Abstract

A forefront of the research on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the interaction of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides with redox metal ions (e.g., Cu(II), Fe(III) and Fe(II)) and the biological relevance of the Aβ-metal complexes to neuronal cell loss and homeostasis of essential metals and other cellular species. This work is concerned with the kinetic and mechanistic studies of the ascorbic acid oxidation reaction by molecular oxygen that is facilitated by Cu(II) complexes with Aβ(1–16), Aβ(1–42), and aggregates of Aβ(1–42). The reaction rate was found to linearly increase with the concentrations of Aβ-Cu(II) and dissolved oxygen, and be invariant with high ascorbic acid concentrations. The rate constants were measured to be 117.2 ± 15.4 and 15.8 ± 2.8 M−1s−1 at low (<100 µM) and high AA concentrations, respectively. Unlike free Cu(II), in the presence of AA, Aβ-Cu(II) complexes facilitate the reduction of oxygen by producing H2O2 as a major product. Such a conclusion is drawn on the basis that the reaction stoichiometry between AA and O2 is 1:1 when Aβ concentration is kept at a much greater value than that of Cu(II). A mechanism is proposed for the AA oxidation in which the oxidation states of the copper center in the Aβ complex alternates between 2+ and 1+. The catalytic activity of Cu(II) towards O2 reduction was found to decrease in the order of free Cu(II) > Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II) > Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) > Cu(II) complexed by the Aβ oligomer/fibril mixture > Cu(II) in Aβ fibrils. The finding that Cu(II) in oligomeric and fibrous Aβ aggregates possesses considerable activity towards H2O2 generation is particularly significant, since in senile plaques of AD patients the co-existing copper and Aβ aggregates have been suggested to inflict oxidative stress through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Although Cu(II) bound to oligomeric and fibrous Aβ aggregates is less effective than free Cu(II) and the monomeric Aβ-Cu(II) complex in producing ROS, in vivo the Cu(II)-containing Aβ oligomers and fibrils might be more biologically relevant given their stronger association with cell membranes and the closer proximity of ROS to cell membranes.

Introduction

The pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) include the formation of senile plaques composed of mainly amyloid-β (Aβ) variants of 40–43 residues, a dramatic loss of neuronal cells, and extensive oxidative stress.1–3 More intriguing is the fact that inside the senile plaques high levels of metals are accumulated.4–6 Consequently, recent years have seen an enormous interest in the interaction between metal and Aβ and the possible roles of the metal-Aβ complexes in the AD pathogenesis.7–19 Although it is still not clear how extensive oxidative stress in AD-afflicted brain occurs, it is becoming evident that the redox active metals (e.g., Cu(II) and Fe(III)) are involved in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the aggravation of oxidative stress.3,19–21 Hence, in order to probe the role of metals and Aβ, a key issue is to understand the redox properties of the complexes of metals with Aβ and possible redox reactions of these complexes with biological species. Our group,16,22 among others,14,15 have systematically elucidated the redox properties of Aβ complexes with copper and iron. Findings from these efforts have improved our understanding of the metal-initiated production of ROS.

It has been well documented that Aβ binds copper with its hydrophilic domain (residues 1–16) through the three histidine residues at positions 6, 13, and 14.7 Other binding sites proposed for the Cu(II) binding include the amine and carboxylate groups of aspartic acid at the N-terminus, the tyrosine residue at position 10 and other carboxylates in the hydrophilic domain (For a comprehensive review please see Ref. 7). At least two binding modes with varying binding affinities have been proposed, and investigations on the detailed binding modes have continued.8,9,13,23–26 The binding (affinity) constants reported thus far have ranged from micromolar to attomolar,10,26–31 with most values lying between submicromolar and nanomolar.10,26,29,31 Such a large variation has been suggested to be a result of the differences in the concentrations of Aβ and Cu(II), buffer systems, Aβ sample preparations, and even data interpretations. The impact of these differences on the measurement of the binding affinity and stoichiometry between Cu(II) and Aβ has been reviewed and rationalized by recent reviews.7,13 Despite these conflicting results, it is generally agreed that Cu(II) binds to Aβ strongly and the resultant complexes are possibly related to oxidative stress (either as a proxidant or an antioxidant or a dual role of proxidant and antioxidant).12–19

In vitro, the Aβ-Cu(II) complex, in the presence of an electron donor (reductant), has been shown to reduce O2 to produce H2O2.15,32 Recently, we successfully measured the redox potential of the complex and suggested that thermodynamically a number of biological species are capable of reducing Aβ-Cu(II) to Aβ-Cu(I).16 Aβ-Cu(I) in turn can reduce O2 and generate H2O2. Overall, the net effect is that Aβ-Cu(II) facilitates the oxidation of a biological species and the reduction of molecular oxygen, generating H2O2 as a ROS, as shown by reaction (3).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Red and Ox represent the reduced and oxidized forms of a biological species, respectively. For reductant that can receive two electrons (e.g., ascorbic acid), reaction (3) becomes Red + O2 + 2H+→ Ox + H2O2 or the stoichiometry between Red and O2 is 1:1. Under normal circumstance without Aβ-Cu(I), reaction (3) would proceed very slowly, imposing no significant effect on the normal functions of cellular species. In contrast, in the presence of Aβ-Cu(I), reaction (3) may be dramatically accelerated, and both the biological species and molecular O2 would be depleted, adversely impacting many biological processes.16,33

The mixture of Aβ and Cu(II) (in many studies containing both complexed and free Cu(II)) has been reported to accelerate the oxidation of catechol and dopamine by H2O2.34,35 In this aspect, the mixture was proposed to act like an enzyme (or catalyst) for the oxidation reactions of these species. Ascorbic acid (AA), present as ascorbate anion at physiological pH, is a broad spectrum antioxidant (reductant) that acts against many ROS, and is present abundantly in central nerve system (ranging from 500 µM in cerebrospinal fluid to 10 mM in neurons).36 It has been reported that AD patients have a significantly lower antioxidant capacity in cerebral fluid than control subjects.37 On the basis of the redox potentials of AA and the Aβ-Cu(II) complex,16 its reaction with Aβ-Cu(II) is thermodynamically favored. As such, its oxidation facilitated by Aβ-Cu(II), similar to that shown in reaction (3), ought to occur. Given its biological importance and the implication of Aβ-Cu(II) to the pathogenesis of AD, the study of the oxidation kinetics should provide insight into the role of Aβ-Cu(II) in the development of AD.

Oxygen is also abundant in brain and is vital for a variety of brain functions.20 It has been assumed that the complex formed between Cu(II) and Aβ(1–42) participates in the reduction of molecular oxygen to hydroxyl radicals through the route O2 → O2 − • → H2O2 → OH•.12 A recent theoretical paper by Hewitt and Rauk shows that the conversion of O2 to H2O2 in the presence of the reduced form of Aβ-Cu(II) (i.e., Aβ-Cu(I)) does not have to proceed via the superoxide O2 − • intermediate.32 Results recently obtained by Baruch-Suchodolsky and Fischer12 and Faller’s group14 have suggested that Aβ peptides (especially Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42)) may serve as scavengers of OH•. In the work by Baruch-Suchodolsky and Fischer, the Aβ-Cu(I) complex was formed between Aβ and Cu(I) without first reducing Aβ-Cu(II) through a reductant.12,38 Interestingly, Guilloreau et al. showed that the amount of OH• generated by Aβ(25–35), the segment that does not contain the Cu(II) binding domain but possesses the easily oxidizable methionine residue at position 35, is much greater than that produced by Aβ(1–16) or Aβ(1–42).14 This observation suggests that Cu(II) complexed by Aβ(1–16) or Aβ(1–42) is less capable than free Cu(II) of generating OH• (i.e., more capable of inhibiting OH• generation). Although many studies have focused on the production of H2O2 from O2,16,32 it is not certain whether H2O2 produced with the aid of the Aβ-Cu(I) complex can further decompose to OH•.

The oxidation kinetics of AA has been extensively investigated employing both free Cu(II) or Cu(II) complexes.39–41 Depending on the ligands coordinating the Cu(II) center, the kinetics and mechanisms of the AA oxidation vary significantly. For example, when Cu(II) is coordinated by poly-4-vinylpyridine, its catalytic activity toward the AA oxidation increases by four orders of magnitude.42 The copper(II)-catalyzed AA oxidation, in the presence or absence of strong ligands, is generally believed to proceed by an alternating reduction-oxidation mechanism with the formation of an intermediate of cuprous (Cu(I)) species.42,43 Nonetheless, AA oxidation catalyzed by histidine (His) ligated copper proceeds via a different mechanism in which a ternary complex of O2–(His-Cu)–AA is formed.40 Furthermore, although in the presence of an electron donor and Aβ-Cu(II) H2O2 has been detected and the reaction has been proposed to proceed along the pathway outlined by reactions (1)–(2), it is not clear if H2O2 is the exclusive product or if other ROS are also generated. To elucidate the potential involvement of Aβ-Cu(II) in the AD pathogenesis, it is necessary to further investigate the mechanism of oxygen reduction facilitated by the Aβ-Cu(II) complex in a milieu similar to biological conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, the rate of the Aβ-Cu(II)-facilitated AA oxidation by O2 has not been determined and the dependence of this rate on the concentrations of Aβ, Cu(II), AA, and O2 has not been thoroughly assessed. Furthermore, although it has been shown that Aβ fibrils bind to Cu(II) as strongly as Aβ monomers,25 the ability of the Cu(I)-containing fibrils in scavenging OH• appears to be diminished with respect to that of the complex between Aβ monomer and Cu(I).12 We are therefore also interested in whether the aggregation of Aβ in the presence of Cu(II) may affect the rate of H2O2 production. In this work, we investigated the effect of Aβ-Cu(II) on AA oxidation by molecular oxygen, the oxidation reaction kinetics and the stoichiometry of the reaction. The differences in reactivity and mechanism between free Cu(II) and Aβ-Cu(II) are compared and discussed. Such a study sheds light onto the possible role of Aβ as a neuroprotective agent or a toxin, an ambiguity that has long been under debate.12,44,45 We also compared the activity of Aβ-Cu(II) in monomeric and aggregate forms in facilitating the O2 reduction to gain a better understanding of their relative toxicities in terms of their abilities to deplete biological species and to produce hydrogen peroxide. With the rate constant known, we should be able to learn how rapidly important biological redox species are consumed in the Aβ-Cu(II)-facilitated O2 reduction reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Lyophilized Aβ(1–16) (DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK) was synthesized by Genemed Synthesis (San Antonio, TX), and purified in-house using HPLC. Aβ (1–42) (DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVVI) was purchased from American Peptide Co. Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade (Sigma-Aldrich). Throughout the work, 1 mM CuCl2 dissolved in 1 mM H2SO4 was used as the Cu(II) stock solution. Aβ(1–16) samples were prepared freshly by dissolving lyophilized powder samples in deionized water, while Aβ(1–42) samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and subsequently diluted with phosphate buffer to desired concentrations. The AA stock solution (10 mM) was prepared before use.

Phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.2) was employed for the kinetic experiments and preparations of Aβ(1–42) aggregates with or without Cu(II). The buffer was prepared with deionized water (18 MΩ·cm−1), followed by being passed through a Chelex 100 column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, Hercules, CA) to rid of the trace heavy metals. Using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), we found that concentrations of heavy metal ions after such a treatment were below 1 nM.

Kinetic Measurements

The AA oxidation was followed by UV-vis spectrophotometry (Cary 100 Bio, Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). The kinetic experiments were conducted at 25 °C in phosphate buffer (pH, 7.2). At this pH, AA exists predominately in the ascorbate monoanion form and throughout this work we use AA interchangeably to represent the ascorbate monoanion.40 The initial oxidation rates of AA were measured from the decrease of absorbance at 265 nm, where AA shows a maximum absorption (ε = 1.5×104 M−1cm−1).40 Within the initial 100 s, the absorbance decreases linearly with time. The initial reaction rate (V0) is therefore taken as m/εl (where m is the slope of the linear portion of the curve, ε the ascorbate absorption coefficient at 265 nm, and l the optical path length of the cuvette).

Under our experimental conditions, the autooxidation rate of AA without Aβ-Cu(II) was found to be always < 0.1 nM s−1. The oxygen contents in the sample were controlled by equilibrating the sample solution with N2-O2 gas mixtures of different compositions. Introducing the gas mixture into the solution was performed in a glove box (Plas Lab Inc., Lansing, MI) that was maintained under a N2 atmosphere with a O2 content less than 1 ppm. The N2 and O2 flows in the gas mixtures were regulated by mass flow controllers (Hastings Instruments, Hampton, VA) before being mixed in a stainless chamber and introduced into the solution. Prior to each experiment, the initial oxygen concentration was measured by a dissolved oxygen membrane electrode (080515MD, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The Aβ-Cu(II) complex was freshly prepared by adding Cu(II) to an Aβ (i.e., either Aβ(1–16) or Aβ(1–42)) solution. In order to minimize the free Cu(II) concentration, unless otherwise stated, the [Aβ]/[Cu(II)] ratio was always kept at 20/1. At such a ratio, even if the binding constant between Aβ and Cu(II) were in the sub-µM range,10,26,29,31 copper would still exist predominantly in the form of a complex. We should emphasize that any uncomplexed Cu(II) can catalyze the reduction of H2O2 to generate OH• (via the Harber–Weiss-like mechanism) as shown by the recent work of Guilloreau et al.14 Therefore, keeping the free Cu(II) concentration at the minimum by using a high [Aβ]/[Cu(II)] ratio is critical for avoiding such a complication. The Cu(II)-containing Aβ(1–42) aggregates were prepared by either preincubating Aβ(1–42) solution at 37 °C for a desired amount of time and then mixing with Cu(II) or incubating an Aβ(1–42)/Cu(II) mixture. In kinetic experiments, the abovementioned Aβ/Cu(II) mixture was spiked with AA and mixed with buffer equilibrated with a N2-O2 gas mixture.

Electrochemical Measurements

The electrochemical experiments were performed on a CHI 411 electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments, Austin, TX) using a homemade plastic electrochemical cell. A glassy carbon disk electrode and a platinum wire were used as the working and counter electrodes, respectively. The reference electrode was Ag/AgCl, and all of the potential values are reported with respect to this electrode unless otherwise stated. Prior to each experiment, the glassy carbon electrode was polished with diamond pastes of 15 and 3 µm and alumina pastes of 1 and 0.3 µm in diameter (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL). The electrolyte solution was a phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M NaNO3. The Aβ(1–16) stock was diluted with the same phosphate buffer to desired concentrations. In order to examine the reaction between AA and Aβ-Cu(II) without the complication from oxygen, the experiments were conducted in the same glove box under a N2 atmosphere.

Atomic force microscopy

AFM images were obtained on an MFP-3D-SA microscope (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with a tapping mode. Lyophilized Aβ(1–42) was dissolved in 20 mM NaOH solution to prepare 1 mM stock solution. To generate Cu(II)-containing Aβ(1–42) aggregates, 200 µM Aβ(1–42) with or without 20 µM Cu(II) was incubated at 37 °C for a desired period of time. Aliquots of Aβ(1–42) or Aβ(1–42)/Cu(II) were taken out at predetermined incubation times, cast onto newly peeled mica, and left in contact with the mica substrate for 15 min. Thereafter, the slides were gently rinsed with water to remove any residual salt, and dried with nitrogen before imaging.

Results

Dependence of the AA Oxidation Rate on Its Concentration

Figure 1 shows that within 10–240 µM, the initial rate of AA or ascorbate oxidation varies with its concentration when 10 µM Aβ-Cu(II) and 240 µM O2 are also present. The rate increases with [AA] almost linearly below 100 µM. As [AA] increases, the rate reaches a steady state. Although the rate-concentration dependence is characteristic of an enzymatic reaction, additional experimental results (vide supra) suggest a different reaction mechanism, which will be detailed in the Discussion Section.

Figure 1.

Dependence of the initial oxidation reaction rate of AA on its concentration. The rate was measured at room temperature with [O2] = 240 µM and [Aβ-Cu(II)] = 10 µM. Each data point is the average of at least three replicate measurements, and the RSD values, ranging from 1.9 to 13.2%, are represented by the error bars.

Dependence of the AA Oxidation Rate on the Oxygen Concentration

Figure 2 shows the variation of the rate of AA oxidation with the oxygen concentration when [AA] and [Aβ-Cu(II)] were fixed at 240 and 10 µM respectively. Notice that we chose an initial AA concentration that far exceeds the upper limit of the linear range in Figure 1 so that AA is not the limiting reagent. Within 4.6–1170.1 µM [O2], the AA oxidation rate was found to increase linearly with [O2]. This contrasts the observation of a plateau at higher [O2] when the histidine-Cu(II) complex was used as the catalyst,40 suggesting that a different mechanism is at work.

Figure 2.

The dependence of AA oxidation rate on the O2 concentration. The rate was measured at room temperature with [AA] = 240 µM and [Aβ-Cu(II)] = 10 µM. Each data point is the average of at least three replicate measurements, and the RSD values, ranging between 2.8 and 32.8%, are represented by the error bars

Dependence of the initial AA oxidation rate on [Aβ-Cu(II)]

To further probe the AA oxidation or O2 reduction mechanism, we investigated the effect of [Aβ-Cu(II)] on the AA oxidation rate. As shown in Figure 3, the initial AA oxidation rate also exhibits a linear relationship with the amount of [Aβ-Cu(II)] introduced to the sample solution. Notice that the solutions studied were saturated with air and contained a high [AA] so that these reactants are again not the limiting reagents.

Figure 3.

The effect of [Aβ-Cu(II)] on the initial AA oxidation rate. The rates were obtained with [AA] = 240 µM in an air-saturated solution. Each data point is the average of at least three replicate measurements, and the RSD values, ranging between 3.5 and 9.5%, are represented by the error bars.

The major product of oxygen reduction by AA that is facilitated by Aβ-Cu(II) is H2O2

The reduction of O2 can form either H2O or H2O2 or both. In most studies,40,43 even in the presence of a catalyst,41,43 H2O2 is assumed to be the product. However, usually, free Cu(II) catalyzes the decomposition of H2O2 as follows:12,46

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

The above reactions have been shown to be relevant to the inhibition of OH• through the Cu(II) complexation by Aβ.14 Reactions (4)–(5) are essentially the Harber–Weiss reaction12,46 producing the hydroxyl radical OH• and reaction (6) is basically the Fenton reaction.47 Thus, free Cu(II) decomposes H2O2 and produces the highly reactive hydroxyl radical.

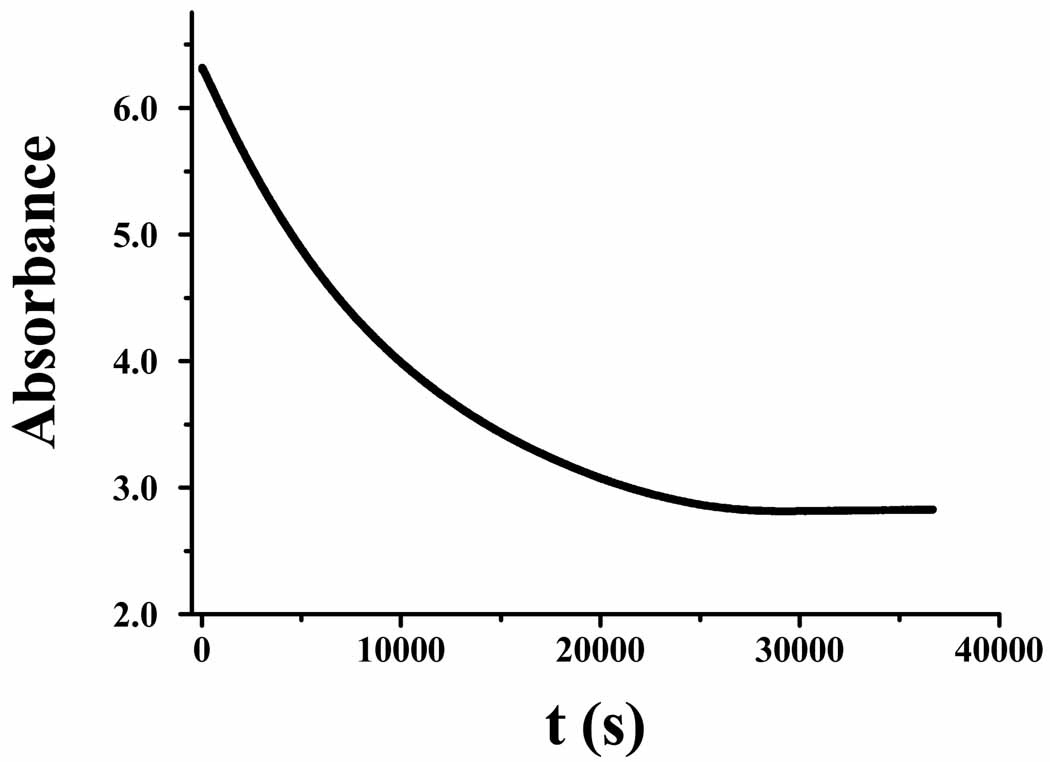

For the reduction of oxygen by AA, it would be interesting to observe if the reaction is affected by the coordination of the metal ion. Along this line, we probed the reaction stoichiometry of the oxygen reduction catalyzed by free Cu(II) and compared it to that facilitated by the Aβ-Cu(II) complex. In a gastight cuvette that contained a solution with known amounts of O2 and Aβ-Cu(II) and excess AA, the AA absorbance was monitored (Figure 4). As soon as oxygen was depleted, the reaction stopped. By calculating the amount of AA consumed, we obtained the stoichiometry of the oxidation reaction. In the presence of Aβ-Cu(II), the molar ratio between the consumed AA and O2 is always close to 1:1. This suggests that H2O2 is the final product of the reaction AA + O2 + 2H+ → dehydroascorbate + H2O2. In line with the results reported by us16 and others,32 Aβ-Cu(II), upon reduction by a reductant (e.g., AA), can accelerate the reduction of oxygen to H2O2 instead of H2O. In sharp contrast, when only free Cu(II) was used, the ratio was found to vary between 1.5 and 2. Such a ratio is indicative of hydroxyl radical formation (or H2O production from the four-electron reduction of O2), an observation consistent with that reported by Faller’s group.14

Figure 4.

Change of AA absorbance as a function of reaction time in an air-saturated solution containing 10 µM Aβ-Cu(II) and 420 µM AA.

Aβ-Cu(II) can oxidize ascorbic acid

It has been reported that His-Cu(II) catalyzes the oxidation of AA by oxygen via the formation of a ternary intermediate among O2, His-Cu(II) and AA.40 This contrasts the alternating reduction and oxidation mechanism that involves Aβ-Cu(II) and Aβ-Cu(I). The absence of the His-Cu(II) reduction when the complex was mixed with AA was taken as the proof of the mechanism.40 Interestingly, Aβ-Cu(II) has a higher oxidation potential than AA,14,16 and consequently should be able to convert AA to dehydroascorbate. Determining whether and how fast the reaction occurs will help pinpoint the exact reaction mechanism. To this end, we collected cyclic voltammograms of Aβ-Cu(II) in the absence and presence of AA.

The CV of Aβ-Cu(II) (red curve) exhibits a pair of oxidation (Epa = 0.20 V in Figure 5) and reduction (Epc = −0.05 V) peaks. This observation is consistent with our previously reported voltammograms.16 Specifically, Aβ-Cu(II) is reduced to Aβ-Cu(I) which can be reversibly oxidized back to Aβ-Cu(II). When an equivalent amount of AA was added, the characteristic irreversible AA oxidation peak was not observed (blue curve) and only the CV of Aβ-Cu(I) appeared. This indicates that within seconds the redox reaction between Aβ-Cu(II) and AA was completed. Further addition of AA generated a CV showing the AA oxidation peak at 0.37 V (black curve), which is slightly more positive than that of AA only (0.30 V; see also the inset of Figure 5). The oxidation peak is resulted mainly from the excessive and unoxidized AA. A careful examination of the initial scan of the CV shown as the black curve reveals a small shoulder peak at ~0.20 V, suggesting that Aβ-Cu(I) has been generated. The slight shift of the AA oxidation peak and the peak broadening may result from the contribution of the Aβ-Cu(I) oxidation.

Figure 5.

The cyclic voltammograms of a solution containing 400 µM Aβ and 200 µM Cu(II) (red curve) and the same mixture spiked with 100 µM (blue curve) and 200 µM (black curve) AA. The inset shows the CV of AA only. The experiment was conducted at room temperature under a N2 atmosphere in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 0.1 M NaNO3 as the supporting electrolyte.

O2 reduction rates in the presence of Cu(II) complexes formed with Aβ peptides of different lengths and with different aggregates

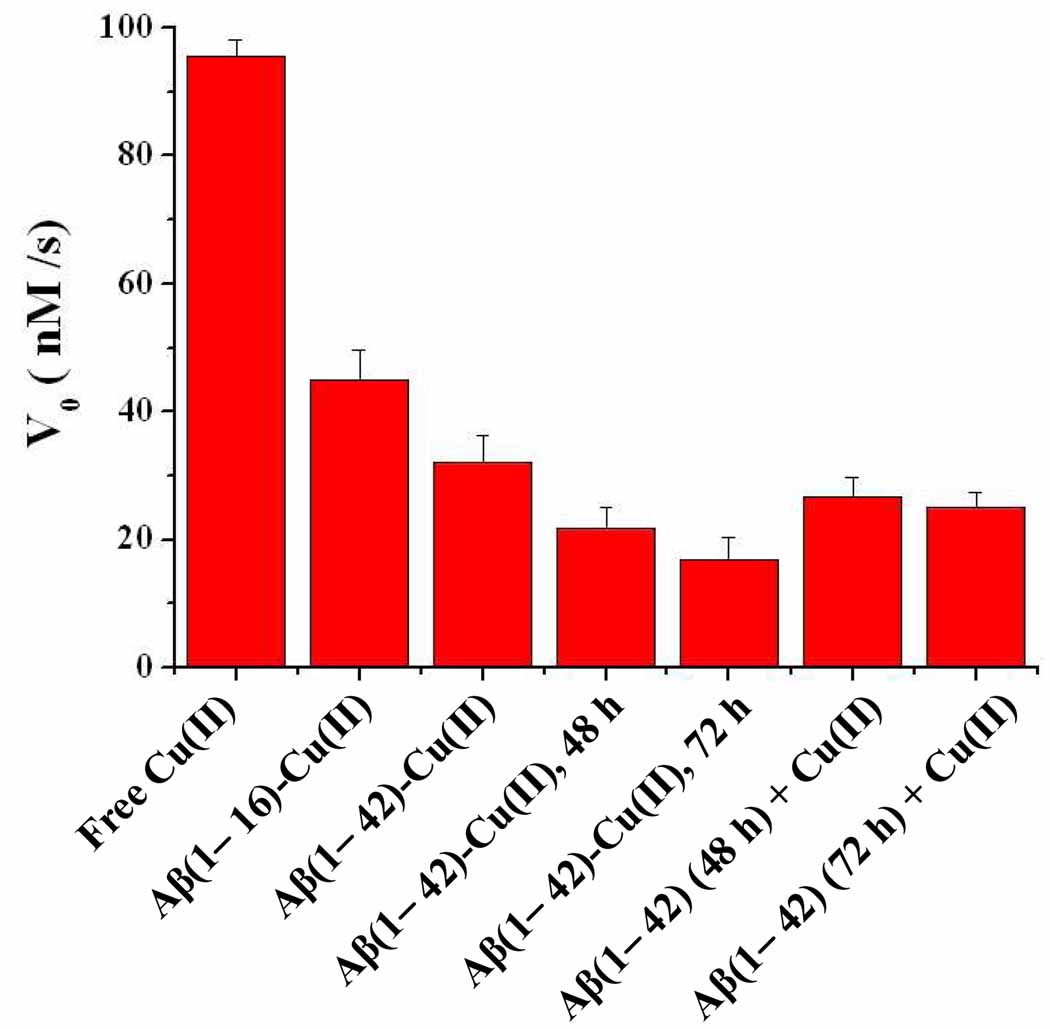

We16 and others15,21 have shown that H2O2 can be measured as a stable product from the Aβ-Cu(II)-facilitated O2 reduction by a biological reductant. By comparing Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II), Aβ(1–28)-Cu(II), and Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II), we have also shown that the amount of H2O2 produced decreases with the peptide length. The coordination environment of Cu(II) was attributed to the difference in the reactivity. In AD-afflicted brain, Cu(II) is bound to Aβ variants of 40–43 residues and accumulated in senile plaques.48 Thus far, even though it is evident that Aβ aggregates can sequester Cu(II) essentially as strongly as the Aβ monomer,25,30 it is not clear if Cu(II) complexed by different Aβ aggregates can still facilitate the oxygen reduction reaction in the presence of AA. Gaining insight into this question should help unravel the role of metal-containing Aβ aggregates in inflicting oxidative stress. To this end, we compared the reaction rates of the AA oxidation reaction in the presence Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II), Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II) and Cu(II) bound by a mixture of Aβ(1–42) oligomers and fibrous aggregates. Shown in Figure 6 is the initial AA oxidation rates observed in the presence of these Cu(II)-containing species. Not surprisingly, free Cu(II) has the highest catalytic activity, and the coordination environment rendered by Aβ(1–16) and Aβ(1–42) (labeled as “Aβ(1–16)-Cu(II)” and “Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II)” in Figure 6, respectively) indeed has a significant influence on the activity of the respective complex. The decrease of reactivity with peptide length should be due to the aforementioned steric hindrance to the accesses of Cu(II) center by oxygen.16 Interestingly, Cu(II) bound by Aβ(1–42) aggregates (cf. bars labeled as “Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II), 48 h” and “Aβ(1–42) (48 h) + Cu(II)” in Figure 6, for example) can still facilitate the AA oxidation by O2, though the reaction rate is much slower. The morphologies of incubated Aβ(1–42) are shown in Figure 7. At the beginning of the incubation, only a few globular aggregates of diameters around 5–8 nm (i.e., oligomers in images A and C) were present, whereas at 48 h of incubation protofibrils and fibrils coexist with some oligomers (images B and D). Adding Cu(II) into the Aβ(1–42) monomers followed by incubation (image B) or into a preincubated Aβ(1–42) solution (image D) produced similar aggregate mixtures. Incubation of Aβ(1–42) in the presence of Cu(II) results in the production of only a few amorphous aggregates (cf. the marked particle in image B whose height is larger than 5–8 nm). This is expected since the Aβ(1–42) concentration used for the experiments is much higher than the Cu(II) concentration. After 72 h incubation, the population of fibrous aggregates for both types of incubation becomes even greater with little oligomers and protofibrils discernable (data not shown). It is evident from Figure 6 that the fibrous aggregates, similar to the Aβ monomer, can also attenuate the ability of Cu(II) towards the AA oxidation. Given that free Cu(II) has a substantially higher catalytic activity, the lower activity in the incubated Aβ samples that was later spiked with Cu(II) suggests that the Cu(II) added must be sequestered (complexed) by the preformed aggregates. This is consistent with the finding reported by Karr and Szalai.25

Figure 6.

Comparison of reaction rates of the AA oxidation in the presence of various Cu(II)-containing Aβ species. The rate was obtained under the conditions of 240 µM AA, 10 µM Cu(II), and 240 µM Aβ in air-saturated phosphate buffer solutions (pH = 7.2 and [O2] = 240 µM). The Cu(II)-containing Aβ(1–42) aggregates were either produced with Cu(II) initially present in the Aβ(1–42) solution (bars labeled as “Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II), 48 h” and “Aβ(1–42)-Cu(II), 72 h” or with Cu(II) added into Aβ(1–42) solutions that had been preincubated for 48 h (bar labeled as “Aβ(1–42) (48 h) + Cu(II)”) or 72 h (bar labeled as “Aβ(1–42) (72 h) + Cu(II)”). The incubation temperature was 37 °C. Measurements were repeated at least three times for each solution, and the RSD values, ranging between 2.7 and 19.2%, are represented by the error bars.

Figure 7.

The morphologies of aggregates formed by incubating 200 µM Aβ in the presence and absence of 10 µM Cu(II) at 37°C for 48 h. Images A and C were taken right after the solution and surface preparations whereas images B and D were recorded at 48 h after the sample incubation. The area of each image is 5 µm × 5 µm. The particle marked by the blue bar shown in image B is higher in height than the fibril marked in image D (cf. the cross-sectional contours at the bottoms of the respective images).

Discussion

As mentioned above, at least two mechanisms have been proposed for the oxidation of AA by molecular oxygen that is facilitated by Cu(II) complexed with different molecules.12,38–40 The formation of a ternary complex of O2-Cu(II) complex-AA is one mechanism wherein Cu(II) is complexed with a ligand such as histidine. Since AA can readily reduce Aβ-Cu(II) to Aβ-Cu(I) (cf. Figure 5) and the linear dependence of reaction rate on oxygen concentration is not characteristic of such a mechanism, we propose the following mechanism:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

where AA-−• and DA represent the ascobyl radical and dehydroascorbate, respectively. The overall reaction is determined by the turn-over rate of the Aβ-Cu(I), viz., reactions (7) and (8).

The rate of AA oxidation equals the rate of oxygen consumption once a steady state is established:

| (11) |

When the reaction reaches a steady state, [Aβ-Cu(I)] becomes constant, i.e.,

| (12) |

Based on the mass balance, we have

| (13) |

where [Cu]0 stands for the initial (formal) Cu(II) concentration.

Rearranging eq. 12 gives:

| (14) |

At low [AA], little [Aβ-Cu(II)] is converted to [Aβ-Cu(I)] and therefore [Aβ-Cu(II)] approaches [Cu]0. Consequently from eq. 12, the reaction rate is approximately equal to k1[AA][Cu]0, and is independent of [O2]. The rate constant k1 for reaction (7) was deduced to be 117.2 ± 15.4 M−1s−1 from the linear portion of curve in Figure 1. At high [AA], all of the [Aβ-Cu(II)] has been converted to [Aβ-Cu(I)] which can be approximated to [Cu]0, and the rate of reaction equals k2[Cu]0[O2]. The rate constant k2 was therefore estimated to be 15.8 ± 2.8 M−1s−1 from Figure 2. The rate constant indeed shows that the turn-over of Aβ-Cu(I) is the limiting step, and k2 is about 7.4 times slower than k1. However, the comparability in kinetics of the two steps leads to the plateau in the rate–[AA] relationship, reflecting the transition from the kinetics governed by step 1 to that controlled by step 2. The proposed mechanism explains all of the kinetic data extremely well. We should note that the rate of oxidation of ascorbate catalyzed by ascorbic acid oxidase was measured to be 1.7 × 104 M−1s−1 previously.49 Thus, compared to that catalyzed by the enzyme molecule of ascorbic acid oxidase, the reaction rate of AA oxidation by O2 that is facilitated by Aβ-Cu(II) is moderately high.

Our study demonstrates that the catalytic activity of Cu(II) towards the reduction of O2 is diminished upon its binding to Aβ and is further decreased once Cu(II) is incorporated in Aβ aggregates. That complexation of Cu(II) attenuates the ROS production is consistent with findings from previous studies.14 Recently, Fischer and coworker reported that free hydroxyl radicals are produced when Cu(I) is directly complexed with Aβ(1–28)38 and Aβ(1–40)12 (instead of being created by the Aβ-Cu(II) reduction). They also showed that Aβ(1–40) is more efficient than Aβ(1–28) in scavenging hydroxyl radicals through the oxidation of histidine residues that are bound to Cu(I). Guilloreau et al. studied the reaction between O2 and Aβ-Cu(II) complexes in the presence of AA and found that hydroxyl radicals were produced but the amounts are less than the counterpart without Cu(II) complexation.14 Murray et al. found that oxidative damage of lipid membranes is promoted by the Aβ-Cu(II) complexes and AA, possibly through the hydroxyl radical generation.50 We noticed that in these studies the Aβ and Cu(II) or Cu(I) concentrations were typically at micromolar to sub-micromolar levels and maintained close to 1:1 stoichiometric ratio. As aforementioned, studies by us26 and others10,29,31 have suggested that the binding affinity constant between Aβ and Cu(II) is between submicromolar to nanomolar. In fact, the mass spectra we collected using 1:1 stoichiometric ratio between Aβ and Cu(II) (both at micromolar concentrations) always showed the co-existence of free Aβ and Aβ-Cu(II).16 The observation of the free Aβ peaks suggests that some Cu(II) ions have remained free in the solution. Therefore, when Aβ is not in substantial excess to Cu(II), the free Cu(II) in solution could continuously react with H2O2 produced by Reactions (1)–(2) to generate OH• via the Harber–Weiss reaction. In the case wherein Cu(I) is directly complexed by Aβ, the excess Cu(I) remaining free in solution could further react with H2O2 through the Fenton-like reaction to afford OH•. Therefore, these different results in the literature do not contradict our finding.

From our work it is also evident that the Cu(II) center in Aβ aggregates is still accessible by AA and O2. This is not entirely surprising since several reports have shown that the hydrophilic segment of Aβ, which is also the metal binding domain, populates the exterior of the aggregates.51–53 A study recently performed by Karr and Szalai has clearly demonstrated that aggregation of Aβ does not affect its binding towards Cu(II).25 As for the decreased rate in O2 reduction after the formation of higher-ordered Aβ aggregates, we presume that the compact packing of the Aβ aggregates must have created a Cu(II) coordination environment that is different from the unstructured Aβ monomer. A more compact structure should render greater steric hindrance to the access of O2 and other solution species to the Cu(II) center. Thus, it is conceivable that the activity of the Cu(II) center will decrease as the aggregates become larger in size or higher in the packing order (e.g., monomer → oligomers → protofibrils → fibrils48). Nonetheless the reaction kinetics is still at least an order of magnitude higher than that of the autooxidation rate of AA (< 1 × 10−10 M s−1 in the absence of redox metal ions40).

Our finding has a significant biological relevance and may offer some insight into the role of Aβ in the AD etiology. Aβ appears to inhibit the production of the highly reactive hydroxyl radical from the O2 reduction by complexing Cu(II) and producing H2O2(a less reactive ROS). In this regard, our results argue for the protective role of Aβ. However, the in vivo situation is more complicated. First, in healthy brain there is little free cellular Cu(II)54 and Aβ concentration is also very low (nM or less)55. Several papers have suggested that only at low concentrations does Aβ become effective in alleviating oxidative stress.12,50,56 However, if the binding affinity between Aβ and Cu(II) were indeed at the sub-micromolar to nanomolar level,10,26,29,31 high concentrations of Cu(II) resulted from impaired metal homeostasis would not be adequately complexed by the low level of Aβ. Second, it has been proposed by Viles and coworkers that the elevated Aβ concentration in AD-afflicted brain might be a result of such a homeostasis.56 The high propensity of Aβ to aggregate (especially at a high concentration) and precipitate will further facilitate the accumulation of Cu(II) near the cell membrane. The subsequent ROS generation in the proximity of the cell membrane will cause more severe membrane damages and a faster neuronal cell death. Based on such a model, perhaps a rather important and relevant finding of our work is that Cu(II) complexed by Aβ aggregates still possesses considerable activity of facilitating the H2O2 generation. The co-existence of copper and Aβ aggregates in senile plaques in AD brain and the availability of large amounts of AA further highlight the relevance of such H2O2 generation, as the presence of Cu(II)-containing Aβ aggregates would serve as a “catalyst” to continuously produce large quantities of H2O2. Since the rate constant is moderately high (only two orders of magnitude smaller than ascorbic acid oxidase49), both the continuous consumption of AA or other biological redox species and the incessant production of H2O2 will wreaks havoc to neuronal cells. It has also been suggested that Aβ may accumulate onto cell membrane prior to its oligomerization and aggregation.57,58 Thus Cu(II) sequestration by monomeric and oligomeric Aβ likely occurs in the early stage of AD development and continue on to the later stage wherein Aβ molecules have significantly aggregated. Finally, we should also point out that Aβ-Fe(III), with its metal center capable of cycling between Fe(III) and Fe(II),22 may behave in an analogous fashion as Aβ-Cu(II) to inflict oxidative stress and damage.

Conclusion

The mechanism of ascorbic acid (AA) oxidation by molecular oxygen facilitated by Aβ-Cu(II) complexes has been elucidated. The AA oxidation rate was found to be linearly dependent on the concentrations of Aβ-Cu(II) and dissolved oxygen, reaching a steady state at high [AA] (>100 µM for [O2] = 240 µM). Voltammetric measurements indicate that Aβ-Cu(II) rapidly oxidizes AA. Based on these kinetic behaviors, we proposed a mechanism in which Aβ-Cu(II) behaves as a “catalyst” to facilitate the reduction of O2 by AA and the production of H2O2 as the final product. The incessant production of H2O2 by a small amount of Aβ-Cu(II) complex will eventually deplete O2, AA and/or other important redox species in highly localized regions, disrupting the cellular redox balance and expediting cell loss. The relatively high rate constant measured in this work substantiates such a possibility. These kinetic behaviors are different from those reported for the reaction between AA and O2 that is catalyzed by the His-Cu(II) complex. When His-Cu(II) serves as the catalyst, the Cu(II) center is not directly reduced, instead a ternary complex among His-Cu(II), O2, and AA is formed. Furthermore, in comparison with free Cu(II), Cu(II) bound by Aβ is less efficient in facilitating the O2 reduction (or AA oxidation). When Cu(II) is complexed by Aβ aggregates, O2 is still reduced, albeit at a slower rate. Based on the reaction stoichiometry, if [Aβ] is much greater than [Cu(II)], hydroxyl radicals are not produced. Overall, the rate of the O2 reduction to H2O2 follows the order of free Cu(II) > Cu(II) bound by Aβ oligomers/fibrils > Cu(II) bound by Aβ fibrils. It is also evident that the coordination environment of and the accessibility to the Cu(II) center alter the reaction pathways and modulate the catalytic activity of the Cu(II) center. Our work demonstrates that oxidative stress can be resulted from the interaction between redox metal ions and aggregates derived from Aβ

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by an NIH grant (Grant No: SC1NS070155) and the NIH-RIMI Program at California State University-Los Angeles (P20 MD001824-01). XL thanks the financial support from the State Key Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology (No. KF2008-06) and the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. LL also thanks the China Scholarship funds for financial support.

References

- 1.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ. Science. 1997;275:630–631. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varadarajan S, Yatin S, Aksenova M, Butterfield DA. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:184–208. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush AI., Trends Neurosci. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu G, Huang W, Moir RD, Vanderburg CR, Lai B, Peng Z, Tanzi RE, Rogers JT, Huang X. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;155:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Mardesbery WR. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakob-Roetne R, Jacobsen H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3030–3059. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karr JW, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13534–13538. doi: 10.1021/ja0488028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shearer J, Szalai VA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17826–17835. doi: 10.1021/ja805940m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syme CD, Nadal RC, Rigby SEJ, Viles JH. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18169–18177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong J, Atwood CS, Anderson VE, Siedlak SL, Smith MA, Perry G, Carey PR. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2768–2773. doi: 10.1021/bi0272151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baruch-Suchodolsky R, Fischer B. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4354–4370. doi: 10.1021/bi802361k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faller P, Hureau C. Dalton Trans. 2009:1080–1094. doi: 10.1039/b813398k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilloreau L, Combalbert S, Sournia-Saquet A, Mazarguil H, Faller P. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang X, Cuajungco MP, Atwood CS, Hartshorn MA, Tyntall JDA, Hanson GR, Stokes KC, Leopold M, Multhaup G, Goldstein LE, Scarpa RC, Saunders AJ, Lim J, Moir RD, Glabe C, Bowden EF, Masters CL, Fairlie DP, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37111–37116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang D, Men L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Chickenyen S, Wang Y, Zhou F. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9270–9282. doi: 10.1021/bi700508n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rottkamp CA, Raina AK, Zhu X, Bush AI, Atwood CS, Chevion M, Perry G, Smith MA. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2001;30:447–450. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayre LM, Perry G, Harris PLR, Liu Y, Schubert KA, Smith MA. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:270–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MA, Harris PLR, Sayre LM, Perry G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:9866–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RKO. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang X, Atwood CS, Hartshorn MA, Multhaup G, Goldstein LE, Scarpa RC, Cuajungco MP, Gray DN, Lim J, Moir RD, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7609–7614. doi: 10.1021/bi990438f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang D, Li X, Williams R, Patel S, Men L, Wang Y, Zhou F. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7939–7947. doi: 10.1021/bi900907a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drew SC, Noble CJ, Masters CL, Hanson GR, Barnham KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1195–1207. doi: 10.1021/ja808073b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karr JW, Akintoye H, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5478–5487. doi: 10.1021/bi047611e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karr JW, Szalai VA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5006–5016. doi: 10.1021/bi702423h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maiti NC, Jiang D, Wain AJ, Patel S, Dinh KL, Zhou F. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:8406–8411. doi: 10.1021/jp802038p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atwood CS, Scarpa RC, Huang X, Moir RD, Jones WD, Fairlie DP, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:1219–1233. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatcher LQ, Hong L, Bush WD, Carducci T, Simon JD. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:8160–8164. doi: 10.1021/jp710806s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Q-F, Hu J, Wu W-H, Liu H-D, Du J-T, Fu Y, Wu Y-W, Lei P, Zhao Y-F, Li Y-M. Biopolymers. 2006;83:20–31. doi: 10.1002/bip.20523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarell CJ, Syme CD, Rigby SEJ, Viles JH. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4388–4402. doi: 10.1021/bi900254n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tougu V, Karafin A, Palumaa P. J. Neurochem. 2008;104:1249–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hewitt N, Rauk A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:1202–1209. doi: 10.1021/jp807327a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dryhurst G, Kadish KM, Scheller F, Renneberg R. Biological Electrochemistry. New York, London: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34.da Silva GFZ, Tay WM, Ming L-J. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:16601–16609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Silva GFZ, Ming L-J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5501–5504. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice ME. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barabfis JB, Nagy E, Degrell I. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat. 1995;21:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(95)00654-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baruch-Suchodolsky R, Fischer B. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7796–7806. doi: 10.1021/bi800114g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shtamm EV, Purmal AP, Skurlatov YI. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1979;XI:461–494. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scarpa M, Vianello F, Signor L, Zennaro L, Rigo A. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:5201–5206. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barron ESG, DeMeio RH, Klemperer F. J. Biol. Chem. 1936;112:625–640. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skurlatov YI, Kovner VY, Travin SO, Kirsh YE, Purmal AP, Kabanov VA. Eur. Polym. J. 1979;15:811–815. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorbunova NV, Purmal AP, Skurlatov YI, Travin SO. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1977:983–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Pozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CC, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pecci L, Montefoschi G, Cavallini D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:264–267. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barb WG, Baxendale JH, George P, Hargrave KR. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1951;47:462–500. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morgan C, Colombres M, Nuñez MT, Inestrosa NC. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004;74:323–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kroneck PMH, Armstrong FA, Merkle H, Marchesini A. Advances in Chemistry, Ascorbic Acid:Chemistry, Metabolism, and Uses. American Chemical Society: Washington, D. C.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murray IVJ, Sindoni ME, Axelsen PH. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12606–12613. doi: 10.1021/bi050926p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luhrs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Dobeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paul C, Axelsen PH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5754–5755. doi: 10.1021/ja042569w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kheterpal I, Williams A, Murphy C, Bledsoe B, Wetzel R. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11757–11767. doi: 10.1021/bi010805z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O'Halloran TV. Science. 1999 284;:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, Lee M, Dovey H, Davis D, Sinha S, Schlossmacher M, Whaley J, Swindlehurst C, McCormack R, Wolfert R, Selkoe DJ, Lieberburg I, Schenk D. Nature. 1992;359:325–327. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nadal RC, Rigby SEJ, Viles JH. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11653–11664. doi: 10.1021/bi8011093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang D, Dinh KL, Ruthenburg TC, Zhang Y, Su L, Land DP, Zhou F. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:3160–3168. doi: 10.1021/jp8085792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terzi E, Hölzemann G, Seelig J. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14845–14852. doi: 10.1021/bi971843e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]