Abstract

Little is known about the factors that influence the proteasome structures in cells and their activity, although this could be highly relevant to cancer therapy. We have previously shown that, within minutes, irradiation inhibits substrate degradation by the 26S proteasome in most cell types. Here, we report an exception in U87 glioblastoma cells transduced to express the epidermal growth factor receptor vIII (EGFRvIII) mutant (U87EGFRvIII), which does not respond to irradiation with 26S proteasome inhibition. This was assessed using either a fluorogenic substrate or a reporter gene, the ornithine decarboxylase degron fused to ZsGreen (cODCZsGreen), which targets the protein to the 26S proteasome. To elucidate whether this was due to alterations in proteasome composition, we used quantitative reverse transcription-PCR to quantify the constitutive (X, Y, Z) and inducible 20S subunits (Lmp7, Lmp2, Mecl1), and 11S (PA28α and β) and 19S components (PSMC1 and PSMD4). U87 and U87EGFRvIII significantly differed in expression of proteasome subunits, and in particular immunosubunits. Interestingly, 2 Gy irradiation of U87 increased subunit expression levels by 16% to 324% at 6 hours, with a coincident 30% decrease in levels of the proteasome substrate c-myc, whereas they changed little in U87EGFRvIII. Responses similar to 2 Gy were seen in U87 treated with a proteasome inhibitor, NPI0052, suggesting that proteasome inhibition induced replacement of subunits independent of the means of inhibition. Our data clearly indicate that the composition and function of the 26S proteasome can be changed by expression of the EGFRvIII. How this relates to the increased radioresistance associated with this cell line remains to be established.

Introduction

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway degrades most intracellular proteins. Proteasomes exist in several different forms, each focused on degrading primarily different sets of substrates. The 20S core structure contains three different active sites, called β5 (X), β1 (Y), and β2 (Z), responsible for chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and postglutamyl peptide hydrolase–like (caspase-like) proteolytic activity, respectively. The 20S core is activated by binding either 19S or 11S regulatory complexes (1, 2). The 26S proteasome, which is composed of a 20S core and 19S regulatory subunits, plays an important role in regulating expression of signaling molecules in an ATP-dependent manner (3–5). The 19S regulatory subunits are composed of a base structure containing six ATPase subunits and two non-ATPase subunits, and a lid with non-ATPase subunits. In contrast, binding of 20S core structure to 11S activator components, PA28α and PA28β, is induced by proinflammatory signals such as IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α. These stimuli also replace the enzymatic core subunits, X, Y, or Z, with corresponding immunosubunits Lmp7, Lmp2, or Mecl1 (6, 7). The main substrates of the 20S-11S complex are partially degraded proteins and peptides and the process is ATP/ubiquitin independent (8).

Proteasome composition and number, and hence the rate and specificity of proteolysis, vary by cell type and pathologic condition. Cancer cells generally display higher levels of proteasome activity than normal cells, and their increased degradation of regulatory molecules such as p27 and transforming growth factor-β have been linked to loss of growth control (9–11). This, and the differential responses cancer cells display to proteasome inhibition, makes the proteasome a valid target for cancer therapy. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade) was first approved for treatment of refractory multiple myeloma and its success has led to the development of additional proteasome inhibitors (12, 13).

We and others (14–18) have shown that drugs that inhibit proteasome activity, such as bortezomib, radiosensitize cancer cells. In our case, this was a natural progression from our finding that acute irradiation of cells rapidly inhibits all three major enzyme activities of the 26S proteasome, with activity being gradually restored over 24 hours. Irradiation of a wide range of cancer cell lines caused a 25% to 60% decrease in the rate at which proteasomes cleave fluorogenic substrates (19). This observation was dose independent with maximum inhibition even at low doses. The inhibition of 26S proteasome function was correlated to increased expression of IkB-β, a substrate of the 26S proteasome at low doses of radiation (19), and a general increase in ubiquitinated proteins (20). Remarkably, the activities of purified proteasome preparations irradiated on ice were also reduced (19, 20), indicating that the proteasome is a direct target of radiation. Further study showed that only 26S, not 20S or 20S +11S, proteasomes are affected by radiation and its inhibition is ATP dependent, suggesting that ATPase subunits of the 19S cap are probable mediators of the response (20).

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common brain cancer of adults and the median survival time of patients with GBM is 12 months from diagnosis (21). The most commonly altered gene in GBM is epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), with overexpression occurring in 40% to 50% of cases, and nearly 50% of these coexpress mutant EGFRs, mostly the type III EGFR variant (EGFRvIII; ref. 22). The EGFRvIII mutant contains an in-frame deletion of amino acids 6 to 273, resulting in a ligand-independent, constitutively active oncoprotein. EGFRvIII expression has been linked to poor prognosis (23, 24) and implicated in modulating radiosensitivity (25). Ionizing radiation in the therapeutic dose range of 1 to 5 Gy increases tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR wild-type and EGFRvIII, activating mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways in Chinese hamster ovary cells (26). In addition, Lal et al. (27) reported that transcripts of molecular effectors of tumor invasion such as extracellular matrix components, metalloproteases, and a serine protease were up-regulated in an EGFRvIII-expressing GBM cell line. We also noted that EGFRvIII expression led to radioresistance of U87 GBM cells and we asked whether this pathway might also affect proteasome composition and radiation-induced inhibition of proteasome function.

Results

Radiation-Induced Proteasome Inhibition Is Observed in U87 but not in U87EGFRvIII Cells

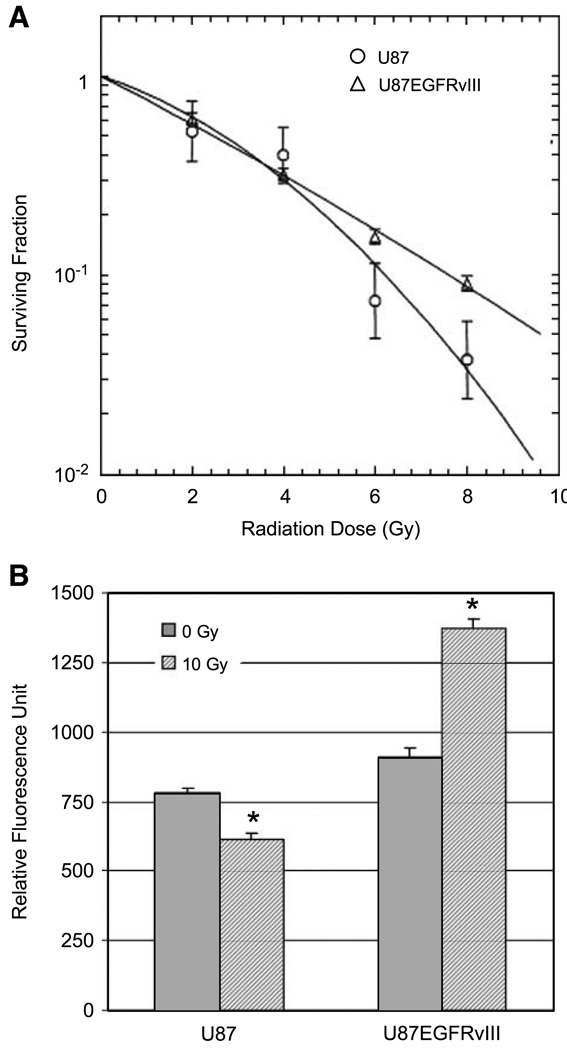

First, a clonogenic survival assay was used to determine how chronic EGFR signaling modulates the response of U87 cells to single doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy ionizing radiation (Fig. 1A). U87 is a radioresistant cell line; however, transduction with EGFRvIII made it even more radioresistant, although this was only evident at higher radiation doses.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of ionizing radiation on U87 and U87EGFRvIII cell lines. A. Clonogenic assay comparing U87EGFRvIII with the parental line U87. Cells were trypsinized; irradiated with 2, 4, 6, or 8 Gy; and then plated in 100-mm dishes in triplicates. After 14 d, the colonies were fixed and stained with crystal violet. The colonies containing >50 cells were counted. Radiological variables were obtained from a linear-quadratic fit: U87 α = 0.175, β = 0.031, α/ β = 5.57; U87EGFRvIII α = 0.272, β = 0.004, α/ β = 66.4. B. Proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity was measured by fluorogenic assay using Suc-LLVY-AMC peptide following 10 Gy irradiation. The average fluorescent value in quadruplicate from a representative experiment is shown. *, significant differences between 0 and 10 Gy for each cell line calculated by Student’s t test (P < 0.001).

We had previously shown that irradiation of a wide range of cell types slows the rate at which fluorogenic substrates are degraded through the proteasome. To determine if EGFRvIII expression alters radiation-induced proteasome inhibition, we compared the U87 and U87EGFRvIII cell lines using the same fluorogenic assay for chymotrypsin-like activity after 10 Gy irradiation using Suc-LLVY-AMC peptide (Fig. 1B). A 16% higher (P < 0.01) proteasomal activity was observed in extracts from untreated U87EGFRvIII compared with the untreated U87 cell line. U87EGFRvIII also responded to irradiation differently from U87. Irradiation at 10 Gy inhibited 22% (P < 0.001) of the proteasome activity in U87, whereas irradiation actually increased activity in U87EGFRvIII cells (P < 0.001), which is in our experience unique and exceptional. Irradiation at 2 Gy also inhibited the proteasome activity in U87 (23%, P < 0.0001, data not shown) but not in U87EGFRvIII (2% inhibition, not significant).

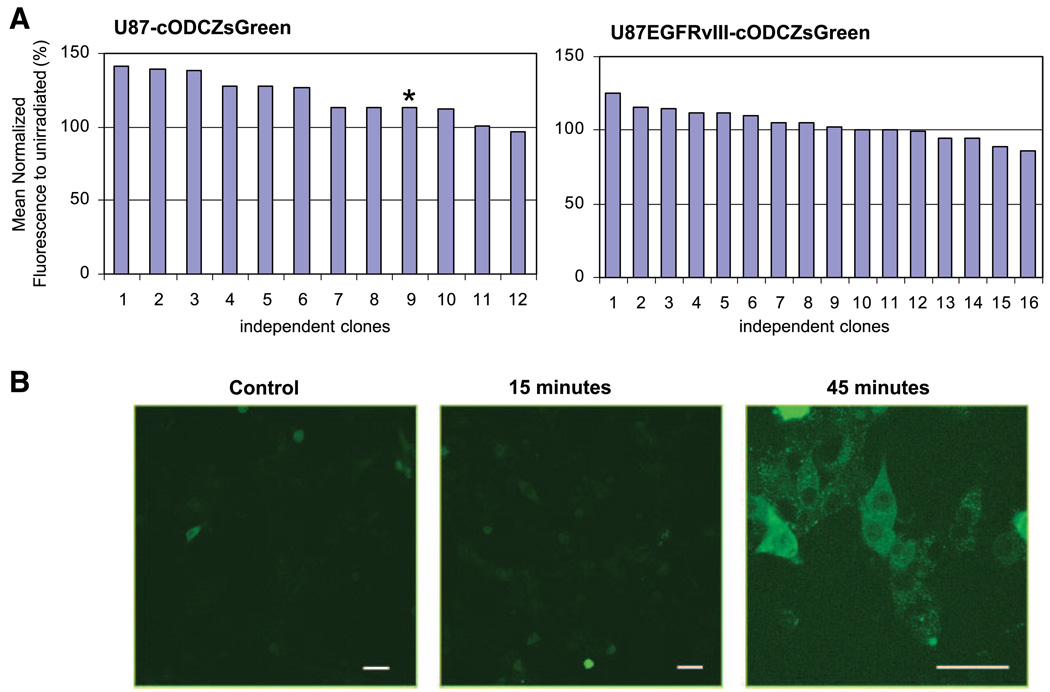

Irradiation Inhibits 26S Proteasome Activity in U87 but not in U87EGFRvIII Cells

To determine if protein degradation by the 26S proteasome was similarly inhibited in living cells by irradiation, a reporter gene assay using the cODCZsGreen fusion system was used (Fig. 2). The murine ODC degron (cODC) targets proteins for degradation specifically through the 26S proteasome (28–30) independent of ubiquitin conjugation. The fusion of cODC to fluorescent proteins produces a reporter gene product that does not accumulate in normal conditions but can be used to assess proteasome inhibition (31). We generated stable clones of U87- and U87EGFRvIII-expressing cODCZsGreen fusion protein and examined 12 clones of U87-cODCZsGreen and 16 clones of U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen to account for possible clonal variation. These were irradiated at 10 Gy, harvested after 6 hours, and the fluorescence of each clone (paired 0 and 10 Gy) was determined using flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence of each independent clone irradiated at 10 Gy was then normalized to that of the corresponding untreated control (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the reduction of proteasome activity in U87 seen in Fig. 1, 26S proteasome function was inhibited by irradiation, resulting in a fluorescence increase in most of the U87-cODCZsGreen clones (P < 0.005), whereas the fluorescence of U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen clones was little altered after irradiation (P = 0.298). The average increase in the mean fluorescence after irradiation was 29.5% for U87-cODCZsGreen and 1.7% for U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of cODCZsGreen fluorescence of U87-cODCZsGreen and U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen stable lines after radiation. A. The accumulation of proteasome substrate, cODC, following compromised proteasome function was measured by the expression of cODCZsGreen in unirradiated and irradiated clones using flow cytometry. Twelve clones of U87-cODCZsGreen and 16 clones of U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen cells were irradiated at 10 Gy and their fluorescence was assessed 6 h after irradiation. Columns, mean fluorescence of individual irradiated clones measured by flow cytometry after normalization to that of its untreated control and plotted as a percentile (the values above 100% reflect the increase above untreated). The inhibition of proteasome activity following radiation, which resulted in the increased fluorescence, was statistically significant in U87-cODCZsGreen (P < 0.005, calculated by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test) whereas it was not statistically significant in U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen (P = 0.298). B. Three clones of U87-cODCZsGreen were further analyzed by confocal microscopy and a representative image following irradiation (marked as * in A) is shown. Bar, 50 µm. The inhibition of proteasome function was detected in U87 as early as 15 min and prominent at 45 min after 2 Gy irradiation.

To further support the flow cytometry results and to determine the subcellular localization of the fluorescence, clone 9 of U87-cODCZsGreen was additionally analyzed using confocal microscopy. Cells were plated overnight and fluorescence was detected after cells were irradiated with 2 Gy. Accumulation of ODC in U87-cODCZsGreen was observed as early as 15 minutes after irradiation and became prominent in the perinuclear region by 45 minutes (Fig. 2B). Similar spatial accumulation of fluorescence was observed in a different cell line.3 This result shows that irradiation affects degradation of physiologic substrates as well as of fluorogenic peptides in U87 cells but not in U87EGFRvIII cells.

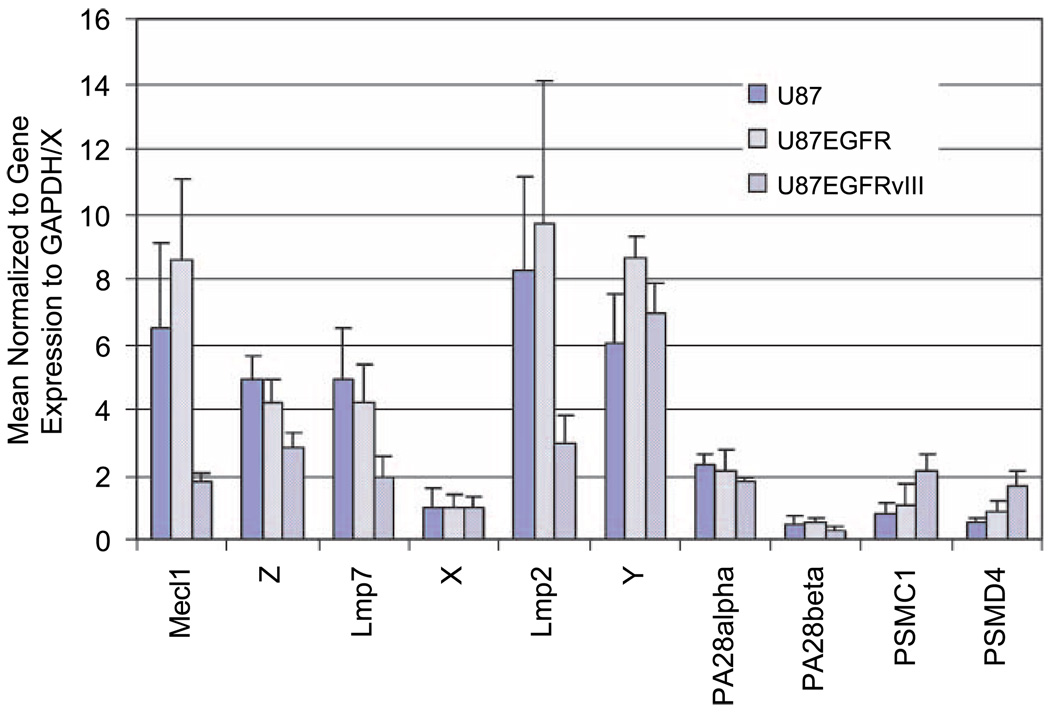

Proteasome Composition Varies between U87 and Its Isogenic Derivatives

To determine if the differential cellular response to irradiation of U87 and U87EGFRvIII cells could be attributed to differences in proteasome composition, we next measured the proteasome subunit expression of U87 isogenic cell lines. The mRNA expression of 10 proteasome subunits was measured in U87, U87EGFR, and U87EGFRvIII cells using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). These include the constitutive subunits (X, Y, Z), their inducible counterparts (Lmp7, Lmp2, Mecl1), the 11S subunits (PA28 α and β), and the 19S components (PSMC1 and PSMD4). The expression of each subunit was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). For each cell line, gene expression values are shown relative to the expression of the constitutive subunit X, which was set equal to 1 (Fig. 3). The U87EGFRvIII cell line displayed a very different expression pattern compared with U87 or U87EGFR, which were similar to each other. Expression differences were most prevalent among the immunosubunits (Lmp7, Lmp2, Mecl1), which were markedly higher in the parental line and down-regulated in the EGFRvIII cells. 19S regulator and 11S activator levels seemed to be similar in the different isogenic lines.

FIGURE 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of proteasome subunits from U87, U87EGFR, and U87EGFRvIII. Cells in logarithmic growth were used for mRNA expression analysis of 10 different proteasome subunits. PCR reactions were quantified by SyberGreen in the My iQ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The expression of each gene was normalized to a housekeeping gene, GAPDH, and compared with a constitutive subunit X (where the X value was set equal to 1).

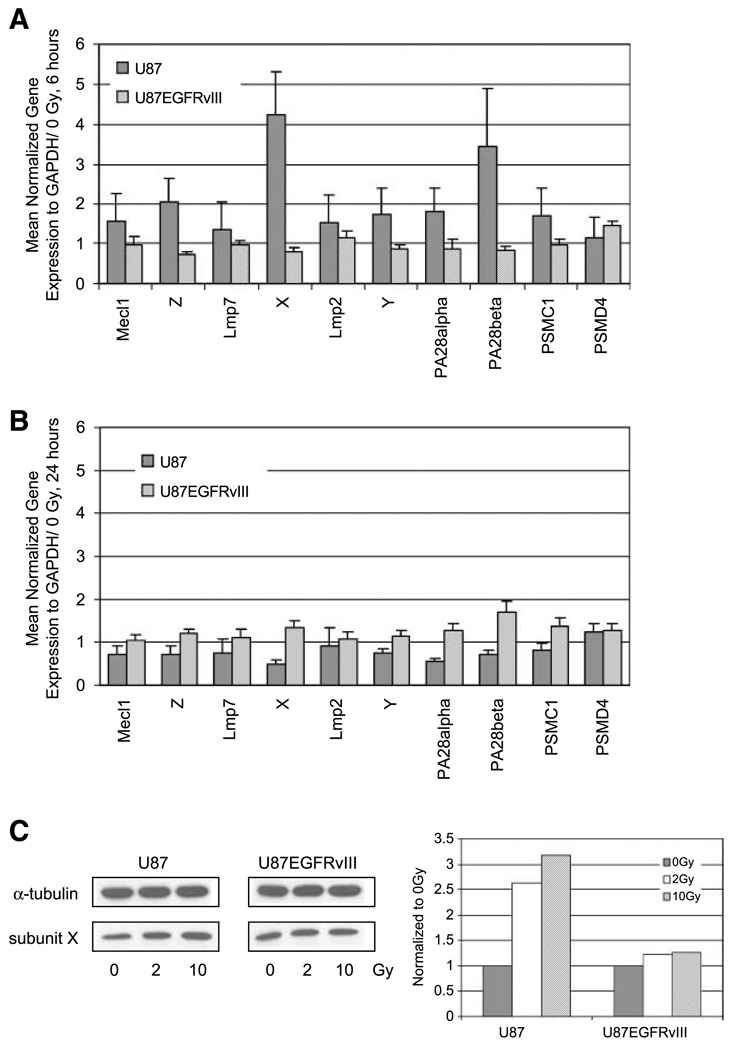

Irradiation Increased the mRNA Levels for All of the Proteasome Subunits in U87, but Little in the Radioresistant U87EGFRvIII

Having determined that the proteasomes of the more radioresistant U87EGFRvIII cell line were significantly different from those of U87 in their subunit composition and in their resistance to radiation-induced inhibition, we then asked whether ionizing radiation changes the rate of synthesis of proteasome mRNA and whether this is altered by constitutively active EGFR signaling. We measured the mRNA expression of 10 different proteasome subunits in U87 and U87EGFRvIII cells 6 and 24 hours after irradiation with 2 Gy by qRT-PCR. GAPDH-normalized expression was compared with mRNA expression levels of nonirradiated samples (expression of each subunit at 0 Gy = 1). At 6 hours after 2 Gy irradiation, the expression of all proteasome subunits tested in U87 cells was increased by 16% to 324% (Fig. 4A). In particular, all three constitutive subunits of the 20S core were induced by irradiation (summarized in Fig. 5B). Consistent with the increase of proteasome mRNA, levels of the proteasome substrate c-myc were decreased by 30% (data not shown). On the other hand, in U87EGFRvIII cells, the extent of up-regulation after 2 Gy irradiation was minimal. At 24 hours after irradiation, neither cell line showed significant changes in their expression compared with untreated controls (Fig. 4B), in keeping with restoration of normal proteasome activity.

FIGURE 4.

mRNA and protein analysis of proteasome subunits in U87 and U87EGFRvIII cell lines after ionizing radiation. A. qRT-PCR analysis at 6 h after 2 Gy radiation. B. qRT-PCR analysis at 24 h after 2 Gy radiation. The expression of each gene was normalized to GAPDH and then compared with 0 Gy control samples (0 Gy equals 1). An increase in expression was observed in all of the proteasome subunits of U87 cell line at 6 h, whereas an increase was no longer observed at 24 h after irradiation. C. Immunoblot analysis at 6 h after irradiation with 2 or 10 Gy. Immunoblotting was done with an anti-human 20S proteasome subunit β5 polyclonal antibody. An anti – α-tubulin antibody was used as a loading control. Each band was quantified using Image J (NIH), normalized to α-tubulin, and then compared with 0 Gy sample (0 Gy equals 1).

FIGURE 5.

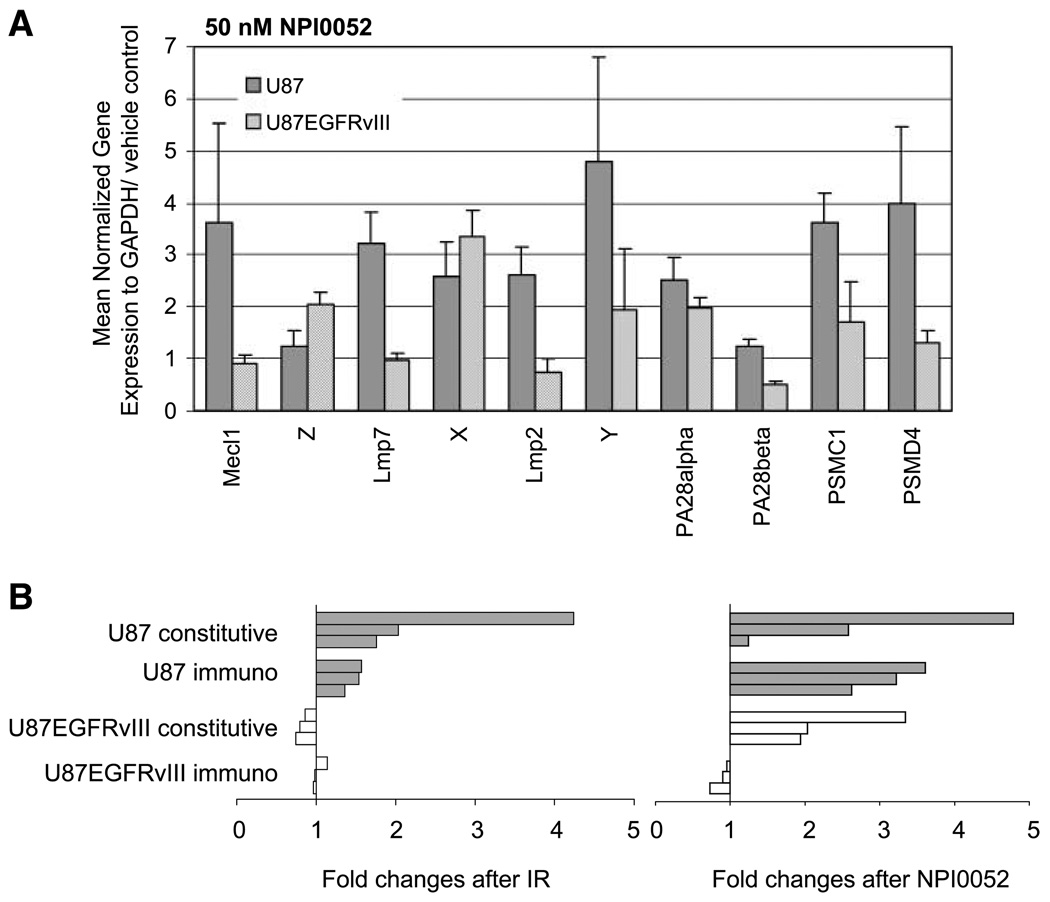

Gene expression of proteasome subunits after proteasome inhibitor treatment. A. Cells were treated with 50 nmol/L NPI0052 or vehicle (0.25% DMSO) for 3 h then washed, and RNA was collected 6 h posttreatment. The expression of each gene was normalized to GAPDH and 0 nmol/L NPI0052. Unlike radiation, NPI0052 induced the mRNA expression of constitutive subunits in U87EGFRvIII. B. A summary diagram of mRNA expression changes in proteasome subunits. Fold changes of constitutive subunits (X, Y, Z) and immunosubunits are shown after ionizing radiation or a proteasome inhibitor NPI0052 treatment (filled columns, U87; open columns, U87EGFRvIII). The constitutive subunits were induced by NPI0052 but not by irradiation in U87EGFRvIII.

The increased protein expression of X subunit (β5, chymotrypsin-like activity) was also observed by Western blot in U87 whole-cell lysates prepared 6 hours after 2 and 10 Gy irradiation, whereas there was no change in protein expression in U87EGFRvIII (Fig. 4C). This was the subunit that changed most by qRT-PCR. Radiation-induced changes in Y and Z subunit proteins, which changed less, were not detectable in either U87 or U87EGFRvIII (data not shown), which may have been due to the relative insensitivity of the method.

A Proteasome Inhibitor Shows a Similar Effect as Irradiation on mRNA Proteasome in U87 Cells

To determine if the radiation-induced induction of proteasome subunits was simply a consequence of proteasome inhibition, or something restricted to irradiation, we used an orally bioactive proteasome inhibitor NPI0052 (12) that binds directly to all three protease sites and that has been suggested to be more potent than PS341 (bortezomib). In our system, NPI0052 inhibited >99% of proteasome activity in both U87 and U87EGFRvIII cell lines when they were treated at 50 nmol/L for 3 hours (data not shown). If proteasome inhibition was required for new gene expression, we anticipated that NPI0052 would induce proteasome mRNA expression in both U87 and U87EGFRvIII cells, whereas irradiation would only do so in the former. The results are shown in Fig. 5A, with the expression of each gene normalized to GAPDH and compared with vehicle controls (0 nmol/L NPI0052 = 1). Treatment with NPI0052 induced the expression of almost all the subunits tested in U87, including both core constitutive subunits and immunosubunits (also summarized in Fig. 5B). In U87EGFRvIII cells, NPI0052 induced six subunits, including core constitutive subunits but not immunosubunits. The ability of NPI0052, but not irradiation, to induce constitutive core subunits may be related to the fact that the drug inactivates these subunits, whereas irradiation acts on the 19S cap (20). The inability of NPI0052 to induce immunoproteasome production in U87EGFRvIII cells is consistent with the fact that these subunits are poorly expressed in such cells (Fig. 3). When the U87 cell line was treated with NPI0052 followed by irradiation, radiation did not appreciably augment the changes in subunits brought about by NPI0052 alone (data not shown).

Discussion

The U87EGFRvIII cell line is more radioresistant than the U87 parental line, as shown using a clonogenic survival assay (Fig. 1A). Modulation of radiosensitivity by the EGFRvIII mutant has been reported in vitro and in vivo (26, 32). In in vitro studies, the expression of EGFRvIII by either transfection or adenoviral delivery enhanced radioresistance in Chinese hamster ovary and U373 cell lines, respectively. Our laboratory previously observed that the activity of the proteasome considerably varies between cell lines, but is reduced 25% to 60% by ionizing radiation in all of the tumor cell lines tested (33, 34). In this study, irradiation decreased proteasome activity by 22% in U87. Although the extent of the inhibition may seem small, it obviously can affect the expression levels of short-lived proteins, as can be seen by the rapid accumulation of the reporter gene, cODCZsGreen, after 2 Gy irradiation. It has been well-established that this protein is targeted to the 26S proteasome for degradation without ubiquitination (28–30) and its use allows the 26S proteasome activity to be evaluated without interference from effects of radiation on the ubiquitin system. This also clearly indicates that radiation-induced proteasome inhibition has physiologic significance and is likely to be highly relevant to radiation-induced changes in levels of important signaling molecules, such as p53, p21, etc. Interestingly, and uniquely, no inhibition was observed in the U87EGFRvIII cell line after irradiation, and indeed an increase in activity was seen.

In addition to the resistance to radiation cytotoxicity and lack of radiation-induced proteasome inhibition conferred by EGFRvIII expression, chronic EGFR signaling also seems to modulate proteasome composition. The mRNA proteasome subunit profile, and in particular that of the immunosubunits of the core structure, is altered in U87EGFRvIII. The lack of core immunosubunits in EGFRvIII is of interest because this may represent a mechanism of immune escape that is cohesively regulated with overactivation of the EGFR pathway. The differential display of proteasome subunits seems to be specific for EGFRvIII because EGFR wild-type (Fig. 3) or PTEN (not shown) expression did not significantly alter the proteasomal composition from that of the parental line.

The reasons why cell lines differ so much in proteasome composition and activity are uncertain, but there is increasing evidence that the proteasome system rapidly responds to cell environment and stress challenges, which could have consequences in terms of cancer aggression and response to therapy (35). From our data, one can speculate that chronic EGFR signaling in U87EGFRvIII might change the phosphorylation status of proteasome subunits, which may in turn render human glioma tumor cells resistant to radiotherapy. Roles for phosphorylation of proteasomes have been suggested by others. IFN-γ decreases the level of phosphorylation of proteasome α subunits, C8 (α7) and C9 (α3; ref. 36), and the phosphorylation of C8 by casein kinase 2 was suggested to increase the stability of the 26S proteasome (37). Satoh et al. (38) suggested that dephosphorylation of proteasome structures elicits the dissociation of the 26S proteasome to the 20S proteasome and the regulatory complex. In addition, phosphorylation of several ATPase subunits of 26S in human lung cancer cell lines was found by two-dimensional gel analysis (39). Follow-up experiments to determine the phosphorylation status and the targeted proteasome subunits of EGFR pathway using proteomics tools and/or small-molecule inhibitors of this pathway would be helpful to understand the mechanism of the radiation resistance conferred by EGFRvIII. It is worth noting that radiation leads to rapid phosphorylation of EGFR and EGFRvIII, and to activation of downstream pathways (32, 40) that might lead to changes in proteasome phosphorylation status and activity.

Previous work from our laboratory showed that irradiation decreases proteasome function within minutes and that activity recovers over the next 24 hours (20). The mechanism of recovery is not known, but in this study, 2 Gy irradiation increased the expression levels for proteasome subunits at 6 hours in U87 cells and by 24 hours, proteasome subunit mRNAs were restored to preradiation levels. In the U87EGFRvIII cell line, where the decrease in activity was absent, there was little induction of mRNA for proteasomes following irradiation. This is consistent with increased transcription being a mechanism for the recovery of proteasome activity after radiation-induced inhibition. The ability of the proteasome system to respond rapidly to challenge is consistent with the finding of alteration of proteasome subsets in many microarray studies, including responses to irradiation (41). Snyder et al. observed that down-regulation of the 26S proteasome subunits ATPase 2 and E2A/Rad6 was associated with radiation-induced chromosomal instability. On the other hand, irradiation induced protein expression of 20S proteasome subunits α-1 and α-6 after 12 hours. Irradiation has also been reported to down-regulate PA28-γ in the T-lymphocyte leukemic cell line MOLT-4 (shown by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis; ref. 42). Our data would suggest that any radiation-induced change in proteasome subunits may depend on the cell line and pathways that are activated.

Our findings strongly support the hypothesis that the proteasome structure is a direct target of irradiation and differential expression induced following irradiation might further modify changes in the degradation rate of regulatory proteins as well as the recognition of cancers by the immune system. Further studies using approaches such as electron microscopy would be helpful to address the recovery mechanism of proteasome function because the analysis of mRNA/protein expression does not distinguish assembled proteasomes from dissociated proteasomes.

The increase in proteasome mRNA following irradiation might logically be thought of as a result of proteasome inhibition caused by any mechanism. To determine if this was the case, we used a proteasome inhibitor, NPI0052, that induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells primarily through caspase-8–mediated signaling pathways (12). We observed cytotoxicity of NPI0052 on both U87 and U87EGFRvIII cells within 24 hours, whereas irradiation did not cause cell death in this time frame. Unlike irradiation, NPI0052 inhibited chymotrypsin-like activity almost completely in both U87 and U87EGFRvIII. It is interesting that both NPI0052 and 2 Gy irradiation, which caused very different levels of inhibition, induced proteasome mRNA expression to a comparable degree in the U87 cells at 6 hours of treatment. In U87EGFRvIII cells, NPI0052, in contrast to irradiation, increased expression of core constitutive components but not immunosubunits. This perhaps was a reflection of the lack of expression of these subunits in the untreated cells, suggesting that an inhibitory mechanism may be operating to block their expression. In any event, these data imply that cells treated with two separate therapies share the same mechanism of recovery, at least in part. What is clear is that there is a great deal that we do not know about the regulation of proteasome subunit production but that this system is highly dynamic and plastic and capable of responses that are of physiologic importance.

In summary, we have shown using fluorogenic peptides and a physiologic substrate of the 26S proteasome that irradiation inhibits the proteasome activity of U87 but not its radioresistant variant U87EGFRvIII. EGFRvIII expression also seems to alter the molecular composition of the proteasomes, with a loss of immunosubunits. Radiation-induced proteasome inhibition seems to be followed by an increase in mRNA production, which suggests that transcription might be a mechanism of proteasome recovery after irradiation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

Human GBM cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific) and penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine (Invitrogen). The human glioblastoma cell line U87MG (U87) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The U87EGFR wild-type (U87EGFRwt) and U87EGFRvIII cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. Paul Mischel (Department of Pathology, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA). These cell lines had been derived by retroviral transduction of U87 cell line with pLPCX constructs that contain human EGFR wild-type or EGFRvIII cDNA, respectively, as described earlier (43).

Proteasome Inhibitor

The proteasome inhibitor NPI0052 was a kind gift from Nereus Pharmaceuticals.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then treated with DNase 1, amplification grade (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was carried out using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Quantitative PCR was done in the My iQ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) using the 2× iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Quantitative PCR for each sample was run in triplicate and each reaction contained 1 µL of cDNA in a total volume of 20 µL. Ct for each gene was determined after normalization to GAPDH, and Ct was calculated relative to the designated reference sample. Gene expression values were then set equal to 2−Ct as described (Applied Biosystems). All PCR primers were synthesized by Invitrogen and designed for the human sequence. The following primer pairs (written 5′ to 3′) were used at the indicated final concentration: GAPDH (at 600 nmol/L), human c-myc (AGCGACTCTGAGGAGGAACA and CTCTGACCTTTTGCCAGGAG at 300 nmol/L), Lmp2 (ATGCTGACTCGACAGCCTTT and GCAATAGCGTCTGTGGTGAA at 300 nmol/L), Y (AGGAGAAAGATGGCGGCTAC and AGGACCCAGTGGTTGTTCTG at 300 nmol/L), Mecl1 (GTGCTAGAAGACCGGTTCCA and CTCTGTGGGTGAGCTCAGTG at 300 nmol/L), Z (GGAGGAGGAAGCCAAGAATC and CTTCCAGCACCTCAATCTCC at 300 nmol/L), Lmp7 (ATGTCAGTGACCTGCTGCAC and CTGCTGAGCCCGTACTCTCT at 300 nmol/L), X (ACGTGGACAGTGAAGGGAAC and CTGCATCCACCCTCTTTCAG at 300 nmol/L), 11S PA28 α (AGACAAAGGTCCTCCCTGTG and CTGGACAGCCACTCCAAAAT at 300 nmol/L), 11S PA28 β (ACTCCCTCAATGTGGCTGAC and GCAGGGACAGGACTTTCTCA at 300 nmol/L), 19S ATPase PSMC1 (GACCCCGATGTCAGTAGGAA and GGATCCGTGTCATCCATCAG at 300 nmol/L), 19S non-ATPase PSMD4 (CAACGTGGGCCTTATCACAC and ATTGTCCTCCACTGGGCTTC at 300 nmol/L). The specificity of primers was validated using melting curve and on the gel.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole-cell lysates were prepared using M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Pierce) with protease inhibitor cocktails (EMD Biosciences). Equal amounts of protein were run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Immunoblotting was done with an anti-human 20S proteasome subunit β5 polyclonal AB (Biomol International, L.P.). An anti– α-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody (EMD Biosciences) was used as a loading control. Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase– conjugated secondary antibodies were from GE Healthcare UK Limited. Immunoblots were developed using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce).

Irradiation

Exponentially growing cells were irradiated using a 137Cs laboratory irradiator (Mark1, JLShephard) at a dose rate of 5.0 Gy/min.

Clonogenic Survival Assay

Exponentially growing cells were trypsinized, counted, and diluted accordingly. These cell suspensions were then irradiated at 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy and plated in 100-mm dishes in triplicate. After 14 d, colonies were fixed and stained with crystal violet in 50% ethanol. Colonies consisting of >50 cells were counted to determine surviving fractions.

Fluorogenic Assay

Chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity was measured using a fluorogenic peptide substrate, Suc-LLVY-AMC (Sigma-Aldrich). Ten micrograms of cell extracts in buffer I (50 mmol/L Tris, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 mmol/L DTT, 2 mmol/L ATP) combined with the substrate at 100 µmol/L were added into 96-well black plate (Corning, Inc.), and the fluorescence of the released AMC was measured for 30 min at 37°C using a Tecan SPECTRAFluor Plus fluorometer (TECAN).

Generation of Stable Cell Lines Expressing ZsGreenODC Fusion Protein Using Retroviral Transduction

The degron from the carboxy-terminal 37 amino acids of ornithine decarboxylase fused to ZsGreen (cODCZsGreen) was digested with BglII and NotI from pZsProsensor-1 (BD Biosciences) and cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the retroviral vector pQCXIN (BD Biosciences) using the NotI-EcoRI DNA oligonucleotide adaptor (EZ Clone Systems). pQCXIN/cODCZsGreen was transfected into GP2-293 pantropic retroviral packaging cells (BD Biosciences) and the collected retrovirus was used to infect U87 and U87EGFRvIII cell lines. Infected cells were then selected under 800 µg/mL of G418 (Invitrogen): U87-cODCZsGreen and U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen. To select transduced cells, single-cell clones of U87-cODCZsGreen or U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen cells were isolated by plating dilute suspensions and selecting clones using cloning cylinders (Fisher Scientific).

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis

Clones were screened for cODCZsGreen fluorescence by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Twelve clones of U87-cODCZsGreen and 16 clones of U87EGFRvIII-cODCZsGreen cell lines were irradiated at 10 Gy and the fluorescence was measured 6 h later. Approximately 106 cells per each clone were resuspended in 2 mL isotone and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Confocal Microscopy

Approximately 106 cells were plated in 35-mm glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek Corporation) overnight. Green fluorescence was detected using a TCS SP MP Inverted Confocal Microscope (Leica) after cells were irradiated with 2 Gy.

Statistical Analysis

For quantification of fluorescence due to radiation-induced proteasome inhibition, the flow cytometry data of each clone were analyzed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test. To determine P values, the means of fluorescence for each clone with or without radiation treatment were paired.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul Mischel for the U87EGFRwt and U87EGFRvIII cell lines, and Emily Lieu for technical assistance.

Grant support: National Cancer Institute grant CA-87887 (W.H. McBride).

Footnotes

J.M. Brush, et al. Imaging of radiation effects on cellular 26S proteasome function in situ , submitted for publication.

References

- 1.Harris JL, Alper PB, Li J, Rechsteiner M, Backes BJ. Substrate specificity of the human proteasome. Chem Biol. 2001;8:1131–1141. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Rechsteiner M. Molecular dissection of the 11S REG (PA28) proteasome activators. Biochimie. 2001;83:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams J. The proteasome: structure, function, and role in the cell. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29 Suppl 1:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coux O. The 26S proteasome. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2002;29:85–107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56373-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg AL. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akiyama K, Kagawa S, Tamura T, et al. Replacement of proteasome subunits X and Y by LMP7 and LMP2 induced by interferon-γ for acquirement of the functional diversity responsible for antigen processing. FEBS Lett. 1994;343:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaczynska M, Rock KL, Spies T, Goldberg AL. Peptidase activities of proteasomes are differentially regulated by the major histocompatibility complex-encoded genes for LMP2 and LMP7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9213–9217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride WH, Iwamoto KS, Syljuasen R, Pervan M, Pajonk F. The role of the ubiquitin/proteasome system in cellular responses to radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5755–5773. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiarle R, Budel LM, Skolnik J, et al. Increased proteasome degradation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 is associated with a decreased overall survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95:619–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loda M, Cukor B, Tam SW, et al. Increased proteasome-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 in aggressive colorectal carcinomas. Nat Med. 1997;3:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Laiho M. On and off: proteasome and TGF-β signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chauhan D, Catley L, Li G, et al. A novel orally active proteasome inhibitor induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells with mechanisms distinct from bortezomib. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Bortezomib (PS-341): a novel, first-in-class proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma and other cancers. Cancer Control. 2003;10:361–369. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goel A, Dispenzieri A, Geyer SM, Greiner S, Peng KW, Russell SJ. Synergistic activity of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 with non-myeloablative 153-Sm-EDTMP skeletally targeted radiotherapy in an orthotopic model of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:4063–4070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel A, Dispenzieri A, Greipp PR, Witzig TE, Mesa RA, Russell SJ. PS-341-mediated selective targeting of multiple myeloma cells by synergistic increase in ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pervan M, Pajonk F, Sun JR, Withers HR, McBride WH. Molecular pathways that modify tumor radiation response. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:481–485. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200110000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo SM, Tepper JE, Baldwin AS, Jr, et al. Enhancement of radiosensitivity by proteasome inhibition: implications for a role of NF-κB. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber CN, Cerniglia GJ, Maity A, Gupta AK. Bortezomib sensitizes human head and neck carcinoma cells SQ20B to radiation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:156–159. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.2.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pajonk F, McBride WH. Ionizing radiation affects 26s proteasome function and associated molecular responses, even at low doses. Radiother Oncol. 2001;59:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pervan M, Iwamoto KS, McBride WH. Proteasome structures affected by ionizing radiation. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:381–390. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF. Targeted molecular therapy of GBM. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleihues P, Sobin LH. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Cancer. 2000;88:2887. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12<2887::aid-cncr32>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heimberger AB, Hlatky R, Suki D, et al. Prognostic effect of epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma multiforme patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1462–1466. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelloski CE, Ballman KV, Furth AF, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III status defines clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2288–2294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lammering G, Hewit TH, Holmes M, et al. Inhibition of the type III epidermal growth factor receptor variant mutant receptor by dominant-negative EGFR-CD533 enhances malignant glioma cell radiosensitivity. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6732–6743. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lammering G, Hewit TH, Valerie K, et al. EGFRvIII-mediated radioresistance through a strong cytoprotective response. Oncogene. 2003;22:5545–5553. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lal A, Glazer CA, Martinson HM, et al. Mutant epidermal growth factor receptor up-regulates molecular effectors of tumor invasion. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3335–3339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghoda L, Sidney D, Macrae M, Coffino P. Structural elements of ornithine decarboxylase required for intracellular degradation and polyamine-dependent regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2178–2185. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoyt MA, Coffino P. Ubiquitin-free routes into the proteasome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:1596–1600. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Pickart CM, Coffino P. Determinants of proteasome recognition of ornithine decarboxylase, a ubiquitin-independent substrate. EMBO J. 2003;22:1488–1496. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paddison PJ, Silva JM, Conklin DS, et al. A resource for large-scale RNA-interference-based screens in mammals. Nature. 2004;428:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature02370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lammering G, Valerie K, Lin PS, Hewit TH, Schmidt-Ullrich RK. Radiation-induced activation of a common variant of EGFR confers enhanced radioresistance. Radiother Oncol. 2004;72:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride WH, Pajonk F, Chiang CS, Sun JR. NF-κB, cytokines, proteasomes, and low-dose radiation exposure. Mil Med. 2002;167:66–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pajonk F, McBride WH. The proteasome in cancer biology and treatment. Radiat Res. 2001;156:447–459. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0447:tpicba]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glickman MH, Raveh D. Proteasome plasticity. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3214–3223. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bose S, Brooks P, Mason GG, Rivett AJ. γ-Interferon decreases the level of 26 S proteasomes and changes the pattern of phosphorylation. Biochem J. 2001;353:291–297. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bose S, Stratford FL, Broadfoot KI, Mason GG, Rivett AJ. Phosphorylation of 20S proteasome α subunit C8 (α7) stabilizes the 26S proteasome and plays a role in the regulation of proteasome complexes by γ-interferon. Biochem J. 2004;378:177–184. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satoh K, Sasajima H, Nyoumura KI, Yokosawa H, Sawada H. Assembly of the 26S proteasome is regulated by phosphorylation of the p45/Rpt6 ATPase subunit. Biochemistry. 2001;40:314–319. doi: 10.1021/bi001815n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mason GG, Murray RZ, Pappin D, Rivett AJ. Phosphorylation of ATPase subunits of the 26S proteasome. FEBS Lett. 1998;430:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00676-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Contessa JN, Hampton J, Lammering G, et al. Ionizing radiation activates Erb-B receptor dependent Akt and p70 S6 kinase signaling in carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:4032–4041. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snyder AR, Morgan WF. Radiation-induced chromosomal instability and gene expression profiling: searching for clues to initiation and perpetuation. Mutat Res. 2004;568:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szkanderova S, Vavrova J, Hernychova L, Neubauerova V, Lenco J, Stulik J. Proteome alterations in γ-irradiated human T-lymphocyte leukemia cells. Radiat Res. 2005;163:307–315. doi: 10.1667/rr3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang MY, Lu KV, Zhu S, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition promotes response to epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors in PTEN-deficient and PTEN-intact glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7864–7869. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]