Abstract

Two enzymes, α glycerophosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH-1) in the cytoplasm and α glycerophosphate oxidase (GPO-1) in the mitochondrion cooperate in Drosophila flight muscles to generate the ATP needed for muscle contraction. Null mutants for either enzyme cannot fly. Here, we characterize 15 ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS)-induced mutants in GPDH-1 at the molecular level and assess their effects on structural and evolutionarily conserved domains of this enzyme. In addition, we molecularly characterize 3 EMS-induced GPO-1 mutants and excisions of a P element insertion in the GPO-1 gene. The latter represent the best candidate for null or amorphic mutants in this gene.

Keywords: Drosophila, EMS-induced null mutants, excisions, αglycerophosphate cycle

In vertebrate skeletal muscle, glycolysis is maintained by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) produced from the conversion of pyruvate to lactic acid by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The accumulation of lactic acid can eventually result in tetanus. In the Dipteran flight muscle, as well as in other systems, NAD+ is produced by 2 enzymes, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH, EC1.1.1.8) in the cytoplasm and sn-glycerol-3-phosphate oxidoreductase (GPO, EC 1.1.99.5) in the mitochondrion. The enzymes act together in the so called α glycerophosphate (αGP) cycle (Sacktor 1965), GPDH reduces dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) in the process generating NAD+ for the eventual production of pyruvate. The product of this reaction, αGP, crosses the mitochondrial membrane where GPO converts it back to DHAP, which moves back to the cytoplasm, becoming once again a substrate for GPDH (see Figure 1 in Davis and MacIntyre 1988). Because of the αGP cycle and the absence of LDH in the flight muscle, there is no buildup of either αGP or lactic acid. Hence, the insects can fly as long as glycogen is supplied to the muscles via the hemolymph. An additional 4 molecules of ATP along with those derived from pyruvate and the Krebs cycle are generated by the coupling of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation mediated by the αGP cycle.

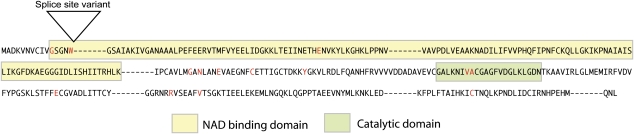

Figure 1.

Positions of the GPDH-1 mutations in the wild-type protein sequence. NAD-binding and catalytic domains are boxed as shown. Mutant sites are indicated in red and the mutant amino acids listed in Table 2. The position of the splice site variant, nsp4, is indicated by a triangle. (This figure appears in color in the online version of Journal of Heredity.)

Not surprisingly, Drosophila melanogaster has become an important model organism for understanding both the genetic control and the metabolic regulation of the αGP cycle. The structural gene for GPDH was mapped on the second chromosome at 26A, using allozyme variants (Grell 1967; O'Brien and MacIntyre 1972) and deletions (Kotarski, Pickert, and MacIntyre 1983). The structural gene for GPO was mapped to 52CD using segmental aneuploidy (O'Brien and Gethmann 1973) and deletions (Davis and MacIntyre 1988). As befitting the key roles of the 2 enzymes in the operation of the αGP cycle, null mutants for either enzyme are unable to fly and exhibit shortened life spans (O'Brien and MacIntyre 1972; O'Brien and Shimada 1974; Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. 1983; Davis and MacIntyre 1988). Hypomorphic GPDH mutants, on the other hand, exhibit varying levels of flight ability as assayed by simple observation or the measurement of wing beat frequencies (Merritt et al. 2006). To date, however, the GPDH and the GPO null or hypomorphic mutants have not been characterized at the molecular level.

Recently, GPDH and specifically its 3 C-terminal amino acids were found to play a key role in the colocalization of 6 glycolytic enzymes, namely aldolase, GPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, triose phosphate isomerase, phosphoglycerate kinase, and phosphoglycerol mutase, in the myofibrils of the flight muscles (Wojtas et al. 1997; Sullivan et al. 2003). These 6 enzymes in transgenic flies expressing an enzymatically active isoform of GPDH but lacking the 3 C-terminal amino acids, glutamine (Q), asparagine (N), and leucine (L), fail to localize to Z and M discs. In addition, these flies cannot fly.

Given our observations that flightless null mutants for either GPDH or GPO generally have no measurable GPDH or GPO enzymatic activity when adult flies are assayed (e.g., see Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. 1983), once the D. melanogaster genome sequence became available, we were surprised to find that there are 3 paralogs for each gene (Ashburner et al. 1999; Adams et al. 2000). Thus, in addition to the GPDH gene at 26A (CG9042) that we have worked on for many years, there are paralogs at 59C (CG3215) and 94A (CG31169). With regard to GPO, in addition to the gene mapped earlier by O'Brien and Gethman (1973) and by Davis and MacIntyre (1988) at 52C8 (CG8256), there are GPO paralogs at 34D (CG7311) and 43D (CG2137). In a companion paper (Carmon and MacIntyre 2009), we will examine the evolutionary histories of the GPDH and the GPO paralogs. We propose to label them as GPDH-1, GPDH-2, and GPDH-3, and as GPO-1, GPO-2, and GPO-3. We will show that only the GPDH gene at 26A (GPDH-1) and the GPO gene at 52C8 (GPO-1) are expressed in the adult flight muscle.

In this paper, we will molecularly identify the lesions in a variety of GPDH-1 and GPO-1 mutants and examine the effects of the mutations on structural domains of each enzyme. Finally, we will quantitatively determine the effects of certain of these mutations on flight ability in light of their molecular lesions.

Materials and Methods

Fly Strains

Strains containing the GPDH-1 and GPO-1 ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS)-induced null mutants (O'Brien and MacIntyre 1972; Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. 1983; Davis and MacIntyre 1988) are either maintained at the Bloomington Stock center or in the MacIntyre laboratory at Cornell University. The mutations are balanced over either In(2LR)CyO or In(2LR) WgGla or simply Gla because of the lethal alleles at other second chromosomal loci generated during the mutagenesis. In order to extract GPDH-1 mutant mRNAs or measure their flight abilities, we outcrossed the mutants to a stock containing Df(2L)clot-7, which removes all the genes between 25D7 and 26A7, including the GPDH-1 locus and analyzed the F1 progeny. Two transgenic stocks, K-7 and K-10 are analyzed in this study for their flight abilities. In each of these stocks, a full-length GPDH-1 cDNA driven by an hsp-70 promoter was inserted into the third chromosome by P element transformation. The second chromosomal background of these stocks is GpdhnSP10/Df(2L) clot-7. GponLT139 and GponPO238 are hypomorphic GPO mutants extracted from 2 natural populations near Ithaca, NY by Sally Constable. Wild males were crossed to a deletion of the GPO-1 gene at 52C8, namely Df(2R)WMG268.12 or WMG kindly supplied by W. Gelbart (see Davis and MacIntyre 1988). F1 flies heterozygous for a wild second chromosome and Df(2R)WMG268.12 were subjected to a GPO specific spot test described in Davis and MacIntyre (1988). If approximately half of the F1s showed low GPO activity, the mutant chromosome was isolated and maintained over the In(2LR)CyO balancer.

We obtained a P element insertion in the 5′untranslated region (UTR) of the GPO-1 gene balanced over In(2LR)CyO. The insertion, P[lac w], is marked with a w+ allele and is viable over Df(2R) WMG268.12. Hence, its recessive lethality is not due to its effect on the GPO gene. This insertion, identified as Gpo-1k05713 in FlyBase, was used to generate imprecise excisions near and/or extending into the GPO-1 gene. Briefly, flies carrying the insertion were crossed to flies carrying the Δ2-3 or wings clipped helper plasmid inserted in a Curly balancer chromosome. Single F1 males with curly wings and the orange eye color of the P[lac w] insert were crossed to w, Cy0, cl-4/Gla females (see Davis and MacIntyre 1988 for a description of CyO, cl-4). Rare white eyed, Gla males were then used to establish stocks homozygous for putative excisions of the insert. DNA flies from these stocks was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described below.

GPDH-1 RT-PCR Analyses

Total RNA was isolated from 1-day-old adult flies for the analysis of the GPDH-1 null mutants; we used the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for these RNA purifications. Primers used for reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR are listed in Table 1. RT reactions were carried out using the Thermoscript system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). First-strand synthesis was initiated from the gene specific Gpdh-1 primer. We used the following PCR conditions: 95 °C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 1 min at 66 °C, 1.5 min at 72 °C; followed by 5 min at 72 °C. Products were cloned into pBluescript after digestion by Bgl1 and Xho1for subsequent sequencing.

Table 1.

Primers used in the analysis of the GPDH-1 and GPO-1 mutants

| Primer name | Primer sequence |

| Gpdh-1 | CTAAGGCAACAACCTATACGATC |

| Gpdh-1_Bgl5 | GAAGATCTATGGCGGATAAAGTAAATGTGTGC |

| Gpdh-1_Xho | TGTCTCGAGAAGATTCATCGAGTTGGCGTTGTG |

| GPO_1F | GGAAATTCACGGAAGAGCAG |

| GPO_1R | GCGCAGCAGCTACTTGTTCT |

| GPO_2F | AAGGATGCTTGTGAAAATTGAA |

| GPO_2R | GCAACAGACTGAATGCGAAA |

| GPO_3F | CGCGGAAAAGTGACTCAAAC |

| GPO_3R | TGTTACGAAGTTGAATAATTAGCTCTG |

| GPO_4F | TGCCAGATTTTATGGTGTTTG |

| GPO_4R | CGTGCATACAGAGGACCTTC |

| GPO_5F | GAGATGACCTCGCGAATGTT |

| GPO_5R | CGTGTAAACTGGCAGCATGA |

| GPO_6F | CATCCCCCATTGTAGAGTGC |

| GPO_6R | GGGCTATAGTAGCCAGGCAGT |

| GPO_7F | GAAGGCCAAGTGCATTGTTA |

| GPO_7R | CAGGCTGCAAATACGTGGAT |

| GPO_8F | TCTAGTGGGCCGGAAATAGA |

| GPO_8R | TCTTTGTCGATCAGCTGGAA |

| GPO_9F | CAGATTAAGCACGCCACTGA |

| GPO_9R | GCGGTCATCTGTGAGTTGAA |

| GPO_10F | GAGCTGGAGGAGCAGAAGC |

| GPO_10R | TTGTGATGTCCACTGCTAACG |

GPO-1 PCR Analysis

Genomic DNA from flies heterozygous for a mutant allele over Df(2R) WMG was extracted from adult males and purified using the Puregene Core Kit A kit (Qiagen). Overlapping primer pairs, shown in Table 1, were used to amplify the mutant alleles using standard PCR conditions. Products were then sequenced. In cases where we failed to obtain amplicons, PCR was performed using SpeedSTAR polymerase using Fast Buffer II (TaKaRa Bio Inc, Madison, WI). Cycling conditions were 94 °C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 98 °C for 5 s, 55 °C for 15 s; 72 °C for 4 min. End sequencing was performed to determine the nature of the insertion. Excision-induced deletions were analyzed by PCR with various combinations of primers shown in Table 1 located near the P element insertion site. Products spanning the deletion site were directly sequenced.

Flight Testing

To exhaust stored ATP, the flies were “exercised” for 5 min in an empty vial on a tilted circular roller at 20 rpm; the flies were released into the device described by Drummond et al. (1991). Flight ability was measured by counting the number of flies that fly up (score of 3), horizontally (score of 2), down (score of 1), or not at all (score of zero). The data were then transformed into a mean score for each genotype using the parenthetical scores above. For example, if out of 100 flies, 50 flew up, 25 horizontally, and 25 flew down, the mean score would be 2.25, ([50 × 3] + [25 × 2] + [25 × 1] divided by 100).

Results

Analysis of GPDH-1 Null Mutants

We extracted RNA from 0- to 1-day-old adults and, using reverse transcriptase and a gene specific primer, amplified DNA from the messages of several null or hypomorphic null mutants made by O'Brien and MacIntyre (1972) and Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. (1983). The cDNAs amplified with GPDH-1 specific primers Bgl5 and Xho8 (see Table 1) were cloned and sequenced; and the changes we identified are listed in Table 2. Their positions in the amino acid sequence of GPDH-1 are shown in Figure 1. All of these mutants were induced with EMS following Lewis and Bacher (1968) and initially detected by starch-gel electrophoresis (O'Brien and MacIntyre 1972) or by an enzymatic “spot test” of single fly homogenates (Kotarski et al. 1983). The mutations, which reduce or eliminate GPDH enzyme activities in both adult and larval flies (Davis and MacIntyre 1988), are located at many different sites in the protein. Only 2 of the missense mutations, however, are in the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-binding domain or the catalytic domain. The latter, ns5 and nsp2 are, in fact, hypomorphs, that is, their protein products retain some enzymatic activity. Surprisingly none of the missense null mutants, that is, n0, n1-4, n5-4, nsp12, and nRZ1 are in either functional domain, although n0, n1-4, and nsp12 are in evolutionarily conserved motifs (see InterPro accession number IPR00077).

Table 2.

Phenotypic data and molecular analysis of the EMS-induced GPDH-1 mutants

| Mutant | Codon/base change | Effect | Codon | % Wild-type enzymatic activitya | Flight abilitya |

| n0 | AAC → ATC | Asn → Ile | 153 | 0 | − |

| n1-4 | GGC → GAC | Gly → Asn | 151 | 0 | − |

| n1-5 | GAG → AAG | Glu → Lys | 60 | 26.1 | + |

| n5-4 | TGC → TAC | Cys → Tyr | 164 | 0 | − |

| ns5 | GTG → ATG | Val → Met | 209 | 56.6 | + |

| ns6 | GGC → AGC | Gly → Ser | 11 | 4.6 | + |

| ns7 | GTG → GAG | Val → Glu | 279 | 52.4 | + |

| nsp2 | GCC → ACC | Ala → Thr | 210 | 4 | + |

| nsp4 | G → A | Splice site variant | 0 | − | |

| nsp6 | TGC → TAC | Cys → Tyr | 330 | 8.3 | + |

| nsp8 | TAT → TAA | Tyr → STOP | 175 | 9.2 | + |

| nsp10 | TGG → TGA | Trp → STOP | 15 | 0 | − |

| nsp12 | GAG → GTG | Glu → Val | 255 | 0 | − |

| nRZ1 | CGC → CTG | Arg → Cys | 273 | 0 | − |

| nGL3 | GAG → AAG | Glu → Lys | 157 | 22.2 | + |

Data from O'Brien and MacIntyre (1972) and Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. 1983.

As expected, the sites in GPDH-1 marked by the null and hypomorphic mutants are either invariant or show only conservative substitutions in the comparisons of the GPDH-1 orthologs from the 12 Drosophila species whose genomes have been sequenced and in the other 2 paralogs in D. melanogaster. In the comparisons of the paralogs, the invariant sites marked by GPDH-1 mutations are Gly-11, Ala-210, Glu-255, Val-279, and Cys-330 (Carmon and MacIntyre 2009). Two other mutants are noteworthy. First, nsp10, which earlier had been shown “not” to make a protein recognized by antibodies against wild-type GPDH-1 either on the basis of an I125 based assay (Kotarski et al. 1983) or on western blots (Sullivan D, personal communication), is a nonsense mutant that undoubtedly terminates translation at codon 15. Second, nsp4, which fails to make an enzymatically active protein or even an inactive protein as determined by western blots, is due to a G → A transition at the donor splice site in the first intron in the gene.

Analysis of GPO-1 Mutants

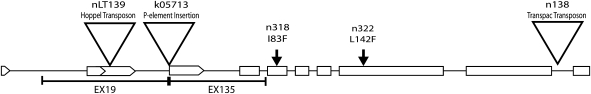

Davis and MacIntyre (1988) generated the first 2 EMS-induced null mutants of GPO-1. Subsequently Sally Constable (unpublished) made several more mutants including n138. These were detected by performing enzymatic spot tests as described in Davis and MacIntyre (1988) on individual Df(2R)WMG/null heterozygotes. She also extracted second chromosomes from natural populations near Ithaca, NY and subjected them to spot tests as heterozygotes over Df(2R)WMG as described in Materials and Methods. One chromosome apparently carries a low-activity GPO-1 variant and is designated GPO-1nLT139. We also obtained a stock with a P element inserted in CG8256 (GPO-1) and determined that the insert (k05713) while viable over Df(2R)WMG exhibits no detectable αGPO activity in adults. We extracted DNA from EMS-induced null mutants, n318, n322, and n138, the low-activity variant nLT139, and the P element insertion, k05713, each over Df(2R)WMG. Using overlapping primer pairs located across the GPO-1 gene (see Table 1), we generated and sequenced amplicons for n318 and n322. In the other mutants, certain primer pairs failed to generate amplicons. Here, we used a long-range polymerase and were able to detect larger products indicating the presence of an insertion. We then sequenced the ends of these larger products to identify the inserted elements.

Our results from these analyses are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. Two of the EMS null mutants, n318 and n322, are missense substitutions. Both are at invariant sites in the gene from all 12 sequenced Drosophila genomes and other insect GPO-1s that have been sequenced as well (viz. Anopheles, Aedes, Triboleum, and Apis). Interestingly, the leucine at position 201, marked by the L → F substitution in n322, is also found in both the GPO-2 and the GPO-3 paralogs. The isoleucine at position 109, substituted by phenylalanine in n318, is also found in one GPO paralog, whereas the other has a leucine at site 109, an evolutionarily conservative difference. Curiously, n138 that came out of a screen for EMS-induced null mutants contains a transpac element in the sixth intron separating 2 constitutive exons near the C terminus of the protein. The insertion, which presumably affects splicing of the pre-mRNA, may have preexisted in the stock used for the mutagenesis (see Figure 4 in Davis and MacIntyre 1988) or arose during the crosses carried out during the screen for new mutants. On the other hand, the Hoppel element in nLT139, presumably was present in the 5′UTR in the natural population (Little Tree Orchard near Ithaca, NY) before the second chromosome was extracted and tested over Df(2R)WMG. The GPO enzyme activities of the naturally occurring mutants, nLT139 and nPO238, are high relative to the EMS-induced mutants. It may be that after the mutations occurred, modifiers presumably abundant in the natural populations were selected to increase enzymatic activity and flight ability.

Table 3.

EMS induced and insertional mutants of GPO-1

| Enzyme activitya | Genotype | Lesion | |

| Wild type | 0.31 | +/+ | None |

| Gla/k05713 | 0.17 | +/Insertion | P element insertion in 5′UTR |

| Gla/Df(2R)WMG | 0.15 | +/Deficiency | Deletion |

| k05713/Df(2R)WMG | 0.00 | Insertion/deficiency | P element insertion/deletion |

| n318/Df(2R)WMG | 0.05 | EMS mutant/deficiency | I83F |

| n138/Df(2R)WMG | 0.03 | EMS mutant/deficiency | Transpac element in intron 6 |

| n322/k05713 | 0.05 | EMS mutant/insertion | L142F |

| nLT139/Df(2R)WMG | 0.20 | Natural mutant/deficiency | Hoppel element in 5′UTR |

| nPO238/Df(2R)WMG | 0.19 | Natural mutant/deficiency | Unknown |

Assayed as single flies, units are GPO activity/min/fly. A minimum of 5 individuals were analyzed to obtain each mean value. See Davis and MacIntyre 1988 for assay methods.

Figure 2.

Positions of the EMS-induced mutants (down arrow), insertions (triangle), and imprecise excisions (bar) in the GPO-1 gene. Constitutive exons are shown as open boxes and 5′UTR regions with alternative transcriptional start sites as arrowed boxes.

Our analysis of the P element insertion k05713 confirmed the site of its insertion in the 5′UTR at bp544. Using the crosses outlined above in Materials and Methods, we generated over 150 lines in which all or part of the P element construct was excised. Using primers flanking the insertion site, we screened some 101 lines by PCR for both precise and imprecise excisions of the P [lac w] element. Most precise or partial excisions of the P element construct are viable over Df(2R) WMG. The 5 we found to be lethal over Df(2R)WMG are presumably so called “hit and run” excision events where the element (or part of the element) “hops” locally and perhaps transiently into another gene as part of the excision process. Two excisions, EX 19 and EX 135, removed DNA flanking the insertion site with one end of the deletion exactly at that site (see Sudi et al. 2008). The deletion in EX 19 is upstream of the insertion site and is 977 bases in length. It removes 2 of the 4 alternative transcriptional start sites in the 5′UTR of GPO-1. EX 135, 797 bases in length, extends from the insertion site downstream into the coding region and removes the first constitutive exon that precedes the putative mitochondrial import sequence in exon 2. Presumably, like the strain carrying the insertion itself, k05713, EX 19, and EX 135 should be “good” null mutants of GPO-1 completely lacking enzymatic activity.

Flight Abilities of Molecularly Characterized GPDH-1 and GPO-1 Mutants

Many studies have demonstrated a correlation between flight performance and the enzyme activities of the 2 components of the αGP cycle (Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. 1983; Davis and MacIntyre 1988). Flight ability is also correlated with metabolic activity (Clark 1989; Merritt et al. 2006) and longevity (O'Brien and Shimada 1974; Graves et al. 1988). Flight ability can be measured directly by observation (e.g., see Kotarski et al. 1983; Homyk and Emerson 1988) or indirectly by measuring wing beat frequencies generally involving tethered flies (e.g., see Curtsinger and Laurie-Ahlberg 1981; Graves et al. 1988; Merritt et al. 2006). The latter methods are impractical if large numbers of flies need to be analyzed. For this reason, we chose to use the simple method devised by Drummond et al. (1991) whereby populations of flies can be observed and the data can be transformed for comparative purposes (see Materials and Methods). A second reason for scoring the flight abilities of large numbers of flies is that, even in laboratory stocks of mutants, there is selection for better flying ability and wing beat frequencies, the latter being instrumental in the mating process. Hence, genetic modifiers almost certainly arise in mutant stocks maintained in the laboratory for various periods of time (for a dramatic example, see O'Brien and Shimada 1974). Thus, in these cases, the measurement of flight ability of a small number of individuals could be misleading.

Table 4 presents the raw data and the transformed scores for flies with different levels of either GPDH-1 or GPO-1 enzyme activities. For GPDH-1 we first compared flies with a nsp10 mutation over a wild-type allele on the In(2LR)Gla chromosome versus a chromosome with a deletion of the gpdh-1 gene, Df(2L)clot-7. There is a substantial difference, as shown in the numbers of flies in the “up” and “down” categories. The transformed scores indicate there is more than a 2-fold difference in flight ability. When flies carrying a wild-type GPDH-1 cDNA in a nsp10/Df(2L)clot-7 background are tested, flight ability is improved, but apparently not to the level of the Gla/nsp10 heterozygotes. This may be due to chromosomal position effects on the cDNA transgenes. We also found that heat shocking these flies at several different stages of the life cycle did not affect their flight abilities (data not shown).

Table 4.

Results of flight tests of GPDH-1 and GPO-1 mutants using the device described by Drummond et al. (1991)

| Up | Horizontal | Down | Null | Sum of scores | Transformed scores | |

| Genotype (GPDH) | ||||||

| Gla/nsp10, n = 108 | 204 | 66 | 3 | 0 | 273 | 2.53 |

| nsp10/Df(2L)clot-7, n = 85 | 3 | 54 | 47 | 0 | 104 | 1.22 |

| K-10a, n = 70 | 75 | 48 | 21 | 0 | 144 | 2.06 |

| K-7a, n = 84 | 141 | 44 | 13 | 0 | 198 | 2.36 |

| Genotype (GPO) | ||||||

| Gla/k05713, n = 39 | 66 | 22 | 6 | 0 | 94 | 2.41 |

| k05713/Df(2R)WMG, n = 99 | 3 | 14 | 63 | 0 | 80 | 0.81 |

| n318/Df(2R)WMG, n = 54 | 0 | 8 | 42 | 0 | 50 | 0.93 |

| n138/Df(2R)WMG, n = 89 | 3 | 10 | 48 | 0 | 61 | 0.69 |

| nLT139/Df(2R)WMG, n = 61 | 72 | 20 | 21 | 0 | 113 | 1.85 |

| nPO238/Df(2R)WMG, n = 51 | 45 | 34 | 15 | 0 | 94 | 1.84 |

| n322/k05713, n = 38 | 12 | 22 | 22 | 0 | 56 | 1.47 |

K-10 and K-7 are nsp10/Df(2L)clot-7; Gpdh cDNA insertion/In(3LR)Ubx130.

With regard to GPO-1, the difference between the wild-type heterozygotes (Gla/k05713) and null (k05713/Df(2R)WMG) controls is even more dramatic than in the case with GPDH-1. Again, this can be seen especially in the numbers of flies in the “up” and “null” categories and in the 3-fold difference in the transformed scores. For the mutants, n318, n322, n138, and nLT139 over Df(2R)WMG, there is a good correlation between their GPO enzyme activities, as shown in Table 3 and their flight abilities as shown in Table 4 (r = +0.88). Clearly, however, additional hypomorphic GPO-1 mutants need to be tested to more critically examine this correlation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the mutants listed in Tables 2 and 3 are the first Drosophila GPDH and GPO mutations to be characterized at the molecular level. Their exact effects on the structures of the 2 enzymes will be determined in the near future. With regard to GPDH, 2 mutations, ns6 and n1-5 affect the NAD+-binding site and 2, ns5 and nsp2 substitute amino acids in the catalytic domain. Eight other missense mutants are either in the region between the catalytic and NAD+-binding domains or in the C terminal third of the protein distal to the catalytic domain. Mutant nsp4 is a G → A transition at a splice site and is flightless. Mutagen-induced suppressors of this mutant, selected on the basis of their ability to fly, might well identify genes encoding components of the spliceosome or proteins that enhance or repress the splicing process. Finally, nsp10, a nonsense mutation in codon 15 appears to be a true null or amorphic mutant. Not surprisingly, nsp10/Df(2L)clot-7 heterozygotes have no GPDH enzyme activity and are unable to fly (Kotarski, Pickert, Leonard, et al. 1983).

For GPO-1, we molecularly characterized only 3 EMS-induced mutants, n318, n322, and n138. None of these mutants affect an identifiable functional domain, although n318 and n322 are at amino acid sites completely conserved in insects, and are either at an invariant site (codon 201) or a conserved site (109) in the 3 GPO paralogs. Mutant n138 is associated with the insertion of a transpac element in the last intron in the gene. With regard to GPO-1, the best candidate for a null or amorphic mutant is EX 135 generated by mobilizing the P element construct k05713. This excision removes the first constitutive exon of the gene, whereas the k05713 insertion itself, although it appears to exhibit no GPO activity over Df(2R)WMG, does have an intact coding region.

Finally, we were curious whether the maintenance of the GPDH-1 and GPO-1 mutants in the laboratory, generally, as balanced lethal stocks for many generations, might affect the relationship between GPDH-1 and GPO-1 enzyme activity levels and flight ability. Two opposing forces might well affect the relationships. First is the selective buildup of modifiers of flight ability due to selection for better male courtship that involves the use of flight muscles for wing vibration. Counteracting this selection might be the anecdotally well-known increase in “docility,” that is, less active flight behavior of laboratory stocks of D. melanogaster (Khondrashov A, personal communication). Our use of the simple apparatus of Drummond et al. (1991), which measures the flight ability of populations of flies, strongly indicates the positive correlation between the enzymatic activity of the 2 components of the αGP cycle and flight ability has held up in the stocks of GPDH-1 and GPO-1 mutants. One would expect, as more mutants are tested, this correlation, previously and elegantly shown by Merritt et al. (2006) for GPDH-1, will be further refined.

Funding

Institute of Arthritis and Muscoloskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health (AR 44534).

References

- Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287(5461):2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Misra S, Roote J, Lewis SE, Blazej R, Davis T, Doyle C, Galle R, George R, Harris N, et al. An exploration of the sequence of a 2.9-Mb region of the genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;153:179–219. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon A, MacIntyre R. The α glycerophosphate cycle in Drosophila melanogaster VI. Structure and evolution of enzyme paralogs in the genus Drosophila. J. Hered. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp111. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG. Causes and consequences of variation in energy storage in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1989;123:131–144. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtsinger JW, Laurie-Ahlberg CC. Genetic variability of flight metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Characterization of power output during tethered flight. Genetics. 1981;98:549–564. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.3.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MB, MacIntyre RJ. A genetic analysis of the α-glycerophosphate oxidase locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;120:755–766. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DR, Hennessey ES, Sparrow JC. Characterisation of missense mutations in the Act88F gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:70–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00273589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves JL, Luckinbill LS, Nichols A. Flight duration and wing beat frequency in long- and short-lived Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol. 1988;34(11):1021–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Grell EH. Electrophoretic variants of α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 1967;158:1319–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3806.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homyk T, Jr, Emerson CP., Jr Functional interactions between unlinked muscle genes within haploinsufficient regions of the Drosophila genome. Genetics. 1988;119:105–121. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotarski MA, Pickert S, Leonard DA, LaRosa GS, MacIntyre RJ. The characterization of the α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1983;105:387–407. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotarski MA, Pickert S, MacIntyre RJ. A cytogenetic analysis of the chromosomal region surrounding the α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1983;105:371–386. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E, Bacher F. Method of feeding ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS) to Drosophila males. Drosoph Inf Serv. 1968;43:193. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt TJS, Sezgin E, Zhu C-T, Eanes WF. Triglyceride pools, flight and activity variation at the Gpdh locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2006;172:293–304. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien SJ, Gethmann RC. Segmental aneuploidy as a probe for structural genes in Drosophila: mitochondrial membrane enzymes. Genetics. 1973;75:155–167. doi: 10.1093/genetics/75.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien SJ, MacIntyre RJ. The α-glycerophosphate cycle in Drosophila melanogaster II. Genetic aspects. Genetics. 1972;71:127–138. doi: 10.1093/genetics/71.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien SJ, Shimada Y. The α-glycerophosphate cycle in Drosophila melanogaster IV. Metabolic, ultrastructural, and adaptive consequences of α Gpdh-1 “null” mutations. J Cell Biol. 1974;63:864–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.63.3.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor B. Energetics and respiratory metabolism of muscular contraction. In: Rockstein M, editor. Physiology of insecta. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 483–580. [Google Scholar]

- Sudi J, Zhang S, Intrieri G, Hao X, Zhang P. Coincidence of P-insertion sites and breakpoints of deletions induced by activating P elements Drosophila. Genetics. 2008;179:227–235. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DT, MacIntyre R, Fuda N, Fiori J, Barrilla J, Ramizel L. Analysis of glycolytic enzyme co-localization in Drosophila flight muscle. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:2031–2038. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtas K, Slepecky N, von Kalm L, Sullivan D. Flight muscle function in Drosophila requires co-localization of glycolytic enzymes. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1665–1675. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]