Abstract

Background

Early stage bladder cancer is a heterogeneous disease with a variable risk of progression and mortality. Uncertainty surrounding the optimal care for these patients may result in a mismatch between disease risk and treatment intensity.

Methods

Using SEER-Medicare data, we identified patients diagnosed with early stage bladder cancer (n= 24,980) between 1993 and 2002. We measured patients’ treatment intensity by totaling all Medicare payments made for bladder cancer in the two years after diagnosis. Using multiple logistic regression, we assessed relationships between clinical characteristics and treatment intensity. Finally, we determined the extent to which a patient’s disease risk matched with their treatment intensity.

Results

The average per capita expenditures increased from $6,936 to $7,642 over the study period (10.2% increase; p < 0.01). This increase was driven by greater use of intravesical therapy (2.6 versus 3.7 instillations per capita, p < 0.01) and physician office visits (3.0 versus 4.8 visits per capita, p < 0.01). Generally, treatment intensity was appropriately aligned with many clinical characteristics, including age, comorbidity, and tumor stage and grade. However, treatment intensity matched disease risk for only 55% and 49% of the lowest and highest risk patients, respectively.

Conclusions

The initial treatment intensity of early stage bladder cancer is increasing, primarily through greater use of intravesical therapy and office visits. Treatment intensity matches disease risk for many, but up to 1 in 5 patients may receive too much or too little care, suggesting opportunities for improvement.

Keywords: Urinary Bladder Neoplasms, Health Expenditures, Cost Savings, Guideline Adherence

Introduction

Early stage (i.e., superficial, or non-muscle invasive) bladder cancer is a heterogeneous disease with variable risk of recurrence, progression, and death. Low risk tumors (e.g., Ta and low grade) commonly recur, but are rarely lethal in the absence of progression.1 In contrast, more aggressive cancers (e.g., T1, high grade) frequently progress to muscle-invasive disease,1 mortality from which is high. Clinical data suggest that traditional methods of surveillance and treatment do not improve survival.2 In fact, patients who progress under a watchful eye may fare worse than those who initially present with invasive cancers.3

Although clinical guidelines provide a framework for managing patients with varying levels of disease risk,4 the evidence base underlying treatment recommendations is imperfect. In light of the uncertainty surrounding how best to care for those with early stage bladder cancer, urologists vary widely in how aggressively they manage their patients.5 Perhaps more importantly, intensive management of these patients, implicit in current guidelines, has not necessarily improved imperative outcomes, such as survival. For example, while intensive use of intravesical therapy can prolong the interval between disease recurrences, the extent to which it improves survival or prevents progression is uncertain.6, 7 In contrast, other recommended practices, such as frequent cystoscopy,8 have theoretical advantages but lack empirical support demonstrating a benefit.

Recognizing that the optimal approach for caring for patients with early stage bladder cancer is unknown, we explored secular trends in its management and identified relationships between clinical characteristics and initial treatment intensity. Finally, we evaluated the extent to which treatment intensity paralleled the risk posed by bladder cancer.

Methods

Study Population

Using Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) - Medicare data, we identified patients diagnosed with bladder cancer for the years 1993 through 2002. Using Medicare claims, patients were followed through December 31, 2005. As detailed elsewhere,9 SEER-Medicare data provide a rich source of information on Medicare patients included in SEER, a nationally representative collection of population-based cancer registries. During the study period, the SEER registries coverage increased from about 14% of the U.S. population (1993 to 1999) to approximately 26% of the U.S. population (2000 to 2002).10 The linked data contain 100% of the Medicare claims from the inpatient, outpatient, and national claims history files. This study was limited to patients with early stage bladder cancer (modified American Joint Commission on Cancer 3rd edition, stage 0 and 1),11 and to those fee-for-service beneficiaries with continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A and B commencing with the year prior to diagnosis. Patients who underwent cystectomy within 6 months of diagnosis were excluded from this analysis as they may have harbored more aggressive disease that was downstaged (e.g., clinical T2 to pathologic T1) on pathologic analysis of the bladder.

Using this approach, our final cohort consisted of 24,980 patients.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was patient-level treatment intensity, as measured by all Medicare payments for bladder cancer incurred within the first two years after diagnosis. Using inpatient and outpatient claims, we included those expenditures associated with a primary diagnosis code for bladder cancer [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, (ICD-9) diagnosis codes: 188.x-bladder cancer, 233.7-carcinoma in situ of the bladder, and V10.51-personal history of bladder cancer]. Medicare payments were standardized to 2005 dollars using the Medicare Economic Index,12 and were price-adjusted to account for regional variation in Medicare reimbursement. Through these adjustments, expenditure data reflects the intensity at which services were provided to patients, and could be compared across years and regions. To illustrate relationships between clinical characteristics and the treatment intensity received, we sorted patients into three equally sized groups of low, medium, and high initial treatment intensity.

To understand the care underlying differences in intensity, we characterized health care services commonly used in early stage bladder cancer patients. Using ICD-9 procedure and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes within the Medicare files, we identified surveillance-related services (endoscopic examination of the bladder, upper urinary tract evaluation, urinary tests, radiographic imaging studies, and office visits to the physician primarily responsible for each patient’s bladder cancer care) and treatment-related services (intravesical therapy and restaging transurethral resection). Finally, payments for bladder cancer services were then tallied by type (provider, hospital, or institutional outpatient) to understand where changes in spending were occurring over time.

Characterizing Bladder Cancer Risk

Because of the chronic nature of early stage bladder cancer in many patients, competing causes for mortality are particularly important when considering the risk posed by the cancer.13 Although ill-defined,14, 15 most would agree that there are combinations of age, comorbidity and disease severity that confer varying levels of risk of bladder cancer death among those with early stage disease. For example, a 85 year old with multiple comorbid illnesses diagnosed with a low grade Ta cancer has a lower risk of cancer-related death than a healthy 65 year old diagnosed with a high grade T1 cancer. Because our intent was to assess how treatment intensity parallels bladder cancer risk, we identified groups of patients with very low and very high risk of bladder cancer-related death. Our group with the lowest risk of bladder cancer death included patients at least 85 years of age with two or more comorbid illnesses and low grade Ta bladder cancer. Our group with the highest risk included patients less than 75 years of age with no more than one comorbid illness, and carcinoma in situ or T1 bladder cancer. Our intent was not to identify all high and low risk patients; rather, we wanted to explore treatment intensity at the margins of bladder cancer risk.

Statistical Analysis

We measured temporal changes in the initial treatment intensity and use of bladder cancer services on a yearly basis. Due to the addition of four new SEER registries in 2000, we stratified the data by time period (SEER 13, years 1993 to 1999 and SEER 17, years 2000 to 2002). Statistical inference was made using linear regression or chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical data, respectively. We further assessed temporal trends in treatment intensity by evaluating changes in the types of Medicare payments (hospital, institutional outpatient, and physician) over time using linear regression, again stratified by time period.

We then measured relationships between treatment intensity (low, medium, high) and clinical characteristics, including age (5-year age groups), gender, race (white, black, or other), socioeconomic status, level of comorbidity, tumor grade (low, medium, high, or unknown), tumor stage (Ta, Tis, T1, early stage not otherwise specified)11 and SEER region. The early stage, not otherwise specified group (Ta, T1, NOS) was recorded by the SEER registrars as a separate category from the Ta or T1 tumors. We ascertained a patient’s socioeconomic status using a composite measure as described by Diez-Roux.16 Patient comorbidities were identified using all health care encounters in the 12-month period preceding the bladder cancer diagnosis using the well-established methods described by Klabunde and colleagues.17 We fitted a multiple logistic regression model to measure the independent relationship between patient characteristics and treatment intensity stratified by the year of SEER registry expansion. Finally, we characterized treatment intensity patterns among patients in our highest and lowest risk groups to better understand how intensity varies with risk.

All testing was conducted using SAS Version 9.1.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) using two-sided tests. The probability of Type 1 error was set at 0.05. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Michigan.

Results

Changes in treatment intensity occurred in the background of little variation in overall patient and tumor characteristics (Table 1). Over the first seven years of the study (SEER 13), the average patient age increased from 76.9 to 77.7 years (p < 0.01) and the percentage of white patients decreased from 94.5% to 92.2% (p < 0.01). While tumor stage remained fairly stable, the proportion of high-grade tumors increased from 26.2% to 31.6% (p < 0.01). Over the last three years of the study (SEER 17), patient age, tumor grade, and tumor stage all remained stable.

Table 1.

Secular changes in clinical characteristics of the bladder cancer population

| SEER 13 | SEER 17 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Diagnosis | p - value | Year of Diagnosis | p - value | |||||||||

| 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |||

| Patients | 1745 | 1807 | 1769 | 1853 | 1759 | 1907 | 1943 | 3954 | 4103 | 4140 | ||

| Age (mean) | < 0.01 | 0.27 | ||||||||||

| 77.0 | 76.9 | 77.1 | 77.6 | 77.4 | 77.7 | 77.7 | 77.9 | 77.9 | 78.1 | |||

| Age (%) | < 0.01 | 0.69 | ||||||||||

| 65–69 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 18.0 | 15.4 | 14.0 | 13.5 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 13.2 | 12.6 | ||

| 70–74 | 26.2 | 26.8 | 25.3 | 23.5 | 27.2 | 23.9 | 25.4 | 23.2 | 24.0 | 23.3 | ||

| 75–79 | 24.6 | 25.3 | 24.1 | 26.2 | 25.9 | 27.8 | 25.9 | 26.9 | 25.9 | 26.1 | ||

| 80–84 | 19.3 | 17.9 | 18.4 | 17.9 | 18.3 | 19.7 | 18.3 | 20.5 | 20.3 | 21.5 | ||

| 85+ | 13.1 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 17.0 | 14.6 | 15.1 | 16.6 | 15.8 | 16.6 | 16.5 | ||

| Female (%) | 0.81 | 0.08 | ||||||||||

| 25.9 | 26.1 | 27.7 | 26.3 | 25.4 | 26.0 | 25.8 | 26.5 | 24.7 | 24.6 | |||

| Race (%) | 0.10 | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| White | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.6 | 94.4 | 93.4 | 94.1 | 92.6 | 94.9 | 93.8 | 93.3 | ||

| Black | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.2 | ||

| Other | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | ||

| Socio-economic status (%) | 0.55 | 0.64 | ||||||||||

| Low | 30.7 | 32.2 | 30.5 | 31.3 | 30.9 | 31.0 | 29.4 | 35.2 | 35.1 | 34.8 | ||

| Medium | 34.8 | 33.4 | 36.7 | 33.9 | 33.1 | 33.8 | 34.6 | 31.8 | 33.1 | 33.0 | ||

| High | 34.5 | 34.4 | 32.8 | 34.8 | 36.0 | 35.2 | 36.0 | 33.0 | 31.8 | 32.2 | ||

| Comorbidity (%) | 0.14 | 0.91 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 70.0 | 69.3 | 69.2 | 69.0 | 67.4 | 66.7 | 65.3 | 62.3 | 62.0 | 62.2 | ||

| 1 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 19.6 | 21.4 | 20.8 | 22.7 | 23.0 | 23.5 | 22.6 | ||

| 2 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 9.0 | ||

| 3+ | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.2 | ||

| Tumor Stage | <0.01 | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| Ta | 54.1 | 54.4 | 56.3 | 58.2 | 59.0 | 57.8 | 53.1 | 53.8 | 52.0 | 54.6 | ||

| Tis | 7.6 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 6.6 | ||

| Ta, Tis, NOS | 11.6 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 9.1 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 13.5 | 14.6 | 13.8 | 13.4 | ||

| T1 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 25.3 | 24.2 | 24.4 | 24.0 | 25.5 | 25.0 | 26.6 | 25.4 | ||

| Tumor grade | <0.01 | 0.23 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 20.3 | 20.0 | 18.9 | 21.0 | 20.6 | 18.0 | 17.9 | 20.1 | 19.6 | 19.1 | ||

| 2 | 46.7 | 47.9 | 47.3 | 46.4 | 48.1 | 46.5 | 45.6 | 41.9 | 41.2 | 40.6 | ||

| 3 to 4 | 25.6 | 24.5 | 26.3 | 25.2 | 24.1 | 28.5 | 30.5 | 30.8 | 30.6 | 31.8 | ||

| Unknown | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 8.5 | ||

| SEER Region | 0.10 | 0.26 | ||||||||||

| Seattle (Puget Sound) | 11.8 | 9.5 | 11.4 | 11.7 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 6.4 | ||

| Atlanta | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.1 | ||

| Connecticut | 15.5 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 16.4 | 14.7 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 7.5 | ||

| Detroit | 17.8 | 17.8 | 18.8 | 17.0 | 19.4 | 17.3 | 17.8 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 8.3 | ||

| Hawaii | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | ||

| Iowa | 14.7 | 14.8 | 16.0 | 14.7 | 17.7 | 16.9 | 14.9 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 6.8 | ||

| New Mexico | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | ||

| Rural Georgia | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Utah | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.2 | ||

| California* | 26.4 | 26.7 | 24.6 | 25.8 | 24.9 | 25.0 | 23.5 | 30.5 | 29.1 | 29.6 | ||

| Kentucky | 7.4 | 7.5 | 8.1 | |||||||||

| Louisiana | 5.6 | 5.3 | 6.2 | |||||||||

| New Jersey | 19.3 | 20.4 | 19.6 | |||||||||

California includes the San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Jose/Monterey registries in the SEER 13 data. In the SEER 17 data, California also includes greater California.

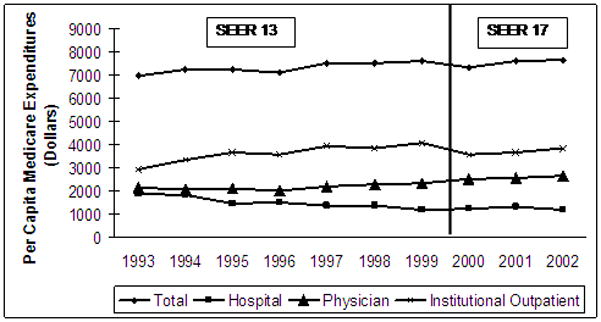

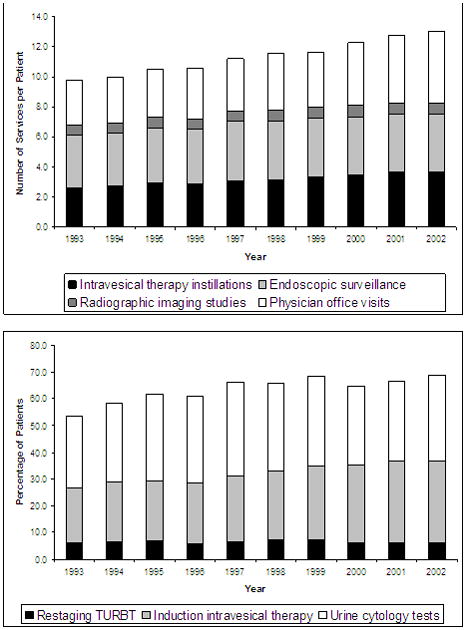

Despite these small changes in case mix, overall utilization increased significantly over the first seven years of the study. As illustrated in Figure 1, treatment expenditures for the first two years of bladder cancer care increased from $6,936 to $7,602 per capita (p < 0.01 for trend). This increase was primarily due to the greater use of institutional outpatient services ($2,915 to $4,053 per capita; p < 0.01 for trend). For patients diagnosed in the last three years of the study, overall expenditures for bladder cancer care appear to have stabilized, however per capita expenditures for care in the institutional outpatient setting continued to increase ($3,552 in 2000 to $3,824 in 2002; p = 0.04). Among physician services, endoscopic surveillance was the most common (Figure 2) although its use remained relatively steady across both the SEER 13 and SEER 17 cohorts. In contrast, intravesical therapy (2.6 versus 3.3 instillations per patient in the earliest versus latest group, respectively; p < 0.01 for trend) and physician visits (3.0 versus 3.7 visits per patient in the earliest versus the latest group, respectively, p < 0.01 for trend) increased substantially in the SEER 13 cohort. Within the SEER 17 cohort, only physician visits increased significantly (4.1 versus 4.8 visits per patient in the earliest versus latest group, respectively; p < 0.01 for trend).

Figure 1.

Per capita Medicare payments (standardized to 2005 dollars and price adjusted by region) for early stage bladder cancer therapy increased significantly in the SEER 13 cohort. Overall per capita utilization increased in the SEER 17 cohort, driven by increased institutional outpatient expenditures. Use of physician services also increased, but did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic surveillance was the most common service but remained relatively stable throughout the study. Use of intravesical therapy, and physician visits increased. Higher proportions of patients received induction intravesical therapy, but use of restaging TURBT and urinary cytology tests showed no significant linear trends over time.

Patient demographic, health, and tumor characteristics had strong associations with early stage bladder cancer treatment intensity in both the SEER 13 and SEER 17 cohorts (Table 2). Tumor grade and stage were strongly associated with greater intensity treatment. Compared to those with Ta tumors, patients with T1 cancers were nearly twice as likely to receive the most intensive care [odds ratio (OR), 1.92; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.70 to 2.97, SEER 13; and OR 1.61; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.95, SEER 17]. Similarly, patients with high-grade tumors were more than three times more likely to receive high intensity care (OR, 4.06; 95% CI, 3.47 to 4.74, SEER 13; OR, 3.08; 95% CI, 2.66 to 3.57, SEER 17). Conversely, older age and increasing comorbidity were associated with lower intensity care.

Table 2.

Relationship between patient factors and treatment intensity

| SEER 13 | SEER 17 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Intensity | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | Treatment Intensity | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Low | Med | High | High vs. Low | Low | Med | High | High vs. Low | |

| Number of Patients | 4257 | 4256 | 4270 | 4062 | 4061 | 4074 | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| 65–69 | 32.1 | 33.4 | 34.5 | 1.0 | 32.9 | 32.4 | 34.7 | 1.0 |

| 70–74 | 31.0 | 34.1 | 34.9 | 0.99 (0.85, 1.15) | 30.9 | 33.7 | 35.4 | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) |

| 75–79 | 31.3 | 33.6 | 35.1 | 0.97 (0.83, 1.20) | 31.3 | 33.8 | 34.9 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.26) |

| 80–84 | 33.9 | 33.8 | 32.3 | 0.81 (0.69, 0.94) | 34.3 | 32.5 | 33.2 | 0.88 (0.75, 1.04) |

| 85+ | 41.2 | 30.7 | 28.1 | 0.54 (0.46, 0.64) | 39.0 | 33.5 | 27.5 | 0.59 (0.50, 0.71) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 33.4 | 32.9 | 33.7 | 1.0 | 33.4 | 33.2 | 33.4 | 1.0 |

| Female | 33.1 | 34.4 | 32.5 | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) | 33.1 | 33.6 | 33.3 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 33.3 | 33.5 | 33.2 | 1.0 | 33.1 | 33.4 | 33.5 | 1.0 |

| Black | 30.0 | 27.5 | 42.5 | 1.21 (0.92, 1.59) | 36.9 | 27.3 | 35.8 | 0.90 (0.69, 1.18) |

| Other | 38.6 | 33.2 | 28.2 | 0.74 (0.54, 1.03) | 35.3 | 35.3 | 29.4 | 0.84 (0.63, 1.14) |

| Socio- economic status | ||||||||

| Low | 32.4 | 31.6 | 36.0 | 1.0 | 33.0 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 1.0 |

| Medium | 33.1 | 33.9 | 33.0 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 34.5 | 33.1 | 32.4 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) |

| High | 34.3 | 34.3 | 31.4 | 0.97 (0.85, 1.09) | 32.5 | 33.3 | 34.2 | 1.20 (1.06, 1.36) |

| Modified Charlson Index | ||||||||

| 0 | 32.7 | 33.3 | 34.0 | 1.0 | 31.9 | 33.5 | 34.6 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 33.2 | 33.7 | 33.1 | 0.96 (0.86, 1.08) | 32.9 | 33.8 | 33.3 | 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) |

| 2 | 35.4 | 32.8 | 31.8 | 0.89 (0.74, 1.06) | 37.4 | 33.8 | 28.8 | 0.72 (0.61, 0.86) |

| 3+ | 40.6 | 32.3 | 27.1 | 0.59 (0.47, 0.74) | 43.2 | 29.3 | 27.5 | 0.58 (0.47, 0.70) |

| Tumor Stage | ||||||||

| Ta | 37.9 | 34.3 | 27.8 | 1.0 | 36.8 | 34.0 | 28.2 | 1.0 |

| Tis | 28.4 | 32.7 | 38.9 | 1.49 (1.22, 1.80) | 28.0 | 31.0 | 41.0 | 1.86 (1.65, 2.10) |

| Ta, Tis, NOS | 33.3 | 35.2 | 31.5 | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | 38.0 | 33.2 | 28.8 | 1.00 (0.86, 1.15) |

| T1 | 23.5 | 30.7 | 45.8 | 1.92 (1.70, 2.17) | 24.5 | 30.8 | 44.7 | 1.61 (1.32, 1.95) |

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Low | 43.6 | 36.3 | 20.1 | 1.0 | 43.5 | 34.3 | 22.2 | 1.0 |

| Medium | 34.9 | 33.9 | 31.2 | 2.03 (1.78, 2.31) | 35.4 | 35.3 | 29.3 | 1.57 (1.37, 1.78) |

| High | 23.9 | 31.0 | 45.1 | 4.06 (3.47, 4.74) | 24.7 | 30.5 | 44.8 | 3.08 (2.66, 3.57) |

| Unknown | 29.4 | 29.7 | 40.9 | 3.20 (2.57, 3.99) | 30.9 | 31.6 | 37.5 | 2.20 (1.79, 2.70) |

| SEER Region | ||||||||

| Seattle (Puget Sound) | 41.6 | 34.2 | 24.2 | 1.0 | 35.1 | 34.1 | 30.8 | 1.0 |

| Atlanta | 28.4 | 34.1 | 37.5 | 2.65 (2.04, 3.44) | 34.3 | 32.3 | 33.4 | 1.22 (0.87, 1.73) |

| California** | 36.0 | 34.7 | 29.3 | 1.71 (1.43, 2.03) | 35.8 | 34.0 | 30.2 | 1.13 (0.92, 1.40) |

| Connecticut | 32.2 | 35.0 | 32.8 | 2.19 (1.82, 2.64) | 29.2 | 36.8 | 34.0 | 1.51 (1.17, 1.95) |

| Detroit | 29.8 | 30.4 | 39.8 | 3.13 (2.61, 3.75) | 24.8 | 28.5 | 46.7 | 2.73 (2.12, 3.50) |

| Hawaii | 38.9 | 27.2 | 33.9 | 2.01 (1.29, 3.13) | 25.2 | 31.9 | 42.9 | 2.41 (1.42, 4.10) |

| Iowa | 28.4 | 31.8 | 39.8 | 3.21 (2.66, 3.87) | 27.1 | 35.9 | 37.0 | 2.16 (1.67, 2.81) |

| New Mexico | 33.6 | 32.4 | 34.0 | 2.29 (1.72, 3.03) | 33.0 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 1.39 (0.93, 2.08) |

| Rural Georgia | 19.4 | 41.9 | 38.7 | 4.40 (1.46, 13.3) | 33.3 | 28.6 | 38.1 | 1.87 (0.65, 5.42) |

| Utah | 37.1 | 35.5 | 27.4 | 1.57 (1.20, 2.05) | 33.8 | 35.1 | 31.1 | 1.26 (0.89, 1.79) |

| Kentucky | 30.9 | 33.6 | 35.5 | 1.71 (1.32, 2.23) | ||||

| Louisiana | 30.6 | 35.2 | 34.2 | 1.78 (1.34, 2.36) | ||||

| New Jersey | 38.6 | 31.2 | 30.2 | 1.05 (0.85, 1.31) | ||||

Adjusted for age, race, gender, socioeconomic status, tumor stage, tumor grade, and SEER region.

California includes the San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Jose/Monterey registries in the SEER 13 data. In the SEER 17 data, California also includes greater California.

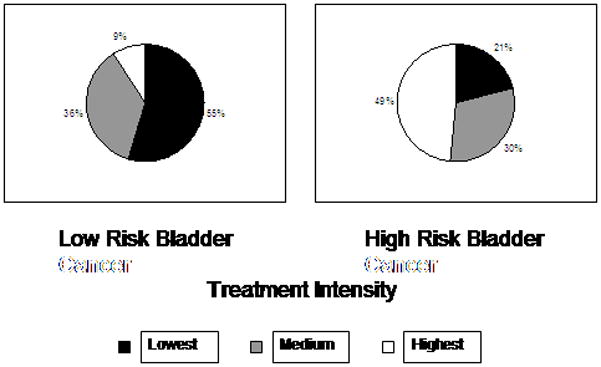

As illustrated in Figure 3, treatment intensity matched cancer severity for 55% and 49% of low- and high-risk patients, respectively. In other words, for many patients at the extremes of risk related to bladder cancer, treatment intensity did not parallel disease risk. Nine percent of patients with the lowest risk disease received high intensity care, and 21% of those with the most aggressive disease received low intensity care.

Figure 3.

The lowest risk of progression and recurrence category includes patients over 85 years of age with two or more comorbidities and Ta low grade disease. The highest risk category includes patients 65 to 74 years of age with no more than one comorbidity and T1 disease or CIS.

Discussion

While the proportion of patients diagnosed with Ta, T1, and Tis bladder cancer remained consistent over the ten-year study interval, locations of care for bladder cancer-related services shifted significantly, and overall per capita expenditures increased by over 10%. Growing Medicare payments for the initial management of early stage bladder cancer were largely due to increasing use of intravesical therapy and office visits, and a shift in care to the institutional outpatient setting. On average, treatment intensity appeared to be appropriately aligned with many clinical characteristics, including age, comorbidity, and cancer stage and grade. However, even as treatment intensity paralleled disease risk for many, up to one in five patients with the highest and lowest risk disease were managed discordantly with their cancer severity, suggesting opportunities for improvement.

The secular trend for increasing physician treatment intensity may be explained, to some degree, by the uncertainty surrounding contemporary practice guidelines.4, 18, 19 Although these guidelines offer recommendations in how to approach patients with early stage bladder cancer, they fall short of defining the optimal care, necessarily leaving decision-making in the hands of the physician. Because of the limited evidence base, consensus guideline recommendations lack stringency and generally favor more intensive care, despite the economic implications and the possibility that such care has little added value for the patient.20 Bladder cancer already ranks among the most expensive cancers to treat from diagnosis to death,21 in part due to its chronic nature and the growing population with early stage disease. As the U.S. population ages, the disease’s prevalence will invariably increase and related health-care costs are sure to rise. For this reason, eliminating potentially unnecessary care would likely yield a cost-savings to the already strapped Medicare program and mitigate the unintended consequences associated with overuse.

An additional limitation of early stage bladder cancer guidelines is that they restrict their guidance solely based on disease severity (i.e., cancer stage and grade), excluding several important patient factors. Bladder cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly with nearly three-quarters of cases occurring in patients aged 65 years and older.10 Unlike muscle-invasive cancer, which has high mortality rates,22, 23 early stage bladder cancer is generally a chronic disease, with a protracted, and often indolent, course.6 This natural history, coupled with high rates of competing-cause mortality24 in the elderly, suggests that a treatment approach tailored to disease and competing risks would improve the quality of care delivered to this population. Just as failure to aggressively treat a high-grade T1 cancer would represent poor quality, so too would the intensive treatment of a rarely lethal low-grade Ta tumor in an elderly patient. By ignoring competing risks in the elderly population, the guidelines’ “one-size-fits-all” approach promotes more health care, even when it is potentially unnecessary.

Our findings should be interpreted with a few limitations in mind. As with all observational studies,25 unmeasured factors can influence the outcome, in this case treatment intensity. To minimize confounding due to patient differences, we used clinical registry data allowing us to assess tumor stage and grade—arguably two of the most important determinants of treatment intensity.26 Further, we excluded patients undergoing radical cystectomy within 6 months after diagnosis to minimize misclassification associated with pathologic downstaging. Patient preference for therapy, which can potentially confound our findings, cannot be captured in administrative data. Thus, some may argue that overuse of health care among lower risk patients may reflect patient demand and expectations. However, patients are relatively uninformed consumers27 compared to their physicians and they generally rely on their doctor’s guidance. Thus, such preference could potentially be altered with better counseling on the front end. Since this study was set in the Medicare population, its applicability to patients younger than 65 may be limited. However, bladder cancer occurs mainly in the Medicare aged population10 so our findings are relevant to population at greatest risk for developing the disease. Finally, our need to stratify the data based on SEER expansion in 2000 resulted in a seven year study of SEER 13 data and a three year study of SEER 17 data. For examination of trends in expenditures and changes in demographics, the three year trends may be too short to reflect significant changes that are, in fact, occurring.

Conclusions

Despite little change in underlying disease severity, expenditures for early stage bladder cancer increased among Medicare patients between 1993 and 2004. Physician office visits and use of intravesical therapy were largely responsible for this increase. Although patient tumor stage and grade are typically used guide bladder cancer treatment, we observed a mismatch between disease severity and treatment intensity for many patients at the margins of early stage bladder risk. Defining the optimal surveillance and treatment strategies for early stage bladder cancer would be important for minimizing morbidity, improving quality, and increasing efficiency.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: Dr. Strope’s work was supported by National Institutes of Health (T32 DK007782-08). Dr. Hollenbeck’s work was supported by the American Cancer Society Pennsylvania Division—Dr. William and Rita Conrady Mentored Research Scholar Grant (MSRG-07-006-01-CPHPS); American Urological Association Foundation; Astellas Pharma US, Inc.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49(3):466–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. discussion 75–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CT, Dunn RL, Ingold C, Montie JE, Wood DP., Jr Early-stage bladder cancer surveillance does not improve survival if high-risk patients are permitted to progress to muscle invasion. Urology. 2007;69(6):1068–72. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrier BP, Hollander MP, van Rhijn BW, Kiemeney LA, Witjes JA. Prognosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: difference between primary and progressive tumours and implications for therapy. Eur Urol. 2004;45(3):292–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, Pruthi RS, Seigne JD, Skinner EC, et al. Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;178(6):2314–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollenbeck BK, Ye Z, Dunn RL, Montie JE, Birkmeyer JD. Treatment Intensity and Outcomes for Patients with Early Stage Bladder Cancer. JNCI. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp039. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, Montie JE, Gottesman JE, Lowe BA, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163(4):1124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP. A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2186–90. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125486.92260.b2. quiz 435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen LH, Genster HG. Prolonging follow-up intervals for non-invasive bladder tumors: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1995;172:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Medical Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [accessed 12-30-2008];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/data.html.

- 11.Greene F, Page E, Fleming I. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-104–17. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herr HW. Tumor progression and survival of patients with high grade, noninvasive papillary (TaG3) bladder tumors: 15-year outcome. J Urol. 2000;163(1):60–1. discussion 61–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alibhai SM, Leach M, Tomlinson GA, Krahn MD, Fleshner NE, Naglie G. Is there an optimal comorbidity index for prostate cancer? Cancer. 2008;112(5):1043–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litwin MS, Greenfield S, Elkin EP, Lubeck DP, Broering JM, Kaplan SH. Assessment of prognosis with the total illness burden index for prostate cancer: aiding clinicians in treatment choice. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1777–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease.[see comment] New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(2):99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–67. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, Kaasinen E, Bohle A, Palou-Redorta J. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder. Eur Urol. 2008;54(2):303–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scher H, Bahnson R, Cohen S, Eisenberger M, Herr H, Kozlowski J, et al. NCCN urothelial cancer practice guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998;12(7A):225–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond GA, Kaul S. The disconnect between practice guidelines and clinical practice--stressed out. Jama. 2008;300(15):1817–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Redaelli A, Laskin B, Hauser R. The health economics of bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the published literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21(18):1315–30. doi: 10.1007/BF03262330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng AC, Boyd S, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):666–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, Speights VO, Vogelzang NJ, Trump DL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(9):859–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. Jama. 2006;295(7):801–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmoor C, Caputo A, Schumacher M. Evidence from nonrandomized studies: a case study on the estimation of causal effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1120–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herr H, Konety B, Stein J, Sternberg CN, Wood DP., Jr Optimizing outcomes at every stage of bladder cancer: Do we practice it? Urol Oncol. 2009;27(1):72–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tu HT, Hargraves JL. Seeking health care information: most consumers still on the sidelines. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2003;(61):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]