Abstract

Introduction

Health care financing provides the resources and economic incentives for operating health systems and is a key determinant of health system performance. Equitable financing is based on: financial protection, progressive financing and cross-subsidies. This paper describes Uganda's health care financing landscape and documents the key equity issues associated with the current financing mechanisms.

Methods

We extensively reviewed government documents and relevant literature and conducted key informant interviews, with the aim of assessing whether Uganda's health care financing mechanisms exhibited the key principles of fair financing.

Results

Uganda's health sector remains significantly under-funded, mainly relying on private sources of financing, especially out-of-pocket spending. At 9.6 % of total government expenditure, public spending on health is far below the Abuja target of 15% that GoU committed to. Prepayments form a small proportion of funding for Uganda's health sector. There is limited cross-subsidisation and high fragmentation within and between health financing mechanisms, mainly due to high reliance on out-of-pocket payments and limited prepayment mechanisms. Without compulsory health insurance and low coverage of private health insurance, Uganda has limited pooling of resources, and hence minimal cross-subsidisation. Although tax revenue is equitable, the remaining financing mechanisms for Uganda are inequitable due to their regressive nature, their lack of financial protection and limited cross-subsidisation.

Conclusion

Overall, Uganda's current health financing is inequitable and fragmented. The government should take explicit action to promote equitable health care financing by establishing pre-payment schemes, enhancing cross-subsidisation mechanisms and through appropriate integration of financing mechanisms.

Introduction

A resolution of the 58th World Health Assembly urges Member States to ensure that health financing includes a method for prepayment of financial contributions, so as to enhance risk-sharing and reduce catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment of care-seeking individuals1. Equitable financing is based on: financial protection (no one in need of health services should be denied access due to inability to pay and households' livelihoods should not be threatened by the costs of health care); progressive financing (contributions should be made according to ability-to-pay, and those with greater ability-to-pay should contribute a higher proportion of their income than those with lower incomes); and cross-subsidies (from the healthy to the ill and from the wealthy to the poor). Therefore, an equitable financing mechanism is one that enhances cross-subsidisation, allows for a greater proportion of the population to be covered, and has progressive contributions.

Health care financing for many African countries comes from tax revenues, donor funds and out-of-pocket expenditure, with very little pooling and risk-sharing mechanisms2. Out-of-pocket (OOP) spending is an inequitable financing mechanism (because contributions are not made on the basis of ability to pay) and funding from general taxes may or may not be inequitable, depending on progressivity of tax contributions2. While the scope for raising additional resources through alternative mechanisms is constrained, countries could benefit from re-arranging and integrating existing financing mechanisms with the view to making them more equitable and efficient.

In this paper, we provide an assessment of Uganda's health care financing from an equity perspective. Specifically, we provide a description of Uganda's health care financing landscape; discuss the key equity-related issues; and provide relevant recommendations.

Methods

We collected data largely through in-depth review of relevant literature and use of authors' knowledge about health sector financing from previous studies3,4. The review of relevant documents - from local and international sources - was conducted between July and September 2008, by a team of one health economist and one economist. We obtained information largely from key Ministry of Health (MOH) documents such as the National Health Sector Strategic Plan II5; Annual Health Sector Performance Reports - AHSPR (2002/3 – 2007/8)6,7,8,9,10,11; the Health Financing Strategy12; and the Public Expenditure Review report4. In addition, we reviewed international literature including World Health Organisation reports on health financing and fair financing work published by EQUINET. Given that the only available information on private financing for the health sector was for 1998/99–2000/01 based on the National Health Accounts data13, this paper mainly discusses issues related to public spending on health. Benefit incidence, the most commonly used methodology for equity in health financing, is not used in this study due to limitations in data.

The process for this review involved collection of physical copies of relevant documents from MOH and downloading reports from EQUINET and WHO websites. The team worked together to critically analyse each financing mechanism from an equity perspective. We took into consideration quality control measures to identify omissions and errors in the literature review. Such measures included debriefing meetings and review of write-ups by the principal investigator. The equity analysis framework used is based on fair financing work done for Global Forum for Health Research14.

The major limitation for this assessment was lack of recent data on private spending. In relation to accuracy, although figures we report on donor project funding have been noted to have significant differences from figures usually obtained through donor surveys4, 10, 11, this does not have direct bearing on the equity assessment.

Results

Overview of health care financing landscape

1. Source of funding and amounts (trends)

Contribution mechanisms

Health care resources in Uganda come from both public and private sources. Private sources include households, private firms and not-for-profit organisations; the two major sources of public funds are (a) government and (b) donors (through health projects and direct district support and Global Health Initiatives (GHIs).

The Government of Uganda's (GoU) contribution includes central government funds (from taxes), local government funds and the funds from donors/development partners channelled through general budget support. Donor funding is channelled through general budget support and through project support (e.g. to districts and non- government organisations). Although donor funding through general budget support is considered to be a flexible funding source that allows increased government control over the resource allocation process, there are concerns that more recent Medium Term Expenditure Frameworks (MTEFs) showed a slower rate of growth in the MOH budget, with the share for the health sector progressively declining in recent years, e.g. from 11.2% in 2004/5, to 9.6% in 2006/7 and 2007/8 and is projected to decline further to 8.3% in 2008/910. According to Uganda's first NHA, GoU contributed a less (about 39%) than donors (60%) to public spending on health in 2000/01. Put differently, GoU contributed 17.9% and donors contributed 27.4% of total spending on health13.

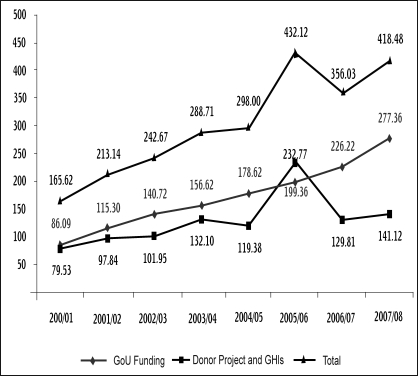

Despite the increases in public spending on health (Figure 1) over 8 years, sector funding remains significantly lower than the target of US$28 per capita estimated as the amount required to provide the Uganda National Minimum Health Care Package (UNMHCP)12. Current public funding ($8.2 per capita in 2007/8) is much lower than the US$34 target estimated by the Commission for Macroeconomics on Health.

Figure 1. Trends in real public spending (by source) & total public spending on health 2000/1 – 2007/8 (billion, Uganda shillings at 2007/8 prices).

Source: MOH (2006), MOH(2008); Annual Health Sector Performance reports

Although financing and expenditure reviews are conducted annually for public funds (government revenue and donor funding), there is limited documentation of private funding and expenditure. Apart from the NHA undertaken for the years 1998/99–2000/01, no recent estimates of private spending on health have been reported. The NHA reported higher spending from private sources than public sources. Further, results showed OOP expenditure from households was the largest source of funding, contributing 40% to 46% of total health expenditure13. A few community-based insurance initiatives (CBHI) cover about 2% of the catchment population, but most of them face severe sustainability problems and a few have been closed in the last few years15. Voluntary private prepayment schemes cover less than 1% of the population, and mainly exist in urban areas where companies provide medical cover for their employees3.

Who collects

Key revenue collecting institutions include Uganda Revenue Authority (URA), a few CBHI schemes, private insurance funds and private health care providers. All public resources are collected by the treasury in Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MOFPED). Domestic revenue obtained from taxes is collected by URA for individuals working in the formal sector and companies. URA imposes indirect taxes on goods and services and 18% Value-Added Tax. In addition to the resources from taxes, donors provide financial support to the general national budget. The amounts of funding channelled through general budget support are not documented in any official MOFPED documents, so special effort would be required to obtain such information. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this information is usually difficult to obtain even when special efforts are made. Donor funding channelled through projects or Global Health Initiatives (GHIs) is directly managed sometimes by donors or their preferred agencies, or by Ministry of Health, health facilities or NGOs.

Resources from private sources are mainly collected by a few private health insurance companies, a few CBHI schemes, and private health care providers (the biggest collectors of private resources).

Managers of health care resources

Public managers of health care resources include the MOH, other line ministries, districts health services and parastatals, while private managers include private health insurance agencies, households, facility-based NGOs and private firms. According the NHA report13, public institutions managed about 30% while about 70% was managed by private institutions/households. In the absence of more recent NHA data, it is difficult to tell whether this picture has changed in the last seven years. Within the public sector, MOH headquarters manages the biggest percentage, followed by district health officers and health facilities. Within the private sector, households and NGOs manage the biggest proportion. A small percentage (less than 0.2%) is managed by insurance agencies (and health maintenance organisations).

2. Risk pooling and allocation mechanisms

Coverage and composition of risk pools

The heavy reliance on out-of-pocket funding and the absence of integrated financing mechanisms result in very poor fund pooling in Uganda.

Public resources in Uganda can be considered to have a good degree of cross-subsidies. Income tax is reasonably progressive, but some components (e.g. tax on goods and services) are regressive. Services at all government health facilities are free to everyone since 2001. While the removal of user fees was an excellent reform as far as equity is concerned, the relatively poor quality of services in public health facilities has created a two-tier system in access to services. The poor are left to access the free (but poor quality) services while the relatively rich access services in the private health facilities (of relatively better quality) but have to pay for them.

Assessment of funding from donor projects is complex. Some funding is targeted at national-level activities (which benefit the whole population) and others target specific regions or districts in the country. Attempts at quantifying donor project funding for health on a regular and consistent basis has proved difficult, and as such it is hard to know the total size of funds involved. Donor project funds are usually spent on vertical programmes or on disease-specific activities, so it is difficult to articulate the proportions (or the segments) of the population benefiting from donor project funds. Regarding allocation mechanisms, donors' criteria for selecting some districts and not others is not explicitly documented anywhere.

Resource allocation mechanisms vary between donor projects, depending on the objectives and interests of the donor/project, and it is not clear whether equity is a key consideration in resource allocation. The lack of explicit guidelines for selection of project implementation sites (and hence geographic resource allocation) has the potential to stimulate geographic inequity in the spread of donor activities (and resources).

Private resources comprise dozens of very small risk-pools, through small and highly fragmented CBHI and voluntary private prepayment schemes. Private health prepayment schemes are still in their infancy and cover less than 1% of population in key urban areas (especially Kampala), usually provided by corporate employers for their employees and their dependants3. Such small and highly fragmented schemes do not enhance the principles of equity, especially cross-subsidisation. Uganda is still considering the introduction of national health insurance (NHI). Significant steps have been achieved in designing and debating the NHI scheme, but some effort is still required before NHI is accepted and successfully introduced. The proposed design of NHI has potential for improving risk-pooling and increasing coverage, and its implementation can be used as an avenue to reduce current fragmentation in the smaller risk pools of CBHIs and private health insurance schemes.

Allocation mechanisms

Public funds are transferred directly to the specified entities; including, the MOH headquarters, districts and regional referral and national referral hospitals. Allocation amounts for each entity is based on a formula that takes into consideration population size, special considerations (e.g. areas affected by war or historically disadvantaged), human development index, per capita donor and NGO spending in the district, and historic budgeting.

According to the Public Expenditure report there has been a focus on shifting resources to lower levels of care, especially district health services (which mainly cater for people living in the rural areas, i.e. those with relatively lower incomes), over the past seven years4. Funds allocated to district health services steadily increased from 32% to 54%, while the proportions allocated to higher level institutions and facilities (e.g. MOH headquarters and referral hospital) decreased consistently from 30% to 18%4. In the district health services, primary health care (PHC) facilities received the greatest percentage of resources, and absolute amounts received by these facilities increased consistently over the period4. Regarding funding levels for district hospitals, there is no consistent trend for this level of health care funding seemed to decrease one year and then increase in the next year4. The basis for allocation of donor project funds is not well documented in Uganda. Funds from private sources are purely allocated on the basis of where beneficiaries seek care.

3. Purchasing

Benefit package

Benefit packages vary widely across the different financing mechanisms. The MOH established a comprehensive Uganda National Minimum Health Care Package (UNMHCP), which includes a wide range of services to be provided at different levels of care. The package covers four broad areas including: health promotion, disease prevention, and community health initiatives; maternal and child health; prevention and control of communicable diseases; and, prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. This package can be accessed by the whole population, but due to inadequate funding of the health sector, the quality and scope of services provided at health facilities is actually lower than that described in the HSSP II11. For instance, the MOH noted that weak supply management systems lead to frequent stock-outs of key health commodities (e.g. medicines, testing kits, laboratory consumables, and condoms) and hinder the achievement of targets for some communicable diseases11.

The benefit package associated with donor project funds is neither well-defined nor clearly documented, because this funding is usually targeted towards specific health problems (e.g. a specific disease). As a result, the packages are highly fragmented and they overlap with packages funded through other financing mechanisms.

Private insurance/prepayment schemes specify a package for members depending on the level of contributions. Packages range from basic packages for which they charge the lowest insurance contribution to more sophisticated packages that include air evacuation and services provided outside the country. Private insurance is mainly provided by employers, covering mainly employees and their immediate families3.

Provider payment mechanisms

Health care providers in public facilities are given a budget within which to operate (key informant interviews, 2008). Budget allocations are not based on performance of health facilities, thus there are poor incentives for health workers and facility managers to improve service provision (key informant interviews, 2008). In the private sector, providers of care are reimbursed mainly on a fee- for-service basis. This reimbursement mechanism has the potential for problems associated with incentives to over-service (and supplier-induced demand) and hence rapidly spiralling health care costs.

Discussion

Key equity concerns for health care financing

In 2006, the Regional Committee for Africa developed a Health Financing Strategy for the African Region1. Two of the four objectives of this Strategy are: (a) to ensure equitable financial access to quality health services, and (b) to ensure that people are protected from financial catastrophe and impoverishment as a result of using health services. The Strategy also underscores the importance of expanding risk-sharing mechanisms and reducing OOP. This paper partly addresses a key recommendation of the Strategy, namely: that WHO Member States collect information on the implementation of the strategy continuously. This section of paper discusses the equity implications and concerns related to Uganda's health care financing mechanisms. In the absence of data, the benefit incidence approach could not be used.

Inadequate funding for the sector

Uganda's health sector is still largely under-funded, thereby making it difficult to attain sector targets. Uganda's Health care Financing Strategy12 estimated the per capita expenditure on health necessary to deliver the UNMHCP to be US$ 28. However, the sector only achieved US$ 8.2 in 2007/8. In addition, the share of government budget allocated to the health sector (e.g. 9.6 percent in 2007/8) still falls short of the Abuja target of 15 percent. We find it particularly worrying that from a baseline on 11.2 percent in 2004/5, the percentage of the government budget spent on health has fallen to 9.6 percent in 2007/8.

Although funding from development partners shows an upward trend in the last five years, funding from these sources fluctuates from year to year showing some degree of unpredictability and unsustainability. GoU funding is relatively more stable, but the year-to-year increases are minimal. The need to increase public funding is even more justified when we consider the rapidly growing population. Some countries in the region (e.g. Malawi) have made giant strides in meeting this funding target17.

GoU, through the MoH, regularly compiles information on the progress made towards achieving the Abuja target. The health sector would benefit from progressive and consistent increases in GoU funding, with a commitment to meet the Abuja target within three to five years.

Limited pre-payment schemes

With an average 0.13% contribution by private health insurance schemes and in the absence of a national health insurance scheme, financing for Uganda's health sector is largely not pre-paid. The only prepaid funds for Uganda's health sector are those from GoU and the limited voluntary and community-based health insurance schemes. Private health insurance schemes mainly cater for the middle-income working population (since they are mainly offered by the employer) and community-based health insurance schemes mainly enrol low income informal sector employees. This stratification shows a clear absence of income cross-subsidisation that is an essential characteristic of an equitable financing mechanism. Prepayments help ensure risk-sharing across populations and avoid catastrophic effects of health care expenditure and impoverishment as a result of seeking health care.

We recommend integration of all voluntary private prepayment schemes to promote larger risk pools and improve cross-subsidisation. Before this is achieved, government needs to improve the existing regulatory framework for private health insurance in Uganda, for example, by developing for guidelines on selection of members and definitions of benefit packages. Furthermore, private prepayment schemes should be integrated with the larger GoU funding pool. Specifically, Government should also put mechanisms in place to ensure that people covered by insurance schemes (for a specified benefit package) do not access the same benefit package funded through GoU, but could access other GoU-funded services (e.g. referral services) not covered by their insurance schemes.

Regressive financing and lack of financial protection

Although public health services are provided free of charge in Uganda, the poor quality of services, lack of appropriate medicines in health facilities10 and poor physical access to facilities continues to result in reliance on formal and informal private health care providers18. Moreover, the incidence of benefit for public funds is not regularly assessed or monitored, and this is a glaring gap for which we recommend further research and that a mechanism for routine analyses to be established. With limited voluntary health insurance in the country, OOP spending remains the most significant financing mechanism, accounting for half of all private funding for health13. OOP spending is one of the most regressive funding mechanisms, because contributions are mainly not made on the basis of ability to pay, and those without money can be excluded from accessing services or are likely to become impoverished as a result of seeking health care services. In addition, funds from OOP spending are not pooled and thus there is limited cross-subsidisation.

Implementing mandatory health insurance will help pool OOP resources. Social or national health insurance is a pre-payment mechanism which, if well designed and appropriately implemented, has the potential to improve health financing in Uganda by enhancing risk-pooling and promoting cross-subsidisation. Contributions can also be progressively structured to promote equity. Given the challenges of lack of protection associated with OOP spending and the lack of adequate pre-payment mechanisms, we recommend careful introduction of mandatory health insurance in Uganda. We argue that its introduction should be seized by government as an opportunity for comprehensive review and reform existing financing mechanisms. Specifically, the National Health Insurance Task Force should, in planning for the introduction of NHI: 1) use the opportunity to promote equity and integrate financing mechanisms, and 2) ensure that the scheme does not create further fragmentation and tiered access to health services.

Limited cross-subsidisation and fragmentation of financing mechanisms

Financing mechanisms with a high degree of fragmentation have limited cross-subsidisation and thus are relatively more regressive14. There is limited cross-subsidisation and high fragmentation among health financing mechanisms in Uganda, mainly due to a high reliance OOP and limited prepayment mechanisms. Some limited cross-subsidisation is prevalent through GoU and donor project funding, although there is also fragmentation between GoU and donor project funding, and also within donor project funds, which negatively impacts on creation of larger pools. The lack of effective coordination of donor project funds is a breeding ground for inefficiencies and inequity. Contribution mechanisms for donor project funds result in many fragmented small funding pools that do not promote crosssubsidisation. Compulsory health insurance can either be progressive or regressive, depending on how contributions are structured and who is eligible to access services funded through insurance contributions, but currently there is no compulsory health insurance in Uganda. Public sources of health care financing should be consolidated and should emphasise prepayments for health care.

Conclusion

Health care financing in Uganda is inequitable and fragmented. The GoU needs to promote equitable health care financing by establishing pre-payment schemes, enhancing cross-subsidisation mechanisms and creating large risk pools. It should also address the coordination and integration of financing mechanisms, as part promoting equity in health care financing.

Being a fundamental human right, health care should be accessed by everybody irrespective of income and risk to disease. Since equality is unattainable and potentially undesirable, equity in contributing to the cost of health care should be a major tenet of Uganda's health system. However, Uganda's health system faces the challenge of ensuring sustainability of health sector funding and universal coverage using equitably generated resources. The uncertain nature of illness necessitates a prepayment mechanism to circumvent the drastic implications that arise from the inability to pay for health care. It is therefore imperative that mandatory health insurance schemes are instituted to help raise health sector funds. The design of such a scheme should ensure wide coverage and sustainability. In Uganda, where poverty and lack of access to health care are acute problems, implementing equitable financing mechanisms and insuring against catastrophic health expenditures should be given high priority in national policy making.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from EQUINET (that commissioned and supervised the study, part of whose result we present in this paper). The study was funded by SIDA Sweden. In addition, we acknowledge EQUINET and the Uganda Health Equity Network for capacity support towards the publication of the paper. We sincerely thank the Ministry of Health (Uganda) for giving us the support that enabled us to access relevant literature as well as conduct interviews for this study.

References

- 1.Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2005. World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA58.33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntyre C, Govender V, Buregyeya E, et al. Key issues in equitable health care resource mobilisation in East and Southern Africa. Harare: EQUINET; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zikusooka C, Kyomuhangi R. Private medical prepayment and insurance schemes in Uganda: what can the proposed SHI policy learn from them? Harare: EQUINET; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of health, author. Assessment of public expenditures for the health sector in Uganda: FY2003/4 – 2005/6. Government of Uganda; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health, author. Health Sector Strategic Plan II (2005/6 – 2009/10) I. Kampala: Government of Uganda; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health, author. Annual Health Sector Performance Report (2002/2003) Government of Uganda; 2003. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, author. Annual Health Sector Performance Report (2003/2004) Government of Uganda; 2004. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health, author. Annual Health Sector Performance Report (2004/2005) Government of Uganda; 2005. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health, author. Annual Health Sector Performance Report (2005/2006) Government of Uganda; 2006. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health, author. Annual Health Sector Performance Report (2007/08) Government of Uganda; 2008. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health, author. Annual Health Sector Performance Report (2006/07) Kampala: Government of Uganda; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health, author. Health Financing Strategy. Kampala: Government of Uganda; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of health, author. National Health Accounts. Kampala: Government of Uganda; 2004. Financing Health Services in Uganda 1998/1999–2000/2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIntyre D. Health financing: learning from experience — health care financing in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyomugisha E, Buregyeya E, Ekirapa E, Mugisha JF, Bazeyo W. Building strategies for sustainability and equity of pre-payment schemes in Uganda: Bridging gaps. Hararre: EQUINET; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E, van der Burg H. Equity in the finance of health care: some further international comparisons. Journal of Health Economics. 1999;18:263–290. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntyre D, Govender V, Buregyeya E, et al. Key issues in equitable health care financing in East and Southern Africa. Harare: EQUINET; 2008. EQUINET discussion paper 66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uganda Bureau of Statistics, author. Uganda National Household Survey 2005/2006-Report on the socioeconomic module. Kampala: Government of Uganda; 2006. [Google Scholar]