Abstract

Background

Nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (nHCM) is often associated with reduced exercise capacity despite hyperdynamic systolic function as measured by left ventricular ejection fraction. We sought to examine the importance of left ventricular strain, twist, and untwist as predictors of exercise capacity in nHCM patients.

Methods

Fifty-six nHCM patients (31 male and mean age of 52 years) and 43 age- and gender-matched controls were enrolled. We measured peak oxygen consumption (peak Vo2) and acquired standard echocardiographic images in all participants. Two-dimensional speckle tracking was applied to measure rotation, twist, untwist rate, strain, and strain rate.

Results

The nHCM patients exhibited marked exercise limitation compared with controls (peak Vo2 23.28 ± 6.31 vs 37.70 ± 7.99 mL/[kg min], P < .0001). Left ventricular ejection fraction in nHCM patients and controls was similar (62.76% ± 9.05% vs 62.48% ± 5.82%, P = .86). Longitudinal, radial, and circumferential strain and strain rate were all significantly reduced in nHCM patients compared with controls. There was a significant delay in 25% of untwist in nHCM compared with controls. Both systolic and diastolic apical rotation rates were lower in nHCM patients. Longitudinal systolic and diastolic strain rate correlated significantly with peak Vo2 (r = −0.34, P = .01 and r = 0.36, P = .006, respectively). Twenty-five percent untwist correlated significantly with peak Vo2 (r = 0.36, P = .006).

Conclusions

In nHCM patients, there are widespread abnormalities of both systolic and diastolic function. Reduced strain and delayed untwist contribute significantly to exercise limitation in nHCM patients.

Patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (nHCM) often complain of breathlessness and/or fatigue, and most have reduced exercise capacity.1 Patients with nHCM typically exhibit diastolic dysfunction, which is thought to contribute significantly to the genesis of breathlessness in these patients. Active relaxation is slowed and filling rate is typically diminished at rest in nHCM patients.2 Furthermore, we previously showed that there is frequently a failure of the normal increase in rate of active relaxation (as measured by time to peak filling) on exercise; indeed, in some patients, active relaxation paradoxically slowed on exertion.1

Resting echocardiographic Doppler parameters of left ventricle (LV) filling have been used to measure diastolic function.3 However, these parameters are dependent on loading conditions. The LV twists during systole as a result of counterclockwise rotation of the apex and clockwise rotation of the base with corresponding untwisting during diastole. The resulting untwisting may represent a useful marker of diastolic function.4,5 The velocity of LV untwisting has been correlated with invasive measurements of LV relaxation under a variety of loading and inotropic conditions in animal models. Dong et al6 confirmed that LV untwisting is a measure of LV relaxation that is independent of preload as reflected in left atrial (LA) pressure.

The development of speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) has allowed LV strain, twisting, and untwisting rates to be measured relatively easily with reasonably high temporal resolution.7 In this study, we used STE to measure LV strain, strain rate, and twist and untwist rates in nHCM patients and controls; and we sought to assess their relationship with exercise capacity.

Methods

This study was funded by a British Heart Foundation project grant (PG/05/087). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper, and its final contents.

Fifty-six nHCM patients and 43 age- and gender-matched controls were included in this study, all of whom provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and the investigations conform to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants had electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiogram, and cardiopulmonary exercise test.

Patients and controls selection

All HCM patients were in sinus rhythm and fulfilled conventional echocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of HCM (LV wall thickness >1.5 cm in the absence of another cause for hypertrophy and without cavity dilatation).8,9 All HCM patients underwent assessment of LV outflow tract obstruction gradient, and those with a resting or provocable gradient (on Valsalva maneuver) >30 mm Hg were excluded. Those patients were excluded because LV outflow tract obstruction is an important cause of symptoms and exercise limitation. All controls had no history or symptoms of any cardiovascular disease, with normal ECG and echocardiogram (LV ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥55%).

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

This was performed using a Schiller (Baar, Switzerland) CS-200 Ergo-Spiro exercise machine that was calibrated before every study. Subjects underwent spirometry, and this was followed by symptom-limited erect treadmill exercise testing using a standard ramp protocol with simultaneous respiratory gas analysis.10,11 Samplings of expired gases were performed continuously, and data were expressed as 30-second means. Minute ventilation, oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and respiratory exchange ratio were obtained. Peak oxygen consumption (peak Vo2) was defined as the highest Vo2 achieved during exercise and was expressed in milliliters per minute per kilogram. Blood pressure and ECG were monitored throughout. Participants were encouraged to exercise to exhaustion with a minimal requirement of respiratory exchange ratio >1.

Resting echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed with participants in the left lateral decubitus position with a GE (Horten, Norway) Vivid 7 echocardiographic machine and a 2.5-MHz transducer. Measurements were averaged for 3 beats and were stored digitally and analyzed off-line. Resting scans were acquired in standard long and short parasternal basal level (at mitral valve), papillary muscle level, and apical level (distal LV cavity where papillary muscle is not visible) as previously described12 as well as apical 4-chamber and apical 2-chamber axis. Left ventricular volumes were obtained by biplane echocardiography, and LVEF was derived from a modified Simpson formula.13 A pulse wave Doppler sample volume was placed at the mitral valve tips to record 3 cardiac cycles. Mitral annulus velocities (pulse wave tissue Doppler imaging [PW-TDI]) were recorded from basal anterolateral and basal inferoseptal segment in apical 4-chamber view. Left atrial volumes were measured by area length method from apical 2 and 4 chambers as previously described13 and indexed to body surface area to derive LA volume index (LAVI). Left ventricular mass was measured by area length method and indexed to body surface area to derive LV mass index as previously described.14 The greatest thickness measured in the LV wall at any short-axis parasternal view was considered to represent maximal LV wall thickness (MWT) in nHCM patients.15

Speckle tracking echocardiography

Speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) was measured using Echopac workstation (version 4.2.0) (GE Vingmed Ultrasound AS, Horten, Norway). In this speckle tracking method,16-18 the displacement of speckles of myocardium in each spot was analyzed and tracked from frame to frame. We selected the best-quality digital 2-dimensional image cardiac cycle, and the LV endocardium was traced at end systole.19 The region of interest width was adjusted as required to fit the wall thickness. The software package then automatically tracked the motion through the rest of the cardiac cycle. Adequate tracking was verified in real time. A tracking score of ≤2.5 was accepted with frame rate between 60 and 100 Hz. Left ventricular peak strain and strain rate were measured in all segments and then averaged, representing the entire myocardium. The basal and apical LV global rotation (rot) and LV rotation rate (rot-r) STE data were measured from basal and apical short-axis view, respectively; exported to a spreadsheet program (Excel 2003, Microsoft Corp, Seattle, WA); and then exported to DPlot Graph Software (2001-2008 by HydeSoft Computing, Inc, Vicksburg, MS) to calculate LV twisting and untwisting rate.7 Definitions of twist and untwist are shown in (Figure 1). Interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility and variability of STE twist, untwist, and strain measurements were previously validated by our group.20,21

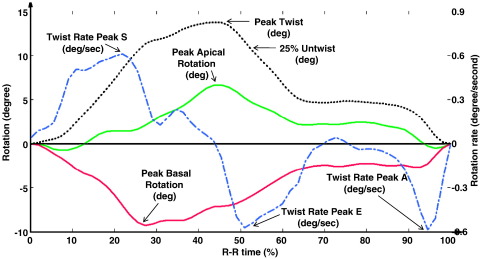

Figure 1.

Illustration of STE measurement of rotation and twist in a control subject. To adjust for heart rate, R-R interval was converted to 100%. Green line represents global apical rotation. whereas red line represents global basal rotation. At apical level, the LV rotates counterclockwise as viewed from apex and results in a positive value during systole, whereas the base rotates clockwise and results in a negative value, as in this representative case. Black dotted line represents LV twist that was calculated as the simultaneous net difference between apical and basal rotation. Blue dotted line represents the LV twist rate that was calculated as a differential curve of the twist curve.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and Microsoft Office Excel 2007, and expressed as mean ± SD. Comparison of variables between nHCM patients and controls was by the unpaired Student t test (2-tailed) if variables were normally distributed and the Mann-Whitney U test if the data were nonnormally distributed. A difference of P < .05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine correlations between exercise capacity and echocardiographic parameters in nHCM patients. Multivariate linear regression stepwise analysis was then performed by entering into model variables that were considered significant on univariate analysis to determine independent predictors of exercise capacity.

Results

The clinical characteristics and cardiopulmonary exercise test results of nHCM patients and controls are shown in Table I. Both groups were well matched with respect to age and gender. The nHCM patients exhibited marked exercise limitation as compared with controls, whereas mean EF was comparable in both groups. Heart rate was lower in the nHCM group as compared with controls because of rate-limiting medication (β-blockers or/and calcium-channel blockers).

Table I.

The clinical characteristics and cardiopulmonary exercise test results of nHCM patients and controls

| Parameter | nHCM | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 52 ± 11 | 51 ± 16 | .74 |

| n (female) | 56 (16) | 43 (12) | .64 |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 69 ± 13 | 80 ± 16 | .0002⁎ |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 126 ± 19 | 125 ± 20 | .78 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 78 ± 11 | 78 ± 11 | .80 |

| Peak Vo2 (mL/[kg min]) | 23.28 ± 6.31 | 37.70 ± 7.99 | <.0001⁎ |

| Drug therapy, n (%) | |||

| Diuretic | 10 (18) | 0 | – |

| ACE inhibitor | 6 (11) | 0 | – |

| ARB | 1 (2) | 0 | – |

| β-Blocker | 17 (31) | 0 | – |

| Calcium-channel blocker | 26 (47) | 0 | – |

| Aspirin | 13 (24) | 0 | – |

| Warfarin | 5 (9) | 0 | – |

| Nitrate | 2 (4) | 0 | – |

| Statin | 15 (27) | 0 | – |

BP, Blood pressure; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Indicates statistical significance.

Conventional echocardiographic measurements

Standard, Doppler, and PW-TDI echocardiographic findings of nHCM and controls groups are listed in Table II. Transmitral Doppler measurements showed no significant difference in early diastolic peak (peak E), late diastolic peak (peak A), and E/A ratio in nHCM versus controls (Table II). However, PW-TDI measurements of myocardial peak systolic velocity (Sm), myocardial peak early diastolic velocity (Em), myocardial peak late diastolic velocity (Am), and E/Em of the inferoseptal, anterolateral, and average basal segments were significantly lower in nHCM patients compared with controls (Table II).

Table II.

Standard, Doppler, and PW-TDI echocardiographic characteristics of nHCM versus controls

| Parameter | nHCM | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EF biplane (%) | 62.76 ± 9.05 | 62.48 ± 5.82 | .86 |

| Biplane LA volume (mL) | 72.69 ± 29.22 | 35.09 ± 9.83 | <.0001⁎ |

| LAVI (mL/m2) | 33.92 ± 14.62 | 11.76 ± 10.17 | <.0001⁎ |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 181.92 ± 84.09 | 71.67 ± 23.82 | <.0001⁎ |

| MV E (m/s) | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 0.67 ± 0.15 | .49 |

| MV A (m/s) | 0.64 ± 0.19 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | .17 |

| MV E/A | 1.18 ± 0.48 | 1.20 ± 0.38 | .83 |

| MV dec time (ms) | 231.12 ± 71.66 | 260.10 ± 68.24 | .06 |

| Antlat Sm (cm/s) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | <.0001⁎ |

| Antlat Em (cm/s) | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | <.0001⁎ |

| Antlat Am (cm/s) | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | <.0001⁎ |

| Infsep Sm (cm/s) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | .0001⁎ |

| Infsep Em (cm/s) | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | <.0001⁎ |

| Infsep Am (cm/s) | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | <.0001⁎ |

| Average Sm (cm/s) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | <.0001⁎ |

| Average Em (cm/s) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | <.0001⁎ |

| E/Emantlat | 9.70 ± 3.86 | 6.71 ± 2.35 | .0001⁎ |

| E/Eminfsep | 17.05 ± 7.38 | 9.64 ± 3.34 | <.0001⁎ |

| E/Emaverage | 11.81 ± 4.28 | 8.04 ± 2.92 | <.0001⁎ |

MV E, Transmitral early diastole velocity; MV A, transmitral late diastole velocity; dec, deceleration.

Indicates statistical significance.

Two-dimensional STE measurements

The STE measurements of strain and strain rate are shown in Table III. Longitudinal strain and strain rate (SrL) during both systole and diastole were all significantly reduced in nHCM patients as compared with controls. Similarly, radial strain and strain rate were also significantly lower in nHCM patients than in controls. Circumferential strain and diastolic circumferential strain rate (SrC) were also significantly lower in nHCM patients as compared with controls. There was a nonsignificant trend to lower systolic SrC in nHCM patients compared with controls.

Table III.

STE results of longitudinal, radial, and circumferential strain and strain rates in nHCM patients versus controls

| Parameter | nHCM | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | |||

| SL peak S (%) | −12.74 ± 4.21 | −18.38 ± 2.99 | <.0001⁎ |

| SrL peak S (1/s) | −0.92 ± 0.25 | −1.14 ± 0.2 | <.0001⁎ |

| SrL peak E (1/s) | 0.94 ± 0.35 | 1.33 ± 0.3 | <.0001⁎ |

| SrL peak A (1/s) | 0.78 ± 0.28 | 1.07 ± 0.29 | <.0001⁎ |

| Radial | |||

| SR peak S (%) | 17.52 ± 7.86 | 29.63 ± 13.26 | <.0001⁎ |

| SrR peak S (1/s) | 1.22 ± 0.34 | 1.39 ± 0.34 | .02⁎ |

| SrR peak E (1/s) | −1.0 ± 0.39 | −1.46 ± 0.52 | <.0001⁎ |

| SrR peak A (1/s) | −0.77 ± 0.38 | −1.09 ± 0.61 | <.01⁎ |

| Circumferential | |||

| SC peak S (%) | −16.50 ± 4.29 | −19.99 ± 5.53 | <.001⁎ |

| SrC peak S (1/s) | −1.4 ± 0.35 | −1.54 ± 0.34 | .05 |

| SrC peak E (1/s) | 1.34 ± 0.42 | 1.8 ± 0.65 | <.001⁎ |

| SrC peak A (1/s) | 0.87 ± 0.34 | 1.09 ± 0.47 | .02⁎ |

SL, Longitudinal strain; SR, radial strain, SrR, radial strain rate; SC, circumferential strain.

Indicates statistical significance.

Twist and untwist rate

The STE measurements of LV rotation, twist, and untwist in both groups are shown in Table IV. There was no significant difference in the LV ability to twist in systole and untwist in diastole between nHCM and controls. However, 25% untwist was significantly delayed in nHCM versus controls. Unlike the base, there was a significant reduction in apical rotation rates during systole and diastole in nHCM patients as compared with controls.

Table IV.

STE measurement of LV rotation, twist, and untwist in nHCM and controls

| Parameter | nHCM | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apical rot and rot-r | |||

| Peak rot (°) | 7.65 ± 6.90 | 9.48 ± 5.40 | .18 |

| Peak S rot-r (°/s) | 49.77 ± 49.49 | 74.56 ± 42.25 | .01⁎ |

| Peak E rot-r (°/s) | −41.19 ± 39.14 | −72.96 ± 38.00 | <.001⁎ |

| Peak A rot-r (°/s) | −26.24 ± 33.94 | −39.87 ± 27.01 | <.05⁎ |

| Basal rot and rot-r | |||

| Peak rot (°) | −6.25 ± 3.73 | −5.80 ± 2.81 | .55 |

| Peak S rot-r (°/s) | −57.89 ± 28.94 | −61.24 ± 17.82 | .54 |

| Peak E rot-r (°/s) | 53.07 ± 25.96 | 48.88 ± 26.42 | .47 |

| Peak S rot-r (°/s) | 42.39 ± 24.52 | 44.67 ± 20.68 | .65 |

| Twist and untwist | |||

| Peak twist (°) | 13.37 ± 7.14 | 13.69 ± 6.55 | .83 |

| 25% Untwist (°) | 9.85 ± 5.47 | 10.27 ± 4.91 | .71 |

| Time 25% untwist (R-R%) | 11.34 ± 5.63 | 7.21 ± 8.01 | .01⁎ |

R-R, R-R interval.

Indicates statistical significance.

Relation to exercise capacity

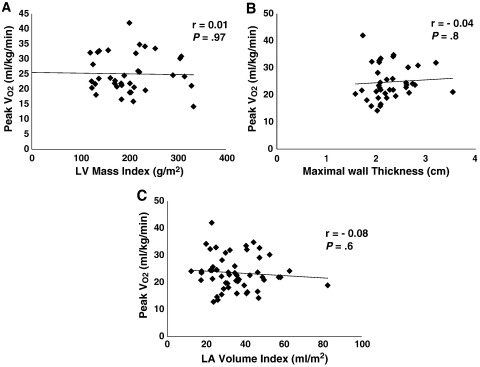

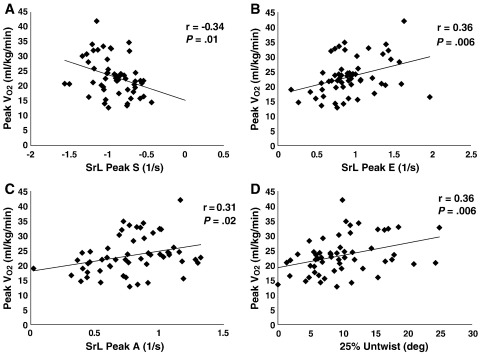

In nHCM patients, exercise capacity (peak Vo2) was independent of LV mass index (r = 0.01, P = .97) (Figure 2, A), MWT (r = 0.04, P = .8) (Figure 2, B), or LAVI (r = −0.08, P = .6) (Figure 2, C). However, it significantly correlated with the following STE parameters: SrL during systole (systolic peak [peak S]) (r = −0.34, P = .01) (Figure 3, A), during early diastole (peak E) (r = 0.36, P = .006) (Figure 3, B), and during late diastole (peak A) (r = 0.31, P = .02) (Figure 3, C); and it also correlated with 25% untwist (r = 0.36, P = .006) (Figure 3, D). The 25% untwist and SrL peak E were independent predictors of exercise capacity (P = .003 and P = .01, respectively).

Figure 2.

Correlation between exercise capacity (peak Vo2) and (A) LV mass index, (B) maximal wall thickness, and (C) LV volume index.

Figure 3.

Correlation between exercise capacity (peak Vo2) and (A) SrL peak S, (B) SrL peak E, (C) SrL peak A, and (D) 25% untwist.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed myocardial strain using an ultrasound speckle tracking technique that avoids the angle dependency of Doppler-based techniques. Longitudinal, radial, and circumferential strain and strain rates, and twist and untwist rates were measured in nHCM patients and in age- and gender-matched controls. Although nHCM patients typically exhibit hyperdynamic systolic function as assessed by conventional echocardiography, our STE findings of reduced SrL and delayed 25% untwist as significant predictors of exercise capacity are to the best of our knowledge novel.

The STE tracks characteristic speckle patterns created by interference of ultrasound beams in the myocardium that is based on gray scale B-mode images, and is angle independent.22 In humans, measurement of LV long-axis strain by STE correlated well with magnetic resonance imaging tagging (r = 0.87).23 We are now able to characterize myocardial function in greater detail, breaking down global function into the individual components that make up the whole. This can now be done for both the diastolic phase and systolic phase of myocardial function quickly and reproducibly using a relatively new technique of speckle tracking. Our findings of reduced longitudinal, circumferential, and radial strains are in agreement with previously published works.24 However, the clinical relevance of these alterations in function has not been previously assessed.

Systolic function in HCM

The function of the LV is often described as hyperdynamic in HCM. This is based on the frequent observation of high normal or supranormal EF. In this study, we showed that HCM patients had reduced systolic STE-derived longitudinal, circumferential, and radial strain and strain rates despite normal LVEF. These results are consistent with TDI-derived data that have shown that systolic long-axis function is reduced in patients with HCM.25 Carasso et al26 showed reduced longitudinal but higher circumferential STE-derived strain and strain rate in HCM patients compared with controls. Our findings of reduced circumferential strain are consistent with previous tagged magnetic resonance imaging studies.27,28

Diastolic function in HCM

The majority of HCM patients have some degree of diastolic dysfunction29-32 independent of symptoms, the presence of ventricular outflow tract obstruction, the magnitude of hypertrophy, or a combination of these.25,30,33,34 The mechanisms responsible for the diastolic dysfunction are probably multifactorial. The hypertrophy, myocyte disarray, and fibrosis may increase passive LV stiffness. Several studies had shown abnormalities of active relaxation in HCM patients35,36; and these may relate to abnormal calcium handling,37 to microvascular myocardial ischemia and mechanical dyssynchrony,38 or to impaired myocardial energy utilization.39-41 There are several echocardiographic measurements that can quantify diastolic dysfunction in HCM patients, but there remain some controversies about their accuracy. Our data showed no significant difference in transmitral Doppler-derived parameters between HCM patients and controls. However, there were significant abnormalities of other echocardiographic measurements of diastolic function (such as LA volume, LAVI, and TDI-derived indexes) in HCM patients. More importantly, untwist (a marker of diastolic function) was significantly delayed in these patients, which is in agreement with a previous study.42

Exercise limitation in HCM

Traditionally, it has been believed that LV diastolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of breathlessness and exercise limitation in HCM patients.1 Interestingly, we found that markers of both LV systolic and diastolic function significantly correlated with exercise capacity.

We have previously1 demonstrated that exercise capacity in patients with HCM is limited by the failure to increase stroke volume on peak exercise. Furthermore, we showed an abnormal lengthening of time to peak LV filling on exercise in these patients.1 The mechanism of this limitation of LV filling has not been fully elucidated. Left ventricular untwist is increasingly being recognized as an important component of diastolic function, contributing significantly to suction. Knudtson et al43 have shown that myocardial ischemia impairs untwist. Untwisting, a recoil phenomenon, occurs during the isovolumetric relaxation period, tending toward geometric restoration of the zero twist point (end diastole) with concurrent maximum LV volume. Twist and untwist rates appear to be closely related. During systole, myocardial deformation (twist) results in elastic energy being stored in compressed titin44 and transmural shear between myofibril sheets.45 This energy is spent during early diastole, before the onset of LV filling,46 which leads to untwisting of the LV that contributes to the generation of suction. The basis of twist and untwist abnormalities in HCM patients is possibly due to regional abnormalities of systolic and diastolic function.47 Peak ventricular untwist rate has been correlated with the time constant of LV pressure decay and intraventricular pressure gradients, both markers of diastolic function.48 Reduced untwist rate may lead to impairment in diastolic filling, which becomes more notable with increased heart rates16 due to short filling period. Notomi et al16 showed that greater untwisting rate produced an increase in suction during exercise in healthy subjects, which is able to fill the ventricle more despite a shorter filling period. This suggests that untwist rate is an important mechanism augmenting LV filling. The delayed untwist in HCM patients observed in this study may lead to reduced LV suction and filling, which will reduce the ability to use the Starling mechanism, leading to a failure to increase cardiac output, and as a result will limit exercise capacity.

Study limitation

The relevance of changes in twist and untwist during exercise would be interesting to examine; however, we here demonstrate that even resting measurements of strain and untwist were significant predictors of exercise capacity. We have been unable to reliably measure these parameters during exercise because of several technical difficulties. First of all, it was hard to maintain the same heart rate during exercise while acquiring apical and basal short-axis echocardiographic images that are crucial for the measurement of twist and untwist. Furthermore, exercise exaggerates the issue of through-plane motion, particularly at the basal short-axis level that is again vital for twist measurement. In addition, the current STE analysis software has insufficient temporal resolution for higher heart rate during exercise. It optimally operates at frame rate of 40 to 100 frames per second that is adequate only for resting studies. Moreover, excessive respiratory movement may degrade the quality of images as compared with the resting images. Further advances in the STE technique (eg, 3-dimensional speckle tracking with higher temporal resolution) are required to resolve these issues.

In this study, we report that there are no significant differences in twist between nHCM patients and controls. However, we showed a significant reduction in apical rotation rates during both systole and diastole. Previous study showed that apical rotation represents the major contributions to LV twist.49 The absence of significant differences in LV twist observed in this study could be explained by the increased through-plane motion at the base of the heart.

The heart rate is slower in the nHCM group (Table I) probably because of medications (ie, β-blockers and/or calcium-channel blockers). Such therapy might have affected the findings in these patients. All pertinent physiologic parameters were corrected for heart rate. Untwist timing parameters were corrected for heart rate by converting R-R interval to 100% as previously described.50 All longitudinal, radial, and circumferential strain parameters were independent of heart rate because we measured peak values rather than timing.

The presence of asymmetric hypertrophy in nHCM patients renders geometric assumptions inaccurate in LV mass measurement. Hence, we measured MWT, which had been widely used and validated as a marker of LV hypertrophy in these patients.15,51 Furthermore, we showed that there is no relationship between exercise capacity and extent of LV hypertrophy as measured by both LV mass index and MWT (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Although nHCM patients often had normal/supranormal LVEF as measured by conventional echocardiography, STE imaging demonstrated a marked impairment of both systolic and diastolic LV function; and they were both significant determinants of exercise capacity.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the help and advice on statistics given by Dr Peter Nightingale.

References

- 1.Lele S.S., Thomson H.L., Seo H. Exercise capacity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Role of stroke volume limitation, heart rate, and diastolic filling characteristics. Circulation. 1995;92:2886–2894. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow R.O., Rosing D.R., Bacharach S.L. Effects of verapamil on left ventricular systolic function and diastolic filling in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1981;64:787–796. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh J.K., Hatle L., Tajik A.J. Diastolic heart failure can be diagnosed by comprehensive two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen D.E., Daughters G.T., Alderman E.L. Effect of volume loading, pressure loading, and inotropic stimulation on left ventricular torsion in humans. Circulation. 1991;83:1315–1326. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.4.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong S.J., Hees P.S., Huang W.M. Independent effects of preload, afterload, and contractility on left ventricular torsion. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(3 Pt 2):H1053–H1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong S.J., Hees P.S., Siu C.O. MRI assessment of LV relaxation by untwisting rate: a new isovolumic phase measure of tau. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2002–H2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notomi Y., Lysyansky P., Setser R.M. Measurement of ventricular torsion by two-dimensional ultrasound speckle tracking imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:2034–2041. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron B.J., Gottdiener J.S., Epstein S.E. Patterns and significance of distribution of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A wide angle, two dimensional echocardiographic study of 125 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1981;48:418–428. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro L.M., Kleinebenne A., McKenna W.J. The distribution of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: comparison to athletes and hypertensives. Eur Heart J. 1985;6:967–974. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce R.A., McDonough J.R. Stress testing in screening for cardiovascular disease. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1969;45:1288–1305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies N.J., Denison D.M. The measurement of metabolic gas exchange and minute volume by mass spectrometry alone. Respir Physiol. 1979;36:261–267. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(79)90029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notomi Y., Setser R.M., Shiota T. Assessment of left ventricular torsional deformation by Doppler tissue imaging: validation study with tagged magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2005;111:1141–1147. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157151.10971.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang R.M., Bierig M., Devereux R.B. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S.H., Shub C., Nobrega T.P. Two-dimensional echocardiographic calculation of left ventricular mass as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography: correlation with autopsy and M-mode echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(96)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spirito P., Bellone P., Harris K.M. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1778–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Notomi Y., Martin-Miklovic M.G., Oryszak S.J. Enhanced ventricular untwisting during exercise: a mechanistic manifestation of elastic recoil described by Doppler tissue imaging. Circulation. 2006;113:2524–2533. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.596502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker M., Hoffmann R., Kuhl H.P. Analysis of myocardial deformation based on ultrasonic pixel tracking to determine transmurality in chronic myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2560–2566. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helle-Valle T., Crosby J., Edvardsen T. New noninvasive method for assessment of left ventricular rotation: speckle tracking echocardiography. Circulation. 2005;112:3149–3156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisner S.A., Lysyansky P., Agmon Y. Global longitudinal strain: a novel index of left ventricular systolic function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:630–633. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shivu G.N., Abozguia K., Phan T.T. Increased left ventricular torsion in uncomplicated type 1 diabetes: the role of coronary microvascular function. Diabetes Care. 2009 doi: 10.2337/dc09-0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phan T.T., Shivu G.N., Abozguia K. Left ventricular torsion and strain patterns in heart failure with normal ejection fraction are similar to age-related changes. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohs L.N., Trahey G.E. A novel method for angle independent ultrasonic imaging of blood flow and tissue motion. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1991;38:280–286. doi: 10.1109/10.133210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amundsen B.H., Helle-Valle T., Edvardsen T. Noninvasive myocardial strain measurement by speckle tracking echocardiography: validation against sonomicrometry and tagged magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serri K., Reant P., Lafitte M. Global and regional myocardial function quantification by two-dimensional strain: application in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagueh S.F., Bachinski L.L., Meyer D. Tissue Doppler imaging consistently detects myocardial abnormalities in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and provides a novel means for an early diagnosis before and independently of hypertrophy. Circulation. 2001;104:128–130. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carasso S., Yang H., Woo A. Systolic myocardial mechanics in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: novel concepts and implications for clinical status. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maier S.E., Fischer S.E., McKinnon G.C. Evaluation of left ventricular segmental wall motion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with myocardial tagging. Circulation. 1992;86:1919–1928. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beache G.M., Wedeen V.J., Weisskoff R.M. Intramural mechanics in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: functional mapping with strain-rate MR imaging. Radiology. 1995;197:117–124. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maron B.J., Epstein S.E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Recent observations regarding the specificity of three hallmarks of the disease: asymmetric septal hypertrophy, septal disorganization and systolic anterior motion of the anterior mitral leaflet. Am J Cardiol. 1980;45:141–154. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nihoyannopoulos P., Karatasakis G., Frenneaux M. Diastolic function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: relation to exercise capacity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:536–540. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro L.M., Gibson D.G. Patterns of diastolic dysfunction in left ventricular hypertrophy. Br Heart J. 1988;59:438–445. doi: 10.1136/hrt.59.4.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spirito P., Maron B.J., Chiarella F. Diastolic abnormalities in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: relation to magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1985;72:310–316. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagueh S.F., Kopelen H.A., Lim D.S. Tissue Doppler imaging consistently detects myocardial contraction and relaxation abnormalities, irrespective of cardiac hypertrophy, in a transgenic rabbit model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;102:1346–1350. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.12.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spirito P., Maron B.J. Relation between extent of left ventricular hypertrophy and occurrence of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)92820-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanderson J.E., Gibson D.G., Brown D.J. Left ventricular filling in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. An angiographic study. Br Heart J. 1977;39:661–670. doi: 10.1136/hrt.39.6.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanderson J.E., Wang M., Yu C.M. Tissue Doppler imaging for predicting outcome in patients with cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:458–463. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000133110.58863.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gwathmey J.K., Warren S.E., Briggs G.M. Diastolic dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Effect on active force generation during systole. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1023–1031. doi: 10.1172/JCI115061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betocchi S., Hess O.M., Losi M.A. Regional left ventricular mechanics in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1993;88(5 Pt 1):2206–2214. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashrafian H., Watkins H. Myocardial dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;104:E165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abozguia K., Clarke K., Lee L. Modification of myocardial substrate use as a therapy for heart failure. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:490–498. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abozguia K., Nallur Shivu G., Phan T.T. Potential of metabolic agents as adjunct therapies in heart failure. Future Cardiol. 2007;3:525–535. doi: 10.2217/14796678.3.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie M.X., Zhang L., Lu Q. Left ventricular rotation and twist in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy evaluated by two-dimensional ultrasound speckle-tracking imaging. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2008;30:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knudtson M.L., Galbraith P.D., Hildebrand K.L. Dynamics of left ventricular apex rotation during angioplasty: a sensitive index of ischemic dysfunction. Circulation. 1997;96:801–808. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helmes M., Lim C.C., Liao R. Titin determines the Frank-Starling relation in early diastole. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:97–110. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashikaga H., Criscione J.C., Omens J.H. Transmural left ventricular mechanics underlying torsional recoil during relaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H640–H647. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00575.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rademakers F.E., Buchalter M.B., Rogers W.J. Dissociation between left ventricular untwisting and filling. Accentuation by catecholamines. Circulation. 1992;85:1572–1581. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibson D.G., Sanderson J.E., Traill T.A. Regional left ventricular wall movement in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Br Heart J. 1978;40:1327–1333. doi: 10.1136/hrt.40.12.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Notomi Y., Popovic Z.B., Yamada H. Ventricular untwisting: a temporal link between left ventricular relaxation and suction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H505–H513. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00975.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Opdahl A., Helle-Valle T., Remme E.W. Apical rotation by speckle tracking echocardiography: a simplified bedside index of left ventricular twist. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeuchi M., Borden W.B., Nakai H. Reduced and delayed untwisting of the left ventricle in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy: a study using two-dimensional speckle tracking imaging. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2756–2762. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olivotto I., Gistri R., Petrone P. Maximum left ventricular thickness and risk of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02713-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]