Abstract

Aged non-human primates are a valuable model for gaining insight into mechanisms underlying neural decline with aging and during the course of neurodegenerative disorders. Behavioral studies are a valuable component of aged primate models, but are difficult to perform, time consuming, and often of uncertain relevance to human cognitive measures. We now report findings from an automated cognitive test battery in aged primates using equipment that is identical, and tasks that are similar, to those employed in human aging and Alzheimer’s disease studies. Young (7.1 ± 0.8 years) and aged (23.0 ± 0.5 years) rhesus monkeys underwent testing on a modified version of the Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB), examining cognitive performance on separate tasks that sample features of visuospatial learning, spatial working memory, discrimination learning, and skilled motor performance. We find selective cognitive impairments among aged subjects in visuospatial learning and spatial working memory, but not in delayed recall of previously learned discriminations. Aged monkeys also exhibit slower speed in skilled motor function. Thus, aged monkeys behaviorally characterized on a battery of automated tests reveal patterns of age-related cognitive impairment that mirror in quality and severity those of aged humans, and differ fundamentally from more severe patterns of deficits observed in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Keywords: aging, monkeys, non-human primate, cognition, cognitive testing, CANTAB, working memory, frontal lobe, temporal lobe, hippocampus

1. Introduction

Decline in cognitive function occurs with normal aging. In humans, age-related cognitive decline is reflected in tasks that assess learning and memory, executive function, attention, and processing speed (De Luca et al., 2003; Kausler, 1994; Sliwinski and Buschke, 1999). For example, episodic or working memory is affected in normal aging, a function attributable to frontal lobe systems (Nilsson, 2003), whereas other memory systems are relatively spared, including many of those associated with temporal-hippocampal systems (De Luca et al., 2003; Hanninen et al., 1997; Kausler, 1994). Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), result in cognitive impairments that exceed in degree and functional anatomy those observed in normal aging, including changes in visuospatial learning, attention, and working memory (Blackwell et al., 2004; Fowler et al., 2002; Weaver Cargin et al., 2006). The more global sets of deficits in AD therefore point to dysfunction of broad cortical regions, including both frontal and temporal-hippocampal systems. Cross-species studies of age-related cognitive decline can potentially yield insight into systems and underlying mechanisms that distinguish normal age-related changes from pathological memory decline in such disorders as AD.

Various neuropsychological tests have been developed to examine specific aspects of cognitive function in both humans and non-human primates. Batteries of tasks provide an opportunity to test a wide spectrum of cognitive abilities, and emerging patterns of deficits can thereby provide insight regarding neural systems that are impaired with normal aging or in neurodegenerative disease. One battery of cognitive tests, CANTAB (the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery), was designed to adapt paradigms developed in animal models for use in humans, using computer-based testing (Owen et al., 1996; Owen et al., 1991; Robbins et al., 1998; Sahakian and Owen, 1992). Computer-based batteries provide automated testing that frees the experimenter from performing one-on-one testing, offers a neutral setting in which to conduct testing, and potentially avoids confounds associated with operator-subject interactions or bias. The present study used a modified version of the CANTAB set of tasks to measure cognitive function in aged monkeys, thereby providing an opportunity to compare patterns of age-related deficits in monkeys and humans tested using similar cognitive test paradigms and identical testing equipment. While previous studies have successfully used automated cognitive testing in non-human aged primates (e.g., (Bartus et al., 1978; Buccafusco et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2005; Voytko, 1993), the CANTAB set of tasks utilizes the same testing hardware and comparable software across species, potentially supporting more direct comparisons of age-related deficits across species. Similarities of cognitive decline in aged monkeys and humans would demonstrate cross-species effects of aging and substantiate the potential relevance and importance of non-human primate studies in understanding neuronal substrates underlying human aging.

Adult and aged rhesus monkeys were tested using CANTAB on a variety of tasks assessing working memory, visuospatial learning, discrimination learning/retention, and skilled motor performance (Taffe et al., 2004; Weed et al., 1999). We now report selective deficits in tasks assessing working memory and learning in aged monkeys, with relative preservation of discrimination learning and retention; these patterns of dysfunction with aging mirror reports in humans tested under similar conditions.

2. Methods

Subjects

21 rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) served as experimental subjects. Young adult monkeys ranged in age from 4.5 to 9.7 years (7.1 ± 0.8 years; N=6; 3 males, 3 females) at the start of behavioral testing, while aged monkeys ranged in age from 20.4 to 27.4 years old (23.0 ± 0.5 years; N=15, 11 males, 4 females; Table 1). Subsets of monkeys were tested on each task, as indicated below and in Table 1. Animals were housed at the California Regional Primate Research Center, and animal care conformed to National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines regarding the health, safety, and comfort of animals. Testing sessions were conducted in the morning.

Table 1.

Experimental Subjects

| Subject # | Age | Gender | Group | Visuosp* | SWM† | Discr/Memπ | Motor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.4 | Male | Young | X | X | X | |

| 2 | 5.0 | Male | Young | X | X | ||

| 3 | 7.4 | Female | Young | X | X | ||

| 4 | 7.6 | Female | Young | X | X | X | X |

| 5 | 8.8 | Female | Young | X | X | X | |

| 6 | 9.7 | Male | Young | X | X | X | |

| 7 | 20.4 | Male | Aged | X | |||

| 8 | 20.4 | Male | Aged | X | |||

| 9 | 21.5 | Male | Aged | X | X | ||

| 10 | 21.6 | Male | Aged | X | X | ||

| 11 | 21.6 | Male | Aged | X | X | ||

| 12 | 21.9 | Male | Aged | X | X | ||

| 13 | 22.3 | Female | Aged | X | X | ||

| 14 | 22.4 | Male | Aged | X | |||

| 15 | 22.8 | Male | Aged | X | X | X | |

| 16 | 23.1 | Male | Aged | X | X | ||

| 17 | 23.7 | Female | Aged | X | X | X | |

| 18 | 24.1 | Male | Aged | X | X | X | |

| 19 | 24.9 | Male | Aged | X | X | X | |

| 20 | 26.5 | Female | Aged | X | X | X | |

| 21 | 27.4 | Female | Aged | X |

Visuospatial task

Spatial Working Memory

Shape Discrimination and Memory Retention

Apparatus

Monkeys were tested in their home cages using a touch-sensitive computer screen controlled by a Pentium type computer running CANTAB software (Cambridge Cognition, Cambridge, UK) designed for use with nonhuman primates. A pellet dispenser (Med Associates Inc.) provided a food reward (190 mg flavored pellets; P.J. Noyes Co., Lancaster, NH) to reinforce participation and correct responses. Food restriction was introduced only when subjects required additional reinforcement, to no more than 10% decline in weight from baseline.

Behavioral Tests

The battery of tests used in the present study has been previously described for young adult rhesus monkeys (Taffe et al., 2004; Weed et al., 1999), with several modifications as described in greater detail below. In particular, some tasks were simplified to accommodate impaired learning in aged monkeys that was identified in preceding pilot studies. For example, testing was not performed with a full test battery of “intradimensional – extradimensional set shifts” on the discrimination task, a departure from traditional testing in young monkeys (Taffe et al., 2004; Weed et al., 1999). All subjects were first trained to touch a stimulus on the computer screen to obtain a food pellet reward. Following acquisition of this procedure, subjects were trained on four tasks.

Visuospatial Learning

5 young (6.6 ± 0.8 years) and 9 aged (23.3 ±0.6 years) monkeys (Table 1) were tested on this working memory task that is dependent on both frontal cortical and temporal-hippocampal systems (Gould et al., 2006; Gould et al., 2003; Meltzer and Constable, 2005). The visuospatial learning task requires the subject to learn to associate a cue with a specific location on the computer screen, as previously described (Fig. 1)(Taffe et al., 2004). The subject is shown a stimulus (e.g., red square) in one of four possible locations on the screen (top, bottom, left or right), and must recall the correct location of the stimulus among several choices after a brief delay (1 s). For initial training on the task, the monkey is required to learn the location of only one stimulus. First, the monkey is shown the stimulus during the “Sample” phase. After making a response (by touching the stimulus on the screen), the screen becomes blank for 1 s and the sample stimulus is presented again in the same location (“Choice” phase). The monkey is rewarded for touching the stimulus again; this simple version of the task facilitates responding during initial training and does not test memory. The complexity of the task is then increased to assess visuospatial learning by presenting two choices after the 1 s delay (Fig. 1A); only choice of the stimulus in the original location is rewarded and scored as correct. Complexity is subsequently further increased by presenting the stimulus in 3 locations in the Choice phase (Fig. 1B). Selecting a stimulus in an incorrect location is scored as an error, and failure to touch the screen within 30 s is scored as a “miss”; both types of responses produce a 5-s blank “punishment delay” screen. A correct response presents a new trial after only a 1-s blank screen. Novel stimuli and locations are presented in each trial.

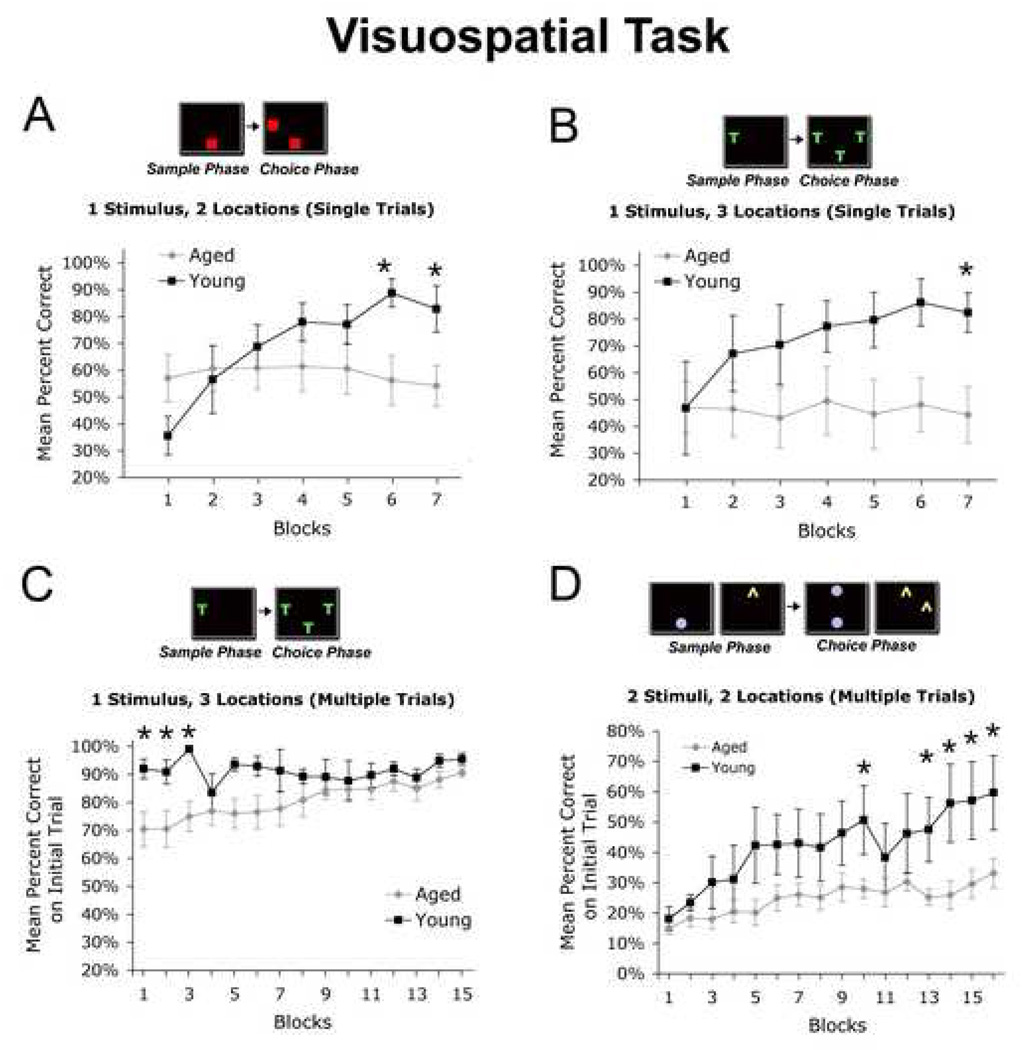

Figure 1. Visuospatial Learning.

In this visuospatial learning task, monkeys learn to associate a stimulus with a specific location. (A) In the 1 Stimulus / 2 Location version of the task, the monkey is shown a stimulus in one location during the sample phase (red square, bottom edge), and after a brief delay, the monkey learns to chose the stimulus in the same location among 2 possible options (Choice phase). (B) Similarly, in the 1 Stimulus / 3 Location version of the task, the monkey is shown a stimulus in one location, and then learns to select the stimulus in the same location among 3 options in the Choice phase. Young monkeys (N=4) showed significant improvement in performance when tested with (A) 2 choices and (B) 3 choices over the initial 7 blocks of training (post-hoc repeated measures ANOVA, p<0.001 both tasks). In contrast, aged monkeys (N=7) showed no improvement in performance over successive blocks tested under either condition, and differed significantly from young monkeys in overall performance over time (Age x Block Interaction, p<0.001; *p<0.05 indicates significant difference on post-hoc analysis during individual sessions). (C) Monkeys were then tested using repeated trials to allow correction of errors, and aged monkeys were now able to learn the task over successive trials (Age x Block Interaction, p<0.05). Graph shows mean percent correct choices on first of 5 trials. While the performance of aged monkeys differed from young monkeys initially in the Multiple Trial format (*, Blocks 1–3, p<0.05 post-hoc Fischer’s), performance over subsequent blocks improved to levels of young subjects. (D) When task complexity was further increased by presenting two Stimuli over successive Sample and Choice phases, aged subjects demonstrated significant impairment in performance over blocks compared to young monkeys (Age x Block interaction, p<0.05). As in panel C, graph shows mean percent correct choices on first of 5 trials. Nonetheless, the performance of both young (p<0.05) and aged (p<0.05) monkeys significantly improved over trial blocks. Significant differences in performance comparing aged and young monkeys during specific blocks are indicated by * (p<0.05, post-hoc Fischer’s).

Testing then proceeds to a “Correction” version of the task in which one stimulus is presented in the Sample phase, followed by 3 stimuli in the Choice phase; as above, the monkey must choose the stimulus in its original location. However, the same stimuli and locations are repeated over up to 5 trials to correct the subjects’ performance in the event they have made errors, as was commonly the case with aged subjects (Fig. 1C). In this way, the monkey’s performance is shaped toward improving accuracy on the task.

In a more demanding form of this task, difficultly is increased by providing a stimulus in the first Sample phase, then providing a different stimulus in a second Sample phase (Fig. 1D). In the Choice phase, the monkey is required to select the stimulus as it was located in the first Sample phase, and then to select the second stimulus as it was located in second Sample phase (Fig. 1D); both stimuli must be correctly selected to pass the trial. The stimulus-location pairings (Sample and Choice phases) are repeated up to 5 times to facilitate learning.

For single-trial training on this task, each test session consisted of 5 trials of the single stimulus in one location, 20 trials of the single stimulus in two Choice locations, and 20 trials of the single stimulus in three Choice locations; approximately 20 test sessions were performed. For multiple-trial (“Correction”) training, each test session consisted of 5 different sets of the single stimulus in two choice locations, 5 sets of the single stimulus in the three choice locations, and 30 sets of 2-sample stimuli in two choice locations; approximately 40 sessions were performed.

Spatial Working Memory

4 young (7.6 ± 1.1 years) and 5 aged (24.0 ± 0.8 years) monkeys (Table 1) were tested on the spatial working memory task, referred to in the CANTAB literature as the “Self-Ordered Spatial Search.” The task is thought to assess frontal lobe working memory functions (Pantelis et al., 1997; Robbins et al., 1998). Subjects are shown a set of 2 or 3 boxes in different locations on the computer screen (Fig. 2A,B). At the onset of the trial, the monkey must touch one box. After the first touch, the selected box briefly (0.1 s) changes color, the screen becomes blank for a short period (0.25 – 2 s), and the same set of boxes are presented again (Fig. 2A,B). The monkey must now touch each remaining box in any sequence, without returning to a box previously touched, to receive a food reward (hence, “self-ordered”), a task bearing similarity to, for example, the radial arm maze in rodents (Becker et al., 1980; Olton and Samuelson, 1976) and primates (Rapp et al., 1997). The trial ends when: 1) all boxes have been touched once (“correct” trial), 2) any box is touched twice (“incorrect” trial), or 3) there is no response after 30 seconds (“miss” trial). Completion of a correct trial results in a 5-s inter-trial interval before the beginning of the next trial; the completion of an incorrect trial results in a tone (0.2 s) and a 9-s inter-trial interval. Failure to respond to the screen within 30 s results in a tone and a 9-s delay before starting the next trial. The initial training on this task begins with 2 boxes, a short screen blank (0.25 s), and reinforcement at the end of a correct trial. With improvement in performance, the task difficulty is increased by adding 3-box trials, and by implementing longer delays (up to 2 s). During initial training on this task, subjects received 20 trials with the 1-box condition and 20 trials with the 2-box condition using a 0.25 s delay, over an average of 25 sessions. In the next stage of training, subjects received 10 trials with the 1-box condition, 20 trials with the 2-box condition, and 20 trials with the 3-box condition using a 0.25 s delay on each test session, over approximately 30 sessions. Finally, subjects were tested on the same schedule with longer delays of 0.5 s, 1 s, and 2 s over approximately 15 additional test sessions.

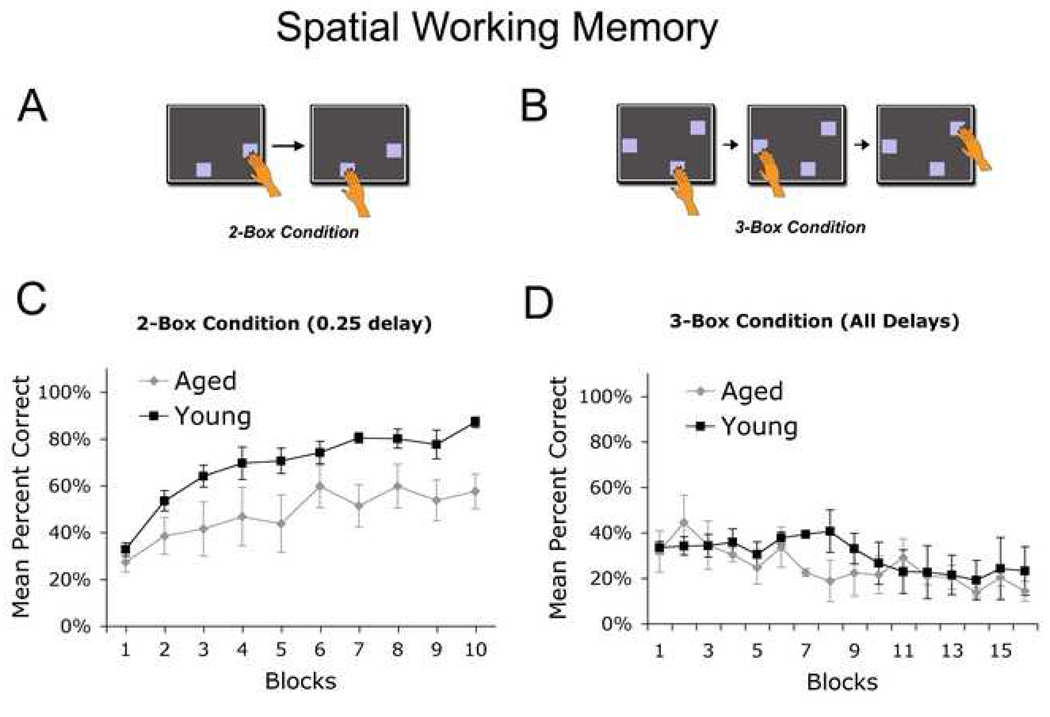

Figure 2. Spatial Working Memory.

(A) In the self-ordered spatial working memory paradigm, the monkey is given a screen with two squares in different locations on the screen (2-box condition). The monkey learns to touch one square on the first screen and the other square on the next screen for a food reward; if the monkey touches the box in the same location, an error is recorded for the trial. (B) In the more difficult 3-box condition, the monkey is given a screen with three squares and must learn to touch one square on the first screen, a different square on the second screen, and the last square on the third screen in any order the subject decides (self-ordered), but without touching a previously presented object. (C) In the simple 2-box condition, both young (N=3) and aged (N=5) monkeys exhibited improved performance over successive trials (ANOVA: Block Main Effect, p<0.02). Overall, however, aged monkeys did not perform as well as young subjects (ANOVA: Age Main Effect; p<0.05). (D) In the more complex 3-box condition of the task, neither aged nor young monkeys were able to learn (ANOVA, non-significant).

Shape Discrimination and Memory Retention

4 young (7.4 ± 1.0 years) and 10 aged (22.4 ± 0.6 years) monkeys (Table 1) were tested on a shape discrimination task (adapted from the “Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift” test of CANTAB software) incorporating a new retention component to assess delayed memory. This type of stimulus-reward associative learning task is thought to utilize temporal-hippocampal substrates (Luciana and Nelson, 1998; Moss et al., 1981). In the shape discrimination task, subjects learn to discriminate between two target shapes; the target shapes are overlapped by thin white lines (distracting stimuli) which must be ignored (Fig. 3A). The monkey learns that one of the solid shapes is associated with a reward (two food pellets), while ignoring the distracting linear stimuli. The subject is trained on each discrimination pair to criterion performance of 90% success, defined as choice of the reinforced shape correctly in 18 out of 20 consecutive trials. For example, the subject may fail to reach criterion in the first 70 trials in a given test session, but if the subject then chooses the correct test stimulus in 18 of the next 20 trials, criterion performance is achieved, and the subject continues to the next step of the task. Following a correct choice, an intertrial interval of 5 s is given before the next screen is presented; following an incorrect choice, there is a tone (0.2 s) and a 9 s intertrial interval. Each testing session consists of an acquisition component in which the subject must learn to the correctly discriminate the first pair of shapes and then a second pair of different shapes to 90% accuracy (Fig. 3B). A subject is provided up to 240 trials to complete both pair discriminations in the acquisition component. If the subject successfully completes the first two discrimination pairs (Stage 1), they are re-tested 1 hr or 24 hr later in the retention component of the task (Fig. 3B) (Stage 2). In retention testing, the subject first learns to discriminate a 3rd, novel pair of shapes to criterion performance (90% accuracy). The subject is then re-tested on a discrimination pair learned in the acquisition component of this task, to test retention of the previously learned shapes. Novel sets of shapes to discriminate are provided on each test block. Criterion performance consists of selection of the previously reinforced stimulus in 90% of trials. The subject is provided up to 240 trials to reach criterion performance on both pairs in the retention component of this task.

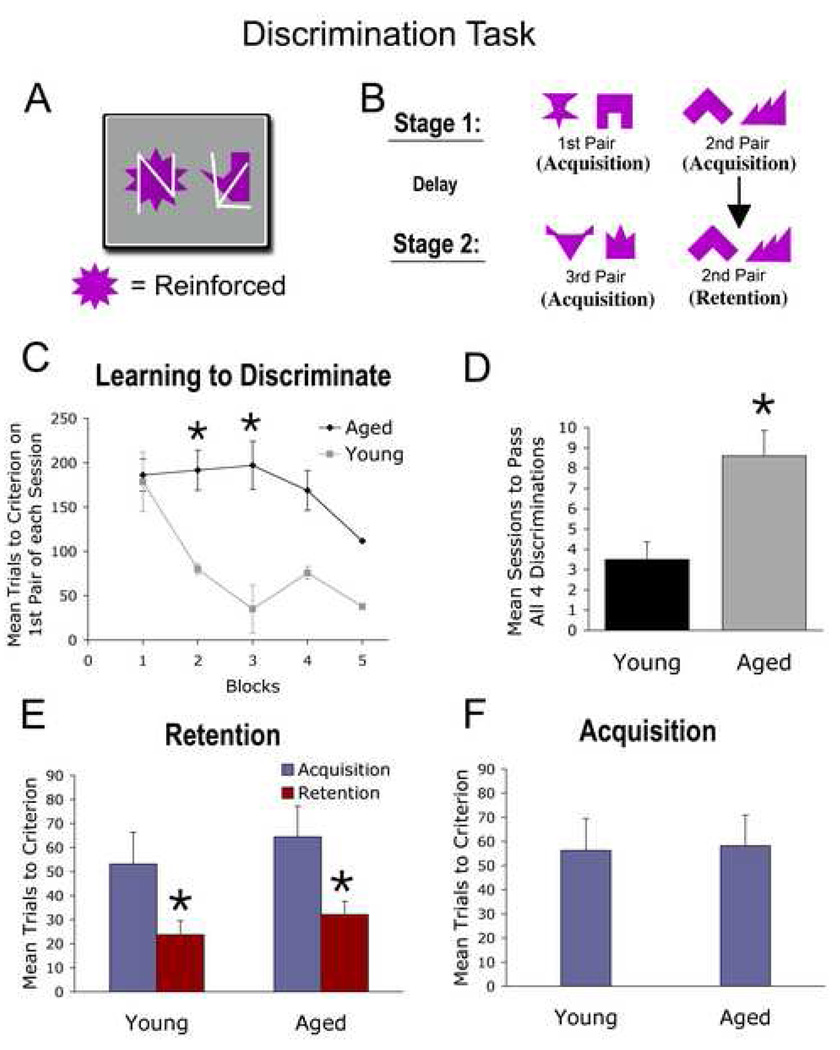

Figure 3. Shape Discrimination and Retention.

(A) The shape discrimination task utilizes pairs of solid cues and superimposed multi-lined distracters to examine subjects’ ability to discriminate objects, and to retain discriminations after delays. The monkey learns to discriminate two solid cues when one is reinforced (e.g., sun-shaped cue) and the other shape is not, while ignoring the distracting white lines. (B) Monkeys were trained on 4 pairs of discriminations to a criterion of 90% accuracy in an individual test session. In the Acquisition phase, the monkey learns two novel discrimination pairs (1st, 2nd pairs) followed by a delay (1 hr, 24 hr); in the retention phase, the monkey learns a 3rd novel pair and then is retested on the 2nd pair (as a measure of retention for a previously learned discrimination). (C) In initially learning to successfully discriminate a single pair of objects, aged monkeys (N=9) and young monkeys (N=4) both required nearly 200 trials in Block 1 to reach criterion performance (correct identification of the reinforced object in 18 of 20 successive trials). In subsequent Blocks, young monkeys rapidly learned novel discriminations, whereas aged subjects continued to require many trials (* p<0.05 in Blocks 2 and 3). Over Blocks 4 and 5, the performance of aged monkeys improved and no longer differed significantly from young subjects. (D) The number of sessions required to learn all four discrimination pairs successfully for the first time also differed significantly when comparing young and aged monkeys (p<0.05). (E) However, once the monkeys were able to learn the “rules” of the shape discrimination task (to complete all 4 discriminations in a single session), subsequent Acquisition and Retention of discrimination pairs did not differ among groups. Aged and young groups both required 50–65 trials to Acquire the discrimination, and Retention of the discrimination after 1 or 24 hours improved significantly by approximately 50% in both groups compared to Acquisition performance (p<0.05). (F) The performance of young and aged monkeys did not differ in acquiring the 3rd novel discrimination, indicating that improved performance on the repeated (2nd) discrimination pair in the Retention phase (panel E) likely represented retention of the previously performed discrimination, rather than a practice effect.

Successful completion of the discrimination pairs in a session indicates that the monkey has acquired the rules of the discrimination task (i.e., to discriminate the shape and ignore the distracting lines). Performance on the retention component of the task after 1 or 24 hr delays can then be analyzed to gauge retention for previously learned shapes. Monkeys received approximately 15 sessions of testing on the discrimination task.

Motor Task

4 young adult (7.6 ± 1.1 years) and 7 aged (24.0 ± 0.8) monkeys (Table 1) were tested on a timed task measuring speed to retrieve raisins using two hands, as a general reflection of motor agility (Fig. 4A). This was the only task that did not use the automated touch screen, and was used to confirm the general ability of monkeys to use the hands to generate responses. Raisins were placed entirely within round holes measuring 8 mm in diameter, 8 mm in depth, and spaced 13 mm apart in a 3 × 5 array. Successful retrieval required use of both hands, pushing the raisin with one finger from one side of the board, and retrieving the raisin from the opposite side with the other hand (Fig. 4B). The time required to retrieve 15 raisins was recorded with a limit of 120 s.

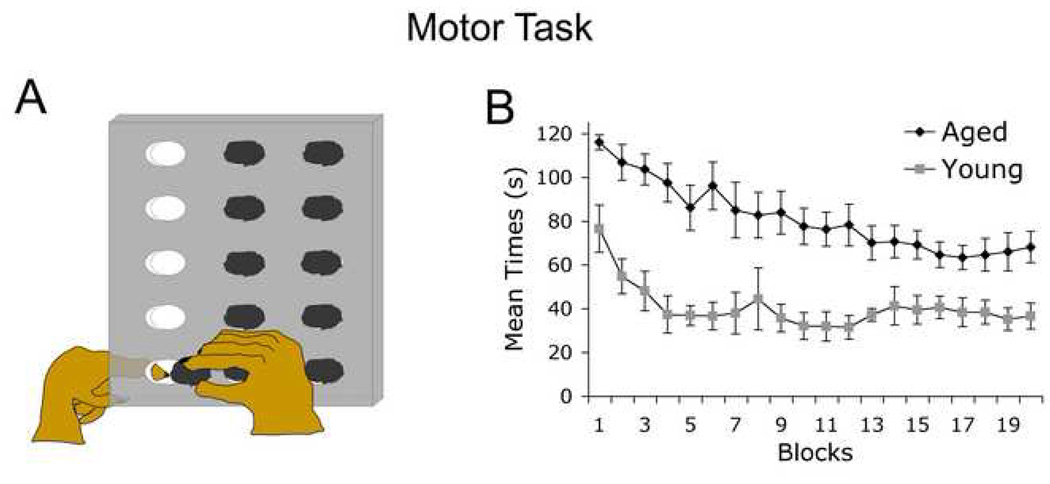

Figure 4. Motor Performance.

(A) Fine motor performance is assessed by measuring the time required for the subject to remove all raisins from a hole board, using one hand to push the raisin and the other to retrieve it with a pincer motion. (B) Both young (N=4) and aged (N=7) subjects readily completed the task, although young adult monkeys were significantly faster. Both aged and young subjects possessed sufficient levels of manual dexterity to participate in computer touch screen testing, which imposed far simpler motor demands (simply touching the screen) than the raisin board task.

Sequence of Task Presentation

Based on pilot data suggesting that concurrent testing on multiple tasks may result in interference in task performance, subjects completed testing on individual tasks before moving to the next task, in the following order: Visuospatial Task, Spatial Working Memory, Shape Discrimination, and Motor Task. Subjects would typically begin training on their “next” task the day after successfully completing testing of the preceding task.

Data Analysis

Results were statistically analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA and post-hoc Fisher’s in tasks with multiple trials, or two-tailed t-tests if comparing two groups of data, using a significance criterion of p<0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses failed to show gender-dependent differences in outcomes and results from the genders have been combined in the presentations; however, because these studies were not prospectively designed to assess gender-based differences in outcomes, conclusions regarding gender-based differences in testing are not attempted (see Discussion).

3. Results

Visuospatial Learning Task

On the simplest form of the visuospatial learning task, requiring correct stimulus choice among two possible locations, aged monkeys exhibited significant impairments compared to young subjects (Age x Blocks Interaction, p<0.0001; Fig. 1A). Young monkeys exhibited significant improvement in task performance over serial blocks of testing (post-hoc repeated measures ANOVA, p<0.001), whereas aged subjects did not (post-hoc repeated measures ANOVA non-significant). In addition, the performance of aged subjects differed significantly from young subjects on the final two blocks of testing (post-hoc t-test, p<0.05; Fig. 1A). Not surprisingly, when testing under these conditions was made more complex by presenting monkeys with 3 possible locations in the Choice phase of testing (Fig 1B), aged subjects continued to perform only slightly above chance and failed to improve over trial blocks (Age x Block Interaction, p<0.05; post-hoc repeated measures ANOVA non-significant), whereas young subjects tended to exhibit improving performance over successive blocks (repeated measures ANOVA, p<0.10). Post-hoc analyses revealed aged monkeys were significantly impaired compared to the young monkeys on the 7th block of training (p<0.05).

When conditions of the task changed such that repeated trials of the same stimulus/location were provided (allowing correction of errors, as described above in Methods), aged subjects could learn the task and exhibited significant improvements in performance over time (Age x Block interaction, p<0.05). Under these conditions, aged monkeys eventually learned to choose the correct location in 90% of trials, performing as well as young subjects (Fig. 1C). Thus, task difficulty could be modified to allow learning in aged subjects by allowing corrective trials.

If task difficulty was then further increased by presenting two successive stimuli in the “Sample” and “Choice” phase while continuing to allow repeated trials (for error correction), young monkeys performed better than aged subjects (Age x Block interaction, p<0.05; Fig 1D). Nonetheless, the performance of both young and aged monkeys significantly improved over time (post-hoc repeated measures ANOVA: Young, p<0.001; Aged, p<0.01). Overall, the performance of aged monkeys improved from choice accuracy of 15% in early trials to 33% in final trials (p<0.01), while young monkeys improved from initial choice accuracy of 18% to final accuracy of 60% (p<0.001; Fig. 1D). Thus, aged subjects were able to improve performance on the visuospatial task when provided multiple trials, but their rate of learning was slower than that of young monkeys.

Motivation did not account for differences in performance on this task, as the percent of trials generating a response from the subject did not differ as a function of age: Young 97.1 ± 3.5% vs. Aged 92.6 ± 7.3% (p-value non-significant).

Spatial Working Memory

In the simplest version of this self-ordered spatial working memory task (two boxes and a short 0.25 s delay, similar to a delayed non-match to sample), young and aged monkeys exhibited significant improvements in choice accuracy across testing blocks (ANOVA: Block Main Effect, p<0.02; Fig. 2C). Although there was no significant difference in the rate of learning between young and aged groups (Age x Block interaction, ANOVA non-significant), the accuracy of aged monkeys was significantly impaired compared to young subjects (ANOVA: Age Main Effect; p<0.05). Neither aged nor young monkeys were able to learn the more spatially demanding 3-box condition of this task over 15 trial blocks sampling a total of 80 test sessions (ANOVA, non-significant; Fig. 2D).

Shape Discrimination and Retention

In each testing session, monkeys are required to perform four pairs of discriminations (three novel pairs, one repeated pair) to a criterion of 90% accuracy (Fig. 3A,B). During the initial training sessions on this task, both young and aged monkeys required nearly identical numbers of trials to reach criterion performance in completing just the first discrimination pair (~180 trials; Block 1 in Fig. 3C). Young monkeys subsequently improved rapidly, requiring only 80 trials to reach criterion performance in learning the first discrimination pair on the second training block, while aged monkeys required from 150–200 trials over the first 4 blocks of training. Thus, the rate of learning differed significantly comparing young and aged subjects (Age x Block interaction, p<0.01). While aged monkeys required significantly more trials than young monkeys to reach criterion performance on both the 2nd and 3rd blocks of training, aged monkeys nonetheless improved significantly over trial blocks (ANOVA, Age Main effect, p<0.05). Comparing the number of training sessions required to first complete all four pairs of discriminations in a single test session (Fig. 3D), young monkeys required an average of only 3.5 sessions, while aged monkeys required 8.6 sessions to “pass” all four pairs (t-test, p<0.05).

Next, we compared the performance of young and aged subjects in shape discrimination test sessions wherein all four pairs were successfully completed (i.e., criterion performance of 90% correct responses was attained), with particular focus on retention of previously learned shapes after delays of either 1 hour or 1 day. No significant differences were observed when comparing performance after 1-hr and 24-hr delays across age groups as measured by trials to criterion (1-hr: 31.9 ± 5.8; 24-hr: 27.3 ± 2.4), thus the 1-hr and 24-hr delays were combined for subsequent analyses. Young and aged monkeys exhibited similar performance in acquisition of the 2nd novel pair of objects (blue columns in Fig. 3E). Furthermore, both young adult and aged monkeys exhibited significantly improved choice accuracy for previously learned stimuli after delays (p<0.05, paired t-test, red columns in Fig. 3E). The magnitude of improvement in performance on re-testing after the delay was similar for aged and young subjects, with an approximate 50% improvement in mean number of trials to criterion on the retention test (p<0.05, paired t-test, Fig. 3E). Both young and aged groups also showed comparable performance in the acquisition of the 3rd novel pair (Fig. 3F).

Thus, while aged subjects required more sessions to first complete all four pairs of discriminations (Fig. 3D), their performance thereafter was similar in both the acquisition and retention of discriminations pairs. Once again, effort did not differ between young and aged monkeys (mean number of trials generating monkey responses: Young: 98.5 ± 2.2, Aged 96.8 ± 1.3: t-test, p-value non-significant).

Motor Learning Task

This non-computerized task measured the ability of monkeys to use both hands to retrieve raisins from slots in a board (Fig. 4A). Mean performance values for both young and aged groups indicated that subjects were able to successfully retrieve raisins in the allotted time of 120 sec (Fig. 4B). While young monkeys retrieved raisins faster (ANOVA: Age Main Effect; p<0.05), all subjects exhibited motor performance reflective of capability to participate in CANTAB touch screen use.

4. Discussion

The present study identifies age-related cognitive deficits in rhesus monkeys, using in aged subjects a computerized testing battery that is analogous in design and implementation to paradigms employed in human studies. Aged rhesus monkeys exhibit specific impairments in both visuospatial learning and spatial working memory, likely reflecting impairment in functions associated with the frontal lobe (Pantelis et al., 1997; Robbins et al., 1998). Aged monkeys also exhibit an initial impairment in learning a discrimination task (i.e., in learning the rules of the task), but thereafter are not impaired in performing new discriminations or in retaining discrimination pairs after a delay, suggesting general integrity of systems related to temporal-hippocampal function. Thus, aged monkeys exhibit a selective decline in functions that are generally associated with frontal systems with relative sparing of temporal-hippocampal systems, a finding that parallels patterns observed in previous human aging studies using similar computer-based, touch screen systems (Mutter et al., 2006; Rabbitt and Lowe, 2000; Robbins et al., 1998; Robbins et al., 1994).

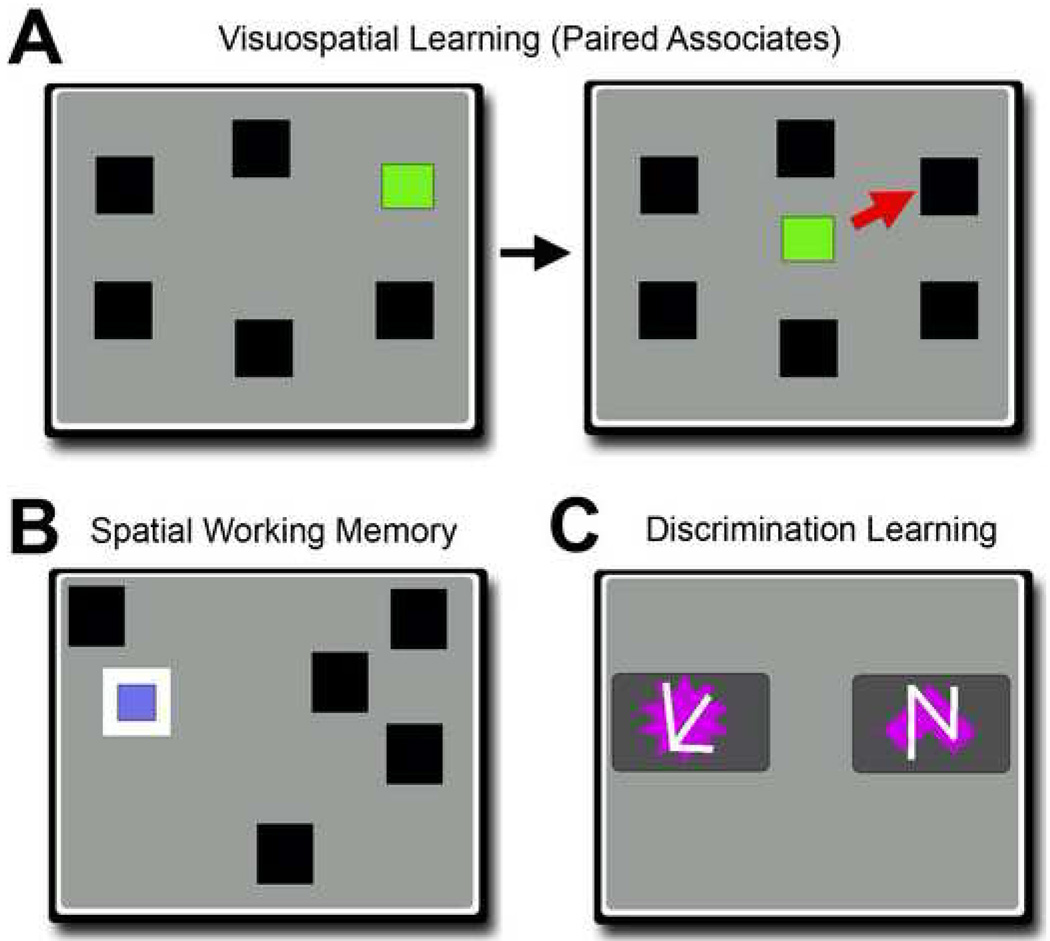

Elderly humans exhibit impairments on both visuospatial learning (Rabbitt and Lowe, 2000; Robbins et al., 1994) and spatial working memory (Robbins et al., 1998) when tested on a CANTAB system. The visuospatial learning task used in the human version of CANTAB employs a greater number of choice stimuli than the monkey version (Fig. 5), but imposes similar spatial demands, temporal parameters and task performance requirements. Both monkey (present study) and human (Rabbitt and Lowe, 2000; Robbins et al., 1994) experiments demonstrate age-related impairments on the task that generally represent a reduction in performance levels of 25–35% compared to young subjects. The version of the CANTAB spatial working memory task employed in humans (“Self-Ordered Spatial Sort”) is also more complex than the primate version of the task, testing up to 12 stimuli per trial compared to 3 stimuli in the primate version. Yet the nature of the stimuli, temporal parameters and design of the tasks used in the two species are similar (Fig. 5). Once again, aged humans and monkeys exhibit similar decrements of approximately 25–35% in performance compared to younger adults (Robbins et al., 1998). Thus, under conditions that are similar in design and performance criteria, but different in complexity, aged humans and monkeys exhibit age-related deficits on tasks assessing functional integrity of frontal systems.

Figure 5. Human Version of the CANTAB tasks.

(A) In the human version of the visuospatial learning task (referred to as the “Paired Associates” task), the subject learns to associate a specific cue (e.g, green box) with one location in the Sample phase of the task, left panel. Up to 8 different cues are provided in different locations. After a brief delay, the subject is then shown the cue in the center of the screen, and must touch the box where the cue was originally located (indicated by the red arrow that is not normally shown during testing). As in the monkey version of the task, human subjects are provided repeated corrective trials. (B) The human spatial working memory task requires the subject to touch each box once without returning to the same object repeatedly, as in the primate version. Once touched, a “blue token” is revealed and removed from the screen. (C) In the human CANTAB version of the discrimination task, referred to as “attentional set shifting,” humans are required to discriminate two purple shapes while ignoring white lines, similar to conditions of the discrimination task used in the current study. While the requirement to discriminate multiple stimuli is similar in the monkey and human version of the task, the monkey version differs by incorporating a prolonged delay to evaluate retention of a previously learned discrimination. In contrast, the human version proceeds to test progressively more difficult discriminations that shift between the purple shape and white line stimuli, without utilizing prolonged delays.

Temporal-hippocampal function is assessed on a spatial discrimination and retention task. The human version of the task (referred to as Intradimensional/Extradimensional set shift) uses target pairs of stimuli, together with distracting pairs of stimuli that are to be ignored (Fig. 5). In progressive stages of the task, humans are required to correctly choose reinforced objects through several “switches” in stimulus reinforcement. The monkey version of the task is simpler, requiring that subjects correctly perform discriminations in the presence of distracters, with temporal delays over intervals up to 24 hours to assess retention. Aged humans (Mutter et al., 2006) and monkeys (Rapp, 1990; Voytko, 1993) both exhibit impairment when initially learning the rules of a discrimination task, a pattern that may reflect impairment of working memory (frontal) systems. Once the rules of the task are learned, however, neither aged humans nor monkeys exhibit deficits when performing novel simple or compound discriminations (Mutter et al., 2006) and Fig. 3), a component of the task that is likely primarily sensitive to temporal-hippocampal substrates (Luciana and Nelson, 1998; Moss et al., 1981). After long delays, we find no deficit in retention of a previously learned association, comparing young and aged monkeys. Thus, results of human and monkey testing demonstrate general integrity of temporal-hippocampal systems across aging, and impairment of frontal memory systems.

The primate version of this computerized testing method is less complex than human versions, reflecting the need to assess the distinct cognitive capabilities of humans vs. monkeys. While it is possible that differences in the complexity of human vs. primate versions of the tasks may alter or extend the specific neural substrates that are being recruited to perform the tasks, it remains that case that many features of the primate and human versions of the task are analogous. That is, the tasks are designed similarly (using similar stimuli and task construction), require self-motivated touches of a computer screen to register responses, and are unbiased by examiner involvement. It seems reasonable therefore to draw the conclusion that there are similarities in the nature and extent of cognitive impairment when comparing humans and rhesus monkeys. This similarity in pattern of cognitive decline suggests that parallel cortical systems exhibit vulnerability to functional decline with aging in the two species, and that cellular mechanisms underlying age-related decrements in performance may be similar.

Patterns of age-related cognitive decline detected in this study using home cage-based computer touch screen methods parallel previous observations in aged monkeys using traditional and more time-consuming testing conditions with a human operator (Herndon et al., 1997; Moss et al., 1997; Rapp, 1990; Rapp and Amaral, 1989; Smith et al., 2004). For example, aged monkeys exhibited decrements in working memory on a delayed response task as assessed in the Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus (WGTA) (Bartus et al., 1978; Smith et al., 2004), an apparatus in which test objects cover food reward wells that are baited manually by a human experimenter. Deficits were also reported in aged monkeys when initially learning to perform pattern discriminations (i.e., in learning the rules of the task under study), but not when performing subsequent, novel discriminations, in the WGTA (Rapp, 1990). These findings, employing traditional experimental methods, are consistent with results of the current study. However, there may be some benefit in drawing conclusions regarding similarities in patterns of cognitive deficits in aged monkeys versus humans when using the same testing devices and analogous paradigms in the test species, as performed in this study. Bartus and colleagues reported age-related decrements in monkeys on cognitive batteries using innovative automated testing devices as long ago as 1978 (Bartus et al., 1978); while these devices were semi-automated, they did not have the advantage of being home-cage based and simulating human testing conditions. A set of automated tasks measuring visual discrimination and spatial learning was reported in aged monkeys using a touch screen system, although home cage testing was not conducted (Voytko, 1993). More recently, Buccafusco and colleagues reported the use of an automated, home cage-based device to assess performance on a delayed matching-to-sample task in young and aged monkeys (Buccafusco et al., 2007a; Buccafusco et al., 2002; Buccafusco et al., 2007b). Aged monkeys exhibited deteriorating performance on this task relative to young subjects at longer delays, and exhibited greater sensitivity to cholinergic blocking drugs and distracting stimuli than young monkeys (Buccafusco et al., 2002). The latter group’s detection of decremental performance in aged subjects at longer delays is consistent with our own findings across several additional tasks, indicating that aged monkeys exhibit impaired performance relative to young when task difficulty is progressively increased. In addition, automated testing has been developed that is analogous to the Wisconsin Card Sorting task in humans, and reveals age-related deficits in monkeys (Moore et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2006).

Individual monkeys in this study were not all necessarily tested on the same tasks (see Table 1), potentially contributing to variability in performance. However, despite this potential source of variability, findings across tasks and groups were quite consistent and revealed significant age-related impairments comparing young and aged groups of subjects. The ability to consistently demonstrate performance deficits on individual features of each task, despite the potential variability introduced by differences in training paradigms, suggests the robustness of age-related decrements in performance and the sensitivity of these methods for detecting them. The reliability of the data are further suggested by the fact that aged monkeys exhibited significant improvement in performance on some components of each task, yet at a significantly impaired level of proficiency compared to young monkeys (including visuospatial learning, working memory and discrimination learning). Thus, the impairment of aged monkeys relative to young subjects was not a simple matter of testing at “floor” levels of performance.

A potential confound in interpreting the present dataset is the effect of gender on cognitive performance, as various studies indicate age-related gender differences in non-human primates on cognitive and motor tasks (Hao et al., 2007; Lacreuse et al., 2005a; Lacreuse et al., 1999; Lacreuse et al., 2005b; Rapp et al., 2003). The present study was not prospectively designed or powered to assess the effect of gender on performance, as only two aged females were assessed on each cognitive task (Table 1), and planned statistical analyses therefore did not control for gender as an independent variable. Inspection of individual performance of aged females on each cognitive task indicates that aged females performed slightly better than their male counterparts (data not shown), thus overall group differences in performance between young and aged groups in this study were not likely attributable purely to gender effects. Nonetheless, this study cannot address questions regarding the effect of gender on age-related cognitive impairment, and adequately powered and prospectively planned studies are required to address this question, as reported by others (Hao et al., 2007; Lacreuse et al., 2005a; Lacreuse et al., 1999; Lacreuse et al., 2005b; Rapp et al., 2003).

In the motor realm, the present study identified an age-related decline in speed of completion of a skilled bimanual motor task. Previous evidence widely indicates a slowing of motor speed with aging in both humans (Birren and Fisher, 1995; Scuteri et al., 2005) and non-human primates (Walton et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2000). The extent of reduction with aging, ranging from 33% to 50%, is similar when comparing monkeys and humans. Nonetheless, aged monkeys clearly possessed sufficient simple motor capabilities to participate in and respond to the cognitive tasks of this computerized apparatus, reflected by similar levels of performance to young monkeys on the discrimination task, and similar numbers of object/screen touches on all tasks. The similar levels of screen touches on all tasks also indicate that there are no significant differences in effort to engage in the task when comparing young and aged monkeys, suggesting that the aged monkeys were motivated to work for the food reward in each case.

The use of a computerized test battery offers significant advantages for exploring cognitive changes in non-human primates. First, monkeys are tested in their home cage through a video touch screen that allows data collection independent of human interaction or potential experimenter bias, and without disturbing or stressing the monkey through the use of chair training or restraint. Second, a large number of subjects can be tested simultaneously with the use of multiple computers, and a battery of tasks can be completed within several months. Third, as summarized above, findings using the computerized battery are consistent with previous reports of cognitive testing in aged monkeys that used traditional, human-based experimentation (Rapp, 1990; Rapp et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2004). Finally, the findings can be extrapolated, with important caveats, to make predictions regarding human patterns of cognitive response. That is, as shown above, the performance of aged vs. young subjects exhibits similar patterns of decline across species with aging, and a similar magnitude of decline as a function of age when compared to young. This predictive pattern must of course be considered with the caveat that task complexity is very different in the monkey and human versions of the tasks: monkeys generally perform simplified versions of each test. Another important caveat is that humans are given instructions when performing initial trials on the tasks used in this study, whereas monkeys learn the rules of the tasks by trial and error. Thus, rates of initial learning cannot be compared. Nonetheless, once monkeys acquire the rules of the tasks, the design, stimuli and response requirements of the tasks are similar or identical to human versions, and correlations in performance are reasonable. Importantly, we find striking similarities in patterns of age-related decline when comparing monkeys and humans. The patterns of deficits in aged monkeys reflect those observed in “normal aged” humans rather than the more severe and diffuse patterns observed in human dementing disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Michael Taffe for helpful advice in set-up of the CANTAB system, Heather McKay for assistance with animal testing. This work was supported by the NIH (AG10435), the Shiley Family Foundation, the Institute for the Study of Aging, and the Veterans Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for this study.

References

- Bartus RT, Fleming D, Johnson HR. Aging in the rhesus monkey: debilitating effects on short-term memory. J. Gerontol. 1978;33:858–871. doi: 10.1093/geronj/33.6.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JT, Walker JA, Olton DS. Neuroanatomical bases of spatial memory. Brain. Res. 1980;200:307–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90922-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birren JE, Fisher LM. Aging and speed of behavior: possible consequences for psychological functioning. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1995;46:329–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell AD, Sahakian BJ, Vesey R, Semple JM, Robbins TW, Hodges JR. Detecting dementia: novel neuropsychological markers of preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2004;17:42–48. doi: 10.1159/000074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco JJ, Terry AV, Jr, Decker MW, Gopalakrishnan M. Profile of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists ABT-594 and A-582941, with differential subtype selectivity, on delayed matching accuracy by young monkeys. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007a;74:1202–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco JJ, Terry AV, Jr, Murdoch PB. A computer-assisted cognitive test battery for aged monkeys. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2002;19:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s12031-002-0030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco JJ, Terry AV, Jr, Webster SJ, Martin D, Hohnadel EJ, Bouchard KA, Warner SE. The scopolamine-reversal paradigm in rats and monkeys: the importance of computer-assisted operant-conditioning memory tasks for screening drug candidates. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007b doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0887-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CR, Wood SJ, Anderson V, Buchanan JA, Proffitt TM, Mahony K, Pantelis C. Normative data from the CANTAB. I: development of executive function over the lifespan. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2003;25:242–254. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.2.242.13639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler KS, Saling MM, Conway EL, Semple JM, Louis WJ. Paired associate performance in the early detection of DAT. J. Int. Neuropsychol. 2002:58–71. Soc 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RL, Brown RG, Owen AM, Bullmore ET, Howard RJ. Task-induced deactivations during successful paired associates learning: an effect of age but not Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2006;31:818–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RL, Brown RG, Owen AM, ffytche DH, Howard RJ. fMRI BOLD response to increasing task difficulty during successful paired associates learning. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1006–1019. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00365-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Koivisto K, Partanen K, Laakso MP, Riekkinen PJ, Soininen H. Decline of frontal lobe functions in subjects with age-associated memory impairment. Neurology. 1997;48:148–153. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Rapp PR, Janssen WG, Lou W, Lasley BL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Interactive effects of age and estrogen on cognition and pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:11465–11470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704757104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon JG, Moss MB, Rosene DL, Killiany RJ. Patterns of cognitive decline in aged rhesus monkeys. Behav. Brain. Res. 1997;87:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH. Learning and Memory in Normal Aging. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lacreuse A, Diehl MM, Goh MY, Hall MJ, Volk AM, Chhabra RK, Herndon JG. Sex differences in age-related motor slowing in the rhesus monkey: behavioral and neuroimaging data. Neurobiol. Aging. 2005a;26:543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacreuse A, Herndon JG, Killiany RJ, Rosene DL, Moss MB. Spatial cognition in rhesus monkeys: Male superiority declines with age. Horm. Beh. 1999;36:70–76. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacreuse A, Kim CB, Rosene DL, Killiany RJ, Moss MB, Moore TL, Chennareddi L, Herndon JG. Sex, age, and training modulate spatial memory in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Behav. Neurosci. 2005b;119:118–126. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M, Nelson CA. The functional emergence of prefrontally-guided working memory systems in four- to eight-year-old children. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:273–293. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JA, Constable RT. Activation of human hippocampal formation reflects success in both encoding and cued recall of paired associates. Neuroimage. 2005;24:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. Impairment in abstraction and set shifting in aged rhesus monkeys. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. A non-human primate test of abstraction and set shifting: an automated adaptation of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2005;146:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. Executive system dysfunction occurs as early as middle-age in the rhesus monkey. Neurobiol, Aging. 2006;27:1484–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss M, Mahut H, Zola-Morgan S. Concurrent discrimination learning of monkeys after hippocampal, entorhinal, or fornix lesions. Neurosci. 1981;1:227–240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-03-00227.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss MB, Killiany RJ, Lai ZC, Rosene DL, Herndon JG. Recognition memory span in rhesus monkeys of advanced age. Neurobiol. Aging. 1997;18:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutter SA, Haggbloom SJ, Plumlee LF, Schirmer AR. Aging, working memory, and discrimination learning. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2006;59:1556–1566. doi: 10.1080/17470210500343546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson LG. Memory function in normal aging. Acta. Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2003;179:7–13. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton DS, Samuelson RJ. Remembrance of places passed: Spatial memory in rats. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 1976;2:97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Morris RG, Sahakian BJ, Polkey CE, Robbins TW. Double dissociations of memory and executive functions in working memory tasks following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalo-hippocampectomy in man. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 5):1597–1615. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.5.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Roberts AC, Polkey CE, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Extra-dimensional versus intra-dimensional set shifting performance following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalo-hippocampectomy in man. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:993–1006. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90063-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Barnes TR, Nelson HE, Tanner S, Weatherley L, Owen AM, Robbins TW. Frontal-striatal cognitive deficits in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 10):1823–1843. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.10.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt P, Lowe C. Patterns of cognitive ageing. Psychol. Res. 2000;63:308–316. doi: 10.1007/s004269900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PR. Visual discrimination and reversal learning in the aged monkey (Macaca mulatta) Behav. Neurosci. 1990;104:876–884. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.6.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PR, Amaral DG. Evidence for task-dependent memory dysfunction in the aged monkey. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:3568–3576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03568.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PR, Kansky MT, Roberts JA. Impaired spatial information processing in aged monkeys with preserved recognition memory. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1923–1928. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705260-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PR, Morrison JH, Roberts JA. Cyclic estrogen replacement improves cognitive function in aged ovariectomized rhesus monkeys. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5708–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05708.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, James M, Owen AM, Sahakian BJ, Lawrence AD, McInnes L, Rabbitt PM. A study of performance on tests from the CANTAB battery sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in a large sample of normal volunteers: implications for theories of executive functioning and cognitive aging.Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1998;4:474–490. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798455073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, James M, Owen AM, Sahakian BJ, McInnes L, Rabbitt P. Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): a factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteers. Dementia. 1994;5:266–281. doi: 10.1159/000106735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian BJ, Owen AM. Computerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: discussion paper. J. R. Soc. Med. 1992;85:399–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuteri A, Palmieri L, Lo Noce C, Giampaoli S. Age-related changes in cognitive domains. A population-based study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:367–373. doi: 10.1007/BF03324624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski M, Buschke H. Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships among age, cognition, and processing speed. Psychol. Aging. 1999;14:18–33. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Rapp PR, McKay HM, Roberts JA, Tuszynski MH. Memory impairment in aged primates is associated with focal death of cortical neurons and atrophy of subcortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4373–4381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4289-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffe MA, Weed MR, Gutierrez T, Davis SA, Gold LH. Modeling a task that is sensitive to dementia of the Alzheimer's type: individual differences in acquisition of a visuo-spatial paired-associate learning task in rhesus monkeys. Behav. Brain. Res. 2004;149:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytko ML. Cognitive changes during normal aging in monkeys assessed with an automated test apparatus. Neurobiol. Aging. 1993;14:643–644. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90055-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton A, Scheib JL, McLean S, Zhang Z, Grondin R. Motor memory preservation in aged monkeys mirrors that of aged humans on a similar task. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver Cargin J, Maruff P, Collie A, Masters C. Mild memory impairment in healthy older adults is distinct from normal aging. Brain Cogn. 2006;60:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed MR, Taffe MA, Polis I, Roberts AC, Robbins TW, Koob GF, Bloom FE, Gold LH. Performance norms for a rhesus monkey neuropsychological testing battery: acquisition and long-term performance. Brain. Res. Cogn. Brain. Res. 1999;8:185–201. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Andersen A, Smith C, Grondin R, Gerhardt G, Gash D. Motor slowing and parkinsonian signs in aging rhesus monkeys mirror human aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000;55:B473–B480. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.10.b473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]