Abstract

To identify evolutionarily conserved features of replication timing and their relationship to epigenetic properties, we profiled replication timing genome-wide in four human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines, hESC-derived neural precursor cells (NPCs), lymphoblastoid cells, and two human induced pluripotent stem cell lines (hiPSCs), and compared them with related mouse cell types. Results confirm the conservation of coordinately replicated megabase-sized “replication domains” punctuated by origin-suppressed regions. Differentiation-induced replication timing changes in both species occur in 400- to 800-kb units and are similarly coordinated with transcription changes. A surprising degree of cell-type-specific conservation in replication timing was observed across regions of conserved synteny, despite considerable species variation in the alignment of replication timing to isochore GC/LINE-1 content. Notably, hESC replication timing profiles were significantly more aligned to mouse epiblast-derived stem cells (mEpiSCs) than to mouse ESCs. Comparison with epigenetic marks revealed a signature of chromatin modifications at the boundaries of early replicating domains and a remarkably strong link between replication timing and spatial proximity of chromatin as measured by Hi-C analysis. Thus, early and late initiation of replication occurs in spatially separate nuclear compartments, but rarely within the intervening chromatin. Moreover, cell-type-specific conservation of the replication program implies conserved developmental changes in spatial organization of chromatin. Together, our results reveal evolutionarily conserved aspects of developmentally regulated replication programs in mammals, demonstrate the power of replication profiling to distinguish closely related cell types, and strongly support the hypothesis that replication timing domains are spatially compartmentalized structural and functional units of three-dimensional chromosomal architecture.

DNA replication in higher eukaryotes is regulated at the level of large domains that replicate in a defined temporal sequence. While the significance of this temporal program is unclear, replication timing is established during early G1 phase, coincident with reduced mobility and repositioning of chromosomal domains in the nucleus after mitosis (Dimitrova and Gilbert 1999; Li et al. 2001), suggesting a link between replication timing and the three-dimensional (3D) organization of chromatin. Consistent with this hypothesis, early and late replication take place in spatially distinct compartments of the nucleus (Gilbert and Gasser 2006), and changes in replication timing (RT) during development are associated with changes in subnuclear chromatin organization (Zhou et al. 2002; Arney and Fisher 2004; Williams et al. 2006; Hiratani et al. 2008, 2010). A strong positive correlation between early replication and transcriptional activity has been found in all multicellular organisms, and differences in replication timing often correspond to differences in transcriptional activity (Hiratani and Gilbert 2009; Hiratani et al. 2009). However, changes in replication timing neither are directly influenced by nor have a direct influence on transcription (Gilbert 2002; MacAlpine and Bell 2005; Gilbert and Gasser 2006; Hiratani et al. 2008; Farkash-Amar and Simon 2009; Schwaiger et al. 2009), suggesting that replication timing is indirectly related to transcriptional competence through the assembly of higher-order chromosome structures. For example, silencing of transcription on the inactive X chromosome is initially reversible, but is stabilized in the epiblast coincident with a nearly chromosome-wide change in replication timing and formation of a recognizable higher-order chromosome configuration within the nucleus, the Barr body (Takagi et al. 1982; Wutz and Jaenisch 2000; Gilbert 2002).

We recently reported genome-wide studies of replication timing in cell culture models of mouse embryogenesis (Hiratani et al. 2008, 2010). These studies revealed that replication timing changes are extensive and take place coordinately across chromosomal units of 400–800 kb. Early to late (EtoL) replication timing changes were associated with down-regulation of mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC)-specific genes and largely preceded late to early (LtoE) changes associated with germ-layer–specific transcriptional activation. Similar to X inactivation, many EtoL changes on individual autosomal replication domains occurred in the epiblast and coincided with changes in subnuclear position and a subsequent inability to reprogram transcription (Hiratani et al. 2010). Pluripotent stem cells derived from mouse epiblasts (EpiSCs) only a few cell cycles after the ESC stage had already completed most EtoL changes, while most LtoE were uninitiated, revealing a clear epigenetic distinction between these closely related pluripotent cell types. Interestingly, EtoL domains were enriched for genes that were difficult to reprogram back to the ESC-like state (Hiratani et al. 2010). Together, these results suggested that replication timing profiles identify megabase-sized domains of stable repression during differentiation.

To identify evolutionarily conserved aspects of this developmentally regulated replication timing program and its relationship to other epigenetic marks in mouse and human cell types, we constructed genome-wide replication profiles for human ESC (hESC) cell lines BG01, BG02, H7, and H9, BG01-derived human neural precursor cells (hNPCs), human lymphoblastoid cells, and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). We demonstrate that, as with mESCs, replication timing profiles are stable and conserved between several hESC lines, but are dramatically reorganized upon differentiation to hNPCs and in lymphoblastoid cells. Human and mouse replication profiles are well conserved within regions of conserved synteny, and significant differences between hESC and mESC profiles provide clear genome-wide confirmation of the EpiSC nature of hESCs. We also identify a novel signature of histone marks flanking the boundaries of replication domains and a striking cell-type-specific correlation of replication timing profiles with genome-wide chromatin interaction maps (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009), strongly supporting the hypothesis that replication domains delineate spatially separated structural and functional units of chromosomes.

Results

Structure of replication domains in human vs. mouse pluripotent stem cells

Genome-wide replication timing profiles were generated using a previously described method (Hiratani et al. 2008). Briefly, cells were pulse-labeled with 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) and separated into early and late S-phase populations by flow cytometry. BrdU-substituted nascent DNA from these populations was immunoprecipitated, differentially labeled, and cohybridized to a high-density whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray (NimbleGen HD2; 2.1 million probes, one probe per 1.1 kb). This produces a “replication timing ratio” [=Log2(Early/Late)] for each probe (gray points in Fig. 1A). Microarray validation was performed by evaluating segments of known replication timing prior to labeling for microarray hybridization (Supplemental Fig. S1). Since adjacent probes replicate almost simultaneously, the quality of individual replicate hybridizations can be evaluated statistically by the similarity of adjacent probes (autocorrelation function, ACF) (Supplemental Fig. S2), and rare low-quality data sets can be eliminated. Biological replicates routinely show high correlation (Supplemental Fig. S3), and profiles are consistent with those created at higher probe density (Hiratani et al. 2008) or by deep sequencing of similarly prepared BrdU-labeled nascent strands (Supplemental Fig. S4; Hansen et al. 2010), allowing comprehensive genome-wide analyses to be rapidly and inexpensively performed on a single oligonucleotide chip. All data sets generated in this study are freely available to view or download at http://www.replicationdomain.org (Weddington et al. 2008).

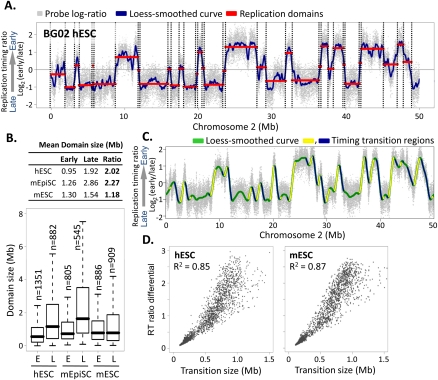

Figure 1.

Structure and conservation of replication domains in hESCs. (A) Replication timing profile across a 50-Mb segment of human chromosome 2. Data shown are the average of two replicate hybridizations (dye-swap) for hESC line BG02. DNA synthesized early vs. late during S phase was hybridized to an oligonucleotide microarray, and the log2 ratio of early/late signal for each probe (probe spacing 1.1 kb) across the genome was plotted on the y-axis vs. map position on the x-axis. (Gray dots) Raw data. (Blue line) Loess-smoothed data. Replication domains (red lines) and boundaries (dotted lines) were identified by circular binary segmentation (Venkatraman and Olshen 2007). (B) Table (top) and box plots (bottom) of the sizes of early (RT > 0) vs. late (RT < 0) replication domains in hESCs (BG02), mESCs (D3), and mEpiSCs, with the ratio of late to early domain sizes. Horizontal bars for each box plot represent the 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, and 90th percentiles. (C) Identification of timing transition regions (TTRs; blue and yellow highlight alternating TTRs) from loess-smoothed RT profiles. (Green) BG02 hESC. (D) Analysis of replication timing differential vs. physical distance for TTRs >100 kb in BG02 hESCs and D3 mESCs.

Figure 1A shows a typical replication timing profile for a segment of chromosome 2 in hESC line BG02. The average of two replicate (dye-swap) data sets was resolved into a replication profile using loess smoothing (blue line), and a segmentation algorithm (Venkatraman and Olshen 2007) was applied to identify regions of similar replication time, which we refer to as “replication domains” (red lines in Fig. 1A). Overall, profiles resemble those in mouse cells (Hiratani et al. 2008, 2010), with domain sizes ranging from a few hundred kilobases to several megabases. However, unlike mESCs, in which early and late domains are similar sizes (Hiratani et al. 2008), hESC late domains were significantly larger and less numerous than early domains (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, this feature instead resembles the sizes of replication domains seen with profiles of the more mature mouse EpiSCs (Fig. 1B; Hiratani et al. 2010), providing the first of several indications that hESC replication timing profiles are more closely related to mEpiSCs than mESCs.

The temporal transitions between replication domains in mouse are consistent with large originless regions where single unidirectional forks emanate from either side of an earlier replicating domain until they encounter forks from later replicating domains (Farkash-Amar et al. 2008; Hiratani et al. 2008; Guan et al. 2009). Indeed, a timing transition region (TTR) at the mouse Igh locus was recently shown to suppress the firing of ectopically inserted origins (Guan et al. 2009). We compared the slopes (number of kilobases separating differentially replicating domains vs. their relative temporal separation) of these TTRs genome-wide in mESCs vs. hESCs (Fig. 1C). In both species, temporal transitions were directly proportional to distance traveled (R2 = 0.85 in hESCs and 0.87 in mESCs) (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that large (up to 1.5-Mb) segments of DNA separating early and late replication domains lack replication origin activity in both mouse and human cells. Since individual transition regions were found to be especially prone to rearrangement (Watanabe et al. 2004), replication timing profiles may highlight cell-type-specific damage-prone genomic regions.

Features of developmental regulation of replication timing

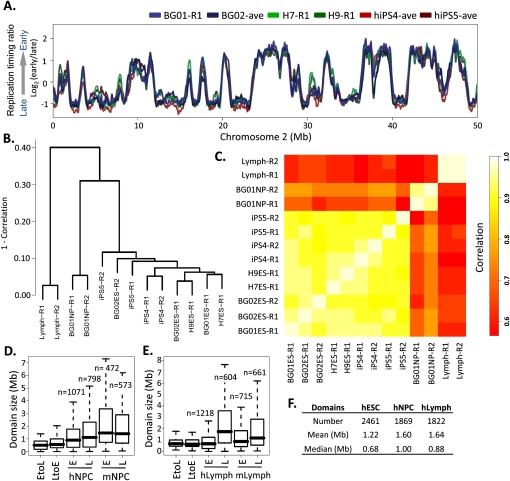

To evaluate whether the replication profile in hESCs is characteristic of the hESC state, we profiled three additional hESC and two independently reprogrammed hiPSC lines. Results revealed a significant conservation and stability of domain boundaries between these highly polymorphic cell lines representing pluripotent human cell types (Fig. 2A). We next determined the extent to which the profile of hESCs and hiPSCs changes during development by profiling BG01 hESCs differentiated to neural precursor cells (hNPCs) in a defined medium (Schulz et al. 2004), as well as C0202 lymphoblastoid cells previously profiled at 1-Mb probe spacing (Woodfine et al. 2004). To compare cell types, we expressed replication profiles as numeric vectors of 12,640 average replication timing ratios for nonoverlapping 200-kb windows across the genome. Both hierarchical clustering (Fig. 2B) and correlation matrix analyses (Fig. 2C) of these windows verified the close similarity of individual hESC and hiPSC replicate profiles and significant differences between hESC, hNPC, and lymphoblastoid profiles, with changes in replication timing involving more than one-third of the genome, as was observed in mouse (Hiratani et al. 2010). Interestingly, the size distributions of both EtoL and LtoE switching domains for both NPCs and lymphoblasts were similar and considerably smaller than global replication domains (Fig. 2D,E), but consistent with the sizes of EtoL and LtoE switching domains in mouse (Hiratani et al. 2008). This suggests that a basic unit of replication timing change is conserved from mouse to humans, and is on the order of 400–800 kb. Also consistent with mESC differentiation to either NPCs or lymphoblasts, many switching domains changed their replication timing to match adjacent domains (“domain consolidation”) (Supplemental Figs. S5–S7), resulting in a decrease in the number of domains from ESCs (2461) to NPCs (1869) or lymphoblastoid cells (1822) and a corresponding increase in domain size (Fig. 2F). The degree of early domain consolidation was higher for NPCs vs. lymphoblasts in both species, revealing a conserved developmental specificity of domain sizes (cf. Fig. 1B and Fig. 2D–F).

Figure 2.

Cell-state specificity of replication profiles. (A) Conservation of replication timing among cell lines BG01, BG02, and H7 shown by loess-smoothed replication profiles generated as in Figure 1. Genome-wide, pairwise Pearson R2 values can be found in Supplemental Figure S3D. (B) Hierarchical clustering of individual RT profile replicates in 12,640 200-kb windows. The height of horizontal bars depicts the relative similarity between clusters, with more similar clusters lower on the graph. (R1) Replicate 1, (R2) replicate 2. (C) Correlation matrix of hESC, hiPSC, hNPC, and lymphoblast replicate profiles averaged in 200-kb windows as in B. Heat map (right) provides a gauge of the relative similarities of data sets to each other. (D,E). Size distribution of EtoL and LtoE switching domains and early vs. late domains in human vs. mouse NPCs (G) and lymphoblasts (H), calculated as in Figure 1B. Data for mNPCs are from Hiratani et al. (2008). (F) Summary of domain numbers and sizes.

To examine the relationships between replication timing and transcription, microarray transcriptional analyses were performed in hESCs and hNPCs (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Fig. S8). We found a significant positive relationship between early replication and transcription across 19,991 RefSeq genes, which resembled that found previously in Drosophila (Schubeler et al. 2002; Schwaiger et al. 2009) and mouse (Hiratani et al. 2008, 2010). Coordination of changes in transcription and replication timing upon differentiation to hNPCs was also reminiscent of that in mouse (Supplemental Fig. S8), and similar results were recently reported in human cells (Desprat et al. 2009). Examination of four classes of genes by expression and replication timing revealed that some chromatin marks (H3K4me3, H3K9Ac, H3K27Ac, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3) were more closely associated with transcript levels than replication timing at individual promoters, while sequence properties such as GC and LINE-1 content had a stronger relationship to replication timing (Supplemental Fig. S9). Altogether, we conclude that the general structure and organization of replication timing domains and their coordination with transcription are conserved between mouse and human.

Evolutionary conservation of cell-type-specific replication timing profiles

The availability of genome-wide replication timing maps for mouse and human cell types provided the opportunity to evaluate conservation of the replication program. When we first examined several large regions of conserved synteny we noted a striking conservation of overall timing programs between mouse and human cells (Fig. 3A). To confirm these findings quantitatively, we compared timing values at the promoters of 16,629 orthologous genes (Fig. 3B), revealing that replication timing in each human cell type aligned most closely with the corresponding cell type in mouse. Interestingly, timing was considerably more conserved between hESCs and mEpiSCs vs. mESCs. In fact, the hESC to mEpiSC relationship was the strongest of all comparisons. Mouse and human lymphoblast alignment was also strong, consistent with a prior report (Farkash-Amar et al. 2008). Mouse and human NPCs were less well aligned, which may reflect differences in differentiation protocols and/or distinct subpopulations of neural precursor cells profiled in mouse vs. human (Schulz et al. 2004; Hiratani et al. 2008).

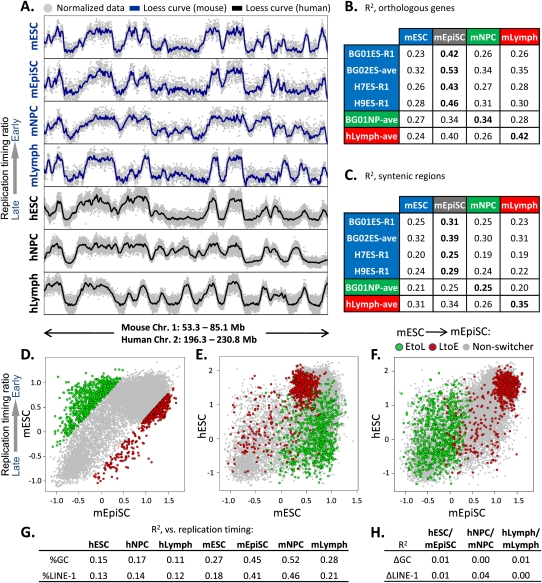

Figure 3.

Significant conservation of replication timing between hESCs and mEpiSCs. (A) Example of RT conservation between the indicated human and mouse cell types in one of 207 syntenic regions. (B) Correlation of replication timing (R2 values) between the indicated human and mouse cell types at 16,629 orthologous gene promoters. All mouse data are the averages of biological replicates, while both averaged replicates (ave) and exemplary single replicates (R1) are shown for human cell types. R2 differences ≥0.02 are statistically significant at P < 0.05 using Fisher R-to-Z transformation. (C) 207 syntenic regions >1 Mb were loess smoothed, and RT values were gathered at 100 equal intervals per window to obtain correlations of replication timing in syntenic regions. The significance of these alignments was calculated using bootstrapping (P < 0.0001), as described in the Methods. (D–F) Replication timing for orthologous genes with the top 5% of EtoL and LtoE timing changes in mESCs vs. mEpiSCs (D; [green] EtoL, [red] LtoE, [gray] non-switching) was compared with BG01 hESCs (E,F). Genes that transition from EtoL between mESCs and mEpiSCs generally remain late-replicating in hESCs. (G) Pearson R2 values between domain-wide replication timing and LINE-1 density or GC content are shown for the cell types indicated. Mouse data are from Hiratani et al. (2008, 2010). (H) Conservation (R2) between syntenic regions as in Figure 3C shows little relationship to differences in regional GC or LINE-1 content.

To broaden this analysis beyond genes, we examined 207 regions encompassing 91% of the mouse genome and 94% of the human genome where conserved synteny extended >1 Mb (see Methods). Replication timing values were collected in 100 equal intervals in each region (20,700 points overall) to calculate R2 values between cell types (Fig. 3C). The degree of conservation with this analysis was lower than for orthologous promoters, presumably because regions of conserved synteny have expanded and contracted unevenly, whereas gene promoters are precise landmarks and may have more conserved replication timing than nongenic regions. Nonetheless, significant conservation of replication timing was observed that was higher when similar cell types were compared and highest between hESCs and mouse EpiSCs. Conservation of replication time is unlikely to be driven strictly by the sequence content of mammalian isochores, because human cell types had a much lower correlation of replication time to GC or LINE-1 density that did not change during differentiation, unlike for mouse cells (Fig. 3G), and the degree of conservation between similar cell types was not related to isochore GC/LINE-1 density (Fig. 3H; Supplemental Fig. S10). Moreover, the degree of conservation was not related to enrichment of any of the analyzed histone marks (Supplemental Fig. S10). However, if the replication timing of a syntenic region was well conserved in one cell type, it was usually well conserved in the other cell types (Supplemental Fig. S10). Together, these results show a convincing degree of cell-type-specific evolutionary conservation between mouse and human replication timing profiles.

Human ESC replication profiles resemble mouse EpiSCs

Alignment between hESCs and mEpiSCs was striking (Fig. 3B), and the relative difference in alignment to mEpiSCs vs. mESCs was even more surprising considering their similarity in developmental stage and transcription profiles (Hiratani et al. 2010). Nonetheless, these cell types are phenotypically quite different, as EpiSCs cannot contribute efficiently to chimeric mice (Brons et al. 2007; Tesar et al. 2007). This suggests that the phenotypic differences between these cell types are better reflected by epigenetic properties such as replication timing than by transcriptional differences. To confirm the closer alignment of hESCs and mEpiSCs, we examined genes that switch EtoL or LtoE between mESCs and mEpiSCs (Fig. 3D). Consistently, genes that switch to later replication from mESCs to mEpiSCs are typically late replicating in hESCs, while those switching from early to very early are very early replicating in hESCs (Fig. 3E,F). These results further demonstrate that hESC replication profiles are more closely related to those of mouse EpiSCs than mESCs and underscore the ability of replication timing profiles to identify epigenetic differences between closely related cell types.

A chromatin signature for replication domain boundaries

Profiling replication timing in lymphoblastoid cells allowed us to make comparisons to several epigenetic marks that have been mapped genome-wide in this cell type (Rosenbloom et al. 2010). We first correlated the density of each of these marks within the boundaries of each replication domain to the replication timing of each domain (Fig. 4A,B). This analysis clearly revealed a general correlation between early domains and activating (H3K4me1,2,3; H3K9Ac, H3K27Ac; H3K36me3; H4K20me1) but not repressive (H3K9me2,3; H3K27me3) chromatin marks, consistent with that previously reported in mouse (Hiratani et al. 2008; Yokochi et al. 2009). This confirmation is important, since the mouse H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 data sets had a lower signal to noise ratio, and this finding contradicted a prior analysis based on 1% of the genome that claimed a high correlation of late replication to H3K27me3 (Thurman et al. 2007). Also similar to what we found in mouse, the strongest correlation between late replication and repressive chromatin marks was found with H3K9me2 (R = −0.54) (Fig. 4B), a mark that is also enriched in the late replicating nuclear periphery compartment of the nucleus (Wu et al. 2005; Yokochi et al. 2009). However, we have shown that knockout of the histone methyltransferase EHMT2, which eliminates peripheral H3K9me2, has no effect on the replication timing program or the programmed changes in replication timing that occur during mESC differentiation to mNPCs (Yokochi et al. 2009). Overall, these results confirm the link between early replication and histone marks associated with transcriptional activity, and suggest that late replication is either unrelated to well-studied heterochromatin-associated histone modifications or is related in a more complex, redundant, or combinatorial manner.

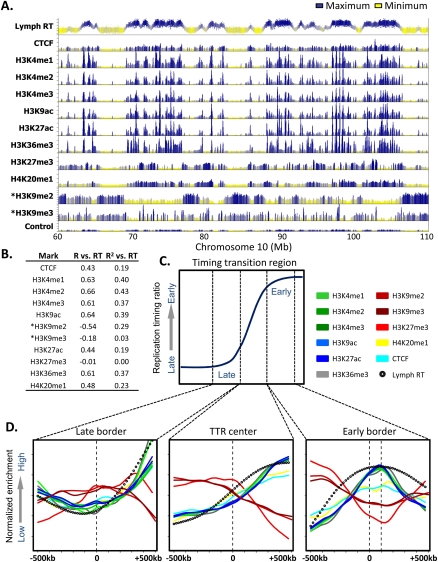

Figure 4.

A chromatin signature for replication domain boundaries. (A) Profiles of lymphoblastoid replication timing, CTCF, and the indicated histone modifications are shown for a representative 50-Mb region of chromosome 10. ChIP-seq data and the input control profile are from GM12878 lymphoblastoid ChIP-seq experiments hosted on the UCSC Genome Browser (Rosenbloom et al. 2010), with the exception of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 (asterisk), obtained from CDT4+ T-cells (Barski et al. 2007). (B) Domain-wide relationship between replication timing and histone modifications. Pearson R and R2 values of domain replication timing with each mark above were calculated as in Hiratani et al. (2008). (C) A diagrammatic timing transition region, in which windows of 1 Mb surrounding the late border, center, and early border are highlighted. (D) Average profiles of histone marks, CTCF, and replication timing are shown for the windows indicated in C.

Visual inspection of profiles at TTRs also hinted that several histone marks are enriched near the boundaries of early replicating domains. To verify this, we examined average profiles in 1-Mb windows focused on the center, early, and late boundaries of all TTRs >1 Mb throughout the genome (Fig. 4C,D). Consistently, we found a prominent peak for marks of active chromatin (H3K4me1/2/3, H3K36me3, H3K27ac) ∼100 kb inside the early replicating domain. H4K20me1 was the only “active” mark to show little or only modest enrichment, which may relate to the diverse nontranscriptional roles of this modification (Schotta et al. 2008; Oda et al. 2009). Intriguingly, there is a depletion of the repressive mark H3K27me3, and a modest depletion of H3K9me3 and H3K9me2 at this same position. Since this peak was identified in an ensemble analysis of all large TTRs, it could result from the average of many considerably sharper peaks at slightly different relative positions in each individual domain. In fact, inspection of 10 individual domains revealed very sharp peaks of active histone marks and a paucity of H3K27me3 at the early replicating boundaries of most domains (Supplemental Fig. S11).

These results suggest that a concentration of active histone modifications is found at the boundaries of early replication domains. It is possible that these marks serve as counter-modifications to prevent the spreading of heterochromatin into early replicating domains, similar to chromatin insulator sequences. One protein known to establish chromatin boundaries is the insulator-binding protein CTCF (Phillips and Corces 2009). However, we found little or no enrichment of CTCF near replication domain boundaries (Fig. 4D), although CTCF was enriched within early domains (Fig. 4B), consistent with its general proximity to transcriptional regulatory elements.

High alignment of replication timing to spatially separated compartments of genome-wide chromatin interactions (Hi-C)

Recently, a method was described (“Hi-C”) (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009) to analyze the spatial proximity of sequences to each other genome-wide by sequencing the ligation products generated by chromosome conformation capture (3C). Results of this analysis revealed the existence of two independent compartments of interaction (A and B) within the nucleus such that contacts between sequences within each compartment are enriched but contacts between sequences in different compartments are depleted. The compartments corresponded to spatially separated regions of chromosomes as confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Compartment B showed a higher interaction frequency and lower overall DNaseI accessibility, indicating that B represents more densely packed heterochromatin. When these compartments were plotted linearly with enrichment in compartment A as positive values and enrichment in compartment B as negative values (Eigenvector) (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009), we immediately noticed a striking correspondence between the Hi-C map and replication timing (Fig. 5A). This correspondence was cell-type-specific, as we could find many replication domain-sized discordances between the lymphoblast Hi-C and hESC or hNPC replication timing profiles. Remarkably, when comparing the lymphoblast Hi-C and replication timing profiles, even subtle variations in replication time along the profile of each chromosome were matched by subtle variations in chromatin interaction frequencies, a property quite unlike any other chromatin structural or functional features we have examined.

Figure 5.

Replication timing predicts long-range chromatin interactions. (A) Profiles of lymphoblastoid replication timing and a model of self-interacting regions of open or closed chromatin (Hi-C–positive values = open; Lieberman-Aiden et al. [2009]). hNPC and hESC replication profiles are shown alongside to illustrate cell-type specificity of the alignment. (B) The correlation between replication timing and the Hi-C chromatin interaction model for each chromosome is shown, calculated as for other epigenetic marks in Figure 4B. (C) Speculative model synthesizing the concepts revealed in Figures 4 and 5. The microscope image is a mouse fibroblast, pulse-labeled with iododeoxyuridine (IdU) early in S phase (green), subsequently pulse-labeled with chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU) late in S phase (red), and then immunofluorescently labeled with antibodies specific to each halogenated nucleotide, as in Wu et al. (2005) and Yokochi et al. (2009). This reveals the spatial compartmentalization of early and late replicating DNA, which is also supported by the reduced frequency of interaction between chromosomal sequences in Hi-C compartments A (green) and B (red). The cartoon is a schematic view of a pair of adjacent early (green) and late replicating (red) domains that are bounded at the early domain side by enrichment of active chromatin marks (yellow star). The replication domains resemble fractal globules described by (Lieberman-Aiden et al. (2009), and late and early domains are spatially separated by a large TTR. Late replicating Hi-C compartment B has a higher frequency of interactions, indicative of more condensed chromatin, which here is proposed to be less accessible to initiation factors for replication than early replicating Hi-C compartment A. (Green and red circles) Different protein components of early vs. late replicating chromatin.

To quantify this relationship genome-wide, we correlated Hi-C model data for each chromosome with replication timing as described in Figure 4B for other epigenetic marks. Despite the derivation of lymphoblastoid replication timing and Hi-C data from different lymphoblast cell lines (C0202 and GM06990, respectively), the overall correlation (R = 0.80) was the strongest we have identified to date between replication timing and any chromosomal feature. This correlation was found on every autosomal chromosome (Fig. 5B). The significantly lower correlation for the X chromosome is accounted for by the fact that replication timing was profiled in a male cell line while Hi-C was mapped in a female cell line, consistent with changes in replication timing and compartmentalization of replication domains after X chromosome inactivation (Hiratani et al. 2010). This uncanny relationship between spatial proximity and replication timing, measured using very different methodologies, provides a novel link between chromosome structure and function in the nucleus and indicates that sequences that are localized near each other will replicate at similar times, suggesting new models for the regulation of replication timing (discussed below).

Discussion

Our results define an hESC-specific replication profile that is stable across polymorphic cell lines and reacquired in reprogrammed hiPSCs, but significantly altered after differentiation. Sizes of replication domains, the temporal transitions between them, the units of replication timing change, and relationships to transcription were well conserved with mouse cells. Moreover, replication timing profiles themselves were conserved across regions of conserved synteny when similar mouse and human cell types were compared. This conservation was not accounted for simply by conservation of GC content, as GC content was not nearly as well aligned to replication timing in humans as was found in mouse. These results support the existence of positive selection mechanisms maintaining replication timing during evolution. Intriguingly, replication timing profiles identified a significantly greater similarity of hESC profiles to mouse EpiSCs than to embryologically and transcriptionally related mESCs. Hence, replication timing profiles provide a powerful means to reveal important distinctions between closely related cell types. Finally, we present the remarkable discovery that coordinately replicated domains represent chromatin in close 3D proximity, spatially separated from domains replicating at alternative times by origin-suppressed regions, and bounded on the early replicating side by strong sites of active histone modifications (Fig. 5C). These results provide compelling evidence that replication domains are structural and functional units of chromosomes whose replication timing is a reflection of their spatial position in the nucleus (Gilbert 2001).

Conserved and divergent features of replication timing

All eukaryotic organisms exhibit an orderly progression to the replication of their genomes (Hiratani and Gilbert 2009; Hiratani et al. 2009). While the significance of this program is unclear, evolutionarily conserved features of biological processes are likely to be functionally significant. Comparison of replication timing profiles between mouse and human cell types allowed us to identify several commonalities in the regulation of replication timing, including stable cell-type-specific profiles, tissue-specific size distributions of early and late replicating domains, punctuation of replication domains by large origin-suppressed regions, the sizes of chromosome units that change replication timing during differentiation, and connections between replication timing, histone modifications, and transcription. These consistent elements likely reflect similar mechanisms regulating replicon sizes and multireplicon organization of replication domains in mouse and human. Perhaps most surprising was the degree of conservation in the overall temporal order of replication along the lengths of large regions of conserved synteny, despite changes in sizes and nearby chromatin environment of intergenic regions.

Not all features of replication timing reorganization between ESCs and NPCs were conserved. In mouse, replication timing correlated with isochore sequence features of chromosomes such as GC/LINE-1 content (Hiratani et al. 2008), and the degree of this correlation was cell-type-specific (Hiratani et al. 2010). In contrast, human cell types had a weak correlation to GC/LINE-1 density that was similar in all cell types (Fig. 3G). Moreover, there was no correlation between conservation of GC/LINE-1 content and conservation of replication timing (Fig. 3H). Coupled with the observation that isochore GC content is undergoing constant change during evolution (Meunier and Duret 2004), we conclude that alignment of replication timing to isochore GC content is not evolutionarily conserved. Hence, replication timing is conserved across species, independent of the GC content of isochores.

Replication timing reflects chromosome architecture

Since there is no reason to presume that the basic process of duplicating the genome necessitates a specific temporal sequence, conservation likely reflects some property of chromosome structure that transcends the basic need to replicate DNA. We demonstrate a close alignment between replication timing and spatially separated compartments of chromatin folding, In fact, the recently described Hi-C interaction map aligns more closely with replication timing than any other chromosome property we have analyzed. For some chromosomes (chromosome 19, Fig. 5B), the alignment approaches that of replication timing replicates, despite differences in the source and sex of the lymphoblast cell lines compared. This is compelling evidence that chromatin in close spatial proximity replicates at a similar time. At the same time, it implies that the chromatin between spatially separated chromosome segments corresponds to temporal transitions in replication timing (TTRs) that are suppressed for origin activity.

How could these very different chromosomal properties be related (Fig. 5C)? We have previously demonstrated that replication timing is reestablished in each cell cycle coincident with the anchorage of chromosomal segments at specific positions within the nucleus, a point early in G1 phase that we have termed the “timing decision point,” or TDP (Dimitrova and Gilbert 1999). Anchorage and positioning are undoubtedly central to the formation of nuclear compartments that dictate the rules of chromatin interaction in the nucleus. Hence, the finding that replication timing aligns with interaction maps significantly strengthens the link between replication timing and 3D organization. Our model (Fig. 5C) and Gilbert (2001) predict that these interactions are disrupted during mitosis and must be reestablished. Early in G1 phase, chromatin is dynamic and potentially forms many inappropriate but transient chromatin interactions. As chromatin becomes anchored, subnuclear domains begin to self-assemble through a stabilizing process that involves the accumulation of mutually reinforcing protein–protein interactions. These are illustrated by Lieberman-Aiden et al. (2009) as self-assembling units of chromosomes, or “fractal globules.” In our version of this model, spatially separated fractal globules are equivalent to temporally separated replication domains with distinct origin-suppressed molecular boundaries. The positions of these boundaries may be maintained by the concentration of active chromatin marks that we identify here at the borders of early replicating domains (Fig. 4). According to the Hi-C model, a higher concentration of chromatin interactions is found in compartment B, which aligns with late replicating domains. Interestingly, compartment B is also considerably less accessible to DNaseI digestion (Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009). One interesting hypothesis then, is that chromatin interactions established during early G1 phase drive the assembly of compartments of the nucleus that are more or less accessible to the S-phase–promoting factors that initiate replication, allowing earlier access to sites of less compact chromosomal folding. Regardless, the findings reported here indicate that replication timing profiles provide a convenient readout of chromosome interactions and a means to identify chromosome segments that undergo large changes in 3D organization during differentiation.

Epigenetic status of hESCs revealed by replication profiling

Both mouse and human ESCs are derived from preimplantation blastocysts and have characteristic replication timing profiles that are reacquired when differentiated cells are reprogrammed to iPSCs. However, mESC replication profiles differ quite dramatically from pluripotent mEpiSCs derived from post-implantation embryos that are only a few cell cycles older than blastocysts (Hiratani et al. 2010). Consistent with a link between replication timing and chromosome architecture, ESCs and EpiSCs have substantial differences in chromatin organization and subnuclear position of genes that change replication timing (Hiratani et al. 2010). Intriguingly, only small differences in gene expression have been reported between ICM (E4.0–4.5) and epiblast cells at E5.0 or E5.5 (Pfister et al. 2007), or between mESCs and mEpiSCs (Hiratani et al. 2010) despite major phenotypic differences (Gardner and Brook 1997), including the efficiency of reprogramming and the ability to contribute to chimeric mice (Brons et al. 2007; Tesar et al. 2007; Guo et al. 2009). These observations indicate that significant epigenetic changes occur in the post-implantation epiblast in the absence of transcription changes. Recently, it was shown that hESCs and mEpiSCs share signaling pathways controlling early cell fate decisions (Vallier et al. 2009). Here, we show that the replication profiles of hESCs are more consistent with mEpiSCs than mESCs, with many mESC-specific genes switched to late replication (Fig. 3D–F), and most late replicating domains having completed domain consolidation (Fig. 1B). These findings provide genome-wide evidence that hESCs are stabilized in an epiblast-like epigenetic state. This altered epigenetic landscape may contribute to the substantially different POU5F1 (OCT4) and NANOG target genes found in hESCs vs. mESCs (Boyer et al. 2005; Sridharan et al. 2009). Altogether, replication profiles provide a means to distinguish the epigenetic state of closely related stem cell types, which may be important for therapeutic applications of stem cells.

Methods

Cell culture conditions and neural differentiation

hESCs (BG01, BG02, H7 [WA07], H9 [WA09]), as well as hiPSCs (Park et al. 2008) were maintained on Geltrex (Invitrogen) in StemPro defined media (Invitrogen; Wang et al. 2007). BG01 was differentiated to NPCs as described previously (Schulz et al. 2004). NPCs generated in this way can then be maintained for >3 mo and routinely expanded (Schulz et al. 2004). Neural progenitors were shown to express SOX1, SOX2, MSI1, PAX6, and NES, and to be negative for POU5F1 (previously known as OCT4), REXO1, NANOG, and CD9. Mouse L1210 lymphocytic leukemia cells (ATCC CCL219) and human C0202 lymphoblastoid cells (ECACC #94060845) were cultured as described (Woodfine et al. 2004; Farkash-Amar et al. 2008).

Replication profiling using HD2 microarrays

Genome-wide replication timing profiles were constructed as described (Hiratani et al. 2008) except that we employed NimbleGen HD2 arrays with 1.1-kb probe spacing. Two biological replicates were performed for all cell lines except BG01, H7, and H9.

Segmentation

Segmentation of individual probe data into replication domains was performed as described using the DNAcopy package in R (Hiratani et al. 2008). NimbleGen HD2 arrays, with fivefold higher probe density than the arrays used previously in mouse, were capable of resolving smaller replication domains after segmentation. To account for the dependency of segmentation on slight differences in autocorrelation of neighboring probes between data sets, we applied a small amount of Gaussian noise to BG01 NPC data sets to equalize their autocorrelation (ACF) (see Supplemental Fig. S2) to ESCs before segmentation.

Data normalization and smoothing

Individual raw microarray data sets were normalized and scaled to an equivalent median-absolute deviation using the limma package in R. To assign replication timing values to the 19,991 human RefSeq genes, replication timing ratios of each probe (log2 early/late fraction) were smoothed with a 300-kb span using loess in R, and smoothed values at transcription start sites were assigned to each gene. NimbleGen transcription array data were normalized by quantile normalization (Bolstad et al. 2003). Expression units (i.e., normalized gene calls) were generated using the RMA (Robust multichip average) algorithm as described (Irizarry et al. 2003). Since NimbleGen expression analysis does not generate a cutoff for “expressed” (transcriptionally active) vs. “silent” (transcriptionally inactive) genes, one was made at 400 expression units to yield a similar percentage of expressed genes as found in mESCs using Affymetrix arrays.

Identification of timing transition regions (TTRs)

Timing transition regions were identified by loess smoothing (with a span of 2 Mb) replication timing profiles of hESCs and mESCs, and isolating regions of high or low (±8e-7 RT/bp) slope. As these regions were well aligned to transition regions between early and late domains by visual inspection (Fig. 1C), we identified their boundaries and calculated their average slope.

Consolidation analysis

To quantify the degree to which domains become isolated or consolidated with neighboring domains in replication timing (Supplemental Fig. S7), we subtracted the probe replication timing values between hNPC (BG01NP-R1) and hESC (BG01ES-R1) and performed segmentation on this subtracted profile. We then calculated the differences in replication timing between each domain and its left (d1) and right (d2) neighbor. Reductions or increases in total d1 + d2 signify consolidation and isolation respectively.

Evolutionary comparisons and analysis of epigenetic marks

For comparison of mouse–human syntenic units, coordinates for 207 regions of level 1 net alignments larger than 1 Mb (Kent et al. 2003) were obtained from the UCSC table browser (mm8 vs. hg18net). To control for differences in syntenic region size between the two species, replication timing values for each cell type were loess smoothed in R with a span of 300 kb and collected in 100 equal intervals per region. R2 values were calculated from the total collection of 20,700 values. To obtain the significance through bootstrapping of R2 values above, this process was repeated 10,000 times with 207 randomly selected regions equal in size to the syntenic regions to obtain the probability that R2 values as high as those observed could occur by chance. The highest R2 value found using such randomly selected regions for a total of 10,000 trials was 0.02; thus, the overall alignment between human and mouse cell types is highly significant (P < 0.0001). For epigenetic mark comparisons, data sets from lymphoblastoid cells (GM12878; Yale Encode for build Hg18) were obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser and averaged in 1-Mb windows across TTR boundaries in R. Comparison to the Hi-C model was made using 100-kb window eigenvector data corresponding to the checkerboard patterns in Lieberman-Aiden et al. (2009).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Didier for assistance with flow cytometry and G.Q. Daley for hiPSC lines. We also thank S. Theis and A. Natesan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by PO1 GM085354 to D.M.G. and S.D. S.D. is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD049647) and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (GM75334).

Author contributions: Conception and design, T.R. and D.M.G.; data analysis and interpretation, T.R. and J.Z.; collection and assembly of data, I.H., J.L., and M.I.; provision of material, M.K. and S.D.; manuscript writing, T.R. and D.G.; financial support, S.D. and D.M.G..

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at http://www.genome.org. The microarray data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession no. GSE20027.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.099655.109.

References

- Arney KL, Fisher AG 2004. Epigenetic aspects of differentiation. J Cell Sci 117: 4355–4363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129: 823–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19: 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, et al. 2005. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 122: 947–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brons IG, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun B, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Howlett SK, Clarkson A, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pedersen RA, et al. 2007. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 448: 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprat R, Thierry-Mieg D, Lailler N, Lajugie J, Schildkraut C, Thierry-Mieg J, Bouhassira EE 2009. Predictable dynamic program of timing of DNA replication in human cells. Genome Res 19: 2288–2299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova DS, Gilbert DM 1999. The spatial position and replication timing of chromosomal domains are both established in early G1-phase. Mol Cell 4: 983–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkash-Amar S, Simon I 2009. Genome-wide analysis of the replication program in mammals. Chromosome Res doi: 10.1007/s10577-009-9091-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkash-Amar S, Lipson D, Polten A, Goren A, Helmstetter C, Yakhini Z, Simon I 2008. Global organization of replication time zones of the mouse genome. Genome Res 18: 1562–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RL, Brook FA 1997. Reflections on the biology of embryonic stem (ES) cells. Int J Dev Biol 41: 235–243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DM 2001. Nuclear position leaves its mark on replication timing. J Cell Biol 152: F11–F16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DM 2002. Replication timing and transcriptional control: Beyond cause and effect. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14: 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DM, Gasser SM 2006. Nuclear structure and DNA replication. In DNA replication and human disease (ed. DePamphilis ML), pp. 175–196 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York [Google Scholar]

- Guan Z, Hughes CM, Kosiyatrakul S, Norio P, Sen R, Fiering S, Allis CD, Bouhassira EE, Schildkraut CL 2009. Decreased replication origin activity in temporal transition regions. J Cell Biol 187: 623–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Yang J, Nichols J, Hall JS, Eyres I, Mansfield W, Smith A 2009. Klf4 reverts developmentally programmed restriction of ground state pluripotency. Development 136: 1063–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RS, Thomas S, Sandstrom R, Canfield TK, Thurman RE, Weaver M, Dorschner MO, Gartler SM, Stamatoyannopoulos JA 2010. Sequencing newly replicated DNA reveals widespread plasticity in human replication timing. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 139–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratani I, Gilbert DM 2009. Replication timing as an epigenetic mark. Epigenetics 4: 93–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratani I, Ryba T, Itoh M, Yokochi T, Schwaiger M, Chang CW, Lyou Y, Townes TM, Schubeler D, Gilbert DM 2008. Global reorganization of replication domains during embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Biol 6: e245 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratani I, Takebayashi S, Lu J, Gilbert DM 2009. Replication timing and transcriptional control: Beyond cause and effect–part II. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19: 142–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratani I, Ryba T, Itoh M, Rathjen J, Kulik M, Papp B, Fussner E, Bazett-Jones DP, Plath K, Dalton S, et al. 2010. Genome-wide dynamics of replication timing revealed by in vitro models of mouse embryogenesis. Genome Res 20: 155–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4: 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Baertsch R, Hinrichs A, Miller W, Haussler D 2003. Evolution's cauldron: Duplication, deletion, and rearrangement in the mouse and human genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 11484–11489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Chen J, Izumi M, Butler MC, Keezer SM, Gilbert DM 2001. The replication timing program of the Chinese hamster beta-globin locus is established coincident with its repositioning near peripheral heterochromatin in early G1 phase. J Cell Biol 154: 283–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO, et al. 2009. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326: 289–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlpine DM, Bell SP 2005. A genomic view of eukaryotic DNA replication. Chromosome Res 13: 309–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier J, Duret L 2004. Recombination drives the evolution of GC-content in the human genome. Mol Biol Evol 21: 984–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda H, Okamoto I, Murphy N, Chu J, Price SM, Shen MM, Torres-Padilla ME, Heard E, Reinberg D 2009. Monomethylation of histone H4-lysine 20 is involved in chromosome structure and stability and is essential for mouse development. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2278–2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ 2008. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 451: 141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister S, Steiner KA, Tam PP 2007. Gene expression pattern and progression of embryogenesis in the immediate post-implantation period of mouse development. Gene Expr Patterns 7: 558–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Corces VG 2009. CTCF: Master weaver of the genome. Cell 137: 1194–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom KR, Dreszer TR, Pheasant M, Barber GP, Meyer LR, Pohl A, Raney BJ, Wang T, Hinrichs AS, Zweig AS, et al. 2010. ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC Genome Browser. Nucleic Acids Res 38: D620–D625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotta G, Sengupta R, Kubicek S, Malin S, Kauer M, Callen E, Celeste A, Pagani M, Opravil S, De La Rosa-Velazquez IA, et al. 2008. A chromatin-wide transition to H4K20 monomethylation impairs genome integrity and programmed DNA rearrangements in the mouse. Genes & Dev 22: 2048–2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubeler D, Scalzo D, Kooperberg C, Van Steensel B, Delrow J, Groudine M 2002. Genome-wide DNA replication profile for Drosophila melanogaster: A link between transcription and replication timing. Nat Genet 32: 438–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz TC, Noggle SA, Palmarini GM, Weiler DA, Lyons IG, Pensa KA, Meedeniya AC, Davidson BP, Lambert NA, Condie BG 2004. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to dopaminergic neurons in serum-free suspension culture. Stem Cells 22: 1218–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaiger M, Stadler MB, Bell O, Kohler H, Oakeley EJ, Schubeler D 2009. Chromatin state marks cell-type- and gender-specific replication of the Drosophila genome. Genes & Dev 23: 589–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan R, Tchieu J, Mason MJ, Yachechko R, Kuoy E, Horvath S, Zhou Q, Plath K 2009. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell 136: 364–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi N, Sugawara O, Sasaki M 1982. Regional and temporal changes in the pattern of X-chromosome replication during the early post-implantation development of the female mouse. Chromosoma 85: 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesar PJ, Chenoweth JG, Brook FA, Davies TJ, Evans EP, Mack DL, Gardner RL, McKay RD 2007. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature 448: 196–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman RE, Day N, Noble WS, Stamatoyannopoulos JA 2007. Identification of higher-order functional domains in the human ENCODE regions. Genome Res 17: 917–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallier L, Touboul T, Chng Z, Brimpari M, Hannan N, Millan E, Smithers LE, Trotter M, Rugg-Gunn P, Weber A, et al. 2009. Early cell fate decisions of human embryonic stem cells and mouse epiblast stem cells are controlled by the same signalling pathways. PLoS One 4: e6082 doi: 10/1371/journal.pone.0006082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman ES, Olshen AB 2007. A faster circular binary segmentation algorithm for the analysis of array CGH data. Bioinformatics 23: 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Schulz TC, Sherrer ES, Dauphin DS, Shin S, Nelson AM, Ware CB, Zhan M, Song CZ, Chen X, et al. 2007. Self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells requires insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and ERBB2 receptor signaling. Blood 110: 4111–4119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Ikemura T, Sugimura H 2004. Amplicons on human chromosome 11q are located in the early/late-switch regions of replication timing. Genomics 84: 796–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weddington N, Stuy A, Hiratani I, Ryba T, Yokochi T, Gilbert DM 2008. ReplicationDomain: A visualization tool and comparative database for genome-wide replication timing data. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 530 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RR, Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, Dvorkina M, Jorgensen H, Roix J, McQueen P, Misteli T, Merkenschlager M, et al. 2006. Neural induction promotes large-scale chromatin reorganisation of the Mash1 locus. J Cell Sci 119: 132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodfine K, Fiegler H, Beare DM, Collins JE, McCann OT, Young BD, Debernardi S, Mott R, Dunham I, Carter NP 2004. Replication timing of the human genome. Hum Mol Genet 13: 191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R, Terry AV, Singh PB, Gilbert DM 2005. Differential subnuclear localization and replication timing of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation states. Mol Biol Cell 16: 2872–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutz A, Jaenisch R 2000. A shift from reversible to irreversible X inactivation is triggered during ES cell differentiation. Mol Cell 5: 695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokochi T, Poduch K, Ryba T, Lu J, Hiratani I, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, Gilbert DM 2009. G9a selectively represses a class of late-replicating genes at the nuclear periphery. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 19363–19368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Ermakova OV, Riblet R, Birshtein BK, Schildkraut CL 2002. Replication and subnuclear location dynamics of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus in B-lineage cells. Mol Cell Biol 22: 4876–4889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]