Abstract

The transcriptional silencing of some cell cycle inhibitors and tumor suppressors, such as p16 and RARβ2, by DNA hypermethylation at CpG islands is commonly found in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. We examined the effects of the DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt) inhibitor 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine (5-Aza, 0.25 mg/kg body weight), all-trans retinoic acid (RA, given at 100 µg/kg body weight and 1 mg/kg body weight, respectively), and the combination of 5-Aza and the low dose RA on murine oral cavity carcinogenesis induced by the carcinogen 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO) in a mouse model. All the drug treatments were performed for 15 weeks after a 10-week 4-NQO treatment. Mice in all drug treatment groups showed decreases in the average numbers of neoplastic tongue lesions. The combination of 5-Aza and RA effectively attenuated tongue lesion severity. While all drug treatments limited the increase in the percentage of PCNA positive cells and the decrease in the percentage of p16 positive cells caused by the 4-NQO treatment in mouse tongue epithelial regions without visible lesions and in the neoplastic tongue lesions, the combination of 5-Aza and RA was the most effective. Collectively, our results show that the combination of a DNA demethylating drug and RA has potential as a strategy to reduce oral cavity cancer in this 4-NQO model.

Keywords: 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine, all-trans retinoic acid, cancer chemoprevention, squamous cell carcinoma, tongue lesions

INTRODUCTION

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is one of the most common cancers in the world (1). Even though the cure rate for small primary tumors is high, many patients will develop second primary tumors and the long-term survival rate for this cancer is less than 60% (1). Two major etiological factors in oral cavity SCC are the use of tobacco and alcohol, and malignant transformation of the oral cavity tissue is thought to be related to exposure to certain carcinogens (2). Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) development is a complicated, multi-step process that involves genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic changes (3). About 60–70% of oral cavity carcinoma cases are diagnosed only after the tumors have become locally advanced (4). Therefore, in addition to treatment, prevention (i.e. a reduction in the incidence of cancer and/or the inhibition of the development of malignant lesions) of oral cancer is a very important goal.

Compared to normal cells, human cancer cells exhibit epigenetic changes, defined as the alterations of gene expression via mechanisms other than the changes of the DNA sequences of these genes. These epigenetic changes include alterations in DNA methylation status and chromatin modifications. The alterations in DNA methylation include global hypomethylation of cytosines in intergenic regions of the genome, and hypermethylation of CpG islands (increases in cytosine methylation) in the promoter regions of some genes (5). These epigenetic changes, especially the hypermethylation of the gene promoter regions, occur very early during cancer development (6). The expression of some tumor suppressor genes is transcriptionally silenced by this DNA hypermethylation in their promoter regions, which is mediated by DNA methyltransferases (Dnmt) (5). De novo DNA methylation and transcriptional silencing mediated by overexpression of Dnmt3b promote mouse colon carcinogenesis in vivo (7). Conversely, the deletion of Dnmt3b greatly reduced mouse intestinal tumor formation (8). Studies have shown that Dnmt inhibitors 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine (5-Aza) and /or zebularine suppress the development of various cancers in mouse models, including intestinal carcinogenesis in Apc (Min/+) mice (9) and prostate cancer in TRAMP (Transgenic Adenocarcinoma of the Mouse Prostate) mice (10, 11). DNA hypermethylation of the promoters of genes that encode some cell cycle inhibitors and tumor suppressors, such as p16 and retinoic acid receptor β2 (RARβ2), is commonly seen in human oral squamous carcinoma cells (12). Therefore, DNA methyltransferases are targets for both cancer prevention and treatment (13, 14). The reversal of DNA hypermethylation by the drug 5-Azacytidine (5-AC), which inhibits DNA methyltransferases, has proven to be effective in the treatment of several human cancers, including head and neck cancer (12). However, whether the reversal of DNA hypermethylation has preventive effects on oral cavity carcinogenesis is not clear.

Retinoids, including vitamin A (retinol) and its derivatives such as all-trans retinoic acid (RA), regulate cell proliferation and differentiation (15). RA regulates gene expression by binding and activating retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs), which heterodimerize and associate with retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) in the genome (16). There are three RARs and three RXRs (α, β, and γ) and each subtype has various isoforms, and the binding of RA causes a conformational change in the RAR/RXR heterodimers that results in their dissociation from co-repressor complexes and their association with co-activators (17).

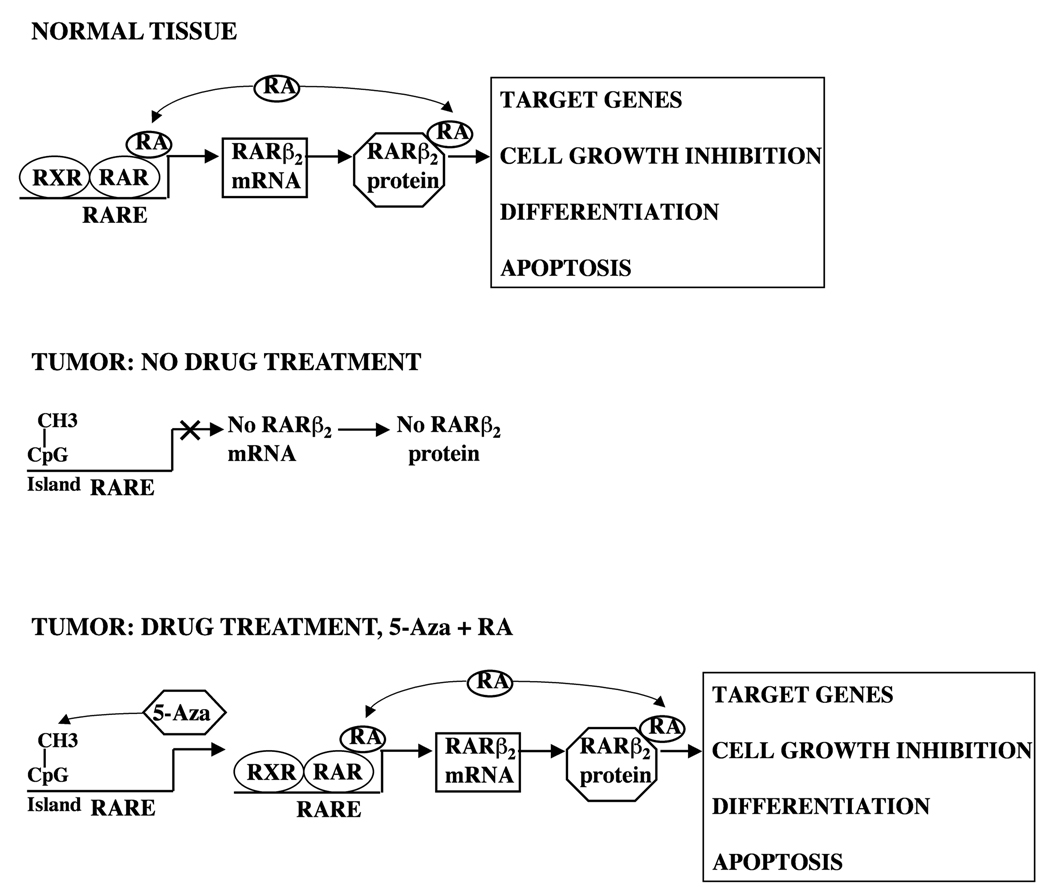

Epidemiological studies on human populations have demonstrated that a higher retinol intake in the diet is associated with the inhibition of the progression of carcinogenesis in lung, breast, cervix, prostate, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and oral cavity (18). Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that retinoids can be used as cancer chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agents in human cancers such as squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) (4, 15, 19, 20). In addition, Conway et al. showed that RA treatment suppressed the formation of cancer stem cells in primary tumors (21). The antitumor activities of RA are carried out predominantly through RARβ2, which acts as a tumor suppressor upon binding the agonist RA (17). In addition, RARβ2 gene transcription is activated through a RARE in its promoter region upon RA treatment (22). However, aberrant retinoid signaling, such as the reduction or the loss of the expression RARβ2, has been found in various human cancers, including human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells (17). The loss of RARβ2 expression during cancer development is often associated with retinoid resistance, and the mechanism of the loss of RARβ2 expression usually involves the hypermethylation of the RARβ2 gene promoter region (23). In addition, 5-Aza has proven to be able to restore the inducibility of RARβ2 expression by RA in human SCCHN cells in which the promoter region of RARβ2 is hypermethylated (24). Collectively, these data indicate the possibility of combining of RA and 5-Aza for the prevention of oral cavity carcinogenesis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The pharmacological rationale/ hypothesis for the combination of RA and 5-Aza treatment in the prevention of oral cavity carcinogenesis.

In normal tissue, the RARβ2 gene is transcriptionally activated by the endogenous agonist RA and the RARβ2 protein acts as a transcription factor in the presence of RA, leading to transcriptional activation of target genes, cell growth inhibition, differentiation, and normal apoptosis. In tumors, the RARβ2 promoter is often methylated, preventing the synthesis of RARβ2 mRNA and protein. Thus, RARβ2 does not function in these tumor cells. Only when both 5-Aza and pharmacological doses of RA are added to tumor cells are the transcriptional activation of the RARβ2 gene and the transcription factor activity of the RARβ2 protein restored.

Several animal models that mimic certain aspects of human oral cancer have been established, including hamster, rat, and mouse models (2, 25–27). Oral squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) induced in mice by the carcinogen 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO) added to the drinking water demonstrate similarities to human oral tumors in terms of their morphological, histopathological, and molecular characteristics (2, 28, 29). Therefore, this murine 4-NQO model is an excellent model to evaluate a variety of potential cancer preventive and therapeutic approaches. In this study we examined the cancer preventive effects of RA, 5-Aza, and the combination of RA and 5-Aza on oral cavity carcinogenesis by using this mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor development in the mouse oral cavity and drug treatments

Six week old wild type C57BL/6 female mice were used for this study. The experiments were carried out under controlled conditions with a 12 hour light/dark cycle. Animals were maintained on a normal chow (Lab-diet with constant nutrition, Lab-Diet Co, St. Louis, MO). The mice were treated with propylene glycol (vehicle as a negative control, n=5) or 100 µg/ml carcinogen 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide (4-NQO, Sigma, St Louis, MO), made up in vehicle, in the drinking water as previously described (2) for 10 weeks. Then the mice were allowed access to the regular drinking water.

Two weeks after termination of the carcinogen treatment mice received various drug treatments by intraperitoneal (IP) injection: PBS (n=10), 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine (5-Aza, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (n=10), all trans retinoic acid (RA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (n=10), 5-Aza+RA (n=10), and high dose RA (n=10). PBS (0.1 ml) was injected twice weekly; 5-Aza (250 µg/kg body weight) (10) was injected intraperitoneally twice weekly on consecutive days in 0.1 ml PBS; RA (LDRA, 100 µg/kg body weight) was injected twice weekly in 0.1 ml vegetable oil; high dose RA (HDRA, 1 mg/kg body weight) was injected once weekly in 0.1 ml vegetable oil. Mouse body weights and the precancerous and cancerous lesions were monitored in the oral cavities at different times for up to 15 weeks, or until signs of sickness or weight loss. Ten mice per group was chosen because, based on ANOVA analysis, this gives the minimum largest difference in means with 80% power at a 5% significance level in this study.

Measurement of serum retinoid levels

Prior to the sacrifice, mice in PBS (4-NQO/PBS), RA (4-NQO/LDRA), 5-Aza (4-NQO/5-Aza), the combination of RA and 5-Aza (4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA), and high RA (4-NQO/HDRA) treatment groups received the final drug injections. Ninety minutes later blood samples (approximately 100 µl each) from these mice were obtained via mouse tails. The analyses of retinoids in the mouse serum (from three mice per group) were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously reported (30, 31). Retinoids were identified by HPLC based on two criteria: an exact match of the retention times of unknown peaks with those of authentic retinoid standards, and identical ultraviolet light spectra (220–400 nm) of unknowns against spectra from authentic retinoid standards during HPLC by the use of a photodiode array detector (31). The levels of retinoids were normalized to the volume of the serum measured.

Tissue dissection, lesion grade measurement, and pathological diagnosis

The tongues of mice were dissected immediately after cervical dislocation. Gross lesions were identified and photographed, and visible cancerous lesions on the tongues were counted for the examination of multiplicity of these lesions (number of lesions per mouse) with a 10× magnification. The severity of gross lesions on the tongues was quantified by a grading system that included 0 (no lesion), 1 (mild lesion), 2 (intermediate lesion), 3 (severe lesion), and 4 (most severe lesion) in a double blinded manner, respectively, and the average grades from different treatment groups were used for the analyses of the tongue lesions. Mouse tongue lesions were cut in half longitudinally. Half of each tissue was fixed in freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5-µm sections. The other half of each tongue tissue was immediately placed in RNAlater solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at 4°C overnight before being moved to −20°C for long term storage. The histological diagnosis of squamous neoplasia (four representative mice per group based on the lesion grades) was performed by a pathologist (Dr. Theresa Scognamiglio) on the hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stained, sectioned tissue samples. The lesions observed were classified into three types: epithelial hyperplasia, dysplasia (mild, moderate, and severe), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), as described previously (2, 28).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin embedded sections (from four mice per group) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed. The tissue sections were stained by using the M.O.M. kit (for the p16 Ab) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), or the Envision™ + HRP (DAB+) kit (for the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) Ab) (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), or the Zymed Superpicture kit (for the Cox-2 Ab) (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA). After quenching endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2, the tissue sections were blocked with the blocking reagent (from the M.O.M. kit) or 1.5% goat serum. Then the tissue sections were incubated with mouse PCNA (1:100) antibody (Cat # M0879, mouse monoclonal Ab, Dako, Carpinteria, CA), p16 (1:200) antibody (Cat # sc-1661, mouse monoclonal Ab, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), or mouse Cox-2 antibody (1:100) (Cat# 160126, rabbit polycolonal Ab, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), respectively, for 60 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:200, anti-mouse IgG from the M.O.M kit for p16; ready to use anti-rabbit IgG from the Zymed SuperPicture kit for Cox-2; and ready to use anti-mouse IgG from the Dako Envision™ HRP (DAB+) kit for mouse PCNA). As a negative control, sections were stained without incubation with primary antibodies. Finally, signals were visualized based on a peroxidase detection mechanism, and 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Zymed SuperPicture kit) was used as the substrate. The cells with distinct nuclear staining were regarded as positive for PCNA and p16. Four to five representative areas of each mouse tongue section were photographed and analyzed. Percentages of PCNA and p16 positive cells (labeling indices) were determined by the number of these positive nuclei divided by the total epithelial cell nuclei in the areas.

Real time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from mouse tongues was extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA as described previously (28). Real-time PCR was performed using gene-specific oligonucleotide primers which generate cDNA fragments that cross an intron-exon boundary in the genomic DNA. Real-time PCR was performed on a MyiQ real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with an iQ SYBR Green Supermix. The conditions for the PCR were as follows: 95 °C for 3 min to activate the DNA polymerase, followed by 50 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 58°C for 30 s, and product extension at 72 °C for 30 s. After each cycle, fluorescence was read at 84 °C. 36B4 was used as a control (32). The primer sequences were as follows: mouse Cox-2 forward primer: 5'-TCAAAAGAAGTGCTGGAAAAGGTT-3', mouse Cox-2 reverse primer: 5'-TCTACCTGAGTG TCTTTGACTGTG-3'; mouse RARβ2 forward primer: 5’-GATCCTGGATTTCTACACCG-3’, mouse RARβ2 reverse primer: 5’-CACTGACGCCATAGTGGTA-3’; mouse c-Myc forward primer: 5’-TCCTCCCCACGGGCCAGCC-3’, mouse c-Myc reverse primer: 5’-GCA GGGGTTTGCCTCTTCT-3’; mouse 36B4 forward primer: 5’-AGAACAACCCAGCTCTGGAGAAA-3’, mouse 36B4 reverse primer: 5’-ACACCCTCCAGAAAGCGAGAGT-3’. We used the University of California, Santa Cruz In-Silico PCR program (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgPcr) to ensure that the PCR primers were not homologous to pseudogene sequences.

Statistical analysis of the data

The statistical analyses of the results were carried out using a one way ANOVA test followed by a Bonferroni's multiple comparison test, Fisher’s exact probability test, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for multiple comparisons. Differences with a p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Oral cavity carcinogenesis

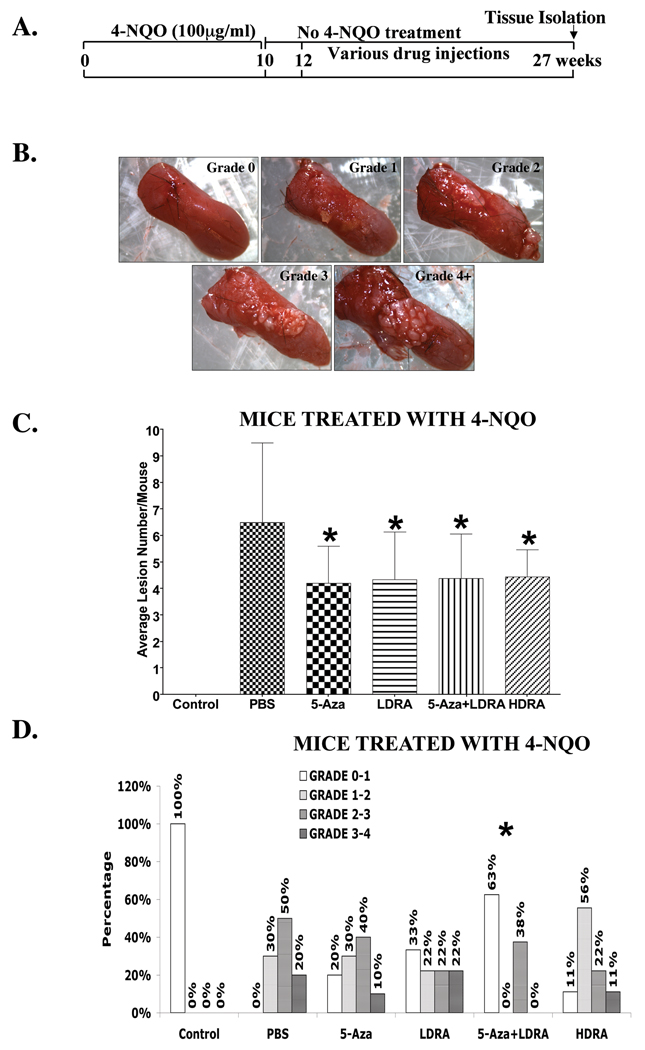

All of the mice survived the 10 week 4-NQO treatment, and more than 90% of the mice survived throughout the 15 week post-treatment period (Fig. 2A). Consistent with our previous studies (2, 28), we did not observe any gross lesions immediately after the end of the 10 week 4-NQO treatment. However, multifocal, precancerous and cancerous lesions (papillomas, squamous cell carcinomas) developed during the 15 week post-4-NQO treatment period, and these lesions were primarily seen on the dorsal side of the tongue (Fig. 2B). In contrast, no visible lesions (grade 0) were detected in the control mice not treated with 4-NQO (Fig. 2B, C, and D). The gross cancerous tongue lesion multiplicity (number of lesions per mouse) was examined. After the 4-NQO treatment mice that received PBS injections (4-NQO/PBS) developed multiple cancerous tongue lesions, and mice in all drug treatment groups (4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA) showed statistically significant decreases in the numbers of cancerous tongue lesions (Fig. 2C). Moreover, mice in the 4-NQO/PBS group developed severe tongue lesions; 70% of the tongues in this group showed lesions more severe than grade 2, and no mice developed tongue lesions of grade 0 and 1 (Fig. 2D, PBS). Both 5-Aza treatment alone (4-NQO/5-Aza) (p=0.71), and low dose RA treatment alone (4-NQO/LDRA) (p=0.26) showed trends of reduced incidence of the higher grade (grade 2–4) mouse tongue lesions such that the incidence of lower grade (grade 0–1) tongue lesions was higher as compared to the 4-NQO/PBS treated mice (Fig. 2D, compare 5-Aza alone or LDRA alone to PBS). This occurred because these 4-NQO/PBS treated mice primarily exhibited high grade lesions (Fig. 2D, PBS). High dose RA treatment (4-NQO/HDRA) resulted in a trend toward greater incidence of lower grade tongue lesions (grade 1–2 (56%)) and a lower incidence of higher grade 2–4 (33%) (p=0.46) tongue lesions (Fig. 2D, HDRA). Mice treated with the combination of 5-Aza and LDRA (4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA) also showed a greater incidence (63%) of less severe tongue lesions of grades 0 –1 (Fig. 2D, 5-Aza+LDRA). Statistical analyses with the Fisher’s exact probability test showed a statistically significant difference (p=0.01) in tongue lesion grades between the PBS group and the 5-Aza+LDRA combination group (Fig. 2D). In addition, we have previously observed precancerous and cancerous lesions in mouse esophagi at a much lower frequency (2). However, in this paper we focused on oral cavity carcinogenesis.

Figure 2. Average gross cancerous lesion numbers and lesion grades in mouse tongues from control mice (not treated with 4-NQO) and mice treated with the carcinogen 4-NQO followed by treatment with various drugs.

Wild type C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks old) were treated with propylene glycol (vehicle) or 4-NQO (100 µg/ml) in the drinking water for 10 weeks. Two weeks after the 4-NQO treatment was stopped, these 4-NQO treated mice were randomized (10 mice/group) to receive intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections with either 100 µl PBS or various drugs for another 15 weeks before being sacrificed. The dosages and frequencies of the drugs are described in the MATERIALS AND METHODS. The mice were then sacrificed, and the tongues were dissected out and photographed (10×). The grossly visible lesions on the whole tongues were graded in a double blinded manner. A, A brief diagram of the experimental protocol. B. Representative gross morphological observations of the mouse tongues and the gross tongue lesion grading system (10×). C. Average numbers of cancerous tongue lesions (multiplicity, i.e. number of lesions per mouse). A one way ANOVA test was used to analyze the differences in tongue lesion numbers among all treatment groups. Differences with a p value of < 0.05 (marked with an asterisk) between carcinogen treated and subsequently PBS treated mice (4-NQO/PBS) and mice in other treatment groups (4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA) were considered to be statistically significant. D. The percentages of mice in each group with different grade lesions, including the control mice (not treated with carcinogen and various drugs) and the mice treated with the carcinogen 4-NQO followed by treatment with various drugs. The differences among the distributions of lesions of different grades in each treatment group were analyzed by using a Fisher’s Exact probability test. Differences with a p value of < 0.05 between carcinogen treated and subsequently PBS treated mice (4-NQO/PBS) and mice in other treatment groups (4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA) were considered to be statistically significant, indicated by an asterisk.

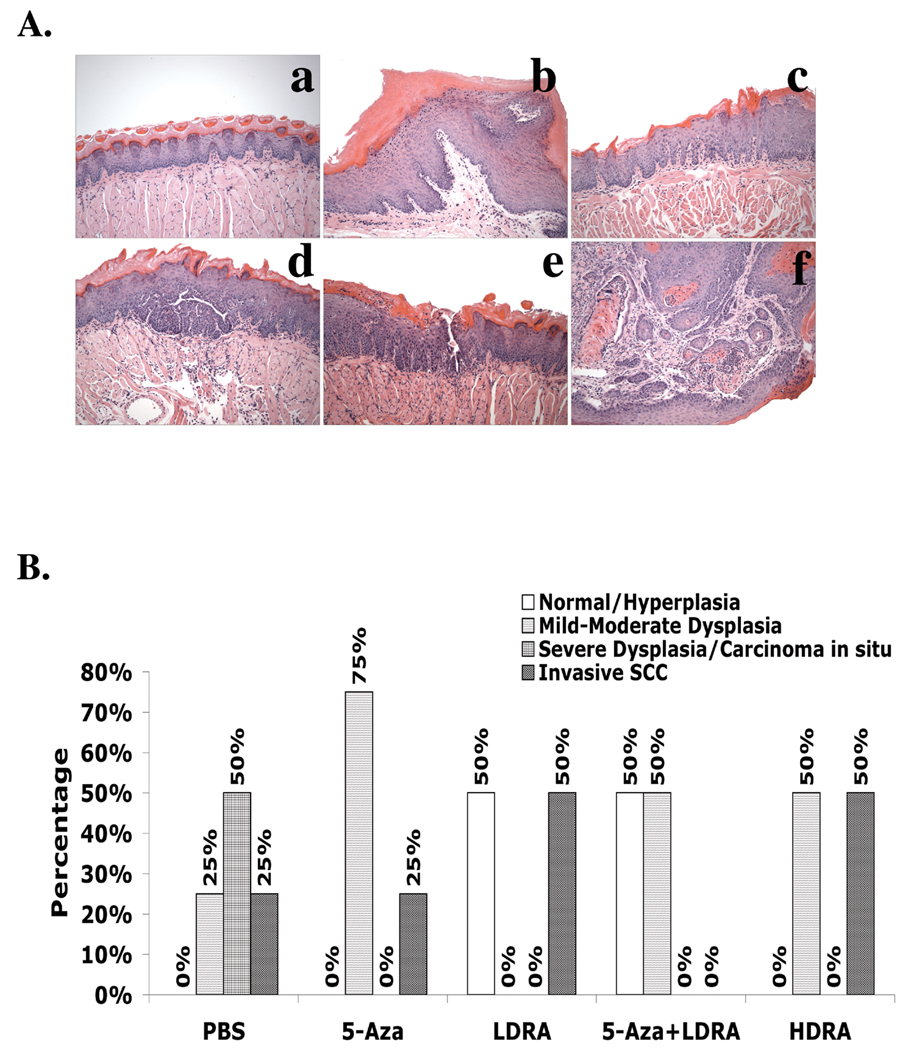

We also did pathological analyses on the tongue sections from 4-NQO treated mice. As shown in the representative pictures (Fig. 3A), the mouse tongue sections contained different stages of oral carcinogenesis, including hyperplasia, dysplasia (mild, moderate, and severe), and carcinoma (including carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma) with some samples containing multiple types of lesions. Clinical studies have shown that the dysplasias with high grades have a greater probability of developing into carcinomas than the lower grades of dysplasia (33). In this study we used a two-category system (normal / hyperplasia / mild or moderate dysplasia: low risk; severe dysplasia / carcinoma in situ / invasive SCC: high risk) to analyze the oral cancer risks of mice in the different treatment groups. In the 4-NQO/PBS group 75% of the mice showed severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma, which indicates a high risk of oral carcinogenesis. Compared to the 4-NQO/PBS group, the mice in the 4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA groups showed a lower incidence of high risk oral carcinogenesis, and more importantly, although not statistically significant, all of the mice in the combination 5-Aza and LDRA group (4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA) showed a trend toward a lower probability of oral carcinogenesis (p=0.07) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Pathological evidence of carcinogenesis in mouse tongues after carcinogen treatment.

Wild type C57BL/6 mice were treated with 4-NQO (100 µg/ml) in drinking water (see “Materials and Methods”) for 10 weeks and then maintained for another 15 weeks. The mice were sacrificed, and the tongues were fixed, embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. A, Representative pictures of pathology (200×). a, control tongue; b, hyperplasia with marked hyperkeratosis; c, mild dysplasia; d, moderate dysplasia; e, severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ; f, invasive carcinoma with tumor cells invading the skeletal muscle fibers of the tongue. B, Percentage of 4-NQO treated mouse tongue samples in each drug treatment group at different carcinogenesis stages. The data were analyzed by using a Fisher’s exact probability test. Differences with a p value of < 0.05 (marked with an asterisk) were considered to be statistically significant.

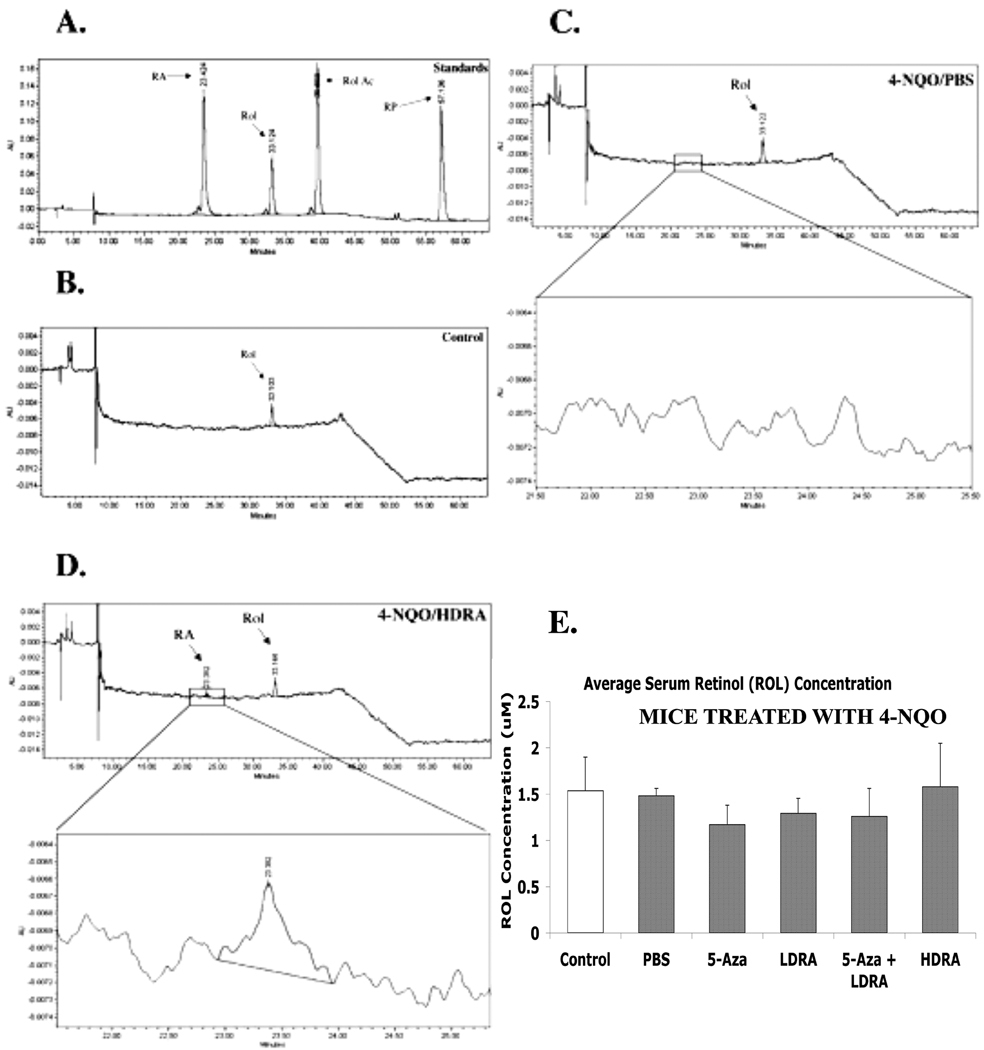

All trans retinol (ROL) and all trans retinoic acid (RA) in sera from mice in different treatment groups

In order to examine whether injected RA affected mouse serum retinoid levels, ninety minutes after the final drug injections mouse serum samples were collected and the serum retinoid levels were analyzed by HPLC (3 mice per group). In control mouse serum a retinol peak was detected at the retention time of 33 minutes (Fig. 4B). The sera from mice treated with 4-NQO and subsequently treated with PBS (4-NQO/PBS), 5-Aza (4-NQO/5-Aza), low dose RA (4-NQO/LDRA), the combination of 5-Aza and low dose RA (4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA), and high dose RA (4-NQO/HDRA), respectively, showed similar HPLC tracings (Fig. 4C, D, and data not shown). The serum retinol concentrations from these mice were not significantly different from those in the control mouse serum (Fig. 4E). Given the small volumes of sera (100 µl) collected, RA was detected only in the serum samples from the 4-NQO/HDRA group, and the serum RA concentration was 0.078 ± 0.012 µM, which is close to the detection limit of HPLC quantification of RA (Fig. 4D). We did not perform detailed pharmacokinetic studies on the drug RA given intraperitoneally. However, our data show that 90 min after an intraperitoneal injection, RA could be detected in the sera of HDRA mice, and the serum RA concentration was similar to the peak plasma RA level (0.07 ± 0.009 µM) which was detected between 60 and 180 min following a single oral administration of this drug (10 mg/kg body weight) in Balb/c nude mice (34).

Figure 4. All trans retinol (ROL) and all trans retinoic acid (RA) in sera from mice in different treatment groups.

Ninety minutes after the final drug injections, mouse serum samples were collected and the serum retinoid levels were analyzed by HPLC (3 mice per group) as described in the MATERIALS AND METHODS. The retention time of RA was 23.4 min. and ROL was eluted at 33.1 min. Rol Ac, retinyl acetate; RP, retinyl palmitate. A. HPLC tracing of retinoid standards. B. HPLC tracing of control mouse serum. C. HPLC tracing of serum from mice in 4-NQO/PBS group. D. HPLC tracing of serum from mice in 4-NQO/HDRA group. E. Serum retinol levels in mice from different treatment groups. The data were analyzed by using a one-way ANOVA test for multiple comparisons.

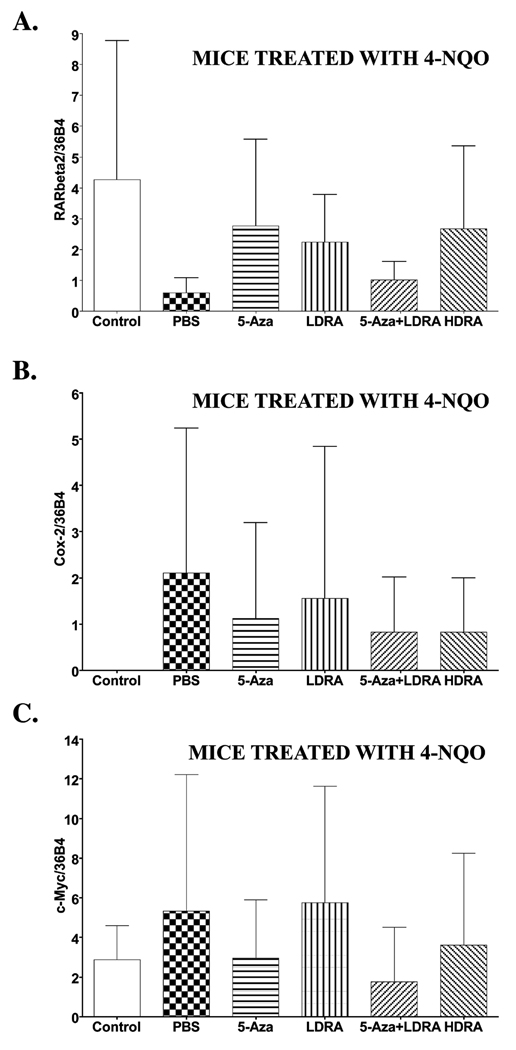

Effects of various drug treatments on RARβ2, Cox-2, and c-Myc mRNA levels in mouse tongues

Compared to normal epithelial tissues, RARβ2 mRNA levels are usually decreased or absent in head and neck squamous carcinomas, often because of the hypermethylation of the RARβ2 promoter (17, 35). The restoration of RARβ2 has been reported to suppress the proliferation of various cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (23). The antitumor activity of RARβ2 in human esophageal cancer cells correlates with the suppression of cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2) protein expression (36). Because 5-Aza has been shown to restore transcription of genes by reversing DNA hypermethylation at the promoter regions (24), we measured the RARβ2 mRNA levels by real time RT-PCR in the tongues of control (not 4-NQO treated) and 4-NQO treated mice that were subsequently treated with 5-Aza and/or other drugs in the post 4-NQO phase of the experiment. We observed high RARβ2 mRNA levels in all of our control mouse tongues (n=5), and 4-NQO treatment resulted in the significant and consistent reduction in RARβ2 mRNA levels in all tongues of mice that subsequently received PBS treatment (4-NQO/PBS) (n=10) (Fig. 5A). Among the mice that received the 4-NQO/5-Aza treatment (n=10), 60% of the tongues showed higher tongue RARβ2 mRNA levels than the highest RARβ2 mRNA level detected in the tongues of mice that received only PBS injections. In the 4-NQO/LDRA group (n=9), 56% of mice showed higher tongue RARβ2 mRNA levels than the highest RARβ2 mRNA level detected in the tongues of the PBS injection group. In the 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA group 38% of mouse tongues (n=8) showed higher RARβ2 mRNA levels than those detected in the tongues of 4-NQO/PBS treated mice. In the 4-NQO/HDRA group (n=9) 56% of mice showed higher tongue RARβ2 mRNA levels than the highest RARβ2 mRNA level detected in the tongues of 4-NQO/ PBS treated mice (Fig. 5A). However, the standard deviations were large in these assays, and we did not observe statistically significant differences in RARβ2 mRNA levels among the different drug treatment groups. The p-values ranged from 0.07 to 0.90.

Figure 5. RARβ2, Cox-2, and c-Myc mRNA levels in mouse tongues from control (not treated with 4-NQO) mice and mice treated with the carcinogen 4-NQO followed by treatment with various drugs.

Wild type C57Bl/6 mice were treated with propylene glycol (vehicle) or 4-NQO (100 µg/ml) in drinking water for 10 weeks and then treated with various drug injections for 15 weeks. The dosages and frequencies of the drugs are described in the MATERIALS AND METHODS. Total RNA was extracted from all mouse tongues from each treatment group and specific mRNA levels were measured by real time RT-PCR. A, RARβ2 mRNA (Average ± SD). B, Cox-2 mRNA (Average ± SD). C, c-Myc mRNA (Average ± SD). The data were analyzed by using a Wilcoxon rank sum test for multiple comparisons. Differences with a p value of < 0.05 (marked with an asterisk) between carcinogen treated and subsequently PBS treated mice (4-NQO/PBS) and mice in other groups (4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA) were considered to be statistically significant.

The cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2) expression level is elevated in oral cavity cancers (37). During oral cavity carcinogenesis Cox-2 expression increases during the malignant transition of the oral epithelium (4). Therefore, Cox-2 has been proposed as a promising molecular target for oral cancer prevention (4). We measured Cox-2 mRNA levels by real time PCR in tongues from control (not 4-NQO treated) and in tongues from mice treated with 4-NQO and subsequently treated with PBS or with various drugs. In control (not 4-NQO treated) (n=5) mouse tongues we did not detect Cox-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 5B). Carcinogen treatment resulted in Cox-2 mRNA expression in all of the mouse tongues from the 4-NQO/PBS treated group (n=10). The 4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA treated mouse tongues did not show statistically significant differences from the 4-NQO/PBS treated group in Cox-2 mRNA levels (Fig. 5B).

It has been reported that c-Myc transcripts are greatly overexpressed in advanced tumor stages of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (38). We also assessed c-Myc mRNA expression in these mouse tongues. c-Myc mRNA in control (not 4-NQO treated) mouse tongues (n=5) was detected and after 4-NQO treatment 30% of mouse tongues from the 4-NQO/PBS group showed greater c-Myc mRNA levels than the control group (Fig. 5C). Among all of the different drug treatments, only the tongues from the 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA group showed a trend (not statistically significant) of decreased c-Myc mRNA levels. In fact, these c-Myc levels were even lower than those in the control (not 4-NQO treated) group (Fig. 5C).

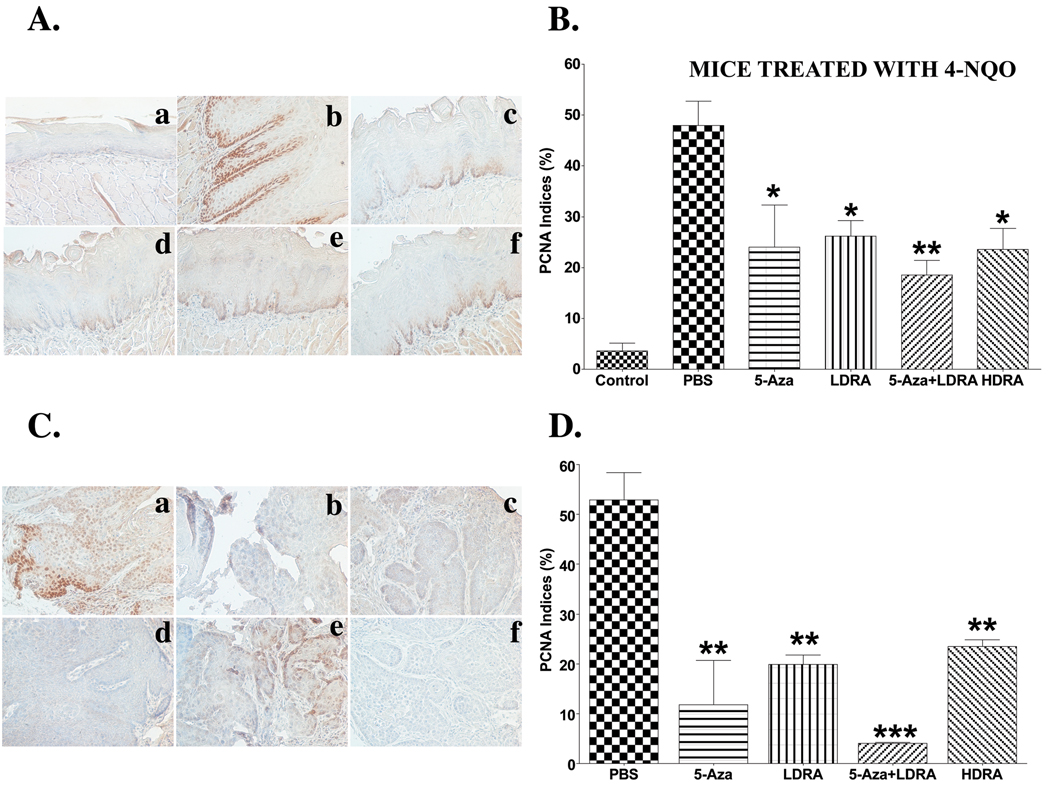

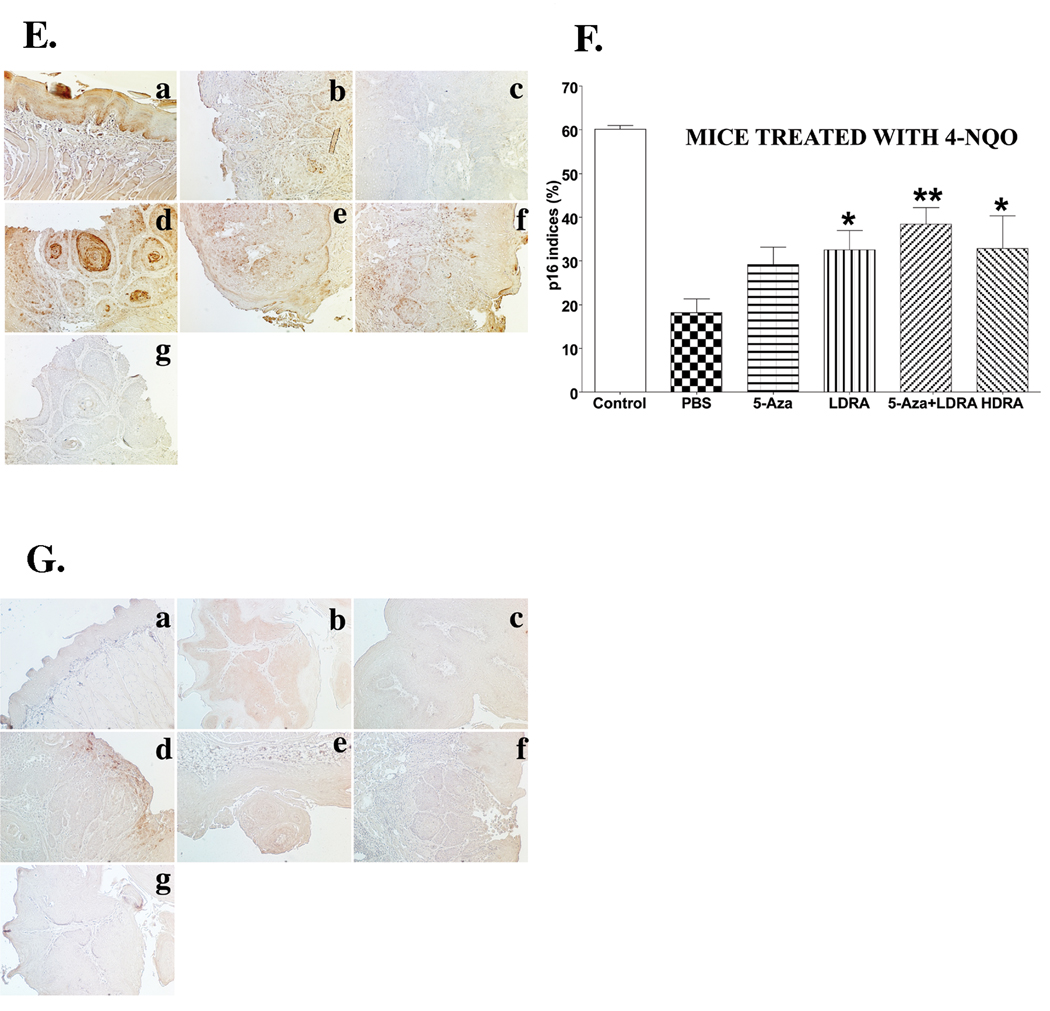

Effects of various drugs on PCNA, p16, and Cox-2 protein levels in mouse tongues

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a protein which is expressed in the cell nuclei during the S phase of the cell cycle, and this protein is needed for DNA polymerase delta to bind DNA (39). Therefore, PCNA is a marker of cell proliferation. We measured the PCNA protein levels in mouse tongues by immunostaining. Very few nuclei in the tongue epithelia from the control mice (not 4-NQO treated) showed PCNA positive cells, and 4-NQO treatment resulted in a large increase in the percentages of PCNA positive nuclei in both the mouse tongue epithelial regions without visible lesions and the regions with visible lesions (Fig. 6A and C, panels a and b). All drug treatments limited the increase in the percentages of PCNA positive cells in these tongue regions significantly, and the combination of 5-Aza and RA had the greatest effect in terms of reducing the percentage of PCNA positive cells (Fig. 6A, panels c–f, B; C, panels b–e, and D).

Figure 6. Expression of PCNA, p16, and Cox-2 proteins in mouse tongues from control (not treated with 4-NQO) mice and mice treated with the carcinogen 4-NQO followed by treatment with various drugs.

Wild type C57Bl/6 mice were treated with propylene glycol (vehicle) or 4-NQO (100 µg/ml) in drinking water for 10 weeks and then treated with various drug injections for 15 weeks. The dosages and frequencies of the drugs are described in the MATERIALS AND METHODS. Mice were sacrificed, and the tongues were fixed, embedded, sectioned, and stained with anti-PCNA, anti-p16, and anti-Cox-2 antibodies (four mice per group, 300×). Four to five representative areas of each mouse tongue section were photographed and analyzed. PCNA and p16 indices were determined by the number of these positive nuclei divided by the total epithelial cell nuclei in the areas. A, PCNA staining in mouse tongue regions without visible lesions (300×). a, tongue section from control mice; b, tongue section from 4-NQO/PBS treated mice; c, tongue section from 4-NQO/5-Aza treated mice; d, tongue section from 4-NQO/LDRA treated mice; e, tongue section from 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA treated mice; g, tongue section from 4-NQO/HDRA treated mice. B, The quantitation of PCNA indices in panel A. C, PCNA staining in mouse tongue regions with visible lesions (300×). a, tongue section from 4-NQO/PBS treated mice; b, tongue section from 4-NQO/5-Aza treated mice; c, tongue section from 4-NQO/LDRA treated mice; d, tongue section from 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA treated mice; e, tongue section from 4-NQO/HDRA treated mice; f, negative control, a mouse tongue section stained only with a secondary antibody. D. The quantitation of PCNA indices in panel C. E, p16 staining of mouse tongues (200×). F, The quantification of p16 indices in panel E. G, Cox-2 staining of mouse tongues (200×). a, tongue section from control mice; b, tongue section from 4-NQO/PBS treated mice; c, tongue section from 4-NQO/5-Aza treated mice; d, tongue section from 4-NQO/LDRA treated mice; e, tongue section from 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA treated mice; f, tongue section from 4-NQO/HDRA treated mice; g, negative control, a mouse tongue section stained only with a secondary antibody. The data were analyzed by using a one-way ANOVA test for multiple comparisons. Differences with a p value of < 0.05 (marked with asterisks, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001) between carcinogen treated, and subsequently PBS treated mice and mice in other groups (4-NQO/5-Aza, 4-NQO/LDRA, 4-NQO/5-Aza+LDRA, and 4-NQO/HDRA) were considered to be statistically significant.

During the process of carcinogenesis, dysregulation of the cell cycle is a critical event (40). The loss of expression of p16 protein, one of the cell cycle inhibitors, has been observed in oral premalignant lesions and primary tumors of the oral cavity (41). Therefore, we examined the effects of different drug treatments on p16 protein expression in the mouse tongues. In control mouse tongues (not 4-NQO treated) p16 nuclear staining was observed in the epithelial basal and suprabasal layers, but primarily in the basal layer (Fig. 6E, panel a). The carcinogen 4-NQO treatment caused a large reduction in p16 nuclear staining in the tongue lesions of the PBS treatment group (Fig. 6E, panel b). After 4-NQO treatment, 5-Aza treatment alone did not prevent the decrease in the percentage of p16 positive nuclei in the tongue lesions (Fig. 6E panel c); However, treatments with low dose RA, the combination of 5-Aza and low dose RA, and high dose RA limited the decrease in p16 nuclear staining in the tongue lesions (Fig. 6E, panels d–f, F).

Finally, we investigated Cox-2 protein expression in the mouse tongues. In control (not 4-NQO treated) mouse tongue epithelia we did not observe Cox-2 staining, and 4-NQO treatment caused a major increase in Cox-2 protein staining in the tongue lesions of the 4-NQO/PBS treatment group (Fig. 7C, panels a and b). After 4-NQO treatment, all drug treatments partially reduced the increase in Cox-2 protein levels in mouse tongue lesions (Fig. 6G, panels c–f).

Discussion

Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes by the hypermethylation of their promoter regions plays an important role in many human cancers (12). Inhibition of Dnmt activities has been reported to be effective in the treatment of some human cancers, including human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (12). In this study we show that the combination of a DNA demethylating drug (5-Aza) and RA effectively attenuates oral cavity tumorigenic progression in a mouse model of human oral cavity cancer (Fig. 2C, D, and Fig. 3B).

Oral cavity tumor prevention in a mouse model

5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine (5-Aza) reduced the development of prostate cancer in TRAMP mice (a prostate cancer mouse model) and delayed the progression of preexisting prostate cancer to more advanced stages (10, 11). 5-Aza also restored p16 mRNA expression in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells that had reduced p16 expression and restored the inducibility of RARβ2 by RA in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells (24, 42). Retinoids, especially all-trans retinoic acid (RA), while regarded as candidates for cancer chemoprevention and chemotherapy, are not effective over the long term when given orally as a single drug in oral cavity cancer prevention clinical trials (17, 43). The combination of 5-Aza and RA inhibits the proliferation of human cancer cells, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells (24, 44). Our data suggest that the combination of 5-Aza and RA has potential for cancer prevention and treatment (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Consistent with these previous studies, we found that although 5-Aza or RA (low and high doses) treatment alone reduced the multiplicity of mouse tongue lesions induced by 4-NQO (Fig. 2C), either drug alone did not reduce the severity of these lesions (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the combination of 5-Aza and LDRA reduced both the multiplicity and the severity of tongue lesions induced by 4-NQO (Fig. 2C, D) and potentially reduced the probability of oral carcinogenesis (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the combination of 5-Aza and RA limited the 4-NQO induced increase in the percentage of PCNA positive cells and the decrease in the percentage of p16 positive cells in mouse tongues (Figs. 6A–D; 6E, F). Our findings indicate that the combination of 5-Aza and LDRA is an effective drug combination for the reduction of oral cancer in this murine 4-NQO model. However, although the combination of the drugs 5-Aza and LDRA significantly reduced the severity of tongue lesions, this treatment did not completely block the formation of the lesions (Fig. 2C, D; Fig. 3B). Moreover, the combination of 5-Aza and LDRA did not reduce PCNA and increase p16 labeling indices, respectively, to levels similar to those in the control (not 4-NQO treated) mouse tongue epithelia. Our results show that the combination of 5-Aza and LDRA does not totally prevent the hyperproliferation of tongue epithelial cells and the formation of initial tongue lesions. In addition, our results show that further investigation of different doses of these drugs for the prevention of oral cancer would be important.

We also observed that mice treated with LDRA and HDRA after 4-NQO showed a smaller decrease in p16 nuclear staining in the tongue lesions as compared to mice given PBS after 4-NQO (Fig, 6E and F). During oral cavity carcinogenesis methylation of the p16 gene promoter does not occur in all mouse tongue epithelial cells (42). It has also been reported that RARα can induce p16 protein expression in neoplastic epidermal keratinocytes (45). Therefore, RA treatment could activate p16 transcription in some cells in which this gene promoter is not methylated.

Effects of drug treatments on RARβ2 mRNA, Cox-2, and c-Myc expression in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells and the mouse tongue lesions

The silencing of RARβ2 expression by the hypermethylation of its promoter at the early stages of head and neck cancer development has been associated with retinoid resistance (17, 23). Previous studies have shown that 5-Aza treatment inhibited the proliferation of human SCCHN cells, induced RARβ2 mRNA expression, and restored the inducibility of RARβ2 by RA in these cells (24). In addition, the combination of 5-Aza and a HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA), improved the induction of RARβ2 mRNA expression by RA in human breast cancer cells and head and neck cancer cells (46, 47). We found that after 4-NQO treatment all drug treatments limited the reduction in RARβ2 mRNA in mouse tongues as compared to the PBS group (Fig. 5A).

Cox-2 has been considered to be a cancer chemopreventive target for human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (4). We show here that Cox-2 mRNA is not detected in the control (not 4-NQO treated) mouse tongues and that 4-NQO treatment increases Cox-2 mRNA levels (Fig. 5B), data that are consistent with previous studies (48). Mestre et al. (1997) (49) reported that RA inhibited Cox-2 mRNA and protein expression in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. However, we did not observe statistically significant differences in Cox-2 mRNA levels in the mouse tongues between the drug treatment groups and the PBS group (Fig. 5B). In addition, our results show a trend that all drug treatments limited the increase in Cox-2 protein levels in mouse tongue lesions induced by 4-NQO (Fig. 6G), consistent with the previous reports (49).

It has been reported that the RA alone and the combination of 5-Aza and RA could suppress c-Myc mRNA expression in HL-60 myeloid leukemic cells (50). Similar to their findings, our data showed a trend that the combination of 5-Aza + LDRA decreased c-Myc mRNA levels in 4-NQO treated mouse tongues (Fig. 5C). Taken together, our data suggest that a DNA demethylating drug could be useful for the prevention of oral cavity cancer, and that the combination of a DNA demethylating drug and RA is a potentially useful approach for the prevention of oral cavity cancer in high risk individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Kathy Zhou, a biostatistician in the Department of Public Health of Weill Cornell Medical College, for advice on the statistical analyses; the insightful scientific input provided by the members of the Gudas laboratory; and Christopher Kelly for editorial assistance. This research was supported primarily by NIH grant R01 DE10389 to LJG. Support for XHT was from the training grant NCI 5T32 CA062948 for a portion of this project.

Abbreviations

- 5-Aza

5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine

- RA

all-trans retinoic acid

- Cox

cyclooxygenase

- DAB, 3

3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride

- Dnmt

DNA methyltransferase

- HDRA

high dose RA

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- LDRA

low dose RA

- 4-NQO

4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- RARE

retinoic acid response element

- ROH

retinol

- Rol Ac

retinyl acetate

- RP

retinyl palmitate

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- SCCHN

squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang XH, Knudsen B, Bemis D, Tickoo S, Gudas LJ. Oral cavity and esophageal carcinogenesis modeled in carcinogen-treated mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:301–313. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0999-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddad RI, Shin DM. Recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1143–1154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lippman SM, Sudbo J, Hong WK. Oral cancer prevention and the evolution of molecular-targeted drug development. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:346–356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan TL, Yuen ST, Kong CK, et al. Heritable germline epimutation of MSH2 in a family with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1178–1183. doi: 10.1038/ng1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linhart HG, Lin H, Yamada Y, et al. Dnmt3b promotes tumorigenesis in vivo by gene-specific de novo methylation and transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3110–3122. doi: 10.1101/gad.1594007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin H, Yamada Y, Nguyen S, et al. Suppression of intestinal neoplasia by deletion of Dnmt3b. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2976–2983. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.2976-2983.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo CB, Chuang JC, Byun HM, et al. Long-term epigenetic therapy with oral zebularine has minimal side effects and prevents intestinal tumors in mice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:233–240. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-07-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe MT, Low JA, Daignault S, Imperiale MJ, Wojno KJ, Day ML. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase activity prevents tumorigenesis in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:385–392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorn CS, Wojno KJ, McCabe MT, Kuefer R, Gschwend JE, Day ML. 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine delays androgen-independent disease and improves survival in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate mouse model of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2136–2143. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw R. The epigenetics of oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issa JP. DNA methylation as a therapeutic target in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1634–1637. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issa JP. Cancer prevention: epigenetics steps up to the plate. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:219–222. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gudas LJ, Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Cell biology and biochemistry of the retinoids. In: Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 443–520. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10:940–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mongan NP, Gudas LJ. Diverse actions of retinoid receptors in cancer prevention and treatment. Differentiation. 2007;75:853–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke N, Germain P, Altucci L, Gronemeyer H. Retinoids: potential in cancer prevention and therapy. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2004;6:1–23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399404008488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong WK, Itri LM. Retinoids and human cancer. In: Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. Second ed. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 597–630. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeder CP, Kadara H, Lotan D, et al. Involvement of mitochondrial and Akt signaling pathways in augmented apoptosis induced by a combination of low doses of celecoxib and N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide in premalignant human bronchial epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9762–9770. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conway AE, Lindgren A, Galic Z, et al. A self-renewal program controls the expansion of genetically unstable cancer stem cells in pluripotent stem cell-derived tumors. Stem Cells. 2009;27:18–28. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Thé H, Vivanco-Ruiz M, Tiollais P, Stunnenberg H, Dejean A. Identification of a retinoic acid responsive element in the retinoic acid receptor β gene. Nature. 1990;343:177–180. doi: 10.1038/343177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu XC. Tumor-suppressive activity of retinoic acid receptor-beta in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2007;253:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youssef EM, Lotan D, Issa JP, et al. Hypermethylation of the retinoic acid receptor-beta(2) gene in head and neck carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1733–1742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gimenez-Conti IB, Slaga TJ. The hamster cheek pouch carcinogenesis model. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1993;17F:83–90. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240531012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki R, Kohno H, Suzui M, et al. An animal model for the rapid induction of tongue neoplasms in human c-Ha-ras proto-oncogene transgenic rats by 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide: its potential use for preclinical chemoprevention studies. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:619–630. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raimondi AR, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS. Rapamycin prevents early onset of tumorigenesis in an oral-specific K-ras and p53 two-hit carcinogenesis model. Cancer Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4645. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang XH, Su D, Albert M, Scognamiglio T, Gudas LJ. Overexpression of lecithin:retinol acyltransferase in the epithelial basal layer makes mice more sensitive to oral cavity carcinogenesis induced by a carcinogen. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2009 doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.13.8630. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vitale-Cross L, Czerninski R, Amornphimoltham P, Patel V, Molinolo AA, Gutkind JS. Chemical carcinogenesis models for evaluating molecular-targeted prevention and treatment of oral cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009;2:419–422. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L, Gudas LJ. Disruption of the lecithin:retinol acyltransferase gene makes mice more susceptible to vitamin a deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40226–40234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang XH, Suh MJ, Li R, Gudas LJ. Cell proliferation inhibition and alterations in retinol esterification induced by phytanic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:165–176. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600419-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillespie RF, Gudas LJ. Retinoic Acid receptor isotype specificity in f9 teratocarcinoma stem cells results from the differential recruitment of coregulators to retinoic Acid response elements. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33421–33434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warnakulasuriya S, Reibel J, Bouquot J, Dabelsteen E. Oral epithelial dysplasia classification systems: predictive value, utility, weaknesses and scope for improvement. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:127–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achkar CC, Bentel JM, Boylan JF, Scher HI, Gudas LJ, Miller WH., Jr Differences in the pharmacokinetic properties of orally administered all-trans-retinoic acid and 9-cis-retinoic acid in the plasma of nude mice. Drug Metab Disp. 1994;22:451–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu L, Crowe DL, Rheinwald JG, Chambon P, Gudas LJ. Abnormal expression of retinoic acid receptors and keratin 19 by human oral and epidermal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3972–3981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song S, Guan B, Men T, Hoque A, Lotan R, Xu XC. Antitumor effect of retinoic acid receptor-beta2 associated with suppression of cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009;2:274–280. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan G, Boyle JO, Yang EK, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is up-regulated in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1999;59:991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen DC, Parsa B, Close A, Magnusson B, Crowe DL, Sinha UK. Overexpression of cell cycle regulatory proteins correlates with advanced tumor stage in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:1285–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moldovan GL, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell. 2007;129:665–679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherr CJ. Principles of Tumor Suppression. Cell. 2004;116:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter KD, Thurlow JK, Fleming J, et al. Divergent routes to oral cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7405–7413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yakushiji T, Uzawa K, Shibahara T, Noma H, Tanzawa H. Over-expression of DNA methyltransferases and CDKN2A gene methylation status in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khuri FR, Lee JJ, Lippman SM, et al. Randomized phase III trial of low-dose isotretinoin for prevention of second primary tumors in stage I and II head and neck cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:441–450. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mongan NP, Gudas LJ. Valproic acid, in combination with all-trans retinoic acid and 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine, restores expression of silenced RARbeta2 in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:477–486. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatoum A, El-Sabban ME, Khoury J, Yuspa SH, Darwiche N. Overexpression of retinoic acid receptors alpha and gamma into neoplastic epidermal cells causes retinoic acid-induced growth arrest and apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1955–1963. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sirchia SM, Ferguson AT, Sironi E, et al. Evidence of epigenetic changes affecting the chromatin state of the retinoic acid receptor β2 promoter in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:1556–1563. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whang YM, Choi EJ, Seo JH, Kim JS, Yoo YD, Kim YH. Hyperacetylation enhances the growth-inhibitory effect of all-trans retinoic acid by the restoration of retinoic acid receptor beta expression in head and neck squamous carcinoma (HNSCC) cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56:543–555. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Z, Zhang X, Li M, et al. Simultaneously targeting epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase and cyclooxygenase-2, an efficient approach to inhibition of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5930–5939. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mestre JR, Subbaramaiah K, Sacks PG, et al. Retinoids suppress epidermal growth factor-induced transcription of cyclooxygenase-2 in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2890–2895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khanduja KL, Kumar S, Varma N, Varma SC, Avti PK, Pathak CM. Enhancement in alpha-tocopherol succinate-induced apoptosis by all-trans-retinoic acid in primary leukemic cells: role of antioxidant defense, Bax and c-myc. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;319:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]