Abstract

An insertional mutation made in the major cold shock gene cspB in Staphylococcus aureus strain COL, a methicillin-resistant clinical isolate, yielded a mutant that displayed a reduced capacity to respond to cold shock and many phenotypic characteristics of S. aureus small-colony variants: a growth defect at 37°C, a reduction in pigmentation, and altered levels of susceptibility to many antimicrobials. In particular, a cspB null mutant displayed increased resistance to aminoglycosides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and paraquat and increased susceptibility to daptomycin, teicoplanin, and methicillin. With the exception of the increased susceptibility to methicillin, which was due to a complete loss of the type I staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element, these properties were restored to wild-type levels by complementation when cspB was expressed in trans. Taken together, our results link a stress response protein (CspB) of S. aureus to important phenotypic properties that include resistance to certain antimicrobials.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major global public health problem causing serious, often life-threatening infections in the community and hospital settings that are becoming more difficult to manage with current antibiotic therapy regimens (7). The emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the hospital and community settings, coupled with the increasing number of persistent MRSA infections (25) and multidrug-resistant strains, is a growing problem not just for immunocompromised patients but also for otherwise healthy individuals. The virulence of S. aureus strains is multifactorial and involves the production of extracellular toxins, surface structures that mediate interaction with host cells and resistance to host defenses, transcriptional regulatory processes that control virulence gene expression, and metabolic schemes that allow for adaptation to stresses imposed by the local environment within and outside the human or animal host.

The capacity of S. aureus to respond to environmental stress conditions has been the subject of recent investigations (1, 33) and is imperative for its survival in hostile environments such as extreme temperature. S. aureus can effectively respond and adapt to a decrease in temperature by the expression of cold shock proteins (CSPs). This cold shock response likely plays a significant role in the ability of S. aureus to survive refrigeration and subsequently cause food-borne illnesses. Constitutive and inducible expression of CSPs is linked to a bacterial response to lower temperatures (16). CSPs have been extensively studied in both Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, and their roles in DNA and RNA binding have been investigated (15, 16). These proteins belong to several diverse classes, some of which are constitutively produced while others are induced upon cold stress (16). While the role of each of these proteins is unclear, the major CSP in E. coli acts as an RNA chaperone that prevents the formation of undesired secondary structures during cold shock and actively promotes transcription (4). In previous communications (20, 21), we reported that mutations within or upstream of the cold shock gene cspA decreased pigment production by S. aureus strain COL through a SigB-dependent mechanism and increased bacterial resistance to a cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAP) of human lysosomal cathepsin G. The decrease in the production of the carotenoid pigment staphyloxanthin by the cspA mutant was of interest, as it acts as an antioxidant, protecting staphylococci from neutrophil killing (24).

At the transcriptional level, cspB is the major cold shock gene in S. aureus (1) and its expression was impacted in S. aureus strain A22223I, a clinical osteomyelitis isolate, by a mutation in hemB, which is required for hemin biosynthesis (40). Mutations in hemB have been linked to the small-colony variant (SCV) phenotype often displayed by S. aureus strains isolated from sites of persistent or antibiotic-resistant infections (36). These naturally occurring SCV subpopulations have been isolated from patients with a wide variety of infections such as device-related infections, skin and soft tissue infections, osteomyelitis, and persistent airway infections in cystic fibrosis patients (19, 35, 44). SCVs frequently require exogenous hemin or menadione for growth, which has been implicated in their reduced membrane potential (26). Other hallmark features of SCVs include their reduced level of pigmentation, resistance to aminoglycosides, and reduced production of virulence factors (19, 35, 41, 44, 46). We created a nonpolar insertional mutation in the coding sequence of cspB and introduced this mutation into S. aureus COL. A cspB null mutant was found to exhibit many properties previously observed with SCVs, and most of these properties were reversed by complementation. The sole exception was that of susceptibility to methicillin, which was due to excision of the type I staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. aureus COL is a clinical MRSA isolate containing the type I SCCmec (13, 38); it is the parent strain of BD1 and BD2. Strain BD1 contains an aphA-3 insertion in cspB and was created by electroporation using pBD1 as previously described by Katzif et al. (20). Strain BD2 is a complemented version of BD1 and contains a wild-type copy of cspB expressed in trans from pBD2; the construction of pBD1 and pBD2 is described below. All S. aureus strains were grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA) or in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) (BD Pharmaceuticals, Wilson, NC) with or without antibiotic selection. E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source, reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| S. aureus strains | ||

| RN4220 | rsbU res mutant strain used for electroporation with E. coli-replicated plasmids | J. Iandolo, 23 |

| 8325-4 (Φ11) | 8325-4 harboring phage Φ11 | J. Iandolo, 32 |

| BD1 | Nonpolar aphA-3 Kmr cassette insertion into 5′ end of cspB coding region | This study |

| BD2 | Complement of strain BD1 using plasmid pBD1 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBT2 | Low-copy-number E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector with Ampr in E. coli and Cmr in S. aureus with temp-sensitive origin of replication | 5 |

| pBD1 | pBT2 construct containing 2.4-kb region with aphA-3 cassette inserted into 5′ end of cspB coding region | This study |

| pBD2 | pBT2 construct containing 1.4-kb region with wild-type cspB | This study |

| pUC19 | High-copy-number E. coli host; Ampr | 47 |

| pUC18K | pUC18 with aphA-3 nonpolar Kmr cassette; Ampr | 27 |

| pCR2.1 | High-copy-number PCR cloning vector; Ampr and Kmr in E. coli | Invitrogen |

Cold shock and gene expression analysis.

S. aureus strains were grown in 50 ml of TSB at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm), and growth was measured by determining the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). At mid-logarithmic phase, the culture was split into two 10-ml samples and these were incubated at 15°C (cold shock) or 37°C (control) for 1 h. Growth at both temperatures was monitored by OD measurement, and viability was determined by dilution plating onto TSA. In order to determine the expression of csp genes, RNA from control and cold-shocked cultures of strain COL was prepared as described by Katzif et al. (21). For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis, SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Inc.) was used with 500 ng of RNA from each sample according to the manufacturer's instructions for cDNA synthesis. AmpliTaq (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to generate transcriptional PCR products from the cDNA templates. The primers used to generate all transcriptional products are summarized in Table 2. The control transcripts in each were sigB, the transcript for an alternative sigma factor in S. aureus, and asp23, the transcript for the alkaline shock protein, which is a SigB-regulated transcript (14, 21). PCR products from all transcripts were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and imaged using the ChemiDoc XRS (Quantity One quantitation software; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and scanning densitometry was carried out.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this investigation

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| cspB3743S | CATTTTACTGTCCCGGGATTC | This study |

| cspB5723S | GAATCCCGGGACAGTAAAATG | This study |

| cspB5241 | GCGTAGTTACAACACCAATTATAG | This study |

| cspB31617 | CGTATGTAATTGAATCTGAGTAAAC | This study |

| sigB52673 | ATGGCGAAAGAGTCGAAATC | This study |

| sigB33421 | CTATTGATGTGCTGCTTCTT | This study |

| asp2351 | GAAAACTTCTGGTCCACGAG | This study |

| asp233512 | GCAGCGATACCAGCAATTTT | This study |

| rjmec | TATGATATGCTTCTCC | 11 |

| ORFX1r | AACGTTTAGGCCCATACACCA | 11 |

| ccrA5 | CGACAGAGCACTACAAAGCA | This study |

| ccrA3 | GCTGCTCGTGATTGAGTGTA | This study |

| mecA5F | CATATGACGTCTATCCATTT | This study |

| mecA5R | TCACTTGGTATATCTTCACC | This study |

| mecA5 | GTTGTAGTTGTCGGGTTTGG | This study |

| mecA3 | CCGTTCTCATATAGCTCATC | This study |

Isolation of chromosomal and plasmid DNAs.

Chromosomal and plasmid DNAs were both isolated as previously described by Katzif et al. (20). For isolation of chromosomal DNA, the DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used with the following modifications. Lysostaphin was used at a concentration of 50 μg/ml instead of lysozyme, a 1-h incubation at 37°C was used, 4 μl of RNase A (final concentration of 0.4 μg/ml) was added to each sample after lysis, and the sample was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Chromosomal DNA was eluted in 100 μl of AE buffer (Qiagen, Inc.), and the eluate was then applied to a spin column and eluted after a 5-min incubation. High-copy plasmids were isolated from 5-ml overnight cultures of E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen) using the Qiagen minipreparation technique. Low-copy-number plasmids propagated in E. coli were also isolated using the Qiagen minipreparation technique as described by Katzif et al. (21).

Plasmid construction and genetic exchange procedures.

Plasmid pBD1 was used to introduce a nonpolar insertion using the aphA-3 cassette encoding kanamycin resistance into the open reading frame of cspB. Plasmid pBD2 was constructed to reintroduce cspB on a low-copy-number vector in trans. Plasmids were constructed essentially as previously described (2, 5, 17, 20). To construct pBD1, a 1.4-kb region containing cspB was PCR amplified from genomic DNA from strain COL. Primers cspB5241 and cspB3743S were used to amplify a fragment containing cspB with a 3′ SmaI restriction site. All restriction enzymes were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Primers csp5723S and cspB31617 were used to amplify a 3′ region containing cspB with an internal SmaI site. The two fragments were ligated together, and the entire fragment was cloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen). This plasmid was transformed into E. coli, isolated, and digested with KpnI and XbaI. The fragment containing cspB was gel purified and ligated onto plasmid pUC19 digested with KpnI and XbaI. The aphA-3 cassette was released from plasmid pUC18K by SmaI and then ligated into the SmaI site of the cspB coding region on plasmid pUC19. The entire cspB fragment containing the kanamycin resistance cassette was isolated, purified, and then ligated onto a temperature-sensitive E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector, pBT2. The resulting plasmid, pBD1, was maintained in S. aureus strain RN4220 and moved into strain COL for allelic exchange. Following the method of Brückner for allelic exchange in S. aureus (5), strains containing plasmid pBD1 were grown on TSA at either 30°C for maintenance of the plasmid or at 42°C to select for the double crossover with the appropriate antibiotic. Liquid cultures of S. aureus were prepared using TSB and were grown at the appropriate temperature for either maintenance or loss of the plasmid. A similar procedure was used to create plasmid pBD2, which was used for complementation of strain BD1, but the aphA-3 cassette was not inserted into the SmaI site. Staphylococcal phage Φ11 was used for transduction of pBD2 into strain BD1 as previously outlined by Shafer and Iandolo (42). Phage Φ11 was induced using mitomycin C (1 μg/ml) and used to infect RN4220(pBD2) to obtain a transducing lysate. Transductants of strain pBD1 were selected on TSA plates containing 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. The presence of pBD2 in representative transductants was confirmed by digesting isolated plasmid DNA with KpnI and XbaI, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

PFGE and Southern hybridization.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as outlined by PulseNet, the National Molecular Subtyping Network for Foodborne Disease Surveillance of the CDC (Atlanta, GA) (43). Agarose plugs containing cells were prepared from 175 μl of overnight cultures of each strain grown in brain heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, MD) and digested with SmaI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Plugs were placed into the well of a 1% (wt/vol) SeaKem Gold (Cambrex Biosciences Rockland Inc., Rockland, ME) agarose gel and run with the following parameters: 200 V (6 V/cm), 14°C, 5-s initial switch, 40-s final switch for 21 h. The gel was stained using ethidium bromide, destained, and then visualized using UV light. For Southern hybridization, a 391-bp fragment of mecA was PCR amplified from S. aureus COL genomic DNA using primers mecA5F and mecA5R and used as a probe in Southern blot analysis. This mecA probe was prepared using the DIG DNA labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN) and following the manufacturer's instructions. The digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled mecA fragment was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blot analysis was performed as described by Satola et al. (39).

Antimicrobial susceptibility and pigment determinations.

To determine the susceptibility of S. aureus strains to aminoglycosides (amikacin and tobramycin), methicillin, and paraquat, a modified disc diffusion protocol from Chen and Morse (9) was used. Briefly, strains were grown in TSB overnight and then diluted 10-fold in TSB. Samples of 200 μl were then plated onto TSA and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Whatman filter paper discs (1.0 cm in diameter; Biometra, Goettingen, Germany) were soaked in a solution of the antimicrobial at various concentrations and then placed on the surface of the TSA plate, and incubation was continued at 37°C for 24 h. Zones of growth inhibition were determined by measuring the diameter of the growth inhibition. All disc diffusion assays were performed in triplicate. To determine the MIC values of daptomycin, gentamicin, teicoplanin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMS), Etest strips (bioMérieux, Inc., Durham, NC) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions, with the following changes. Cells were grown in TSB at 37°C for at least 20 h. For determination of MIC values after cold shock, cells were grown at 37°C until mid-log phase; the culture was then split into equal volumes, and half was allowed to continue to grow at 37°C or 15°C for 1 h. Etest strips for daptomycin, gentamicin, or TMS were then applied in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, with plates from each temperature being allowed to grow at 37°C or 15°C.

Pigment produced by S. aureus strains was visualized by inspection of colonies grown on TSA and was quantitated by the methanol extraction protocol previously described (29). Briefly, overnight cultures of each S. aureus strain were grown in 5 ml of TSB at 37°C for 24 h with the appropriate antibiotic. Cells were harvested from 850 μl of the culture after it was diluted to 108 CFU/ml, centrifuged, and washed once with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were resuspended in 200 μl methanol and heated at 55°C for 3 min. The supernatant was removed from the cell debris after spinning for 1 min at 13,000 rpm. The extraction was repeated once, the supernatants from each extraction were pooled into one tube, methanol was added to yield a final volume of 1 ml, and the absorbance at 465 nm was measured.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

cspB is the major cold-inducible gene in S. aureus strain COL.

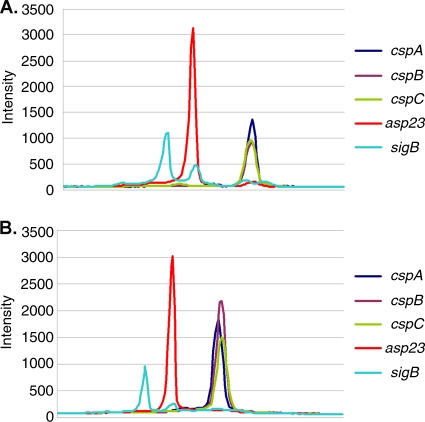

Previous work by Anderson et al. (1) indicated that cspB is the major cold-inducible gene in strain UAMS-1. Although CSPs have been implicated in maintaining the fidelity of bacterial gene expression during exposure to low temperature (4, 18), certain csp genes are expressed at 37°C and may have functions during normal growth. Earlier work by Katzif et al. (20) showed that production of CspA at 37°C can influence levels of staphylococcal susceptibility to CAPs and pigment production. Interestingly, a hemB mutant of S. aureus strain A22223I that displayed an SCV phenotype had altered levels of cspB expression compared to those of its hemB + parent (40). Accordingly, we sought to define the functions of CspB in this pathogen. As our previous studies (20, 21) on CAP resistance and pigment production in S. aureus were performed with strain COL, we first examined the levels of csp transcripts in this strain when a logarithmically growing culture was shifted from 37°C to 15°C. Using RNA extracted from control and cold-shocked cultures of strain COL and RT-PCRs to detect transcripts from the three main csp genes (cspA, cspB, and cspC) and two control genes (sigB and asp23) not differentially expressed during cold shock, we determined that cspB is the major cold shock gene expressed by S. aureus COL (Fig. 1). We found that the cspA transcript was more abundant than either the cspB or the cspC transcript in the culture maintained at 37°C, but the cspB transcript predominated in the 15°C culture; the ratios obtained when comparing the peak values at 15°C to 37°C were 1.34 for cspA, 2.79 for cspB, and 1.58 for cspC.

FIG. 1.

Densitometry analysis of selected S. aureus transcripts before and after cold stress. RNA was prepared as previously described, and a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Xl was used to measure the density of electrophoresed cDNA. Intensity is reported in proprietary units as a function of location on the gel. The peak intensity is reported for each transcript at 37°C (A) and after cold shock for 1 h at 15°C (B).

Loss of cspB in S. aureus COL leads to a severe growth defect and reduced pigmentation.

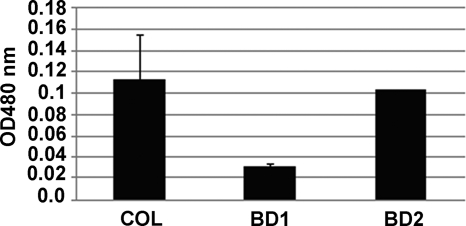

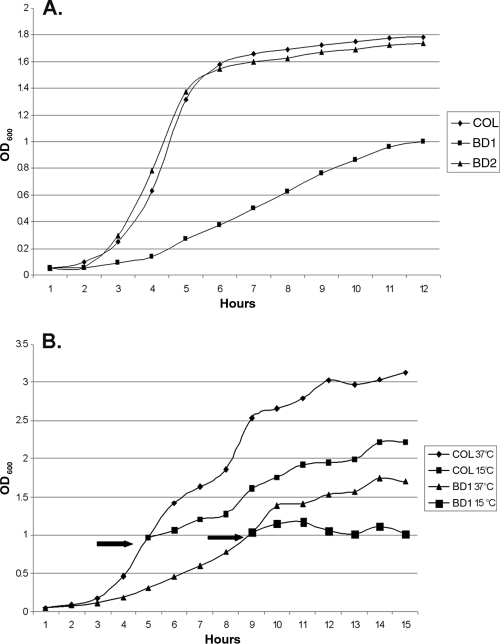

In order to study the function of cspB in S. aureus COL, we created a null mutant (strain BD1) that contained a nonpolar aphA-3 insertion in the cspB coding sequence. To verify that phenotypic differences (see below) were linked to this mutation, we also created a complemented strain (BD2) that had cspB expressed in trans from pBD2. Strain BD1 demonstrated many phenotypic differences compared to parent strain COL and complemented strain BD2. The most obvious differences were the smaller pinpoint colonies formed by BD1 that were less pigmented than the larger colonies from either parental strain COL or complemented strain BD2 (data not presented). The reduced level of pigmentation seen with colonies or cell pellets (data not presented) of BD1 compared to those of COL and BD2 was confirmed by measuring the level of methanol-extractable carotenoids (Fig. 2). When the growth of these strains in TSB at 37°C was monitored, we observed that the parent and complemented strains grew similarly but BD1 had a severe growth defect (Fig. 3A). Strain BD1 was also less proficient in responding to cold shock than was parent strain COL (Fig. 3B), a difference which was reversed by complementation (data not presented). The growth defect and reduced pigment properties of BD1 were stable, as spontaneous revertants could not be isolated (data not presented). We also found that additional cspB::aphA-3 mutants of COL expressed growth and pigment production phenotypes resembling those of BD1 (data not presented).

FIG. 2.

Pigment production by strains COL, BD1, and BD2. Levels of pigment in the test strains were quantified using a methanol extraction protocol adapted from Morikawa et al. (29), and the result for each strain is the average of three different samples done in triplicate. The differences in pigment production between COL and BD1 and between BD1 and BD2 were significant (P value = 0.001).

FIG. 3.

Growth differences observed between staphylococcal strains. (A) Growth experiments were carried out in TSB at 37°C. Growth was monitored each hour by reading the OD600 of cultures started at an identical OD of 0.05. (B) For cold shock experiments, the strains were initially both grown at 37°C until their respective mid-log phases. The cultures were then split (see arrow) into equal volumes and either grown at 37°C or shifted to 15°C. The growth of each culture was monitored hourly by measuring the OD600.

Although complementation with the wild-type cspB gene expressed from pBD1 was able to restore normal growth and levels of pigment production, we were concerned that second-site mutations in hemB and/or menD, which have been associated with the SCV property of S. aureus (45), might exist in BD1 and contribute to some of its SCV-like phenotypes. However, we found that the coding sequences of hemB and menD were identical in all three strains (data not presented). Since BD1 exhibited growth and pigment production properties resembling those of previously reported SCVs (26, 35, 46) yet had wild-type hemB and menD sequences, we concluded that multiple mechanisms contribute to the appearance of SCVs in S. aureus, including expression of cspB.

Loss of cspB impacts levels of antimicrobial resistance.

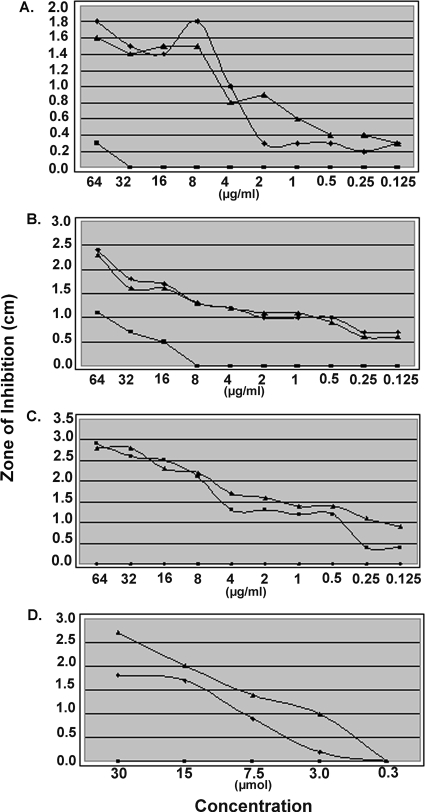

Since SCVs have been reported to display increased resistance to certain antimicrobials (19, 26, 35), notably, aminoglycosides, and BD1 exhibited SCV-like characteristics, we examined antimicrobial resistance levels of BD1 and compared them to those of parental strain COL and complemented strain BD2. BD1 was more resistant than COL or BD2 to a panel of aminoglycosides (gentamicin, amikacin, and tobramycin), TMS, and paraquat (Table 3 and Fig. 4). In contrast, BD1 was more sensitive than COL and BD2 to daptomycin, which is an anionic antimicrobial lipopeptide whose activity depends on the presence of calcium ions (6, 10, 12), and teicoplanin (Table 3). Interestingly, however, compared to COL, both BD1 and BD2 were very sensitive to methicillin, which we subsequently found to be due to loss of the type I SCCmec (see below).

TABLE 3.

MICs of antimicrobials used in this study

| Strain | MICa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daptomycin | Gentamicin | Teicoplanin | TMS | |

| COL | 1.5 | 0.38 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| BD1 | 0.064 | 32 | 0.75 | >32 |

| BD2 | 2.0 | 0.38 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

Values were determined by using Etest strips according to the manufacturer's instructions.

FIG. 4.

Disk diffusion analysis of selected antimicrobials. Disk diffusion assays were performed as previously described (9). Concentrations of amikacin (A), tobramycin (B), and methicillin (C) are given in μg/ml, while the concentration of paraquat (D) is given in μM. The zone of inhibition is defined as the diameter of the zone of clearance surrounding the impregnated filter disk as measured in centimeters. Zones of inhibition were measured after plates were incubated overnight at 37°C.

Since loss of cspB influenced the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of staphylococci, we tested if exposure of S. aureus COL to cold shock would change its level of susceptibility to antibiotics. For this purpose, a mid-logarithmic-phase culture was shifted from 37°C to 15°C and the MICs of daptomycin, gentamicin, and TMS were determined by Etest incubated at 15°C and 37°C for both the control (37°C) and cold-shocked cultures (15°C) (Table 4). For the control culture grown and maintained at 37°C, there was a nearly 4-fold increase in susceptibility to both daptomycin and TMS when the Etest assay was incubated at 15°C compared to that obtained when the Etest assay was incubated at 37°C (P = 0.0021 and 0.002, respectively). For the cold-shocked culture, there was an increase in susceptibility to daptomycin (2.4 fold, P = 0.0021) and TMS (1.8 fold, P = 0.013) when the Etest assay was incubated at 15°C. Additionally, the cold-shocked culture was more susceptible to TMS (3.2 fold, P = 0.006) when the Etest strip assay was incubated at 37°C. A similar decrease in daptomycin resistance after exposure to cold temperature was observed in strains BD1 and BD2 (data not presented). Hence, we propose that membrane changes independent of cspB likely account for the increased susceptibility of staphylococci to daptomycin when the bacteria are exposed to 15°C.

TABLE 4.

Influence of growth and assay temperature on antibiotic susceptibilities of S. aureus

| Growth temp (°C) and antibiotic | Avg MIC (μg/ml) at assay temp (°C) of: |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 37 | ||

| 37 | |||

| Daptomycin | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.0 | 0.0021 |

| Gentamicin | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.057 |

| TMS | 0.25 ± 0.0 | 1.33 ± 0.29b | 0.002 |

| 15 | |||

| Daptomycin | 0.63 ± 0.21 | 1.5 ± 0.0 | 0.0021 |

| Gentamicin | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.0 | 0.12 |

| TMS | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.07b | 0.013 |

P values shown are from a comparison of results of assays performed at 15°C versus 37°C.

MIC comparison of S. aureus strain COL grown at 37°C or 15°C and tested for susceptibility to TMS at 37°C, P = 0.006.

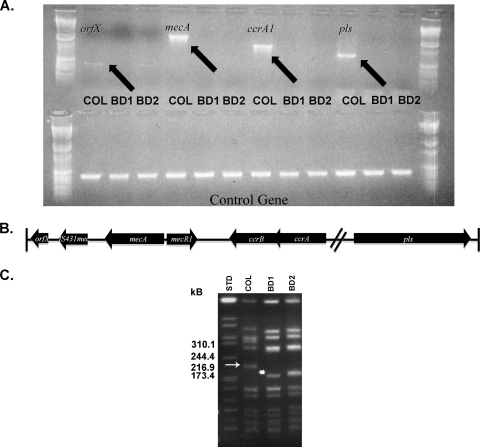

Loss of the type I SCCmec in BD1.

Recent work by Noto et al. documented spontaneous excision of mecA from clinical S. aureus strains in response to prolonged exposure to vancomycin (31). Our observation that strains BD1 and BD2 were, in contrast to MRSA parental strain COL, highly susceptible to methicillin led us to investigate the presence of the mecA gene and the full type I SCCmec in these strains. Using PCR primers to amplify the mecA gene, a product corresponding to the mecA gene (∼1.6 kb) was obtained from genomic DNA of parent strain COL but not BD1 or BD2, indicating that mecA was absent in the mutant and complement. To examine the extent of the deletion in this region, PCR was used to amplify several genes (e.g., orfX, mecA, ccrA, and pls) that spanned the entire SCCmec in COL (Fig. 5B). While these genes (orfX, mecA, ccrA, and pls) were readily amplified from COL chromosomal DNA, PCR products were not obtained when BD1 and BD2 DNA preparations were used as templates (Fig. 5A). To further examine the extent of this deletion, PFGE and Southern blot hybridization analyses were employed. The PFGE analysis demonstrated a unique SmaI pattern of strain COL versus strains BD1 and BD2 in that the latter strains lacked an approximately 200-kb fragment that was present in strain COL (arrow in Fig. 5C). As analysis of the COL genome sequence (cmr.jcvi.org) showed that the type I SCCmec is harbored on a 204-kb SmaI fragment, we hypothesized that this roughly 200-kb fragment in COL contained the mecA cassette. Indeed, Southern blot hybridization analysis on the gel shown in Fig. 5C that used a 391-bp mecA gene fragment probe showed that this was the case and that no bands in the SmaI digests of BD1 and BD2 hybridized to the probe. Considering these findings together with our PCR analysis (Fig. 5A), we conclude that the entire type I SCCmec was deleted in BD1 and BD2, indicating that these strains have at least a 30-kb deletion compared to parental strain COL. As BD1 and BD2 have a unique band corresponding to approximately 170 kb (asterisk in Fig. 5C); we tentatively conclude that it was generated due to deletion of the complete type I SCCmec.

FIG. 5.

Loss of type I SCCmec genes in strains BD1 and BD2. Selected genes associated with the type I SCCmec were amplified using PCR. As a control, 16S rRNA was amplified in each reaction (A). The primers are listed in Table 2, and each strain used as a template is indicated above. (B) The genetic organization of selected genes on the type I SCCmec. The diagram illustrates the approximate size and orientation of select genes on the cassette and is not drawn to scale. (C) The PFGE SmaI restriction patterns of strains COL, BD1, and BD2 were compared from left to right, and the lane order is the SmaI fragments of the Salmonella serotype Branderup strain H9812 genome (STD), COL, BD1, and BD2. The sizes of SmaI fragments near the 200-kb fragment from COL are indicated. Southern blot analysis was used to confirm the deletion of the type I SCCmec. A DIG-labeled mecA PCR product was used to probe for the fragment containing the SCCmec in the staphylococcal genomes, and this probe hybridized only with the 200-kb SmaI fragment (arrow) from strain COL (data not shown; arrow). The asterisk next to the nearly 170-kb band shows the unique SmaI fragment in strains BD1 and BD2 that likely resulted from loss of the type I SCCmec.

We have confirmed that cspB is the major cold shock gene in S. aureus COL during growth at low temperature (Fig. 1). Not unexpectedly, a cspB null mutant (BD1) of this MRSA strain had a reduced capacity to grow at 15°C. Unexpectedly, however, it displayed several properties previously reported by others (26, 35, 46) for SCVs of clinical and laboratory strains of S. aureus. SCVs are phenotypically distinct subpopulations of S. aureus that have been implicated in persistent and drug-resistant infections (36). While it has been previously shown that mutations in certain genes (e.g., hemB and menD) involved in components of the electron transport chain (8, 22, 30, 40, 45, 46) can lead to the phenotypes seen in SCVs, the exact genetic mechanisms that allow S. aureus to accomplish this phenotypic shift remain unclear. Although BD1 shows many properties previously described in SCVs (e.g., a slow growth rate, decreased pigmentation, and resistance to aminoglycosides), there are important differences, notably, the absence of hemB or menD mutations in BD1. Given the many similarities between our cspB insertional mutant and SCVs, we propose that cspB could play a part in this phenotype shift. In this respect, Seggewiss et al. (40) noted that expression of cspB (SA2494) in S. aureus A22223I was upregulated in a model SCV hemB insertional mutant of this strain compared to its isogenic parent. Although our results seem at variance with those of Seggewiss et al. (40), it is important to note that our groups worked with different strains (COL versus A22223I). Moreover, our work was performed in a hemB+ background, while that of Seggewiss et al. was done with a hemB mutant, which might respond differently to cold shock at the transcriptional level. The altered antimicrobial susceptibility profile of BD1 compared to parental strain COL was of interest due to its increased resistance to aminoglycosides and paraquat and susceptibility to daptomycin and methicillin. While the aminoglycoside/paraquat resistance and daptomycin susceptibility properties of BD1 were reversed by complementation with the wild-type cspB gene expressed in trans, complementation failed to reestablish methicillin resistance. For reasons that remain unclear, BD1 (and other cspB null mutants of strain COL [data not presented]) had an apparent deletion of the type I SCCmec (Fig. 5). We do not yet know if CspB contributes to the maintenance of this cassette or if the deletion of the cassette was a secondary event that helps to reduce a fitness cost associated with loss of CspB production. It has been hypothesized (31) that SCCmec deletion reflects an attempt by staphylococci to gain a competitive advantage over those that still harbor an intact SCCmec.

Resistance to aminoglycosides in staphylococcal SCVs has been previously attributed to a diminished or inadequate membrane potential (34, 36). It is unknown if this is the reason for the resistance phenotype seen in BD1 (Table 3 and Fig. 4). However, the extreme resistance to paraquat (Table 3) seen in BD1 is suggestive of this mechanism. Paraquat is a redox cycling agent that exerts its toxicity by producing superoxide anions in the presence of oxygen, which can then form other reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals (3). In bacteria, it has been shown that protection against paraquat toxicity can be imparted by increasing the cellular levels of superoxide dismutase (28) and that the reduced form of paraquat can cross the bacterial membrane (37). These observations suggest that either (i) the positively charged reduced form of paraquat is unable to cross the bacterial membrane and exert its normal activity in the cytoplasm or (ii) the protection seen in BD1 is due to increased levels of superoxide dismutase. If paraquat is unable to cross the bacterial membrane due to improper membrane potential, this likely explains the increased resistance to aminoglycosides seen in BD1.

Although the role of the CSPs in S. aureus remains unclear, previous work on these proteins in E. coli suggests that they play roles as RNA chaperones (4, 18), as transcriptional antiterminators (4), and as an alternative initiation factor during translation. We are currently determining the mechanism(s) by which CspB functions in S. aureus under normal growth conditions and during cold shock so as to understand how it regulates the production of virulence factors and levels of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christal Hembree for help with the PFGE analyses, P. Johnson for help with figures, and Lane Pucko for help with manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI043316 and funds from a VA Merit Award from the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, both to W.M.S. W.M.S. is the recipient of a Senior Research Career Scientist Award from the Veterans Affairs Research Service. S.S. is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Emerging Infections Program.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, K. L., C. Roberts, T. Disz, V. Vonstein, K. Hwang, R. Overbeek, P. D. Olson, S. J. Projan, and P. M. Dunman. 2006. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J. Bacteriol. 188:6739-6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustin, J., and F. Gotz. 1990. Transformation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and other staphylococcal species with plasmid DNA by electroporation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 54:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Autor, A. P. 1974. Reduction of paraquat toxicity by superoxide dismutase. Life Sci. 14:1309-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae, W., B. Xia, M. Inouye, and K. Severinov. 2000. Escherichia coli CspA-family RNA chaperones are transcription antiterminators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:7784-7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brückner, R. 1997. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canepari, P., M. Boaretti, M. M. Lleo, and G. Satta. 1990. Lipoteichoic acid as a new target for activity of antibiotics: mode of action of daptomycin (LY146032). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1220-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers, H. F., and F. R. Deleo. 2009. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:629-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee, I., M. Herrmann, R. A. Proctor, G. Peters, and B. C. Kahl. 2007. Enhanced post-stationary-phase survival of a clinical thymidine-dependent small-colony variant of Staphylococcus aureus results from lack of a functional tricarboxylic acid cycle. J. Bacteriol. 189:2936-2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, C. Y., and S. A. Morse. 1999. Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterioferritin: structural heterogeneity, involvement in iron storage and protection against oxidative stress. Microbiology 145(Pt. 10):2967-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow, A. W., and N. Cheng. 1988. In vitro activities of daptomycin (LY146032) and paldimycin (U-70,138F) against anaerobic gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:788-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuny, C., and W. Witte. 2005. PCR for the identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains using a single primer pair specific for SCCmec elements and the neighbouring chromosome-borne orfX. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:834-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debbia, E., A. Pesce, and G. C. Schito. 1988. In vitro activity of LY146032 alone and in combination with other antibiotics against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:279-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyke, K. G., M. P. Jevons, and M. T. Parker. 1966. Penicillinase production and intrinsic resistance to penicillins in Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 1:835-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gertz, S., S. Engelmann, R. Schmid, K. Ohlsen, J. Hacker, and M. Hecker. 1999. Regulation of sigmaB-dependent transcription of sigB and asp23 in two different Staphylococcus aureus strains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:558-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graumann, P., and M. A. Marahiel. 1994. The major cold shock protein of Bacillus subtilis CspB binds with high affinity to the ATTGG- and CCAAT sequences in single stranded oligonucleotides. FEBS Lett. 338:157-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gualerzi, C. O., A. M. Giuliodori, and C. L. Pon. 2003. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of cold-shock genes. J. Mol. Biol. 331:527-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janzon, L., and S. Arvidson. 1990. The role of the delta-lysin gene (hld) in the regulation of virulence genes by the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 9:1391-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang, W., Y. Hou, and M. Inouye. 1997. CspA, the major cold-shock protein of Escherichia coli, is an RNA chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 272:196-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahl, B., M. Herrmann, A. S. Everding, H. G. Koch, K. Becker, E. Harms, R. A. Proctor, and G. Peters. 1998. Persistent infection with small colony variant strains of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzif, S., D. Danavall, S. Bowers, J. T. Balthazar, and W. M. Shafer. 2003. The major cold shock gene, cspA, is involved in the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to an antimicrobial peptide of human cathepsin G. Infect. Immun. 71:4304-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katzif, S., E. H. Lee, A. B. Law, Y. L. Tzeng, and W. M. Shafer. 2005. CspA regulates pigment production in Staphylococcus aureus through a SigB-dependent mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 187:8181-8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohler, C., C. von Eiff, G. Peters, R. A. Proctor, M. Hecker, and S. Engelmann. 2003. Physiological characterization of a heme-deficient mutant of Staphylococcus aureus by a proteomic approach. J. Bacteriol. 185:6928-6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, G. Y., A. Essex, J. T. Buchanan, V. Datta, H. M. Hoffman, J. F. Bastian, J. Fierer, and V. Nizet. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus golden pigment impairs neutrophil killing and promotes virulence through its antioxidant activity. J. Exp. Med. 202:209-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maslow, J. N., S. Brecher, J. Gunn, A. Durbin, M. A. Barlow, and R. D. Arbeit. 1995. Variation and persistence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains among individual patients over extended periods of time. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14:282-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNamara, P. J., and R. A. Proctor. 2000. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants, electron transport and persistent infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 14:117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ménard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moody, C. S., and H. M. Hassan. 1982. Mutagenicity of oxygen free radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:2855-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morikawa, K., A. Maruyama, Y. Inose, M. Higashide, H. Hayashi, and T. Ohta. 2001. Overexpression of sigma factor, σB, urges Staphylococcus aureus to thicken the cell wall and to resist beta-lactams. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 288:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norström, T., J. Lannergard, and D. Hughes. 2007. Genetic and phenotypic identification of fusidic acid-resistant mutants with the small-colony-variant phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4438-4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noto, M. J., P. M. Fox, and G. L. Archer. 2008. Spontaneous deletion of the methicillin resistance determinant, mecA, partially compensates for the fitness cost associated with high-level vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1221-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novick, R. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pané-Farré, J., B. Jonas, S. W. Hardwick, K. Gronau, R. J. Lewis, M. Hecker, and S. Engelmann. 2009. Role of RsbU in controlling SigB activity in Staphylococcus aureus following alkaline stress. J. Bacteriol. 191:2561-2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proctor, R. A., J. M. Balwit, and O. Vesga. 1994. Variant subpopulations of Staphylococcus aureus as cause of persistent and recurrent infections. Infect. Agents Dis. 3:302-312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proctor, R. A., and G. Peters. 1998. Small colony variants in staphylococcal infections: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:419-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proctor, R. A., P. van Langevelde, M. Kristjansson, J. N. Maslow, and R. D. Arbeit. 1995. Persistent and relapsing infections associated with small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabinowitch, H. D., G. M. Rosen, and I. Fridovich. 1987. Contrasting fates of the paraquat monocation radical in Escherichia coli B and in Dunaliella salina. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 257:352-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabath, L. D., S. J. Wallace, and D. A. Gerstein. 1972. Suppression of intrinsic resistance to methicillin and other penicillins in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2:350-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satola, S. W., J. T. Collins, R. Napier, and M. M. Farley. 2007. Capsule gene analysis of invasive Haemophilus influenzae: accuracy of serotyping and prevalence of IS1016 among nontypeable isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3230-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seggewiss, J., K. Becker, O. Kotte, M. Eisenacher, M. R. Yazdi, A. Fischer, P. McNamara, N. Al Laham, R. Proctor, G. Peters, M. Heinemann, and C. von Eiff. 2006. Reporter metabolite analysis of transcriptional profiles of a Staphylococcus aureus strain with normal phenotype and its isogenic hemB mutant displaying the small-colony-variant phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 188:7765-7777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seifert, H., H. Wisplinghoff, P. Schnabel, and C. von Eiff. 2003. Small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus and pacemaker-related infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1316-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafer, W. M., and J. J. Iandolo. 1979. Genetics of staphylococcal enterotoxin B in methicillin-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 25:902-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swaminathan, B., T. J. Barrett, S. B. Hunter, and R. V. Tauxe. 2001. PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:382-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Eiff, C., D. Bettin, R. A. Proctor, B. Rolauffs, N. Lindner, W. Winkelmann, and G. Peters. 1997. Recovery of small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus following gentamicin bead placement for osteomyelitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:1250-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Eiff, C., P. McNamara, K. Becker, D. Bates, X. H. Lei, M. Ziman, B. R. Bochner, G. Peters, and R. A. Proctor. 2006. Phenotype microarray profiling of Staphylococcus aureus menD and hemB mutants with the small-colony-variant phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 188:687-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Eiff, C., R. A. Proctor, and G. Peters. 2000. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants: formation and clinical impact. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 115:44-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]