Abstract

Bacterial entry is a multistep process triggering a complex network, yet the molecular complexity of this network remains largely unsolved. By employing a systems biology approach, we reveal a systemic bacterial-entry network initiated by Chlamydia pneumoniae, a widespread opportunistic pathogen. The network consists of nine functional modules (i.e., groups of proteins) associated with various cellular functions, including receptor systems, cell adhesion, transcription, and endocytosis. The peak levels of gene expression for these modules change rapidly during C. pneumoniae entry, with cell adhesion occurring at 5 min postinfection, receptor and actin activity at 25 min, and endocytosis at 2 h. A total of six membrane proteins (chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 7 [CXCR7], integrin beta 2 [ITGB2], platelet-derived growth factor beta polypeptide [PDGFB], vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 [VCAM1], and GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle [GEM]) play a key role during C. pneumoniae entry, but none alone is essential to prevent entry. The combination knockdown of three genes (coding for CXCR7, ITGB2, and PDGFB) significantly inhibits C. pneumoniae entry, but the entire network is resistant to the six-gene depletion, indicating a resilient network. Our results reveal a complex network for C. pneumoniae entry involving at least six key proteins.

Chlamydia pneumoniae, an obligate intracellular bacterium of the family Chlamydiaceae, is a highly prevalent pathogen implicated in severe human diseases such as respiratory tract infections, atherosclerosis, heart attacks (myocardial infarction), and asthma (10). These diseases, like other infectious diseases, are initiated by C. pneumoniae entry (10, 16, 17). Therefore, understanding the mechanism of C. pneumoniae entry is an important primary focus of C. pneumoniae studies.

Chlamydial entry is a multistep process, primarily including attachment, receptor binding, and endocytosis. The initial attachment of chlamydiae to cells is thought to occur through reversible electrostatic interactions with heparan sulfate-like glycosaminoglycans (10, 49). C. pneumoniae then binds to cellular receptors that trigger signal transduction, leading to endocytosis with cytoskeleton remodeling (10, 17). Several proteins have been proposed as cellular receptors critical for entry of the infectious elementary body (EB), such as epithelial membrane protein 2 (37), mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor (33), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (19), and the Tom complex (18). However, antibody blocking of these receptors individually only partly inhibits chlamydial infection (19, 33), leading to a recent suggestion that multiple receptors and pathways are involved in EB entry (13, 17).

Two families of proteins are involved in cytoskeleton remodeling during endocytosis: ADP-19 ribosylation factor 6 and Rho GTPases (4, 17). Both of these mediate different steps of actin reorganization during the internalization of chlamydiae. Downstream kinases following these two families of proteins include phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, MEK-ERK kinases and ERK 1/2, and the adaptor protein Shc (14). Two other families of proteins are also activated during endocytosis of C. pneumoniae entry: focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and dynamin, which bind to several proteins interacting directly or indirectly with F-actin and connect the endocytic machinery to the actin cytoskeleton (10, 13, 33). The above proteins and pathways for attachment, receptor engagement, and endocytosis interact in a complex network that spatially and temporally mediates chlamydial entry, which remains largely elusive.

It is difficult for traditional genetics and biochemistry to characterize a system of this complexity, but a systems biology network approach (e.g., analysis of system-wide protein-protein interaction networks) can greatly facilitate this discovery. Protein interactions can be extracted from published databases and can be combined to form genome-wide comprehensive networks (8, 9, 12). Systemic analysis of these networks can simultaneously elucidate possible pathway components and the cross talk among these components in response to C. pneumoniae infection.

In this study, we used a systems biology approach to systematically elucidate a comprehensive systemic network response to EB attachment/entry. Key components in this entry network were also identified by in silico analysis and experimental validation. Our work provides a conceptual framework for further understanding of the fundamental molecular basis of EB entry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. pneumoniae propagation.

C. pneumoniae strain A03 (a gift from James Summersgill) was previously isolated from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis (34). This clinical isolate was propagated in HEp-2 cells following standard laboratory protocols (30, 31, 34). Isolates were purified using 30% RenoCal centrifugation (27) to eliminate ∼0.1% contamination from human cell material.

HCAEC culture and infection.

In order to compare human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC) with other cell culture model systems for C. pneumoniae, we first performed an infectivity assay. The infectivity for HCAEC of C. pneumoniae was essentially equivalent to that for human peripheral blood monocytic leukemia (Thp1) cells, which are typically used to test protein-protein interactions (44). The infectivity was nearly half that for HEp-2 cells, which are routinely used to propagate the organism (27). Endothelial cell basal medium 2 with human epidermal growth factor (hEGF), hydrocortisone, GA-1000, fetal bovine serum (FBS), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), human fibroblast growth factor—basic with heparin (hFGF-B), revitropin insulin-like growth factor (R3-IGF-1) and ascorbic acid [EGM-2-MV Bullet kit; Clonetics, East Rutherford, NJ] was used to grow HCAEC (Clonetics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HCAEC cells were infected with C. pneumoniae at 0-min, 5-min, 25-min, and 2-h time points at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5.

RNA extraction, microarray hybridization, and array detection.

Cells were collected by centrifugation. RNA was purified using an RNeasy RNA purification kit (Qiagen Inc. Valencia, CA), including on-column treatment with DNase to eliminate all traces of DNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Affymetrix human genome U133 Plus 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were employed in this study. GeneChip one-cycle target labeling and control reagents (Affymetrix) were used for processing RNA and for hybridization to the microarrays following the manufacturer's protocols.

RNAi knockdown.

To avoid cell line bias, RNA interference (RNAi) experiments were also performed in HEp-2 cells in addition to HCAEC. Cells were cultured to 60% confluence, and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), including scrambled siRNA as a control, were transfected at a 75 nM final concentration, using 0.45% Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a 48-well format. After 36 h of siRNA-mediated gene knockdown, the medium was removed and the cells were infected with C. pneumoniae at an MOI of 0.5. After an additional 48 h of incubation, each experiment was analyzed for quantitative gene expression as described below. All experiments were performed in triplicate in each cell line, and the results are shown as averages and standard deviations.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy RNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA). DNA was digested with RQ DNase (Promega), and cDNA was generated using a reverse transcription kit (ABI). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out with a Power SYBR green PCR kit (ABI) following the manufacturer's instruction. The relative amount of target gene mRNA and 16S bacterial rRNA was normalized to host cell numbers using beta-actin mRNA.

Network assembly.

We assembled a protein-protein interaction network by combining the existing network databases and using systems network approaches as previously adopted (8, 12). Briefly, our network database included proteins and interactions from BIND (http://bond.unleashedinformatics.com/Action), DIP (http://dip.doe-mbi.ucla.edu/), HPRD (http://hprd.org/), PreBIND (http://www.blueprint.org/), the curated inflammatory disease database, and the EMBL human database (9, 35, 36, 46).

Network analysis.

The microarray data were analyzed using the Bioconductor in R project (22), the preliminary array quality assessment with the AFFYQCReport package, the background adjustment and normalization with the AFFY package, and the gene expression value estimation with the LIMMA package. Genes with P values of <0.05 and a fold change of >2 between infection and control were considered significantly altered by infection.

Genes with significant alterations in gene expression were used to overlap components in the protein interaction network as previously described (8, 12). These overlapped networks became the networks activated (up- and downregulated) during C. pneumoniae entry. The network was analyzed by using Network Analyzer (http://med.bioinf.mpi-inf.mpg.de/netanalyzer/index.php). The activated networks were decomposed into functional modules based on topological interconnection intensity and gene function (http://www.geneontology.org/) (3, 21, 28, 39, 40). Genes were classified according to the gene ontology database (http://www.geneontology.org/) (21).

RESULTS

A systemic network activated by C. pneumoniae entry.

To systematically decode the chlamydial entry network, we applied a protein-based network approach to analyze an expression profile altered by C. pneumoniae entry. Human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC), a model cell line for studying arthrosclerosis, were infected with C. pneumoniae, and a genome-wide gene expression profile of C. pneumoniae attachment and entry was measured at 5 min (corresponding to C. pneumoniae attachment), 25 min (attachment and early entry), and 2 h (entry) (see Materials and Methods). We assembled a protein interaction network by integrating the known protein interaction databases as previously described (8, 9, 12) (see Materials and Methods).

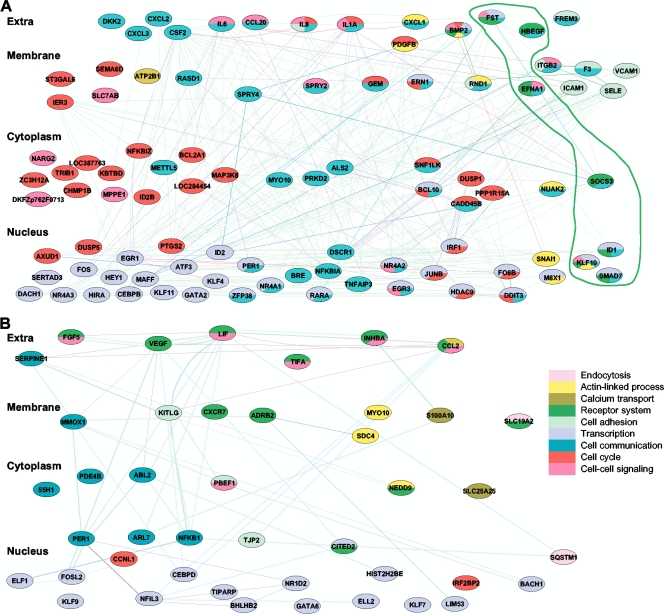

To integrate the gene expression profiles with the combined network database, genes with significantly altered expression during C. pneumoniae entry were mapped to their corresponding proteins in the network, and the overlaid network became a network activated by C. pneumoniae entry (Fig. 1). This activated network was decomposed into functional modules using network topology and gene ontology databases (see Materials and Methods). Due to gene pleiotropy, only the primary functions were used to cluster these genes into modules, and genes were grouped primarily by their first biological functions/processes (Fig. 1). A total of 9 modules were activated during C. pneumoniae entry, including cell adhesion, receptor systems, actin-linked process, cell communication, cell-cell signaling, cell cycle, calcium transport, transcription, and endocytosis (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Systemic network and modules involved in C. pneumoniae attachment/entry. Enhanced genes that were overlapped from C. pneumoniae attachment to entry (5 min, 25 min, and 2 h postinfection) were clustered into functional groups and combined into a network. This composition was treated as a C. pneumoniae entry network. Only the primary functions for each gene are indicated and colored in the index. Cellular components are shown on the left. (A) C. pneumoniae entry network, including the functional groups (highlighted). (B) Unique network activated at 2 h, in which genes are not overlapped with those upregulated at other time points.

Consistent with previous reports about C. pneumoniae entry pathways (13, 16, 17), the network includes almost all known pathways and their components upregulated by C. pneumoniae entry. Such pathways included heparin binding and receptor activity (heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor [HBEGF]) in the receptor group, cell-cell adhesion (intercellular adhesion molecule 1 [ICAM1] [CD54]) in the cell adhesion group, RAS dexamethasone-induced 1 GTPase activity (RASD1) in the cell-cell communication group, Rho family GTPase 1 GTPase activity (RND1) in the actin-linked group, transcription factors located in the nucleus, cytokines located in the extracellular space, and components for calcium movement in the calcium transport group. These data reveal a complex cellular network involved in C. pneumoniae entry, which comprises several functional subnetworks that are functionally dominated by receptor activity, signal transduction and communication, cell adhesion, and transcription.

Network modules dynamically activated for C. pneumoniae entry.

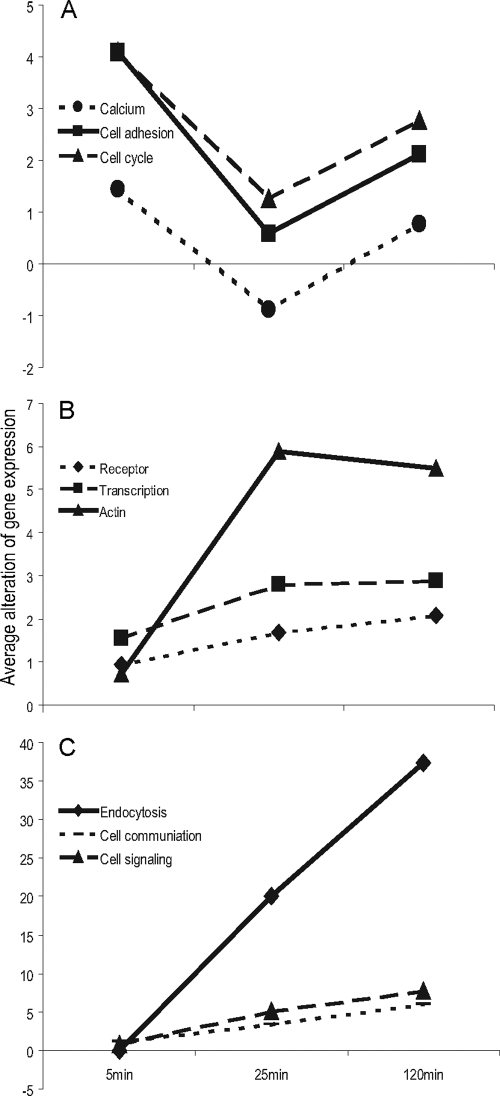

To examine how the network was dynamically activated to cope with C. pneumoniae entry, we calculated the sequential alteration of the mean of gene expression for each functional module against time (Dexpression/Dt) (Fig. 2). The modules of cell adhesion, calcium transport, and cell cycle were dramatically activated immediately after C. pneumoniae attached to cell surfaces (Fig. 2A). This was followed by receptor system, transcription, and actin-associated-process activation (Fig. 2B). Finally, endocytosis, cell communication, and cell signaling were activated (Fig. 2C). Throughout these processes, modules were distributed across the extracellular space to the nucleus (Fig. 1). This suggested that C. pneumoniae entry involves a delicate network in which functional modules ranging from cell adhesion to endocytosis coordinate precisely in time and space.

FIG. 2.

Functional modules dynamically activated during C. pneumoniae entry. Average gene expression for each functional module altered by time (Dexpression/Dt) was plotted against time, and results were clustered into three groups (A to C) on the basis of their patterns. (A) Attachment; (B) activation; (C) endocytosis.

Key proteins in the C. pneumoniae entry network.

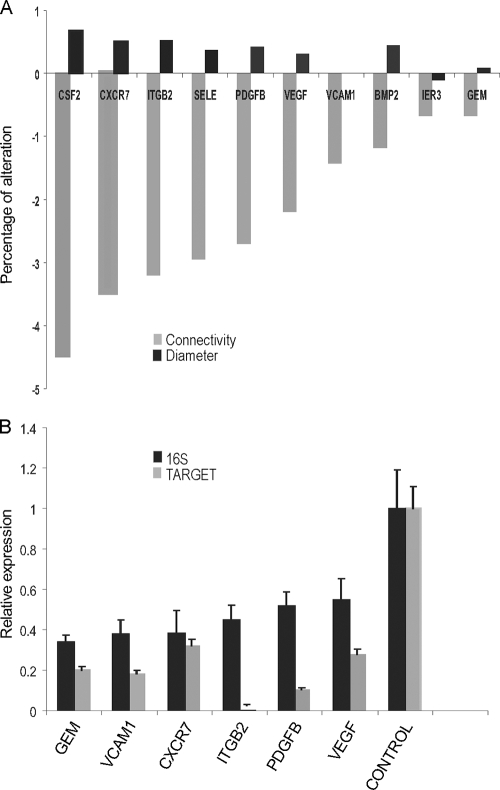

Network hubs are likely to play essential roles in the biological networks (5, 26, 41, 48). Hubs are nodes with high connectivity to other nodes and can be identified via examining their contributions to network interconnectivity and diameter. This is determined by comparing knockouts and calculating changes in the average number of neighbors, which indicates interconnectivity and changes in the mean shortest path that measures the smallest number of links between selected nodes and essentially indicates network diameter. Node knockouts in a network decrease network interconnectivity, and knockouts of nodes with higher connectivity lead to greater decreases in network interconnectivity. The length of the network diameter is inversely related to its interconnectivity. Knocking out a hub would increase the network diameter because of the loss of short paths in a network.

To probe the key components in the C. pneumoniae receptor network, we first identified in silico the network hubs by measuring the contribution of individual network components to the network through knocking out in silico individual nodes. Special attention was paid to the network components located in the extracellular space and membrane (Fig. 1) because they play crucial roles in initial steps of C. pneumoniae entry. The component colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2) contributed most to network connectivity and diameter (Fig. 1 and 3A), indicating that it serves as a potential hub in the C. pneumoniae entry network. Similarly, chemokine C-X-C motif receptor 7 (CXCR7) and integrin beta 2 (ITGB2) are other potential network hubs (Fig. 1 and 3A).

FIG. 3.

Key proteins identified for C. pneumoniae entry. Key proteins in the network were predicted in silico, and then RNAi was used for knockdown of the predicted proteins. (A) Key proteins (network hubs) were predicted by using the percentage of alterations in the diameter, and the connectivity of the network individual hub was knocked out. (B) A total of six predicted hubs were successfully knocked down by RNAi, which significantly reduced C. pneumoniae infectivity. Data are averages of at least replicates of each cell line, as for Fig. 4.

To confirm our in silico prediction, we performed experiments to measure the effect of these hubs on C. pneumoniae infection by using RNAi knockdown hubs. We focused on hubs functionally associated with cell adhesion, receptors, actin, and cell signaling because these categories of proteins are critical for bacterial entry and as potential C. pneumoniae receptors (13, 16, 17). These hubs included ITGB2, CXCR7, platelet-derived growth factor beta polypeptide (PDGFB), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), VEGF, and GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle (GEM) (Fig. 1 and 3B). RNAi employed in this study successfully knocked down gene expressions of the corresponding targets (>75% [Fig. 3B]). After gene knockdown, alterations of C. pneumoniae infectivity affected by hub knockdown were quantitated by real-time RT-PCR using 16S rRNA primers specific for C. pneumoniae (see Materials and Methods) in two cell lines, HCAEC and HEp-2, to minimize the cell line bias. Knocking down these 6 individual hubs significantly, but not completely, inhibited C. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 3B). The inhibition ranged from 67% to 45% compared with controls (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the potential hubs identified in silico are, in fact, important hubs in the C. pneumoniae entry network. The incomplete inhibition of C. pneumoniae entry by any single gene knockdown and the wide distribution of hubs throughout various functional modules, including cell adhesion (ITGB2 and VCAM1), receptor (VEGF and CXCR7), actin (PDGFB), and cell signaling (GEM), confirm that the C. pneumoniae entry network is very complex and includes multiple genes and modules.

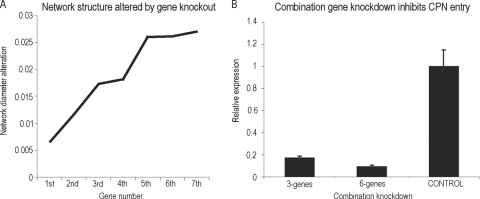

Robustness of network.

Knocking down a single gene only partially inhibited C. pneumoniae entry. We next investigated how many genes combined are sufficient to destroy the network and deplete C. pneumoniae infection. Thus, we examined the network robustness, or the resilience of the network. We first performed a sequential in silico combination gene knockout in the C. pneumoniae entry network and calculated the accumulating change in the network diameter after knocking out each node. A dramatic change of network diameter normally denotes a network disruption. Based on the contribution of each node to the network connectivity and diameter (Fig. 3A), we knocked out the selected genes in silico (Fig. 3B) in the following order: CXCR7, ITGB2, PDGFB, VEGF, VCAM1, and GEM. As expected, knocking out each node caused an increase in the accumulated network diameter, but the network diameter did not dramatically alter until 3-gene combination knockouts (CXCR7, ITGB2, and PDGFB) were performed. The entire network was set into a new state and was greatly disturbed (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the entire network was almost destroyed by simultaneously knocking out all 6 genes (Fig. 4A). To validate this, we performed experiments using RNAi to knock down these genes simultaneously and measured C. pneumoniae growth by testing bacterial 16S rRNA levels. The combined knockdown of the first 3 genes (CXCR7, ITGB2, and PDGFB) significantly inhibits C. pneumoniae infectivity (>80%), and the combined knockdown of 6 genes (CXCR7, ITGB2, PDGFB, VEGF, VCAM1, and GEM) dramatically reduces C. pneumoniae infection (>90%) (Fig. 4B). This suggested that the entire C. pneumoniae receptor network exhibits strong resilience, and it would not be dramatically destroyed until multiple genes (6 genes here) were simultaneously blocked.

FIG. 4.

Robustness of the C. pneumoniae entry network. (A) Gene combination knockout. The network diameter was dramatically changed after a 6-gene knockdown. (B) A combination of genes significantly reduced C. pneumoniae (CPN) infectivity. Knockdown of six genes almost entirely ablated C. pneumoniae infectivity, as measured by C. pneumoniae 16S rRNA expression using real-time qRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

Molecular complexity of C. pneumoniae entry.

The present study revealed the molecular complexity of C. pneumoniae entry using a systems biology network analysis of genome-wide gene expression profiles dynamically activated by C. pneumoniae entry. C. pneumoniae entry, which occurs within minutes of infection, alters the gene expressions of various pathway components, such as those involved in the immune response, calcium transport, and signal transduction (17, 33, 42, 45). These pathways, identified by traditional approaches, hypothetically interact to form a functional network in order to cope with C. pneumoniae stimulation. However, this network is too complex to be elucidated by traditional genetics, and it remains elusive. By taking advantage of the systems network approach, in which all known interactions and cross-talks among pathway components are included and interactions are treated as a complete network instead of linear circuits as in conventional approaches, we systematically elucidated a system network activated by C. pneumoniae entry (Fig. 1). The rich cross-talks between network components indicate that the network activated by C. pneumoniae entry is much more complex than previously thought.

Infectious agents can easily bind to cell surfaces via chemical interactions, but with low affinity. Microbe-specific receptors and coreceptors are required to strengthen these bindings, but they are not likely to be sufficient for a successful entry, which requires subtle contributions from other functional groups (modules). For instance, calcium transport and cytoskeletal movement are essential for surviving some receptor-ligand interactions and play crucial roles in strengthening microbe attachment to the cell surface (20). Similar roles exist for signal transduction, immune response, and chromatin remodeling (20). Therefore, a complex, coordinated network consisting of various network modules is required for microbe entry into cells (1, 23, 29, 32). Previous studies implied that C. pneumoniae entry requires an elaborate coordination of a series of modules, including receptors, receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, and trafficking (11, 17, 18, 33, 42-43, 45). Here, we revealed that a successful C. pneumoniae entry requires nine modules, including receptor modules, endocytosis, actin-linked processes, calcium transport, cell adhesion, transcription, cell communication, cell cycle, and cell-cell signaling (Fig. 1). Since these modules contain all pathway components known to date to be related to C. pneumoniae entry, this network probably represents a typical network mediating C. pneumoniae entry.

Functional modules are regarded as the basic functional unit in biology and as more accurate than individual genes in describing functional patterns. Individual genes could be switched on or off in a short time, and they might not directly cause any change in biological functions, which might not lead to a change in phenotype. In contrast, functional modules normally perform specific functions and associate with a specific phenotype. Therefore, the dynamic pattern of functional modules instead of individual genes could be more representative of the complex process of C. pneumoniae entry. A total of nine network modules identified in this study dynamically switched their functions (Fig. 2) within a very short time (2 h) after C. pneumoniae infection. The major modules activated at 5 min serve in cell adhesion, calcium transport, and cell cycle, which facilitate bacterial attachment. At 25 min, modules function in receptor mediation, transcription, and actin remodeling, suggesting that these modules couple with C. pneumoniae binding and penetration into the membrane. At 2 h, modules serve in endocytosis, cell communication, and cell signaling, suggesting that C. pneumoniae passes through the membrane 2 h postinfection and translocates the membrane via endocytosis. These data indicated that bacterial entry requires a rapid cellular adjustment at the module level and that C. pneumoniae can complete an entry process in a very short time, from attachment via adhesion proteins to interaction with receptors and finally to entry via endocytosis.

Network module identification could be affected by network sources, and some identified modules might not be related to the stated biological functions (7). However, since the modules identified here were based on confident databases, network topology features, and gene functions from gene ontology databases, our set of modules in this study likely represents a featured class of protein complexes in a natural biological network stimulated by C. pneumoniae entry.

Key cellular proteins for C. pneumoniae entry.

Many cellular proteins and their interaction partners are important for bacterial entry, but the central ones remain largely unknown. In Chlamydia, several individual proteins have been implicated in cell entry, such as mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor for C. pneumoniae (33) and a platelet-derived growth factor receptor for Chlamydia trachomatis (19). However, inactivating each of them only partially reduces chlamydial entry (19, 33), suggesting that multiple proteins are responsible for C. pneumoniae entry, although they have not been systematically identified. Here, we systematically identified six proteins crucial for C. pneumoniae entry. Knocking them down individually using RNAi significantly inhibited C. pneumoniae entry (67% to 45%) (Fig. 3), but similar to previous observations, these depleting approaches did not completely block C. pneumoniae entry. This is consistent with a long-standing notion in this field that there is no single receptor completely responsible for C. pneumoniae entry (13).

If no single protein is responsible for C. pneumoniae entry, multiple receptors should work together to account for C. pneumoniae entry, although there is a lack of studies to address this question. Here, we knocked out gene combinations in silico, leading to an alteration in the network structure (Fig. 4). Importantly, the network structure was strikingly destroyed when three or six genes were simultaneously knocked out. Experimental data also validated the in silico prediction that knocking down three or six key proteins dramatically inhibits C. pneumoniae entry (>80%) (Fig. 4), suggesting that C. pneumoniae entry requires multiple proteins and at least a triple combination of genes to dramatically block C. pneumoniae infection.

Among the genes identified above, most have been proven to mediate microbe entry into hosts. For example, CXCR7, ITGB2, and VCAM1 are important for virus entry; CXCR7 (RDC1) is a coreceptor for human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) (38); VCAM-1 is a receptor for encephalomyocarditis virus (24); ITGB2 encodes the integrin beta chain beta 2; and integrin serves as receptor and coreceptor for virus entry (2, 47). The involvement of chemokine receptor (CXCR7), adhesion molecule (VCAM-1), and integrin (ITGB2) during C. pneumoniae entry indicated that the C. pneumoniae entry system involves multiple proteins. Additionally, this system is similar to that of viruses, suggesting that microbes can share some fundamental mechanisms during their entry into host cells.

In this study, we used gene expression data and overlapped a protein interaction database to enrich a C. pneumoniae entry network. Gene expression data may not be completely consistent with protein level data, but genomics data measured by the Affymetrix microarray employed here was generally consistent with proteomics data (15). Our result for the C. pneumoniae entry network should represent a natural protein interaction network triggered by C. pneumoniae entry, which generally parallels the recent observations showing that a complex network is involved in pathogen entry (6, 25). The multiple proteins for C. pneumoniae entry revealed here are also similar to the recent discoveries in viruses in which multiple receptors and coreceptors are required for virus entry (6). We actually expect more proteins crucial for C. pneumoniae entry to be uncovered in the near future with new concepts and technologies. For example, proteins downregulated during C. pneumoniae entry might also be important for C. pneumoniae entry because C. pneumoniae might inhibit them or hijack their functions in order to facilitate the entry process. Therefore, the results presented here represent only a basic C. pneumoniae entry network. Our results suggest that targeting one or two receptor proteins, as we and other have done (19, 33), may not efficiently block C. pneumoniae entry and prevent the spread of C. pneumoniae across cells. The rapid change in dynamic modules makes it challenging to develop an efficient strategy to block C. pneumoniae entry, but the key proteins and entry network identified here and the approach we have developed should lay a framework to further dissect the molecular complexity of C. pneumoniae entry and facilitate novel and efficient drug development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jiaxin Li, Iongiong Ip, and Lawrence Kang for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported in part by the Pacific Vascular Foundation and the NIAID-sponsored program in Pathogen Functional Genomics Resource Center at TIGR (now JCVI) to D.D.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 March 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S., S. Uematsu, and O. Takeuchi. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthos, J., C. Cicala, E. Martinelli, K. Macleod, D. Van Ryk, D. Wei, Z. Xiao, T. D. Veenstra, T. P. Conrad, R. A. Lempicki, S. McLaughlin, M. Pascuccio, R. Gopaul, J. McNally, C. C. Cruz, N. Censoplano, E. Chung, K. N. Reitano, S. Kottilil, D. J. Goode, and A. S. Fauci. 2008. HIV-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin alpha4beta7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader, G. D., and C. W. Hogue. 2003. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics 4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balana, M. E., F. Niedergang, A. Subtil, A. Alcover, P. Chavrier, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 2005. ARF6 GTPase controls bacterial invasion by actin remodelling. J. Cell Sci. 118:2201-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barabasi, A. L., and Z. N. Oltvai. 2004. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5:101-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brass, A. L., D. M. Dykxhoorn, Y. Benita, N. Yan, A. Engelman, R. J. Xavier, J. Lieberman, and S. J. Elledge. 2008. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science 319:921-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brohee, S., and J. van Helden. 2006. Evaluation of clustering algorithms for protein-protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics 7:488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bromberg, K. D., A. Ma'ayan, S. R. Neves, and R. Iyengar. 2008. Design logic of a cannabinoid receptor signaling network that triggers neurite outgrowth. Science 320:903-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvano, S. E., W. Xiao, D. R. Richards, R. M. Felciano, H. V. Baker, R. J. Cho, R. O. Chen, B. H. Brownstein, J. P. Cobb, S. K. Tschoeke, C. Miller-Graziano, L. L. Moldawer, M. N. Mindrinos, R. W. Davis, R. G. Tompkins, and S. F. Lowry. 2005. A network-based analysis of systemic inflammation in humans. Nature 437:1032-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell, L. A., and C. C. Kuo. 2004. Chlamydia pneumoniae-an infectious risk factor for atherosclerosis? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carabeo, R. A., C. A. Dooley, S. S. Grieshaber, and T. Hackstadt. 2007. Rac interacts with Abi-1 and WAVE2 to promote an Arp2/3-dependent actin recruitment during chlamydial invasion. Cell Microbiol. 9:2278-2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuang, H. Y., E. Lee, Y. T. Liu, D. Lee, and T. Ideker. 2007. Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocchiaro, J. L., and R. H. Valdivia. 2009. New insights into Chlamydia intracellular survival mechanisms. Cell Microbiol. 11:1571-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coombes, B. K., and J. B. Mahony. 2002. Identification of MEK- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signalling as essential events during Chlamydia pneumoniae invasion of HEp2 cells. Cell Microbiol. 4:447-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox, J., and M. Mann. 2007. Is proteomics the new genomics? Cell 130:395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dautry-Varsat, A., M. E. Balana, and B. Wyplosz. 2004. Chlamydia-host cell interactions: recent advances on bacterial entry and intracellular development. Traffic 5:561-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dautry-Varsat, A., A. Subtil, and T. Hackstadt. 2005. Recent insights into the mechanisms of Chlamydia entry. Cell Microbiol. 7:1714-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derre, I., M. Pypaert, A. Dautry-Varsat, and H. Agaisse. 2007. RNAi screen in Drosophila cells reveals the involvement of the Tom complex in Chlamydia infection. PLoS Pathog. 3:1446-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elwell, C. A., A. Ceesay, J. H. Kim, D. Kalman, and J. N. Engel. 2008. RNA interference screen identifies Abl kinase and PDGFR signaling in Chlamydia trachomatis entry. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans, E. A., and D. A. Calderwood. 2007. Forces and bond dynamics in cell adhesion. Science 316:1148-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia, M., A. Jemal, E. M. Ward, M. M. Center, Y. Hao, R. L. Siegel, and M. J. Thun. 2007. Global cancer facts & figures 2007. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA.

- 22.Gentleman, R. C., V. J. Carey, D. M. Bates, B. Bolstad, M. Dettling, S. Dudoit, B. Ellis, L. Gautier, Y. Ge, J. Gentry, K. Hornik, T. Hothorn, W. Huber, S. Iacus, R. Irizarry, F. Leisch, C. Li, M. Maechler, A. J. Rossini, G. Sawitzki, C. Smith, G. Smyth, L. Tierney, J. Y. Yang, and J. Zhang. 2004. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5:R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greber, U. F., and M. Way. 2006. A superhighway to virus infection. Cell 124:741-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber, S. A. 1994. VCAM-1 is a receptor for encephalomyocarditis virus on murine vascular endothelial cells. J. Virol. 68:3453-3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuijl, C., N. D. L. Savage, M. Marsman, A. W. Tuin, L. Janssen, D. A. Egan, M. Ketema, R. van den Nieuwendijk, S. J. F. van den Eeden, A. Geluk, A. Poot, G. van der Marel, R. L. Beijersbergen, H. Overkleeft, T. H. M. Ottenhoff, and J. Neefjes. 2007. Intracellular bacterial growth is controlled by a kinase network around PKB/AKT1. Nature 450:725-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, D., J. Li, S. Ouyang, J. Wang, S. Wu, P. Wan, Y. Zhu, X. Xu, and F. He. 2006. Protein interaction networks of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster: large-scale organization and robustness. Proteomics. 6:456-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, D., A. Vaglenov, T. Kim, C. Wang, D. Gao, and B. Kaltenboeck. 2005. High-yield culture and purification of Chlamydiaceae bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 61:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maere, S., K. Heymans, and M. Kuiper. 2005. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 21:3448-3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh, M., and A. Helenius. 2006. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell 124:729-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molestina, R. E., D. Dean, R. D. Miller, J. A. Ramirez, and J. T. Summersgill. 1998. Characterization of a strain of Chlamydia pneumoniae isolated from a coronary atheroma by analysis of the omp1 gene and biological activity in human endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 66:1370-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukhopadhyay, S., A. P. Clark, E. D. Sullivan, R. D. Miller, and J. T. Summersgill. 2004. Detailed protocol for purification of Chlamydia pneumoniae elementary bodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3288-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pizarro-Cerda, J., and P. Cossart. 2006. Bacterial adhesion and entry into host cells. Cell 124:715-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puolakkainen, M., C. C. Kuo, and L. A. Campbell. 2005. Chlamydia pneumoniae uses the mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor for infection of endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73:4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramirez, J. A., and The Chlamydia pneumoniae/Atherosclerosis Study Group. 1996. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 125:979-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiss, D. J., I. Avila-Campillo, V. Thorsson, B. Schwikowski, and T. Galitski. 2005. Tools enabling the elucidation of molecular pathways active in human disease: application to hepatitis C virus infection. BMC Bioinformatics 6:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiss, K., T. Maretzky, A. Ludwig, T. Tousseyn, B. de Strooper, D. Hartmann, and P. Saftig. 2005. ADAM10 cleavage of N-cadherin and regulation of cell-cell adhesion and beta-catenin nuclear signalling. EMBO J. 24:742-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimazaki, K., M. Wadehra, A. Forbes, A. M. Chan, L. Goodglick, K. A. Kelly, J. Braun, and L. K. Gordon. 2007. Epithelial membrane protein 2 modulates infectivity of Chlamydia muridarum (MoPn). Microbes Infect. 9:1003-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimizu, N., Y. Soda, K. Kanbe, H. Y. Liu, R. Mukai, T. Kitamura, and H. Hoshino. 2000. A putative G protein-coupled receptor, RDC1, is a novel coreceptor for human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 74:619-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singhal, M., and K. Domico. 2007. CABIN: collective analysis of biological interaction networks. Comput. Biol. Chem. 31:222-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singhal, M., and H. Resat. 2007. A domain-based approach to predict protein-protein interactions. BMC Bioinformatics 8:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stelzl, U., U. Worm, M. Lalowski, C. Haenig, F. H. Brembeck, H. Goehler, M. Stroedicke, M. Zenkner, A. Schoenherr, S. Koeppen, J. Timm, S. Mintzlaff, C. Abraham, N. Bock, S. Kietzmann, A. Goedde, E. Toksoz, A. Droege, S. Krobitsch, B. Korn, W. Birchmeier, H. Lehrach, and E. E. Wanker. 2005. A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome. Cell 122:957-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subtil, A., B. Wyplosz, M. E. Balana, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 2004. Analysis of Chlamydia caviae entry sites and involvement of Cdc42 and Rac activity. J. Cell Sci. 117:3923-3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanson, K. A., D. D. Crane, and H. D. Caldwell. 2007. Chlamydia trachomatis species-specific induction of ezrin tyrosine phosphorylation functions in pathogen entry. Infect. Immun. 75:5669-5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuchiya, S., M. Yamabe, Y. Yamaguchi, Y. Kobayashi, T. Konno, and K. Tada. 1980. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1). Int. J. Cancer 26:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Virok, D. P., D. E. Nelson, W. M. Whitmire, D. D. Crane, M. M. Goheen, and H. D. Caldwell. 2005. Chlamydial infection induces pathobiotype-specific protein tyrosine phosphorylation in epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73:1939-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Mering, C., L. J. Jensen, B. Snel, S. D. Hooper, M. Krupp, M. Foglierini, N. Jouffre, M. A. Huynen, and P. Bork. 2005. STRING: known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:D433-D437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, X., D. Y. Huang, S.-M. Huong, and E.-S. Huang. 2005. Integrin αvβ3 is a coreceptor for human cytomegalovirus. Nat. Med. 11:515-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, H., P. M. Kim, E. Sprecher, V. Trifonov, and M. Gerstein. 2007. The importance of bottlenecks in protein networks: correlation with gene essentiality and expression dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3:e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, J. P., and R. S. Stephens. 1992. Mechanism of C. trachomatis attachment to eukaryotic host cells. Cell 69:861-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]