Abstract

Background and Aims

The phenomenon of self-assembly, widespread in both the living and the non-living world, is a key mechanism in sporoderm pattern formation. Observations in developmental palynology appear in a new light if they are regarded as aspects of a sequence of micellar colloidal mesophases at genomically controlled initial parameters. The exine of Persea is reduced to ornamentaion (spines and gemmae with underlying skin-like ectexine); there is no endexine. Development of Persea exine was analysed based on the idea that ornamentation of pollen occurs largely by self-assembly.

Methods

Flower buds were collected from trees grown in greenhouses over 11 years in order to examine all the main developmental stages, including the very short tetrad period. After fixing, sections were examined using transmission electron microscopy.

Key Results and Conclusions

The locations of future spines are determined by lipid droplets in invaginations of the microspore plasma membrane. The addition of new sporopollenin monomers into these invaginations leads to the appearance of chimeric polymersomes, which, after splitting into two individual assemblies, give rise to both liquid-crystal conical ‘skeletons’ of spines and spherical micelles. After autopolymerization of sporopollenin, spines emerge around their skeletons, nested into clusters of globules. These clusters and single globules between spines appear on a base of spherical micelles. The intine also develops on the base of micellar mesophases. Colloidal chemistry helps to provide a more general understanding of the processes and explains recurrent features of pollen walls from remote taxa.

Keywords: Sporoderm development, exine, sporopollenin, self-assembly, micelles, liquid crystals, Persea americana

INTRODUCTION

The exine of Persea americana is reduced to ornamentation, consisting of spines and gemmae between spines (Hesse and Kubitzki, 1983). The participation of processes of self-assembly in exine development has been suggested (Collinson et al., 1993; Gabarayeva, 1993, 2000; Gabarayeva and Hemsley, 2006; Hemsley and Gabarayeva, 2007). One of the main suggestions in these studies is that the surface ornamentation of pollen grains appears almost by pure self-assembly, via autopolymerization of receptor-independent sporopollenin. It is reasonable to try to verify this hypothesis in Persea, which has an almost exineless sporoderm with a skin-like layer of ectexine and ornamentation – the only retained part of the exine.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Flower buds of Persea americana Mill. were collected from the greenhouses of the Komarov Botanical Institute, St.-Petersburg, over 11 years in order to examine all the main developmental stages, including a very short tetrad period. Material was fixed in 3 % glutaraldehyde and 2·5 % sucrose in 0·1 m cacodylate buffer, with addition of lanthanum nitrate (4 %) for better preservation of the plasma membrane glycocalyx, at pH 7·4, 20 °C, for 24 h. After post-fixation in 2 % osmium tetroxide (20 ° C, 4 h) and acetone dehydration, the samples were embedded in a mixture of Epon and Araldite. Ultrathin sections were contrasted with a saturated solution of uranyl acetate in ethanol and 0·2 % lead citrate. Sections were examined with a Hitachi H-600 transmission electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

An aniline blue-induced fluorescent test (Smith and McCully, 1978) was used to reveal callose; sections were examined with an Olympus BX 51 epifluorescence microscope. To assay for the possible presence of acid polysaccharides around the tetrad microspores, a cytochemical test was applied (Thiéry, 1967) with controls (Courtoy and Simar, 1974). To detect the plasma membrane and its glycocalyx (glycoproteins), sections were stained with phosphotungstic acid in 10 % chromic acid (Roland et al., 1972).

RESULTS

Pre-tetrad stage

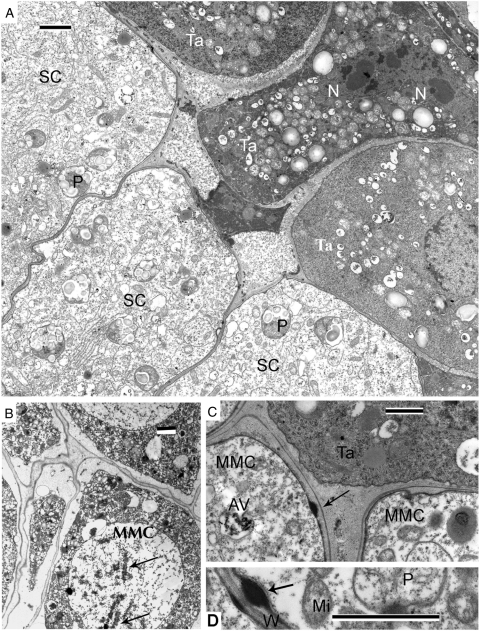

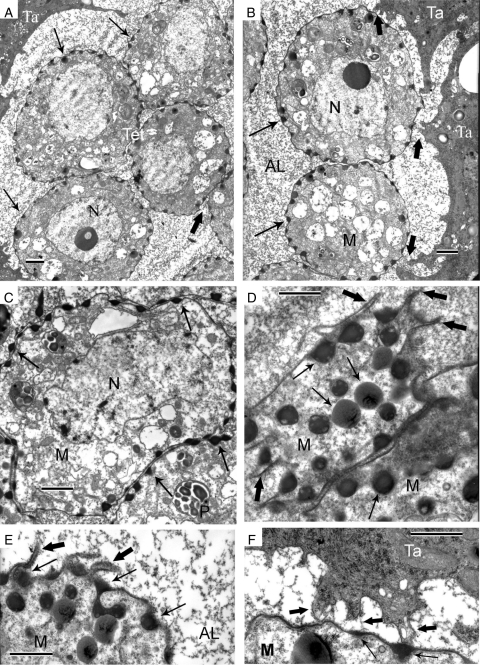

Sporogenous cells with angular outlines are present in the loculus of the anther and several tapetal cells (Fig. 1A). A few tightly packed sporogenous cells are observed in anther cross-sections. Binucleate tapetal cells have very dense cytoplasm and show much greater contrast than sporogenous cells (Fig. 1A). A large nucleus occupies the central part of sporogenous cells; an unusual feature of sporogenous cells is the presence of multiple plastids with well-formed starch grains. Another unusual feature is that microspore mother cells (MMCs) entering meiosis do not become rounded but retain their angular outlines; the same form persists during meiosis, for instance, in prophase (leptotene–zygotene) during formation of synaptonemal complexes (Fig. 1B, arrows). Droplets of an osmiophilic substance on the plasma membrane surface of MMCs are observed inside small invaginations (Fig. 1C, D, arrows). Some autolytic vacuoles, containing needle-like crystals, are scattered through the MMC cytoplasm (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Pre-tetrad stage in Persea americana. (A) Sporogenous cells (SC) with angular outlines inside the anther loculus and neighbouring tapetal cells (Ta). Two-nuclei tapetal cells show much stronger contrast than sporogenous cells. Plastids with well-formed starch grains (P). (B) Synaptonemal complexes in prophase (leptotene–zygotene) of meiosis (arrows) in microspore mother cell (MMC). The angular outlines of the cells persist. (C, D) Small droplets of an osmiophilic substance on the surface of MMCs (arrows). Some autolytic vacuoles (AV), containing needle-like crystals, are scattered through the MMC cytoplasm (C). Scale bars: (A, B) = 2 µm; (C, D) = 1 µm.

Tetrad period

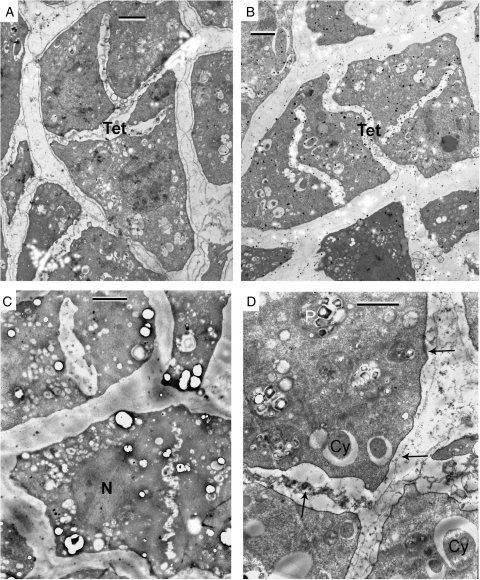

This period in P. americana is probably extremely short (which was why we had been tracking it for 11 years) and not typical in that the tetrads actually show no callose envelope and after staining with Aniline blue fluorescence around the tetrads or between microspores was not detected. As a result, the tetrads are not separated from each other and have the same angular outlines as sporogenous cells and MMCs. Cytokinesis is successive with centrifugal cleavage in both meiotic divisions. The planes of division in cytokinesis-II are perpendicular to each other and a planar (though not linear) tetrad is generated. It is difficult to distinguish dyads in sections from obliquely cut tetrads (see the centre of Fig. 2A, marked Dy), and only in some cases can one definitively visualize a dyad (right part of Fig. 2A, B) or obliquely cut tetrad (Tet, upper part of Fig. 2A, C). Only in cases where the plane of section more or less coincides with the plane of the tetrad can all four microspores be observed (Fig. 3A, B). Small osmiophilic droplets which accumulate on the surface of the plasma membrane are shown in Fig. 2D (arrows). No acid polysaccharides were observed (Fig. 3C). Traces of glycoproteins were detected in the middle plate, in the wall of former MMCs and on the plasma membrane of microspores (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 2.

Early tetrad stage in Persea americana. (A) Close-packed dyads and tetrads in the anther loculus. The initial angular form of sporogenous cells persists to this stage. (B) One dyad (Dy) in the anther loculus. There is little or no callose around the dyad. (C) A dyad (Dy) and a tetrad (Tet – three microspores are seen in this section) side by side. There is no callose around them and between the microspores. (D) Magnified upper part of B to show small, strong contrasted droplets on the plasmalemma surface (arrows). Scale bars = 2 µm.

Fig. 3.

Control (A, B) and cytochemical tests (C, D). (A, B) Planar tetrads in the process of formation. Cytokinesis is successive with centrifugal cleavage. The planes of division in cytokinesis-II are perpendicular to each other in a planar tetrad. There are no signs of callose. (C) Cytochemical Thiéry test for acid polysaccharides is negative. Section unstained. (D) Section stained with phosphotungstic acid in 10 % chromic acid (pH approx. 1). The positive contrasting is indicative of the presence of traces of glycoproteins in the middle plate, in the thin wall of the former microspore mother cells, and on the plasma membrane of microspores (arrows). Cy, cytosome; N, nucleus; P, plastid. Scale bars = 2 µm.

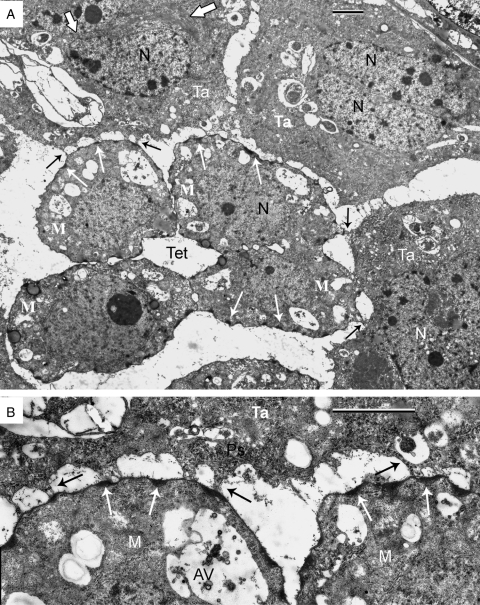

Multiple contacts of the tapetum with dissipating tetrads via strands are shown in Fig. 4A and B (black arrows). The sites of osmiophilic substance inside the microspore invaginations (Fig. 4A, B, thin white arrows) are associated with connective strands. In the cytoplasm of the tapetal cell (Fig. 4A, upper left corner) a bundle of hair-like structures is shown (delineated by thick white arrows); higher magnification reveals the tubular nature of these structures (Fig. 5A, B, enclosed between thick black arrows). In Fig. 5B (thin arrow), a tapetal outgrowth is in contact with high-contrast contents of the microspore invagination.

Fig. 4.

Multiple contacts of the tapetum (Ta) with dissipating tetrads. (A) The sites of contact (arrows) of tapetal cells with the microspore (M) surfaces via strands. In the cytoplasm of the tapetal cell (upper left corner) a bundle of hair-like structures is delineated by two thick white arrows. Thin white arrows show multiple periodic invaginations of the microspore plasma membrane, filled with an osmiophilic substance. (B) Note the association of many connective strands with invaginations of the microspore plasma membrane, filled with osmiophilic substance. AV, autolytic vacuole; Ps, polysomes in tapetal cytoplasm; Tet, tetrad; N, nucleus. Scale bars = 2 µm.

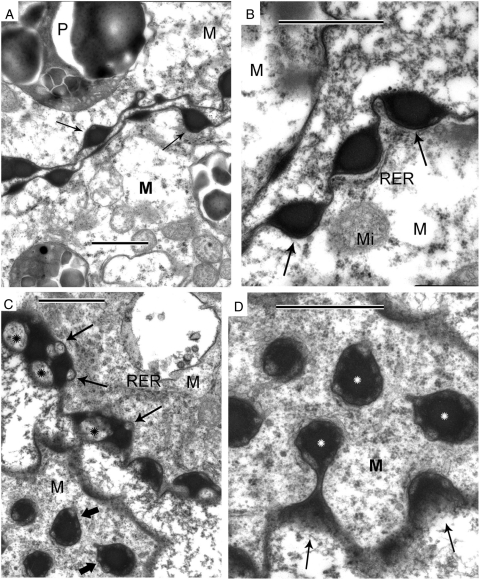

Fig. 5.

High-magnification images of tapetal cytoplasm. (A) Large bundles of hair-like structures (restricted by arrows) which are typically liquid crystals (or hexagonal mesophase of micelles). (B) Higher magnification (×1·4) reveals the tubular (cylindrical) nature of micelles (thick arrows). Thin arrow points to a tapetal outgrowth which is in contact with a microspore invaginated area, filled with osmiophilic substance. M, microspore; Ta, tapetum. Scale bars = 1 µm.

Tetrads on the point of disintegration and their close contacts with the tapetum are shown in Fig. 6. The four members of a planar tetrad are still close to each other, and they are in the vicinity of the tapetum (Fig. 6A). Periodic invaginations of the microspore plasma membrane are filled with osmiophilic substance (Fig. 6A–C, thin arrows). The former tetrads are still in contact with each other (Fig. 6A, thick arrow). Connective processes between microspores and tapetal cells persist in many places (Fig. 6B, thick arrows). If sectioned tangentially, microspore surface invaginations appear sunken in side view between connective strands (microspore processes; Fig. 6D, thick arrows) and appear circular in front view, filled with a dark substance (Fig. 6D, thin arrows). The microspore surface processes are particularly well seen in Fig. 6E (thick arrows) in association with dark inclusions inside surface invaginations (Fig. 6E, thin arrows). The contacts of these processes with tapetal outgrowths are shown in Fig. 6F (thick arrows).

Fig. 6.

Tetrads shortly before disintegration and their close contacts with tapetum. (A) The four members of a planar tetrad (Tet) are still close to each other, and they are in the vicinity of tapetum (Ta). Small periodic invaginations of the plasma membrane, filled with an osmiophilic substance, are shown by thin arrows. Note the contact with adjacent tetrad (thick arrow). N, nucleus. (B) Tapetal outgrowths in contact with two microspores of a former tetrad (thick arrows). Periodic invaginations with dark inclusions are indicated by thin arrows. AL, anther loculus; M, microspore. (C) The surfaces of adjacent microspores (M) are ‘inlayed’ with dark inclusions inside small invaginations (arrows). N, nucleus; P, plastid. (D) Tangential section through a microspore surface. Invaginations of the plasma membrane in side view are seen between the microspore surface processes, shown by thick arrows. Most invaginations, filled with a dark substance, are seen in front view and appear circular (thin arrows). (E) The border of a microspore with surface processes (thick arrows) and dark inclusions inside surface invaginations (thin arrows). (F) The outgrowths of the tapetum are in contact with the microspore processes (thick arrows); invaginations of the microspore surface, filled with osmiophilic substance, are observed at sites of contact between tapetum and the microspore (thin arrows). Scale bars: (A–C) = 2 µm; (D–F) = 1 µm.

Free microspore period

The plasma membrane of the young free microspores is regularly invaginated, and the invaginations have a cup-like form and are filled with osmiophilic droplets (Fig. 7A, B, arrows): these are sites of future exine spines. Slightly later osmiophilic contents of the invaginations are no longer homogeneous: some light vesicular inclusions with internal structure appear (Fig. 7C). (This phenomenon – the appearance of lighter areas inside the dark contents of the invaginations – was sometimes observed immediately before tetrad dissipation; see, for instance, Fig. 6D.) Tangentionally sectioned invaginations show weakly contrasted vesicles, located at the periphery of strongly contrasted droplets (Fig. 7C, lower microspore, thick arrows), but if cut obliquely (upper microspore), weakly contrasted vesicles are larger (indicating that they are flattened along the invagination walls – Fig. 7C, asterisks); several smaller vesicles appear on the point of being pinched off (Fig. 7C, thin arrows). The tangentionally sectioned microspore surface with heterogeneous droplets inside invaginations is shown at higher magnification in Fig. 7D (white asterisks).

Fig. 7.

Young free microspores. (A, B) Details of the microspore surface. Periodic invaginations (which are sites of future spines of exine) have a cup-like form, and they are filled with osmiophilic substance (arrows), most probably of lipoid nature. M, microspore cytoplasm; Mi, mitochondrion; P, plastid. (C) Two adjacent microspores at slightly later stage than in A and B, one sectioned tangentionally (left lower corner), the other centrally (right upper corner). Tangentionally sectioned invaginations with osmiophilic substance contain weakly contrasted vesicles, located on the periphery of strongly contrasted substance (thick arrows). In the upper microspores weakly contrasted vesicles are larger (asterisks), and several smaller vesicles appear to be on the point of pinching off (arrows). These are interpeted as chimeric polymersomes, a particular kind of micelle, formed of two hydrophobic block co-polymers. They are the base for formation of future spines. (D) Tangentionally sectioned microspore surface with chimeric polymersomes (white asterisks) in more detail. Scale bars = 1 µm.

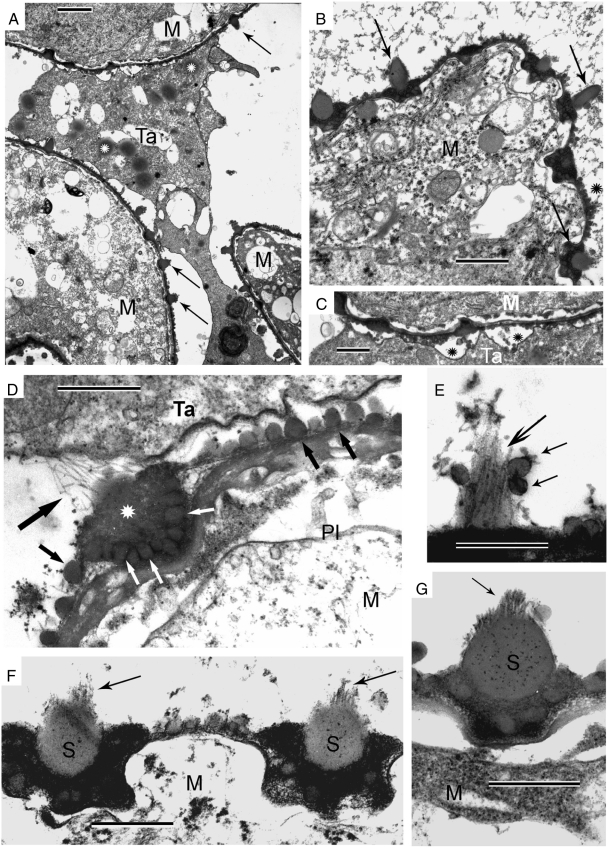

At the next developmental step, spines and gemmae appear on the microspore surface (Fig. 8). Tapetal cells invade between microspores and are in contact with the microspore surface (Fig. 8A). The developing spines are clearly visible (Fig. 8A, arrows). Lipoid globules (Fig. 8A, white asterisks) in the tapetal cytoplasm have a strongly contrasted core and a light halo. Higher magnification reveals spines, rooted into cup-like invaginations (Fig. 8B, arrows) and a thin electron-dense layer on the microspore surface, covered with spheroid gemmae (Fig. 8B, black asterisk). Clusters of spheroidal particles are observed between microspores and tapetal cells (Fig. 8C, asterisks). The initiation of spine formation is shown in Fig. 8D. The first step is the raising of a ‘bare armature’ (large arrow) of the future spine. This armature (or ‘skeleton’) is cone-like and built of long, rod-like units, with a diameter of about 15 nm. This skeleton of a future spine is rooted within a cluster of spherical globules: darker globules at the base of the invagination (Fig. 8D, white arrows) and more light and smaller globules in the centre (Fig. 8D, white asterisk). These globules appear at the base of the former osmiophilic droplets with weakly contrasted vesicles within (see Fig. 7C, D). Simultaneously, gemmae appear on the microspore surface (Fig. 8D, small black arrows). Later, new rods 15 nm in diameter are added to the initial rods, and these are orientared more or less perpendicular to the plasma membrane (Figs 8E–G and 9A). Sporopollenin accumulation around the spine ‘skeletons’ is first observed as a ‘cloud around the armature’ (Fig. 8E, large arrow). Some spherical globules often adhere to the forming spines (Fig. 8E, small arrows), while others cover the microspore surface between spines. As sporopollenin accumulates around the ‘armature’ (arrows), the latter becomes obscure and protrudes only on the tops of spines (Fig. 8F, G, arrows).

Fig. 8.

Spines and gemmae development on the microspore surface. (A) Fragments of three microspores (M) and a tapetal cell (Ta) invading between them. Arrows point to spines. Note lipoid globules (white asterisks) in the tapetal cytoplasm that have a strongly contrasted core and lighter halo. (B) A microspore fragment showing spines, rooted into cup-like invaginations (arrows), and a thin electron-dense layer on the microspore surface, covered with spheroid gemmae (black asterisk). (C) Magnified part of A, showing the border between microspore and tapetal cell. Note clusters of spheroid particles (asterisks) between the two cells and on the surface of the microspore. (D) Border between a tapetal cell (Ta) and a microspore (M). This marks the initiation of a spine formation. The first step is raising of ‘bare armature’ (large black arrow) of the future spine. This ‘armature’ is cone-like and built of long, rod-like units (most probably liquid-crystal in structure) comprising cylindrical micelles. Note that this skeleton of a future spine is rooted into a cup-like invagination of the microspore plasma membrane, filled at this ontogenetic stage with two kinds of spherical globules: darker ones at the base (white arrows) and lighter and smaller ones in the centre (white asterisk). These globules are spherical micelles and are formed from the two immiscible hydrophobic polymers that were revealed earlier in development as chimerical polymersomes (see Fig. 6C, D). Gemmae which appear on the microspore surface (small black arrows) are formed also on the base of spherical micelles. Pl, microspore plasma membrane. (E) Initiation of sporopollenin accumulation around liquid-crystal skeleton is observed as a ‘cloud around the armature’ (large arrow). Several spherical globules adhere to the forming spine (small arrows), the others covering the microspore surface. (F) Sporopollenin accumulation in progress; liquid-crystal ‘armature’ (arrows) protrudes from semi-mature spines (S). (G) Almost mature spine (S) with protruding liquid-crystal ‘skeleton’ on top (arrow). The spine is ‘nested’ into a cluster of large and small globules at its base. Scale bars: (A) = 2 µm; (B, C) = 1 µm; (D–G) = 0·5 µm.

Fig. 9.

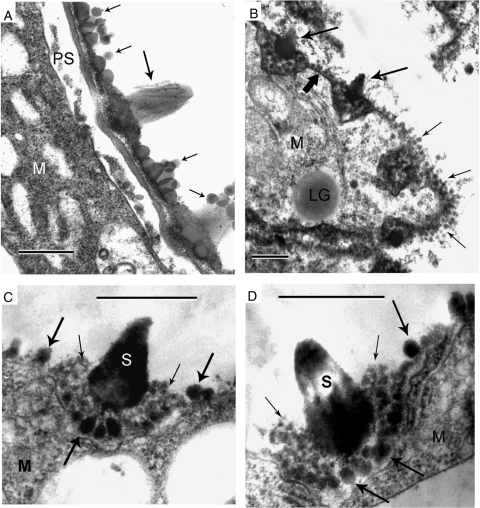

Maturation of the exine. (A) Mature ectexine, consisting of a thin sporopollenin layer, ornamented with spines (in some of which a liquid-crystal ‘armature’ is still visible through sporopolleninous accumulations – large arrow) and gemmae (small arrows). No endexine. The intine starts to develop in the periplasmic space (PS). (B) Spines (large arrows), some of them cross-sectioned, are uniformly distributed on the microspore surface at the sites of initial invaginations (see Figs 3 and 6). The microspore surface between spines is covered with a thin, skin-like ectexine (thick arrow) and gemmae (small arrows). LG, lipid globule. (C, D) Mature spines (S) nested into clusters of globules of different size. Large basal globules (large arrows) have formed, as well as gemmae between spines, on the base of larger spherical micelles. Smaller globules formed on the base of smaller spherical micelles (small arrows). Scale bars = 0·5 µm.

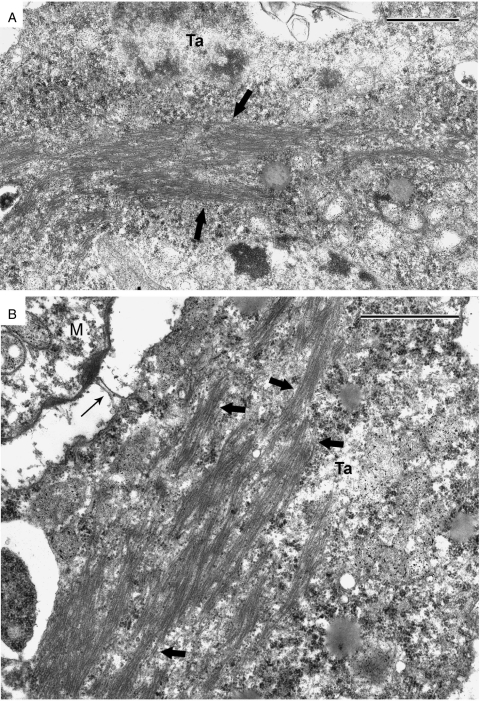

Mature ectexine consists of a thin, skin-like sporopollenin layer (Fig. 9B, thick arrow), ornamented with spines (Fig. 9A, B, large arrows); in some spines (Fig. 9A) the ‘armature’ is still visible through sporopollenin accumulations and gemmae (Fig. 9A, B, small arrows). Endexine does not appear. The intine starts to develop in the periplasmic space (Fig. 9A). Spines (Fig. 9B, large arrows) are uniformly distributed on the microspore surface in sites of initial invaginations (see Figs 3 and 6). Mature spines are nested within clusters of globules of different size: large basal globules (Fig. 9C, D, large arrows) and smaller globules (Fig. 9C, D, small arrows).

The first portion of intine appears as a network with strongly contrasted substance in its lumina (Fig. 10A, B). Remnants of the tapetum remain in association with the microspores. After completion of intine formation (the area shown by arrows in Fig. 10C, D) its distal part appears laminated, but the proximal part appears channelled (Fig. 10D).

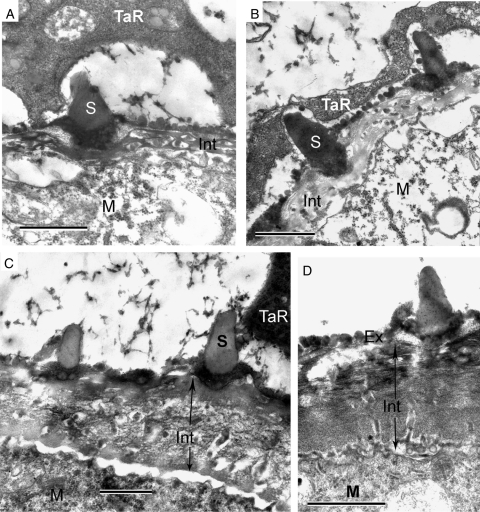

Fig. 10.

The formation of the intine. (A, B) The first portion of intine (Int) appears as a network with strongly contrasted substance in its lumina. Tapetal remnants (TaR) remain in association with the microspores. (C, D) The completion of intine formation (Int, the area shown by arrows). In D the distal part of the intine appears laminated, whereas the proximal part is channelled. This non-uniformity of the intine structure in A–D is based most probably on a combination of three transitive micelle mesophases: perforated layers (A, B), perforated layers plus cylindrical micelles (C), and neat (lamellar) micelles plus cylindrical micelles (D). Scale bars = 1 µm.

DISCUSSION

A further paradox: the exine that lacks exine

As shown here, the tetrad microspores of Persea americana lack callose and glycocalyx, the main prerequisites for ‘conventional’ exine development. As a consequence, the exine in P. americana pollen grains is represented mainly by ornamentation (spines and gemmae between spines), which appears earlier than the underlying very thin, skin-like layer of ectexine. There is no trace of endexine. Hence, the exine in Persea has to be considered as strongly reduced, an opinion that had previously been advanced (Hesse and Kubitzki, 1983; Hesse and Waha, 1983). The case of Persea is not unique: a remarkable resemblance exists between the exines of Laurales and some monocotyledons, members of Zingiberales (Stone et al., 1979; Kress and Stone, 1982; Furness and Rudall, 1999), reduced exines were examined in monocot Hydrocharitaceae and Nayadaceae (Tanaka et al., 2004), ontogeny of exineless pollen wall was investigated in the dicot Callitriche truncata with both aerial and underwater pollination (Osborn et al., 2001), and the most profound examples of virtually exineless pollen are well known in hydrophilous sea-grasses (see discussion in Hesse and Waha, 1983).

The consensus suggests that callose is necessary for normal pollen exine development (see Gabarayeva et al., 2009a). An example of calloseless tetrads (which were called tetrad-like), with subsequent well-developed exines of pollen grains in Pandanus odoratissimus reported by Periasamy and Amalathas (1991), but this work was carried out by using light microscopy only, with addition of a scanning electron micrograph, showing the surface of pollen grains. This case deserves more detailed investigation using transmission electron microscopy. However, most spore plants manage very well without callose around their tetrads and tetraspores (for a review see Gabarayeva and Hemsley, 2006), and heterosporous leptosporangiate ferns have developed to manage without the tetrad period entirely (Lugardon, 1990). We note, however, that most pollen walls are much more complicated in their microarchitecture than most spore walls (though with some exceptions). It was suggested that pattern formation of many spores proceeds mainly by self-assembly of colloidal units, and this hypothesis was strongly supported by experimental simulation of spore walls (Hemsley et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2009). In this respect (a dominant role of self-assembly in sporoderm development), exineless pollen grains have much in common with spores.

The development of ornamentation

The distribution of spines in Persea is linked to regularly located osmiophilic droplets on the microspore plasma membrane. The sites of accumulation of this osmiophilic substance, most probably lipid in nature, are predestined as early as in dyads and tetrads (Fig. 2D, arrows), and even earlier in MMCs (Fig. 1C, D, arrows). We suggest that a purely physical phenomenon causes the distribution of these lipoid droplets alongside the surface of the microspore plasma membrane. Oil droplets added to the surface of a sphere covered with a thin layer of water initially float as circular plates within the aqueous layer, but when they have sufficiently accumulated, these plates become more or less tightly packed and self-organize into a hexagonal pattern (D'Arcy Thompson, 1959). This is exactly what was observed in Persea: lipoid droplets, first randomly distributed in a thin hydrophilic layer of the microspore glycocalyx, when accumulated, self-assemble into a kind of hexagonal pattern (Fig. 6D). The same hydrophilic–hydrophobic relationship was suggested by Sheldon and Dickinson (1983) for Lilium exine patterning. It has been suggested that ontogenetic studies often reveal pre-patterned templates forming in the sporocyte (Wellman, 2003).

After determination of the sites of future spines around the cell surface the plasma membrane becomes more and more invaginated under lipoid droplets (Figs 4 and 6), and the latter increase in volume (Fig. 6). Plasma membrane invaginations at the early tetrad stage were considered to be the determining factor for reticulate (Takahashi, 1993, 1995a) and baculate (Takahashi, 1995b) exine patterns in a number of species. In Persea microspores the glycocalyx does not develop into a noticeable structure (some trace of the original structure is seen in tetrads by cytochemical means; Fig. 3D); nevertheless the supposition persists that tensional integrity (tensegrity) principles (Ingber and Jamieson, 1985; Ingber, 1993, 2003a, b) are involved in the appearance of invaginated sites of the tetrad microspore surface in many species. Hypotheses for a sequence of tensegrity events, starting with a pre-stressed cell, have been proposed (Southworth and Jernstedt, 1995; Gabarayeva et al., 2009a). The ordered distribution of the invaginated sites of the microspore surface is determined most probably by the ordered spatial distribution of cytoskeletal microfilaments and their contraction in the course of pre-stress.

After appearing, the periodic plasma membrane cup-like invaginations are filled with additional osmiophilic substance. This is a consequence of the close association between the tetrads and the tapetum; the latter invades between the tetrads and promotes their separation (Fig. 8A) – so-called secretory tapetum type with regrouping cells, one of a variety of subtypes of the secretory tapetum with subsequent reorganization (Kamelina, 1983). The importance of an even more unusual (periodic) close association between tapetal cells and microspore tetrads/free microspores in Nymphaea colorata has been reported and was termed cyclic-invasive (Rowley et al., 1992). Protrusions of the tapetal cells are correlated with lipid-containing invaginations and connected with the microspore processes (Figs 4 and 6B, F). These processes, or strands, connecting the developing microspores and tapetal cells have been described previously (El-Ghazaly et al., 2000; Rowley and Morbelli, 2009) as elongations of elementary units of exine; in ‘micelle language’ they correspond to cylindrical micelles or filaments. It is clear that the source of the lipoid substance are tapetal cells, their cytoplasm being packed with bundles of tubular structures (Fig. 5). Such tubular structures represent a typical hexagonal (so-called ‘middle’) mesophase of micelles – a type of nematic liquid crystals – of some diphilic substance (surfactant), probably sporopollenin precursors or monomers. In earlier studies (for schemes of the sequence of micelle mesophases and the types of liquid crystal, see figs 1–3 in Gabarayeva and Hemsley, 2006; figs 2–5 in Hemsley and Gabarayeva, 2007; fig. 1 in Gabarayeva et al., 2009a) we suggested that the development of the exine can be explained on the basis of colloidal chemistry, including high-molecular-weight colloids. It has been suggested that a scaffold of the future exines (glycocalyx) is a colloidal self-assembling system, originated from glycoprotein surfactants (Gabarayeva, 1993), and that this system self-develops (assuming that the concentration of surfactants increases), passing through a sequence of pseudostages (=mesophases), termed spherical, cylindrical, middle (layer) and laminate (bilayer) micelles. It is likely that sporopollenin precursors interfere with this process, promoting the change of normal micelles to reverse micelles and the appearance of liquid crystals; these are mainly nematic crystals in which rod-like units show no strict positional order, but commonly a large range of orientations. Sporopollenin precursors were shown to be released from the tapetum (Heslop-Harrison and Dickinson, 1969; Piffanelli et al., 1998). Nematic liquid crystals were discovered in tubulous chromoplasts (carotenoid-bearing plastids) from hips of Rosa rugosa (Sitte, 1981) and from fruits of Palisota barteri (Knoth et al., 1986), and also in the periplasmic space of tapetal cells in Michelia fuscata, in the sites of formation of sporopolleninous orbicules (Gabarayeva, 1986).

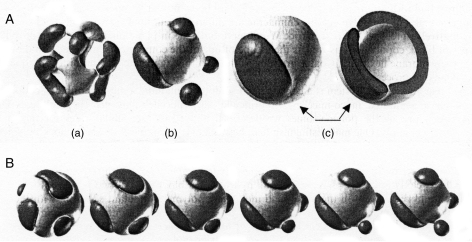

The change of homogeneous osmiophilic ‘droplets’ inside cup-like invaginations (Fig. 7A, B) to heterogeneous, vesicle-containing droplets (Fig. 7C, D), with some vesicles pinching off the droplets (Fig. 7D, thin arrows), is meaningful for all subsequent development: weakly contrasted zones are the basis for clusters of globules, and strongly contrasted zones are the basis for spines, rooted into them (Fig. 9C, D). Our suggestion is that what we observe as heterogeneous ‘droplets’ within plasma membrane invaginations are so-called chimeric polymersomes – a type of micelle. They are polymer composites that show ordered zones of at least two phases separated within one polymersome chimera (Fraaije et al., 2005). As in any classical chimera, the constituents exist in one unit, but remain separated. Polymer-based chimerae are intrinsically unstable; some polymersomes are very large (>10 µm in diameter). Recent study of the self-assembly of macroscopic sacs at the interface between two aqueous solutions, bearing opposite charges, showed the formation of a diffusion barrier upon their contact which prevents their chaotic mixing (Capito et al., 2008). Fraaije et al. (2005), using a computer simulation, examined two-component polymersome chimerae, a mixture of two diblock polymers, where the two hydrophobic blocks become demixed, and the hydrophilic blocks show different curvature preferences. ‘In this way, unstable domains or rafts are formed, which then lead to protrusions and invaginations’ (Fraaije et al., 2005, p. 356; emphasis added). The authors generated models of structures by quenching a homogeneous vesicular droplet of polymer surfactant in an aqueous bath. Their results are shown diagrammatically in Fig. 11, and they clearly demonstrate demixing of the two block copolymers. Figure 11 shows simulated two-component polymersome chimerae with different fractional composition of components, one of the components (black) pinching off vesicles. Figure 11B illustrates the time evolution of the domains for one composition ratio (50 %), where a small domain (black) also pinches off spherical micelles.

Fig. 11.

Diagrams of chimeric polymersomes (from Fraaije et al., 2005, with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry). (A,a–c) Two-component polymersome chimera, simulated with a dynamic variant of self-consistent field theory (Mesodyn); snapshots at τ = 5000. Fractional composition x = 0·25/0·50/0·75 (left to right, rightmost image is 75 % composition, but in open view). (B) Dynamics of formation of 50 % polymersome chimera (as in A,b). Snapshots at (from left to right) τ = 500, 1000, 2500, 3000, 3500, 4000 and 4500 (5000 in A,b).

Not only is the similarity of Fig. 7C, D with Fig. 11 (from the paper of Fraaije et al., 2005) striking (note that the images in Fig. 7 are sections of three-dimensional structures), but the essence of what is going on at this stage at the microspore surface is very likely the same. Surfactants are first synthesized in tapetal cells, where they form huge aggregates of nematic liquid crystals. They are then secreted through the outgrowths of tapetal cells and their contacts with microspore surface invaginations. Indeed, surfactants may represent two different constituents of the future sporopollenin, namely its aliphatic (long-chain and medium-chain fatty acids) and aromatic (hydroxycinnamic acids) monomers (Gubatz et al., 1986; Herminghaus et al., 1988; Hemsley et al., 1992, 1993, 1996a; van Bergen et al., 1993, 1995, 2004; Collinson et al., 1994; Kawase and Takahashi, 1995; Niester-Nyveld et al., 1997; Meuter-Gerhards et al., 1999; Azevedo Souza et al., 2009; Dobritsa et al., 2009) and phenylalanin as a precursor (Gubatz and Wiermann, 1992, 1993). Lipid metabolism and chain-elongating systems are also involved in sporopollenin biosynthesis (Wilmesmeier and Wiermann, 1995; Wiermann et al., 2001). Fraaije et al. (2005) have shown that domains or rafts are formed if the two hydrophobic blocks of diblock polymers have different chemical compositions, so that the polymers undergo phase separation in chimeric polymersomes, and if their hydrophilic blocks are of dissimilar length. When the phase separation is too strong, the polymers pinch off and individually form assemblies, such as spherical micelles and protrusions. This is exactly what we observe during ornamentation development in Persea. Initially homogeneous, then heterogeneous droplets inside invaginations (chimeric polymersomes of different chemical composition), being unstable, split into two individual assemblies: spherical micelles (future clusters of globules at the base of every spine) and spines themselves, starting with their ‘skeletons’ (Fig. 8D). Figure 8D is special in illustrating the moment of the switch: the framework (‘armature’) or skeleton of the spine is still ‘bare’ and consists of long, spiral rods arranged into a cone-like structure. These rods are liquid crystal formations, with cylindrical units arranged less regularly than those in smectic crystals. The conical form is widespread among true crystals; some properties of this form are preferential for stability. The skeletons of spines and clusters of spherical micelles at the base of spines are centres of nucleation for autopolymerization of new portions of sporopollenin monomers (Figs 8E–G and 9). Bundles of liquid crystal rods stick out of developing spines; the same images were observed in another representative of Laurales, Cinnamomum, by Rowley and Vasanthy (1993) and were referred to as substructure rods. Spine development in Ottelia (figs 2–4 and 6 in Takahashi, 1994) has much in common with that of Persea, and radially orientated rod-like structures are also seen in Ottelia in association with young spines (see fig. 3 in Takahashi, 1994).

Spherical or ovoid micelles (at the point of switching to a cylindrical form) within the slit between microspore and tapetal surfaces (Fig. 8C), when adhering to the microspore surface between spines (Fig. 8D), become additional centres of sporopollenin nucleation and turn into gemmae. An interesting feature is that gemmae have a toothed surface and appear cross-striped (Fig. 9C, D): this was also noted by Hesse and Kubitzki (1983). We interpret this feature as a manifestation of the hierarchical ornamentation of gemmae: small teeth on the gemmae surface are secondarily accumulated microglobules, shown, for instance, also for Caesalpinia (Takahashi, 1993); cross-striations are typical for cylindrical micelles (a synonym of ‘tufts’ by Rowley, 1990), and also for ovoid micelles (see, for instance, sculptured gemmae in Borago officinalis pollen grains; Rowley et al., 1999). In general, a hierarchical principle is widespread in exine structure (Blackmore et al., 2007). Interestingly, lamellated sheets which cover spines in Hibiscus (Takahashi and Kouchi, 1988, fig. 19) represent a typical lamellar phase of bicontinuous double-labyrinth structure (Ball, 1994; Hemsley and Gabarayeva, 2007, fig. 4B), with layers in parallel – a kind of complex micelle in which lipid- and water-based substances meet.

Of interest is that another kind of chimeric (or ‘hybrid’) micelle has been observed in early tetrad microspore development in Nymphaea colorata (figs 21–28 in Gabarayeva and Rowley, 1994) and Trevesia burckii (plate II, 6 in Gabarayeva et al., 2009a) as dark globules, associated with tubular rods (the whole structure resembling a tadpole). We are aware that chimeric micelles are unstable transitive forms between the main micelle mesophases (the latter are spherical, cylindrical micelles, layers of hexagonally packed cylinders – ‘middle’ mesophase, and double-layers with a gap between – ‘neat’ micelles). There are many other forms of micelles and their aggregates (figs 3–7 in Hemsley and Gabarayeva, 2007) and their transitive forms (Collinson et al., 1993) in living and non-living nature, including microsporal periplasmic space and its cytoplasm.

Regarding P. americana sporoderm development (which has neither glycocalyx nor callose) it should be stressed again that the presence of the microspore cell coating and of callose is necessary for development of normal, ‘conventional’ exine with infratectum (columellate etc.), a tectum and a foot layer (if present). The microspore cell coating (glycocalyx), because it plays a scaffolding role, is a template for exine development, through which sporopollenin receptors are probably species-specifically distributed. The callose, because it restricts a special narrow slit (an arena for the most important processes of the tetrad period), imposes necessary constraints in the periplasmic space, and may behave actively with respect to the adjacent macromolecular glycocalyx layer, promoting a structure-forming process at the interface (Gabarayeva and Hemsley, 2006; Blackmore et al., 2007; Gabarayeva et al., 2009a). Without glycocalyx and callose the best that could be expected is a structureless skin-like layer of exine plus surface ornamentation – the very thing we observe in Persea pollen. Recent data on callose-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis (Dong et al., 2005; Nishikawa et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2008) confirm that callose is necessary for normal exine development. Reduction or complete loss of the exine was shown in Callitriche truncata, where only a callose-like layer persists (Osborn et al., 2001). In the absence of callose, only lamellated endexine develops in the free microspore period in Ceratophyllum demersum (Takahashi, 1995c). The absence of callose in pollen mother cells and tetrads in the monocot Arum alpinum results in no primexine matrix (glycocalyx) and no ectexine (Anger and Weber, 2006). However, in Arum, unlike Persea, a thick endexine forms and is followed only by the appearance of polysaccharidic spines, which do not resist acetolysis. Arum also demonstrates that some special character of callose is crucial for ectexine formation. Another common feature of microspore pattern formation in Arum alpinum and Persea is that the tapetum invades between the microspores of the tetrads and separates them (secretory tapetum with reorganization). However, in Arum outlines of spines are literally determined by invaginations of the amoeboid tapetum (Anger and Weber, 2006), whereas the secretory tapetum of Persea, playing an active role in synthesis and delivery of sporopollenin monomers to the sites of spine locations, does not determine the form of spines. The latter arise largely by self-assembly, under initial genetically controlled precise conditions, for example, the chemical composition and concentrations of substances involved.

This point is strongly supported by mimics of spore/pollen surfaces, obtained in experiments with styrene (Hemsley et al., 1996b, 1998, 2003; Griffiths and Hemsley, 2002; Moore et al., 2009); these experiments clearly demonstrate that surface ornament does not need a template. It was impressive to see that these structures, which so closely resembled exospore or exine surfaces, were nothing but the result of adsorption of metallo-organic substances deposited by a chemical vapour-phase metallization method (see fig. 1 in Hemsley and Gabarayeva, 2007). The impressive results of Thom et al. (1998) on reassembly of dissolved sporopollenin into spherical and rod-like structures provide additional evidence for the capacity of sporopollenin for self-assembling and for its initial colloidal state. It should be noted that the patterns we recognize in palynology are not unique, but can be generated by physical and chemical processes, some of which may have little to do with the organisms. We suggest that sporopollenin accumulates in Persea microspores without sporopollenin receptors, by autopolymerization of so-called receptor-independent sporopollenin (Rowley and Claugher, 1991).

Pollen grains of another member of Araceae – Sauromatum– completely lack ectexine, but have thick spongy endexine and spines which are polyssacharidic (Weber et al., 1998). Careful examination of figs 7–10 in Weber et al. (1998) reveals the gradual accumulation of spherical particles and fragments of ‘white lines’ in the area of spine formation. We suggest that these are spherical micelles and lamellate (neat) micelles (with their bilayers separated by a gap), participating in spine formation; it is possible that spongy endexine has been formed on the base of perforated laminae as on one of the transitive forms of micelles. Spines of angiosperm pollen are not considered to be homologous with each other, either in development or in chemical composition (Pacini and Juniper, 1983; Takahashi and Kouchi, 1988; Takahashi, 1992, 1994; Weber et al., 1998). However, it appears that irrespective of the ontogenetic moment of spine initiation, their locations and their chemical composition, self-assembly of micelles is the basis for their development. Micelle self-assembly initiates at any locus where diphilic substances appear in sufficient concentration, and if the concentration increases, the system passes through the sequence of mesophases and their transitive forms. This is most probably the reason for the well-known phenomenon of similarity of ornamentation on pollen grains and orbicules (Ubisch bodies). In fact, the same surface structures appear on any suitable surface: pollen surfaces, anther walls or orbicule surfaces.

Using a freeze-fracture method, Takahashi (1993, 1995a) showed that initial parts of exine in an early tetrad stage consisted of an association of fibrous threads and granules, and his conclusion was that these data conflicted with the previous data on exine development in Lilium of Dickinson (1970), Nakamura (1979) and Dickinson and Sheldon (1986): these authors had shown the initial appearance of radially orientated rods or membranes. We suggest that these two groups of data do not contradict each other. We interpet granules, gradually aggregating to fibrous threads (observed by Takahashi), as spherical micelles, forming strings (a transitive form to filaments): radially orientated rod-like units (observed by Dickinson, by Nakamura and by Dickinson and Sheldon) are just the next micelle mesophase – filaments, or cylindrical micelles, with subsequent sporopollenin accumulations.

Echinate exine ornamentation (as well as other main ornamentation types: reticulate, striate, verrucate) is widespread among angiosperms. In most cases there is enough genetic control to distinguish different species on the basis of their pollen/spores, but shared physical and chemical constraints and similar components of such self-assembly systems probably account for the widespread phenomenon of convergence of patterns from remote taxa, for instance the occurrence of reticulate and polygonal patterns in living and non-living nature (Scott, 1994), as well as such prominent features as spines (Hemsley et al., 2000). Self-assembly mechanisms have an effect in reiterating similar patterns, which is an inevitable consequence of their non-linear nature (for more detail see Hemsley, 1998; Gabarayeva et al., 2009b). The implications of the non-linear nature of the processes involved in sporoderm ontogeny are that assessment of phylogeny based on a comparison of the genetic code would differ partly from that based on morphology.

Intine formation

The sporopollenin-free part of the Persea sporoderm (mainly channelled) was described as intine by Hesse and Kubitzki (1983), but Rowley and Vasanthy (1993) reported analogous channelled layers in closely related species of Cinnamomum as a specific onciform zone, considering only a thin fibrillar basal layer which was introduced following microspore mitosis as true intine. Here we put aside this question of terminology, because it is far from being decisive in this paper; our aim was to clarify the underlying cause of developmental events.

Hesse and Kubitzki (1983) reported the existence of a bilayered intine in Persea americana: the outer thick channelled layer and slightly laminated basal layer. Figure 10C, D show that the outer layer is laminated, but the basal layer is channelled. In our opinion, there is no inconsistency in these two sets of data. We suggest that everything observed in the periplasmic space of immature pollen is semi-liquid, and that intine, just as exine, develops most probably on the base of micelles. Micellar mesophases are very labile and easily switch from one to another, especially inside the sporopollenin-free part of the sporoderm. What is observed as a network in Fig. 10A, B is evidently a transitive micellar form – a perforated layer; the ‘white lines’ in Fig. 10D are lamellate (neat) micelles with their gaps between bilayers; radially orientated channels (Fig. 10C, D) form on a base of cylindrical micelles. In the narrow periplasmic space, at the wavy plasma membrane in Fig. 10D (‘basal intine layer’ of Hesse and Kubitzki; ‘true intine’ of Rowley and Vazanthy), spherical units are seen – the first micellar mesophase, spherical micelles. This suggests that the intine is not yet completed and is not at the final stage of its development. Therefore, it depends on the moment of fixation as to which exact combination of micelle mesophases is captured.

CONCLUSIONS

There is no callose and no glycocalyx in Persea americana microspores during the tetrad period. As a result, the exine is represented mainly by ornamentation (spines and gemmae between spines), which appear earlier than the underlying very thin, skin-like layer of ectexine. There is no endexine.

The distribution of the future spines corresponds to regularly located lipoid droplets and invaginations of the microspore plasma membrane under these droplets. The distribution of these lipoid droplets along the surface of the microspore plasma membrane is a result of purely physical hydrophilic–hydrophobic interactions. The suggestion is that tensegrity (another self-assembling process) is involved in the appearance of the invaginations.

Heterogeneous droplets inside invaginations are most probably chimeric polymersomes, a kind of unstable micelle, in which at least two different components (presumably sporopollenin precursors) are phase-separated. Subsequent splitting of these into two individual assemblies leads to the appearance of both spherical micelles (future clusters of globules at the base of every spine) and liquid-crystal ‘skeletons’ of future spines.

After gradual accumulation of sporopollenin within the liquid-crystal ‘backbone’ of spines and on the surface of spherical micelles, spines, nested within clusters of globules, and surface gemmae appear. Accumulation of sporopollenin proceeds without receptors, by autopolymerization of receptor-independent sporopollenin.

The tapetum plays an important role during microspore development. It supplies microspores with sporopollenin monomers and nutritive substances, invades between microspores at the end of the tetrad period and persists in close contact with them.

The intine is heterogeneous and consists of several layers. These layers develop on the base of several sequential micelle mesophases.

Micelle self-assembly is the basic mechanism for development of exine (= ornamentation in Persea) and intine. It is highly probable that the genome of P. americana determines the synthesis of necessary substances (glycoproteins for glycocalyx, sporopollenin precursors, etc.) at definite concentrations and ratios, with their subsequent secretion into particular sites. The remaining processes are self-assembling.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by RFBR grant No. 08-04-00498. We thank our engineer Peter Tzinman for assistance with transmission electron microscopy, and Nikolay Arnautov for permission to use the material from the Komarov Institute greenhouses.

LITERATURE CITED

- Anger E, Weber M. Pollen wall formation in Arum alpinum. Annals of Botany. 2006;97:239–244. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcj022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo Souza C, Kim SS, Koch S, et al. A novel fatty acyl-CoA synthetase is required for pollen development and sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2009;21:507–525. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball P. Designing the Molecular World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1994. pp. 216–255. [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen PF, Collinson ME, de Leeuw JW. Chemical composition and ultrastructure of fossil and extant salvinialean microspore massulae and megaspores. Grana Supplement. 1993;1:18–30. [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen PF, Collinson ME, Briggs DEG, et al. Resistant biomacromolecules in the fossil record. Acta Botanica Neerlandica. 1995;44:319–342. [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen PF, Blokker P, Collinson ME, Sinninghe Damsté JS, de Leeuw JW. Structural biomacromolecules in plants: what can be leant from the fossil record? In: Hemsley AR, Poole I, editors. The evolution of plant physiology. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 134–154. Linnean Society Symposium Series 21. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore S, Wortley AH, Skvarla JJ, Rowley JR. Pollen wall development in flowering plants. New Phytologist. 2007;174:483–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capito RM, Azevedo HS, Velichko YS, Mata A, Stupp SI. Self-assembly of large and small molecules into hierarchically ordered sacs and membranes. Science. 2008;319:1812–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.1154586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson ME, Hemsley AR, Taylor WA. Sporopollenin exhibiting colloidal organization in spore walls. Grana Supplement. 1993;1:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson ME, van Bergen PF, Scott AC, de Leeuw JW. The oil-generating potential of plants from coal and coal-bearing strata through time: a review with new evidence from Carboniferous plants. In: Scott AC, Fleet AJ, editors. Coal and coal-bearing strata as oil-prone source rocks? London: The Geological Society Special Publication 77; 1994. pp. 31–70. [Google Scholar]

- Courtoy R, Simar LJ. Importance of controls for the demonstration of carbohydrates in electron microscopy with silver methenamin or the thiocarbohydrazide-silver proteinate methods. Journal of Microscopy. 1974;100:199–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1974.tb03929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Arcy Thompson W. Growth and form. 2nd edn. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson HG. Ultrastructural aspects of primexine formation in the microspore tetrad of Lilium longiflorum. Cytobiologie. 1970;1:437–449. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson HG, Sheldon JM. The generation of patterning at the plasma membrane of the young microspore of Lilium. In: Blackmore S, Ferguson IK, editors. Pollen and spores: form and function. London: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dobritsa AA, Shrestha J, Morant M, et al. CYP704B1 is a long-chain fatty acid ω-hydroxylase essential for sporopollenin synthesis in pollen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2009;151:574–589. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.144469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XY, Hong ZL, Sivaramakrichnan M, Mahfouz M, Verma MPS. Callose synthase (CalS5) is required for exine formation during microgametogenesis and for pollen viability in Arabidopsis. Plant Journal. 2005;42:315–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghazaly G, Moate R, Huysmans S, Skvarla J, Rowley JR. Selected stages in pollen wall development in Echinodorus, Magnolia, Betula, Rondeletia, Borago and Matricaria. In: Harley MM, Morton CM, Blackmore S, editors. Pollen and spores: morphology and biology. Whitstable, UK: Whitstable Printers Ltd; 2000. pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fraaije JGEM, van Sluis CA, Kros A, Zvelindovsky AV, Sevink GJA. Design of chimaeric polymersomes. Faraday Discussions. 2005;128:355–361. doi: 10.1039/b403187c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness CA, Rudall PJ. Inaperturate pollen in monocotyledons. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 1999;160:395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI. The development of exine in Michelia fuscata (Magnoliaceae) in connection with changes of cytoplasmic organelles and tapetum. Botanicheski Zhurnal. 1986;71:311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI. Hypothetical ways of exine pattern determination. Grana. 1993;33(supplement 2):54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI. Principles and recurrent themes in sporoderm development. In: Harley MM, Morton CM, Blackmore S, editors. Pollen and spores: morphology and biology. Whitstable, UK: Whitstable Printers Ltd; 2000. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI, Hemsley AR. Merging concepts: the role of self-assembly in the development of pollen wall structure. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 2006;138:121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI, Rowley JR. Exine development in Nymphaea colorata (Nymphaeaceae) Nordic Journal of Botany. 1994;14:671–691. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI, Grigorjeva VV, Rowley JR, Hemsley AR. Sporoderm development in Trevesia burckii (Araliaceae). I. Tetrad period: further evidence for participation of self-assembly processes. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 2009a;156:211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarayeva NI, Grigorjeva VV, Rowley JR, Hemsley AR. Sporoderm development in Trevesia burckii (Araliaceae). II. Post-tetrad period: further evidence for participation of self-assembly processes. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 2009b;156:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths PC, Hemsley AR. Raspberries and muffins – mimicking biological pattern formation. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2002;25:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gubatz S, Wiermann R. Studies on sporopollenin biosynthesis in Tulipa anthers. 3. Incorporation of specifically labeled C-14 Phenylalanine in comparison to other precursors. Botanica Acta. 1992;105:407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Gubatz S, Wiermann R. Studies on sporopollenin biosynthesis in Cucurbita maxima. 1. The substantial labeling of sporopollenin from Cucurbita maxima after application of [C-14] Phenylalanine. Journal of Biosciences. 1993;48:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gubatz S, Herminghaus S, Meurer B, Strack D, Wiermann R. The location of hydroxycinnamic acid amides in the exine of Corylus pollen. Pollen and Spores. 1986;28:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR. Nonlinear variation in simulated complex pattern development. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1998;192:73–79. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Gabarayeva NI. Exine development: the importance of looking through a colloid chemistry ‘window. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2007;263:25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Chaloner WG, Scott AC, Groombridge CJ. Carbon-13 solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance of sporopollenins from modern and fossil plants. Annals of Botany. 1992;69:545–549. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Barrie PJ, Chaloner WG, Scott AC. The composition of sporopollenin and its use in living and fossil plant systematics. Grana Supplement. 1993;1:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Scott AC, Barrie PJ, Chaloner WG. Studies of fossil and modern spore wall biomacromolecules using 13C solid state NMR. Annals of Botany. 1996a;78:83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Jenkins PD, Collinson ME, Vincent B. Experimental modelling of exine self-assembly. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1996b;121:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Vincent B, Collinson ME, Griffiths PC. Simulated self-assembly of spore exines. Annals of Botany. 1998;82:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Collinson ME, Vicent B, Griffiths PC, Jenkins PD. Self-assembly of colloidal units in exine development. In: Harley MM, Morton CM, Blackmore S, editors. Pollen and spores: morphology and biology. Whitstable, UK: Whitstable Printers Ltd; 2000. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley AR, Griffiths PC, Mathias R, Moore SEM. A model for the role of surfactants in the assembly of exine sculpture. Grana. 2003;42:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Herminghaus S, Gubatz S, Arendt S, Wiermann R. The occurrence of phenols as degradation products of natural sporopollenin – a comparison with ‘synthetic sporopollenin. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 1988;43c:491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J, Dickinson HG. Time relationships of sporopollenin synthesis associated with tapetum and microspores in Lilium. Planta. 1969;84:199–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00388106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M, Kubitzki K. The sporoderm ultrastructure in Persea, Nectandra, Hernandia, Gomortega and some other Lauralean genera. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1983;141:299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M, Waha M. The fine structure of the pollen wall in Strelitzia reginae (Musaceae) Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1983;141:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D. Cellular tensegrity: defining new rules of biological design that govern the cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Science. 1993;104:613–627. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.3.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Tensegrity I. Cell structure and hierarchical systems biology. Journal of Cell Science. 2003a;116:1157–1173. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Tensegrity II. How structural networks influence cellular information processing networks. Journal of Cell Science. 2003b;116:1397–1408. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE, Jamieson JD. Cells as tensegrity structures: architectural regulation of histodifferentiation by physical forces transduced over basement membrane. In: Andersson LC, Gahmberg CG, Ekblom P, editors. Gene expression during normal and malignant differentiation. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kamelina OP. Basic results on the comparative embryological investigation of Dipsacaceae and Moriniaceae. In: Erdelska O, editor. Fertilization and embryogenesis in ovulated plants. Bratislava: Veda; 1983. pp. 343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kawase M, Takahashi M. Chemical composition of sporopollenin in Magnolia grandiflora (Magnoliaceae) and Hibiscus syriacus (Malvaceae) Grana. 1995;34:242–245. [Google Scholar]

- Knoth R, Hansmann P, Sitte P. Chromoplasts of Palisota bacteri, and the molecular structure of chromoplast tubules. Planta. 1986;168:167–174. doi: 10.1007/BF00402960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress WJ, Stone DE. Nature of the sporoderm in monocotyledons, with special reference to the pollen grains of Canna and Heliconia. Grana. 1982;21:129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lugardon B. Pteridophyte sporogenesis: a survey of spore wall ontogeny and fine structure in a polyphyletic plant group. In: Blackmore S, Knox RB, editors. Microspores: evolution and ontogeny. London: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Meuter-Gerhards A, Riegert S, Wiermann R. Studies on sporopollenin biosynthesis in Cucurbita maxima (Duch.). II. The involvement of aliphatic metabolism. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1999;154:431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SEM, Gabarayeva N, Hemsley AR. Morphological, developmental and ultrastructural comparison of Osmunda regalis L. spores with spore mimics. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 2009;156:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S. Development of the pollen grain wall in Lilium longiflorum. Journal of Electron Microscopy. 1979;28:275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Niester-Nyveld C, Haubrich A, Kampendonk H, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of phenolic compounds in pollen walls using antibodies against p-coumaric acid coupled to bovine serum albumin. Protoplasma. 1997;197:148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa S, Zinkl GM, Swanson RJ, Maruyama D, Preuss D. Callose (β- 1, 3 glucan) is essential for Arabidopsis pollen wall patterning, but not tube growth. BMC Plant Biology. 2005;5:22–30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JM, El-Ghazaly G, Cooper RL. Development of the exineless pollen wall in Callitriche truncata (Callitrichaceae) and the evolution of underwater pollination. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2001;228:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pacini E, Juniper BE. The ultrastructure of the formation and development of the amoeboid tapetum in Arum italicum Miller. Protoplasma. 1983;117:116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy K, Amalathas J. Absence of callose and tetrad in the microsporogenesis of Pandanus odoratissimus with well-formed pollen exine. Annals of Botany. 1991;67:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Piffanelli P, Ross JHE, Murphy DJ. Biogenesis and function of the lipidic structures of pollen grains. Sexual Plant Reproduction. 1998;11:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Roland J-C, Lembi CA, Morré DJ. Phosphotungstic acid – cromic acid as a selective electron-dense stain for plasma-membranes of plant cells. Stain Technology. 1972;47:195–200. doi: 10.3109/10520297209116484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JR. The fundamental structure of the pollen exine. Plant Systematics and Evolution Supplement. 1990;5:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JR, Claugher D. Receptor-independent sporopollenin. Botanica Acta. 1991;104:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JR, Morbelli MA. Connective structures between tapetal cells and spores in Lycophyta and pollen grains in angiosperms – a review. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 2009;156:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JR, Vasanthy G. Exine development, structure, and resistance in pollen of Cinnamomum (Lauraceae) Grana Suppement. 1993;2:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JR, Gabarayeva NI, Walles B. Cyclic invasion of tapetal cells into loculi during microspore development in Nymphaea colorata (Nymphaeaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1992;79:801–808. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JR, Skvarla JJ, Gabarayeva NI. Exine development in Borago (Boraginaceae). 2. Free microspore stages. Taiwania. 1999;44:212–229. [Google Scholar]

- Scott RJ. Pollen exine – the sporopollenin enigma and the physics of pattern. In: Scott RJ, Stead MA, editors. Society for Experimental Biology Seminar Series 55: Molecular and cellular aspects of plant reproduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon JM, Dickinson HG. Determination of patterning in the pollen wall of Lilium henryi. Journal of Cell Science. 1983;63:191–208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.63.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitte P. Role of lipid self-assembly in subcellular morphogenesis. In: Kiermayer O, editor. Cytomorphogenesis in plants. Cell Biology Monographs. vol. 8. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1981. pp. 401–421. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MM, McCully ME. A critical evaluation of the specificity of aniline blue induced fluorescence. Protoplasma. 1978;95:229–254. [Google Scholar]

- Southworth D, Jernstedt JA. Pollen exine development precedes microtubule rearrangement in Vigna unguiculata (Fabaceae): a model for pollen wall patterning. Protoplasma. 1995;187:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stone DE, Sellers SC, Kress WJ. Ontogeny of exineless pollen in Heliconia, a banana relative. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1979;66:701–730. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Masaoka K, Nishi M, Nakamura K, Ishiguro S. Identification of kaonashi mutants showing abnormal pollen exine structure in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2008;49:1465–1477. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Development of spinous exine in Nuphar japonicum De Candolle (Nymphaeaceae) Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 1992;75:317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Exine initiation and substructure in pollen of Caesalpinia japonica (Leguminosae: Caesalpinioideae) American Journal of Botany. 1993;80:192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Pollen development in a submerged plant, Ottelia alismoides (L.) Pers. (Hydrocharitaceae) Journal of Plant Research. 1994;107:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Three-dimensional aspects of exine initiation and development in Lilium longiflorum (Liliaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1995a;82:847–854. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Exine development in Aucuba japonica Thunberg (Cornaceae) Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 1995b;85:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Development of structure-less pollen wall in Ceratophyllum demersum L. (Ceratophyllaceae) Journal of Plant Research. 1995c;108:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Kouchi J. Ontogenetic development of spinous exine in Hibiscus syriacus (Malvaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1988;75:1549–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Uehara K, Murata J. Correlation between pollen morphology and pollination mechanisms in the Hydrocharitaceae. Journal of Plant Research. 2004;117:265–276. doi: 10.1007/s10265-004-0155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiéry J-P. Mise en évidence des polysaccharides sur coupes fines en microscopie électronic. Journal de Microscopie. 1967;6:987–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Thom I, Grote M, Abraham-Peskir J, Wiermann R. Electron and X-ray microscopic analyses of reaggregated materials obtained after fractionation of dissolved sporopollenin. Protoplasma. 1998;204:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M, Halbritter H, Hesse M. The spiny pollen wall in Sauromatum (Araceae) – with special reference to the endexine. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 1998;159:744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman CH. Origin, function and development of the spore wall in early land plants. In: Hemsley AR, Poole I, editors. The evolution of plant physiology. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; 2003. pp. 43–63. Linnean Society Symposium Series 21. [Google Scholar]

- Wiermann R, Ahlers F, Schmitz-Thom I. Sporopollenin. In: Hofrichter M, Steinbüchel A, editors. Biopolymers – lignin, humic substances and coal. Vol. 1. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmesmeier S, Wiermann R. Influence of EPTC (S-ethyl-dipropyl-thiocarbamate) on the composition of surface waxes and sporopollenin structure in Zea mays. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1995;146:22–28. [Google Scholar]