Abstract

Context/Objective

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and even mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy are both associated with increased risks of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the future. Because the metabolic syndrome also identifies patients at risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, we hypothesized that gestational dysglycemia may be associated with an unrecognized latent metabolic syndrome. Thus, we sought to evaluate the relationship between gestational glucose tolerance status and postpartum risk of metabolic syndrome.

Design/Setting/Participants

In this prospective cohort study, 487 women underwent oral glucose tolerance testing in pregnancy and cardiometabolic characterization at 3 months postpartum. The antepartum testing defined three gestational glucose tolerance groups: GDM (n = 137); gestational impaired glucose tolerance (GIGT) (n = 91); and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) (n = 259).

Main Outcome Measure

The primary outcome was the presence of the metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum, as defined by International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and American Heart Association/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) criteria, respectively.

Results

The postpartum prevalence of IDF metabolic syndrome progressively increased from NGT (10.0%) to GIGT (17.6%) to GDM (20.0%) (overall P = 0.016). The same progression was observed for AHA/NHLBI metabolic syndrome (NGT, 8.9%; GIGT, 15.4%; and GDM, 16.8%; overall P = 0.046). On logistic regression analysis, both GDM (odds ratio, 2.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–3.94) and GIGT (odds ratio, 2.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–4.42) independently predicted postpartum metabolic syndrome.

Conclusions

Both GDM and mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy predict an increased likelihood of metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum, supporting the concept that women with gestational dysglycemia may have an underlying latent metabolic syndrome.

The metabolic syndrome has been defined by the concomitant clustering of central obesity, dysglycemia, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (1). Currently, controversy exists regarding its underlying etiology, diagnostic criteria, and even its clinical relevance (2, 3). Although this debate is ongoing, it is nevertheless established that the metabolic syndrome identifies a patient population at high risk for the future development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1–4).

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) shares some similarity to the metabolic syndrome, in that: 1) it too has been the subject of long-standing debate regarding its diagnostic criteria (5, 6); and 2) it also identifies patients who are at high risk of developing T2DM and CVD in the future (5–10). Of note, the patient population identified by GDM (i.e. young women of child-bearing age) is much younger than that typically associated with the metabolic syndrome. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that: 1) approximately 30–40% of women with a history of GDM exhibit the metabolic syndrome by 10 yr postpartum (11, 12); and 2) women with GDM have a 70% increased incidence of CVD compared with their peers, within just 11 yr after the index pregnancy (10). Interestingly, it has recently emerged that even mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy (i.e. less severe than GDM) is associated with increased long-term risks of T2DM and CVD, in both cases less than that of women with GDM but significantly higher than that of the general population (13–18). Thus, the spectrum of gestational glucose tolerance (i.e. from normal to mild glucose intolerance to GDM) appears to stratify young women with respect to their future diabetic and cardiovascular risk, much like the metabolic syndrome. In this context, we hypothesized that women with gestational dysglycemia may have an underlying latent metabolic syndrome at a nearly stage in its natural history. Therefore, our objective in this study was to characterize the relationship between glucose tolerance status in pregnancy and postpartum risk of the metabolic syndrome.

Subjects and Methods

This analysis was conducted in the setting of an ongoing prospective observational study in which a cohort of women recruited at the time of antepartum GDM screening is undergoing longitudinal cardiometabolic characterization in pregnancy and the postpartum. The protocol has previously been described in detail (14–16, 19). In brief, at our institution, all pregnant women are screened for GDM by 50-g glucose challenge test in late second trimester, followed by referral for a diagnostic oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) if the screening test is abnormal (1-h plasma glucose ≥7.8 mmol/liter). In the current study, regardless of the screening result, all participants underwent a 3-h 100-g OGTT for ascertainment of gestational glucose tolerance status. Participants were recruited either before or after the glucose challenge test, but always before the OGTT. The recruitment of women after an abnormal glucose challenge test served to enrich the study population for women with varying degrees of antepartum glucose intolerance, as previously noted (14, 19). At 3 months postpartum, participants returned to the clinical investigation unit for cardiometabolic characterization. The study protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. This analysis was performed in the first 487 women to have completed both the pregnancy OGTT and 3-month postpartum visit, representing 4-yr recruitment.

Participant assessments

On the morning of the antepartum OGTT, data regarding medical, obstetrical, and family history were collected by interviewer-administered questionnaire (14). As described previously (14), the OGTT stratified subjects into the following three glucose tolerance groups in pregnancy: 1) GDM [defined by exceeding two or more National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) (20) glycemic thresholds on the OGTT]; 2) gestational impaired glucose tolerance (GIGT) (defined by exceeding only one NDDG threshold); and 3) normal glucose tolerance (NGT).

At 3 months postpartum, participants underwent a 2-h 75-g OGTT [with glucose tolerance status defined using Canadian Diabetes Association guidelines (21)] and measurement of weight, waist, and blood pressure [measured twice 5 min apart by automatic sphygmomanometer (Dinamap Pro 100–400; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI)]. Lipids were measured from fasting serum using the Roche Cobas 6000 c 501 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Canada).

Definitions of metabolic syndrome

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum was determined using two sets of criteria: 1) the American Heart Association/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) definition (22); and 2) the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition (23). In women, AHA/NHLBI metabolic syndrome is defined as the presence of three or more of the following five disorders: 1) waist circumference of at least 88 cm; 2) serum triglycerides of at least 1.7 mmol/liter or drug treatment for hypertriglyceridemia; 3) HDL cholesterol below 1.29 mmol/liter or drug treatment for low HDL; 4) elevated blood pressure, defined as blood pressure of at least 130/85 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive drug treatment in a patient with a history of hypertension; and 5) dysglycemia, defined as fasting glucose of at least 5.6 mmol/liter or previously diagnosed diabetes or use of drug treatment for hyperglycemia (22). The IDF definition of metabolic syndrome in women differs from the AHA/NHLBI version in that it requires the presence of waist circumference of at least 80 cm (≥90 cm in Japanese women), accompanied by at least two of the other four disorders (elevated triglycerides, low HDL, hypertension, dysglycemia; all defined in the same way as per AHA/NHLBI criteria) (23). Thus, the IDF and AHA/NHLBI definitions differ only in their respective waist thresholds and the IDF requirement that waist circumference be one of the component disorders.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). In Table 1, univariate differences across the three gestational glucose tolerance groups were assessed in pregnancy and at 3 months postpartum using ANOVA for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome component disorders at 3 months postpartum was determined for each of the three gestational glucose tolerance groups, with overall between-group differences in the prevalence of each disorder assessed by χ2 test (Fig. 1). The postpartum prevalence of metabolic syndrome was similarly compared between the groups (Fig. 2). This analysis was repeated with stratification of the GIGT group into two subsets: 1) 1-h GIGT, consisting of those women with GIGT on the basis of an isolated elevated glucose value at 1 h during the antepartum OGTT; and 2) 2- to 3-h GIGT, consisting of those women with GIGT due to isolated hyperglycemia at either 2 or 3 h during the OGTT (Fig. 3). Only two women had GIGT on the basis of an elevated fasting glucose and hence were not included in Fig. 3. Logistic regression was performed to determine which factors in pregnancy were independently associated with IDF metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Demographic, clinical, and metabolic parameters of study subjects in pregnancy and at 3 months postpartum

| NGT | GIGT | GDM | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 259 | 91 | 137 | |

| At OGTT in pregnancy | ||||

| Age (yr) | 33.9 (4.3) | 34.2 (4.2) | 34.5 (4.3) | 0.3606 |

| Gestation (wk) | 30.0 (28.0–32.0) | 29.0 (28.0–31.0) | 29.0 (28.0–31.0) | 0.0002 |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.0835 | |||

| White | 79.5 | 71.4 | 71.5 | |

| Asian | 8.5 | 19.8 | 11.0 | |

| Other | 12.0 | 8.8 | 17.5 | |

| Family history of T2DM (%) | 47.5 | 52.8 | 59.1 | 0.0271 |

| Parity (%) | 0.3978 | |||

| Nulliparous | 46.7 | 55.3 | 50.4 | |

| One or greater | 53.3 | 44.7 | 49.6 | |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1 (21.3–26.9) | 23.5 (21.8–27.7) | 25.0 (22.0–30.1) | 0.0114 |

| At 3 months postpartum | ||||

| Current breastfeeding (%) | 93.1 | 87.9 | 95.6 | 0.5131 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (23.0–28.9) | 26.0 (23.2–30.1) | 26.6 (23.7–31.1) | 0.0701 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.0 (60.4–78.0) | 70.0 (59.8–81.0) | 15.1 (61.7–82.0) | 0.2870 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 85.3 (79.8–94.0) | 87.0 (83.0–96.0) | 88.6 (81.0–99.0) | 0.0183 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 108.0 (102.0–114.0) | 110.0 (103.5–115.5) | 111.0 (105.0–119.5) | 0.0158 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 65.0 (60.0–70.0) | 64.0 (60.0–70.0) | 65.5 (60.0–73.0) | 0.4297 |

| Use of antihypertensive medication (%) | 0.8 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 0.0548 |

| HDL (mmol/liter) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 0.0015 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/liter) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.0003 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/liter) | 4.4 (4.2–4.7) | 4.7 (4.4–5.0) | 4.4 (4.4–5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose tolerance status (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| NGT | 92.3 | 83.5 | 67.2 | |

| Isolated IFG | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | |

| Isolated IGT | 7.3 | 11.0 | 27.0 | |

| Combined IFG and IGT | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| Diabetes | 0.0 | 3.3 | 4.4 | |

Continuous data are presented as median (interquartile range), with the exception of age, which is presented as mean (SD); categorical variables are presented as proportions. P values refer to overall differences across groups as derived from ANOVA for continuous variables or χ2 test for categorical variables. IFG, Impaired fasting glucose.

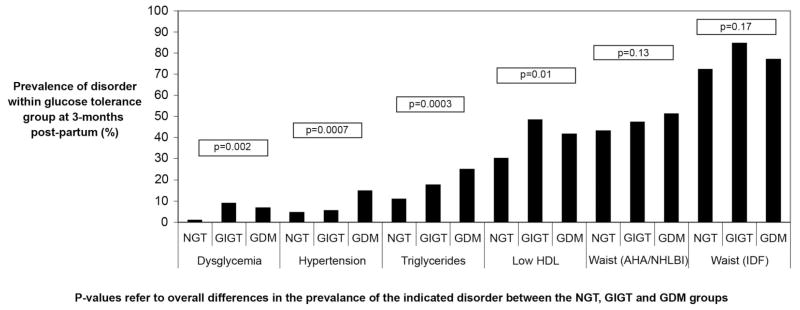

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome component disorders at 3 months postpartum by glucose tolerance status in pregnancy.

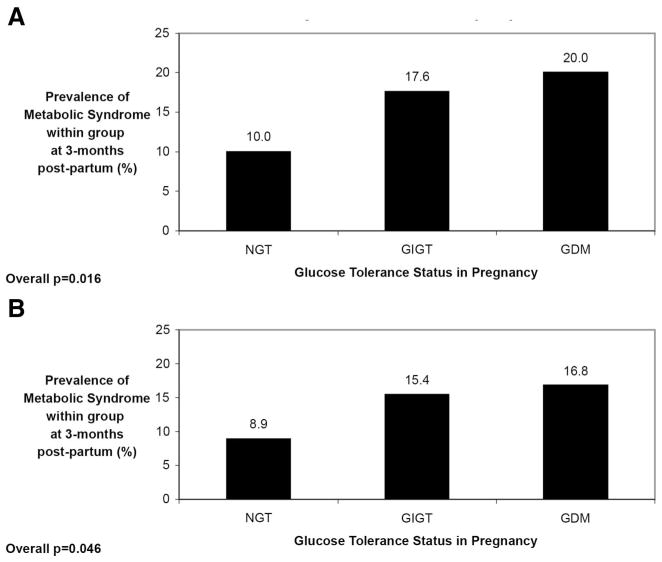

FIG. 2.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum by glucose tolerance status in pregnancy, using IDF definition (A) and AHA/NHLBI definition (B).

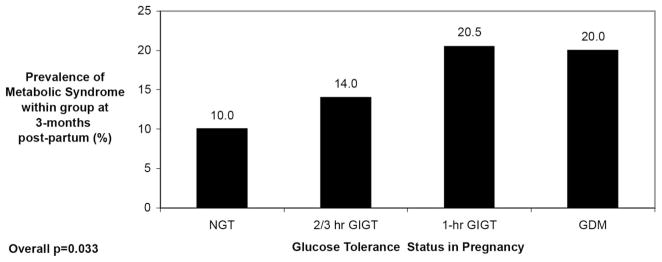

FIG. 3.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome (IDF criteria) at 3 months postpartum by glucose tolerance status in pregnancy, stratified as NGT, 2- to 3-h GIGT, 1-h GIGT, and GDM.

TABLE 2.

Logistic regression analysis of pregnancy factors for the prediction of postpartum metabolic syndrome (IDF criteria)

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.96 | 0.91–1.03 |

| Weeks gestation | 0.96 | 0.87–1.06 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 1.08 | 0.47–2.50 |

| Other | 1.32 | 0.59–2.96 |

| Family history of DM | 1.26 | 0.72–2.22 |

| Parity | 0.84 | 0.48–1.50 |

| Glucose intolerance in pregnancy | ||

| GIGT | 2.16 | 1.05–4.42 |

| GDM | 2.05 | 1.07–3.94 |

Reference group for ethnicity is white, reference group for parity is nulliparity, and reference group for glucose intolerance in pregnancy is NGT.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population at the time of the OGTT in pregnancy and at 3 months postpartum within each of the three gestational glucose tolerance groups: NGT (n = 259), GIGT (n = 91), and GDM (n = 137). Prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) increased, and a family history of diabetes was more common as gestational glucose tolerance worsened. The rates of cesarean section delivery also varied across the groups (NGT, 33.3%; GIGT, 49.4%; GDM, 38.9%; overall, P = 0.0281). At 3 months postpartum, the GDM and GIGT groups exhibited lower HDL levels and higher waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and fasting glucose(Table 1). Furthermore, the prevalence of postpartum dysglycemia was much higher in the GDM and GIGT groups, primarily consisting of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (Table 1). The overall prevalence of the metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum in the study population was 12.3% by AHA/NHLBI and 14.2% by IDF criteria. Consistent with their modest definitional differences, there was strong agreement between the AHA/NHLBI and IDF definitions in their classification of subjects (κ = 0.90 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.84–0.96]; P < 0.0001).

As shown in Fig. 1, the most common metabolic syndrome component disorders at 3 months postpartum were central obesity by IDF and AHA/NHLBI definitions, respectively, followed in turn by low HDL, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, and dysglycemia. Importantly, stratification of the women by glucose tolerance status in pregnancy revealed that the prevalence of each of the following disorders generally increased from the NGT to GIGT and GDM groups: dysglycemia (overall P = 0.002); hypertension (P = 0.0007); hypertriglyceridemia (P = 0.0003); and low HDL (P = 0.01). In contrast, there were no significant differences between the groups with respect to central obesity, as determined by either AHA/NHLBI (P = 0.13) or IDF (P = 0.17) criteria.

The significant differences in the prevalence rates of dysglycemia, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL contributed to very different rates of metabolic syndrome in the three glucose tolerance groups. Indeed, the prevalence of IDF metabolic syndrome rose in a stepwise fashion from 10.0% in the NGT group to 17.6% in the GIGT group to 20.0% in the GDM group (overall P = 0.016) (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the rates of AHA/NHLBI metabolic syndrome mirrored this pattern, rising from 8.9% in NGT to 15.4% in GIGT to 16.8% in the GDM group (overall P = 0.046) (Fig. 2B).

Sensitivity analysis

Because the retention of gestational weight gain could contribute to high rates of central obesity at 3 months postpartum, we performed a sensitivity analysis wherein we excluded the waist circumference criterion. Importantly, as before, the presence of two or more of the remaining four metabolic syndrome criteria progressively rose from NGT (11.2%) to GIGT (18.7%) to GDM (23.4%) (P = 0.005). Furthermore, even the presence of three or more of the four nonwaist criteria showed the same progression (NGT, 0.8%; GIGT, 4.4%; GDM, 5.8%; P = 0.01), suggesting that postpartum weight retention was likely not driving the differential risk of metabolic syndrome between the three glucose tolerance groups.

Pregnancy factors that predict postpartum metabolic syndrome

Having demonstrated increased rates of postpartum metabolic syndrome in women with any degree of glucose intolerance in pregnancy, we next performed logistic regression analysis to identify antepartum factors that independently predicted the presence of metabolic syndrome (IDF) at 3 months postpartum (Table 2). As hypothesized, both GDM and GIGT emerged as significant independent predictors of postpartum metabolic syndrome [GDM, odds ratio (OR), 2.05; 95% CI, 1.07–3.94; and GIGT, OR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.05–4.42]. Furthermore, when the same logistic regression analysis was repeated for an outcome defined as the presence of two or more of the four nonwaist metabolic syndrome criteria, both GDM (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.3–4.4) and GIGT (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.3) were again significant predictors. In addition, adjustment of the model in Table 2 for postpartum breastfeeding also did not attenuate these relationships (GDM, OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.1; and GIGT, OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.0–4.3), likely due to the uniformly high rates of breastfeeding in the study groups (as shown in Table 1). Finally, with adjustment for cesarean delivery, GDM remained a significant independent predictor of postpartum metabolic syndrome (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0), whereas the predictive value of GIGT was attenuated (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.9–4.0; P = 0.077).

To consider the roles of prepregnancy BMI and weight gain in pregnancy preceding the OGTT, we also included these two covariates in a logistic regression model in which the outcome was defined as the presence of two or more of the four nonwaist metabolic syndrome criteria. Again, GDM emerged as a significant independent predictor (OR, 2.2; 95%CI,1.2–4.4), whereas the predictive value of GIGT was attenuated (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.9–4.0; P = 0.09).

Heterogeneity of GIGT

Recognizing the known metabolic heterogeneity of GIGT (15, 24), we queried whether there existed an identifiable subset of women within the GIGT group who were at particularly high risk of metabolic syndrome. Specifically, because it has previously been demonstrated that GIGT due to isolated hyperglycemia at 1 h during the OGTT (1-h GIGT) bears metabolic similarity to GDM (15, 24), we stratified the women with GIGT into those with 1-h GIGT and those with 2- to 3-h GIGT (i.e. isolated hyperglycemia at either 2 or 3 h during the OGTT). This stratification revealed that the prevalence of postpartum metabolic syndrome in women with 1-h GIGT (20.5%) was indeed comparable to that of the GDM group (20.0%), whereas women with 2- to 3-h GIGT had an intermediate risk (14.0%) that nevertheless exceeded that of the NGT group (10.0%) (overall P = 0.033) (Fig. 3). Again, a sensitivity analysis was performed to exclude the effect of postpartum weight retention and resultant central obesity. As before, the presence of two or more of the four nonwaist metabolic syndrome criteria progressively rose from NGT (11.2%) to 2- to 3-h GIGT (14.0%) to 1-h GIGT (23.1%) to GDM (23.4%) (overall P = 0.009). In addition, the presence of three or more of the four non-waist criteria revealed a similar pattern, with 1-h GIGT (7.7%) resembling GDM (5.8%), whereas 2- to 3-h GIGT (2.0%) exceeded NGT (0.8%) (overall P = 0.008). Thus, among women with mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy, the glycemic response on antepartum OGTT may provide a means of identifying those who are at the highest risk of postpartum metabolic syndrome.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that as glucose tolerance in pregnancy worsens, the likelihood of postpartum metabolic syndrome progressively increases. Indeed, GDM and GIGT independently predict an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum. Furthermore, among women with mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy, those with 1-h GIGT represent a particularly high-risk group. These data thus suggest that antepartum GDM screening, as currently practiced, can provide previously unrecognized insight into a woman’s postpartum risk of metabolic syndrome and hence may identify subgroups of young women in whom early cardiovascular risk factor surveillance may be warranted.

Previous studies have reported high rates of the metabolic syndrome in women with a history of GDM (11, 12, 25–28). Indeed, at median 9.8 yr postpartum, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (by World Health Organization criteria) was 38.4% in Danish women with previous GDM, compared with 13.4% in their peers (11). Similarly, by 11 yr postpartum, the prevalence of National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III metabolic syndrome in 106 women with previous GDM was 27.2%, compared with 8.2% in controls (12). With rates of 20.0% (IDF) and 16.8% (AHA/NHLBI) in the GDM group at 3 months postpartum, the current findings are consistent with these earlier observations. Importantly, however, the current study also extends this literature in several ways. First, the prospective cohort design ensured systematic ascertainment of both glucose tolerance status in pregnancy (by OGTT) and postpartum cardiometabolic risk profile in all subjects. Second, this protocol was applied to a study population that covered the full spectrum of antepartum glucose tolerance from NGT to GIGT to GDM, revealing a graded association with the metabolic syndrome, analogous to recent observations regarding: 1) obstetrical risk due to fetal overgrowth (29, 30), and 2) long-term diabetic and cardiovascular risk (13–18). Moreover, the further substratification of GIGT revealed that women with 1-h GIGT may represent a particularly high-risk group, comparable to GDM, that can be readily identified on antepartum OGTT. Third, the presence of these associations at 3 months postpartum (as opposed to several years postpartum in earlier studies) suggests that differences between the study groups in prevalence rates of the metabolic syndrome and its component disorders may have existed before pregnancy. In that case, gestational dysglycemia may provide a unique opportunity to detect an unrecognized latent metabolic syndrome in young women.

Examination of the component disorders contributing to the high rates of postpartum metabolic syndrome in women with GDM and GIGT is very revealing. At 3 months postpartum, it is reasonable to anticipate that many women may not yet have lost their full gestational weight gain. However, although many women met the waist circumference criterion (by either IDF or AHA/NHLBI thresholds), it should be recognized that rates of central obesity by either IDF or AHA/NHLBI did not differ significantly between the three gestational glucose tolerance groups and did not drive the differences in metabolic syndrome (as confirmed by the sensitivity analyses excluding the waist criterion). Similarly, whereas rates of postpartum dysglycemia differed between the three groups (as would be expected), they were much lower than those for other metabolic syndrome component disorders, partly owing to the fact that the glucose criterion for both IDF and AHA/NHLBI is based on fasting glucose or established diabetes, but does not recognize IGT, which has previously been shown to represent the bulk of postpartum dysglycemia (14). Thus, the differences in postpartum prevalence of metabolic syndrome between the three study groups were largely driven by high rates of hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL in women with GDM and GIGT.

Women with a history of GDM have a markedly elevated risk of CVD compared with their peers (10). Furthermore, it has recently been shown that even women with mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy have an increased risk of CVD by 12 yr postpartum, lesser than that of women with GDM but significantly higher than that of women who maintain NGT in pregnancy (18). In this context, the significance of the current study lies in its suggestion that the metabolic syndrome and its component cardiovascular risk factors may play an early role (given their presence as early as 3 months postpartum) in mediating this differential long-term risk of CVD (i.e. which is highest in GDM, intermediate in GIGT, and lowest in women that maintain NGT in pregnancy). Specifically, gestational dysglycemia may provide an opportunity to detect an otherwise unrecognized latent metabolic syndrome early in its natural history and therefore potentially enable modification of the cardiovascular risk factors that will ultimately contribute to future CVD risk. Accordingly, it follows that some degree of postpartum surveillance of cardiovascular risk factors may be appropriate for women with GDM and those with GIGT or a subset thereof (such as women with 1-h GIGT). Ultimately, the early identification of high-risk women could enable enhanced surveillance, risk factor modification, and, potentially, disease prevention (31–33). Thus, whereas the current findings do not hold immediate implications for clinical care, they raise the important possibility that women with gestational dysglycemia and subsequent postpartum metabolic syndrome may represent a patient population at particularly high risk for the future development of metabolic and vascular disease. Further research with long-term follow-up is needed to address this possibility.

A limitation of this study is that, because pre-gravid measurement of cardiovascular risk factors was not performed, we cannot ascertain whether the observed differences in prevalence rates of the metabolic syndrome between the study groups necessarily preceded the pregnancy. Although it is noted that an earlier cross-sectional study reported that components of the metabolic syndrome in pregnancy were associated with GDM (34), longitudinal data linking pre-gravid measurements with subsequent GDM are lacking at this time. A second limitation is that the current study does not provide estimates for the population prevalence of metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum, due to the nature of the recruitment strategy, which was designed to enrich the study population for varying degrees of antepartum dysglycemia. Although the study thus does not provide population rates, this approach nevertheless made it possible to characterize the risk of postpartum metabolic syndrome across the full spectrum of gestational glucose tolerance.

In summary, both GDM and GIGT are independent predictors of metabolic syndrome at 3 months postpartum. Furthermore, among women with GIGT, those with 1-h GIGT represent a particularly high-risk group. Taken together, these data suggest that current antepartum GDM screening can provide insight into a woman’s postpartum risk of metabolic syndrome and may identify subgroups of young women in whom early targeted cardiovascular risk factor surveillance may be warranted as a strategy for the prevention of CVD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mount Sinai Hospital Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and Patient Care Services.

Operating grants for this study were provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (Grants MOP-67063 and MOP-84206), the Canadian Diabetes Association (Grant OG-3-08-2543-RR), and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (Grant NA 6747). R.R. holds a CIHR Clinical Research Initiative New Investigator Award, Canadian Diabetes Association Clinician-Scientist incentive funding, and University of Toronto Banting and Best Diabetes Centre New Investigator funding. A.J.G.H. holds a Tier-II Canada Research Chair in Diabetes Epidemiology. B.Z. holds the Sam and Judy Pencer Family Chair in Diabetes Research at Mount Sinai Hospital and the University of Toronto.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- GDM

gestational diabetes mellitus

- GIGT

gestational impaired glucose tolerance

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- NGT

normal glucose tolerance

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- OR

odds ratio

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

Footnotes

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Bentley-Lewis R, Koruda K, Seely EW. The metabolic syndrome in women. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:696–704. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:629–636. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn R, Buse J, Ferrannini E, Stern M American Diabetes Association; European Association for the Study of Diabetes. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal: joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2289–2304. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, Erwin PJ, Gami LA, Somers VK, Montori VM. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan TA, Xiang AH. Gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:485–491. doi: 10.1172/JCI24531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reece EA, Leguizamón G, Wiznitzer A. Gestational diabetes: the need for a common ground. Lancet. 2009;373:1789–1797. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feig DS, Zinman B, Wang X, Hux JE. Risk of development of diabetes mellitus after diagnosis of gestational diabetes. CMAJ. 2008;179:229–234. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentley-Lewis R. Late cardiovascular consequences of gestational diabetes. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:322–329. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah BR, Retnakaran R, Booth GL. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease in young women following gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1668–1669. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauenborg J, Mathiesen E, Hansen T, Glümer C, Jørgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Hornnes P, Pedersen O, Damm P. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in a Danish population of women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus is three-fold higher than in the general population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4004–4010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verma A, Boney CM, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Insulin resistance syndrome in women with prior history of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3227–3235. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carr DB, Newton KM, Utzschneider KM, Tong J, Gerchman F, Kahn SE, Heckbert SR. Modestly elevated glucose levels during pregnancy are associated with a higher risk of future diabetes among women without gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1037–1039. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Sermer M, Connelly PW, Hanley AJ, Zinman B. Glucose intolerance in pregnancy and future risk of pre-diabetes or diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2026–2031. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Sermer M, Connelly PW, Zinman B, Hanley AJ. Isolated hyperglycemia at 1-hour on oral glucose tolerance test in pregnancy resembles gestational diabetes in predicting postpartum metabolic dysfunction. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1275–1281. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Sermer M, Connelly PW, Hanley AJ, Zinman B. An abnormal screening glucose challenge test in pregnancy predicts postpartum metabolic dysfunction, even when the antepartum oral glucose tolerance test is normal. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Retnakaran R, Shah BR. Abnormal screening glucose challenge test in pregnancy and future risk of diabetes in young women. Diabet Med. 2009;26:474–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retnakaran R, Shah BR. Mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy and future risk of cardiovascular disease in young women: population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2009;181:371–376. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Sermer M, Connelly PW, Hanley AJ, Zinman B. The antepartum glucose values that predict neonatal macrosomia differ from those that predict postpartum pre-diabetes or diabetes: implications for the diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:840–845. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039–1057. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2008;32(Suppl 1):S10–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group 2005 The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 366:1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Retnakaran R, Zinman B, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Hanley AJ. Impaired glucose tolerance of pregnancy is a heterogeneous metabolic disorder as defined by the glycemic response to the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:57–62. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bo S, Menato G, Botto C, Cotrino I, Bardelli C, Gambino R, Cassader M, Durazzo M, Signorile A, Massobrio M, Pagano G. Mild gestational hyperglycemia and the metabolic syndrome in later life. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2006;4:113–121. doi: 10.1089/met.2006.4.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wijeyaratne CN, Waduge R, Arandara D, Arasalingam A, Sivasuriam A, Dodampahala SH, Balen AH. Metabolic and polycystic ovary syndromes in indigenous South Asian women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. BJOG. 2006;113:1182–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferraz TB, Motta RS, Ferraz CL, Capibaribe DM, Forti AC, Chacra AR. C-Reactive protein and features of metabolic syndrome in Brazilian women with previous gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;78:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vohr BR, Boney CM. Gestational diabetes: the forerunner for the development of maternal and childhood obesity and metabolic syndrome? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:149–157. doi: 10.1080/14767050801929430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, McCance DR, Hod M, McIntyre HD, Oats JJ, Persson B, Rogers MS, Sacks DA. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Casey B, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, Rouse DJ, Thorp JM, Jr, Sciscione A, Catalano P, Harper M, Saade G, Lain KY, Sorokin Y, Peaceman AM, Tolosa JE, Anderson GB. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1339–1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ. 2002;325:157–160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7356.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banerjee M, Cruickshank JK. Pregnancy as the prodrome to vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular risk. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:596–603. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, de Leiva A, Dunger DB, Hadden DR, Hod M, Kitzmiller JL, Kjos SL, Oats JN, Pettitt DJ, Sacks DA, Zoupas C. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S251–S260. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark CM, Jr, Qiu C, Amerman B, Porter B, Fineberg N, Aldasouqi S, Golichowski A. Gestational diabetes: should it be added to the syndrome of insulin resistance? Diabetes Care. 1997;20:867–871. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]