Abstract

The identification of novel DNA sequence motifs potentially participating in the regulation of gene transcription is a difficult task due to the small size and relative simplicity of the sequences involved. One possible way of overcoming this difficulty is to examine the promoter region of genes with similar expression profiles. Parameters of interest include similar tissue and cell-type specificity and quantitatively similar levels of mRNA in wild-type backgrounds. Tcp10b and Tctex1 are genes exhibiting these properties in that both are expressed at similar levels in pachytene spermatocytes of male mouse germ cells with little to no expression elsewhere. An analysis of the promoter region of these genes has uncovered a novel 20-nucleotide motif perfectly conserved in both. We have characterized the binding properties of this motif and show that it is specifically recognized by a 43 kD nuclear protein. The complex is highly stable and exhibits strong specificity. Furthermore, results from analyzing the sequence of several vertebrate genomes for the presence of the motif are consistent with the existence of a novel motif in the vicinity of several hundred genes.

Keywords: EMSA, DNA-binding protein, DNA motif, Tctex1, Tcp10b

INTRODUCTION

Tctex1 and Tcp10 are two gene complexes located within the mouse t complex of chromosome 17. Tctex1 consists of multiple (possibly four), contiguous genes in the inbred strain C3H that cluster into two types, A and B, based on differences in their promoter regions [1, 2]. This arrangement appears to be conserved in other strains, including CAST/Ei, 129/SvJ, Balb/cJ and C57BL/6J but not SPRET/Ei, where a single copy appears to be present (A. Planchart, unpublished). The Tcp10 complex consists of three contiguous genes referred to as Tcp10a, Tcp10b and Tcp10c [3, 4]. Tctex1 expression is ubiquitous yet it is most abundantly expressed in the testis [1]; however, expression from the Tcp10 complex is testis-restricted [3]. The expression of both gene complexes is first observed during the pachytene stage of spermatogenesis [1, 3].

Tctex1 encodes a dynein light chain [5] found in flagellar axonemal inner [6] and outer [7] dynein arms and in cytoplasmic dynein [8]. It is involved in the transport of rhodopsin in rod photoreceptors [9] and interacts with the poliovirus receptor, CD155 [10]. In the t haplotype, a variant form of the t complex found in approximately 25% of feral mice, the Tctex1 gene family harbors multiple mutations, at least one of which eliminates the start codon in the B subset. Mutations in the A subset are thought to affect the protein’s function [2]. Tctex1 maps to a region of the t complex known to be involved in transmission ratio distortion (TRD; reviewed in [11]) in t haplotype males, thus Tctex1 is a candidate for one of the proximal distorters, the other one being the recently cloned Tagap1, a GTPase-activating protein [12]. The genes encoded by the Tcp10 complex have no known function (although computationally-derived annotations suggest that the protein encoded by Tcp10c has patterns found in proteins that function in G-protein coupled receptor pathways; MGI Accession ID 98543). Transcription from either complex is not under the control of a TATA-box promoter, a phenomenon frequently seen in testis-expressed genes [13–15].

Functional and sequence characterizations of the upstream controlling regions of the genes within the Tctex1 complex have been performed [2]. Thus, a Germ-cell Inhibitory Motif (GIM) has been identified in the ‘A’ subset of the C3H Tctex1 complex that consists of an octanucleotide, ACCCTGAG, a sequence that bears some similarity to the mammalian AP-2 binding site [2]; in 129/SvJ, the last two nucleotides of the GIM are switched (ACCCTGGA, A. Planchart, unpublished). Interestingly, in the t haplotype alleles of Tctex1 genes, the GIM is absent having undergone a loss of nucleotides within the motif and surrounding sequence. Tctex1 expression in the testis of t haplotype males is highly upregulated compared to wild-type males and this phenomenon was attributed to the loss of the GIM.

An extensive analysis of the promoter region of Tcp10bt, the t haplotype allele of Tcp10b, has been conducted [16–18]. Promoter “bashing” approaches revealed that the sequence from−973 to−1 (where +1 indicates the start-site of transcription) is sufficient for the proper temporal and tissue-specific expression of a LacZ reporter gene in transgenic mice [18]. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) uncovered three regions within the Tcp10bt promoter that are specifically bound by testis-derived nuclear proteins [16, 18]. One site in particular, the so-called TBP3 site, contains an AP-2 half-site which the authors’ hypothesize is part of a complex transcription factor binding site in which the AP-2 transcription factor oligomerizes with a testis-specific factor, thus converting the ubiquitously recognized AP-2 site into a testis-specific transcription factor binding site [18]. Two other sites (BP1 and 2) are also bound specifically by a testis-only nuclear factor yet these sites posses no recognizable transcription factor binding sites. Whereas BP2 is within the 973-nucleotide region that governs the proper expression of the reporter gene, BP1 lies outside of this region [16].

In this report, we describe a novel binding site that is found within the promoter regions of the Tctex1 and Tcp10b and c genes, but not Tcp10a. This site, which we call motif A1, is a 20-mer with perfect identity in the two gene families. It is located in the interval between BP2 and BP3 of Tcp10b, a region that does not appear to have been characterized by Ewulonu et al., (1996). We provide evidence for specific binding by a nuclear factor, the approximate half-life of the protein: DNA complex and an approximate binding constant and the relative molecular weight of the protein. In addition, we report on a genome-wide survey of the motif’s prevalence and its proximity to known or novel genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nuclear protein extraction

Brain, liver and testes from adult C3H/HeJ males and the NIH/3T3 cell line were used for isolating a crude nuclear extract using polyethylenimine [19]. Crude nuclear protein pellets were resuspended in storage buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.9, 12.5% glycerol, 1.85 mg mL 1 KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and protease inhibitor cocktail), quantified by Bradford assay, adjusted to 2 μg μL 1, aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until ready to use.

Probe preparation

Lyophilized, complimentary oligonucleotides (IDT, Coralville, IA), corresponding to the 20-mer motif (motif A1) common to Tctex1 and Tcp10, or to mutated versions of the 20-mer motif (motifs A2 and A3), were resuspended to a final concentration of 100 p mole μL 1 in water. Labeling reactions were performed as follows: 400 pmole of each oligonucleotide were mixed and heated to 95°C in an MJ Research PTC100 thermalcycler for 3 minutes, followed by slow cooling to room temperature and incubation on ice for 1 h to allow oligonucleotides to anneal to each other. Afterwards, end-labeling of the double-stranded probe was performed with 10 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK; New England Biolabs) supplemented with PNK buffer and 10 μCi of -32P ATP in a final reaction volume of 20 μL at 37°C for 1 h. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed with the QIAquick nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and probe was eluted from the column with 50 μL of water and stored at −20°C until needed.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

20 μL binding reactions consisting of 5 μL of protein extract (10 μg crude extract), 4 μL of 5X binding buffer (60 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 300 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 1.5 mM EDTA, 50% v/v glycerol), 100 μg BSA, 1 μL labeled probe (20 pmol μL 1; 40,000 counts-per-minute, CPM) and 1 μg poly (dI:dC) non-competitive DNA were incubated with or without unlabeled competitor (motifs A1, A2 or A3; Table 1) at varying excess concentrations (0 to 50-fold) at 30°C for 30 min. Complexes were resolved on 4.75% native polyacrylamide gels (pre-run at 125V for 30 minutes) for 2.5 h at 125V. Gels were transferred onto filter paper, dried under vacuum and placed on X-ray film with intensifying screen at −80°C.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Motif A1 in the mouse genome (NCBI build 34) and its proximity to gene loci

| Chromosome | Genomic contig | Nearest gene | Motif sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NT_039169 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG |

| NT_039170 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATAGAAG | |

| Zfp451 | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGAGA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATAGTA | ||

| Tmeff2 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGGAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AGCAATGAGAAGCAATTGTG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | TTGAATGAGAAGCAATCCTA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATGGCAC | ||

| Crygf | AAGAATGAGAAGCATAGAAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGATA | ||

| NT_078297 | St8sia4 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAACAGT | |

| Hypothetical Locus | GTGCATGAGAAGCAATTCAC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCACGAAGA | ||

| Rnf152 | AAGAATGAGAAGCACTGGTT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CCTCATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| NT_039184 | Rgs2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATACATT | |

| 1700025G04Rik | AAGAATGAGAAGCACTGTAA | ||

| 6530413N01Rik | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGTCA | ||

| NT_039185 | Astn1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAGCA | |

| Pappa2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAATATA | ||

| Scyl1bp1 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAGAT | ||

| Atf6 | AGAGATGAGAAGCAATTCAT | ||

| NT_039186 | Rgs7 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAGCCCC | |

| Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGAAA | ||

| NT_039188 | Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAATGCCC | |

| NT_039189 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAACAA | |

| 2 | NT_039206 | Lamc3 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGGGG |

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGCAT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | TTGAATGAGAAGCAATATGG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAAAATGAGAAGCAATTCCT | ||

| Galnt13 | ATTGTTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| NT_108905 | Tlk1 | AAGGCTGAGAAGCAATTCAT | |

| Nckap1 | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTTGG | ||

| NT_108906 | 6430556C10Rik | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGACTAC | |

| NT_039207 | Fshb | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAACAGC | |

| Rasgrp1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATCATTT | ||

| Galk2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATATTA | ||

| Otor | CATCATGAGAAGCAATTCTC | ||

| A230067G21Rik | AAGAATGAGAAGCATCCCCA | ||

| A | GAGAATGAGAAGCAATCCTA | ||

| Dhx35 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAGTGTG | ||

| Ptprt | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGGAC | ||

| NT_039212 | Cdh26 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAACAGGC | |

| 3 | NT_039230 | Stoml13 | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATTCAG |

| 5330432B20Rik | ATTGTAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Mbnl1 | GATCAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Rap2b | TCCTCTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Gpr149 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATATGAA | ||

| NT_078380 | Hnf4g | AAGAATGAGAAGCACCTGAA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | GAAACAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GTGAATGAGAAGCAATATTT | ||

| Armc1 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAACTTTG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CTACATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| NT_039228 | Hypothetical Locus | TCAAATGAGAAGCAATTATT | |

| NT_039229 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | |

| NT_039234 | B3galt3 | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | |

| Fstl5 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAATCATA | ||

| Lgr7 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAATGTG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATTCTAT | ||

| NT_039240 | St71 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAACGGCT | |

| Hypothetical Locus | GATCTTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Vav3 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAAACA | ||

| Ext12 | CATCCTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Agl | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGACC | ||

| Ndst4 | GAGAATGAGAAGCAATAAAT | ||

| NT_039242 | Hypothetical Locus | ATTGATGAGAAGCAATTCTG | |

| Pdlim5 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAACAAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AGAAAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| 4 | NT_039258 | Penk1 | GGAGATGAGAAGCAATTCCA |

| Hypothetical Locus | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAGCCTA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CACAAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Efcbp1 | CACAATGAGAAGCAATTTTA | ||

| Ripk2 | CCTGGTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| NT_109314 | Epha7 | CTGAATGAGAAGCAATAATT | |

| NT_109315 | Mdn1 | TATAATGAGAAGCAATTTGA | |

| Gabrr1 | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAACTGT | ||

| Ppp3r2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAAGCA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GTCAATGAGAAGCAATTGGT | ||

| NT_039260 | Astn2 | AGCCAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Dbccr1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGCTGGC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAACACAT | ||

| Jmjd2c | GCACATGAGAAGCAATTCTC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTGTTC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAATGG | ||

| Mllt3 | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTTAC | ||

| NT_039280 | Zfp352 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAACTACA | |

| NT_039264 | 2410002M20Rik | AATGAATGAGAAGCAATATT | |

| Zmpste24 | ACCAATGAGAAGCAATTGCA | ||

| NT_109317 | AU040320 | TGGAAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| NT_039267 | Hypothetical Locus | AGGGAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGGCTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Mllt3 | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTTAC | ||

| NT_039280 | Zfp352 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAACTACA | |

| NT_039264 | 2410002M20Rik | AATGAATGAGAAGCAATATT | |

| Zmpste24 | ACCAATGAGAAGCAATTGCA | ||

| NT_109317 | AU040320 | TGGAAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| NT_039267 | Hypothetical Locus | AGGGAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGGCTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| A230053A07Rik | TGGAATGAGAAGCAATTACC | ||

| 5 | NT_039299 | Pftk1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTCAAA |

| Speer3 | CTTCATGAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| Speer3 | CTTCATGAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| Gnail | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AGTAATGAGAAGCAATTACT | ||

| Ptpn12 | TCCTATGAGAAGCAATTCTC | ||

| Prkag2 | TGCAATGAGAAGCAATTTAT | ||

| Paxip1 | CCTCATGAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| NT_039301 | Nrbp | TCACCTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| NT_039305 | Hypothetical Locus | AACTTAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Cpeb2 | GAAAATGAGAAGCAATTGCA | ||

| Gnpda2 | TTACATGAGAAGCAATTCCA | ||

| NT_109320 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATCCAT | |

| AI586015 | AAGAATGAGAAGCACTGTAA | ||

| NT_078458 | Cdv1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAATGCT | |

| NT_039313 | Hypothetical Locus | GTCTGAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| NT_039314 | Hypothetical Locus | GTGAGAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| NT_039316 | Card11 | ACTGAATGAGAAGCAATGCG | |

| NT_039324 | Trrap | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTTGAA | |

| Usp12 | TGTGCTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| A730013O20Rik | TCAGATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Katnal1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATAAGGA | ||

| 6 | NT_039340 | Asns | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGGAGAG |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTGAGT | ||

| Ica1 | TGTAATGAGAAGCAATTGAA | ||

| Foxp2 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAAATAA | ||

| NT_039341 | C130010K08Rik | GTGAGAAGCAATTCATCTGT | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATGGCC | ||

| NT_039343 | Grid2 | ATCACTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | |

| Hypothetical Locus | GTAAATGAGAAGCAATTACT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GAAAATGAGAAGCAATTACT | ||

| NT_094506 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAAAAT | |

| NT_039350 | Suclg1 | GAGAAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAACG | ||

| NT_039353 | Aak1 | GGTGCTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | |

| Abtb1 | CCAGATGAGAAGCAATTCTG | ||

| Cntn6 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAATATT | ||

| NT_094510 | Slc6a13 | GCGAATGAGAAGCAATTTCC | |

| NT_039356 | Klrb1d | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTATG | |

| NT_039359 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | |

| 7 | NT_039385 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG |

| Vlrg6 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATTTAAA | ||

| Vlrg6 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATTTAAA | ||

| NT_109852 | C530028I08Rik | TCGAATGAGAAGCAATGGTG | |

| NT_039413 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | |

| Cebpg | AAGAATGAGAAGCACGTTAA | ||

| 1810022O10Rik | AAAAATGAGAAGCAATTTGG | ||

| NT_081117 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | |

| NT_039428 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATTTAA | |

| Pcsk6 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGCCT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAACAGGA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAATGAGAAGCAATTATC | ||

| NT_039433 | Adamts13 | CTACAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Eftud1 | CACAATGAGAAGCAATTTCA | ||

| 1110001A23Rik | AATAGAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| 1110001A23Rik | GGAGAAGCAATTCAAACATA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGATG | ||

| Neu3 | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| Olfr519 | AAGAATGAGAAGCTATTCTC | ||

| Wdr11 | ATAAGTGAGAAGCAATTCAC | ||

| NT_081167 | Dock1 | GAGAAGCAATTCAAGCACCA | |

| Mki67 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAACAATA | ||

| NT_039436 | Sirt3 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGCAGCA | |

| 8 | NT_039455 | Hypothetical Locus | CATAATGAGAAGCAATTCAT |

| Defb10 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAATTA | ||

| Defb11 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATAATTA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGGATAG | ||

| NT_039460 | Pdgfr1 | ACTGTGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Adam26 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAATGTGA | ||

| Odz3 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGCAG | ||

| NT_078575 | Il15 | ATGAATGAGAAGCAATGTTT | |

| Phkb | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGGCC | ||

| Siah1a | CATCATGAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| D230002A01Rik | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGCCTG | ||

| Got2 | TCCCAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Cdh11 | ACCCAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Slc7a5 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGTTTC | ||

| D130049O21Rik | GCAGAGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| 9 | NT_039472 | Olfr855 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTCATT |

| E130103I17Rik | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATTGAA | ||

| Grik4 | AATAATGAGAAGCAATTAGA | ||

| D630044F24Rik | ATTGTAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| BC033915 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAACGGGG | ||

| NT_039474 | Lrrn6a | TTTAATGAGAAGCAATTTCC | |

| 4921504K03Rik | AACCAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Tln2 | GAATCTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Vps13c | ATGCATGAGAAGCAATTCTC | ||

| Tmod3 | CTCAATGAGAAGCAATTGCA | ||

| NT_039476 | Zic4 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGCTTTC | |

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAATGAGAAGCAACGTAG | ||

| NT_039477 | Ephb1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGATG | |

| Ephb1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGGTG | ||

| 10 | NT_039490 | Akap12 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGATG |

| NT_039491 | Grm1 | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAAAGTA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGGCTTT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATTCATG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGGGTCA | ||

| NT_039492 | Eya4 | ACAAATGAGAAGCAATTTCT | |

| Lama2 | CAAAATGAGAAGCAATTAAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AGCAATGAGAAGCAATTGCT | ||

| Fyn | ATCCTTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Prep | GATATTGAGAAGCAATTCAT | ||

| NT_039494 | Gpx4 | AACACAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTCAT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | ATGAATGAGAAGCAATGTTT | ||

| NT_039495 | Col13a1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTAAGA | |

| Ank3 | CCAAATGAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| 1700049L16Rik | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAAATA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GCCAATGAGAAGCAATTTTA | ||

| NT_039496 | Ankrd24 | ACAAATGAGAAGCAATTGCT | |

| NT_078626 | Slc41a2 | CACAATGAGAAGCAATTTAT | |

| Ckap4 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGCCA | ||

| Cry1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGAAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGATG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGATG | ||

| NT_039500 | Tmem16d | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGGAGGA | |

| Plxnc1 | TAAAATGAGAAGCAATTGCC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CAAAATGAGAAGCAATTAAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGACTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| 4921506J03Rik | TAAAATGAGAAGCAATTACG | ||

| 4921506J03Rik | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTTCC | ||

| NT_039501 | Hypothetical Locus | CTGAATGAGAAGCAATTAGA | |

| NT_081856 | 4930503E24Rik | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGCAGCC | |

| Lrig3 | TATGGGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Myo1a | GTCAATGAGAAGCAATTCCA | ||

| 11 | NT_039515 | Lif | GAGAATGAGAAGCAACCAAA |

| NT_096135 | Hypothetical Locus | CTCAATGAGAAGCAATTAGA | |

| Hspd1 | ACAAATGAGAAGCAATTGAT | ||

| Rnf130 | AAGAATGAGAAGCACATTTT | ||

| Obscn | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAGGG | ||

| Zfp496 | CTGTTGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Myh3 | TTGAATGAGAAGCAATATCC | ||

| Slc13a5 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATCCAGA | ||

| NT_039521 | Ugalt2 | AGAAATGAGAAGCAATTTTC | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATGACT | ||

| NT_039650 | Olfr136 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAAAAAT | |

| NT_039655 | Unc5cl | AAGAATGAGAAGCATGGAAG | |

| NT_039656 | Hypothetical Locus | CCAAATGAGAAGCAATTGGT | |

| Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAACAAT | ||

| NT_039658 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGGCTCC | |

| Alk | AAGAATGAGAAGCATCTTTT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATGGATC | ||

| Mrc2 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAACAACC | ||

| 4933417C16Rik | CAGAACGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| 12 | NT_039548 | AI852640 | TCGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGA |

| Hypothetical Locus | GTCTATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CTGAATGAGAAGCAATAGAG | ||

| Etv1 | AGGAATGAGAAGCAATGAAG | ||

| NT_039551 | Lrfn5 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGCCAG | |

| Lrfn5 | AAGAATGAGAAGCACAGAAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATACTCA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAAAATGAGAAGCAATTTGG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAACAAAT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATTGGCA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGCAC | ||

| Vrk1 | TGGAATGAGAAGCAATGTTC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GAGAATGAGAAGCAACACAT | ||

| Strn | AAGAATGAGAAGCATGGGAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| 13 | NT_039573 | Klf6 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAACCTC |

| NT_039578 | Hecw1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGTTT | |

| Gpr141 | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATATGA | ||

| Elmo1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCACCTATT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | TAGAATGAGAAGCAATAGCT | ||

| Gmds | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGTGG | ||

| NT_110856 | Fars2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAGGG | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATAAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| NT_039580 | Ofcc1 | AGGAATGAGAAGCAACTCAA | |

| Hivep1 | TGTAGTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Phactr1 | CTGAATTAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Ibrdc2 | CAGGTGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| NT_039589 | Hypothetical Locus | TGTAAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Rasa1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAACTTTT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| Edil3 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTTGTC | ||

| Rasgrf2 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAGAT | ||

| NT_039590 | Hypothetical Locus | GTAAATGAGAAGCAATTAGT | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGCAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTCAAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | ATGAATGAGAAGCAATTTAT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAGATGC | ||

| 14 | NT_039606 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTCATT |

| Nrg3 | CATAATGAGAAGCAATTTCC | ||

| Olfr1508 | CCTAATGAGAAGCAATTGAC | ||

| Mipep | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATCTGT | ||

| Mtmr9 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGGGA | ||

| Elp3 | CAGAATGAGAAGCAAAATGG | ||

| Ephx2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGCCAGG | ||

| Gtf2f2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCACAGGGA | ||

| Olfm4 | TAAAATGAGAAGCAATTAAG | ||

| Klhl1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGTGGC | ||

| Klhl1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAAACAC | ||

| NT_039609 | Hypothetical Locus | TCTTGTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Slitrk1 | TTGAATGAGAAGCAATGTGT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAATAAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | TTAAATGAGAAGCAATTCTG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATCAGGC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CTTGGTGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| 15 | NT_039617 | Ghr | TTTGAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA |

| Ptger4 | GCAAATGAGAAGCAATTTCT | ||

| NT_039618 | Cdh6 | AAGAAAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Cdh6 | CAGAATGACAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Cdh6 | TCGCCAGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAGGGAA | ||

| Cdh12 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGGAG | ||

| Dnahc5 | GAGAATGAGAAGCAACCAGA | ||

| Pgcp | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAAGC | ||

| NT_039621 | Rims2 | ACTAATGAGAAGCAATTTCC | |

| Hypothetical Locus | ATTGTGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Trps1 | ACCATGAAGAATGAGAAGCA | ||

| Sntb1 | GAAAATAAGAATGAGAAGCA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGTCTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | GTTATTGAGAAGCAATTCAT | ||

| Upk3a | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGGAG | ||

| 16 | NT_039624 | Kelchl | AAGAATGAGAAGCACTCACA |

| NT_096987 | Fstl1 | AAAAATGAGAAGCAATTCTC | |

| Lsamp | GACAATGAGAAGCAATTTTT | ||

| Alcam | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAAGTGA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCACATTGT | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAACATG | ||

| NT_039625 | Ncam2 | TAGGTGGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Hunk | GAGAATGAGAAGCAAACATT | ||

| NT_039626 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATTCACA | |

| 17 | NT_039636 | Rps6ka2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATTCAA |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATCCAA | ||

| Nox3 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAAACACT | ||

| NT_039641 | Rgmb | AGCAATGAGAAGCAATTAAA | |

| NT_039643 | Hypothetical Locus | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | |

| Zfp51 | GGGAATGAGAAGCAATCAGG | ||

| NT_039649 | Pde9a | TTTAATGAGAAGCAATTAAA | |

| Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCAACGGAC | ||

| C430042M11Rik | TAGAATGAGAAGCAAGAGGA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | TTGAATGAGAAGCAATGTGA | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CAGAAAGAGAAGCAATTCAT | ||

| NT_111596 | Tctex1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | |

| Tcp10b | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| Tcp10c | AAGAATGAGAAGCAATTCAA | ||

| 18 | NT_039674 | 1810057E01Rik | TCAGATGAGAAGCAATTCTT |

| Trim36 | TCAAATGAGAAGCAATTTTC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | CCAAATGAGAAGCAATTTAC | ||

| Slc12a2 | CAAAATGAGAAGCAATTTTA | ||

| Htr4 | ACCAATGAGAAGCAATTAAT | ||

| Ptpn2 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTTGGA | ||

| Rab27b | TTACCTGAGAAGCAATTCAT | ||

| NT_039676 | 4930594M17Rik | GAGAATGAGAAGCAATGGAC | |

| 19 | NT_082868 | D19Ertd703e | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGTGAGC |

| NT_039687 | D930010J01Rik | GGCAATGAGAAGCAATTATT | |

| Cd274 | TAGAATGAGAAGCAATGAGA | ||

| 8430431K14Rik | AGCTATGAGAAGCAATTCTT | ||

| 8430431K14Rik | TGTTTTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| 1810073H04Rik | TGTTTTGAGAAGCAATTCAG | ||

| NT_039692 | Sorcs3 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGAGACA | |

| Adra2a | TAGAATGAGAAGCAATAGGC | ||

| X | NT_039753 | F8 | ATAGATGAGAAGCAATTCAA |

| NT_039706 | Hypothetical Locus | AAGAATGAGAAGCATGAAAA | |

| Fate1 | TGTAGTGAGAAGCAATTCAC | ||

| Hypothetical Locus | TCTGATGAGAAGCAATTCCC | ||

| Dmd | AAGAATGAGAAGCATATGAA | ||

| Dmd | ATTAATGAGAAGCAATTGTT | ||

| Il1rapl1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCATATAAG | ||

| Pet2 | ATTAATGAGAAGCAATTGTT | ||

| Pola1 | AAGAATGAGAAGCAGCTGAA | ||

DNA: Protein complex half-life and binding constant

The complex half-life was measured by a second EMSA assay in which a binding reaction was setup as described above with motif A1, including the addition of 15-fold unlabeled motif A1 as a competitor. Aliquots were removed at varying time points and resolved on a 4.75% native polyacrylamide gel as described above. After drying the gel and exposing it to X-ray film, the location of the complexes were determined by superimposing the autoradiograph onto the dried gel and cutting out the corresponding regions, adding them to scintillation cocktail and counting in a liquid scintillation counter. The data were log transformed, plotted and fitted to a straight line by least squares regression analysis using SigmaPlot 8. The complex half-life was determined from the graph.

An approximate binding constant for the protein:DNA complex was determined by a third EMSA assay in which varying concentrations of cold competitive DNA were added. The complexes were resolved as described above and the resulting Autoradiograph was subject to scanning densitometry. FUJI’s MultiGauge software was used to determine the spot densities. Data was log-transformed and plotted as described above. The binding constant was extrapolated from the graph.

The sequence specificity of the binding site was determined by the use of double stranded oligomers that differed from motif A1 by the introduction of mutations. EMSA analysis with these mutant motifs was carried out as described above.

Determination of the DNA: Protein complex molecular weight

A 20 μL binding reaction was incubated for 30 minutes at 30°C. Afterwards, the droplet was transferred to Parafilm, placed on ice and crosslinked by irradiating at 254 nm for 10 minutes from an 18.4 W light source (corresponding to a total energy of 11 kJ). SDS-PAGE loading buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol was added and the crosslinked complex was boiled for 5 minutes and loaded onto a 9% SDS-PAGE Laemmli gel [20] after which the gel was stained in Coomassie, dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Genome analysis

The occurrence of motif A1 in the mouse genome was determined by BLAST [21] analysis of the mouse genome assembly, build 34 (parameter: e = 10). Motifs were subsequently aligned and a sequence logo was generated to illustrate the consensus sequence [22]. The Tctex1 and Tcp10b promoter sequences are available from NCBI (Accession IDs AC092482 and M84175, respectively).

RESULTS

Genes with similar expression profiles lead naturally to the hypothesis that their transcription is regulated by common mechanisms. Although Tctex1 expression is ubiquitously detected at low levels by RT-PCR and Northern analysis, like Tcp10b, it is abundantly expressed in mouse pachytene spermatocytes. The promoters of both gene complexes have been extensively analyzed, yet to our knowledge a previous inter-promoter comparison for the purpose of uncovering common motifs has not been performed. Searching the 5′ upstream region of the Tctex1 and Tcp10b genes for common motifs, revealed a conserved 20-nucleotide motif of sequence 5′-AAGAATGAGAAGCAATTCAA-3′ in Tcp10b but inverted in Tctex1. We call this sequence element motif A1. A sequence of this length is expected to occur randomly once in 1012 nucleotides, barring any sequence bias or extreme lack of complexity. This led us to hypothesize that it may be a binding site for a nuclear factor that is a component of a gene regulatory system common to both gene complexes, so we investigated its prevalence in the mouse genome by blasting the motif against available genomic sequence at NCBI. The results are shown in Table 1. A total of 355 instances of the motif were found in the vicinity of known genes or hypothetical loci, spread across all autosomes and the X chromosome, but not the Y or the mitochondrial genome. The distance from putative transcription start sites is highly variable, ranging from 0.6 kbp (Tcp10b) to 1.7 Mbp (Cdh6). In many instances, more than one identical copy of the motif was found in the vicinity of a gene (Speer3, Vlrg6, Ephb1), whereas in others the flanking residues had diverged between duplications (1110001A23Rik, 4921506J03Rik, Lrfn5, Klhl1 and Cdh6 (3 occurrences)). The motif was found in either orientation in relation to a gene, something that is characteristic of enhancers and repressors [23–25]. A smaller number of hits were found in regions of the genome that have not been fully characterized (data not shown).

The 355 motif sequences were aligned and the alignment was used to calculate the best motif pattern across all 20 nucleotide sites using WebLogo [22]. As shown in Fig. 1, the greatest sequence conservation resides in nucleotides 4 to 14 of the motif (corresponding to AATGAGAAGCA), whereas the residues flanking this core are not as strongly conserved (sites 2–3 and 15–17) or not conserved at all (sites 1 and 18–20). The motif is found in other genomes, including human (627 instances), rat (267 instances), zebrafish (147 instances), Fugu (500 instances) and Drosophila (165 instances) although a gene-by-gene comparison with mouse was not performed. The additional sequences derived from these genomes indicate that the most important sites within the core are positions 7 to 14, GAGAAGCA. When TRANSFAC [26] was searched using TESS (http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/tess/), no matches to the motif were found, nor was it recognized as a repetitive or simple sequence element by RepeatMasker (http://repeatmasker.org).

Fig. 1.

Motif A1 consensus sequence. All instances of the motif occurring in the mouse genome (Table 1) were analyzed using WebLogo as described in materials and methods

To determine if the motif was specifically recognized by a nuclear factor, we performed an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using radiolabeled motif A1 and testis nuclear protein extract. The results, shown in Fig. 2, are consistent with a specific interaction between the motif and a nuclear factor: a single complex was observed and, more importantly, the protein:DNA complex disappeared after addition of a 50-fold excess cold motif A1, but an excess of cold non-competitive DNA had no effect. Similar results were obtained when liver and brain extracts were substituted for the testis extract; however, extracts derived from ovaries or NIH/3T3 cells failed to form a complex, suggesting that the nuclear factor is not expressed in these tissues (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay. End-labeled motif A1 was incubated with the following: (1) Testicular nuclear extract plus poly (dI:dC) cold non-competitor, (2) Testicular nuclear extract plus 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled motif A1, (3) motif A1 alone

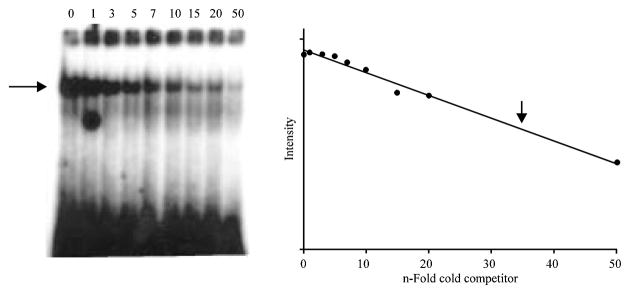

The half-life of the complex was determined in a second EMSA in which a constant amount of cold competitor (15-fold) was added to the binding reaction and the loss of the complex signal was monitored by measuring the complex intensity by scintillation at different time points and plotting this value as a function of time. A drop in complex intensity to half-maximum was observed after 42 minutes in the presence of 15-fold cold competitor, thus indicating that the interaction between the protein and the probe is stable. A third EMSA in which different amounts of cold motif A1 (0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20 and 50-fold) were added, was performed in order to determine how much of the motif was bound per μg of crude protein, which would give a rough indication of the strength and specificity of the protein:DNA complex. Again, the data were fitted to a straight line and an approximate binding constant was calculated as the concentration of probe per μg of crude protein at the point where the complex intensity was half-maximum. The gel and resulting graph are shown in Fig. 3. The binding constant was calculated to be 62 pmol of binding site bound per μg of crude protein (62 pmol μg1).

Fig. 3.

Competition Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay. End-labeled motif A1 was incubated with testicular nuclear extract in the presence of 0-(Lane 1), 1-(Lane 2), 3-(Lane 3), 5-(Lane 4), 7-(Lane 5), 10-(Lane 5), 15-(Lane 6), 20-(Lane 7) or 50-fold (Lane 8) molar excess of unlabeled motif A1. The relative intensity of each complex was determined using MultiGauge (FUJI) and plotted on a semi-log scale versus concentration of cold-competitor using SigmaPlot (v.8). Linear regression was used to find the best-fit straight line through the data (R = 0.95). The arrow above the best-fit straight line is the point at which the intensity is half-maximum (corresponding to approximately 35-fold molar excess of unlabeled motif A1). From this plot, a value of 62 pmol of motif A1 bound per μg of crude nuclear extract was calculated

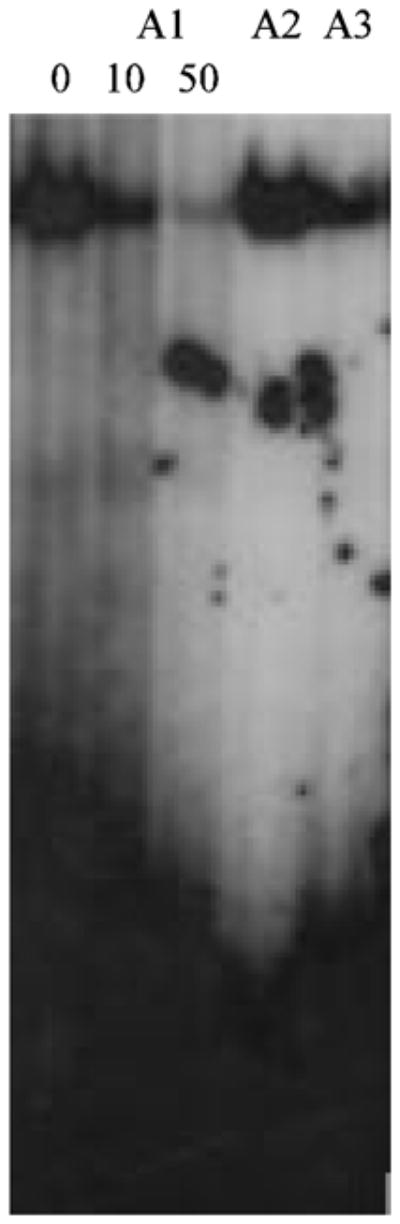

In order to test the computational results suggesting that the specificity of binding resides in residues 4–14 of the motif, we designed two mutant versions of it. Motif A2 had the flanking residues mutated (5′-AGATTTGAGAAGCAAATTAA-3′) whereas motif A3 had mutations in residues 6, 9 and 14 (5′-AAGAAGGAAAAGCGATTCAA-3′). When motif A2 was used to create the complex and subsequently analyzed by EMSA, the intensity of the complex was not significantly different from the complex formed with A1 (Fig. 4). This result is consistent with our earlier finding that these residues are not highly conserved. However, when motif A3 was used a significant drop in complex intensity to approximately one fourth of that observed with motif A1 was noted (Fig. 5), indicating that the specificity of binding resides within the core identified computationally.

Fig. 4.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay with mutant versions of motif A1. End-labeled motif A1 or mutated versions in which the flanking residues (motif A2) or the central residues (motif A3), were incubated as follows: (1) Testicular nuclear extract and poly (dI:dC), (2) Testicular nuclear extract and 10-fold molar excess of unlabeled motif A1, (3) Testicular nuclear extract and 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled motif A1, (4) motif A2 (5′-AGATTTGAGAAGCAAATTAA-3′) and testicular nuclear extract, (5) motif A3 (5′-AAGAAGGAAAAGCGATTCAA-3′) and testicular nuclear extract. Underlined residues differ from those found in motif A1. The relative intensity observed for motif A2 is not measurably different from that observed with motif A1 whereas the intensity observed with motif A3 is approximately one fourth of that observed with motif A1

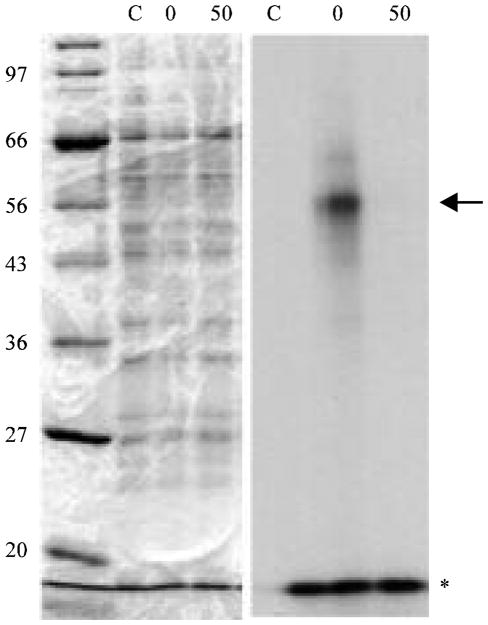

Fig. 5.

UV-crosslinking and SDS-PAGE analysis of the motif A1 complex with nuclear protein. End-labeled motif A1 was incubated with testicular nuclear extract, crosslinked as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed by SDS-PAGE gel. Left panel: Coomassie-stained gel showing molecular weight markers (Lane 1), unirradiated protein:DNA complex assay (Lane 2), UV-crosslinked protein: DNA complex in the absence of competing unlabeled motif A1(Lane 3) and UV-crosslinked protein:DNA complex in the presence of 50-fold molar excess of competing unlabeled motif A1. Right panel: Autoradiography of SDS-PAGE gel from left panel. Lanes are the same; arrowhead shows complex migrating at approximately 55 kDa whereas asterisk shows free end-abeled probe migrating at approximately 12 kDa

Lastly, in order to determine the approximate molecular weight of the nuclear protein that binds to motif A1, we analyzed UV-crosslinked complexes by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5). The results of this experiment show that a DNA: protein complex of approximately 55 kD is formed by UV-crosslinking. Subtracting the molecular weight of the motif (approximately 12 kD) yields an estimated molecular weight of 43 kD for the protein. Once again, the specificity of the interaction was underscored by the absence of a crosslinked complex when the binding reaction was performed in the presence of an 50-fold excess of cold motif A1 (Fig. 5). When an excess of bovine serum albumin was used in place of the nuclear extract, no complex was observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The discovery of novel motifs involved in the regulation of gene transcription is critical to our complete understanding of the mechanisms that govern proper spatial and temporal gene expression. However, this task is made difficult by the size and relative simplicity of these motifs, since they are expected to occur frequently and in regions of the genome bereft of transcriptional activity. One strategy for overcoming this pitfall is to cluster orthologous genes from divergent taxa and search regions upstream of the transcription start site for conserved sequence blocks [27]. Another strategy, employed here, is to examine genes with similar expression profiles and cell-type specificity for shared elements that may be involved in regulating their overlapping expression profiles. The promoter regions of Tctex1 and Tcp10b have been studied individually [2, 16]. Their high levels of expression in pachytene spermatocytes as well as their low (Tctex1) or absent (Tcp10b) expression in other tissues suggested to us that they may be regulated by the same mechanism and the discovery of motif A1 bolstered this hypothesis.

However, our results show that the motif is specifically recognized by a nuclear factor present in several tissues, consistent with the observation that motif A1 is found in genes expressed in a variety of tissues and cell types. It is interesting that NIH/3T3 cells and ovary do not express the protein, indicating that a higher level of complexity in the organization of the tissue (NIH/3T3) or absent signal required for expression of the nuclear factor is not present in NIH/3T3 cells or in ovary. Although we have yet to uncover a link common to all the genes in Table 1, it remains a possibility that they act in concert in an uncharacterized gene network. We anticipate that the kinetics and affinity of the protein for motif A1 will support our findings that the complex is highly stable and probably has a low binding constant, but this awaits purification of the nuclear factor that binds motif A1.

The prevalence of motif A1 in the mouse genome and the variability in its position and orientation relative to the purported transcription start site of nearby genes are suggestive of a role in cis-acting gene regulation, possibly as an enhancer or repressor of expression of genes under the transcriptional control of RNA polymerase II. Its conserved presence in other vertebrate organisms is suggestive of strong evolutionary conservation, particular given the observation that the central region of motif A1, which we show is the core site of recognition (Fig. 4), is highly conserved across taxa (data not shown). The high occurrence of the motif in Fugu is interesting and seems to indicate that a larger number of genes in this organism are under the influence of the motif’s hypothesized effect on gene regulation, than in mice, rats, zebrafish, or Drosophila. If this is the case, it is consistent with the hypothesis that speciation and species differences are largely due to differences in gene expression and not to differences in the genes themselves [28–30].

Other questions remain unresolved, such as the identity of the nuclear factor that binds to motif A1 and how it might interact with the transcription machinery and the effect of motif A1 on the regulation of gene transcription. One possibility, given the proximity of the motif to a large cadre of genes with seemingly unrelated expression profiles and functions, is that the motif is part of a general mechanism used by the cell to either enhance or repress expression based on a number of different external queues; its role in regulation in such a situation could be due to tissue and/or cell-type specific expression of other factors that interact with the protein bound to motif A1. A second possibility, as stated previously, is that the genes where motif A1 is found interact in an uncharacterized network.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Barnes, Mary Ann Handel and Charles Wray for critical comments on the manuscript. A.P. thanks Peter Schlax and Paula Schlax for helpful suggestions on experimental protocols. This work was supported by NIH Grant P20 RR-016463 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources to A.P.

References

- 1.Lader E, Ha HS, O’Neill M, Artzt K, Bennett D. Tctex-1: A candidate gene family for a mouse t complex sterility locus. Cell. 1989;58:969–979. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90948-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill MJ, Artzt K. Identification of a germ-cell-specific transcriptional repressor in the promoter of Tctex-1. Development. 1995;121:561–568. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schimenti J, Cebra-Thomas JA, Decker CL, Islam SD, Pilder SH, Silver LM. A candidate gene family for the mouse t complex responder (Tcr) locus responsible for haploid effects on sperm function. Cell. 1988;55:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullard DC, Schimenti JC. Molecular cloning and genetic mapping of the t complex responder candidate gene family. Genetics. 1990;124:957–966. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.4.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King SM, Dillman JF, Benashski SE, Lye RJ, Patel-King RS, Pfister KK. The mouse t-complex-encoded protein Tctex-1 is a light chain of brain cytoplasmic dynein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32281–32287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison A, Olds-Clarke P, King SM. Identification of the t complex-encoded cytoplasmic dynein light chain tctex1 in inner arm I1 supports the involvement of flagellar dyneins in meiotic drive. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1137–1147. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagami O, Gotoh M, Makino Y, Mohri H, Kamiya R, Ogawa K. A dynein light chain of sea urchin sperm flagella is a homolog of mouse Tctex 1, which is encoded by a gene of the t complex sterility locus. Gene. 1998;211:383–386. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai AW, Chuang JZ, Sung CH. Localization of Tctex-1, a cytoplasmic dynein light chain, to the Golgi apparatus and evidence for dynein complex heterogeneity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19639–19649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tai AW, Chuang JZ, Bode C, Wolfrum U, Sung CH. Rhodopsin’s carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail acts as a membrane receptor for cytoplasmic dynein by binding to the dynein light chain Tctex-1. Cell. 1999;97:877–887. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller S, Cao X, Welker R, Wimmer E. Interaction of the poliovirus receptor CD155 with the dynein light chain Tctex-1 and its implication for poliovirus pathogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7897–7904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyon MF. Transmission ratio distortion in mice. Ann Rev Genet. 2003;37:393–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer H, Willert J, Koschorz B, Herrmann BG. The t complex-encoded GTPase-activating protein Tagap1 acts as a transmission ratio distorter in mice. Nat Genet. 2005;37:969–973. doi: 10.1038/ng1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galliot B, Dolle P, Vigneron M, Featherstone MS, Baron A, Duboule D. The mouse Hox-1.4 gene: primary structure, evidence for promoter activity and expression during development. Development. 1989;107:343–359. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimura Y, Tanaka H, Nozaki M, Yomogida K, Shimamura K, Yasunaga T, Nishimune Y. Genomic analysis of male germ cell-specific actin capping protein alpha. Gene. 237:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somboonthum P, Ohta H, Yamada S, Onishi M, Ike A, Nishimune Y, Nozaki M. cAMP-responsive element in TATA-less core promoter is essential for haploid-specific gene expression in mouse testis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3401–3411. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewulonu UK, Buratynski TJ, Schimenti JC. Functional and molecular characterization of the transcriptional regulatory region of Tcp-10bt, a testes-expressed gene from the t complex responder locus. Development. 1993;117:89–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewulonu UK, Schimenti JC. Function of untranslated regions in the mouse spermatogenesis-specific gene Tcp10 evaluated in transgenic mice. DNA Cell Biol. 16:645–651. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ewulonu UK, Snyder L, Silver LM, Schimenti JC. Promoter mapping of the mouse Tcp-10bt gene in transgenic mice identifies essential male germ cell regulatory sequences. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43:290–297. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199603)43:3<290::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess RR. Use of polyethyleneimine in purification of DNA-binding proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08003-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Hoorn FA. c-mos upstream sequence exhibits species-specific enhancer activity and binds murine-specific nuclear proteins. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:255–266. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell FX, Sax CM, Zehner ZE. A negative element involved in vimentin gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2349–2358. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang-Keck ZY, Kibbe WA, Moye-Rowley WS, Parker CS. The SV40 core sequence functions as a repressor element in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21362–21367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matys V, Fricke E, Geffers R, Gossling E, Haubrock M, Hehl R, Hornischer K, Karas D, Kel AE, Kel-Margoulis OV, Kloos DU, Land S, Lewicki-Potapov B, Michael H, Munch R, Reuter I, Rotert S, Saxel H, Scheer M, Thiele S, Wingender E. TRANSFAC: transcriptional regulation, from patterns to profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:374–378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohler U. Promoter prediction on a genomic scale--the Adh experience. Genome Res. 2000;10:539–542. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental plasticity and the origin of species differences. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2005;102:6543–6549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501844102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikkelsen TS, et al. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Z, Ventura M, She X, Khaitovich P, Graves T, Osoegawa K, Church D, DeJong P, Wilson RK, Paabo S, Rocchi M, Eichler EE. A genome-wide comparison of recent chimpanzee and human segmental duplications. Nature. 2005;437:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature04000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]