SUMMARY

Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) undergoes acute primary infection in epithelial cells followed by establishment of latency in the neurons of trigeminal ganglia. The latent virus maintains a life-long dormant state and can reactivate spontaneously in a small fraction of host cells, suggesting transcriptional silencing occurs in neurons. Computer data mining analyses identified a thyroid hormone response element (TRE), the binding site for the thyroid hormone receptor (TR), in the promoter of HSV-1 thymidine kinase (TK). TRs are transcription factors whose activity is dependent on their ligand thyroid hormone (TH or T3). We hypothesize that TR and T3 exert regulation on HSV-1 gene expression in neurons. A neuroblastoma cell line expressing the TR isoform β (N2aTRβ) was utilized for initial in vitro investigation. Liganded TR repressed TK promoter activity but unliganded TR relieved the inhibition. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays showed that TRs were recruited to TK TRE regardless of the status of T3; hyperacetylated histone H3 at lysine 9 was associated with transcriptionally active promoters. In addition, ChIP results indicated that a repressive mono-methylated H3 modified at lysine 9 was enriched in TK promoter in the presence of TR and T3. T3-treated N2aTRβ cells were suppressive to TK expression and release of infectious viruses at low moi. RT-PCR and plaque assays showed that the TK can be de-repressed and the virus release was increased when the T3 was removed. These results suggest that T3 could regulate HSV-1 gene expression through its receptor via histone modification in cultured neuronal cells.

INTRODUCTION

HSV-1 primary infection initiates when the virus invades epithelia and starts active gene expression and replication to produce progeny. The virus may subsequently establish life-long latency in the sensory neurons of trigeminal ganglia (TG). The reactivation may occur spontaneously. The recurrent infections can attack the anterior buccal mucosa, lips, or perioral area of the face and eyes (Fatahzadeh & Schwartz, 2007). The gene expression in the lytic phase follows a cascade and is characterized by a sequential order. However, viral gene expression during latency differs completely from what is observed in acute infection and significant levels of transcription are detected from only one region of the viral genome, the latency-associated transcripts (LAT) (Javier et al., 1988; Jones, 2003; Bloom, 2004). In addition, the profile of viral gene expression during reactivation is likely to be different from that observed in primary infection, in which the cascade is disrupted. For example, thymidine kinase (TK), a β gene, could be expressed concurrently or before the expression of α genes (Kosz-Vnenchak et al., 1993; Tal-Singer et al., 1995; Nichol et al., 1996).

A variety of mechanisms have been proposed to describe the establishment of viral latency and reactivation, such as altered immune response (Bystricka & Russ, 2005; Koelle & Corey, 2008), LAT-mediated anti-apoptosis (Perng et al., 2000; Bloom, 2004; Peng et al., 2004; Branco & Fraser, 2005; Carpenter et al., 2007), microRNAs-induced gene silencing (Cui et al., 2006; Umbach et al., 2008) differential neuronal suppression (Block et al,. 1994; Su et al., 2000; Moxley et al., 2002; Su et al., 2002), hormonal regulation (Garza & Hill, 1997; Hardwicke & Schaffer, 1997; Noisakran et al., 1998; Marquart et al., 2003), and repressive chromatin (Kubat et al., 2004; Kubat et al., 2004; Amelio et al., 2006; Bedadala et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2007; Pinnoji et al., 2007; Knipe & Cliffe, 2008). In an effort to discover new transcription factor binding sites, our sequence analysis revealed two thyroid hormone responsive elements (TREs) located in the promoter regions of TK, suggesting that thyroid hormone (TH) could have a role in HSV-1 TK regulation and could control viral latency and reactivation.

The thyroid gland produces two hormone products, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), from thyroglobulin protein (Deme et al., 1976). Although triiodothyronine (T3) is produced less, it is more potent and responsible for the majority of biological effects. TH exerts its action via its nuclear receptors (TRs). They are transcription factors belonging to the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors (Tsai & O'Malley, 1994). It has been shown that both liganded and unliganded TRs are involved in gene regulation.

The present studies target the interrelationship of T3, TRs, and chromatin structure during HSV-1 gene regulation in neuronal cells. The gene regulation of TK was analyzed in neuroblastoma cells N2a and N2aTRβ (N2a cell constitutively expressing TRβ). The effect of TR and T3 on histone modification and cofactor recruitment to the TK promoter was analyzed. Our results indicated that TR can control the TK promoter activity and this regulatory effect is determined by its ligand via distinct histone modifications and chromatin remodeling. This is the first in vitro evidence that TR exerted epigenetic regulation on HSV-1 gene expression in neuronal cells and could play a role in the complex processes of establishing latency and reactivation of HSV-1.

METHODS

Viruses, cell lines, and culture conditions

The N2a cell, a mouse neuroblastoma cell line, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-treated fetal bovine serum (FBS). N2aTRβ cell was a gift from Dr. Robert Denver (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) and was grown under the same conditions. CV-1 cells were cultured in 10% FBS supplemented with DMEM. All cells were maintained in an incubator at 37 ° C with 5% CO2. The titers of HSV-1 strains 17Syn+, 17Syn+-EGFP (Foster et al., 1998), and McKrae were determined on CV1 cells. T3 was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Plasmids

The pRL-TK vector was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI; Cat#: TB240). It contains 722 bp of the HSV-1 TK promoter (Fig. 1). Monster Green® Fluorescent Protein phMGFP Vector (Promega, Cat#: E6421) was used as a transfection efficiency control. Plasmid pICP4-SEAP contains reporter SEAP driven by ICP4 promoter (Pinnoji et al,. 2007) and was used for normalization in Fig. 2.

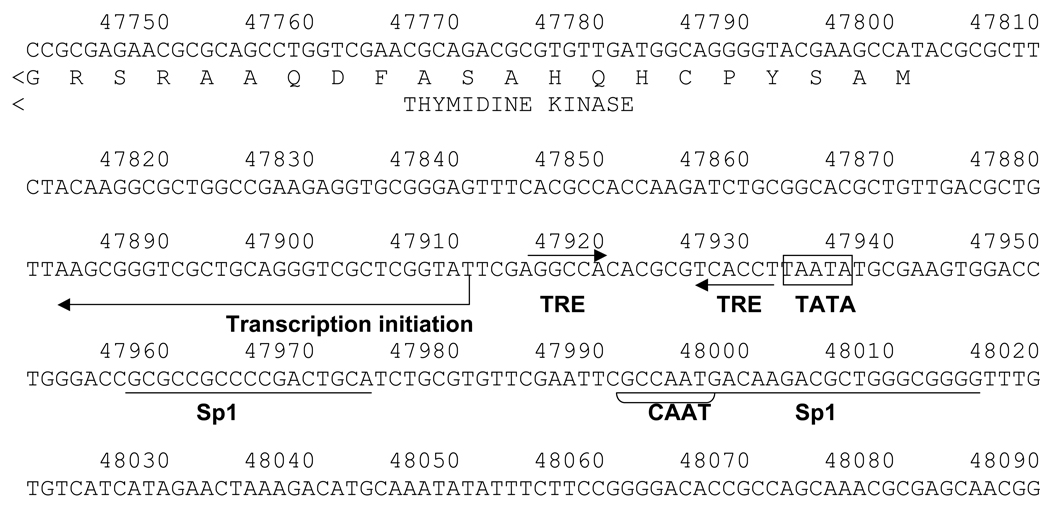

Fig. 1. HSV-1 TREs.

1A: Negative TREs were identified in the HSV-1 TK promoter. The TREs were organized as inverted repeats with six nucleotides spacing (IR6) and located immediately after the TATA box. Transcription initiation site, Sp1 elements and CAAT box were shown.

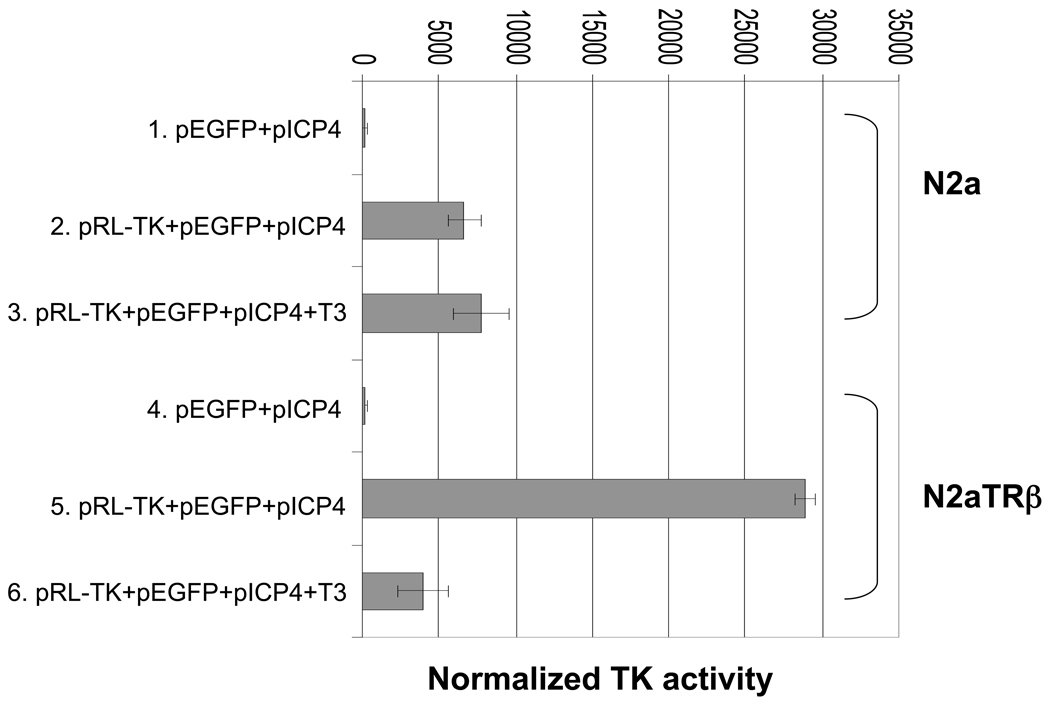

Fig. 2. HSV-1 TK transcription was negatively regulated by TR and T3.

N2a and N2aTRβ cells were cotransfected with various plasmids by Nucleofector II with duplication to analyze the regulatory effects of TR and T3 on TK promoter. Plasmid pEGFP was used as a reference to monitor the transfection efficiency. Plasmid pICP4 was used as normalization control. Fluorescent microscopy was performed using Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope. Cells were subjected to luciferase assay using Promega Luciferase Assay Kit at 48-hrs post-transfection. The signal was measured by luminometer. The results were normalized by SEAP assay driven by ICP4 promoter. Error bars represent the mean plus or minus the standard deviation.

Transfection

Nucleofector II from Amaxa (Cat#: AAD-1001S, Gaithersburg, MD) was used for high efficiency of transfection essentially described by the manufacturer. The experiments were performed using Kit V (Amaxa, Cat#: VCA-1003) and the protocol number was T-024.

Antibodies

The antibodies used for immunoblot analyses and ChIP are listed in Table 1. The dilution was based on the manufacturer’s suggestions.

Table 1.

The sources of antibodies

| Antigen | Species | Clonality | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRβ1 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | Upstate (Lake Placid, NY, Cat#: 06-539) |

| Mono-methyl-histoneH3 (Lys9) | Rabbit | Polyclonal | Upstate (Cat#: 07-395) |

| Anti acetyl-histone H4 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | Upstate (Cat#: 06-866) |

| Anti-α-tubulin | Mouse | Monoclonal | Calbiochem ( Cat#: CP06) |

| Secondary Ab for Western | Rabbit | Perkin Elmer Lifesciences ( Cat#: NEF812) | |

| Secondary Ab for Western | Mouse | Perkin Elmer Lifesciences ( Cat#: NEF822) |

Reporter assays

The cells were harvested for the luciferase assay after 48 hr of transfection essentially described by the manufacturer. Luciferase activity was measured by a luminometer using the Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Luminescence was measured over a 10-sec interval with a 2-sec delay on the 20/20n Luminometer (Turner Biosystem, Sunnyvale, CA). The results were presented as the fold induction of the reporter plasmid in the presence or absence of T3 (100 nM). The SEAP assay was described previously (Bedadala et al., 2007).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RT-PCRs were performed using Superscript One-Step RT-PCR (Invitrogen) with 0.5 µg of total RNA and primer set. Their sequences are as follows: Actin: 5'-ATT CCT ATG TGG GCG ACG AG-3' and 5'-TGG ATA GCA ACG TAC ATG GC-3'; TK: 5'-ATG GCT TCG TAC CCC TGC CAT -3' and 5'-GGT ATC GCG CGG CCG GGT A -3'; EGFP: 5’- GCA GAA GAA CGG CAT CAA GGT G-3’ and 5’- TGG GTG CTC AGG TAG TGG TTG TC-3’.The RT-PCR reaction was carried out at 45 °C for 20 min followed by 25 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 57 °C for 30 sec, and 68 °C for 30 sec. The RT-PCR products were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The Kodak Gel-Logic 100 imaging system was used for documentation.

Immunoblot analysis

The protocol was described previously (Pinnoji et al., 2007). Anti-TRβ1 rabbit polyclonal antibody was used at a dilution of 1:1000 and the secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate) at a dilution of 1:2000 in PBST for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-α-tubulin mouse antibody was added at a dilution of 1:10 000 and the secondary antibody (goat anti mouse IgG – horseradish peroxidase conjugate) was included at a dilution of 1:5000 in PBST for 1 h at room temperature.

ChIP

The protocol was described previously (Pinnoji et al., 2007). PCR primers were: TK 5'-ATG GCT TCG TAC CCC TGC CAT-3’ and 5’- GGT ATC GCG CGG CCG GGT A -3’

T3 removal experiments

N2aTRβ cells were plated on a 6-well plate with 40–50% confluency with the addition of T3 (100 nM). Media were replaced daily with fresh T3. On day 6, viral inoculation was performed for 1 h at moi of 1. The inoculum was then removed and the cells were washed twice with 1 ml of PBS followed by the addition of 1 ml of fresh media containing T3 for 8 h. The T3 incubation was stopped after 8 h by removing the medium completely and washing the cells twice with PBS. New medium was added in each well with or without T3. The media were collected 48 h postinfection (hpi) and subjected to plaque assays.

Plaque assays

Media collected from mock and infected N2aTRβ cells at 48 hpi were subjected to plaque assays by infecting CV-1 cells. Monolayers of CV-1 with 90–100% confluency in 24-well plates were incubated with 200 µl of media for 45 min on a rocking platform at different dilutions followed by addition of 1 ml fresh media to each well for 48 h. At the end of the incubation, the infected cells were washed with PBS and treated with crystal violet (PML Microbiologicals, Wilsonville, OR) for 20 min followed by washing with water. Plaques were counted in each well and the probability was measured by a Student’s paired t-Test with a two-tailed distribution using Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

Identification of HSV-1 TK TREs

We identified TREs in the HSV-1 genome located from 47915 to 47932 (5’- tatta AGGTCAcgcgtgTGGCCT-3’, Fig. 1) based on the HSV-1 complete genome sequence (Accession #: X14112). The sequence is represented as inverted repeats with six-nucleotide spacing (IR6). These IR6 TREs are located between the TATA box (47933–47937) and the transcription initiation site (47911). The TREs in this context were suggested to function as negative TREs in neural cells (Park et al., 1993).

HSV-1 TK promoter was repressed by TR in the presence of T3

To determine the regulatory effect of TR on HSV-1 TK promoter, N2a and N2aTRβ cells were cotransfected with pRL-TK as well as pEGFP and pICP4-SEAP in the absence or presence of T3. Fluorescent microscopy showed that the transfection efficiency was similar between N2a and N2aTRβ cells (data not shown). The Luc assays (normalized by SEAP assay) showed that TK promoter activity exhibited a 7-fold decrease by T3 in N2aTRβ cells but exhibited no significant difference in N2a cells (Fig. 2). In addition, the TK promoter activity was four-fold stronger in N2aTRβ without T3 than in N2a cells (Fig. 2, compare lane 2, 3, and 5). Control experiments for normalization purposes using reporter plasmids containing CMV, HSV-1 ICP4, and ICP22 promoters showed no regulatory effect by T3 and TR (data not shown). These results suggested that HSV-1 TK TREs exert down-regulation on the promoter by TR and T3. Unliganded TR, in contrast, enhanced TK promoter activity.

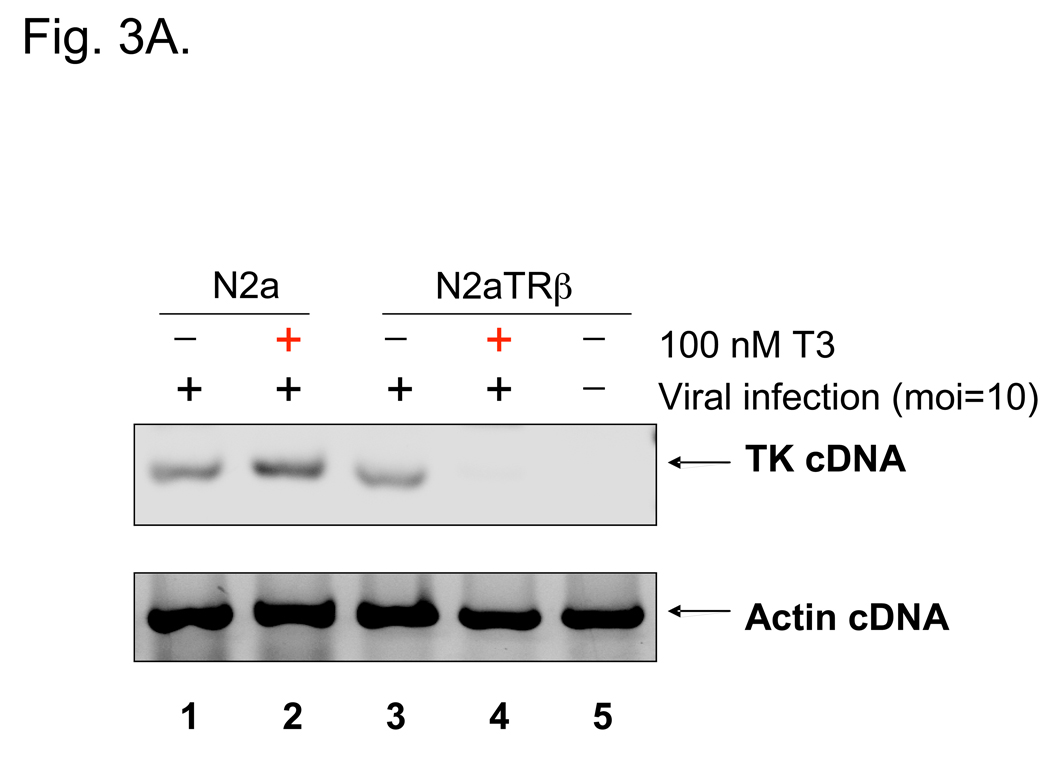

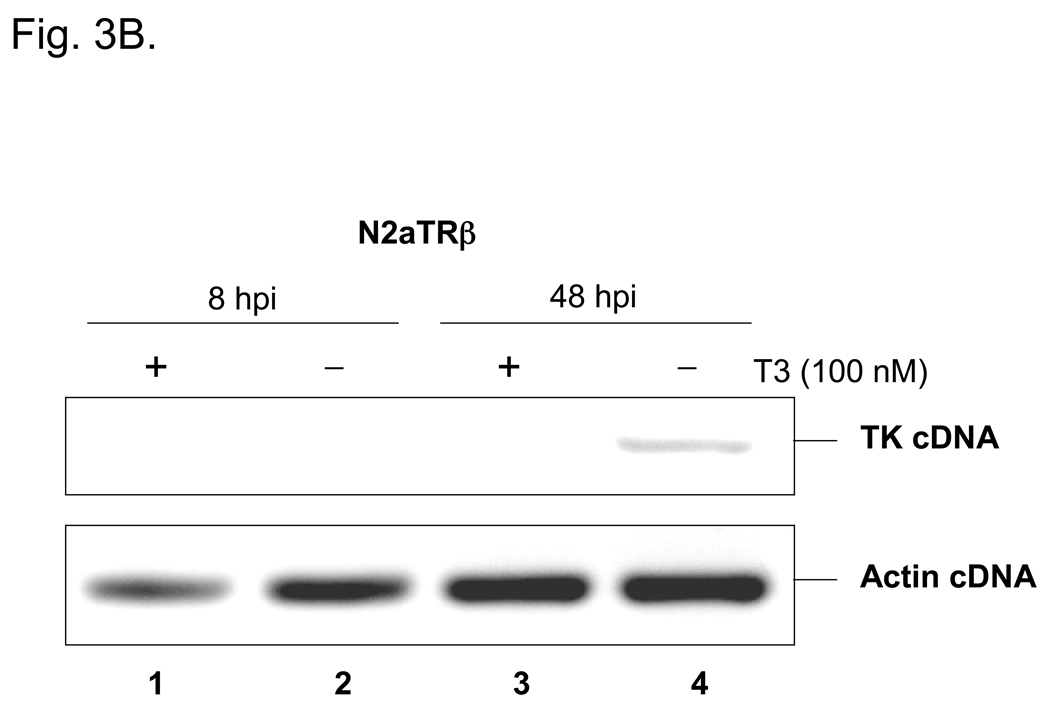

Viral infections were done to investigate TR-mediated regulation. N2a and N2aTRβ cells were infected with strain 17Syn+ at moi=10 with or without T3. RT-PCR assays revealed no regulatory effect (data not shown), probably due to the α transactivation of TK. To eliminate the effect of transactivation, cycloheximide (CHX) was added to inhibit t he synthesis of α proteins and therefore allowed the assessment in the absence of transactivation. Under this condition, TK transcription was inhibited by liganded TR at 8 hpi (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3 and 4). At moi lower than 1, TK promoter activity was found to be down-regulated by liganded TR at 48 hpi without the effect of CHX (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results demonstrated that HSV-1 TK was negatively regulated by liganded TR in the neuronal cells.

Fig. 3. HSV-1 TK was repressed by liganded TR during infections.

3A: N2a and N2aTRβ cells were infected with wild-type virus 17Syn+ at moi=10 “in the absence or presence of T3 with 50 µg/ml cycloheximide to block the protein synthesis of HSV-1 α genes. The total RNA was purified and subjected to RT-PCR by primers against TK. Actin primers were used as controls.

3B: N2aTRβ cells were infected with wild-type virus 17Syn+ at moi=1. The total RNA was purified at 8 hpi and 48 hpi then subjected to RT-PCR using primers against TK and actin. The gel showed that TK transcription was delayed until 48 hpi and was repressed by the addition of T3 (compare lanes 3 and 4).

TRβ was recruited to the TK promoter and the repressive histones were enriched at the TK promoter by liganded TR

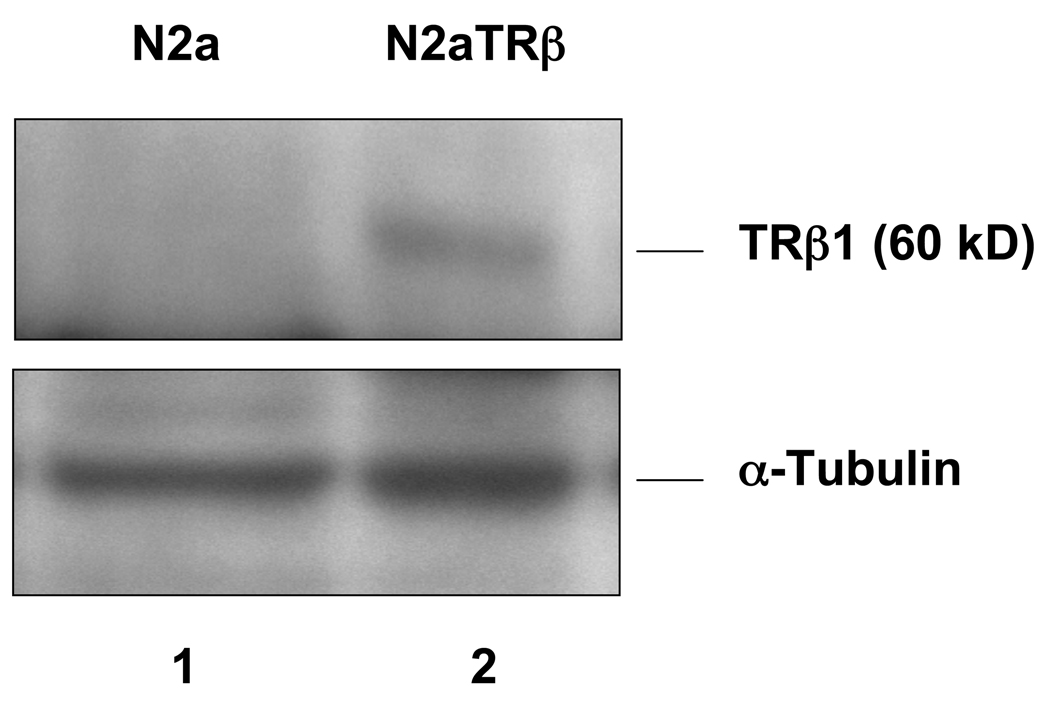

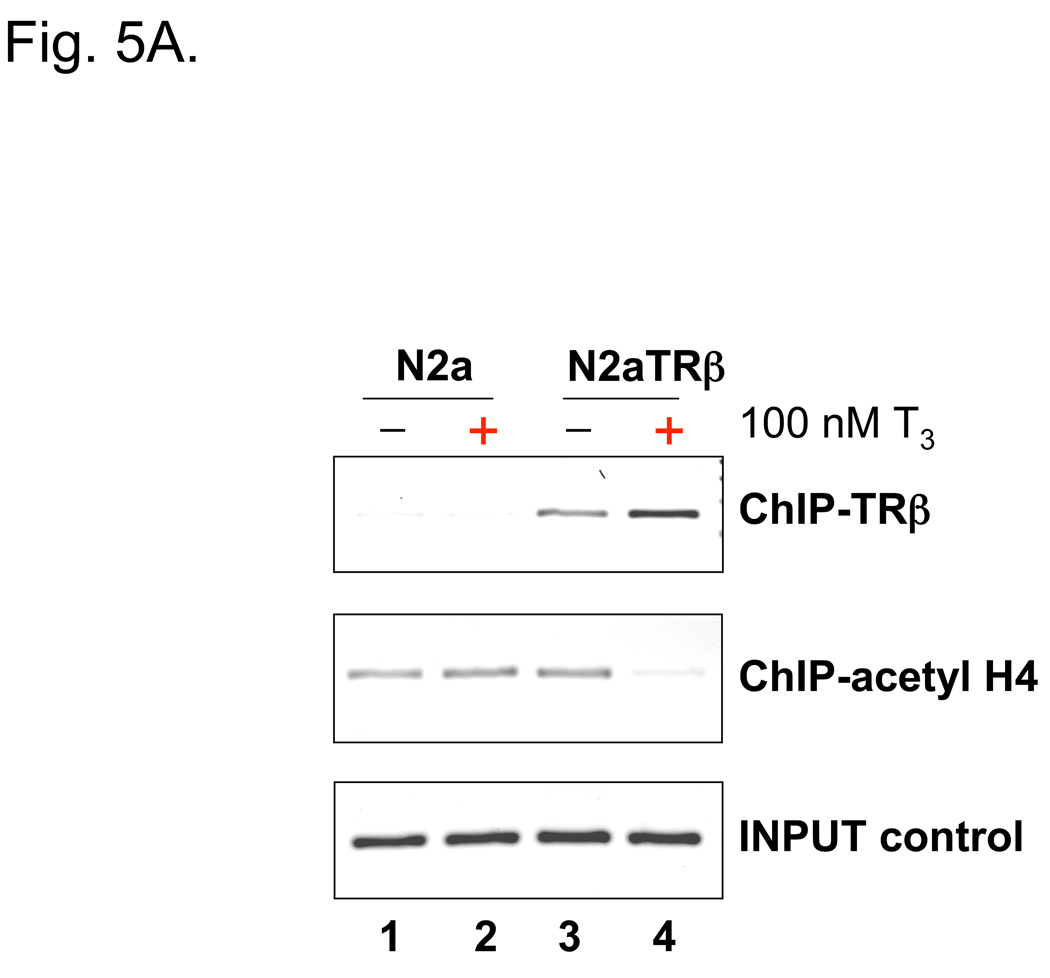

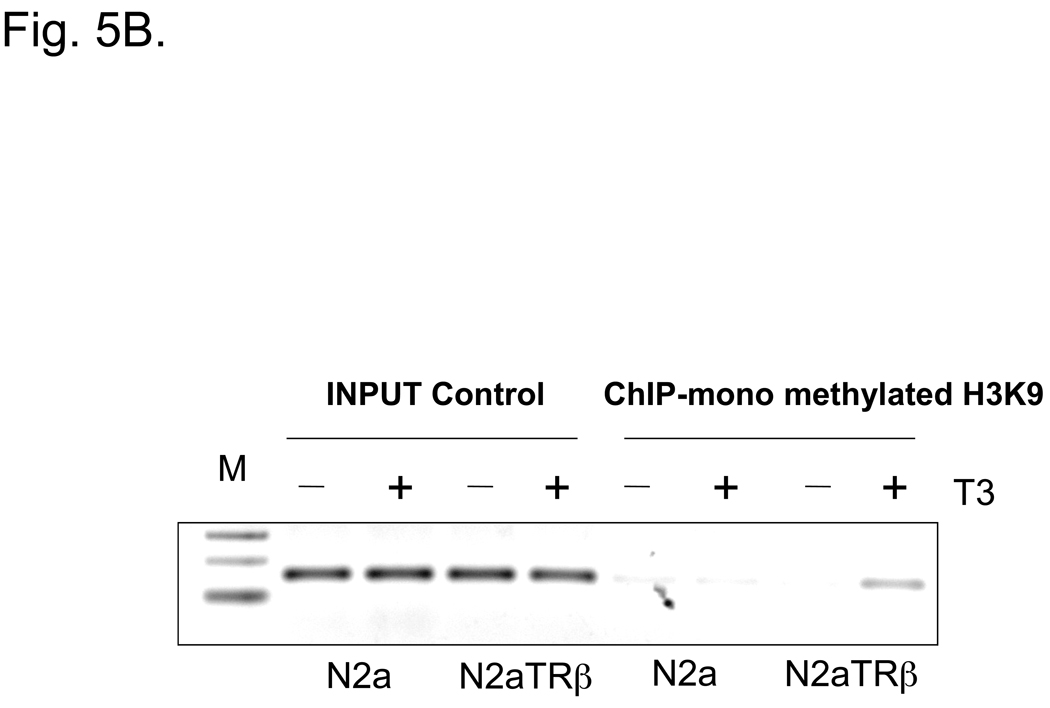

N2aTRβ cells were constructed to express TRβ and the overexpression was verified by Northern blot analysis; the T3 treatment induced N2aTRβ cells to differentiate (Lebel et al., 1994). To confirm the protein expression and assess its function, extracts from N2a and N2aTRβ cells were subjected to Western blot analyses using anti-TRβ and anti-α-tubulin Ab. The results supported the Northern blot analysis that TRβ is overexpressed in N2aTRβ but not N2a cells (Fig. 4). Previous studies showed that TRβ was bound to TK promoter in vitro (Park et al., 1993). The in vivo interaction was therefore analyzed by ChIP and the results indicated that TRβ was associated with the TK promoter independent of ligand binding (Fig. 5A). The TRβ-mediated histone modification was investigated by ChIP using antibodies against acetyl histone H4 and mono-methylated histone H3K9. The results indicated that histone H4 acetylation was significantly reduced (Fig. 5A; lane 4) but mono-methylation of histone H3K9 was enriched at the TK promoter in the presence of T3 (Fig. 5B; last lane). Altogether, these results demonstrated that TRβ was recruited to TK promoter and regulated the gene expression, at least in part, by differential histone modification.

Fig. 4. TRβ is overexpressed in N2aTRβ cells.

Protein extracts were purified from N2a and N2aTRβ cells and subjected to gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblot analysis using Abs against TRβ1 and α-tubulin.

Fig. 5. TRβ bound to the TK promoter and induced T3-mediated histone modification.

5A: Cells were transfected with pRL-TK and treated as noted. The transfected cells were subjected to ChIP after 48 h of treatment and immunoprecipitated by Abs against TRβ or acetylated histone H4.

5B: ChIP was performed using the conditions of 5A and immunoprecipitated by anti-mono methylated H3K9 Ab.

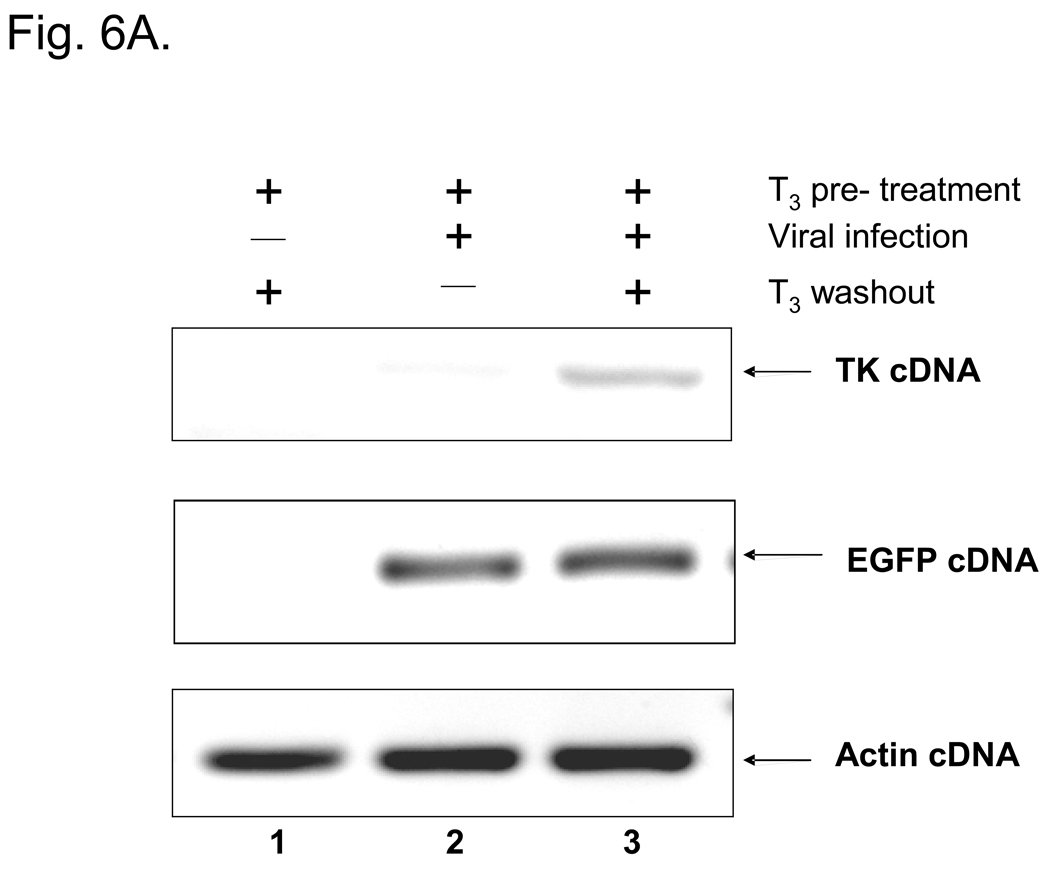

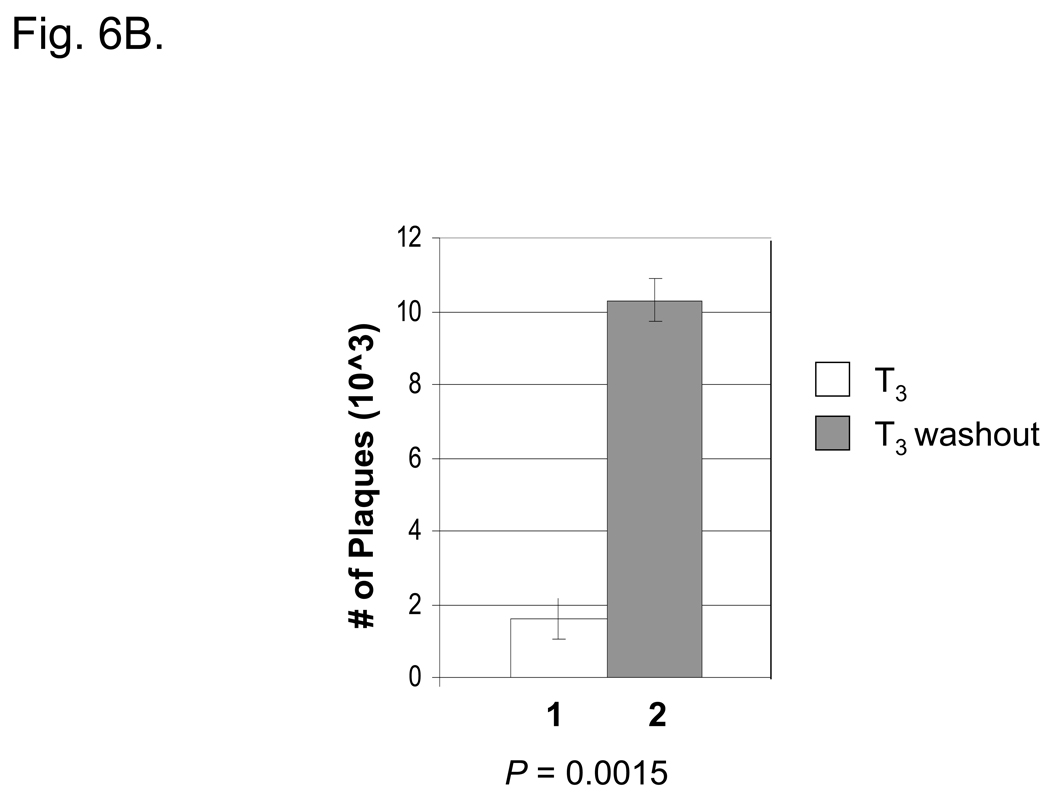

Removal of T3 activated TK expression and induced the virus release

To study the effect of T3 on TR-mediated regulation, N2aTRβ cells were treated for five days before the infection with or without T3 using an HSV-1 expressing EGFP at moi = 1. Fluorescent microscopy revealed that the numbers of green fluorescent cells were similar between cells treated with or without T3, indicating that T3 treatment did not affect the infection efficiency (data not shown). RT-PCR assays showed that the expression of TK was de-repressed upon washout of T3 at 48 hpi (Fig. 6A). The plaque assays indicated that the removal of T3 by washout increased the virus release 6.4-fold more than the cells being treated with T3 (Fig. 6B). The P value measured by a Student’s paired t-test with a two-tailed distribution was 0.0015, indicating a significant increase. Given the fact that N2aTRβ cells were differentiated after T3 incubation, these results suggested that subtraction of hormone reversed the TK repression and the enzyme presumably induced viral replication in resting cells and enhanced the replication and virus release.

Fig. 6. Long-term T3 treatment prevented the TK expression and the washout of T3 induced the TK expression and virus release.

6A: Cells were pre-treated with T3 for five days and subsequently infected with 17Syn+-EGFP viruses at moi of 1. Total RNA was isolated at 48 hpi and subjected to RT-PCR assays using TK primers to study TR-mediated regulation. RT-PCR assays using EGFP primers were performed as internal viral infection control.

6B: The media of infected cells were collected 48 hpi and subjected to plaque assays using CV1 cells to investigate the release of infectious viruses.

DISCUSSION

This study focused on the roles of TR and its ligand T3 in the regulation of HSV-1 TK. Our results demonstrated that the transcription factor TR utilized its ligand to exert a repressive effect on TK in neuronal cells. Unliganded TR interacted with the TK TREs and induced histone H4 hyperacetylation at the TK promoter to promote active transcription. The liganded TR reversed the histone acetylation and recruited repressive mono-methylated H3K9 to the promoter for transcription repression. These results provide evidence suggesting that the novel TR/T3-mediated regulation could have a role in controlling the establishment of latency and reactivation of HSV-1.

TH participates in development and homeostasis in adults (Evans, 1988). Both sensory neurons and peripheral glial cells in dorsal root ganglia have been shown to possess specific T3 binding sites (Walter & Droz, 1995). During development, sensory neurons express TRβ rather than TRα and the amount of TRβ positive neurons increased during the postnatal stages and remained stable in adults. The presence of TR in sensory neurons indicates that the feedback regulation of circulating TH could occur by binding to the receptors (Glauser & Barakat Walter, 1997). T3 can affect different processes involved in the survival, differentiation, and maturation of neurons (Walter, 1996). In a physiological concentration, T3 enhances neurite outgrowth of primary sensory neurons in cultures, possibly in combination with nerve growth factor, to regulate the expression of cytoplasmic dynein, a protein that is involved in retrograde axonal transport (Barakat-Walter & Riederer, 1996). In addition, whole body hyperthermia was reported to reduce the level of serum T3 by 50%, probably due to the suppression of thyroid stimulating hormone release, monodeiodination alteration of T4 from T3 to reverse T4, or enhanced T3 clearance (Shafer et al., 1980). Hyperthermia can be used to trigger HSV-1 reactivation in the mouse latency model (Sawtell & Thompson, 1992). Therefore, T3 is likely to participate in the regulation and maintenance of viral latency and reactivation.

The role of T3 in HSV-1 gene regulation has not been extensively investigated. Park et al reported that the addition of T3 induced the HSV-1 TK promoter by 4- to 5-fold in pituitary rat cells by transient transfection (Park et al., 1993). However, the authors indicated that similar TREs are found in several genes that were characterized to mediate negative regulation in brain. Our transfection a ssays indicated that HSV-1 TK was repressed by liganded TRs in neuroblastoma cells. This result was further supported by the infection experiments showing that TK, a β gene, was inhibited by liganded TR at moi of 1 or high moi without α proteins. The role of TK in brain is clear for HSV-1 infection. TK is required to provide dNTP for viral replication in resting cells such as neurons. Furthermore, viral replication is required for efficient α and β expressions in neurons during reactivation (Nichol et al., 1996). Based on these observations, TK was suggested to initiate α transcription and subsequent replication during reactivation (Tal-Singer et al., 1995). Moreover, Tal-Singer et al. (1997) reported that during in vivo reactivation in TG, TK was one of the first genes to be expressed. Another report showed that a TK-mutant exhibited greatly reduced α and β expression during reactivation (Kosz-Vnenchak et al., 1993). Based on these results, TK was suggested to play a critical role during viral reactivation. However, another report indicated that TK as well as α genes were expressed at the same time (Pesola et al., 2005). Although the role of TK is ambiguous, it is likely that T3 has the potential to control TK expression and control viral transcription. To test the hypothesis, we utilized a unique cell culture model, N2aTRβ. T3 treatment has been shown to induce these cells to differentiate, mimicking the state of neurons in brain (Lebel et al., 1994). Therefore, we treated N2aTRβ cells with T3 for 5 days to induce differentiation and then infected the treated cells with HSV-1. The results supported our hypothesis that removal of T3 by washout de-repressed the TK expression and significantly increased virus release, presumably by producing dNTP and inducing viral replication. We determined that viruses were still released from the T3-treated cells. The release was probably due to the fact that α proteins, transactivated by VP16, induced the expression of TK but the production wa s remarkably reduced by liganded TR. Further infection experiments with appropriate mutations are underway to investigate the T3-mediated regulation of viral replication/transcription using this model.

Our results indicated that TK is negatively regulated by liganded TR. TR-mediated negative regulation was not as clear as the positive regulation. Many hypotheses have been proposed such as the binding to TFIID (Crone et al., 1990), inhibition of SP1 stimulation (Xu et al., 1993), hetero- to homo-dimer conformational change (Bendik & Pfahl, 1995), recruitment of HDAC (Sasaki et al., 1999), recruitment of chromatin insulator protein (Burke et al., 2002), CREB competition (Mendez-Pertuz, et al., 2003), TBP recruitment (Sanchez-Pacheco & Aranda, 2003), repression of S-phase genes (Nygard et al., 2003), Sp1 competition (Villa et al., 2004), interaction of GATA2, and TRAP220 dissociation (Matsushita et al., 2007). We tested these hypotheses and showed that the binding of Sp1, TFIID, CREB, CREB binding protein, and TBP to TK promoter was not involved in this regulation (data not shown). Our results further indicated that hypoacetylated histone H4 and mono-methylated H3K9 were enriched at TK by liganded TR. Mono-methylated H3K9 was shown to associate with the inactive promoter and behaved as repressive chromatin (Vakoc et al., 2005). Besides, our transfection experiments showed that TK promoter activity was activated by TR in N2aTRβ 4 times more strongly than in N2a cells (Fig. 2). This activation was not seen during infection (Fig. 3A). The mechanism is unknown but is probably due to VP16 transactivation and/or the presence of other virion proteins. For example, virion host shutoff protein (VHS) could inhibit or reduce the expression of important cellular transcription factors for transcription re gulation. The underlying mechanisms of TR-mediated TK regulation are being investigated.

The current studies provide evidence that strongly implicates the roles of T3 and TR in the regulation of HSV-1 gene expression in cultured neurons. The current hypothesis is that the liganded TR inhibited viral replication by repressing TK expression. These outcomes led to the maintenance of latency. Nonetheless while the T3 concentrations were low, unliganded TR relieved the repression of TK and promoted the viral replication. The active replication and increased transcription of α genes would lead to the subsequent reactivation. More experiments especially using animal models are necessary to identify key mechanisms involved in the establishment of latency and reactivation of HSV-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This project is supported by NIH/NCRR P20RR016456 and was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants EY006311 (J.M.H.), AG023085 (JMH) and EY02377 (LSU Eye Center Core Grant for Vision Research), an unrestricted research grant from LSU Health Sciences Center (J.M.H.), a Research to Prevent Blindness, Senior Scientific Investigator Award (J.M.H.), an unrestricted grant to the LSU Eye Center from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York, and by the Louisiana Vaccine Center and the South Louisiana Institute for Infectious Disease Research sponsored by the Louisiana Board of Regents, and by funds from the Louisiana Lions Eye Foundation, New Orleans. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCRR/NIH. We thank Dr. Keji Zhao from NHLBI/NIH for BRG1 expression vectors. We are grateful for the 17Syn+-EGFP virus from Dr. Timothy Foster of LSUHSC in New Orleans and Dr. Gus Kousoulas from Baton Rouge, LA. Our gratitude also goes to Dr. Robert Denver (Ann Arbor, MI) for the N2aTRβ cell line. We appreciate the suggestion and assistance of the editorial staff at LSUHSC in New Orleans, LA.

REFERENCES

- Amelio AL, McAnany PK, Bloom DC. A chromatin insulator-like element in the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript region binds CCCTC-binding factor and displays enhancer-blocking and silencing activities. J Virol. 2006;80:2358–2368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2358-2368.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat-Walter I, Riederer BM. Triiodothyronine and nerve growth factor are required to induce cytoplasmic dynein expression in rat dorsal root ganglion cultures. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;96(1–2):109–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedadala GR, Pinnoji RC, Hsia SCV. Early growth response gene 1 (Egr-1) regulates HSV-1 ICP4 and ICP22 gene expression. Cell Res. 2007;17:1–10. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendik I, Pfahl M. Similar ligand-induced conformational changes of thyroid hormone receptors regulate homo- and heterodimeric functions. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3107–3114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block T, Barney S, Masonis J, Maggioncalda J, Valyi-Nagy T, Fraser NW. Long term herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of nerve growth factor-treated PC12 cells. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(Pt 9):2481–2487. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DC. HSV LAT and neuronal survival. Int Rev Immunol. 2004;23(1–2):187–198. doi: 10.1080/08830180490265592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco FJ, Fraser NW. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript expression protects trigeminal ganglion neurons from apoptosis. J Virol. 2005;79:9019–9025. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9019-9025.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke LJ, Zhang R, Lu tz M, Renkowitz R. The thyroid hormone receptor and the insulator protein CTCF: two different factors with overlapping functions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83(1–5):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystricka M, Russ G. Immunity in latent Herpes simplex virus infection. Acta Virol. 2005;49:159–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter D, Hsiang C, Brown DJ, Jin L, Osorio N, Benmahamed L, Jones C, Wechsler SL. Stable cell lines expressing high levels of the herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT are refractory to caspase 3 activation and DNA laddering following cold shock induced apoptosis. Virology. 2007;369:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Lin L, Smith S, Huang J, Berger SL, Zhou J. CTCF-dependent chromatin boundary element exists between the latency-associated transcript and ICP0 promoters in the HSV-1 genome. J Virol. 2007;81:5192–5201. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02447-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone DE, Kim HS, Spindler SR. Alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptors bind immediately adjacent to the rat growth hormone gene TATA box in a negatively hormone-responsive promoter region. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10851–10856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C, Griffiths A, Li G, Silva LM, Kramer MF, Gaasterland T, Wang XJ, Coen DM. Prediction and identification of herpes simplex virus 1-encoded microRNAs. J Virol. 2006;80:5499–5508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00200-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deme D, Pommier J, Nunez J. Kinetics of thyroglobulin iodination and of hormone synthesis catalysed by thyroid peroxidase. Role of iodide in the coupling reaction. Eur J Biochem. 1976;70:435–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb11034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:737–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.027. quiz 764–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TP, Rybachuk GV, Kousoulas KG. Expression of the enhanced green fluorescent protein by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) as an in vitro or in vivo marker for virus entry and replication. J Virol Methods. 1998;75:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza HH, Jr, Hill JM. Effect of a beta-adrenergic antagonist, propranolol, on induced HSV-1 ocular recurrence in latently infected rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16:453–458. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.5.453.7051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser L, Barakat Walter I. Differential distribution of thyroid hormone receptor isoform in rat dorsal root ganglia and sciatic nerve in vivo and in vitro. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:217–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.d01-1088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwicke MA, Schaffer PA. Differential effects of nerve growth factor and dexamethasone on herpes simplex virus type 1 oriL- and oriS-dependent DNA replication in PC12 cells. J Virol. 1997;71:3580–3587. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3580-3587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier RT, Stevens JG, Dissette VB, Wagner EK. A herpes simplex virus transcript abundant in latently infected neurons is dispensable for establishment of the latent state. Virology. 1988;166:254–257. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and bovine herpesvirus 1 latency. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:79–95. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.79-95.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe DM, Cliffe A. Chromatin control of herpes simplex virus lytic and latent infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelle DM, Corey L. Herpes simplex: insights on pathogenesis and possible vaccines. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:381–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061606.095540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosz-Vnenchak M, Jacobson J, Coen DM, Knipe DM. Evidence for a novel regulatory pathway for herpes simplex virus gene expression in trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Virol. 1993;67:5383–5393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5383-5393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubat NJ, Amelio AL, Giordani NV, Bloom DC. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer/rcr is hyperacetylated during latency independently of LAT transcription. J Virol. 2004;78:12508–12518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12508-12518.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubat NJ, Tran RK, McAnany P, Bloom DC. Specific histone tail modification and not DNA methylation is a determinant of herpes simplex virus type 1 latent gene expression. J Virol. 2004;78:1139–1149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1139-1149.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel JM, Dussault JH, Puymirat J. Overexpression of the beta 1 thyroid receptor induces differentiation in neuro-2a cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2644–2648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquart M, Bhattacharjee P, Zheng X, Kaufman H, Thompson H, Varnell E, Hill J. Ocular reactivation phenotype of HSV-1 strain F(MP)E, a corticosteroid-sensitive strain. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26(3–4):205–209. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.3.205.14890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita A, Sasaki S, Kashiwabara Y, Nagayama K, Ohba K, Iwaki H, Misawa H, Ishizuka K, Nakamura H. Essential role of GATA2 in the negative regulation of th yrotropin beta gene by thyroid hormone and its receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:865–884. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Pertuz M, Sanchez-Pacheco A, Aranda A. The thyroid hormone receptor antagonizes CREB-mediated transcription. EMBO J. 2003;22:3102–3112. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxley MJ, Block TM, Liu HC, Fraser NW, Perng GC, Wechsler SL, Su YH. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection prevents detachment of nerve growth factor-differentiated PC12 cells in culture. J Gen Virol. 2002;83(Pt 7):1591–1600. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol PF, Chang JY, Johnson EM, Jr, Olivo PD. Herpes simplex virus gene expression in neurons: viral DNA synthesis is a critical regulatory event in the branch point between the lytic and latent pathways. J Virol. 1996;70:5476–5486. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5476-5486.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noisakran S, Halford WP, Veress L, Carr DJ. Role of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis and IL-6 in stress-induced reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus type 1. J Immunol. 1998;160:5441–5447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygard M, Wahlstrom GM, Gustafsson MV, Tokumoto YM, Bondesson M. Hormone-dependent repression of the E2F-1 gene by thyroid hormone receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:79–92. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HY, Davidson D, Raaka BM, Samuels HH. The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene promoter contains a novel thyroid hormone response element. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:319–330. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.3.8387156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Jin L, Henderson G, Perng GC, Brick DJ, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL, Jones C. Mapping herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript sequences that protect from apoptosis mediated by a plasmid expressing caspase-8. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:260–265. doi: 10.1080/13550280490468690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng GC, Jones C, Ciacci-Zanella J, Stone M, Henderson G, Yukht A, Slanina SM, Hofman FM, Ghiasi H, et al. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science. 2000;287:1500–1503. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesola JM, Zhu J, Knipe DM, Coen DM. Herpes simplex virus 1 immediate-early and early gene expression during reactivation from latency under conditions that prevent infectious virus production. J Virol. 2005;79:14516–14525. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14516-14525.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnoji RC, Bedadala GR, George B, Holland TC, Hill JM, Hsia SC. Repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor/neuronal restrictive silencer factor (REST/NRSF) can regulate HSV-1 immediate-early transcription via histone modification. Virol J. 2007;4:56. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Pacheco A, Aranda A. Binding of the thyroid hormone receptor to a negative element in the basal growth hormone promoter is associated with histone acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39383–39391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Lesoon-Wood LA, Dey A, Kuwata T, Weintraub BD, Humphrey G, Yang WM, Seto E, Yen PM, et al. Ligand-induced recruitment of a histone deacetylase in the negative-feedback regulation of the thyrotropin beta gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:5389–5398. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawtell NM, Thompson RL. Rapid in vivo reactivation of herpes simplex virus in latently infected murine ganglionic neurons after transient hyperthermia. J Virol. 1992;66:2150–2156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2150-2156.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer RB, Oken MM, Elson MK. Effects of fever and hyperthermia on thyroid function. J Nucl Med. 1980;21:1158–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YH, Moxley M, Kejariwal R, Mehta A, Fraser NW, Block TM. The HSV 1 genome in quiescently infected NGF differentiated PC12 cells can not be stimulated by HSV superinfection. J Neurovirol. 2000;6:341–349. doi: 10.3109/13550280009030760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YH, Moxley MJ, Ng AK, Lin J, Jordan R, Fraser NW, Block TM. Stability and circularization of herpes simplex virus type 1 genomes in quiescently infected PC12 cultures. J Gen Virol. 2002;83(Pt 12):2943–2950. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-12-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal-Singer R, Lasner TM, Podrzucki W, Skokotas A, Leary JJ, Berger SL, Fraser NW. Gene expression during reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 from latency in the peripheral nervous system is different from that during lytic infection of tissue cultures. J Virol. 1997;71:5268–5276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5268-5276.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal-Singer R, Peng C, Ponce de Leon M, Abrams WR, Banfield BW, Tufaro F, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Interaction of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein gC with mammalian cell surface molecules. J Virol. 1995;69:4471–4483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4471-4483.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakoc CR, Mandat SA, Olenchock BA, Blobel GA. Histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and HP1gamma are associated with transcription elongation through mammalian chromatin. Mol Cell. 2005;19:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa A, Santiago J, Belandia B, Pascual A. A response unit in the first exon of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene containing thyroid hormone receptor and Sp1 bindi ng sites mediates negative regulation by 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:863–873. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach JL, Kramer MF, et al. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454:780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter IB. Triiodothyronine exerts a trophic action on rat sensory neuron survival and neurite outgrowth through different pathways. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:455–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter IB, Droz B. Nuclear and cytoplasmic triiodothyronine-binding sites in primary sensory neurons and Schwann cells: radioautographic study during development. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;71:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Thompson KL, Shephard LB, Hudson LG, Gill GN. T3 receptor suppression of Sp1-dependent transcription from the epidermal growth factor receptor promoter via overlapping DNA-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16065–16073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]