Abstract

Perinatal stroke in neonates can lead to disability in later life. However, its etiology and prognosis are poorly understood. The aim of this study was to describe clinical presentations and neurodevelopmental outcomes of our case series of perinatal stroke in Korea. Thirteen term and preterm neonates who were diagnosed with perinatal stroke in two university hospitals from March 2003 to March 2007 were enrolled. Seven term and 6 preterm neonates were diagnosed with perinatal stroke, based on the brain MRI findings. Perinatal stroke presented with seizure (4/13), perinatal distress (3/13) in term neonates, whereas stroke in preterm neonates did not present with noticeable clinical symptoms. Only one neonate had positive thrombophilic test (homozygous C677T polymorphism for MTHFR). Ten neonates had infarctions in the territory of the middle cerebral artery (MCA), and 3 neonates had borderzone infarctions between the anterior cerebral artery and MCA. Neurodevelopmental outcome was abnormal in 4 neonates. Infarction in MCA main branch or posterior limb of internal capsule showed an abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome. Our study is the first systematic study of perinatal stroke in Korea, and shows its clinical presentations and neurodevelopmental outcomes. The population-based study on incidence and prognosis of perinatal stroke in Korea is required in the future.

Keywords: Perinatal Stroke, Newborn, Magnetic Resonance Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Perinatal stroke is an increasingly recognized clinical entity that leads to hemiplegic cerebral palsy in later life (1). Although modern neonatal neuroimaging has improved the detection of infarctions, the etiology and prognosis of perinatal stroke have not been well described. The incidence of perinatal stroke varies according to the availability of neuroimaging and the diagnostic criteria used, but is believed to be about one per 4,000 live births (2). Furthermore, its lack of specific clinical features makes the diagnosis of perinatal stroke difficult resulting in its under-diagnosis (3, 4). Few studies (5-7) have investigated clinical presentations and neurodevelopmental outcomes of perinatal stroke based on combined findings of neuroimaging, electroencephalography (EEG) in neonates. To the best of our knowledge, reports on perinatal stroke in Korea have been relatively few, compared to those of western countries. Furthermore, there has been no report about perinatal stroke of preterm infant in Korea. The major aim of this study was to describe the clinical presentations and neurodevelopmental outcomes of perinatal stroke in term and preterm neonates in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case series

To search for the neonates diagnosed with perinatal stroke during admission to newborn nursery or neonatal intensive care unit in Seoul National University Children's Hospital or Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (level III teaching hospital), an electronic search of all head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reports generated from March 1, 2003 to March 1, 2008 was conducted. All neuroimaging reports containing any of the following text strings were retrieved: stroke, infarct, middle cerebral artery (MCA), posterior cerebral artery and anterior cerebral artery. Neuroimaging studies that revealed any of the followings were excluded; 1) an acute infarction occurring after 28 days of life; 2) intraventricular hemorrhage with unilateral parenchymal hemorrhage (venous infarction); 3) cystic periventricular leukomalacia; and 4) bacterial meningitis. The institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital approved the study (B-0911/087-104), and informed consent was waivered.

Maternal and perinatal characteristics

Maternal and perinatal information was obtained from electronic medical records. Complications during pregnancy or delivery were searched and included placental abruption, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, chorioamnionitis, oligohydramnios, prolonged second stage of labor, maternal prothrombotic disorder, and fetomaternal transfusion. Chorioamnionitis was diagnosed by placental histopathology, but this information was available only in 6 neonates. Perinatal factors included meconium-stained amniotic fluid, abnormal fetal heart rate pattern, umbilical arterial blood pH, type of delivery, and Apgar scores. Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns included late deceleration and decreased variability. Perinatal distress was defined as umbilical arterial blood pH lower than 7.0 or significant respiratory depression requiring tracheal intubation at the delivery room.

Thrombophilic factors

Thrombophilic screening test included prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, platelet count, fibrinogen, protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, anticardiolipin antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant. In addition, the presence of heterozygous factor V Leiden, G20210A mutation of the prothrombin gene, and homozygous C677T polymorphism for MTHFR was screened by PCR-based mutation analysis.

Brain MRI

Brain MRI was performed as a part of routine evaluation process for seizure, unexplained perinatal distress or prematurity. The infants were imaged on a 1.5 Tesla unit system (Intra Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands) using T1 weighted spin echo (SE 600/20 msec), inversion recovery (3800/30/950), and T2 weighted spin echo (SE 3500/208 msec) sequences, at a slice thickness of 3-4 mm. The field of view was 150-200 mm, and matrices were 256×256 or 512×512. Single-shot, multi-slice spin echo and echo planar imaging sequence were obtained with the following parameters comprise TR=800 msec, TE=123 msec, and diffusion sensitivity (b=1,100 sec/mm2). The diffusion gradient was applied to the cephalocaudal axis direction. The magnetic resonance angiography images were performed in 8 neonates using a 3-dimensional time-of-flight technique, and data was processed with a maximum intensity projection method. Arterial distribution, involvement of the basal ganglia, thalamus, and internal capsule, and the presence of coexisting hemorrhage were determined from radiologic reports. In term neonates, brain MRI scans were completed between days 2 and 4 of life except for one neonate in whom MRI scan was performed on day 16 after weaning from ventilator. Infarction in preterm infants was first detected by sequential brain ultrasonography and later confirmed by brain MRI. Based on the location, extent, and shape of the lesions, infarctions were categorized as either being in the territory of main cerebral arterial branch or having a borderzone distribution. Infarctions in the territory of the MCA were subdivided further according to a modified version of the criteria suggested by de Vries et al. into main cerebral branches, cortical branches, and lenticulostriate branches (8).

Electroencephalography

Twelve neonates underwent full standard EEG (16 channels) at a recording speed of 15 mm/sec. States of the neonates and all movements during examinations were recorded by a single technician. Background rhythm and the presence of epileptic discharges were evaluated.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes

Assessment of neurologic outcome was based on the neurologic examination findings performed at the last follow-up visits (14 months to 6 yr of age). A diagnosis of developmental delay was based on the results of Bayley Scales of Infant Development-2 (BSID-2) performed at 12 months corrected of age. In patients born prematurely, the correction for prematurity was made. BSID-2 was performed by a single pediatric rehabilitationist.

RESULTS

Clinical presentations of our case series

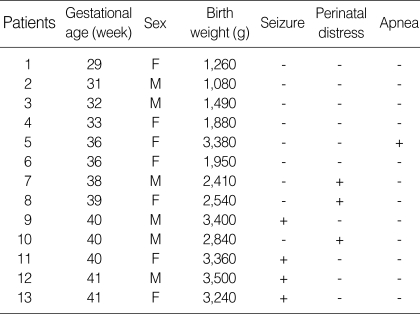

A total of 13 neonates, diagnosed with perinatal stroke during admission, were discovered. Of these neonates, 7 were term and 6 were preterm neonates, and 6 (46%) were male. Gestational age of preterm neonates ranged from 29 to 36 weeks, and birth weights ranged from 1,080 to 3,380 g (Table 1). Presenting symptoms or signs of perinatal stroke were seizure (4/13), significant perinatal distress (3/13), or apnea (1/13). Seizures occurred between 2 and 6 days after birth. Three neonates who presented with seizure were easily recognized clinically and promptly diagnosed, whereas those without seizure were unnoticed until stroke had been confirmed by brain MRI. In these neonates without seizure, brain MRI was performed as a part of routine evaluation process for unexplained perinatal distress in term neonates. In preterm neonates, serial cerebral ultrasonography, which was available in the neonatal intensive care unit at bedside, was performed as a routine evaluation of prematurity through the anterior fontanel. In 5 of the 6 preterm neonates, infarction was first detected by sequential brain ultrasonography and later confirmed by brain MRI. In one preterm neonate born at the 36th week of gestation, infarction presented with a sudden onset of apnea. The other preterm neonates with infarction were all asymptomatic. In all term and preterm neonates with perinatal stroke, routine laboratory tests including serum electrolytes, glucose, creatinine, liver function tests, lactate, white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein, and TORCH screening were normal. There was no laboratory evidence of polycythemia, thrombocytopenia or coagulation defects. No infants had structural cardiac abnormalities.

Table 1.

Clinical presentations of perinatal stroke

M, male; F, female.

Maternal and perinatal characteristics

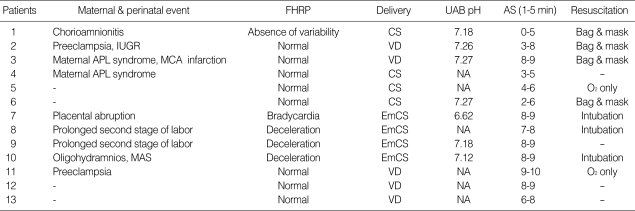

Maternal risk factors for perinatal stroke were present in 9 (69%) of the 13 neonates: 1 placental abruption; 2 preeclampsia; 1 chorioamnionitis; 1 oligohydramnios; 2 prolonged second stage of labor; 2 maternal prothrombotic disorder (antiphospholipid syndrome). There was no evidence of placental infarction in 6 neonates whose placenta were examined. Five neonates were born by spontaneous vaginal delivery and eight by cesarean section. Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were seen in 4 term and 1 preterm neonates. These 4 term neonates were delivered by emergency cesarean section. Three of them required tracheal intubation at the delivery room. One neonate intubated at the delivery room developed meconium aspiration syndrome complicated by persistent pulmonary hypertension. All six preterm neonates with perinatal stroke did not require intubation at the delivery room. Perinatal distress was present in 3 neonates, and they had significant respiratory depression requiring tracheal intubation at the delivery room. One neonate had an umbilical arterial blood pH lower than 7.0. Four neonates had low Apgar scores below 5 at 1 min, but none at 5 min. Details of individual maternal and perinatal findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Maternal and perinatal characteristics of patients with perinatal stroke

FHRP, fetal heart rate pattern; CS, cesarean section; UAB, umbilical arterial blood; AS, Apgar score; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; VD, spontaneous vaginal delivery; APL, antiphospholipid; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NA, not available; EmCS, emergency cesarean section; MAS, meconium aspiration syndrome.

Thrombophilic factors

Thrombophilic screening test was performed in 10 of the 13 neonates and 1 of these had abnormality. Antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S levels were within normal range. Heterozygous factor V Leiden and G20210A mutation of the prothrombin gene was not present. Homozygous C677T polymorphism for MTHFR was present in one neonate.

Brain MRI findings

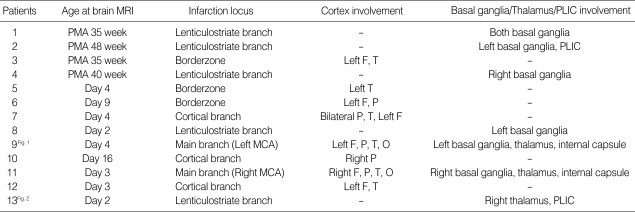

Eleven neonates (85%) had unilateral infarctions, which were more common on the left side than the right side (7:4). Ten neonates had infarctions in the territory of MCA, and 3 neonates had borderzone infarctions between the anterior and middle cerebral artery. In 10 neonates who had infarctions in the territory of MCA, 2 neonates had the involvement of main branches, 5 of lenticulostriate branches, and 3 of cortical branches. Of 5 neonates with lenticulostriate branch infarctions, 3 were preterm neonates. Two neonates with the involvement of lenticulostriate branches showed infarctions in posterior limb of internal capsule. Involvement of cortical branches was present in 3 full term neonates and borderzone infarction in 3 preterm neonates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings of patients with perinatal stroke

PLIC, posterior limb of internal capsule; PMA, postmenstrual age; F, frontal; T, temporal P, parietal; O, occipital; MCA, middle cerebral artery.

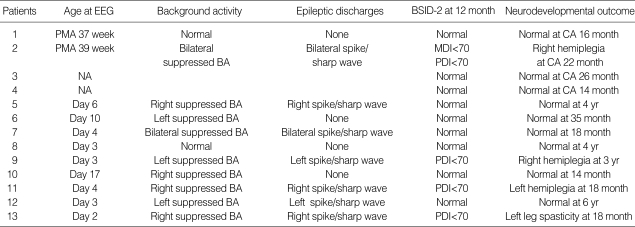

Electroencephalography

EEGs were recorded in 11 neonates. In 6 of the 7 term neonates, EEG was completed between days 2 and 4 of life. The other underwent EEG on day 16 after being weaned off from a high-frequency oscillatory ventilator. In the 6 preterm neonates, EEG was performed between 37 and 39 postmenstrual weeks after the infarction had been confirmed by brain MRI. Of these 11 neonates, 2 had a completely normal EEG, 7 had an abnormal background with epileptic discharges (3 on the right side, 2 on the left side and 2 bilateral). Two neonates had an abnormal background on the right or left side without epileptic discharges. Details of individual EEG findings are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Electroencephalography findings and neurodevelopmental outcomes of patients with perinatal stroke

BSID-2, Bayley Scales of Infant Development-2; PMA, postmenstrual age; CA, corrected age; BA, background activity; MDI, mental developmental index; PDI, psychomotor developmental index; NA, not available.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes

Neurodevelopmental outcomes were assessed at 14 months to 6 yr old. No infants experienced seizures after the neonatal period. Nine infants achieved a normal neurodevelopmental outcome. Four infants had an abnormal neurologic outcome. One infant had spasticity of left leg at the age of 18 months. Two infants had definite hemiplegia in the right side, and 1 infant in the left side. These 4 infants with abnormal neurologic outcome showed a developmental delay in BSID-2. Details of neurodevelopmental outcome are shown in Table 4.

Seizures were more common in infants with abnormal outcome. All 3 infants presenting with perinatal distress resulted in normal outcome. One infant with homozygous C677T polymorphism for MTHFR had abnormal outcome. All 3 preterm infants with borderzone infarction had normal outcome. The 4 full term neonates who had the involvement of main branches or posterior limb of internal capsule resulted in abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome. Abnormal background activity (either unilateral or bilateral) in the EEG was found in 9 neonates and 4 of these had a poor neurodevelopmental outcome.

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first systematic study that shows clinical presentations and neurodevelopmental outcomes of perinatal stroke in Korea. Perinatal stroke occurs rarely and are unnoticed clinically resulting in delay in its diagnosis (8-10). It is not easy to identify perinatal stroke unless neonates present with clinical seizure. Perinatal stroke was presented by seizure, apnea or respiratory distress requiring ventilatory support in term neonates, whereas preterm neonates were mostly asymptomatic in the present study. There is little literature available about perinatal stroke that is not associated with an intraventricular hemorrhage in the preterm infant. Benders et al. (11) found that lenticulostriate infarction appeared to be especially common in the preterm population, whereas cortical infarction were uncommon in their cohort. In the present study, no preterm neonate was involved with main branch or cortical branch infarction. All preterm neonates had lenticulostriate branch or borderzone infarction, and their neurodevelopmental outcomes were all favorable. The 4 full-term neonates who had the involvement of main branches or posterior limb of internal capsule resulted in abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome.

Brain MRI provides more details about distinct localization, extension of lesion and noninvasive evaluation of vascular integrity by magnetic resonance angiography. It is undoubtedly more sensitive method for predicting long term neurodevelopmental outcome than Apgar score or neonatal encephalopathy severity staging (2, 7, 11). Furthermore, MRI with diffusion weight image and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurements was very helpful for confirming tentative diagnosis in the first few days of life in our case series (Figs. 1, 2). Diffusion-weighted imaging can show early changes in the reduction of diffusivity at the cellular level that are undetectable by any other imaging modality in the hyperacute stage of infarction (13-16). Diffusion weight image has been found to increase the sensitivity of detecting neonatal strokes compared with conventional MRI.

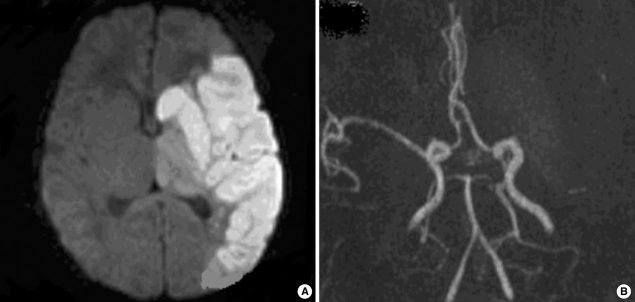

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI findings of patient 9. (A) Axial diffusion-weighted image showing hyperintensity in the territory of left middle cerebral artery. (B) MR angiography demonstrates loss of flow distal to the left middle cerebral artery bifurcation.

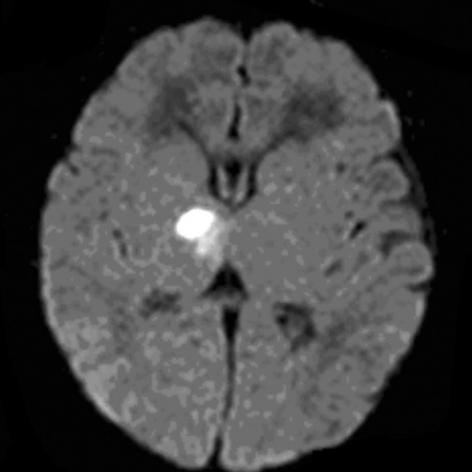

Fig. 2.

Brain MRI finding of patient 13. Axial diffusion-weighted image showing hyperintensity in right thalamus and posterior limb of internal capsule.

The concomitant involvement of the cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus and internal capsule by infarction in main cerebral branch has been associated with poor neurodevelopmental outcome (17). In the present study, 4 infants who had involvement of main branch or posterior limb of internal capsule, had hemiplegia or spasticity and concurrent EEG abnormalities. Mercuri et al. (18) found that an infarction involving the internal capsule predicts the development of hemiplegia, whereas predictions based on involvements of other regions are less reliable. They suggested that internal capsule plays an important role in the prognosis of motor outcome in patients with perinatal lesions. De Vries et al. (19) suggested asymmetrical myelination of the posterior limb of the internal capsule on brain MRI is an early predictor of hemiplegia. The absence of myelination in the posterior limb of the internal capsule, as a marker of Wallerian degeneration of corticospinal tracts, appears to be correlated with abnormal EEG findings and motor impairments in the extremities. Ten (77%) infants had infarctions in the distribution of the MCA, and left side was more common accounting for two thirds. These findings are consistent with those of a previous study which found that neonatal cerebral infarction occurs more commonly in the left cerebral hemisphere and in the distribution of the MCA (20). This predominance of left-sided lesions may be caused by vascular asymmetry due to patent ductus arteriosus (21).

Neonatal seizure is a common clinical finding that triggers recognition of perinatal stroke in term infants. In the present study, 2 of the 3 neonates who experienced seizure had an abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome. Other reports have also suggested that concurrent seizure during the neonatal period is associated with an unfavorable neurodevelopmental outcome in patients with perinatal stroke (22).

Inherited coagulation abnormalities may lead to adverse maternal and fetal events through thrombosis at the placenta (23-25). Thrombosis on the maternal side may lead to preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction, whereas on the fetal side it is a possible source of emboli that can bypass the hepatic and pulmonary circulations and reach the fetal brain. Recent evidence suggests that thrombophilias, including heterozygous factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, and homozygous C677T polymorphism for MTHFR may also play a causative role in perinatal stroke (26, 27). Phospholipids are required for the activations of protein C and the coagulation pathway. Anti-phospholipid antibodies, including lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibody, interfere with normal coagulation and may be a risk factor for perinatal stroke (28). There were no inherited coagulation abnormalities found in our patients except for a single case with homozygous C677T polymorphism for MTHFR.

EEG is a useful and sensitive tool for evaluating the degree of neurological damage in perinatal stroke (29). Mercuri et al. (17) suggested that early neonatal EEG was a prognostic indicator of motor outcome. In their study, the abnormal background was associated with abnormal motor outcome whereas other EEG abnormalities such as epileptic discharges in the presence of a normal background were not associated with abnormal outcome. In the present study, abnormal background activity (either unilateral or bilateral) was found in 9 neonates and 4 of these had a poor neurodevelopmental outcome. The EEG data was not very informative in the preterm neonates possibly as they were obtained rather late and electrical seizure activity is not absolutely considered as abnormal in preterm neonates.

Several limitations are noted in our current study, mainly due to its limited subject size and retrospective nature. Regardless of these limitations, however, it is believed that this case series may be able to add some valuable information to rare perinatal stroke that have not been well described in Korea. Finally this study may assist physicians predicting long-term prognosis and planning rehabilitative care for the neonates with perinatal stroke.

Footnotes

The content of this paper was presented during a poster session at the Recent Advances in Neonatal Medicine in Wurzburg, Germany, October 2-4, 2008.

References

- 1.Lee J, Croen LA, Backstrand KH, Yoshida CK, Henning LH, Lindan C, Ferriero DM, Fullerton HJ, Barkovich AJ, Wu YW. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with perinatal arterial stroke in the infant. JAMA. 2005;293:723–729. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boardman JP, Ganesan V, Rutherford MA, Saunders DE, Mercuri E, Cowan F. Magnetic resonance image correlates of hemiparesis after neonatal and childhood middle cerebral artery stroke. Pediatrics. 2005;115:321–326. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sreenan C, Bhargava R, Robertson CM. Cerebral infarction in the term newborn: clinical presentation and long-term outcome. J Pediatr. 2000;137:351–355. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu YW, March WM, Croen LA, Grether JK, Escobar GJ, Newman TB. Perinatal stroke in children with motor impairment: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:612–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci D, Mercuri E, Barnett A, Rathbone R, Cota F, Haataja L, Rutherford M, Dubowitz L, Cowan F. Cognitive outcome at early school age in term-born children with perinatally acquired middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Stroke. 2008;39:403–410. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLinden A, Baird AD, Westmacott R, Anderson PE, deVeber G. Early cognitive outcome after neonatal stroke. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1111–1116. doi: 10.1177/0883073807305784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Croen LA, Lindan C, Nash KB, Yoshida CK, Ferriero DM, Barkovich AJ, Wu YW. Predictors of outcome in perinatal arterial stroke: a population-based study. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:303–308. doi: 10.1002/ana.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vries LS, Groenendaal F, Eken P, van Haastert IC, Rademaker KJ, Meiners LC. Infarcts in the vascular distribution of the middle cerebral artery in preterm and fullterm infants. Neuropediatrics. 1997;28:88–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sran SK, Baumann RJ. Outcome of neonatal strokes. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:1086–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150100080031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estan J, Hope P. Unilateral neonatal cerebral infarction in full term infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997;76:F88–F93. doi: 10.1136/fn.76.2.f88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benders MJ, Groenendaal F, Uiterwaal CS, Nikkels PG, Bruinse HW, Nievelstein RA. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with perinatal arterial stroke in the preterm infant. Stroke. 2007;38:1759–1765. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.479311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vries LS, Van der Grond J, Van Haastert IC, Groenendaal F. Prediction of outcome in new-born infants with arterial ischaemic stroke using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropediatrics. 2005;36:12–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowan F, Pennock J, Hanrahan J, Manji KP, Edwards AD. Early detection of cerebral infarction and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in neonates using diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropediatrics. 1994;25:172–175. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huppi PS, Inder TE. Magnetic resonance techniques in the evaluation of the perinatal brain: recent advances and future directions. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:195–210. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillard JH, Papadakis NG, Martin K, Price CJ, Warburton EA, Antoun NM, Huang CL, Carpenter TA, Pickard JD. MR diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract disruption in stroke at 3 T. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:642–647. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.883.740642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirton A, Shroff M, Visvanathan T, deVeber G. Quantified corticospinal tract diffusion restriction predicts neonatal stroke outcome. Stroke. 2007;38:974–980. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258101.67119.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercuri E, Rutherford M, Cowan F, Pennock J, Counsell S, Papadimitriou M, Azzopardi D, Bydder G, Dubowitz L. Early prognostic indicators of outcome in infants with neonatal cerebral infarction: a clinical, electroencephalogram, and magnetic resonance imaging study. Pediatrics. 1999;103:39–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercuri E, Barnett A, Rutherford M, Guzzetta A, Haataja L, Cioni G, Cowan F, Dubowitz L. Neonatal cerebral infarction and neuromotor outcome at school age. Pediatrics. 2004;113:95–100. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Vries LS, Groenendaal F, van Haastert IC, Eken P, Rademaker KJ, Meiners LC. Asymmetrical myelination of the posterior limb of the internal capsule in infants with periventricular hemorrhagic infarction: an early predictor of hemiplegia. Neuropediatrics. 1999;30:314–319. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlman JM, Rollins NK, Evans D. Neonatal stroke: clinical characteristics and cerebral blood flow velocity measurements. Pediatr Neurol. 1994;11:281–284. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beattie LM, Butler SJ, Goudie DE. Pathways of neonatal stroke and subclavian steal syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F204–F207. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.079830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golomb MR, Garg BP, Carvalho KS, Johnson CS, Williams LS. Perinatal stroke and the risk of developing childhood epilepsy. J Pediatr. 2007;151:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrilho I, Costa E, Barreirinho MS, Santos M, Barbot C, Barbot J. Prothrombotic study in full term neonates with arterial stroke. Haematologica. 2001;86:E16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercuri E, Cowan F, Gupte G, Manning R, Laffan M, Rutherford M, Edwards AD, Dubowitz L, Roberts I. Prothrombotic disorders and abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with neonatal cerebral infarction. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1400–1404. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grabowski EF, Buonanno FS, Krishnamoorthy K. Prothrombotic risk factors in the evaluation and management of perinatal stroke. Semin Perinatol. 2007;31:243–249. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdu A, Cazorla MR, Moreno JC, Casado LF. Prenatal stroke in a neonate heterozygous for factor V Leiden mutation. Brain Dev. 2005;27:451–454. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson KB. Thrombophilias, perinatal stroke, and cerebral palsy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:875–884. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000211956.61121.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bobrowska-Snarska D, Ostanek L, Nesterowicz B, Brzosko M. Severe neurological and obstetrical complications in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2006;115:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selton D, Andre M, Hascoet JM. Interest of EEG in full-term newborns with isolated unilateral ischemic stroke. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12:630–634. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]