Abstract

Interferon β (IFNβ) is an approved therapeutic option for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS). The molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of IFNβ in MS are not fully understood. Migration of dendritic cells (DC) from the inflammatory site to draining lymph nodes for antigen presentation and activation of naïve T cells, and to the CNS for reactivation of encephalitogenic T cells, requires CCR7 and MMP-9 expression. Here we report for the first time that IFNβ inhibits CCR7 expression and MMP-9 production in mature DC, and reduces their migratory capacity. The effect of IFNβ is mediated through STAT-1. In vivo treatment with IFNβ results in lower numbers of DC migrating to the draining lymph node following exposure to FITC, and in reduced expression of CCR7 and MMP-9 in splenic CD11c+ DC following LPS administration. IFNβ and IFNγ share the same properties in terms of effects on CCR7, MMP-9 and DC migration, but have opposite effects on IL-12 production. In addition, IFNβ-treated DC have a significantly reduced capacity for activating CD4+ T cells and generating IFNγ-producing Th1 cells. The suppression of mature DC migration through negative regulation of CCR7 and MMP-9 expression represents a novel mechanism for the therapeutic effect of IFNβ.

Keywords: Dendritic cell migration, IFNβ, STAT-1, CCR7, MMP-9

INTRODUCTION

Following antigen uptake, peripheral dendritic cells (DC) migrate to draining lymph nodes where they orchestrate the adaptive immune response through activation of T cells. DC migration is essential in positioning them at inflammatory sites and subsequently at sites of interaction with cognate T cells. DC traffic from peripheral tissues to lymph nodes requires mobilization signals provided primarily by proinflammatory cytokines, upregulation of the matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and −9 for proteolysis of the extracellular matrix, and expression of CCR7 for directional migration in response to lymph node-derived CCL19/21 [reviewed in (1)]. Less is known about factors and mechanisms involved in the negative regulation of DC trafficking. This is particularly relevant to pathological conditions where DC accumulate in high numbers at inflammatory sites, reactivating pathogenic T cells. For example, DC secreting proinflammatory cytokines accumulate in the synovium of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, promoting Th1 and Th17 differentiation (2). In multiple sclerosis (MS) there is intracerebral recruitment of DC with subsequent localization in the MS lesions (3, 4). In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), peripheral myeloid DC recruited into the CNS perivascular space reactivate myelin-specific CD4+ T cells (5, 6).

Recombinant interferon beta (IFNβ) is a therapeutic agent in remitting-relapsing MS [reviewed in (7)]. The molecular mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effect of IFNβ in MS are not fully understood. In the present study, we examined the role of IFNβ on the migration of bone marrow-derived DC matured in the presence of a proinflammatory cytokine cocktail containing TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2. To our knowledge, this is the first report indicating that IFNβ inhibits CCR7 and MMP-9 upregulation in cytokine-matured DC and prevents in vitro and in vivo DC migration. This study identifies IFNβ as a factor controlling the migration of inflammatory DC through STAT-1 mediated effects on CCR7 and MMP-9.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and reagents

B10.A and BALB/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). STAT-1-deficient mice (129S6/SvEv-Stat1tm1Rds) and corresponding wild-type mice (129S6/SvEv) were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). TCR-Cyt-5CC7-I/Rag1−/− transgenic (PCCF-specific TCR Tg; I-Ek) mice (Taconic Farms) were bred and maintained in the Temple University School of Medicine animal facilities under pathogen-free conditions. The reagents were purchased as follows: GM-CSF, CCL19, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 from PeproTech Inc (Rocky Hill, NJ); LPS (Escherichia coli O55:B5), Poly I:C, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); MMP-9 inhibitor I, from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA); IFNα, IFNβ, and anti-IFNβ neutralizing Abs from PBL Interferon Source (Piscataway, NJ); IFNγ from R&D systems (Mineapolis, MN); FITC-conjugated anti-MHCII, FITC-conjugated anti-CD80, FITC-conjugated anti-CD86, FITC-conjugated anti-CD40, and PE-conjugated anti-CD11c from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA); PE-anti-mouse CCR7 from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Generation and purification of bone marrow-derived DC

DC were generated from murine bone marrow as previously described (8, 9), and CD11c+ DC were purified by immunomagnetic sorting with anti-CD11c-coated magnetic beads using the autoMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec Auburn, CA) (>95% CD11c+ by FACS analysis). Splenic CD11c+ cells were enriched from spleen cell suspensions by immunomagnetic separation (see above) (50–60% CD11c+ cells by FACS analysis; the major contaminants were CD4+T cells − 30–40%). Splenic CD4+ T cells were purified by immunomagnetic sorting with anti-CD4-coated magnetic beads (>97% CD4+ by FACS analysis).

FACS Analysis

Cells were subjected to FACS analysis in a 4-color FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Data were collected for 10,000 cells and analyzed using Cellquest software from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). DC were treated with IFNβ or TNF-α+IL-1β+IL-6 in the presence or absence of IFNβ for 24h. Cells were incubated with CD40, CD80, CD86, MHCII, or CCR7 Abs at 4°C for 30 min following FACS analysis.

Real Time RT-PCR

Expression of CCR7, MMP-9 and IL-12 was detected by real time RT-PCR as previously described (9). The primers are: CCR7 sense 5’-TTCCAGCTGCCCTA CAATGG-3’ and antisense 5’-GAAGTTGGCCACCGTCTGAG-3’; MMP-9 sense 5’-AAAACCTCCAACCTCACGGA-3’ and antisense 5’-GCGGTACAAGTATGC CTCTGC-3’; p35 sense 5’-GAGGACTTGAAGATGTACAG-3’ and antisense 5’-TTCTATCTGTGTGAGGAGGGC-3’; p40 sense 5’-GACCCTGCCGATTGAAC TGGC-3’ and antisense 5’-CAACGTTGCATCCTAGGATCG-3’.

Matrix metalloproteinase protein assay

Secreted pro-MMP-9 was measured with the Mouse Pro-MMP-9 Quantikine Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Chemotaxis Assay and Matrigel Migration Assay

Purified DC were assayed for chemotactic and Matrigel migration to CCL19 (100ng/ml) as previously described (9).

In vivo DC migration assay

Mice (BALB/c,males, 6–8 wks old) were injected i.p. with PBS (400µl) (control) or IFNβ (10,000 IU) 12h and 1h before the application of the contact sensitizer FITC (100µl of 10mg/ml FITC dissolved in a 50:50 (vol/vol) acetone/dibutylphthalate) as previously described (10). 12h after FITC application mice received the last treatment with IFNβ (10,000 IU), and 12h later cell suspensions were prepared from draining inguinal lymph nodes. DC were stained with PE anti-mouse CD11c and FITC/PE double-positive cells were detected by FACS.

For the transfer experiments, BM-DC were treated with TNF-α+IL-1β+IL-6+PGE2 with or without IFNβ for 48h and labeled with PKH 26 red fluorescent dye (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1×106 labeled DCs were inoculated s.c in the footpads of mice preinjected 24h earlier with 40ng TNF-α (s.c in the footpads). 48h later the numbers of labeled DCs collected from the draining popliteal lymph nodes were determined by FACS.

Endocytosis

Endocytosis was measured as the cellular uptake of FITC-dextran (Sigma-Aldrich) and was quantified by flow cytometry. Briefly, DC (5×105 cells/well) were incubated in medium containing FITC-dextran (0.5 mg/ml; molecular mass 40 kDa) for 2h at 37°C. As a negative control, DC were precooled to 4°C prior to incubation with FITC-dextran at 4°C for 2h. Subsequently, the cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS and analyzed by FACS.

Apoptosis Assay

DC were collected, washed and analyzed immediately by flow cytometry by using the FITC Annexin V / PI apoptosis assay (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).

In vivo treatment

BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with IFNβ (10,000IU in 400µl PBS) 12h and 1h before and 12h after i.p. administration of LPS (100µg in 400µl PBS). Control animals were injected with the same volume of PBS. 24h after LPS inoculation splenic enriched CD11c+ cell populations and purified CD4+ cells were obtained and subjected to real time RT-PCR for CCR7 and MMP-9 mRNA expression.

T cell proliferation assay

T cell proliferation was measured in triplicate cultures in flat-bottom 96 well microtiter plates. DC (1×104 cells/well) cultured in the presence or absence of IFNβ were treated with LPS for 24h and pulsed with PCCF (5µM) or proteolipid protein (PLP; nonspecific Ag, 20µg/ml) for 2h. After extensive washing, DC were cocultured with PCCF-specific Tg CD4+T cells (1×105 cells/well). Negative controls consisted of DC or T cells alone. On day 3 of coculture, 3H-thymidine (1µCi per well) was added and incorporation was measured after 16h.

Cytokine ELISA

Cytokine production was determined by sandwich ELISA. Supernatants were harvested and subjected to ELISA. The detection limit for IL-12p70 and IFNγ was 30pg/ml.

Statistical Analysis

Results are given as mean +/− SE. Comparisons between two groups were done using the Student’s t-test, whereas comparisons between multiple groups were done by ANOVA. Statistical significance was determined as P values less than 0.05.

RESULTS

IFNβ inhibits CCR7 expression in cytokine matured DC

CCR7, the receptor for CCL19/21, is induced upon DC maturation through TLR or proinflammatory cytokine signaling (11–13), and its role in DC migration has been revealed in CCR7-deficient mice (14, 15).

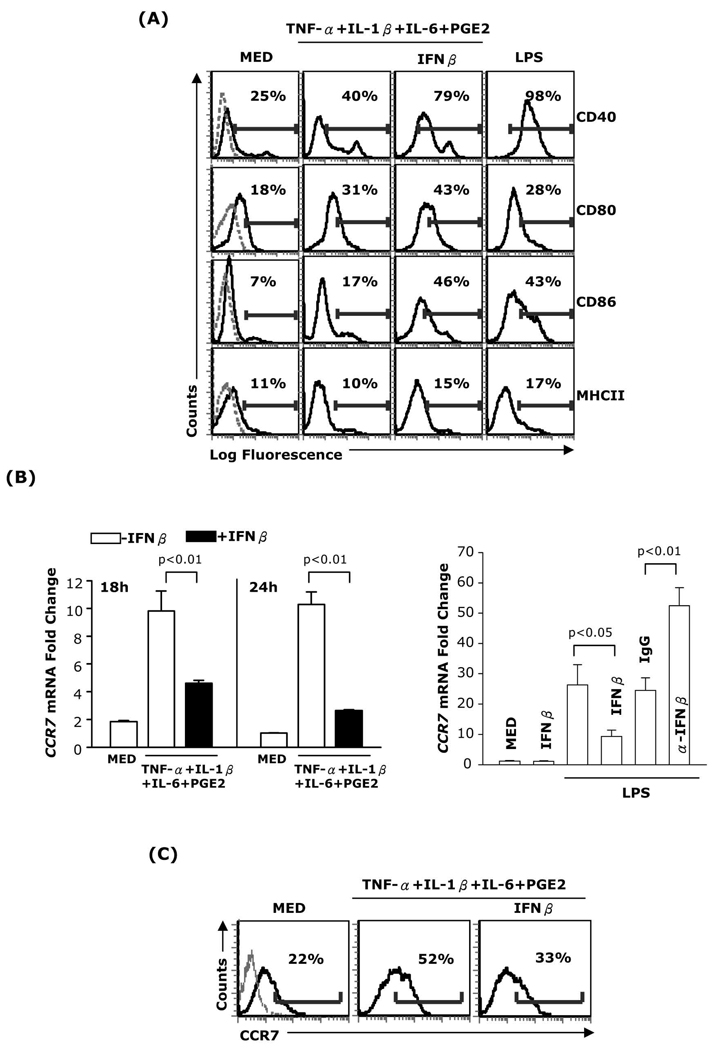

We investigated the effect of IFNβ on CCR7 expression in purified CD11c+ bone marrow-derived DC matured with a cytokine cocktail consisting of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and PGE2. In contrast to the increased expression of CD40, CD80 and CD86 in IFNβ treated DC (Fig. 1A), CCR7 expression was significantly reduced (Fig. 1B-left panel and 1C). A similar reduction in CCR7 expression was observed in DC matured with TNF-α+IFNα+PGE2 or Poly I:C+PGE2 (Supplemental Fig. 1A–B). These results indicate that IFNβ selectively inhibits CCR7 expression in DC matured with different stimuli. To assess the role of endogenous IFNβ, we matured DC with LPS, which induces IFNβ release, and determined the levels of CCR7 expression. CCR7 expression was enhanced in the presence of neutralizing anti-IFNβ Abs (Fig. 1B-right panel), indicating that, similar to exogenous IFNβ, endogenous IFNβ inhibits the upregulation of CCR7 expression during DC maturation.

Fig. 1. Effects of IFNβ on DC maturation markers and CCR7 expression.

(A) DC were treated for 24h with TNF-α (20ng/ml), IL-1β (10ng/ml), IL-6 (10ng/ml), and PGE2 (10−6M) in the presence or absence of IFNβ (1,000 IU/ml), or LPS (1µg/ml). The expression of MHCII, CD40, CD80, and CD86 was analyzed by FACS. Dotted lines in the left panels represent isotype controls. (B, left panel) RNA was extracted from DC treated as above and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for CCR7. (B, right panel) DC were treated with LPS in the absence or presence of IFNβ, with or without neutralizing anti-IFNβ antibody (10µg/ml) or control IgG (10µg/ml) for 24h. Neutralizing anti-IFNβ antibody and control IgG were added twice: 30min before and 12h after LPS. RNA was extracted and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for CCR7. (C) DC were treated with the cytokine cocktail in the presence or absence of IFNβ for 24h and surface CCR7 expression was analyzed by FACS. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

IFNβ inhibition of CCR7 expression in mature DC is mediated through STAT-1

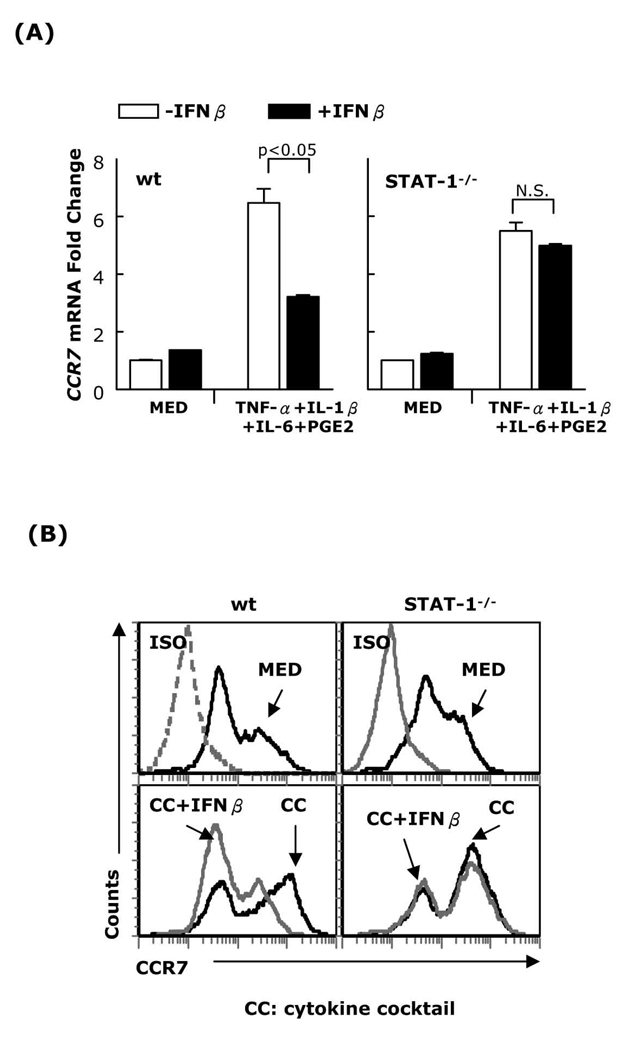

IFNβ signals through STAT-1/STAT-2 heterodimers and to a lesser degree through STAT-1 homodimers. To determine whether IFNβ inhibits CCR7 expression through STAT-1 activation, DC generated from STAT-1−/− and wt mice were matured with the cytokine cocktail in the presence or absence of IFNβ, followed by real-time RT-PCR and FACS analysis for CCR7 expression. IFNβ inhibited the expression of CCR7 in wt (129S6/SvEv) but not in STAT-1−/− DC (Fig. 2A–B). This effect was not due to a defect in STAT-1-/- DC maturation since the cytokine cocktail upregulated STAT-1-/-DC CD40, CD80, and CD86 expression (Supplemental Fig. 2). These results indicate that the inhibitory effect of IFNβ on CCR7 expression is mediated through activation of STAT-1.

Fig. 2. IFNβ inhibition of CCR7 expression in mature DC is mediated through STAT-1.

DC generated from wt or STAT-1−/− mice were matured with a cytokine cocktail (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2) in the presence or absence of IFNβ (1,000 IU/ml) for 24h. (A) RNA was extracted and subjected to CCR7 real-time RT-PCR; (B) surface CCR7 expression was analyzed by FACS. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

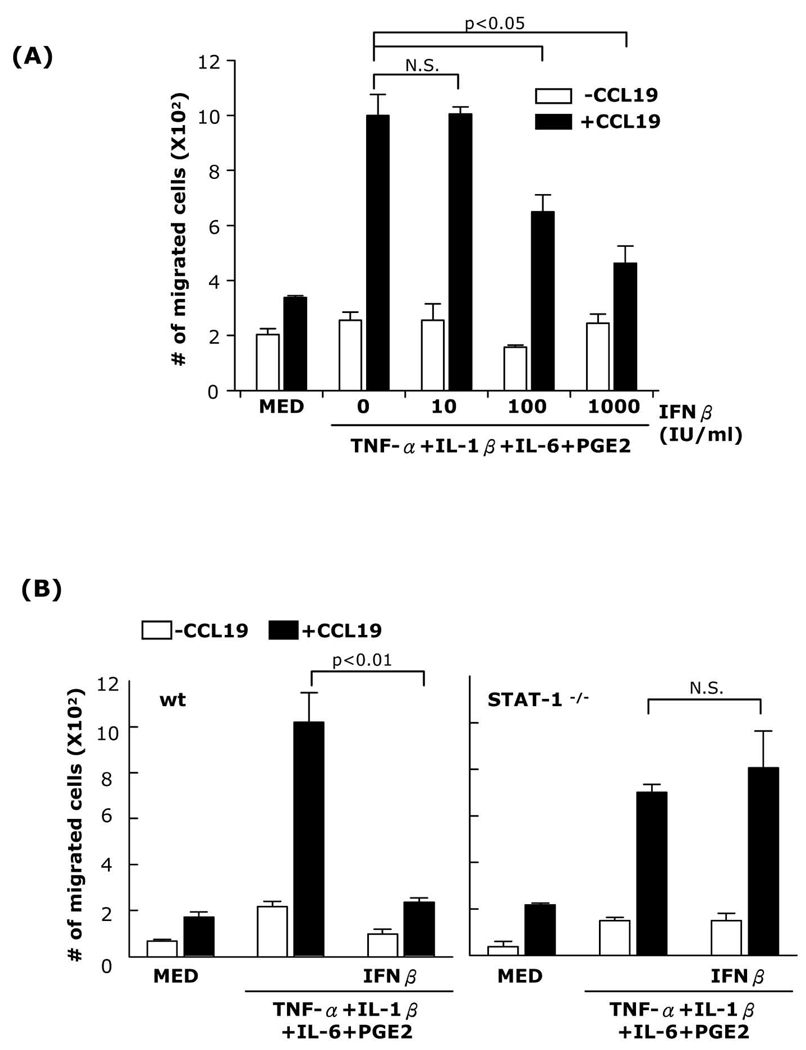

IFNβ inhibits DC chemotaxis

To investigate whether decreased CCR7 expression by IFNβ also affects DC migration in response to CCL19, DC were matured with TNFα+IL-1β+IL-6+PGE2, TNF-α+IFNα+PGE2, or Poly I:C+ PGE2 in the presence or absence of IFNβ and subjected to chemotactic migration assays. IFNβ inhibited TNF-α+IL-1β+IL-6+PGE2-matured DC migration in a dose-dependent manner with 1,000 IU/ml IFNβ reducing migration almost to the level of immature DC (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained for DC matured with either TNF-α+IFNα+PGE2 or Poly I:C+PGE2 (Supplemental Fig. 3A–B). As expected from the lack of effect of IFNβ on CCR7 expression in STAT-1−/− DC matured with a cytokine cocktail, IFNβ did not reduce the chemotactic migration of STAT-1−/− DC (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Inhibition of DC chemotactic migration by IFNβ is dose-dependent and mediated through STAT-1.

(A) DC were matured in the presence of different concentrations of IFNβ (10, 100, or 1,000 IU/ml) for 24h. (B) DC generated from wt or STAT-1−/− mice were matured in the presence or absence of IFNβ (1,000 IU/ml) for 24h. Chemotaxis towards CCL19 was performed in Transwell plates. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

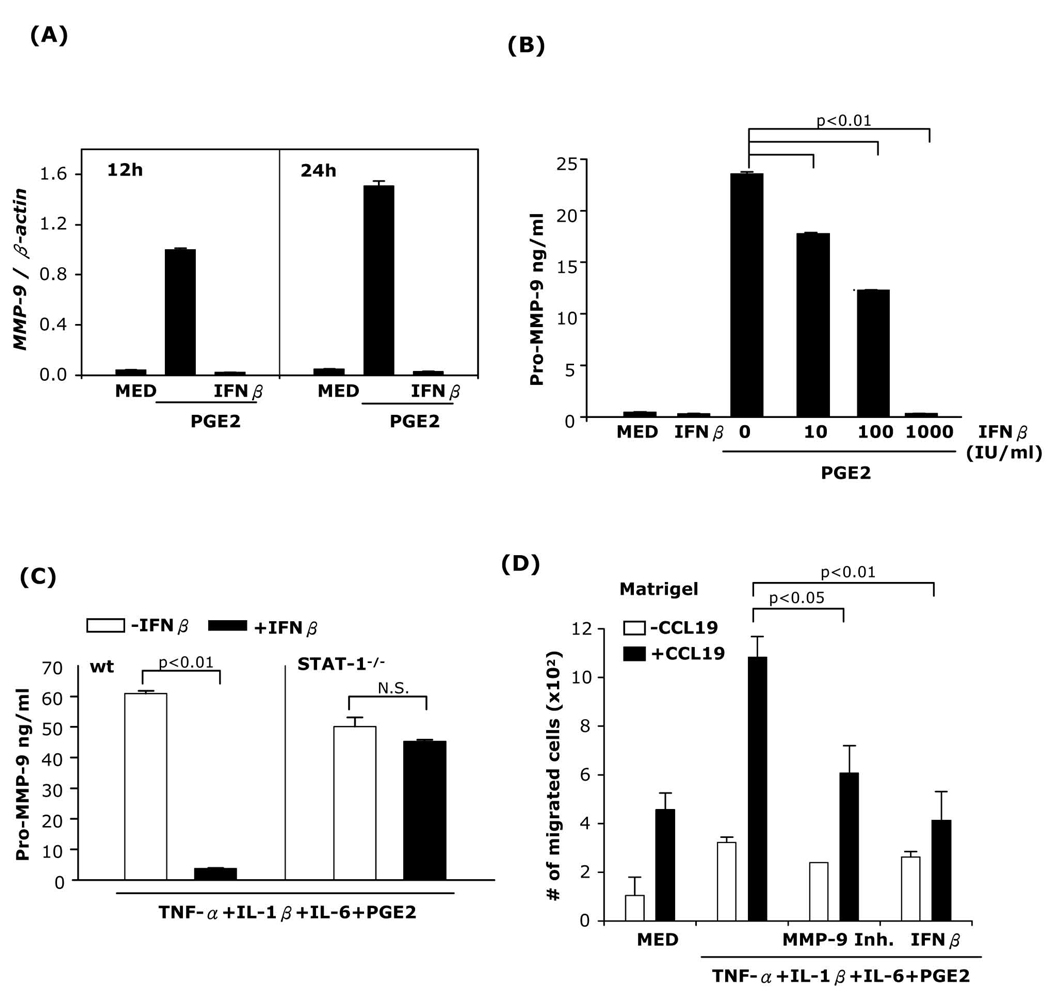

IFNβ inhibits PGE2-induced MMP-9 expression in immature and mature DC through STAT-1 signaling

We have previously reported that PGE2 induced MMP-9 production in immature and mature bone marrow-derived DC (9). To examine whether IFNβ inhibits MMP-9 mRNA expression in immature DC, DC were treated with PGE2 in the presence or absence of IFNβ, and MMP-9 mRNA expression was determined. IFNβ abolished PGE2-induced MMP-9 expression (Fig. 4A). Next, DC were treated with PGE2 and different concentrations of IFNβ followed by ELISA for pro-MMP-9. IFNβ reduced MMP-9 release in a dose-dependent manner, with 1,000 IU/ml IFNβ abolishing PGE2-induced MMP-9 production (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained for MMP-9 production in DC matured with TNF-α+IFNα+PGE2 or Poly I:C+PGE2 (Supplemental Fig. 4A–B).

Fig. 4. IFNβ inhibits PGE2-induced MMP-9 expression and Matrigel DC migration.

(A) DC were treated with PGE2 (10−6M) with or without IFNβ (1,000 IU/ml) and RNA was extracted at different time points and subjected to MMP-9 real-time RT-PCR. (B) DC were treated with PGE2 in the absence or presence of different concentrations of IFNβ for 48h, followed by ELISA for secreted pro-MMP-9. (C) DC generated from wt or STAT-1−/− mice were matured in the presence or absence of IFNβ for 24h. Secreted pro-MMP-9 levels were determined by ELISA. (D) DC were treated with TNF-α+IL-1β+IL-6+PGE2 in the presence or absence of MMP-9 inhibitor I (10−6M), or IFNβ for 24h, and subjected to Matrigel migration assays. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

To evaluate the role of STAT-1 in the effects of IFNβ on MMP-9 expression, DC generated from STAT-1−/− and wt mice were matured in the presence or absence of IFNβ. PGE2-induced MMP-9 production was abolished by IFNβ in DC from wt but not from STAT-1−/− mice (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that the inhibitory effect of IFNβ on MMP-9 expression is mediated through STAT-1 activation.

We have shown previously that MMP-9 expression is essential for migration of DC in response to CCL19 through Matrigel, the in vitro basement membrane model (9). To examine the effect of IFNβ on DC Matrigel migration, we matured DC with the cytokine cocktail in the presence or absence of IFNβ or of the MMP-9 inhibitor I. A substantial number of DC matured with the cytokine cocktail migrated across the Matrigel barrier. The numbers of migrated DC were significantly lower when the cells were exposed to the MMP-9 inhibitor or to IFNβ (Fig. 4D).

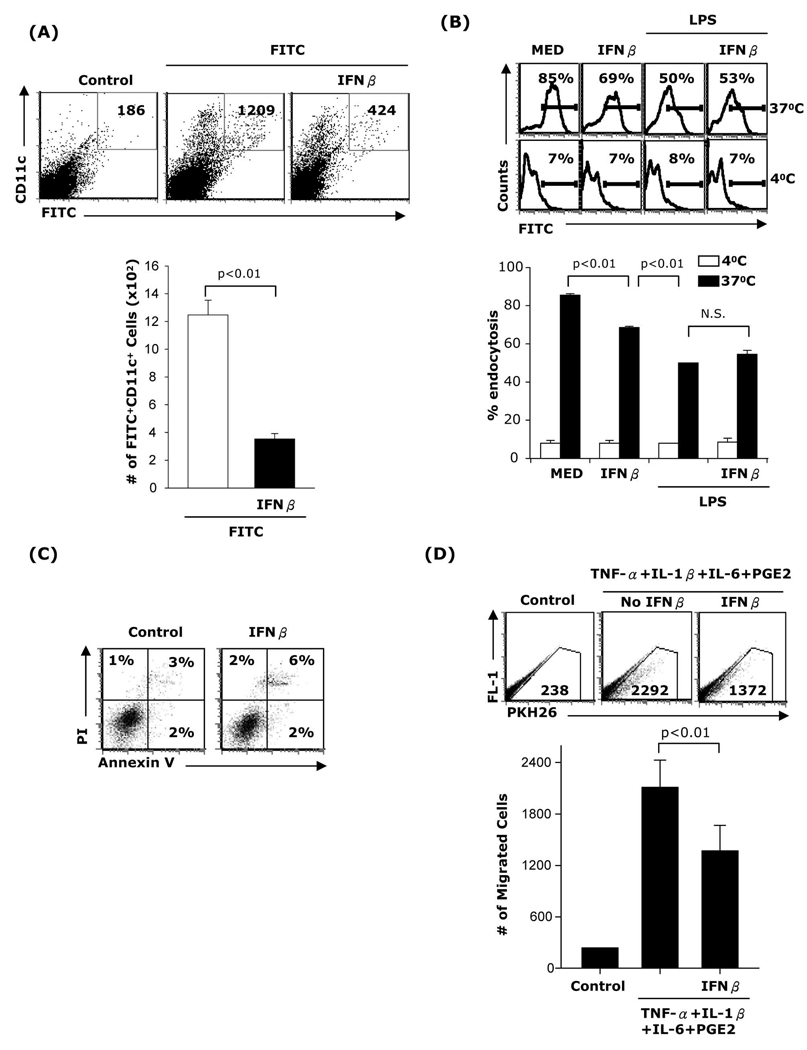

IFNβ inhibits DC migration in vivo

To assess whether administration of IFNβ affects DC migration in vivo, BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with IFNβ at −12h, −1h, and +12h of application of FITC contact sensitizer. 24h after FITC application, cells from draining lymph nodes were stained with PE anti-mouse CD11c and FITC/PE double-positive cells were determined by FACS analysis. Lymph node cells from control mice which received vehicle were stained with CD11c isotype and used to set up the gates to eliminate autofluorescence. Three-four fold lower numbers of CD11c+FITC+ cells were detected in the draining lymph nodes of mice that were treated with IFNβ (Fig 5A).

Fig. 5. IFNβ inhibits DC migration in vivo.

(A) B10.A mice were injected i.p. with PBS (400µl; control) or IFNβ (10,000 IU) 12h and 1h before and 12h after FITC application (100µl of 10mg/ml FITC in a 50:50 (vol/vol) acetone/dibutylphthalate). 24h after FITC application inguinal lymph node cells were subjected to staining with PE anti-CD11c. Double positive cells (FITC/PE) were counted by FACS. Two separate experiments (n=6) were performed with similar results. (B) CD11c+ DC were treated with IFNβ, LPS, or LPS+IFNβ for 24h followed by an endocytosis assay. (C) CD11c+ DC were pretreated with IFNβ for 24h, treated with FITC-dextran 1.25µg/ml for 24h and apoptosis was evaluated by FACS. Data are representative of three independent experiments for (B) and two independent experiments for (C). (D) DC were matured with TNF-α+IL-1β+IL-6+PGE2 in the presence or absence of IFNβ for 48h. DCs were collected and labeled with the PKH 26 red fluorescent dye. B10.A mice (n=3) were preinjected with 40ng TNF-α s.c in the footpads of each of the hind legs and 24h later the mice were inoculated with DC (1×106 cells in 60 µl, s.c in the footpads). The draining popliteal lymph nodes were harvested 48h later and the numbers of labeled cells were determined by FACS. Results are expressed as numbers of fluorescent cells per 100,000 lymph node cells.

The reduced numbers of lymph node derived FITC+ DC in IFNβ treated mice could be due to effects of IFNβ on DC endocytic capacity and/or viability. To address this issue we evaluated first the effect of IFNβ on endocytosis. Bone marrow-derived CD11c+ DC were treated with IFNβ for 24h and exposed to FITC-dextran for 2h. IFNβ treated DC exhibited an approximately 20% reduction in endocytic capacity (Fig. 5B). This reduction is substantially less than the decrease in the numbers of lymph node derived FITC+ DC after in vivo IFNβ administration (70–80%). To assess the effect of IFNβ on DC viability, we treated purified CD11c+ DC with IFNβ for 24h followed by FITC-dextran for another 24h and apoptosis was evaluated by Annexin V/PI staining. We did not observe significant differences between DC treated with or without IFNβ (Fig. 5C).

In a different experimental approach, fluoresently labeled DC matured in vitro with or without IFNβ were injected subcutaneously into the footpads of B10.A mice preinjected 24h hours earlier with TNF-α to activate vascular/lymphatic endothelial cells. 24h later the labeled DC were harvested from the draining lymph nodes and counted by FACS. Lymph node cells from mice not injected with DC were used to eliminate autofluorescence. DC treated with the cytokine cocktail without IFNβ migrated in higher numbers compared to DC treated with IFNβ (Fig. 5D).

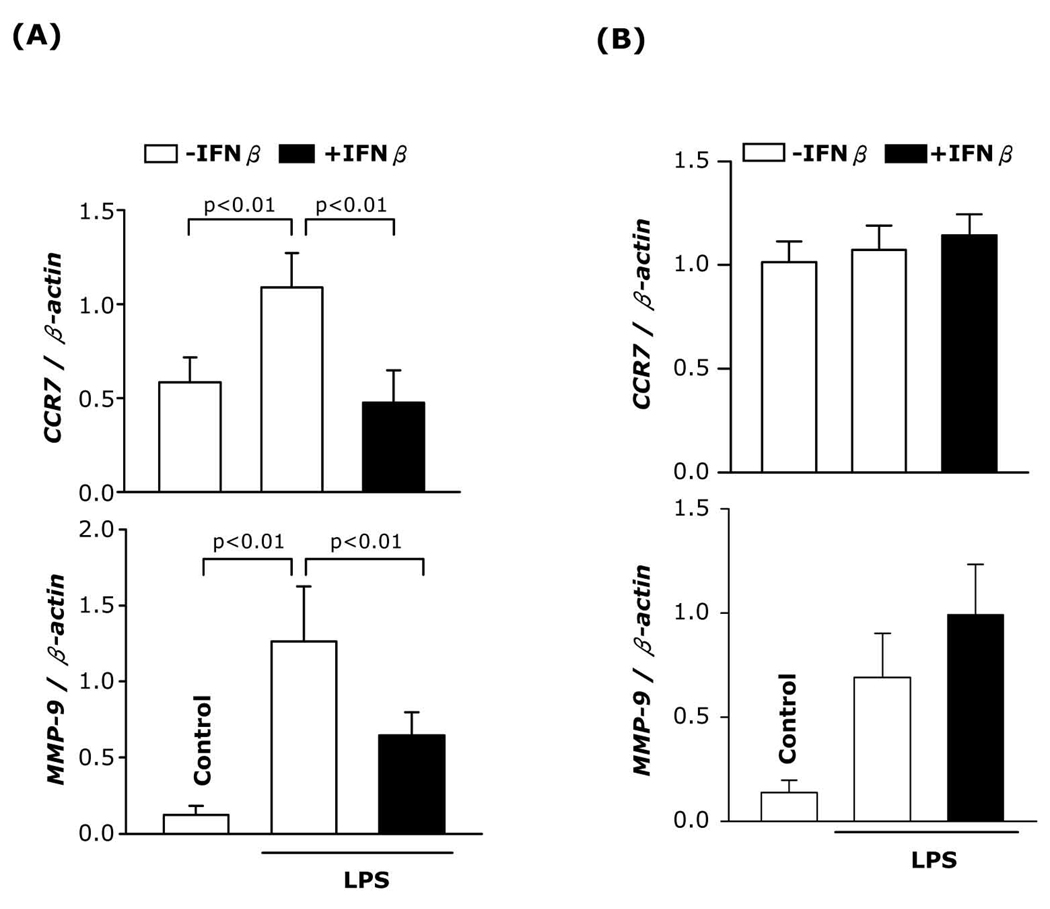

IFNβ inhibits in vivo CCR7 and MMP-9 expression in splenic DC

To further examine the in vivo effect of IFNβ, BALB/c mice were injected with IFNβ 12h and 1h before and 12h after LPS inoculation. 24h after LPS administration, immunomagnetically enriched splenic CD11c+ cells were analyzed for CCR7 and MMP-9 mRNA expression. As expected, LPS induced CCR7 and MMP-9 expression. In contrast, the in vivo administration of IFNβ prevented LPS-induced CCR7 and MMP-9 expression (Fig. 6A). These results confirm the in vitro experiments and extend the observation regarding the effect of IFNβ on CCR7 and MMP-9 expression to splenic DC.

Fig. 6. IFNβ inhibits in vivo CCR7 and MMP-9 expression in splenic DC.

(A) BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with LPS (100µg) or PBS (control). IFNβ (10,000 IU in 400µl PBS) was administered i.p. at times −12h, −1h and +12h in regards to LPS. 24h after LPS administration, RNA was prepared from purified (A) splenic enriched CD11c+ cell populations and (B) CD4+ T cells following RT-PCR for CCR7 and MMP-9 expressions. Two independent experiments (n=6) were performed.

CD4+ T cells were the major contaminant present in the enriched splenic DC preparations. To rule out the possibility that the IFNβ-induced decrease in CCR7 and MMP-9 expression was due to T cells, we purified splenic CD4+ T cells (>97% by FACS analysis) from spleens of control mice, or mice injected with LPS or LPS plus IFNβ and determined CCR7 and MMP-9 expression. In vivo administration of LPS or LPS plus IFNβ did not alter CCR7 expression in CD4+ T cells. Although LPS induced MMP-9 expression, IFNβ did not inhibit the LPS-induced MMP-9 expression in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that in vivo administration of IFNβ inhibits CCR7 and MMP-9 expression in splenic CD11c+ DC.

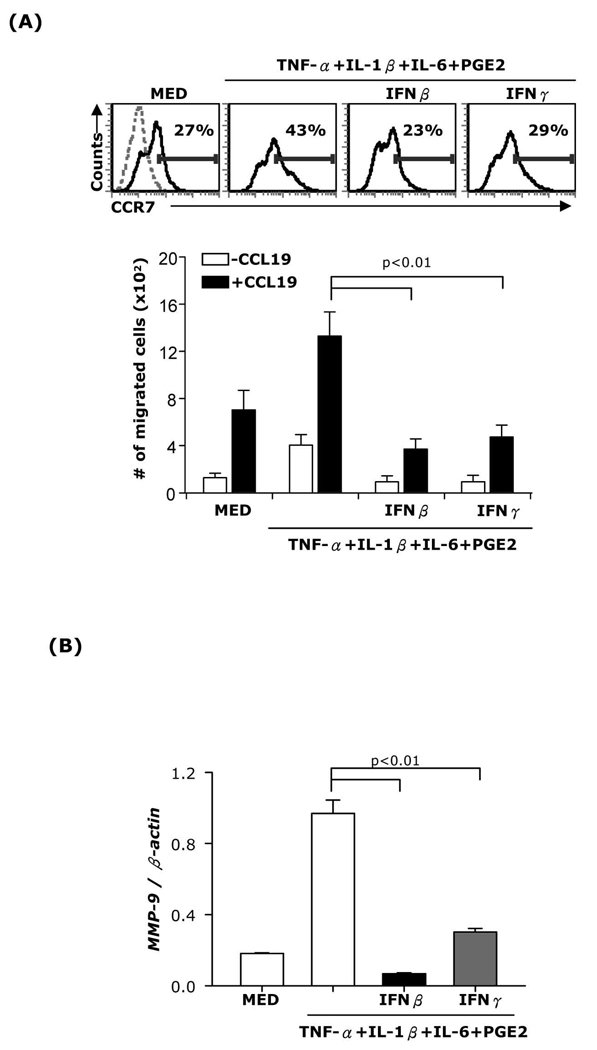

IFNβ and IFNγ have similar effects on DC CCR7 and MMP-9 expression but differ in terms of effects on DC IL-12 production and stimulatory capacity for CD4+ T cells

Our experiments indicate that the inhibitory effect of IFNβ on mature DC migration, CCR7 and MMP-9 expression is mediated through STAT-1. STAT-1 plays an essential role in both IFNβ and IFNγ signaling. To test whether IFNγ exerts similar effects, we measured CCR7 and MMP-9 expression as well as chemotaxis in DC matured with the cytokine cocktail and treated with either IFNβ or IFNγ. Similar to IFNβ, IFNγ inhibited CCR7 and MMP-9 mRNA expression (Fig. 7A-upper panel and 7B) and prevented DC migration in response to CCL19 (Fig. 7A-lower panel).

Fig. 7. Effects of IFNβ and IFNγ on DC CCR7 and MMP-9 expression.

CD11c+ DC were matured with TNF-α+IL-1β+IL-6+PGE2 in the presence or absence of IFNβ (1,000 IU/ml) or IFNγ (100ng/ml) for 24h. (A, top) surface CCR7 expression was analyzed by FACS. (A, bottom) Chemotaxis towards CCL19 was performed or (B) RNA was extracted and subjected to MMP-9 real-time RT-PCR. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

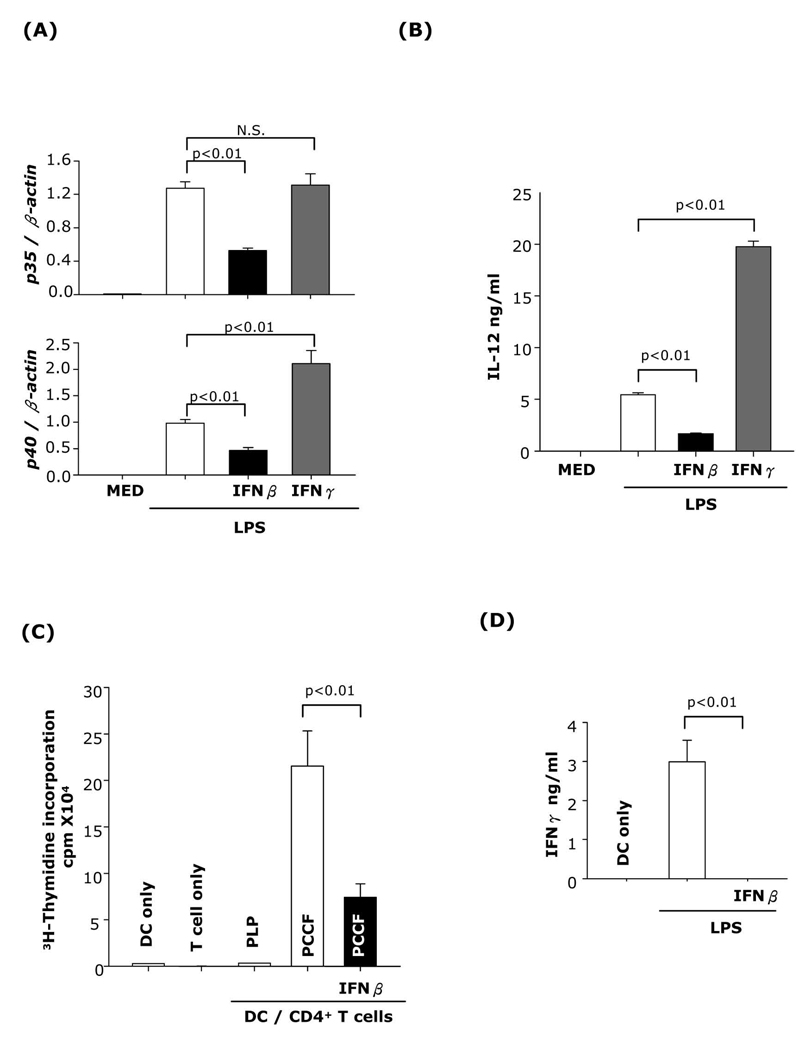

IFNγ has been shown to enhance IL-12 production in DC and macrophages and subsequently to promote Th1 differentiation. As expected, we observed increased IL-12p40 expression and significantly higher levels of secreted IL-12p70 in DC matured with LPS in the presence of IFNγ. In contrast, DC treated with IFNβ expressed lower levels of IL-12p35 and p40, and reduced levels of secreted IL-12p70 (Fig. 8A and B). Next, we evaluated the capacity of IFNβ-treated DC to stimulate T cell proliferation and differentiation into IFNγ-producing Th1 cells. DC matured with LPS in the presence or absence of IFNβ were pulsed with PCCF (specific Ag) or PLP (nonspecific Ag) and cocultured with PCCF-specific TCR transgenic splenic CD4+ T cells. IFNβ-treated DC were poor T cell stimulators and did not induce functional Th1 cells as determined by IFNγ release (Fig. 8C and D).

Fig. 8. The effects of IFNβ and IFNγ on DC IL-12 production and stimulatory capacity for CD4+ T cells.

CD11c+ DC were pretreated with IFNβ or IFNγ for 1h followed by LPS (1µg/ml) stimulation. (A) 6h after LPS treatment, RNA was extracted and subjected to IL-12p35 and IL-12p40 real-time RT-PCR. (B) 24h after LPS treatment, the supernatants were collected and subjected to IL-12p70 ELISA. (C) DC (1×104 cells/well) were pretreated with or without IFNβ, stimulated with LPS and pulsed with PCCF (5µM) or PLP (20µg; nonspecific Ag). DC were cocultured with PCCF-specific Tg CD4+ T cells (1×105 cells/well). On day 3 of coculture, 3H-thymidine (1µCi per well) was added and incorporation was measured after 16h. (D) Supernatants were collected and subjected to IFNγ ELISA. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Currently, IFNβ represents a mainstay of immunomodulatory therapy in MS, although some patients develop autoantibodies which abolish the efficacy of IFNβ therapy within a year of treatment [reviewed in (16)]. Several studies have also shown therapeutic effects of IFNβ in EAE models which share clinical and histopathological features with MS (17–20). The beneficial effect of IFNβ is supported by the fact that both IFNβ-deficient and type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) knockout mice develop more severe EAE (17, 21).

The molecular mechanisms involved in the beneficial effect of IFNβ in MS/EAE have not been completely elucidated. Putative mechanisms include effects on the expression of adhesion molecules, cytokines, alterations of the Th1/Th2 balance in favor of Th2 differentiation, decrease in blood brain barrier permeability, induction of regulatory T cells, and negative regulation of Th17 differentiation (17, 19, 20, 22–25). A recent study showed that absence of IFNAR on myeloid cells, but not on B and T lymphocytes or on neuroectodermal CNS cells, leads to severe disease and increased lethality (26). Since myeloid DC migrating from the periphery into the perivascular space play an important role in the EAE reactivation of myelin-specific CD4+T cells (5, 6), the effect of IFNβ on DC migration is of interest, and could represent a new molecular mechanism for its therapeutic effect.

Our results indicate that IFNβ prevents CCR7 and MMP-9 expression in mature myeloid DC in vitro and in vivo, reducing their in vivo migration to the draining lymph nodes and the in vitro migration in response to the lymph node-derived chemokine CCL19. The effects of IFNβ on CCR7 and MMP-9 expression and on DC migration are mediated through STAT-1.

In contrast to its effect on the expression of costimulatory molecules in DC matured with the cytokine cocktail, IFNβ prevented CCR7 upregulation during DC maturation. Prevention of CCR7 upregulation during DC maturation might represent a more general mechanism for immunosuppressive cytokines, since similar effects were reported for the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGFβ (27, 28). The involvement of STAT-1 in the negative regulation of CCR7 is a new finding. Previous studies referring to the inhibition of CCR7 reported the involvement of the PI3K signaling cascade (28) and of PPARγ (27). The involvement of STAT-1 is also supported by the fact that IFNγ, which also uses STAT-1 for signaling, has a similar inhibitory effect on CCR7 expression [our results and (29)].

Although necessary, CCR7 expression is not sufficient to induce DC migration (30, 31). Lipid mediators, particularly PGE2 have been shown to induce migration of maturing DC (31, 32). Previously, we have shown that PGE2 induces high levels of MMP-9 expression in cytokine cocktail-matured myeloid DC (9). MMPs are major participants in cell migration through the degradation of extracellular matrix and of the basement membrane [reviewed in (33, 34)]. MMP-2 and −9 are especially important in migration, since they cleave collagen IV, a major component of basement membranes. The role of MMP-9 in DC migration in response to proinflammatory and lymph node-derived chemokines has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo (35–37). Recently, DC transmigration through brain capillary endothelial cell monolayers has also been shown to depend on MMPs (38). In addition, DC from MS patients were reported to secrete high levels of MMP-2, -3, and -9, and to exhibit increased spontaneous migration over ECM-coated filters (39).

Here we report on the IFNβ-induced inhibition of MMP-9 expression and production in myeloid DC. Our results indicate the role of STAT-1 in the inhibition of MMP-9 expression by IFNβ. The fact that IFNγ has similar effects suggests that STAT-1 is an important negative regulator of MMP-9 expression. The possible contribution of another important IFNβ signaling molecule, STAT-2, remains to be investigated. Although the effect of IFNβ on MMP-9 expression in DC is a new finding, previous studies reported similar effects in other cell types such as astrocytes and CD4+ T cells from MS patients (40, 41). In fibrosarcoma cell lines deficient in STAT-1, STAT-2 or IRF-9, inhibition of MMP-9 by IFNβ was shown to depend on all three signaling molecules (42).

In agreement with the role of STAT-1 in IFNβ and IFNγ signaling, we report here that both IFNβ and IFNγ inhibit CCR7 and MMP-9 expression in bone marrow-derived DC and suppress their migration in response to CCL19. Also, previous studies reported that IFNγ inhibited CCR7 expression in human monocyte-derived DC and their migration towards CCL19 (4, 29). However, in contrast to IFNβ, IFNγ therapy induced acute relapses in MS (43). Opposite effects of IFNβ and IFNγ on the cytokine profile of mature DC, followed by different effects on T cell differentiation, might provide an explanation. The role of IFNγ in promoting APC expression of IL-12, an essential factor for Th1 differentiation, is well known. In the present study we compared the effects of IFNβ and IFNγ on IL-12 production by LPS-treated DC. As expected, IFNγ induced higher IL-12p40 expression and significantly higher levels of secreted IL-12p70. In contrast, IFNβ reduced both p40 and p35 expression levels and significantly inhibited IL-12 release. This is in agreement with previous reports of IL-12 inhibition by IFNβ in vivo and in vitro (18, 20, 44, 45). Consistent with the IFNβ-induced inhibition of IL-12 production, we also observed significant inhibitory effects on the capacity of LPS-matured DC to activate CD4+ T cells and to induce IFNγ-producing Th1 cells. Similar findings were reported in vitro for IFNβ-treated human DC and autologous T cells (46, 47), and in vivo in models of collagen-induced arthritis and EAE (18, 45). It should be mentioned that although studies involving the effect of IFNβ on APCs and subsequently on T cells support an inhibitory effect on Th1 differentiation, in vitro studies with purified CD4+ T cells in systems that do not include functionally active APCs show that IFNβ promotes Th1 development (48–50). Whether IFNβ induces Th1 differentiation in vivo, in the presence of functionally active APCs, remains to be established.

In our previous studies (9) we showed that PGE2 induces MMP-9 expression in DC matured with TNFα+IFNα, a cytokine cocktail previously reported to mature DC. The experiments reported in this manuscript show that IFNβ inhibits MMP-9 expression in PGE2-treated DC matured with various cytokine cocktails or with TRL ligands. Since both IFNα and β bind to the same receptor, we compared the effects of IFNα and IFNβ on PGE2 induction of MMP-9 in TNFα-matured DC. At the same concentration (1000 U/ml), IFNα reduced, whereas IFNβ abolished MMP-9 production (results not shown). Therefore, both IFNs have the same qualitative effect, although they differ in terms of quantitative effects. The difference in efficiency is presumably due to the fact that IFNα has a lower affinity for the type I IFN receptor (51, 52), which could lead to differences in the intensity or nature of signaling pathways. Indeed, we observed less efficient STAT-1 phosphorylation (both in terms of percentage positive cells and intensity of fluorescence) for IFNα-treated DC as compared to the IFNβ treatment (results not shown).

Our present study describes a novel mechanism for the physiological and therapeutic function of IFNβ through its effects on CCR7, MMP-9 and migration of mature DC. This is in addition to IFNβ promoting apoptosis of mature DC as recently described by us and Mattei and colleagues (53, 54). The effects of IFNβ on DC survival, migration, and cytokine profile broaden the field of molecular mechanisms involved in the beneficial effect of IFNβ in autoimmune diseases, particularly in EAE/MS, and introduce myeloid DC as an important target for IFNβ therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH/NIAID grant RO1AI052306 (DG).

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cells

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- IFNAR

IFN type I receptor

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase 9

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PCCF

pigeon cytochrome C fragment

- PLP

proteolipid protein

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- Tg

transgenic

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez D, Vollmann EH, von Andrian UH. Mechanisms and consequences of dendritic cell migration. Immunity. 2008;29:325–342. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miossec P. Dynamic interactions between T cells and dendritic cells and their derived cytokines/chemokines in the rheumatoid synovium. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10 Suppl 1:S2. doi: 10.1186/ar2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lande R, Gafa V, Serafini B, Giacomini E, Visconti A, Remoli ME, Severa M, Parmentier M, Ristori G, Salvetti M, Aloisi F, Coccia EM. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis: intracerebral recruitment and impaired maturation in response to interferon-beta. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:388–401. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31816fc975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu GF, Laufer TM. The role of dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:245–252. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey SL, Schreiner B, McMahon EJ, Miller SD. CNS myeloid DCs presenting endogenous myelin peptides 'preferentially' polarize CD4+ T(H)-17 cells in relapsing EAE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:172–180. doi: 10.1038/ni1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller SD, McMahon EJ, Schreiner B, Bailey SL. Antigen presentation in the CNS by myeloid dendritic cells drives progression of relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1103:179–191. doi: 10.1196/annals.1394.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markowitz CE. Interferon-beta: mechanism of action and dosing issues. Neurology. 2007;68:S8–S11. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277703.74115.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jing H, Yen JH, Ganea D. A novel signaling pathway mediates the inhibition of CCL3/4 expression by prostaglandin E2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55176–55186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen JH, Khayrullina T, Ganea D. PGE2-induced metalloproteinase-9 is essential for dendritic cell migration. Blood. 2008;111:260–270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macatonia SE, Knight SC, Edwards AJ, Griffiths S, Fryer P. Localization of antigen on lymph node dendritic cells after exposure to the contact sensitizer fluorescein isothiocyanate. Functional and morphological studies. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1654–1667. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.6.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieu MC, Vanbervliet B, Vicari A, Bridon JM, Oldham E, Ait-Yahia S, Briere F, Zlotnik A, Lebecque S, Caux C. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med. 1998;188:373–386. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sallusto F, Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Schaniel C, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Qin S, Lanzavecchia A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2760–2769. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2760::AID-IMMU2760>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagihara S, Komura E, Nagafune J, Watarai H, Yamaguchi Y. EBI1/CCR7 is a new member of dendritic cell chemokine receptor that is up-regulated upon maturation. J Immunol. 1998;161:3096–3102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieseier BC, Wiendl H, Leussink VI, Stuve O. Immunomodulatory treatment strategies in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255 Suppl 6:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-6004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo B, Chang EY, Cheng G. The type I IFN induction pathway constrains Th17-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1680–1690. doi: 10.1172/JCI33342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makar TK, Trisler D, Bever CT, Goolsby JE, Sura KT, Balasubramanian S, Sultana S, Patel N, Ford D, Singh IS, Gupta A, Valenzuela RM, Dhib-Jalbut S. Stem cell based delivery of IFN-beta reduces relapses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;196:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Saavedra FM, Gonzalez-Garcia C, Bravo B, Ballester S. Beta interferon restricts the inflammatory potential of CD4+ cells through the boost of the Th2 phenotype, the inhibition of Th17 response and the prevalence of naturally occurring T regulatory cells. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:4008–4019. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuohy VK, Yu M, Yin L, Mathisen PM, Johnson JM, Kawczak JA. Modulation of the IL-10/IL-12 cytokine circuit by interferon-beta inhibits the development of epitope spreading and disease progression in murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;111:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teige I, Treschow A, Teige A, Mattsson R, Navikas V, Leanderson T, Holmdahl R, Issazadeh-Navikas S. IFN-beta gene deletion leads to augmented and chronic demyelinating experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4776–4784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Floris S, Ruuls SR, Wierinckx A, van der Pol SM, Dopp E, Van der Meide PH, Dijkstra CD, De Vries HE. Interferon-beta directly influences monocyte infiltration into the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;127:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harzheim M, Stepien-Mering M, Schroder R, Schmidt S. The expression of microfilament-associated cell-cell contacts in brain endothelial cells is modified by IFN-beta1a (Rebif) J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24:711–716. doi: 10.1089/jir.2004.24.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhaus O, Archelos JJ, Hartung HP. Immunomodulation in multiple sclerosis: from immunosuppression to neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:131–138. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yong VW. Differential mechanisms of action of interferon-beta and glatiramer aetate in MS. Neurology. 2002;59:802–808. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prinz M, Schmidt H, Mildner A, Knobeloch KP, Hanisch UK, Raasch J, Merkler D, Detje C, Gutcher I, Mages J, Lang R, Martin R, Gold R, Becher B, Bruck W, Kalinke U. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of IFNAR on myeloid cells limit autoimmunity in the central nervous system. Immunity. 2008;28:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fainaru O, Shay T, Hantisteanu S, Goldenberg D, Domany E, Groner Y. TGFbeta-dependent gene expression profile during maturation of dendritic cells. Genes Immun. 2007;8:239–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knodler A, Schmidt SM, Bringmann A, Weck MM, Brauer KM, Holderried TA, Heine AK, Grunebach F, Brossart P. Post-transcriptional regulation of adapter molecules by IL-10 inhibits TLR-mediated activation of antigen-presenting cells. Leukemia. 2009;23:535–544. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alder J, Hahn-Zoric M, Andersson BA, Karlsson-Parra A. Interferon-gamma dose-dependently inhibits prostaglandin E2-mediated dendritic-cell-migration towards secondary lymphoid organ chemokines. Vaccine. 2006;24:7087–7094. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robbiani DF, Finch RA, Jager D, Muller WA, Sartorelli AC, Randolph GJ. The leukotriene C(4) transporter MRP1 regulates CCL19 (MIP-3beta, ELC)-dependent mobilization of dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Cell. 2000;103:757–768. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scandella E, Men Y, Gillessen S, Forster R, Groettrup M. Prostaglandin E2 is a key factor for CCR7 surface expression and migration of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. y2002;100:1354–1361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legler DF, Krause P, Scandella E, Singer E, Groettrup M. Prostaglandin E2 is generally required for human dendritic cell migration and exerts its effect via EP2 and EP4 receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176:966–973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:617–629. doi: 10.1038/nri1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster NL, Crowe SM. Matrix metalloproteinases, their production by monocytes and macrophages and their potential role in HIV-related diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1052–1066. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chabot V, Reverdiau P, Iochmann S, Rico A, Senecal D, Goupille C, Sizaret PY, Sensebe L. CCL5-enhanced human immature dendritic cell migration through the basement membrane in vitro depends on matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:767–778. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollender P, Ittelett D, Villard F, Eymard JC, Jeannesson P, Bernard J. Active matrix metalloprotease-9 in and migration pattern of dendritic cells matured in clinical grade culture conditions. Immunobiology. 2002;206:441–458. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratzinger G, Stoitzner P, Ebner S, Lutz MB, Layton GT, Rainer C, Senior RM, Shipley JM, Fritsch P, Schuler G, Romani N. Matrix metalloproteinases 9 and 2 are necessary for the migration of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells from human and murine skin. J Immunol. 2002;168:4361–4371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zozulya AL, Reinke E, Baiu DC, Karman J, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Dendritic cell transmigration through brain microvessel endothelium is regulated by MIP-1alpha chemokine and matrix metalloproteinases. J Immunol. 2007;178:520–529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kouwenhoven M, Ozenci V, Tjernlund A, Pashenkov M, Homman M, Press R, Link H. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells express and secrete matrix-degrading metalloproteinases and their inhibitors and are imbalanced in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;126:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dressel A, Mirowska-Guzel D, Gerlach C, Weber F. Migration of T-cell subsets in multiple sclerosis and the effect of interferon-beta1a. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:164–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma Z, Qin H, Benveniste EN. Transcriptional suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene expression by IFN-gamma and IFN-beta: critical role of STAT-1alpha. J Immunol. 2001;167:5150–5159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao X, Nozell S, Ma Z, Benveniste EN. The interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 complex mediates the inhibitory effect of interferon-beta on matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression. Febs J. 2007;274:6456–6468. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panitch HS, Bever CT., Jr Clinical trials of interferons in multiple sclerosis. What have we learned? J Neuroimmunol. 1993;46:155–164. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90245-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McRae BL, Beilfuss BA, van Seventer GA. IFN-beta differentially regulates CD40-induced cytokine secretion by human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:23–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Triantaphyllopoulos KA, Williams RO, Tailor H, Chernajovsky Y. Amelioration of collagen-induced arthritis and suppression of interferon-gamma, interleukin-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha production by interferon-beta gene therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:90–99. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<90::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagai T, Devergne O, Mueller TF, Perkins DL, van Seventer JM, van Seventer GA. Timing of IFN-beta exposure during human dendritic cell maturation and naive Th cell stimulation has contrasting effects on Th1 subset generation: a role for IFN-beta-mediated regulation of IL-12 family cytokines and IL-18 in naive Th cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2003;171:5233–5243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schreiner B, Mitsdoerffer M, Kieseier BC, Chen L, Hartung HP, Weller M, Wiendl H. Interferon-beta enhances monocyte and dendritic cell expression of B7-H1 (PD-L1), a strong inhibitor of autologous T-cell activation: relevance for the immune modulatory effect in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;155:172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byrnes AA, Li DY, Park K, Thompson D, Mocilnikar C, Mohan P, Molleston JP, Narkewicz M, Zhou H, Wolf SF, Schwarz KB, Karp CL. Modulation of the IL-12/IFN-gamma axis by IFN-alpha therapy for hepatitis C. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:825–834. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1006622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parronchi P, Mohapatra S, Sampognaro S, Giannarini L, Wahn U, Chong P, Mohapatra S, Maggi E, Renz H, Romagnani S. Effects of interferon-alpha on cytokine profile, T cell receptor repertoire and peptide reactivity of human allergen-specific T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:697–703. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wenner CA, Guler ML, Macatonia SE, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Roles of IFN-gamma and IFN-alpha in IL-12-induced T helper cell-1 development. J Immunol. 1996;156:1442–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gavutis M, Lata S, Lamken P, Muller P, Piehler J. Lateral ligand-receptor interactions on membranes probed by simultaneous fluorescence-interference detection. Biophys J. 2005;88:4289–4302. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaitin DA, Roisman LC, Jaks E, Gavutis M, Piehler J, Van der Heyden J, Uze G, Schreiber G. Inquiring into the differential action of interferons (IFNs): an IFN-alpha2 mutant with enhanced affinity to IFNAR1 is functionally similar to IFN-beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1888–1897. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1888-1897.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mattei F, Bracci L, Tough DF, Belardelli F, Schiavoni G. Type I IFN regulate DC turnover in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1807–1818. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yen JH, Ganea D. Interferon beta induces mature dendritic cell apoptosis through caspase-11/caspase-3 activation. Blood. 2009;114:1344–1354. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.