Abstract

Five fungal genomes from the Ascomycota (sac fungi) were found to contain a gene with sequence similarity to a recently discovered small group of bacterial prenyltransferases that catalyze the C-prenylation of aromatic substrates in secondary metabolism. The genes from Aspergillus terreus NIH2624, Botryotinia fuckeliana B05.10 and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum 1980 were expressed in Escherichia coli, and the resulting His8-tagged proteins were purified and investigated biochemically. Their substrate specificity was found to be different from that of any other prenyltransferase investigated previously. Using 2,7-dihydroxynaphthalene (2,7-DHN) and dimethylallyl diphosphate as substrates, they catalyzed a regiospecific Friedel-Crafts alkylation of 2,7-DHN at position 3. Using the enzyme of A. terreus, the Km values for 2,7-DHN and dimethylallyl diphosphate were determined as 324 ± 25 μm and 325 ± 35 μm, respectively, and kcat as 0.026 ± 0.001 s−1. A significantly lower level of prenylation activity was found using dihydrophenazine-1-carboxylic acid as aromatic substrate, and only traces of products were detected with aspulvinone E, flaviolin, or 4-hydroxybenzoic acid. No product was formed with l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, or 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate. The genes for these fungal prenyltransferases are not located within recognizable secondary metabolic gene clusters. Their physiological function is yet unknown.

Keywords: Aspergillus, Enzyme Catalysis, Fungi, Isoprenoid, Metabolism, Botryotinia, Dimethylallyltransferase, PT Fold, Prenyltransferase, Sclerotinia

Introduction

Recently, a new family of prenyltransferases has been discovered in bacteria of the genus Streptomyces (1–4). They are involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, e.g. antibiotics. The members of this family are characterized by a new protein fold, termed PT barrel (1). The PT barrel consists of five repetitive ααββ elements, with the β strands forming a central barrel. In contrast to the TIM barrel, the PT barrel consists of 10 antiparallel β strands and contains the active site of the enzyme in its spacious lumen. The members of this enzyme family catalyze Friedel-Crafts alkylations of aromatic substrates, i.e. the formation of carbon-carbon-bonds between C-1 or C-3 of the isoprenoid substrate and an aromatic carbon of the acceptor substrate. In contrast to the membrane-bound aromatic prenyltransferases of ubiquinone, menaquinone, and plastoquinone biosynthesis (5), the enzymes containing the PT barrel are soluble proteins and do not contain (N/D)DxxD motifs for binding of the isoprenoid substrate.

In fungi, the prenylation of aromatic substrates leads to a large and important class of secondary metabolites, the prenylated indole alkaloids (6). Also, the fungal indole prenyltransferases are soluble enzymes without (N/D)DxxD motifs (7). Very recently, we solved the first structure of a fungal indole prenyltransferase, i.e. of the dimethylallyltryptophan synthase. This enzyme also showed the PT barrel structure (8). For prenyltransferases characterized by the PT barrel fold, the name ABBA prenyltransferases has been suggested (3). From the currently available data, the ABBA prenyltransferases can be divided into two groups. In the dimethylallyltryptophan synthase/LtxC group, PSI-BLAST searches reveal more than a hundred entries in the database with sequence similarity to dimethylallyltryptophan synthase, mostly in fungal genomes but also some bacterial enzymes, e.g. LtxC (9) and CymD (10). Typically, the members of this group catalyze the prenylation of indole moieties (7). In the CloQ/NphB group, PSI-BLAST searches reveal 12 entries within the bacterial genus Streptomyces (and five fungal genes discussed below) that show sequence similarity to CloQ of clorobiocin biosynthesis (2) and to NphB of naphterpin biosynthesis (1) (see Fig. 1). The currently known members of this group catalyze the prenylation of phenols and phenazine derivatives (4). Sequence similarity between these two groups cannot be detected with PSI-BLAST searches but can be detected with more powerful bioinformatic techniques like HHpred (11), indicating a distant evolutionary relationship. Structure predictions (12, 13) suggest that all members of the two groups exhibit the PT barrel fold.

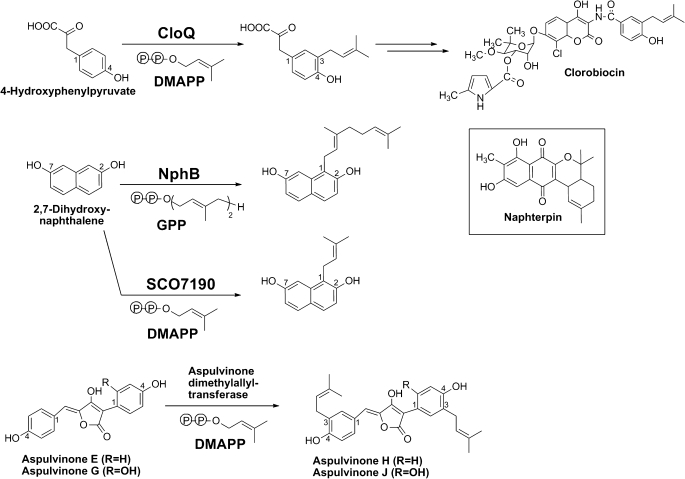

FIGURE 1.

Reactions catalyzed by the bacterial enzymes CloQ, NphB, and SCO7190 and by the fungal aspulvinone dimethylallyltransferase. The genuine aromatic substrate of NphB in the biosynthesis of naphterpin is unknown; 2,7-dihydroxynaphthalene is one of the artificial substrates accepted in vitro. GPP, geranyl diphosphate.

In the last years, genome-sequencing projects of fungi of the subphylum Pezizomycotina (the largest group of the phylum Ascomycota, i.e. sac fungi) revealed in five different species, including A. terreus, a gene with no sequence similarity to any other fungal gene but with obvious similarity to the bacterial ABBA prenyltransferases of the CloQ/NphB group (3). No data have been published on their possible function. However, 30 years ago, a soluble aromatic prenyltransferase was identified in A. terreus and purified to apparent homogeneity (14, 15). It was functionally identified as aspulvinone dimethylallyltransferase, catalyzing a reaction similar to that of the bacterial ABBA prenyltransferase CloQ (Fig. 1). Yet, the gene coding for aspulvinone dimethylallyltransferase has not been identified. In the present study, we expressed the A. terreus gene with sequence similarity to CloQ as well as two orthologs from other fungal species, purified the resulting proteins, and investigated them biochemically to determine whether they indeed are aromatic prenyltransferases and whether they may represent the aspulvinone dimethylallyltransferase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

DMAPP2 and geranyl diphosphate were synthesized according to Woodside et al. (16). Flaviolin was prepared as described by Gross et al. (17). Dihydrophenazine-1-carboxylic acid was generated as described by Saleh et al. (18). Aspulvinone E was synthesized according to Bernier and Brückner (19). IPTG, Tris, NaCl, glycerol, dithiothreitol, MgCl2, formic acid, sodium dodecyl sulfate, polyacrylamide, and EDTA were bought at Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany. 1,6-Dihydroxynaphthalene, 4-hydroxyphenyl-pyruvate, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, TAPS, methanol, Tween 20, and imidazole were bought at Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany. 2,7-Dihydroxynaphthalene and 1,3-dihydroxynaphthalene were bought at Acros Organics. Merck delivered dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, β-mercaptoethanol, sodium ascorbate, methanol D4, l-tryptophan, and l-tyrosine. Lysozyme was bought at Boehringer Ingelheim, Heidelberg, Germany.

Protein Expression and Purification

The nucleotide sequences of ptfSs, ptfBf, and the truncated ptfPm-S (lacking the coding sequence for the first 57 amino acids of XP_002143864) were optimized for expression in Escherichia coli with the Gene Designer Tool and synthesized commercially by DNA2.0 (Basel, Switzerland). All three genes were excised from vector pJ201 (DNA2.0) with NcoI and EcoRI and ligated into vector pHis8 (20) using the same restriction sites.

Likewise, the sequence of ptfAt was optimized with the Gene Designer Tool and was synthesized including the His8 tag and the linker region as found in pHis8 (20). It was delivered in the expression vector pJExpress411 (DNA2.0) and used without further cloning. The His8 tag and linker region were thereby identical in all four constructs.

35 ml of an overnight culture in Luria-Bertani medium (50 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 25 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol) of E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) pLysS cells harboring one of the plasmids were used to inoculate 1 liter of terrific broth (21) (50 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 25 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol). The cultures were grown at 37 °C and 250 rpm to an A600 of 0.6. Temperature was lowered to 20 °C, and IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mm. Synthesis of recombinant protein was allowed to proceed for 6 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 20 min at 2700 × g at 4 °C, and the pellet was stored at −20 °C. Cells were thawed and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mm imidazol, 1% Tween 20, 0.5 mg ml−1 lysozyme, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) using a ratio of 25 ml lysis buffer for 10 g of pellet. After stirring for 30 min at 4 °C, cells were ruptured with a Branson sonifier. Debris and membranes were removed by centrifugation at 38,720 × g for 45 min. The supernatant was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose resin column (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions, using a linear gradient of 0–60% 250 mm imidazole (in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol) in 60 min for elution. The eluate was passed over PD-10 columns (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) and equilibrated and eluted with 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 15% glycerol, 2 mm dithiothreitol. The proteins were stored in this buffer at −80 °C.

For further purification, PtfAt was loaded on an anion exchange column (Resource Q, 30 × 6.4 mm, 15 μm; GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions and eluted with a linear gradient of 0–50% 1 m NaCl in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The eluate was again passed over PD-10 columns as described above.

Assay for Prenyltransferase Activity

The reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 100 mm sodium-TAPS pH 8.7, 2 mm aromatic substrate, 2 mm isoprenoid substrate, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm sodium ascorbate, and either 7.2 μg PtfAt or 15 μg PtfSs, or 50 μg PtfBf. After incubation for 10 min at 30 °C, the reaction was stopped with 100 μl of ethyl acetate/formic acid (40:1). After vortexing and centrifugation, 75 μl of the organic layer was transferred to an Eppendorf tube. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue was dissolved in 50 μl methanol and analyzed by HPLC, using an Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B) each containing 1% (v/v) formic acid were used as eluents. A linear gradient was ran from 20–100% solvent B in 30 min. Products were detected with a photo diode array detector. Assays containing amino acids as aromatic substrates were stopped after incubation with 10 μl formic acid. The protein was removed by centrifugation at 21,460 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was directly analyzed by HPLC as described above.

1H NMR Data of the Enzymatic Product 3-Dimethylallyl-2,7-dihydroxynaphthalene

The NMR spectrum was recorded at 250 MHz in a Bruker AC-250 spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany), with CD3OD as solvent. δ values are given in ppm. The solvent signal (3.3 ppm) was used as reference: δ, 1.73 (br s, 3H, H-4′), 1.76 (br s, 3H, H-5′), 3.37 (d, J = 7.32 Hz, 2H, H-1′), 5.39 (m, 1H, H-2′), 6.78 (dd, J = 8.67 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H, H-6), 6.84 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 6.86 (s, 1H, H-1), 7.34 (s, 1H, H-4), and 7.48 (d, J = 8.85 Hz, 1H, H-5).

Sequence Analysis

Database searches were performed with BLASTP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Secondary structure predictions were performed with GenTHREADER (12, 13), and sequences were aligned with ClustalW2 (22) and visualized with ESPript (23).

Calculation of Kinetic Constants

Km and kcat were calculated using GraphPad Prism software, version 5.01 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA.

RESULTS

Sequence Analysis

A gene with sequence similarity to the CloQ/NphB group of ABBA prenyltransferases is found in the genomes of only five fungal species in the database: A. terreus NIH2624, Botryotinia fuckeliana B05.10, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum 1980, Penicillium marneffei ATCC18224, and Microsporum canis CBS113480. In this study, these genes will be designated as ptfAt, ptfBf, ptfSs, ptfPm, and ptfMc, respectively. In the genome sequences of the respective organisms, they have been designated as ATEG_00821, BC1G_01295, SS1G_09465, PMAA_022320, and MCYG_05060, respectively. An alignment of the amino acid sequence of their predicted gene products with the sequences of the bacterial enzymes CloQ (2), NovQ (24), and NphB (1) is shown in Fig. 2. This reveals obvious similarities between the sequences as well as conservation of several of the amino acids found to interact with the pyrophosphate moiety of the isoprenoid substrate in the x-ray structure of NphB (1).

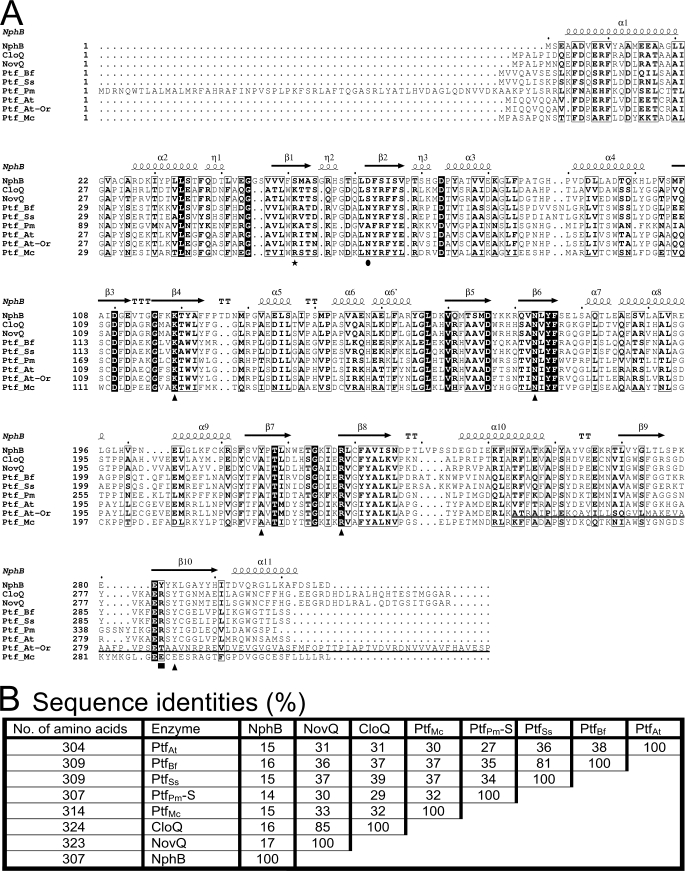

FIGURE 2.

A, sequence comparison of the bacterial prenyltransferases NphB, CloQ, and NovQ with the fungal proteins PtfAt, PtfBf, PtfSs, PtfPm, and PtfMc. For PtfAt, both the current sequence in the database (PtfAt-Or) and the corrected sequence (PtfAt) are displayed. The amino acids of NphB involved in the binding of the pyrophosphate moiety (▴, Lys119, Asn173, Tyr216, Arg228, and Lys284; over H2O ■, Tyr282) and in the coordination of the Mg2+ ion (●, Asp62) are marked. Likewise, the position of the lysine residue of CloQ and NovQ, suggested to functionally replace the positive charge of the Mg2+ ion, is marked (★). The sequence was created with Clustal W2 (22) and visualized by ESPript 2.2 (23). The sequence shows the secondary structure elements of NphB: α, α helices; η, 310 helices; β, β strands; TT, strict β turns. Strict sequence identity is shown by a black box with a white character, and similarity is shown by bold characters in a black frame. B, sequence identities (%) of the predicted gene products of the fungal genes ptfAt, ptfBf, ptfSs, ptfPm-S, and ptfMc with the bacterial ABBA prenyltransferases NphB, CloQ, and NovQ. For ptfPm, an N-terminally truncated version (ptfPm-S) was used for this calculation (see text).

However, in the case of the A. terreus protein (GenBankTM accession number XP_001210907, PtfAt-Or in Fig. 2), similarity to the other enzymes stops abruptly downstream of the amino acid corresponding to position 253 in NphB (Fig. 2). Closer inspection of the nucleotide sequence showed that this position marks the beginning of the first of two predicted introns in the current annotation of the gene ptfAt (ATEG_00821). As the bioinformatics prediction of introns is prone to errors, we generated a translation of the genomic sequence without introns (sequence PtfAt in Fig. 2), and this showed close similarity to the other fungal and bacterial enzymes. We therefore suggest that the gene ptfAt does not contain introns, just like ptfBf, ptfSs, and ptfPm. This suggestion was later on supported by the demonstration of enzymatic activity of the protein generated from the genomic sequence of ptfAt in E. coli (see below). The gene ptfMc is annotated to contain a small intron near its 3′ end; bioinformatic analysis does not allow to decide whether this annotation is correct.

The N terminus of the predicted gene product of ptfPm was >50 amino acids longer than that of the four other fungal proteins. For the current study, we generated a truncated version of this gene (termed ptfPm-S), lacking the coding sequence for the first 57 amino acids and thereby having a similar size as the other proteins in this study. The active site of the protein, located inside the β barrel, should not be affected by this truncation.

The sequence identity in between the five predicted fungal proteins ranges from 27 to 81% (Fig. 2B). As noted previously (3), they are closely related to the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate-3-dimethylallyltransferases CloQ and NovQ (2, 24), but only distantly to NphB (1) and the other nine bacterial ABBA prenyltransferases of the CloQ/NphB group in the database.

NphB is magnesium-dependent in its catalytic activity, but CloQ and NovQ are not. Correspondingly, the aspartate residue required for the coordination of Mg2+ in NphB (Asp62, Fig. 2) is not conserved in CloQ and NovQ, and neither is this residue conserved in the five predicted fungal proteins. Kuzuyama et al. (1) suggested that the positive charge of Mg2+ in NphB is functionally replaced by a positively charged lysine residue in CloQ and NovQ and by an arginine residue in the related prenyltransferase SCO7190. As shown in Fig. 2, the five fungal proteins also contain arginine or lysine residues in this position, predicting that they may represent Mg2+-independent prenyltransferases. This was later confirmed by biochemical investigations (see below). Structure prediction using GenTHREADER (12, 13) showed that all five fungal enzymes are likely to have the PT barrel fold.

Protein Expression and Purification

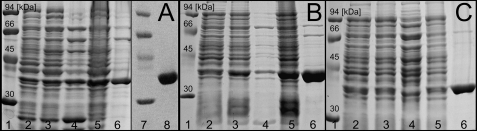

The nucleotide sequences of ptfAt, ptfBf, and ptfSs as well as of the truncated ptfPm-S were optimized for expression in E. coli and synthesized commercially (see “Experimental Procedures”). The expression plasmids were introduced into E. coli. After induction with IPTG, the cells were harvested, and the His8-tagged proteins were purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (Fig. 3A–C). PtfAt was further purified by ion exchange chromatography to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 3A). Although a part of the proteins remained insoluble, PtfAt, PtfBf, and PtfSs could be obtained in yields of 21, 11, and 25 mg per liter culture, respectively. In contrast, PtfPm-S was completely insoluble and could not be purified. The sequence of ptfMc has only been deposited in the database when the current study was already in progress. Biochemical investigations were therefore carried out initially with PtfAt and later on also with PtfBf and PtfSs.

FIGURE 3.

Purification of the fungal prenyltransferases PtfAt (A), PtfBf (B), and PtfSs (C) after expression in the form of His8-tagged fusion proteins. Lane 1, molecular mass standards; lane 2, total protein before IPTG induction; lane 3, total protein after IPTG induction; lane 4, soluble protein after IPTG induction; lane 5, insoluble protein after IPTG induction; lane 6, protein after Ni2+ affinity chromatography; lane 7, molecular mass standards; lane 8, protein after ion exchange chromatography. The calculated masses are 36.6 kDa for PtfAt, 36.7 kDa for PtfSs, and 36.5 kDa for PtfBf. The 12% polyacrylamide gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250.

Demonstration of C-prenyltransferase Activity of PtfAt

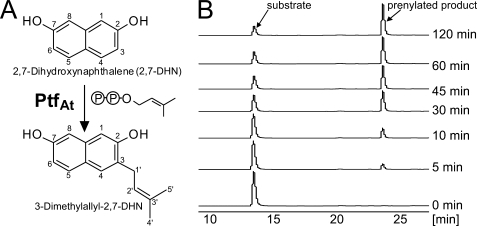

2,7-Dihydroxynaphthalene (2,7-DHN) is one of the aromatic substrates accepted by the bacterial ABBA prenyltransferases NphB and SCO7190 (Fig. 1) (25). When purified PtfAt was incubated with DMAPP and 2,7-DHN, the enzyme- and time-dependent formation of a prenylated product was readily observed in HPLC-UV (Fig. 4B). HPLC-MS analysis in the positive mode showed the molecular ion of the product at m/z = 229 [M+H]+, corresponding to a monoprenylated derivative of 2,7-DHN. Subsequently, the assay was repeated on a large scale, and the product was isolated by preparative HPLC and investigated by 1H NMR and 13C NMR (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). In the 1H NMR spectrum of the substrate 2,7-DHN, the signals of the aromatic protons can be detected at 6.91 ppm (H-1), 6.83 ppm (H-3), and 7.54 ppm (H-4). The signals of the protons at position 3 and 4 show coupling with 8.82 Hz, while the more distant protons at position 1 and 3 couple with 2.37 Hz. This results in a double doublet signal for H-3. In the symmetrical 2,7-DHN molecule, the signals of H-5, H-6, and H-8 are identical to those of H-4, H-3, and H-1, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

A, the aromatic prenylation reaction catalyzed by PtfAt. B, HPLC analysis of prenyltransferase assays with PtfAt. Detection: UV, 285 nm.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the enzymatic product clearly showed the signals of a dimethylallyl moiety (see supplemental Fig. S1). The chemical shift of the signal of H-1′ of the dimethylallyl moiety (3.37 ppm) showed that it is attached to an aromatic carbon, not to an oxygen atom. The NMR signals of the aromatic protons H-5, H-6, and H-8 were essentially unchanged in comparison with the substrate. However, the signal of H-3 had disappeared, and correspondingly, the signals of H-1 and H-4 now appeared as singlets rather than doublets. This proved that substitution had occurred at C-3 of the aromatic nucleus (Fig. 4A). Therefore, PtfAt catalyzes a C-prenylation of the aromatic substrate, i.e. a Friedel-Crafts alkylation, similar as reported for other ABBA prenyltransferases (3, 4). The regiospecificity of the prenylation by PtfAt (Fig. 4A) is in contrast to the prenylation of 2,7-DHN by the bacterial prenyltransferases NphB and SCO7190 (Fig. 1), both of which lead to substitution at C-1 of 2,7-DHN (25).

Testing of Aspulvinone E as Substrate of PtfAt

Previous biochemical investigations of aspulvinone dimethylallyltransferase from A. terreus showed that aspulvinone E (Fig. 1) is readily accepted as substrate of this enzyme, leading predominantly to a diprenylated product (14, 15). For the present study, aspulvinone E was synthesized according to a published procedure (19), and the identity of the compound was confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR. When aspulvinone E was incubated with PtfAt and DMAPP, no product formation could be observed in HPLC-UV analysis. The more sensitive HPLC-MS analysis, however, showed a low formation of a monoprenylated product (data not shown). The reaction velocity of the prenylation of aspulvinone E by PtfAt was at least 60 times lower than the prenylation of 2,7-DHN, and much lower than described previously for the aspulvinone dimethylallyltransferase purified from cell-free extracts of A. terreus (14, 15). Therefore, aspulvinone E is not the preferred substrate of PtfAt.

Biochemical Properties of PtfAt

The biochemical properties of the enzyme were investigated using 2,7-DHN and DMAPP as substrates. In the assay described in the “Experimental Procedures,” the formation of the prenylated product showed linear dependence on the amount of PtfAt (up to 10 μg) and on reaction time (up to 30 min). During prolonged incubation, a precipitation of protein was sometimes observed. Inclusion of NaCl into the incubation mixture was not useful to resolve this problem because it reduced the reaction velocity of the prenylation (50% reduction by 500 mm NaCl). Therefore, NaCl was not included into the assays, but incubation time was reduced to 10 min. In sharp contrast to the bacterial ABBA prenyltransferase NphB (1), to the membrane-bound aromatic prenyltransferase UbiA (26), and to the transprenyltransferases such as FPP synthase (27), PtfAt showed catalytic activity in the complete absence of Mg2+ or any other divalent cation. Addition of 10 mm EDTA did not influence the reaction velocity. Therefore, binding of the isoprenoid substrate does not occur in form of a magnesium complex, as shown for FPP synthase (27). Nevertheless, addition of MgCl2 to the incubation mixture increased the reaction velocity. The optimal concentration of MgCl2 was found to be 10 mm, leading to a 2.4-fold increase of product formation. Similar observations have been reported both for fungal and for bacterial aromatic prenyltransferases of the ABBA family, e.g. for dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (28) and for CloQ (2). The pH optimum of PtfAt was determined as 8.7, with half-maximal reaction velocities at pH 8.1 and 9.4. The enzyme could be stored at −80 °C, with <5% loss of activity within two months.

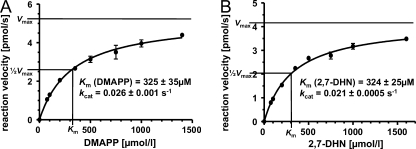

Using a constant concentration of 2,7-DHN (2 mm) and varying concentrations of DMAPP, a typical hyperbolic curve of product formation over substrate concentration was obtained, indicating that the reaction followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 5A). Nonlinear regression analysis resulted in a Km value for DMAPP of 325 ± 35 μm and a kcat of 0.026 ± 0.001 s−1. Using different concentrations of 2,7-DHN (up to 1.6 mm) in the presence of 2 mm DMAPP, likewise a hyperbolic curve was observed, resulting in a Km value for 2,7-DHN of 324 ± 25 μm (Fig. 5B). Using these values the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of the conversion of the non-genuine substrate 2,7-DHN by PtfAt was calculated as 80 m−1 s−1. This is >50 times higher than the value of 1.4 m−1 s−1 reported for the conversion of 2,7-DHN by NphB (25) but significantly lower than the values of 5280, 12400 or 46250 m−1 s−1 calculated for the prenylation of the genuine substrates of the ABBA prenyltransferases CloQ (2), PpzP (18), or dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (8). When 2,7-DHN was used in concentrations higher than 2 mm, substrate inhibition was observed. 20 mm 2,7-DHN inhibited product formation almost completely. It was not possible to calculate a Ki value, as no typical substrate inhibition curve was obtained. This may indicate multiple interactions of the phenolic substrate 2,7-DHN with the protein at high concentrations.

FIGURE 5.

Determination of Km values of PtfAt for DMAPP and 2,7-dihydroxynaphthalene. In A, 2,7-diydroxynaphthalene was kept constant at 2 mm. In B, DMAPP was kept constant at 2 mm. Km and kcat values were determined by nonlinear regression, using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Substrate Specificity of PtfAt

A range of aromatic compounds, previously found to be accepted by various bacterial or fungal ABBA prenyltransferases, were tested as substrates of PtfAt, each in a concentration of 2 mm. Of these, only 5,10-dihydrophenazine 1-carboxylic acid yielded a product formation that was detectable by HPLC-UV analysis. HPLC-MS analysis showed that it was a monoprenylated product with the same properties as the product formed by PpzP (18) in a positive control assay. Yet, reaction velocity with this substrate was nearly 50 times lower than with 2,7-DHN (Table 1). Incubation of PtfAt with flaviolin (2,5,7-trihydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone) yielded a very low enzymatic formation of a monoprenylated product, detectable only in HPLC-MS. For other aromatic substances, including l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 1,3-dihydroxynaphthalene, and 1,6-dihydroxy-naphthalene, neither HPLC-UV nor HPLC-MS analysis showed any enzymatic product formation, whereas positive control assays with dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (28), CloQ (2), Fnq26 (29), and NphB (1) readily showed the formation of prenylated products from these aromatic substrates. This proves that the specificity of PtfAt for its aromatic substrate is different from that of any other prenyltransferase investigated so far.

TABLE 1.

Formation of prenylated products by the fungal prenyltransferases PtfAt, PtfSs, and PtfBf from different aromatic substrates and DMAPP. n.d., no product detectable in HPLC-UV and HPLC-MS analysis. See text for further explanations.

| Aromatic substrate | PtfAt |

PtfSs |

PtfBf |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol product × s−1 × mg protein−1 | % | pmol product × s−1 × mg protein−1 | % | pmol product × s−1 × mg protein−1 | % | |

| 2,7-Dihydroxy-naphthalene | 570 | 100 | 280 | 100 | 76 | 100 |

| 5,10-Dihydro-phenazine-1-carboxylic acid | 12 | 2.1 | 7.5 | 2.7 | 7.7 | 10.1 |

| Flaviolin | <10 | <1.7 | <5 | <1.8 | <1.5 | <2 |

| Aspulvinon E | <10 | <1.7 | <5 | <1.8 | n.d. | n.d. |

| p-Hydroxy-benzoic acid | n.d. | n.d. | <9 | <3.2 | 11 | 14.5 |

PtfAt was found to be specific for DMAPP. When DMAPP was replaced by geranyl diphosphate, no formation of a prenylated product from 2,7-DHN was observed. As expected, also isopentenyl diphosphate gave no product formation.

Biochemical Investigation of PtfSs and PtfBf

The enzymes from S. sclerotiorum and B. fuckeliana, PtfSs and PtfBf, showed very similar biochemical properties as PtfAt from A. terreus. Upon incubation with 2,7-DHN and DMAPP, both enzymes gave a single product that was identical to that formed by PtfAt in HPLC and mass spectrometry. Both enzymes were active in the absence of Mg2+, but addition of 10 mm MgCl2 increased reaction velocity by a factor of 2.6 for PtfSs and 2.2 for PtfBf.

The Km values for 2,7-DHN were determined as 590 ± 136 μm for PtfSs and 996 ± 177 μm for PtfBf. For DMAPP, the respective values were 1232 ± 75 μm and 1010 ± 125 μm. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for the prenylation of 2,7-DHN resulted as 22 and 5 m−1 s−1, still higher than the value of 1.4 m−1 s−1 reported for the prenylation of 2,7-DHN by NphB (25) but somewhat lower than the value observed of PtfAt.

Like PtfAt, the enzymes from S. sclerotiorum and B. fuckeliana were specific for DMAPP and did not accept geranyl diphosphate or isopentenyl diphosphate. Also their specificity for aromatic substrates resembled that of PtfAt (Table 1); other than 2,7-DHN, only 5,10-dihydrophenazine-1-carboxylic acid gave an enzymatic product formation that was detectable in HPLC-UV analysis. With flaviolin, product formation was detectable only in HPLC-MS. Product formation with aspulvinone E could be detected in HPLC-MS for PtfSs but remained below detection limit for PtfBf. In all cases, the prenylation products formed by PtfSs and PtfBf were identical to those formed by PtfAt in their chromatographic and mass spectrometric properties.

In contrast to PtfAt, both PtfSs and PtfBf gave a monoprenylated product with 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, but due to the low amount of product, its structure could not be solved. Just as for PtfAt, no product formation was observed when PtfSs or PtfBf were incubated with l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate, 1,3-dihydroxynaphthalene, or 1,6-dihydroxy-naphthalene as aromatic substrates. Therefore, the properties of PtfSs and PtfBf are similar to those of PtfAt but at variance to those reported for any other previously investigated prenyltransferase.

DISCUSSION

The present study proves that the ptf genes of A. terreus, S. sclerotiorum, and B. fuckeliana code for functional prenyltransferases that attach isoprenoid moieties to carbon atoms of aromatic substrates in an enzyme-catalyzed Friedel-Crafts reaction. Their substrate specificity is clearly different from that of any other known prenyltransferase. In the prenylation of the artificial substrate 2,7-DHN they show a different regiospecificity than the previously examined bacterial enzymes NphB and SCO7190 (1, 25). Therefore, these fungal enzymes represent an interesting addition to the presently available aromatic prenyltransferases, which can be used for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of bioactive molecules (25, 30–32).

The amino acid sequences of PtfAt, PtfSs, and PtfBf, as well as those of the gene products of ptfPm and ptfMc, are closely related to the bacterial enzymes NovQ and CloQ, which catalyze the 3-prenylation of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate in the biosynthesis of clorobiocin and novobiocin (2, 24, 33). The protein encoded by ptfMc has therefore been annotated as “NovQ” (GenBankTM accession number EEQ32241). However, in clear contrast to NovQ and CloQ, none of the three fungal proteins investigated in this study accepted 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate as substrate.

The physiological function of these enzymes in the respective fungal organism remains unknown. Our study disproves the hypothesis that they may be responsible for the prenylation reaction in the biosynthesis of aspulvinone H and J (Fig. 1) (14, 15). An inspection of the genes located in the vicinity of the ptf genes in the genomes of the fungi A. terreus, B. fuckeliana, S. sclerotiorum, P. marneffei, and M. canis gives no indication of a secondary metabolic gene cluster to which the ptf genes may belong (see supplemental Tables S1–S5). This fact, i.e. that the ptf genes are not part of a recognizable secondary metabolic gene cluster, is at variance with the previously investigated fungal genes for indole prenyltransferases of the dimethylallyltryptophan synthase/LtxC group (7), but reminiscent of the bacterial genes SCO7190 and SCO7467 in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), the best examined bacterium of the genus Streptomyces (34). The predicted gene products of both genes show obvious similarity to aromatic prenyltransferases with a PT barrel fold, and the enzymatic activity of the protein encoded by SCO7190 has already been demonstrated in vitro (1, 25). Yet, a physiological function is not known for either of these two bacterial genes, and no primary or secondary metabolite resulting from an aromatic prenylation reaction possibly catalyzed by the enzymes encoded by these genes has been identified in S. coelicolor. Therefore, the present study clearly proved that PtfAt, PtfSs, and PtfBf exhibit a specific, new prenyltransferase activity, but it remains unknown whether these enzymes have a physiological function in their respective fungal organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Saleh, B. Boll, K. Seeger, U. Metzger, P. Zeyhle, and I. Unsöld for help in the bioinformatic data analysis, generation of expression plasmids, and synthesis of substrates. We are grateful to A. Kulik (Faculty of Biology, Tübingen University) for HPLC-MS analysis and to H. Bisswanger (Interfacultary Institute of Biochemistry, Tübingen University) for help in data analysis of the enzyme kinetics. We also thank J.P. Noel, Salk Institute, San Diego, CA, for kindly providing plasmid pHis8.

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S5 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- DMAPP

- dimethylallyl diphosphate

- IPTG

- isopropyl thiogalactoside

- 2,7-DHN

- 2,7-dihydroxynaphthalene

- TAPS

- 3-{[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]amino}-1-propanesulfonic acid

- HPLC-MS

- high pressure liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- PSI-BLAST

- position specific iterative basis local alignment search tool.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuzuyama T., Noel J. P., Richard S. B. (2005) Nature 435, 983–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pojer F., Wemakor E., Kammerer B., Chen H., Walsh C. T., Li S. M., Heide L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2316–2321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tello M., Kuzuyama T., Heide L., Noel J. P., Richard S. B. (2008) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 1459–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saleh O., Haagen Y., Seeger K., Heide L. (2009) Phytochemistry 70, 1728–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heide L. (2009) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13, 171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams R. M., Stocking E. M., Sanz-Cervera J. F. (2000) Top. Curr. Chem. 209, 97–173 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffan N., Grundmann A., Yin W. B., Kremer A., Li S. M. (2009) Curr. Med. Chem. 16, 218–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzger U., Schall C., Zocher G., Unsöld I., Stec E., Li S. M., Heide L., Stehle T. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14309–14314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards D. J., Gerwick W. H. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11432–11433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz A. W., Lewis C. A., Luzung M. R., Baran P. S., Moore B. S. (2010) J. Nat. Prod. 73, 373–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Söding J., Biegert A., Lupas A. N. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W244–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuffin L. J., Jones D. T. (2003) Bioinformatics 19, 874–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones D. T. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 287, 797–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi I., Ojima N., Ogura K., Seto S. (1978) Biochemistry 17, 2696–2702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sagami I., Ojima N., Ogura K., Seto S. (1985) Methods Enzymol. 110, 320–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodside A. B., Huang Z., Poulter C. D. (1988) Organic Syntheses 66, 211–215 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross F., Luniak N., Perlova O., Gaitatzis N., Jenke-Kodama H., Gerth K., Gottschalk D., Dittmann E., Müller R. (2006) Arch. Microbiol. 185, 28–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleh O., Gust B., Boll B., Fiedler H. P., Heide L. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14439–14447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernier D., Brückner R. (2007) Synthesis 15, 2249–2272 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jez J. M., Ferrer J. L., Bowman M. E., Dixon R. A., Noel J. P. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 890–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D. I., Métoz F. (1999) Bioinformatics 15, 305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozaki T., Mishima S., Nishiyama M., Kuzuyama T. (2009) J. Antibiot. 62, 385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumano T., Richard S. B., Noel J. P., Nishiyama M., Kuzuyama T. (2008) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 8117–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melzer M., Heide L. (1994) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1212, 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poulter C. D. (2006) Phytochem. Rev. 5, 17–26 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unsöld I. A., Li S. M. (2005) Microbiology 151, 1499–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haagen Y., Unsöld I., Westrich L., Gust B., Richard S. B., Noel J. P., Heide L. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 2889–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botta B., Delle, Monache G., Menendez P., Boffi A. (2005) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 606–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koehl P. (2005) Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 71–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macone A., Lendaro E., Comandini A., Rovardi I., Matarese R. M., Carraturo A., Bonamore A. (2009) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 6003–6007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steffensky M., Li S. M., Vogler B., Heide L. (1998) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 161, 69–74 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentley S. D., Chater K. F., Cerdeño-Tárraga A. M., Challis G. L., Thomson N. R., James K. D., Harris D. E., Quail M. A., Kieser H., Harper D., Bateman A., Brown S., Chandra G., Chen C. W., Collins M., Cronin A., Fraser A., Goble A., Hidalgo J., Hornsby T., Howarth S., Huang C. H., Kieser T., Larke L., Murphy L., Oliver K., O'Neil S., Rabbinowitsch E., Rajandream M. A., Rutherford K., Rutter S., Seeger K., Saunders D., Sharp S., Squares R., Squares S., Taylor K., Warren T., Wietzorrek A., Woodward J., Barrell B. G., Parkhill J., Hopwood D. A. (2002) Nature 417, 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.