Abstract

It has previously been established that muscles become active in response to deviations from a threshold (referent) position of the body or its segments, and that intentional motor actions result from central shifts in the referent position. We tested the hypothesis that corticospinal pathways are involved in threshold position control during intentional changes in the wrist position in humans. Subjects moved the wrist from an initial extended to a final flexed position (and vice versa). Passive wrist muscle forces were compensated with a torque motor such that wrist muscle activity was equalized at the two positions. It appeared that motoneuronal excitability tested by brief muscle stretches was also similar at these positions. Responses to mechanical perturbations before and after movement showed that the wrist threshold position was reset when voluntary changes in the joint angle were made. Although the excitability of motoneurons was similar at the two positions, the same transcranial magnetic stimulus (TMS) elicited a wrist extensor jerk in the extension position and a flexor jerk in the flexion position. Extensor motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) elicited by TMS at the wrist extension position were substantially bigger compared to those at the flexion position and vice versa for flexor MEPs. MEPs were substantially reduced when subjects fully relaxed wrist muscles and the wrist was held passively in each position. Results suggest that the corticospinal pathway, possibly with other descending pathways, participates in threshold position control, a process that pre-determines the spatial frame of reference in which the neuromuscular periphery is constrained to work. This control strategy would underlie not only intentional changes in the joint position, but also muscle relaxation. The notion that the motor cortex may control motor actions by shifting spatial frames of reference opens a new avenue in the analysis and understanding of brain function.

Introduction

Studies employing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in humans revealed that corticospinal facilitation of motoneurons is initiated prior to the onset of and is modulated during the muscle activation underlying intentional movements (Hoshiyama et al. 1997; MacKinnon & Rothwell, 2000; Schneider et al. 2004; Irlbacher et al. 2006). Opinions on the role of primary motor cortex (M1) in the specification of EMG patterns remain controversial, varying from the idea that M1 directly encodes these patterns (Irlbacher et al. 2006; Townsend et al. 2006; Jackson et al. 2007) to that M1 only indirectly influences them (Lemon et al. 1995; Graziano et al. 2002). Single-cell recordings also show that M1 activity may correlate with different kinematic and kinetic variables, such as the direction, velocity and position of the hand in peripersonal space as well as with the final arm posture (Caminiti et al. 1990; Kalaska et al. 1997; Aflalo & Graziano, 2006; Ganguly et al. 2009). M1 activity may also correlate with variables that reflect combined actions (‘synergies’) of body segments involved in the motor task (McKiernan et al. 1998; Park et al. 2001; Holdefer & Miller, 2002; Townsend et al. 2006; Jackson et al. 2007). In addition, in a study of tonic electrical stimulation of the pyramidal tract in decerebrated cats, Feldman and Orlovsky (1972) found that descending signals influence a specific neurophysiological variable – the threshold limb position at which appropriate muscles are silent but ready to be recruited when stretched.

The threshold position can be considered as the origin point of the spatial frame of reference (FR) for recruitment of motoneurons (Feldman & Levin, 1995; Feldman, 2009). By producing threshold position resetting, the brain may shift the spatial FR in which muscles are constrained to work without pre-determining how they should work (Feldman et al. 2007). Within the designated FR, muscles are activated or not depending on the gap between the actual and the threshold limb position as well as on the rate of change of this gap. This fine organization of muscle activation in the intact system vanishes after muscle deafferentation. Although deafferented patients regain the possibility of muscle activation, the absence of threshold position control results in numerous motor deficits, including the inability to stand or walk without assistance (e.g. Tunik et al. 2003; see also the web site by Jacques Paillard devoted to deafferentation: http://jacquespaillard.apinc.org/deafferented).

The present study addresses the controversy regarding the functional meaning of corticospinal excitability in the control of joint position with a specific focus on the question of whether or not the human motor cortex is involved in threshold position resetting for muscles spanning the wrist joint. To derive some testable predictions, consider the threshold position control in more detail. Initially revealed in humans (Asatrian & Fel’dman, 1965), the existence of threshold position control has been confirmed in decerebrated cats. Vestibulo-, reticulo-, rubro- and cortico-spinal pathways influencing α-motoneurons directly (mono-synaptically or pre-synaptically) or indirectly (via spinal interneurons or γ-motoneurons) can reset the threshold length of muscles spanning the ankle joint (Matthews, 1959; Feldman & Orlovsky, 1972; Nichols & Steeves, 1986; Capaday, 1995; Nichols & Ross, 2009). The threshold muscle length is velocity dependent (Feldman, 1986). It also depends on reflex reciprocal inhibition and other heterogenic reflexes (Feldman & Orlovsky, 1972; Nichols & Ross, 2009). The importance of threshold position control is emphasized by findings that stroke in adults and cerebral palsy in children limit the range of threshold regulation, resulting in sensorimotor deficits such as abnormal muscle co-activation, weakness, spasticity and impaired inter-joint coordination (Levin et al. 2000; Mihaltchev et al. 2005; Musampa et al. 2007).

The notion that descending systems have the capacity to set and shift the chosen spatial FR has many implications. In particular, it solves the classical posture–movement problem described in the seminal paper by Von Holst and Mittelstaedt (1950). They emphasized that each posture of the body or its segments is stabilized such that deviations from the posture are met with position and velocity-dependent resistance generated by various muscle, reflex and central posture-stabilizing mechanisms. In contrast, intentional movements away from previously stabilized postures do not evoke resistance from these mechanisms. To explain this difference, Von Holst and Mittelstaedt assumed that while sending motor commands to initiate intentional motion, the nervous system simultaneously uses an efference copy (i.e. a copy of motor commands to muscle) to suppress motion-evoked afferent feedback. The system thus cancels the afferent influences that would otherwise cause resistance to motion. This assumption conflicts with the finding that afferent feedback remains functional throughout intentional movements (Marsden et al. 1972, 1976; Matthews, 1986; Latash & Gottlieb, 1991; Feldman et al. 1995; Feldman, 2009). In addition, in isotonic movements, the EMG activity can return to its pre-movement level when the final posture is reached (Ostry & Feldman, 2003; Foisy & Feldman, 2006), implying that the copy of this activity (efference copy) also returns to its pre-movement level. As a consequence, the resistance resulting from position-dependent changes in the afferent signals is not compensated by efference copy. The resistance would thus drive the arm back to the initial position, a prediction of the efference copy theory that conflicts with experimental observations (Ostry & Feldman, 2003; Foisy & Feldman, 2006).

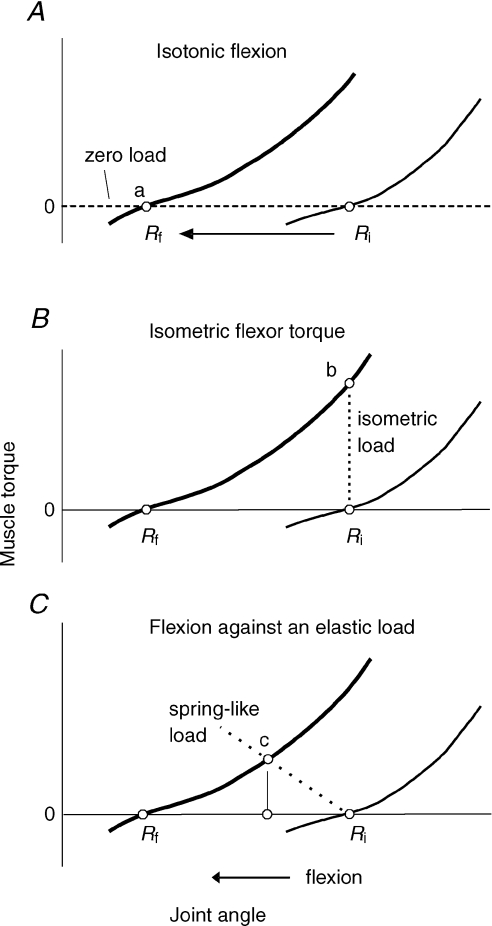

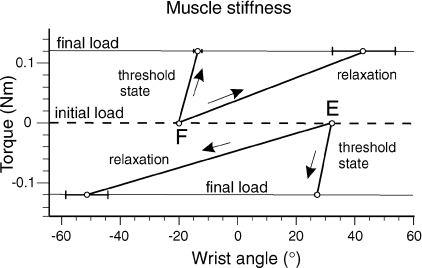

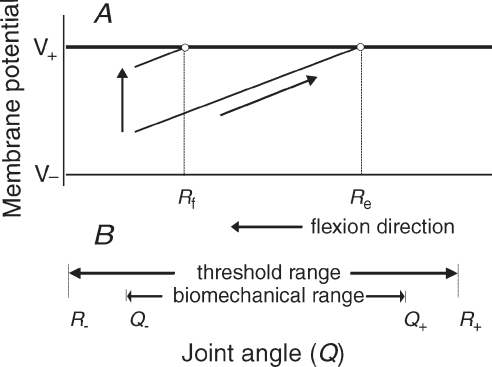

In the framework of threshold position control, the posture–movement problem is solved in the following way. Posture-stabilizing mechanisms are effective only when muscles are active. This occurs if the limb is deviated from a certain, threshold limb position (initial threshold joint angle, Ri in Fig. 1A; Feldman, 2009). Therefore, by shifting the threshold limb position (Ri→Rf (the final threshold joint angle)), the system resets (‘re-addresses’) posture-stabilizing mechanisms to a new posture. The initial posture appears as a deviation from the future posture and the same posture-stabilizing mechanisms that otherwise would resist the movement, now drive the limb to the new posture. Thus, by shifting the threshold position, the nervous system converts movement-resisting into movement-producing forces, which solves the posture–movement problem. Threshold position control may underlie not only isotonic movement but also other motor actions (e.g. isometric torque generation or movements against loads; Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1. Threshold position control.

The same shift in the threshold position of a body segment from Ri to Rf results in a change in the actual position of this segment in isotonic (zero load) condition (point a in A), in muscle torque in isometric condition (point b in B), or in both the position and muscle torque in intermediate condition (point c in C). Points a, b and c are equilibrium points defined as the points of intersection between the left continuous curve representing the final torque–angle characteristic (resulting from muscle activity regulated by proprioceptive feedback) and the dashed line (load torque–angle characteristic) in each panel.

In the present study, we first verified that threshold position resetting actually occurs during active changes in the wrist joint angle in humans. Then we tested the possibility that, in the same motor task, the corticospinal pathway, possibly together with other descending pathways, is involved in threshold position resetting and thus in the specification of a spatial FR in which the neuromuscular periphery is constrained to work. Note that if M1 is involved in threshold position resetting, then its steady state should change with transition to the new position. Specifically, to produce, say, a wrist flexion, the threshold wrist angle should be changed in the flexion direction (Fig. 1A). This can be done by increasing corticospinal facilitation of wrist flexor motoneurons while decreasing corticospinal facilitation of extensor motoneurons. The changed threshold position should be maintained after the movement offset, even if the activity and excitability of α-motoneurons at the new position return to those before the movement onset. We used a special technique to equalize the activity and excitability of α-motoneurons at pre- and post-movement positions.

Alternatively, if M1 is directly involved in the specification of EMG patterns, then corticospinal excitability should return to its pre-movement level if post-movement EMG activity of wrist muscles returns to its pre-movement level. In the present study, we used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to test these alternative possibilities. In addition, we addressed the question of whether or not M1 is involved in threshold position resetting in wrist muscles when they are fully relaxed (Wachholder & Altenbruger, 1927). In the context of threshold position control, full muscle relaxation is achieved by shifting the muscle activation threshold beyond the upper limit of the biomechanical muscle range (Levin et al. 2000), which reduces reflex responses to perturbations. Results were previously reported in abstract form (Burtet et al. 2007; Raptis et al. 2008, 2009).

Methods

Ethical approval

Nineteen healthy subjects participated in the study after signing an informed consent form approved by the institutional Ethics Committee (CRIR) in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Subjects

All subjects (8 males and 11 females, age 34.4 ± 11.3 years; range 25–69 years) were right-handed (Edinburgh's test). They were included in the study if they had no history of neurological diseases (e.g. epilepsy) or physical deficits of the upper extremities. Subjects were excluded from the study if they took drugs that could affect the cortical excitability (e.g. psychoactive drugs).

Apparatus

Subjects sat in a reclining dental chair that supported the head, neck and torso in a comfortable position with the right forearm placed on the table (the elbow angle was about 100 deg, horizontal shoulder abduction about 45 deg; Fig. 2A). The head and neck were additionally stabilized with a cervical collar. The hand and forearm were oriented horizontally in a neutral semi-supinated position. The hand with extended fingers was placed in a plastic splint attached to a light horizontal manipulandum. The hand was stabilized inside the splint with foam pads. The manipulandum could be rotated freely about a vertical axis aligned with the flexion–extension axis of the wrist joint. The subjects were instructed to make wrist flexion or extension without flexing the fingers or making wrist pronation or supination. They were thus instructed to minimize the involvement of degrees of freedom other than wrist flexion–extension. The motion of the forearm placed on a table was minimized by Velcro straps attached to the table. A torque motor (Parker iBE342G) connected to the axis of the manipulandum was used in experiments with nine subjects to produce brief stretches of wrist muscles to evaluate the excitability of motoneurons at two wrist positions (see below).

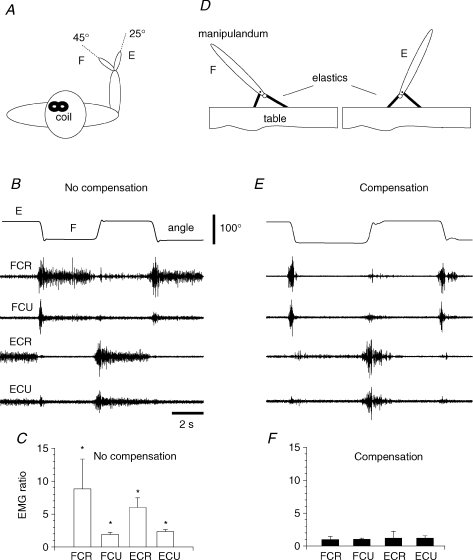

Figure 2. Equalizing EMG activity at two wrist angles.

A, subjects placed the hand in a vertical splint of a horizontal manipulandum and repeatedly flexed (F) and extended (E) the wrist. B and C, without compensation of the passive components of muscle forces, the tonic EMG activity of wrist flexors was higher when maintaining position F vs. E (F/E EMG ratio > 1). Similarly, extensors were more active at position E vs. F (E/F EMG ratio > 1, error bars are SDs). D–F, when passive wrist muscle forces were compensated by elastic, spring-like torques, the tonic EMG activity of each of 4 muscles substantially diminished and became position independent (EMG ratios ∼1.0). Asterisks indicate P < 0.001 for comparison of no-compensation with compensation ratios (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Representative data from one subject (S7).

Procedures

Equalizing tonic EMG activity and excitability of motoneurons at two wrist positions

Responses to TMS – motor evoked potentials (MEPs) – were recorded from two wrist flexors and two extensors using disc-shaped Ag–AgCl bipolar surface electrodes (1 cm diameter, 2–3 cm between the disc centres) placed on the bellies of the flexor carpi radialis (FCR), flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), extensor carpi radialis (ECR, long head) and extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU). EMG signals were amplified (Grass electromyograph), filtered (30–500 Hz) and sampled at a rate of 5 kHz.

MEPs could depend not only on the corticospinal signals transmitted to α-motoneurons either directly or indirectly, via spinal interneurons and γ-motoneurons, but also on the activity and excitability of α-motoneurons resulting, in particular, from proprioceptive influences on these motoneurons (Di Lazzaro et al. 1998; Todd et al. 2003). We tried to equalize the states of α-motoneurons at two wrist positions established by subjects (25–30 deg of wrist extension and 40–45 deg of wrist flexion measured relative to the neutral position of 0 deg). If this is done, the difference in MEPs at two wrist positions could reflect the difference in the corticospinal influences, rather than the difference in the excitability of α-motoneurons of the muscles from which the MEPs were recorded.

The tonic EMG activity of wrist muscles usually changes with the transition from one position to another (Fig. 2B), which might be related to the necessity to counteract the passive resistance of antagonist muscle fibres and connective tissues at these positions. With a deviation of the wrist from the neutral position, for example, in the flexion direction, passive wrist extensors are stretched such that tonic activation of flexors is necessary to hold the wrist at the flexion position and vice versa for extensors at the extension position. To exclude such position-related changes in the EMG activity, we mechanically compensated the passive muscle torques. Initially, before we added a torque motor to the manipulandum, we used two elastics (Fig. 2D) to produce position-dependent (spring-like) compensatory torques (in 7 subjects, S1–S7). One end of each elastic was attached underneath the manipulandum to a middle point located 2 cm from the axis of the manipulandum. With rotation of the manipulandum away from the neutral position, the moment arm of the force of one elastic increased whereas that of the other elastic decreased such that, at the extension wrist position (E in Fig. 2D), the net elastic torque assisted wrist extension and, at the flexion position (F in Fig. 2D), it assisted wrist flexion. By stretching or shortening the elastics, it was possible to adjust the assisting forces, individually for each subject so that they could minimize the tonic EMG activity at each position (compare Fig. 2E with B). In subsequent experiments with nine participants (S8–S16), the passive muscle torques were compensated by similar linear spring-like torques generated by a torque motor connected to the axis of the manipulandum (stiffness coefficient ∼0.003 Nm deg−1, adjusted individually for each subject). Note that the spring-like load, by itself, could not stabilize any position: in the absence of the hand in the splint, the manipulandum rapidly moved towards one or another extreme position determined by mechanical safety stoppers.

Subjects were instructed to minimize, using EMG feedback on the oscilloscope, co-contraction of wrist muscles at the initial and final positions. Trials in which the tonic EMG activity visually differed at the two wrist positions (1–2 trials per subject) were rejected. In off-line analysis, the residual tonic EMG activity (over 200 ms, 3 s after the movement offset) at each wrist position was measured as the mean value of EMG envelopes obtained after rectification and low-pass EMG filtering (0–15 Hz). It was expressed as a percentage of the EMG amplitude during maximal voluntary contraction, preliminarily measured individually for each subject. Subjects placed the hand in the splint of the manipulandum fastened in the neutral position. In response to a ‘go’ signal, they produced a maximal wrist flexor or, after about 10 min of rest, extensor torque for about 3 s. The maximal EMG was determined as the mean of the maximal values of EMG envelopes also obtained after EMG rectification and low-pass filtering, and taken from two repetitions of torque production in each direction. For all subjects, the minimized activity was in the range of 3–5% from the mean EMG maximum. For each subject, the background EMG level was stable and did not change significantly with position (see Results and Fig. 2E and F).

Although tonic EMG levels were equalized at a near-zero level at the two wrist positions, the responses to the same TMS pulse could still depend on the state of excitability of α-motoneurons at these positions. In humans, the excitability of α-motoneurons of wrist muscles is usually evaluated by H-reflexes elicited by monopolar electrical stimulation of the median nerve. A major pre-condition of using H-reflex for evaluation of motoneuronal excitability is a stable M-response (Misiaszek, 2003; Knikou, 2008). By trying this technique, we found that when subjects change the wrist position and contract wrist muscles, it is difficult to prevent mechanical displacements of the H-reflex stimulating electrode, resulting in artificial position-related changes in both H- and M-responses. In addition, to get a reliable H-response, muscles should maintain a contraction force higher than 5% of the MVC (Knikou, 2008), which would conflict with the instruction to minimize the pre- and post-movement EMG activity in our study. The H-reflex is considered as an electrical analog of the stretch responses (SRs; Knikou, 2008). Taking into account the limitations of the H-reflex technique in our study, we used instead a physiologically more natural method in which the excitability of motoneurons at the two wrist positions was evaluated by comparing short-latency SRs of wrist muscles to a brief stretch (0.35 Nm, 100 ms) elicited by the torque motor (Fig. 3) when passive muscle forces at these positions were compensated by the same motor. The subjects were instructed not to intervene voluntarily in response to perturbations. The pulse was applied in either flexion or extension direction (chosen randomly, 4 blocks of 10 trials alternating between the two positions and two directions of perturbations) every 5–10 s at each of the two wrist positions. An additional advantage of using stretches instead of H-reflexes was the possibility of evaluating the motoneuronal excitability of all four wrist muscles simultaneously, which is difficult to achieve with H-reflex stimulation. Some limitations of this technique are related to the anatomical difference in the muscle moment arms at the two positions. For the four muscles, the moment arms at the flexion position are about 20% higher than at the extension wrist position (16, 22, 26 and 22% for FCR, FCU, ECR and ECU, respectively; Gonzalez et al. 1997). At the two wrist positions, we used the same torque pulse that caused a similar angular displacement (about 25 deg) and peak velocity (about 300 deg s−1). Due to the differences in the moment arms, similar angular changes resulted in somewhat different stretches of muscles at these positions. To overcome this problem, the computed magnitudes of SRs of all muscles at the flexion position were downscaled by the percentage indicated above.

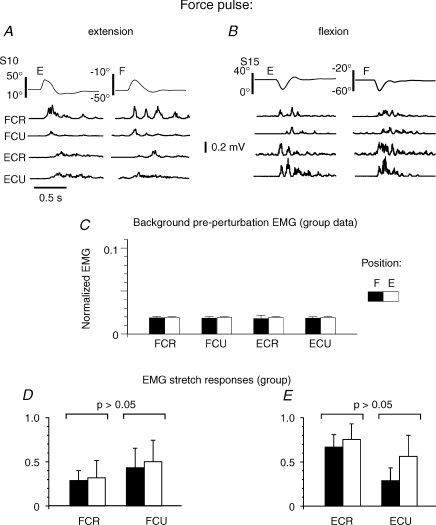

Figure 3. Testing motoneuronal excitability at the actively established positions E and F based on early EMG SRs to perturbations.

A, perturbations in the extension direction elicited a short-latency SR in wrist flexors (FCR, FCU) and a later response in extensors (ECR, ECU). B, perturbations in the flexion direction elicited a short-latency SR in stretched extensors and a later response in flexors. C, pre-perturbation EMG levels in position E and F (normalized to the maximal SR amplitude, individually for each muscle and subject) were similar (P > 0.05). D and E, earliest (30 ms duration) EMG SRs were also similar at the two positions.

We compared the amplitudes of SRs of each recorded muscle to perturbations in each direction at the two wrist positions during the first 30 ms after the SR onset (the initial part of the first EMG burst). This short window was chosen in order to minimize the possible influence of trans-cortical, triggered and intentional responses on the evaluations of motoneuronal excitability (Crago et al. 1976; Cheney & Fetz, 1984). These responses contribute to later EMG bursts elicited by wrist muscle stretching (Schuurmans et al. 2009).

Threshold wrist positions before and after intentional movement

Another method of evaluation of motoneuronal excitability in our study was based on the measurement of threshold wrist positions. A threshold wrist position is the position at which motoneurons of wrist muscles are silent but ready to be activated in response to a small central or reflex input. Physiologically, in the threshold state, the membrane potential of respective motoneurons is slightly below their electrical threshold (Pilon & Feldman, 2006). This state of motoneurons is quite different from their state during muscle relaxation when the membrane potentials of motoneurons are far below their electrical thresholds (see the next section).

The threshold wrist position (λ) prior to active wrist movement onset and after its offset was determined based on the SR onsets of wrist muscles at the two wrist positions using the following formulas. A muscle is activated if

| (1) |

where x is muscle length and λ* is its dynamic (velocity-dependent) threshold length (Feldman et al. 2007). To a first approximation,

| (2) |

where v is stretch velocity and μ is a time-dimensional parameter related to the dynamic sensitivity of muscle spindle afferents (Feldman, 1986).The threshold muscle length can be found by inserting eqn (2) into eqn (1) and taking the equality sign:

| (3) |

where x and v are the length and stretch velocity at which muscle activation is initiated. While using eqn (3), two delays should be taken into account. The first is the mechanical delay – the time required for the wrist to reach the dynamic threshold – and the second is the minimal reflex delay in signalling the x and v values by proprioceptive afferents to motoneurons. The minimal reflex delay (27.5 ms, see Results) was evaluated in our study based on the latency of EMG responses to stretches of pre-activated wrist muscles. It has been previously identified that parameter μ is within the range of 40–70 ms for a variety of muscles, such as those spanning the elbow, ankle, knee and hip joints (St-Onge et al. 1997; Gribble et al. 1998; Pilon & Feldman, 2006; Feldman et al. 2007). To evaluate the maximal deviation of the threshold from the actual position (see eqn (3)), we chose the maximal value from this range, i.e. 70 ms.

Conventionally, the wrist angle is defined as increasing with lengthening of wrist flexor muscles; the neutral wrist position resembles 0 deg, extension angles are positive and flexion angles are negative. Note that eqn (3) remains the same if instead of the length-dimensional variables, λ, x and v, respective angular variables are considered. Threshold joint angles (R) were determined for the initial and final wrist positions (Ri and Rf), separately for flexors and extensors.

Comparison of the threshold state with the state of muscle relaxation

Since the EMG activity of wrist muscles was equalized at a near-zero level at the two wrist positions, one could suggest that subjects simply relaxed muscles at each position after motion to it. The state of full muscle relaxation is characterized not only by the absence of EMG activity but also by the absence of stretch reflex responses to substantial and rapid changes in the joint angle (Fig. 4A). In terms of the λ model, the state of full muscle relaxation is achieved when the threshold muscle length exceeds the maximal muscle length in the biomechanical range (Feldman, 1986). In this case, the muscle cannot be activated within the entire biomechanical range unless it is stretched at a very high speed as in the case of the knee reflex.

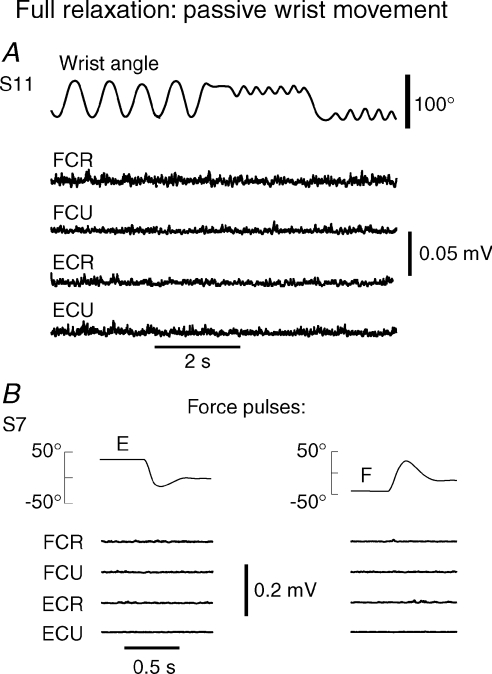

Figure 4. Muscle relaxation.

A, absence of EMG responses of fully relaxed wrist muscles to passive movements in the whole biomechanical joint range. B, in contrast to active wrist positioning (Fig. 3), no SR occurred in response to force pulses in relaxed muscles.

Using brief perturbations, the excitability of motoneurons was evaluated in eight subjects (S9–S16, 10 trials per position and direction of stretch) not only during active maintenance of the wrist positions but also when subjects relaxed wrist muscles and the required positions were established passively, by the experimenter. It appeared that subjects had difficulties in relaxing their wrist muscles and a short training was necessary to help them in this. To ensure profound relaxation, the experimenter first manually changed the position of the manipulandum in the whole biomechanical range of wrist angle while the subject looked at the EMG activity of the four muscles displayed on an oscilloscope and tried, as requested, to minimize the background EMG and responses to passive wrist displacements elicited by the experimenter (Fig. 4A). This training lasted approximately 5 min until EMG responses were excluded. After that, the experimenter moved the manipulandum and established the subject's wrist flexion or extension position. The experimenter stopped holding the manipulandum just before the perturbation pulse was delivered. Thus, we tested that no SR could be evoked in the wrist muscles in response to mechanical pulses similar to those employed in testing SR during active positioning (Fig. 4B).

In three subjects, we determined whether or not muscle stiffness (the slope of static torque–angle characteristic) associated with minimal EMG activity during active wrist positioning was different from that in the state of full muscle relaxation. This was done by comparing wrist displacements from the flexion and extension wrist positions elicited by a small constant torque (±0.12 Nm) generated by the torque motor in the two muscle states. Only one-directional perturbations were applied at each initial position (flexor torque at position E and extensor torque at position F) since perturbations in the other direction could bring the joint to the adjacent biomechanical limit of the wrist joint when muscles were relaxed. Subjects were instructed not to intervene voluntarily to perturbations.

TMS

TMS was produced by single pulses applied to a double-cone coil (70 mm outer diameter, 45 deg between the axes of each half of the coil; Magstim 200, UK) such that the magnetic fields created by the currents in the two halves were summated, resulting in a maximal stimulus at the intersection point (Rothwell et al. 1991; Hallett, 2007). TMS was delivered to the left M1. The TMS coil was placed on the surface of the scalp in such a way that the point of intersection between the two circles of the coil was approximately 2 cm anterior and 6 cm lateral to the vertex (Cz), according to the 10-20 system for EEG electrode placement (Jasper, 1958; Bonnard et al. 2003). From this position, the coil was moved (less than 0.5 cm) in the anterior–posterior and medial–lateral directions to a position where the threshold for eliciting MEPs in wrist flexors or extensors was minimal (Wassermann et al. 1992). MEPs were recorded electromyographically from two wrist flexors and two extensors (see above).

The optimal spot for TMS was defined as eliciting a MEP of more than 50 μV in the ECR (17 subjects) or FCR (2 subjects) at a minimal stimulation intensity (motor threshold, MT) in at least 5 out of 10 sequential trials when the wrist was in the neutral position specified by the subject while maintaining minimal EMG activity. The TMS intensity was chosen individually in each subject (range 1.2–1.4 MT for the group of subjects) to get a minimal supra-threshold stimulus that caused MEPs that not only clearly exceeded the background EMG level but also had a stable amplitude (about 200 μV) in five sequential trials in a flexor and an extensor wrist muscles. Since the sensitivity to TMS was different in different subjects, the most important characteristic of responses (relative stability) could not be ensured by a standard TMS intensity across all subjects.

Once the TMS intensity was determined, it was unchanged in each experiment. The optimal point was marked with a felt pen on the scalp. Four marks in total on the scalp and around the perimeter of the coil served as a visual reference to maintain the coil position throughout the experiment. To let the subjects rest, the coil was removed and re-placed from time to time but only between different experimental sessions.

Subjects were asked to establish a 25 deg wrist extension position. At this initial position, a single TMS pulse was delivered. After about 2–3 s, in response to a go signal (a beep), subjects moved the wrist, in a self-paced way, to a 45 deg flexion position (the total change in the joint angle was about 70 deg). In order to establish the required positions, subjects looked at a computer screen where their wrist angle was displayed on-line. Two to three seconds after the end of flexion movement, a second TMS pulse was delivered. This pulse was thus produced in a final static position, at the time when not only the transitional EMG bursts responsible for the wrist movement, but also the terminal agonist–antagonist co-activation, usually visible after the movement offset, receded to a minimum.

The relatively long intervals for TMS prior to the onset and after the offset of movement were chosen since we wanted to evaluate the difference in the corticospinal facilitation at two steady-state positions, while avoiding transitional changes in the MEPs resulting not only from corticospinal co-facilitation of agonist and antagonist muscles but also from temporary changes in the local excitability of α-motoneurons following the movement. Such long inter-stimulus intervals were also chosen to avoid significant intra-cortical interactions due to the previous TMS pulse (Rothwell et al. 1991). As verified by off-line analysis (see below in the Methods and Results), the chosen time for TMS (2–3 s after the movement offset) was sufficient for EMG signals and excitability of wrist motoneurons to recede to their pre-movement levels.

After 15 s, the trial was finished and subjects returned the wrist to the extension position to prepare for the next trial. In one block of 10–12 trials, the experimental testing started at the extension position (E → F sequence). In the second block (also 10–12 trials) testing started at the flexion position (F → E sequence). The order of these blocks as well as the order of other tests was randomized across subjects.

Changes in the corticospinal excitability could specifically be related to the established static wrist position or also reflect the history of reaching this position. For example, the same wrist position could be reached after wrist flexion or extension. To determine whether or not the corticospinal excitability is characteristic of the wrist position or/and history of its reaching, we compared MEPs at the same position (20 deg of flexion or 20 deg of extension) established after motion from a more flexed or extended position (±20 deg, 10 trials per direction of reaching and per position reached). This test was done in six subjects (S7, S9, S16–S19).

Changes in TMS responses following full muscle relaxation

After subjects fully relaxed wrist muscles (no SRs to rapid passive perturbations), the experimenter rotated the manipulandum at a moderate speed to bring the wrist to the flexion or extension position. A TMS pulse was delivered at each position (5–10 s between sequential pulses; 10 trials with a TMS pulse for each position). Directions of passive displacements towards each wrist position were randomized. We compared the MEPs recorded at the two wrist positions established actively by subjects with those when subjects fully relaxed wrist muscles. In experiments involving stretch responses, active and passive positioning were conducted separately in the same day. Experiments in which history-dependent effects were tested were conducted on a different day. The order of different experiments was randomized across subjects.

Data recording and analysis

Wrist position and velocity were measured with an optical encoder coupled to the shaft of the manipulandum. EMG activity, MEPs and wrist kinematics were recorded on-line, stored on a PC and analysed with LabView and Matlab softwares specifically adapted to this project.

To compare the tonic EMG levels prior to TMS at the initial and final positions, we used de-correlation techniques (Dong, 1996; Battaglia et al. 2007; Clancy et al. 2008). It takes into account that low-amplitude regular signals usually coming from external electrical sources such as power supplies can induce some undesirable correlation within and between EMG samples. De-correlation reduces autocorrelation within a signal, or cross-correlation between different samples of the signal while preserving their basic aspects. Although small, the external regular signals could produce noticeable peaks in the power spectrum of EMG. After eliminating these peaks, computer software produced an inverse Fourier transformation of the EMG power spectrum to obtain EMG samples that were less affected by these signals. The software then found the time interval after which the auto-correlation function for each of the two residual EMG samples fell below 10%. This interval was used as the new sampling interval for selecting 20 de-correlated EMG values from each of the two EMG samples. The duration of the original pre- and post-movement EMG samples preceding TMS to which this procedure was applied exceeded 60 ms. Based on the de-correlated values, the EMG samples were compared (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, the level of significance P < 0.05). Data were analysed trial by trial, individually for each subject.

For each of the four muscles in each trial we measured the MEP peak-to-peak amplitude, area and latency (the time between the TMS artefact and the first sign that the EMG deviates from the background activity) at the initial and final positions. In order to evaluate the difference in the MEPs at the two wrist positions, we compared MEP amplitudes at these positions, individually for each muscle and subject. For group averaging and group statistics, MEPs were normalized by dividing each muscle average response by the value of the maximal average MEP amplitude, individually for each subject, and then averaged across subjects.

Statistical analysis

The influence of position on the MEPs was assessed by calculating the mean and standard deviation (sd, represented by error bars in histograms) of the amplitudes, areas and latencies individually for each muscle. It appeared that MEP variances at the extension and flexion positions were different and that the values did not follow a normal distribution (Levene's test, Shapiro–Wilk test, P < 0.05). Therefore, we used non-parametric tests for statistical analyses. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to compare measures in the same subject (e.g. flexion vs. extension, active vs. relaxed state) while Wilcoxon matched-pairs test was used to study the significance of group results for the same conditions. After verification of the variance similarity and distribution normality of the EMG envelope amplitudes elicited after mechanical perturbations, dependent samples t tests were used to evaluate the difference between muscle reflex reactions in the group of subjects tested in the two wrist positions. For individual results, amplitudes of EMG (envelope) responses at the two wrist positions were compared for each perturbation direction using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The significance level of P < 0.05 was chosen in all tests.

Results

Threshold position resetting associated with active transition from one wrist position to another

When passive muscle torques at the two selected wrist positions were compensated, the EMG activity of all recorded wrist muscles at the initial and final positions was minimized. After transitional EMG bursts during the movement, the activity of each of the four wrist muscles in all subjects was reduced to its pre-movement level (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for two samples, P > 0.05; Fig. 2E and F), with the exception of one or, very rarely, two muscles in some trials (trials in which EMG levels were not equalized were excluded from the analysis of MEPs). In most cases for the group of subjects (95.1%), the EMG activity at the initial and final positions did not differ and was often only slightly above the background noise in EMG recordings (<5% from the EMG level during maximal voluntary contraction).

To test whether or not the reflex excitability of motoneurons was different at the two actively established wrist positions, we recorded EMG stretch responses (SRs) to torque pulses generated by the motor, in eight subjects. The pulses caused similar wrist deviations and velocities at these positions (Fig. 3A and B). Torque pulses in the extension direction initially evoked SRs in wrist flexors (FCU, FCR) and those in flexion direction evoked SRs in wrist extensors (ECU, ECR). All four muscles showed distinctive SRs (Fig. 3A and B) in both wrist positions. After these initial SRs, muscles usually generated several EMG bursts alternating between wrist flexors and extensors.

We compared latencies of EMG SRs at the two wrist positions measured from the beginning of perturbation. These latencies did not differ between positions for each of four muscles (P > 0.05) and were in the range of 51 ± 9 ms. The comparatively long latencies of SRs could result from the use of moderate stretches in terms of the magnitude and speed: SR latency tested by faster stretches of pre-activated muscles in our study was about 25–33 ms (mean 27.5 ms).

The amplitudes of short-latency SRs were evaluated by the maximal values of rectified EMG envelopes during the first 30 ms after EMG onsets. By focusing on the earliest component of SRs, we excluded long-latency responses that could be mediated by trans-cortical loops or resulted from intentional or triggered reactions to perturbations. To minimize the effect of the difference in the moment arms at the two wrist positions, the SRs at the flexion position were downscaled as described in the Methods.

Overall, for the group and all muscles (4 muscles in 8 subjects tested, 32 muscles in total), the amplitudes of short-latency SRs normalized to the maximum of EMG responses within the 30 ms windows (individually for each subject, and then averaged across subjects; Fig. 3D and E) did not differ at the two wrist positions (P= 0.64 for FCR, P= 0.26 for ECU, P= 0.68 for ECR and P= 0.06 for ECU, dependent samples t tests). Thus, in most cases, the excitability states of wrist motoneurons at the two positions were indistinguishable in terms of latency and magnitude of SRs, with some exceptions (included in the statistical analyses): in 1 of 4 muscles in three subjects, SRs were smaller at the position at which the length of this muscle was larger (e.g. in ECU when the wrist was flexed); in two other subjects, responses at the two positions tended to differ in 2 out of 4 muscles. In total, the individual statistical tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov) showed that SRs did not differ at the two positions in 78% of cases (25/32 muscles) and that, in most cases, not only the EMG levels but also the excitability of α-motoneurons of wrist muscles at the two actively established wrist positions were similar.

Even in those cases when muscles were silent most of the time at either of the two positions, they irregularly showed small intermittent EMG activity. This implies that motoneurons of these muscles were near their recruitment thresholds and were activated from time to time. To further verify this suggestion, we used SRs and eqn (3) to determine the recruitment threshold wrist positions before the onset and after the offset of intentional movements. We took into account that, because of reflex delay in the transmission of afferent signals to α-motoneurons and muscles, the values of position and velocity that were responsible for SRs actually occurred earlier than the measured latency of SRs (51 ± 9 ms). The transmission delay was measured as the latency of EMG responses to stretching of pre-activated muscles at the pre- and post-movement positions, in four subjects (see Methods). For all muscles and subjects, the transmission delay was in a narrow range of 25–33 ms (mean 27.5 ms). We then measured the angular displacement and velocity 27.5 ms before SR onsets at the pre- and post-movement positions to evaluate the respective initial and final threshold positions (Ri and Rf; see Methods). The difference between the threshold positions and the respective actual wrist positions for each of eight subjects did not exceed 2–7 deg, which is substantially less than the difference between the pre- and post-movement positions (about 70 deg). We thus confirmed that motoneurons of wrist muscles at the initial and final positions were near their recruitment thresholds and that the threshold wrist position (i.e. the position at which muscles were almost silent but ready to be activated when stretched) was reset when the wrist angle was changed, by a value that was close to the actual angular wrist displacement (about 70 deg).

Muscle relaxation

The threshold states in actively specified positions were substantially different from the state when wrist muscles were relaxed and the initial and final positions were established passively, by the experimenter. It appeared that most subjects had difficulties in relaxing wrist muscles to fully exclude SRs to perturbations. This was achieved after some training with the use of EMG feedback and random passive joint rotations in the whole biomechanical range. Subjects were instructed to exclude EMG responses to perturbations. After training, no significant EMG responses were observed during either passive wrist rotations by the experimenter or pulse perturbations elicited by the torque motor (Fig. 4). In this state, only 3–5 times stronger and more rapid perturbations could evoke SRs comparable to those during active wrist positioning.

The difference between the threshold and relaxation muscle states is also reflected in muscle stiffness (slope of torque–angle characteristic), evaluated by sudden application of small constant torques (±0.12 Nm) at the two wrist positions and by measuring the wrist displacement elicited by these torques (see Methods). During active positioning, muscle stiffness was 6–32 times higher than during relaxation at the same positions in the three subjects tested (P < 0.001; Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Muscle stiffness in threshold and relaxation states.

Although EMG activity was minimal at both wrist positions (F and E), wrist stiffness (the slope of torque–angle characteristic) during active wrist position control was substantially higher than during full muscle relaxation at the same positions but established passively.

Corticospinal excitability at different actively specified wrist positions

We compared the MEPs in each muscle only in those cases when the EMG activity of wrist muscles was equalized at the two positions. In each trial, a TMS pulse was produced before and after a voluntary wrist movement from extension to flexion (E → F movement) and vice versa (F → E movement).

The same TMS pulse regularly elicited a brief wrist flexor jerk at the flexion position and an extensor jerk at the extension position (Fig. 6). This behaviour was observed in 10 out of 16 subjects. In four subjects, only an extensor jerk was elicited at the extension position and in two subjects no mechanical response to TMS was observed at either position (even if MEPs were present). The reciprocal changes in motor responses to the same TMS pulse imply that the states of M1 at the two wrist positions were substantially different, even though the states of wrist motoneurons were similar. Note that this finding shows that changes in the M1 were strongly related to position but, like in the cases of correlations between variables, it does not imply causality (functional dependency) underlying this relationship: it could be observed if, for example, the M1 caused changes in wrist position or, vice versa, changes in wrist position could influence the M1 excitability (e.g. via trans-cortical loops; see Discussion).

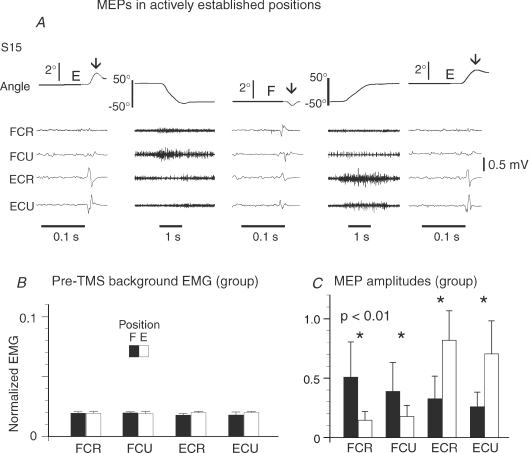

Figure 6. Typical mechanical and EMG responses to TMS at two static actively established positions, F and E, when the EMG activity and excitability of motoneurons of wrist muscles were equalized (as inFig. 3).

A, the left panel shows the wrist angle and MEPs for 4 wrist muscles at position E before movement. The next panel shows EMG activity during wrist movement from position E to position F at which a second TMS pulse was delivered. The last 2 panels show movement to position E and kinematic and EMG responses to TMS pulse at this position. The same TMS pulse elicited a flexor jerk at position F and an extensor jerk at position E (vertical arrows). Although the excitability of motoneurons was similar at the two positions, flexor MEPs at position F were substantially bigger than at position E and vice versa for extensor MEPs (reciprocal pattern). B, pre-TMS EMG levels in position E and F (normalized as in Fig. 3C) were similar (P > 0.05). C, group mean MEP amplitudes for 16 subjects.

Position-related changes in the corticospinal excitability were also evaluated by measuring the MEP peak-to-peak amplitude and area of the rectified MEPs in wrist extensors (ECR, ECU) and flexors (FCR, FCU) at the two wrist positions. The two methods yielded consistent results. A typical recording of wrist position, MEPs and EMG activity in a representative subject are shown in Fig. 6A for E → F → E movement. Two seconds before the movement onset (left segment), the EMG activity of wrist muscles was close to zero (background noise level). After transient EMG bursts, the wrist reached the flexion position, at which the EMG activity gradually returned to its pre-movement, near-zero level. Although the EMG activity of all muscles was minimal at either of the two positions, the MEP amplitude substantially changed with the transition from one position to another (for S15 in Fig. 6A, P < 0.01 for FCR, ECR, ECU and P < 0.1 for FCU, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test): MEPs of wrist flexors at the flexion position exceeded those at the extension position, and vice versa for extensor MEPs. The histogram for the group of subjects (Fig. 6C) shows similar position-related differences: MEPs for all muscles across the repeated trials were different at F and E positions (for FCR, P= 0.0008; FCU, P= 0.003; ECR, P= 0.0003; ECU, P= 0.0003, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test).

Reciprocal changes in flexor and extensor MEPs (extensor MEPs at E position exceeded those at F position and vice versa for flexor MEPs) were also observed in the remaining subjects although not always in all muscles. Specifically, in 6 out of 16 subjects, the position-related changes were significant for MEPs of all four muscles (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). In nine subjects, this was the case in 3 out of 4 muscles, while reciprocal changes in MEPs of the fourth muscle were at the border of significance in 3 of these 9 subjects. In one subject, reciprocal MEP changes were significant in only two (FCR, ECR) muscles (MEP changes in FCU were on the border of significance). Thus, except for few cases, the TMS responses were position-related, both for flexors and extensors. This result was obtained regardless of whether the passive muscle torques were compensated by elastics (7 subjects) or by the torque motor (9 subjects; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P > 0.05).

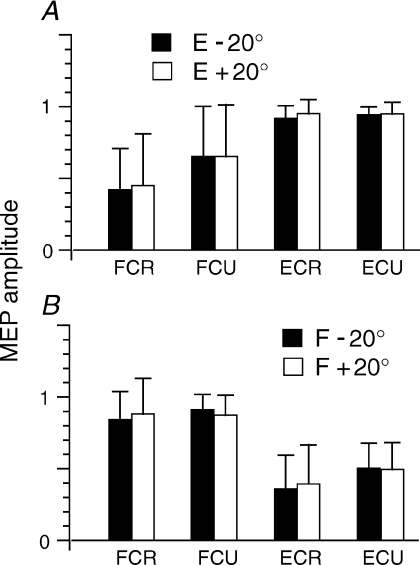

To determine whether or not corticospinal excitability at each of the two positions depended on the direction of movement towards these positions, we first compared MEPs at F and E positions when F → E or E → F movements were made. The movement direction effect was not significant for all four muscles (Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, FCR: P= 0.12, FCU: P= 0.12, ECR: P= 0.60, ECU: P= 0.92). In an additional experiment, subjects (n= 6) reached 20 deg of wrist extension from a more extended position (40 deg) or from the neutral position (0 deg). The corticospinal excitability (MEPs) at 20 deg of extension was independent of how this position was reached (P > 0.1 for all muscles, Fig. 7). A similar result was obtained for reaching 20 deg of wrist flexion after opposite-direction movements. These results imply that the corticospinal influences on wrist motoneurons at a given position were the same regardless of whether it was reached by previous active wrist extension or flexion. In other words, TMS responses reflected the corticospinal influences at each position, rather than the history of its reaching.

Figure 7. Corticospinal excitability reflects the state of M1 that is specific to each wrist position, regardless of how it was reached.

A, mean normalized MEP amplitudes at extension position (E = 20 deg) that was reached either by wrist flexion from position E +20 deg or by extension from position E –20 deg. B, similar test for a flexion position (F =−20 deg), after leaving a more extended or more flexed position. Error bars indicate SDs. Reaching direction had no effect on MEPs (P > 0.1; data for 6 subjects).

MEP latency was measured by identifying the first deflection of the EMG trace from the background level after the TMS artefact. In all cases of active positioning, the latency was in the range 14–24 ms (mean 18.8 ± 0.3 ms for all muscles and positions). The wrist position and movement direction had no effect on the latency of MEPs (P > 0.1, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test for the group).

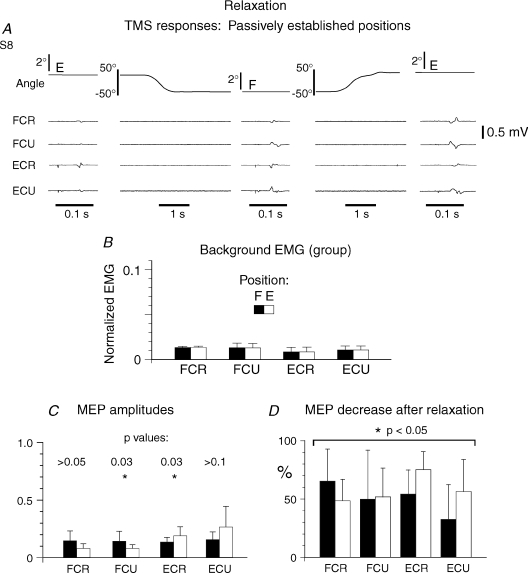

Corticospinal excitability before and after muscle relaxation

Results described in the previous sections showed that motoneurons of wrist muscles at the two actively established wrist positions were near their recruitment thresholds and were ready to be activated in response to external perturbations, which was not the case for motoneurons after muscle relaxation (Fig. 4). The state of M1 also changed with muscle relaxation. For example, the same TMS pulse that produced an wrist extensor jerk at the extension position but a flexor jerk at the flexion position established actively, became inefficient in eliciting a jerk after muscle relaxation at the same positions established passively (Fig. 8A), in all subjects. Muscle relaxation also resulted in a decrease in MEP amplitude and area at both positions in 93.1% of all cases, by a factor of 1.5–5.0 depending on the muscle and subject (P < 0.05 for group, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, Fig. 8C). The reciprocal pattern of changes in MEPs, characteristic of active positioning, became less systematic after muscle relaxation (only in 3 muscles in 2 out of the 9 subjects tested; in 1 or 2 muscles in 2 other subjects). In 5 out of 9 subjects, no position-related changes in the MEP amplitude were observed after relaxation (P > 0.05 for all muscles in these subjects, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; for the group, MEP amplitudes appeared position-related in 2 muscles out of 4; P= 0.03 for FCU and ECR, P > 0.05 for FCR and ECU, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test; Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. Responses to TMS (intensity as inFig. 6) at positions E and F established passively, by the experimenter, after muscle relaxation.

A, compared to active specifications of wrist positions (Fig. 6A), mechanical responses to TMS (jerks) were absent and MEPs substantially diminished. B, pre-TMS EMG levels in position E and F (normalized as in Fig. 3C) were similar (P > 0.05). C, group mean normalized MEP amplitudes. After relaxation, position-related changes in MEP amplitudes were observed only for 2 of 4 muscles. D, histogram for the group showing a decrease in MEP amplitudes for all muscles after relaxation compared to those in active positioning, at both wrist positions.

As in active wrist positioning, MEP latency after muscle relaxation was similar in the two wrist positions (P > 0.2) but mean latency significantly increased, by about 3 ms, from 18.8 ± 0.3 to 21.6 ± 0.5 ms (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test).

Discussion

Threshold position control by descending systems

It is known that MEPs might depend not only on corticospinal influences but also on motoneuronal excitability (Komori et al. 1992). To minimize the role of the latter factor in the evaluation of corticospinal excitability at two wrist positions, we compensated passive muscle torques and thus equalized EMG levels at these positions. It appeared that motoneuronal excitability was also equalized as shown by the similarity in the short (30 ms) initial components of muscle SRs at these positions. These components probably reflected not only mono-synaptic SRs of motoneurons but also pre- and poly-synaptic SRs of motoneurons mediated by spinal interneurons. Corticospinal influences on motoneurons could also be mediated by spinal interneurons of reflex loops (Porter, 1985; Lemon, 2008). However, this type of corticospinal influence could not play a major role in the evaluation of excitability of motoneurons based on the short initial components of SRs, otherwise these SR components would reflect the position-related changes found in MEPs. Instead, these components were similar for the two wrist positions. In the additional test of motoneuronal excitability, we found that, at both wrist positions, motoneurons of wrist muscles were near their activation thresholds. This test of motoneuronal excitability was based on detecting the earliest sign, rather than the magnitude of stretch-evoked EMG activity. In other words, this test relied on mono-synaptic SRs of motoneurons. The similarity of MEP latencies at the two positions also supports the assertion that motoneuronal excitability did not differ at these positions. Our data thus confirmed the assumption that motoneurons of wrist muscles at the initial and final positions were near their recruitment thresholds and that the threshold wrist position (i.e. the position at which muscles were almost silent but ready to be activated in response to perturbation) was reset when the wrist angle was actively changed. Our analysis thus complements previous findings of threshold position resetting in intentional single- and multi-joint movements in humans (St-Onge & Feldman, 2004; Archambault et al. 2005; Foisy & Feldman, 2006). Such resetting is fundamental in controlling movements without any concern for the posture–movement problem (see Introduction).

Our results showed that changes in corticospinal excitability accompanying threshold position resetting might be unrelated to and independent of EMG activity. They confirm the hypothesis that the corticospinal influences are involved in threshold position resetting, possibly in combinations with influences of other descending systems. One should also have in mind that the threshold wrist position may or may not coincide with the actual wrist position (see Fig. 1 and Results). These positions should be treated as different variables. The threshold position can be considered as a parameter that defines the origin (referent) point in the spatial FR in which wrist muscles start their recruitment or de-recruitment (see Introduction). In other words, by influencing the origin point, descending systems would specify a spatial FR in which the neuromuscular periphery is constrained to work whereas EMG activity emerges depending on the difference between the actual and the threshold position.

In a small number of cases (in 1 of 4 muscles in 9 out of 16 subjects), MEPs did not differ at the two wrist positions. This observation does not necessarily conflict with the suggestion that the corticospinal system is involved in threshold position control. It might reflect the complexity of neural interactions between wrist muscles (the ‘enslaving’ phenomenon; Zatsiorsky et al. 2000; Schieber & Santello, 2004). Despite the instruction to use only one, flexion–extension degree of freedom (DF), subjects could unintentionally involve other wrist DFs: although the hand was fixed in the splint of the manipulandum, subjects could exert small pressure on the splint walls in the pronation or supination direction. In these comparatively rare cases, corticospinal excitability and, as consequence, the resulting pattern of threshold position resetting could depend on how different DFs were combined (Ginanneschi et al. 2005, 2006).

Corticospinal pathways, possibly in combination with other descending pathways accomplish independent (‘open-loop’) control of motoneurons

While discussing our findings, one should have in mind that TMS applied over the primary motor cortex is known to influence motoneurons not only via the corticospinal but also via other corticofugal pathways. The most efficient TMS spot in the M1 for cortico-reticulo-spinal effects is different from the M1 spot we stimulated and requires much higher intensity of TMS compared to that used in our study (Gerloff et al. 1998; Ziemann et al. 1999). The latency of these effects also exceeds that of responses observed in our study. Therefore, it seems unlikely that, in our study, cortico-reticulo-spinal pathways played a major role in the position-related changes in MEPs. However, corticospinal neurons may send collaterals to neurons in rubro-, reticulo- and vestibulo-spinal descending systems influencing motoneurons (Keizer & Kuypers, 1984, 1989). Therefore, the changes in MEPs associated with wrist repositioning in our study might reflect in part the changes in the excitability of other descending systems.

Our findings revealed concomitant changes in the MEP and wrist position (Figs 6 and 7). One can say that these changes were correlated. As in other cases of observations of correlation between variables, the position-related MEP changes do not imply causality between the variables. Figure 1 shows that, in different external conditions, the same control signal (a change in the threshold joint angle, R) generated independently of position and force can correlate with one or both of these variables depending on external conditions. We suggest that corticospinal influences evaluated by MEPs were functionally independent of the actual wrist position but they became correlated with this position because of the isotonic condition of our experiments. Consider first alternative hypotheses. Corticospinal influences could functionally depend on wrist position if proprioceptive muscle length-dependent signals resulting from active wrist movement influenced motoneurons via spinal and/or trans-cortical reflex loops. According to this hypothesis, it is the neuromuscular periphery, rather than corticospinal and other descending influences, that would be responsible for correlation of MEPs with wrist position. Spinal reflexes per se, such as the stretch reflex and reciprocal Ia inhibition could not be responsible for the observable correlation, for two reasons. (1) The shortening of agonist muscles during wrist motion would result in a decrease in the reflex autogenic facilitation of agonist motoneurons following shortening of muscle spindles as well as from Ia inhibition of these motoneurons following lengthening of antagonist muscles. In contrast, our results showed that MEPs of shortening agonist muscles increased with the transition to the new position. (2) Such reflexes alone would change the excitability of motoneurons in a position-dependent way whereas our tests showed that excitability of motoneurons was the same at both positions.

It is also unlikely that MEPs became correlated with position because of trans-cortical reflexes. (1) If present (Wiesendanger, 1986; Macefield et al. 1996), such reflexes usually represent long-latent supplements to the spinal stretch reflex (Evarts & Fromm, 1981; Matthews, 1991), although the pattern of responses can be different in the case of strong perturbations (not used in the present study), resulting in involuntary discrete (‘triggered reactions’) or voluntary responses (Crago et al. 1976). Thus, like the spinal stretch-reflex (see above), stretch-reflex-like trans-cortical influences on the M1 could not be responsible for positional MEP relation. (2) To be consistent with observed MEP changes, the trans-cortical reflex facilitation of motoneurons should increase with muscle shortening, i.e. be in opposition to the stretch reflex. Such trans-cortical reflex would correspond, in engineering terms, to positive feedback that could destabilize wrist position control. In particular, once initiated, wrist flexion could be augmented by such feedback, eventually flexing the joint to its biomechanical limit.

Consider the hypothesis that motoneurons of wrist muscles were controlled by corticospinal influences independently of wrist position, i.e. independently of the changes in proprioceptive feedback resulting from the transition from one wrist position to another. In isotonic conditions, this facilitation could elicit a change in wrist position (Fig. 1A), resulting in correlation between these events. The finding that changes in corticospinal facilitation of agonist motoneurons start prior to the onset of muscle activation in rapid wrist movements (MacKinnon & Rothwell, 2000; Schneider et al. 2004; Irlbacher et al. 2006) is also a sign of independent initiation of corticospinal facilitation. We call this strategy ‘open-loop’ control. It does not imply an absolute independence on the periphery. Based on previous proprioceptive and other sensory information, the system may decide how to change corticospinal influences according to the task demand. However, once a decision is made, these influences are accomplished independently of peripheral feedback, unless this feedback or other sensory signals call on the necessity of movement correction.

Our study implies that previous observations of correlations of cortical activity with electromyographic and mechanical variables (e.g. Holdefer & Miller, 2002; Kurtzer et al. 2005; Townsend et al. 2006; Jackson et al. 2007; Griffin et al. 2009) may not be sufficient to conclude that M1 is involved in programming of these variables (see also Shah et al. 2004). An additional limitation of studies that found correlation of cortical activity with arm posture (e.g. Fortier et al. 1993; Kalaska et al. 1997) is that they leave unanswered the question what posture (actual or threshold) the cortex deals with. Future studies are also needed to test the possibility that, even during the dynamic phase of fast movement from one position to another, corticospinal facilitation remains predominantly independent of, although influences and therefore correlates with, the emerging EMG patterns and kinematic variables (cf. MacKinnon & Rothwell, 2000; Irlbacher et al. 2006; Kalaska, 2009). Our study demonstrates the disparity between corticospinal facilitation and tonic EMG patterns. Preliminary data showed that this might also be the case for the dynamic phase of rapid point-to-point movements (Raptis et al. 2009).

The motor cortex and muscle relaxation

Our findings suggest that muscles can appear inactive when subjects either relax wrist muscles or maintain a wrist posture by holding host motoneurons near their activation thresholds. These states of the neuromuscular system are substantially different: the former but not the latter case is associated with minimal, if not absent, reflex reactions to perturbation and low stiffness (see also Marsden et al. 1976). The absence of SRs at both wrist positions when subjects were relaxing implies that the excitability of α-motoneurons was suppressed by descending systems during muscle relaxation. This process was probably accompanied by a decrease in descending facilitation of γ-motoneurons, thus reducing the positional sensitivity of muscle spindle afferents (Lennestrand & Thoden, 1968). After achieving muscle relaxation, subjects could tolerate passive changes in the wrist angle by keeping descending influences unchanged. In this case, low sensitivity of muscle spindle afferent could be responsible for the low positional dependency of MEPs observed in our study.

Note that, unlike active positioning accomplished by reciprocal changes in the descending influences on agonist and antagonist motoneurons, relaxation involves parallel de-facilitation or inhibition of wrist agonist and antagonist motoneurons by descending systems. The motor cortex has been shown to have both types of projection on motoneurons (Lemon, 2008). However, a decrease in motoneuronal excitability associated with muscle relaxation could lead to a decrease in MEPs without a concomitant decrease in corticospinal facilitation. Therefore, although the participation of the corticospinal influences in muscle relaxation seems likely, our findings do not rule out the possibility that relaxation is accomplished by other descending systems.

In a previous study, changes in MEPs were analysed during passive muscle shortening and lengthening (Lewis et al. 2001), yielding ambiguous results – MEPs could increase, decrease or remain unchanged with muscle lengthening. The ambiguity might result from several factors. Subjects could produce different amounts of muscle relaxation resembling different sub-threshold states of motoneurons. They could also either be indifferent to or assist passive hand motion by maintaining the same or modulating corticospinal influences at a sub-threshold level. While not conflicting with these data, our findings do show that muscle relaxation, if ensured by appropriate tests, is associated with a substantial reduction of the amplitude and position-related modulation of MEPs, compared with the cases when wrist angle is actively specified by subjects.

Neurophysiological interpretations

Threshold position control implies that, due to proprioceptive feedback, electrochemical synaptic signals from the brain are transformed (‘decoded’) into a position-dimensional variable, R. In this way, actions become related to body space. The membrane of α-motoneurons may be the site of this transformation (Pilon et al. 2007; Feldman, 2009). Based on this assumption, one can explain basic findings in the present study (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Physiological origin of threshold position control and explanation of basic findings.

A, integration of position-dependent proprioceptive (lower diagonal line) and position-independent central inputs (vertical arrow) to a flexor α-motoneuron. The central input shifts the threshold position for motoneuronal recruitment (Re→Rf). B, full muscle relaxation in the whole biomechanical joint range [Q−, Q+] is achieved by minimizing the corticospinal facilitatory influences as well as those of other descending systems such that the threshold angle appears outside that range (R+ > Q+ for flexors, R− < Q− for extensors). Following the decrease in corticospinal facilitation and excitability of motoneurons, TMS responses in relaxed muscles are diminished compared to responses to TMS pulses applied during active wrist positioning.

When, say, a flexor muscle is quasi-statically stretched, position-dependent motoneuronal facilitation, predominantly from muscle spindle afferents, increases (Fig. 9A, low diagonal line) until the electrical threshold for motoneuronal recruitment is reached. This electrical threshold is reached at a certain muscle length or joint angle Re. In our experiments, this threshold angle could be close to the wrist actual extension position, Qe. In contrast, if descending systems elicit a position-independent increase in the membrane potential (vertical arrow), then the same muscle stretch results in muscle recruitment at a smaller threshold joint angle, Rf, that could be close to the actual flexion position (Qf). Note that the spatial threshold can be reset even if the electrical threshold of motoneurons (V+) remains constant. Changes in electrical motoneuronal threshold (Krawitz et al. 2001; Fedirchuk & Dai, 2004) may be an additional source of shifting the spatial threshold (see Pilon & Feldman, 2006). Thus, the amount of threshold position resetting is a physiological measure of independent descending influences on motoneurons. Therefore, by changing these influences (either directly or indirectly, via interneurons or γ-motoneurons), descending systems, including the corticospinal system, may participate in threshold position resetting (Re→Rf).

Figure 9A also illustrates how, physiologically, corticospinal influences could elicit resetting of the threshold position of a body segment, while maintaining the same motoneuronal activity and excitability at the pre- and post-movement positions. The basic idea is that, because of muscle shortening, the autogenic proprioceptive facilitation of flexor muscles would decrease with the transition from an extension to a flexion position. However, the independent corticospinal facilitation (partly mediated by γ-motoneurons) restores the state of flexor α-motoneurons to its pre-movement level, but at the new threshold position, Rf. Figure 9A also shows that descending facilitation of flexors at a flexion position should be greater than at an extension position, even though, at both positions, motoneurons are near their recruitment thresholds and therefore have the same excitability. A similar diagram can be plotted for extensor motoneurons by taking into account that the length of extensors decreases with the joint angle; corticospinal facilitation of extensors should be greater at the extension position, which explains the reciprocal changes in corticospinal facilitation with the change in wrist position. Figure 9B shows that by shifting muscle activation threshold outside the biomechanical range (to R+ for flexors and to R− for extensors, the system can exclude muscle activation in the whole biomechanical range of the joint (from Q− to Q+), thus accomplishing full muscle relaxation. Our data imply that the M1 may participate in threshold position resetting underlying not only intentional changes of posture but also muscle relaxation.

Figure 9A illustrates that threshold position resetting may result from sub-threshold changes in the state of motoneurons (Ghafouri & Feldman, 2001; Feldman, 2009). In other words, such resetting is a feedforward process in the sense that it starts prior to the EMG onset and can be accomplished before the end of the resulting motor action. Therefore, feedforward and predictive properties may result from natural physiological processes in the absence of any computations based on internal models of the system dynamics (Dubois, 2001; Turvey & Fonseca, 2009; Stepp & Turvey, 2010).

Conclusion

Our findings imply that the corticospinal system, possibly together with other descending systems, participates in a fundamental control process – threshold position resetting, thus pre-determining the spatial frame of reference in which the neuromuscular periphery is constrained to work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Trevor Drew and Mindy Levin for valuable comments on a draft of this paper and Michel Goyette and Valeri Goussev for help in programming and data analysis in this study. Supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Collaborative health research projects program (CHRP), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, Fonds de recherche sur la nature et les technologies and Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (Canada).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DF

degree of freedom

- E

extension position

- ECR

extensor carpi radialis

- ECU

extensor carpi ulnaris

- F

flexion position

- FCR

flexor carpi radialis

- FCU

flexor carpi ulnaris

- FR

frame of reference

- M1

primary motor cortex

- MEP

motor-evoked potential

- MT

motor threshold

- Ri and Rf

initial and final threshold joint angles

- SR

stretch response

- TMS

transcranial magnetic stimulation

Author contributions

All the experiments were performed in the Motor Control Laboratory at the Institute of Rehabilitation of Montreal (University of Montreal). All authors contributed to the following parts: (1) Conception and design of the experiments; (2) Collection, analysis and interpretation of data; (3) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final submitted version.

References

- Aflalo TN, Graziano MS. Partial tuning of motor cortex neurons to final posture in a free-moving paradigm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2909–2914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511139103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambault PS, Mihaltchev P, Levin MF, Feldman AG. Basic elements of arm postural control analyzed by unloading. Exp Brain Res. 2005;164:225–241. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asatrian DG, Fel’dman AG. Functional tuning of the nervous system with control of movement or maintenance of a steady posture – I. Mechanographic analysis of the work of the joint during the performance of a postural task. Biophysics. 1965;10:925–935. Engl transl of Biofizika 10, 837–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia D, Brunel N, Hansel D. Temporal decorrelation of collective oscillations in neural networks with local inhibition and long-range excitation. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99:238106. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.238106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnard M, Camus M, de Graaf J, Pailhous J. Direct evidence for a binding between cognitive and motor functions in humans: a TMS study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15:1207–1216. doi: 10.1162/089892903322598157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtet L, Raptis H, Tunik E, Latash ML, Forget R, Feldman AG. Threshold control of wrist movements revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex (abstract) 2007. Congress of Journée scientifique du CRIR (Montreal)

- Caminiti R, Johnson PB, Urbano A. Making arm movements within different parts of space: dynamic aspects in the primate motor cortex. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2039–2058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02039.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C. The effects of baclofen on the stretch reflex parameters of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1995;104:287–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00242014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney PD, Fetz EE. Corticomotoneuronal cells contribute to long-latency stretch reflexes in the rhesus monkey. J Physiol. 1984;349:249–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy EA, Bertolina MV, Merletti R, Farina D. Time- and frequency-domain monitoring of the myoelectric signal during a long-duration, cyclic, force-varying, fatiguing hand-grip task. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crago PE, Houk JC, Hasan Z. Regulatory actions of human stretch reflex. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:925–935. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.5.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Restuccia D, Oliviero A, Profice P, Ferrara L, Insola A, Mazzone P, Tonali P, Rothwell JC. Effects of voluntary contraction on descending volleys evoked by transcranial stimulation in conscious humans. J Physiol. 1998;508:625–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.625bq.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D. Associative decorrelation dynamics in visual cortex. In: Sirosh J, Miikkulainen R, Choe Y, editors. Lateral Interactions in the Cortex: Structure and Function. Austin, TX: UTCS Neural Networks Research Group; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois DM. Computing anticipatory systems. AIP Conf Proceedings. 2001;573(XI):706. [Google Scholar]

- Evarts EV, Fromm C. Transcortical reflexes and servo control of movement. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1981;59:757–775. doi: 10.1139/y81-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedirchuk B, Dai Y. Monoamines increase the excitability of spinal neurones in the neonatal rat by hyperpolarizing the threshold for action potential production. J Physiol. 2004;557:355–361. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]