Abstract

Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome, which is an age-related, generalized elastotic matrix process, currently represents the most common identifiable risk factor for open-angle glaucoma. Dysregulated expression of proinflammatory cytokines has been implicated in the initiation of various fibrotic disorders and in the pathophysiology of glaucoma. Here we investigated the presence, expression, regulation, and functional significance of proinflammatory cytokines in eyes with early and late stages of PEX syndrome/glaucoma in comparison with normal and glaucomatous control eyes using multiplex bead analysis, immunoassays, real-time PCR, Western blotting, immunohistochemistry, and cell culture models. Early stages of PEX syndrome were characterized by approximately threefold (P < 0.005) elevated interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 levels in the aqueous humor and a concomitant approximately twofold (P < 0.001) increase in mRNA expression levels in anterior segment tissues as compared with controls. In contrast, late stages of PEX syndrome/glaucoma did not differ significantly from controls. IL-6, IL-6 receptor, and phospho-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 could be mainly localized to walls of iris vessels and to the nonpigmented epithelium of ciliary processes. IL-6 and IL-8 were significantly up-regulated by ciliary epithelial cells in response to hypoxia or oxidative stress in vitro, whereas IL-6, but not IL-8, induced the expression of transforming growth factor-β1 and elastic fiber proteins. These findings support a role for a stress-induced, spatially, and temporally restricted subclinical inflammation in the onset of the fibrotic matrix process characteristic of PEX syndrome/glaucoma.

Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome is an age-related, complex, generalized disorder of the extracellular matrix (ECM) characterized by the intraocular and systemic production of an abnormal fibrillar extracellular material.1 Progressive accumulation of this material (PEX material) in the aqueous humor outflow pathways is considered the primary cause of chronic intraocular pressure elevation and glaucoma development in eyes with PEX syndrome, which is currently the most important single identifiable risk factor for open-angle glaucoma and a leading cause of blindness.2 Previous immunohistochemical and biochemical approaches have shown PEX material to represent a highly cross-linked glycoprotein-proteoglycan complex, which is mainly composed of elastic microfibrillar components, such as fibrillin-1 and latent transforming growth factor binding proteins (LTBP), as well as chaperone molecules, such as clusterin, and cross-linking enzymes, such as lysyl oxidase-like 1.3,4,5 Two nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in lysyl oxidase-like 1, coding for a key enzyme of elastic fiber formation and stabilization, represent the principal genetic risk factor for PEX syndrome and glaucoma.6 However, the frequent occurrence of the high-risk lysyl oxidase-like 1 haplotype in the general population suggests that additional genetic and/or exogenous factors are required for manifestation of the PEX-specific matrix processes. Potential comodulating factors include PEX-associated genetic variants in the gene encoding clusterin (CLU),7 elevated concentrations of fibrogenic growth factors, such as transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1),8 and various external stress factors, such as oxidative stress9 and anterior chamber hypoxia10 in the eyes of PEX patients. Although the exact molecular mechanisms responsible for the excessive production and accumulation of the abnormal PEX material still remain elusive, PEX syndrome is currently described as a genetically predisposed elastic microfibrillopathy, which may be triggered by fibrogenic stimuli, such as increased growth factor activity and/or increased stress conditions.

An increased expression of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-6, IL-8, and vascular endothelial leukocyte-adhesion molecule (ELAM)-1, in the aqueous humor and outflow pathways has been linked to glaucoma pathology.11,12,13 These findings have been suggested to reflect the activation of a tissue-specific stress response.13,14,15 Actually, apart from modulating acute inflammation and immune responses, inflammatory cytokines have been implicated in a multitude of biological processes including cytoprotection, aging, and regulation of ECM deposition/remodeling.16,17 In addition, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, and IL-6 have been shown to adopt profibrotic characteristics under certain conditions,18,19 and a series of studies substantiated the involvement of inflammatory cytokines in the pathobiology of various fibrotic conditions including pulmonary fibrosis and systemic sclerosis.18,20,21 Interestingly, in systemic sclerosis, elevated IL-6 serum levels were mainly related to the early fibrotic phase of the disease.21 Therefore, an involvement of inflammatory cytokines in the abnormal matrix process characteristic of PEX syndrome may be hypothesized.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the presence and expression of inflammatory cytokines in aqueous humor and ocular tissues of PEX eyes with special regard to different stages of the aberrant matrix process. Our findings revealed significantly elevated aqueous IL-6 and IL-8 levels, concomitant with an increased mRNA and protein expression of both cytokines in eyes with early stages of PEX syndrome. In contrast, late stages of PEX syndrome without and with glaucoma did not show any significant differences in aqueous levels or expression levels of IL-6 and IL-8 compared with controls. Further experiments were performed to assess the regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression and the effect of IL-6 and IL-8 on ECM expression by nonpigmented ciliary epithelial (NPE) cells in vitro. The findings suggest that an increased expression of IL-6 and IL-8, which may be induced by chronic stress conditions, such as oxidative stress14 and hypoxia,22 may act as a triggering factor for the abnormal PEX material production in the early stages of this fibrotic process.

Materials and Methods

Tissues and Samples

Aqueous humor (aspirated during cataract or filtration surgery) and serum samples were collected from patients with cataract (mean age, 75.1 ± 4.8 years; n = 26, 13 female, 13 male), a history of resolved (≥4 months) herpetic uveitis (mean age, 57.9 ± 14.4 years; n = 26, 10 female, 16 male), primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG; mean age, 69.5 ± 5.9 years; n = 26, 13 female, 13 male), PEX syndrome including early (mean age, 75.8 ± 8.1 years; n = 26, 15 female, 11 male) and late stages of the abnormal matrix process (mean age, 75.5 ± 7.8 years; n = 26, 13 female, 13 male), and PEX-associated open-angle glaucoma (mean age, 77.0 ± 7.3 years; n = 26, 13 female, 13 male) and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

All individuals underwent standardized ophthalmologic examination for signs of PEX syndrome in mydriasis and were classified as early- or late-stage PEX syndrome according to a semiquantitative grading score based on ocular structural changes associated with PEX, ie, PEX material deposits on anterior segment structures and various pigment-related signs (1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, marked; and 4, heavy manifestation).23 Early stages with mild disease (scores 1–2) were defined by diffuse precipitation of PEX material on the anterior lens capsule (pregranular stage or incomplete intermediate zone) or small flakes of PEX material on the pupillary margin, pigment liberation after pupillary dilation, mild pigment deposition on iris or lens, mild chamber angle deposition, beginning pupillary ruff atrophy, and slightly reduced mydriasis as compared with the contralateral eye. Late stages with severe disease (scores 3–4) were characterized by massive PEX material deposits on pupillary margin and/or lens revealing the classic pattern with a complete clear intermediate zone, heavy pigment deposition on anterior segment structures, extensive angle pigmentation and Sampaolesi line, extensive pupillary ruff atrophy, and highly restricted mydriasis. PEX glaucoma was defined, if elevated intraocular pressure (IOP > 20 mmHg), an open chamber angle, reproducible visual field defects in computed perimetry, and characteristic glaucomatous optic disk damage were found in the presence of manifest PEX material deposits. PEX patients with a history of previous trauma or intraocular surgery were excluded from the study.

Ocular tissues were obtained from six donor eyes with early PEX syndrome without glaucoma (mean age, 80.2 ± 5.9 years; four female, two male), six donor eyes with late PEX syndrome without glaucoma (mean age, 81.3 ± 5.3 years; two female, four male), and six normal appearing donor eyes (mean age, 77.3 ± 6.6 years; three female, three male) without any known ocular disease. Donors were classified as early or late stage PEX syndrome according to the amount of macroscopically visible PEX material deposits on ocular structures. Because PEX deposits can be detected earliest on zonular fibers,2 early stages were defined by a frosted appearance of the zonules, whereas late stages revealed prominent PEX material deposits on lens, iris, ciliary processes, and zonules. The presence of PEX material was confirmed by electron microscopic analysis of small tissue sectors, and the absence of glaucoma was confirmed by microscopic analysis of optic nerve cross-sections. These eyes were obtained at autopsy and were processed within 8 hours after death.

In addition, tissues of three eyes with PEX-associated open-angle glaucoma (mean age, 79.3 ± 1.7 years; two female, one male), three eyes with POAG (mean age, 76.7 ± 7.8 years; two female, one male), three eyes with PEX-associated angle closure glaucoma (mean age, 83.3 ± 3.1 years; two female, one male), and three eyes with angle closure glaucoma without evidence of PEX (mean age, 80.0 ± 3.3 years; two female, one male) were used. These eyes had to be surgically enucleated because of painful absolute glaucoma and were processed immediately after enucleation; their medical history has been documented previously.5

Informed consent to tissue donation was obtained from the patients or, in case of autopsy eyes, from their relatives, and the protocol of the study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for experiments involving human tissues and samples.

Multiplex Bead Immunoassay

Aqueous humor samples (50 μl, undiluted) were simultaneously analyzed for 20 different cytokines using the Beadlyte Human Multiplex Cytokine Detection kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Buckingham, U.K.) and the Luminex 100 flow cytometry system (Luminex, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sensitivity (picograms per milliliter) of the assay was as follows: IL-1α, 1.5; IL-1β, 0.6; IL-2, 1.0; IL-3, 4.0; IL-4, 0.7; IL-5, 0.2; IL-6, 0.3; IL-7, 3.9; IL-8, 0.5; IL-10, 0.3; IL-12, 1.5; IL-13, 1.5; IL-15, 0.5; TNF-α, 0.8; IFN-γ, 2.0; monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, 8.5; macrophage-inflammatory protein-1α, 22.5; regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, 3.0; Eotaxin, 9.0; and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, 1.0. Samples were run as single measurements, whereas standard curves of known concentrations of recombinant human cytokines (included in the kit) were run in duplicate. Aqueous protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

IL-6 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The concentrations of IL-6 were assessed in aqueous humor (50 μl, diluted 1/2) and serum (50 μl, undiluted) samples with a commercially available sandwich enzyme immunoassay kit (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All measurements were performed in duplicate. The sensitivity of the assay for IL-6 was 0.04 pg/ml. Aqueous protein concentrations were determined as described above.

Real-Time RT-PCR

Ocular tissues were prepared under a dissecting microscope and shock frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from ocular tissues and cultured cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), including an on-column DNase I digestion step. First-strand cDNA synthesis from 0.5 μg of total RNA and quantitative real-time PCR were performed using the MyIQ thermal cycler and software (Bio-Rad) as described previously.4 PCRs (25 μl) were run in duplicate and contained 2 μl of the 1/5 diluted first-strand cDNA, 0.4 μmol/L each of upstream- and downstream-primer, and IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Exon-spanning primers (MWG Biotech, Anzing, Germany), designed by means of Primer 3 software (http://fokker.wi.mit.edu/primer3/input.htm), and PCR conditions are summarized in Table 1. For quantification, serially diluted standard curves of plasmid-cloned cDNA were run in parallel, and amplification specificity was checked using melt curve and sequence analyses using the Prism 3100 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For normalization of gene expression levels, mRNA ratios relative to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were calculated.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Quantitative Real-Time PCR

| Gene | Accession no. | Product (bp) | Tan (°C) | MgCl2 (mmol/L) | Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | NM_000600 | 129 | 64 | 3.5 | 5′-CACACAGACAGCCACTCACCTC-3′ |

| 5′-GTGCCTCTTTGCTGCTTTCACAC-3′ | |||||

| IL-8 | NM_000584 | 110 | 62 | 3.0 | 5′-CCACCGGAAGGAACCATCTCAC-3′ |

| 5′-GGCAAAACTGCACCTTCACACAG-3′ | |||||

| Fibrillin-1 | NM_000138 | 184 | 64 | 3.5 | 5′-GAATGCAAGAACCTCATTGGCAC-3′ |

| 5′-TGGCGGTAAACCCATCATTACAC-3′ | |||||

| LTBP-1 | NM_000627 | 92 | 64 | 4.0 | 5′-AGGAGTTACAGGCTGAGGAATG-3′ |

| 5′-ACATCGACACAGGTCATCTTGG-3′ | |||||

| Fibulin-1 | NM_006487 | 231 | 62 | 3.5 | 5′-CTGCGAGTACAGCCTCATGG-3′ |

| 5′-AAGCAGGAGCAGACCACCTC-3′ | |||||

| Col-II-α1 | NM_001844 | 163 | 64 | 3.5 | 5′-GCAGGAATTCGGTGTGGACATAG-3′ |

| 5′-GGATGAATGGACATCAGGTCAGG-3′ | |||||

| TGF-β1 | NM_000660 | 75 | 64 | 4.0 | 5′-CGAGCCTGAGGCCGACTACTAC-3′ |

| 5′-CATAGATTTCGTTGTGGGTTTCC-3′ | |||||

| TGF-β2 | NM_003238 | 102 | 64 | 4.0 | 5′-CCTGCTGCACTTTTGTACCATC-3′ |

| 5′-TGGTATATGTGGAGGTGCCATC-3′ | |||||

| TGF-β3 | NM_003239 | 193 | 65 | 3.0 | 5′-TTGGAGGAGAACTGCTGTGTGC-3′ |

| 5′-AGGCAGATGCTTCAGGGTTCAG-3′ | |||||

| GAPDH | NM_002046 | 117 | 64 | 3.5 | 5′-AGCTCACTGGCATGGCCTTC-3′ |

| 5′-ACGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC-3′ |

Tan, annealing temperature; Col, collagen.

Immunohistochemistry

Indirect immunofluorescence labeling was performed on cryosections of ocular tissues as previously described24 using antibodies against IL-6 (clone B-E8; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.), IL-6 receptor (IL-6R, clone B-R6; Abcam), phospho-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) (pY705; Abcam), CD11b (clone ICRF44; Abcam), and CD68 (clone EBM11, DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Antibody binding was detected by Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and nuclear counterstaining was performed with propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany). In negative control experiments, the primary antibody was replaced by PBS or equimolar concentrations of an irrelevant primary antibody.

Western Blot Analysis

Ocular tissue specimens were homogenized in extraction buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, and 0.1% SDS) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Merck Biosciences, Nottingham, U.K.) using a rotor-stator homogenizer. Protein concentrations were determined by the Micro BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Bonn, Germany). Ten micrograms of total protein was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany) with a semidry blotting unit (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with Superblock (Thermo Scientific) for 1 hour and incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal antibodies against human p-STAT3 (clone 4; BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) or STAT3 (clone 84; BD Biosciences) diluted 1/500 or 1/2500 in Superblock, respectively. Equal loading was verified with mouse anti-human β-actin antibody (clone AC-15; Sigma-Aldrich) 1/5000 in Superblock. In negative control experiments, the primary antibody was replaced by PBS. Immunodetection was performed with an affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) diluted 1/10,000 in Superblock, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Signals were analyzed using the Chemi-Smart 5000 chemiluminescence detection system and software (Vilber Lourmat, Eberhardzell, Germany).

Cell Culture

To study the regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression, the immortalized human NPE cell line ODM-225 was used at passage 18. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal calf serum and 50 μg/ml gentamicin in a 95% air–5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. Cells were grown to subconfluence (90%), kept in serum-free medium for 24 hours, and then exposed to either hypoxia (2% oxygen), oxidative stress (50 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide, H2O2), 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (R&D Systems; Wiesbaden, Germany), 10 ng/ml IL-6 (PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany), or 10 ng/ml IL-8 (PeproTech) for up to 72 hours under serum-free conditions. Parallel cultures maintained under normoxic (21% oxygen) and serum-free conditions without addition of H2O2, TGF-β1, IL-6, or IL-8 served as controls.

Cell viability was assessed using a fluorescent kit (Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity kit; Molecular Probes) and a plate reader (Fluoroscan Ascent 2.4; Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, to count viable cells stained with calcein-AM and dead cells stained with ethidium homodimer-1 dye. The ratio of living to dead cells was calculated for the different treatment conditions and compared with parallel control cultures under serum-free and normoxic conditions without treatment.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical evaluation of differences between groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to assess the significance of correlations. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cytokine Profiles in Aqueous Humor

As a first step to explore the role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of PEX syndrome/glaucoma, we used a multiplex bead immunoassay to screen aqueous levels of 20 inflammatory cytokines in eyes with early and late stages of PEX syndrome and PEX glaucoma as well as in control eyes with cataract, POAG, or a history of resolved ocular inflammation (n = 14 for each group). Whereas IL-1α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-15, IFN-γ, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage-inflammatory protein-1α, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, eotaxin, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor could be detected in all sample groups, aqueous levels of IL-1β, IL-3, IL-5, and TNF-α were consistently below the sensitivity of the assay. Aqueous cytokine concentrations are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detection of Aqueous Humor Cytokines by Multiplex Bead Immunoassay

| Cataract

|

Inflammation

|

POAG

|

PEXS early

|

PEXS late

|

PEXG

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SD | Range Detectable | Mean SD | Range Detectable | Mean SD | Range Detectable | Mean SD | Range Detectable | Mean SD | Range Detectable | Mean SD | Range Detectable | |

| IL-1α | 13.3 | 1.9–52.2 | 28.6* | 5.0–106.2 | 13.7 | 2.9–68.6 | 13.2 | 4.1–55.8 | 10.1 | 1.7–40.7 | 10.2 | 2.5–47.4 |

| ±16.5 | (14/14) | ±32.4 | (14/14) | ±16.1 | (14/14) | ±12.6 | (14/14) | ±9.3 | (14/14) | ±10.6 | (14/14) | |

| IL-2 | 2.7 | <1.0–3.7 | 3.0 | <1.0–5.2 | 3.4 | <1.0–5.3 | 3.5 | <1.0–5.1 | 2.7 | <1.0–3.9 | 3.2 | <1.0–5.0 |

| ±0.7 | (8/14) | ±1.3 | (10/14) | ±2.1 | (8/14) | ±1.6 | (7/14) | ±0.7 | (8/14) | ±0.9 | (7/14) | |

| IL-4 | 3.7 | <1.0–7.4 | 3.8 | <1.0–4.7 | 4.3 | <1.0–6.6 | 4.1 | <1.0–6.4 | 3.4 | <1.0–4.3 | 4.1 | <1.0–5.3 |

| ±1.9 | (6/14) | ±0.6 | (8/14) | ±1.0 | (7/14) | ±1.1 | (8/14) | ±0.8 | (8/14) | ±0.9 | (6/14) | |

| IL-6 | 52.0 | 8.0–101.0 | 193.0*** | 72–683 | 59.0 | 16–127 | 186.0*** | 78–478 | 57.0 | 7–110 | 50.0 | 4–118 |

| ±34.0 | (14/14) | ±144.0 | (14/14) | ±39.0 | (14/14) | ±99.0 | (14/14) | ±32.0 | (14/14) | ±36.1 | (14/14) | |

| IL-7 | 9.9 | <3.9–40.0 | 11.4 | <3.9–40 | 8.3 | <3.9–22.8 | 12.1 | <3.9–22.7 | 7.4 | <3.9–15.2 | 10.7 | <3.9–24.7 |

| ±8.9 | (12/14) | ±10.1 | (14/14) | ±5.7 | (14/14) | ±6.2 | (12/14) | ±3.4 | (11/14) | ±5.8 | (13/14) | |

| IL-8 | 10.1 | 2.9–26.4 | 26.4* | 6.4–93.3 | 18.8 | 4.6–62.3 | 25.5** | 5.8–103.3 | 10.8 | 2.8–21.3 | 13.5 | 4.1–46.3 |

| ±6.6 | (14/14) | ±22.8 | (14/14) | ±14.8 | (14/14) | ±23.5 | (14/14) | ±5.3 | (14/14) | ±11.2 | (14/14) | |

| IL-10 | 2.3 | <1.0–4.4 | 5.3 | <1.0–27.3 | 2.4 | <1.0–3.7 | 2.3 | <1.0–3.5 | 1.9 | <1.0–2.8 | 2.1 | <1.0–3.4 |

| ±0.8 | (8/14) | ±6.5 | (13/14) | ±0.9 | (7/14) | ±0.8 | (8/14) | ±0.5 | (8/14) | ±0.6 | (6/14) | |

| IL-12 | 4.4 | <1.5–10.6 | 3.3 | <1.5–6.2 | 2.5 | <1.5–5.5 | 3.7 | <1.5–6.1 | 3.2 | <1.5–5.8 | 2.9 | <1.5–5.0 |

| ±2.8 | (13/14) | ±1.6 | (10/14) | ±1.5 | (9/14) | ±1.6 | (9/14) | ±1.7 | (7/14) | ±1.1 | (12/14) | |

| IL-13 | 6.0 | <1.5–8.0 | 5.9 | <1.5–7.3 | 6.9 | <1.5–8.5 | 7.2 | <1.5–8.2 | 6.7 | <1.5–7.5 | 6.4 | <1.5–7.5 |

| ±1.9 | (9/14) | ±0.9 | (8/14) | ±0.9 | (9/14) | ±1.1 | (8/14) | ±0.6 | (7/14) | ±0.6 | (6/14) | |

| IL-15 | 3.3 | <1.0–6.1 | 2.8 | <1.0–4.7 | 3.3 | <1.0–3.8 | 2.4 | <1.0–3.2 | 2.9 | <1.0–2.8 | 2.7 | <1.0–4.4 |

| ±1.4 | (7/14) | ±1.0 | (12/14) | ±0.6 | (8/14) | ±0.8 | (7/14) | ±0.3 | (5/14) | ±0.8 | (11/14) | |

| IFN-γ | 3.8 | <2.0–6.1 | 4.1 | <2.0–5.2 | 4.2 | <2.0–6.1 | 3.3 | <2.0–5.4 | 2.7 | <2.0–3.6 | 2.6 | <2.0–4.1 |

| ±1.5 | (8/14) | ±1.2 | (8/14) | ±1.7 | (7/14) | ±1.2 | (7/14) | ±0.6 | (6/14) | ±0.9 | (8/14) | |

| Eotaxin | 19.0 | 10.6–56.3 | 21.2 | 12.8–114.0 | 12.5 | <9.0–36.3 | 14.7 | <9.0–27.4 | 13.3 | <9.0–20.1 | 17.5 | 9.3–27.8 |

| ±10.7 | (14/14) | ±23.7 | (14/14) | ±8.0 | (12/14) | ±4.7 | (12/14) | ±4.2 | (13/14) | ±14.2 | (14/14) | |

| MCP-1 | 536.0 | 117.0–1173 | 586.0 | 176–1377 | 482.0 | 142–1217 | 583.0 | 225–1180 | 438.0 | 195–688 | 502.0 | 237–921 |

| ±268.0 | (14/14) | ±315.0 | (14/14) | ±293.0 | (14/14) | ±319.0 | (14/14) | ±139.0 | (14/14) | ±202.0 | (14/14) | |

| MIP-1α | 39.7 | <22.5–80.4 | 39.2 | <22.5–96.0 | 36.7 | <22.5–39.3 | 36.4 | <22.5–64.9 | 38.5 | <22.5–47.6 | 30.7 | <22.5–37.9 |

| ±25.0 | (7/14) | ±20.8 | (10/14) | ±2.8 | (4/14) | ±11.6 | (9/14) | ±11.9 | (5/14) | ±5.0 | (4/14) | |

| RANTES | 12.2 | <3.0–56.1 | 28.8** | 4.5–96.0 | 12.8 | <3.0–47.7 | 8.6 | <3.0–28.4 | 15.8 | <3.0–84.9 | 23.4 | <3.0–86.9 |

| ±12.3 | (13/14) | ±25.4 | (14/14) | ±24.2 | (10/14) | ±7.7 | (11/14) | ±21.3 | (12/14) | ±29.0 | (12/14) | |

| GM-CSF | 2.7 | <1.0–4.1 | 2.6 | <1.0–3.2 | 2.7 | <1.0–3.2 | 2.6 | <1.0–3.3 | 2.8 | <1.0–3.1 | 2.6 | <1.0–5.0 |

| ±0.6 | (12/14) | ±0.3 | (13/14) | ±0.4 | (10/14) | ±0.4 | (12/14) | ±0.4 | (12/14) | ±0.6 | (11/14) | |

Cytokine concentrations are given in picograms per milliliter as mean ± SD. The data include the range of values, and the number of samples in the detectable range. IL-1β, IL-3, IL-5, and TNF-α were consistently below the detection limit of the assay. POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; PEXS, PEX syndrome; early, initial stages of the PEX-process; late, late stages of the PEX-process; PEXG, PEX glaucoma; n = 14 for each group;

P < 0.01,

P < 0.005, and

P < 0.001. GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; MIP, macrophage-inflammatory protein; RANTES, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted.

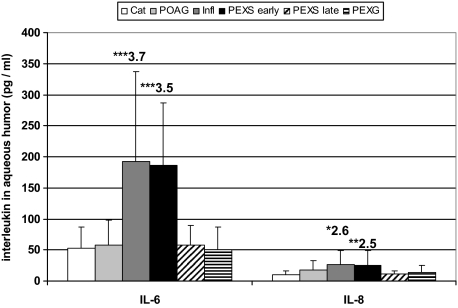

Whereas the majority of detectable cytokines displayed equal levels between the various groups of patients, significantly increased levels of IL-6 (3.5-fold; P < 0.001) and IL-8 (2.5-fold; P < 0.005) could be measured in aqueous samples of eyes with early stages of PEX syndrome (IL-6, 186 ± 99 pg/ml; IL-8, 25.5 ± 23.5 pg/ml) as compared with control eyes with cataract (IL-6, 52.0 ± 34.0 pg/ml; IL-8, 10.1 ± 6.6 pg/ml). In contrast, samples from eyes with late stages of PEX syndrome and PEX glaucoma did not display any significant differences as compared with controls. Patients with POAG displayed a tendency to increased IL-8 levels, which, however, did not reach statistical significance (1.8-fold; P < 0.065). Patients with a history of inflammatory ocular disease, serving as positive controls, displayed a significant increase of aqueous IL-1α (1.8-fold; P < 0.01), IL-6 (3.7-fold; P < 0.001), IL-8 (2.6-fold; P < 0.01), and regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (2.4-fold; P < 0.005) levels compared with cataract controls. Aqueous IL-6 and IL-8 levels in the different patient groups are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

IL-6 and IL-8 concentrations in human aqueous humor as measured by multiplex bead immunoassay. Aqueous IL-6 and IL-8 levels are increased in early stages of PEX syndrome, whereas late stages and PEX glaucoma display no significant differences as compared with cataract or POAG. Results are expressed as mean ± SD together with the relative fold change as compared with cataract (Cat, cataract; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; Infl, resolved ocular inflammation; PEXS, PEX syndrome; PEXG, PEX glaucoma; n = 14 for each patient group; *P < 0.01, **P < 0.005, and ***P < 0.001).

Aqueous levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were positively correlated in both patients with early stages of PEX syndrome (r = 0.937; P < 0.01) and in patients with previous ocular inflammation (r = 0.914; P < 0.01). The latter showed further positive correlations between IL-6 and IL-1α (r = 0.848; P < 0.01) as well as between IL-8 and IL-1α (r = 0.875; P < 0.01). However, no correlations between cytokine levels and aqueous protein levels could be established.

To validate and supplement the results obtained by multiplex analysis, concentrations of IL-6 were measured in aqueous humor and serum samples by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (n = 12 for each patient group). This approach confirmed a significant increase in IL-6 levels (2.4-fold; P < 0.001) in early stages of PEX syndrome (162.0 ± 90.1 pg/ml) as compared with cataract controls (68.8 ± 21.9 pg/ml) (Figure 2A). Again, late stages of PEX syndrome and PEX glaucoma did not differ significantly from the control group. Serum levels of IL-6 measured 3.1 ± 1.3 pg/ml in patients with cataract and were only elevated in patients with resolved ocular inflammation (6.5 ± 3.1 pg/ml; P < 0.0001) but not in patients with PEX syndrome/glaucoma or POAG (data not shown). Because of limited numbers of samples from patients with early stages of PEX syndrome, levels of IL-8 were not validated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Figure 2.

IL-6 and total protein concentrations in human aqueous humor as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Bradford assay, respectively. A: Aqueous IL-6 levels are increased in early stages of PEX syndrome and in samples with previous ocular inflammation (n = 12 for each patient group). B: Total aqueous protein levels indicating function of the blood-aqueous barrier are increased in late stages of PEX without and with glaucoma and in eyes with previous inflammation. Results are expressed as mean ± SD together with the relative fold change as compared with cataract (Cat, cataract; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; Infl, resolved ocular inflammation; PEXS, PEX syndrome; PEXG, PEX glaucoma; n = 26 for each group; *P < 0.005 and **P < 0.001).

Total aqueous protein levels were increased in patients with late stages of PEX syndrome and PEX glaucoma (up to 2.3-fold; P < 0.005) and in patients with previous ocular inflammation (3.9-fold; P < 0.005) as compared with cataract, confirming an impairment of blood-aqueous barrier function in these conditions (Figure 2B).26 In contrast, POAG samples and early stages of PEX syndrome displayed no significantly elevated protein levels. Aqueous IL-6 levels and protein levels were not correlated with each other confirming the multiplex data.

Expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in Ocular Tissues

To identify potential sources of aqueous IL-6 and IL-8, quantitative real-time PCR was performed on various ocular tissues from normal donor eyes (n = 4). These initial screening experiments showed a ubiquitous mRNA expression of both cytokines in all ocular tissues analyzed, ie, the cornea, trabecular meshwork, iris, lens, ciliary processes, choroid, and retina. A particularly pronounced expression, which was ∼100 times higher than that of all other tissues, could be detected within ciliary processes (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Quantitative determination of IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expression levels in human ocular tissues using real-time PCR technology. A: IL-6 and IL-8 expression in various ocular tissues of normal human donor eyes. The expression levels were normalized against GAPDH, and the results are expressed as molecules IL per molecules GAPDH. The values represent mean values ± SD of four separate experiments. B and C: IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expression in ciliary processes (B) and iris tissue (C) of PEX and control eyes; expression levels are increased in early stages of PEX syndrome. Data were normalized against GAPDH and are expressed as molecules interleukin per molecules GAPDH together with the relative fold change as compared with cataract. (PEXS, PEX syndrome; PEXG, PEX glaucoma; n = 6 for each patient group; *P < 0.001).

Next, ciliary process and iris cDNA were used to compare IL-6 and IL-8 expression in eyes with early and late stages of PEX syndrome and PEX glaucoma with that of normal and glaucomatous control eyes without PEX (n = 6 for each group). A significantly increased IL-6 mRNA expression was found in ciliary process (2.6-fold; P < 0.001) and iris tissue (1.7-fold; P < 0.005) of eyes with early PEX syndrome as compared with normal control eyes (Figure 3, B and C). In accordance, these early stages showed significantly increased mRNA expression levels of IL-8 in both ciliary processes (2.1-fold; P < 0.001) and iris (2.2-fold; P < 0.005). In contrast, posterior segment tissues, such as retina and choroid, did not show any differential expression between early PEX syndrome and control eyes (data not shown). Eyes with late PEX syndrome and PEX glaucoma did not display any significant differences as compared with controls. Consistent with aqueous cytokine levels, mRNA expression levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were correlated in early stages of PEX syndrome (r = 0.843; P < 0.01) indicating a concerted expression of both cytokines in this condition.

To assess the biological activity of IL-6, we performed Western blot analyses of STAT3 and p-STAT3 in protein extracts from iris and ciliary body tissue of eyes with early or late PEX syndrome and normal donors (n = 5 for each group). Binding of IL-6 to its receptor IL-6R (gp80) results in dimerization of the signal transducer gp130 and activation of the JAK/STAT pathway leading to the phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT3.27 Both STAT3 and p-STAT3 were detected in all samples with an apparent molecular mass of 92 kDa each (Figure 4, A and B). Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactive bands revealed that the ratio of p-STAT3 to STAT3 was selectively increased (approximately twofold; P < 0.005) in early stages of PEX syndrome as compared with controls and late stages of PEX syndrome (Figure 4C). Specific immunoreactivity was abolished, when PBS was used instead of the primary antibody (data not shown), and immunodetection of the housekeeping gene β-actin proved equal loading of the samples.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in protein extracts from iris and ciliary processes of PEX and control eyes. A and B: Representative Western blot with 10 μg of iridal and ciliary total protein from two normal donors (control) and two patients with early and late stages of PEX syndrome (PEXS), respectively. Equal loading of samples was verified by immunodetection of β-actin. C: Intensities of specific immunoreactive bands were quantified by computerized densitometry, and signal intensity of control samples was set to 100%. Results are expressed as the ratio of p-STAT3 to STAT3, together with the relative fold change in early PEXS as compared with control (n = 5; *P < 0.005).

The protein expression of IL-6, IL-6R, and p-STAT3 was also examined in cryosections of ocular tissues from eyes with early or late stages of PEX syndrome and normal control eyes (n = 6 for each group). In addition, antibodies against the leukocyte marker CD11b and the macrophage marker CD68 were used to assess the presence of inflammatory cells in ocular tissues. IL-6 could be immunolocalized to vascular endothelia of iridal blood vessels, to variable numbers of perivascular and stromal cells in iris and ciliary body stroma, to smooth muscle cells of the iris dilator and sphincter muscles, and to the nonpigmented layer of the ciliary epithelium, particularly in the area of ciliary processes. Staining intensities, particularly those of iris vessel walls and the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium, were considerably increased in eyes with early PEX syndrome as compared with late stages or normal control eyes (Figure 5). IL-6R, though only weakly expressed, showed a comparable distribution to that of IL-6 (data not shown). Staining for p-STAT3 showed positive immunoreactions in variable numbers of stromal and perivascular cells in iris and ciliary body and focally also in iridal vascular endothelial and ciliary epithelial cells. The number of stromal and perivascular cells positive for p-STAT3 was considerably increased in eyes with early stages of PEX syndrome as compared with late stages or normal control eyes (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence labeling of IL-6 in iris and ciliary process tissues of eyes with early and late stages of PEX syndrome (PEXS) and normal donor eyes (control). A, C, and E: Increased IL-6 immunopositivity (green fluorescence) is observed in blood vessel walls (arrows) and perivascular cells (arrowheads) of the iris stroma of an eye with early PEXS (age, 79 years) (C) as compared with late stage of PEXS without glaucoma (age, 81 years) (E) and normal control eye (age, 78 years) (A). B, D, and F: Increased IL-6 immunopositivity is observed in the nonpigmented epithelium (arrowheads) as well as in blood vessel walls (arrows) and stromal cells of ciliary processes of the same eyes with early PEXS (D) as compared with late stages of PEXS (F) and normal controls (B). (CE, ciliary epithelium; DM, dilator muscle; IPE, iris pigment epithelium; PEX, PEX material; ST, stroma; scale bar = 50 μm).

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence labeling of p-STAT3 in iris and ciliary process tissues of eyes with early and late stages of PEX syndrome (PEXS) and normal donor eyes (control). A, C, and E: Increased p-STAT3 immunopositivity (green fluorescence) is observed in stromal and perivascular cells (arrowheads) in the stroma and periphery of iris vessels (arrows) of an eye with early PEXS (age, 75 years) (C) as compared with late stage of PEXS without glaucoma (age, 78 years) (E) and normal control eye (age, 72 years) (A). B, D, and F: Increased p-STAT labeling is seen in stromal cells (arrowheads) of ciliary processes of the same eyes with early PEXS (D) as compared with late stages of PEXS (F) and normal controls (B). (AB, anterior iris border layer; CE, ciliary epithelium; PEX, PEX material; ST, stroma; scale bar = 50 μm).

Immunolocalization of CD11b and CD68 revealed the presence of inflammatory cells in the stroma of iris and ciliary body showing considerable interindividual variability, but no clear differences between the various PEX and control tissues (data not shown). Antibody binding was abolished when irrelevant antibodies or PBS were used instead of the primary antibodies (data not shown).

Regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 in Vitro

To identify potential pathogenetic factors that might be responsible for the up-regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression in the anterior segment of early stages of PEX syndrome, we studied the effect of hypoxia, oxidative stress, and TGF-β1 on the expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in vitro. Human NPE cells were exposed to sublethal levels of oxidative stress (50 μmol/L H2O2) or hypoxia (2% oxygen) or treated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for up to 72 hours under serum-free conditions. Parallel cultures maintained in serum-free medium and normoxic conditions without treatment served as controls. Viability assays conducted in parallel revealed ratios of living versus dead cells that were not significantly different from controls (data not shown).

Quantitative real-time PCR demonstrated that IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expression was rapidly up-regulated in a time-dependent manner as early as 6 hours (approximately twofold; P < 0.001) after exposure of NPE cells to hypoxia or oxidative stress (Figure 7). Maximum levels of up-regulation were reached after 48 and 72 hours, respectively (up to 5.4-fold; P < 0.0001). In contrast, TGF-β1 treatment had no significant effect on the basal expression of IL-6 or IL-8 in NPE cells (data not shown). To analyze whether TGF-β1 can modulate the stress-induced expression of cytokines, NPE cells were subjected to oxidative stress (50 μmol/L H2O2) either in the presence or absence of TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml). As illustrated in Figure 7B, TGF-β1 significantly attenuated the H2O2-induced up-regulation of both IL-6 and IL-8 after 24 hours (approximately twofold; P < 0.001). Maximum levels of suppression (up to 3.3-fold; P < 0.0001) were reached after 72 hours.

Figure 7.

Effect of hypoxia, oxidative stress, and TGF-β1 on the mRNA expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in cultured human NPE cells as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The expression levels were normalized against GAPDH, and the results are expressed as molecules IL per molecules GAPDH together with the maximum fold change of induction in hypoxia- or H2O2-treated cells as compared with untreated control cells and the maximum fold change of suppression (−) by TGF-β1 in cells treated with H2O2 in the presence of TGF-β1 as compared with H2O2-treated cells. A: Expression levels of IL-6 and IL-8 are significantly induced by hypoxia (2% O2) as compared with untreated control cells. B: Expression levels of IL-6 and IL-8 are significantly up-regulated by oxidative stress (50 μmol/L H2O2) as compared with untreated control cells. TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) significantly attenuated the H2O2-induced up-regulation of both IL-6 and IL-8 (ox. stress +TGF-β1) as compared with cells treated with H2O2 alone (ox. stress). The values represent mean values ± SD of three separate experiments; *P < 0.001 and **P < 0.0001.

To further investigate the potential role of increased IL-6 and IL-8 levels in early stages of PEX syndrome, we studied their effect on the expression of ECM components and TGF-β isoforms in vitro. Treatment of NPE cells with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) significantly induced the expression of fibrillin-1 and LTBP-1 (Figure 8A) reaching maximum levels of up-regulation at 24 hours (up to 3.3-fold; P < 0.0001). IL-6 had, however, no effect on the expression of fibulin-1 (Figure 8A) or collagen type II α 1 (data not shown). Moreover, IL-6 significantly induced the expression of TGF-β1 (3.1-fold; P < 0.0001) and to a lesser extent of TGF-β2 (1.6-fold; P < 0.001) with a maximum effect at 48 hours but did not influence expression of TGF-β3 (Figure 8B). In contrast, IL-8 treatment (10 ng/ml) had no significant effect on the expression of any of the ECM components or TGF-β isoforms (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Effect of IL-6 (10 ng/ml) on mRNA expression of ECM components and TGF-β isoforms in cultured human NPE cells as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The expression levels were normalized against GAPDH, and the results are expressed as molecules per molecules GAPDH together with the maximum fold change in treated cells as compared with untreated control cells. A: IL-6 significantly induced the expression of fibrillin-1 and LTBP-1 but not fibulin-1 (×104). B: IL-6 significantly induced the expression of TGF-β1 (×103) and TGF-β2 (×104) but not TGF-β3 (×103). The values represent mean values ± SD of three separate experiments; *P < 0.001 and **P < 0.0001.

Discussion

The group of inflammatory cytokines represents >50 signaling molecules including ILs, TNFs, IFNs, and chemokines. They are especially important for regulating inflammatory processes and consequently are often classified according to their proinflammatory (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) or anti-inflammatory (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13) activities. In addition to their role in inflammation and immune responses, these cytokines have also been implicated in the regulation of fundamental biological processes and in the pathophysiology of a huge array of diseases including fibrotic disorders, such as pulmonary fibrosis and systemic sclerosis.18,20,21 In fact, subtle chronic inflammatory processes, also termed “molecular inflammation,” have been suggested as major events underlying the causes of many age-related chronic degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disorders.16,28 According to this concept, one major factor in chronic tissue injury is considered to be oxidative stress, ie, the overproduction of reactive oxygen species. In aged individuals, oxidative stress combined with weakened cytoprotective strategies and stress-response mechanisms could lead to a persistent proinflammatory state by means of activation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as nuclear factor κB, causing the ongoing generation of proinflammatory molecules, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α. In contrast to acute inflammations, which are physiologically protective mechanisms designed to limit cellular injury, chronic inflammations eventually lead to loss of cellular homeostasis and pathophysiological reactions.

Inflammatory cytokines have been also shown to be widely expressed by various ocular cell types and to be present in aqueous and vitreous humor with increased levels in patients with uveitis and vitreoretinal disorders.29,30,31,32 Apart from their implication in inflammatory eye diseases, the chronic activation of proinflammatory mediators in the human trabecular meshwork and optic nerve has been suggested to contribute to the pathophysiology of glaucoma.11,12,13,33 Emerging evidence supports the concept of a chronically activated stress response in the trabecular meshwork characterized by the stress-induced up-regulation of proinflammatory mediators, such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, by trabecular cells.14,15,34 Whereas short-term activation of inflammatory mediators is believed to have cytoprotective effects and to modulate aqueous outflow resistance through induction of matrix metalloproteinases in the trabecular meshwork, a prolonged or chronic activation of inflammatory mediators may exert pathological tissue effects and contribute to glaucoma pathogenesis.

This study aimed to investigate the role of inflammatory cytokines in the pathobiology of PEX glaucoma and its underlying disorder, PEX syndrome, which has been characterized as a stress-induced fibrotic matrix process associated with the excessive production and accumulation of an abnormal elastotic material.1,2 Because proinflammatory mediators have been preferentially implicated in the initial phases of fibrotic disorders,18,21,35 patients and eyes examined were carefully classified as early or late stages of PEX syndrome according to semiquantitative grading scores described above. The findings revealed significantly increased aqueous levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in patients with early stages of PEX syndrome only, whereas patients with late stages of PEX syndrome/glaucoma did not differ significantly from the cataract control group. Increased aqueous levels of IL-6 and IL-8 did not correlate with aqueous total protein levels suggesting local production of these cytokines by anterior segment tissues instead of passive influx from the circulation. To identify their potential origin, we established a comprehensive expression profile of IL-6 and IL-8 in the adult human eye, demonstrating a nearly ubiquitous expression in ocular tissues. A particularly pronounced expression could be localized to the ciliary processes, with an expression level at least 100-fold higher than in other ocular tissues, suggesting the ciliary processes as the main secretory site for IL-6 and IL-8. Consistent with increased aqueous levels, eyes with early stages of PEX syndrome showed a significant up-regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression in ciliary process and iris tissues as compared with control eyes. This up-regulation was limited to anterior segment tissues of early PEX eyes. Again, patients with late stages of the disease did not display any significant differences in expression as compared with normal controls. Both aqueous and tissue levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were positively correlated with each other indicating a concerted action of both cytokines. Taken together, these findings point to a spatially and temporally restricted up-regulation of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 in anterior segment tissues during the initial phases of the fibrotic PEX process. Furthermore, they highlight the importance of an accurate phenotypic classification of different stages of disease manifestation to elucidate pathophysiological processes.

The major sources of IL-6 and IL-8 are cells of the immune system and vascular endothelial cells, but also other cell types such as smooth and striated muscle cells. Binding of secreted IL-6 to its specific receptor IL-6R is followed by the association with gp130, a common receptor component shared by several members of the IL-6 family of cytokines, thereby activating the intracellular tyrosine kinases of the Janus kinase family (JAKs). Activated JAKs then phosphorylate transcription factors of the STAT family, which then bind to specific IL-6-responsive elements, thereby regulating IL-6-specific genes.27 In ocular tissues of early PEX stages, IL-6 could be mainly localized to vascular endothelial and perivascular cells of iris vessels further to scattered cells in the iris and ciliary body stroma as well as to the nonpigmented epithelium of ciliary processes. This distribution pattern was largely paralleled by immunolocalization of IL-6R, suggesting autocrine or paracrine mechanisms of cytokine action. Moreover, increased phosphorylation of STAT3 in iris and ciliary body tissue as well as localization of p-STAT3 to iridal vessel walls and stromal cells is indicative of biological activity of IL-6. It is therefore suggested that increased aqueous cytokine levels result from increased secretion by the ciliary epithelium and iris vasculature and that iris vessels are one of the targets of cytokine action in eyes with early stages of PEX syndrome. IL-6 is known as an important mediator of increased vascular permeability and endothelial barrier dysfunction both in vitro and in vivo,36,37 and it is therefore tempting to speculate that IL-6 may be involved in iris vasculopathy and chronic breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier characteristic of all eyes with PEX syndrome/glaucoma.1,2,26 In fact, ultrastructural alterations of iris vessels have been shown to represent the earliest histological signs of PEX syndrome, which can be already detected in obviously unaffected contralateral eyes in cases with clinically unilateral disease.38

In acute ocular inflammation, proinflammatory cytokine levels are elevated by several orders of magnitude, decreasing to moderately elevated levels during remission.30,31 The significantly but only moderately increased levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in eyes with early stages of PEX appear, however, not to reflect any acute or resolved ocular inflammation, because PEX syndrome lacks any evidence of clinical and histological signs of acute inflammation. In confirmation, an increase in leukocyte/macrophage markers CD11b and CD68 was not associated with early PEX syndrome. Analogous to other age-related degenerative diseases, the present findings rather point to a subtle subclinical inflammation of anterior segment tissues as the result of a chronically activated stress response in early stages of PEX syndrome.16,28 Expression of proinflammatory cytokines is known to be responsive to a variety of stimuli, including inflammatory signals, cytokines, growth factors, and various stress conditions through many potential regulatory elements within their promoter regions.16 There is convincing evidence that cellular stress conditions, such as oxidative stress and ischemia/hypoxia, constitute major mechanisms involved in the pathobiology of PEX syndrome.1,9,10 In addition, TGF-β1 has been considered a key mediator of matrix formation in PEX eyes.8 Here we showed that IL-6 and IL-8 were rapidly up-regulated by ciliary epithelial cells in vitro in response to hypoxia or moderate levels of oxidative stress, as has been demonstrated for virtually all cell types with a basal expression of these cytokines.14,22 Therefore, these stress conditions, combined with severely impaired stress-response mechanisms,4,39 could well lead to a persistent proinflammatory state in the anterior segment of eyes with early PEX. In contrast, TGF-β1 had no effect on the basal expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in cultured ciliary epithelial cells, but markedly attenuated the stress-induced up-regulation of both IL-6 and IL-8 in vitro. It could be further speculated that TGF-β1 participates in the limitation of the proinflammatory state in later stages during the course of the disease. In general, the relationship between TGF-β1 and IL-6/8 expression has been reported to be rather cell type specific and complex involving a mutually effective stimulation that suggests the existence of an autocrine loop between TGF-β1 and IL-6 in trabecular meshwork cells.40

At the moment it is still unclear how IL-6 and IL-8 may participate in the molecular events underlying PEX syndrome. On the basis of their known activities, IL-6 and IL-8 may act by mechanisms such diverse as stimulation of ECM synthesis, induction of the fibrogenic growth factor TGF-β1, or enhancement of vascular permeability in the iris. Here we showed that IL-6, but not IL-8, induced the expression of both TGF-β1 and the elastic microfibrillar proteins fibrillin-1 and LTBP-1, which are main components of PEX material, by ciliary epithelial cells in vitro. Although IL-6 was also able to stimulate expression of TGF-β2, which is not specific for the PEX process, it failed to regulate fibulin-1, collagen type II α 1, and TGF-β3, thus arguing against a global up-regulation of elastic fiber and other ECM proteins and TGF-β isoforms. As TGF-β is a potent inducer of ECM, its up-regulation in NPE cells by IL-6 may in turn up-regulate the expression of fibrillin-1 and LTBP-1. Nevertheless, the rapid up-regulation of fibrillin-1 and LTBP-1, which precedes the up-regulation of TGF-β, suggests that IL-6 is able to exert a stimulating effect without the mediation of TGF-β. Proinflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6, have been previously demonstrated to display profibrotic characteristics in various fibrotic conditions41 and to induce the production of ECM components such as collagen, fibronectin, and glycosaminoglycans in human dermal fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and corneal keratocytes.42,43,44,45 Moreover, administration of IL-6 to fetal wounds resulted in scar formation.46 IL-6 also showed a significant induction of TGF-β1 mRNA and protein in the skin of IL-6 knockout mice47 and in cultured human trabecular meshwork cells.40 Collectively, these data suggest that the transient up-regulation of proinflammatory mediators may participate in the onset of fibrosis, possibly by activating TGF-β1 and ECM synthesis.

In conclusion, evidence provided in this study supports a role for a stress-induced, spatially, and temporally restricted subclinical inflammation in anterior segment tissues during the initial phases of the fibrotic PEX process. This chronically activated stress response in combination with impaired stress defense mechanisms and a specific genetic background may participate in the onset of fibrosis by up-regulating TGF-β1 and elastic matrix proteins and may exert pathological tissue effects such as chronic blood-aqueous barrier compromise. Further studies are required to elucidate the IL-6 signaling pathway and its role in the development of PEX syndrome, as they would identify potential pharmacological targets to interfere with this sight-threatening matrix process on an early stage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katrin Bitterer and Elke Meyer for excellent technical assistance and Miguel Coca-Prados for the supply of the human NPE cell line ODM-2.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Matthias Zenkel, Ph.D., Department of Ophthalmology, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Schwabachanlage 6, D-91054 Erlangen, Germany. E-mail: matthias.zenkel@uk-erlangen.de.

Supported by grant SFB-539 from the German Research Foundation.

References

- Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Naumann GOH. Ocular and systemic pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:921–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritch R, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. Exfoliation syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45:265–315. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovodenko B, Rostagno A, Neubert TA, Shetty V, Thomas S, Yang A, Liebmann J, Ghiso J, Ritch R. Proteomic analysis of exfoliation deposits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1447–1457. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenkel M, Kruse FE, Jünemann AG, Naumann GOH, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. Deficiency of the extracellular chaperone clusterin in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome may be implicated in the aggregation and deposition of pseudoexfoliative material. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1982–1990. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Pasutto F, Sommer P, Hornstra I, Kruse FE, Naumann GO, Reis A, Zenkel M. Genotype-correlated expression of lysyl oxidase-like 1 in ocular tissues of patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome/glaucoma and normal patients. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1724–1735. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorleifsson G, Magnusson KP, Sulem P, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Stefansson H, Jonsson T, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Stefansdottir G, Masson G, Hardarson GA, Petursson H, Arnarsson A, Motallebipour M, Wallerman O, Wadelius C, Gulcher JR, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Jonasson F, Stefansson K. Common sequence variants in the LOXL1 gene confer susceptibility to exfoliation glaucoma. Science. 2007;317:1397–1400. doi: 10.1126/science.1146554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumbiegel M, Pasutto F, Mardin CY, Weisschuh N, Paoli D, Gramer E, Zenkel M, Weber BH, Kruse FE, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Reis A. Exploring functional candidate genes for genetic association in German patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2796–2801. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, Küchle M, Sakai LY, Naumann GOH. Role of transforming growth factor-β and its latent form binding protein in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:765–780. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliakos GG, Konstas AGP, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Hollo G, Katsimbris IE, Georgiadis N, Ritch R. 8-Isoprostaglandin F2A and ascorbic acid concentration in the aqueous humour of patients with exfoliation syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:353–356. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig H, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Noske W, Kellner U, Foerster MH, Naumann GOH. Anterior-chamber hypoxia and iris vasculopathy in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. German J Ophthalmol. 1994;3:148–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P, Epstein DL, Borras T. Genes upregulated in the human trabecular meshwork in response to elevated intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:352–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KH, Wu CC, Roy S, Lee SM, Liu JH. Increased interleukin-6 in aqueous humor of neovascular glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2627–2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Chintala SK, Fini ME, Schuman JS. Activation of a tissue-specific stress response in the aqueous outflow pathway of the eye defines the glaucoma disease phenotype. Nat Med. 2001;7:304–309. doi: 10.1038/85446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Luna C, Liton PB, Navarro I, Epstein DL, Gonzalez P. Sustained stress response after oxidative stress in trabecular meshwork cells. Mol Vis. 2007;13:2282–2288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liton PB, Gonzalez P. Stress response of the trabecular meshwork. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:378–385. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815f52a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Longo DL, Ferrucci L. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: a magnificent pathway. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61A:575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Herruzo JA, de la Torre P, Diaz-Sanjuan T. IL-6 and extracellular matrix remodeling. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:575–595. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082005000800006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauldie J, Kolb M, Sime PJ. A new direction in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2002;3:1–3. doi: 10.1186/rr158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto N. Oxidative stress and IL-6 mediate the fibrogenic effects of rodent Kupffer cells on stellate cells. Hepatology. 2006;44:1487–1501. doi: 10.1002/hep.21427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor TV, Friberg D, Medsger TA, Jr, Buckingham RB, Whiteside TL. Cytokine production and serum levels in systemic sclerosis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;65:278–285. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90158-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Sato S, Fujimoto M, Ihn H, Kikuchi K, Takehara K. Serum levels of IL-6, oncostatin M, soluble IL-6 receptor, and soluble gp130 in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:308–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm M, Bihl M, Eickelberg O, Stulz P, Perruchoud AP, Roth M. Hypoxia-induced interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 production is mediated by platelet-activating factor and platelet-derived growth factor in primary human lung cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:653–661. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.4.3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince AM, Streeten BW, Ritch R. Preclinical diagnosis of pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1076–1082. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060080078032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, Nüsing RM. Expression and localization of FP and EP prostanoid receptor subtypes in human ocular tissues. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1475–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Vasallo P, Ghosh S, Coca-Prados M. Expression of Na, K-ATPase α subunit isoforms in the human ciliary body and cultured ciliary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1989;141:243–252. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041410203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küchle M, Nguyen N, Hannappel E. The blood-aqueous barrier in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Ophthalmic Res. 1995;27(Suppl 1):136–142. doi: 10.1159/000267859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Matsuda T, Nakajima K. Signal transduction through gp130 that is shared among the receptors for the interleukin 6 related cytokine subfamily. Stem Cells. 1994;12:262–277. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HY, Sung B, Jung KJ, Zou Y, Yu BP. The molecular inflammatory process in aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:572–581. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Savant V, Scott RA, Curnow SJ, Wallace GR, Murray PI. Multiplex bead analysis of vitreous humor of patients with vitreoretinal disorders. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2203–2207. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnow SJ, Falciani F, Durrani OM, Cheung CM, Ross EJ, Wloka K, Rauz S, Wallace GR, Salmon M, Murray PI. Multiplex bead immunoassay analysis of aqueous humor reveals distinct cytokine profiles in uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4251–4259. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooij B, Rothova A, Rijkers GT, Groot-Mijnes JDF. Distinct cytokine and chemokine profiles in the aqueous of patients with uveitis and cystoid macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:192–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace GR, Curnow SJ, Wloka K, Salmon M, Murray PI. The role of chemokines and their receptors in ocular disease. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2004;23:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Zhang SS, Zhang C. The two sides of cytokine signaling and glaucomatous optic neuropathy. J Ocul Biol Dis Inform. 2009;2:78–83. doi: 10.1007/s12177-009-9026-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liton PB, Luna C, Bodman M, Hong A, Epstein DL, Gonzalez P. Induction of IL-6 by mechanical stress in the trabecular meshwork. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D. Pulmonary fibrosis: a cellular overreaction or a failure of communication? J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1501–1502. doi: 10.1172/JCI13318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo N, Morita I, Shirao M, Murota S. IL-6 increases endothelial permeability in vitro. Endocrinology. 1992;131:710–714. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1639018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Abraham CR, Masliah E, Kemper P, Inglis JD, Oldstone MB, Mucke L. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10061–10065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer T, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Naumann GOH. Unilateral or asymmetric pseudoexfoliation syndrome? An ultrastructural study Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1023–1031. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenkel M, Kruse FE, Naumann GOH, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. Impaired cytoprotective mechanisms in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome/glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5558–5566. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liton PB, Li G, Luna C, Gonzalez P, Epstein DL. Cross-talk between TGF-β1 and IL-6 in human trabecular meshwork cells. Mol Vis. 2009;15:326–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Anthony DC, Pitossi F, Gauldie Transient expression of IL-1β induces acute lung injury and chronic repair leading to pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1529–1536. doi: 10.1172/JCI12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MR, Berman B. Stimulation of collagen and glycosaminoglycan production in cultured human adult dermal fibroblasts by recombinant human interleukin 6. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:686–692. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12483971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhr KB, Tsuboi R, Seo EY, Piao YJ, Lee JH, Park JK, Ogawa H. Sphingosylphosphorylcholine stimulates cellular fibronectin expression through upregulation of IL-6 in cultured human dermal fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;294:433–437. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba A, Aida Y, Suzuki N, Watanabe Y, Kawato T, Motohashi M, Maeno M, Matsumura H, Matsumoto M. Effects of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor on the expression of cartilage matrix proteins in human chondrocytes. Connect Tissue Res. 2007;48:263–270. doi: 10.1080/03008200701587513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecaze F, Simorre V, Chollet P, Tack JL, Muraine M, Le Guellec D, Vita N, Arne JL, Darbon JM. Interleukin-6 in tear fluid after photorefractive keratectomy and its effects on keratocytes in culture. Cornea. 1997;16:580–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechty KW, Adzick NS, Crombleholme TM. Diminished interleukin 6 (IL-6) production during scarless human fetal wound repair. Cytokine. 2000;12:671–676. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett-Chastain LR, Gallucci RM. Interleukin (IL)-6 modulates transforming growth factor-β expression in skin and dermal fibroblasts from IL-6-deficient mice. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:237–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]