Summary

The Type I R–M system EcoR124I is encoded by three genes. HsdM is responsible for modification (DNA methylation), HsdS for DNA sequence specificity and HsdR for restriction endonuclease activity. The trimeric methyltransferase (M2S) recognises the asymmetric sequence (GAAN6RTCG). An engineered R–M system, denoted EcoR124INT, has two copies of the N-terminal domain of the HsdS subunit of EcoR124I, instead of a single S subunit with two domains, and recognises the symmetrical sequence GAAN7TTC. We investigate the methyltransferase activity of EcoR124INT, characterise the enzyme and its subunits by analytical ultracentrifugation and obtain low-resolution structural models from small-angle neutron scattering experiments using contrast variation and selective deuteration of subunits.

Keywords: DNA methyltransferase, DNA methylation, restriction–modification, sedimentation velocity, small-angle neutron scattering

Introduction

Restriction–modification (R–M) enzymes provide a bacterial defence mechanism against foreign DNA. Hemi-methylated host DNA is fully methylated at specific sequences by a methyltransferase (MTase), thus protecting its DNA from restriction by the accompanying endonuclease (ENase). Foreign DNA is unmethylated at these sites and is cleaved.1, 2

Type I R–M systems are hetero-oligomeric enzymes encoded by three hsd (host specificity of DNA) genes encoding three polypeptides: HsdS, responsible for DNA recognition, HsdM for DNA modification and HsdR for cleavage. The ENase requires all three subunits: M, S and R while the MTase requires just the M and S subunits. For enzyme activity, the MTase is dependent upon S-adenosylmethionine, while the ENase in addition requires Mg2+ and ATP. All Type I R–M systems methylate a specific adenine at the N6 position (for reviews, see Ref. 3).

DNA sequence alignments of the S subunits of Type I R–M systems have shown the presence of two variable regions that form target recognition domains (TRDs), each recognising one-half of the bipartite DNA recognition motif, and two conserved regions that are believed to interact with the M subunit. The DNA recognition sequence of Type I R–M systems is, in general, asymmetric, and the two TRDs within the S subunit have different amino acid sequences. Typically, each of the DNA sequence half-sites is 3–5 bp in length, separated by a nonspecific spacer region (5–8 bp). On the basis of internal sequence homologies, a circular arrangement of the domains of the S subunit was suggested, which brings the N- and C-termini into close proximity.4 Circular permutations of the sequence of the N- and C-terminal conserved regions of the S subunit of EcoAI support this notion.5

Crystal structures have been reported for the Type I S subunits of Mycoplasma genitalium [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 1YDX] and Methanococcus jannaschii (PDB code: 1YF2), confirming the proximity of the N- and C-termini and in each case showing a hetero-dimeric structure held together by the interaction of coiled-coil regions.6, 7 Crystal structures are also available in the protein structure database for two M subunits—EcoKI (PDB code: 2AR0) and StySJI (PDB code: 2OKC), although both structures have significant regions of missing density (and neither has been published). More recently, structures of the R subunits of EcoR124I8 (PDB code: 2W00), Vibrio vulnificus YJ0169 (PDB code: 3H1T), and Bacteroides fragalis (PDB code: 3EVY; unpublished results) have been reported. No crystal structures have yet been reported for either a Type I MTase or an ENase, although various models have been proposed.10, 11, 12

EcoR124I is one of the best studied Type I R–M system; it recognises the asymmetric DNA sequence GAAN6RTCG.13, 14 Structural analysis of the full-length S subunit of EcoR124I has been hampered by the insolubility of this subunit unless co-expressed with the M subunit.15, 16 Various fragments of the hsdS gene were generated by PCR and over-expressed to allow further characterisation of the S subunit,17 and two of these proteins were found to be soluble. One of these (hereafter denoted SNT) corresponds to residues 1–215 of the parent S subunit and contains the N-terminal TRD and the central conserved region. This domain recognises the GAA of the parent recognition sequence and dimerises to recognise the symmetrical sequence GAAN7TTC.18, 19 As this system is based on the N-terminal domain of the specificity subunit of EcoR124I, it will be designated EcoR124INT, although to date there has been no characterisation of its enzyme activity. There are clear similarities between M.EcoR124INT and M.AhdI, in which the S subunits each containing one TRD combine to form a homodimer, giving rise to a symmetrical recognition sequence.20, 21 Although the AhdI MTase has all the hallmarks of a Type I MTase, it should be noted that the AhdI ENase is quite unrelated to the AhdI MTase and, in this respect, resembles a Type II ENase.

Here, we investigate the methylation activity of the engineered MTase, M.EcoR124INT. We also show that M.EcoR124INT is inhibited by ocr (“overcome classical restriction”), a small negatively charged protein that mimics DNA and whose biological role is to inhibit Type I R–M enzymes by competitive inhibition at the DNA binding site.22, 23 M.EcoR124INT and its component subunits have been further characterised by analytical ultracentrifugation. Finally, small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) experiments employing selective deuteration and contrast variation have allowed us to obtain low-resolution structural models of the MTase and to determine the spatial location of its subunits.

Results and Discussion

Methylation activity

M.EcoR124INT was reconstituted from its individual subunits, and the complex was further purified as outlined in Materials and Methods. To assess the in vitro methylation activity of M.EcoR124INT, we developed an assay, based on the prevention or otherwise of DNA cleavage by EcoRI. A plasmid was constructed in which the N7 spacer within the M.EcoR124INT recognition sequence (GAAN7TTC) was designed to contain a TTC sequence next to the 5′-GAA. This created an EcoRI recognition site (GAATTC), allowing the N6 methylation status of the second adenine to be monitored. In the absence of methylation, the 3127-bp linearised DNA substrate is digested by EcoRI into two DNA fragments of length 1834 bp and 1293 bp. These experiments showed that M.EcoR124INT had methylation activity that was independent of MgCl2 (Fig. 1a and b).

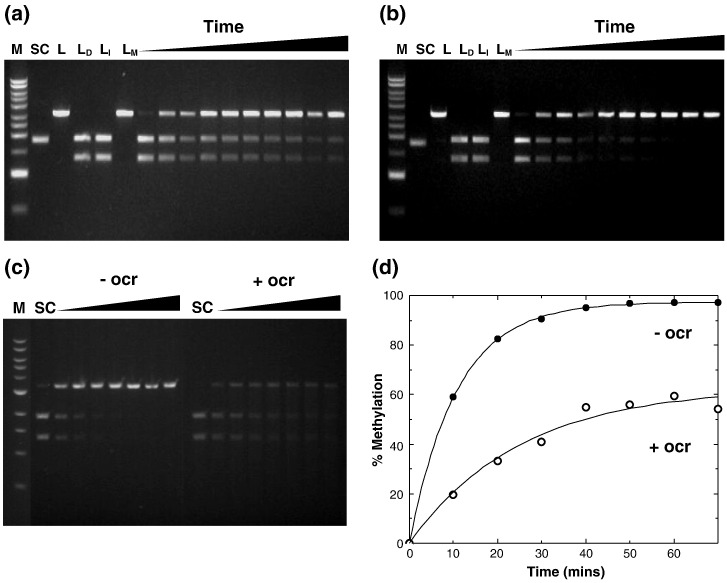

Fig. 1.

Methylation protection assays. (a) In the presence of 10 mM MgCl2. (b) In the absence of MgCl2. (c) MTase inhibition by ocr. In the presence and absence of an equimolar ratio of ocr in a buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2. (d) Enzyme progression curves for (c). Filled circles and open circles represent percent methylation in the absence and presence of ocr, respectively. All reactions were carried out at 37 °C and contained 2.5 nM DNA and 50 nM MTase [plus 50 nM ocr dimer, in the case of (c)]. M, 1 kb DNA Ladder (NEB or GE Healthcare); SC, supercoiled DNA; L, linear DNA, LD, linearised DNA followed by digestion with EcoRI; LI, inactivated M.EcoR124INT incubated with linearised DNA followed by EcoRI digestion; LM, linearised methylated DNA. Lanes beneath the triangles show aliquots taken at 10-min intervals and digested with EcoRI.

Inhibition by the ocr protein in vitro was then investigated. Previous studies have shown that ocr inhibits the DNA methylation, restriction, and ATPase activity of other Type I R–M systems such as EcoKI and EcoBI.22 The assay was conducted in the same way as the MTase assay, except that ocr was first incubated with M.EcoR124INT prior to DNA addition. It was found that at equimolar ratios of an ocr (dimer) to M.EcoR124INT, there was approximately 50% MTase inhibition (Fig. 1c). Since ocr typically inhibits Type I MTases, in this respect, the engineered enzyme behaves similarly to other Type I enzymes.

Hydrodynamic characterisation

In order to determine the molecular mass and stoichiometry in solution, we carried out sedimentation velocity (SV) and sedimentation equilibrium (SE) experiments on M.EcoR124INT and its constituent subunits. In each case, the sedimentation profiles were fitted with c(s) analysis using SEDFIT.24

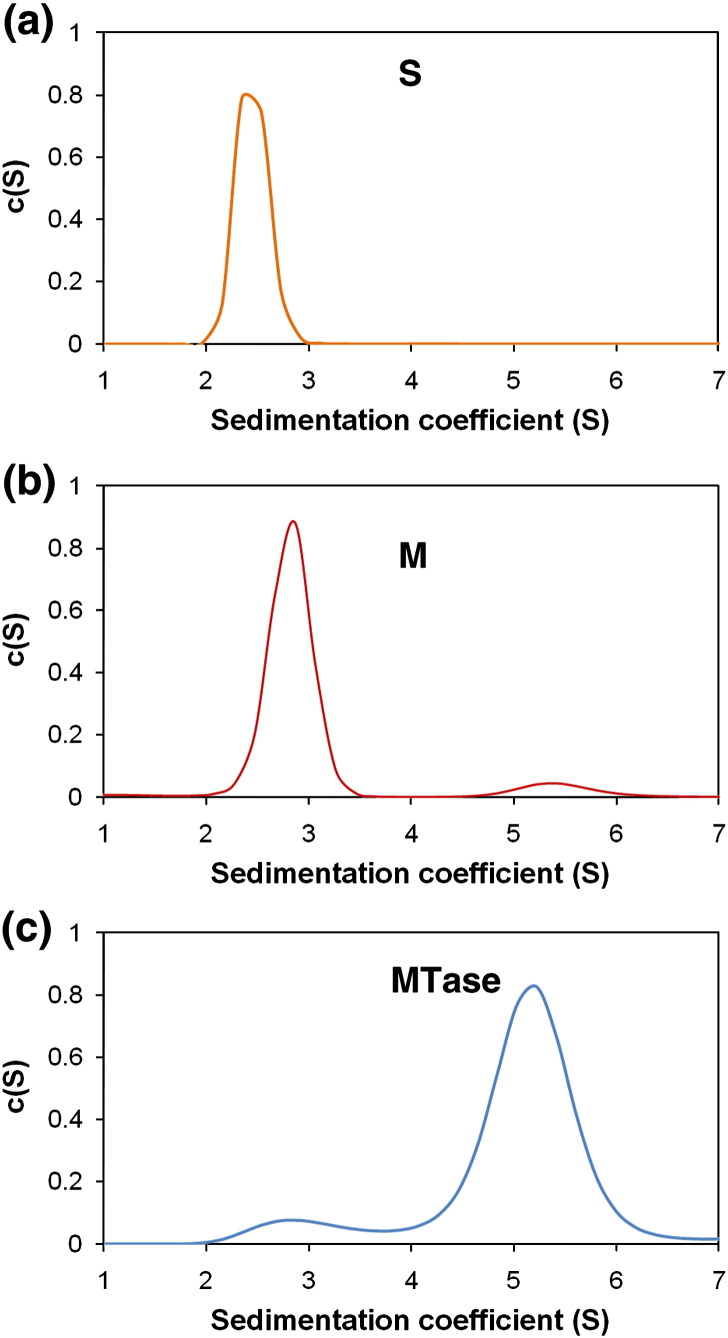

SV experiments were first carried out on the SNT and M subunits, which both sedimented essentially as a single species. Experimental sedimentation coefficients (s⁎) of 2.5 S and 2.9 S for SNT and M, respectively, were obtained from the c(s) distribution profiles (Fig. 2a and b), which, when corrected, gave s20,w values of 3.3 S and 3.9 S, respectively. Following transformation to a c(M) distribution, experimental Mr values of 49,000 and 57,000 were obtained for SNT and M, respectively, in excellent agreement with the theoretical Mr for a SNT dimer (2 × 24,850) and an M monomer (58,000).

Fig. 2.

SV analysis of the MTase and its subunits. The c(s) distribution plots are shown for (a) SNT at 25 μM, (b) M at 6 μM and (c) M.EcoR124INT at 2.6 μM. All experiments were performed at 30,000 rpm (in a Beckman Coulter An50 Ti analytical rotor), at 10 °C in buffer A, scanning every 12 min, at 280 nm.

SV was then performed on M.EcoR124INT (Fig. 2c). Again, the sample was seen to exist almost entirely as a single species, with an s⁎ of 5.3 S and an s20,w of 7.0 S, which are in reasonable agreement with values of 5.1 S and 6.7 S for the WT MTase (data not shown), suggesting that the two enzymes have a similar shape and structural organization. The Mr obtained from the c(M) distribution was 160,000, which is in close agreement with the expected value for a hetero-tetramer consisting of two SNT and two M subunits (165,680). Table 1 summarises the hydrodynamic parameters that were obtained from SV.

Table 1.

AUC parameters for M.EcoR124INT and its individual subunits

| Species | Sa | s20,wb | Mrc | f/fod | D20,we |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNT | 2.5 | 3.3 (3.6) | 49,000 (49,700) | 1.48 | 6.2 (6.4) |

| M | 2.9 | 3.9 (3.6) | 57,000 (58,000) | 1.39 | 6.1 (5.6) |

| MTase | 5.3 | 7.0 (6.7) | 160,000 (165,680) | 1.55 | 3.9 (3.7) |

S and D values predicted from the ab initio models using HYDROPRO are shown in parentheses (taking the SNT dimer and the M monomer). Theoretical molecular weights for an SNT dimer and an M monomer are also shown in parentheses.

Experimental sedimentation coefficient (in Svedbergs).

Corrected sedimentation coefficient (in Svedbergs).

Experimental Mr.

Frictional ratio calculated assuming 0.4 g water per gram of protein.

Experimental diffusion coefficient (× 10− 7 cm2 s− 1).

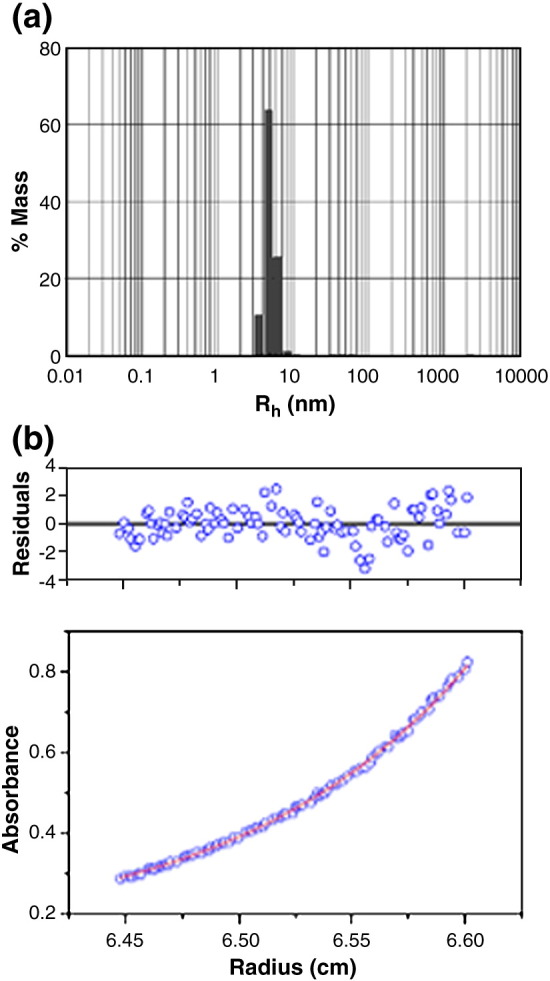

SE was conducted within a concentration range of 2.5 to 8.8 μM to obtain a more accurate value for the molecular mass in solution of the MTase. The data fitted well to a single ideal species model, as noted from the random distribution of the residuals about zero (a representative fit is shown in Fig. 3b). The experimental Mr was 163,000, using a global fit from runs carried out at 6500 rpm and 8500 rpm, again in good agreement with the theoretical Mr for a hetero-tetramer of 165,680.

Fig. 3.

(a) DLS of M.EcoR124INT at a concentration of 5 μM at 10 °C. A hydrodynamic radius of 5 nm with a polydispersity of 0.87 nm (7.4%) was obtained. (b) SE of M.EcoR124INT. Shown is an example fit from data collected at 8500 rpm (using a Beckman Coulter An50 Ti analytical rotor), scanned at 276 nm (after 21 h), at a concentration of 5 μM at 10 °C. The data were fitted to a single ideal species model and yielded an apparent Mr of 162,100. The top panel shows the residual error between the fitted and experimental values.

Small-angle neutron scattering

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was routinely used to check for mono-dispersity of the MTase, where a single peak with a hydrodynamic radius of approximately 4.5–5.0 nm was typically found (Fig. 3a). Having confirmed that the M.EcoR124INT complex was mono-disperse and with no tendency to aggregate, we were able to carry out SANS experiments. SANS allows the low-resolution structure of macromolecular complexes to be determined. If specific subunits can be deuterated, then contrast variation can be used to allow the location of the subunits to be established. Unlike the WT enzyme, M.EcoR124INT can be reconstituted from its individual subunits, thus allowing the deuteration of specific subunits, which can then be matched out in buffers containing D2O.

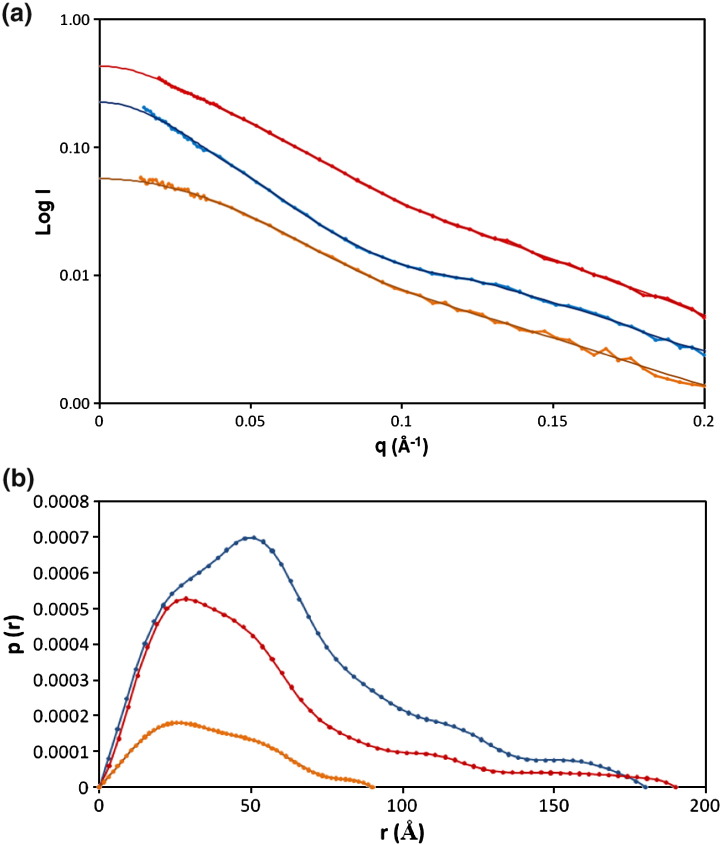

Scattering curves were first collected for the fully hydrogenated M.EcoR124INT in 100% D2O (Fig. 4a). Following the construction of Guinier plots, a radius of gyration (Rg) of 52.9 Å was obtained. The scattering curve was subsequently transformed to a distance distribution function, p(r), and the maximum dimension, Dmax [i.e., when p(r) = 0], was estimated to be 180 Å for the MTase (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Small-angle neutron scattering. (a) SANS scattering curves for M.EcoR124INT measured in 100% D2O (blue), M.EcoR124INT containing deuterated SNT measured in 40% D2O (orange) and M.EcoR124INT containing deuterated SNT measured in 100% D2O (red). In each case, the continuous curve is the corresponding fit from GNOM. (b) Distance distribution functions obtained by transformation of the data shown in (a).

Scattering data were then measured for a complex of M.EcoR124INT composed of deuterated SNT and hydrogenated M subunits. In 40% D2O, we obtained an Rg of 32.4 Å and a Dmax of 90 Å; these values represent the structure of the SNT subunits in the complex, since the M subunits are matched out. For the same sample in 100% D2O, values of Rg = 50.1 Å and Dmax = 190 Å were obtained; these values correspond to the structure of the two M subunits in the complex, as the deuterated SNT subunits are now matched out. Our results (Table 2) clearly indicate that the M subunits extend towards the periphery of the complex, whereas the S subunits are located more centrally.

Table 2.

SANS parameters for M.EcoR124INT and its subunits in situ

M.EcoR124INT measured in 100% D2O.

M.EcoR124INT with deuterated SNT subunits measured in 40% D2O.

M.EcoR124INT with deuterated SNT subunits measured in 100% D2O.

Since X-ray crystal structures are available for homologues of each of the subunits of M.EcoR124INT, it is instructive to compare the predicted and experimental SANS parameters for the subunits within the MTase. Using HYDROPRO to calculate Rg and Dmax from the crystal structure of the HsdS dimer of M. jannaschii (PDB code: 1YF2), we obtain values of 30.5 Å and 91 Å, respectively, which compare very well with the experimental values from SANS (32.5 Å and 90 Å). Likewise, the predicted scattering curve from the crystal structure fits the data extremely well up to Q = 0.14 Å− 1 (see Supplementary Fig. S1a). In contrast, the predicted Rg and Dmax for the EcoKI HsdM dimer (40.5 Å and 157 Å, respectively) differ significantly from the experimental SANS parameters (50.1 Å and 190 Å) and the predicted scattering curve is not remotely similar to the experimental curve (see Supplementary Fig. S1b). The poor correspondence between the EcoKI M dimer in the crystal and the experimental SANS data for M.EcoR124INT is not unexpected as (1) the sequence homology between the M subunits of EcoR124I and EcoKI is not strong, (2) a significant fraction of the electron density map of the EcoKI M subunit is missing and (3) the EcoKI dimer of M subunits in the unit cell may not have the same interactions in the MTase—in fact, for EcoR124INT, we show that the M subunit exists as a monomer in solution.

Low-resolution ab initio models were then constructed using DAMMIN to model the SANS data (Fig. 5). Typically, for each experiment, 20 independent runs of DAMMIN were performed, and the resulting models were filtered and averaged by DAMAVER (see Materials and Methods). This process was repeated a number of times, and the final ab initio models obtained in each case were found to have the same general features.

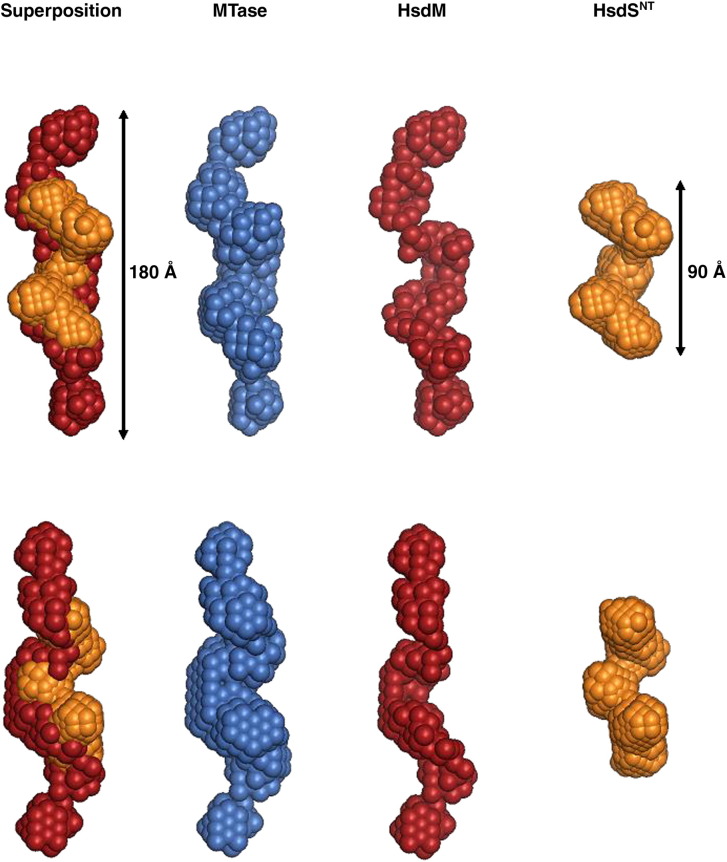

Fig. 5.

Ab initio models of M.EcoR124INT (blue), and the M and SNT subunits in situ (red and orange, respectively). Twenty DAMMIN models were averaged using DAMAVER and models were aligned using SUPCOMB. In all cases, P2 symmetry was imposed. The two rows show mutually perpendicular views of the structures, rotated by 90° around the y-axis.

The ab initio model for the shape of M.EcoR124INT was determined by analysis of the data from the fully hydrogenated enzyme measured in D2O buffer. The ab initio model for the S subunits was determined by analysis of scattering data obtained from the MTase reconstituted with deuterated SNT subunits and measured in 40% D2O buffer. The ab initio shape determined for SNT reveals that the two subunits dimerise into a typical Z-shaped structure resembling the S subunits of both M. genitalium and M. jannaschii.6, 7 The model of the M subunits was obtained by subtracting the model of the S subunits from that of M.EcoR124INT.

The program HYDROPRO was then used to calculate hydrodynamic parameters for each of the ab initio models. Table 1 compares the hydrodynamic parameters from AUC with those predicted from the ab initio models of the MTase and its subunits. Considering the low resolution of the bead models, the agreement between predicted and experimental values of sedimentation coefficient and diffusion coefficient is very good (within 3–9%). This provides further evidence to support the ab initio model of the EcoR124INT MTase and indicates that the subunits do not undergo any large-scale structural changes on forming the MTase.

We attempted to fit crystal structures of homologous subunits (the M dimer of EcoKI and the S subunit of M. jannaschii) to the ab initio models of the M and S components of EcoR124INT. As expected, the fit to the S subunit model was good, but the fit to the M subunit model was less so (see Supplementary Fig. S2) and a unique orientation could not be defined with any certainty for the latter, even if the location and the orientation of the individual M subunits were allowed to vary. The resolution of the technique was not considered adequate to fit the M and SNT subunits simultaneously to the ab initio model of M.EcoR124INT as there are numerous ways of fitting these subunits together.

The fit between the ab initio model of the SNT dimer and the crystal structure shows that the two half subunits of the latter dimerise to form a similar structure to that of an intact S subunit, which appears to be well conserved at the structural level between unrelated R–M systems. In contrast, the EcoKI dimer, as found in the crystal structure, does not match the M subunit organisation within M.EcoR124INT. The results of the SANS analysis suggest that the M subunits are linked essentially end to end in the MTase, making at most rather limited contacts at the centre of the complex. Even though the free M subunits exist as monomers in solution, there may be relatively weak protein–protein contacts between them in the MTase, presumably stabilised by interactions with the S subunits, which form a very stable dimer.

The overall low-resolution structure we have obtained for M.EcoR124INT resembles that of the MTase, M.AhdI, as determined by SANS.21 The interactions of the M subunits in the ab initio model are rather different to those proposed for M.EcoKI on the basis of electron microscopy10 or for M.EcoR124I on the basis of molecular modelling.11 However, it should be noted that those models were for complexes formed with DNA (or the DNA mimic, ocr) and such structures are likely to be much more compact than the free protein, which exists in the “open” conformation.25

Materials and Methods

Protein Purification

The expression and purification of SNT were carried out as previously published.17 For the M subunit, a 5-mL starter culture was grown until OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) reached 0.6 and was used to inoculate flasks containing 500 mL 2 × YT, which were also grown to OD600 of 0.6. The M subunit was expressed overnight following induction with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 39,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. The cell pellets were stored at − 20 °C. The pellet was resuspended at 4 °C in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 25% w/v sucrose, and 1 mM Na2EDTA (disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), followed by sonication and centrifugation at 39,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The clarified lysate was supplemented with protamine sulphate (Sigma) to a final concentration of 20 mg/mL and 500 mM NaCl, mixed slowly at 4 °C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 39,000g for 20 min at 4°C.

The M subunit was finally purified using a HiTrap™ desalting (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated in buffer A (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM Na2EDTA). This step produces pure M subunit since it unexpectedly (but reproducibly) binds to the column during buffer exchange and elutes with the leading edge of the salt peak; in contrast, the contaminating proteins elute, as expected, in the void volume. The M subunit was subsequently dialysed into buffer A and remained soluble and mono-disperse as judged by analytical ultracentrifugation.

The multisubunit M.EcoR124INT enzyme was formed by incubation of purified SNT and M subunits for 30 min at 4 °C. The sample was applied to a 5-mL HiTrap™ heparin column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer A, and a linear gradient of NaCl (0.1 M to 2.0 M) was applied at 1 mL/min over 10 column volumes. The intact M.EcoR124INT eluted at approximately 250 mM NaCl.

Methylation and inhibition assays

A 30-bp DNA duplex incorporating the sequence GAATTCN4TTC (which includes the recognition sites for both M.EcoR124INT and EcoRI ) was blunt-end ligated into the SmaI site of the plasmid pUC119 EcoRI− (which lacked any EcoRI sites—C. Dutta, personal communication) to form the plasmid pUC119/EcoR124INT. The orientation, correct number of inserts and the lack of mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing around the inserted sequence. Following linearization of this plasmid with XmnI, we incubated the samples with M.EcoR124INT at 37 °C. Fifteen-microliter aliquots were removed at various times and heat inactivated at 65 °C for 20 min. After cooling on ice for 10 min, each 15-μL sample was challenged with EcoRI and incubated for a further 60 min at 37 °C. The products of the reaction were run on a 0.8% agarose gel. The ocr inhibition assay was carried out in the same way, except that ocr was added at the appropriate molar ratio to M.EcoR124INT prior to the addition of DNA. Agarose gels were digitally photographed using a FujiFilm FLA-5000 phosphorimager and quantified using Image Gauge.

Sedimentation velocity

SV experiments were carried out in a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Four hundred microliters of sample (either SNT, M or M.EcoR124INT) and 425 μL of buffer A were loaded into the corresponding sectors of a double-sector cell of 12 mm optical path length. The cells were loaded into an An50 Ti analytical rotor, which had been left overnight at 4 °C and transferred to the centrifuge, where it was left to equilibrate. The rotor was accelerated to 30,000 rpm, and readings of absorbance versus radial distance were taken every 12 min at 280 nm at 10 °C. The raw data were analysed using the program SEDFIT,24 using radial data within the range 6.06–7.00 cm. Partial specific volumes and buffer densities were calculated using the program SEDNTERP and corrected for temperature.26 The experimental sedimentation coefficients obtained from the c(s) distribution plot were finally corrected for temperature and solvent using SEDNTERP so that a s20,w value could be obtained.

Sedimentation equilibrium

SE was carried out in a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge. Experiments were performed in six-channel cells of 12 mm optical path length, using 90 μL of sample (M.EcoR124INT) at a protein concentration range from 2.5 to 8.8 μM. One hundred microliters of buffer was loaded into the corresponding control channel. The cells were loaded into an An50 Ti analytical rotor at 4°C. The rotor was accelerated to 6500 rpm and 8,500 rpm, and scans of absorbance versus radial displacement were measured at a wavelength of 276 nm, at a resolution of 0.001 cm at 0, 15, 18 and 21 h. Finally, a meniscus depletion was carried out at 40,000 rpm.

Dynamic light scattering

DLS was performed with purified MTase at 5 mM, at 10°C in buffer A, using a Protein Solutions DynaPro MSTC800 light-scattering instrument. The results from 30 measurements were averaged, and values for the hydrodynamic radius, Rh, and polydispersity were obtained. The experimental molecular mass, Mr, was estimated using the standard molecular weight model (Dynamics V5, Protein Solutions).

Small-angle neutron scattering

Sample preparation

The SNT subunit was deuterated by expression of the SNT gene from pET-21a in BL21 (DE3) cells. Enfors minimal medium containing 85% D2O with hydrogenated glycerol as the carbon source was used to give a 75% deuteration level, such that the protein had a contrast match point equivalent to 100% D2O. The M.EcoR124INT complex was formed either as the fully hydrogenated enzyme or as a partially deuterated complex by mixing the appropriate subunits, that is, with both SNT and M hydrogenated, or with deuterated SNT and hydrogenated M. The complex was purified as described above. Complexes were then dialysed into buffer A in varying H2O/D2O ratios.

SANS measurements

Data were collected using the D22 diffractometer at the ILL using two detector distances, 2 m and 8 m, covering a Q range of 0.008–0.35 Å− 1 at a wavelength of 6 Å, where Q is the scattering vector (4πsinθ/λ). Scattering data were collected from a 96 cm × 96 cm detector with a pixel size of 7.5 mm × 7.5 mm. Data reduction was performed using the GRASansP software (Dewhurst, 2006†). Modelling of the SANS data was performed using the ATSAS software package.27 Data from both distances were merged over the range 0.013 to 0.2 Å− 1 and evaluated using PRIMUS.28 At low angle, the scattering intensities I(Q) can be described by the Guinier approximation, I(Q) = I(0) exp 1/3 Rg2Q2, where Rg is the radius if gyration. The isotropic scattering intensity I(Q) was transformed to the particle distance distribution function, p(r), using the program GNOM,29 which was used to estimate the particle maximum dimensions Dmax. Scattering curves were then generated by back transformation of each of these p(r) functions and compared to the experimental data. The value of Dmax was confirmed when the Rg obtained from the p(r) distribution was equal to that obtained from the Guinier plot.

Ab initio modelling

Once the p(r) curves had been obtained for SNT, M and the MTase, DAMMIN was used to create low-resolution ab initio models.27 In all cases, P2 symmetry was imposed. The packing radii of the dummy atoms used for the modelling of the MTase and the M and SNT subunits were 4.6 Å, 4.4 Å and 2.2 Å, respectively. Penalty weights for the looseness and disconnectivity were set to 3 × 10− 3 and a peripheral penalty weight of 0.3 was used. The final root-mean-square errors (chi) for all models were between 1.0 and 1.5. Typically, 20 models were aligned, averaged and filtered using DAMAVER, discarding any models that had a normalized spatial distribution higher than that of the mean plus twice the variation.30 The number of dummy atoms in the averaged models for the MTase, the M subunits and the SNT subunits were 482, 661 and 394, respectively. Ab initio models were overlaid using the program SUPCOMB, taking the MTase ab initio model as a template.31 All models were visualized using the program PyMOL.

Hydrodynamic parameters for each model were calculated using the program HYDROPRO.32 Small-angle scattering curves were generated from atomic resolution models using the program CRYSON.33

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 080304/Z/06/Z). We thank the Institut Laue-Langevin for providing access to neutron diffraction facilities. The authors also acknowledge the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (grants GR/R99393/01 and EP/C015452/1), and the staff of the Institut Laue Langevin–European Molecular Biology Laboratory Deuteration Laboratory, for providing facilities for protein deuteration. We are grateful to Dr. John McGeehan for helpful discussions.

Edited by K. Morikawa

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.008

Appendix A.

Simulated scattering data from atomic structures (blue curves) versus experimental SANS data (red circles). (a) M.EcoR124INT containing deuterated SNT measured in 40% D2O together with the simulated scattering data from the crystal structure of the HsdS subunit of M. jannaschii (PDB code: 1YF2). (b) M.EcoR124INT containing deuterated SNT measured in 100% D2O, together with the simulated scattering data from the crystal structure of the HsdM dimer of EcoKI (PDB code: 2AR0).

Overlays of related crystal structures (represented as ribbons) onto the ab initio models of the subunits of M.EcoR124INT. (a) Two copies of the M subunit, taken from the EcoKI crystal structure (PBD code: 2AR0) superimposed on the ab initio model of the HsdM dimer. (b) Crystal structure of the S subunit of M. jannaschii (PBD code: 1YF2) superimposed on the ab initio model of the SNT dimer.

References

- 1.Wilson G.G. Organization of restriction–modification systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2539–2566. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.10.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickle T.A., Kruger D.H. Biology of DNA restriction. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:434–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.434-450.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao D.N., Saha S., Krishnamurthy V. ATP-dependent restriction enzymes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;64:1–63. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)64001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kneale G.G. Symmetrical model for the domain-structure of type-I DNA methyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;243:1–5. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janscak P., Bickle T.A. The DNA recognition subunit of the type I restriction–modification enzyme EcoAI tolerates circular permutions of its polypeptide chain. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:937–948. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calisto B.M., Pich O.Q., Pinol J., Fita I., Querol E., Carpena X. Crystal structure of a putative type I restriction–modification S subunit from Mycoplasma genitalium. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J.S., DeGiovanni A., Jancarik J., Adams P.D., Yokota H., Kim R., Kim S.H. Crystal structure of DNA sequence specificity subunit of a type I restriction–modification enzyme and its functional implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3248–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409851102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapkouski M., Panjikar S., Janscak P., Smatanova I.K., Carey J., Ettrich R., Csefalvay E. Structure of the motor subunit of type I restriction–modification complex EcoR124I. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;16:94–95. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uyen N.T., Park S.Y., Choi J.W., Lee H.J., Nishi K., Kim J.S. The fragment structure of a putative HsdR subunit of a type I restriction enzyme from Vibrio vulnificus YJ016: implications for DNA restriction and translocation activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6960–6969. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennaway C.K., Obarska-Kosinska A., White J.H., Tuszynska I., Cooper L.P., Bujnicki J.M., et al. The structure of M.EcoKI Type I DNA methyltransferase with a DNA mimic antirestriction protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:762–770. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obarska A., Blundell A., Feder M., Vejsadova S., Sisakova E., Weiserova M., et al. Structural model for the multi-subunit Type IC restriction–modification DNA methyltransferase M. EcoR124I in complex with DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1992–2005. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies G.P., Martin I., Sturrock S.S., Cronshaw A., Murray N.E., Dryden D.T.F. On the structure and operation of type I DNA restriction enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:565–579. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price C., Shepherd J.C.W., Bickle T.A. DNA recognition by a new family of type I restriction enzymes: a unique relationship between two different DNA specificities. EMBO J. 1987;6:1493–1498. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor I., Watts D., Kneale G. Substrate recognition and selectivity in the type-IC DNA modification methylase M.EcoR124I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4929–4935. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.21.4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel J., Taylor I., Dutta C.F., Kneale G., Firman K. High-level expression of the cloned genes encoding the subunits of and intact DNA methyltransferase, M.EcoR124I. Gene. 1992;112:21–27. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor I., Patel J., Firman K., Kneale G.G. Purification and biochemical-characterization of the EcoR124 type-I modification methylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:179–186. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith M.A., Mernagh D.R., Kneale G.G. Expression and characterisation of the N-terminal fragment of the HsdS subunit of M.EcoR124I. Biol. Chem. 1998;379:505–509. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.4-5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abadjieva A., Patel J., Webb M., Zinkevich V., Firman K. A deletion mutant of the type-IC restriction-endonuclease EcoR124I expressing a novel DNA specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4435–4443. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.19.4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith M.A., Read C.M., Kneale G.G. Domain structure and subunit interactions in the type I DNA methyltransferase M.EcoR124I. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:41–50. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marks P., McGeehan J.E., Kneale G.G. A novel strategy for the expression and purification of the DNA methyltransferase, M.AhdI. Protein Expr. Purif. 2004;37:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callow P., Sukhodub A., Taylor J.E.N., Kneale G.G. Shape and subunit organisation of the DNA methyltransferase M.AhdI by small-angle neutron scattering. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandyopadhyay P.K., Studier F.W., Hamilton D.L., Yuan R. Inhibition of the type I restriction–modification enzymes EcoB and EcoK by the gene 0.3 protein of bacteriophage T7. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;182:567–578. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walkinshaw M.D., Taylor P., Sturrock S.S., Atanasiu C., Berge T., Henderson R.M., et al. Structure of Ocr from bacteriophage T7, a protein that mimics B-form DNA. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor I.A., Davis K.G., Watts D., Kneale G.G. DNA-binding induces a major structural transition in a type I methyltransferase. EMBO J. 1994;13:5772–5778. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laue T.M., Shah B.D., Ridgeway T.M., Pelletier S.L. In: Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. Harding S.E., Rowe A.J., Horton J.C., editors. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, UK: 1992. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins; pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petoukhov M.V., Volkov V.V., Svergun D.I. ATSAS 2.1, a program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006;39:277–286. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konarev P.V., Volkov V.V., Sokolova A.V., Koch M.H.J., Svergun D.I. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svergun D.I. Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1992;25:495–503. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volkov V.V., Svergun D.I. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:860–864. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozin M.B., Svergun D.I. Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2001;34:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia de la Torre J., Huertas M.L., Carrasco B. Calculation of hydrodynamic properties of globular proteins from their atomic-level structure. Biophys. J. 2000;78:719–730. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76630-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svergun D.I., Richard S., Koch M.H.J., Sayers Z., Kuprin S., Zaccai G. Protein hydration in solution: experimental observation by X-ray and neutron scattering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2267–2272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Simulated scattering data from atomic structures (blue curves) versus experimental SANS data (red circles). (a) M.EcoR124INT containing deuterated SNT measured in 40% D2O together with the simulated scattering data from the crystal structure of the HsdS subunit of M. jannaschii (PDB code: 1YF2). (b) M.EcoR124INT containing deuterated SNT measured in 100% D2O, together with the simulated scattering data from the crystal structure of the HsdM dimer of EcoKI (PDB code: 2AR0).

Overlays of related crystal structures (represented as ribbons) onto the ab initio models of the subunits of M.EcoR124INT. (a) Two copies of the M subunit, taken from the EcoKI crystal structure (PBD code: 2AR0) superimposed on the ab initio model of the HsdM dimer. (b) Crystal structure of the S subunit of M. jannaschii (PBD code: 1YF2) superimposed on the ab initio model of the SNT dimer.