Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between incident depression symptoms and sub-optimal adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Methods

Participants in a cohort study of persons with HIV on HAART with at least 4 consecutive semi-annual study visits were included (n=225). Incident depression was defined as having two visits with a negative depression screening test followed by two visits with a positive test. Comparison group participants had four consecutive visits with a negative depression screening test. Sub-optimal adherence was defined as missing >5% of HAART doses in the past 7 days. We compared suboptimal adherence rates in those with and without incident depression symptoms and estimated the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of suboptimal adherence at visit 4 in those adherent at baseline (n=177), controlling for sociodemographic, behavioral and clinical variables.

Results

Twenty-two percent developed depression symptoms. Those developing depression symptoms had higher rates of suboptimal adherence at follow-up (45.1% vs. 25.9%, p<0.01). Among those with optimal baseline adherence, those with incident depression were nearly 2-times more likely to develop suboptimal adherence (Adjusted RR=1.8, 95% CI=1.1, 3.0) at follow-up.

Conclusion

Incident depression symptoms were associated with subsequent suboptimal HAART adherence. Ongoing aggressive screening for, and treatment of, depression may improve HAART outcomes.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, adherence, depression, longitudinal study, HIV, race

INTRODUCTION

Optimal adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is crucial to maximize the clinical benefits of treatment, delay disease progression, and to prevent the emergence and transmission of drug-resistant viruses. Although recent data suggest that boosted protease inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors are more forgiving than nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and non-boosted protease inhibitors,1, 2 adherence at levels of 95% or greater has long been recommended.3 Maintaining long-term adherence to HAART is difficult due to complex regimens, unpleasant side effects and because patients with HIV infection must take HAART consistently for the duration of their lives. Thus it is critical to identify modifiable factors that impede long-term adherence to HAART.

Depression may be just such a factor. Depression is prevalent among persons with HIV infection and has been linked to suboptimal adherence to HAART. In a nationally representative sample of US women and men with HIV infection participating in the HIV Costs and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS), 36% screened positive for major depression, and 26.5% for dysthymia,4 rates at least four times higher than in the general US population. Prevalence estimates of depression in persons with HIV infection vary depending on sample characteristics (e.g. demographic characteristics as well as the percentage with comorbid substance use), assessment technique and the definition of depression. Depression is also frequently under-diagnosed and untreated in persons with HIV infection,5 as well as in the general population in medical care.6 Some studies have also found that depression is also associated with more rapid disease progression in women and men with HIV infection.7, 8

While many cross-sectional studies have linked depression to suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy,9,10,11,12 others did not find an association.13,14 Although several cross sectional studies and a few longitudinal studies15,16,17,18 have found associations between depression and suboptimal adherence, the causal pathways relating depression to poor adherence remain unclear. In particular, few have examined whether onset of depression is associated with poorer adherence to HAART. One study found that an increase in average CESD depression symptom scores across a four-month follow-up period was associated with subsequent suboptimal adherence but baseline depression was not associated with later suboptimal adherence.15 We therefore examined the relationship between the onset of depression symptoms and changes in adherence to HAART in a sociodemographically diverse cohort of persons with HIV in Eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

METHODS

Participants

We used data from the Nutrition for Healthy Living (NFHL) Cohort, a longitudinal observational study investigating the nutritional and clinical status of adult women and men (≥18 years of age) with HIV infection in Boston, Massachusetts and Providence, Rhode Island. Participants were invited to take part in the study through newspaper and radio advertisements, and through physician networks in Boston, MA and Providence, RI. The methods of this study are described in detail elsewhere.19,20,21 The study protocol received Institutional Review Board approval at Tufts University and the Miriam Hospital. NFHL enrolled 881 participants from February 1995 through December 2004, who took part in semi-annual study visits. Excluded from the study were those diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, those who were pregnant at time of recruitment, had severe diarrhea, thyroid disease, malignancies other than Kaposi’s sarcoma, or were not fluent in English.

Sampling

Because the objective of the current analysis is to determine the relationship of change in depression symptom status to change in adherence to ART, this study included only participants on HAART who provided adherence information at four or more consecutive study visits and met the following additional criteria (n=225): Four consecutive study visits in a less than 2.5 year period, on HAART and providing adherence information at visits 1 or 2 and 3 or 4 in the four-visit interval, and no depression symptoms at either visit 1 or 2. Participants with missing values for both visit 1 and visit 4 adherence were removed from the subsample. In addition, participants with depression symptoms at any visit prior to the four selected consecutive visits were not included in this analysis..

Variables

Depression Symptoms

To assess depression symptoms we used Burnam’s interviewer-administered 8-item screening tool22 which includes six items from the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies in Depression scale (CES-D)23,24,25,26 and two items from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule.27,28 The Burnam screener is a widely-used measure29,30,31,32,33,34,35 initially developed for inclusion in the Medical Outcomes Study. It uses weighted scoring to maximize the prediction of DSM-III-defined depressive disorder from the eight items, which are included in Appendix A.36 Although it is a screener which is not sufficient for a clinical diagnosis depression, it has high sensitivity and specificity for current depression (0.89 and 0.95, respectively).22 As recommended in the original paper,22 participants scoring greater than or equal to.06 were classified as testing positive for depression symptoms. We classified participants as “developed depression symptoms” or “no depression symptoms,” based on their scores at four consecutive visits which were approximately 6 months apart. We defined participants who developed depression symptoms as having two visits with a negative screening test followed by two visits with a positive test. Participants in the comparison group (“No depression symptoms”) were those with four consecutive negative depression screening tests.

Adherence

At each visit, we measured adherence to antiretroviral therapy by first asking participants to identify all of the antiretroviral medications that were currently prescribed to them. For each medication, participants reported the number of days over the last seven days that they had missed a dose of that antiretroviral medication. We then added up across all medications the number of days missed and divided it by the sum of the number of eligible days (7 days for each medication they were prescribed). We calculated suboptimal adherence as the proportion of the 7 days prior to the study visit that the participant missed a dose of any of his or her prescribed medications. Self-reported suboptimal adherence was defined as missing at least 5% of HAART doses in the seven days prior to the study visit. To be eligible for this analysis, participants had to report adherence information at visit 1 or 2 and visit 3 or 4 of the four selected consecutive visits. For participants with missing adherence data on the first of their four sequential visits, visit 2 adherence was substituted as their baseline adherence. When participants had missing adherence data on the fourth visit of their four sequential visits, visit 3 adherence was used.

Covariates

We examined other demographic (gender, age in years, education level, race/ethnicity, poverty), psychosocial (instrumental social support, current illicit drug use), and clinical (HIV transmission category, HIV viral suppression, CD4 cell count, duration of HAART use, and symptoms) covariates that have been associated with adherence in prior studies.7 Poverty was defined as having a household income less than $10,000/year. Instrumental social support was measured using indicators from the HCSUS study which assessed how often people were available to give the respondent money when he or she needed it, and to help with daily chores if he or she was sick.37 We used a 13-item symptom scale similar to that used in the HCSUS study to measure the extent and severity of HIV-related symptoms.38 Participants were asked to endorse whether they experienced any of a list of HIV-related symptoms (e.g. severe or persistent headaches, white patches in mouth, painful rashes) and then evaluated on a 5 point scale (ranging from “not at all” to “extremely”) how much each endorsed symptom interfered with their normal activities. We calculated an aggregate symptom score for each participant (ranging from 0 to 100) from the responses. Viral suppression was defined as an HIV1 RNA count of less than or equal to 400 copies/mL.

Analysis

We conducted all analyses using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).39 We compared the characteristics at visit 1 of those who subsequently developed depression versus those who did not develop depression using χ2 tests for categorical variables, t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables. At visits 1 and 4 separately, we compared the proportion non-adherent in those who developed depression versus the comparison group using the χ2 test. Among those who were adherent at baseline (n-177), we estimated the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of non-adherence at follow-up of those who developed depression relative to those who did not using generalized estimating equations with a log link and the binomial distribution.40 Sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical variables were tested as possible confounders of the relationship between depression and non-adherence. Variables that were associated with suboptimal adherence at p≤ 0.2 in univariate models were included in multiple regression analyses.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of the 225 participants eligible for this analysis, 23% were female, 40% were non-white, and 89% were high school graduates (Table 1). Sixty-three percent had an undetectable viral load (<400) at the end of the four visit interval, and participants had been on HAART for an average of 3.2 years.

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics (n=225)

| Characteristic | All (n=225) | Developed Depression Symptoms (n=51) | Did not Develop Depression Symptoms (n=174) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age, in years, mean (SD) | 45 (7.4) | 42 (7.4) | 43 (7.5) | 0.33 |

| Female, n(%) | 51 (23) | 19 (37) | 32 (18) | 0.005 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n(%) | ||||

| African American | 64 (28) | 15 (29) | 49 (28) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 10 (4) | 5 (10) | 5 (3) | |

| White | 136 (60) | 28 (55) | 108 (62) | |

| Other | 15 (7) | 3 (6) | 12 (7) | 0.19 |

| High School Graduate, n(%) | 200 (89) | 43 (84) | 157 (90) | 0.08 |

| Annual Income<$10,000, n(%) | 89 (41) | 29 (58) | 60 (36) | 0.005 |

| HIV Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| HIV Transmission Category, n(%) | ||||

| MSM only | 121 (55) | 18 (37) | 103 (60) | |

| Any IDU | 47 (21) | 14 (29) | 33 (19) | |

| Heterosexual | 47 (21) | 15 (31) | 32 (19) | |

| Other | 5 (3) | 2 (4) | 3 (2) | 0.06 |

| HIV Viral Load <400 (undetectable) at visit 1(copies/mL) (n=218), n(%) | 125 (57) | 25 (53) | 100 (58) | 0.33 |

| HIV Viral Load <400 (undetectable) at visit 4(copies/mL) (n=212), n(%) | 133 (63) | 29 (60) | 104 (63) | 0.84 |

| CD4 Cell Count at visit 1, % | ||||

| <200 | 48(21) | 11(22) | 37 (21) | |

| 200–500 | 102(46) | 16(32) | 86 (50) | |

| >500 | 73(33) | 23(46) | 50 (29) | 0.05 |

| CD4 Cell Count at visit 4,% | ||||

| <200 | 41(19) | 9(18) | 32 (19) | |

| 200–500 | 94(43) | 21(43) | 73 (43) | |

| >500 | 83(48) | 19(39) | 64(38) | 0.99 |

| Duration of HAART use (in months) at visit 4, mean(SD) | 38.4 (17.5) | 44.1 (21.6) | 37 (15.7) | 0.06 |

| 13 item symptom score first visit, median (IQR) | 12.5 (5, 21.3) | 15 (10, 29) | 11.2 (5.0, 20.0) | 0.01 |

| 13 item symptom score fourth visit median (IQR) | 11.7 (5, 20) | 18.3 (12.3, 30.8) | 8.8 (3.8,16.9) | 0.0001 |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Current drug use (excluding marijuana only users), n(%) | 28 (12) | 8 (16) | 20 (12) | 0.73 |

| Psychosocial Characteristics | ||||

| Instrumental Social Support, median (IQR) | 73.3 (50, 100) | 53.3 (26.7, 80) | 80 (60, 100) | 0.0001 |

| Affective Social Support, median (IQR) | 67.5 (55, 80) | 67.5 (47.5, 77.5) | 67.6 (57.5, 80) | 0.2 |

Correlates of developing depression symptoms

Among the 225 without depressive symptoms at the first two selected visits, fifty-one (22%) developed depression symptoms at visits three and four (Table 1). Those who developed depressive symptoms, compared to those without depressive symptoms, were more likely to be women (37% vs. 18%, p=0.005), have an annual household income of less than $10,000 (58% vs. 36%, p=0.005), have a baseline CD4 count greater than 500 (46% vs 29% p=0.05), have higher median symptom scores (18.3 vs. 8.8, p=0.0001), and lower median levels of instrumental social support (53.1 vs. 80, p=0.0001).

Rates and correlates of suboptimal adherence

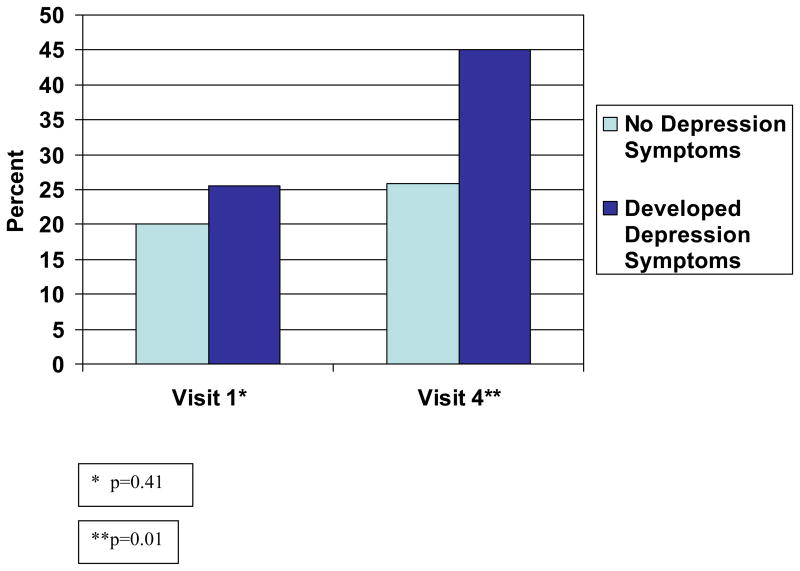

The proportion of participants with suboptimal adherence at baseline (visit 1 or 2) was similar among those that developed depression symptoms and those that did not develop depression symptoms (25.5% and 20.1%, respectively, p=0.41). In contrast, those who developed depression symptoms were more likely than the comparison group to report suboptimal adherence at follow-up (45.1% vs. 25.9%, p=0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion with suboptimal adherence at visit 1 and visit 4 by depression symptom status

Across the four-visit period, 137 (61%) were adherent at baseline and follow-up (maintained adherence), 20 (9%) had suboptimal adherence at baseline and became adherent at follow-up, 40(18%) were adherent at baseline and had suboptimal adherence at follow-up, and 28 (12%) had suboptimal adherence at both baseline and follow-up. Among the 177 adherent at baseline, 34% of those developing depression symptoms had suboptimal adherence at follow-up, compared to 19% of those without depression symptoms (p=.05).

The correlates of suboptimal adherence at visit four among those who were adherent at visit 1 (n=177) are shown in Table 2. In univariate analysis developing depression symptoms was significantly associated with suboptimal adherence at follow-up (RR=1.7, 95% CI=1.0, 3.1). Other variables that were significantly associated with suboptimal adherence included female sex (RR=2.2, 95% CI=1.3 to 3.7) and African American race (RR=2.0, 95% CI=1.2, 3.5). Poverty was marginally associated with suboptimal adherence. Age, education, viral load, CD4 count, duration of HAART use, symptom score, instrumental social support and current drug use were not associated with suboptimal adherence.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Non-Adherence to HAART at Visit 4 among participants adherent at Visit 1 (n=177)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Developed depression symptoms | 1.7 (1.0, 3.1) | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) |

| Age (in years) | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) | -- |

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | 2.2 (1.3, 3.7) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.9) |

| Race/ethnicity (Black vs. White, Hispanic, Other) | 2.0 (1.2, 3.5) | 1.9 (1.2, 3.3) |

| Education level (High School Graduate vs. no) | 2.2 (0.6, 8.2) | -- |

| Income<$10,000 (below poverty line vs. no) at visit 4 | 1.5 (0.9, 2.6) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.0) |

| Duration of HAART use (in months) at visit 4, mean, (SD) | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) | -- |

| 13 item symptom score first visit | 1.0 (0.9, 1.0) | -- |

| 13 item symptom score fourth visit | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) | -- |

| Current Drug use (excluding marijuana only users) | 1.3 (0.6, 2.7) | -- |

| Instrumental Social Support | 0.9 (0.9,1.0) | -- |

In the multivariate model (Table 2), those developing symptoms of depression at follow-up had a nearly two fold greater risk of suboptimal adherence at follow up (RR=1.8, 95% CI=1.1, 3.0), adjusted for gender, race, and income. African American race was a significant independent determinant of developing suboptimal adherence (RR=1.9, 95% CI=1.2, 3.3).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of women and men with HIV infection, we found that incident depression symptoms were associated with subsequent suboptimal adherence. We also found a relatively high incidence of depression symptoms. Our finding that 22% of women and men with HIV infection and no previous depression symptoms developed depression symptoms at follow-up is high. It underscores the importance of ongoing screening for and attention to depression among women and men with HIV infection.

This is the first report that we are aware of that examines the effect of incident depression symptoms on adherence in persons with HIV. Spire et al. (2002) found that a change in median CESD scores over a four month period was associated with non-adherence over the same time period, but because they measured changes in CESD scores, it is not possible to know how many people at each time point had major depression. In a study of men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) depression at the start of a six month interval was associated with a decline in adherence over the subsequent six months, but it was not true that the absence of depression was associated with improved adherence (Kleeberger, 2004). Carrieri et al. (2003) found that baseline depression was associated with an inability to maintain adherence at 18 months follow-up in a cohort of injection drug users initially adherent to ARV treatment in France. Our study extends the findings of these previous longitudinal studies, by demonstrating that onset of depression symptoms is associated with increasing rates of suboptimal adherence.

A meta-analysis of depression and adherence to medical care regimens in general (not only HIV ARVs) found that patients with depression had a three-fold higher odds of poor adherence and suggested possible mechanisms linking depression to poor adherence to medical treatments.41 Included in these possible mechanisms were: the feeling of hopelessness which often accompanies depression, social isolation and an absence of social support.15 Any or all of these mechanisms may be operative in individuals with HIV infection. It has been shown that the presence of social support and other psychosocial resources have been associated with increased survival in women with HIV infection42; improved survival may be a result of improved adherence.

African Americans in our study had a higher risk of decline in adherence over time compared with whites. In contrast, Kleeberger et al. (2004) found that African American race was not associated with a decline in adherence among those with perfect adherence, but did predict continued suboptimal adherence among patients who already had poor adherence, while white race predicted later improvements in adherence in those with poor adherence. Some cross-sectional studies have identified an association between African American race and suboptimal adherence to HAART and others have not.9 Although several studies have highlighted this association, further research is needed to identify the mechanisms by which race and adherence may be related. Studies investigating racial disparities in health care have identified patient-level factors including lack of trust in health care providers and the health care system, and provider-level factors, including unfair treatment, discrimination43 or other aspects of the quality of the doctor-patient relationship, as well as structural factors (e.g., inadequate access to or lower quality of care) which could contribute to racial disparities in adherence. It could also be that unmeasured variables such as skepticism about the efficacy of antiretrovirals, or distrust in the provider or health care system contribute to the findings we observed.

A strength of this study is our stringent criteria for classification of depression based on two visits without depression symptoms followed by two visits with depression symptoms, which makes it more possible to establish a clear temporal relationship between depression symptoms and changes in adherence. There are some study limitations. First, we assessed adherence to HAART through participant self-report, so rates of adherence may be overestimates.44,45 Second, the conservative cutoff we used for depression symptoms, which required screening positive for depression symptoms at two consecutive visits may have missed some people who may have had diagnosable depression at just one visit. Third, this study did not include all possible profiles of depression symptom transitions over the four study visits. For example, participants who reported depression symptoms at all four visits were not included in this analysis. The effects of chronic depression are likely different from those of incident depression. Fourth, although it is possible that prior poor adherence contributed to onset of depression symptoms which in turn contributed to worse adherence, this is clinically unlikely. Furthermore, visit 1 non-adherence was not associated with subsequent development of depression symptoms. Finally, it was not possible to analyze the contribution of treatment for depressive symptoms to adherence outcomes.

The results from this study highlight that in persons with HIV infection, the relationship of depressive symptoms to HAART adherence is dynamic rather than static. Our finding that depression symptom onset is associated with a change to suboptimal adherence supports the need for further research to evaluate the impact of treatment for depression on adherence to HAART. Depression can be effectively treated with medications in patients with HIV infection.46 Some studies have found that mental health therapy with and without anti-depressant medication leads to an increase in HAART utilization in women with HIV infection.47 In addition, some studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in improving adherence.46, 48, 49 Further research is needed to evaluate the impact of psychosocial and pharmacological treatment interventions for depression on clinical outcomes in patients with HIV and to identify interventions that prevent worsening adherence or improve adherence over time.

The results from this study also underscore the importance of ongoing aggressive screening for depression in order to intervene to improve mental health and HAART adherence in patients with HIV infection. For screening to be cost effective and have an impact, it is critical to strengthen referral systems to ensure appropriate treatment of and follow up for depression for patients with HIV and depression, not only because it may improve adherence as well as HAART outcomes, but because of its potential impact on quality of life overall.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This work was supported by NIDDK (1P01DK45734-06), the General Research Center of the Tufts-New England Medical Center (M01-RR00054), the Tufts Center for Drug Abuse and AIDS Research (P30 DA013868), the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research (P30A142853), and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (5R01HL065947). At the time of this study, Dr. Kacanek received support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (T32 AI07438). Dr. Wilson also was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-oriented Research (K24 RR020300).

The authors wish to thank James Fauntleroy and Sally Skinner for SAS programming advice and support; and the women and men who participated in the Nutrition for Healthy Living Study, as well as the NFHL research team for their valuable contributions. These data were presented at the International AIDS Conference in 2006 in Toronto, Canada.

Appendix A: Burnam Depression Screener Items

In the past year, have you had 2 weeks or more during which you felt sad, blue, or depressed; or when you lost all interest or pleasure in things that you usually cared about or enjoyed? (1=Yes/0=No)

-

Have you had 2 years or more in your life when you felt depressed or sad most days, even if you felt okay sometimes? (1=Yes/0=No) If not go to question 3.

2a. Have you felt depressed or sad much of the time in the past year? (1=Yes/0=No)

-

For each statement below, mark one circle that best describes how much of the time you felt or behaved this way during the past week. Response options are:

0: Rarely or None of the time (less than one day)

1:Some or a little of the time (1–2 days)

2:Occasionally or moderate amount of the time (3–4 days)

-

3: Most or all of the time (5–7 days)

During the past week:

I felt depressed

I had crying spells

I felt sad

I enjoyed life [reverse scoring]

My sleep was restless

I felt that people disliked me

Footnotes

The first two items are from the DIS and are most strongly related to the criterion measure, the full DIS.

References

- 1.Bangsberg DR, Acosta EP, Gupta R, et al. Adherence-resistance relationships for protease and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors explained by virological fitness. AIDS. 2006;20(2):223–231. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000199825.34241.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maggiolo F, Airoldi M, Kleinloog HD, et al. Effect of adherence to HAART on virologic outcome and on the selection of resistance-conferring mutations in NNRTI- or PI-treated patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2007;8(5):282–292. doi: 10.1310/hct0805-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bing EG, Burnam AM, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asch SM, Kilbourne AM, Gifford AL, Burnam MA, Turner B, Shapiro M, Bozzette SA for the HCSUS Consortium. Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV: Who are we missing? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:450–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, et al. The usual care of major depression in primary care practice. Archives of Family Medicine. 1997;7:334–339. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum E, Schuman P, Boland RJ, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women. JAMA. 2001;285:1466–1475. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, Laurenceau JP, Balbin E, Limas N, Schneiderman N, Solomon G. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67 (6):1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ammassari A, Antinori A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli L, et al. Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:394–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Duran RE, Fernandez MI, McPherson-Baker S, et al. Social support, positive status of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 2004;23:413–418. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuman P, Ohmit SE, Cohen M, Sacks HS, Richardson J, Young M, et al. Prescription of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women with AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:371–478. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordillo V, del Amo J, Soriano V, Gonzalez-Lahoz J. Sociodemographic and psychologic variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13(13):1763–1769. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner BJ, Laine C, Cosler L, et al. Relationship of gender, depression, and health care delivery with antiretroviral adherence in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:248–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone VE, Hogan JW, Schuman P, et al. Antiretroviral regimen complexity, self-reported adherence, and HIV patients’ understanding of their regimens: survey of women in the HER study. JAIDS. 2001;28:124–31. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200110010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spire B, Duran S, Souville M, Leport C, Raffi F, Moatti J the APROCO cohort study group. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) in HIV-infected patients: from a predictive to a dynamic approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:1481–1496. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrieri MP, Chesney MA, Spire B, Loundou A, Sobel A, Lepeu G, Moatti JP the MANIF Study Group. Failure to maintain adherence to HAART in a cohort of French HIV-Positive Injecting Drug Users. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1001_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleeberger CA, Buechner J, Pelella F, Detels R, Riddler S, Godfrey R, Jacobson LP. Changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy medications in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS. 2004;18:683–688. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy DA, Belzer M, Durako SJ, Sarr M, Wilson C, Muenz LR. Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research network. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with Human Immunodeficiency virus. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(8):764–770. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson IB, Roubenoff R, Knox TA, et al. Relation of lean body mass to health-related quality of life in persons with HIV. JAIDS. 2000;24:137–146. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shevitz AH, Knox TA, Spiegelman D, et al. Elevated resting energy expenditure among HIV-seropositive persons receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:1351–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907300-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva M, Skolnick P, Gorbach S, Spiegelman D, Wilson IB, Fernandez-Difranco MG, Knox T. The effect of protease inhibitors on weight and body composition in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1998;12(13):1645–51. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burnam MA, Wells KB, Leake B, Landsverk J. Development of a brief screening instrument for detecting depressive disorders. Medical Care. 1988;26(8):775–89. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LN. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. App Psychol Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(3):203–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers JK, Weissman MM. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(9):1081–1084. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a START*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Ratcliff KS, Seyfried W. Validity of the diagnostic interview schedule, version II:DSM-II diagnoses. Psychol Med. 1982;12(4):855–870. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman AM. Social relations and depressive symptoms in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(2):247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahluwalia JS, Richter K, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia HK, Choi WS, Schmelzle KH, et al. African American smokers interested and eligible for a smoking cessation clinical trial: predictors of not returning for randomization. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(3):206–212. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hlatky MA, Boothroyd D, Vittinghoff E, Sharp P, Whooley MA. Quality of life and depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women after receiving hormone therapy: Results from the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) trial. JAMA. 2002;287(5):591–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz DA, McHorney CA. The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(3):229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foy CG, Wickley KL, Adair N, Lang W, Miller ME, Rejeski WJ, et al. The Reconditioning Exercise and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Trial II (REACT II): Rationale and study design for a clinical trial of physical activity among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27(2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, Aragaki A, Cochrane BB, Brunner RL, et al. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sivarajan Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Chritopherson DJ, Martin K, Parker KM, Amonetti M, et al. High rates of sustained smoking cessation in women hospitalized with cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Initiative for Nonsmoking (WINS) Circulation. 2004;109(5):587–593. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115310.36419.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isaac R, Jacobson D, Wanke C, Hendricks K, Knox TA, Wilson IB. Declines in dietary macronutrient intake in persons with HIV who develop depression. Public Health Nutr. 2008 Feb;11(2):124–31. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crystal S, Akincigil A, Sambamoorthi U, et al. The diverse older HIV-positive population: A national profile of economic circumstances, social support, and quality of life. JAIDS. 2003;33:S76–S83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hays RD, Spritzer KL, McCaffrey D, Cleary PD, Collins R, Sherbourne C, et al. The HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS) measures of health-related quality of life. Santa Monica: RAND; 1998. DRU-1997-AHCPR. [Google Scholar]

- 39.SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC.

- 40.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;162(3):199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for non-compliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ickovics J, Milan S, Boland R, Schoenbaum E, Schuman P, Vlahov D for the HERS Study Group. Psychological resources protect health: 5-year survival and immune function among HIV-infected women from four US cities. AIDS. 2006;20(14):1851–60. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000244204.95758.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bird ST, Bogart LM, Delahunty DL. Health-related correlates of perceived discrimination in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Chang CJ, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: Comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33:1417–1423. doi: 10.1086/323201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, Golin CE, Miller LG, Hays RD, Beck CK, Sanandai S, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:968–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-10-200105150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olatunji BO, Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA. A review of treatment studies of depression in HIV. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2006;14(3):112–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook JA, Grey D, Burke-Miller J, et al. Effects of treated and untreated depressive symptoms on highly active antiretroviral therapy use in a US multi-site cohort of HIV-positive women. AIDS Care. 2006;18(2):93–100. doi: 10.1080/09540120500159284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safren S, Hendriksen E, Mayer K, Mimiaga M, Pickard R, Otto M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for HIV medication adherence and depression. Cogn Behav Pract. 2004;11:415–23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, Mayer KH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]