Abstract

Background

The hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) is a primary immunodeficiency characterized by infections of the lung and skin, elevated serum IgE, and involvement of the soft and tissues. Recently, HIES has been associated with heterozygous dominant-negative mutations in STAT3 and severe reductions of Th17 cells.

Objective

To determine whether there is a correlation between the genotype and phenotype of HIES patients and to establish diagnostic criteria to distinguish between STAT3 mutated and STAT3 wild-type patients.

Methods

We collected clinical data, determined Th17 cell numbers, and sequenced STAT3 100 patients with a strong clinical suspicion of HIES and serum IgE >1000 IU/mL. explored diagnostic criteria by using a machine-learning approach to identify which features best predict a STAT3 mutation.

Results

In 64 patients we identified 31 different STAT3 mutations, 18 of which are novel. These included mutations at splice sites and outside the previously implicated DNA-binding and SH2 domains. A combination of five clinical features predicted STAT3 mutations with 85% accuracy. Th17 cells were profoundly reduced in patients harboring STAT3 mutations, while 10 out of 13 patients without mutations had low (<1%) Th17 cells but were distinct markedly reduced IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells.

Conclusions

We propose the following diagnostic guidelines for STAT3-deficient HIES: Possible: IgE >1000 IU/mL plus a weighted score of clinical features >30 based on recurrent pneumonia, newborn rash, pathologic bone fractures, characteristic face, and high palate. Probable: Above plus lack of Th17 cells or a family history for definitive HIES. Definitive: Above plus a dominant-negative heterozygous mutation in STAT3.

Keywords: Hyper-IgE Syndrome, HIES, Job syndrome, Th17 cells, STAT3-mutations, diagnostic guidelines

INTRODUCTION

The hyper IgE syndrome (HIES) is a multisystem disorder characterized by eczema, skin abscesses, recurrent staphylococcal infections of the skin and lungs, pneumatocele formation, candidiasis, eosinophilia, and elevated serum levels of IgE. Non-immunologic features of HIES include characteristic facial appearance, scoliosis, retained primary teeth, joint hyperextensibility, bone fractures following minimal trauma, and craniosynostosis.1–3 In 1999, the NIH clinical HIES scoring system based on 19 clinical and laboratory findings was introduced.4 A point scale was developed: more specific and objective findings were assigned more points. Scores of at least 40 points suggested HIES, while a score of below 20 made the diagnosis unlikely. For intermediate values, no firm conclusion could be reached.

In 2007, mutations in the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) were shown to be a cause of HIES.5,6 STAT3 plays a key role in the signal transduction of a broad range of cytokines.7,8 After cytokine binding and JAK (Janus kinase) activation, STAT3 is phosphorylated, dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it controls transcription of its target genes.9 STAT3 is crucial for the IL-6-mediated regulation of Th17 cells that are significant producers of IL-17, a proinflammatory cytokine involved in the host defense of S. aureus and Candida.10–12

There are seven publications on STAT3 mutations reporting on 155 patients with HIES. In 141 of these patients, heterozygous mutations in STAT3 were identified.5,6,13–17 Therefore, we addressed the question: how common is a diagnosis of HIES without a STAT3 mutation? We also asked: do some features of the HIES phenotype make it more likely that an HIES patient has a STAT3 mutation and can any feature(s) of the HIES phenotype predict the location of mutations within STAT3; i.e., is there any phenotype-genotype correlation?

As STAT3 has 24 exons and three splice variants, predicting which patients are likely to have a STAT3 mutation could save sequencing resources.

In a multi-center cohort of 100 patients with suspected HIES, we evaluated 17 of the clinical and laboratory features used in the original scoring method,4 the recently reported laboratory feature of a very low Th17 CD4+ T cell count, and the genetic diagnosis to develop a new scoring system aimed to discern those HIES patients with STAT3 mutations from those without mutation.14–16

Based on our analysis of 100 unrelated patients, evaluated world-wide, we propose guidelines for a clinical assessment prior to a confirmation of the suspected diagnosis by laboratory and molecular analysis.

METHODS

Patients and controls

Over the last eight years, we have collected a cohort of 228 patients with the suspected diagnosis of HIES in a world-wide collaboration; 55 of these patients have been published elsewhere.6,13,17,18 Of the remaining patients, 100 unrelated patients fulfilled inclusion criteria for this study: signed consent form, complete NIH scoring sheet, a strong clinical suspicion of HIES according to the referring immunologist, an IgE >1000 IU/mL, and an available sample of genomic DNA (gDNA) or RNA. To promote uniformity of documentation across the 33 different participating centers, a scoring sheet listing the original NIH clinical symptoms was used.4

Of the 100 patients with the clinical suspicion of HIES, 61 were male and 39 female; the age of the patients at the time of clinical evaluation ranged between 1 and 58 years. Seventy-two patients came from Europe, 20 from the Middle East, seven from South America, and one from North America.

Eighty patients had HIES scores ≥40 suggesting that these patients probably had HIES, whereas 20 patients had scores below 40, suggesting a diagnostic uncertainty or a variant of HIES.19 Only two of these patients (UPN133 and 134) have been described in published STAT3 mutation reports.17 Detailed information on patients, including clinical scores and detected STAT3 mutations, are summarized in Table E1 and in reference 20.

We applied the diagnostic guidelines, developed using the clinical scores of the cohort of 100 patients to a replication set of 50 unrelated patients all scored by a consistent team of clinicians at the NIH. Of these 50, 33 had a mutation in STAT3 and 17 did not; the 33 patients with a STAT3 mutation were from a previously published cohort.6 In addition 28 patients with severe atopic dermatitis and an IgE level >1000IU/ml were scored.

Control DNA was isolated from 100 healthy Caucasians according to approved protocols. STAT3 was sequenced in all controls to verify that the sequence changes seen in patients were not frequent polymorphisms. In addition, twelve controls were studied for their lymphocyte phenotype. All patients and controls or their parental or legal guardians provided written consent for the conducted studies, following local ethics committee requirements.

PCR and Sequencing

Genomic DNA and RNA of controls and patients was isolated from either whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed using Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen).

Coding genomic sequences and cDNA of STAT3 were amplified and purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Primer sequences are available upon request. Purified PCR products were sequenced with the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator cycle ready reaction kit V3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the PCR primers as sequencing primers. The sequencing was performed on a 3130xl Applied Biosystems Genetic Analyzer, and the data were analyzed with DNA Sequencing Analysis software, version 5.2 (Applied Biosystems) and Sequencher™ version 4.8 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, USA).

Cell culture and TNF-α ELISA

Monocyte-derived macrophages were generated as previously described,21 kept in Opti-Mem I serum free medium (Invitrogen, UK), and differentiated by using 50 ng/mL M-CSF (Peprotech, UK). After five days of culture, the monocytes/macrophages were pre-incubated with 25 ng/mL IL-10 (R&D) for one hour and then stimulated overnight with 50 ng/mL E.coli LPS (Sigma). TNF-α release was measured by ELISA (PeproTech) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Lymphocyte stimulation and Flow Cytometry

Blood was collected from 30 patients and 12 healthy donors. PBMCs were isolated using LymphoprepTM (Axis-Shield) and viably frozen. Freshly thawed cells resuspended at a concentration of 106/mL in RPMI (Lonza), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco), were exposed to Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma) 1µg/mL and Brefeldin A (Sigma) 2.5µg/mL 16 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cells were then surface-stained for CD4 (PerCP) and CD45RO (PE-Cy7), followed by an intracellular staining for IL-17 (Alexa Fluor® 647) and IFN-γ (FITC). Intracellular staining was performed by using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD Biosciences). All antibodies were from BD Biosciences, except for IL-17 which was from eBioscience. Data were acquired on an LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed with Prism 5.01 software (Prism); P-values are two-sided.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate statistical analyses were done using GNU R.22 For tests where we had a prior hypothesis (e.g., higher clinical score is associated with a STAT3 mutation), P-values were one-sided; otherwise P-values were two-sided. A Bonferroni correction was applied to each series of univariate tests.

The 100 patients in the cohort form our data set for univariate analysis and our training set for the machine learning methods described below. The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of STAT3-deficient HIES was the discovery of a heterozygous mutation (most mutations proven to be dominant negative) in STAT3 using the DNA sequencing techniques described above. Table I shows the prevalence of each feature in our HIES cohort. Based on preliminary experiments, we found that support vector machines (SVMs) are an effective way to classify this data set. To compare feature sets,23 we took the scores for 17 of the 19 features4 and calculated the leave-one-out accuracy for SVMs generated from each subset of size at most two and no more than seven. Because there are 41,208 such subsets, we used the software package OOQP (http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~swright/ooqp/),24 which contains specialized code to generate linear SVMs. We used a pre-release version of OOQP (available from E.M.G.) that provides leave-one-out estimation and that has been optimized for speed.

Table I.

Number and percentage of patients positive for the 17 evaluated features. Features were considered as present if more than one point of the NIH score4 was achieved. The five cardinal clinical features (recurrent pneumonia, newborn rash, pathologic bone fractures, characteristic face and cathedral palate) are shaded.

| all HIES | HIES STAT3 wt | HIES STAT3 mutated |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||||

| Recurrent pneumonia | 85/100 | 85 | 24/36 | 66.7 | 61/64 | 95.3 |

| Eczema | 90/100 | 90 | 32/36 | 88.9 | 58/64 | 90.6 |

| Recurrent skin abscesses | 86/100 | 86 | 28/36 | 77.8 | 58/64 | 90.6 |

| Characteristic face | 82/99 | 82.8 | 24/35 | 68.6 | 58/64 | 90.6 |

| Failure to shed deciduous teeth | 60/86 | 68.9 | 16/31 | 51.6 | 44/55 | 80.0 |

| Lung cyst formation | 61/97 | 62.9 | 14/34 | 41.2 | 47/63 | 74.6 |

| Eosinophilia | 68/94 | 72.3 | 27/36 | 75.0 | 41/58 | 70.7 |

| Newborn rash | 52/86 | 60.5 | 15/29 | 51.7 | 37/57 | 64.9 |

| Other unusual infections | 47/94 | 50 | 13/34 | 38.2 | 34/60 | 56.7 |

| Increased inter-alar distance | 37/83 | 44.6 | 10/31 | 32.3 | 27/52 | 51.9 |

| Cathedral palate | 41/84 | 48.8 | 12/31 | 38.7 | 29/53 | 54.7 |

| Hyperextensibility | 37/87 | 42.5 | 8/32 | 25.0 | 29/55 | 52.7 |

| Pathologic bone fractures | 32/94 | 34.0 | 5/35 | 14.3 | 27/59 | 45.8 |

| Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections | 41/92 | 44.6 | 14/33 | 42.4 | 27/59 | 45.8 |

| Candidiasis | 37/91 | 40.6 | 12/33 | 36.4 | 25/58 | 43.1 |

| Scoliosis | 20/83 | 24.1 | 7/33 | 21.2 | 13/50 | 26.0 |

| Midline anomaly | 12/86 | 14.0 | 5/34 | 14.7 | 7/52 | 13.5 |

We chose as candidate feature sets those 344 sets for which OOQP reported leave-one-out accuracy of better than 80%. Leave-one-out testing was performed with OOQP and SVMlight (http://svmlight.joachims.org/),25 as described in the Online Repository. For several feature sets, a classifier was trained using SVMlight on the scores from our cohort of 100 patients and then applied to predict whether each of the patients in the replication set has a STAT3 mutation.

RESULTS

STAT3 mutations

Of the 100 unrelated patients with suspected HIES, 64 carried heterozygous mutations within STAT3. Thirty-six patients did not show any mutation in the coding regions of STAT3 or their flanking intronic sequences. Overall, we found 31 distinct mutations: 46 patients carried previously described mutations,5,6,13–17 and 18 patients harbored distinct, novel mutations. Of these 18 mutations, eight affected the DNA-binding domain, five the SH2 domain, four the transactivation domain and one the coiled-coil domain (see Table II).

Table II.

Among the 100 patients studied, 64 patients had 31 distinct mutations. Thirteen of these mutations were reported previously.5,6, 13–17 The other 18 distinct mutations, which are shaded in this table, have not been previously reported. The cDNA sequence positions reported are from isoform NM_139276.2. The amino acid positions from the isoform NP_644805.1.

| Number of patients |

Protein domain | Site of mutation |

DNA sequence change | Predicted amino acid change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coiled-coil | Exon 3 | c.172C>T | H58Y |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 10 | c.982_990dupTGCATGCCC | C328_P330dup |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 10 | c.1025G>A | G342D |

| 2 | DNA-Binding | Intron 11 | c.1110−2A>G | D371_G380del |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Intron 11 | c.1110−1G>T | D371_G380del |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Intron 12 | c.1139+1G>T | D371_G380del |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Intron 12 | c.1139+2insT | D371_G380del |

| 14 | DNA-Binding | Exon 13 | c.1144C>T | R382W |

| 2 | DNA-Binding | Exon 13 | c.1145G>T | R382L |

| 9 | DNA-Binding | Exon 13 | c.1145G>A | R382Q |

| 2 | DNA-Binding | Exon 13 | c.1150T>C | F384L |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 13 | c.1166C>T | T389I |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 14 | c.1268G>A | R423Q |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 16 | c.1387_1389delGTG | V463del |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 16 | c. 1396 A>G | N466D |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 16 | c.1397A>G | N466S |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 16 | c.1397A>C | N466T |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 16 | c.1398C>G | N466K |

| 1 | DNA-Binding | Exon 16 | c.1407G>T | Q469H |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 20 | c.1771A>G | K591E |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 20 | c.1865C>T | T622I |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 21 | c.1907C>A | S636Y |

| 10 | SH2 | Exon 21 | c.1909G>A | V637M |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 21 | c.1910T>C | V637A |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 21 | c.1915T>C | P639S |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 21 | c.1970A>G | Y657C |

| 1 | SH2 | Exon 21 | c.2003C>T | S668F |

| 1 | Transactivation | Exon 22 | c.2124C>G | T708S |

| 1 | Transactivation | Exon 22 | c.2129T>C | F710C |

| 1 | Transactivation | Exon 22 | c.2141C>G | T714A |

| 1 | Transactivation | Intron 22 | c.2144+1G>A | p.? |

p.?, unknown effect on protein level

Five mutations, seen in six patients, were heterozygous mutations at the intron-exon boundaries of exons 12 or 22, affecting the DNA binding and transactivation domains, respectively. Each of these intronic mutations led to an incorrect splicing of its neighboring exon (data not shown). Three patients had two distinct heterozygous mutations at the 3’ splice site prior to exon 12, and two patients had distinct mutations in at the 5’ splice site following exon 12. Two of these four mutations were described by Renner et al the other two are novel.13 All four mutations cause exon 12 to be skipped, suggesting an in-frame deletion of amino acids 371–380.

None of 100 healthy controls carried any of the mutations listed in Table II.

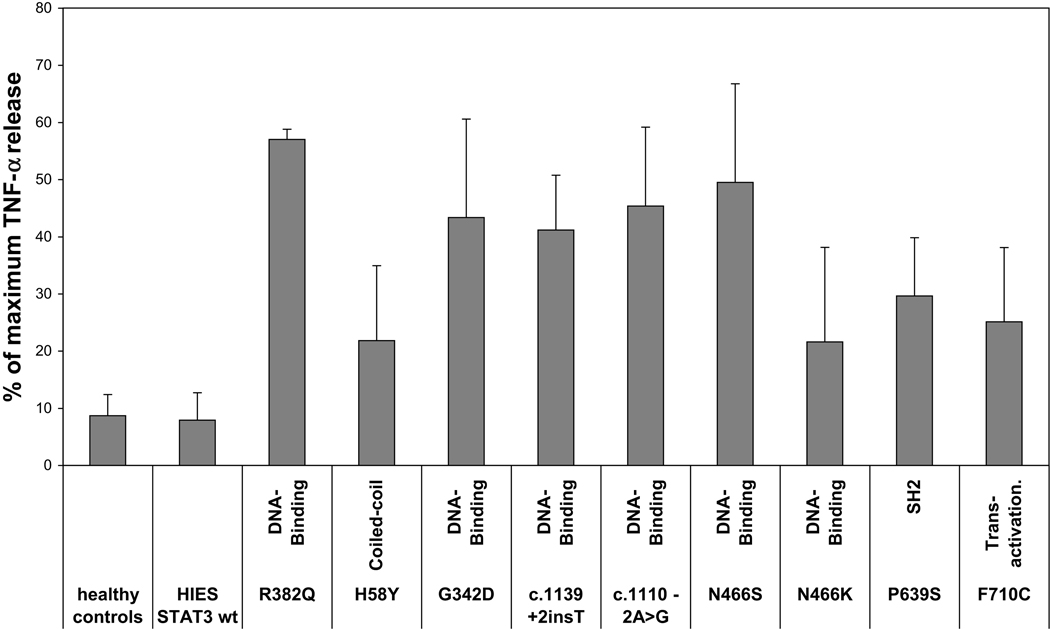

To analyze the effects of the newly observed STAT3 mutation in vitro, we used a TNF-α release assay as described previously by Minegishi et al.5 We pre-incubated monocytes/macrophages of ten patients and eleven healthy controls with IL-10 for one hour and then stimulated with LPS. Eight of the ten patients tested had novel mutations, one was wild-type for STAT3, and one had the previously-reported mutation R382Q. In healthy controls and a STAT3 wild-type patient, IL-10 reduced TNF-α release by approximately 90%, whereas in the R382Q patient, TNF-α release was only reduced by 40%. All eight novel mutations showed a reduction in IL-10-mediated down regulation of TNF-α secretion. We compared the effect of the eight novel mutations collectively to eleven healthy controls by a rank-sum test and reached significance (p<0.0001). However not all mutations had the same effect, suggesting that some mutations may lead to STAT3 proteins with a hypomorphic function and possibly to a milder phenotype (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of TNF-α release in LPS-activated macrophages by IL-10. Macrophages of nine STAT3-mutated patients, eight of whom had novel mutations, one STAT3 wt patient and eleven healthy controls were pre-treated with IL-10 and then stimulated with LPS. Supernatants were examined for the presence of TNF-α. In order to ensure better comparability of data from different healthy donors, the impact of IL-10 on TNF-α release is shown as percentage of maximum TNF-α release upon LPS stimulation.

A substantial portion (36 patients) of our cohort did not have mutations in the coding or splice regions of STAT3. To exclude undetected splice site variants not described in healthy individuals, we sequenced the cDNA from 25 of these patients, none of whom revealed any mutation or exon skipping. Due to the limited availability of samples, the cDNA of eleven patients could not be tested (UPN 21, 28, 35, 38, 58, 78, 80, 82, 88, 105 and 112). While some patients lacking STAT3 mutations also had NIH HIES scores below the likely diagnostic cutoff of 40 points, 20 (56%) had scores ≥40 (see Table E1).

Evaluating the value of the NIH-HIES clinical scoring system

To evaluate the NIH-HIES scoring system,4 we performed three Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to calculate the significance of the association of total clinical HIES score with mutation status. High total HIES score was strongly associated with having a mutation in STAT3 (P-value 3.9e-07). Among those patients with a STAT3 mutation, a high total HIES score may carry some information about whether the mutation is located in the DNA binding domain (P-value 0.094) but was not significantly associated with having a mutation in the SH2 domain, rather than elsewhere in STAT3 (Table E2).

We evaluated whether any cut-off value for the NIH HIES score would be useful for predicting whether a patient has a STAT3 mutation. Using the rule “choose the largest threshold T that gives the smallest error”, leave-one-out testing gave 23% error, 75% sensitivity, and 80.1% selectivity. The optimal cutoff was T=49.5. On the replication set of 50 patients, the cutoff T=49.5 has a sensitivity of 97.0%, but a selectivity of 58.8%. Therefore we sought a smaller and more precise set of features than the NIH HIES score. These seemingly competing objectives could be achieved with a linear support vector machine.

Set of clinical features best predicting the genotype

In search of a minimal set of clinical features associated with STAT3 mutation-positive HIES, we prospectively scored the 100 patients according to the NIH HIES method,4 and performed leave-one-out error estimates for all feature sets tested.

There were twelve sets with a leave-one-out accuracy of 85% (Table E3). By logistic regression of the individual features occurring in at least two feature sets, pneumonia (P = 0.002), lung cysts (P = 0.001) and characteristic face (P = 0.002) were positively associated associated with a STAT3 mutation. Of the twelve sets one had five features, all other sets had more than five features. These five features are i) pneumonia, ii) newborn rash, iii) pathologic fractures, iv) characteristic face of Job syndrome and v) cathedral palate. Notably, a HIES patient does not need to have severe scores for all five features to get a total score above the threshold of 30 points for predicting a STAT3 mutation (Table E4). Detailed information about the five chosen features is summarized in the Online Repository.

Although some clinical features may take years to develop, the misclassification rate on young children (5/37 for age 11 and younger; 2/17 for age 7 and younger) was comparable to those of the entire cohort (see Table E5). Therefore, this set of diagnostic features can also be applied to children suspected of mutations in STAT3.

We applied the score on a control cohort of 28 patients with atopic dermatitis and IgE levels of >1000IU/ml and all had a weighted score of <30 points.

In leave-one-out testing, this set of clinical features in our cohort of suspected HIES patients had a sensitivity of 87.5% for predicting presence of a STAT3 mutation, a specificity of 80.6% and an error rate of 15%. On the replication set of 50 patients, this same set of features had a sensitivity of 93.9%, a specificity of 70.6%, and an error rate of 14%. Increasing the number of features did not improve the quality of our model.

None of the eleven features shown in Table E3 was significantly associated with the domain in which the STAT3 mutation was located, hence no phenotype-genotype correlation can be reported.

Using Th17 cells in HIES as a diagnostic marker - IL17 and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in HIES

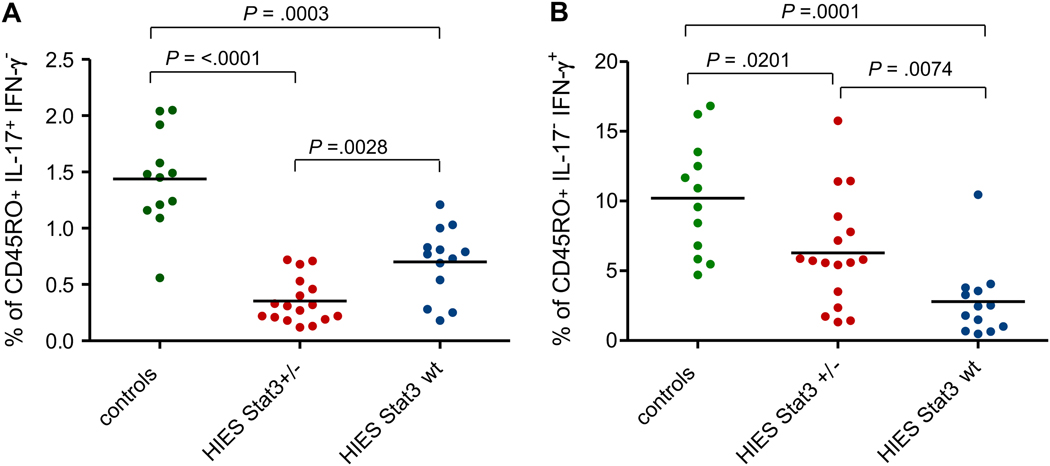

The induction of Th17 cells following stimulation with either the superantigen SEB or the mitogen PMA has been reported to be impaired in HIES patients with STAT3 mutations.13–17 We analyzed the level of Th17 cells among the PBMCs in 30 of our 100 HIES patients and in 12 control subjects. Seventeen of these patients had mutations in STAT3, and 13 did not. Thirteen of the 17 patients harboring mutations in STAT3 had less than 0.5% of IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells. In contrast, all but one of our healthy donors had a frequency of more than 1%. The 13 patients without mutations in STAT3 had significantly more IL-17-producing T cells than the STAT3-deficient patients (P = 0.003), but significantly fewer than the healthy controls (P = 0.0001); only three of these 13 patients had an extremely low frequency of IL-17-producing T cells, less than 0.5% (see Figure 2). No correlation between the lack of Th17 cells, the incidence of Candida infections, or the gender of the patients has been observed (see Table III).

Figure 2.

Percentage of IL-17 (A) and IFN-γ (B) expressing CD4+ memory T cells, determined by intracellular cytokine expression after overnight stimulation with Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB). Each symbol represents the value from an individual donor or patient. Statistical significance was determined with a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. P-values are two-sided. Median values are shown as horizontal bars.

Table III.

Percentages of IL-17 and IFN-γ expressing CD4+ memory T cells in 30 analyzed patients

| UPN | Gender | Age of scoring | Origin | DNA sequence change | Predicted amino acid change | Domain | NIH score* | STAT3 deficiency score§ | % of CD45RO+ IL17+ IFN-γ− cells | % of CD45RO+ IL17− IFN-γ+ cells | Candidiasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | F | 28 | EU | c.1025G>A | G342D | DNA-Binding | 79 | 63.33 | 0.27 | 11.44 | yes |

| 114 | M | 22 | EU | c.1110−2A>G | D371_G380del | DNA-Binding | 70 | 50.00 | 0.32 | 5.57 | yes |

| 086 | M | 13 | EU | c.1110−1G>T | D371_G380del | DNA-Binding | 83 | 76.67 | 0.13 | 5.80 | yes |

| 017 | F | 25 | EU | c.1139+1G>T | D371_G380del | DNA-Binding | 65 | 41.66 | 0.33 | 1.43 | yes |

| 108 | M | 14 | EU | c.1119+2insT | D371_G380del | DNA-Binding | 54 | 31.67 | 0.22 | 3.51 | yes |

| 015 | M | 29 | EU | c.1144C>T | R382W | DNA-Binding | 76 | 63.33 | 0.21 | 15.76 | yes |

| 019 | M | 15 | EU | c.1144C>T | R382W | DNA-Binding | 63 | 48.33 | 0.71 | 5.88 | yes |

| 126 | F | 11 | EU | c.1144C>T | R382W | DNA-Binding | 58 | 40.00 | 0.12 | 7.17 | yes |

| 128 | F | 3 | EU | c.1144C>T | R382W | DNA-Binding | 29 | 38.33 | 0.53 | 1.73 | yes |

| 060 | M | 29 | ME | c.1150T>C | F384L | DNA-Binding | 71 | 55.00 | 0.68 | 1.33 | yes |

| 118 | F | 32 | EU | c.1268G>A | R423Q | DNA-Binding | 59 | 40.00 | 0.19 | 5.43 | no |

| 071 | M | 24 | EU | c.1907C>A | S636Y | SH2 | 71 | 40.00 | 0.31 | 2.36 | yes |

| 016 | F | 39 | EU | c.1909G>A | V637M | SH2 | 68 | 55.00 | 0.18 | 8.90 | yes |

| 115 | M | 19 | EU | c.1909G>A | V637M | SH2 | 56 | 68.33 | 0.72 | 5.72 | nd |

| 125 | M | 16 | EU | c.1909G>A | V637M | SH2 | 58 | 45.00 | 0.22 | 7.79 | no |

| 018 | M | 23 | EU | c.2129T>C | F710C | Transactivation | 58 | 40.00 | 0.46 | 11.41 | yes |

| 116 | M | 8 | EU | c.2141C>G | T714A | Transactivation | 63 | 50.00 | 0.40 | 5.59 | yes |

| 001 | M | 19 | EU | no mutation | 72 | 63.33 | 0.25 | 2.45 | yes | ||

| 004 | M | 17 | EU | no mutation | 60 | 35.00 | 0.79 | 10.46 | yes | ||

| 009 | M | 30 | EU | no mutation | 49 | 25.00 | 0.69 | 1.49 | yes | ||

| 010 | M | 59 | EU | no mutation | 29 | 25.00 | 0.18 | 0.65 | no | ||

| 014 | F | 34 | EU | no mutation | 47 | 21.67 | 0.28 | 1.80 | no | ||

| 020 | F | 9 | EU | no mutation | 32 | 21.67 | 1.00 | 3.28 | no | ||

| 022 | F | 18 | EU | no mutation | 43 | 25.00 | 0.54 | 2.53 | yes | ||

| 054 | M | 21 | EU | no mutation | 29 | 20.00 | 0.83 | 1.01 | yes | ||

| 069 | M | 25 | EU | no mutation | 61 | 48.33 | 1.03 | 4.06 | yes | ||

| 097 | M | 5 | EU | no mutation | 39 | 20.00 | 0.81 | 3.56 | yes | ||

| 113 | F | 5 | EU | no mutation | 39 | 20.00 | 0.73 | 0.67 | no | ||

| 124 | M | 1 | EU | no mutation | 22 | 5.00 | 1.21 | 0.47 | nd | ||

| 127 | F | 7 | EU | no mutation | 49 | 26.67 | 0.77 | 3.80 | yes | ||

UPN, unique patient number

F, Female; M, Male

EU, Europe; ME, Middle East

scoring system described in Grimbacher et al.4

weighted score based on the five cardinal features (recurrent pneumonia, newborn rash, pathologic bone fractures, a characteristic face, and a cathedral palate) shown in Table E4 in the Online Repository. A total number of scaled points greater than 30.0 predicts a STAT3 mutation.

Patients with less than 0.5% CD45RO+ IL17+ IFN-γ− or 5% CD45RO+ IL17− IFN-γ+ cells are shaded.

We measured the frequency of SEB-induced interferon (IFN)-γ producing CD4+ T cells from PBMCs of the same set of subjects (see Figure 2). Interestingly, the patients without a STAT3 mutation had significantly fewer interferon (IFN)-γ producing CD4+ T cells than did healthy controls (P = 0.0001). Of the 13 patients lacking STAT3 mutations, only one had >5% (IFN)-γ producing CD4+ T cells. HIES patients carrying STAT3 mutations also had significantly lower frequencies of interferon (IFN)-γ producing CD4+ T cells than healthy controls (P = 0.02), but significantly higher frequencies than patients without STAT3 mutation (P = 0.007).

We conclude that the lack of Th17 cells is a useful predictive marker for heterozygous mutations in STAT3.

DISCUSSION

In our cohort of 100 patients with suspected HIES, we found 18 novel mutations in STAT3. As these were spread over the whole gene , it appears necessary to sequence the entire STAT3 gene to exclude a possible mutation, an expensive process due to the size of the gene (see Figure 3). The relative frequencies of mutations in Table II however, suggest that a cost-conscious strategy would be to sequence either cDNA or gDNA of STAT3 in the following order: 1) the exons and intron junctions of the DNA-binding domain, 2) the exons and intron junctions of the SH2 domain 3) the exons and intron junctions of the transactivation domain and 4) the rest of the coding sequences. In all HIES patients with detected STAT3 mutations, only one allele was affected, consistent with the observation that complete loss of STAT3 leads to early embryonic death in STAT3 knock-out mice.26

Figure 3.

Schematic structure of STAT3. Every black dot represents one patient carrying the mutation. Patients that carry STAT3 mutations and that were described in previous publication are shown in the upper part of the figure. 5,6, 13–17 The 64 patients identified in this study who had STAT3 mutations are shown in the lower part. The patient carrying a splice site mutation after exon 22 is shown as having DNA sequence change as the effect on the protein is not known.

p.?, unknown effect on protein level

Mutations in the promoter region are possible, but are unlikely to cause HIES when present in heterozygosity because they will not exert a dominant-negative effect which seems necessary for the HIES phenotype. 5

Although over 90% of the mutations we found are located in the exons of STAT3, we found five mutations at the intron-exon boundaries. Four of these mutations caused an in-frame deletion of the 10 amino acids encoded by exon 12. The effect of the splice site mutation on exon 22 is more complex. In healthy individuals, alternative splicing of exon 23 results in two major isoforms of STAT3: STAT3alpha and STAT3beta. While STAT3alpha contains the entire exon 23, STAT3beta lacks the first 50 bp of the same exon.27 The splice site introduced by the mutation one nucleotide after exon 22 causes the 43 bp exon to be skipped. In the wild-type STAT3alpha transcript, this deletion would result in a frame shift and possibly nonsense mediated decay. However, in conjunction with the shortened exon 23 of STAT3beta, this deletion is predicted to produce a transcript coding for STAT3alpha with an in-frame deletion of amino-acids 701– 732, which would encompass both the tyrosine and serine phosporylation sites of STAT3alpha (see Figure E1).

All eight novel mutations that we tested deteriorated the suppression of LPS-induced production of TNF-α by the IL-10/JAK/STAT3 pathway in the patients’ macrophages. Compared to the most prevalent mutation affecting the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 (R382Q), this effect was less prominent in some of the novel mutations. This result could reflect the fact that some mutations have a different impact on the retained functionality of the STAT3 dimerization, nuclear translocation, or transcriptional activation.

We confirm that HIES patients carrying STAT3 mutations have significantly reduced numbers of IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells. Based on these data, we suggest that Th17 cells may be used as an additional marker to distinguish between HIES patients with or without STAT3 mutations.

Patients without STAT3 mutations had a striking reduction of IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells. This cytokine imbalance has been previously described in HIES and may be explained by an intrinsic T cell defect.28 In our HIES cohort of STAT3 wt patients, only three of 13 had less than 0.5% IL-17-producing T cells. These three patients may have defects in other proteins involved in STAT3 signalling or in the differentiation of Th17 cells.

Proposed set of diagnostic features for STAT3-mutant HIES

HIES with mutations in STAT3 is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. Therefore, STAT3-mutated HIES patients have a 50% risk of transmitting the disease to each of their offspring.4,6 Thus, a positive family history contributes to the risk of having HIES. In addition clinical features have been observed to accumulate over time as affected children get older.1 Hence, any diagnostic algorithm is likely to underdiagnose young patients. However, adding an age feature did not improve our SVM classifier.

Conclusions

Based on data from our multicenter cohort, we propose the following diagnostic guidelines for STAT3-mutant HIES:

Possible: IgE ≥1000 IU/mL plus a weighted score of clinical features >30 based on recurrent pneumonia, newborn rash, pathologic bone fractures, characteristic face, and high palate (see Table E4).

Probable: Above plus lack of Th17 cells or a family history for definitive HIES.

Definitive: Above plus a dominant-negative heterozygous mutation in STAT3.

We caution, however, that none of the scores should be used to keep physicians from pursuing a molecular diagnosis in a particular patient. HIES patients accrue findings over time. Aggressive treatment with antibiotics can forestall infectious complications that would be diagnostic if allowed to occur. Moreover, the unique feature of HIES that abscesses or other infections are 'cold', or not accompanied by a normal intensity of pain or inflammation, has not been captured by any score, but should increase clinical suspicion. HIES scoring will not replace good clinical judgment, but may help the diagnostic process.

The aim of the proposed guidelines is to discern HIES patients carrying mutations in STAT3 to facilitate time- and resource-saving diagnosis of patients, thereby leading to an early and effective treatment. This screening tool will need to be evaluated and updated as new knowledge is revealed and new mutations causing HIES are identified. We acknowledge that most clinicians will continue to diagnose HIES with its key clinical features such as recurrent pneumonia, lung cysts, typical facies, retention of primary teeth and pathological fractures, When it comes to the question whether or not to evaluate STAT3, however, the above scoring should be used.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients and their families and we would like to acknowledge the help of J. Milner in improving our Th17 cells staining.

Declaration of all sources of funding:

This research was funded in part by the European grant MEXT-CT-2006- 042316 to B.G., a grant of the Primary Immunodeficiency Association (PIA) provided by GSK, the European consortium grant EURO-PADnet HEALTH-F2-2008-201549, the grant OTKA49017 to L.M., the foundation C. Golgi from Brescia to A.P., the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NLM (E.M.G., A.A.S.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (A.P.H., A.F.F., J.N.D., S.M.H.) and in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400.

Abbreviations Used

- HIES

Hyper-IgE Symdrome

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- gDNA

genomic DNA

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PMA

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- SEB

Staphylococcus enterotoxin B

- SH2

Src homology 2

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- SVM

Support vector machine

- UPN

Unique patient number

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Clinical Implications

These diagnostic guidelines for STAT3-deficient HIES will facilitate time- and resource-saving diagnosis of the patients, thereby leading to an early and effective treatment.

Capsule Summary

The diagnostic guidelines for STAT3-deficient HIES will aid the diagnostic process of HIES patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grimbacher B, Holland SM, Gallin JI, Greenberg F, Hill SC, Malech HL, et al. Hyper-IgE syndrome with recurrent infections – an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:692–702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis SD, Schaller J, Wedgwood RJ. Job's syndrome: recurrent, "cold", staphylococcal abscesses. Lancet. 1966;287:1013–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckley RH, Wray BB, Belmaker EZ. Extreme hyperimmunoglobulinemia E and undue susceptibility to infection. Pediatrics. 1972;49:59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimbacher B, Schäffer AA, Holland SM, Davis J, Gallin JI, Malech HL, et al. Genetic linkage of hyper-IgE syndrome to chromosome 4. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:735–744. doi: 10.1086/302547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Tsuchiya S, Tsuge I, Takada H, Hara T, et al. Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2007;448:1058–1062. doi: 10.1038/nature06096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1608–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray PJ. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway: input and output integration. J Immunol. 2007;178:2623–2629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reich NC, Liu L. Tracking STAT nuclear traffic. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:602–612. doi: 10.1038/nri1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy DE, Lee CK. What does Stat3 do? J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1143–1148. doi: 10.1172/JCI15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong C. TH17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;5:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nri2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Happel KI, Dubin PJ, Zheng M, Ghilardi N, Lockhart C, Quinton LJ, et al. Divergent roles of IL-23 and IL-12 in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 2005;202:761–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renner ED, Rylaarsdam S, Aňover-Sombke S, Rack AL, Reichenbach J, Carey JC, et al. Novel signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) mutations, reduced TH17 cell numbers, and variably defective STAT3 phosphorylation in hyper-IgE syndrome. Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milner JD, Brenchley JM, Laurence A, Freeman AF, Hill BJ, Elias KM, et al. Impaired TH17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–776. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma CS, Chew GYJ, Simpson N, Priyadarshi A, Wong M, Grimbacher B, et al. Deficiency of Th17 cells in hyper IgE syndrome due to mutations in STAT3. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1551–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Beaucoudrey L, Puel A, Filipe-Santos O, Cobat A, Ghandil P, Chrabieh M, et al. Mutations in STAT3 and IL12RB1 impair the development of human IL-17-producing T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1543–1550. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao H, Tóth B, Erdős M, Fransson I, Rákóczi E, Balogh I, et al. Novel and recurrent STAT3 mutations in hyper-IgE syndrome patients from different ethnic groups. Mol Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renner ED, Puck JM, Holland SM, Schmitt M, Weiss M, Frosch M, et al. Autosomal recessive hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome: a distinct disease entity. J Pediatr. 2004;144:93–99. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimbacher B, Holland SM, Puck JM. Hyper-IgE syndromes. Immunol Rev. 2005;203:244–250. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moin M, Farhoudi A, Movahedi M, Rezaei N, Pourpak Z, Yeganeh M, et al. The clinical and laboratory survey of Iranian patients with hyper-IgE syndrome. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:898–903. doi: 10.1080/00365540600740470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buettner M, Meinken C, Bastian M, Bhat R, Stössel E, Faller G, et al. Inverse correlation of maturity and antibacterial activity in human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:4203–4209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vapnik V. The nature of statistical learning theory. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gertz EM, Wright SJ. Object-oriented software for quadratic programming. ACM TOMS. 2003;29:58–81. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joachims T. Making large-scale SVM learning practical. In: Schölkopf B, Burges C, Smola A, editors. Advances in Kernel Methods – Support Vector Learning. Cambridge, USA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda K, Noguchi K, Shi W, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, Yoshida N, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat3 gene leads to early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3801–3804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maritano D, Sugrue ML, Tininini S, Dewilde S, Strobl B, Fu XP, et al. The STAT3 isoforms α and β have unique and specific functions. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:401–409. doi: 10.1038/ni1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, van der Meer JWM. Severely impaired IL-12/IL-18/IFNγ axis in patients with hyper IgE syndrome. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005;35:718–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.