Journal of Women & Aging. 2006;18(2):3–24. doi: 10.1300/J074v18n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Toledo S, Brown DE. Grandparents as parents: A survival guide for raising a second family. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fawdry MK, Berry ML, Rajacich D. The articulation of nursing systems with dependent care systems of intergenerational caregivers. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1996;9(1):22–26. doi: 10.1177/089431849600900107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld S, Dunkle RE, Schroepfer T, Shen HW. Expansion of elderly couples' IADL caregiver networks beyond the marital dyad. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2006;63(2):95–113. doi: 10.2190/CW8G-PB6B-NCGH-HT1M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M. American grandparents providing extensive child care to their grandchildren: prevalence and profile. Gerontologist. 2001;41(2):201–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given B, Given CW, Sikorskii A, Jeon S, Sherwood P, Rahbar M. The impact of providing symptom management assistance on caregiver reaction: Results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;32(5):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Greenley JR, Benedict P. Contributions of persons with serious mental illness to their families. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(5):475–480. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AL, Schofield H, Herrman H. Caregiving: A common or uncommon experience? Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(7):1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, LaPierre TA, Luo Y. All in the family: The impact of caring for grandchildren on grandparents' health. The Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2007;62(2):S108–S119. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith C. Family caregiving systems: Models, resources, and values. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kittay EF. Love's labor: Essays on women, equality, caring and dependency. London: Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lefley HP, Hatfield AB. Helping parental caregivers and mental health consumers cope with parental aging and loss. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(3):369–375. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Sayer AG, Whitlatch CJ. Caregiving as a dyadic process: Perspectives from caregiver and receiver. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(3):P195–P204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney DF, Tarlow BJ, Jones RN. Effects of an automated telephone support system on caregiver burden and anxiety: Findings from the REACH for TLC Intervention Study. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):556–567. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw LA, Walker AJ. Negotiating care: Ties between aging mothers and their caregiving daughters. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59(6):S324–S332. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.s324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Nursing Research. The NINR Strategic Plan for 2006-2010. 2007 August 14; Retrieved from http://www.ninr.nih.gov/AboutNINR/NINRMissionandStrategicPlan/

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJJ, Skiff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Hunter AG, Cook JM, Ialongo NS, Kellam SG. Grandmother involvement in child caregiving in an urban community. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(5):650–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2007;62(2):P126–P137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno RA, Patrick JH, Burant CJ. Mental health of aging women with children who are chronically disabled: examination of a two-factor model. The Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1996;51(6):S284–S296. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.6.s284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley W, Czaja S. Understanding the interventions process: a theoretical/conceptual framework for intervention approaches to caregiving. In: Schulz R, editor. Handbook on dementia caregiving: Evidenced-based interventions for family caregivers. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O'Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist. 1995;35(6):771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Beidler SM, Beeber AS, Gambino P. A transactional model of cancer family caregiving skill. Advances in Nursing Science. 2006;29(3):271–286. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolley JM, Reed D, Buckwalter KC. Caregiving appraisal and interventions based on the progressively lowered stress threshold model. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2002;17(2):110–120. doi: 10.1177/153331750201700211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. Female forms: Experiencing and understanding disability. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Disability status: 2000-Census 2000 brief. 2005 November 16; Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/disability/disabstat2k.html.

- Usita PM, Hall SS, Davis JC. Role ambiguity in family caregiving. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2004;23(1):20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Young HM, Teri L, Maiuro RD. Predictors of burden in spouse caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Psychology and Aging. 1991;6(3):392–402. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Young HM, Russo J. Burden: A review of measures used among caregivers of individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist. 1991;31(1):67–75. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykle ML. Interventions for family management of patients with Alzheimer's disease. International Psychogeriatrics. 1996;8(Suppl. 1):109–111. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296003195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]