Abstract

Pattern completion, the ability to retrieve complete memories on the basis of incomplete sets of cues, is a crucial function of biological memory systems. The extensive recurrent connectivity of the CA3 area of hippocampus has led to suggestions that it might provide this function. We have tested this hypothesis by generating and analyzing a genetically engineered mouse strain in which the N-methyl-D-asparate (NMDA) receptor gene is ablated specifically in the CA3 pyramidal cells of adult mice. The mutant mice normally acquired and retrieved spatial reference memory in the Morris water maze, but they were impaired in retrieving this memory when presented with a fraction of the original cues. Similarly, hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells in mutant mice displayed normal place-related activity in a full-cue environment but showed a reduction in activity upon partial cue removal. These results provide direct evidence for CA3 NMDA receptor involvement in associative memory recall.

In both humans and animals, the hippocampus is crucial for certain forms of learning and memory (1, 2). Anatomically, the hippocampus can be divided into several major areas: the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 (3). In area CA3, the pyramidal cells, which project to CA1 pyramidal cells via Schäffer collaterals, receive excitatory inputs from three sources: the mossy fibers of the dentate gyrus granule cells, the perforant path axons of the stellate cells in the superficial layers of the entorhinal cortex, and the recurrent collaterals of the CA3 pyramidal cells themselves, which are the most numerous type of input to the CA3 pyramidal cells (4). The prominence of these recurrent collaterals has led to suggestions that CA3 might serve as an associative memory network. Associative networks, in which memories are stored through modification of synaptic strength within the network, are capable of retrieving entire memory patterns from partial or degraded inputs, a property known as pattern completion (5–10). In CA3, the strength of the recurrent collateral synapses along with perforant path synapses can be modified in an NMDA receptor (NR)–dependent manner (11–14). In this study, we have examined the role of these synapses in memory storage, retrieval, and pattern completion by generating and analyzing a mouse strain in which the NMDAR subunit 1 (NR1) is specifically and exclusively deleted in the CA3 pyramidal cells of adult mice.

CA3 NMDA receptor knockout mice

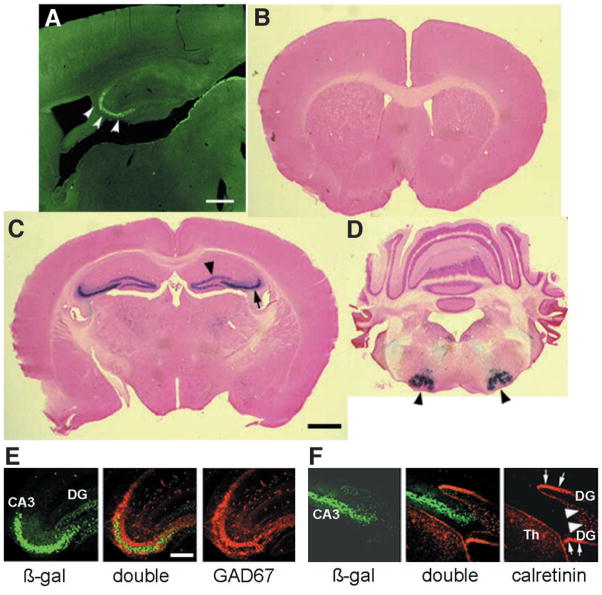

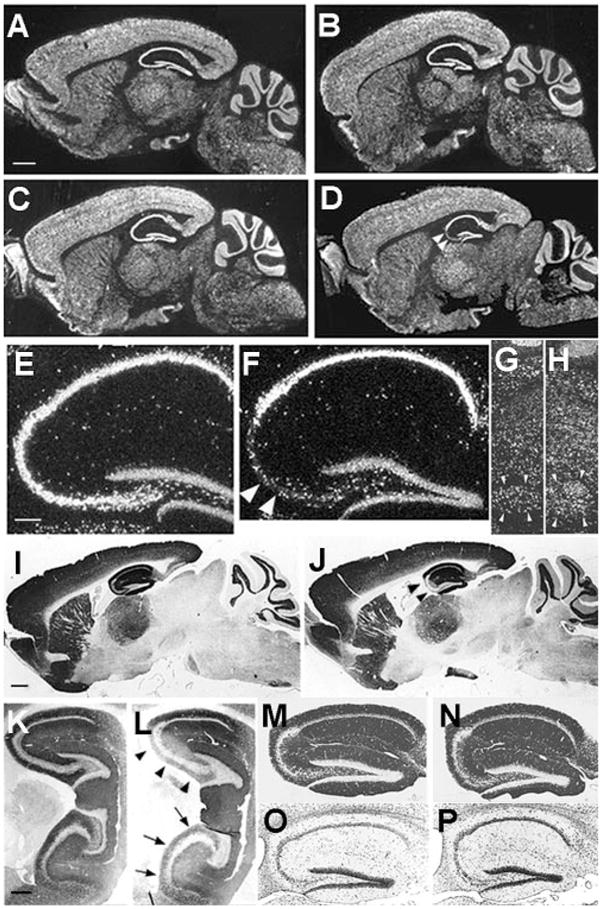

To generate CA3 pyramidal cell–specific NR1 knockout mice (CA3-NR1 KO mice), we used the bacteriophage P1–derived Cre/loxP recombination system (15). Because the CA3 pyramidal cell layer is a robust site of expression of KA-1, one of the kainate receptor subunits (16), we created transgenic mice in which the transcriptional regulatory region of the KA-1 gene drives the expression of the Cre transgene (17). In one transgenic line (G32-4), the level of Cre immunoreactivity (IR) was robust in the CA3 pyramidal cell layer in mice older than 4 weeks of age (17) (Fig. 1A). The spatial and temporal pattern of Cre/loxP recombination in the G32-4 Cre transgenic mouse line was examined by crossing it with a lacZ reporter mouse (Rosa26) and staining brain sections derived from the progeny with X-gal (17) (Fig. 1, B to D). Cre/loxP recombination was first detectable at postnatal day 14 in area CA3 of the hippocampus. At 8 weeks of age, recombination had occurred in nearly 100% of pyramidal cells in area CA3 (Fig. 1C). Recombination also occurred in a few other brain areas, but at distinctly lower frequencies: in about 10% of dentate gyrus (Fig. 1C) and cerebellar granule cells (Fig. 1D) and in about 50% of cells in the facial nerve nuclei of the brain stem (Fig. 1D). Recombination frequency did not change in older mice. No recombination was detected in the cerebral cortex or in the hippocampal CA1 and sub-icular regions (Fig. 1, B to D). We determined the type of the recombination-positive cells in the hippocampus with double immunofluorescence staining using a set of antibodies specific for β-galactosidase (a marker for the Cre/loxP recombination), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD)-67 (a marker for interneurons), and calretinin (a marker for dentate gyrus mossy cells in the mouse hippocampus) (17, 18). Minimal overlapping staining was observed with antibodies against β-galactosidase and GAD67 (Fig. 1E) and with antibodies against β-galactosidase and calretinin (Fig. 1F). These results indicate that in area CA3 and the dentate gyrus, Cre/loxP recombination is restricted to the pyramidal cells and the granule cells, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of Cre immunoreactivity and Cre/loxP recombination in G32-4 mice. (A) A parasagittal Vibratome section from the brain of a 4-week-old male G32-4 mouse was stained with a rabbit antibody against Cre, and Cre IR was visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate. Arrowheads, CA3 pyramidal cell layer. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B to D) Coronal sections from the brain of an 8-week-old male G32-4/Rosa26 double-transgenic mouse stained with X-gal and Nuclear Fast Red. In forebrain (B and C), arrow, CA3 cell layer; arrowhead, dentate granule cell layer. In hindbrain (D), arrowheads, facial nerve nuclei. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E and F) Parasagittal hippocampal sections from the brain of an 8-week-old G32-4/Rosa26 double-transgenic mouse subjected to double immunofluorescence staining with (E) antibodies against β-galactosidase (visualized by Alexa488) and GAD67 (visualized by Cy3), or (F) with antibodies against β-galactosidase and calretinin (visualized by Cy3). Green, β-galactosidase IR; red in (E) GAD67-IR; red in (F), calretinin-IR. DG, dentate gyrus; Th, thalamus; white arrows, somata of mossy cells; white arrowheads, axon terminals of mossy cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

We crossed the G32-4 mice with floxed-NR1 (fNR1) mice (15, 17) in order to restrict the NR1 knockout to those cell types targeted by the G32-4 Cre transgene. Floxed refers to a genetic allele in which a gene or gene segment is flanked by loxP sites in the same orientation; Cre recombinase excises the segment between the loxP sites. Homozygous floxed, Cre-positive progeny (CA3-NR1 KO) were viable and fertile, and they exhibited no gross developmental abnormalities. In situ hybridization data (17) suggested that in the CA3 pyramidal cell layer of these mice, the NR1 gene is intact until about 5 weeks of age, starts being deleted thereafter, and is nearly completely deleted by 18 weeks (white arrowheads in Fig. 2D) of age (Fig. 2, A to D). There was no indication of deletion of the NR1 gene elsewhere in the brain throughout the animal’s life. Specifically, the NR1 gene seemed to be intact in granule cells of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 2, E and F) and the cerebellum (Fig. 2, A to D), as well as in the facial nerve nuclei (Fig. 2, G and H). These results are in contrast to the Cre/loxP recombination–dependent expression of the lacZ gene (see Fig. 1, C and D), likely due in part to differences in the sensitivity of detection of the Cre/loxP recombination and in part to differences in the susceptibility of the loxP substrates to the recombinase.

Fig. 2.

Distributions of NR1 mRNA, NR1 protein, and other proteins in brains of CA3-NR1 KO mice. (A to H) Dark field images of in situ hybridization on parasagittal brain sections with a 33P-labeled NR1 cRNA probe. The sources of the brains were (A) a 5-week-old male fNR1 control; (B) a 5-week-old male mutant [a littermate of the mouse in (A)]; (C, E, and G) an 18-week-old male fNR1 control; (D, F, and H) an 18-week-old male mutant [a littermate of the mouse in (C), (E), and (G)]. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E and F) The hippocampal regions of (C) and (D), respectively, are enlarged. (G and H) The areas of the facial nerve nuclei are enlarged. In the CA3 pyramidal cell layer of the mutant, the level of NR1 mRNA was normal until 5 weeks of age, started to decline thereafter, and reached the lowest and stable level by 18 weeks of age [arrowheads in (D)]. There was no indication of a reduced NR1 mRNA level in the mutant mice relative to the control littermates in any other brain area throughout the postnatal development. In particular, the levels of NR1 mRNA in the mutants’ dentate gyrus (F), cerebellum (B and D), and the facial nerve nuclei (H) are indistinguishable from those of the control littermates (A, C, E, and G). (F) Arrowheads indicate scattered hybridization signals that are likely derived from CA3 interneurons. (G and H) Arrowheads, the facial nerve nuclei. In (E) to (H), scale bar, 25 μm. (I to N) Immunoperoxidase staining of paraffin sections of brains derived from 18-week-old male mice visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. The primary antibodies used are specific for NR1 (I to L) and for GluR1 (M and N). The genotypes of the mice are fNR1 (control) (I, K, M), and CA3-NR1 KO (mutant) (J, L, N). Medial parasagittal sections were used for experiments other than those in (K) and (L), for which lateral parasagittal sections were used. In the mutants, NR1-IR was selectively deficient in the dorsal [arrowheads in (J) and (L)], as well as ventral [arrows in (L)] area CA3. Scale bar in (I), 100 μm. (K to P) See scale bar in (K), 50 μm. (O and P) Nissl staining of hippocampal sections derived from an 18-week-old male fNR1 mouse (O) and a male CA3-NR1 KO littermate (P). The mutant exhibited no gross morphological alteration.

Performing NR1-immunocytochemistry with an antibody against the COOH-terminus of mouse NR1 (17) confirmed that the selective and late-onset deletion of the NR1 gene in the CA3 region of the mutant mice resulted in loss of the protein. The protein distribution was normal for the first 7 weeks after birth. By the 18th postnatal week, however, NR1 protein had disappeared from both the apical and basal dendritic areas in the CA3 region (Fig. 2, I to L). In contrast, normal levels of NR1 protein were maintained in the CA1 region and the dentate gyrus of the 18-week-old mutant mice. The reduction of NR1 protein in the CA3 region was observed in both dorsal and ventral hippocampus (Fig. 2, K and L), suggesting that the NR1 gene is deleted uniformly along the longitudinal axis of the hippocampus.

We carried out a set of immunocytochemical and cytochemical experiments to investigate the integrity of the cytoarchitecture of the mutant hippocampus (17). No significant differences could be detected in the patterns of post-synaptic density-95 (PSD-95) (19) or GluR1 [αamino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazol propionate (AMPA)-type glutamate receptor subunit 1] expression (Fig. 2, M and N). Also normal was the IR distribution of calbindinD28k, a Ca2+-binding protein expressed at high levels in dentate gyrus granule cells but not in cells in the CA3 region, suggesting that mossy fibers from dentate gyrus granule cells project normally to their target in the CA3 region (the stratum lucidum) (19). Nissl staining did not reveal any obvious abnormalities (Fig. 2, O and P). We also used the Golgi-impregnation technique to assess dendritic structures and found no significant differences between the mutant and the fNR1 control mice (24 weeks of age) with respect to the dendritic length, the number of dendritic branching points, or the spine density of CA3 pyramidal cells (20).

Thus, in the mutant mice, the NR1 gene is selectively deleted in the CA3 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus. This deletion occurs only in adult mice (older than 5 weeks of age) and does not affect the hippocampal cytoarchitecture.

NMDA receptor activation

To evaluate whether functional NRs are present in CA3 pyramidal cells in CA3-NR1 KO mice, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on visually identified cells in freshly prepared hippocampal slices obtained from adult fNR1 control and mutant mice (17). We compared the basic intrinsic properties and synaptically evoked responses of CA3 and CA1 pyramidal cells. In all but two experiments, the experimenters were blind to whether the animals were control or mutant mice. There were no differences in the intrinsic properties of CA3 pyramidal cells in control (n = 14) or mutant mice (n = 23) [resting membrane potential (RMP): control, −67.0 ± 2.0 mV; mutant, −67.8 ± 1.6 mV; input resistance (RN): control, 200.8 ± 17.9 MΩ; mutant, 183 ± 12.6 MΩ]. Similarly, RMP and RN did not differ for CA1 pyramidal cells in control and mutant mice (RMP: control, n = 7, −62.3 ± 1.4 mV; mutant, n = 12, −62.3 ± 0.7 mV; RN: control, 189.8 ± 30.0 MΩ; mutant, 171.1 ± 10.8 MΩ).

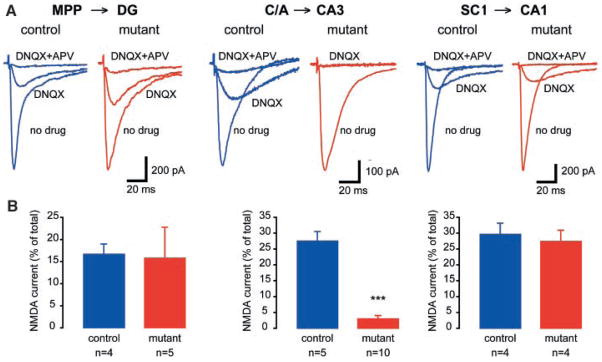

We next isolated synaptically evoked NMDA currents (17) (Fig. 3). At the medial perforant path (MPP)–dentate gyrus (DG) synapse, there were no differences in the 6-cyano-7-dinitroquinoxalline-2,3-dione (DNQX)-insensitive component of the total synaptic current (control, 15.8 ± 7%, n = 5; mutant, 16.7 ± 2.3%, n = 4; P = 0.96; Fig. 3B). A similar relationship was observed at the Schäffer collateral (SC)-CA1 synapse (control, 26.7 ± 6%, n = 4; mutant, 29.3 ± 4%, n = 4; P = 0.78) (Fig. 3B). However, consistent with the immunohistochemical characterization of an absence of NR1 in CA3-NR1 KO mice, the DNQX-insensitive component was significantly reduced at the recurrent commissural/associational (C/A) synapse in the mutant animals relative to controls (control, 27.5 ± 3%, n = 10; mutant, 3.0 ± 1%, n = 5; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

NMDAR function is absent only in the C/A-CA3 pathway of CA3-NR1 KO mice. (A) Synaptic responses were evoked and NMDA currents pharmacologically isolated. Details in the Materials and Methods section (17). (Left) Representative data from a control (fNR1) dentate gyrus granule cell (DG) showing a medial perforant path evoked NMDA current (isolated with DNQX and blocked by APV ). (Middle) C/A-evoked NMDA current. (Right) In a CA1 pyramidal cell, SC stimulation-elicited NR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic current. (B) Summary data for NMDA currents in fNR1 and mutant animals (***P < 0.0001).

We also tested the prediction that long-term potentiation (LTP) would be impaired at C/A–CA3 synapses in CA3-NR1 KO mice (Fig. 4). At the mossy fiber–CA3 synapse (MF-CA3), in which LTP does not depend on NR activation (11–14), there was no significant difference in the induction or expression of LTP between control and mutant mice (control, 265 ± 39%, n = 5; mutant, 259 ± 45%, n = 6). Additionally at the SC-CA1 synapse, where NRs were intact, LTP was similar in both groups of animals (control, 232 ± 37%, n = 9; mutant, 219 ± 53%, n = 10). Similarly, in control animals, LTP was induced at C/A-CA3 synapses in all the animals examined (202 ± 28%, n = 5). In contrast, LTP was nearly absent at C/A-CA3 synapses in 9 out of 11 CA3-NR1 KO mice (101 ± 11%, n = 11). In two cases, we observed LTP, which may have been due to calcium influx from voltage-dependent calcium channels. These data provide functional evidence that NR1 knockout in CA3 pyramidal cells selectively disrupts NR-dependent LTP in CA3 at the recurrent C/A synaptic input, but not NR-independent mossy fiber LTP in CA3 or NR-dependent LTP in area CA1.

Fig. 4.

NMDA-dependent LTP at the recurrent CA3 synapses in CA3-NR1 KO mice. (A) Representative waveforms (averages of five consecutive responses recorded at 0.05 Hz) show that C/A-CA3 LTP was selectively prevented in mutant animals. (B) Summary graphs showing the time course of potentiation after three long trains of stimulation (100 pulses at 100 Hz concomitant with a 1-s depolarizing pulse 1 train every 20 s). (C) Cumulative probability plots; each point represents the magnitude of change relative to baseline (abscissa) as a cumulative fraction of the total number of experiments (ordinate) for a given experiment 20 to 25 min (average) after high-frequency stimulation. EPSP, excitatory postsynaptic potential.

Spatial reference memory

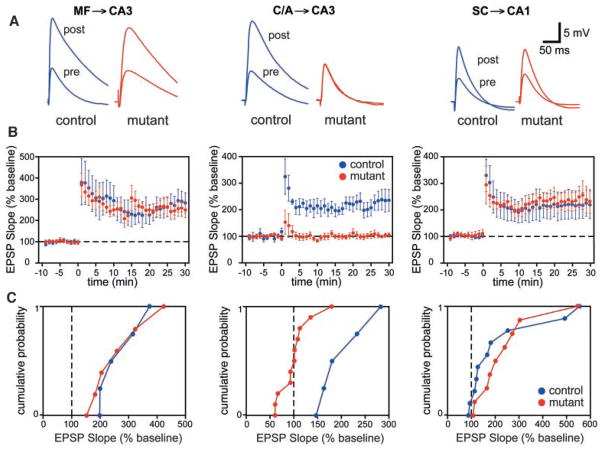

We subjected the CA3-NR1 KO mice and their control littermates to the hidden platform version of the Morris water maze task (17, 21) to assess the effect of the selective ablation of NRs in CA3 pyramidal cells on the animals’ ability to form a spatial reference memory. No significant differences were observed between the control and mutant mice in the escape latency, path length, average swimming velocity, or wall-hugging time (Fig. 5, A to D). We subjected the mutant, fNR1, Cre, and wild-type littermates to a probe trial on day 2 (P1), day 7 (P2), and day 13 (P3), and assessed spatial memory by monitoring the relative radial-quadrant occupancy (Fig. 5E). There was no difference in the acquisition rate of spatial learning among the four genotypes. By day 13 (P3), all four mouse strains spent significantly more time in the target radial-quadrant than in any of the nontarget quadrants. This result for three types of mice was also shown by the criterion of absolute platform occupancy (Fig. 5F). Thus, the selective ablation of NRs in adult hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells has no detectable effect on the animal’s ability to form and retrieve spatial memory as determined by the standard hidden platform version of the Morris water maze task. Further, the CA3-NR1 KO mice are not impaired in motivation, motor coordination, or the sensory functions required to carry out this spatial memory task.

Fig. 5.

Performance of CA3-NR1 KO mice in the standard Morris water maze task and recall capability under various cue conditions. (A to D) 18- to 24-week-old male CA3-NR1 KO mice (mutant, red, n = 44), fNR1 (blue, n = 37), Cre (n = 14, not shown), and their wild-type littermates (green, n = 11) were subjected to training trials under full-cue conditions. The four types of mice did not differ significantly in (A) escape latency, (B) distance traveled, (C) swimming velocity, or (D) time spent near the pool wall [genotype effect for each measure, F(3,102) < 2.5, P > 0.05; genotype x trial interaction for each measure, P > 0.05]. (E) Probe trials on day 2 (P1, open bars), day 7 (P2, hatched bars), and day 13 (P3, solid bars) under full-cue conditions, monitored by relative radial-quadrant occupancy [time (%) the mice spent in the target radial-quadrant relative to the total time spent in the four radial-quadrants]. On day 13, all the genotypes spent significantly more time in the target radial-quadrant than other quadrants [wild, F(3,40) = 84.1, P < 0.0001; Cre, F(3,52) = 52.7, P < 0.0001; fNR1, F(3,144) = 130.4, P < 0.0001; mutant, F(3,172) = 163.4, P < 0.0001; Newman-Keuls post hoc comparison (the trained quadrant compared to all the other quadrants); P < 0.01 for all genotypes]. (F) Day 13 probe trial (P3) of randomly selected subsets of Cre (n = 14), fNR1 (n = 20) and mutant (n = 23) mice by absolute platform occupancy [time (sec) the mice spent in the area which corresponded exactly to the area occupied by the platform during the training session] [Cre, F(3,52) = 15.8, P < 0.0001; fNR1, F(3,76) = 37.4, P < 0.0001; mutant, F(3,88) = 35.5, P < 0.0001; Newman-Keuls post hoc comparison (the target platform position compared to all the other platform positions); P < 0.01 for all genotypes]. (G) The same sets of mice as in (F) were subjected to partial-cue probe trials on day 14 (P4) and absolute platform occupancy assessed. Cre and fNR1 mice exhibited similar recall under partial-cue conditions as under full-cue conditions (paired t test, P > 0.9 for each genotype), while recall by the mutant mice was impaired (paired t test, *P < 0.01). (H) Spatial histograms of the animals’ location during the full-cue (P3) and partial-cue (P4) probe trials. fNR1, n = 20; mutant, n = 23. (I) Relative recall index [RRI, averaged ratio of the target platform occupancy of the partial-cue (P4) or no-cue (P5) probe trial to that of the full-cue (P3) probe trial for each animal (17)] of fNR1 mice (n = 18, blue) and mutant mice (n = 22, red). The RRI value difference between the fNR1 and the mutant mice under the partial-cue conditions was significant (*P < 0.009; Mann-Whitney U test), while that under no-cue conditions was not (P = 0.9; Mann-Whitney U test). T, target quadrant; AR, adjacent right quadrant; OP, opposite quadrant; AL, adjacent left quadrant.

Partial cue removal

In order to assess the role of CA3 NRs in pattern completion at the behavioral level, we examined the dependence of spatial memory recall on the integrity of distal cues in the CA3-NR1 KO mice and their control littermates (17). We first subjected randomly selected subsets of the mice that had gone through the training and probe trial sessions to one more block (4 trials) of training 1 hour after the day 13 probe trial (P3) in order to counteract any extinction that may have occurred during the probe trial. On day 14, we subjected these animals to a fourth probe trial (P4) in the same water maze except that three out of the four extramaze cues had been removed from the surrounding wall. In the partial-cue probe trial, both the fNR1 control and Cre control mice searched the phantom platform location as much as they did in the full-cue probe trial. In contrast, the search preference of the mutant mice for the phantom platform location was significantly reduced by the partial cue removal (Fig. 5, F and G).

We also monitored the effect of the partial cue removal by the criterion of relative radial-quadrant occupancy. The target radial-quadrant occupancy of the Cre, fNR1, and mutant mice were 63.0 ± 4%, 65.9 ± 4%, and 66.4 ± 4% under the full cue conditions (P3), respectively, and 55.8 ± 5%, 58.8 ± 5%, and 44.6 ± 5% under the partial-cue conditions (P4), respectively. The effect of the partial cue removal was significant for mutant ( paired t test, P < 0.002) but not for Cre (P > 0.2) or fNR1 mice (P > 0.2).

The differential effect of partial cue removal on search behaviors of fNR1 control and mutant mice was also indicated by a difference in the distribution of the animal’s occupancy of locations during the probe trials (Fig. 5H): In the full-cue environment (P3), both mutant and fNR1 control mice focused their search at or near the location of the phantom platform, as did the fNR1 mice searching for the platform in the partial-cue environment. By contrast, the mutant mice spent the majority of the time at or near the release site at the center of the pool and significantly less time at or near the location of the phantom platform in the partial-cue environment (P4).

For each individual mouse, we also determined the occupancy time at the phantom platform location in the partial-cue probe trial and compared that with the phantom platform occupancy time in the earlier full-cue probe trial, yielding a “relative recall index (RRI)” measure (17). There was no effect of partial cue removal on this parameter in the fNR1 control mice, whereas the effect was highly significant for the mutant mice (Fig. 5I).

It is possible that the mutant mice performed poorly in the partial-cue probe trial because they had lost the spatial memory faster than the control mice. To test this possibility, we restored the full-cue training environment by returning the three missing cues and the platform, then subjected the same set of animals that had gone through the training and probe trials to one more block (four trials) of training on day 14, 1 hour after the P4 partial-cue probe trial. Both the mutant and fNR1 control animals found the platform as fast as they did on day 12 and day 13, and there was no significant difference between the latencies of the mutant and control animals (P = 0.32) (Fig. 5A). There were also no significant differences between mutant and control mice in the total path length traveled and in their thigmotaxic tendency to remain close the walls of the maze (P > 0.4 for both measures) (Fig. 5, B and D). These results indicated that the reason why the mutant mice performed poorly in the partial-cue probe trial was not faster memory loss. The results also confirmed that both the mutant and control animals had reached the asymptotic level of learning by day 12.

To test whether the recall in the partial-cue environment depended on the remaining spatial cue, we carried out a fifth no-cue probe trial (P5) on day 15 after removal of all of the extramaze cues. We found robust recall deficits in fNR1 control and mutant mice under these conditions (Fig. 5I). Both types of mice must have retained the memory of the platform location during this no-cue probe trial, because they reached the platform efficiently in a final block of training in the full-cue environment 1 hour after P5 (Fig. 5, A to D, at day 15) (P > 0.15 for any of four measures).

We also tested whether the mutants’ deficit in the partial-cue probe trial was due to impairment in perceiving the platform-distal cue. When mutants and fNR1 littermates were trained and probed with only one platform-distal cue, the mutants acquired the spatial memory, as well as the controls [mutant, F(3,36) = 5.5, P < 0.005; fNR1, F(3,36) = 17.7, P < 0.005; Newman-Keuls post hoc comparison (the trained radial-quadrant compared to all the other quadrants); P < 0.05 for both genotypes]. These results indicate that mutants are not defective in perceiving the platform-distal cue.

In summary, under the full-cue conditions both mutant and control mice exhibited robust memory recall. When three out of the four major extramaze cues were removed, control mice still exhibited the same level of recall, whereas the mutants’ recall capability was severely impaired.

Spatial coding in CA1

To investigate the neural mechanisms that might underlie this deficit in memory recall, we examined the neurophysiological consequences of CA3-NR1 disruption by analyzing CA1 place cell activity with in vivo tetrode recording techniques (17). Although genetic deletion was confined to CA3 pyramidal cells, place cell recordings were made from CA1 for two reasons. First, CA1 is the final output region of the hippocampus proper and, as a consequence, CA1 activity is more likely to reflect behavioral performance than CA3 activity. Second, most previous relevant electrophysiological tetrode recording studies have been performed in CA1 (22, 23), so CA1 recordings are most suited for comparison with published findings of place cell activity in other genetically altered mice (24).

We recorded from 188 complex spiking ( pyramidal) cells and nine putative interneurons from five mutant mice (24 sessions) and from 155 pyramidal cells and 8 interneurons from three fNR1 control mice (19 sessions) while the mice were engaged in open-field foraging (25). Although an analysis of the basic cellular properties of CA1 pyramidal cells revealed no difference in mean firing rate, spike width, or spike amplitude attenuation within bursts (26), pyramidal cells from mutant animals showed a significant decrease in complex spike bursting properties (complex spike index and burst spike frequency) (Table 1). This reduction may reflect a decrease in excitatory input from CA3 (27, 28) where NR1 is ablated. If so, the reduced CA3 input would also alter the coding properties of CA1 place cells in mutant animals. However, under full-cue conditions, we found no significant differences between fNR1 control and mutant animals in either place field size (number of pixels above a 1 Hz threshold) or average firing rate within a cell’s place field (integrated firing) (Table 1). Furthermore, the ability of cells with overlapping place fields to fire in a coordinated manner did not differ between fNR1 and mutant mice (covariance coefficient) (Table 1), in contrast with CA1-NR1 KO mice in which there was a complete lack of coordinated firing (24). Thus, spatial information within CA1 is relatively preserved despite the loss of CA3 NRs, providing a physiological correlate of the intact spatial performance of CA3-NR1 KO mice in the Morris water maze under full-cue conditions.

Table 1.

Properties of CA1 pyramidal cells and interneurons in familiar open field. Values are means ± SEM. For pyramidal from fNR1 controls cells in 19 recording sessions with three animals, n (cells) = 155; for mutant pyramidal cells in 24 recording session with five animals, n = 188; for fNR1 interneurons in 19 recording sessions with three animals, n = 8; for mutant interneurons in 24 recording sessions with five animals, n = 9. NA, not applicable.

| Measurement | Pyramidal cells |

Interneurons |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fNR1 | Mutant | fNR1 | Mutant | |

| Mean firing rate (Hz) | 1.175 ± 0.097 | 1.179 ± 0.082 | 30.96 ± 5.27 | 12.62 ± 1.73* |

| Spike width (μs) | 328.5 ± 4.31 | 326.8 ± 3.70 | 186.6 ± 9.7 | 167.2 ± 4.8 |

| Spike attenuation (%) | 90.44 ± 0.56 | 90.45 ± 0.40 | NA | NA |

| Complex spike index | 24.26 ± 1.21 | 16.84 ± 0.83† | 1.66 ± 0.52 | 1.67 ± 0.39 |

| Burst spike frequency (%) | 52.93 ± 1.17 | 42.18 ± 1.28† | NA | NA |

| Integrated firing rate [Σ(Hz/pixel)] | 549.5 ± 48.2 | 544.7 ± 40.0 | NA | NA |

| Place field size (no. of pixels) | 125.6 ± 8.28 | 133.1 ± 7.27 | NA | NA |

| Covariance coefficient | 0.0359 ± 0.007 | 0.0410 ± 0.005 | NA | NA |

Significantly different from fNR1 control (t test, P < 0.003).

Significantly different from fNR1 control (t test, P < 10−4).

CA1 pyramidal cells also receive inhibitory input from local interneurons, and CA1 output reflects a balance between excitatory and inhibitory inputs (29). The CA3-NR1 KO mice showed a decrease in the firing rate of putative CA1 interneurons (Table 1), which could be due either to a decrease in direct feed-forward input from CA3 onto inhibitory interneurons (30, 31) as a consequence of the CA3-NR1 knockout, or to a decrease in local feedback drive from CA1 pyramidal cells onto interneurons (32). This reduction in inhibition in mutant mice may compensate for the reduction of excitatory drive from CA3, thereby allowing CA1 pyramidal cells to maintain robust spatial coding. This hypothesis is consistent with previous theoretical (5) and experimental (33) studies.

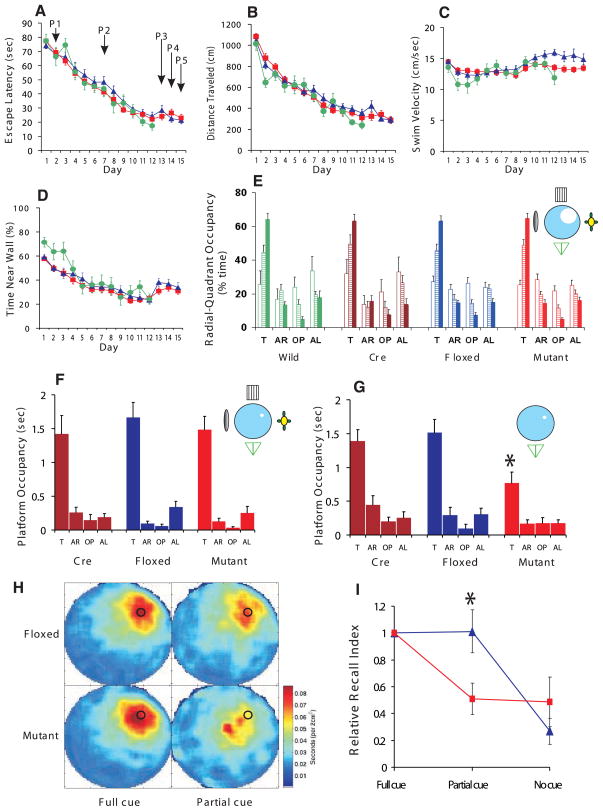

CA1 place cells

We next determined whether CA1 output would be maintained after partial cue removal (34, 35). Mice were allowed to explore an area for 20 to 30 minutes in the presence of four distal visual cues and then removed to their home cage. After a 2-hour delay, mice were returned to the open field with either the same four cues present (4 to 4 condition), or with three of the four cues removed (4 to 1 condition). Using three fNR1 control mice, we identified 28 and 26 complex spike cells during five “4 to 4” sessions and five “4 to 1” sessions, respectively. From five mutant mice we were able to isolate 43 and 47 complex spike cells during six “4 to 4” and six “4 to 1” recording sessions, respectively (Fig. 6, A and B)

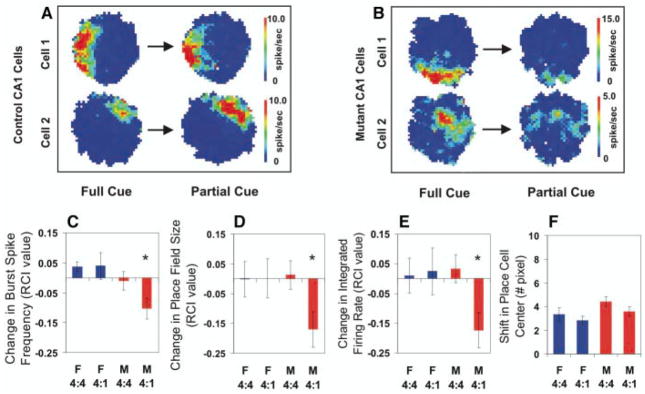

Fig. 6.

CA1 place cell activity in CA3-NR1 KO mice. (A and B) Examples of place fields that are representative of cells that showed no reduction [fNR1 (A)] and a reduction of field size [mutant (B)] before and after partial cue removal. (C to E) Relative change in the place field properties for each cell recorded across two conditions quantified with a relative change index (RCI, defined as the difference between the cell’s firing between two conditions divided by the sum of the cell’s firing across the two conditions) (17). Among the cells that were identified as the same cells throughout the two recording sessions, the average burst spike frequency [(C): F(3,140) = 4.16, P < 0.007; Fisher’s post hoc comparison (mutant 4:1 vs. all the other three paradigms), *P < 0.05], place field size over 1 Hz [(D): F(3,140) = 2.68, P < 0.049; Fisher’s post hoc comparison (mutant 4:1 versus all the other three paradigms), *P < 0.05], and the integrated firing rate [(E): F(3,140) = 3.20, P < 0.025; Fisher’s post hoc comparison (mutant 4:1 versus all the other three paradigms), *P < 0.05], were significantly reduced in the mutant animals (red bars) only after partial cue removal (4:1). In contrast, partial cue removal did not affect CA1 place cell activity in the control mice (blue bars). (F) Location of CA1 place field center between the two recording sessions was not shifted regardless of genotype and cue manipulation (F): F(3,140) = 2.15, P = 0.097. F, fNR1 control mice; M, mutant mice.

To quantify relative changes in place field properties of these cells, we calculated, for each cell, a relative change index (RCI) (17). Using this index, we measured three properties of CA1 output: burst spike frequency, place field size, and integrated firing rate (Fig. 6, C to E). Despite individual cell variation, on average in fNR1 mice there was no change in burst spike frequency, field size, or integrated firing rate of cells from the cue removal conditions relative to those from the no-cue removal conditions. Thus, at the population level, the net output from CA1 was maintained for fNR1 mice under cue removal conditions. In contrast, mutant cells showed significant reductions in burst spike frequency, place field size, and integrated firing rate after cue removal. It is important to note that mutant place cells showed no significant changes when mice were returned to the recording environment in the presence of all four distal cues. Average running velocity in the open field across all conditions was not different in both genotypes (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.70). When we examined whether the location of individual place fields shifted across conditions, we found no significant differences between mutant and fNR1 mice for either cue removal or no-cue removal conditions, suggesting that some reflection of past experience is maintained in the firing of mutant CA1 place cells even under conditions of partial cue removal (Fig. 6F).

These physiological results are compatible with the behavioral results, suggesting that reductions in CA1 output as a consequence of reduced CA3 drive resulting from cue removal may make it more difficult for mutants to retrieve spatial memories. This impairment may underlie the inability of mutants to solve spatial memory tasks, such as the water maze, when only partial distal cues are available.

Discussion

The formation of hippocampus-dependent memories of events and contexts involves incorporating complex configurations of stimuli into a memory trace that can be later recalled or recognized (1, 2). The subregions of the hippocampus likely serve complementary but computationally distinct roles in this process (3). For example, NRs in area CA1 are critical for the formation of spatial reference memory and normal CA1 place cells under conditions of fully cued memory retrieval (15, 24). In contrast, CA3-NR1 KO mice exhibit intact spatial reference memory under conditions of fully cued memory retrieval with normal behavior and normal CA1 place cell activity. Thus, area CA1 is a major site involved in the storage of spatial reference memory and that this memory can be formed without CA3 NRs.

Although previous studies of memory formation and recall under fully cued conditions (15) provided basic insights into the mechanisms of memory formation, in day-to-day life, memory recall almost always occurs from limited cues in real-life situations, as pattern completion (5). In the past, computational analyses have pointed out that a recurrent network with modifiable synaptic strength, such as that in hippocampal area CA3, could provide this pattern completion ability (5–10). The impairment exhibited by CA3-NR1 KO mice in recalling the spatial memory after partial cue removal provides a direct demonstration of a role for CA3 and CA3 NRs in pattern completion at the behavioral level. At the neuronal network level, pattern completion was indicated by intact CA1 place cell activity under cue removal conditions in control mice, demonstrating the ability of intact CA3-CA1 networks to carry out this function. By contrast, under the same partial-cue conditions, CA1 place field size in mutant mice without CA3 NRs was reduced, demonstrating incomplete memory pattern retrieval.

The residual search preference for the phantom platform location exhibited by mutant mice after partial cue removal (Fig. 5, G and H) reflects the degradation rather than the complete loss of spatial memory retrieval. This is consistent with the complementary observation of reduced place cell responses with preserved place field location (Fig. 6F), indicating a decrease rather than complete disruption of reactivation of the memory trace. This result may also reflect the existence of additional recall mechanisms independent of CA3 NR function.

Although plasticity at mossy fiber-CA3 synapses is NR-independent (11–14), plasticity at perforant path-CA3 synapses is NR-dependent (14). Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the feed-forward input to CA3 via the perforant path contributes to the observed pattern completion effects. However, the substantially greater strength of recurrent synaptic inputs relative to the contribution of the perforant path (36) suggests a dominant role for the recurrent system.

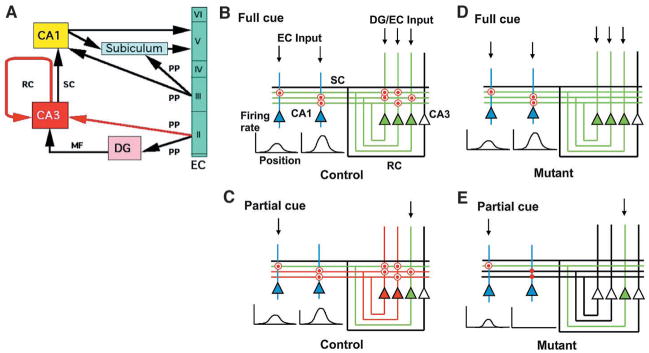

It has been proposed that memory can be stored in associative memory networks whose synapses are modifiable (5–10) (Fig. 7). In this model, inputs arriving via dentate mossy fibers or perforant path afferents (or both) would produce a pattern of CA3 ensemble output that reflects the pattern of inputs received. During normal memory acquisition under full-cue conditions, recurrent fiber synapses are modified in an NR-dependent manner to reinforce this ensemble pattern by strengthening connections between coactive neurons within the ensemble. This reflects storage of the memory trace within CA3 (Fig. 7, B and C). This complete CA3 pattern, driven by full-cue input and reinforced by recurrent connections, activates CA1 neurons and produces a pattern that serves as the output of the hippocampal circuit. The strengthening of connections between the CA3 and CA1 neurons that participated in this process reflects storage of the memory trace within CA1 (Fig. 7, B and C). Under full-cue conditions in mutant animals, the lack of NRs in the CA3 pyramidal cells prevents storage of the memory trace in the CA3 recurrent network but does not impair storage in CA1 (Fig. 7, D and E). The input for the memory storage in CA1 could also arrive via perforant path afferents directly from the entorhinal cortex.

Fig. 7.

Model for a distinct role of areas CA3 and CA1 in memory storage and recall. (A) General organization of the hippocampus. Red arrows, pathways that form NR-dependent modifiable synapses in CA3; EC, entorhinal cortex; DG, dentate gyrus; RC, recurrent collaterals; SC, Schäffer collaterals; MF, mossy fibers; PP, perforant path. (B to E) Basic wiring of CA3 and CA1, illustrating the proposed mechanisms for pattern completion. In control (B) and mutant (D), full cue input (downward arrows) is provided to CA3 from DG or EC and to CA1 from EC. Although the nature of these inputs is likely to be different, we do not consider this difference in this model. In control (C) and mutant (E), a fraction of the original input is provided to activate the memory trace during recall. For detailed explanation, see Discussion. Red dots, CA3 RC synapses or SC-CA1 synapses participating in memory trace formation; red circles, memory traces that are activated during recall; red dots without red circles, memory trace not activated during recall; red triangles and lines, CA3 pyramidal cell activity resulting from pattern completion through recurrent collateral firing; green triangles and lines, CA3 pyramidal cell response to external cue information; open triangles and black lines, silent CA3 pyramidal cells and inactive outputs; blue triangles, CA1 pyramidal cells.

Under conditions of normal recall, presentation of the full set of cues activates CA3 neurons in a pattern corresponding to the original CA3 memory trace, thereby leading to reactivation of the memory trace in CA1 (Fig. 7B). In mutant animals without CA3 NRs under full-cue conditions, although the CA3 memory trace is absent, the CA1 memory trace is reactivated directly by the incoming cues that correspond in their configuration to the pattern of the memory trace (Fig. 7D). Reactivation of previously strengthened recurrent synapses is unnecessary for recall under full-cue conditions, as indicated in the model (Fig. 7, B and D) and confirmed by our results from recordings in CA1. Nevertheless, the reactivation may contribute to the recall process in control animals by producing a more robust input to CA1 from CA3. This possibility would be consistent with the observed reduction in CA1 inhibitory cell activity in mutant animals, suggesting that even under full-cue conditions, the strength of input from CA3 might be diminished and compensated for through homeostatic reduction of feedback or feedforward inhibitory drive. In this way, a complete but weakened CA3 output pattern can provide sufficient drive to CA1 (33). Direct measurement of CA3 output may clarify some of these issues.

Under conditions of partial cue removal, limited input activity provides only partial activation of the CA3 output pattern in both control and mutant animals (green lines, Fig. 7, C to E). In control animals, this limited output activates previously strengthened recurrent synapses onto CA3 neurons that had participated in the original full-cue pattern (Fig. 7C). These recurrently driven cells complete the output pattern of CA3 (red lines, Fig. 7C), which can then drive the full output pattern in CA1. In mutant animals, limited input drives a correspondingly limited CA3 output pattern (green line in Fig. 7E). However, because of the lack of a memory trace in recurrent synapses, their activation is unable to drive neurons that had participated in the original full-cue pattern. This circumstance leads to a limited output pattern from CA3 that leads to a limited output pattern in CA1 in the form of smaller place fields with reduced firing rates (Fig. 7E).

Because CA3 NR function is absent during both memory formation and retrieval in CA3-NR1 KO mice, retrieval itself may be affected by NR manipulation. Infusion of AP5 selectively into the hippocampus impairs spatial memory acquisition but shows no effect on retrieval of previously trained spatial reference memory in the water maze (37), suggesting that our results reflect a primary deficit in NR-dependent memory formation in CA3 that is then revealed as a deficit in recall under limited cue conditions.

A substantial proportion of aged individuals exhibit deficits of memory recall (38). In early Alzheimer patients, retrieval is the first type of memory function to decline; such retrieval deficits may serve as an early predictor of Alzheimer disease (39, 40). Normal aging produces a CA3-selective pattern of neurochemical alterations (41–43). Exposure to chronic stress, which can lead to memory deficits, also selectively causes atrophy in the apical dendrites of CA3 pyramidal cells (44). These results are consistent with our findings in mice that the CA3 region is critical for cognitive functions related to memory recall through pattern completion.

This study along with our previous study with CA1-NR1 KO mice (15, 24) illustrates the power of cell type-restricted, adult-onset gene manipulations in the study of molecular, cellular, and neuronal circuitry mechanisms underlying cognition. The same neurotransmitter receptors (i.e., NMDA receptors) can play distinct roles in the mnemonic process depending on where and in which neural circuitry in the hippocampus they are expressed. It is expected that other genetically engineered mice with precise spatial and/or temporal specificity will help dissect mechanisms for a variety of cognitive functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Soriano, F. Tronche, T. Furukawa, R. J. DiLeone, F. Bushard, S. Chattarji, and M. Fukaya for reagents, assistance, and/or advice. We also thank the many members of the Tonegawa and Wilson Labs for valuable advice and discussions. Supported by an NIH grant RO1-NS32925 (S.T.), RIKEN (S.T. and M.W.), NIH grant P50-MH58880 (S.T. and M.W.), HHMI (S.T.), and Human Frontier Science Program (K.N.).

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1071795/DC1

Materials and Methods

References and Notes

- 1.O’Keefe J, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Squire LR. Psychol Rev. 1992;99:195. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaral DG, Witter MP. Neuroscience. 1989;31:571. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishizuka N, Weber J, Amaral DG. J Comp Neurol. 1990;295:580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marr D. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1971;262:23. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner-Medwin AR. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1976;194:375. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1976.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopfield JJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNaughton BL, Morris RGM. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:408. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rolls ET. In: The Computing Neuron. Durbin R, Miall C, Mitchison G, editors. Addison-Wesley; Wokingham, UK: 1989. pp. 125–159. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasselmo ME, Schnell E, Barkai E. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris EW, Cotman CW. Neurosci Lett. 1986;70:132. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams S, Johnston D. Science. 1988;242:84. doi: 10.1126/science.2845578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Science. 1990;248:1619. doi: 10.1126/science.2114039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger TW, Yeckel MF. In: Long-Term Potentiation: A Debate of Current Issues. Baudry M, Davis JL, editors. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1991. pp. 327–356. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsien JZ, Huerta PT, Tonegawa S. Cell. 1996;87:1327. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisden W, Seeburg PH. J Neurosci. 1993;14:3582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03582.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Relevant data and experimental procedures can be found at Science Online.

- 18.Liu Y, Fujise N, Kosaka T. Exp Brain Res. 1996;108:389. doi: 10.1007/BF00227262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe M, et al. unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chattarji S, Rao BSS, Nakazawa K, Tonegawa S. unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris RGM, Garrud P, Rawlins JNP, O’Keefe J. Nature. 1982;297:681. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller R. Neuron. 1996;17:813. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Best PJ, White AM, Minai A. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:459. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McHugh TJ, Blum KI, Tsien TZ, Tonegawa S, Wilson MA. Cell. 1996;87:1339. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller RU, Kubie JL. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quirk MC, Blum KI, Wilson MA. J Neurosci. 2001;21:240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00240.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartzkroin PA, Prince DA. Brain Res. 1978;147:117. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong RKS, Traub RD. J Neurophysiol. 1983;49:442. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.2.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paulsen O, Moser EI. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:273. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buzsaki G. Prog Neurobiol. 1984;22:131. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(84)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizumori SJY, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Brain Res. 1989;50:99. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Czurko A, Buzsaki G. Neuron. 1998;21:179. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizumori SJY, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Fox FB. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03915.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Keefe J, Conway DH. Exp Brain Res. 1978;31:573. doi: 10.1007/BF00239813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hetherington PA, Shapiro ML. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:20. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urban NN, Henze DA, Barrionuevo G. Hippocampus. 2001;11:408. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris RGM. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-09-03040.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher M, Rapp PR. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuokko H, Vernon-Wilkinson R, Weir J, Beattie BL. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13:871. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Backman L, et al. Neurology. 1999;52:1861. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Jeune H, Cecyre D, Rowe W, Meaney MJ, Quirion R. Neuroscience. 1996;74:349. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kadar T, Dachir S, Shukitt-Hale B, Levy A. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:987. doi: 10.1007/s007020050107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams MM, et al. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432:230. doi: 10.1002/cne.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McEwen BS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.