Abstract

β-Catenin-dependent canonical Wnt signaling plays an important role in bone metabolism by controlling differentiation of bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts. To investigate its function in osteocytes, the cell type constituting the majority of bone cells, we generated osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice (Ctnnb1loxP/loxP; Dmp1-Cre). Homozygous mutants were born at normal Mendelian frequency with no obvious morphological abnormalities or detectable differences in size or body weight, but bone mass accrual was strongly impaired due to early-onset, progressive bone loss in the appendicular and axial skeleton with mild growth retardation and premature lethality. Cancellous bone mass was almost completely absent, and cortical bone thickness was dramatically reduced. The low-bone-mass phenotype was associated with increased osteoclast number and activity, whereas osteoblast function and osteocyte density were normal. Cortical bone Wnt/β-catenin target gene expression was reduced, and of the known regulators of osteoclast differentiation, osteoprotegerin (OPG) expression was significantly downregulated in osteocyte bone fractions of mutant mice. Moreover, the OPG levels expressed by osteocytes were higher than or comparable to the levels expressed by osteoblasts during skeletal growth and at maturity, suggesting that the reduction in osteocytic OPG and the concomitant increase in osteocytic RANKL/OPG ratio contribute to the increased number of osteoclasts and resorption in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants. Together, these results reveal a crucial novel function for osteocyte β-catenin signaling in controlling bone homeostasis.

The adult skeleton is continuously remodeled in a tightly regulated manner by the coupled activity of bone-resorbing osteoclasts and bone-forming osteoblasts to maintain skeletal integrity and bone homeostasis (24, 46). A similar complex regulatory network of defined, but not necessarily coupled, osteoblast and osteoclast action is required during development and growth, when bone modeling ensures functional bone morphology and bone mass accrual, which in mice occurs throughout the first 3 to 4 months of life until peak bone mass is reached.

Osteoblasts differentiate from mesenchymal bone marrow progenitor cells into bone-forming osteoblasts that reside on the bone surface and deposit new bone matrix. In contrast, osteoclasts are derived from hematopoietic bone marrow precursor cells that belong to the myeloid monocyte/macrophage lineage (63). However, the majority, i.e., more than 90 to 95% of all bone cells in the adult skeleton, are osteocytes (10), terminally differentiated cells of the mesenchymal osteoblast lineage residing in small lacunae found at regular intervals within the mineralized bone matrix. They extend long thin cellular protrusions or dendrites, which travel through small channels (canaliculi) inside the compact bone, but also reach the bone surface and bone marrow compartment (8, 30). By forming gap junctions to neighboring cells, osteocytes are connected not only to each other but also to cells on the bone surface, including osteoblasts, bone lining cells, and possibly osteoclasts. They thus form a complex cellular network that seems ideally suited for mechanosensation and integration of local and systemic signals to ensure skeletal integrity and bone homeostasis (9, 10). Moreover, it was recently demonstrated that bone homeostasis and adaptation to regular or diminished skeletal loading are strongly disturbed in mice selectively depleted of osteocytes (61). Therefore, while osteocytes are cellular descendants of former bone matrix-producing osteoblasts, osteocytes have a unique cellular identity that is reflected by their specific location inside the bone matrix, their specialized cellular morphology adapted to being trapped in the mineralized bone compartment, and finally a specific molecular signature that clearly distinguishes osteoblasts and osteocytes from each other (52).

Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which is also known as canonical Wnt signaling, is a key signaling pathway required for normal bone and cartilage formation and for bone homeostasis (40, 55). Canonical Wnt signaling is initiated by secreted Wnt ligands binding to a dual-receptor complex formed by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 or 6 (Lrp5/6) and the seven-transmembrane domain receptor frizzled. This triggers a downstream signaling cascade leading to inhibition of cytoplasmic glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which in turn relieves β-catenin, the central mediator of canonical Wnt signaling, from its constitutive proteosomal degradation. β-Catenin then accumulates in the cytoplasm and translocates into the nucleus where it associates with members of the T-cell-specific transcription factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer binding factor (Lef) family to control Wnt/β-catenin target gene transcription. In contrast to canonical Wnt signaling, noncanonical Wnt signaling is β-catenin independent and can activate several downstream pathways, including the Wnt/planar cell polarity and the Wnt-cGMP/Ca2+ pathway (17, 55).

In bone, both canonical Wnt signaling and noncanonical Wnt signaling are involved in the control of osteoblastogenesis, although the role of noncanonical Wnt signaling is still less understood (17, 55). Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for commitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the osteoblast lineage and for osteoblastic precursor proliferation and differentiation (18, 19, 25-27). Conditional deletion of the β-catenin gene in osteoblasts in vivo using alpha 1 type I collagen Cre (Col1α1-Cre) (19) or osteocalcin-Cre (OC-Cre) (26) revealed an essential function for β-catenin-dependent Wnt signaling in controlling osteoclast differentiation and bone homeostasis, respectively. Osteoblast-specific β-catenin-deficient mice develop a low-bone-mass phenotype due to increased osteoclastic bone resorption as a result of decreased expression of the osteoclast differentiation inhibitor osteoprotegerin (OPG). Since in these mouse models, β-catenin function was deleted not only in osteoblasts but also in the cellular progeny of the mesenchymal osteoblast lineage, including osteocytes and bone lining cells, the relative contributions of these cell types to the observed bone resorption phenotype and the specific role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts versus their descendants remain to be addressed in detail. Previous studies have implicated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocyte mechanosensation, as Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated upon mechanical loading in osteocytes and is generally assumed to be a major signaling pathway required for mechanotransduction in bone in vivo (9, 11, 39, 56-58).

To determine the in vivo function of β-catenin in osteocytes, we generated osteocyte-specific β-catenin loss-of-function mice by crossing mice with a floxed β-catenin gene (13) with Dmp1-Cre transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase selectively in osteocytes (42). Here, we report that mice in which β-catenin has been conditionally knocked out in osteocytes (β-catenin cKO mice) develop an early-onset, severe low-bone-mass phenotype that is caused by elevated osteoclastic bone resorption mimicking the previously reported osteoblast-specific β-catenin loss-of-function phenotype (19, 26). Therefore, selective deletion of the β-catenin gene in the late-stage mesenchymal osteoblast lineage, i.e., in terminally differentiated osteocytes, is as detrimental to the skeleton as its earlier loss in the lineage, i.e., in osteoblasts, revealing an essential novel function for β-catenin signaling specifically in osteocytes that is required for normal bone homeostasis in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mice with the targeted β-catenin gene, in which exons two to six of the β-catenin gene are located within loxP sites (Ctnnb1loxP/loxP), were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (13). Dmp1-Cre transgenic mice expressing Cre under the control of a 14-kb regulatory fragment of the osteocyte marker gene Dmp1 have been previously described (42) and were maintained on a mixed CD1-C57BL/6 background. Heterozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice (Ctnnb1+/loxP; Dmp1-Cre) generated from crosses of both mouse lines were backcrossed with Ctnnb1loxP/loxP mice, and the progeny were analyzed. Data obtained from heterozygous and homozygous floxed β-catenin littermates lacking Dmp1-Cre were pooled and used as controls. In addition, 4-month-old C57BL/6JOlaHsd female mice from Charles River Laboratories, Germany, were obtained for isolation of adult femoral osteoblast- and osteocyte-enriched cell fractions. All mice were kept in cages under standard laboratory conditions with a constant temperature of 22°C and a cycle of 12 h of light and 12 h of dark. The mice were fed a standard rodent diet (catalog no. 3302; Provimi Kliba SA, Switzerland) with water ad libitum. Protocols, handling, and care of the mice conformed to the institutional policies and the Swiss federal law for animal protection under the control of the Basel-Stadt Cantonal Veterinary Office, Switzerland.

Radiography and microcomputed tomography (μCT) analyses.

Whole-body radiographs were taken after sacrifice of the animals in lateral and frontal positions (high-resolution MX-20 specimen radiography system; Faxitron, Buffalo Grove, IL). Generation of three-dimensional (3D) bone reconstruction images and evaluation of bone structure were accomplished by ex vivo measurements using a Scanco vivaCT40 (voxel size, 10.5 μm; high resolution; Scanco Medical). For cancellous and cortical bone analyses, fixed thresholds of 225 and 300, respectively, were used to determine the mineralized bone fraction. A Gaussian filter was applied (σ = 0.7; support = 1) to remove noise, and 30 slices were evaluated.

Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) analyses.

Cross-sectional total bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content (BMC), and cortical thickness were evaluated in five consecutive slices spaced 1.8 to 2 mm apart along the long bone axis of the left femur using an adapted Stratec-Norland XCT-2000 fitted with an Oxford (Oxford, United Kingdom) 50-μm X-ray tube (GTA6505M/LA) and a collimator with a 0.5-mm diameter. The following setup was chosen for the measurements: voxel size, 0.07 mm by 0.07 mm by 0.4 mm; scan speed scout view, 10 mm/s; final scan, 5 mm/s, 1 block, contour mode 1, peel mode 2; and cortical and inner threshold, 350 mg/cm3.

Bone histomorphometry.

All mice received fluorochrome markers by subcutaneous injection 10 days (alizarin complexone [Merck]; 20 mg/kg of body weight) and 3 days prior to necropsy (calcein [Fluka]; 30 mg/kg) to evaluate bone formation dynamics. The left femur was fixed for 24 h in 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, defattened at 4°C, and embedded in methylmethacrylate resin. For each animal, a set of 5-μm nonconsecutive longitudinal sections was cut in the frontal midbody plane (Leica RM2155 microtome; Leica Microsystems). Fluorochrome marker-based dynamic bone parameters were determined using a Leica DM microscope fitted with a Sony DXC-950P camera and adapted Quantimet 600 software (Leica). Microscopic images of the specimen were digitized and evaluated semiautomatically (×200 magnification) as previously described (33). The bone surface, single- and double-labeled bone surface, and interlabel width were measured in the cancellous bone compartment and at the endocortex of the distal femur metaphysis. Mineralizing surface was calculated as follows: MS/BS = [(dLS + sLS/2)/BS] × 100, where MS is the mineralizing surface, BS is the bone surface, and dLS and sLS are the double-labeled and single-labeled bone surface, respectively. The mineral apposition rate (MAR) (μm/day) in the cancellous bone compartment corrected for section obliquity was calculated, and the daily bone formation rate (BFR/BS, where BFR is the bone formation rate) (μm/day) was derived. Osteoblast and osteoid surface per bone surface and the number of osteocytes per cortical bone area were determined on Goldner-stained sections. Osteoclast number was determined on 5-μm femoral microtome sections stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity. Bone histomorphometric nomenclature was applied as recommended by Parfitt et al. (53).

General histopathology and whole-mount skeletal staining.

Tissue and organ samples (lungs, heart, liver, gallbladder, kidneys, urinary bladder, ovaries, uterus, vagina, brain, thymus, spleen, pancreas, tongue, stomach, small and large intestine, mesenteric and mandibular lymph nodes, trachea, esophagus, aorta, skin, mammary gland area, skeletal muscle, peripheral nerve, adrenal glands, pituitary gland, thyroid with parathyroid glands, eyes, Harderian glands, lacrimal glands, sternum, and humerus with elbow joint) from homozygous and heterozygous mutant and control mice were fixed in neutral phosphate-buffered formalin, and the bones were demineralized with formic acid. All fixed organs/tissues were trimmed, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to determine histopathological phenotypic abnormalities. Whole-body skeletal staining of cartilage and bone with alcian blue and alizarin red S was performed as previously described (28).

TUNEL and immunofluorescence staining.

The femora of mutant and control pups (three per group) were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, decalcified for 3 days (15% EDTA-0.5% paraformaldehyde), cryoprotected, and embedded in Tissue-Tek optimum-cutting-temperature (O.C.T.) compound (Sakura Finetek). Five-micrometer cryostat sections obtained with the CryoJane tape-transfer system (Instrumedics) were processed for detection of apoptotic osteocytes based on terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) technology using the in situ cell death detection kit with fluorescein (Roche Applied Science), followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with goat anti-sclerostin (R&D Systems) primary antibody in 10% normal donkey serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies according to standard procedures. Images were collected on a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope.

Clinical blood biochemistry, serum bone biomarkers, and RANKL determination.

Blood samples for clinical biochemistry, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) assessment and for determination of C-telopeptide fragments of collagen type I (CTX-I) and TRAP activity were collected under CO2 narcosis by heart puncture. Clinical biochemistry parameters, including serum ALP levels, were determined with a Synchron CX5 analyzer or a COBAS MIRA S system using standard test kits (Roche Diagnostics; Axon Lab). Serum osteocalcin concentration was quantified using an immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) kit (Immutopics). Free RANKL levels, i.e., the levels of RANKL not bound to osteoprotegerin (OPG), were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions with the detection minimum being below 5 pg/ml. Serum CTX-I concentration and TRAP activity were determined by ELISA (Immunodiagnostic Systems).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) expression analyses.

Total RNA from mutant and control mice was isolated from cortical bone of femoral diaphyses as previously described (32). Osteoblast and osteocyte selective total RNA was isolated by sequential enzymatic digestion of adult wild-type femora using a modified version of the protocol of Gu et al. (21). Briefly, the soft tissue and periosteum were removed, epiphyses were cut off, and bone marrow was flushed with PBS. The diaphyses were incubated at 37°C for 20 min with shaking in 0.2% collagenase type IV (Sigma) in isolation buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 70 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 60 mM sorbitol, 30 mM KCl, 3 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.5% glucose followed by rinsing with PBS. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 800 × g for 8 min, and cell pellets were resuspended in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and frozen at −80°C (fraction 1). The remaining diaphyses were digested in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.1% BSA at 37°C for 20 min and rinsed once with PBS, and supernatants were collected and stored as described above (fraction 2). The diaphyses were then incubated twice in 0.2% collagenase solution at 37°C for 30 min for femora from 6-week-old mice or for 60 min for femora from 4-month-old mice and rinsed with PBS, and the supernatants were collected and stored as before to yield fractions 3 and 4. Fraction 5 was obtained following digestion of the diaphyses in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.1% BSA at 37°C for another 30 min for femora from 6-week-old or for 45 min for femora from 4-month-old mice. The cells were collected as described above. The remaining femoral diaphyses were transferred into TRIzol together with 5-mm stainless steel beads (Qiagen), homogenized using a FastPrep FP120 homogenizer (Thermo Scientific) at speed 5 for 30 s, and stored at −80°C (fraction 6). Total RNA was extracted from cell fractions 1 to 6 according to the manufacturer's recommendations followed by DNase I treatment and RNA cleanup using the RNase-free DNase set and RNeasy MinElute cleanup kits (Qiagen), respectively. Total RNA was reverse transcribed with the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Gene expression analyses were performed with an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan universal PCR master mix and mouse TaqMan probes according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analyses.

All data shown represent means plus standard errors of the means (SEMs). Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t tests (two-tailed) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Generation of osteocyte-specific β-catenin loss-of-function mice.

To investigate the role of β-catenin in osteocytes in vivo, we generated osteocyte-specific β-catenin loss-of-function mice by crossing conditional β-catenin mutant mice (13) with Dmp1-Cre mice expressing Cre recombinase selectively in osteocytes under the control of a 9.6-kb promoter fragment of the dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) osteocytic marker gene (42, 62). Homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant mice (Ctnnb1loxP/loxP; Dmp1-Cre) were born at normal Mendelian frequency (data not shown) with no obvious morphological abnormalities or detectable differences in size or body weight relative to control littermates (Fig. 1A and D). Perinatal skeletal examination by whole-body skeletal radiography and skeletal staining did not reveal any distinct phenotypic differences in bone density or overall distribution of cartilaginous and bony tissue in mutant versus control pups (Fig. 1B and C). Similarly, femoral length and width were comparable between osteocyte-specific β-catenin conditional knockout (cKO) and control littermate mice (Fig. 1E), consistent with little to no Dmp1-Cre activity in osteocytes during embryonic development (42).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of newborn osteocyte-specific β-catenin gene cKO mice. (A and B) Representative photographic images (A) and whole-body skeletal radiographies (B) of postnatal day 1 (P1) homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient (cKO) and control mice. (C) Whole-mount skeleton staining of P2 homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO and control mice. (D and E) Quantification of body weight (D) and femoral length and width (E) of P1 cKO and control littermates. The values are means plus standard errors of the means (error bars). There were six mice in each group.

Osteocyte-specific deletion of Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces progressive bone loss and premature lethality.

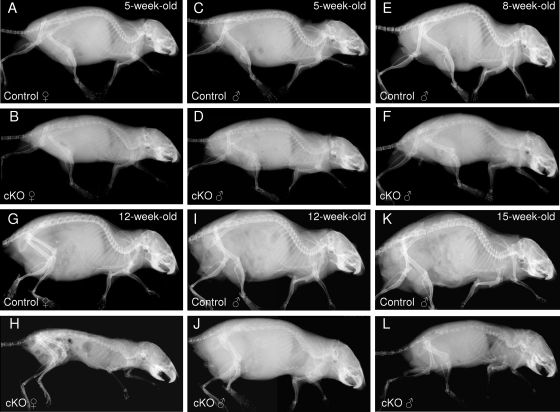

We monitored the overall bone phenotype of homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice compared to control littermates during skeletal growth by whole-body skeletal radiography and microcomputed tomography (μCT) imaging of the tibia. A progressive loss of bone density was detected throughout the skeleton in mice lacking β-catenin in osteocytes (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3A and B). Three-dimensional μCT reconstruction images of the proximal tibia half revealed that bone loss occurred throughout the tibia ranging from the midshaft to the proximal metaphysis, including the epiphysis (Fig. 3A and B). In growing female mice, the loss of bone mass appeared to be even more severe than in male mice. In addition, homozygous mutant female mice were slightly smaller in overall body size than control littermate females. While the femoral bone length was normal at birth, it decreased significantly by about 11% in male mice and 15% in female mice in 2-month-old osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice relative to heterozygous mutant or control littermate mice (Fig. 3C). The cross-sectional total bone mineral content (BMC) in the distal femur metaphysis was significantly reduced by about 40% in homozygous mutants of either sex compared to control mice (Fig. 3D). Moreover, in both sexes, body weight decreased by about 35% in homozygous, but not in heterozygous, mutant mice relative to controls (Fig. 3E). Correspondingly, homozygous osteocyte-specific loss of β-catenin resulted in premature lethality at about 3 months of age with only a few individual animals, mostly male mice, surviving up to 5 months of age (Fig. 2 and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Time course of the skeletal phenotype of osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. Representative whole-body skeletal radiographies of 5-week-old (A to D), 8-week-old (E and F), 12-week-old (G to J), and 15-week-old (K and L) homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient (cKO) and control littermate female (A, B, G, and H) and male (C to F and I to L) mice.

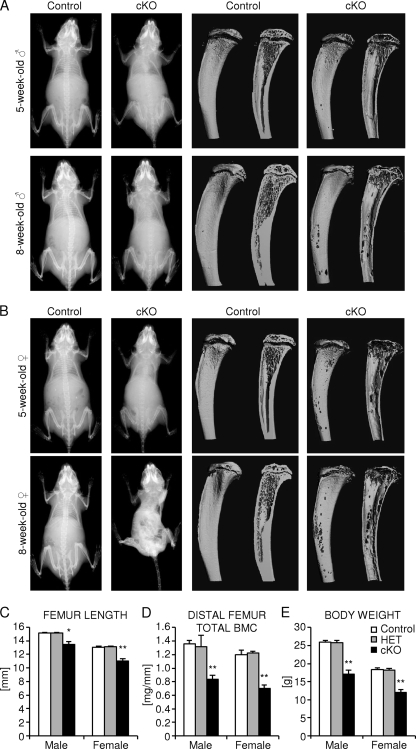

FIG. 3.

Analysis of juvenile osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. (A and B) Representative whole-body skeletal radiographies (left two columns) and μCT images of the proximal tibia to the midshaft level (right two columns) of 1-month-old (top row) and 2-month-old (bottom row) homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient (cKO) and control littermate male mice (A) and female mice (B). (C to E) Quantification of femoral length (C), cross-sectional total BMC in the distal femur metaphysis (D), and body weight (E) of 2-month-old homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient and control littermates. There were 3 to 11 mice in a group. Values for the mutant that were significantly different from the value for control littermate mice of the same gender using unpaired Student's t tests are shown as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Since high Dmp1-targeted Cre expression has been reported in odontoblasts (42), we next characterized jaw and tooth structures of 2-month-old β-catenin mutant and control mice. Surprisingly, and in contrast to the distinct phenotypic abnormalities in the appendicular and axial skeleton, the incisors appeared normal in β-catenin-deficient mice (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Therefore, feeding the mice a hard or soft diet had no effect on their skeletal phenotype.

To further investigate the underlying basis of the observed premature lethality and to exclude any extraskeletal phenotypic abnormalities possibly induced by Dmp1-Cre-mediated deletion of β-catenin, we subjected 2- and 3-month-old mutant and control littermates to a full histopathological analysis. Consistent with osteocyte-specific deletion of β-catenin, genotype-related histopathological findings were present only in skeletal tissue of homozygous β-catenin-deficient mice. No abnormal findings were present in the other tissues and organs investigated, including the heart and vasculature (data not shown). Thus, extraskeletal defects do not appear to underlie the premature lethality observed in homozygous β-catenin mutants. Skeletal defects were manifold with moderate to marked bone thinning and accompanying skeletal deformation and fractures in the appendicular and axial skeleton. Consistent with frequent skeletal fractures and associated muscle injury, serum creatine kinase levels were increased by about 175% in 2-month-old β-catenin-deficient female mice (1.8 microkatals [μKat]/liter for control females and 4.9 μKat/liter for cKO females; P < 0.01) and increased but not significantly by about 40% in mutant male mice (1.7 μKat/liter for control males and 2.4 μKat/liter for cKO males), respectively. In contrast, no significant differences in the calcium and phosphorus concentrations were observed (data not shown).

We next analyzed canonical Wnt signaling target gene expression in cortical bone of femoral diaphyses. As expected, β-catenin expression was significantly decreased in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO female mice relative to control mice (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the loss of β-catenin function, known target genes of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, such as Axin2 (29, 36, 43) and Smad6 (70), were also significantly downregulated by about 30 to 60%, respectively, in homozygous mutants relative to control mice (Fig. 4B and C). In accordance with the mostly normal bone phenotype, neither β-catenin expression nor Axin2 or Smad6 expression was significantly downregulated in heterozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice compared to controls.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of femoral and vertebral bone of osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. (A to C) Relative expression normalized to 18S for β-catenin (A) and downstream Wnt/β-catenin target genes Axin2 (B) and Smad6 (C) in cortical femoral bone from 2-month-old female mice. (D and E) Femoral cross-sectional total BMD (D) and cortical thickness (E) of 2-month-old homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) β-catenin-deficient and control littermate female mice as evaluated by ex vivo pQCT analyses (D) of five consecutive slices S1 to S5 spaced equally along the femoral axis from the distal metaphysis (S1) to the proximal end of the diaphysis (S5) or by ex vivo μCT analyses (E) in the distal metaphysis and diaphysis. (F) Representative μCT images of the femur from 2-month-old homozygous β-catenin-deficient (cKO) and control littermate female mice. (G and I) Quantification of relative cancellous bone volume in the distal femur metaphysis with representative 3D-reconstructed μCT images from male mice (G) and lumbar vertebra L3 (I) of 2-month-old homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) β-catenin-deficient and control littermates. (H) Representative H&E stained images of thoracic vertebrae from 3-month-old homozygous cKO and control female mice depicting a vertebral fracture (arrowhead) and extensive scar tissue formation (arrow). The boxes outlined by a broken line in the top row are shown at higher magnification in the bottom row. There were 3 to 11 mice in each group. Values for the mutant that were significantly different from the value for control littermate mice using unpaired Student's t tests are shown as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Bars, 1 mm (F, top row), 0.5 mm (F, bottom row), 0.5 mm (G), 0.25 mm (H, magnified view).

Osteocyte-specific deletion of β-catenin causes cortical and cancellous bone loss in the appendicular and axial skeleton.

We further characterized the low-bone-mass phenotype in 2-month-old osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice by performing ex vivo multiple-slice peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) and high-resolution μCT analyses of the appendicular and axial skeleton. In homozygous β-catenin mutant mice, femoral cross-sectional total bone mineral density (BMD) was significantly reduced by about 35 to 45% in males (data not shown) and 40 to 55% in females (Fig. 4D), depending on the respective femoral position analyzed. Heterozygous loss of osteocyte β-catenin function did not significantly alter BMD compared to control littermates of either sex (Fig. 4D and data not shown). Similarly, cortical thickness as assessed by high-resolution μCT was reduced by about 20% in the distal femur metaphysis and by about 35% in the distal diaphysis of homozygous mutant female mice relative to control animals (Fig. 4E). Moreover, in the distal femur metaphysis, the relative cortical bone volume was significantly smaller by about 12%. Metaphyseal cortical bone density was significantly reduced by about 13% compared to control mice, and diaphyseal cortical bone density was mildly yet significantly reduced by about 6% (data not shown). Reduction in cortical bone density was related to cortical porosity in the cKO animals, while bone material density was unaltered (data not shown). Consequently, as observed in the tibia (Fig. 3A and B), 3D reconstruction of the entire femur by μCT imaging revealed focal cortical thinning in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice of either sex to the extent that at certain sites cortical bone was completely absent, resulting in distinct perforations of the cortical shell being most severe in the metaphyseal regions (Fig. 4F and data not shown). Moreover, a dramatic lack of nearly all cancellous bone structures (trabeculae) was detected in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants of either sex (Fig. 4F and G). While the number of trabeculae decreased by over 95%, trabecular thickness and material BMD of the few remaining trabeculae were not significantly altered in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice compared to control mice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Bone structure and histomorphometric indices in the cancellous bone compartment of the distal femur metaphyses of control and osteocyte-specific β-catenin gene cKO mice

| Bone structure parameter or histomorphometric indexa | Mean ± SEM inb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female mice |

Male mice |

|||

| Control | cKOc | Control | cKOc | |

| Tb.N (1/mm) | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.0** | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.6** |

| Tb.Th (μm) | 37.6 ± 1.5 | 41.2 ± 15.8 | 42.7 ± 1.4 | 43.5 ± 2.6 |

| mBMD (mg/cm3) | 820.7 ± 9.1 | 793.9 ± 28.0 | 795.5 ± 8.9 | 793.8 ± 16.3 |

| dLS/BS (%) | ND | ND | 41.1 ± 4.3 | 36.2 ± 9.5 |

| MS/BS (%) | ND | ND | 50.6 ± 3.4 | 44.2 ± 7.2 |

| MAR (μm/day) | ND | ND | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1* |

| Ob.S/BS (%) | ND | ND | 22.4 ± 1.7 | 41.7 ± 0.7** |

| OS/BS (%) | ND | ND | 21.9 ± 1.5 | 39.8 ± 0.8** |

Abbreviations: BS, bone surface; dLS, double-labeled surface; MAR, mineral apposition rate; mBMD, material bone mineral density; MS, mineralizing surface; Ob.S, osteoblast surface; OS, osteoid surface; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness.

There were 2 to 11 mice in each group. ND, not determined.

Values for the 2-month-old homozygous cKO mice that were significantly different from the value for control littermate mice of the same gender using unpaired Student's t tests are shown as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Interestingly, relative cancellous bone volume decreased by about 10% in heterozygous male mice and almost 25% in heterozygous female mice relative to control littermates (Fig. 4G), demonstrating slightly enhanced sensitivity to β-catenin gene dosage reduction in female mice compared to male mice. Vertebral cancellous bone volume was almost completely absent in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice relative to control mice of either sex (Fig. 4H and I). Consequently, vertebral fractures and fibrotic scar tissue formation were frequently observed, while the overall bone marrow composition was normal in homozygous β-catenin mutants (Fig. 4H and data not shown). Osteocyte-specific heterozygosity of β-catenin function caused a significant reduction of about 20% in lumbar vertebra L3 cancellous bone volume in both sexes (Fig. 4I).

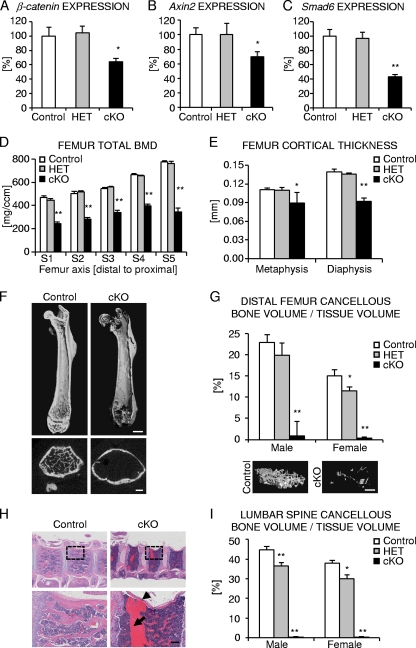

Osteocyte-specific deletion of β-catenin causes increased osteoclastic bone resorption.

To determine whether bone loss induced by osteocyte-specific β-catenin deficiency was due to enhanced bone resorption, altered bone formation, or a combination of the two, we next performed static and dynamic bone histomorphometry on the distal femur metaphyses of 2-month-old mice. At the endocortex, the number of osteoclasts as determined by quantification of TRAP-positive cells strongly increased by over four- to fivefold in homozygous β-catenin mutant mice of either sex (Fig. 5A and B). The relative osteoclast surface was similarly increased by five- to sevenfold in homozygous β-catenin mutant male and female mice compared to control animals (Table 2). Consequently, the relative eroded bone surface as a measure of osteoclastic bone resorption was elevated by about 8-fold in homozygous mutant male and over 35-fold in mutant female mice, while double-labeled bone surface and mineralizing surface reflecting sites of active bone mineralization significantly decreased by about 35% and 27% in mutant male mice and almost 55% and 45% in homozygous β-catenin-deficient female mice relative to controls (Table 2). These results are however likely impacted by the extreme nature of bone resorption, which even in the short 1-week interval between the application of the two fluorochrome labels probably led to removal of part of the bone containing fluorochrome markers.

FIG. 5.

Histomorphometric analysis of femoral bone of osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. (A, C, E, and F) Quantification of the number of osteoclasts (A and C) and bone formation rate (BFR) at endocortical (A and E) and cancellous (C and F) femoral bone surfaces in 2-month-old homozygous (cKO), heterozygous (HET) osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient and control mice. (B, C, D, and F) Representative images of TRAP staining at the femoral endocortex of female mice (B [the arrows delineate the extent of cortices]) and the cancellous bone compartment in male mice (D) or depicting fluorochrome marker labeling in male femora (C and F). (G and H) Quantification of serum osteocalcin levels (G) and ALP levels (H) in 2-month-old mice. There were 2 to 11 mice in each group. Values for the mutant that were significantly different from the value for control littermate mice using unpaired Student's t tests are shown as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Bars, 50 μm (B and D), 2 μm (E), and 10 μm (F).

TABLE 2.

Histomorphometric indices in the distal femur metaphysis endocortex of control and osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice

| Histomorphometric indexa | Mean ± SEM inb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female mice |

Male mice |

|||

| Control | cKOc | Control | cKOc | |

| dLS/BS (%) | 72.4 ± 6.0 | 33.7 ± 6.4** | 78.1 ± 4.0 | 49.7 ± 5.2** |

| MS/BS (%) | 77.0 ± 5.2 | 43.3 ± 4.5** | 83.0 ± 3.0 | 60.2 ± 6.2* |

| MAR (μm/day) | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.3* | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 1.1 |

| Ob.S/BS (%) | 80.0 ± 2.1 | 67.2 ± 5.5 | 42.7 ± 2.4 | 52.9 ± 11.5 |

| OS/BS (%) | 73.9 ± 2.3 | 61.7 ± 5.4 | 46.1 ± 3.2 | 53.8 ± 10.8 |

| Oc.S/BS (%) | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 17.1 ± 1.5** | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 1.7* |

| ES/BS (%) | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 42.6 ± 5.6** | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 26.0 ± 8.0** |

Abbreviations: BS, bone surface; dLS, double-labeled surface; ES, eroded surface; MAR, mineral apposition rate; MS, mineralizing surface; Ob.S, osteoblast surface; Oc.S, osteoclast surface; OS, osteoid surface.

There were 3 to 11 mice in each group.

Values for 2-month-old homozygous cKO mice that were significantly different from the value for control littermate mice of the same gender using unpaired Student's t tests are shown as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

We then determined the number of osteoclasts in the cancellous bone compartment. In homozygous mutant female mice, essentially the entire cancellous bone was lost, and growth plates were either missing or severely damaged, in line with the mild growth retardation observed in homozygous mutant animals (Fig. 3B and C, Fig. 4F and G, and data not shown). We therefore limited our histomorphometric evaluation of the cancellous bone compartment to male mice in which the overall bone phenotype although similar was slightly less severe. On the very few remaining trabeculae, the number of osteoclasts increased by about 10% but not statistically significant (Fig. 5C and D). Osteoclast morphology was comparable between genotypes in both bone compartments (Fig. 5B and D and data not shown). Double-labeled surface and mineralizing trabecular bone surface were mildly decreased by about 10% (not statistically significant) in homozygous cKO relative to control males (Table 1). Moreover, osteoblast and osteoid surface, the latter representing newly deposited unmineralized collagenous extracellular matrix, were elevated by about 85% in the cancellous bone compartment and by about 20% (not statistically significant) at the endocortex in mutant males compared to control littermates (Tables 1 and 2). Likewise, osteoblastic mineral apposition rate was increased by about 30 to 45% in both bone compartments (Tables 1 and 2), and bone formation rates were comparable between osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant and control littermate males (Fig. 5E and F), indicating normal to slightly elevated osteoblast number and activity.

In female mice, relative osteoblast and osteoid surfaces were not significantly different at the endocortex of homozygous mutant compared to control mice (Table 2). Similar to male mice, osteoblastic mineral apposition rate reflecting osteoblast performance was significantly increased by about 40% at the endocortex of homozygous mutant female mice compared to control mice (Table 2). However, since the relative mineralizing surface was decreased (Table 2), probably as a result of the vast increase in bone resorption, the overall bone formation rate was not significantly different in homozygous cKO female mice compared to control mice (Fig. 5E).

Finally, to further assess osteoclast and osteoblast function in osteocyte-specific β-catenin loss-of-function mice, we measured serum bone biomarkers. Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity was increased by about 25% (not significantly statistically) in 2-month-old homozygous osteocyte β-catenin-deficient male mice (3.4 U/liter in control males and 4.2 U/liter in cKO males) and by about 55% in cKO female mice (1.7 U/liter in control females and 2.7 U/liter in cKO females). Similarly, the concentration of C-telopeptide fragments of collagen type I (CTX-I) was elevated by about 55% (not significantly statistically) in 2.5-month-old mutant male mice (75.6 ng/ml in control males and 116.6 ng/ml in cKO males) and by about 35% in 2-month-old mutant female mice (53.7 ng/ml in control females and 73.0 ng/ml) in cKO females. Serum osteocalcin levels as a biomarker for active osteoblastic bone formation were comparable in hetero- and homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant mice (Fig. 5G). Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was not significantly different in mutant male mice but was mildly increased by about 15% in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant female mice (Fig. 5H), consistent with overall normal to slightly elevated osteoblast activity.

Osteocyte density is normal in osteocyte-specific β-catenin loss-of-function mice.

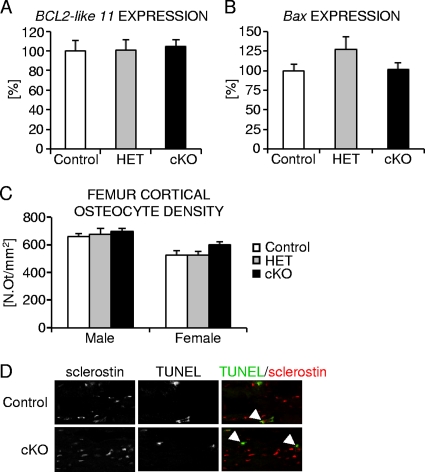

Osteocyte apoptosis has been shown to result in increased osteoclast recruitment and bone resorption (1, 16, 20, 22, 34, 49, 61). We therefore determined the levels of expression of the apoptosis facilitators Bcl2-like 11/Bim and BCL2-associated X protein (Bax) (38, 65) in femoral diaphyses of 2-month-old mutant and control female mice. Neither Bcl2-like 11/Bim nor Bax expression were significantly altered in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant mice relative to control mice (Fig. 6A and B). We next quantified cortical osteocyte density in femoral cortical bone from 2-month-old hetero- and homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient and control mice (Fig. 6C). Cortical osteocyte density was normal irrespective of osteocyte β-catenin gene dosage. Moreover, osteocyte apoptosis was low, and no major differences were detected in β-catenin mutant femora compared to controls (Fig. 6D), as assessed in 2-week-old mice by TUNEL staining combined with immunofluorescence detection of the osteocyte marker sclerostin (64, 68). Similarly, we did not find any evidence for increased presence of empty osteocyte lacunae in 2-month-old homozygous β-catenin cKO mice relative to control mice (data not shown). Thus, osteocyte-specific loss of β-catenin gene function does not appear to result in significantly elevated apoptotic or necrotic osteocyte death.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of femoral cortical osteocyte number and apoptosis in osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. (A to C) Quantification of relative expression of the proapoptotic marker genes BCL2-like 11/Bim (A) and Bax (B) normalized to 18S and osteocyte density (C) in femoral cortical bone of homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) β-catenin-deficient and control female mice. N.Ot/mm2, number of osteocytes per square millimeter. (D) Representative confocal microscopic images depicting TUNEL-positive osteocytes (green) expressing the osteocyte marker sclerostin (red) in femoral cortex of P14 homozygous cKO and control mice. There were 3 to 11 mice in each group.

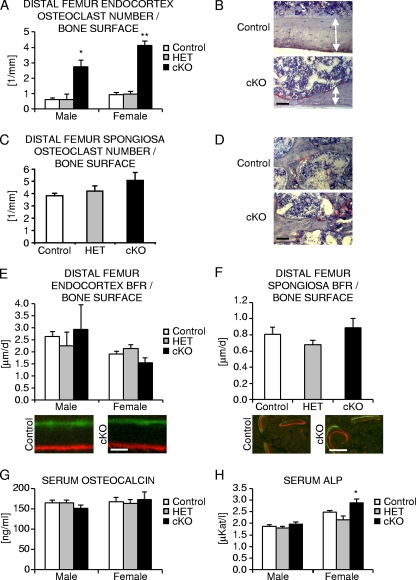

Osteocyte-specific deletion of Wnt/β-catenin signaling causes decreased OPG expression.

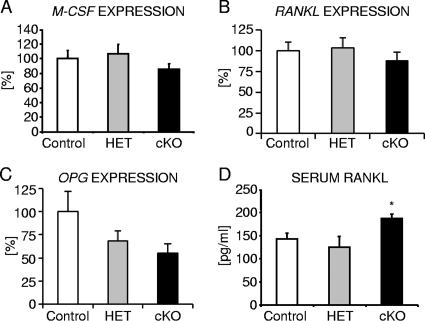

Osteoclast differentiation from osteoclast progenitors is controlled by the action of two major cytokines, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) (63), both of which are expressed by cells of the osteoblast lineage and stromal cells. Moreover, osteoblasts also secrete osteoprotegerin (OPG), a soluble RANKL decoy receptor that antagonizes the proosteoclastogenic activity of RANKL by preventing it from binding to its cognate RANK receptor present on osteoclasts and their precursor cells (12). Thus, the relative RANKL/OPG ratio determines bone mass and strength, and high OPG levels are protective against excessive osteoclastic bone resorption. Therefore, we next characterized the relative levels of expression of M-CSF, RANKL, and OPG in cortical bone samples of 2-month-old osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient and control littermate female mice. Neither M-CSF nor RANKL expression was significantly altered in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants compared to control mice (Fig. 7A and B). However, consistent with OPG being a Wnt/β-catenin target gene (19, 26, 69), OPG expression was significantly decreased by about 50% in femoral diaphyseal bone (Fig. 7C). Conversely, serum RANKL protein concentration was elevated by about 35% in osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice of either sex (Fig. 7D and data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Analysis of the levels of expression of osteoclastic differentiation factors in osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. (A to C) The level of expression normalized to 18S of M-CSF (A), RANKL (B), and OPG (C) in cortical bone of femur diaphyses from 2-month-old homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) β-catenin-deficient and control littermate female mice. (D) Quantification of RANKL protein in serum of 2-month-old homozygous (cKO) and heterozygous (HET) β-catenin-deficient and control littermate males. There were 4 to 9 mice in each group. Values for the mutant that were significantly different (P < 0.05) from the value for control littermate mice using unpaired Student's t tests are indicated (*).

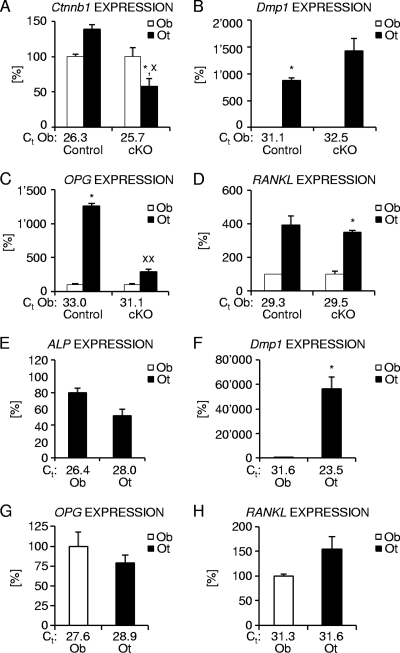

To assess whether the observed gene expression differences in femoral diaphyses from osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant and control mice could indeed be due to changes in osteocytic gene expression, as assumed given the abundance of osteocytes in cortical bone relative to bone surface adherent osteoblasts, we next analyzed selective osteoblast- and osteocyte-enriched cell populations obtained by sequential enzymatic digestion of femoral diaphyses from 6-week-old osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant and control male mice. Based on the respective expression of osteocyte marker genes Dmp1 (10, 62) and Sost (10, 57, 64, 68) as well as the osteoblast marker integrin binding sialoprotein (6), fraction 6 was found to be strongly enriched in osteocytes, while cell fraction 3 of control femora and fraction one in homozygous osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants, respectively, were identified as containing mostly osteoblasts (Fig. 8B and data not shown). Cortical osteocytes of control bone expressed about 40% higher levels of β-catenin than osteoblasts did, whereas this ratio was inverted in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant mice, indicating specific loss of β-catenin gene function in about 50% of cortical osteocytes (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, at 6 weeks of age, femoral osteocytes of control mice expressed considerably higher levels of the osteoclastogenic regulators OPG and RANKL than femoral osteoblasts (Fig. 8C and D). Moreover, osteocyte-specific β-catenin deficiency resulted in a selective decrease of OPG expression in osteocytes relative to osteoblasts, whereas osteocytic RANKL expression was not significantly altered (Fig. 8C and D). Therefore, these data suggest that the selective decrease in osteocyte OPG expression contributes to the elevated bone resorption present in osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of the levels of expression of osteoclastic differentiation factors in osteoblast- and osteocyte-enriched femoral bone fractions. (A to D) Relative expression of β-catenin (A), the osteocyte marker Dmp1 (B), and osteoclastic differentiation regulators OPG (C) and RANKL (D) in osteoblast (Ob)- and osteocyte (Ot)-enriched femoral bone fractions from 6-week-old homozygous (cKO) β-catenin-deficient and control littermate male mice. (E to H) Expression normalized to 18S for the osteoblast marker ALP (E), the osteocyte marker Dmp1 (F), and osteoclast regulators OPG (G) and RANKL (H) in osteoblast (Ob)- and osteocyte (Ot)-enriched fractions of femora from 4-month-old skeletally mature wild-type female mice. The threshold cycle (Ct) values for each marker are indicated for osteoblast (A to H)- and osteocyte (E to H)- enriched fractions. There were 2 to 5 mice in each group. Values for the osteblast fraction that were significantly different from the value for the osteocyte fraction using paired Student's t tests are shown as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Values for the mutant mice that were significantly different from the value for control littermate mice using unpaired Student's t tests are shown as follows: x, P < 0.05; xx, P < 0.01.

Finally, to determine whether cortical osteocytes also express significant levels of OPG and RANKL at skeletal maturity, we performed quantitative gene expression analyses using cellular fractions isolated from the femora of 4-month-old wild-type mice. As in femora of younger mice, cell fractions 3 and 6 were identified as containing mostly osteoblasts or osteocytes, respectively, based on the relative expression levels of the osteoblast marker gene ALP and the osteocyte marker Dmp1 as well as other markers (Fig. 8E and F and data not shown). Compared to skeletally growing mice, osteoblastic OPG expression was increased, while osteoblastic RANKL expression was slightly lower. Importantly, cortical osteocytes of skeletally mature mice expressed OPG and RANKL at levels comparable to those found in osteoblasts (Fig. 8G and H).

DISCUSSION

Here, we describe the consequences of loss of Wnt/β-catenin signaling specifically in osteocytes using a conditional mouse genetic approach (Ctnnb1loxP/loxP; Dmp1-Cre mice). Unexpectedly, osteocyte-specific deletion of the β-catenin gene led to early-onset, dramatic bone loss due to elevated osteoclast number and activity, which correlated with the selective downregulation of the anti-osteoclastogenic factor OPG in cortical osteocytes. Analysis of β-catenin expression in femoral digestion fractions confirmed that β-catenin expression was indeed specifically downregulated in osteocytes but was normal in femoral osteoblast-enriched cell fractions of Ctnnb1loxP/loxP; Dmp1-Cre mice. While specific, β-catenin expression in femoral osteocyte fractions was however reduced by only about 50% compared to control osteocytes. Thus, Dmp1-Cre-mediated homozygous deletion of β-catenin gene function in osteocytes was incomplete, in line with previous observations (42). Despite this caveat of the transgenic Dmp1-Cre driver line, the bone phenotypic consequences of the partial loss of osteocyte β-catenin activity were dramatic, thus underscoring the importance of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocytes for normal bone homeostasis.

Overall, the phenotype of osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice strongly resembles the one described for osteoblast-targeted β-catenin-deficient mice (19, 26). Since in osteoblast-targeted cKO mice, β-catenin was deleted from the osteoblast stage of the mesenchymal cell lineage onwards, it was not only removed in osteoblasts but also in their cellular descendants, including osteocytes. Thus, it is likely that loss of β-catenin gene function in osteocytes contributed to the observed bone resorption phenotype present in osteoblast-targeted β-catenin-deficient mice. Yet, β-catenin deficiency induced at the early osteoblast stage by Col1α1-Cre caused only a comparably mild bone loss, and homozygous mutants displayed a normal life span (19). This might be explained by differences in genetic background as well as incomplete genetic penetrance of Col1α1-Cre-mediated β-catenin gene recombination (19). In contrast, the phenotype of OC-Cre-driven β-catenin deficiency leading to the loss of β-catenin from the late osteoblast stage onwards was slightly more severe in terms of lethality compared to osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants (26). Whereas OC-Cre-dependent β-catenin mutant mice died within 30 to 45 days after birth, Dmp1-Cre-induced mutants were viable for a few months. Although the low-bone-mass phenotypes of both models appear qualitatively similar, the absolute decrease in relative cancellous bone volume and BMD cannot be directly compared due to differences in the respective applied methodology (26).

In line with overlapping as well as distinct functions of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts and osteocytes, deletion of β-catenin in late osteoblasts using OC-Cre resulted in decreased osteoblast numbers in vivo (26). In contrast, osteoblast numbers and osteocyte density were normal in osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that osteoblasts lacking β-catenin enhance osteoclastogenesis in vitro (19). As expected and consistent with the osteocyte specificity of our model, in vitro coculture experiments did not reveal induction of increased osteoclastogenesis by osteoblasts derived from osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice (data not shown). Furthermore, whereas in cultured β-catenin-deficient osteoblasts, expression of the late osteoblastic differentiation marker osteocalcin was reduced and mineralized nodule formation was diminished (26), serum osteocalcin levels were normal in osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. We formally cannot exclude a minor delay in bone matrix mineralization in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants, since osteoid surface was significantly increased in the cancellous bone compartment. However, this was not observed at the endocortex. Moreover, as osteoblast surface and osteoblastic mineral apposition rates were also elevated, the increase in trabecular osteoid surface probably reflects enhanced osteoblastic matrix deposition in an attempt to compensate for the vast bone loss occurring in osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice. In line with largely undisturbed bone formation, trabecular thickness and material BMD were not significantly altered in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants, indicating that in general, mineralization was normal in osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. In addition, the histomorphometric analysis of the cancellous bone compartment was somewhat hampered by the fact that very little trabecular bone surface was available in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutants. This may also explain the seemingly surprising finding that the number of osteoclasts was only mildly increased on trabecular bone compared to endosteal bone surfaces. Hence, it appears that the enhanced phenotypic severity of OC-Cre-driven osteoblast versus Dmp1-Cre-dependent osteocyte β-catenin deficiency could be due to the selective decrease in osteoblast number and activity in OC-Cre- but not in Dmp1-Cre-dependent β-catenin mutant mice. In contrast, both mouse models revealed a comparable elevation in osteoclastic bone resorption parameters, indicating that β-catenin expression in osteocytes is at least equally important for control of bone resorption as it is in osteoblasts.

Osteoclasts have recently been shown to stimulate osteoblast differentiation by secreting Wnt ligands and chemoattractants, thereby contributing to coupling of bone resorption and formation during skeletal remodeling (54). Conversely, cells of the osteoblast lineage are known to impact osteoclastogenesis in a non-cell-autonomous fashion by expressing the osteoclast differentiation factor RANKL and its decoy receptor OPG (24, 46). In line with previous findings by us and others (34, 51, 71, 73), cellular fractionation by sequential digestion of femoral diaphyses revealed that primary osteocytes in skeletally growing mice and mature mice robustly express OPG and RANKL at levels exceeding or comparable to those present in osteoblasts. Although it is currently unclear whether osteocyte-expressed cytokines are indeed released into the lacunar-canalicular network, theoretical models and tracer experiments have demonstrated that small globular proteins of up to 7 nm in diameter and 70 kDa, the estimated size of serum albumin, can pass through the osteocyte canalicular system (60, 66, 67). Therefore, theoretically, molecules of the size of monomeric OPG (60 kDa), but not soluble RANKL, which is thought to be a nondisulfide-linked homotrimer (35), may pass through the osteocyte lacunar-canalicular system. In addition, osteocytes might secrete other small modulators of osteoclast and/or osteoblast function and diffusible chemoattractants or chemorepellents to establish local chemotactic gradients that might specifically guide osteoclasts and/or osteoblasts or their respective precursors to sites of local bone turnover at the bone surface and/or intracortical bone-vascular endothelial interfaces (14, 20, 23, 34, 45).

The level of expression of OPG increased in osteoblast-targeted β-catenin gain-of-function mice (19). Conversely, it was found to be decreased in osteoblast- as well as osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mouse models, providing a putative molecular mechanism contributing to the observed increase in osteoclastic bone resorption (19, 26). However, given the slightly less severe low-bone-mass phenotype of constitutive OPG loss-of-function mice, which is characterized by a high bone turnover state of excessive bone resorption and elevated bone formation (15, 48), downregulation of OPG alone cannot fully account for the observed phenotype of osteoblast- and osteocyte-targeted β-catenin-deficient mice.

In osteoblast-targeted β-catenin-deficient mice, RANKL expression was not significantly altered in vivo (19). Yet, it was increased in cultured primary calvarial osteoblasts lacking β-catenin function, whereas the converse was found in osteoblasts from Wnt/β-catenin gain-of-function mice (26). Interestingly, in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant mice, serum RANKL levels were slightly increased, whereas RANKL expression in cortical bone remained normal. There are several conceivable putative mechanisms that may underlie the observed increase in serum RANKL in osteocyte-specific β-catenin cKO mice. It is possible that loss of β-catenin function in osteocytes may induce a signal transferred from osteocytes to osteoblasts and/or bone marrow stroma cells that causes upregulation of RANKL expression in these cell types in a non-cell-autonomous manner. Conversely, it is conceivable that Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocytes might control expression of a negative regulator of RANKL expression. Alternatively, as only soluble RANKL, not surface-bound RANKL, is detected, increased release of cell surface-bound RANKL may have occurred in osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice. Finally, the increase in serum RANKL may be directly linked to the decreased osteocyte expression of OPG, as RANKL bound to OPG was not detected by our assay. If true, the level of osteocyte-expressed RANKL should determine the relative fraction of osteocyte-secreted OPG that is complexed and thus trapped in the osteocyte lacunar-canalicular system as opposed to unbound OPG that may pass through the canalicular system into circulation to exert its antiosteoclastic function. In line with this interpretation, the amount of detectable RANKL would thus increase in circulation with reduced osteocytic secretion of OPG. Furthermore, we noticed that osteocyte OPG expression levels were considerably smaller, while osteocyte RANKL expression levels were slightly higher in skeletally growing control mice undergoing bone modeling and high bone turnover compared to skeletally mature wild-type mice. This thus further suggests that the osteocyte RANKL/OPG expression ratio is critical for control of bone homeostasis. While at present, we can neither distinguish between these possibilities nor do we know the cellular source of the measured serum RANKL, the net outcome will be the same, namely, an increase in RANKL/OPG ratio favoring osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast survival in osteocyte-specific β-catenin mutant mice. Interestingly, in MLO-Y4 osteocyte-like cells, which express RANKL and OPG (73), the RANKL/OPG ratio decreases when cells are subjected to shear stress (71). This suggests that mechanical load reduces the soluble RANKL/OPG ratio, preventing osteoclast activation by osteocytes. Hence, one may speculate that mechanosensation and/or transduction might be compromised in β-catenin-deficient osteocytes, in line with previous findings implicating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocyte mechanotransduction (11, 39, 56-58).

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been implicated in the regulation of apoptotic cell death of cells of the osteoblast lineage in some instances (4, 7, 39), but not others (5, 31, 69). Moreover, osteocyte apoptosis correlates with increased osteoclast recruitment and bone resorption (1, 16, 20, 22, 34, 49, 61). While the underlying reason for the decreased osteoblast number in osteoblast-specific OC-Cre-directed β-catenin cKO mice was not reported (26), TUNEL analyses of Col1α1-Cre-mediated osteoblast-specific β-catenin gain- or loss-of-function mutant mice revealed normal levels of programmed cell death (19). Consistent with these reports, cortical osteocyte density and apoptotic marker gene expression were normal in 2-month-old osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice and TUNEL staining in 2-week-old β-catenin cKO mice was comparable to control littermate mice. This suggests that β-catenin is not required for osteocyte viability but that it plays a role is osteocyte signaling.

With respect to gender specificity, we found that progression of bone loss was faster and for most parameters analyzed, such as bone mass, cortical width, serum creatine kinase level, and osteoclast eroded surface, slightly more severe in female than male osteocyte-specific β-catenin-deficient mice. Gender-specific enhanced sensitivity of female mice toward modulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling was also reported for other loss-of-function mutants of Wnt/β-catenin signaling components (37, 50, 72). Whether these observations are due to cross talk of Wnt/β-catenin and sex steroid signaling pathways or related to sexually dimorphic bone mass accrual, bone turnover, and/or osteocyte mechanotransduction (3, 41, 59, 72) is currently unknown and remains to be addressed by future studies.

Finally, in addition to being an essential mediator of canonical Wnt signaling, β-catenin also binds to cadherins and α-catenin at adherens junctions linking cell adhesion to the actin cytoskeleton (47). Moreover, under conditions of elevated oxidative stress, β-catenin has been found to associate with forkhead box O (FoxO) transcription factors to upregulate expression of oxidative stress response target genes at the expense of canonical Wnt target gene transcription (2, 44). Therefore, we currently do not exclude the possibility that in addition to blocking Wnt/β-catenin signaling as demonstrated by decreased expression of canonical Wnt target genes, other signaling pathways might be compromised in osteocyte-specific β-catenin loss-of-function mice. Future investigations will need to assess the roles of these signaling pathways and of noncanonical Wnt signaling in osteocytes in vivo.

Together our findings reveal a previously underestimated novel important function for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteocytes. In particular, we demonstrate that osteocyte β-catenin is required for expression of the antiosteoclastogenic factor OPG in osteocytes and that osteocytes express RANKL and OPG at levels comparable to or exceeded those of osteoblasts. These data suggest that the RANKL/OPG ratio expressed by osteocytes may determine osteoclast recruitment and activation, which is in line with the long-standing hypothesis of osteocytes being key regulators of bone homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research Education Office Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (I.K.) and by NIH NIAMS PO1 AR046798 (L.F.B. and J.Q.F.).

We thank Tanja Grabenstätter, Gabriela Guiglia, Peter Ingold, Heidi Jeker, Marcel Merdes, Philippe Scheubel, Renzo Schumpf, Andrea Venturiere, Carrie Zhao, and Mark Dallas for excellent technical assistance as well as Keiko Petrosky for providing vertebral μCT data and David Ledieu for clinical blood biochemistry data.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguirre, J. I., L. I. Plotkin, S. A. Stewart, R. S. Weinstein, A. M. Parfitt, S. C. Manolagas, and T. Bellido. 2006. Osteocyte apoptosis is induced by weightlessness in mice and precedes osteoclast recruitment and bone loss. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21:605-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida, M., L. Han, M. Martin-Millan, C. A. O'Brien, and S. C. Manolagas. 2007. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 282:27298-27305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong, V. J., M. Muzylak, A. Sunters, G. Zaman, L. K. Saxon, J. S. Price, and L. E. Lanyon. 2007. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a component of osteoblastic bone cell early responses to load-bearing and requires estrogen receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 282:20715-20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babij, P., W. Zhao, C. Small, Y. Kharode, P. J. Yaworsky, M. L. Bouxsein, P. S. Reddy, P. V. Bodine, J. A. Robinson, B. Bhat, J. Marzolf, R. A. Moran, and F. Bex. 2003. High bone mass in mice expressing a mutant LRP5 gene. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18:960-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett, C. N., H. Ouyang, Y. L. Ma, Q. Zeng, I. Gerin, K. M. Sousa, T. F. Lane, V. Krishnan, K. D. Hankenson, and O. A. MacDougald. 2007. Wnt10b increases postnatal bone formation by enhancing osteoblast differentiation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22:1924-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson, M. D., J. E. Aubin, G. Xiao, P. E. Thomas, and R. T. Franceschi. 1999. Cloning of a 2.5 kb murine bone sialoprotein promoter fragment and functional analysis of putative Osf2 binding sites. J. Bone Miner. Res. 14:396-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodine, P. V., W. Zhao, Y. P. Kharode, F. J. Bex, A. J. Lambert, M. B. Goad, T. Gaur, G. S. Stein, J. B. Lian, and B. S. Komm. 2004. The Wnt antagonist secreted frizzled-related protein-1 is a negative regulator of trabecular bone formation in adult mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 18:1222-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonewald, L. F. 2005. Generation and function of osteocyte dendritic processes. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 5:321-324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonewald, L. F. 2006. Mechanosensation and transduction in osteocytes. Bonekey Osteovision 3:7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonewald, L. F. 2007. Osteocytes as dynamic multifunctional cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1116:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonewald, L. F., and M. L. Johnson. 2008. Osteocytes, mechanosensing and Wnt signaling. Bone 42:606-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyce, B. F., and L. Xing. 2008. Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473:139-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brault, V., R. Moore, S. Kutsch, M. Ishibashi, D. H. Rowitch, A. P. McMahon, L. Sommer, O. Boussadia, and R. Kemler. 2001. Inactivation of the beta-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development 128:1253-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breuil, V., H. Schmid-Antomarchi, A. Schmid-Alliana, R. Rezzonico, L. Euller-Ziegler, and B. Rossi. 2003. The receptor activator of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB ligand (RANKL) is a new chemotactic factor for human monocytes. FASEB J. 17:1751-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucay, N., I. Sarosi, C. R. Dunstan, S. Morony, J. Tarpley, C. Capparelli, S. Scully, H. L. Tan, W. Xu, D. L. Lacey, W. J. Boyle, and W. S. Simonet. 1998. Osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 12:1260-1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardoso, L., B. C. Herman, O. Verborgt, D. Laudier, R. J. Majeska, and M. B. Schaffler. 2009. Osteocyte apoptosis controls activation of intracortical resorption in response to bone fatigue. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24:597-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caverzasio, J. 2009. Non-canonical Wnt signaling: what is its role in bone? Bonekey 6:107-115. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day, T. F., X. Guo, L. Garrett-Beal, and Y. Yang. 2005. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev. Cell 8:739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glass, D. A., II, P. Bialek, J. D. Ahn, M. Starbuck, M. S. Patel, H. Clevers, M. M. Taketo, F. Long, A. P. McMahon, R. A. Lang, and G. Karsenty. 2005. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev. Cell 8:751-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu, G., M. Mulari, Z. Peng, T. A. Hentunen, and H. K. Vaananen. 2005. Death of osteocytes turns off the inhibition of osteoclasts and triggers local bone resorption. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335:1095-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu, G., M. Nars, T. A. Hentunen, K. Metsikko, and H. K. Vaananen. 2006. Isolated primary osteocytes express functional gap junctions in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 323:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedgecock, N. L., T. Hadi, A. A. Chen, S. B. Curtiss, R. B. Martin, and S. J. Hazelwood. 2007. Quantitative regional associations between remodeling, modeling, and osteocyte apoptosis and density in rabbit tibial midshafts. Bone 40:627-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heino, T. J., T. A. Hentunen, and H. K. Vaananen. 2004. Conditioned medium from osteocytes stimulates the proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation into osteoblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 294:458-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henriksen, K., A. V. Neutzsky-Wulff, L. F. Bonewald, and M. A. Karsdal. 2009. Local communication on and within bone controls bone remodeling. Bone 44:1026-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill, T. P., D. Spater, M. M. Taketo, W. Birchmeier, and C. Hartmann. 2005. Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev. Cell 8:727-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmen, S. L., C. R. Zylstra, A. Mukherjee, R. E. Sigler, M. C. Faugere, M. L. Bouxsein, L. Deng, T. L. Clemens, and B. O. Williams. 2005. Essential role of beta-catenin in postnatal bone acquisition. J. Biol. Chem. 280:21162-21168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu, H., M. J. Hilton, X. Tu, K. Yu, D. M. Ornitz, and F. Long. 2005. Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 132:49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inouye, M. 1976. Differential staining of cartilage and bone in fetal mouse skeleton by alcian blue and alizarin red-S. Congen. Anom. 16:171-173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jho, E. H., T. Zhang, C. Domon, C. K. Joo, J. N. Freund, and F. Costantini. 2002. Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1172-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamioka, H., T. Honjo, and T. Takano-Yamamoto. 2001. A three-dimensional distribution of osteocyte processes revealed by the combination of confocal laser scanning microscopy and differential interference contrast microscopy. Bone 28:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato, M., M. S. Patel, R. Levasseur, I. Lobov, B. H. Chang, D. A. Glass II, C. Hartmann, L. Li, T. H. Hwang, C. F. Brayton, R. A. Lang, G. Karsenty, and L. Chan. 2002. Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J. Cell Biol. 157:303-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller, H., and M. Kneissel. 2005. SOST is a target gene for PTH in bone. Bone 37:148-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kneissel, M., A. Boyde, and J. A. Gasser. 2001. Bone tissue and its mineralization in aged estrogen-depleted rats after long-term intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone (PTH) analog SDZ PTS 893 or human PTH(1-34). Bone 28:237-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurata, K., T. J. Heino, H. Higaki, and H. K. Vaananen. 2006. Bone marrow cell differentiation induced by mechanically damaged osteocytes in 3D gel-embedded culture. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21:616-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam, J., C. A. Nelson, F. P. Ross, S. L. Teitelbaum, and D. H. Fremont. 2001. Crystal structure of the TRANCE/RANKL cytokine reveals determinants of receptor-ligand specificity. J. Clin. Invest. 108:971-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leung, J. Y., F. T. Kolligs, R. Wu, Y. Zhai, R. Kuick, S. Hanash, K. R. Cho, and E. R. Fearon. 2002. Activation of AXIN2 expression by beta-catenin-T cell factor. A feedback repressor pathway regulating Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21657-21665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, X., M. S. Ominsky, Q. T. Niu, N. Sun, B. Daugherty, D. D'Agostin, C. Kurahara, Y. Gao, J. Cao, J. Gong, F. Asuncion, M. Barrero, K. Warmington, D. Dwyer, M. Stolina, S. Morony, I. Sarosi, P. J. Kostenuik, D. L. Lacey, W. S. Simonet, H. Z. Ke, and C. Paszty. 2008. Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23:860-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang, M., G. Russell, and P. A. Hulley. 2008. Bim, Bak, and Bax regulate osteoblast survival. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23:610-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, C., X. Jiang, Z. Dai, X. Guo, T. Weng, J. Wang, Y. Li, G. Feng, X. Gao, and L. He. 2009. Sclerostin mediates bone response to mechanical unloading through antagonizing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24:1651-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, F., S. Kohlmeier, and C. Y. Wang. 2008. Wnt signaling and skeletal development. Cell Signal. 20:999-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, X. H., A. Kirschenbaum, S. Yao, and A. C. Levine. 2007. Androgens promote preosteoblast differentiation via activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1116:423-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu, Y., Y. Xie, S. Zhang, V. Dusevich, L. F. Bonewald, and J. Q. Feng. 2007. DMP1-targeted Cre expression in odontoblasts and osteocytes. J. Dent. Res. 86:320-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lustig, B., B. Jerchow, M. Sachs, S. Weiler, T. Pietsch, U. Karsten, M. van de Wetering, H. Clevers, P. M. Schlag, W. Birchmeier, and J. Behrens. 2002. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1184-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manolagas, S. C., and M. Almeida. 2007. Gone with the Wnts: beta-catenin, T-cell factor, forkhead box O, and oxidative stress in age-dependent diseases of bone, lipid, and glucose metabolism. Mol. Endocrinol. 21:2605-2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin, R. B. 2000. Does osteocyte formation cause the nonlinear refilling of osteons? Bone 26:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin, T., J. H. Gooi, and N. A. Sims. 2009. Molecular mechanisms in coupling of bone formation to resorption. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 19:73-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mbalaviele, G., C. S. Shin, and R. Civitelli. 2006. Cell-cell adhesion and signaling through cadherins: connecting bone cells in their microenvironment. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21:1821-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mizuno, A., N. Amizuka, K. Irie, A. Murakami, N. Fujise, T. Kanno, Y. Sato, N. Nakagawa, H. Yasuda, S. Mochizuki, T. Gomibuchi, K. Yano, N. Shima, N. Washida, E. Tsuda, T. Morinaga, K. Higashio, and H. Ozawa. 1998. Severe osteoporosis in mice lacking osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor/osteoprotegerin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247:610-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noble, B. S., N. Peet, H. Y. Stevens, A. Brabbs, J. R. Mosley, G. C. Reilly, J. Reeve, T. M. Skerry, and L. E. Lanyon. 2003. Mechanical loading: biphasic osteocyte survival and targeting of osteoclasts for bone destruction in rat cortical bone. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284:C934-C943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noh, T., Y. Gabet, J. Cogan, Y. Shi, A. Tank, T. Sasaki, B. Criswell, A. Dixon, C. Lee, J. Tam, T. Kohler, E. Segev, L. Kockeritz, J. Woodgett, R. Muller, Y. Chai, E. Smith, I. Bab, and B. Frenkel. 2009. Lef1 haploinsufficient mice display a low turnover and low bone mass phenotype in a gender- and age-specific manner. PLoS One 4:e5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onyia, J. E., R. R. Miles, X. Yang, D. L. Halladay, J. Hale, A. Glasebrook, D. McClure, G. Seno, L. Churgay, S. Chandrasekhar, and T. J. Martin. 2000. In vivo demonstration that human parathyroid hormone 1-38 inhibits the expression of osteoprotegerin in bone with the kinetics of an immediate early gene. J. Bone Miner. Res. 15:863-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paic, F., J. C. Igwe, R. Nori, M. S. Kronenberg, T. Franceschetti, P. Harrington, L. Kuo, D. G. Shin, D. W. Rowe, S. E. Harris, and I. Kalajzic. 2009. Identification of differentially expressed genes between osteoblasts and osteocytes. Bone 45:682-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parfitt, A. M., M. K. Drezner, F. H. Glorieux, J. A. Kanis, H. Malluche, P. J. Meunier, S. M. Ott, and R. R. Recker. 1987. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2:595-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pederson, L., M. Ruan, J. J. Westendorf, S. Khosla, and M. J. Oursler. 2008. Regulation of bone formation by osteoclasts involves Wnt/BMP signaling and the chemokine sphingosine-1-phosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:20764-20769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piters, E., E. Boudin, and W. Van Hul. 2008. Wnt signaling: a win for bone. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473:112-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson, J. A., M. Chatterjee-Kishore, P. J. Yaworsky, D. M. Cullen, W. Zhao, C. Li, Y. Kharode, L. Sauter, P. Babij, E. L. Brown, A. A. Hill, M. P. Akhter, M. L. Johnson, R. R. Recker, B. S. Komm, and F. J. Bex. 2006. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a normal physiological response to mechanical loading in bone. J. Biol. Chem. 281:31720-31728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robling, A. G., P. J. Niziolek, L. A. Baldridge, K. W. Condon, M. R. Allen, I. Alam, S. M. Mantila, J. Gluhak-Heinrich, T. M. Bellido, S. E. Harris, and C. H. Turner. 2008. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J. Biol. Chem. 283:5866-5875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sawakami, K., A. G. Robling, M. Ai, N. D. Pitner, D. Liu, S. J. Warden, J. Li, P. Maye, D. W. Rowe, R. L. Duncan, M. L. Warman, and C. H. Turner. 2006. The Wnt co-receptor LRP5 is essential for skeletal mechanotransduction but not for the anabolic bone response to parathyroid hormone treatment. J. Biol. Chem. 281:23698-23711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah, S., A. Hecht, R. Pestell, and S. W. Byers. 2003. Trans-repression of beta-catenin activity by nuclear receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 278:48137-48145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tami, A. E., M. B. Schaffler, and M. L. Knothe Tate. 2003. Probing the tissue to subcellular level structure underlying bone's molecular sieving function. Biorheology 40:577-590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tatsumi, S., K. Ishii, N. Amizuka, M. Li, T. Kobayashi, K. Kohno, M. Ito, S. Takeshita, and K. Ikeda. 2007. Targeted ablation of osteocytes induces osteoporosis with defective mechanotransduction. Cell Metab. 5:464-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toyosawa, S., S. Shintani, T. Fujiwara, T. Ooshima, A. Sato, N. Ijuhin, and T. Komori. 2001. Dentin matrix protein 1 is predominantly expressed in chicken and rat osteocytes but not in osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16:2017-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vaananen, H. K., and T. Laitala-Leinonen. 2008. Osteoclast lineage and function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473:132-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]